Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

01 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Model and Method

3. Results

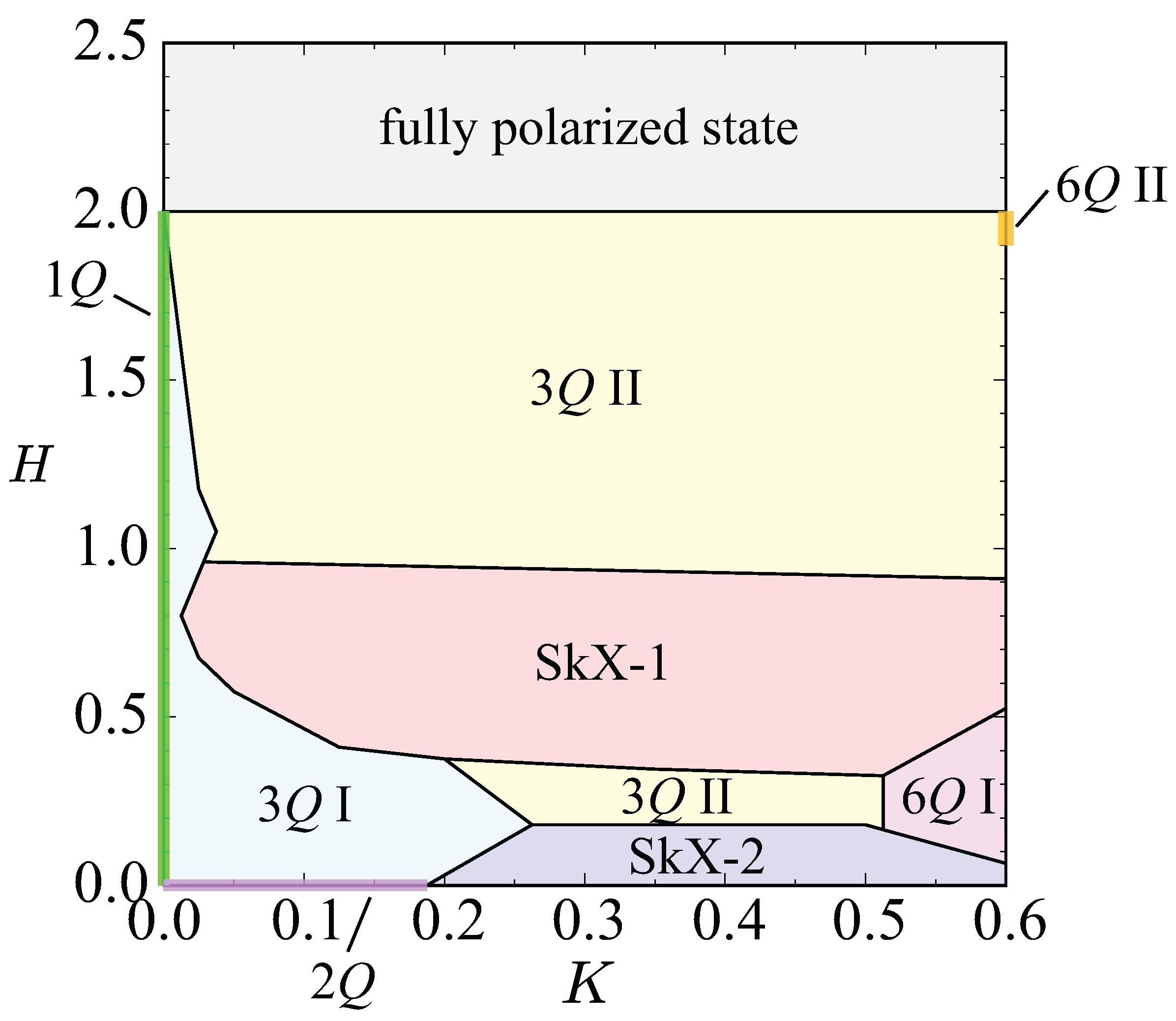

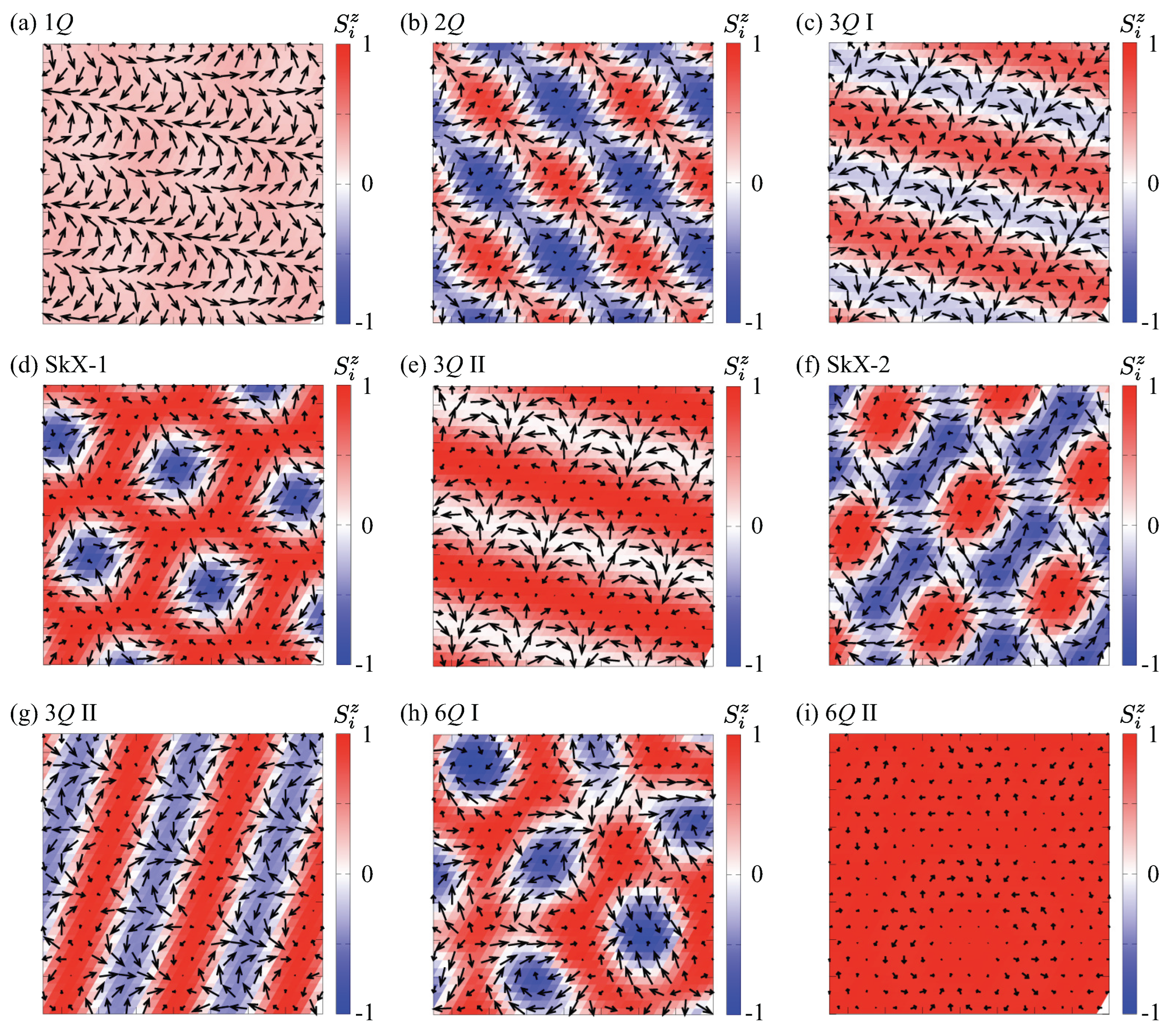

- Single-Q (1Q) state. At , the bilinear exchange interaction alone stabilizes a single-Q spiral configuration. The spin structure factor exhibits a pair of sharp peaks at one of the symmetry-related ordering wave vectors, reflecting a spiral modulation in a single direction. The corresponding real-space spin texture forms a coplanar spiral without amplitude modulation at zero magnetic field, as shown in Figure 3(a), and thus both local and uniform scalar spin chiralities vanish, . When an external magnetic field is applied, the spiral plane is locked within the plane to maximize the Zeeman energy gain. The spins are uniformly canted toward the field direction, acquiring a finite out-of-plane component. This canting introduces a locally nonzero scalar spin chirality owing to the slight noncoplanarity of neighboring spins. However, because the scalar spin chirality alternates for upward and downward triangle plaquettes, its spatial average cancels out, leaving the phase topologically trivial with . The single-Q state forms the basic reference from which multiple-Q states develop with increasing K.

