1. Introduction

At the Krško Nuclear Power Plant (NPP Krsko), a specific technical challenge has persisted for several years—to prove that regular operator actions as well as unpredicted transients on Steam Generator Blowdown System (BD) will not generate excessive dynamic forces which would result in excessive pipe displacements. As in all high-energy piping systems, the BD system is supported by a combination of fixed and dynamic hangers. These supports accommodate thermal expansion while simultaneously mitigating transient dynamic loads. Ensuring the structural integrity of such piping demands considerable engineering effort to achieve adequate support that allows controlled movement, maintains overall stability, and prevents damage under both normal and off-normal operating conditions.

Support components are routinely subjected to visual inspection for signs of degradation or abnormal behavior.

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show typical pipe support components – sway struts and variable spring. Because the BD piping is located within the containment building, such inspections can be performed only during scheduled refueling outages, which occur every 18 months. Entry into containment during power operation is strongly discouraged due to elevated temperature, humidity, and, most importantly, radiation levels.

Pipe displacement in power plants can arise from several interacting factors, each contributing to the overall dynamic behavior of the piping system:

Thermal Expansion and Contraction: Temperature variations within the piping system cause the material to expand or contract. As the temperature of the conveyed fluid or the surrounding environment increases, the pipe expands; conversely, it contracts when the temperature decreases. These cyclic thermal deformations can induce movement and additional stresses in the piping network, particularly at locations with constrained boundary conditions or insufficient flexibility.

Vibrations and Dynamic Loads: Operational equipment such as pumps, valves, turbines, and compressors generate vibrations and transient dynamic loads. These loads can be transmitted through the piping system, leading to displacements and localized stress concentrations. In adverse conditions, this excitation can even result in resonant vibrations, amplifying the mechanical response and accelerating fatigue or wear of the support components.

Pressure Fluctuations: Rapid pressure changes can also induce significant pipe movements. Pressure surges, water hammer events, or abrupt variations in flow rate produce hydraulic forces that can push or pull the piping beyond its expected limits if the system is not adequately supported or damped.

Seismic Events: For power plants located in seismically active regions, ground motion due to earthquakes represents a major source of dynamic excitation. Seismic loading can induce substantial pipe displacements and impose additional stresses on supports and connecting elements. Proper seismic qualification of supports and structural anchorage is therefore essential to mitigate these effects and to ensure system integrity during seismic events.

To identify under which operating conditions that occurs - and to quantify the actual pipe displacements during plant operation, a dedicated monitoring system for displacement measurement was designed and implemented.

The principal objectives in developing the measurement system were as follows:

to enable precise, real-time measurement of displacements in all three spatial directions (X, Y, Z),

to ensure automatic data acquisition and archiving with subsequent analytical capability, and

to provide continuous access to measurement data without requiring physical entry into the containment building.

The primary challenge was to develop a robust and reliable methodology for measurement, data acquisition, and processing suitable for industrial application under elevated temperature, humidity, and radiation conditions. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this represents the first implementation of such a measurement approach within a nuclear power plant environment—and the first of its kind applied at the NPP Krško.

2. Materials and Methods

Due to its best reliability, linearity and rigidity, special in nuclear applications [

2], a linear variable differential transformer (LVDT) was choosen as the basic element of the measurement chain. Inductive displacement transducers manufactured by Hottinger Baldwin Messtechnik (HBM), type WA/500mm-L. Displacement transducers of the WA-L series with a loose plunger design provide impressively reliable and highly precise measurement results. This type of sensor features a remarkably compact design (in relation to the measuring range). The compact dimensions of the sensor result from an active quarter-bridge circuit based on the differential inductor principle. The bridge is also integrated within the sensor, forming a full-bridge circuit that allows for easy connection of the WA-L transducer to the measuring amplifier. Insensitive to dirt, WA-L displacement transducers feature rugged mechanics and highly stable temperature behavior. This means they can be used in almost all industrial applications, delivering outstanding performance in displacement measurements (HBM, WA-L Displacement Transducers).

Inductive displacement transducers are generally designed to measure displacement along a single direction (the sensor axis). However, in our case, the movement of the observed point on the pipeline follows a spatial trajectory. Theoretically, if the position of the reference point on a reference plane were known, it would be possible to measure the position of the observed point on the pipeline using a single inductive displacement transducer. Such a transducer would need to be flexibly attached on one side to the reference point and on the other side to the observed point that moves. However, in this case, measuring only the change in distance would not be sufficient. To uniquely determine the position of the observed point, it would also be necessary to measure two angles: the angle between the perpendicular projection of the transducer axis onto the reference plane and the transducer axis itself, and the angle between the chosen coordinate axis in the reference plane and the projection of the transducer axis onto that plane [

3].

