Submitted:

28 November 2025

Posted:

28 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

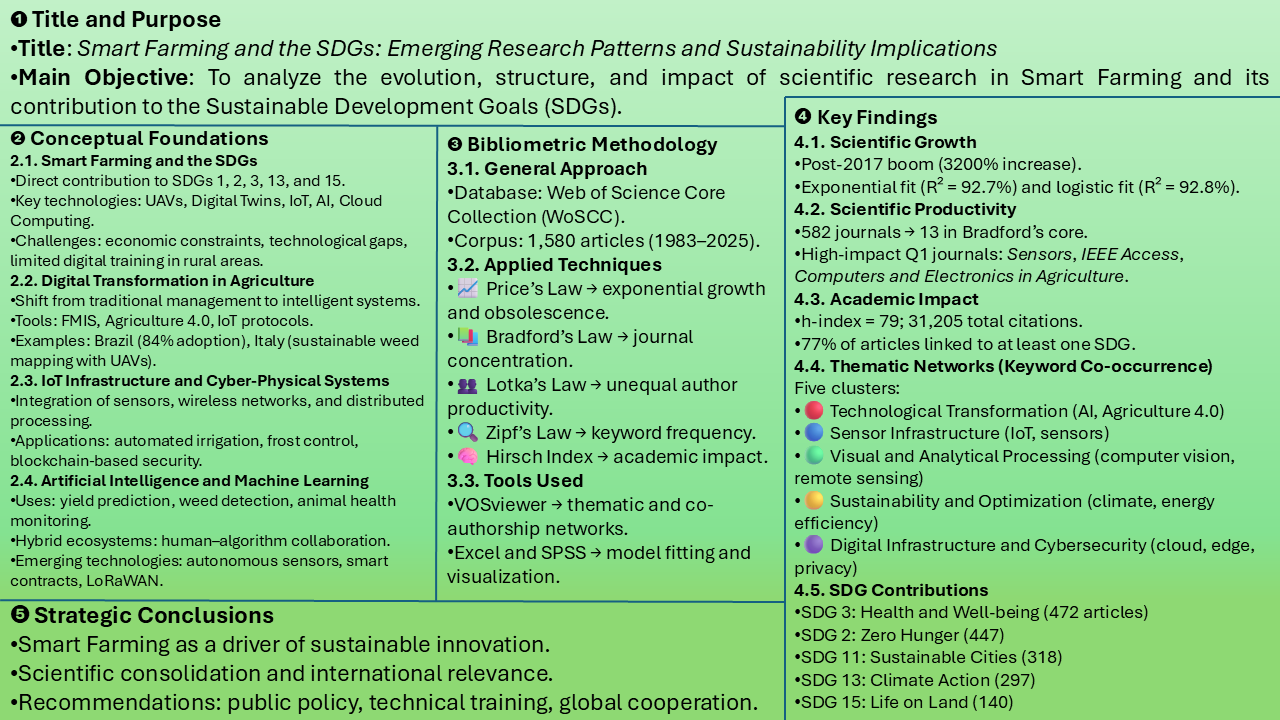

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Smart Farming and Its Contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

1.2. Digital Transformation in Agriculture: From Management to Intelligent Systems.

1.3. The Internet of Things (IoT) and Cyber-Physical Integration in Smart Farming

1.4. Smart Farming and Machine Learning in Agricultural Decision-Making

2. Methods

2.1. General Approach

2.2. Data Collection

- Document type: articles.

- Language: unrestricted (predominantly English).

- Time: unrestricted.

- Thematic coverage: all categories available on the Web of Science Core Collection (WoSCC).

