1. Introduction

Global postharvest losses of fresh fruit reach approximately 30–50%, primarily due to moisture degradation, microbial activity, mechanical damage, physiological aging and related disorders an issue exacerbated by inadequate cold chain infrastructure in many regions [

1]. The global fruit industry is facing increasing pressure to balance quality preservation, consumer safety, and environmental sustainability in postharvest supply chains. Fresh fruits, being physiologically active and perishable, are highly vulnerable to moisture loss, microbial decay, mechanical damage and physiological disorders during handling, storage, and transportation. Packaging performs an important and dynamic role in the postharvest handling of fruit and other horticultural produce [

2,

3,

4,

6]. The function of packaging is not only to protect the fruit from mechanical damage during handling and bulk transport [

2,

9,

10,

11,

12], but also to control moisture loss [

13,

14,

15], prevent contamination and regulate the modification of the gas composition around the commodity [

16]. Moreover, packaging can promote the marketability of the produce when traded at the retailer. Various types of packaging materials and package designs have been used in the postharvest handling of horticultural produce depending on the type of fruit, storage requirements, distribution, and marketing conditions [

17].

Traditionally, petroleum-based plastic packaging has been the dominant preservation method due to its excellent barrier properties, low cost, and scalability [

18]. However, the environmental consequences of plastic waste, coupled with shifting regulatory frameworks and consumer demand for eco-conscious products, have catalyzed the search for sustainable alternatives [

18,

19]. Among these, edible coatings, which are thin, consumable films applied directly onto fruit surface, have emerged as a promising class of bio-based packaging [

20]. Composed of natural polymers such as polysaccharides, proteins, and lipids, these coatings can serve as semi-permeable barriers to moisture, gases, and solutes, thereby modulating respiration rates, reducing water loss, and extending shelf life [

1]. Edible coatings can function not only as physical barriers but also as delivery systems for functional agents such as antimicrobials, antioxidants, and ripening inhibitors, thereby enhancing their protective efficacy [

21,

22]. When enriched with bioactive compounds such as plant-derived essential oils, these systems exhibit enhanced preservation [

23,

24].

Despite this potential, the application of edible coatings in the fresh fruit industry faces multiple critical challenges. Firstly, material compatibility is a major concern; the effectiveness of a coating depends on its interaction with the fruit's surface morphology, wax layer, and respiration physiology, and these properties vary widely between species and even cultivars [

25]. Secondly, coating functionality is limited by trade-offs among water barrier properties, gas permeability, and mechanical strength.

Another persistent issue affecting widespread use of edible coating is application scalability. While many edible coatings demonstrate efficacy under laboratory conditions, transitioning these systems to industrial-scale operations remains difficult due to challenges in uniform application, drying, and adhesion under variable humidity and temperature [

25,

26]. Moreover, regulatory ambiguity and lack of standardized approval procedures for edible coating formulations, particularly for coatings that include bioactive compounds, further hinder commercial adoption in global markets [

27,

28]. Additionally, low consumer acceptance poses a barrier, especially where coatings alter surface appearance, mechanical and surface properties, or perceived naturalness.

Furthermore, there is increasing evidence supporting the importance of developing holistic postharvest strategies. These strategies should integrate edible coatings with complementary cold chain postharvest technologies to fully enhance their potential. For instance, Valdés et al. [

29] highlighted the synergy between edible coatings and controlled atmosphere (CA) storage, showing their combined effect in reducing respiration rate and microbial spoilage in strawberries. In this regard, the compatibility of coatings with packaging formats that maintain humidity, gas balance, and physical protection is vital to avoid coating degradation, cracking, or inefficacy. The integration of such coatings into a smart packaging context, which may involve simplified indicators or passive sensors for ripening and freshness, can bridge functionality with sustainability, supporting both quality maintenance and reduced plastic reliance [

30].

While the literature presents a wide array of biopolymer-based coating materials and application techniques, research remains fragmented. Most studies focus on short-term physicochemical changes, overlooking long-term interactions between coating composition, fruit metabolism, and storage environment. Furthermore, comparative evaluations across fruit types, coating systems, and storage scenarios are limited, and comprehensive lifecycle or techno-economic assessments are rare. In response to these challenges, this review aims to examine the current state of bio-based and edible coatings for the fresh fruit industry. It synthesizes recent advances in material development, functional performance, and postharvest application strategies. By highlighting key technical barriers, regulatory gaps, and opportunities for integration with existing supply chains, this review seeks to provide a roadmap for future innovation and commercialization. Although the broader field of bio-based packaging includes efforts to replace synthetic plastics with biodegradable films and compostable containers, this review strictly focuses on edible coatings, which are biopolymer-based formulations applied as thin surface layers directly onto fresh fruits.

2. Edible Coating Materials

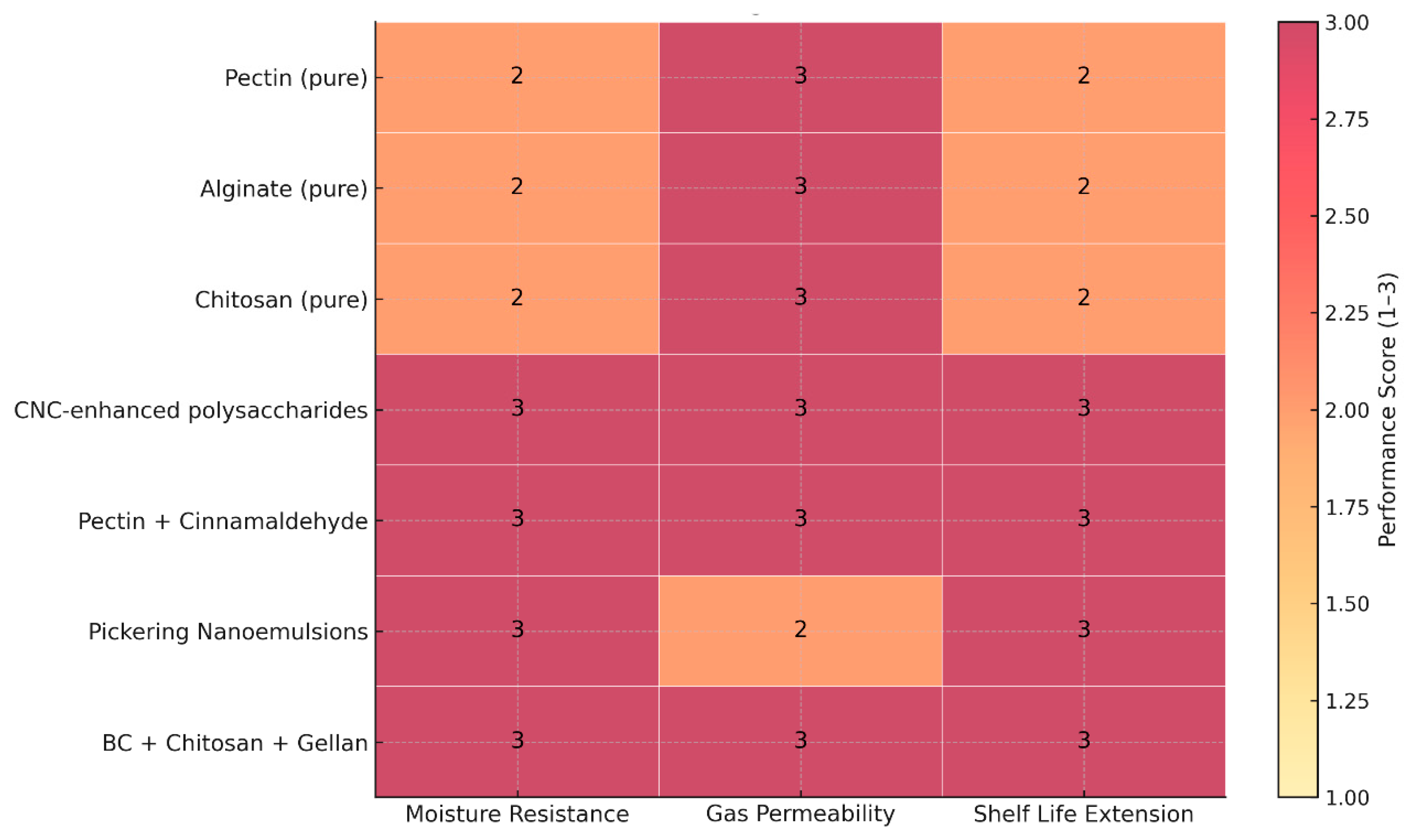

Table 1 summarizes the edible coating materials consistently supported by current postharvest literature, focusing on their moisture resistance, gas permeability, and demonstrated performance on specific fruits. A semi-quantitative heatmap (

Figure 1) was developed to facilitate direct comparison, using a standardized scoring system (1 = low, 2 = moderate, 3 = high) informed by empirical findings on water-vapor resistance, respiration compatibility, and shelf-life extension. This unified assessment framework highlights how different coating systems balance barrier function and physiological suitability. Pirozzi et al. [

31] highlighted that incorporating nanocellulose into edible-coating matrices can enhance barrier performance and structural integrity, supporting improved firmness and reduced dehydration during storage, although detailed water-vapor transmission rate (WVTR) measurements were not reported. Likewise, de Oliveira Filho et al. [

32] demonstrated that embedding Pickering nanoemulsions into pectin matrices strengthens mechanical robustness and improves moisture barrier effectiveness. González-Cuello et al. [

33] developed a multi-component coating system combining bacterial cellulose, chitosan, and gellan gum, achieving up to 15 days of strawberry shelf-life extension while preserving antioxidant content and reducing enzymatic deterioration. In contrast, traditional polysaccharide coatings—such as pectin, alginate, and chitosan—offer only moderate moisture resistance due to their hydrophilic nature. These materials maintain appropriate gas permeability but struggle to limit water loss effectively. As noted by Liyanapathiranage et al. [

34] and Miteluț et al. [

35], pectin coatings can reduce weight loss in strawberries but still allow significant moisture permeation compared to nanostructured or composite formulations. Wigati et al. [

36] report that cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) incorporation enhances barrier density without compromising oxygen and carbon-dioxide diffusion. These improved moisture barriers translate into better firmness retention and reduced dehydration, especially in high-respiration fruits.

