Submitted:

14 October 2024

Posted:

15 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

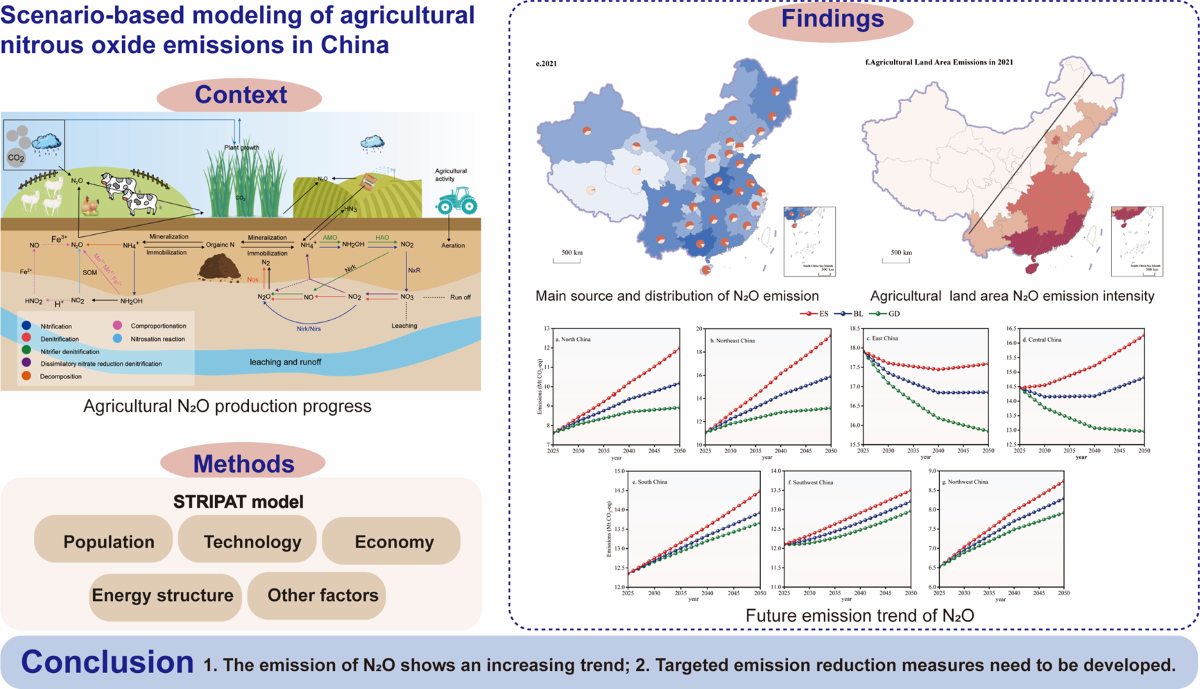

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology and Data

2.1. Methodology

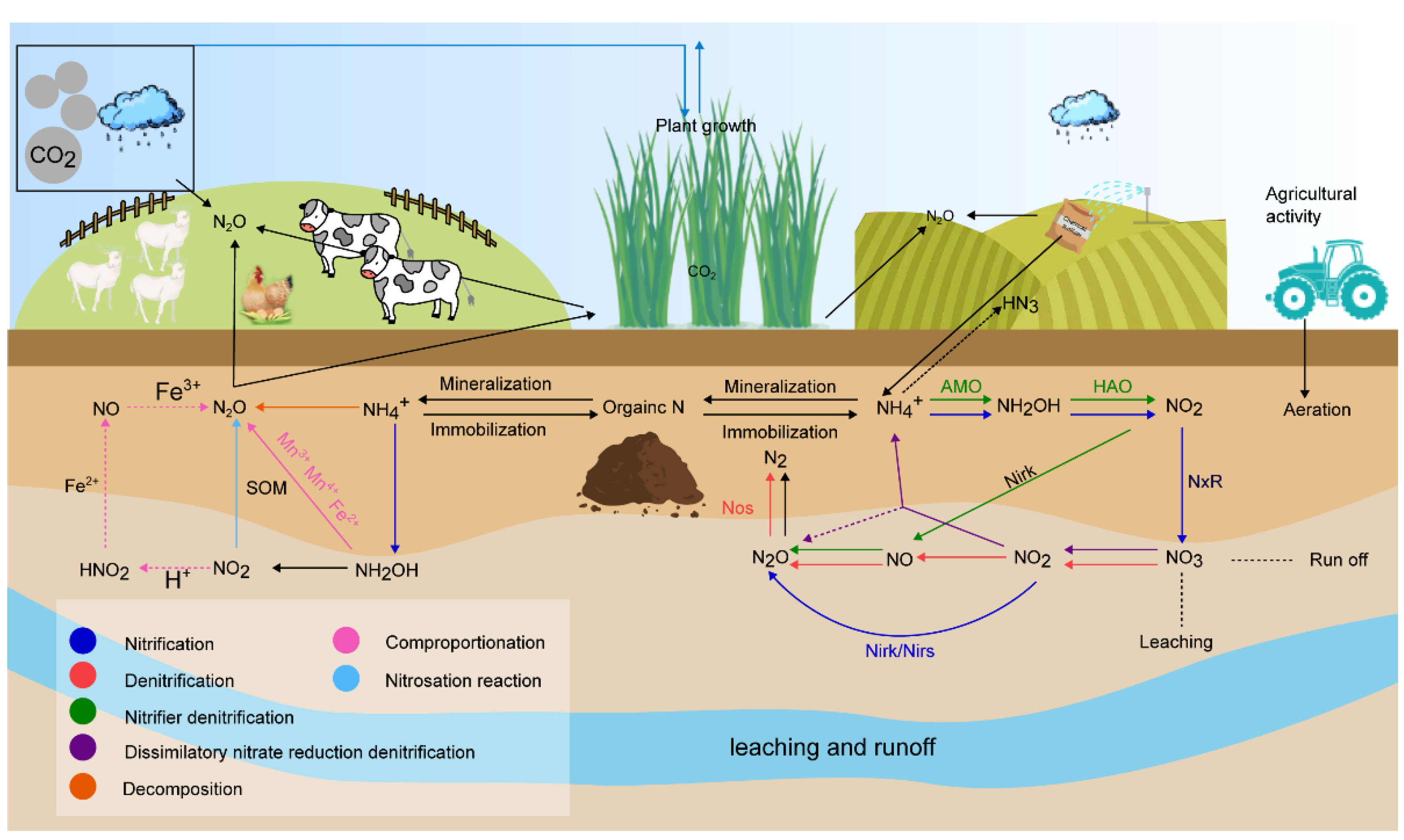

2.2. Accounting Methods for N2O Emissions from Agricultural Land

2.2.1. Direct Emissions

2.2.2. Indirect Emissions

2.3. Accounting Methods for N2O Emissions from Animal Manure

2.4. Accounting Methods for the Intensity of Non-Carbon Dioxide Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Agricultural Activities