2.3. Analytical Techniques Applied

2.3.1. Scientific Growth

2.3.2. Scientific Productivity

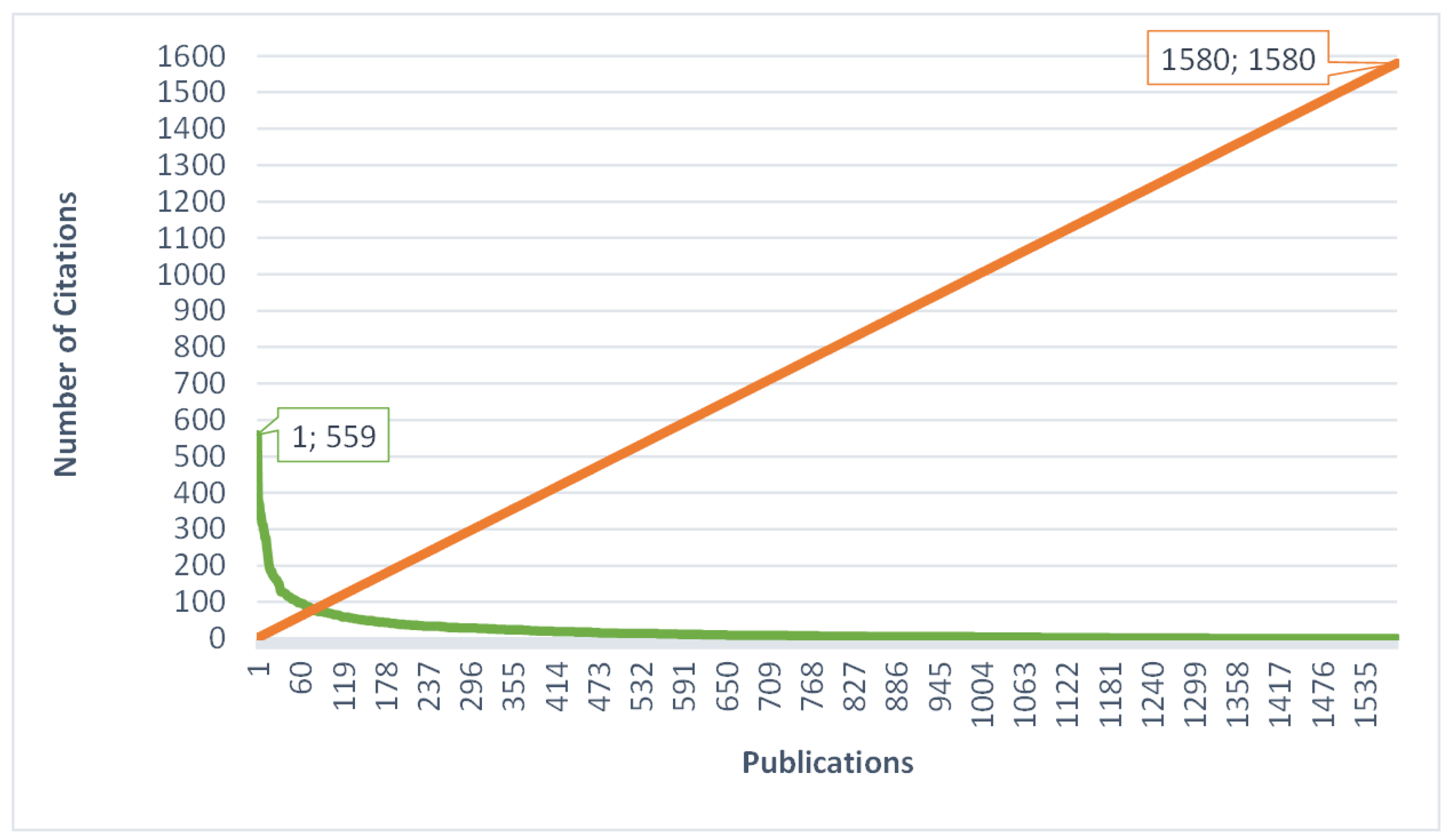

2.3.3. Academic Impact

2.3.4. Relationships and Scientific Networks

2.3.5. Relationship between Academic Impact and Sustainable Development Goals

2.4. Analytical Procedure

- VOSviewer (v.1.6.19): for network analyses (co-authorship, keyword co-occurrence) and visualization of thematic clusters.

- Microsoft Excel 365: for applying Price’s, Bradford’s, and Lotka’s laws and graphically representing annual publication trends.

- SPSS (v.23): for generating adjusted models for applying Price’s, exponential fit and S fit.