The importance of tailoring edible-coating formulations to the physiological characteristics of individual fruits is clearly demonstrated across recent studies. Sun et al. [

37] showed that modifying a pectin matrix with trans-cinnamaldehyde effectively addressed the rapid moisture loss and browning typical of rambutan, illustrating how additive selection must respond to a fruit’s specific deterioration pathways. Likewise, the performance of alginate coatings on fresh-cut papaya, as reported by Tabassum and Khan [

38], reflects the coating’s compatibility with the high-respiration, enzyme-active nature of cut tissues—providing adequate gas exchange yet only moderate moisture protection. Chitosan-based coatings exhibit similar fruit-dependent behavior: while they support aerobic respiration across strawberries, apples, and bananas, they offer only limited resistance to the higher transpiration demands of these fruits [

39,

40]. Together, these findings underscore that no single polymer system performs optimally across all commodities; instead, coating composition, additives, and barrier properties must be strategically aligned with each fruit’s unique transpiration rate, respiration profile, and susceptibility to quality loss.

3. Multifunctionality of Edible Coatings in the Fresh Produce Supply Chain

3.1. Moisture Management and Transpiration Control

Moisture management and transpiration control are critical for maintaining postharvest fruit quality, as even moderate moisture loss can cause textural softening, shrinkage, and accelerated metabolic activity that sharply reduce marketable life [

42,

43,

44]. Transpiration—driven by water-vapor diffusion through the cuticle and lenticels—is strongly influenced by commodity type, storage temperature, and relative humidity. Under ambient conditions (20–25 °C), tomatoes and leafy vegetables may lose 5–10% of their weight within 3–5 days, whereas apples and pears held at 0–4 °C typically lose only 1–2% over two weeks [

45,

46]. Weight loss is generally quantified gravimetrically, and water-vapor transmission rate (WVTR) is expressed as grams of water lost per square meter per day (g/m²·day). Such losses impair turgidity, gloss, and perceived freshness, underscoring the need for effective moisture-control interventions during storage and distribution.

Plastic liners are widely used in commercial packaging to maintain high relative humidity (90–95%) around bulk produce, reducing moisture loss by 40–70% under practical conditions [

4]. These films—typically polyethylene or polypropylene—create a stable humid microclimate whose effectiveness depends on film thickness (20–50 µm), perforation density, and sealing integrity. Edible coatings, applied directly to fruit surfaces, serve as semi-permeable barriers that moderate WVTR while supporting adequate oxygen and carbon-dioxide exchange. Polysaccharide-based coatings such as alginate, chitosan, or starch have been shown to reduce weight loss by 30–60% relative to uncoated produce [

46,

47], although their performance depends on coating thickness (10–80 µm), inherent hydrophilicity, and compatibility with produce respiration rates. Improved outcomes have been observed when these coatings are modified with functional additives—including essential oils, hydrophobic modifiers, and nano-reinforcers—which can strengthen film density, enhance water-binding capacity, and reduce permeability, as demonstrated in starch-based, composite, and nanoparticle-enhanced systems [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. Cellulose-derived matrices and composite edible films further extend this potential by offering tunable microstructures and enhanced moisture-barrier integrity across a range of fruit commodities [

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60].

The performance of any moisture-control strategy is shaped by environmental conditions and intrinsic material properties. Plastic liners provide durable and scalable protection, achieving up to 70% moisture-loss reduction even under fluctuating humidity [

4], yet their non-biodegradable nature presents long-term environmental concerns. Edible coatings offer a biodegradable alternative but may vary in moisture-barrier effectiveness depending on formulation: plasticizers such as glycerol, for instance, can improve film flexibility but simultaneously increase WVTR by 10–15% [

42]. Because storage temperature (0–25 °C) and RH (50–95%) are primary drivers of transpiration, coating composition and application protocols must be calibrated to match each fruit’s respiration profile, surface morphology, and susceptibility to dehydration.

Table 2 provides a comparative summary of moisture-loss-reduction strategies across representative produce types, synthesizing trends and outcomes reported in the literature.

3.2. Effect of Edible Coatings on Gas Exchange and Respiration

Edible coatings form semi-permeable barriers to gases such as oxygen (O₂), carbon dioxide (CO₂), and ethylene (C

2H

4), thereby modifying the internal atmosphere of fresh fruits and vegetables (

Table 3). This selective permeability helps regulate respiration rates, mitigate oxidative stress, and delay senescence, thereby extending postharvest shelf life and preserving quality attributes such as firmness, color, and flavor [

46,

47]. The effectiveness of gas exchange regulation is largely influenced by the physicochemical composition and structural integrity of the coating. Polysaccharide-based coatings, such as those made from chitosan, alginate, or pectin, are hydrophilic and exhibit relatively high gas permeability, making them suitable for high-respiration fruits where excessive gas restriction could be harmful. In contrast, lipid-based or composite coatings incorporating waxes and fatty acids offer lower O₂ permeability, which is beneficial for moderate-respiration fruits but may pose a risk of anaerobic conditions in produce requiring higher gas exchange.

Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that cellulose nanocrystal-reinforced chitosan coatings reduced O₂ transmission rates while maintaining CO₂ permeability, thereby effectively delaying ripening and preserving firmness in coated strawberries [

49]. Similarly, edible films enriched with essential oils or hydrophobic compounds, such as sunflower wax, have provided improved control over CO₂ accumulation and moisture loss in fruits like blueberries and grapes [

50] Such coatings effectively create a micro-modified atmosphere around produce, analogous to modified atmosphere packaging (MAP) but with enhanced sustainability benefits. However, excessively low O₂ permeability may trigger anaerobic respiration, resulting in ethanol accumulation and undesirable flavor development. Therefore, precise optimization of coating thickness, composition, and application method is critical to aligning gas barrier performance with the respiratory demands of each fruit species [

50]. Du et al. [

51] demonstrated that by tuning the layer-by-layer assembly of chitosan and sodium alginate coatings, it is possible to match the gas barrier properties of the coating to the respiration characteristics of specific fruits. Their study showed that optimized coatings extended the shelf life of strawberries, tangerines, and bananas by 2, 4, and 4 days, respectively, by maintaining an appropriate modified atmosphere. Nonetheless, further studies are warranted to quantify O₂ and CO₂ transmission under dynamic storage conditions and to develop standardized approaches for coating customization based on produce type and storage duration.

3.3. Microbial Control and Food Safety

Table 4 presents selected literature on antimicrobial edible coatings in fresh produce. Edible coatings have garnered significant attention not only for their barrier functions but also as carriers for antimicrobial agents that enhance the microbial safety of fresh fruits. These coatings can inhibit microbial growth on fruit surfaces either through direct contact or by gradually releasing antimicrobial compounds into the fruit's immediate environment. Among the most extensively studied antimicrobial additives are essential oils, bacteriocins, and metal-based nanoparticles such as silver. Essential oils, particularly those derived from thyme, clove, and cinnamon, are rich in bioactive compounds like thymol, carvacrol, and cinnamaldehyde. These compounds exhibit broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity through mechanisms such as disruption of microbial cell membranes and interference with metabolic pathways. Sarengaowa et al. [

57] demonstrated that a chitosan-based coating enriched with cinnamon oil significantly inhibited microbial growth, delayed browning, and maintained the quality of fresh-cut potatoes stored at 4 °C. Similarly, Vidyarthi et al. [

58] found that coatings incorporating thyme and clove oils helped suppress spoilage and maintained the antioxidant activity in green chilli, indicating similar potential for other fresh produce.

Inorganic antimicrobial agents, such as silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), have also been used in edible coating formulations due to their strong and broad-spectrum antibacterial activity. Bizymis et al. [

59] developed a multi-component coating based on chitosan, cellulose nanocrystals, β-cyclodextrin, and silver nanoparticles, which achieved over 96% reduction in Escherichia coli populations on cherries. Furthermore, this coating maintains fruit firmness and color during cold storage, while also decreasing oxygen and water vapor permeability. The integration of such coatings with cold storage protocols significantly improved microbial suppression compared to refrigeration alone, highlighting the value of synergies between physical and biochemical preservation methods. Nevertheless, while promising, the application of antimicrobial edible coatings is not without challenges. One major concern is the potential development of microbial resistance due to continuous exposure to sub-lethal concentrations of antimicrobials, particularly essential oils. Though resistance mechanisms like efflux pumps and membrane adaptation have been proposed, long-term data from fresh fruit systems remain limited [

57]. Similarly, silver nanoparticle-based coatings raise questions regarding food safety, toxicity, and environmental persistence, as residues may remain on fruit surfaces post-application. These factors complicate regulatory approval. In certain jurisdictions, such as the United States or European Union, AgNP-containing coatings may be classified under pesticide legislation, requiring extensive safety evaluations before commercial deployment [

59].