2.5. Nitrous Oxide Emission Scenario Prediction Model from Agricultural Activities

2.6. Data

3. Analysis of Results

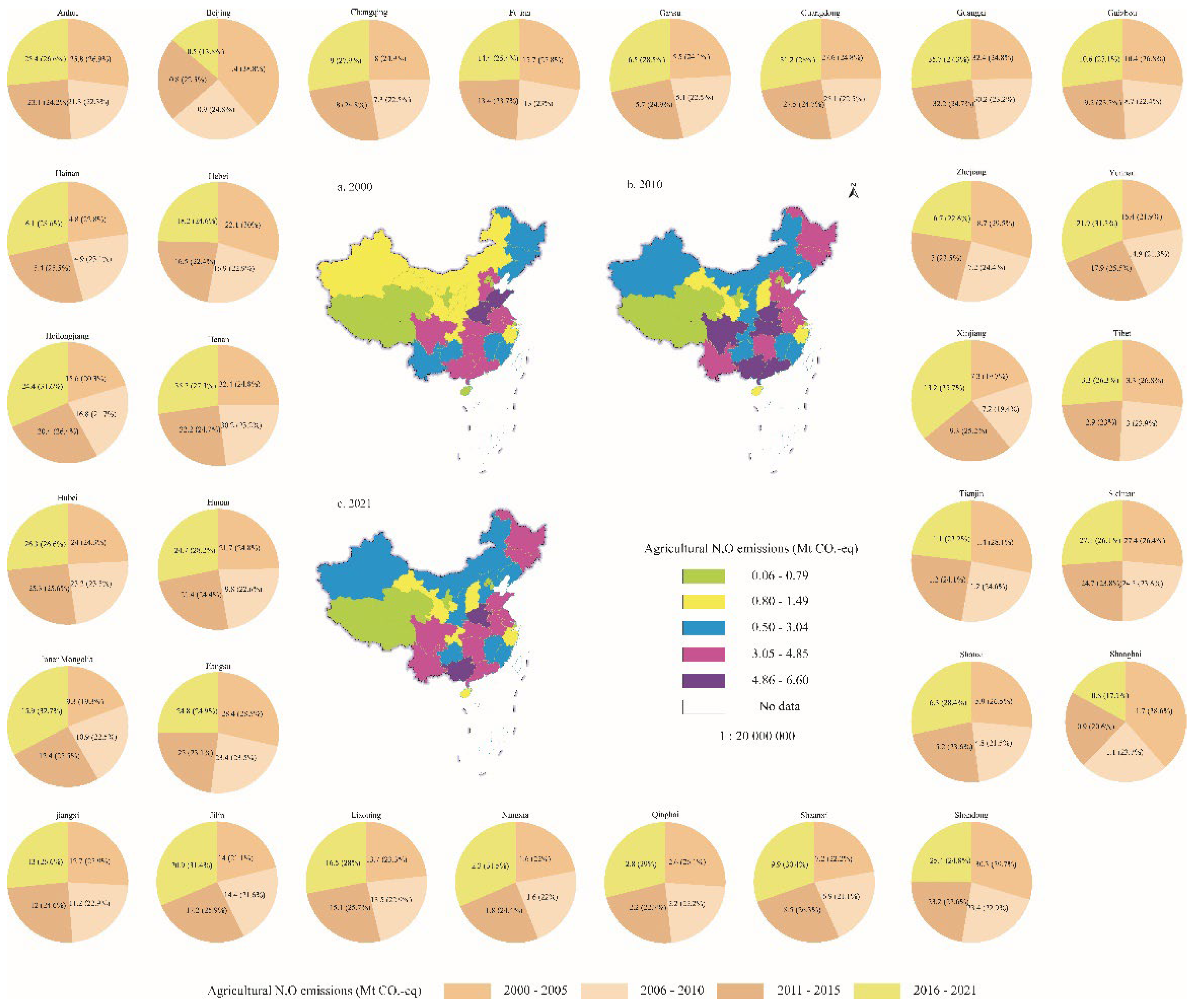

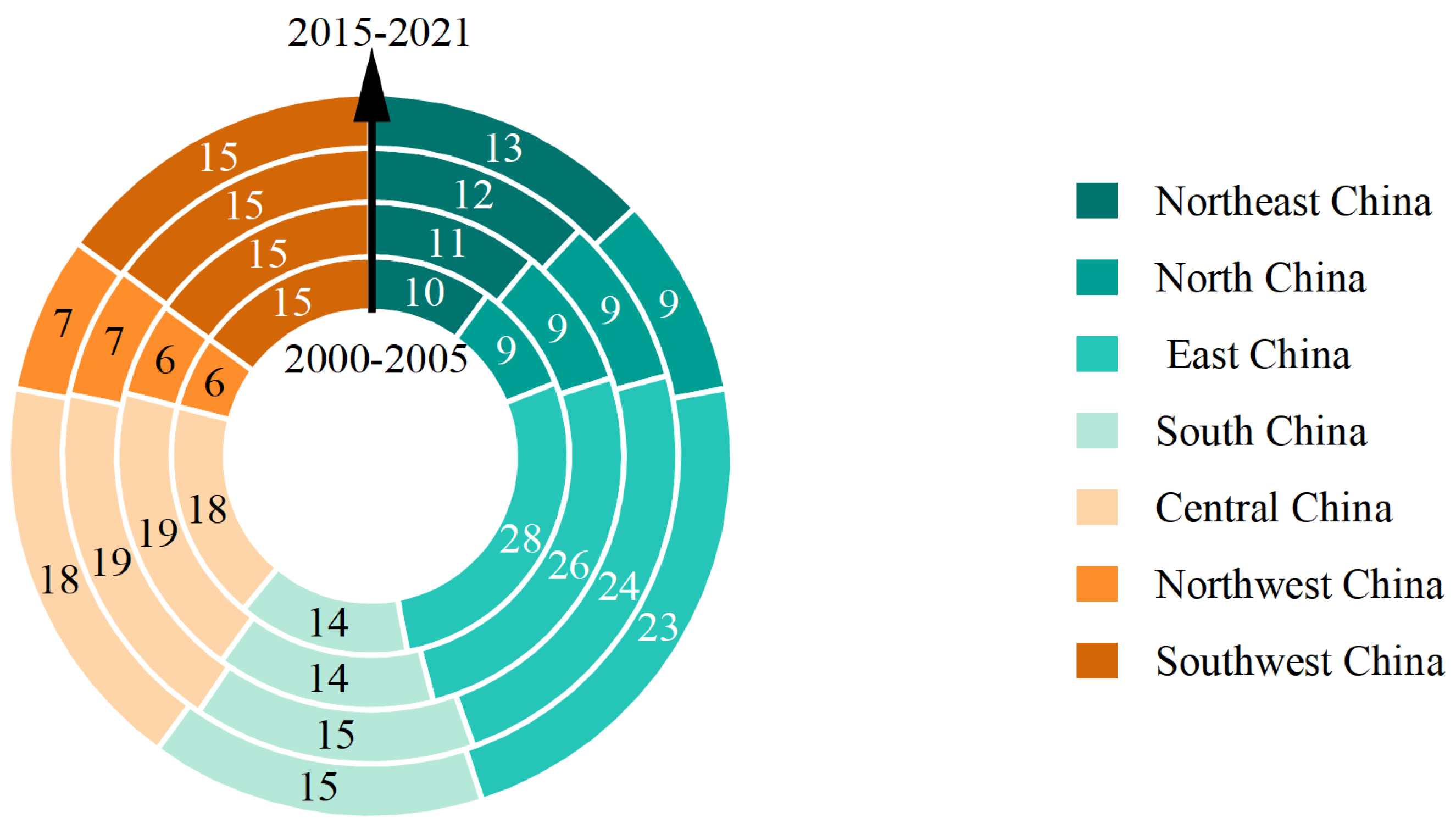

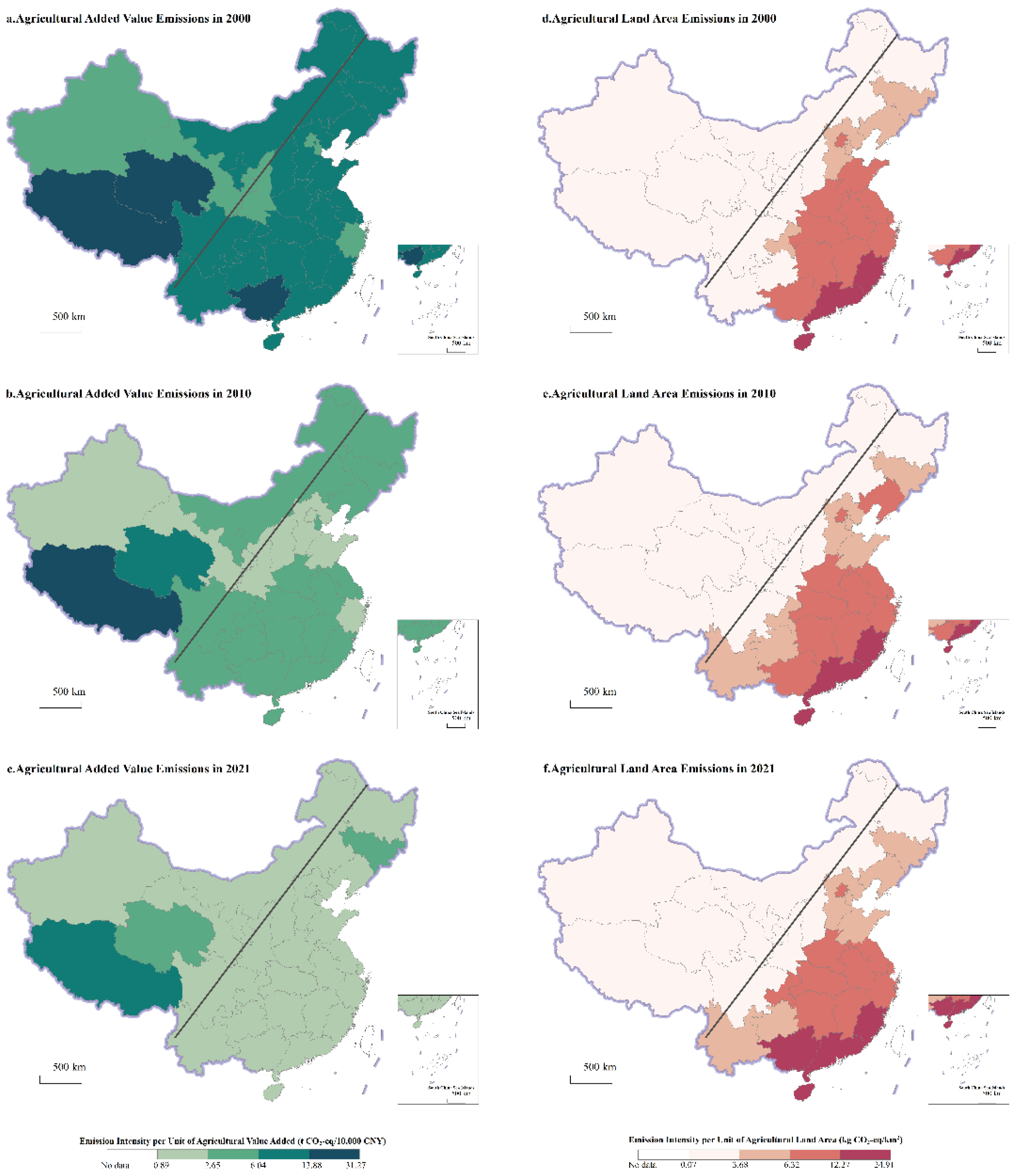

3.1. Evolution of Spatiotemporal Patterns of Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Agricultural Sources

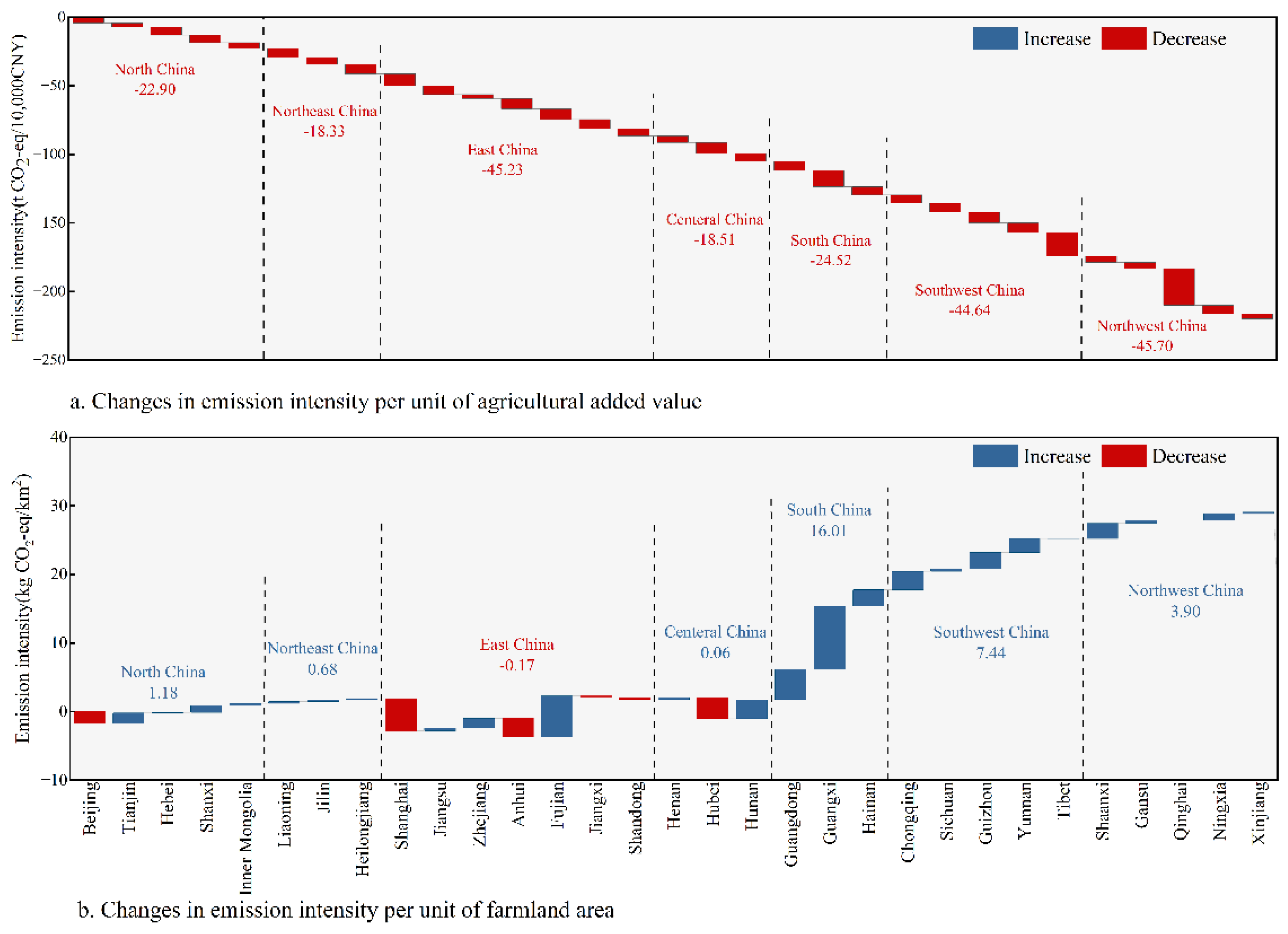

3.2. Changes in the Emission Intensity of Nitrous Oxide Gas from Agricultural Sources

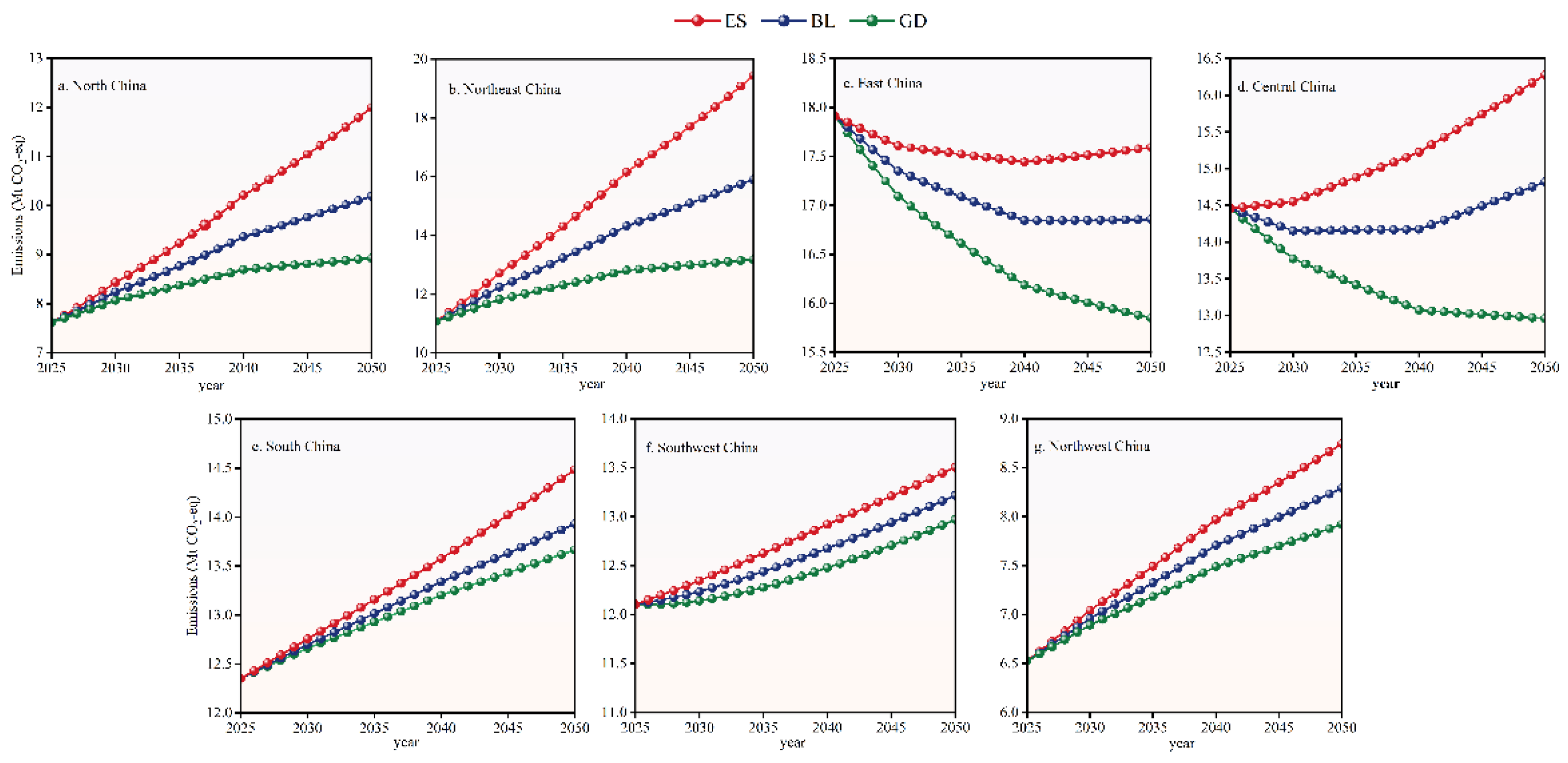

3.3. Nitrous Oxide Emission Scenario Projection from Agricultural Sources

4. Conclusion and Discussion

4.1. Conclusion

4.2. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Declaration of Competing Interest

References

- Sanford, M.; Painter, J.; Yasseri, T.; Lorimer, J. Controversy around climate change reports: a case study of Twitter responses to the 2019 IPCC report on land. Climatic change 2021, 167, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, R. The impact of the rise in atmospheric nitrous oxide on stratospheric ozone: This article belongs to Ambio’s 50th Anniversary Collection. Theme: Ozone Layer. Ambio 2021, 50, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R.L.; Lassaletta, L.; Patra, P.K.; Wilson, C.; Wells, K.C.; Gressent, A.; Koffi, E.N.; Chipperfield, M.P.; Winiwarter, W.; Davidson, E.A. Acceleration of global N2O emissions seen from two decades of atmospheric inversion. Nature Climate Change 2019, 9, 