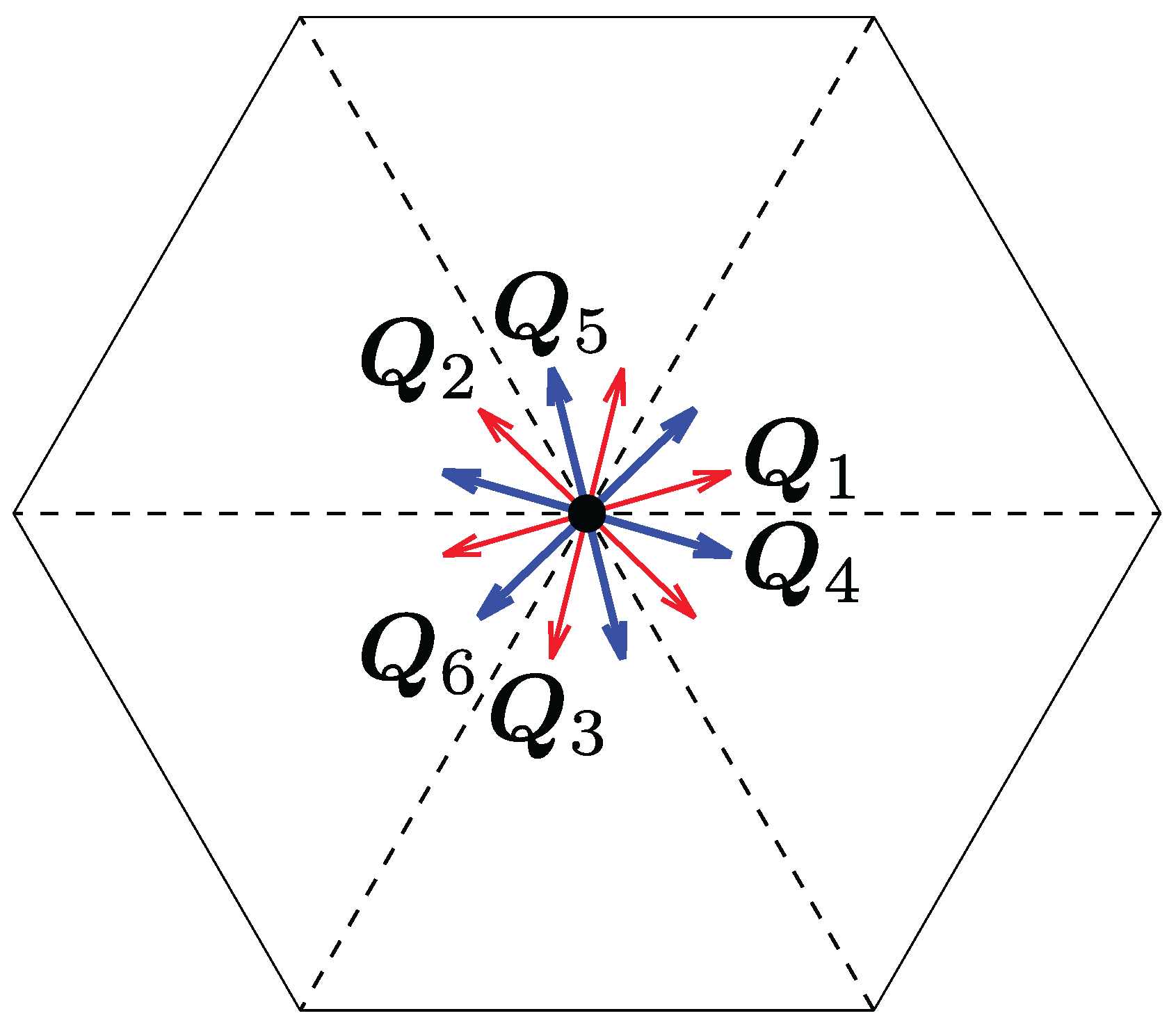

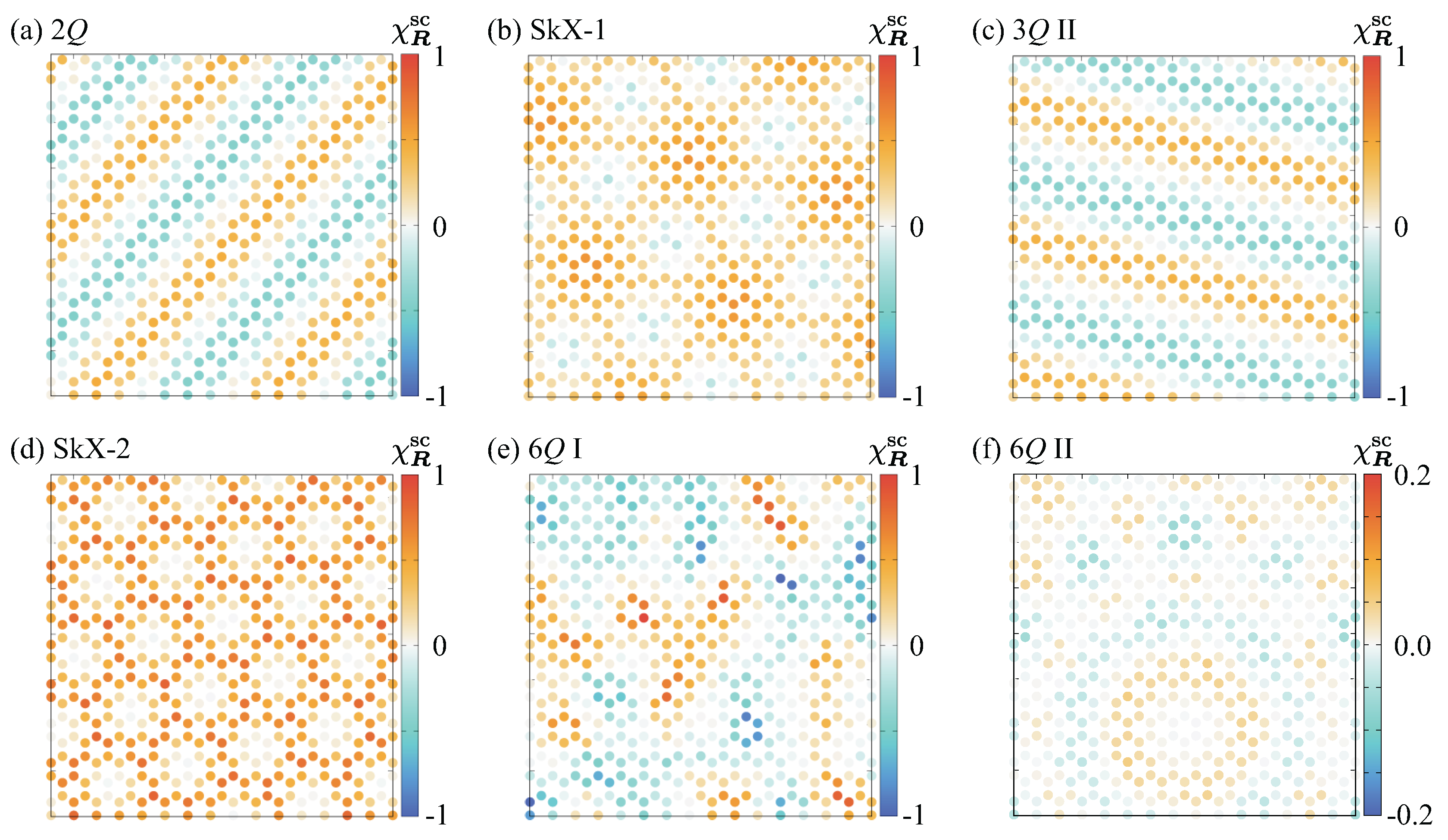

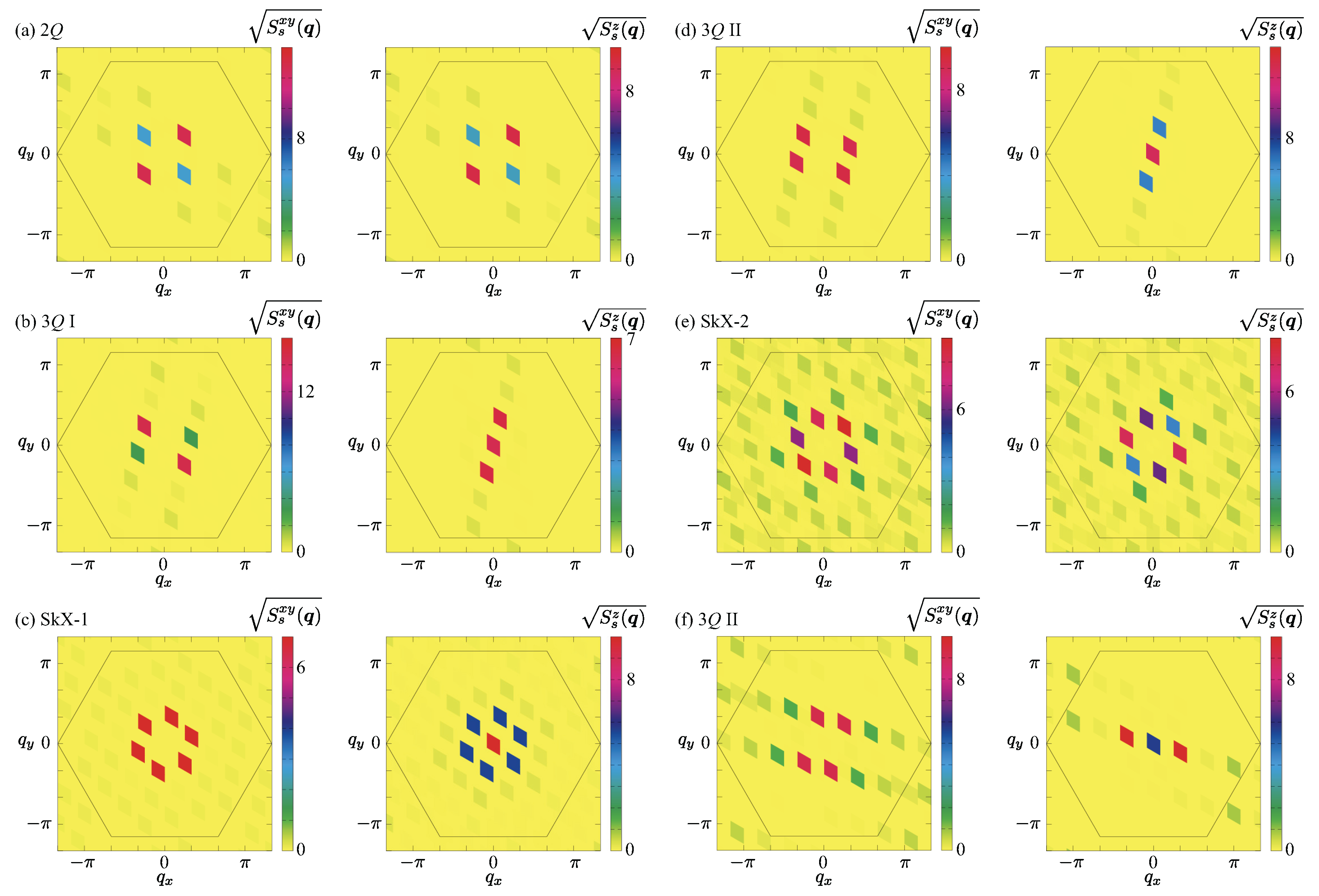

- Double-Q (2Q) state. With the introduction of K at zero magnetic field, interference between two symmetry-related ordering wave vectors becomes energetically favorable, stabilizing a double-Q state [111]. The real-space spin texture in Figure 3(b) exhibits a noncoplanar configuration arising from the superposition of a spiral wave at the primary ordering wave vector and a sinusoidal modulation at the secondary one. This superposition induces a finite local scalar spin chirality whose sign alternates spatially, resulting in no net uniform component (), as visualized in the local scalar spin chirality distribution in Figure 4(a). In reciprocal space, the spin structure factor shows four dominant peaks corresponding to two of the six ordering wave vectors, with unequal intensities in both in-plane and out-of-plane components, signaling the emergence of an anisotropic double-Q state, as shown in Figure 5(a). The spin configuration of this state continuously evolves into the single-Q spiral state by suppressing the modulation at the secondary wave vector, i.e., by decreasing K. Thus, the double-Q phase represents a noncoplanar, topologically trivial extension of the single-Q spiral state, serving as an intermediate state preceding the formation of the triple-Q spin configuration at larger K.

- Triple-Q I (3Q I) state. Upon further increasing K in the single-Q state at , or increasing H in the double-Q state at , the interference among the three symmetry-related ordering wave vectors, , , and (or , , and ), becomes nearly balanced, leading to the stabilization of the triple-Q I phase. In real space, the spin configuration retains a resemblance to that of the double-Q state, exhibiting a noncoplanar texture as shown in Figure 3(c). This noncoplanarity locally induces scalar spin chirality, similar to the double-Q state; however, the alternating sign of the local scalar spin chirality results in a vanishing uniform component (), indicating that the state remains topologically trivial. In reciprocal space, the spin structure factor exhibits six dominant peaks corresponding to , , and , as shown in Figure 5(b). The in-plane component shows double-Q-type peaks, whereas the out-of-plane component retains a single-Q feature, reflecting an anisotropic triple-Q superposition. The corresponding Fourier amplitudes satisfy , confirming the unequal contributions from the three ordering wave vectors.

- SkX with the skyrmion number of one (SkX-1). Upon further increasing H in the triple-Q I state, the system undergoes a phase transition into the SkX phase with a skyrmion number of one (SkX-1). In real space, the spin texture in Figure 3(d) reveals a well-ordered triangular lattice of skyrmions, each containing a single topological winding within the magnetic unit cell. The in-plane spin components form a vortex-like swirling pattern around the skyrmion cores, while the out-of-plane components alternate between pointing downward at the cores and upward in the interstitial regions. This continuous twisting of spins ensures that all local spin triads acquire finite scalar spin chirality with almost the same sign, resulting in a uniform positive . The local scalar spin chirality distribution shown in Figure 4(b) confirms this feature, exhibiting strongly positive values at the skyrmion cores and only weak residual modulation between them. It is noted that the SkX with the negative