1. Introduction

Underground transmission systems are integral to modern power infrastructure, offering increased reliability and aesthetic benefits over overhead lines [

1]. These systems primarily utilize three types of cables: cross-linked polyethylene (XLPE), self-contained fluid-filled (SCFF), and high-pressure fluid-filled (HPFF) or high-pressure gas-filled (HPGF) cables, each with unique characteristics and applications in power transmission [

2]. The reliability of these systems hinges on effective fault location techniques and minimized outage durations. In the United States, over 80% of the 4,200 circuit miles of underground high-voltage transmission cables are pipe-type cables, a significant portion of which have approached or exceeded their 40-year design life as of 2007 [

3]. The aging infrastructure increases the risk of faults, underscoring the critical need for rapid and accurate fault location methods. A significant majority (69%) of faults occur in cable accessories rather than in the cables themselves, with installation mistakes accounting for 57% of accessory faults. For cable faults, production and installation errors are the primary causes (52%), followed by external damage (17%) and aging (9%) [

4]. In HPFF cables, temperature-driven deterioration in oil impregnated paper insulation is a significant issue. This deterioration approximately doubles in rate with every 6°C increase in temperature and is exacerbated by oxygen and moisture ingress [

5].

Faults in underground cables can take the form of open circuit faults, short circuit faults, or earth faults, each requiring appropriate identification and resolution [

6]. These faults are inevitable and can lead to significant disruptions in power transmission and distribution. Prompt identification and resolution are essential for minimizing revenue losses and reducing customer inconvenience. The fault location process typically involves a two-step approach: prelocation followed by pinpointing. During prelocation, the cable circuit is tested from its terminations to estimate the distance to the fault. Effective prelocation can determine the fault's location within a few percent of the total cable length; however, accuracy may be reduced in very long cables. Some widely used prelocation techniques include time domain reflectometry (TDR), burn down, and arc reflection [

7,

8,

9]. The choice of prelocation technique often depends on the fault type and cable characteristics, as no single method is universally optimal.

Pinpointing the exact fault location of underground cables can be accomplished through various techniques. A voltage gradient method involves applying a pulsed direct current (DC) voltage to the faulted cable, creating a voltage gradient in the surrounding soil. This voltage gradient can be measured with earth probes to locate the fault, particularly effective for direct-buried cables but less accurate in highly resistive soils or ducts [

10,

11]. A magnetic gradient method detects the magnetic field from an alternating current (AC) voltage injected into the cable, useful for submarine cables but less effective in complex urban environments [

12]. An acoustic method is the conventional approach for fault pinpointing and involves using "capacitive discharge" techniques [

13]. This acoustic method involves discharging an electrical impulse onto the cable with a high-voltage test set, causing it to break down at the fault’s location. The sound of the breakdown pulse is then picked up acoustically. This is commonly referred to as ‘thumping’. The pinpointing method is accomplished by operators using specialized surface microphones (geophones) and walking along the cable route. While this pinpointing method is very effective, it is burdened by an extremely slow response time due to setup, methodical search along the cable route, and interference or noise effects in the subsurface environment. Additionally, repeated thumping may cause further damage to the cable [

14]. Locating faults in ducted cable systems can also be challenging. Poor acoustic contact may prevent the fault from generating a detectable signal at the surface, with the acoustic signal traveling along the duct and the strongest signal often detected at nearby manholes rather than directly at the fault site [

15].

In recent years, newer fault location methods for underground cables, such as distributed temperature sensing and distributed vibration sensing, have shown promise in fault location [

12]. These fault location methods utilize fiber-optic cables embedded alongside power cables to detect variations in temperature and vibration caused by faults. While these fault location methods offer real-time monitoring and high precision, they require pre-installed fiber optics, which are not always available in legacy systems. Another growing trend is the integration of IoT-based systems, which combine technologies such as LTE, GPS, and GSM, along with electric field energy harvesters as power sources, to enable real-time fault detection and location [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. These IoT-based fault location methods enable remote monitoring but are typically part of online systems that must be installed before a fault occurs, making them less practical for older circuits lacking such infrastructure. The limitations of current fault pinpointing methods, particularly for aging pipe-type cable systems in complex environments, highlight a critical gap in the field. While recent advancements focus on real-time, pre-installed systems, there is a pressing need for innovative offline solutions applicable to existing infrastructure. Current techniques, though offering certain advantages, fail to fully address the unique challenges posed by urban infrastructure and ducted systems. An ideal solution would leverage advanced sensors and technology for rapid, accurate, and non-damaging fault location, while building upon the strengths of acoustic detection methods.

To address these challenges, this study proposes a novel enhancement to conventional acoustic thumping for pipe-type cable systems. Rather than relying on the traditional method of walking the entire cable route with a geophone, the proposed pinpointing approach for pipe-type cable systems involves accessing nearby manholes and attaching acoustic sensors directly to the steel pipe after fault prelocation estimation. This innovative method, inspired by the concept of acoustic leak location as detailed in previous research [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28], aims to offer a more efficient and accurate means of fault pinpointing. Hydrophones, geophones, and accelerometers were evaluated as candidate sensors for steel-borne acoustic pinpointing [

29,

30,

31]. Among these, an accelerometer-based instrumentation package was identified as offering the best pinpointing accuracy, particularly for detecting acoustic pulses in steel pipes with low damping and a high signal-to-noise ratio [

32]. Various signal processing techniques, such as Fast Fourier Transforms (FFT), Wavelet Transforms (WT), cross-correlation, and empirical mode decomposition (EMD), have been successfully applied to acoustic wave propagation in pipes [

33,

34,

35]. While these methods can enhance data interpretation, this study focuses on validating direct accelerometer measurements for fault location. Future work may explore the integration of advanced signal processing techniques to further refine pinpointing accuracy. By utilizing accelerometers in this enhanced setup, the proposed method aims to detect high-frequency steel-borne acoustic pulses with greater sensitivity and provide immediate and significantly improved fault pinpointing accuracy with just a single thump. Additionally, this approach minimizes the potential damage caused by repeated thumping inherent in conventional methods, which often involve manual searching with a geophone.

The main objective of this study is to validate the proposed concept of steel-borne acoustic fault pinpointing by replicating the thumping mechanism in the lab and carrying out an experimental study on a scaled-down HPFF test rig. The study will focus on determining the acoustic pulse propagation characteristics, evaluating pinpointing accuracy, and assessing how surrounding backfill material affects signal attenuation. The results will demonstrate the feasibility of this enhanced method in improving fault pinpointing for HPFF pipe-type cables. The successful implementation of this advanced acoustic pinpointing method could significantly improve the reliability and resilience of underground power distribution networks, potentially reducing downtime, minimizing repair costs, and enhancing overall grid stability across urban and suburban areas.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: in

Section 2, the test setup, instrumentation and testing methodologies are outlined. In

Section 3, the results of all test cases are presented, while

Section 4 discusses the results. Finally, the conclusions are summarized in

Section 5. The rest of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 details the experimental setup, including the scaled-down HPFF test pipe, instrumentation, and testing methodologies for acoustic pulse generation and detection.

Section 3 presents the results, covering acoustic pulse velocity measurements, fault localization accuracy, and attenuation studies under various pipe embedment conditions.

Section 4 discusses the implications of the results, primarily discussing the potential of this technology for fault pinpointing and describing the benefits over traditional method. comparing the findings to conventional acoustic fault pinpointing methods.

Section 5 summarizes the conclusions drawn from this study. Finally,

Section 6 suggests directions for future work.

2. Experimental Setup: Materials and Methods

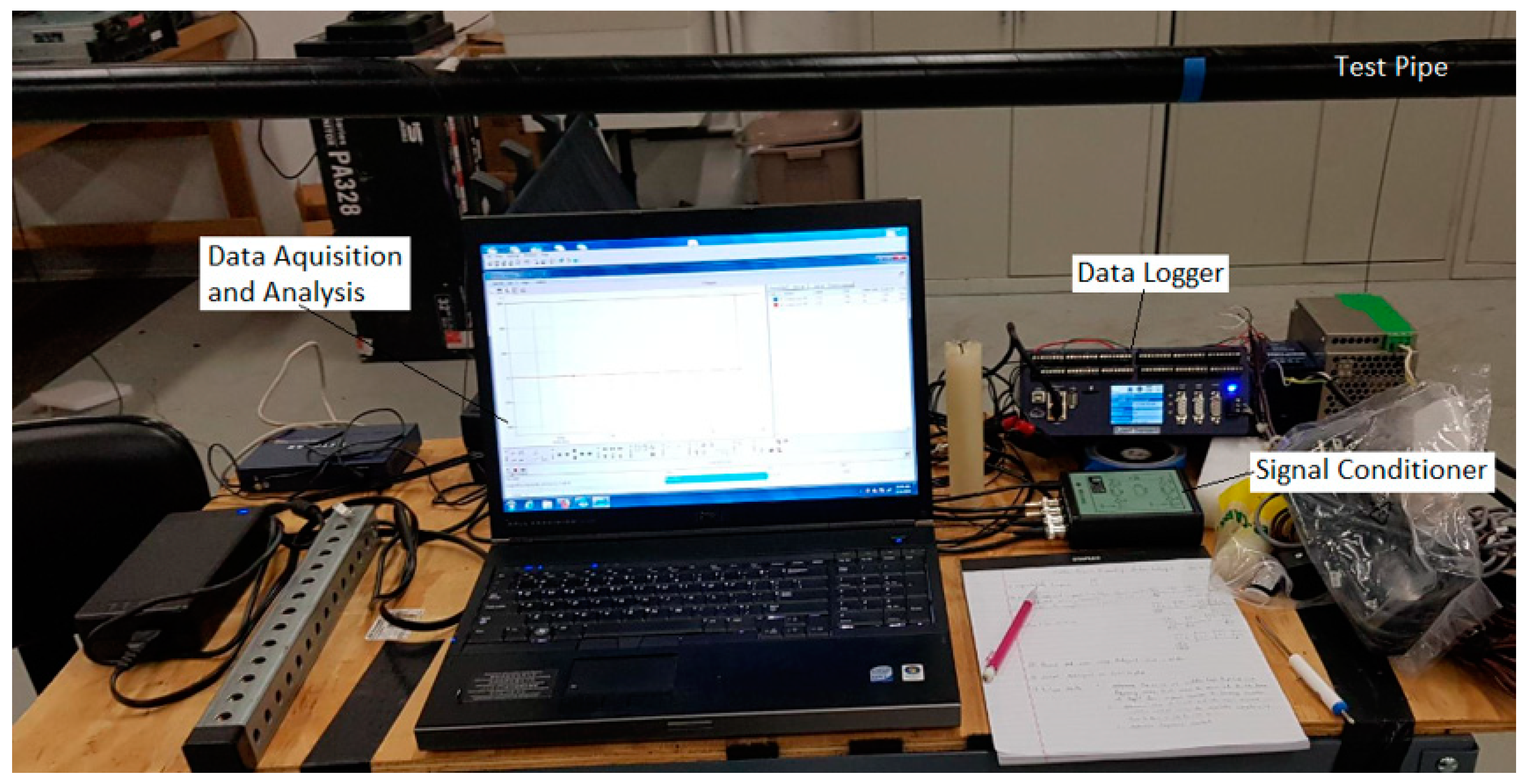

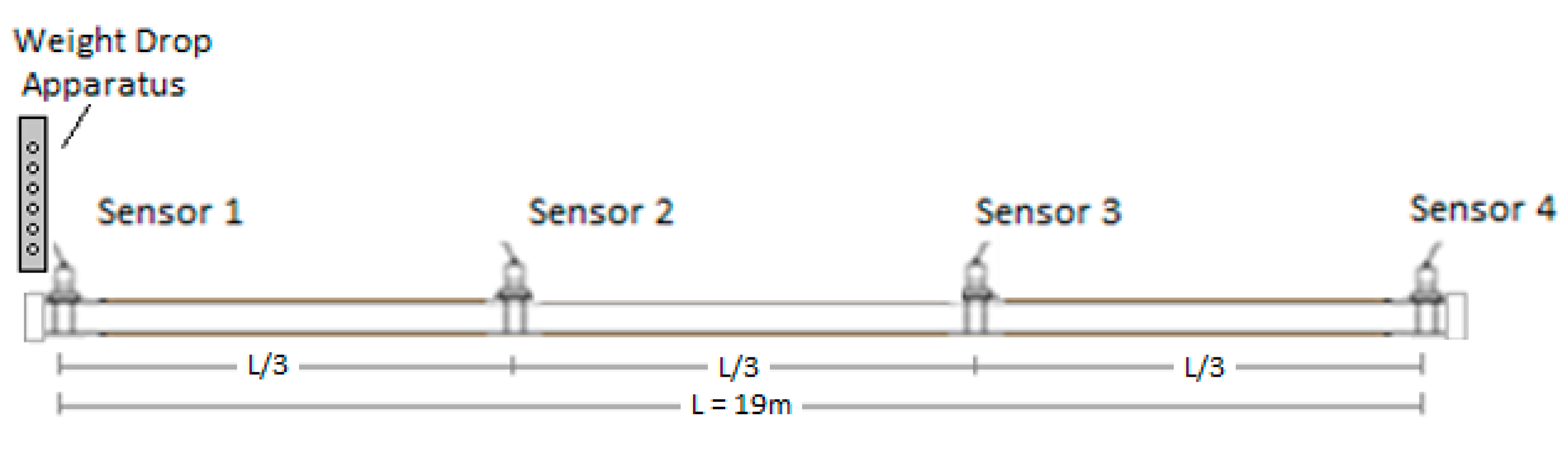

Acoustic pinpointing feasibility testing was conducted on an experimental test pipe consisting of a 19-m (49.25 mm ID) Schedule-80 carbon steel pipe, the same material used in HPFF pipes. The pipe was coated externally with Pritec (HDPE over butyl mastic), the same as that used in HPFF pipes. The pipe's dimensions and material properties are summarized in

Table 1. The measurement system included four B&K accelerometers, two B&K two-channel signal conditioners, and one Delphin Expert Transient Data Logger, with specifications provided in

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4.