To address these limitations, researchers advocate for the use of antimicrobial coatings in conjunction with traditional sanitation methods. For example, combining chitosan-thyme oil coatings with mild washing or UV-C treatment has shown improved efficacy in microbial control, without the need for high concentrations of active ingredients [

58]. This integrative strategy may mitigate regulatory hurdles while still enhancing safety and shelf life. Despite extensive laboratory validation, significant research gaps persist. Most studies have focused on short-term storage under controlled conditions. There is a pressing need for long-term trials simulating real-world logistics involving fluctuating temperatures, handling stresses, and varying humidity levels. Moreover, little is known about the interaction between antimicrobial coatings and naturally occurring fruit microbiota, including beneficial epiphytic organisms. Addressing these gaps will require interdisciplinary research involving microbiology, food safety, postharvest physiology, and regulatory science. Scalable, safe, and effective antimicrobial coatings will only be realized when materials science converges with industrial practice and policy alignment.

3.4. Nutritional and Sensory Quality Retention

Edible coatings play a vital role in preserving the nutritional quality and sensory appeal of fresh fruits, maintaining key attributes such as vitamin C, phenolic content, color, flavor, and texture.

Table 5 shows the impact of edible coatings on nutritional and sensory quality. Biopolymer-based films, especially those incorporating natural waxes, polysaccharides, proteins, or composites, have demonstrated effectiveness in safeguarding biochemical nutrients during cold storage, thereby extending shelf life and consumer acceptability. For example, a carnauba wax coating applied to Moro oranges significantly reduced weight loss and helped maintain fruit firmness, anthocyanin levels, and vitamin C over an 80-day period. Although antioxidant levels declined over time, the preservation of firmness and color was deemed promising [

61]. Polysaccharide films infused with pomegranate peel extract or Spirulina phenolics have similarly protected vitamin C and total phenolic content in mango, strawberry, and lime, with enhanced enzyme activity and delayed browning [

42,

62]. Texture and visual appearance remain core quality metrics. A sodium alginate–based coating applied to pineapple effectively preserved brightness and structural integrity without affecting sensory qualities [

62]. Xanthan gum coatings with lemongrass oil on mandarin fruits preserved titratable acidity, soluble solids, vitamin C, and antioxidant levels while reducing weight loss and spoilage [

63]. In apples, whey protein and zein-based coatings have been used to mitigate browning and maintain firmness and natural aroma over extended storage [

64].

In a study by Siringul & Aminah [

65], mango cubes coated with seaweed paste that was formulated with varying concentrations of K. alvarezii and gum Arabic exhibited significantly reduced weight loss and retained firmness over 14 days of refrigerated storage. The coatings also maintained neutral sensory attributes, with no adverse effects on taste or aroma, and were well accepted by a trained panel. These findings suggest that K. alvarezii-based coatings can effectively create a micro-modified atmosphere around the fruit, reducing moisture loss and oxidative degradation while preserving texture. The study highlights the potential of seaweed coatings as a sustainable alternative to conventional packaging, especially for minimally processed tropical fruits. In a study by Dulta et al. [

66], oranges coated with a layered formulation of 1% chitosan and 1.5% sodium alginate, supplemented with 0.5 g/L ZnO nanoparticles, exhibited markedly reduced mold growth, improved firmness, and higher retention of vitamin C over a 20-day refrigerated storage period. Similarly, carboxymethyl chitosan–gelatin coating maintained firmness and antioxidants in sweet cherries [

67], while strong adhesion improved the retention of turmeric oil in chitosan films, enhancing antioxidant activity [

68]. For black mulberries, coatings extended shelf life and preserved sensory traits [

69], and alginate or chitosan coatings with avocado extract kept minimally processed apples fresh and appealing [

70]. Overall, optimized formulations and adhesion are key to sustaining nutritional and sensory quality across diverse fruits.

Despite these benefits, sensory drawbacks occasionally emerge. Waxy coatings may impact mouthfeel or gloss, causing an unnatural sheen, and thick films may retain ethanol-like flavors due to restricted respiration [

61]. Consumers generally tolerate coatings that are invisible and leave no flavor residues; however, any perceivable “film” could reduce purchase intent. Transparency in labelling and clear communication about the coating's natural origin, eco-friendliness, and health safety can enhance consumer acceptance.

3.5. Environmental Concerns and Limitations

Edible coatings have emerged as promising technology to extend the shelf life and maintain the quality of fresh produce within the supply chain. However, their integration into large-scale agricultural and commercial systems raises significant environmental concerns and operational limitations.

Table 6 shows the environmental and operational metrics of edible coatings compared to synthetic plastics. These challenges include the ecological footprint of raw materials, the end-of-life disposal of coated produce, and the scalability of production processes.

The production of edible coatings involves raw materials such as polysaccharides (e.g., chitosan, alginate), proteins, and lipids, which are derived from natural or agricultural sources. Although biodegradable, the cultivation and processing of these materials can contribute to environmental degradation. For instance, Mohammadi et al. [

42] noted that chitosan production entails deacetylation of chitin from crustacean shells, which requires considerable chemical and thermal inputs, increasing emissions. Similarly, large-scale extraction of alginate from brown seaweed, if not managed sustainably, may impact marine ecosystems [

44]. Starch-based coatings made from crops like corn or cassava are water-intensive and may compete with food production, raising sustainability concerns [

48].

The disposal of coated produce also presents challenges. Although edible coatings are biodegradable under composting conditions, field degradation is often incomplete. For example, Bharti et al. [

48] reported partial breakdown of polysaccharide-based coatings after 90 days under controlled composting, with incomplete mineralization in high-humidity landfill scenarios. This may lead to temporary organic residue accumulation, although still significantly lower than the persistence of synthetic packaging materials. In contrast, polyethylene liners used in fresh produce packaging are durable but contribute to long-term plastic pollution.

Scalability and process efficiency remain major constraints in the commercial deployment of edible coatings. Industrial application methods—typically dipping, spraying, or brushing—must achieve consistent coating thicknesses (10–80 µm) across heterogeneous fruit surfaces. However, equipment limitations, surface topography, and high line speeds often reduce uniformity at scale. Mohammadi et al. [

42] reported a 20–30% decline in coating efficiency during high-throughput operations, largely driven by incomplete coverage on irregular or highly textured produce.

Despite these operational challenges, edible coatings are gaining momentum in postharvest systems. Synthetic wax coatings continue to dominate due to their long-established industrial use, compatibility with existing equipment, and predictable performance. However, recent advances in bio-based edible coatings—supported by growing evidence of their functional, physiological, and quality-preserving benefits [

25]—are increasingly positioning them as strong alternatives for high-value commodities. These formulations offer improved barrier properties, opportunities for functionalization (e.g., antimicrobials, antioxidants), and enhanced alignment with sustainability-driven supply chain goals. Environmental considerations further shape the comparison. Synthetic coatings incur a notable carbon footprint during polymer production, estimated at approximately 2–3 kg CO₂e per kilogram of polyethylene. In contrast, edible coatings derive from renewable biopolymers but often require higher processing energy per unit mass due to extraction, purification, and formulation steps [

44]. Thus, while edible coatings present a promising eco-aligned pathway, their sustainability benefits are closely tied to upstream processing efficiencies and material sourcing.

Regulatory and safety concerns also affect adoption. Edible coatings must comply with food safety standards such as FDA 21 CFR 172.615, which limits the use of certain active ingredients like essential oils to below sensory thresholds (e.g., 0.5%), sometimes at the expense of antimicrobial efficacy. Bharti et al. [

48] highlighted that reducing EO concentrations to meet sensory requirements diminished inhibition zones by up to 40%. In contrast, synthetic waxes face fewer formulation restrictions but may contain components of concern, such as paraffin, which have been associated with potential health risks under chronic exposure.

Environmental impact assessment is conducted using standardized methods such as ISO 14040/14044 for Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and ISO 14855 for biodegradability in composting environments. Congying et al. [

44] applied these frameworks to compare edible coatings and plastic films, with results indicating 60–70% degradation of chitosan-based coatings within 90 days under optimal composting, versus near-zero biodegradation for polyethylene. These findings underscore the trade-off between biodegradability and performance.

Ultimately, the ecological footprint of edible coatings depends on their source, formulation, and end-of-life handling. Sustainable sourcing practices, such as seaweed farming certifications, and the reuse of agro-waste for biopolymer extraction can reduce environmental impacts. Congying et al. [

44] noted that coatings made from cellulose-rich mango waste demonstrated a 10–15% reduction in processing energy and improved degradation profiles. Nevertheless, both edible and synthetic systems face challenges. Edibles must improve application efficiency and degradation rates, while synthetics require innovations in recyclability and pollution control.

4. Strategies for Optimizing Edible Coatings in Fresh Fruit Preservation

4.1. Material Selection and Formulation

Table 7 shows strategies for optimizing edible coatings in fresh fruit preservation. The functional properties of coatings, such as barrier behavior, antimicrobial activity, and sensory neutrality, are deeply influenced by the type and combination of materials used. Edible coatings are constructed primarily from biopolymer materials such as polysaccharides (alginate, chitosan, pectin, cellulose derivatives), proteins (zein, gelatin), and lipid-based components (beeswax, carnauba wax). These materials form the structural matrix of coatings and films, enabling them to act as moisture and gas barriers while providing functional sites for antimicrobial or antioxidant incorporation. Their widespread use in fruit and vegetable preservation is well reflected in studies such as [

27,

61], and [

28], which collectively highlight their versatility and compatibility with fresh-produce surfaces.

To enhance functional performance, bioactive additives—including essential oils, metal nanoparticles such as ZnO or Ag, and plant extracts—are often incorporated into these biopolymer matrices. These compounds are valued for their antimicrobial and antioxidant properties, enabling extended shelf life and reduced microbial spoilage. Representative examples include silver-nanoparticle composites, Spirulina-enriched coatings, and essential-oil–reinforced chitosan films, as demonstrated in [

47,

59], and [

57]. The preparation of these coatings relies on robust formulation methods, including solution casting, homogenization of emulsions, nanoparticle dispersion, and ultrasonication. These processes are critical for achieving stable, homogeneous coating systems, ensuring proper distribution of active compounds within the matrix. Studies such as [

66,

69] illustrate the practical application of these methods in producing uniform, high-performance edible films and coatings. Once formulated, edible coatings are commonly applied to produce via dipping, spraying, or brushing. These simple, scalable techniques enable uniform deposition across variable fruit surfaces and can be integrated into commercial processing operations. Their practical relevance is evident in applications described in [

47,

57,

69], where controlled immersion or spraying produced consistent coating layers.