scalar spin chirality (skyrmion number) is energetically degenerate with the SkX with the positive one owing to the absence of magnetic anisotropy [112]. The helicity of the skyrmion is also undetermined owing to the spin rotational symmetry of the model [113]. In reciprocal space, the spin structure factor displays a sixfold-symmetric pattern originating from the coherent superposition of the fundamental components at (–3), as shown in Figure 5(c). The equal intensities of the six primary peaks reflect the full restoration of threefold rotational symmetry, in contrast to the anisotropic triple-Q I phase.

- Triple-Q II (3Q II) state. The triple-Q II phase emerges upon increasing H from the SkX-1 phase. This state is characterized by triple-Q peaks located at , , and (or , , and ), whose relative amplitudes differ from those in the triple-Q I state. In the triple-Q II phase, the in-plane component of the spin structure factor exhibits equal intensities at the double-Q ordering wave vectors, as shown in Figure 5(d), whereas these intensities are unequal in the triple-Q I state [Figure 5(b)]. Such a subtle rearrangement of the amplitude balance and phase relation results in a real-space spin configuration similar to that of the triple-Q I phase, as illustrated in Figure 3(e), which exhibits a noncoplanar texture. The local scalar spin chirality distribution shown in Figure 4(c) confirms this behavior: the scalar spin chirality alternates in sign across real space, yielding no net uniform component (). A similar triple-Q II configuration also appears between the SkX-1 and SkX-2 phases, whose real-space spin arrangement and corresponding spin structure factor are presented in Figure 3(g) and Figure 5(f), respectively.

- SkX with the skyrmion number of two (SkX-2). For larger K at zero magnetic field, the system stabilizes another SkX phase with a skyrmion number of two per magnetic unit cell, referred to as SkX-2. This phase arises from the coherent superposition of triple-Q sinusoidal waves at , , and (or , , and ), whose amplitudes are equivalent but whose relative phases are arranged so as to produce a double-winding topological structure within each skyrmion core. The resulting spin configuration in Figure 3(f) exhibits a well-ordered triangular lattice of doubly wound skyrmions. Each skyrmion core undergoes two full rotations of the spin direction, forming a tightly twisted configuration with out-of-plane spin polarization at the core center and nearly in-plane spin alignment in the surrounding region. The in-plane spin components form vortex-like patterns that rotate twice around each core compared with SkX-1, giving rise to a more intricate twisting of the spin texture. The local scalar spin chirality distribution in Figure 4(d) highlights intense positive scalar spin chirality concentrated at the skyrmion cores, consistent with the double-winding nature. Consequently, the uniform scalar spin chirality becomes larger than that in SkX-1, reflecting the increased topological charge density. In reciprocal space, the total spin structure factor maintains a sixfold-symmetric pattern at , , and , as shown in Figure 5(e), similar to that of SkX-1. The intensities of the spin structure factors for the in-plane () and out-of-plane (z) components appear to differ, but their sums are equivalent owing to the spin rotational symmetry in the absence of the magnetic field. A similar SkX has been reported in both the Kondo lattice model [114,115,116] and the square-lattice spin model [117,118].