Figure 1 depicts the test pipe and the components of the measurement system.

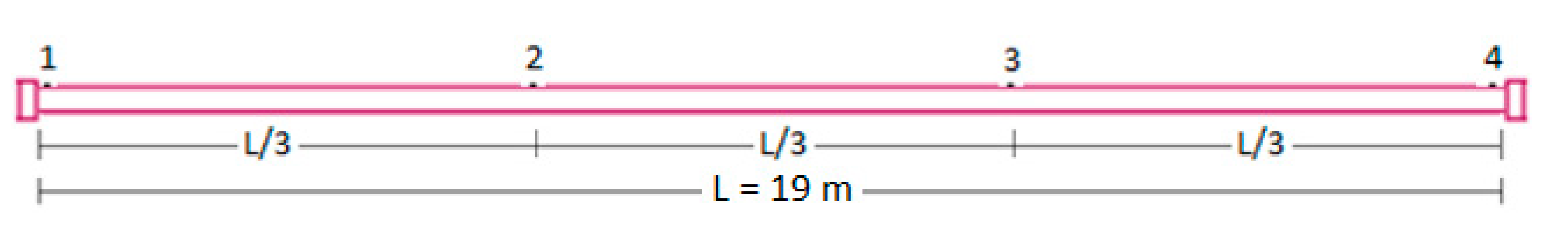

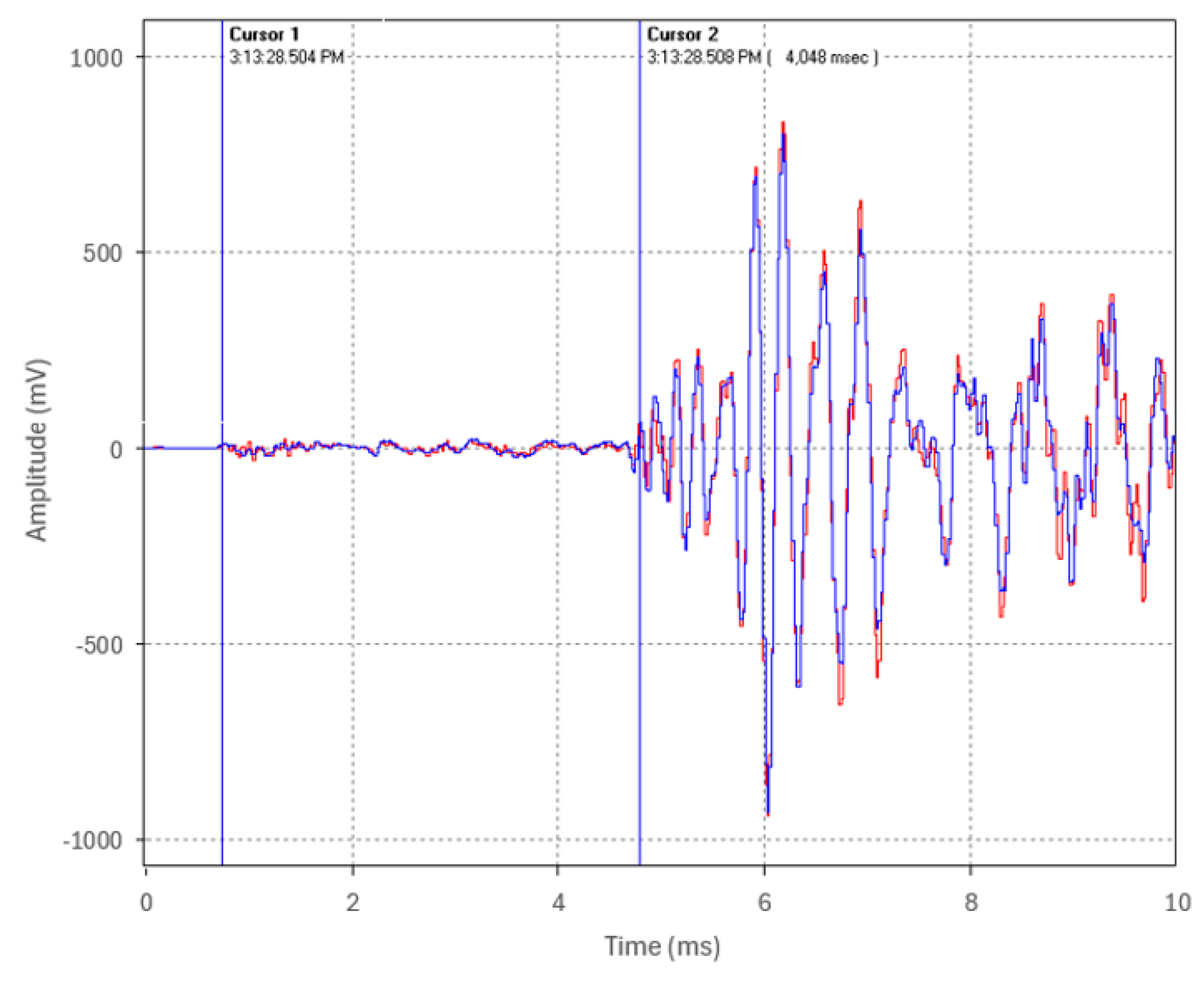

The accelerometers were individually calibrated by the manufacturer using state-of-the-art random FFT technology, providing an 800-point high-resolution calibration (magnitude and phase). Prior to testing, the accuracy of the sensors' calibration and time synchronization was verified by attaching them at the pipe's end and impacting the test pipe at the opposite end, as illustrated in

Figure 2 by Locations 1 and 4. The resulting waveforms recorded by sensors show a high degree of calibration and time synchronization across the entire sensor array, as shown in

Figure 3. The sensors were strategically attached to the steel pipe using beeswax, positioned at both ends and at one-third intervals along its length. These positions, designated as Locations 1, 2, 3, and 4, are shown in

Figure 2. This configuration enabled comprehensive data collection along the entire pipe length.

Two methods were employed for acoustic pulse generation in the test pipe for this study. The first method utilized a weight drop apparatus where a 0.91-kg (2-lb) weight was released from a fixed height of 63.5 mm (2.5 in) onto the pipe’s surface. This method ensured consistent and repeatable acoustic pulse generation, enabling standardized measurements across multiple tests and runs.

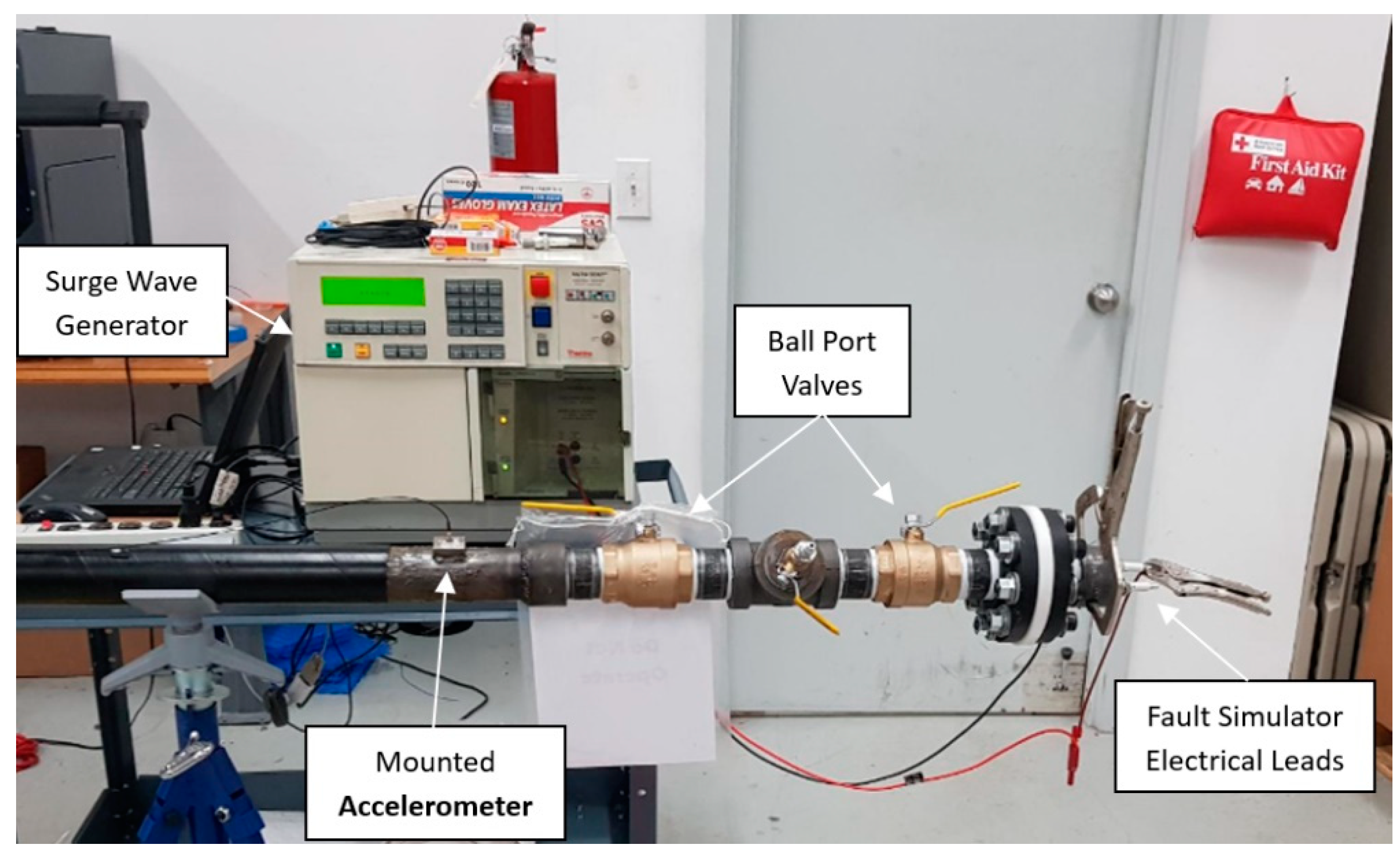

The second method employed a fault simulator device designed to more closely mimic the real-world fault thumping mechanism. This custom-built device comprised of a non-resistor spark plug, retrofitted into the dielectric fluid filled as will be detailed in

Section 2.2. The terminals of the fault simulator device connect to a surge wave generator or a full-scale thumper, enabling powerful capacitive discharges at the spark gap. The specifications of the full-scale thumper are detailed in

Table 4.

Table 4.

Specifications of the Megger 32 kV Thumper.

Table 4.

Specifications of the Megger 32 kV Thumper.

| Item |

|

Value |

| Product model |

|

Megger SPG 32 |

Voltage

Energy

Surge Rate

Burning |

|

0 – 32 kV

1750 Joules

3 – 10 s; single pulse

0 – 32 kV; 160 mA |

2.1. Test Series 1

2.1.1. Test 1.1: Determining and Verifying Acoustic Pulse Velocity in Steel Pipe

To accurately pinpoint the source of an acoustic pulse along the length of the pipe, it is essential to determine the acoustic pulse velocity in the steel pipe experimentally and verify against the theoretical value. In Test 1.1, an acoustic pulse was generated at Location 1 using the weight drop apparatus. The time of flight across the 19-meter test pipe was measured by cross-correlating the pulse's arrival time at Location 4 with its initiation time at Location 1. The experimental velocity of the acoustic pulse was then calculated using the distance and measured time, while the theoretical velocity of the acoustic pulse can be determined by

where

E is the Young's modulus of the material and

ρ is the density of the material.

