1. Introduction

Nuclear energy plays a key role in the decarbonization of the economy, as it is a low-carbon (CO₂) energy source. Its use can make a significant contribution to reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the energy sector, which is essential to achieving global climate goals [

1,

2]. In this context, nuclear safety remains a key concern, particularly with respect to the operation of nuclear power plants. The tightness of the fuel element (FE) shell is a critical aspect, as any defects can lead to the leakage of radioactive materials, which threatens the safety of both personnel and the environment [

3].

In scientific articles [

4,

8], it is proposed to obtain dimensionless estimates of the quality of the fuel cladding tightness using nonlinear functions. This approach allows the use of multi-criteria assessment methods, but the proposed functions are complex and have inflection points, which limits their practical use. Studies [

5,

6,

7,

9] also consider the quality assessment of nuclear systems using qualimetry methods, in particular function-dependent statistics, which help to solve practical risk assessment problems. However, to effectively solve practical problems, it is necessary to know the law of distribution of random variables of quality indicators, which usually remains unknown there.

These challenges emphasize the importance of developing new methods that can provide a more accurate and reliable assessment of fuel element shell tightness, which is critical for improving nuclear safety.

The quality of containment inspection is essential to ensure the reliability and safety of nuclear facilities [

10]. Traditional inspection methods, such as acoustic emission or ultrasonic imaging, have their limitations, which can make it difficult to detect defects in a timely manner. Therefore, there is a need to develop new approaches that would eliminate these shortcomings and provide more accurate and efficient control [

11].

The purpose of this paper is to present a fractal-cluster method for controlling the fuel shell geometry, which allows automating the process of detecting defects in real time. This method provides a high-quality analysis of the shell condition and can significantly increase the level of nuclear safety by timely detection of threats to shell integrity. The results of the study show that the implementation of this method can be an important step in improving the quality of the system for monitoring the tightness of the fuel shell of a nuclear reactor at a nuclear power plant.

