Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

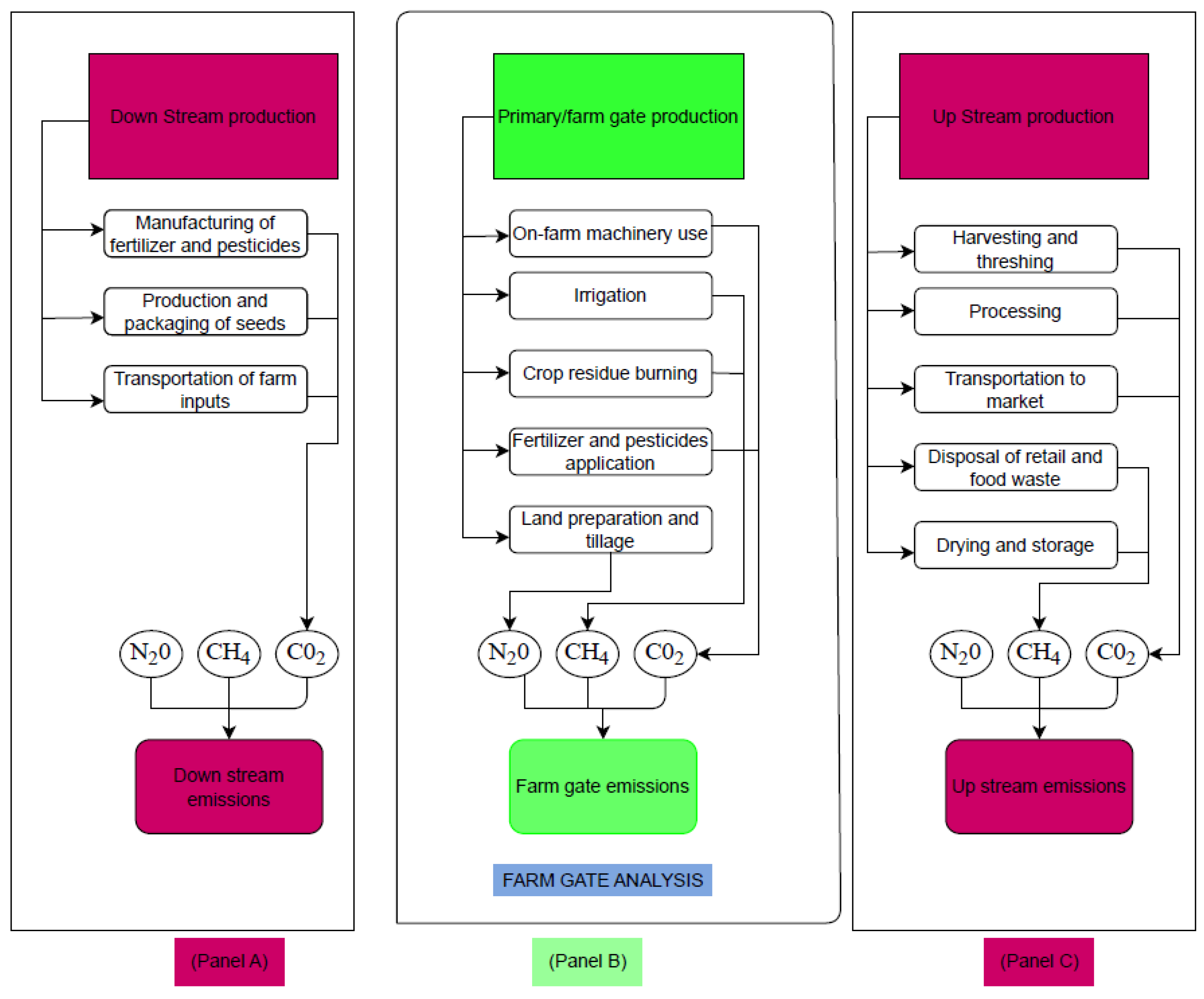

2.1. Crop Production and Farm-Gate Level Emissions Framework

2.2. Regression Strategy

2.3. Theoretical Specification of the Regression Model

2.4. Empirical Model Specification

2.5. Method of Estimation

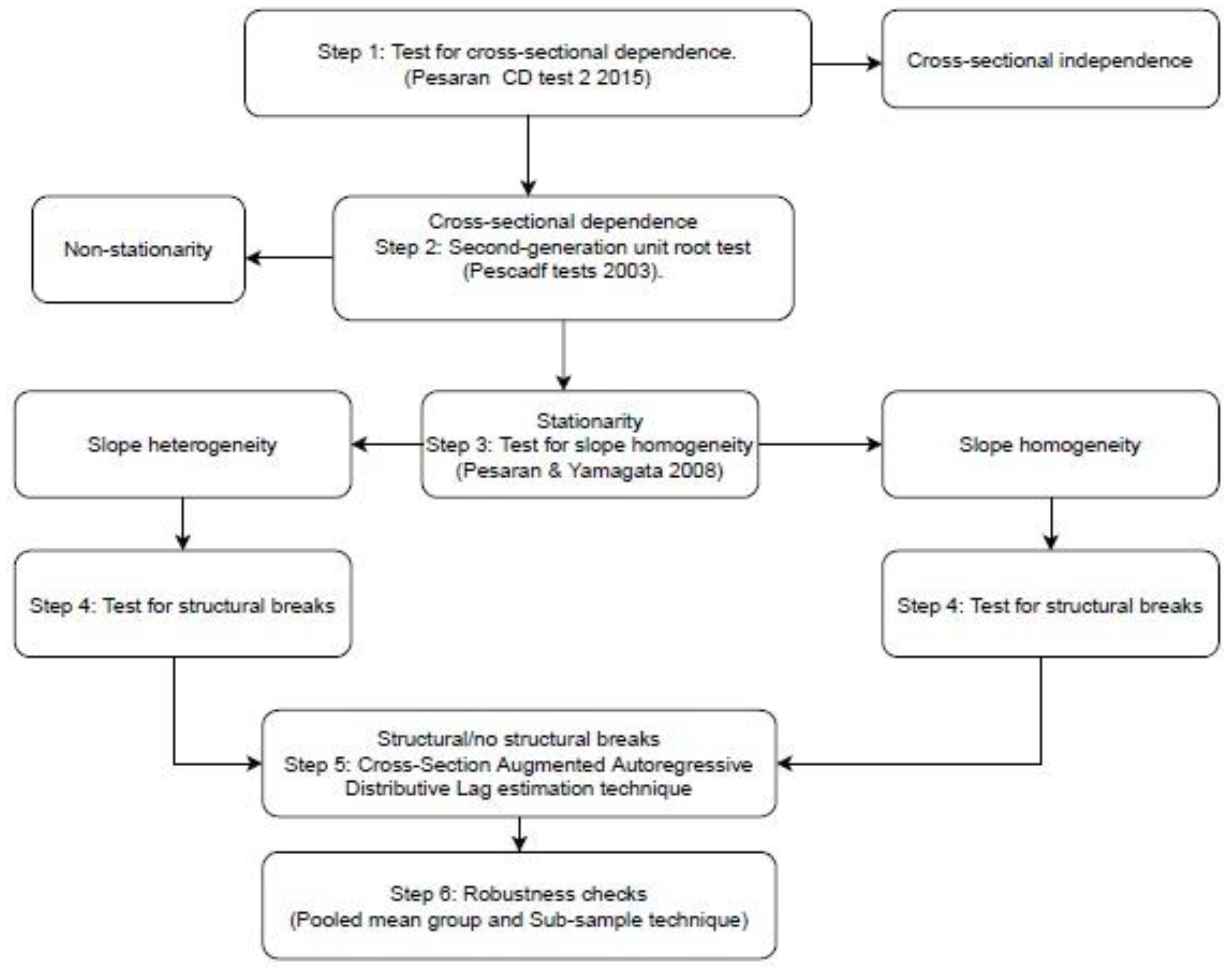

2.5.1. Diagnostic Tests

2.5.1.1. Cross-Sectional Dependence Test

2.5.1.2. Second-Generation Unit Root Test

2.5.1.3. Test for Slope Homogeneity

2.5.1.4. Test for Structural Breaks

2.6. Cross-Sectionally Augmented Autoregressive Distributed Lag

2.7. Proportional change coefficients

2.8. Data

2.9. Selection of key variables

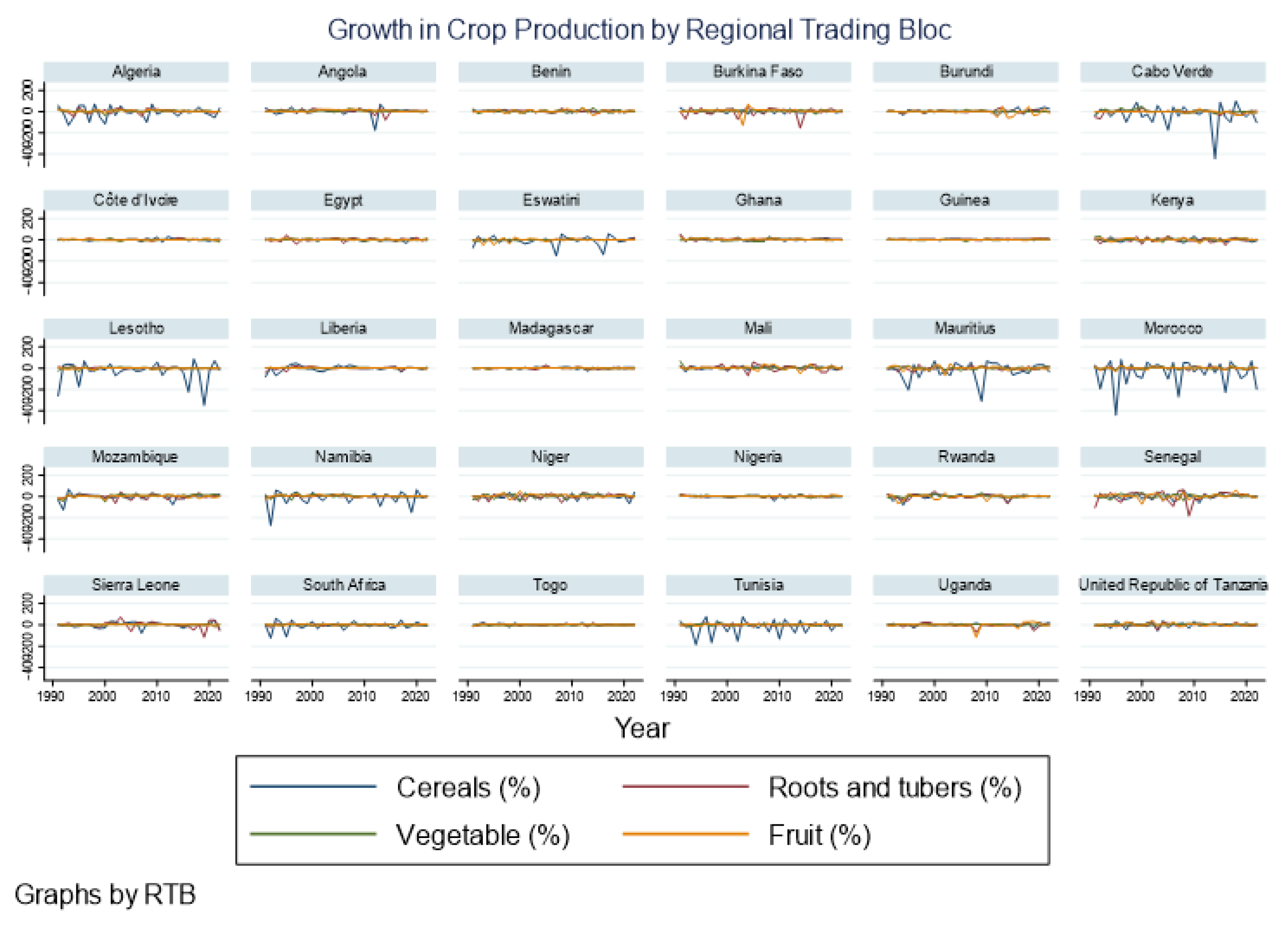

2.10. Trend Analyses

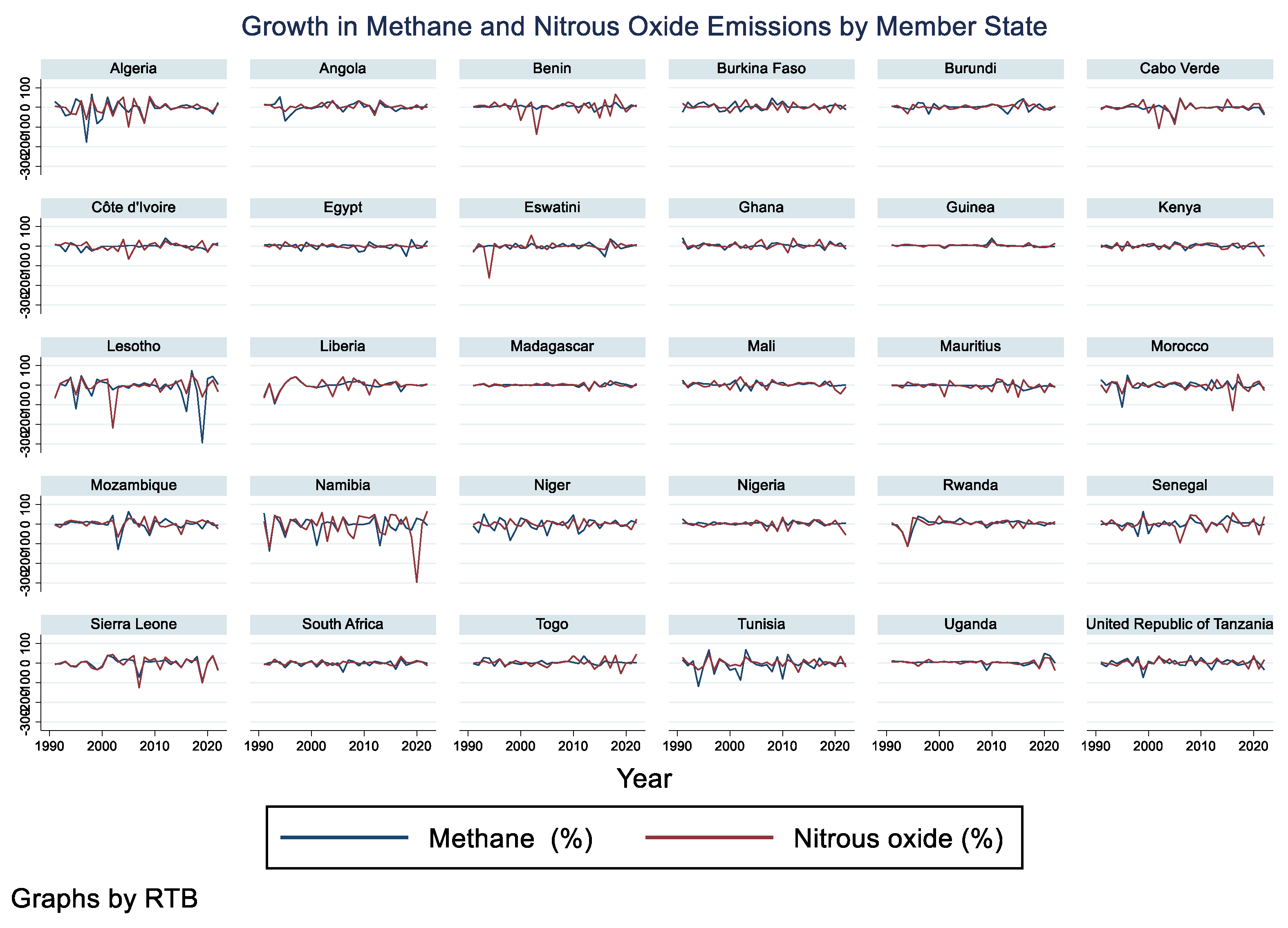

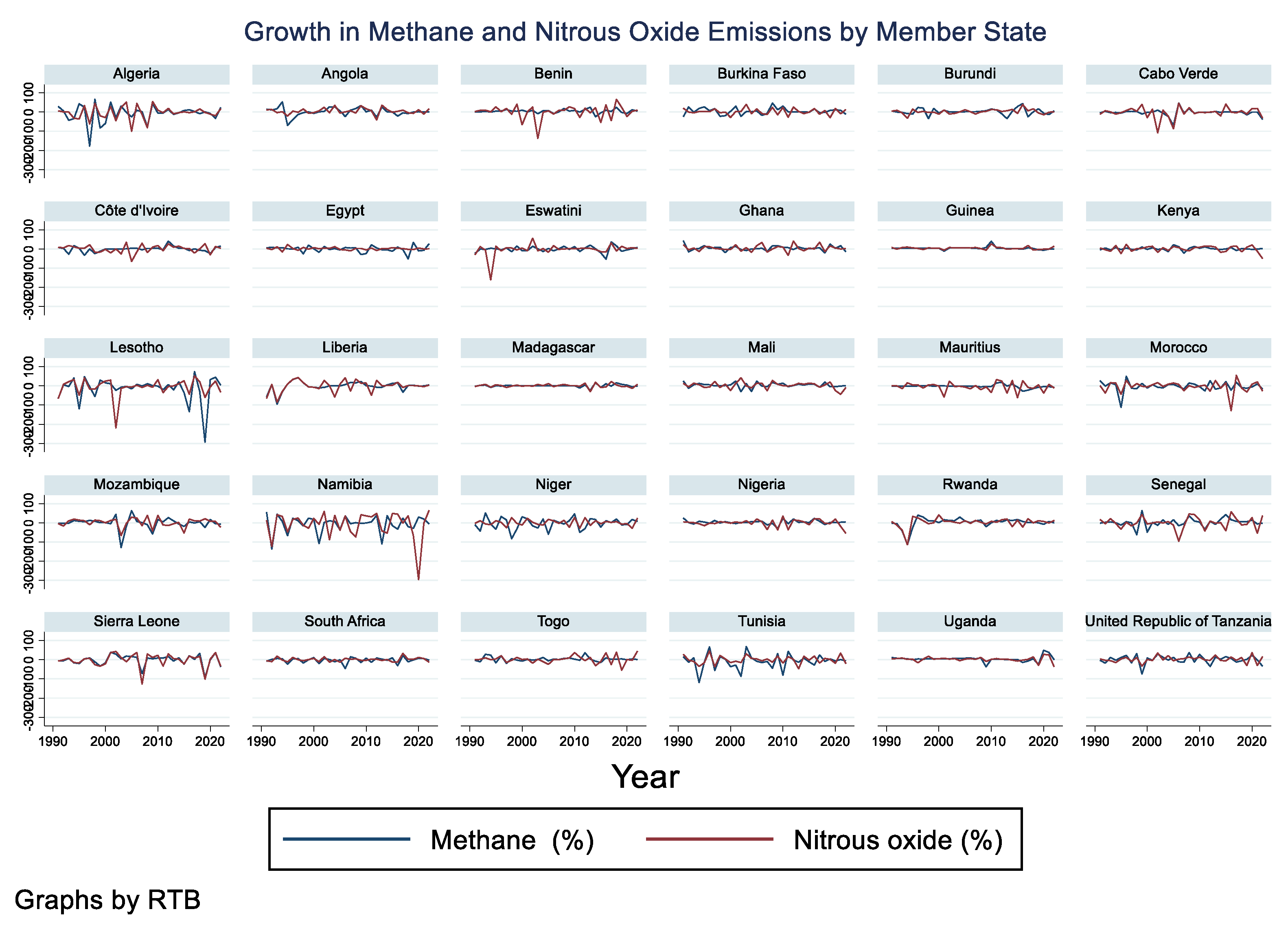

2.11. Growth in Methane and Nitrous Oxide Emissions

2.12. Crop Methane and Nitrous Oxide Intensity

3. Results

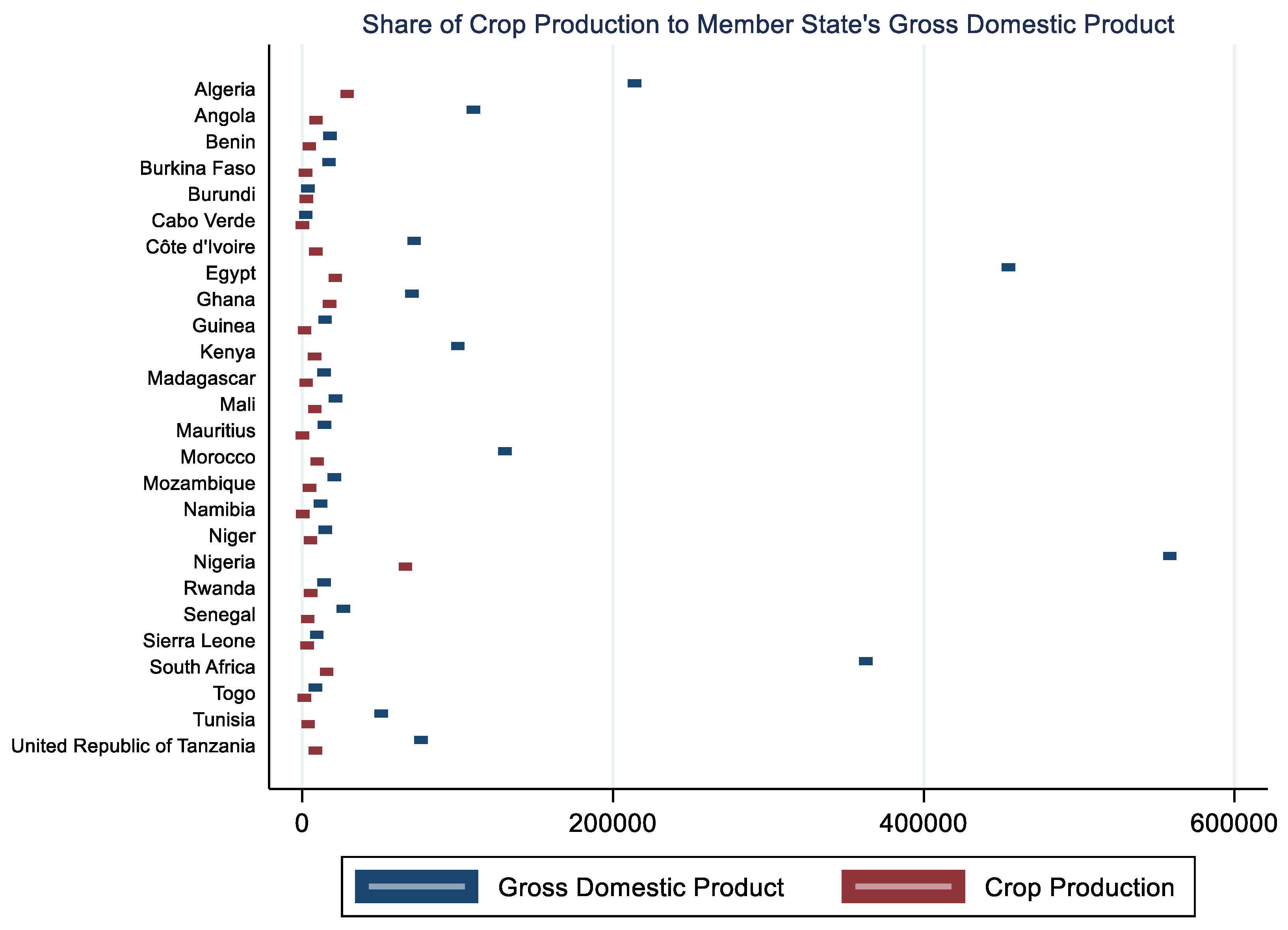

3.1. Descriptive Analyzes

3.2. Diagnostic Tests

3.3. Crop Production and Farm Gate Emissions: Short and Long-Run Relationships

3.3.1. Crop Production and Methane Emissions: Short and Long Run Relationships

3.3.2. Crop Production and Nitrous Oxide Emissions: Short and Long-Run Relationships