2.5. Study limitations

3. Results

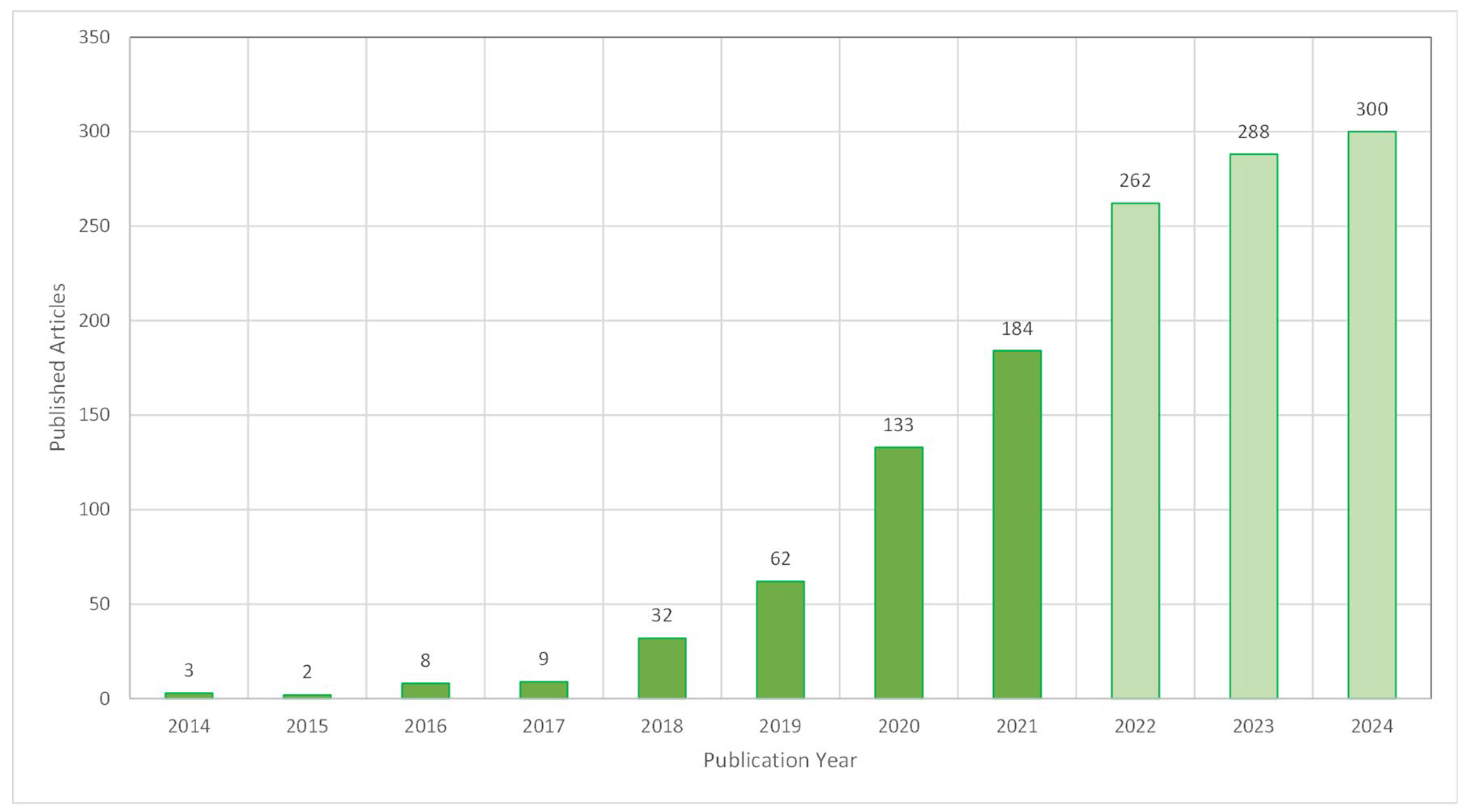

3.1. Scientific Growth

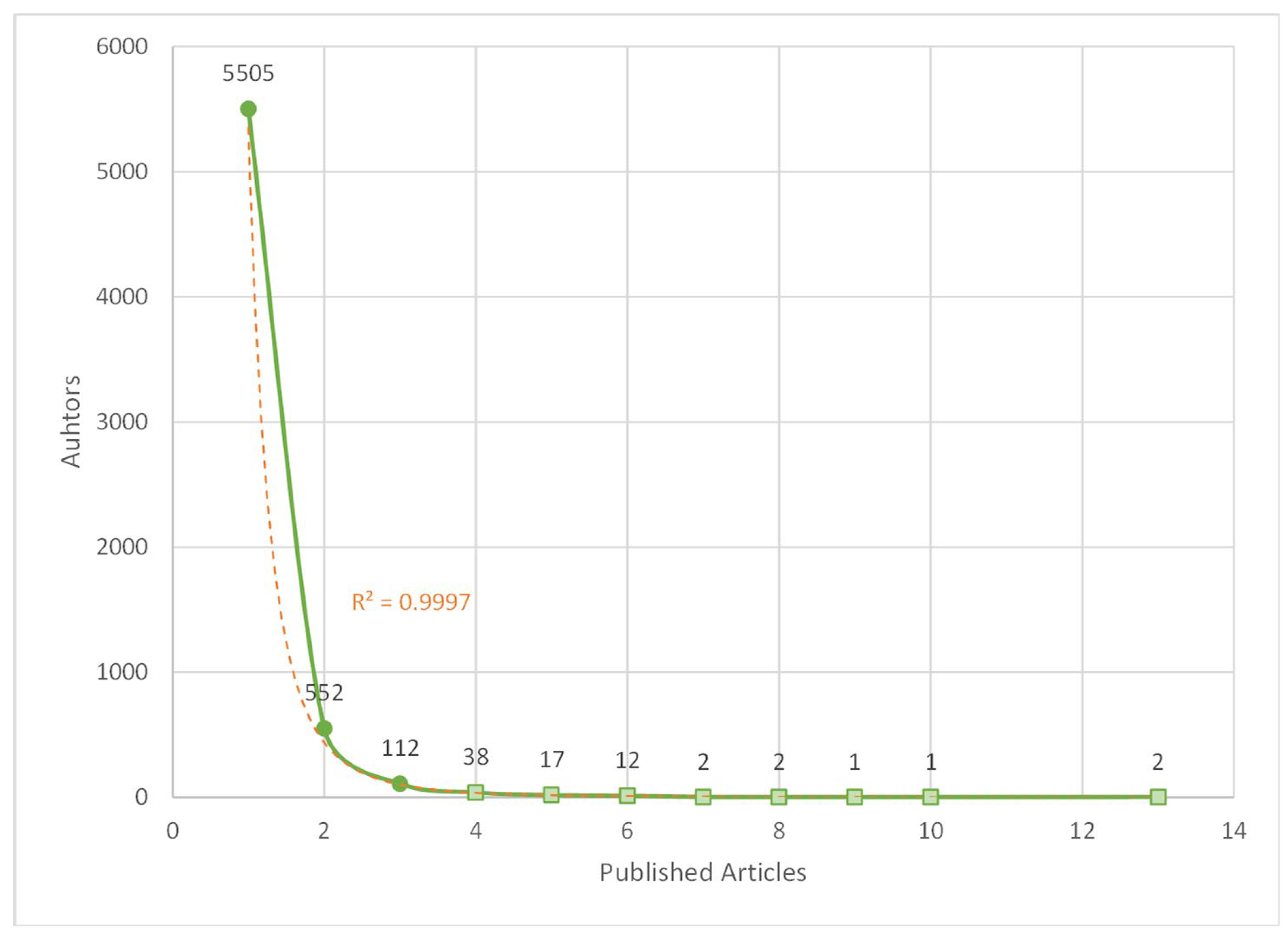

3.2. Scientific Productivity

| Zone | Number of articles | % | Journals (Empirical series) |

% | Bradford multipliers |

Journals (Theorical series) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucles | 512 | 32% | 13 | 2% | 9 x () = 9 | |