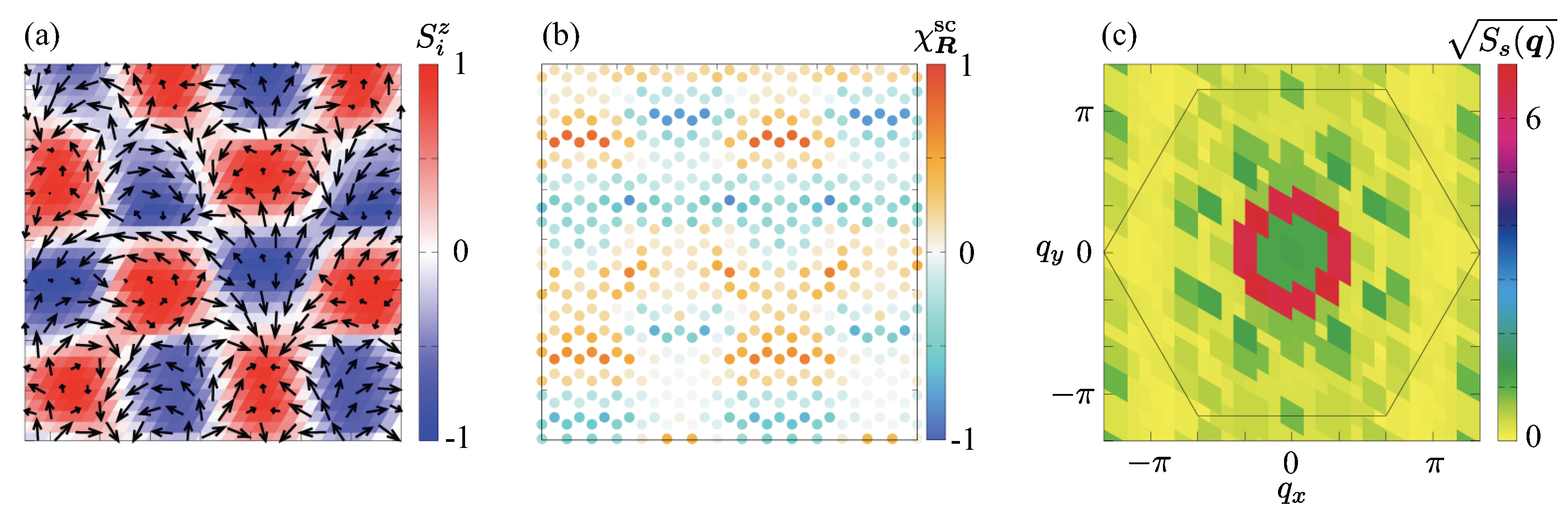

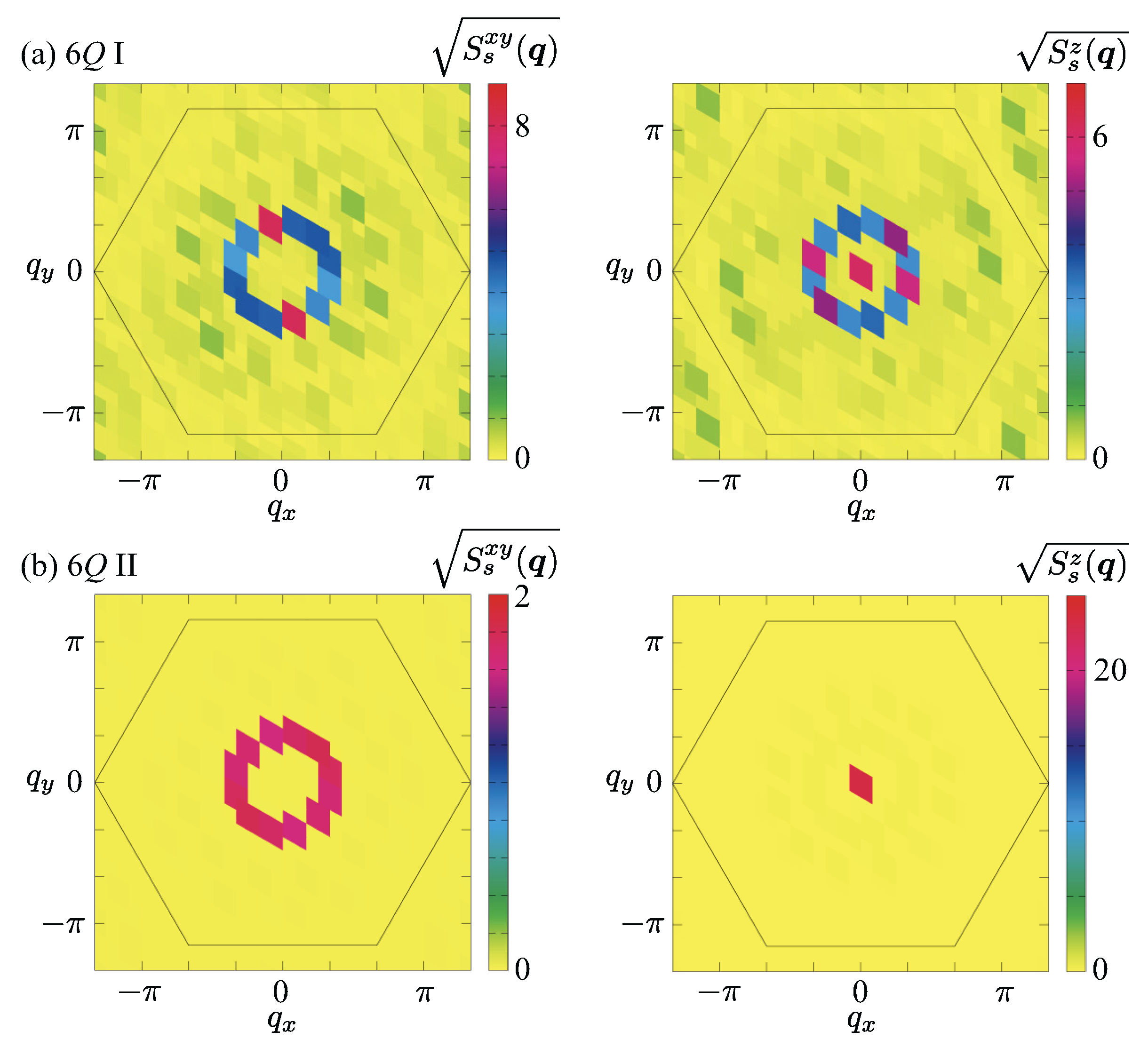

- Sextuple-Q I (6Q I) phase. For sufficiently large K at intermediate magnetic fields, the system undergoes a remarkable transition into a sextuple-Q state, referred to as the 6Q I phase, in which all six symmetry-related ordering wave vectors (–6) participate coherently. This phase constitutes one of the main findings of the present study, representing a novel type of multiple-Q magnetic order that originates from the interference among symmetry equivalent ordering wave vectors located at low-symmetry positions inherent to the hexagonal lattice. In real space, the spin configuration shown in Figure 3(h) exhibits a densely modulated spin texture that can be well described as a coherent superposition of six spin density waves. Both the in-plane and out-of-plane spin components contribute to an intricate interference pattern; in contrast to the SkX phases, the spin texture contains skyrmion and anti-skyrmion cores, forming a globally noncoplanar but topologically neutral structure. As illustrated in Figure 4(e), the local scalar spin chirality alternates in sign across the lattice, forming a multiple-Q chirality density wave. Consequently, the uniform component of the scalar spin chirality vanishes (), consistent with the topologically trivial nature of this state. The spin structure factor in reciprocal space displays six inequivalent Bragg peaks forming a slightly distorted hexagonal pattern, as shown in Figure 6(a), indicating coherent but anisotropic interference among all six components.

- Sextuple-Q II (6Q II) phase. At higher magnetic fields and deeper in the large-K regime, the system further evolves into another sextuple-Q state, denoted as the 6Q II phase. In real space, the spin configuration shown in Figure 3(i) exhibits a noncoplanar texture in which the in-plane spin components form vortex-like patterns, while the out-of-plane component becomes nearly uniform. Compared with the sextuple-Q I phase, the modulation amplitude of the spin texture is reduced, leading to a smoother spatial variation. As shown in Figure 4(f), this state also hosts a complex scalar spin chirality density wave without a uniform component, indicating that it remains topologically trivial despite the multiple-Q interference. In reciprocal space, the in-plane spin structure factor in Figure 6(b) displays six nearly equivalent peaks forming a regular hexagon, in contrast to the slightly distorted pattern found in the sextuple-Q I phase. This suggests a reorganization of the phase relations among the six ordering wave-vector components, which results in the partial suppression of the scalar spin chirality modulation in real space.