2. Materials and Methods

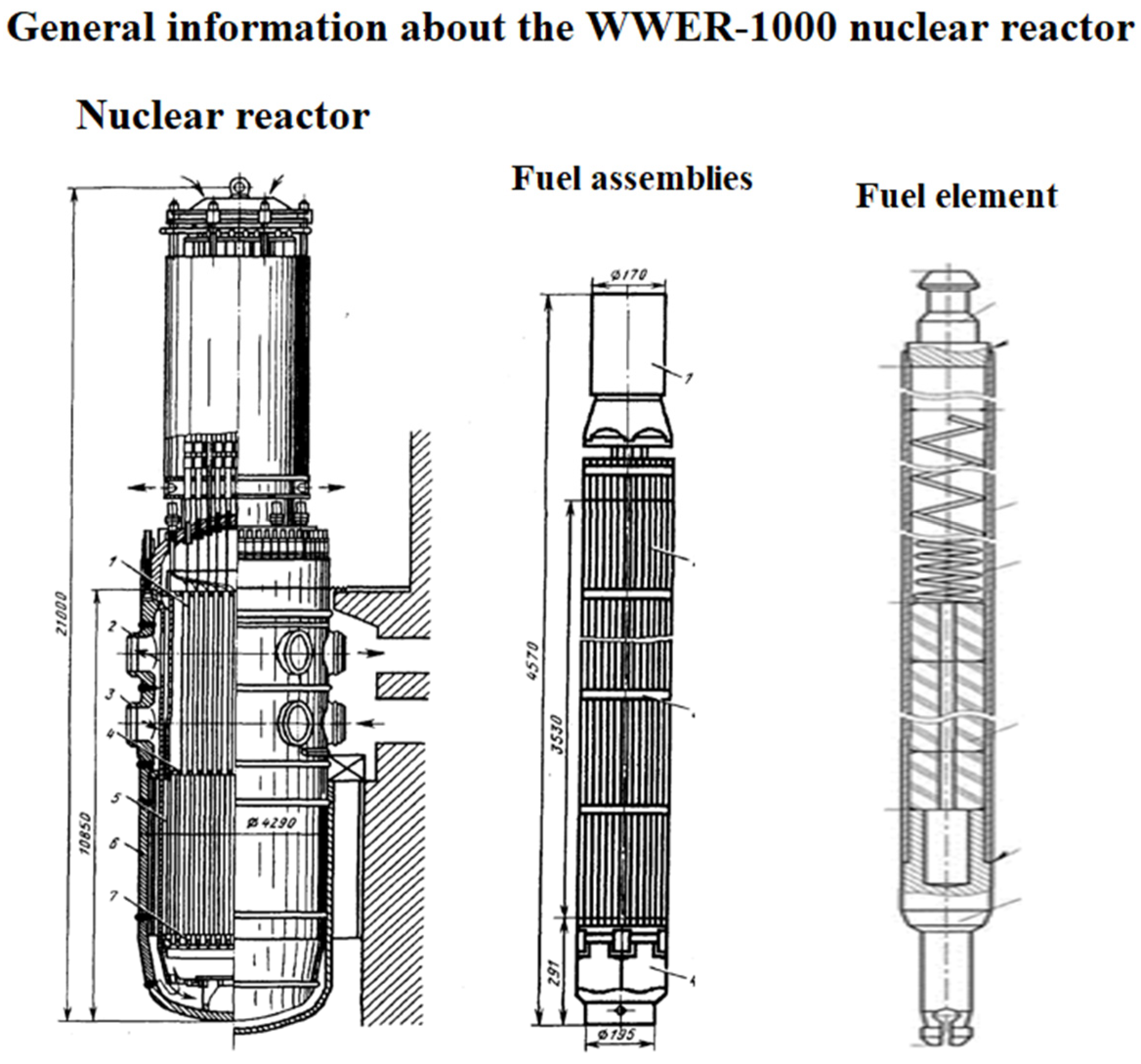

The WWER-1000 nuclear reactor contains 163 fuel assemblies. Each fuel assembly includes up to 300 FEs. Each FE can be depressurized, which will lead to contact of nuclear fuel with the coolant, which is an emergency situation [

12,

13].

Basic physical processes in the structure of the FE shell material that can lead to depressurization: radiation hardening of the material; reduction of material plasticity; radiation creep of the material; radiation growth; thermomechanical interaction between the shell and fuel [

14,

15,

16,

17].

Mechanisms causing damage to the FE shell. Primary hydrogenation of the shell; fretting - corrosion of the shells; debris - damage to the shell; interaction of nuclear fuel with the shell; debris in the coolant; unknown causes (20%) [

18,

19,

20,

21].

To date, the following methods are used to control the tightness of the FE shell:

Acoustic emission. A method based on detecting and analyzing sound waves generated by the formation of cracks or other defects in a material. It allows for continuous monitoring of the FE during reactor operation.

The acoustic emission method, although it provides continuous monitoring, has its drawbacks. First, it is sensitive to external noise, which can distort the results. Secondly, this method is not always able to accurately localize the source of defects, as sound waves can reflect from other structures, complicating the analysis [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

Ultrasonic tomography. The use of ultrasonic waves to obtain three-dimensional images of the internal structure of a FE. It makes it possible to detect defects such as cracks, pores or material inhomogeneities.

Ultrasonography is an effective method for detecting defects, but has limitations in the depth of penetration of ultrasonic waves into the material. This can lead to the missed detection of small cracks or inhomogeneities that are deeper in the structure. In addition, ultrasound requires good surface contact, which can be problematic in the case of worn or contaminated shells [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

Fiber-optic sensors. The use of fiber optic technology to measure temperature, deflections, and vibrations of the FE. Fiber optic sensors are resistant to radiation and allow for real-time monitoring.

Fiber-optic sensors are highly resistant to radiation and can be monitored in real time, but their installation can be complex and costly. In addition, they can be sensitive to mechanical tension, which can lead to false readings [

31,

32,

33].

X-ray computed tomography. A method based on the use of X-rays to obtain three-dimensional images of the internal structure of a FE. It allows detecting defects and assessing changes in the shell geometry.

X-ray computed tomography provides detailed images of the internal structure, but has safety limitations due to the use of ionizing radiation. This can be dangerous to personnel and the environment if used frequently. In addition, the high cost of equipment and operation can be an obstacle to the implementation of this method [

34,

35,

36].

Magnetic tomography. The use of a magnetic field to obtain images of the internal structure of a shell. It allows detecting defects and assessing changes in the magnetic properties of the material, which may indicate mechanical damage.

Magnetic tomography is a powerful tool for detecting defects, but its use is limited in conditions of high background radiation levels, as magnetic fields can be distorted. The method also requires significant time for image acquisition and data analysis [

37,

38,

39].

Hydrostatic method. It involves immersing the fuel assembly in water, where a certain pressure is created. If the shell has defects, air or gases inside the FE escape, forming bubbles on the water surface. This indicates the presence of damage and allows you to assess the integrity of the shell.

The hydrostatic method is simple and effective for detecting fuel shell leaks, but it has its drawbacks: it does not allow determining the exact nature of the defect and is not suitable for assessing internal damage. In addition, this method may not be suitable for shell with large dimensions or complex shapes [

40,

41,

42].