2.1.2. Test 1.2: Localization Accuracy and Pinpointing of Acoustic Pulse Source

With the propagation velocity established, Test 1.2 aimed to investigate the fault pinpointing concept and evaluate localization accuracy by generating an acoustic pulse at one-third of the pipe length (Location 2). The acoustic pulse source is pinpointed by using the Time Difference of Arrival (TDOA) method, which can be represented as

where

d is the total length of pipe (

d=19m) and ∆

t is the TDOA.

2.2. Fault Simulator Device Evaluation for Acoustic Pulse Generation

For the proposed technology to be viable for HPFF fault pinpointing, thumping of the cable system must vaporize the dielectric fluid surrounding the fault. The sudden vaporization of the dielectric fluid creates a shock wave, which is believed to induce an acoustic pulse that propagates inside the pipe’s wall in both directions. To investigate this concept, the test pipe was equipped with necessary hydraulic components and filled with dielectric fluid type DF 100, a fluid very commonly used in HPFF cable systems. The fault simulator device was then installed in the test pipe and connected to the Surge Wave Generator, as shown in

Figure 5. Test 2 was conducted to validate the concept that creating a fault generates an acoustic pulse in the steel wall. This test involved producing a capacitive discharge (spark) in the dielectric fluid at Location 1. The goal was to generate a steel-borne acoustic pulse that could be detected by Sensor 4 at the remote end of the pipe. This test laid the groundwork for more comprehensive future testing.

2.3. Test Series 3: Acoustic Pulse Attenuation Study

In actual HPFF pipe-type cable installations, the steel pipe is mechanically coupled to the surrounding soil, resulting in increased signal attenuation due to the leakage of acoustic energy into the soil. To explore this complex interaction, Test 3 was conducted as a series of subtests (Tests 3.1–3.3), designed to investigate the effects of varying embedding conditions on the propagation and attenuation of steel-borne acoustic pulses. The tests included conditions where the pipe was: fully supported in air (Test 3.1), laid on tamped rock dust (Test 3.2), and finally fully embedded in tamped rock dust (Test 3.3). Rock dust, selected for its excellent thermal properties and common use in engineered backfill, served as the backfill material. Its grain composition, which ranges from coarse to fine, allows for high compaction and thermal conductivity, providing a controlled medium to analyze acoustic energy absorption and signal attenuation.

In each subtest (Tests 3.1–3.3), a consistent acoustic pulse was generated using the weight drop apparatus, with a 0.91 kg (2 lb.) weight dropped from a constant height of 63.5 mm (2.5 in) at the pipe end (Location 1). The four accelerometers were evenly spaced along the 19-meter pipe at one-third intervals (6.33 meters apart). To ensure reliability and repeatability, five identical runs were recorded for each subtest. A 3 kHz low-pass filter (LPF) was applied to the data to remove high-frequency noise and enhance the clarity of the acoustic pulse signals. This filter was used because it was observed in previous tests that the acoustic pulse frequency components resided within this range. The filtered data was then collected and analyzed to assess the impact of different embedding conditions on signal attenuation.

The attenuation constant between sensors was calculated using Equation (3), where

A0 is the reference amplitude and

A1 is the amplitude of the acoustic pulse after traveling a distance

L.

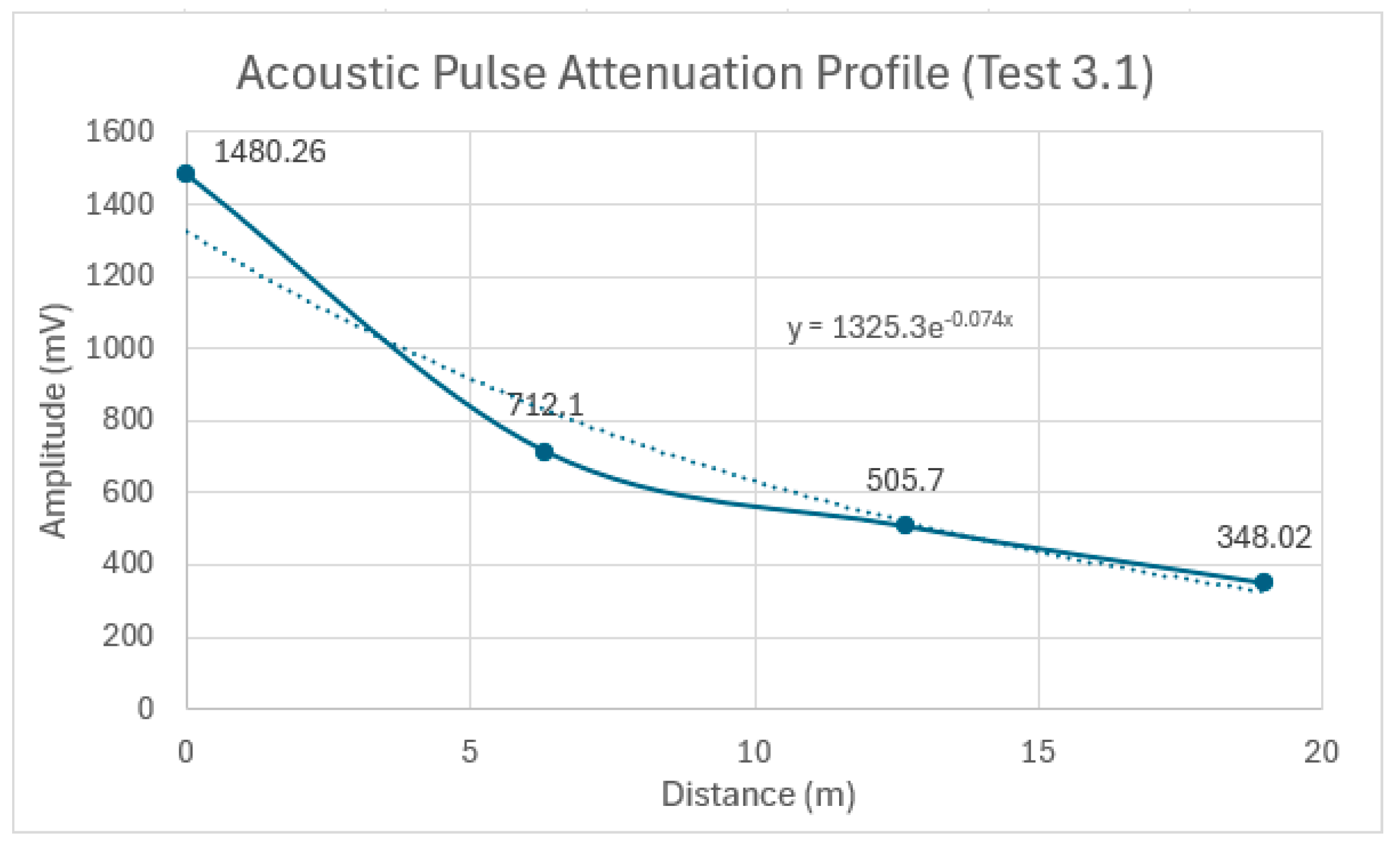

2.3.1. Test 3.1: Pipe Supported in Air – Attenuation of Pipe in Air

In Test 3.1, the test pipe was supported in air using four V-head pipe stands, identical to the setup in Test Series 1 and 2. This test aimed to assess the attenuation of the acoustic pulse due solely to the pipe's properties, serving as a baseline reference for evaluating additional damping effects observed in Tests 3.2 and 3.3.

Figure 6 depicts the setup for Test 3.1, showing the pipe supported in air along with the location of the weight drop apparatus.

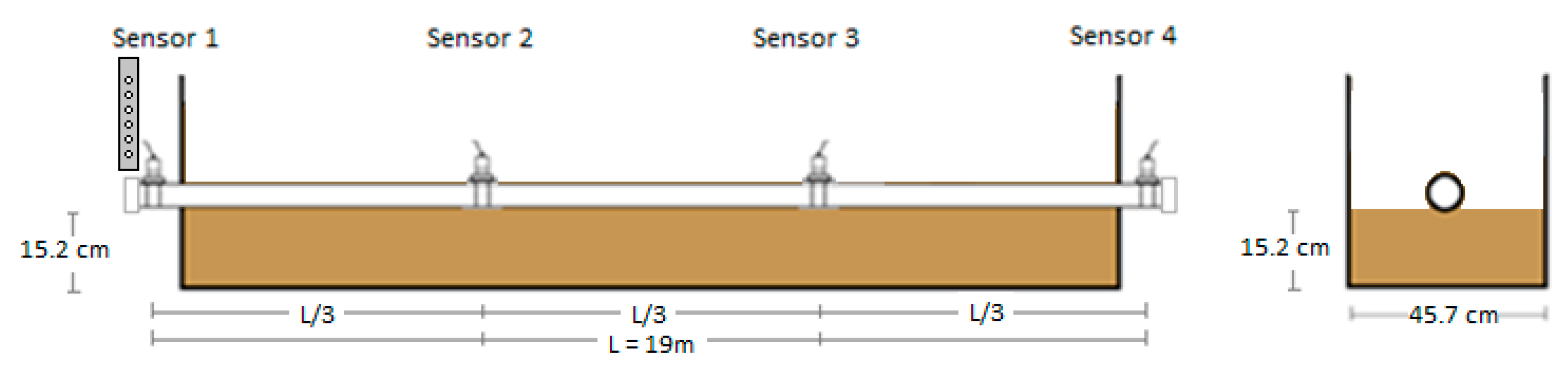

2.3.2. Test 3.2: Pipe Laid on Tamped Backfill – Attenuation due to Contact with Backfill

For Test 3.2, a containment box measuring 17 m in length, 46 cm in width, and 61 cm in height was constructed from plywood and lined with a vinyl sheet to prevent moisture ingress. Aluminum foil was placed at the bottom of the box to provide grounding for future thumping tests. The pipe was placed on top of the 15 cm thick layer of tamped rock dust, which was added and tamped in 5–8 cm lifts. The overall test layout with the dimensions of the tamped rock dust is shown in

Figure 7. The tamping and layering process are depicted in

Figure 8a,b, and the final set up is shown in

Figure 8c. As in Test 3.1, controlled weight drops were performed using the weight drop apparatus from the same height, maintaining all parameters consistent except for the pipe now being supported on the tamped rock dust.