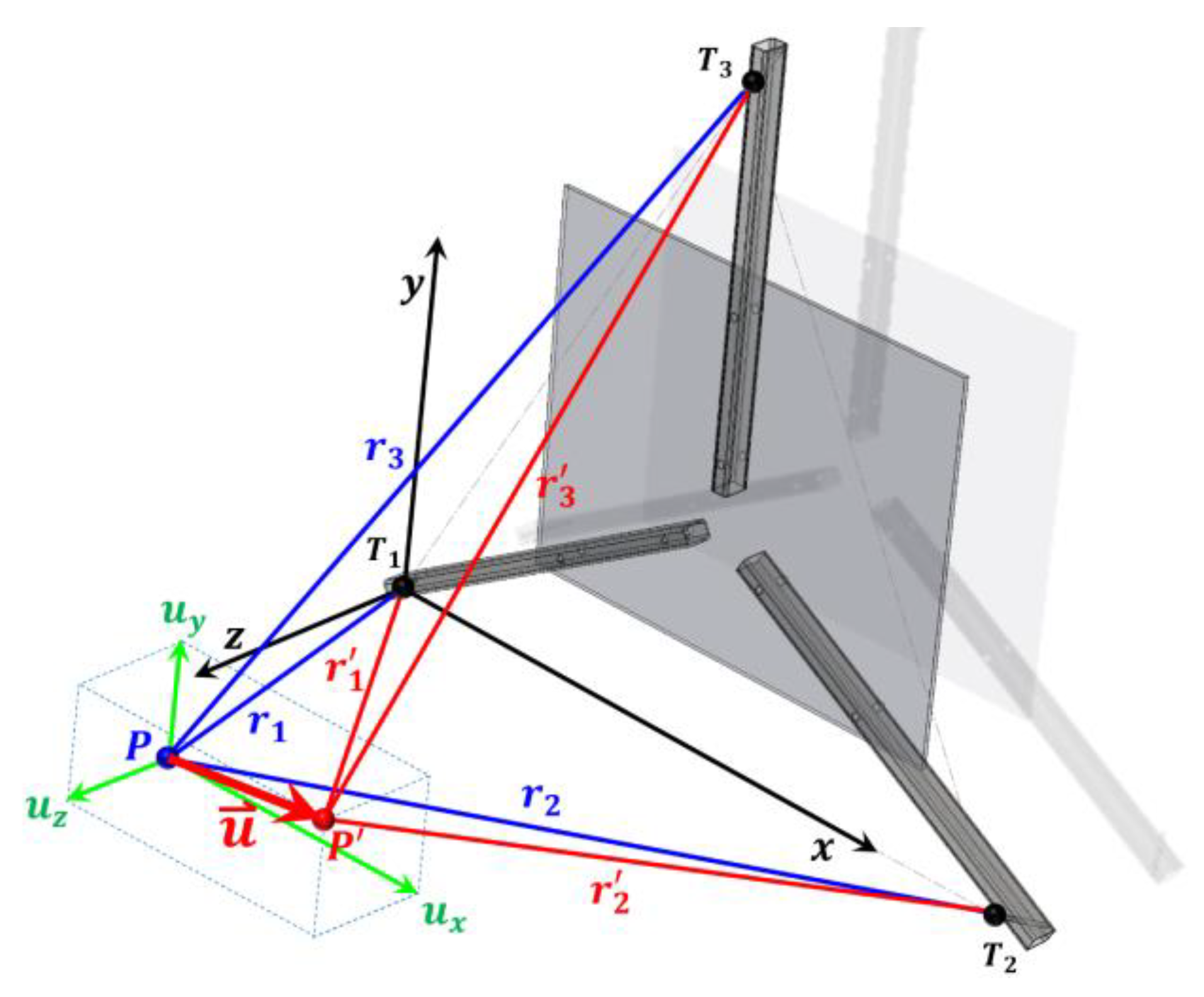

Since continuous real-time measurement of these angles is impractical, we opted to determine the position of the observed point by simultaneously measuring three mutually non-collinear displacements using three inductive displacement transducers. These transducers are rotatably mounted on one side to the reference plane at three points with known coordinates, and on the other side, also rotatably attached to the observed point.

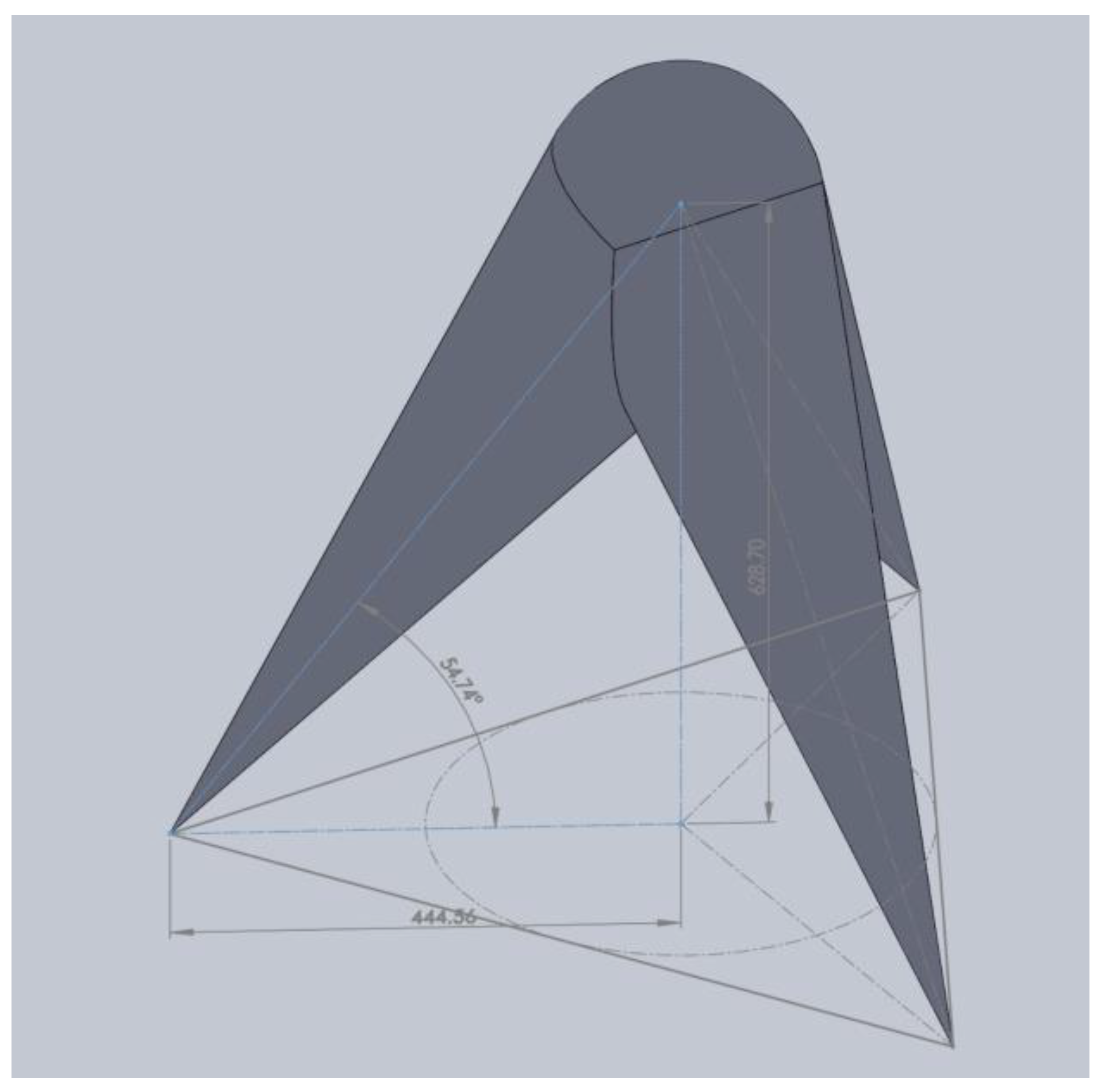

At the same time, it is necessary to consider that the measurements are carried out in a highly radioactive environment, which cannot be accessed during reactor operation. Therefore, the measuring system should not fail under any circumstances, meaning that a sufficiently large operating range must be provided. The system must be robust and capable of delivering reliable results for all theoretically possible positions of the observed points during the operation of the nuclear power plant. Consequently, we first defined the theoretically possible positions of the points in space in the form of a sphere and three cones, which define the volumes within which no obstacles may be present, ensuring the unobstructed operation of the measuring system (