| Zone 1 | 523 | 33% | 98 | 17% | 7.54 = 98/13 | 9 x () = 68 |

| Zone 2 | 545 | 34% | 471 | 81% | 4.81 = 471/98 | 9 x () = 516 |

| Total | ∑ = 1.580 | 100% | ∑ = 582 | 100% | n = 6.17 | ∑ = 588 |

| Journals | Articles | Citations, WoS Core | JIF 2024 (WoS) | Quartile of impact (Qx) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensors | 75 | 1.836 | 3.5 | Q1 |

| Computers and Electronics in Agriculture | 69 | 2.947 | 15.1 | Q1 |

| IEEE Access | 60 | 1,968 | 3.6 | Q1 |

| Smart Agricultural Technology | 50 | 475 | 5.7 | Q1 |

| Sustainability | 48 | 688 | 3.3 | Q1 |

| Agriculture-Basel | 45 | 734 | 3.6 | Q1 |

| Agronomy-Basel | 37 | 743 | 3.4 | Q1 |

| Applied Sciences-Basel | 34 | 433 | 2.5 | Q1 |

| IEEE Internet of Things Journal | 24 | 1312 | 8.9 | Q1 |

| Animals | 20 | 208 | 2.7 | Q1 |

| Scientific Reports | 18 | 84 | 3.9 | Q1 |

| Multimedia Tools and Applications | 17 | 336 | 3.7 | Q1 |

| Frontiers in Plant Science | 15 | 278 | 4.8 | Q1 |

3.3. Academic Impact

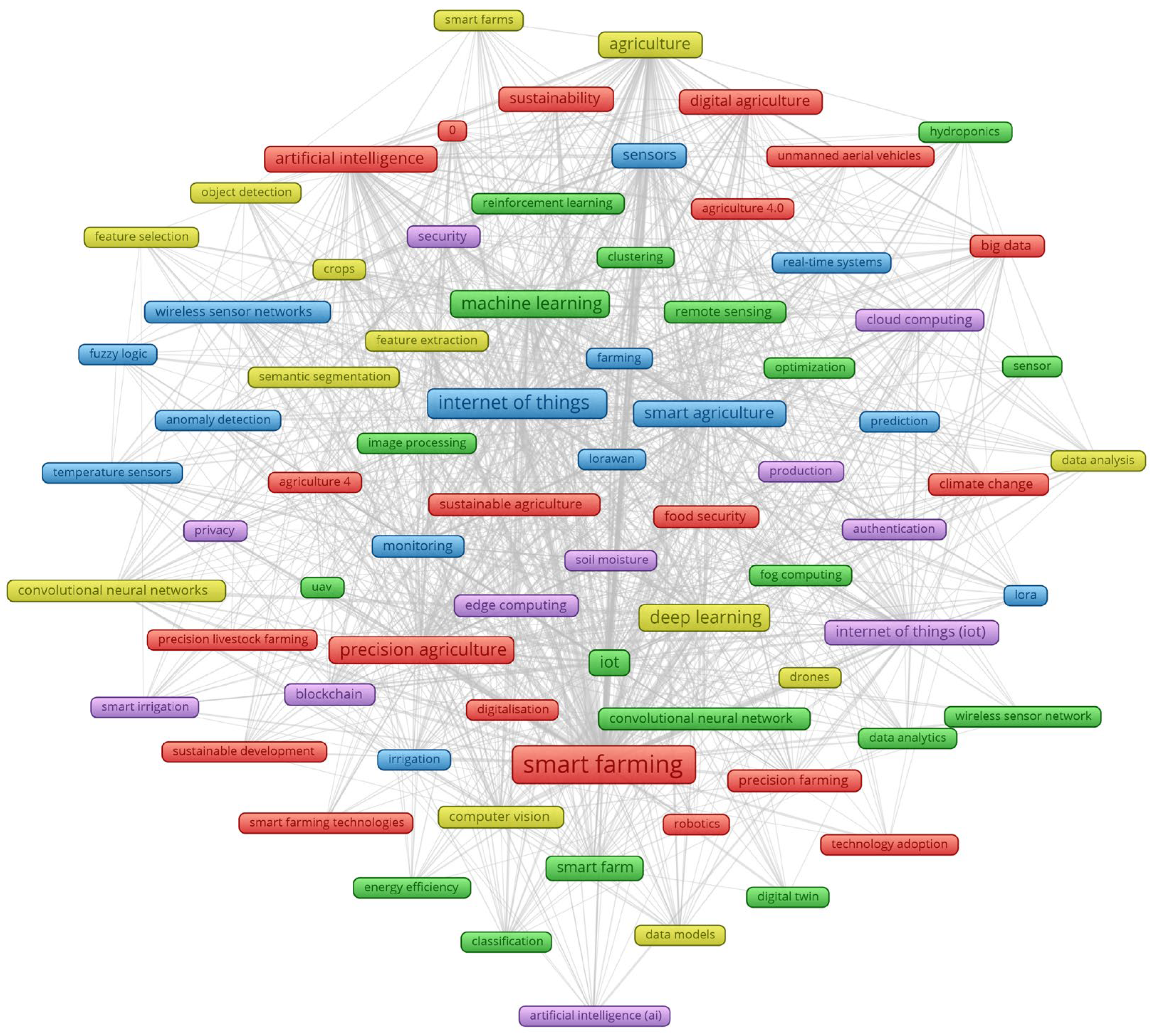

3.4. Relationships and Scientific Networks

- The red cluster (Technological Transformation of Agriculture), which articulates the central concepts that define the paradigm of smart agriculture, with key terms such as smart farming, precision agriculture, digital agriculture, agriculture 4.0, technology adoption, artificial intelligence. This cluster represents the conceptual core of technological change in agriculture, highlighting the evolution towards automated systems based on data and algorithms. In terms of relationships, it connects with all other clusters, functioning as a coordinating hub.