993–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Calvin, K.; Dasgupta, D.; Krinner, G.; Mukherji, A.; Thorne, P.; Trisos, C.; Romero, J.; Aldunce, P.; Barret, K. IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report, Summary for Policymakers. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland. 2023.

- Menegat, S.; Ledo, A.; Tirado, R. Greenhouse gas emissions from global production and use of nitrogen synthetic fertilisers in agriculture. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Yang, J.; Xu, R.; Lu, C.; Canadell, J.G.; Davidson, E.A.; Jackson, R.B.; Arneth, A.; Chang, J.; Ciais, P. Global soil nitrous oxide emissions since the preindustrial era estimated by an ensemble of terrestrial biosphere models: Magnitude, attribution, and uncertainty. Global change biology 2019, 25, 640–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Zhou, Z.; Ren, P.; Xiao, H.; Hu, Z.; Piao, S.; Tian, H.; Tong, Q.; Zhou, F.; Wei, J. Four decades of full-scale nitrous oxide emission inventory in China. National Science Review 2024, 11, nwad285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmsen, J.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Nayak, D.R.; Hof, A.F.; Höglund-Isaksson, L.; Lucas, P.L.; Nielsen, J.B.; Smith, P.; Stehfest, E. Long-term marginal abatement cost curves of non-CO2 greenhouse gases. Environmental Science & Policy 2019, 99, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.; Cain, M.; Frame, D.; Pierrehumbert, R. Agriculture’s contribution to climate