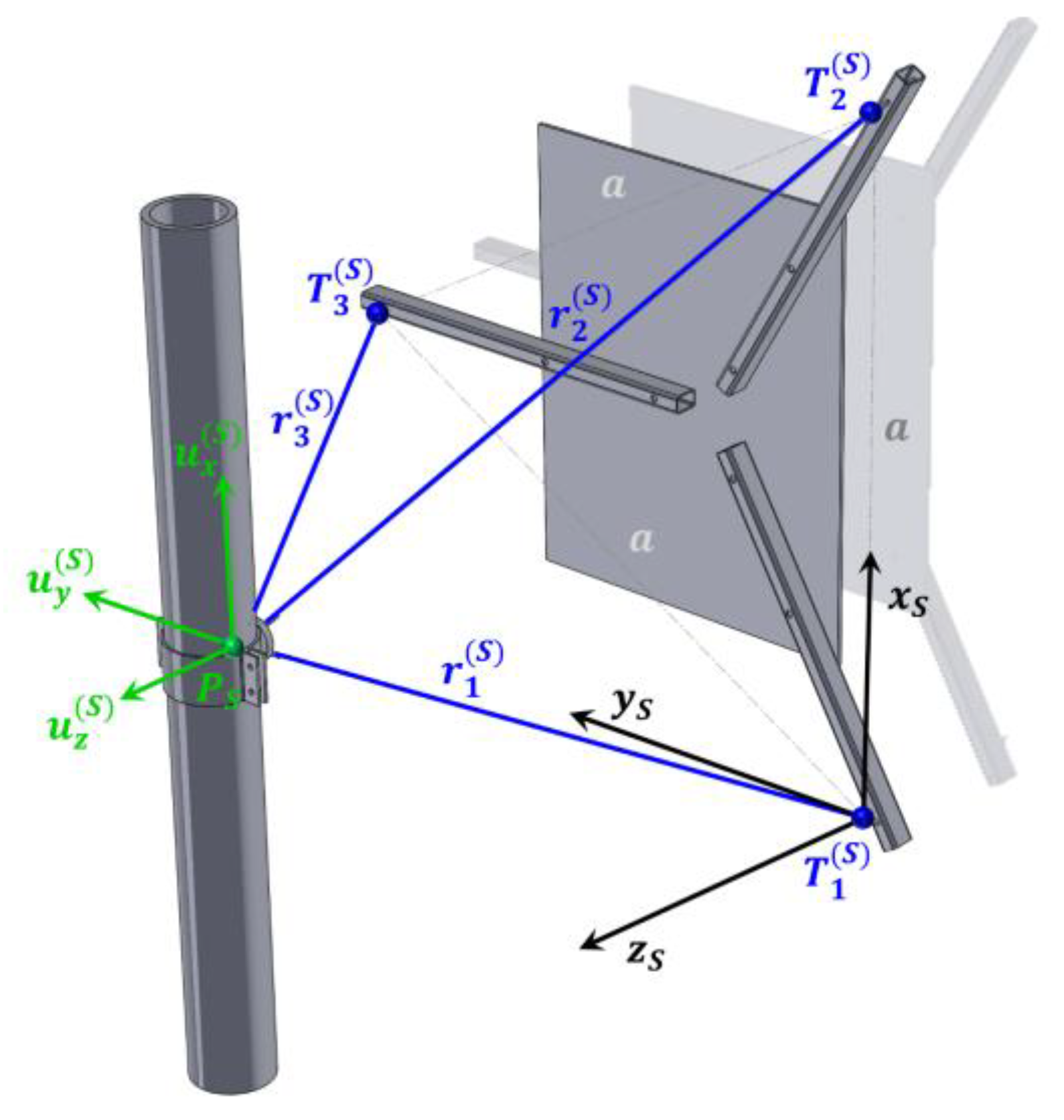

Figure 3).

Based on this, we also defined the measuring range of the individual components of the measurement system. For each observation point, the system consists of three inductive displacement transducers, which are attached on one side to a steel plate - representing the reference plane - using miniature universal (cardan) joints. The plate is mounted vertically so that it is parallel to the straight section of the pipe on which the point being monitored is located. The attachment points of the inductive transducers on the steel plate are arranged at the vertices of an equilateral triangle (Points T

1, T

2 and T

3 in

Figure 3).

At the other end, the inductive displacement transducers are attached to the pipe at the observation point P. The attachment to the pipe is achieved using a special clamp that allows the transducers to be positioned so that, in the initial position, their axes intersect as precisely as possible at point P on the pipe surface. On this side, the transducers are also mounted using identical miniature universal (cardan) joints.