Evaluating coating performance often begins with moisture barrier analysis, typically through water vapor permeability (WVP) or WVTR measurements. These analyses quantify the coating’s ability to reduce moisture loss and thus prevent textural degradation in produce. The significance of WVP in edible film optimization is highlighted in studies such as [

31] and [

43], where nanocellulose- and chitosan-based films demonstrate measurable improvements in barrier properties. Gas exchange behavior is equally critical. Gas permeability analysis, including O₂/CO₂ transmission or headspace measurements, ensures that coatings do not impede normal respiration to the point of inducing anaerobiosis or off flavors. Reviews and experimental studies such as [

16,

73] provide methodological frameworks for understanding these gas-exchange dynamics within coated or MAP-treated fresh produce.

Mechanical performance is assessed through tensile strength, elongation, and modulus testing, which determines a film’s durability, flexibility, and suitability for handling. Mechanical characterization is especially important for films that must withstand stacking, abrasion, or packaging stress. Such analyses are prominently discussed in [

31,

48], demonstrating how structural modifications influence mechanical integrity. The antimicrobial effectiveness of coatings is verified through microbiological assays such as zone-of-inhibition testing, microbial counts, or in situ challenge studies. These tests confirm the coating’s ability to suppress spoilage organisms or pathogens, as documented in [

57,

59], where nano-enhanced or essential-oil–enriched coatings effectively reduced microbial loads during storage. Coating evaluation also involves nutritional and chemical analyses, typically using spectrophotometry or HPLC to quantify vitamin C, phenolics, and antioxidant capacity. These methods help assess how coatings preserve nutritional quality over time. For example, [

61,

70] provide detailed insight into antioxidant retention and biochemical stability in coated apples and citrus.

Sensory evaluation—via consumer or trained panels—plays a crucial role in determining a coating’s acceptability. These assessments identify potential defects such as waxiness, off-flavors, or undesirable textures. Sensory methodologies and outcomes are thoroughly described in [

69,

70], which show how coatings influence appearance, aroma, flavor, and overall consumer preference. Finally, advanced analytical techniques such as SEM, FTIR, XRD, and DSC/TGA provide deep insight into microstructure, chemical interactions, crystallinity, and thermal stability. These tools support the development of improved formulations and structure–property relationships. Key examples include nanocellulose-reinforced and essential-oil composite films studied in [

31,

36,

48], demonstrating how these techniques drive innovation in edible-coating materials science.

4.2. Coating Application Techniques

The method used to apply edible coatings to fruit and vegetable surfaces significantly influences the coating’s uniformity, functional performance, and industrial applicability. These application techniques determine the coating’s barrier properties, adhesion, and consistency, which in turn affect its effectiveness in preserving fresh produce throughout the supply chain. Common methods include dipping, spraying, brushing, and layer-by-layer (LbL) deposition, while emerging innovations such as electrostatic spraying and ultrasonic atomization show promise for scalable precision.

4.2.1. Dipping

Bulleted lists look like this: Dipping remains the most prevalent in laboratory settings due to its simplicity and full-surface coverage. It typically involves immersing the produce in a 1–3% (w/v) coating solution for 1–5 minutes, followed by drying at 20–30°C for 30–60 minutes [

42]. Dipping achieves coating thicknesses of 10–100 µm, influenced by solution viscosity and immersion time. The process is underpinned by wetting dynamics described by Young’s equation:

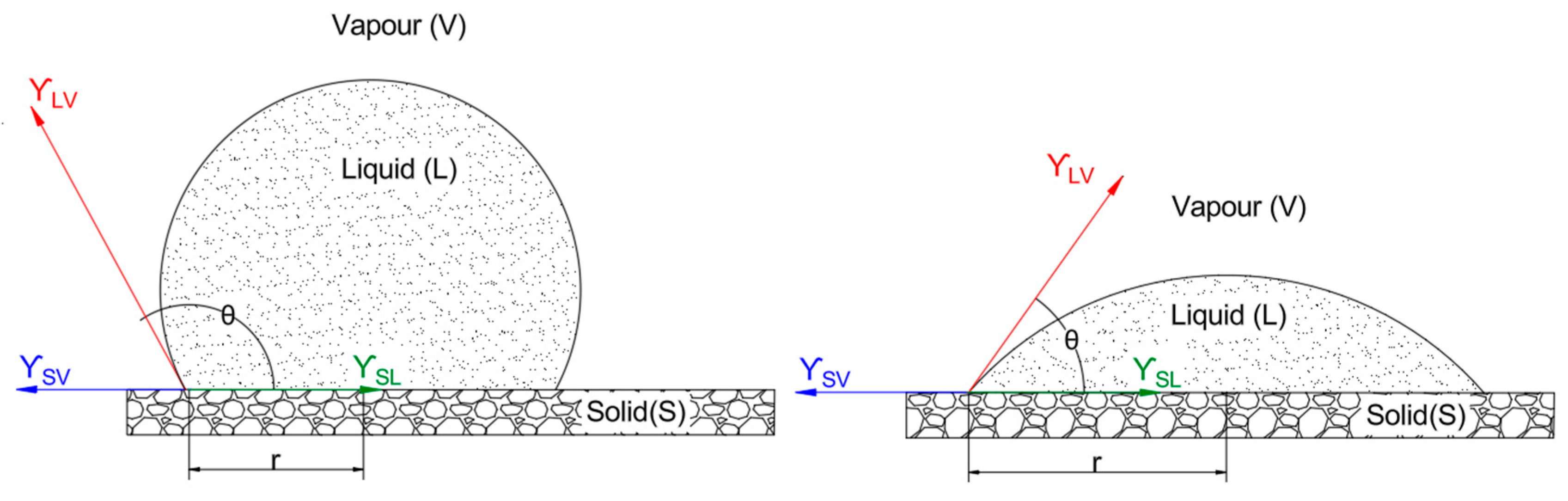

The interfacial interactions involved are illustrated in

Figure 2, which shows a liquid droplet on a solid surface in equilibrium with the vapor phase, including the relevant surface tensions (γ

SV, γ

SL, γ

LV) and contact angle (θ) as defined by Equation 1. θ, measured through the liquid, represents the angle at which the liquid-vapor interface meets the solid surface, indicating the degree of wetting where θ < 90° suggests good wetting (hydrophilic behaviour), while θ > 90° indicates poor wetting (hydrophobic behaviour). The interfacial tension between the solid and vapor phases, γ

SV, reflects the surface energy of the solid in the absence of the liquid, while γ

SL , the interfacial tension between the solid and liquid phases, depends on interactions such as hydrogen bonding or van der Waals forces between the coating solution and the fruit cuticle. Lastly, γ

LV, the interfacial tension between the liquid and vapor phases, is equivalent to the surface tension of the coating solution, typically ranging from 30–70 mN/m for aqueous polysaccharide solutions.

4.2.2. Brushing

Brushing is employed experimentally or for irregular surfaces, applying coatings with manual or mechanical brushes at a rate of 50–100 g/m². Thickness ranges from 20–60 µm, but uniformity is lower, with variations up to 20% across surfaces [

69]. The method relies on frictional force and manual precision, lacking scalability for industrial use. Its theoretical foundation is based on contact mechanics, where coating distribution depends on brush pressure, bristle texture, and solution rheology, particularly viscosity and shear-thinning properties [

48]. Due to its dependence on operator technique, this method can lead to inconsistency, especially for produce with complex geometries like strawberries or mulberries [

33]. Brushing is generally reserved for small-scale applications or laboratory settings where other techniques are not feasible.

Although simple and low-cost, the technique is less efficient, processing only 50–100 kg/hour and showing lower repeatability compared to dipping or spraying. Bharti et al. [

48] observed greater variability in coating thickness and phenolic compound retention for brushed samples of mangoes compared to sprayed samples. Similarly, Rather & Mir (2023) noted that in strawberries, brushing produced uneven barriers that compromised moisture control and antimicrobial efficacy relative to chitosan-based dipping. These findings underline that while brushing may serve niche applications, it is not ideal for large-scale operations where uniformity and throughput are critical.

Furthermore, surface energy of the fruit, coupled with contact angle behavior, influences coating spread and adhesion during brushing. As with other methods, brushing is sensitive to environmental factors such as temperature and humidity, which alter coating viscosity and drying rate. Brushing is thus best viewed as a supplementary or pilot-stage method, useful for experimental formulations but suboptimal for postharvest logistics on a commercial scale.

4.2.3. Layer-by-Layer (LbL)

LbL deposition involves sequential application of oppositely charged layers (e.g., cationic chitosan and anionic alginate) via dipping or spraying, with 5–15 layers achieving thicknesses of 50–150 nm per layer, totalling 0.5–2 µm [

69]. The technique exploits electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding, governed by the Derjaguin-Landau-Verwey-Overbeek (DLVO) theory, allowing tailored functionality and improved barrier properties. Memete et al. [

69] demonstrated that gelatin and lipid LbL coatings on mulberries retained 85% of phenolic compounds over 8 days at 4°C, extending shelf life by 20% compared to single-layer coatings.