change and role in mitigation is distinct from predominantly fossil CO2-emitting sectors. Frontiers in sustainable food systems 2021, 4, 518039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.M.; Sandhu, N.K.; McCoy, S.T.; Bergerson, J.A. A life cycle assessment of greenhouse gas emissions from direct air capture and Fischer–Tropsch fuel production. Sustainable Energy & Fuels 2020, 4, 3129–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Zhang, C.; Hu, M.; Sun, T. Accounting for Greenhouse Gas Emissions in the Agricultural System of China Based on the Life Cycle Assessment Method. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grados, D.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Chen, J.; van Groenigen, K.J.; Olesen, J.E.; van Groenigen, J.W.; Abalos, D. Synthesizing the evidence of nitrous oxide mitigation practices in agroecosystems. Environmental Research Letters 2022, 17, 114024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, L.; Ros, G.H.; Chen, Y.; Yang, X.; Cui, Z.; Liu, X.; Jiang, R.; Zhang, F.; de Vries, W. Global meta-analysis of terrestrial nitrous oxide emissions and associated functional genes under nitrogen addition. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2022, 165, 108523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabregat-Aibar, L.; Niñerola, A.; Pié, L. Computable general equilibrium models for sustainable development: past and future. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29, 38972–38984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, L.; Ma, X.; Qin, Y. Dynamic computable general equilibrium simulation of agricultural greenhouse gas emissions in China. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 345, 131122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Liang, C.; Yang, X.; Shi, Z.; Wang, C. Characterizing Spatial and Temporal Variations in N2O Emissions from Dairy Manure Management in China Based on IPCC Methodology. Agriculture 2024, 14, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Fu, W.; Luo, M.; Chen, J.; Li, L. Calculation and scenario prediction of methane emissions from agricultural activities in China under the background of “carbon peak”. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2022, 1087, 012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.; Havlík, P.; Stehfest, E.; van Meijl, H.; Witzke, P.; Pérez-Domínguez, I.; van Dijk, M.; Doelman, J.C.; Fellmann, T.; Koopman, J.F. Agricultural non-CO2 emission reduction potential in the context of the 1.5 ℃ target. Nature Climate Change 2019, 9, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Roney, C.; Alsalam, J.; Calvin, K.; Creason, J.; Edmonds, J.; Fawcett, A.A.; Kyle, P.; Narayan, K.; O’Rourke, P. Deep mitigation of CO2 and non-CO2 greenhouse gases toward 1.5 ℃ and 2 ℃ futures. Nature communications 2021, 12, 6245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogelj, J.; Lamboll, R.D. Substantial reductions in non-CO2 greenhouse gas emissions reductions implied by IPCC estimates of the remaining carbon budget. Communications Earth & Environment 2024, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Khanna, N.; Liu, X.; Wang, W.; Gordon, J.; Dai, F. Opportunities to tackle short-lived climate pollutants and other greenhouse gases for China. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 842, 156842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Yang, H.; Huang, C.; Ju, X. Effects of nitrogen management and straw return on soil organic carbon sequestration and aggregate-associated carbon. European journal of soil science 2018, 69, 913–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searchinger, T.D.; Wirsenius, S.; Beringer, T.; Dumas, P. Assessing the efficiency of changes in land use for mitigating climate change. Nature 2018, 564, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Gao, C.; Mangi, E.; Ali, C. The potential for bioenergy generated on marginal land to offset agricultural greenhouse gas emissions in China. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 189, 113924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y. What could promote farmers to replace chemical fertilizers with organic fertilizers? Journal of cleaner production 2018, 199, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Development and Reform Commission. Guidelines for the preparation of provincial greenhouse gasinventories (Trial). 2011. http://www.cbcsd.org.cn/sjk/nengyuan/standard/home/20140113/download/shengjiwenshiqiti.pdf.