3.4. Robustness Checks: Pooled Mean Group and Sub-Sample Analysis

3.4.1. Pooled Mean Group Results

3.4.2. Sub-Sample Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| RTB | Methane | Nitrous Oxide |

Cereals | Roots & Tubers | Vegetables | Fruits | Population | Technology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | 1.905452 | 2.195615 | 3379664 | 2607641 | 3903938 | 3739872 | 12040.52 | 908.7052 |

| 0.438419 | 0.6875611 | 1406411 | 1593811 | 2139947 | 2097809 | 487.5547 | 785.5285 | |

| 0.9479 | 1.0524 | 870017 | 715936 | 1300588 | 1242788 | 11247.75 | -584.325 | |

| 2.876 | 3.4472 | 6066239 | 5020249 | 7986966 | 7071434 | 12718.63 | 2584.071 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Angola | 7.192694 | 0.7512727 | 1218094 | 8470025 | 1008288 | 2349265 | 9078.947 | 28557.11 |

| 3.490819 | 0.5161117 | 969838.1 | 4782581 | 638038.5 | 2089799 | 1123.496 | 29812.68 | |

| 2.6818 | 0.2208 | 248500 | 1798899 | 250000 | 405000 | 7650.444 | -334.5 | |

| 13.0039 | 1.739 | 3179113 | 1.83E+07 | 2016573 | 6120250 | 11168.04 | 106077 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Benin | 3.604391 | 0.7639091 | 1307770 | 5107649 | 398597.7 | 348965.8 | 4840.86 | 1254.186 |

| 1.950024 | 0.5667518 | 559093.4 | 1890488 | 181999.4 | 169602.2 | 971.806 | 1113.204 | |