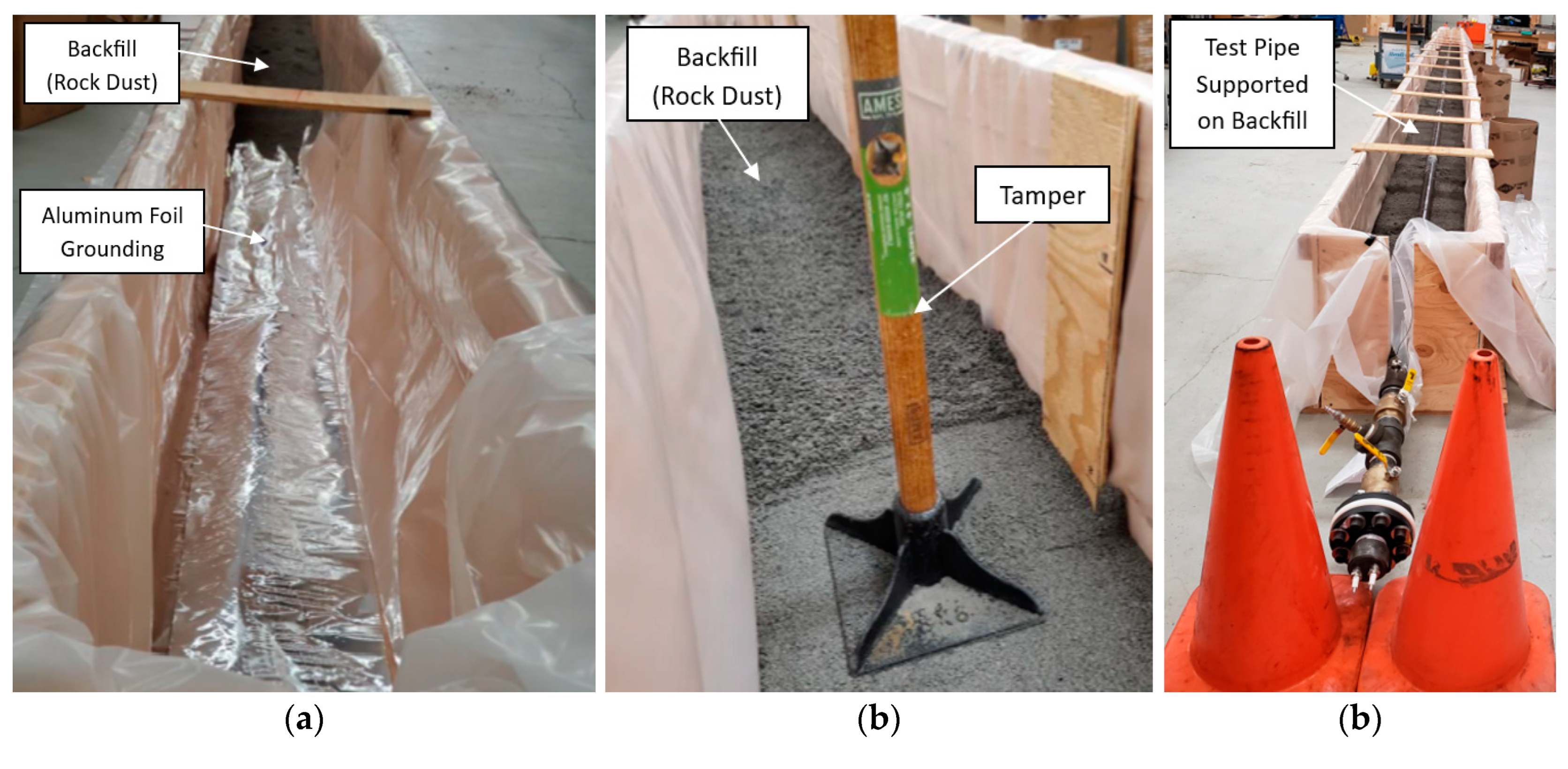

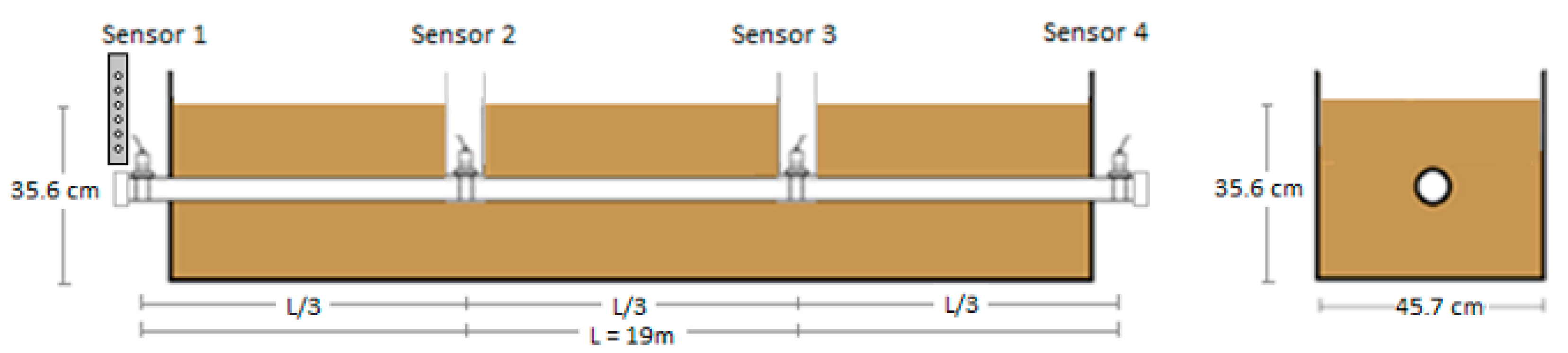

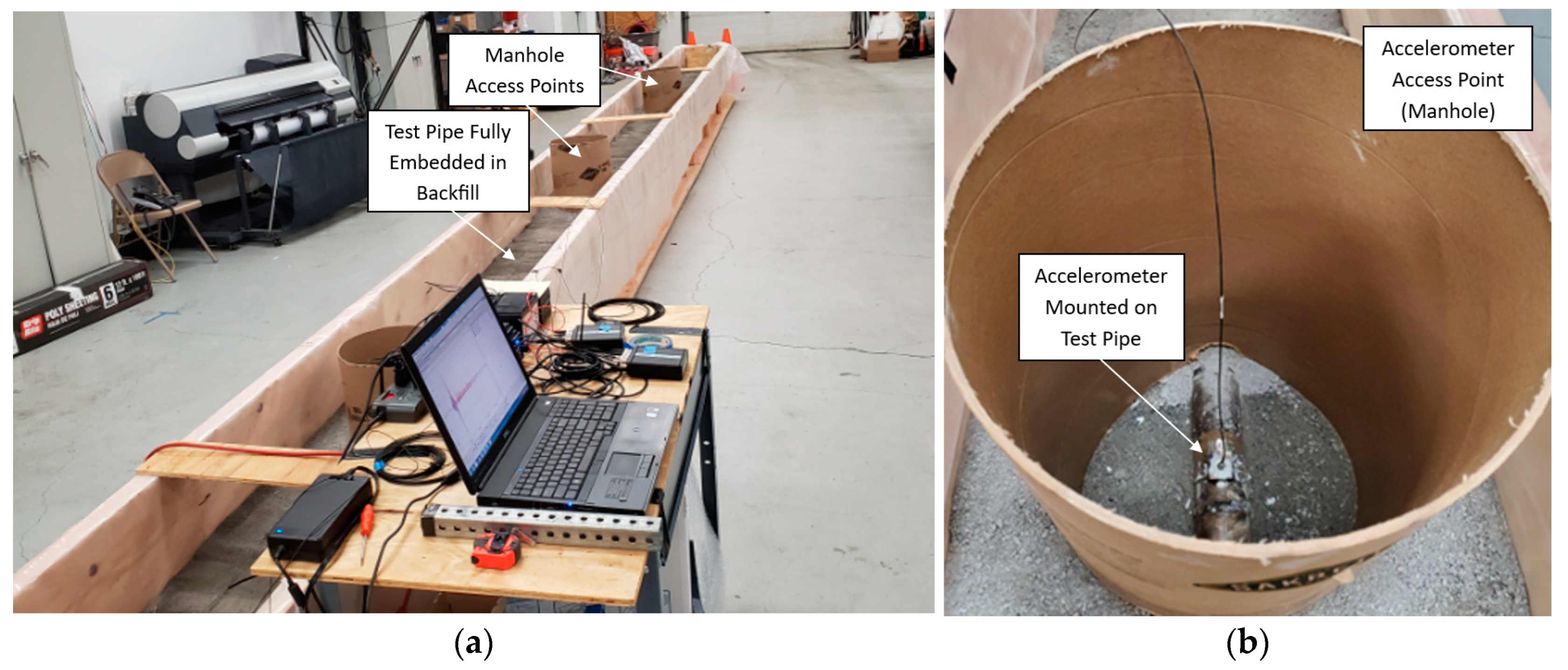

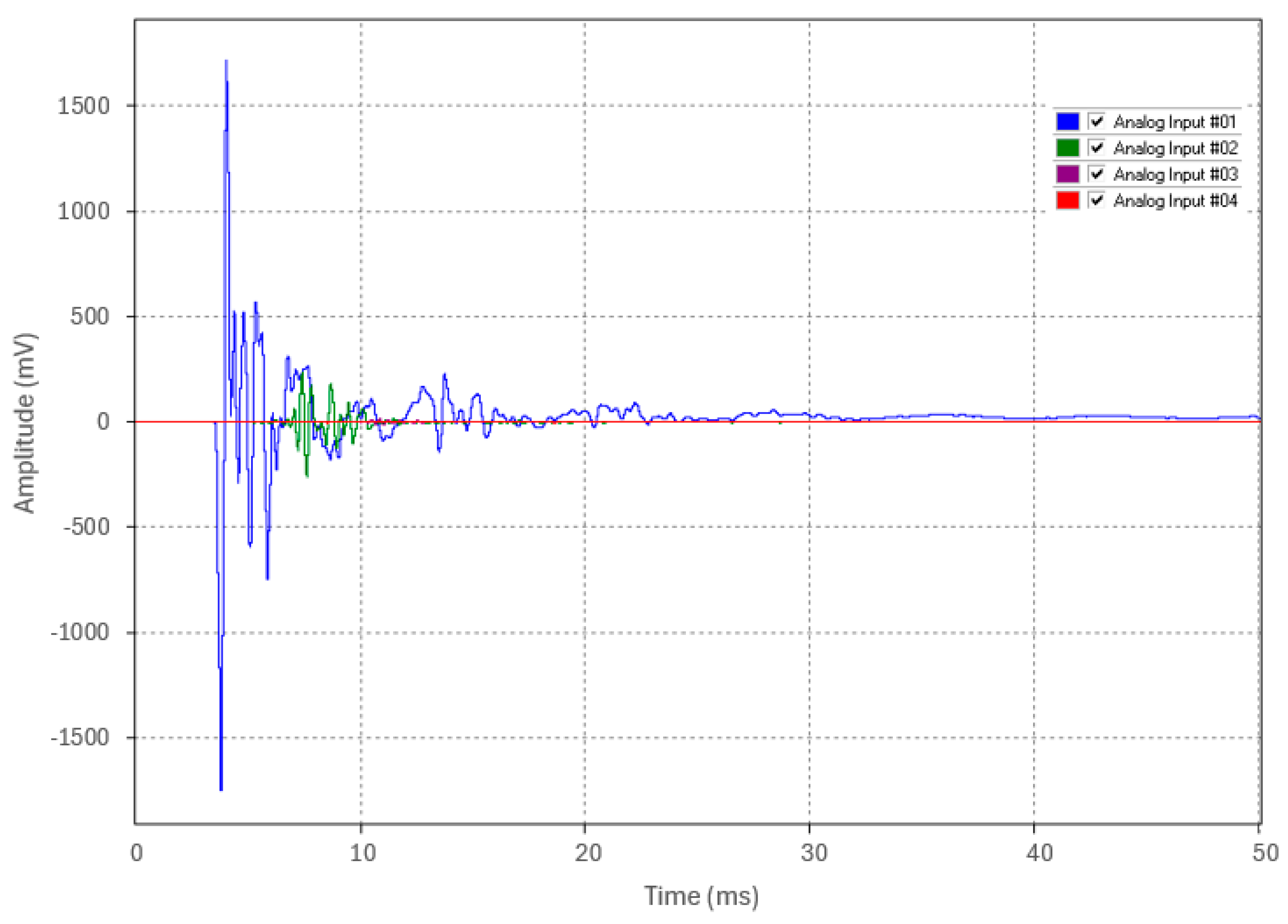

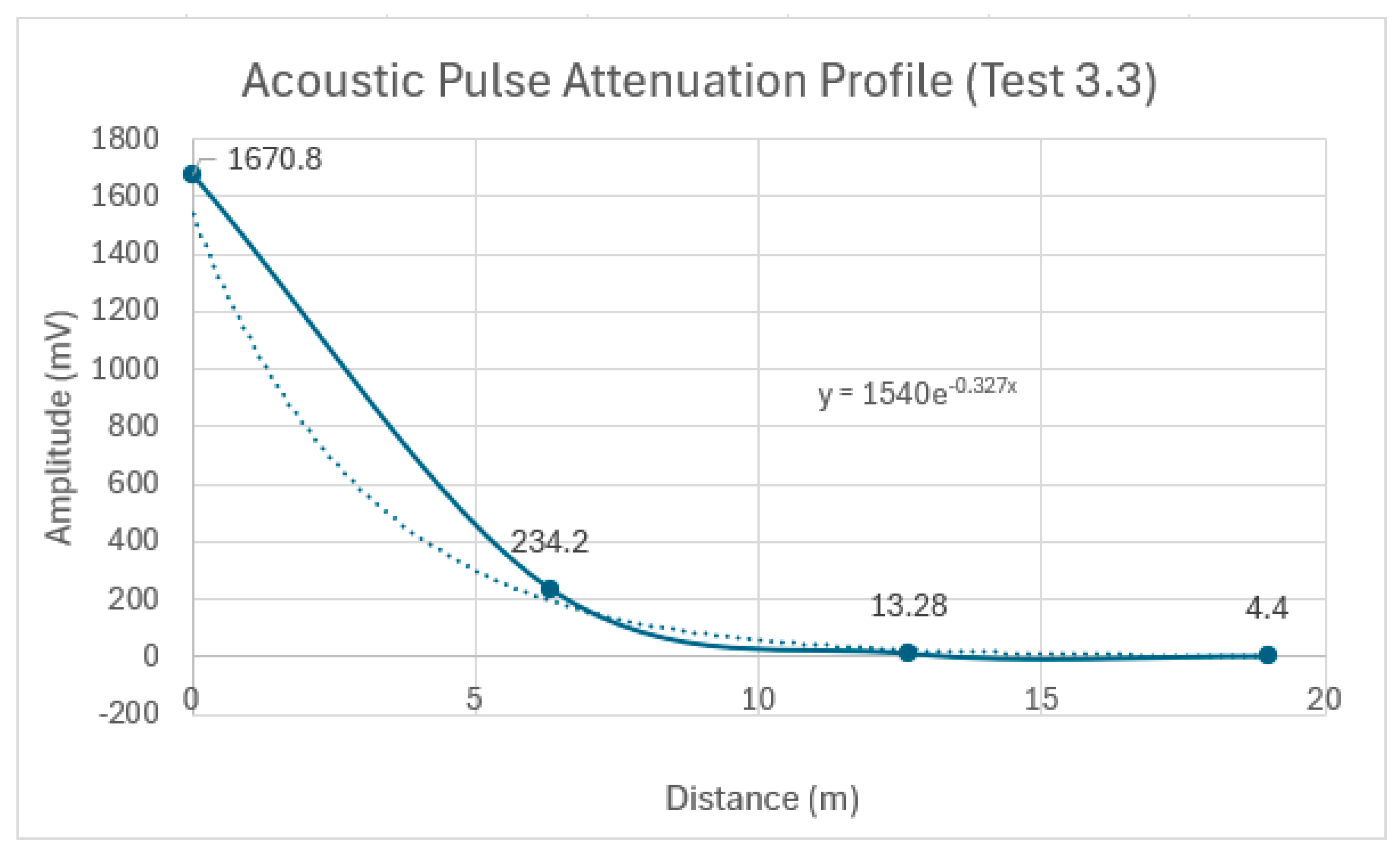

2.3.3. Test 3.3: Attenuation in Fully Embedded Pipe

In Test 3.3, additional layers of rock dust were added and tamped until the pipe was fully embedded in the center of the containment box, as shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10a. Access point to the intermediate sensors via a 'manhole' is shown in

Figure 10b. The fully surrounding backfill material (rock dust) provided an absorbing medium for acoustic energy, similar to real pipe-type cable systems. Controlled weight drops were performed using the weight drop apparatus, with all parameters consistent with Tests 3.1 and 3.2, except that the pipe was now fully embedded in backfill.

2.4. Test 4 - Fault Simulator Thumping Test on Fully Embedded Test Pipe

Test 4 evaluated the acoustic pinpointing method in the fully embedded, dielectric fluid-filled test pipe configuration of Test 3.3. The fault simulator was positioned at one-third of the pipe's length (Location 2). A full-scale commercial thumper applied a 16 kV voltage charge to the spark plug, simulating a cable fault at an intermediate location. Figure 11 depicts the complete test setup, which represents a comprehensive, scaled-down model of a real HPFF system. The objective of this experiment was to assess the effectiveness of acoustic pinpointing under conditions that closely mimic those of an actual HPFF system within a controlled laboratory environment.

2.5. Summary of Experimental Tests

Table 6 provides a summary of all the tests conducted in this study, highlighting the objectives, acoustic pulse generation methods, and corresponding embedment conditions for each test case.

4. Discussion

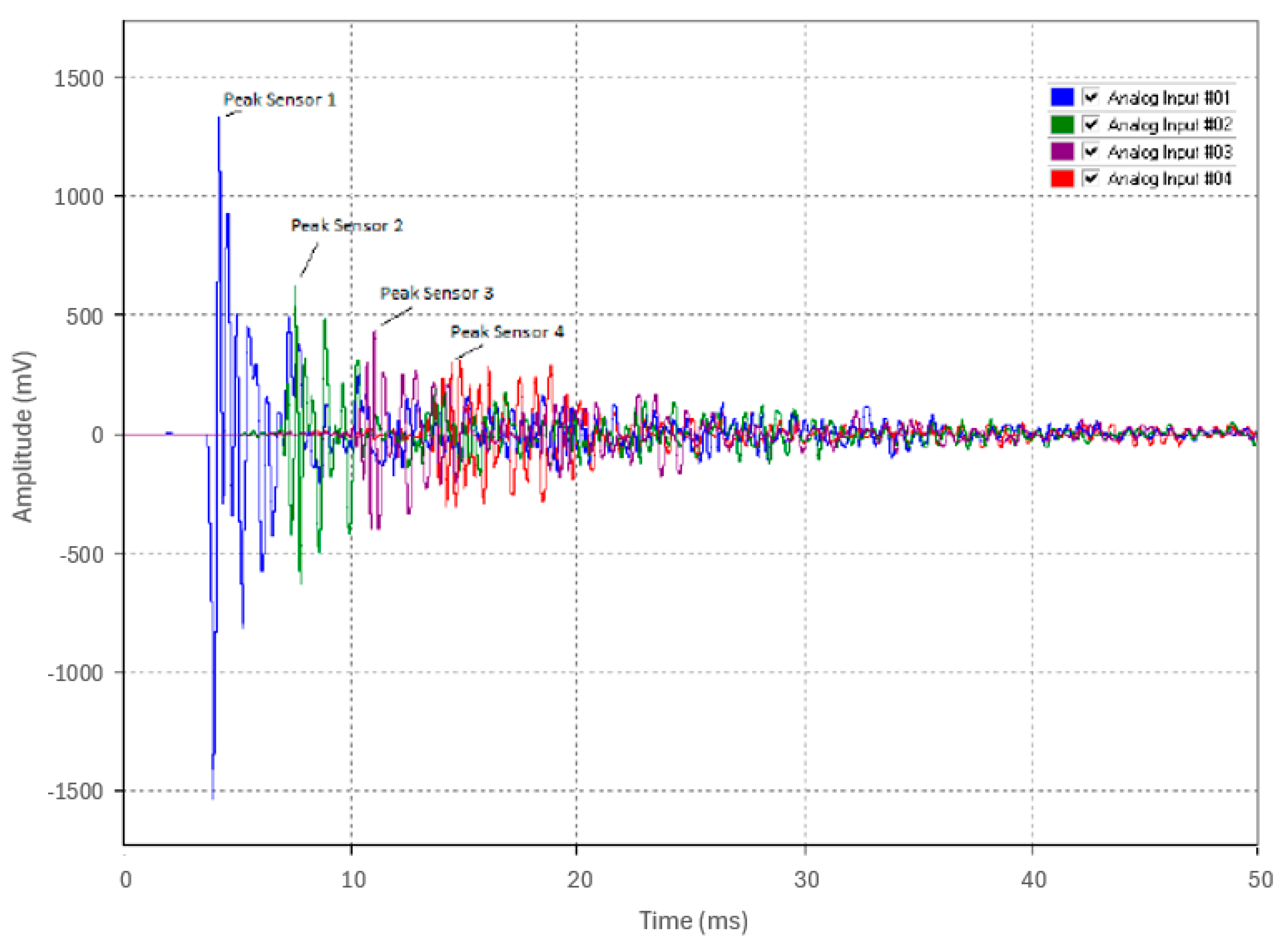

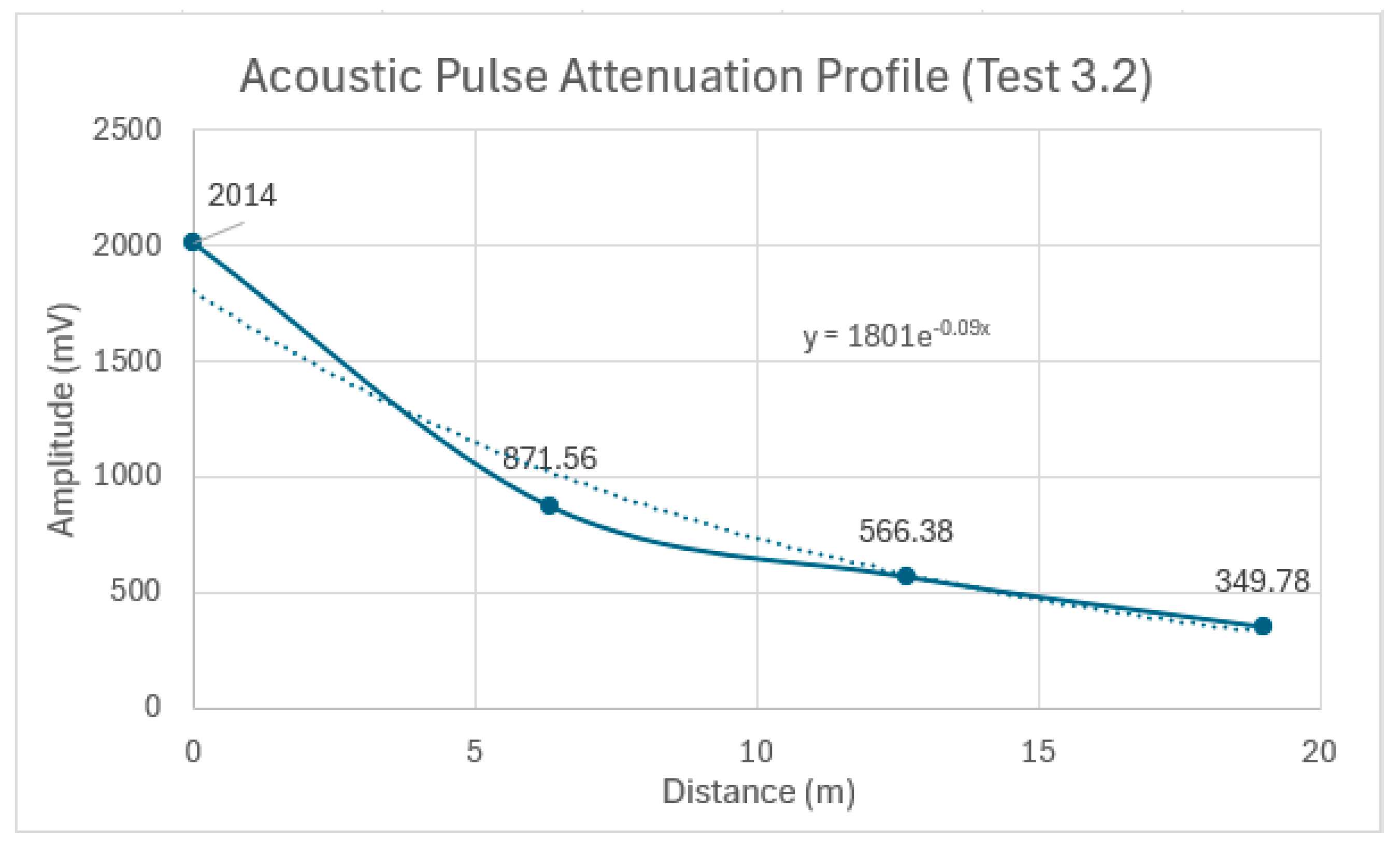