- The blue cluster (Sensory Infrastructure and Connectivity), a group that focuses on devices and systems that enable real-time data collection, with key terms such as: Internet of Things (IoT), smart agriculture, sensors, monitoring, real-time systems. This cluster provides the operational basis for the implementation of smart agriculture, facilitating continuous observation of the agricultural environment. In terms of its relationships, it is closely linked to the green cluster (analysis) and the red cluster (transformation).

- The green cluster (Visual and Analytical Processing), a group that highlights the tools of analysis and computational perception applied to agriculture, with key terms such as computer vision, remote sensing, data analytics, smart farm, agriculture. This cluster allows images, satellite data, and metrics to be interpreted to make accurate agronomic decisions. Thematically, it acts as a bridge between infrastructure (blue) and strategic decision-making (yellow).

- The yellow cluster (Sustainability and optimization), a group that introduces the environmental and energy efficiency dimension into the agricultural system, with key terms such as sustainability, climate change, energy efficiency, feature selection, data analysis. This cluster incorporates sustainability and algorithmic optimization criteria into agricultural management. Its terms are connected to data processing (green) and the strategic core (red).

- The purple cluster (Digital Infrastructure and Cybersecurity), a group that addresses the technical aspects of data management and system protection, with key terms such as security, authentication, privacy, edge computing, and cloud computing. This cluster focuses on ensuring the integrity, privacy, and efficiency of data processing in distributed environments. It is a cluster that is linked to all clusters, especially the blue (sensors) and green (analysis) clusters.