| 1.4687 | 0.3029 | 545898 | 2019754 | 214645 | 173161.4 | 3261.667 | 40.58002 | |

| 7.7358 | 2.2982 | 2320756 | 7952286 | 744746.3 | 676228.8 | 6450.295 | 3840.753 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Burkina Faso | 24.57023 | 1.640588 | 3551293 | 130609.8 | 702582.7 | 537292.6 | 11015.93 | 1800.319 |

| 16.64094 | 0.6425372 | 1081092 | 72103.9 | 387412.5 | 467407.7 | 2256.687 | 1809.728 | |

| 5.0237 | 0.745 | 1517900 | 37400 | 229116 | 69831 | 7593.826 | 0.466252 | |

| 58.7137 | 2.6971 | 5180702 | 299127 | 1416382 | 1429305 | 15056.71 | 6551.879 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Burundi | 2.325809 | 0.2462879 | 384242.2 | 2198305 | 348509.8 | 1592571 | 7330.446 | 364.0649 |

| 1.223799 | 0.1261564 | 278550.4 | 1070159 | 115611.1 | 312135.2 | 1799.806 | 319.3043 | |

| 1.0551 | 0.148 | 224724 | 1262722 | 210000 | 957109.6 | 5075.806 | 1.25543 | |

| 5.0285 | 0.5487 | 1581835 | 4419890 | 498160.5 | 2355697 | 10848.08 | 1493.657 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Cabo Verde | 0.085012 | 0.0075242 | 7812.303 | 13383.7 | 29258.79 | 14251.07 | 195.4066 | 434.141 |

| 0.010498 | 0.0023795 | 7383.527 | 4118.413 | 14497.6 | 2805.704 | 5.275204 | 577.4965 | |