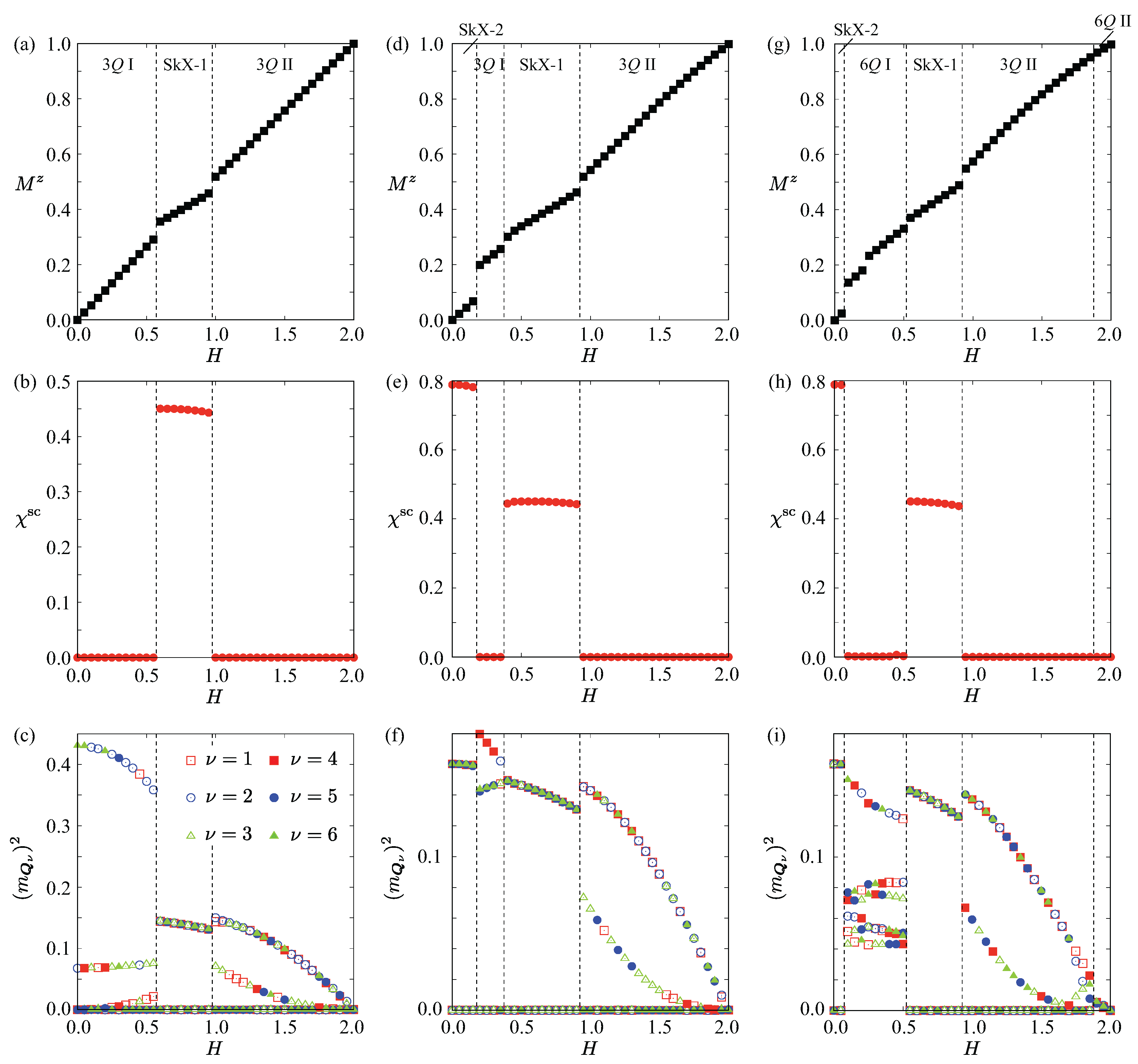

- Nature of phase transitions. The sequence of magnetic phases with increasing magnetic field H and biquadratic coupling K reveals a hierarchical buildup of multiple-Q order and distinct types of phase transitions between them, as summarized in Figure 7. The successive activation of symmetry-related ordering-wave-vector components from one in the single-Q state to two in the double-Q state, three in the triple-Q state and the SkX, and six in the sextuple-Q state is quantitatively reflected in the evolution of the Fourier amplitudes , as shown in Figure 7(c), Figure 7(f), and Figure 7(i). These changes correlate closely with discontinuities or crossovers in the magnetization as a function of H or K.

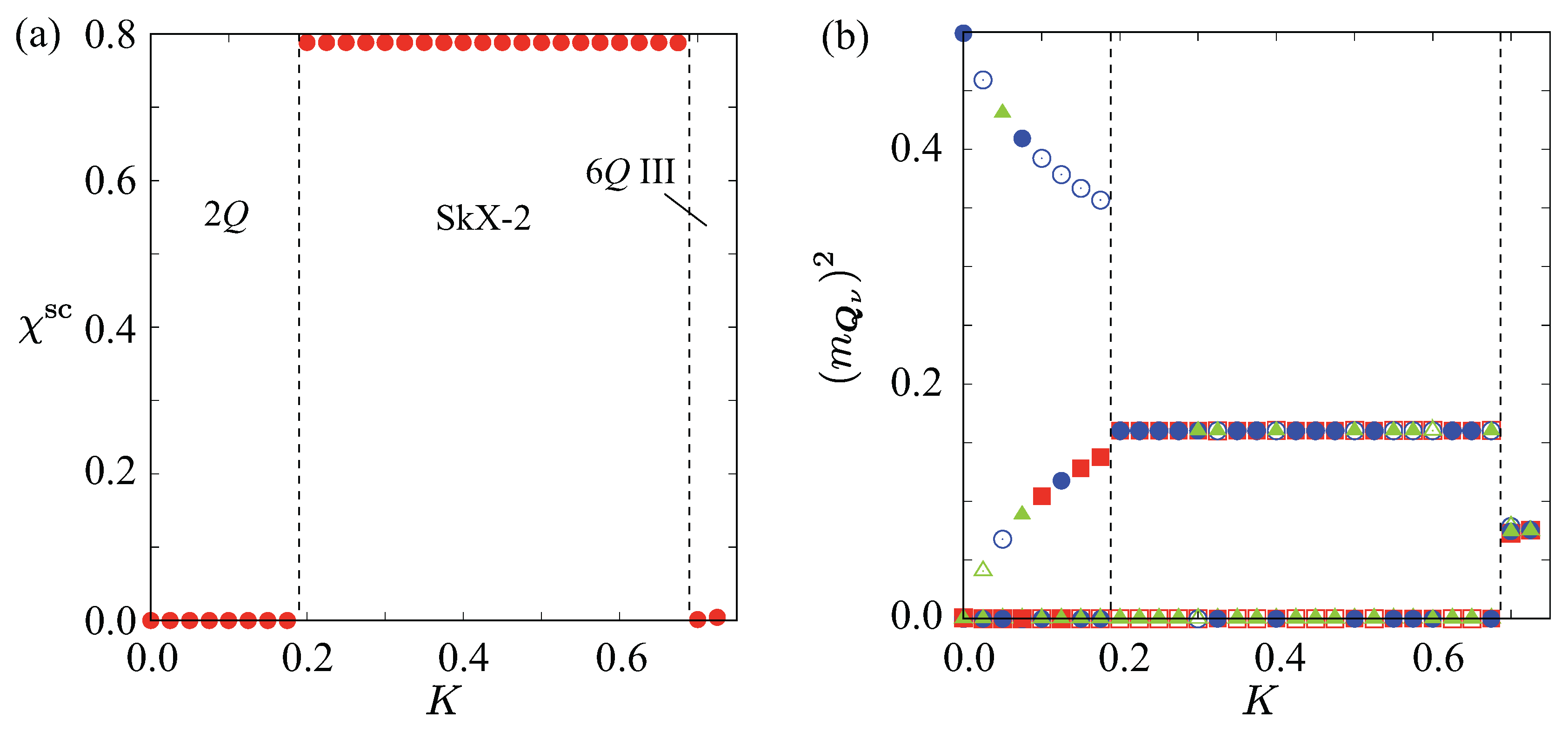

- Zero-field sextuple-Q state. To further clarify the role of the biquadratic interaction K in the absence of a magnetic field, we examine the zero-field () spin configurations for various values of K, as summarized in Figure 8(a) and Figure 8(b). For , the ground state is a single-Q state characterized by a single dominant peak in the spin structure factor, as shown in Figure 8(b). As K increases, interference among symmetry-related ordering wave vectors becomes energetically favorable, leading successively to the double-Q and triple-Q SkX-2 states. When K is further enhanced, all six ordering wave-vector components (–6) coherently participate, resulting in the stabilization of a new zero-field phase, the sextuple-Q III state. This spontaneous formation of the sextuple-Q III phase at demonstrates that a fully developed sextuple-Q superposition can be stabilized purely by the biquadratic interaction without the aid of an external magnetic field.