LbL systems offer advantages in controlled release of bioactives and multilayered protection against moisture and gas exchange. Bharti et al. [

48] also highlighted the potential of multilayer systems in starch-based matrices for improving antimicrobial efficacy, showing over 90% inhibition against gram-positive bacteria after 5 days of storage. However, the process requires precision and extended processing time, typically 2–4 hours per batch, thereby limiting throughput to 20–50 kg/hour and increasing operational complexity. The LbL process benefits from optimization of interlayer adhesion, pH control, and ionic strength of the coating solutions to avoid delamination. Temperature and humidity also affect layer stability during storage, particularly in coatings incorporating thermosensitive ingredients. Despite its labor-intensiveness, LbL is highly promising for research and premium applications where multifunctionality and precision are prioritized over scale.

4.3. Analytical and Evaluation Methods

Thorough evaluation of edible coatings involves a range of physical, chemical, microbiological, and sensory tests. These assessments are necessary to determine barrier properties, nutritional retention, microbial inhibition, structural integrity, and consumer acceptability.

4.3.1. Barrier Properties

The water vapor transmission rate (WVTR) is a fundamental metric for moisture control in edible coatings and packaging films. It is commonly measured using gravimetric cup methods, such as the Desiccant and Water Methods, under standardized conditions defined by ASTM E96/E96M-23. These tests quantify vapor flux by monitoring weight changes in coated samples under controlled temperature and humidity. In a study by Pizato et al. [

72], strawberries coated with 2% chitosan enriched with 1.5% clove essential oil exhibited significantly reduced weight loss, 13.51% compared to 24.19% in uncoated controls, over 12 days of refrigerated storage. This reduction in moisture loss was attributed to the coating’s semi-permeable barrier properties, which effectively modulated WVTR while preserving texture and color. Gas permeability, particularly for oxygen (O₂) and carbon dioxide (CO₂), is equally critical for assessing the impact of coatings on fruit respiration and anaerobic risks. As reviewed by Sánchez-Tamayo et al. [

73], gas permeability in edible films is typically measured using manometric, gravimetric, or continuous-flow techniques, many of which are adapted from ASTM standards. These methods involve placing the film between two compartments, one exposed to the test gas and the other connected to a detector and quantifying the transmission rate under controlled conditions. The review emphasizes that permeability results are highly sensitive to film preconditioning, test setup, and environmental parameters, underscoring the need for standardized protocols when evaluating barrier performance in postharvest applications.

4.3.2. Mechanical Behavior

Mechanical behavior is an essential but often under interpreted dimension of edible-coating performance. Although coatings applied on fruit surfaces typically form thin layers in the 5–20 µm range, mechanical characterization is almost universally conducted on free-standing cast films—usually 50–200 µm thick—which serve as model systems for assessing the intrinsic strength and flexibility of coating formulations. While these films differ in thickness from applied coatings, their tensile properties provide meaningful insight into how biopolymer networks respond to deformation, bending, and surface stress encountered during handling, transport, and storage.

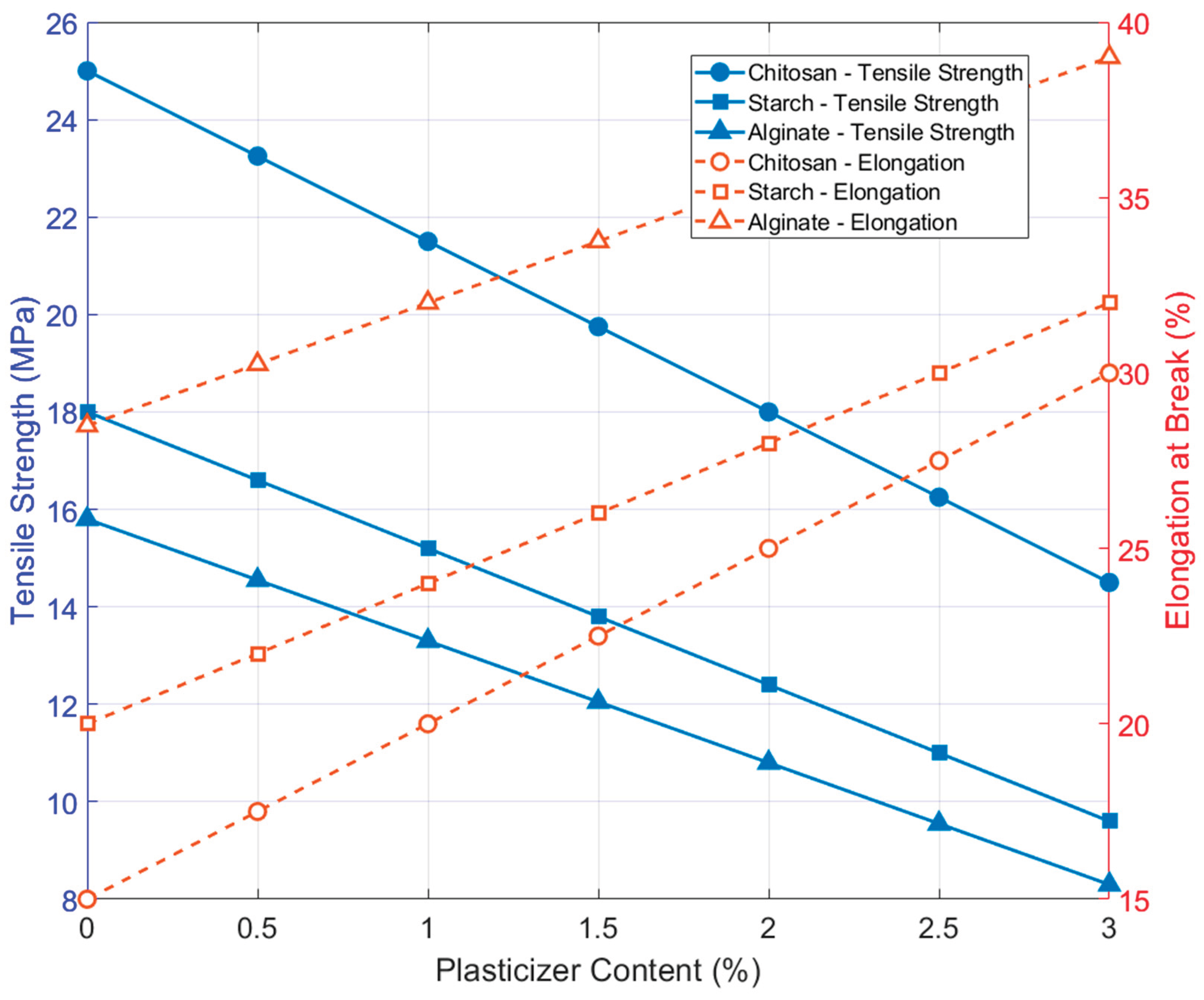

Across literature, tensile strength (TS) and elongation at break (EAB) remain the most consistently reported parameters.

Table 8 summarizes the mechanical properties that are currently available from the studies reviewed here, highlighting both the strengths of existing characterization efforts and the persistent gaps—particularly the near-total absence of stiffness data—within edible-coating research. Starch–carrageenan composite films, for example, display moderate tensile strength (≈15 MPa) and relatively high elongation (≈28%), reflecting a balanced, ductile structure suitable for flexible coatings [

48]. Chitosan-based systems reinforced with bacterial nanocellulose show substantially higher tensile reaching more than 40 MPa at optimal filler loading—accompanied by reduced elongation, indicating a transition toward greater rigidity and reduced ductility [

31]. Cellulose–chitosan blends exhibit tensile strengths in the 12–14 MPa range, illustrating the diversity of mechanical responses achievable through biopolymer blending [

30]. These patterns emphasize how formulation strategies, such as introducing nanofillers or combining polysaccharides, directly shape the mechanical robustness and flexibility of edible films.

In contrast to TS and EAB, Young’s modulus—central to quantifying stiffness and deformation resistance—remains largely absent from edible-coating research. Among the studies surveyed, none reported absolute modulus values, and only a single review summarized modulus changes in relative terms (e.g., an ≈87% increase with cellulose nanocrystal addition) without providing corresponding baseline values [

41]. This omission limits the development of structure–property models and hinders comparison across formulations, even though stiffness plays a crucial role in determining whether coatings crack, resist bending, or maintain integrity on curved, expanding, or mechanically stressed produce surfaces. As edible coatings evolve toward more engineered, multifunctional systems, routine reporting of Young’s modules would significantly enhance analytical and optimization capabilities.

Most mechanical tests follow ASTM D882, which standardizes specimen dimensions and tensile loading procedures for thin films, enabling reproducible reporting of TS and EAB. Nevertheless, relying solely on these two parameters underrepresents the mechanical complexity of edible coatings and constrains our ability to predict real-world performance. Integrating modulus measurement and, where possible, complementary techniques such as nanoindentation or flexural analysis would provide a more complete mechanical profile of coating materials.

Figure 3 illustrates the mechanical trade-offs observed in chitosan-, CNC-reinforced-, and alginate-based edible coatings as plasticizer content increases. All systems show a consistent pattern: tensile strength declines while elongation at break rises. CNC-reinforced films retain higher tensile strength at comparable plasticizer levels, highlighting the structural benefits of nanocrystal incorporation. These trends, drawn from studies using ASTM D882 protocols [

31,

38,

47], underscore the need to balance rigidity and flexibility when designing coatings for produce with varying mechanical sensitivities.