| 0.043 | 0.003 | 4 | 7665 | 4682 | 6998.93 | 188.641 | 0.2526 | |

| 0.0952 | 0.0139 | 36439 | 21263 | 49973.16 | 19007 | 202.818 | 1619.846 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 18.02668 | 1.277182 | 1898790 | 8439046 | 659303.4 | 2317163 | 10262.68 | 3502.637 |

| 5.700347 | 0.4033769 | 809132.4 | 3082855 | 60097.09 | 369014.7 | 1580.021 | 2029.808 | |

| 11.6375 | 0.6558 | 1221428 | 4685380 | 569753.7 | 1569720 | 7440.947 | 51.42595 | |

| 28.4025 | 2.1361 | 3308600 | 1.48E+07 | 774260.6 | 3155808 | 13017.21 | 8534.646 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Egypt | 165.8874 | 27.34557 | 2.01E+07 | 3760665 | 1.36E+07 | 1.11E+07 | 45550.75 | 111816 |

| 23.36905 | 4.536444 | 3288880 | 1745015 | 3373522 | 3181650 | 8533.03 | 71348.61 | |

| 105.1472 | 18.1261 | 1.30E+07 | 1600411 | 7459974 | 5977551 | 32450.63 | 735.7677 | |

| 213.8234 | 32.8514 | 2.41E+07 | 7712031 | 1.88E+07 | 1.60E+07 | 60691.93 | 237047.7 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Eswatini | 0.277246 | 0.1351758 | 92247.19 | 61337.73 | 11885.88 | 125597.1 | 891.9663 | 67.35088 |

| 0.040951 | 0.043385 | 28131.74 | 12613.61 | 941.323 | 24748.44 | 129.0743 | 54.09466 | |

| 0.1934 | 0.06 | 27540.66 | 43917 | 10500 | 73787.1 | 687.362 | -61.24678 | |

| 0.3672 | 0.2055 | 152068 | 94364.16 | 13345.9 | 162715.6 | 1121.095 | 154.906 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Ghana | 13.51608 | 1.243152 | 2440180 | 1.91E+07 | 628941.7 | 3804305 | 11441.48 | 5472.179 |

| 5.778714 | 0.7866342 | 1063430 | 8996124 | 141073.7 | 1767052 | 1242.964 | 5165.18 | |

| 4.6275 | 0.4273 | 843800 | 4409038 | 376972 | 923900 | 9297.561 | 17.8893 | |

| 27.9498 | 2.8538 | 5136565 | 3.82E+07 | 801831.5 | 6397830 | 13250.62 | 12706.64 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Guinea | 117.139 | 0.8987758 | 2525157 | 1644864 | 523224 | 1157566 | 6757.862 | 191.5825 |

| 60.07551 | 0.4303149 | 1084393 | 904542 | 35209.19 | 188701.8 | 1262.806 | 344.631 | |

| 48.791 | 0.3627 | 1061616 | 797775 | 440139 | 856803 | 4348.022 | -101.0378 | |

| 210.1131 | 1.699 | 4745053 | 4313086 | 566956.1 | 1614579 | 9022.706 | 1606.981 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Kenya | 6.481606 | 2.968221 | 3571863 | 2877909 | 1959503 | 2652795 | 29252.15 | 13663.48 |

| 1.450239 | 1.049515 | 725022.5 | 1035765 | 600950.9 | 863644.3 | 6204.769 | 13785.9 | |

| 4.6951 | 1.6589 | 2539301 | 1437978 | 743080 | 1400923 | 19483.07 | 72.99437 | |

| 8.7265 | 5.5514 | 4881251 | 4734181 | 3359488 | 4468921 | 39817.14 | 54593.73 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Lesotho | 0.338167 | 0.076803 | 127164 | 96997.26 | 27664.9 | 16010.38 | 1528.87 | 332.808 |

| 0.102067 | 0.0336183 | 64141.44 | 26693.76 | 5322.99 | 1412.726 | 73.75202 | 329.0402 | |

| 0.0889 | 0.0439 | 25678.06 | 45093 | 18000 | 13000 | 1379.922 | -0.808339 | |

| 0.5059 | 0.189 | 257418 | 134962.1 | 35000 | 19000 | 1667.714 | 1234.286 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Liberia | 2.361979 | 0.1458152 | 202201.8 | 524923.6 | 95278.76 | 173197.3 | 1786.776 | 19926.22 |

| 0.942721 | 0.0820897 | 85830.44 | 144054.1 | 19784.49 | 33465.9 | 515.1272 | 27234.66 | |

| 0.6364 | 0.0284 | 50000 | 232616.2 | 70996 | 106779 | 865.312 | 34.98093 | |

| 4.1834 | 0.2741 | 335180 | 769796.3 | 125356.5 | 217563 | 2517.04 | 83520.52 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Madagascar | 226.4066 | 1.324564 | 3647026 | 3899903 | 394242 | 1031850 | 13197.81 | 368.2073 |

| 27.27257 | 0.2881333 | 914651.2 | 630112.1 | 51151.28 | 188307.3 | 2698.242 | 365.3614 | |

| 181.7254 | 0.9841 | 2497184 | 2960139 | 330300 | 767800 | 8865.351 | 9.493062 | |

| 299.3309 | 1.8974 | 5159721 | 5183376 | 470948.3 | 1289990 | 17539.78 | 1349.597 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Mali | 38.44375 | 2.425688 | 5033452 | 453662.6 | 1234188 | 1116921 | 8967.909 | 1584.893 |

| 17.99707 | 1.435104 | 3010112 | 380888.9 | 555779 | 729994 | 1622.212 | 1750.402 | |

| 14.5249 | 0.7811 | 1771419 | 51296 | 296290 | 392951 | 6490.895 | 5.72972 | |

| 72.7271 | 5.8646 | 1.05E+07 | 1452527 | 2597052 | 2576204 | 11739.44 | 7679.898 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Mauritius | 0.119464 | 0.2005242 | 797.1212 | 17387.83 | 70759.96 | 18964.32 | 698.8862 | 1992.217 |

| 0.022647 | 0.050414 | 609.1133 | 3161.57 | 12109.77 | 6331.794 | 50.06979 | 1680.117 | |

| 0.069 | 0.1103 | 112 | 11654 | 44860.04 | 8370 | 592.342 | 14.77845 | |

| 0.1627 | 0.2829 | 2284 | 23317 | 93811.71 | 31958 | 756.756 | 4496.445 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Morocco | 5.501603 | 6.341245 | 6476768 | 1452429 | 3434894 | 4305758 | 13440.26 | 60297.24 |

| 0.767112 | 1.375903 | 2974395 | 353152.4 | 847129.7 | 1277107 | 264.3674 | 40605.3 | |

| 3.3945 | 3.6116 | 1783230 | 894210.1 | 1907077 | 2337928 | 12839.86 | 183.6424 | |

| 7.2056 | 9.3447 | 1.17E+07 | 1967534 | 4491362 | 6618471 | 13688.17 | 126623 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Mozambique | 21.15526 | 1.0946 | 1610493 | 5582967 | 529814.5 | 565793.1 | 15181.41 | 3954.453 |

| 7.960271 | 0.5334569 | 613783.8 | 1269572 | 553516.3 | 253428.9 | 3433.196 | 3487.002 | |

| 9.8411 | 0.357 | 244554.1 | 3365024 | 115282 | 280400 | 9935.737 | 23.39897 | |

| 33.6098 | 2.1766 | 2832309 | 7482694 | 2224968 | 1019695 | 21121.58 | 10952.81 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Namibia | 0.078303 | 0.1339364 | 114871.4 | 306863.5 | 39039.43 | 37611.89 | 1244.316 | 4406.658 |

| 0.019693 | 0.1550612 | 34827.81 | 66667.26 | 22936.58 | 20785.69 | 77.46508 | 3499.005 | |

| 0.0492 | 0.0161 | 31031 | 195000 | 8000 | 7998.06 | 1023.439 | 29.56727 | |

| 0.128 | 0.6772 | 186008.3 | 392075.9 | 67982.48 | 71123.62 | 1299.607 | 13785.07 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Niger | 2.366433 | 1.502612 | 3778998 | 331297.2 | 1250303 | 336543.6 | 12683.56 | 1130.317 |

| 0.592847 | 0.45282 | 1416583 | 278992.1 | 1050195 | 243196.4 | 4475.574 | 1183.053 | |

| 1.4677 | 0.8449 | 1850285 | 118320 | 249554.9 | 43800 | 6781.413 | 40.8132 | |

| 3.6941 | 2.2857 | 6100262 | 1103733 | 3605640 | 762360.2 | 21584 | 4599.48 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Nigeria | 306.2426 | 11.53765 | 2.40E+07 | 8.35E+07 | 1.07E+07 | 1.02E+07 | 85076.73 | 48374.03 |

| 108.4399 | 3.369717 | 3808570 | 2.88E+07 | 3836856 | 2359821 | 10149.39 | 47687.52 | |

| 147.9306 | 8.0291 | 1.77E+07 | 3.36E+07 | 4168000 | 6382000 | 66993.86 | 1002.5 | |

| 524.1397 | 21.0704 | 3.03E+07 | 1.36E+08 | 1.64E+07 | 1.69E+07 | 100786.3 | 150428.2 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Rwanda | 1.519518 | 0.3443 | 461602.6 | 2758519 | 412058.7 | 2672650 | 7985.937 | 1548.135 |