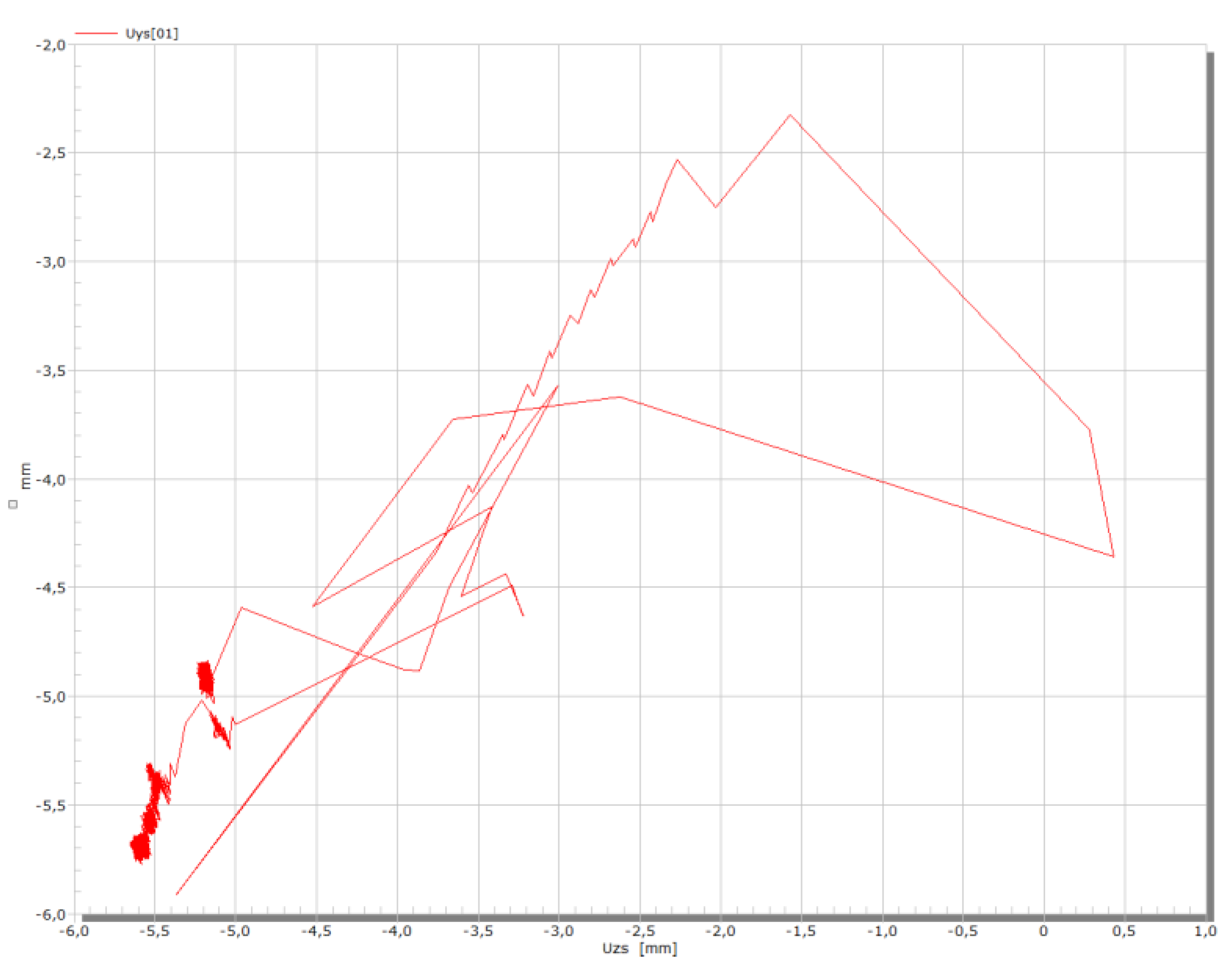

When point P moves to point P’, the inductive transducers measure three non-collinear displacement values for each measuring point. From these, all three displacement components can be determined in the chosen coordinate system (see

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). The coordinate system is always defined such that the x-axis lies along the line connecting points T

1 and T

2; the y-axis is perpendicular to the x-axis within the plane defined by points T

1, T

2 and T

3; and the z-axis is oriented perpendicular to the plane defined by the x and y-axes, forming a right-handed coordinate system.

The displacement components of point P, denoted as u

x, u

y and u

z, are aligned parallel to the respective coordinate axes (see

Figure 4).

Since the origin of the coordinate system is placed at point T_1, based on

Figure 4 we can write equations (1), (2), and (3), which represent a system of equations from which the expressions for the coordinates of the point P(x_P, y_P, z_P) can be determined:

From the difference between equations (1) and (2), we obtain:

From the difference between equations (2) and (3), we obtain:

After substituting equation (4) into equation (5), we obtain:

From equation (1), we express

:

Since points

,

, and

are arranged in the reference plane in the form of an equilateral triangle with side length

, the following relationships can be substituted into equations (4), (5) and (6):

,

and

:

When point

is displaced to point

, the distances

,

, and

change accordingly. These changes in distance can be expressed in the form:

Where

,

, and

represent the values measured by the inductive displacement transducers during the movement of point

to point

. The values of the individual displacement components of point

can be expressed as:

Measurements are performed at two locations. The first location is situated beneath the ceiling on the northern side of reactor building and is marked with the capital letter