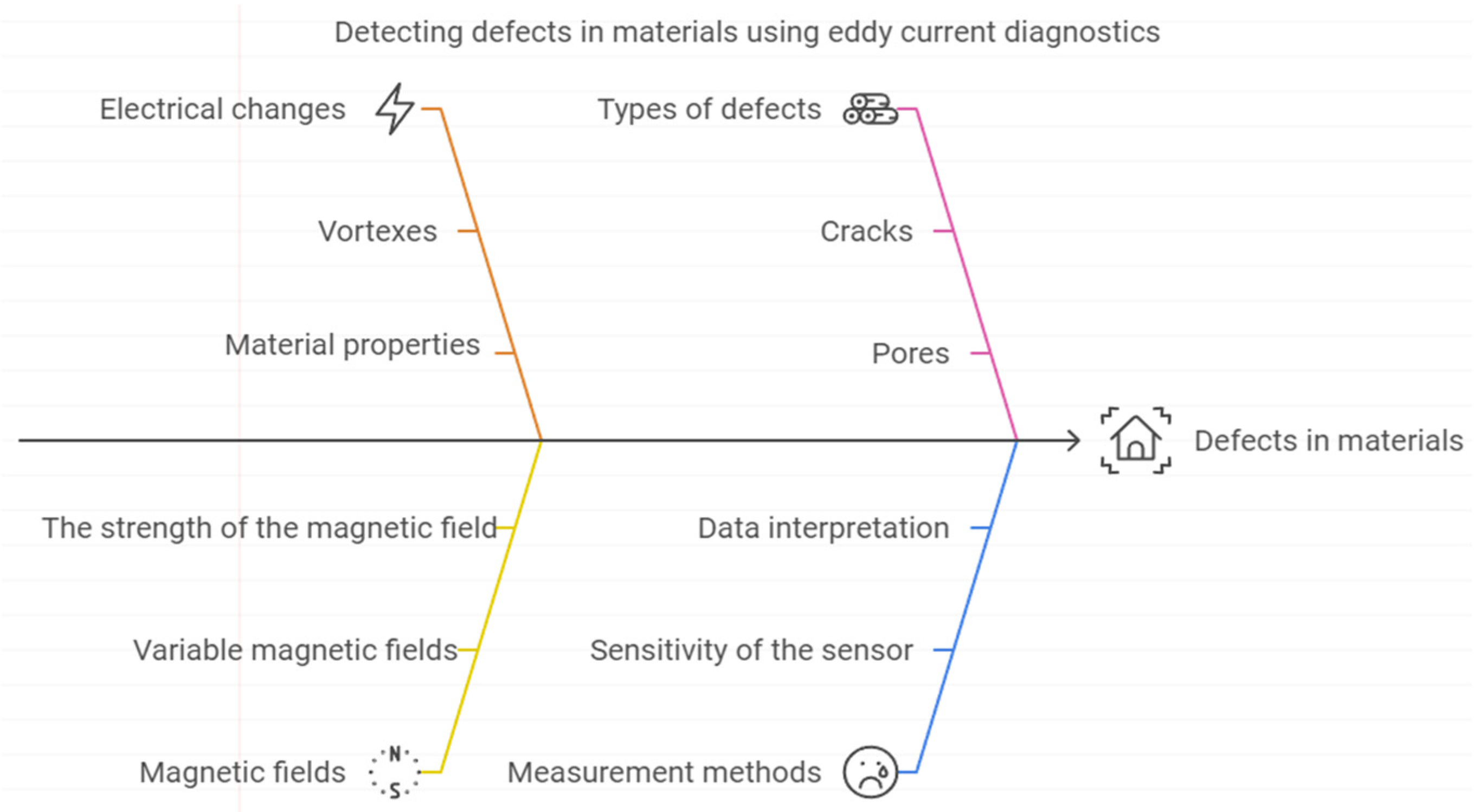

Eddy current detection. It involves detecting changes in electric currents that pass through a material under the influence of an alternating magnetic field. When an alternating current passes through the FE shell, it generates eddy currents that can be distorted by defects such as cracks or pores. Special sensors measure these changes, allowing defects to be detected and their characteristics to be evaluated without destroying the material.

Eddy current flaw detection is an effective method for monitoring the tightness of the FE shell, as it provides high accuracy and real-time monitoring. However, the method has its drawbacks: its effectiveness is reduced in the presence of contamination or corrosion on the surface, which can interfere with accurate measurement. In addition, eddy current flaw detection is not always able to detect defects located deep in the material, as the signal can be attenuated or distorted [

43,

44,

45]. The principle of eddy current flaw detection is shown in

Figure 2.

But all these methods have common disadvantages:

Many inspection methods, such as acoustic emission and eddy current diffraction, are sensitive to external noise and contamination, which can distort the measurement results. Ultrasonic imaging also has limitations in depth penetration, which can lead to the missed defects located deep in the material. Many of these methods are unable to accurately determine the nature of the defects or their impact on the integrity of the shell, which complicates subsequent repair decisions. Some of them require considerable time for analysis, which slows down the monitoring of the FE condition.

The detection of depressurized FEs occurs only after their depressurization, and fission products are detected in the gas collector or coolant, which indicates that fission products have already leaked. At the same time, no clear criteria for the tightness of the shell are established, and control is limited to the outer surface. Most methods require removal of the fuel assembly to inspect each element. All of these methods do not work in an automated mode and do not transmit information to an automated operator’s workstation about the state of the shell’s tightness.