| 1.032416 | 0.1874906 | 244435.2 | 1037497 | 216855.7 | 438034 | 1786.131 | 2075.845 | |

| 0.1871 | 0.0635 | 130072.5 | 886071.8 | 121412.9 | 1549000 | 5344.914 | 7.66 | |

| 3.1715 | 0.7487 | 932107.3 | 4485985 | 688418.3 | 3611200 | 11247.44 | 7046.425 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Senegal | 11.22151 | 0.7853939 | 1593330 | 441460.1 | 436945 | 586966.3 | 6801.549 | 3171.29 |

| 7.981554 | 0.4486956 | 861180 | 506957.2 | 323109.5 | 516698.2 | 1390.933 | 2647.756 | |

| 3.405 | 0.2624 | 730335 | 41762.52 | 69661 | 167637 | 4616.787 | 57.85107 | |

| 29.6551 | 1.9716 | 3663690 | 1688559 | 1048198 | 1997619 | 9231.74 | 10463.86 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Sierra Leone | 35.25101 | 0.4251121 | 831425.9 | 1703635 | 279722.5 | 214152.9 | 3617.961 | 170.6266 |

| 14.89276 | 0.2197511 | 431829.1 | 1342271 | 87725.94 | 48840.27 | 680.6779 | 228.7765 | |

| 12.3042 | 0.1111 | 222472 | 224400 | 180000 | 152985 | 2797.796 | -7.46292 | |

| 78.3878 | 0.9433 | 2131723 | 4038764 | 479186 | 282814.1 | 4704.509 | 968.7065 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| South Africa | 10.38005 | 11.81278 | 1.33E+07 | 1974537 | 2303409 | 5821977 | 19334.56 | 73580.81 |

| 2.08042 | 1.795304 | 3257667 | 459713.8 | 294933.3 | 1346182 | 439.1242 | 59399.63 | |

| 7.2043 | 9.2471 | 5056342 | 1125028 | 1892468 | 3815637 | 18015.16 | -78.45956 | |

| 14.6091 | 17.0976 | 1.96E+07 | 2763924 | 2724794 | 8772836 | 19800.02 | 182594.3 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Togo | 2.061203 | 0.4702273 | 946571.4 | 1514481 | 144587.5 | 55243.69 | 3778.373 | 919.5698 |

| 0.761084 | 0.1918064 | 307205 | 390027.1 | 5667.2 | 9354.613 | 696.5604 | 948.4203 | |

| 0.9135 | 0.2865 | 464877 | 840495.5 | 130698.4 | 41660.19 | 2704.301 | 22.72051 | |

| 3.329 | 1.0891 | 1439850 | 2244231 | 158700 | 68459.46 | 4927.839 | 3053.119 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Tunisia | 0.799524 | 1.928185 | 1725829 | 337181.8 | 2092994 | 1679399 | 3548.361 | 20842.69 |

| 0.232564 | 0.4039127 | 592995.9 | 76908.41 | 729207.2 | 442289.3 | 48.18436 | 10423.03 | |

| 0.3224 | 1.0384 | 550525.5 | 199000 | 1096862 | 1049565 | 3462.236 | 101.8172 | |

| 1.3492 | 2.9206 | 2896345 | 465000 | 3219344 | 2530206 | 3622.883 | 43107.63 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Uganda | 8.826661 | 0.9874939 | 2809803 | 5777216 | 884843.6 | 7835354 | 25121.42 | 2800.509 |

| 4.010887 | 0.2932797 | 942322.6 | 1671836 | 382722.5 | 2448102 | 6620.009 | 2786.402 | |

| 3.9167 | 0.5389 | 1576000 | 3501000 | 415500 | 3451798 | 15507.4 | -5.624783 | |

| 21.7561 | 1.8818 | 5525000 | 8765000 | 1412799 | 1.18E+07 | 37099.64 | 8707.827 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| United Republic | 124.485 | 3.347121 | 6959240 | 8634589 | 1806026 | 3652592 | 30820.69 | 4679.756 |

| 54.25941 | 1.67222 | 3043055 | 2112238 | 736986.4 | 1737320 | 6471.257 | 4708.991 | |

| 53.3253 | 1.4451 | 2952900 | 4862263 | 1013675 | 1213738 | 20651.76 | 5.606912 | |

| 226.4278 | 7.1964 | 1.25E+07 | 1.32E+07 | 3182946 | 5884175 | 42177.77 | 19276.83 | |

| 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | |

| Total | 38.61901 | 2.811911 | 3801119 | 5788327 | 1663200 | 2338144 | 13449.15 | 13937.07 |

| 77.89167 | 5.535796 | 5813586 | 1.60E+07 | 3175679 | 3150028 | 17080.64 | 33767.77 | |

| 0.043 | 0.003 | 4 | 7665 | 4682 | 6998.93 | 188.641 | -584.325 | |

| 524.1397 | 32.8514 | 3.03E+07 | 1.36E+08 | 1.88E+07 | 1.69E+07 | 100786.3 | 237047.7 | |

| 990 | 990 | 990 | 990 | 990 | 990 | 990 | 990 |

References

- IPCC. [1] IPCC. 2023. Summary for Policymakers: Synthesis Report. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, studies, Pp: 1–34.

- Rafiq, S.; Salim, R.; Apergis, N. Agriculture, trade openness and emissions: an empirical analysis and policy options. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2016, 60, 348–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, A.A.A.; Ni, L.; Shaghaleh, H.; Elsadek, E.; Hamoud, Y.A. Effect of Carbon Content in Wheat Straw Biochar on N2O and CO2 Emissions and Pakchoi Productivity Under Different Soil Moisture Conditions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotz, M.; Levermann, A.; Wenz, L. The effect of rainfall changes on economic production. Nature 2022, 601, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, S.; Sidhu, G.P.S. Climate change regulated abiotic stress mechanisms in plants: a comprehensive review. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varma, V.; Mosedale, J.R.; Alvarez, J.A.G.; Bebber, D.P. Socio-economic factors constrain climate change adaptation in a tropical export crop. Nat. Food 2025, 6, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Kaur, S.; Agarwal, A.; Sabharwal, M.; Tripathi, A.D. Amaranthus crop for food security and sustainable food systems. Planta 2024, 260, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division 2022. World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results. UN DESA/POP/2022/TR/NO. 3.

- Eise, J.; Foster, K.A. (Eds.) How to Feed the World; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- African Union, 2014. Available online: https://www.resakss.org/node/ 6454?region=aw/retrieve (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Statista 2025. Agriculture in Africa - statistics and facts. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/12901/agriculture-in-africa/#topicOverview (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Tadesse, B.; Ahmed, M. Impact of adoption of climate smart agricultural practices to minimize production risk in Ethiopia: A systematic review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howden, S.M.; Soussana, J.-F.; Tubiello, F.N.; Chhetri, N.; Dunlop, M.; Meinke, H. Adapting agriculture to climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19691–19696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochman, Z.; Gobbett, D.L.; Horan, H. Climate trends account for stalled wheat yields in Australia since 1990. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2017, 23, 2071–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, E.E.; Webber, H.; Asseng, S.; Boote, K.; Durand, J.L.; Ewert, F.; Martre, P.; MacCarthy, D.S. Climate change impacts on crop yields. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Ma, H.; Irfan, M.; Ahmad, M. Does carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and GHG emissions influence the agriculture? Evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 28768–28779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization. 2023. Available online: https://wmo.int/files/early-warnings-all-focushazard-monitoring-and-forecasting (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Kabange, N.R.; Kwon, Y.; Lee, S.-M.; Kang, J.-W.; Cha, J.-K.; Park, H.; Dzorkpe, G.D.; Shin, D.; Oh, K.-W.; Lee, J.-H. Mitigating Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Crop Production and Management Practices, and Livestock: A Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2022. IPCC Sixth Assessment Report: Working Group III: Mitigation of Climate Change. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/chapter/chapter-7/ (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Cao, L.M.; Li, M.B.; Wang, X.Q.; et al. Life cycle assessment of carbon footprint for rice production in Shanghai. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2014, 34, 491–499, (Chinese with abstract in English). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Shen, L.; Li, C. Can crop production agglomeration reduce carbon emissions?—empirical evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1516238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, H.; Jain, N.; Bhatia, A.; Patel, J.; Aggarwal, P. Carbon footprints of Indian food items. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2010, 139, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvan, L.P.C.; Bhatti, U.A.; Campo, C.C.; Trujillo, R.A.S. The Nexus Between CO2 Emission, Economic Growth, Trade Openness: Evidences From Middle-Income Trap Countries. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabuya, D.O.; Sule, F.O.; Ndwiga, M.J. The effect of agricultural trade openness on economic growth in the East African Community. Cogent Econ. Finance 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluwani, T. Agricultural Economic Growth, Renewable Energy Supply and CO2 Emissions Nexus. Economies 2023, 11, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, A. Does economic integration damage or benefit the environment? Africa's experience. Energy Policy 2019, 132, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendrill, F.; Persson, U.M.; Godar, J.; Kastner, T.; Moran, D.; Schmidt, S.; Wood, R. Agricultural and forestry trade drives large share of tropical deforestation emissions. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 56, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Enna, L.; Monney, A.; Tran, D.K.; Rasoulinezhad, E.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F. The Long-Run Effects of Trade Openness on Carbon Emissions in Sub-Saharan African Countries. Energies 2020, 13, 5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Nielsen, C.P.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; Bi, J.; et al. Trade-driven relocation of air pollution and health impacts in China. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossman, G.; Krueger, A. Environmental Impacts of a North American Free Trade Agreement. NBER Working Paper No. 3914; National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fader, M.; Gerten, D.; Krause, M.; Lucht, W.; Cramer, W. Spatial decoupling of agricultural production and consumption: quantifying dependences of countries on food imports due to domestic land and water constraints. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 014046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’aMour, C.B.; Anderson, W. International trade and the stability of food supplies in the Global South. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 074005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, S.; Modeling Energy Consumption, CO2 Emissions and economic growth nexus in Ethiopia: evidence from ARDL approach to cointegration and causality analysis. Munich Personal RePEc Archive (MPRA) Jigjiga University, paper No. 83000. 2017. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/83000/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Jiang, Y.; Cai, W.; Wan, L.; Wang, C. An index decomposition analysis of China's interregional embodied carbon flows. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 88, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, A. Why are there large differences in performances when the same carbon emission reductions are achieved in different countries? J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 103, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; He, Q.; Qi, Y. Digital Economy, Agricultural Technological Progress, and Agricultural Carbon Intensity: Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 6488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Agriculture Organization, 2020. The share of agri-food systems in total greenhouse gas emissions Global, regional and country trends. FAOSTAT Analtytical Brief Series No 1., 6.