The studies presented in this paper offer significant insights into the feasibility and accuracy of a novel acoustic fault pinpointing technique within a scaled-down model of an HPFF pipe-type cable system. Employing a 19-meter test pipe, our experiments demonstrated high accuracy in both measuring acoustic pulse velocity and localizing faults under controlled conditions. The measured velocity, ranging from 5,000 to 5,066.67 m/s, closely aligned with the theoretical value of 5,047.7 m/s, validating the measurement methodology used in this study. Additionally, fault simulation tests conducted on the fully embedded configuration confirmed the potential applicability of this technique. Using a commercial thumper, we successfully detected and accurately localized a simulated fault to within 2.5 cm over the 19 m pipe, demonstrating potential for fault pinpointing in full-scale systems. The effect of pipe embedment on acoustic pulse attenuation was clearly demonstrated in Test Series 3. Attenuation progressively increased as we moved from the pipe suspended in air to partially and fully embedded conditions. Specifically, an attenuation coefficient of 0.074 Np/m was measured between Sensors 1 and 4 in the air-supported setup. This value increased to 38.2% when the pipe was laid on tamped backfill, and further to 66.9% when the pipe was fully embedded. These results highlight the significant role that surrounding material plays in acoustic energy dissipation.

Our analysis also revealed a frequency spectrum within 3 kHz in the experimental setup. We expect that in real-world HPFF cable systems, the frequency of the acoustic pulse generated during thumping would be lower. This expectation arises from the increased arcing power and the larger cross-sectional area occupied by the dielectric fluid in the pipe, which may transmit a broader range of frequencies to the steel pipe wall. A lower frequency pulse is likely to experience reduced attenuation, enabling fault pinpointing over longer distances. However, there may be a slight trade-off in pinpointing accuracy, yet this reduction is not expected to hinder effective localization.