These shortcomings emphasize the need to develop a new method for monitoring the tightness of the FE shell, which will eliminate existing problems and provide more effective control.

3. Experiment

The fractal dimension is an important parameter for assessing the complexity and heterogeneity of the fuel shell surface. In this study, we use fractal analysis to determine the condition of the inner and outer surfaces of the shell, which allows us to detect damage that may affect the safety of nuclear power plants.

The fractal dimension D can be calculated using the box-counting method. According to this method, the fractal dimension is determined by the formula:

where D — fractal dimension; N(e) — the number of boxes (or clusters) with the size that cover the surface; e — box size.

This formula allows you to estimate the number of clusters on the inner and outer surfaces of the FE shell.

3.1. Research Conducted

The following stages were used to conduct the research:

Sample preparation: Several metal hollow tubes of cylindrical shape were selected and subjected to preliminary analysis for the presence of mechanical damage. The samples were cleaned from contaminants to ensure the accuracy of the measurements.

Data collection: The box counting method was used to measure the fractal dimension. For this purpose, the surfaces of the samples were photographed using a high-quality camera with different scales (with different values е).

Image analysis: The images were processed using image analysis software that automatically determined the number of boxes N(e) for each scale.

Calculating the fractal dimension: Based on the obtained data on N(e), we calculated the fractal dimension using the above formulation.

Statistical analysis: To ensure the reliability of the results, we performed a statistical analysis of the obtained values of the fractal dimension, including the calculation of the mean and standard deviation.

3.2. Measurement Results

The studies have shown that the fractal dimension for both the inner and outer surfaces of the FE shell varies from 2.1 to 2.5. This indicates the presence of significant heterogeneity on the surface, which may be the result of mechanical damage or corrosion processes.

The obtained values of the fractal dimension indicate that mechanical damage can have a serious impact on the integrity of the fuel shell. An increase in fractal dimensionality indicates an increase in the number of clusters and their complexity, which can lead to a decrease in heat transfer efficiency and an increased risk of radioactive material leakage.

Cluster density is a critical indicator for assessing the condition of the fuel shell. It reflects the amount of mechanical damage per unit surface area, which can significantly affect the safety and efficiency of nuclear power plants.

3.3. Determining the Density of Clusters

The cluster density can be calculated by the formula:

where:

ρ — cluster density (number of clusters per unit area);

N — total number of detected clusters;

A — surface area (internal or external).

This formula allows you to assess the extent to which the surface of the shell is exposed to damage and is an important indicator for further analysis.

3.4. Research Conducted

To determine the density of clusters in the studied FEs, the following steps were performed:

- 6.

Data collection: After preliminary analysis of the FE samples, measurements were made using imaging techniques such as X-ray computed tomography and ultrasonic scanning. These methods allowed to detect cracks, pores and other clusters on the surface.

- 7.

Image processing: The acquired images were processed using image analysis software that automatically determined the number of clusters N in a given area A.

- 8.

Density calculation: Based on the obtained data on the number of clusters N and the area A, the cluster density was calculated using the above formula.

3.5. Measurement Results

The measurement results showed that the density of clusters on the inner and outer surfaces of the fuel shell varies depending on the operating conditions and operating time. For example:

The data obtained indicate that the inner surface of the shell has a higher density of defects compared to the outer surface. This may be due to the influence of high temperatures and pressures that occur during the operation of the FE. An increase in the density of defects on the inner surface may indicate an increased risk of radioactive material leakage and requires special attention when monitoring the condition of the fuel shell.

Thus, fractal analysis is a powerful tool for monitoring the state of the fuel shell and can be used to timely identify potential threats to the safety of nuclear power plants.

4. Results

A mathematical model was developed to demonstrate the principle of the fractal-cluster method.

The fractal-cluster method can be used to assess the state of the inner and outer surfaces of the FE shell, as well as to analyze their cross-section.

Formulas for calculating the fractal dimension and density of clusters on the surface of the fuel shell were given in the previous section.

For a qualitative calculation of the quality of the shell state, it is necessary to estimate the change in the cross-sectional geometry, which is calculated by the formula:

where:

Router — radius of the outer shell;

Rinner — radius of the inner shell.

This formula allows you to estimate how mechanical damage can affect the cross-sectional area, which in turn will affect heat dissipation and shell integrity.

To estimate the mechanical tensions on the cross-section of the shell, we use the equation for the radial tension

σr

where:

P — internal pressure;

Rinner — radius of the inner shell;

t — shell thickness.

This formula allows us to estimate how the internal pressure affects the mechanical tensions in the shell.

To analyze corrosion damage on the surface of the shell, we use the corrosion rate equation:

where:

v — corrosion rate;

k — corrosion rate constant;

C — concentration of corrosion agent;

n — reaction order.