- Cheng, K.; Pan, G.; Smith, P.; Luo, T.; Li, L.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, X.; Han, X.; Yan, M. Carbon footprint of China's crop production—An estimation using agro-statistics data over 1993–2007. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2011, 142, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Yan, M.; Nayak, D.; Pan, G.X.; Smith, P.; Zheng, J.F.; Zheng, J.W. Carbon footprint of crop production in China: an analysis of National Statistics data. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 153, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Lin, H.; Balasus, N.; Hardy, A.; East, J.D.; Zhang, Y.; Runkle, B.R.K.; Hancock, S.E.; Taylor, C.A.; Du, X.; et al. Global Rice Paddy Inventory (GRPI): A High-Resolution Inventory of Methane Emissions From Rice Agriculture Based on Landsat Satellite Inundation Data. Earth's Futur. 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Shen, L.; Li, C. Can crop production agglomeration reduce carbon emissions?—empirical evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1516238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, H. Methane and nitrous oxide emissions from agricultural fields in Japan and mitigation options: a review. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 70, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.-F.; Pu, C.; Liu, S.-L.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, R.; Chen, F.; Xiao, X.-P.; Zhang, H.-L. Carbon and nitrogen footprint of double rice production in Southern China. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 64, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Liu, B.; Wang, J.; Jin, D.; Zhang, H. Assessing Global Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Key Drivers and Mitigation Strategies. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Zhao, P.; Li, C.; Wang, D.; Ming, C.; Chen, L.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, Q.; Tang, L.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Intercropping achieves long-term dual goals of yield gains and soil N2O emission mitigation. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2025, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlowsky, S.; Gläser, M.; Henschel, K.; Schwarz, D. Seasonal Nitrous Oxide Emissions From Hydroponic Tomato and Cucumber Cultivation in a Commercial Greenhouse Company. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemarpe, S.E.; Musafiri, C.M.; Macharia, J.M.; Kiboi, M.N.; Ng’Etich, O.K.; Shisanya, C.A.; Okeyo, J.; Okwuosa, E.A.; Ngetich, F.K. Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Smallholders’ Cropping Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa. Adv. Agric. 2021, 2021, 4800527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, L.-A.; Tobarra, M.-A.; Cadarso, M.; Gómez, N.; Cazcarro, I. Eating local and in-season fruits and vegetables: Carbon-water-employment trade-offs and synergies. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 192, 107270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Bo, Y.; Adalibieke, W.; Winiwarter, W.; Zhang, X.; Davidson, E.A.; Sun, Z.; Tian, H.; Smith, P.; Zhou, F. The global potential for mitigating nitrous oxide emissions from croplands. One Earth 2024, 7, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, A.; Raza, T.; Bhatti, T.T.; Eash, N.S. Climate Impacts on the agricultural sector of Pakistan: Risks and solutions. Environ. Challenges 2022, 6, 100433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ma, L.; Qi, Z.; Fang, Q.; Harmel, R.D.; Schmer, M.R.; Jin, V.L. Measured and simulated effects of residue removal and amelioration practices in no-till irrigated corn (Zea mays L.). Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 146, 126807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillette, K.; Ma, L.; Malone, R.W.; Fang, Q.; Halvorson, A.D.; Hatfield, J.L.; Ahuja, L. Simulating N 2 O emissions under different tillage systems of irrigated corn using RZ-SHAW model. Soil Tillage Res. 2017, 165, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, L.; Rulli, M.C.; Ali, S.; Chiarelli, D.D.; Dell’angelo, J.; Mueller, N.D.; Scheidel, A.; Siciliano, G.; D’odorico, P. Energy implications of the 21st century agrarian transition. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel D and Pimentel MH (eds) 2007 Food, Energy, and Society (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press).

- Balestra, P. 1982. Dynamic Misspecification and Serial Correlation. In: Paelinck, J.H.P. (eds) Qualitative and Quantitative Mathematical Economics. Advanced Studies in Theoretical and Applied Econometrics, vol 1. Springer, Dordrecht. [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. Testing Weak Cross-Sectional Dependence in Large Panels. Econ. Rev. 2015, 34, 1089–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htike, M.M.; Shrestha, A.; Kakinaka, M. Investigating whether the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis holds for sectoral CO2 emissions: evidence from developed and developing countries. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 12712–12739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, H. 2003. A Simple Panel Unit Root Test in the Presence of Cross Section Dependence, Cambridge Working Papers in Economics 0346, Faculty of Economics (DAE), University of Cambridge.

- Pesaran, M.H.; Yamagata, T. Testing slope homogeneity in large panels. J. Econ. 2008, 142, 50–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. 2017. Available online: https://www.stata.com/support/faqs/resources/citing-software-documentation-faqs/ (accessed on day month year).

- Ehrlich, P.R.; Holdren, J.P. Impact of Population Growth. Science 1971, 171, 1212–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Rosa, E.A. 1994. Rethinking the environmental impacts of population, affluence and technology. Human Ecology Review: Vol. 1, No. 2 (SUMMER/AUTUMN 1994)1, 277-300.

- Mignamissi, D.; Tebeng, E.X.P.; Tchinda, A.D.M. Does trade openness increase CO2 emissions in Africa? A revaluation using the composite index of Squalli and Wilson. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2024, 44, 645–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.; Chowdhury, S.A. Analysis of agricultural greenhouse gas emissions using the STIRPAT model: a case study of Bangladesh. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 3945–3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiba, S.; Belaid, F. The pollution concern in the era of globalization: Do the contribution of foreign direct investment and trade openness matter? Energy Econ. 2020, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah, K.; Du, J.; Poku, J. Causal relationship between agricultural production and carbon dioxide emissions in selected emerging economies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 24764–24777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudik, A.; Pesaran, H. 2015. Large panel data models with cross-sectional dependence: A survey. In The Oxford Handbook of Panel Data, ed. B. H. Baltagi, 3-45. Oxford: Oxford University Press https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199940042.013.0001. [CrossRef]

- Ditzen, J.; Karavias, Y.; Westerlund, J. Multiple Structural Breaks in Interactive Effects Panel Data Models. J. Appl. Econ. 2025, 40, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, M. Jeffrey 2012. Introductory Econometrics A Modern Approach F i f t h E d i t i o n: Michigan State University United States of America: Page 193.

- Benoit K 2011. Linear Regression Models with Logarithmic Transformations: Lecture note. Available online: https://kenbenoit.net/assets/courses/me104/logmodels2.pdf?utm_source (accessed on August 2025).

- Shaari, M.S.; Abidin, N.Z.; Ridzuan, A.R.; Meo, M.S. THE IMPACTS OF RURAL POPULATION GROWTH, ENERGY USE AND ECONOMIC GROWTH ON CO2 EMISSIONS. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2021, 11, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makutėnienė, D.; Staugaitis, A.J.; Makutėnas, V.; Grīnberga-Zālīte, G. The Impact of Economic Growth and Urbanisation on Environmental Degradation in the Baltic States: An Extended Kaya Identity. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT Food Balance Sheets. 2020. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FBS (accessed on 24 April 2020).