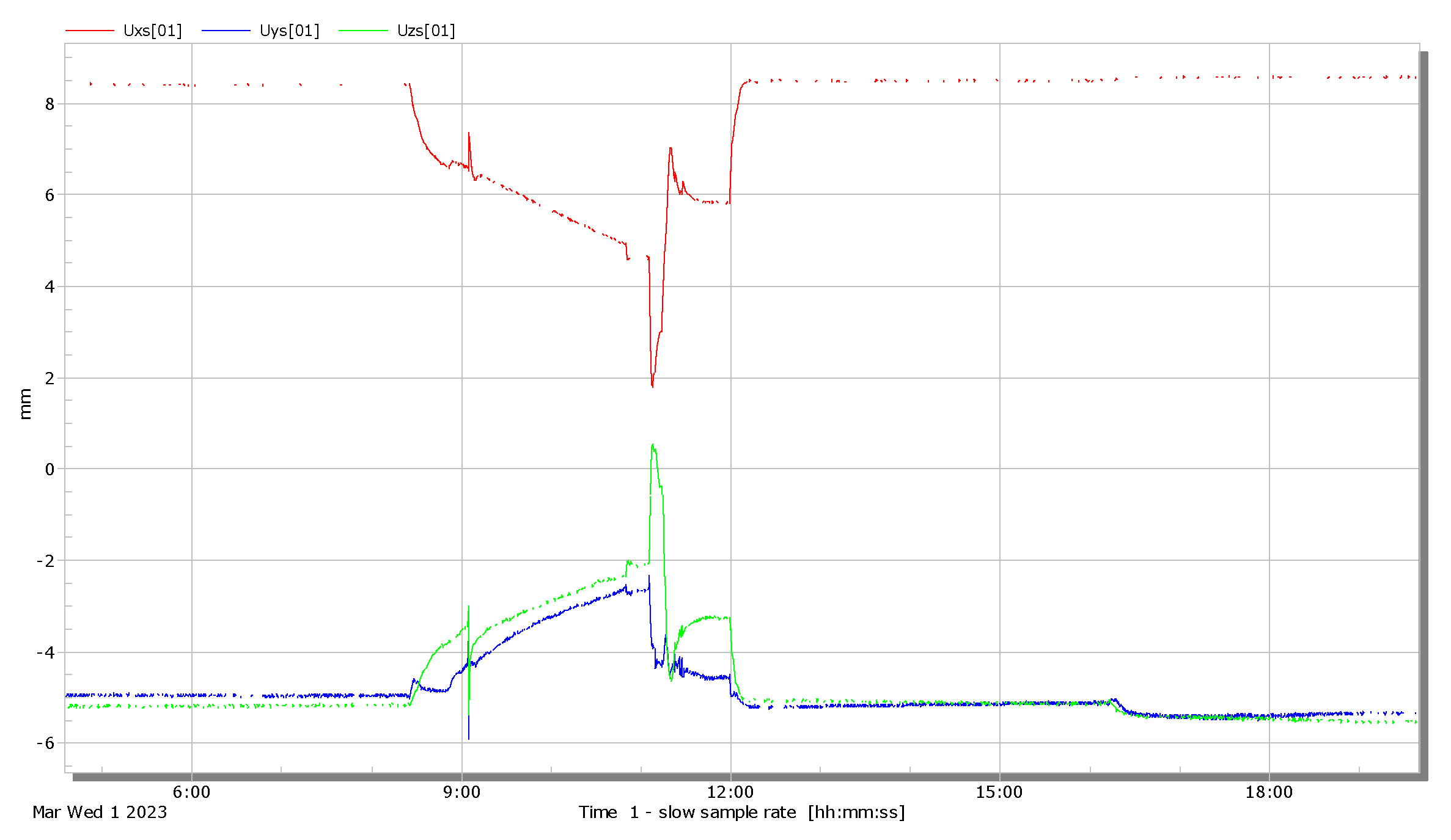

in

Figure 7. The position of the measurement system and the orientation of the local coordinate system are shown in

Figure 5.

The pipe displacement values at location are obtained by substituting the parameters , , and into equations (12), (13) and (14). Since the signal from the inductive displacement transducers, which measure the changes in distances , and , is negative when the length increases, the values , in in equations (12), (13), and (14) are replaced by , and , respectively.

In this way, the resulting expressions can be entered into the CATMAN Easy - AP software tool, which uses the measured three non-collinear displacements to calculate, in real time, the three displacement components of the selected point on the pipe within the coordinate system

:

In the present case, the values measured during the installation of the system at position

are substituted into equations (15), (16) and (17):

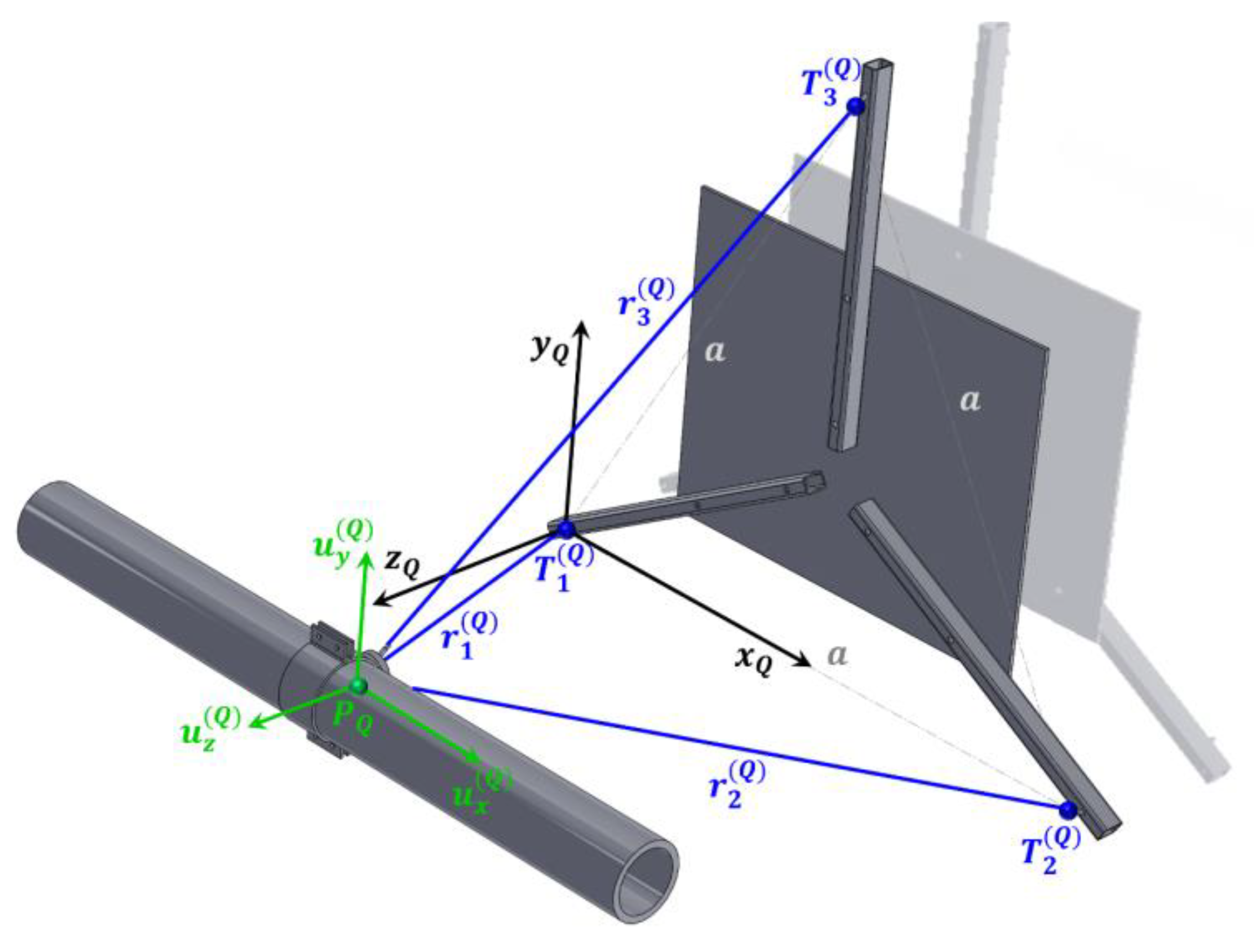

The second location is marked with the capital letter

. The position of the measurement system and the orientation of the local coordinate system at this point are shown in

Figure 6.