The durability of produce coatings is influenced by their composition, including the type of biopolymer, plasticizers, and additives used. For instance, Tabassum & Khan [

38] demonstrated that incorporating glycerol as a plasticizer in alginate-based coatings increased elongation at break by 30% compared to non-plasticized films, though it slightly reduced tensile strength. This trade-off is critical, as overly rigid coatings may crack under stress, while excessively flexible coatings may fail to provide adequate protection. Coatings with high tensile strength and moderate elongation at break are ideal for produce like apples or tomatoes, which are prone to mechanical damage during bulk handling. Conversely, softer fruits like berries may require coatings with higher flexibility to accommodate surface deformation. Additionally, environmental factors such as humidity and temperature during storage and transport can affect coating performance. Liyanapathiranage et al. [

34]) found that edible coatings maintained higher Young’s modulus values (up to 1.2 GPa) under low-humidity conditions, ensuring better resistance to deformation during long-distance shipping.

4.3.3. Microbiological Efficacy

Microbiological efficacy is a critical factor in evaluating the performance of edible coatings enriched with antimicrobial agents, especially for extending the shelf life and ensuring the safety of perishable produce. Zone-of-inhibition assays are widely used to measure the antimicrobial activity of coatings by observing the clear zones around coated samples where microbial growth is inhibited. Bharti et al. [

48] employed the disc diffusion method (Microan+51) to assess the efficacy of caraway EO-incorporated starch films, reporting significant inhibition zones against B. cereus and S. aureus with zones increasing with higher EO concentrations (e.g., up to 16 mm for B. cereus at 3% EO). Total plate counts quantify viable microbial loads, offering a direct measure of reduction over time, while challenge studies simulate real-world contamination, providing robust efficacy data. Bizymis et al. [

59] achieved a 99% reduction in E. coli within 24 hours using silver nanoparticles, complementing Bharti et al.'s findings on gram-positive bacteria sensitivity. The antimicrobial performance of coatings depends on the type, concentration, and compatibility of the antimicrobial agent with the coating matrix. Bharti et al. [

48] found that caraway EO, rich in cicerain (55.74%) and carvone (8.36%), exhibited greater efficacy against gram-positive bacteria (B. cereus and S. aureus) due to their thinner cell walls, which are more susceptible to phytochemicals, compared to the intrinsic tolerance of gram-negative bacteria (E. coli and P. aeruginosa). This aligns with Bharti et al. [

48] who tested levels of 0.5%, 1%, 2%, and 3% (TC1 to TC4), with higher concentrations showing enhanced inhibition (P<0.01). Environmental factors like temperature and humidity further influence efficacy. For instance, Congying et al. [

44] observed reduced performance of ZnO nanoparticle coatings at higher temperatures Bharti et al. [

48] reported zone-of-inhibition assay results demonstrating clear antimicrobial activity of caraway essential oil (EO)-incorporated starch-based films against Bacillus cereus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus aureus. The study highlighted that gram-positive bacteria exhibited larger inhibition zones as EO concentration increased. For comparison, Bizymis et al. [

59] also presented similar findings when evaluating the efficacy of silver nanoparticles.

4.3.4. Nutritional and Biochemical Analysis

Nutritional and biochemical analysis techniques are critical for assessing the preservative efficacy of edible coatings applied to perishable produce. These methods quantify antioxidant capacity, vitamin and phenolic content, and visual quality attributes, furnishing insight into how coatings mitigate oxidative degradation and nutrient loss during storage. Widely used assays include DPPH and FRAP for antioxidant evaluation, HPLC for micronutrient profiling, and colorimetric methods for monitoring browning and pigment degradation. The DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) and FRAP (Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power) assays are prominent techniques used to measure the antioxidant potential of edible coatings. DPPH evaluates the ability of a sample to scavenge free radicals by observing the decrease in absorbance at 517 nm, while FRAP assesses reducing power through colorimetric change at 593 nm. For example, Bharti et al. [

48] used the DPPH assay to demonstrate that starch-based films enriched with caraway essential oil-maintained antioxidant activity in coated fruit.

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) provides precise quantification of sensitive nutrients such as vitamin C and phenolic compounds. HPLC analyses often use a C18 column and UV detection to identify and quantify key bioactive molecules in fruit samples. Mohammadi et al. [

47] used HPLC to show how chitosan coatings helped retain vitamin C content under cold storage conditions.

Colorimetric tests are also widely applied to monitor enzymatic browning and pigment degradation. Absorbance at 420 nm is typically used for browning index, while chlorophyll and anthocyanin retention are evaluated via spectrophotometric measurements at wavelengths such as 645 nm and 663 nm. Sun et al. [

46] employed such techniques to examine pigment retention in tomato samples coated with chitosan–thyme oil films.

Analytical results are influenced not only by the coating composition but also by sample preparation, solvent selection, and storage conditions. Bharti et al. [

48] extracted phenolic compounds using methanol and noted how higher concentrations of essential oil led to greater inhibition of browning. The barrier properties of the coating, such as thickness and oxygen permeability, also affect the preservation of labile nutrients. Mohammadi et al. [

47] highlighted improved vitamin retention in thicker chitosan layers. Environmental parameters during storage further impact outcomes. Congying et al. (2024) demonstrated that ZnO-enhanced starch coatings preserved anthocyanins better at 4°C compared to ambient conditions, emphasizing the need to pair biochemical tests with storage simulations.

Standardized protocols enhance reproducibility and facilitate cross-study comparisons. AOAC and ISO guidelines often inform method selection. For instance, absorbance-based readings for browning or pigment retention follow standardized wavelength references, and chromatographic methods adhere to validated column and mobile phase parameters. Bharti et al. [

48], Mohammadi et al. [

47], and Sun et al. [

46] all followed such protocols, ensuring scientific rigor.

4.3.5. Sensory Evaluation

Sensory evaluation plays a pivotal role in determining consumer acceptance of coated fresh produce, focusing on attributes such as appearance, taste, aroma, texture, and overall preference. This evaluation relies on structured methodologies to provide objective insights into how coatings influence sensory quality. Trained sensory panels and consumer groups are commonly employed, utilizing tools like hedonic scales and descriptive analysis to systematically assess these attributes. The process involves controlled settings to ensure consistency, with methodologies often aligned with international standards such as those from the International Organization for Standardization (ISO).

Hedonic scales, typically ranging from 1 (dislike extremely) to 9 (like extremely), allow panelists to rate overall liking and individual attributes like taste or appearance. Descriptive analysis, a more detailed technique, involves trained panelists who identify and quantify specific sensory characteristics, such as firmness, aroma intensity, or visual clarity, using standardized lexicons. Memete et al. [

69] utilized both approaches, conducting evaluations over 8 days of refrigerated storage to track changes in sensory properties of coated black mulberries.

The choice of sensory evaluation method depends on the study’s objectives and the coating’s properties. Hedonic scales are ideal for consumer acceptance studies, capturing broad preferences, while descriptive analysis suits detailed profiling of sensory changes over time or across formulations. Environmental factors, such as storage conditions (e.g., refrigerated at 4°C in Memete et al. [

69], and the coating’s thickness or composition influence the sensory attributes assessed, necessitating adjustments in methodology. Sensory evaluation should adhere to standardized guidelines, such as ISO 8589 for panel selection and training, and ISO 4121 for sensory analysis methods. These standards dictate the design of evaluation sessions, including sample preparation (e.g., cutting uniform pieces of coated produce) and presentation order to avoid carryover effects. Memete et al. [

69] likely followed similar protocols, ensuring that assessments of gelatin, oil, and wax coatings were conducted consistently across the 8-day period. Data analysis often incorporates software like FIZZ or Compusense to manage scores and perform statistical tests, ensuring compliance with rigorous scientific practices.

4.3.6. Advanced Structural Analysis

Techniques like scanning electron microscopy (SEM) provide insight into surface uniformity and porosity; FTIR spectroscopy identifies chemical bonding and interactions; and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) assesses thermal stability. These methods enhance understanding of structure–function relationships and support the design of more stable and functional coating systems [

47]. Despite the broad toolkit available, a key research gap remains in standardizing analytical protocols across studies to enable direct comparison of results. Moreover, real-world validation of coating performance under commercial cold chain logistics is still insufficient, and more studies are needed to evaluate behavior under fluctuating temperature and humidity conditions.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is employed to examine the surface morphology, uniformity, and porosity of coatings at a microscopic level. Samples are typically prepared by freeze-drying or gold sputtering to enhance conductivity, followed by imaging under high vacuum at magnifications ranging from 100× to 10,000×. FTIR spectroscopy analyzes chemical bonding and intermolecular interactions by measuring the absorption of infrared light, with spectra recorded over a range of 400–4000 cm⁻¹ using attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) evaluates thermal stability and phase transitions by heating samples (e.g., 0–200°C) at a controlled rate (e.g., 10°C/min), detecting endothermic or exothermic changes. Mohammadi et al. [

47] utilized these techniques to characterize coating structures, providing a foundation for optimizing design parameters.

The choice of structural analysis method depends on the coating’s composition and the property of interest. SEM is ideal for visualizing physical structure, requiring careful sample preparation to avoid artifacts. FTIR suits the study of chemical compatibility, particularly for coatings with polysaccharides or lipids, while DSC is essential for thermal-sensitive materials like protein-based films. Sample size, moisture content, and instrument calibration influence results, necessitating standardized preparation protocols. Environmental conditions during analysis, such as temperature and humidity, also affect outcomes, highlighting the need for controlled settings. Structural analysis follows guidelines from organizations like the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and ASTM International. SEM protocols specify sample mounting and vacuum levels, while FTIR adheres to standards for spectral resolution (e.g., 4 cm⁻¹) and scan numbers (e.g., 32 scans). DSC testing aligns with ISO 11357, detailing heating rates and sample pans. Mohammadi et al. [

47] likely adhered to these standards, though variations in protocols across studies complicate comparisons. Efforts to harmonize methodologies, such as adopting universal sample preparation or data reporting formats, are underway but not yet fully realized.