- Waha, K.; van Wijk, M.T.; Fritz, S.; See, L.; Thornton, P.K.; Wichern, J.; Herrero, M. Agricultural diversification as an important strategy for achieving food security in Africa. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2018, 24, 3390–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, B.; Defrance, D.; Iizumi, T. Evidence of crop production losses in West Africa due to historical global warming in two crop models. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariom, T.O.; Dimon, E.; Nambeye, E.; Diouf, N.S.; Adelusi, O.O.; Boudalia, S. Climate-Smart Agriculture in African Countries: A Review of Strategies and Impacts on Smallholder Farmers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkonya, E.; Kato, E.; Msimanga, M.; Nyathi, N. Climate shock response and resilience of smallholder farmers in the drylands of south-eastern Zimbabwe. Front. Clim. 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, R.; Gutam, S. Climate change impacts on tuber crops: vulnerabilities and adaptation strategies. J. Hortic. Sci. 2023, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ma, L.; Qi, Z.; Fang, Q.; Harmel, R.D.; Schmer, M.R.; Jin, V.L. Measured and simulated effects of residue removal and amelioration practices in no-till irrigated corn (Zea mays L.). Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 146, 126807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, T.S.; Mpanda, M.; Pelster, D.E.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Rufino, M.C.; Thiong'O, M.; Mutuo, P.; Abwanda, S.; Rioux, J.; Kimaro, A.A.; et al. Greenhouse gas fluxes from agricultural soils of Kenya and Tanzania. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 2016, 121, 1568–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osabohien, R. , Matthew, O., Aderounmu, B., et al., 2019. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Crop Production in West Africa : Examining the Mitigating Potential of Social Protection. 9(1), 57–66. [CrossRef]

- Pryor, S.W.; Smithers, J.; Lyne, P.; van Antwerpen, R. Impact of agricultural practices on energy use and greenhouse gas emissions for South African sugarcane production. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayo, L.; Hasegawa, H. Enhancing emission reductions in South African agriculture: The crucial role of carbon credits in incentivizing climate-smart farming practices. Sustain. Futur. 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Akiyama, H.; Yagi, K.; Yan, X. Controlling variables and emission factors of methane from global rice fields. Atmospheric Meas. Tech. 2018, 18, 10419–10431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, S.; Park, H.; Kim, J.; Park, S.J.; Shin, D.; Lee, J.-H.; Song, Y.H.; Paek, N.-C.; Kim, C.M. Methane Emission from Rice Fields: Necessity for Molecular Approach for Mitigation. Rice Sci. 2023, 31, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, S.T. Fertilizer and sustainable intensification in Sub-Saharan Africa. Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 18, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrullah, M.; Liang, L.; Rizwanullah, M.; Yu, X.; Majrashi, A.; Alharby, H.F.; Alharbi, B.M.; Fahad, S. Estimating Nitrogen Use Efficiency, Profitability, and Greenhouse Gas Emission Using Different Methods of Fertilization. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 869873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obossou, E.; Totin, E.; Singh, C.; Segnon, A.C. A systematic review of climate change adaptation in vegetable farming systems in Africa. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobarteh, M.; AFRICAN FUTURES; INNOVATION PROGRAMME Geographic Futures. June. Available online: https://futures.issafrica.org/geographic/recs/amu/#impact-on-carbon-emissions (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Pesaran, M.H. General Diagnostic Tests for Cross Section Dependence in Panels; Faculty of Economics, University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, J.; Petrova, Y.; Norkute, M. CCE in fixed-T panels. J. Appl. Econ. 2019, 34, 746–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran MH, Shin Y, Smith RP 1999. Pooled mean group estimation of dynamic heterogeneous panels. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):621–34. 6: 1999;94(446).

- Zhao, G.; Werku, B.C.; Bulto, T.W. Impact of agricultural emissions on goal 13 of the sustainable development agenda: in East African strategy for climate action. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2025, 37, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, M.V.; Da Cunha, D.A.; Carlos, S.D.M.; Costa, M.H. Nitrogen-Use Efficiency, Nitrous Oxide Emissions, and Cereal Production in Brazil: Current Trends and Forecasts. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0135234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushanskaya, M.; Blumenfeld, H. K.; Marian, V. The Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (LEAP-Q): Ten years later. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 2020, 23, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabato, W.; Getnet, G.T.; Sinore, T.; Nemeth, A.; Molnár, Z. Towards Climate-Smart Agriculture: Strategies for Sustainable Agricultural Production, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Reduction. Agronomy 2025, 15, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lv, D. Analysis of Agricultural CO2 Emissions in Henan Province, China, Based on EKC and Decoupling. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Werku, B.C.; Bulto, T.W. Impact of agricultural emissions on goal 13 of the sustainable development agenda: in East African strategy for climate action. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2025, 37, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Zhu, B.; Bah, H.; Raza, S.T. How Tillage and Fertilization Influence Soil N2O Emissions after Forestland Conversion to Cropland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lognoul, M.; Theodorakopoulos, N.; Hiel, M.-P.; Regaert, D.; Broux, F.; Heinesch, B.; Bodson, B.; Vandenbol, M.; Aubinet, M. Impact of tillage on greenhouse gas emissions by an agricultural crop and dynamics of N2O fluxes: Insights from automated closed chamber measurements. Soil Tillage Res. 2017, 167, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnier, J.; Casquin, A.; Mercier, B.; Martinez, A.; Gréhan, E.; Azougui, A.; Bosc, S.; Pomet, A.; Billen, G.; Mary, B. Six years of nitrous oxide emissions from temperate cropping systems under real-farm rotational management. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 354, 110085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loaiza, S.; Verchot, L.; Valencia, D.; Costa, C.; Trujillo, C.; Garcés, G.; Puentes, O.; Ardila, J.; Chirinda, N.; Pittelkow, C. Identifying rice varieties for mitigating methane and nitrous oxide emissions under intermittent irrigation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 372, 123376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mzezewa, J. Impacts of Converting Native Grassland into Arable Land and an Avocado Orchard on Soil Hydraulic Properties at an Experimental Farm in South Africa. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.; Yilmaz, T.; Kumar, S.; Fennell, A.; Hernandez, J.L.G. Influences of grassland to cropland conversion on select soil properties, microbiome and agricultural emissions. Soil Res. 2022, 60, 561–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliciano, D.; Smith, P.; Mabhaudhi, T. Climate change exacerbates inequalities between small-scale and large-scale farmers in South Africa’s fruit export market. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2025, 25, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S/n | Economic Community of West African States | South African Development Community | East African Community | The Maghreb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Benin | Angola | Burundi | Algeria |

| 2 | Burkina Faso | Eswatini | Kenya | Egypt |

| 3 | Cabo Verde | Lesotho | Rwanda | Morocco |

| 4 | Côte d'Ivoire | Madagascar | Tanzania | Tunisia |

| 5 | Ghana | Mauritius | Uganda | |

| 6 | Guinea | Mozambique | ||

| 7 | Liberia | Namibia | ||

| 8 | Mali | South Africa | ||

| 9 | Niger | |||

| 10 | Nigeria | |||

| 11 | Senegal | |||

| 12 | Sierra Leone | |||

| 13 | Togo |

| Variable | Description | Data source | Measurement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methane | Emissions from agricultural activities such as burning residues and the cultivation of rice and other crops. | FAOSTAT | Kilotons |

[39,40] |

| Nitrous oxide | Emissions from agricultural activities, like irrigation and land use change. | [45,49] | ||

| Cereal | The primary output of all cereals at the farm-gate. | Metric tons | [39,42] | |

| Root and tuber | The total output of roots and tubers at the farm-gate. |

[43,45] | ||

| Vegetable | The primary output of vegetables at the farm-gate. | [46,47] | ||

| Fruit | The primary output of all fruits at the farm-gate. | [48,49] | ||

| Rural population | The total number of people that reside in the rural area per year |

Per thousand people. | [71] | |

| Technology | It encompasses the government expenditure, credit, development flows, and foreign direct investment in the agricultural sector. |

US$ million |

[72] |

| Variable | AMU | EAC | ECOWAS | SADC | Full sample | Means |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (Standard deviation) |

Mean (Standard deviation) |

Mean (Standard deviation) |

Mean (Standard deviation) |

Mean (Standard deviation) |

Highest Mean Difference (RTB) |

|

| Methane (In kilotons) | 307.29 (56.90) |

10.45 (3.50) |

574.89 (228.59) |

265.95 (31.36) |

38.62 (77.89) |

564.44 +, * (ECOWAS) |

| Nitrous oxide (In kilotons) | 42.13 (7.66) |

3.58 (1.31) |

23.12 (8.08) |

15.53 (29.00) |

2.81 (5.54) |

38.55 -, * (AMU) |

| Cereals (In million metric tons) | 41.4 (8.88) |

4.47 (1.05) |

48.1 (13.2) |

20.1 (4.95) |

3.80 (5 .81) |

43.7 +, * (ECOWAS) |

| Roots and tubers (In million metric tons) | 22.4 (5.16) |

7.80 (2.64) |

123.0 (45.6) |

20.4 (6.58) |

5.79 (16.0) |

115 +, * (ECOWAS) |

| Vegetables (In million metric tons) | 25.7 (7.66) |

2.73 (0.88) |

17.1 (6.44) |

4.39 (1.48) |

1.66 (3.18 |

23.0 -, * (AMU) |

| Fruits (In million metric tons) | 32.1 (8.64) |

7.174 (1.68 |

20.9 (6.55) |

9.967 (3.82) |

2.34 (3.15) |

24.9 -, * (AMU) |

| Rural population (Per million people) | 130.05 (22.28) |

45.04 (9.44) |

167.23 (26.71) |

61.16 (7.68) |

13. 45 (17 .08) |

122.19 +, * (ECOWAS) |

| Technology (In US$ billion) | 201.35 (126.10) |

15.58 (15.67) |

8.79 (86.12) |

113.26 (92.83) |

13 .94 (33. 77) |

185.77 -, * (AMU) |

| Variable | CD test for methane | Variable | CD test for Nitrous oxide |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methane | 26.349a | Nitrous oxide | 55.142a |