The promising results presented here provide an encouraging step toward understanding these phenomena, but further empirical validation is required to confirm these assumptions in full-scale systems. Additional studies are needed to explore the detection range, accuracy, and reliability of this method under diverse environmental and operational factors present in actual install.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the feasibility and accuracy of acoustic fault pinpointing in a scaled-down model of HPFF pipe-type cable systems. The measured velocity of the acoustic pulses closely matched the theoretical values. In addition, the ability to detect and localize a fault to within 0.16% of the pipe’s total length using a commercial thumper suggests that the method has practical applications. While these findings are promising, they represent an initial step. Further confirmation using a full-scale HPFF system is essential to assess the method's performance under real-world conditions. Specifically, validation of the detection range, accuracy, and reliability will be critical in determining the technique’s practical utility. The observed effect of pipe embedment on acoustic attenuation is another crucial finding. As demonstrated, attenuation increased as the pipe transitioned from being suspended in air to fully embedded. This underscores the importance of understanding how surrounding materials affect acoustic signal propagation and energy dissipation in real-world scenarios. In full-scale HPFF cable system acoustic pinpointing, we anticipate that lower frequency pulses generated during thumping could result in reduced attenuation, thereby facilitating fault pinpointing over longer distances.

In conclusion, the successful implementation of this enhanced acoustic pinpointing method could significantly improve the reliability and resilience of underground power distribution networks. By addressing the limitations of traditional acoustic pinpointing techniques, which often suffer from slow response times due to extensive setup and methodical searches, as well as issues with noise interference and potential cable damage from repeated thumping, the proposed method offers a potentially faster and more accurate solution for fault localization. Additionally, the proposed approach overcomes challenges faced in ducted systems, where poor acoustic contact can lead to detection at manholes rather than at the fault site. The use of advanced sensors in our scaled-down model demonstrates promising results that could reduce downtime, minimize repair costs, and enhance overall grid stability in urban and suburban areas. The findings provide a solid foundation for full-scale testing and offer insights into acoustic pulse behavior and attenuation patterns that can guide future research and deployment strategies.

Figure 1.

Test pipe and measurement system components.

Figure 1.

Test pipe and measurement system components.

Figure 2.

Sensor placements on test pipe (Locations 1, 2, 3 and 4).

Figure 2.

Sensor placements on test pipe (Locations 1, 2, 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Calibration and time synchronization of the accelerometers.

Figure 3.

Calibration and time synchronization of the accelerometers.

Figure 5.

Fault simulator device connected to surge wave generator.

Figure 5.

Fault simulator device connected to surge wave generator.

Figure 6.

Pipe supported in air - Test 3.1 configuration.

Figure 6.

Pipe supported in air - Test 3.1 configuration.

Figure 7.

Test 3.2 Configuration (pipe laid on tamped rock dust) – Impact at Sensor 1 Location.

Figure 7.

Test 3.2 Configuration (pipe laid on tamped rock dust) – Impact at Sensor 1 Location.

Figure 8.

Tamping and layering process: (a) Rock dust being poured into the containment box; (b) Rock dust tamped in 5–8 cm lifts; (c) Final setup of the pipe laid on 15 cm of tamped rock dust in Test 3.2.

Figure 8.

Tamping and layering process: (a) Rock dust being poured into the containment box; (b) Rock dust tamped in 5–8 cm lifts; (c) Final setup of the pipe laid on 15 cm of tamped rock dust in Test 3.2.

Figure 9.

Test 3.3 Configuration (Fully Embedded) – Impact at Sensor 1 location.

Figure 9.

Test 3.3 Configuration (Fully Embedded) – Impact at Sensor 1 location.

Figure 10.

Test 3.3 - Fully embedded configuration: (a) Complete experimental setup; (b) Manhole access points at intermediate locations for accelerometer placement.

Figure 10.

Test 3.3 - Fully embedded configuration: (a) Complete experimental setup; (b) Manhole access points at intermediate locations for accelerometer placement.

Figure 12.

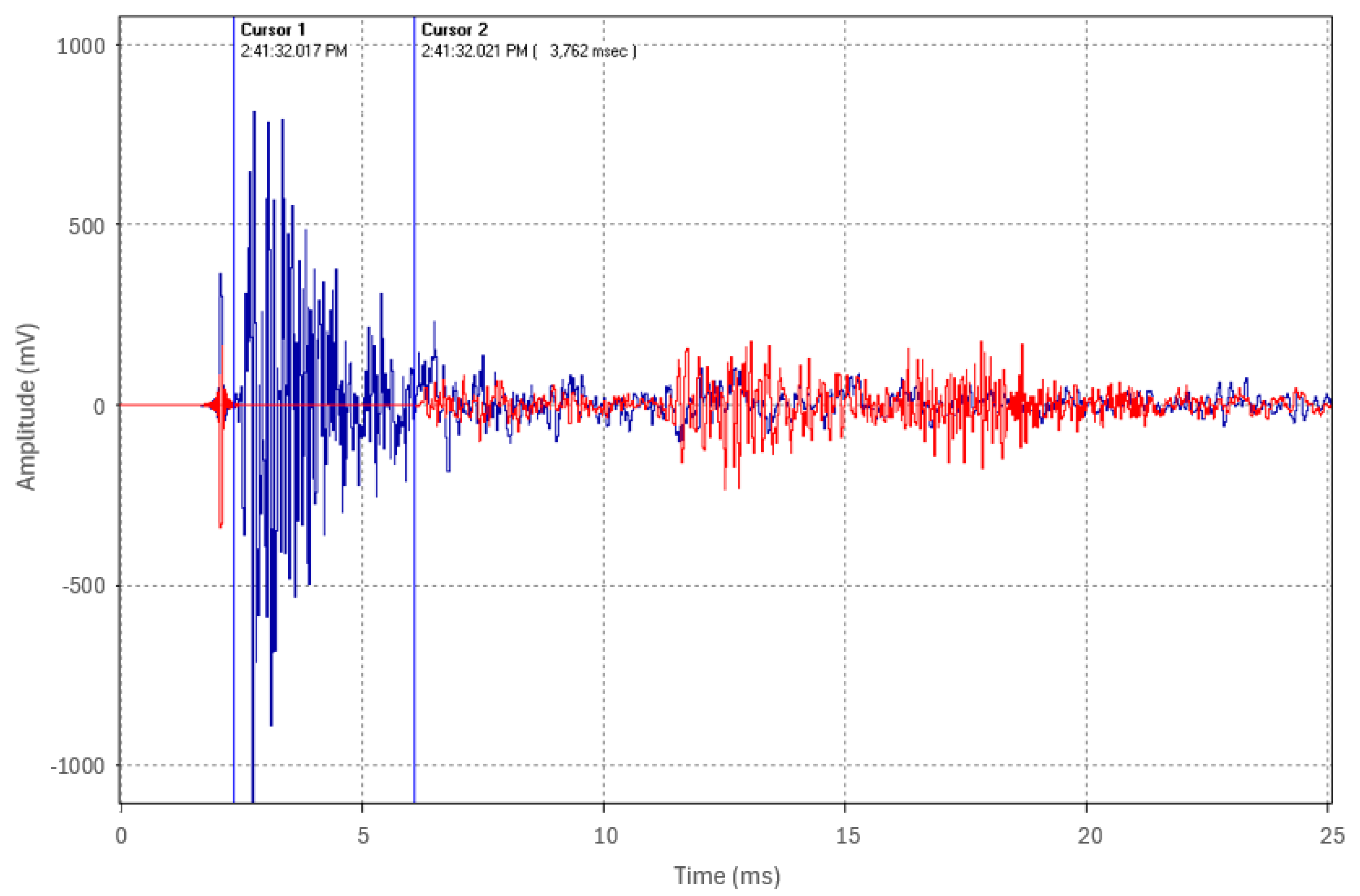

Acoustic waveforms captured by Sensors 1 and 4 (Test 1.1).

Figure 12.

Acoustic waveforms captured by Sensors 1 and 4 (Test 1.1).

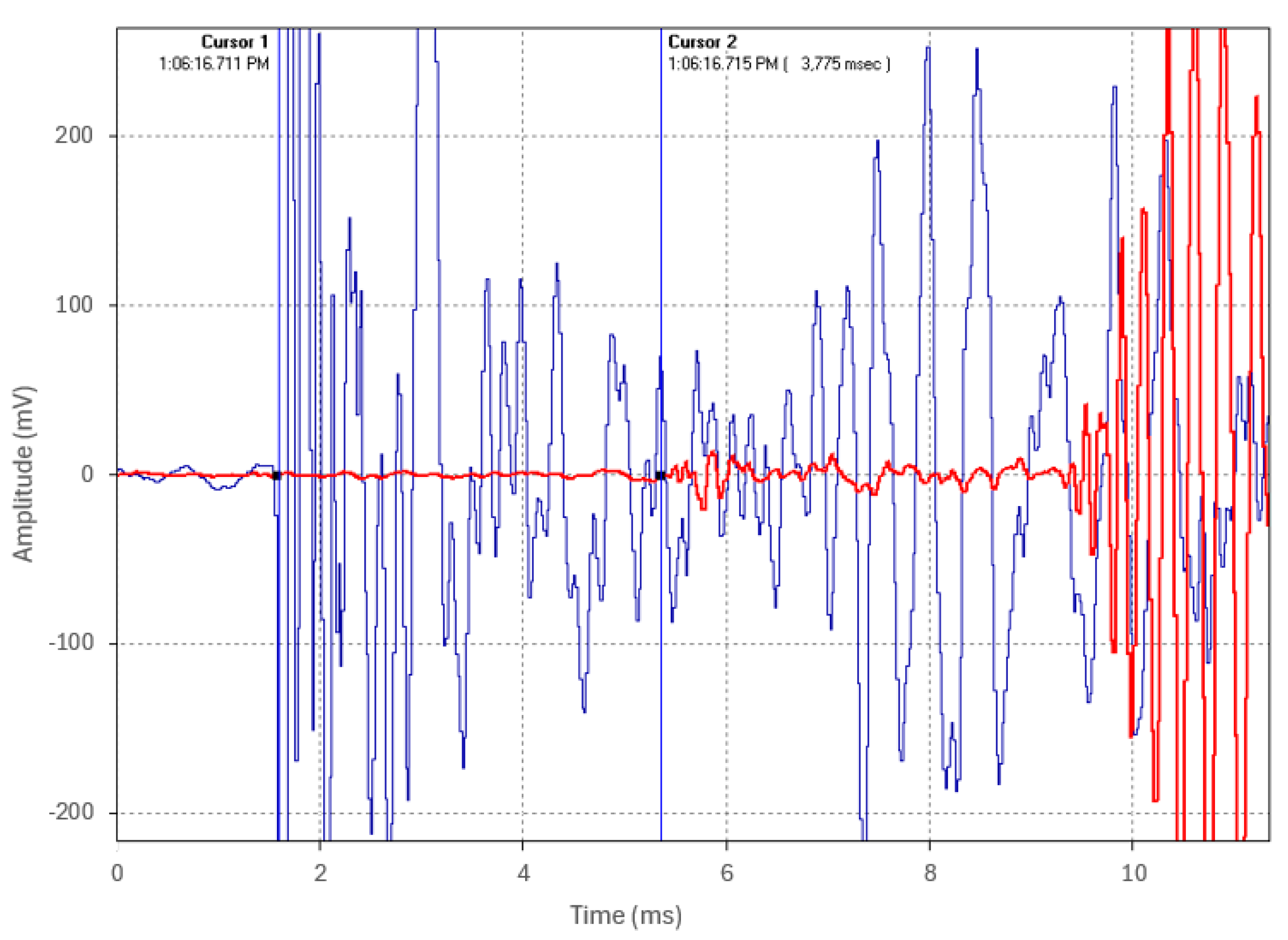

Figure 13.

Close-up snapshot of the timestamping of the acoustic waveforms captured by Sensors 1 and 4 (Test 1.1).

Figure 13.

Close-up snapshot of the timestamping of the acoustic waveforms captured by Sensors 1 and 4 (Test 1.1).