This formula allows us to assess how corrosion processes affect the integrity of the shell.

The use of these mathematical formulas in the fractal-cluster method allows for a detailed assessment of the condition of the inner and outer surfaces of the fuel shell, as well as their cross-section.

The general formula for the fractal-cluster method of FE shell leakage integrates various aspects, such as fractal dimension, defect density, changes in cross-sectional geometry, mechanical tensions, and corrosion processes:

where:

F — general indicator of the state of the FE shell;

D — fractal dimension of the surface (determines complexity and heterogeneity);

ρ — defect density (number of defects per unit area);

A — cross-sectional area (affects heat dissipation and integrity);

σ — mechanical tensions (assessing the impact of internal pressure);

v — corrosion rate (affects the integrity of the shell);

k1, k2, k3, k4, k5 — weighting factors that reflect the importance of each parameter in the overall shell condition indicator.

These formulas allow integrating various aspects of the fractal cluster method to assess the condition of the fuel shell. They can be used to monitor and assess risks associated with mechanical damage, corrosion, and other factors that affect the tightness of the fuel shell and the safety of nuclear power plants.

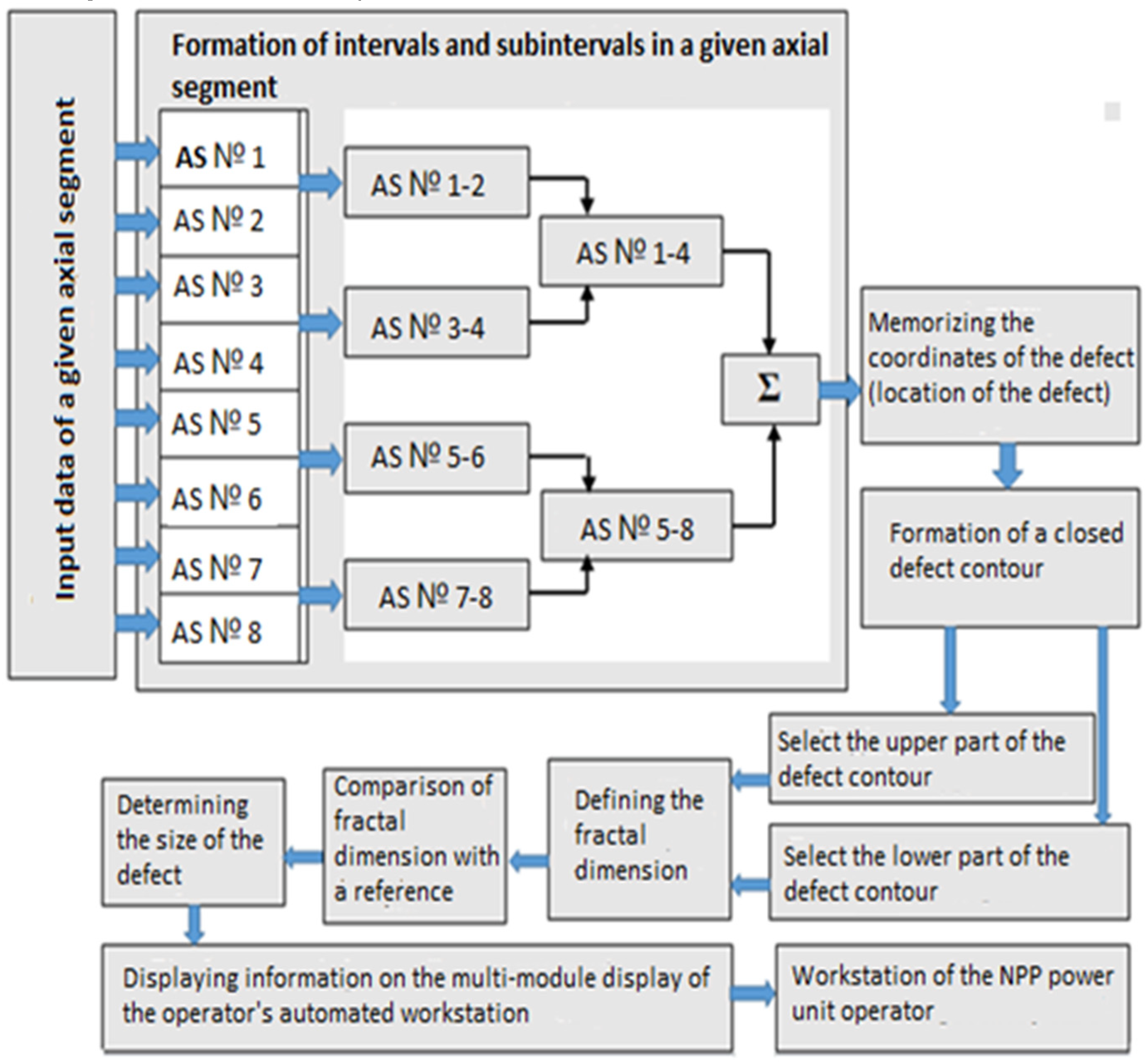

Figure 3 shows a block diagram of the computational module of the fractal cluster method. The FE shell is divided into 8 axial segments; Scanning for defects on the inner and outer surfaces of the shell is performed; Then the coordinates of the defect are stored; The type and size of the defect are detected; It is determined whether the shell is currently leaking; Information is transmitted to the operator’s automated workstation for making an operational decision. All this happens in real time without removing the fuel assembly from the nuclear reactor.