The pipe displacement values at location

are obtained by substituting the parameters

,

,

and

into equations (12), (13) and (14). The values

,

in

in equations (12), (13) and (14) are replaced by

,

in

, respectively. The resulting expressions can then be entered into the CATMAN Easy - AP software tool for the real time calculation of the three displacement components of the point

within the coordinate system

:

In the present case, the values measured during the installation of the system at position

are substituted into equations (21), (22) and (23):

Accuracy of the Measurement System

The accuracy of the designed measurement system was also examined. Since the inductive displacement transducers are mounted on both ends using miniature universal (cardan) joints, which exhibit a clearance between 0.1 mm and 0.2 mm, this factor alone introduces a measurement uncertainty on the order of approximately 0.5 mm.

An additional source of measurement error arises from the geometry of the system. It is technically impossible to attach all three inductive transducers to exactly the same point on the pipe - where the observed point is defined - using universal joints for each sensor. As shown in

Figure 8, the attachment points of all three transducers on the pipe are therefore offset by 30 mm from the observed point. For small displacements, the geometric error of the system is practically negligible. However, as the displacement magnitude increases, this error becomes more significant. For large displacements - when the observed point reaches the extreme limits of the measurement range (±250 mm –

Figure 3), particularly in directions parallel to the reference plane - the error can reach up to approximately 3 mm.

Figure 9.

Mounting of the inductive displacement transducers on the pipe at the observation point Q.

Figure 9.

Mounting of the inductive displacement transducers on the pipe at the observation point Q.

At first glance, this might suggest that the overall accuracy of the measurement system is relatively low. However, it should be emphasized that the primary objective was not to develop a high-precision laboratory instrument, but rather a robust measurement system with a large operational range (theoretically corresponding to a spherical volume with a radius of 250 – 300 mm). The system was designed to operate reliably under harsh environmental conditions while still providing dependable information about both the magnitude and direction of pipe displacements, with an accuracy fully sufficient for monitoring pipeline behavior under all operating regimes.

If higher accuracy were required, the same principle of measuring three non-collinear displacements could be retained, while replacing the inductive displacement transducers with three Posiwire encoder-based sensors (manufactured by ASM). In such a configuration, the free ends of the three measuring wires could be attached to the same point on the pipe being monitored, thereby eliminating the geometric offset that is inherent in the current design. However, this alternative arrangement would introduce a new challenge: due to the size and specific geometry of the sensors, it would be extremely difficult to ensure smooth winding and unwinding of the measuring wires in multiple displacement directions. The implementation of a fully rotatable mounting system for all three sensors would therefore be technically very complex.

Data Acquisition

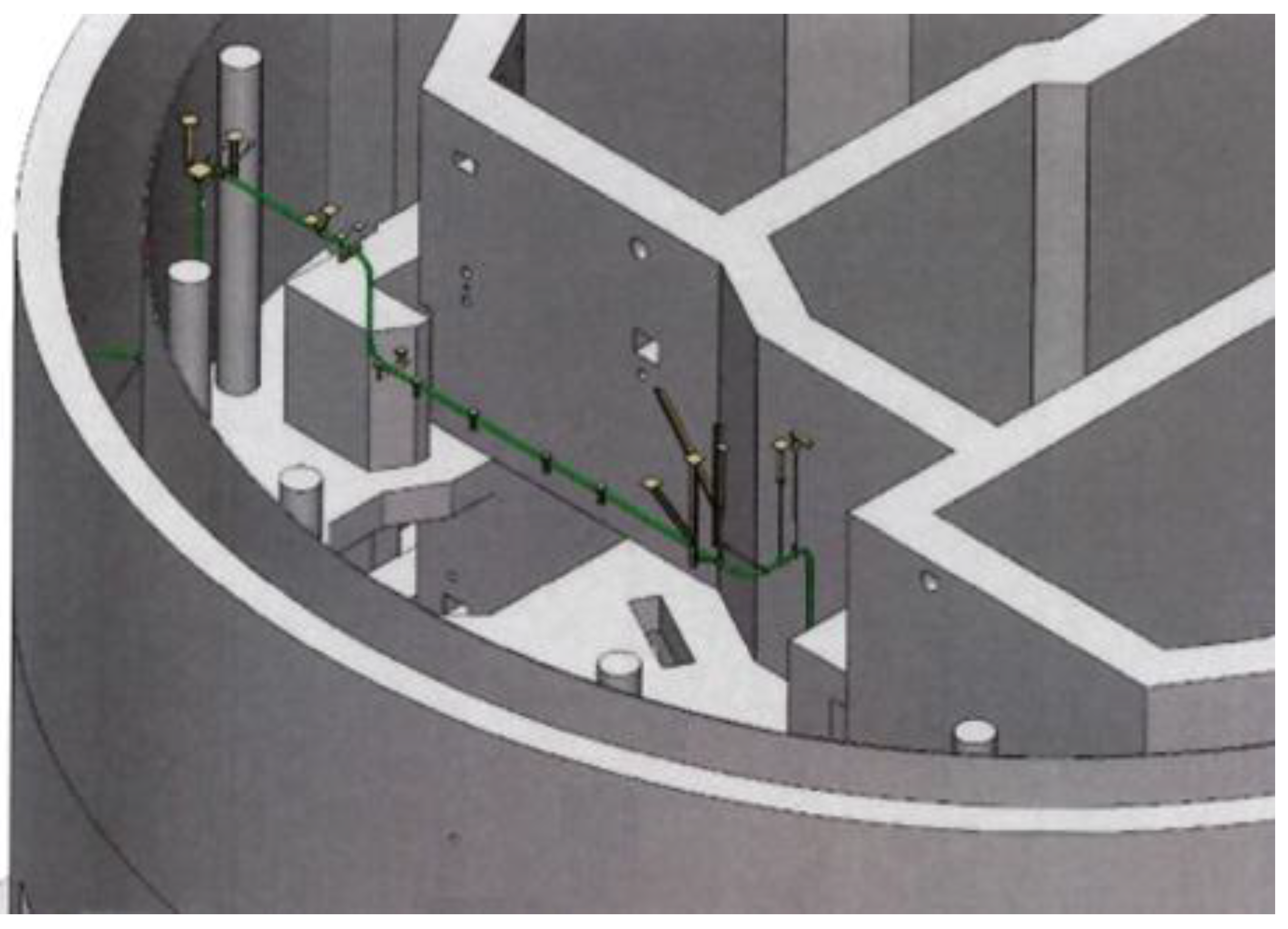

As previously mentioned, the observation points

and

, whose displacements are monitored by the described measuring system, are located inside the reactor building, which cannot be accessed during reactor operation (

Figure 7).