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- Bak, P.; Lebech, B. "Triple-" Modulated Magnetic Structure and Critical Behavior of Neodymium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1978, 40, 800–803. [CrossRef]

- McEwen, K.A.; Walker, M.B. Free-energy analysis of the single-q and double-q magnetic structures of neodymium. Phys. Rev. B 1986, 34, 1781–1783. [CrossRef]

- Zochowski, S.; McEwen, K. Thermal expansion study of the magnetic phase diagram of neodymium. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1986, 54, 515–516. [CrossRef]

- Forgan, E.; Rainford, B.; Lee, S.; Abell, J.; Bi, Y. The magnetic structure of CeAl2 is a non-chiral spiral. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 1990, 2, 10211.

- Longfield, M.J.; Paixão, J.A.; Bernhoeft, N.; Lander, G.H. Resonant x-ray scattering from multi-k magnetic structures. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 66, 054417. [CrossRef]

- Bernhoeft, N.; Paixão, J.A.; Detlefs, C.; Wilkins, S.B.; Javorský, P.; Blackburn, E.; Lander, G.H. Resonant x-ray scattering from UAs0.8Se0.2: Multi-k configurations. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 69, 174415. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.; Ehlers, G.; Wills, A.; Bramwell, S.T.; Gardner, J. Phase transitions, partial disorder and multi-k structures in Gd2Ti2O7. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2004, 16, L321. [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Forgan, E.M.; Nuttall, W.J.; Stirling, W.G.; Fort, D. High-resolution magnetic x-ray diffraction from neodymium. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 53, 726–730. [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.B.; Schweizer, J. Theoretical analysis of the double-q magnetic structure of CeAl2. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 74, 134411. [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, J.; Givord, F.; Boucherle, J.; Bourdarot, F.; Ressouche, E. The accurate magnetic structure of CeAl2 at various temperatures in the ordered state. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2008, 20, 135204. [CrossRef]

- Szabó, A.; Orlandi, F.; Manuel, P. Fragmented Spin Ice and Multi-k Ordering in Rare-Earth Antiperovskites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022, 129, 247201. [CrossRef]

- Ohgushi, K.; Murakami, S.; Nagaosa, N. Spin anisotropy and quantum Hall effect in the kagomé lattice: Chiral spin state based on a ferromagnet. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 62, R6065–R6068. [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, Y.; Oohara, Y.; Yoshizawa, H.; Nagaosa, N.; Tokura, Y. Spin chirality, Berry phase, and anomalous Hall effect in a frustrated ferromagnet. Science 2001, 291, 2573–2576. [CrossRef]

- Tatara, G.; Kawamura, H. Chirality-driven anomalous Hall effect in weak coupling regime. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2002, 71, 2613–2616. [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, A.; Pfleiderer, C.; Binz, B.; Rosch, A.; Ritz, R.; Niklowitz, P.G.; Böni, P. Topological Hall Effect in the A Phase of MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 186602. [CrossRef]

- Hamamoto, K.; Ezawa, M.; Nagaosa, N. Quantized topological Hall effect in skyrmion crystal. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 115417. [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, K.; Bibes, M.; Kohno, H. Topological Hall effect from strong to weak coupling. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2018, 87, 033705. [CrossRef]

- Tai, L.; Dai, B.; Li, J.; Huang, H.; Chong, S.K.; Wong, K.L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, P.; Deng, P.; Eckberg, C.; et al. Distinguishing the two-component anomalous Hall effect from the topological Hall effect. ACS nano 2022, 16, 17336–17346. [CrossRef]

- Zadorozhnyi, A.; Dahnovsky, Y. Topological Hall effect in three-dimensional centrosymmetric magnetic skyrmion crystals. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 107, 054436. [CrossRef]

- Shiomi, Y.; Kanazawa, N.; Shibata, K.; Onose, Y.; Tokura, Y. Topological Nernst effect in a three-dimensional skyrmion-lattice phase. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 88, 064409. [CrossRef]

- Mizuta, Y.P.; Ishii, F. Large anomalous Nernst effect in a skyrmion crystal. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28076. [CrossRef]

- Hirschberger, M.; Spitz, L.; Nomoto, T.; Kurumaji, T.; Gao, S.; Masell, J.; Nakajima, T.; Kikkawa, A.; Yamasaki, Y.; Sagayama, H.; et al. Topological Nernst Effect of the Two-Dimensional Skyrmion Lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 125, 076602. [CrossRef]

- Weißenhofer, M.; Nowak, U. Topology dependence of skyrmion Seebeck and skyrmion Nernst effect. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6801. [CrossRef]

- Oike, H.; Ebino, T.; Koretsune, T.; Kikkawa, A.; Hirschberger, M.; Taguchi, Y.; Tokura, Y.; Kagawa, F. Topological Nernst effect emerging from real-space gauge field and thermal fluctuations in a magnetic skyrmion lattice. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 106, 214425. [CrossRef]

- Nagaosa, N.; Tokura, Y. Topological properties and dynamics of magnetic skyrmions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 899–911. [CrossRef]

- Tokura, Y.; Kanazawa, N. Magnetic Skyrmion Materials. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 2857. [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Yambe, R. Stabilization mechanisms of magnetic skyrmion crystal and multiple-Q states based on momentum-resolved spin interactions. Mater. Today Quantum 2024, 3, 100010. [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, H. Frustration-induced skyrmion crystals in centrosymmetric magnets. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2025, 37, 183004. [CrossRef]

- Okubo, T.; Chung, S.; Kawamura, H. Multiple-q States and the Skyrmion Lattice of the Triangular-Lattice Heisenberg Antiferromagnet under Magnetic Fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 017206. [CrossRef]

- Leonov, A.O.; Mostovoy, M. Multiply periodic states and isolated skyrmions in an anisotropic frustrated magnet. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8275. [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S. In-plane magnetic field-induced skyrmion crystal in frustrated magnets with easy-plane anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 224418. [CrossRef]

- Lohani, V.; Hickey, C.; Masell, J.; Rosch, A. Quantum Skyrmions in Frustrated Ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. X 2019, 9, 041063. [CrossRef]

- Naya, C.; Schubring, D.; Shifman, M.; Wang, Z. Skyrmions and hopfions in three-dimensional frustrated magnets. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 106, 094434. [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.; Hermanns, M.; Bauer, B.; Garst, M.; Trebst, S. Spin-orbit physics of j = Mott insulators on the triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 91, 155135. [CrossRef]

- Rousochatzakis, I.; Rössler, U.K.; van den Brink, J.; Daghofer, M. Kitaev anisotropy induces mesoscopic Z2 vortex crystals in frustrated hexagonal antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 104417. [CrossRef]

- Amoroso, D.; Barone, P.; Picozzi, S. Spontaneous skyrmionic lattice from anisotropic symmetric exchange in a Ni-halide monolayer. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5784. [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Motome, Y. Noncoplanar multiple-Q spin textures by itinerant frustration: Effects of single-ion anisotropy and bond-dependent anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 054422. [CrossRef]

- Hirschberger, M.; Hayami, S.; Tokura, Y. Nanometric skyrmion lattice from anisotropic exchange interactions in a centrosymmetric host. New J. Phys. 2021, 23, 023039. [CrossRef]

- Yambe, R.; Hayami, S. Skyrmion crystals in centrosymmetric itinerant magnets without horizontal mirror plane. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11184. [CrossRef]

- Amoroso, D.; Barone, P.; Picozzi, S. Interplay between Single-Ion and Two-Ion Anisotropies in Frustrated 2D Semiconductors and Tuning of Magnetic Structures Topology. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1873. [CrossRef]

- Yambe, R.; Hayami, S. Effective spin model in momentum space: Toward a systematic understanding of multiple-Q instability by momentum-resolved anisotropic exchange interactions. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 106, 174437. [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S. Skyrmion crystal and spiral phases in centrosymmetric bilayer magnets with staggered Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 014408. [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.Z. Skyrmion lattice in centrosymmetric magnets with local Dzyaloshinsky-Moriya interaction. Mater. Today Quantum 2024, 2, 100006. [CrossRef]

- Momoi, T.; Kubo, K.; Niki, K. Possible Chiral Phase Transition in Two-Dimensional Solid 3He. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 79, 2081–2084. [CrossRef]

- Heinze, S.; von Bergmann, K.; Menzel, M.; Brede, J.; Kubetzka, A.; Wiesendanger, R.; Bihlmayer, G.; Blügel, S. Spontaneous atomic-scale magnetic skyrmion lattice in two dimensions. Nat. Phys. 2011, 7, 713–718. [CrossRef]

- Grytsiuk, S.; Hanke, J.P.; Hoffmann, M.; Bouaziz, J.; Gomonay, O.; Bihlmayer, G.; Lounis, S.; Mokrousov, Y.; Blügel, S. Topological–chiral magnetic interactions driven by emergent orbital magnetism. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 511. [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Haldar, S.; von Malottki, S.; Heinze, S. Role of higher-order exchange interactions for skyrmion stability. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4756. [CrossRef]

- Mendive-Tapia, E.; dos Santos Dias, M.; Grytsiuk, S.; Staunton, J.B.; Blügel, S.; Lounis, S. Short period magnetization texture of B20-MnGe explained by thermally fluctuating local moments. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 024410. [CrossRef]

- Gutzeit, M.; Kubetzka, A.; Haldar, S.; Pralow, H.; Goerzen, M.A.; Wiesendanger, R.; Heinze, S.; von Bergmann, K. Nano-scale collinear multi-Q states driven by higher-order interactions. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5764.