- Gao, F.; Lv, K.; Qiao, Z.; Ma, F.; Jiang, O. Assessment and prediction of carbon neutrality in the eastern margin ecotone of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2022, 42, 9442–9455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhao, T.; Yuan, R. Scenario simulations for the peak of provincial household CO2 emissions in China based on the STIRPAT model. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 809, 151098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs Issued the “14th Five- Year Plan” National Agricultural Mechanization Development Plan. 2022-01-05. http://www.moa.gov.cn/xw/zwdt/202201/t20220105_6386352.htm.

- Jiang, J.; Zhao, T.; Wang, J. Decoupling analysis and scenario prediction of agricultural CO2 emissions: An empirical analysis of 30 provinces in China. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 320, 128798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| region | range | |

|---|---|---|

| Zone I (Shaanxi, Gansu, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Tibet, Shanxi, Qinghai) | 0.0056 | 0.0015~0.0085 |

| Zone II (Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang) Zone III (Beijing, Shandong, Hebei, Henan, Tianjin) Zone IV (Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Shanghai, Chongqing, Hunan, Sichuan, Jiangxi, Hubei, Anhui) Zone V (Hainan, Guangxi, Fujian, Guangdong) Zone VI (Guizhou, Yunnan) |

0.0114 0.0057 0.0109 0.0178 0.0106 |

0.0021~0.0258 0.0014~0.0081 0.0026~0.022 0.0046~0.0228 0.0025~0.0218 |

| Crop category | Nitrogen content of the grain |

Nitrogen content of straw |

Economic coefficient |

Root-shoot ratio |

Straw returning rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rice | 0.01 | 0.00753 | 0.489 | 0.125 | 0.323 |

| wheat | 0.014 | 0.00516 | 0.434 | 0.166 | 0.765 |

| corn | 0.017 | 0.0058 | 0.438 | 0.17 | 0.093 |

| sorghum | 0.017 | 0.0073 | 0.393 | 0.185 | 0.04 |

| soybean | 0.06 | 0.0181 | 0.425 | 0.13 | 0.093 |

| Hemp | 0.0131 | 0.0131 | 0.83 | 0.25 | 0.093 |

| Potato | 0.004 | 0.011 | 0.667 | 0.05 | 0.3992 |

| rapeseed | 0.00548 | 0.00548 | 0.271 | 0.15 | 0.6185 |

| Vegetable leaves | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.83 | 0.25 | 0.6185 |

| tobacco | 0.041 | 0.0144 | 0.83 | 0.2 | 0.6185 |

| region | dairy cattle | Non-dairy cows | buffalo | sheep | goat | pig | poultry | horse | Donkey/ mule |

camel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Northeast East Central South southwest northwest |