5. Conclusions

Edible coatings, particularly those based on natural biopolymers, present a promising frontier in sustainable postharvest packaging for fresh produce. Their functional versatility, ranging from moisture and gas barrier properties to microbial suppression and sensory quality preservation, positions them as viable alternatives to synthetic packaging materials in fresh produce supply chains. However, their practical implementation requires a nuanced understanding of material properties, formulation strategies, application techniques, and performance evaluation.

This review highlighted that while considerable progress has been made in developing and applying polysaccharide-, protein-, and lipid-based coatings, several gaps remain in aligning coating functionality with the physiological and logistical demands of postharvest fruit systems. The mechanical integrity, water vapor permeability, and gas transmission characteristics of biopolymer films critically affect their ability to serve as effective packaging surrogates. Techniques such as ASTM D882 for mechanical testing and ASTM E96/E96M for WVP remain essential benchmarks for characterizing these materials. Furthermore, the plasticizing effect of moisture within hydrophilic matrices continues to compromise coating performance and warrants more targeted research into barrier enhancement via nanostructuring, hydrophobic modification, or multilayer systems.

Importantly, edible coatings not only serve as passive barriers but can actively modulate the fruit’s internal atmosphere, potentially replicating or enhancing the microenvironmental benefits of modified atmosphere packaging. Yet, the interplay between coating properties and fruit physiology remains insufficiently explored, particularly under commercial handling conditions. Future studies must bridge this gap by integrating advanced material characterization with physiological monitoring and shelf-life assessments under real-world scenarios.

In conclusion, optimizing edible coatings for fresh produce preservation requires a holistic approach that balances material innovation, application scalability, and postharvest efficacy. Advancing this field will depend on interdisciplinary collaboration across food science, material engineering, and postharvest technology, supported by standardized evaluation protocols and regulatory clarity. With such efforts, edible coating could transition from niche innovation to mainstream application in sustainable fresh produce logistics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.T, U.L.O.; writing—original draft preparation, S.O.J and A.A.T; writing—review and editing, A.A.T., R.L., E.C.; supervision, A.A.T.; project administration, A.A.T.; funding acquisition, A.A.T. and U.L.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is based on the research supported wholly/in part by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant No. 64813). U.L.O. is grateful for this funding under SARChI Postharvest Technology.

Data Availability Statement

This review is based on previously published studies and does not include new experimental data. All sources referenced are publicly available and cited accordingly. Further information can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This work is based on the research supported wholly/in part by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant No. 64813). ULO is grateful for this funding under SARChI Postharvest Technology. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed are those of the authors alone, and the NRF accepts no liability whatsoever in this regard. Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research under award number 434—grant ID: DFs-18-0000000008.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Miranda, M.; Bai, J.; Pilon, L.; Torres, R.; Casals, C.; Solsona, C.; Teixidó, N. Fundamentals of Edible Coatings and Combination with Biocontrol Agents: A Strategy to Improve Postharvest Fruit Preservation. Foods 2024, 13, 2980. [CrossRef]

- Ambaw, A.; Fadiji, T.; Opara, U.L. Thermo-Mechanical Analysis in the Fresh Fruit Cold Chain: A Review on Recent Advances. Foods 2021, 10, 1357. [CrossRef]

- Berry, T.M.; Defraeye, T.; Shrivastava, C.; Ambaw, A.; Coetzee, C.; Opara, U.L. Designing ventilated packaging for the fresh produce cold chain. Food Bioprod. Process. 2022, 134, 121–149. [CrossRef]

- Lufu, R.; Ambaw, A.; Opara, U.L. The Influence of Internal Packaging (Liners) on Moisture Dynamics and Physical and Physiological Quality of Pomegranate Fruit during Cold Storage. Foods 2021, 10, 1388. [CrossRef]

- Ambaw, A.; Fadiji, T.; Opara, U.L. Thermo-Mechanical Analysis in the Fresh Fruit Cold Chain: A Review on Recent Advances. Foods 2021, 10, 1357. [CrossRef]

- Berry, T.M.; Smith, J.; Johnson, R. Novel packaging designs to improve floor area utilization in reefers. J Food Eng, 2022, 150, 45–53.

- Berry, T.M.; Defraeye, T.; Shrivastava, C.; Ambaw, A.; Coetzee, C.; Opara, U.L. Designing ventilated packaging for the fresh produce cold chain. Food Bioprod. Process. 2022, 134, 121–149. [CrossRef]

- Lufu, R.; Ambaw, A.; Opara, U.L. Functional characterisation of lenticels, micro-cracks, wax patterns, peel tissue fractions and water loss of pomegranate fruit (cv. Wonderful) during storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 178. [CrossRef]

- Pathare, P.B.; Opara, U.L. Mechanical Damage in Fresh Horticultural Produce: Measurement, Analysis and Control; Pathare, P.B.; Opara, U.L., Eds.; 1st ed.; Springer Nature, Singapore, 2023.

- Al-Dairi, M.; Pathare, P.B.; Al-Yahyai, R.; Opara, U.L. Mechanical damage of fresh produce in postharvest transportation: Current status and future prospects. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 124, 195–207. [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Fawole, O.A.; Saeys, W.; Wu, D.; Wang, J.; Opara, U.L.; Nicolai, B.; Chen, K. Mechanical damages and packaging methods along the fresh fruit supply chain: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 63, 10283–10302. [CrossRef]

- Opara, U.L.; Pathare, P.B. Bruise damage measurement and analysis of fresh horticultural produce—A review. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2014, 91, 9–24. [CrossRef]

- Lufu, R.; Ambaw, A.; Opara, U.L. Mechanisms and modelling approaches to weight loss in fresh fruit: a review. Technol. Hortic. 2024, 4. [CrossRef]

- Lufu, R.; Ambaw, A.; Opara, U.L. Assessing weight loss control strategies in pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) fruit: plastic packaging and surface waxing. Sustain. Food Technol. 2023, 2, 175–188. [CrossRef]

- Lufu, R.; Ambaw, A.; Opara, U.L. Water loss of fresh fruit: Influencing pre-harvest, harvest and postharvest factors. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 272. [CrossRef]

- Caleb, O.J.; Opara, U.L.; Witthuhn, C.R. Modified Atmosphere Packaging of Pomegranate Fruit and Arils: A Review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2011, 5, 15–30. [CrossRef]

- Lufu, R.; Ambaw, A.; Opara, U.L. The Influence of Internal Packaging (Liners) on Moisture Dynamics and Physical and Physiological Quality of Pomegranate Fruit during Cold Storage. Foods 2021, 10, 1388. [CrossRef]

- González-López, M.E.; Calva-Estrada, S.d.J.; Gradilla-Hernández, M.S.; Barajas-Álvarez, P. Current trends in biopolymers for food packaging: a review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1225371. [CrossRef]

- Operato, L.; Panzeri, A.; Masoero, G.; Gallo, A.; Gomes, L.C.; Hamd, W. Food packaging use and post-consumer plastic waste management: a comprehensive review. Front. Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 5, 1520532. [CrossRef]

- Riva, S.C.; Opara, U.O.; Fawole, O.A. Recent developments on postharvest application of edible coatings on stone fruit: A review. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 262. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Montes, E.; Castro-Muñoz, R. Edible Films and Coatings as Food-Quality Preservers: An Overview. Foods 2021, 10, 249. [CrossRef]

- Orhotohwo, O.L.; Lucci, P.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Jaiswal, S.; Pacetti, D. Enhancing the functional properties of chitosan-alginate edible films using spent coffee ground extract for fresh-cut fruit preservation. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2025, 11, 101124. [CrossRef]

- Kawhena, T.G.; Tsige, A.A.; Opara, U.L.; Fawole, O.A. Application of Gum Arabic and Methyl Cellulose Coatings Enriched with Thyme Oil to Maintain Quality and Extend Shelf Life of “Acco” Pomegranate Arils. Plants 2020, 9, 1690. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, V.; Singh, S.; Das, D. Environmental Impact Assessment of Active Biocomposite Packaging and Comparison with Conventional Packaging for Food Application.DS 130. In Proceedings of NordDesign 2024; Reykjavik, Iceland, 2024; pp. 402–410.

- Ali, M.; Ali, A.; Ali, S.; Chen, H.; Wu, W.; Liu, R.; Chen, H.; Ahmed, Z.F.R.; Gao, H. Global insights and advances in edible coatings or films toward quality maintenance and reduced postharvest losses of fruit and vegetables: An updated review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70103. [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.; Marcet, I.; Rendueles, M.; Díaz, M. Edible Films from the Laboratory to Industry: A Review of the Different Production Methods. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2024, 18, 3245–3271. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, I.; Pinto, T.; Afonso, S.; Karaś, M.; Szymanowska, U.; Gonçalves, B.; Vilela, A. Sustainability in Bio-Based Edible Films, Coatings, and Packaging for Small Fruits. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1462. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Lall, A.; Kumar, S.; Patil, T.D.; Gaikwad, K.K. Plant-based edible films and coatings for food-packaging applications: recent advances, applications, and trends. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 1428–1455. [CrossRef]

- Valdés, A.; Ramos, M.; Beltrán, A.; Jiménez, A.; Garrigós, M.C. State of the Art of Antimicrobial Edible Coatings for Food Packaging Applications. Coatings 2017, 7, 56. [CrossRef]

- Hailu, F.W.; Fanta, S.W.; Tsige, A.A.; Delele, M.A. Development of simple and biodegradable pH indicator films from cellulose and anthocyanin. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Pirozzi, A.; Ferrari, G.; Donsì, F. The Use of Nanocellulose in Edible Coatings for Preservation of Strawberries. Coatings, 2021, 11, 990.