The fractal-cluster method of controlling the tightness of the fuel shell allows performing the analysis without removing the shell from the fuel assembly.

In contrast to the known methods, the fractal cluster method allows to determine whether the shell is tight, whether it is damaged and tight, or whether it is depressurized according to the developed criterion of the FE shell tightness. This, in turn, will reduce the downtime of the nuclear reactor and accelerate the process of scheduled inspection [

46].

The developed method detects defects on the outer and inner surfaces, determines their location on the axial segments, as well as the type and size of defects. The obtained data are compared with the codes of the nuclear reactor pressure vessel leakage system database and transferred to the automated operator workstation in real time [

47].

The method involves measuring several key parameters: fractal dimensionality (D), reflecting the complexity of the surface; density of defects (ρ), which assesses the degree of damage; cluster density (C), measuring the density of defects; and cluster size (Rc), which determines the average size of defects. All of these parameters are measured using specialized imaging equipment that allows detecting defects and evaluating their characteristics without destroying the shell. Thus, the method provides comprehensive monitoring of the fuel shell condition and timely detection of threats to the safety of nuclear power plants.

5. Discussion

The proposed fractal-cluster method for monitoring the tightness of the FE shell demonstrates significant advantages over traditional control methods. One of the main advantages is the ability to continuously analyze the state of the shell without removing it from the fuel assembly. This significantly improves the quality of control and reduces the risks associated with reactor operation.

However, despite its effectiveness, the method has its limitations. For example, the measurement accuracy can be reduced due to contamination or corrosion of the shell surface. It is also important to note that the fractal dimension, which varies from 2.1 to 2.5, indicates surface heterogeneity, which may be the result of mechanical damage or corrosion processes. The high density of clusters on the inner surface of the shell indicates an increased risk of radioactive material leakage.

The conducted studies confirm that the fractal cluster method is a powerful tool for controlling the tightness of the fuel shell. However, to achieve maximum efficiency, it is necessary to take into account external factors that may affect the results of the analysis. Further research should be aimed at improving data processing algorithms and integrating the new method into existing control systems.

Thus, the fractal cluster method can be an important step in ensuring nuclear safety and improving the quality of leakage control of FE shell.

6. Conclusions

The developed fractal-cluster method for controlling the tightness of the FE shell has demonstrated its effectiveness in ensuring high quality control of the shell tightness. The method makes it possible to detect defects on the inner and outer surfaces of the shell without removing it from the fuel assembly directly in the nuclear reactor, which significantly increases the efficiency of response to nuclear safety threats.

The method allows to fully analyze the structure of the shell, to establish a clear criterion for the tightness of the FE shell. The necessary information is transmitted to the automated workstation of the operator in real time to make prompt decisions on the tightness of the fuel shell.

Studies have shown that the fractal dimension varies from 2.1 to 2.5, which indicates a significant surface heterogeneity caused by mechanical damage or other processes. These factors can adversely affect the containment integrity and operational safety of nuclear power plants.

It is recommended to provide regular training for personnel on the use of the new method, as this will increase its effectiveness.

Thus, the fractal cluster method has the potential to become an important tool for improving the quality of control of fuel shell leakage, which will help to strengthen nuclear safety and reduce risks associated with the operation of nuclear facilities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.K., R.T., R.G. and J.N.; methodology, E.K. and R.T.; validation, E.K., R.T., R.G. and J.N.; formal analysis, E.K., R.T., R.G. and J.N.; investigation, E.K. and R.T.; resources, E.K. and R.T.; writing—original draft preparation, E.K., R.T., R.G., J.N.; writing—review and editing, E.K., R.T., R.G. and JN.; visualization, E.K., R.T.; supervision, R.G. and J.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partly conducted in the framework of the project No. WZ/WIZ-INZ/2/2022 of Bialystok University of Technology and financed from the subsidy granted by the Minister of Education and Science of the Republic of Poland.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analysed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aszódi, A.; Biró, B.; Adorján, L.; Dobos, C.; Illés, G.; Tóth, N.K.; Zagyi, D.; Zsiborás, Z.T. The effect of the future of nuclear energy on the decarbonization pathways and continuous supply of electricity in the European Union. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2023, 15, 112688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodakowska, E.; Nazarko, J. Assessing the Performance of Sustainable Development Goals of EU Countries: Hard and Soft Data Integration. Energies 2020, 13, 3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyuzhny, A. , Krapivsky, P. Cluster-cluster aggregation with mobile clusters: Scaling and crossovers. Phys. Rev. E 2019, 100, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupriyanov, O. , Trishch, R., Dichev, D., Kupriianova, K. A General Approach for Tolerance Control in Quality Assessment for Technology Quality Analysis. Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering. 2023; pp. 330–339. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-16651-8_31.