| Cereals | 34.751a | Cereals | 34.751a |

| Roots and tubers | 52.788a | Roots and tubers | 52.788a |

| Vegetables | 55.012a | Vegetables | 55.012a |

| Fruits | 48.092a | Fruits | 48.092a |

| Rural population | 61.085a | Rural population | 61.085a |

| Technology | 80.315a | Technology | 80.315a |

| Variables | Constant | Constant and trend | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | First difference | Level | First difference | |

| Methane | -7.095a | -16.806a | -5.707a | -14.532a |

| Cereals | -5.751a | -17.52a | -4.699a | -15.825a |

| Roots and tubers | -1.413 | -15.427a | -1.893a | -13.645a |

| Vegetables | -2.461a | -12.72a | -0.161a | -7.596a |

| Fruits | -2.675a | -13.738a | -1.85a | -12.591a |

| Rural population | -13.496a | -7.413a | -6.75a | -7.037a |

| Technology | -1.321 | -14.068a | 1.468 | -12.282a |

| Variables | Constant | Constant and trend | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | First difference | Level | First difference | |

| Nitrous oxide | -2.991a | -16.515a | -2.326a | -14.148a |

| Cereals | -5.751a | -17.52a | -4.699a | -15.825a |

| Roots and tubers | -1.413 | -15.427a | -1.893a | -13.645a |

| Vegetables | -2.461a | -12.72a | -0.161a | -7.596a |

| Fruits | -2.675a | -13.738a | -1.85a | -12.591a |

| Rural population | -13.496a | -7.413a | -6.75a | -7.037a |

| Technology | -1.321 | -14.068a | 1.468 | -12.282a |

| Methane | Nitrous oxide | |

|---|---|---|

| Delta | Delta | |

| 23.768a | 16.384a | |

| Adjusted delta | 27.371a | 18.867a |

| Methane | Nitrous oxide | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F(1/0) | F(2/1) | F(3/2) | F(1/0) | F(2/1) | F(3/2) | |

| T – Statistic | 1.71 | 2.26 | 2.39 | 2.62 | 6.97 | 6.62 |

| 1% Critical value | 5.69 | 6.24 | 6.53 | 5.69 | 6.24 | 6.53 |

| 5% Critical value | 4.35 | 4.88 | 5.2 | 4.35 | 4.88 | 5.2 |

| 10% Critical value | 3.72 | 4.32 | 4.65 | 3.72 | 4.32 | 4.65 |

| Detected number of breaks: | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Variable | Short-run elasticity coefficient |

Short-run proportional change coefficient |

Long-run elasticity coefficient | Long-run proportional change coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cereals | 0.4746a | 1.0021 | 0.7739a | 1.0033 |

| (-0.0838) | (-0.2882) | |||

| Roots and tubers | -0.1425 | 0.9994 | -0.162 | 0.9993 |

| (-0.1657) | (-0.1808) | |||

| Vegetables | 0.1651 | 1.0007 | 0.2923 | 1.0013 |

| (-0.1059) | (-0.2462) | |||

| Fruits | 0.4472a | 1.0019 | 0.5403a | 1.0023 |

| (-0.1394) | (-0.192) | |||

| Rural population | -0.1045 | 0.9995 | -0.3394 | 0.9985 |

| (-0.4731) | (-0.581) | |||

| Technology | -0.0152 | 0.9999 | -0.0234 | 0.999 |

| (-0.0244) | (-0.0319) | |||

| Lag of emissions | 0.1336a | |||

| (-0.05) | ||||

| Error correction term | -0.8664a | |||

| (0.4998) | ||||

| F-statistic | 2.78a | |||

| Number of observation | 949 | |||

| Number of member states | 30 | |||

| Variable | Short-run elasticity coefficient | Short-run proportional change coefficient |

Long-run elasticity coefficient |

Long-run proportional change coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cereals | 0.5229a | 1.0024 | 0.8115a | 1.0035 |

| (-0.1096) | (-0.2442) | |||

| Roots and tubers | 0.2877 | 1.0012 | 0.3939 | 1.0017 |

| (-0.3431) | (-0.5061) | |||

| Vegetables | 0.0251 | 1.0001 | 0.1252 | 1.0005 |

| (-0.1343) | (-0.1647) | |||

| Fruits | 0.5784b | 1.0025 | 0.6375 | 1.0028 |

| (-0.2903) | (-0.5519) | |||

| Rural population | 0.9891 | 1.0043 | 0.6514 | 1.0028 |

| (-1.29) | (-1.5189) | |||

| Technology | 0.0131 | 1.0001 | 0.0089 | 1.0000 |

| (-0.016) | (-0.234) | |||

| Lag of emissions | 0.1578a | |||

| (-0.0439) | ||||

| Error correction term | -0.8422a | |||

| ( -0.0439) | ||||

| F-statistic | 1.44a | |||

| Observation | 949 | |||

| Member states | 30 | |||

| Variable | Short-run elasticity coefficient | Short-run proportional change coefficient |

Long-run elasticity coefficient | Long-run proportional change coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cereals | 0.2971a | 1.0013 | 0.3156a | 1.0014 |

| (-0.0634) | (-0.046) | |||

| Roots and tubers | 0.0548 | 1.0002 | -0.0524 | 0.9998 |

| (-0.0675) | (-0.0383) | |||

| Vegetables | 0.1134 | 1.0005 | -0.0854b | 0.9996 |

| (-0.089) | (-0.0405) | |||

| Fruits | 0.2068 | 1.0009 | 0.2171a | 1.0009 |

| (-0.1284) | (-0.0427) | |||

| Rural population | -3.5268 | 0.9849 | 1.1926a | 1.0052 |

| (-5.5204) | (-0.1126) | |||

| Technology | -0.0025 | 1.0000 | -0.0240b | 0.9999 |

| (-0.0096) | (-0.0109) | |||

| Error correction term | -0.3925a | |||

| (-0.0523) | ||||

| Number of observation | 949 | |||

| Member states | 30 | |||

| Variable | Short-run elasticity coefficient | Short-run proportional change coefficient | Long-run elasticity coefficient | Long-run proportional change coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cereals | 0.2921a | 1.0013 | 0.4077a | 1.0018 |

| (-0.0861) | (-0.0438) | |||

| Roots and tubers | 0.246 | 1.0011 | 0.049 | 1.0002 |

| (-0.2246) | (-0.0364) | |||

| Vegetables | 0.1199 | 1.0005 | 0.0359 | 1.0002 |

| (-0.1106) | (-0.0392) | |||

| Fruits | 0.0376 | 1.0002 | 0.1683a | 1.0007 |

| (-0.1161) | (-0.028) | |||

| Rural population | 4.9843 | 1.0218 | 0.7300a | 1.0032 |

| (-2.71466) | (-0.0949) | |||

| Technology | 0.0286a | 1.0001 | 0.014 | 1.0001 |

| (-0.0103) | (-0.0144) | |||

| Error correction term | -0.44144a | |||

| (-0.0586) | ||||

| Number of observation | 949 | |||

| Member states | 30 | |||

| Variable | Short-run elasticity coefficient | Short-run proportional change coefficient |

Long-run elasticity coefficient |

Long-run Proportional change coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cereals | 0.2773a | 1.0012 | 0.3460a | 1.0015 |

| -0.0606 | -0.0746 | |||

| Roots and tubers | -0.1753 | 0.9992 | -0.2123 | 0.9991 |

| -0.2596 | -0.37 | |||

| Vegetables | -0.1113 | 0.9995 | -0.0872 | 0.9996 |

| -0.2973 | -0.376 | |||

| Fruits | 0.5366b | 1.0023 | 0.6454a | 1.0028 |

| -0.2485 | -0.2146 | |||

| Rural population | 1.1224 | 1.0049 | 1.1282 | 1.0049 |

| -1.0674 | -1.088 | |||

| Technology | -0.0436 | 0.9998 | -0.0926 | 1.0004 |

| -0.0369 | -0.0572 | |||

| Error correction term | -0.8383a | |||

| -0.1247 | ||||

| F-statistic | 2.47a | |||

| Number of observations | 251 | |||

| Member states | 8 | |||

| Variable | Short-run elasticity coefficient | Short-run proportional change coefficient |

Long-run elasticity coefficient |

Long-run proportional change coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cereals | 0.2847a | 1.0012 | 0.3504a | 1.0015 |

| (-0.0636) | (-0.0755) | |||

| Roots and tubers | 1.1939 | 1.0052 | 1.359 | 1.0059 |

| (-1.1946) | (-1.3875) | |||

| Vegetables | -0.5678 | 0.9975 | -0.6273 | 0.9973 |

| (-0.3646) | (-0.3695) | |||

| Fruits | 0.1716 | 1.0007 | 0.2329 | 1.001 |

| (-0.6635) | (-0.7807) | |||

| Rural population | 3.4435 | 1.015 | 4.0475 | 1.0176 |

| (-2.3565) | (-2.807) | |||

| Technology | 0.0784 | 1.0003 | 0.0863 | 1.0004 |

| (-0.0677) | (-0.0763) | |||

| Error correction term | -0.8568a | |||

| (-0.0539) | ||||

| F-statistic | 1.08 | |||

| Number of observations | 251 | |||

| Member states | 8 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).