- Beyer, B.; Gutzeit, M.; Drevelow, T.; Schwermer, I.; Haldar, S.; Heinze, S. Bilayer triple-Q state driven by interlayer higher-order exchange interactions. Phys. Rev. B 2025, 112, 094430. [CrossRef]

- Kurz, P.; Bihlmayer, G.; Hirai, K.; Blügel, S. Three-Dimensional Spin Structure on a Two-Dimensional Lattice: Mn/Cu(111). Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 86, 1106–1109. [CrossRef]

- Domenge, J.C.; Sindzingre, P.; Lhuillier, C.; Pierre, L. Twelve sublattice ordered phase in the J1 − J2 model on the kagomé lattice. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 72, 024433. [CrossRef]

- Martin, I.; Batista, C.D. Itinerant Electron-Driven Chiral Magnetic Ordering and Spontaneous Quantum Hall Effect in Triangular Lattice Models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 156402. [CrossRef]

- Janson, O.; Richter, J.; Rosner, H. Modified Kagome Physics in the Natural Spin-1/2 Kagome Lattice Systems: Kapellasite Cu3Zn(OH)6Cl2 and Haydeeite Cu3Mg(OH)6Cl2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 106403. [CrossRef]

- Messio, L.; Lhuillier, C.; Misguich, G. Lattice symmetries and regular magnetic orders in classical frustrated antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 83, 184401. [CrossRef]

- Rosales, H.D.; Cabra, D.C.; Lamas, C.A.; Pujol, P.; Zhitomirsky, M.E. Broken discrete symmetries in a frustrated honeycomb antiferromagnet. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 87, 104402. [CrossRef]

- Barros, K.; Venderbos, J.W.F.; Chern, G.W.; Batista, C.D. Exotic magnetic orderings in the kagome Kondo-lattice model. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 245119. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Z. Chiral Spin Density Wave Order on the Frustrated Honeycomb and Bilayer Triangle Lattice Hubbard Model at Half-Filling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 114, 216402. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; O’Brien, P.; Henley, C.L.; Lawler, M.J. Phase diagram of the Kondo lattice model on the kagome lattice. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 024401. [CrossRef]

- Venderbos, J.W.F. Multi-Q hexagonal spin density waves and dynamically generated spin-orbit coupling: Time-reversal invariant analog of the chiral spin density wave. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 115108. [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Yambe, R. Meron-antimeron crystals in noncentrosymmetric itinerant magnets on a triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 104, 094425. [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, T.; Brückel, T.; Burlet, P. Spin correlation in the frustrated antiferromagnet MnS2 above the Néel temperature. Phys. Rev. B 1991, 44, 7394–7402. [CrossRef]

- Hagihala, M.; Zheng, X.G.; Kawae, T.; Sato, T.J. Successive antiferromagnetic transitions with multi-k and noncoplanar spin order, spin fluctuations, and field-induced phases in deformed pyrochlore compound Co2(OH)3Br. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82, 214424. [CrossRef]

- Okubo, T.; Nguyen, T.H.; Kawamura, H. Cubic and noncubic multiple-q states in the Heisenberg antiferromagnet on the pyrochlore lattice. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 144432. [CrossRef]

- Chern, G.W. Noncoplanar Magnetic Ordering Driven by Itinerant Electrons on the Pyrochlore Lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 226403. [CrossRef]

- Balla, P.; Iqbal, Y.; Penc, K. Degenerate manifolds, helimagnets, and multi-Q chiral phases in the classical Heisenberg antiferromagnet on the face-centered-cubic lattice. Phys. Rev. Research 2020, 2, 043278. [CrossRef]

- Yokota, T. Various Ordered States in Heisenberg FCC Antiferromagnets with Dipole–Dipole Interactions. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2022, 91, 064003. [CrossRef]

- Mühlbauer, S.; Binz, B.; Jonietz, F.; Pfleiderer, C.; Rosch, A.; Neubauer, A.; Georgii, R.; Böni, P. Skyrmion lattice in a chiral magnet. Science 2009, 323, 915–919. [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, A.N.; Yablonskii, D.A. Thermodynamically stable “vortices" in magnetically ordered crystals: The mixed state of magnets. Sov. Phys. JETP 1989, 68, 101.

- Bogdanov, A.; Hubert, A. Thermodynamically stable magnetic vortex states in magnetic crystals. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1994, 138, 255 – 269. [CrossRef]

- Rößler, U.K.; Bogdanov, A.N.; Pfleiderer, C. Spontaneous skyrmion ground states in magnetic metals. Nature 2006, 442, 797–801. [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.D.; Onoda, S.; Nagaosa, N.; Han, J.H. Skyrmions and anomalous Hall effect in a Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya spiral magnet. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80, 054416. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.Z.; Onose, Y.; Kanazawa, N.; Park, J.H.; Han, J.H.; Matsui, Y.; Nagaosa, N.; Tokura, Y. Real-space observation of a two-dimensional skyrmion crystal. Nature 2010, 465, 901–904. [CrossRef]

- Butenko, A.B.; Leonov, A.A.; Rößler, U.K.; Bogdanov, A.N. Stabilization of skyrmion textures by uniaxial distortions in noncentrosymmetric cubic helimagnets. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82, 052403. [CrossRef]

- Münzer, W.; Neubauer, A.; Adams, T.; Mühlbauer, S.; Franz, C.; Jonietz, F.; Georgii, R.; Böni, P.; Pedersen, B.; Schmidt, M.; et al. Skyrmion lattice in the doped semiconductor Fe1-xCoxSi. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 041203. [CrossRef]

- Adams, T.; Mühlbauer, S.; Neubauer, A.; Münzer, W.; Jonietz, F.; Georgii, R.; Pedersen, B.; Böni, P.; Rosch, A.; Pfleiderer, C. Skyrmion lattice domains in Fe1-xCoxSi. In Proceedings of the J. Phys. Conf. Ser. IOP Publishing, 2010, Vol. 200, p. 032001. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.Z.; Kanazawa, N.; Onose, Y.; Kimoto, K.; Zhang, W.; Ishiwata, S.; Matsui, Y.; Tokura, Y. Near room-temperature formation of a skyrmion crystal in thin-films of the helimagnet FeGe. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 106–109. [CrossRef]

- Adams, T.; Mühlbauer, S.; Pfleiderer, C.; Jonietz, F.; Bauer, A.; Neubauer, A.; Georgii, R.; Böni, P.; Keiderling, U.; Everschor, K.; et al. Long-Range Crystalline Nature of the Skyrmion Lattice in MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 217206. [CrossRef]

- Dzyaloshinsky, I. A thermodynamic theory of “weak” ferromagnetism of antiferromagnetics. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1958, 4, 241–255.

- Moriya, T. Anisotropic superexchange interaction and weak ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. 1960, 120, 91. [CrossRef]

- Akagi, Y.; Udagawa, M.; Motome, Y. Hidden Multiple-Spin Interactions as an Origin of Spin Scalar Chiral Order in Frustrated Kondo Lattice Models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 096401. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M. Half-filled Hubbard model at low temperature. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 1977, 10, 1289. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimori, A.; Inagaki, S. Fourth Order Interaction Effects on the Antiferromagnetic Structures. I. fcc Hubbard Model. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1978, 44, 101–107. [CrossRef]

- Lounis, S. Multiple-scattering approach for multi-spin chiral magnetic interactions: application to the one-and two-dimensional Rashba electron gas. New J. Phys. 2020, 22, 103003. [CrossRef]

- Takagi, R.; White, J.; Hayami, S.; Arita, R.; Honecker, D.; Rønnow, H.; Tokura, Y.; Seki, S. Multiple-q noncollinear magnetism in an itinerant hexagonal magnet. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaau3402. [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.R.; Sugawara, H.; Matsuda, T.D.; Sato, H.; Mallik, R.; Sampathkumaran, E.V. Magnetic anisotropy, first-order-like metamagnetic transitions, and large negative magnetoresistance in single-crystal Gd2PdSi3. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 60, 12162–12165. [CrossRef]

- Kurumaji, T.; Nakajima, T.; Hirschberger, M.; Kikkawa, A.; Yamasaki, Y.; Sagayama, H.; Nakao, H.; Taguchi, Y.; Arima, T.h.; Tokura, Y. Skyrmion lattice with a giant topological Hall effect in a frustrated triangular-lattice magnet. Science 2019, 365, 914–918. [CrossRef]

- Sampathkumaran, E.V. A report of (topological) Hall anomaly two decades ago in Gd2PdSi3, and its relevance to the history of the field of Topological Hall Effect due to magnetic skyrmions. arXiv:1910.09194 2019.