- Trishch, R. , Nechuiviter, O., Hrinchenko, H., Bubela T., Riabchykov, M., Pandova, I. Assessment of safety risks using qualimetric methods. MM Science Journal, 2023; 10, pp. 6668–6674. https://www.mmscience.eu/journal/issues/october-2023/articles/assessment-of-safety-risks-using-qualimetric-methods.

- Trishch, R.; Cherniak, O.; Zdenek, D.; Petraskevicius, V. Assessment of the occupational health and safety management system by qualimetric methods. Eng. Manag. Prod. Serv. 2024, 16, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherniak, O. , Trishch, R., Ginevičius, R., Nechuiviter, O., Burdeina, V. Methodology for Assessing the Processes of the Occupational Safety Management System Using Functional Dependencies. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, 2024; 996 LNNS, pp. 3–13. [CrossRef]

- Kupriyanov, O. , Trishch, R., Dichev, D., Bondarenko, T. Mathematic Model of the General Approach to Tolerance Control in Quality Assessment. Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering, 2022; pp. 415–423. [CrossRef]

- Ginevicius, R. , Trishch, R., Remeikiene, R., Gaspareniene, L. Complex evaluation of the negative variations in the development of Lithuanian municipalities. Transformations in Business and Economics, 2021; 20(2), pp. 635–653. https://openurl.ebsco.com/EPDB%3Agcd%3A9%3A19160761/detailv2?sid=ebsco%3Aplink%3Ascholar&id=ebsco%3Agcd%3A153885468&crl=c.

- Qian, G.; Liu, J. Fault diagnosis based on gated recurrent unit network with attention mechanism and transfer learning under few samples in nuclear power plants. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2023, 155, 104–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorina, C.; Clifford, I.; Kelm, S.; Lorenzi, S. On the development of multi-physics tools for nuclear reactor analysis based on OpenFOAM®: state of the art, lessons learned and perspectives. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2022, 387, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, P.; Huang, X.; Li, S.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, X. Real-time reliability analysis of micro-milling processes considering the effects of tool wear. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 200, 110–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Lu, M. Bidirectional Shrinkage Gated Recurrent Unit Network With Multiscale Attention Mechanism for Multisensor Fault Diagnosis. IEEE Sensors J. 2023, 23, 25518–25533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belles, R. Key reactor system components in integral pressurized water reactors (iPWRs). In Handbook of Small Modular Nuclear Reactors. 2021; pp. 95–115. [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Zhang, T.; Ji, S.; Luo, M.; Gong, J. BuildMapper: A fully learnable framework for vectorized building contour extraction. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote. Sens. 2023, 185, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Qian, G. Hierarchical FFT-LSTM-GCN based model for nuclear power plant fault diagnosis considering spatio-temporal features fusion. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2024, 171, 105–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshkbar-Bakhshayesh, K.; Mohtashami, S. Classification of NPPs transients using change of representation technique: A hybrid of unsupervised MSOM and supervised SVM. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2019, 117, 103–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhou, Z.; Li, S.; Sun, C.; Yan, R.; Chen, X. The emerging graph neural networks for intelligent fault diagnostics and prognostics: A guideline and a benchmark study. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2022, 168, 108653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Shao, H.; Min, Z.; Peng, J.; Cai, B.; Liu, B. FGDAE: A new machinery anomaly detection method towards complex operating conditions. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 109–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, J.M.; Prabhu, F.F.; Suresh, R.; Gopinathan, R.; Nasrulla, S.M.; Joshi, K.A.; Subbiah, R. Investigating the performance of a NMPCM integrated heat sink for chipset cooling. Mater. Today: Proc. 2023, 52, 1234–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovera, A.; Tancau, A.; Boetti, N.; Vedova, M.D.L.D.; Maggiore, P.; Janner, D. Fiber Optic Sensors for Harsh and High Radiation Environments in Aerospace Applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, Z.; Jin, X.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, B. Spatio-Temporal Fusion Attention: A Novel Approach for Remaining Useful Life Prediction Based on Graph Neural Network. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lin, M. Research on robustness of five typical data-driven fault diagnosis models for nuclear power plants. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2022, 165, 108639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.E.; Afgan, I.; Laurence, D.; Revell, A. A dual-mesh hybrid Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes/Large eddy simulation study of the buoyant flow between coaxial cylinders. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2022, 393, 111–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, A.d.S.; Schirru, R. A new methodology for diagnosis system with ‘Don’t Know’ response for Nuclear Power Plant. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2020, 100, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.; Cheema, A.A. A Deep Neural Network-Based Multi-Frequency Path Loss Prediction Model from 0.8 GHz to 70 GHz. Sensors 2021, 21, 5100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimber, N.; Vladimirov, P.; Klimenkov, M.; Jäntsch, U.; Vila, R.; Chakin, V.; Mota, F. Microstructural evolution of three potential fusion candidate steels under ion-irradiation. J. Nucl. Mater. 2020, 535, 152160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. , Daochuan, G., Minghan, Y. A data-driven adaptive fault diagnosis methodology for nuclear power systems based on NSGAII-CNN. Annals of Nuclear Energy. 2021; pp. 108–326.