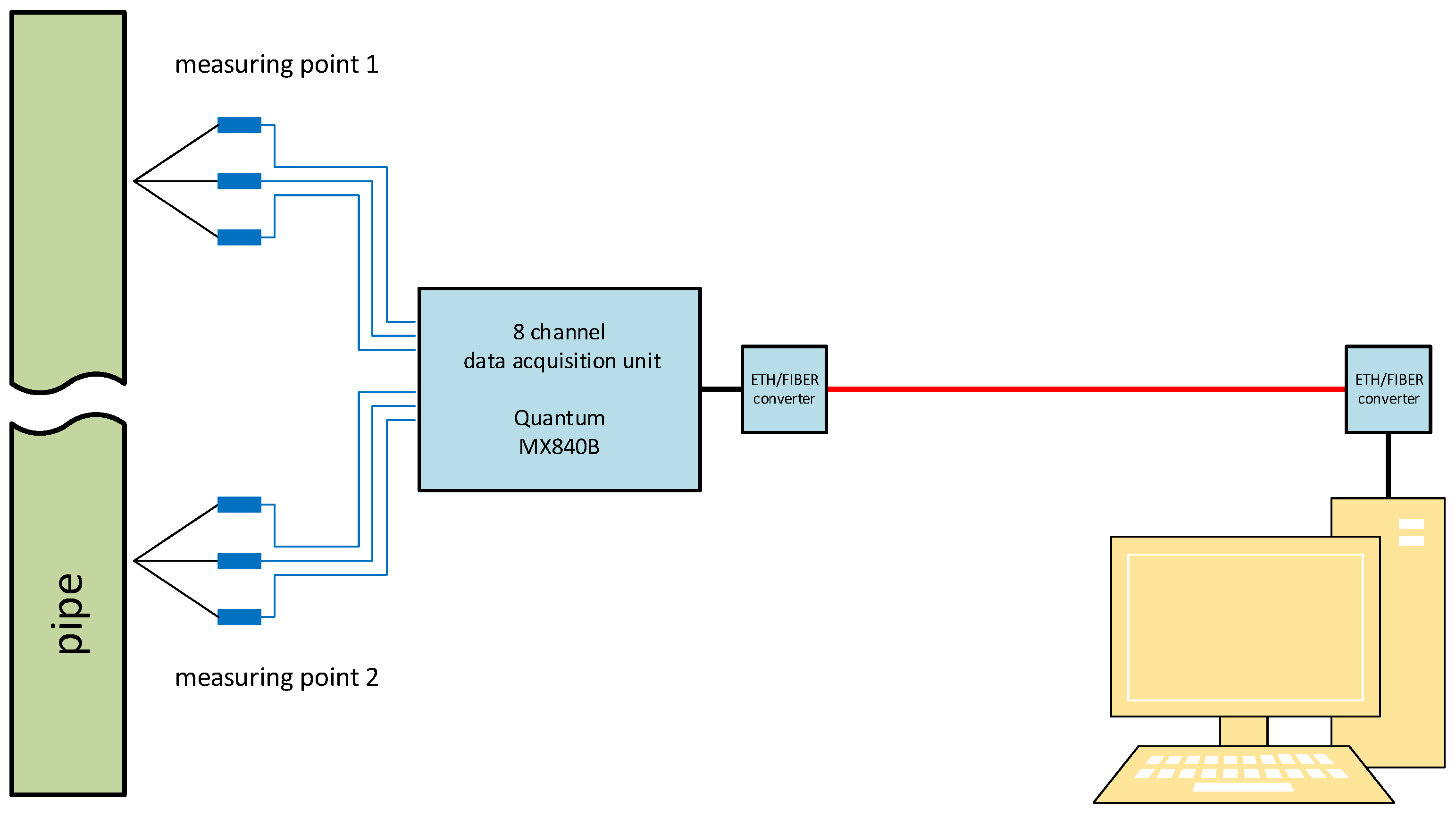

This means that inside the reactor building there are inductive displacement transducers with their supporting structures and a measuring amplifier, whose functions include supplying power to the sensors, data acquisition, amplification, filtering, and conversion of analog signals into digital ones. These digital signals are then transmitted to a personal computer located outside the reactor building, in the plant’s process computer room.

Due to the large distance between the measuring amplifier and the personal computer, communication between them takes place via an existing optical fiber cable, which is otherwise used for communication between the interior of the reactor building and the control room. Therefore, inside the reactor building, next to the measuring amplifier, an Ethernet-to-optical signal converter is installed, while outside, in front of the personal computer, an optical-to-Ethernet signal converter is installed.

Figure 10 shows the layout of the entire measurement system,

Figure 11 shows data acquisition unit used, and

Figure 12 shows a small cabinet, where the universal measurement amplifier HBM QuantumX MX840B (

Figure 11) is located, together with ethernet to optical converters and power supplies. A CATMAN Easy - AP software, running on a personal computer, deals with daq unit communication, recalculating measuring results and archiving all the data in real time. Software application also allows more complex analysis (like FFT etc.), graphical representation and data export. For monitoring unusual spurious displacements, caused by system transients or seismic activity plain time domain graphs are used.

Measurement Configuration

Before performing the measurements, it is necessary to prepare the measurement configuration using the CATMAN Easy–AP software tool. Since six inductive displacement transducers are connected to the measurement amplifier, the corresponding channels were labeled according to the independent variables appearing in equations (18), (19) and (20) as well as (24), (25) and (26). The types of inductive sensors connected to each channel were also defined.