- Hirschberger, M.; Nakajima, T.; Kriener, M.; Kurumaji, T.; Spitz, L.; Gao, S.; Kikkawa, A.; Yamasaki, Y.; Sagayama, H.; Nakao, H.; et al. High-field depinned phase and planar Hall effect in the skyrmion host Gd2PdSi3. Phys. Rev. B 2020, 101, 220401(R). [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Iyer, K.K.; Paulose, P.L.; Sampathkumaran, E.V. Magnetic and transport anomalies in R2RhSi3(R = Gd, Tb, and Dy) resembling those of the exotic magnetic material Gd2PdSi3. Phys. Rev. B 2020, 101, 144440. [CrossRef]

- Spachmann, S.; Elghandour, A.; Frontzek, M.; Löser, W.; Klingeler, R. Magnetoelastic coupling and phases in the skyrmion lattice magnet Gd2PdSi3 discovered by high-resolution dilatometry. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 184424. [CrossRef]

- Gomilšek, M.; Hicken, T.J.; Wilson, M.N.; Franke, K.J.A.; Huddart, B.M.; Štefančič, A.; Holt, S.J.R.; Balakrishnan, G.; Mayoh, D.A.; Birch, M.T.; et al. Anisotropic Skyrmion and Multi-q Spin Dynamics in Centrosymmetric Gd2PdSi3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2025, 134, 046702. [CrossRef]

- Chandragiri, V.; Iyer, K.K.; Sampathkumaran, E. Magnetic behavior of Gd3Ru4Al12, a layered compound with distorted kagomé net. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2016, 28, 286002. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Kabeya, N.; Kobayashi, M.; Araki, K.; Katoh, K.; Ochiai, A. Spin trimer formation in the metallic compound Gd3Ru4Al12 with a distorted kagome lattice structure. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 98, 054410. [CrossRef]

- Hirschberger, M.; Nakajima, T.; Gao, S.; Peng, L.; Kikkawa, A.; Kurumaji, T.; Kriener, M.; Yamasaki, Y.; Sagayama, H.; Nakao, H.; et al. Skyrmion phase and competing magnetic orders on a breathing kagome lattice. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5831. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S. Magnetic anisotropies and skyrmion lattice related to magnetic quadrupole interactions of the RKKY mechanism in the frustrated spin-trimer system Gd3Ru4Al12 with a breathing kagome structure. Phys. Rev. B 2025, 111, 184433. [CrossRef]

- Khanh, N.D.; Nakajima, T.; Yu, X.; Gao, S.; Shibata, K.; Hirschberger, M.; Yamasaki, Y.; Sagayama, H.; Nakao, H.; Peng, L.; et al. Nanometric square skyrmion lattice in a centrosymmetric tetragonal magnet. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 444. [CrossRef]

- Wood, G.D.A.; Khalyavin, D.D.; Mayoh, D.A.; Bouaziz, J.; Hall, A.E.; Holt, S.J.R.; Orlandi, F.; Manuel, P.; Blügel, S.; Staunton, J.B.; et al. Double-Q ground state with topological charge stripes in the centrosymmetric skyrmion candidate GdRu2Si2. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 107, L180402. [CrossRef]

- Eremeev, S.; Glazkova, D.; Poelchen, G.; Kraiker, A.; Ali, K.; Tarasov, A.V.; Schulz, S.; Kliemt, K.; Chulkov, E.V.; Stolyarov, V.; et al. Insight into the electronic structure of the centrosymmetric skyrmion magnet GdRu2Si2. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 6678–6687. [CrossRef]

- Huddart, B.M.; Hernández-Melián, A.; Wood, G.D.A.; Mayoh, D.A.; Gomilšek, M.; Guguchia, Z.; Wang, C.; Hicken, T.J.; Blundell, S.J.; Balakrishnan, G.; et al. Field-orientation-dependent magnetic phases in GdRu2Si2 probed with muon-spin spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 2025, 111, 054440. [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Motome, Y. Magnetic field–temperature phase diagrams for multiple-Q magnetic ordering: Exact steepest descent approach to long-range interacting spin systems. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 174413. [CrossRef]

- Hewson, A.C. The Kondo Problem to Heavy Fermions (Cambridge Studies in Magnetism); Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Ruderman, M.A.; Kittel, C. Indirect Exchange Coupling of Nuclear Magnetic Moments by Conduction Electrons. Phys. Rev. 1954, 96, 99–102. [CrossRef]

- Kasuya, T. A Theory of Metallic Ferro- and Antiferromagnetism on Zener’s Model. Prog. Theor. Phys. 1956, 16, 45–57. [CrossRef]

- Yosida, K. Magnetic Properties of Cu-Mn Alloys. Phys. Rev. 1957, 106, 893–898. [CrossRef]

- Kakihana, M.; Aoki, D.; Nakamura, A.; Honda, F.; Nakashima, M.; Amako, Y.; Nakamura, S.; Sakakibara, T.; Hedo, M.; Nakama, T.; et al. Giant Hall resistivity and magnetoresistance in cubic chiral antiferromagnet EuPtSi. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2018, 87, 023701. [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, K.; Frontzek, M.D.; Matsuda, M.; Nakao, A.; Munakata, K.; Ohhara, T.; Kakihana, M.; Haga, Y.; Hedo, M.; Nakama, T.; et al. Unique Helical Magnetic Order and Field-Induced Phase in Trillium Lattice Antiferromagnet EuPtSi. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2019, 88, 013702. [CrossRef]

- Tabata, C.; Matsumura, T.; Nakao, H.; Michimura, S.; Kakihana, M.; Inami, T.; Kaneko, K.; Hedo, M.; Nakama, T.; Ōnuki, Y. Magnetic Field Induced Triple-q Magnetic Order in Trillium Lattice Antiferromagnet EuPtSi Studied by Resonant X-ray Scattering. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2019, 88, 093704. [CrossRef]

- Kakihana, M.; Aoki, D.; Nakamura, A.; Honda, F.; Nakashima, M.; Amako, Y.; Takeuchi, T.; Harima, H.; Hedo, M.; Nakama, T.; et al. Unique Magnetic Phases in the Skyrmion Lattice and Fermi Surface Properties in Cubic Chiral Antiferromagnet EuPtSi. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2019, 88, 094705. [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Yambe, R. Field-Direction Sensitive Skyrmion Crystals in Cubic Chiral Systems: Implication to 4f-Electron Compound EuPtSi. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2021, 90, 073705. [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S. Multiple-Q magnetism by anisotropic bilinear-biquadratic interactions in momentum space. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2020, 513, 167181. [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Yambe, R. Degeneracy Lifting of Néel, Bloch, and Anti-Skyrmion Crystals in Centrosymmetric Tetragonal Systems. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2020, 89, 103702. [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Yambe, R. Helicity locking of a square skyrmion crystal in a centrosymmetric lattice system without vertical mirror symmetry. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 104428. [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, R.; Hayami, S.; Motome, Y. Zero-Field Skyrmions with a High Topological Number in Itinerant Magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 118, 147205. [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Motome, Y. Effect of magnetic anisotropy on skyrmions with a high topological number in itinerant magnets. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 094420. [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Okubo, T.; Motome, Y. Phase shift in skyrmion crystals. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6927. [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S. Multiple skyrmion crystal phases by itinerant frustration in centrosymmetric tetragonal magnets. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2022, 91, 023705. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Su, Y.; Lin, S.Z.; Batista, C.D. Meron, skyrmion, and vortex crystals in centrosymmetric tetragonal magnets. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 104408. [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, Y.; Batista, C.D. Magnetic Vortex Crystals in Frustrated Mott Insulator. Phys. Rev. X 2014, 4, 011023. [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Lin, S.Z.; Kamiya, Y.; Batista, C.D. Vortices, skyrmions, and chirality waves in frustrated Mott insulators with a quenched periodic array of impurities. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 94, 174420. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).