- Yamakawa, S. Application of Mobile Robots to Linear Control Theory Education: Challenges and Innovations. Journal of Nuclear Engineering and Radiation Science 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucci, L.; Raillon, R.; Taupin, L.; Baqué, F. Design of a Phased Array EMAT for Inspection Applications in Liquid Sodium. Sensors 2019, 19, 4460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, Y.H.; Lee, C.; Han, S.M.; Seong, P.H. Graph neural network based multiple accident diagnosis in nuclear power plants: Data optimization to represent the system configuration. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2022, 54, 2859–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Qian, G. Hierarchical FFT-LSTM-GCN based model for nuclear power plant fault diagnosis considering spatio-temporal features fusion. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2024, 171, 105–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, R.A.; Afzal, A.; Samee, A.M.; Ramis, M. Effect of cladding on thermal behavior of nuclear fuel element with non-uniform heat generation. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2018, 111, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y. Predicting stochastic characteristics of generalized eigenvalues via a novel sensitivity-based probability density evolution method. Appl. Math. Model. 2020, 88, 437–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, S.; Linzi, Z. Robust deep auto-encoding network for real-time anomaly detection at nuclear power plants. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 163, 438–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budanov, P.; Brovko, K.; Cherniuk, A.; Vasyuchenko, P.; Khomenko, V. Improving the reliability of information control systems at power generation facilities based on the fractal cluster theory. Eastern-European J. Enterp. Technol. 2018, 2, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budanov, P.; Brovko, K.; Cherniuk, A.; Pantielieieva, I.; Oliynyk, Y.; Shmatko, N.; Vasyuchenko, P. Improvement of safety of autonomous electrical installations by implementing a method for calculating the electrolytic grounding electrodes parameters. Eastern-European J. Enterp. Technol. 2018, 5, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.; de Mattos, J.; de Andrade, E. Very high burnup fuel for Angra 2 NPP within the 5 w/o limit of the 235U-enrichment. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2019, 346, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Chen, B.; Li, R.; Tian, R. Analysis of fluctuation and breakdown characteristics of liquid film on corrugated plate wall. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2020, 135, 106946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.E.; Afgan, I.; Laurence, D.; Revell, A. A dual-mesh hybrid Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes/Large eddy simulation study of the buoyant flow between coaxial cylinders. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2022, 393, 111789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhitkov, A.; Potapov, A.; Karimov, K.; Kholkina, A.; Shishkin, V.; Dedyukhin, A.; Zaykov, Y. Interaction between UN and CdCl2 in molten LiCl–KCl eutectic. II. Experiment at 1023 K. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2021, 54, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Wang, K.; Su, Q.; Xing, J.; Peng, F. Analysis and experimental investigation on the flow rate controller for PWR accumulator. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2023, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokhforouz, M.; Amiri, H.A. Effects of grain size and shape distribution on pore-scale numerical simulation of two-phase flow in a heterogeneous porous medium. Adv. Water Resour. 2018, 124, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, M.; Bi, Q.; Zhu, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, T. Experimental investigation on heat transfer performance of C-shape tube immerged in a water pool. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2019, 346, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Jerng, D.W.; Bang, I.C. Experimental validation of simulating natural circulation of liquid metal using water. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2020, 52, 1483–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomiak, E. , Burdeina, V., Cherniak, O., Nechuiviter, O., & Bubela, T. (2024). Improving the Method of Quality Control of the FE Shell in Order to Improve the Safety of a Nuclear Reactor. In: Nechyporuk, M., Pavlikov, V., Krytskyi, D. (eds) Integrated Computer Technologies in Mechanical Engineering - 2023. ICTM 2023. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems. 1008. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Khomiak, E. , Trishch, R., Zabolotnyi, O., Cherniak, O., Lutai, L., & Katrich, O. (2024). Automated Mode of Improvement of the Quality Control System for Nuclear Reactor FE Shell Tightness. In: Faure, E., et al. Information Technology for Education, Science, and Technics. ITEST 2024. Lecture Notes on Data Engineering and Communications Technologies. 221. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).