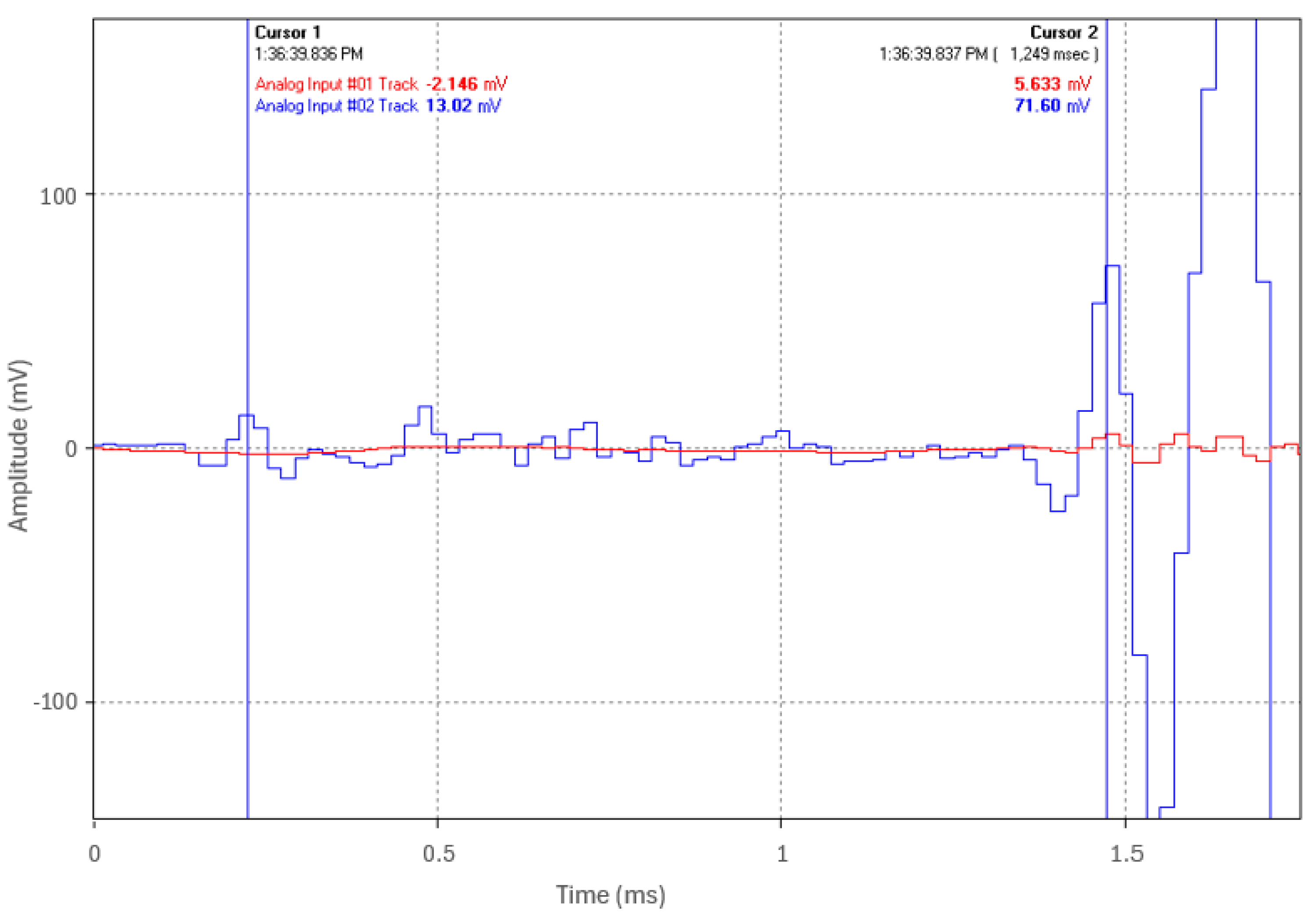

Figure 14.

TDOA of the acoustic pulse at pipe ends when an acoustic pulse is induced at one-third the length of the pipe (Test 1.2).

Figure 14.

TDOA of the acoustic pulse at pipe ends when an acoustic pulse is induced at one-third the length of the pipe (Test 1.2).

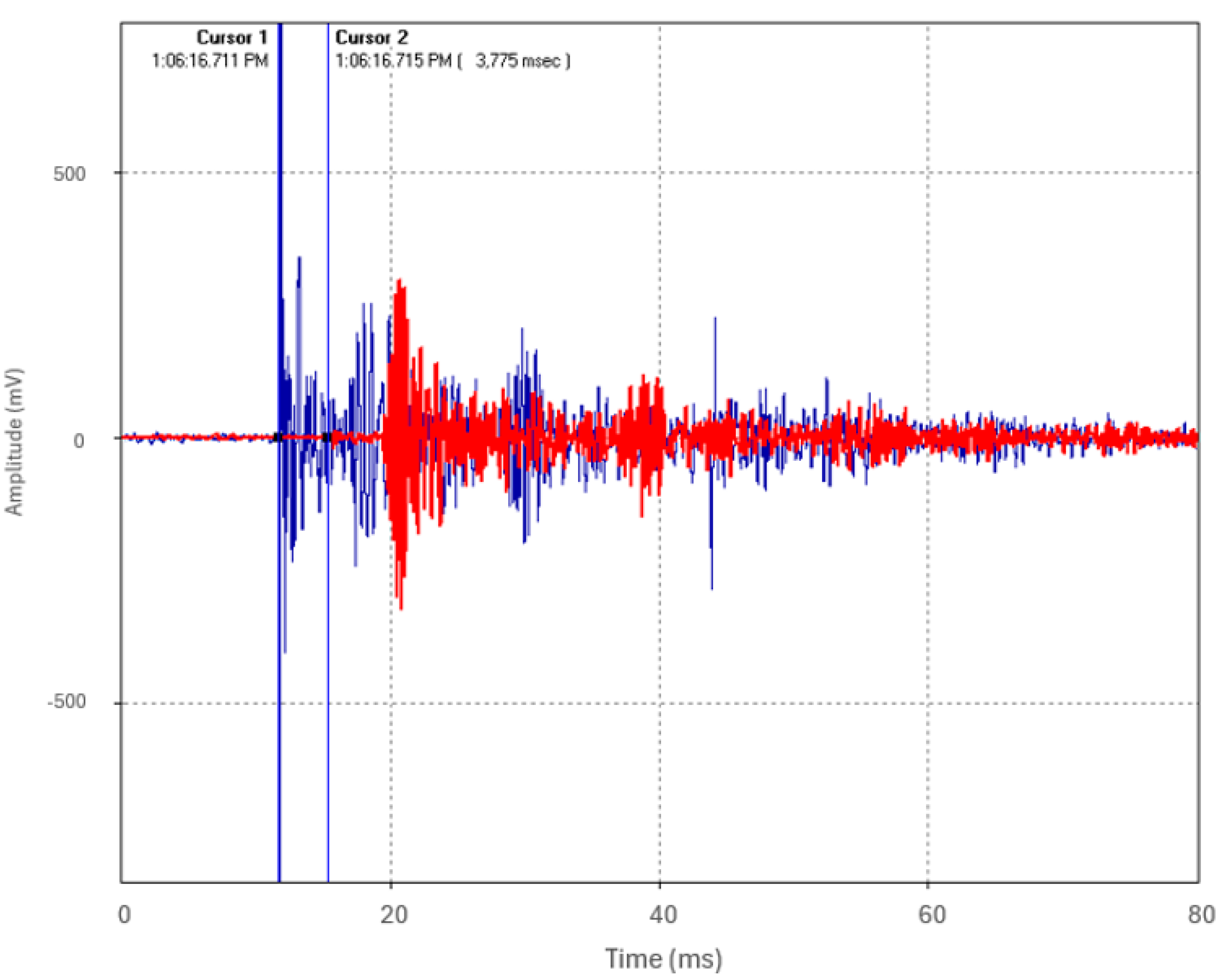

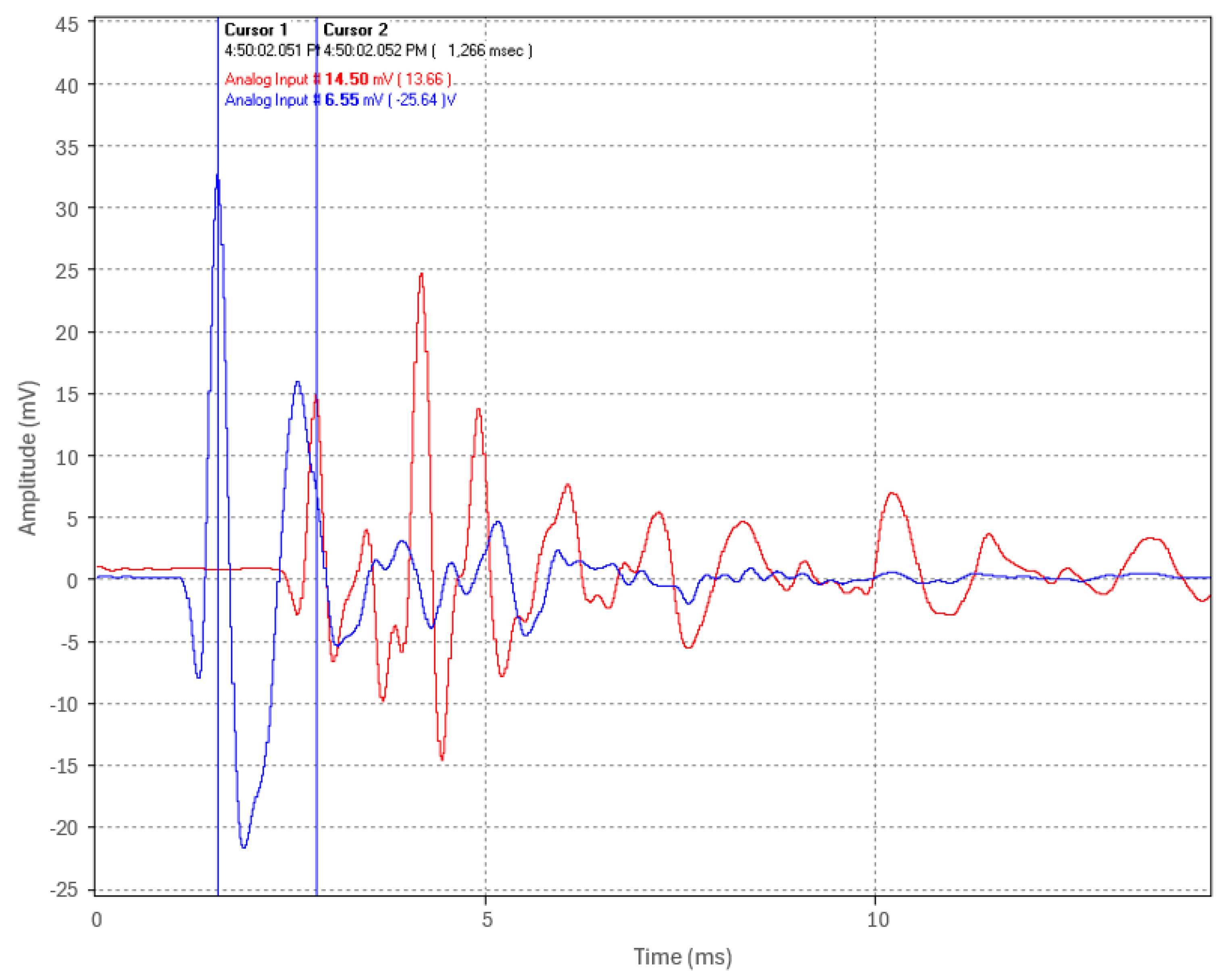

Figure 15.

Test 2 – Blue waveform (Sensor 1); Red waveform (Sensor 4).

Figure 15.

Test 2 – Blue waveform (Sensor 1); Red waveform (Sensor 4).