1.846 1.096 2.065 1.710 1.884 1.447 |

0.794 0.913 0.846 0.805 0.691 0.545 |

— — 0.875 0.860 1.197 — |

0.093 0.057 0.113 0.106 0.064 0.074 |

0.093 0.057 0.113 0.106 0.064 0.074 |

0.227 0.266 0.175 0.157 0.159 0.195 |

| variable | Level of | Time period of change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| change (%) | 2025-2030 | 2031-2040 | 2041-2050 | |

| Demographic[27] | low | 0.5 | 0.10 | 1.50 |

| middle | 1.00 | 0.60 | 1.10 | |

| high | 1.50 | 0.20 | 0.70 | |

| GDP per capita[28] | low | 2.50 | 2.0 | 1.50 |

| middle | 3.50 | 3.00 | 2.50 | |

| high | 5.50 | 4.50 | 3.50 | |

| Agricultural mechanization[29] | low | 3.00 | 2.50 | 2.00 |

| middle | 3.50 | 3.00 | 2.50 | |

| high | 4.00 | 3.50 | 3.00 | |

| Effectively irrigated area | low | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.15 |

| middle | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.18 | |

| high | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.21 | |

| Agricultural output value[30] | low | 2.90 | 3.10 | 3.20 |

| middle | 3.30 | 3.50 | 3.60 | |

| high | 3.40 | 3.60 | 3.70 | |

| Rural populations[27] | low | -2.00 | -1.00 | -0.50 |

| middle | -3.50 | -2.00 | -0.50 | |

| high | -5.00 | -3.50 | -2.00 | |

| argument | InI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | Northeast | East | Central | South | Southwest | Northwest | |

| InP | 0.045 | -0.251*** | -0.037 | 0.099 | 0.118*** | 0.112*** | 0.157*** |

| (1.327) | (-6.121) | (-0.434) | (0.898) | (14.522) | (9.655) | (8.487) | |

| lnA | -0.165*** | 0.004 | -0.376*** | -0.071 | -0.032*** | -0.018 | 0.143*** |

| (-6.914) | (0.385) | (-11.397) | (-2.17) | (-3.627) | (-1.241) | (9.016) | |

| lnT | 0.236*** | 0.231*** | 0.065** | -0.049** | 0.268*** | 0.118*** | 0.011 |

| (14.105) | (11.735) | (2.421) | (-1.032) | (22.909) | (5.17) | (0.424) | |

| lnG | 0.417*** | 0.076*** | 0.367*** | 0.085 | 0.239*** | 0.389*** | 0.161*** |

| (26.033) | (4.709) | (9.923) | (1.033) | (22.367) | (16.797) | (8.032) | |

| lnAG | 0.258*** | 0.06*** | 0.5*** | 0.252*** | 0.058*** | 0.01 | 0.055*** |

| (16.899) | (4.534) | (13.442) | (6.405) | (4.837) | (0.794) | (5.895) | |

| lnRP | 0.083*** | 0.065 | 0.146*** | 0.195*** | 0.209*** | 0.137*** | 0.2*** |

| (4.963) | (1.644) | (3.45) | (3.064) | (17.6) | (9.118) | (9.515) | |

| Constant terms | -5.917*** | -0.183 | -3.192*** | -2.468*** | -5.086*** | -4.688*** | -5.296*** |

| (-21.025) | (-0.522) | (-5.857) | (-3.82) | (-52.005) | (-35.53) | (-30.429) | |

| R2 | 0.976 | 0.906 | 0.935 | 0.751 | 0.986 | 0.95 | 0.912 |

| argument | InI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||

| InP | -0.115 | -0.002 | 0.025 | |

| (-1.277) | (-0.026) | (0.28) | ||

| lnA | -0.229*** | -1.262*** | -3.541*** | |

| (-5.557) | (-8.95) | (-4.052) | ||

| (lnA)2 | - | 0.058*** | 0.338*** | |

| (7.634) | (3.18) | |||

| (lnA)3 | - | - | -0.011*** | |

| (-2.642) | ||||

| lnT | -0.027 | -0.052 | -0.054 | |

| (-0.6) | (-1.218) | (-1.266) | ||

| lnG | 0.17*** | 0.183*** | 0.177*** | |

| (3.894) | (4.383) | (4.239) | ||

| lnAG | 0.49*** | 0.521*** | 0.53*** | |

| (13.126) | (14.43) | (14.682) | ||

| lnRP | 0.566*** | 0.52*** | 0.507*** | |

| (8.957) | (8.528) | (8.324) | ||

| Constant terms | -4.952*** | -1.105** | 4.847** | |

| (-29.189) | (-2.087) | (2.095) | ||

| R2 | 0.867 | 0.877 | 0.878 | |

| region | North China, Northeast China |

East China, Central China |

Northwest | South China, Southwest China |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| scene | ES | GD | ES | GD | ES | GD | ES | GD |

| P | high | low | low | high | high | low | low | high |

| A | low | high | high | low | high | low | low | high |

| T | high | low | low | high | low | high | high | low |

| G | low | high | high | low | high | low | low | high |

| AG | high | low | high | low | low | high | high | low |

| RP | low | high | low | high | high | low | low | High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).