- Filho, J.G.d.O.; Miranda, M.; Ferreira, M.D.; Plotto, A. Nanoemulsions as Edible Coatings: A Potential Strategy for Fresh Fruits and Vegetables Preservation. Foods 2021, 10, 2438. [CrossRef]

- González-Cuello, R.; Parada-Castro, A.L.; Ortega-Toro, R. Application of a Multi-Component Composite Edible Coating for the Preservation of Strawberry Fruit. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 515. [CrossRef]

- Liyanapathiranage, A.; Dassanayake, R.S.; Gamage, A.; Karri, R.R.; Manamperi, A.; Evon, P.; Jayakodi, Y.; Madhujith, T.; Merah, O. Recent Developments in Edible Films and Coatings for Fruits and Vegetables. Coatings 2023, 13, 1177. [CrossRef]

- Miteluț, A.C.; Popa, E.E.; Drăghici, M.C.; Popescu, P.A.; Popa, V.I.; Bujor, O.-C.; Ion, V.A.; Popa, M.E. Latest Developments in Edible Coatings on Minimally Processed Fruits and Vegetables: A Review. Foods 2021, 10, 2821. [CrossRef]

- Wigati, L.; Wardana, A.; Nkede, F.; Fanze, M.; Wardak, M.; Kavindi, M.R.; Van, T.; Yan, X.; Tanaka, F.; Tanaka, F. Influence of cellulose nanocrystal formulations on the properties of pregelatinized cornstarch and cornmint essential oil films. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wall, M.; Follett, P.; Liang, P.; Xu, S.; Zhong, T. Effect of Pectin Coatings Containing Trans-cinnamaldehyde on the Postharvest Quality of Rambutan. HortScience 2023, 58, 11–15. [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, N.; Khan, M.A. Modified atmosphere packaging of fresh-cut papaya using alginate based edible coating: Quality evaluation and shelf life study. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 259. [CrossRef]

- Popescu, P.-A.; Palade, L.M.; Nicolae, I.-C.; Popa, E.E.; Miteluț, A.C.; Drăghici, M.C.; Matei, F.; Popa, M.E. Chitosan-Based Edible Coatings Containing Essential Oils to Preserve the Shelf Life and Postharvest Quality Parameters of Organic Strawberries and Apples during Cold Storage. Foods 2022, 11, 3317. [CrossRef]

- Odetayo, T.; Sithole, L.; Shezi, S.; Nomngongo, P.; Tesfay, S.; Ngobese, N.Z. Effect of nanoparticle-enriched coatings on the shelf life of Cavendish bananas. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 304. [CrossRef]

- Pirozzi, A.; Pierro, P.; Mariniello, L. Effect of Cellulose Nanocrystals on Mechanical and Barrier Properties of Chitosan-Based Edible Films for Fruit Coating. Polymers (Basel), 2021, 13, 241.

- Mohammadi, M.; Rastegar, S.; Rohani, A. Enhancing Mexican lime (Citrus aurantifolia cv.) shelf life with innovative edible coatings: xanthan gum edible coating enriched with Spirulina platensis and pomegranate seed oils. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Resende, N.S.; Gonçalves, G.A.S.; Reis, K.C.; Tonoli, G.H.D.; Boas, E.V.B.V. Chitosan/Cellulose Nanofibril Nanocomposite and Its Effect on Quality of Coated Strawberries. J. Food Qual. 2018, 2018, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Congying, H.; Meifang, W.; Islam, N.; Cancan, S.; Shengli, G.; Hossain, A.; Xiaohuang, C. Cassava Starch-Based Multifunctional Coating Incorporated with Zinc Oxide Nanoparticle to Enhance the Shelf Life of Passion Fruit. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2024, 2024, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Bharti, S.K.; Pathak, V.; Alam, T.; Arya, A.; Singh, V.K.; Verma, A.K.; Rajkumar, V. Starch bio-based composite active edible film functionalized with Carum carvi L. essential oil: antimicrobial, rheological, physic-mechanical and optical attributes. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 59, 456–466. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Pan, X.; Wang, T.; Liu, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, X. Preparation, characterization and application of chitosan/thyme essential oil composite film. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Rastegar, S.; Rohani, A. Enhancing Mexican lime (Citrus aurantifolia cv.) shelf life with innovative edible coatings: xanthan gum edible coating enriched with Spirulina platensis and pomegranate seed oils. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Bharti, S.K.; Pathak, V.; Alam, T.; Arya, A.; Singh, V.K.; Verma, A.K.; Rajkumar, V. Starch bio-based composite active edible film functionalized with Carum carvi L. essential oil: antimicrobial, rheological, physic-mechanical and optical attributes. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 59, 456–466. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Shayan, M.; Gwon, J.; Picha, D.H.; Wu, Q. Effectiveness of cellulose and chitosan nanomaterial coatings with essential oil on postharvest strawberry quality. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 298, 120101. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Pratibha; Prasad, J.; Yadav, A.; Upadhyay, A.; Neeraj; Shukla, S.; Petkoska, A.T.; Heena; Suri, S.; et al. Recent Trends in Edible Packaging for Food Applications — Perspective for the Future. Food Eng. Rev. 2023, 15, 718–747. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Yang, F.; Yu, H.; Yao, W.; Xie, Y. Controllable Fabrication of Edible Coatings to Improve the Match Between Barrier and Fruits Respiration Through Layer-by-Layer Assembly. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2022, 15, 1778–1793. [CrossRef]

- Karimi Dehbakri, N.; Akbarzadeh, A.; Ebrahimi, S. Effect of Nanocellulose Coating Enriched with Myrtle Essential Oil on Postharvest Quality of Strawberry during Cold Storage. BMC Plant Biol, 2025, 25, Article 675.

- Márquez-Villacorta, L.; Pretell-Vásquez, C.; Hayayumi-Valdivia, M. Optimization of edible coating with essential oils in blueberries. Cienc. E Agrotecnologia 2022, 46. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Pan, X.; Wang, T.; Liu, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, X. Preparation, characterization and application of chitosan/thyme essential oil composite film. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Bashir, O.; Amin, T.; Hussain, S.Z.; Naik, H.; Goksen, G.; Wani, A.W.; Manzoor, S.; Malik, A.; Wani, F.J.; Proestos, C. Development, characterization and use of rosemary essential oil loaded water-chestnut starch based nanoemulsion coatings for enhancing post-harvest quality of apples var. Golden delicious. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 7, 100570. [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Q.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, F. Multifunctional sodium alginate-based self-healing edible cross-linked coating for banana preservation. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 151. [CrossRef]

- Sarengaowa, W.; L., L.; Y., Y.; C., F.; K.; Hu, W. Screening of Essential Oils and Effect of a Chitosan-Based Edible Coating Containing Cinnamon Oil on the Quality and Microbial Safety of Fresh-Cut Potatoes. Coatings, 2022, 12, 1492.

- Vidyarthi, E.V.; Thakur, M.; Khela, R.K.; Roy, S. Edible coatings for fresh produce: exploring chitosan, beeswax, and essential oils in green chillies and pointed gourd. Food Mater. Res. 2024, 4. [CrossRef]

- Bizymis, A.-P.; Kalantzi, S.; Mamma, D.; Tzia, C. Addition of Silver Nanoparticles to Composite Edible Films and Coatings to Enhance Their Antimicrobial Activity and Application to Cherry Preservation. Foods 2023, 12, 4295. [CrossRef]

- Kawhena, T.G.; Opara, U.L.; Fawole, O.A. Optimization of Gum Arabic and Starch-Based Edible Coatings with Lemongrass Oil Using Response Surface Methodology for Improving Postharvest Quality of Whole “Wonderful” Pomegranate Fruit. Coatings 2021, 11, 442. [CrossRef]

- Babarabie, M.; Sardoei, A.S.; Jamali, B.; Hatami, M. Carnauba wax-based edible coatings retain quality enhancement of orange (Citrus sinensis cv. Moro) fruits during storage. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Mantilla, N. Development of an Alginate-Based Antimicrobial Edible Coating to Extend the Shelf-Life of Fresh-Cut Pineapple, 2012.

- Bajaj, K.; Kumar, A.; Gill, P.; Jawandha, S.; Kaur, N. Xanthan gum coatings augmented with lemongrass oil preserve postharvest quality and antioxidant defence system of Kinnow fruit under low-temperature storage. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 262, 129776. [CrossRef]

- Vimala Bharathi, S.K.; Maria Leena, M.; Moses, J.A.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Zein-Based Anti-Browning Cling Wraps for Fresh-Cut Apple Slices. Int J Food Sci Technol, 2020, 55, 1238–1245.

- Siringul, K.; Aminah, A. Effects of seaweed (Kappaphycus alvarezii) based edible coating on quality and shelf life of minimally processed mango (Mangifera indica L. king). Food Res. 2023, 7, 262–271. [CrossRef]

- Dulta, K.; Ağçeli, G.K.; Thakur, A.; Singh, S.; Chauhan, P.; Chauhan, P.K. Development of Alginate-Chitosan Based Coating Enriched with ZnO Nanoparticles for Increasing the Shelf Life of Orange Fruits (Citrus sinensis L.). J. Polym. Environ. 2022, 30, 3293–3306. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-L.; Cui, Q.-L.; Wang, Y.; Shi, F.; Fan, H.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Lai, S.-T.; Li, Z.-H.; Li, L.; Sun, Y.-K. Effect of Edible Carboxymethyl Chitosan-Gelatin Based Coating on the Quality and Nutritional Properties of Different Sweet Cherry Cultivars during Postharvest Storage. Coatings 2021, 11, 396. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Yusof, N.M.; Jai, J.; Hamzah, F. Effect of Coating Adhesion on Turmeric Essential Oil Incorporated into Chitosan-Based Edible Coating. Mater. Sci. Forum 2017, 890, 204–208. [CrossRef]