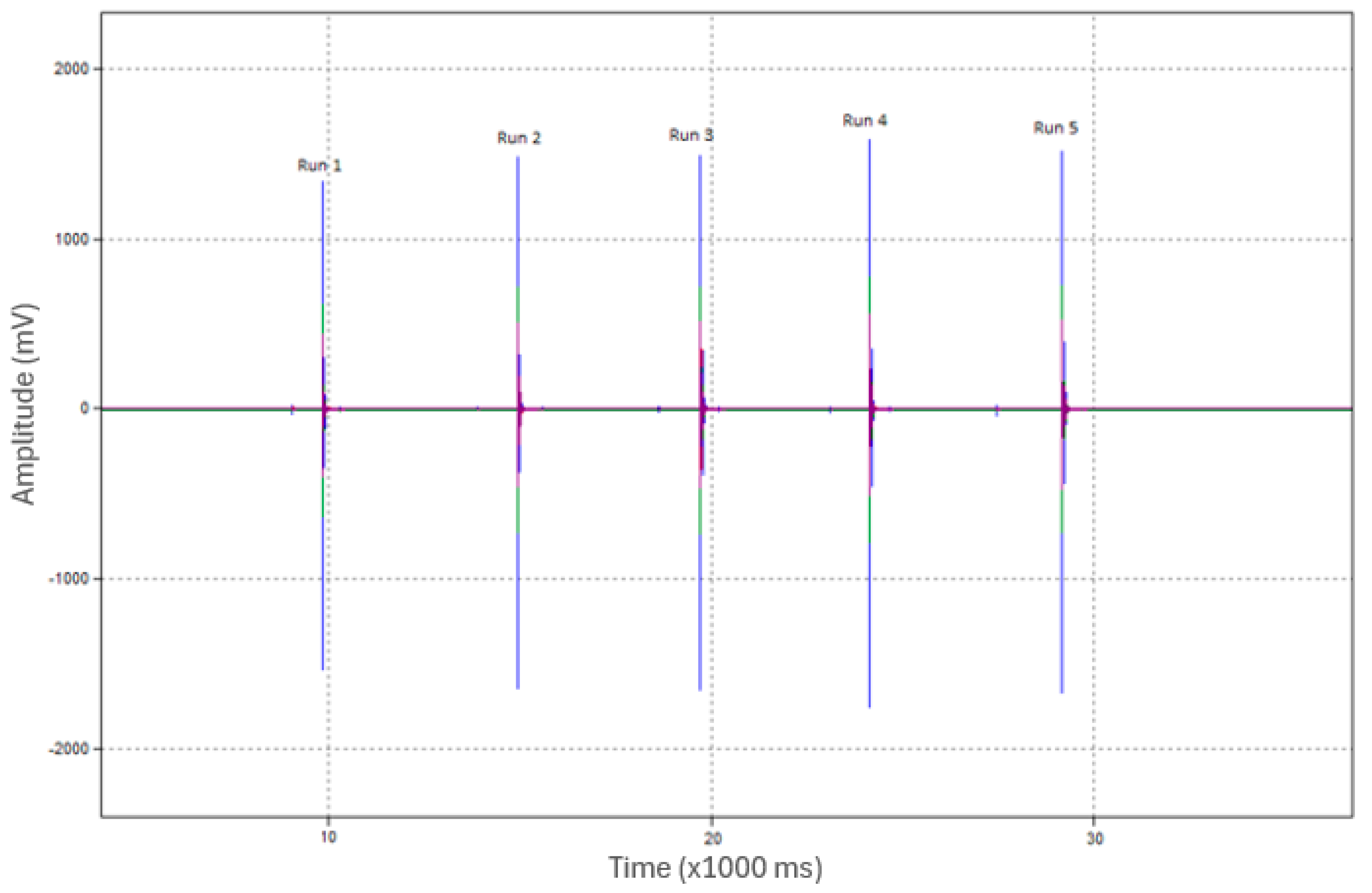

Figure 16.

Overview of peak amplitudes from Sensor 1 for the five test runs of Test 3.1.

Figure 16.

Overview of peak amplitudes from Sensor 1 for the five test runs of Test 3.1.

Figure 17.

Captured waveforms from Sensors 1,2,3 and 4 for Run 1 in Test 3.1

Figure 17.

Captured waveforms from Sensors 1,2,3 and 4 for Run 1 in Test 3.1

Figure 18.

Acoustic pulse attenuation profile as it propagates along the 19 m pipe in Test 3.1.

Figure 18.

Acoustic pulse attenuation profile as it propagates along the 19 m pipe in Test 3.1.

Figure 19.

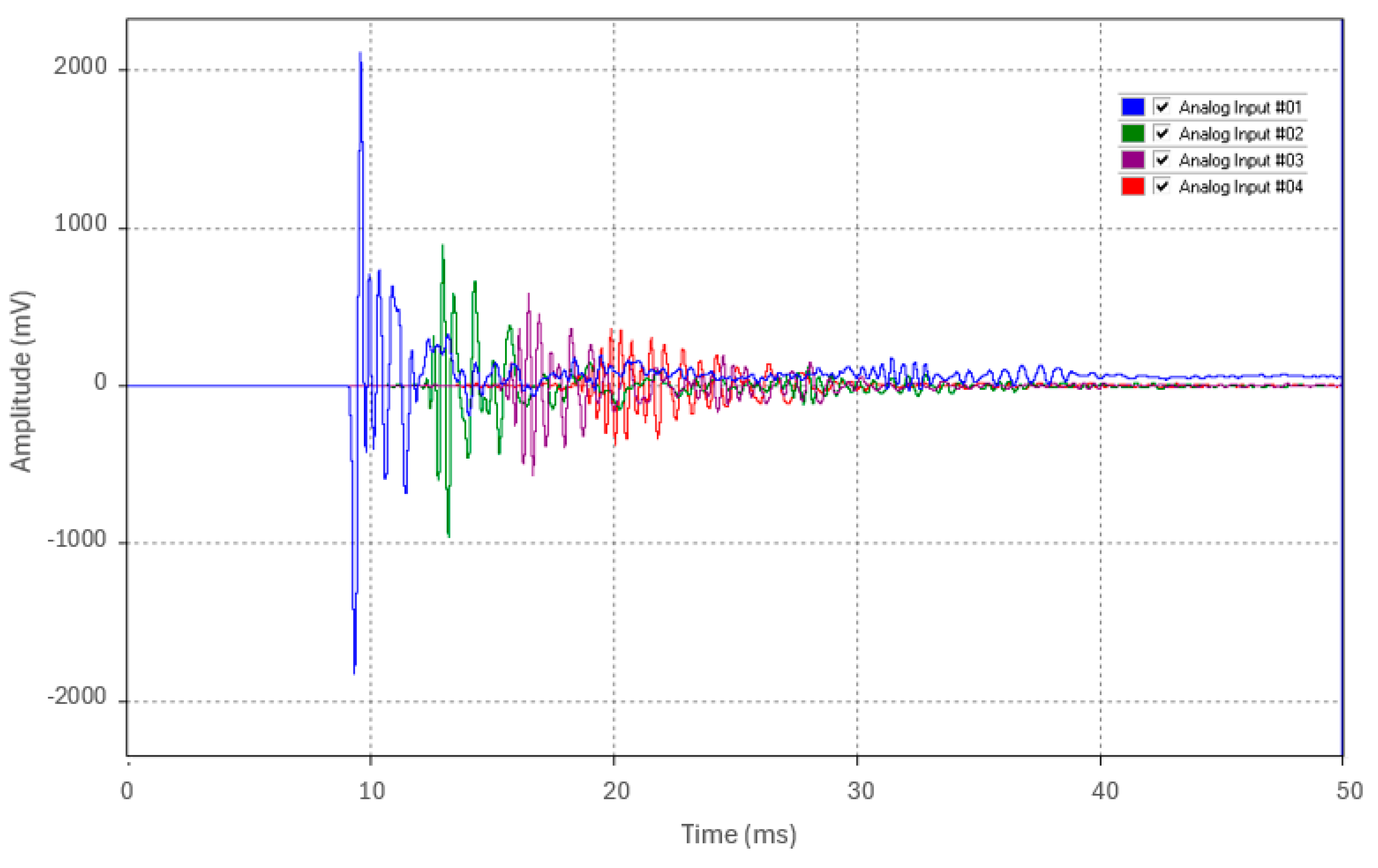

Waveforms from the four accelerometers of Run 1 in Test 3.2.

Figure 19.

Waveforms from the four accelerometers of Run 1 in Test 3.2.

Figure 20.

Acoustic pulse attenuation profile as it propagates along the 19 m pipe in Test 3.2.

Figure 20.

Acoustic pulse attenuation profile as it propagates along the 19 m pipe in Test 3.2.

Figure 21.

Waveforms from the four accelerometers of Run 1 in Test 3.3.

Figure 21.

Waveforms from the four accelerometers of Run 1 in Test 3.3.

Figure 22.

Acoustic pulse attenuation profile as it propagates along the 19 m pipe in Test 3.2.

Figure 22.

Acoustic pulse attenuation profile as it propagates along the 19 m pipe in Test 3.2.

Figure 23.

Fault induced acoustic pulse waveform captured by Sensors 1 and 4 (Test 4)

Figure 23.

Fault induced acoustic pulse waveform captured by Sensors 1 and 4 (Test 4)

Table 1.

Detailed parameters of the test pipe.

Table 1.

Detailed parameters of the test pipe.

| Item |

|

Value |

| Pipe Length |

|

19 meters |

Material

Young's Modulus (E)

Density (ρ)

Outer Diameter (OD)

Inner Diameter (ID)

Wall Thickness

External Coating

Internal Coating |

|

Carbon Steel

200 GPa

7850 kg/m3

60.33 mm

49.25 mm

5.54 mm (Sch. 80)

Pritec

Epoxy |

Table 2.

Detailed parameters of the B&K accelerometers.

Table 2.

Detailed parameters of the B&K accelerometers.

| Item |

|

Value |

| Product model |

|

B&K 4518-002 |

Sensitivity

Measurement range

Resonant frequency

Frequency range

Residual Noise Level

Maximum Operational Level (peak)

Mounting |

|

10 ±10% mV/g

± 500g

62 kHz

1 – 20000 Hz

2000 µg

500 g

Adhesive |

Table 3.

Detailed parameters of the B&K CCLD signal conditioner.

Table 3.

Detailed parameters of the B&K CCLD signal conditioner.

| Item |

|

Value |

| Product model |

|

B&K 1704-A-002 |

Maximum Frequency

Minimum Frequency

Maximum Gain (dB)

Minimum Gain (dB) |

|

55 kHz

2.2 Hz

× 100 (40 dB)

× 1 (0 dB) |

Table 3.

Specifications of the Delphin Expert Transient Data Logger.

Table 3.

Specifications of the Delphin Expert Transient Data Logger.

| Item |

|

Value |

| Product model |

|

Delphin Expert Transient |

Number of input channels

Number of output channels

Voltage range

Measurement accuracy

Max. input frequency / min. pulse width

Sampling rate |

|

4

8

± 25 V

0.5 mV + 0.008 %

1 MHz / 500 ns

20 Hz – 50 kHz |

Table 6.

Summary of the experimental tests conducted.

Table 6.

Summary of the experimental tests conducted.

| Test |

|

Objective |

Pulse Generation |

Embedment Condition |

Filter |

| 1.1 |

|

Acoustic velocity |

Weight drop, pipe end |

In air |

20 kHz LPF |

| 1.2 |

|

Localization accuracy |

Weight drop, 1/3 length |

In air |

20 kHz LPF |

| 2 |

|

Thumping-induced pulse |

Fault Simulator, pipe end |

In air |

20 kHz LPF |

| 3.1 |

|

Attenuation in air |

Weight drop, 5 reps, pipe end |

In air |

3 kHz LPF |

| 3.2 |

|

Attenuation on backfill |

Weight drop, 5 reps, pipe end |

On Tamped rock dust |

3 kHz LPF |

| 3.3 |

|

Attenuation embedded |

Weight drop, 5 reps, pipe end |

Fully embedded |

3 kHz LPF |

| 4 |

|

Fault pinpointing |

Fault simulator, 1/3 length |

Fully embedded |

3 kHz LPF |

Table 7.

Peak amplitudes at each of the four locations (Test 3.2).

Table 7.

Peak amplitudes at each of the four locations (Test 3.2).

| Title 1 Run# |

Sensor 1 Peak (mV) |

Sensor 2 Peak (mV) |

Sensor 2 Peak (mV) |

Sensor 2 Peak (mV) |

1

2

3

4

5 |

2114 |

892 |

586 |

365.3 |

| 1846 |

852.6 |

550.5 |

344.1 |

1961

2079

2070 |

909.6

848.6

855 |

590.8

553.1

551.5 |

362

339.3

338.2 |

| Average |

2014 |

871.6 |

566.4 |

349.8 |

| % Decrease |

|

56.7% |

35% |

38.2% |

| Atten. Coefficient |

|

0.132 Np/m |

0.068 Np/m |

0.076 Np/m |

Table 8.

Peak amplitudes at each of the four sensor locations (Test 3.3).

Table 8.

Peak amplitudes at each of the four sensor locations (Test 3.3).

| Title 1 Run# |

Sensor 1 Peak (mV) |

Sensor 2 Peak (mV) |

Sensor 2 Peak (mV) |

Sensor 2 Peak (mV) |

1

2

3

4

5 |

1716 |

233 |

13.4 |

4.4 |

| 1630 |

228 |

12.5 |

4.4 |

1663

1683

1662 |

233.2

242.2

234.6 |

13.2

14

13.3 |

4.4

4.7

4.1 |

| Average |

1670 |

234.2 |

13.3 |

4.4 |

| % Decrease |

|

86.0 % |

94.3 % |

66.9 % |

| Atten. Coefficient |

|

0.310 Np/m |

0.453 Np/m |

0.174 Np/m |