In addition, computational channels were configured, the values of which are continuously calculated in real time based on the measured values from the input channels, following the mathematical relationships entered into the system (in this case, equations (18), (19) and (20) as well as (24), (25) and (26)). For the automatic operation of the measurement system, it was necessary to define the measurement start mode (triggered or manual), as well as the method of storing both the measured and the calculated data (manual or automatic). Furthermore, the location on the computer’s storage medium where the data would be saved was specified, along with the procedure for automatically generating file names for the recorded measurement data.

Considering the nature of the phenomena being monitored by the measurement system, a sampling frequency of 10Hz was selected. The filenames are generated automatically, consisting of a short identifier followed by the date and time of acquisition. The files are saved to the computer’s hard drive every 10 minutes. The method and format of the real-time graphical display of both the measured and the computed results were also defined.

Engineers check the system status several times a week and once a week perform data backup and simple check in any events have occured.

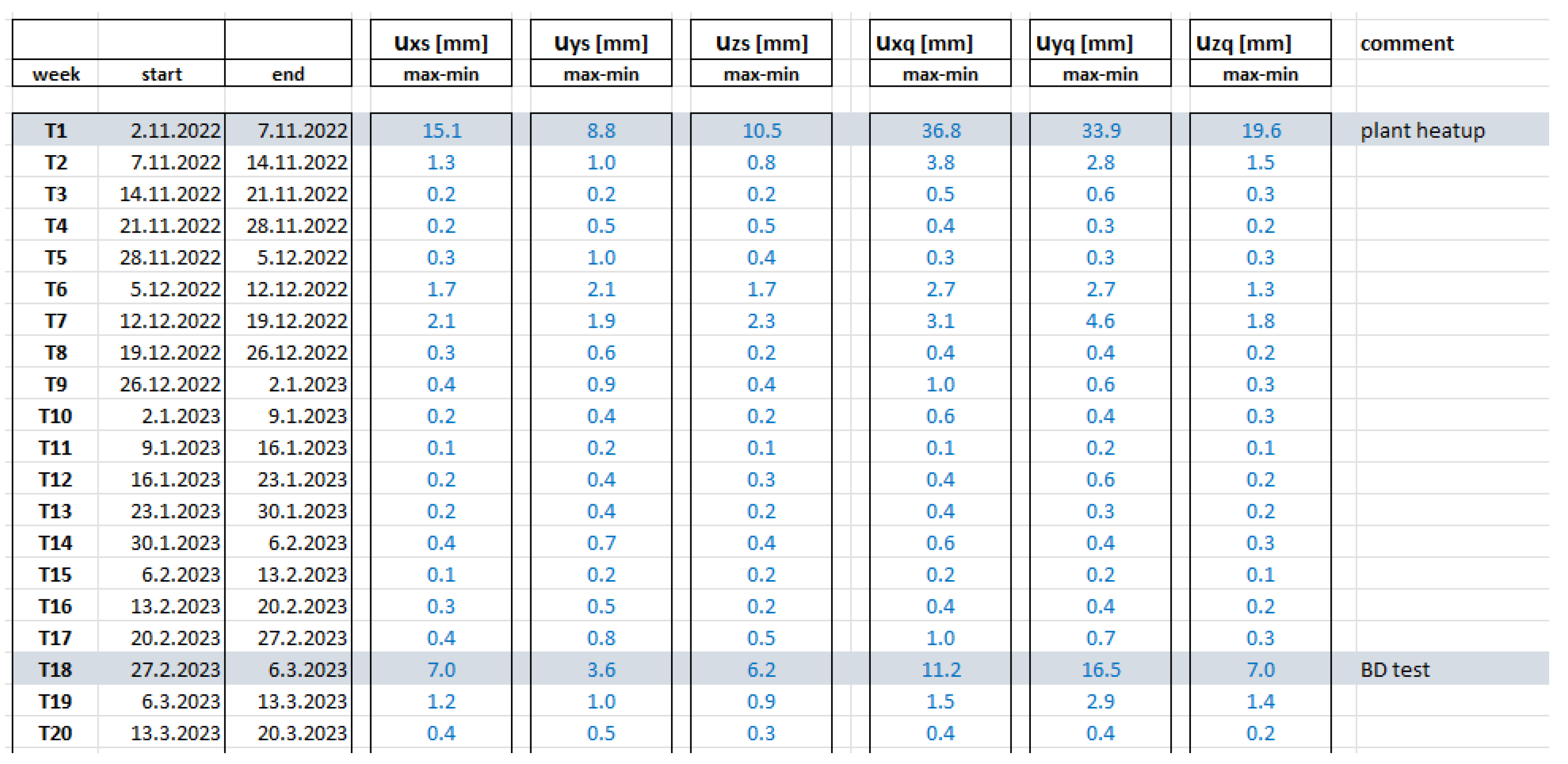

4. Conclusions

In high-energy piping systems commonly employed in power-generation facilities including nuclear, thermal, and hydroelectric plants the implementation of an online displacement monitoring system offers substantial operational and diagnostic benefits. Such systems enable

the verification and optimization of plant operating procedures,

the identification of root causes of potential damage to pipe support structures,

the evaluation of post-transient events, and

the long-term monitoring required for fatigue life assessment of piping components.

To facilitate these functions, a computer-based online displacement monitoring system was developed and implemented at the Krško Nuclear Power Plant. The system was installed on the Steam Generator Blowdown System, a secondary auxiliary subsystem. Two three-dimensional displacement monitoring points were mounted on an 8-inch pipeline conveying a flow rate of 5 to 10 m3/h at a temperature of 180 °C and an operating pressure of 64 bar.

A comprehensive review of available technical literature and industrial applications revealed only one comparable system, which had been implemented on a high-temperature steam pipeline in a gas-fired power plant [

1]. No equivalent implementation was identified in other nuclear power facilities. The referenced system employed a robotic-arm-type three-dimensional displacement sensor comprising two rigid arms connected to a fixed base and equipped with two angular sensors and one rotational sensor. Pipe displacement was derived from the known arm lengths and the measured variations in joint angles.

In contrast, the system developed at Krško applies the three non-collinear vector measurement method, as described previously. This approach provides several advantages, including simplified fabrication and installation, reduced mass of the sensor assembly, and a more straightforward calibration procedure.

The system has been operating continuously for a period of three years without requiring major maintenance interventions or exhibiting significant measurement deviations. These results confirm the suitability, reliability, and robustness of both the adopted measurement methodology and the corresponding hardware architecture.