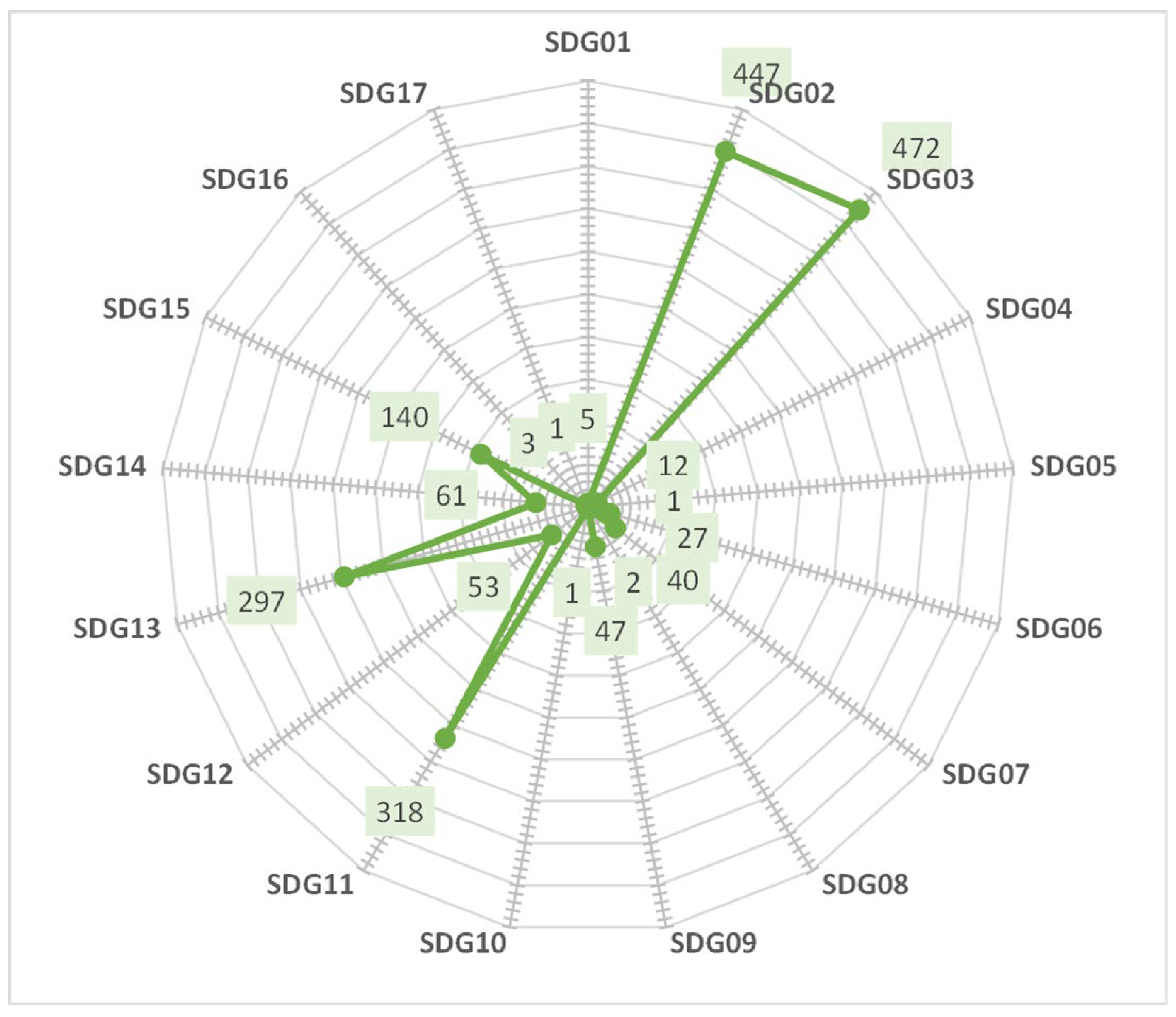

3.5. Relationship between Academic Impact and Sustainable Development Goals

- SDG 2: Zero Hunger (447 articles), demonstrating Smart Farming’s contribution to productivity, food security, and agricultural sustainability.

- SDG 3: Good Health (472 articles) is strongly represented, driven by research reducing chemical inputs, improving food quality and traceability, and enhancing safety through automation.

- SDG 11: Sustainable cities and communities (318) where Smart Farming technologies such as vertical farming, urban agriculture systems, and controlled environment agriculture support sustainable urban development and resilient food systems.

- SDG 13: Climate Action (297 articles), reflecting the growing interest in mitigating climate change through resilient, low-emission agricultural practices.

- SDG 15: Life on Land (140 articles), highlighting the field’s strong orientation toward digitalization, automation, and technological innovation in agriculture.

Discussion

| Authors | Journals | Article Title | DOI |

Times Cited | SDGs | Brief conclusions studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartman et al., 2018 [84] | Microbiome | Cropping practices manipulate abundance patterns of root and soil microbiome members paving the way to smart farming | 10.1186/s40168-017-0389-9 | 559 | 2, 13, 14, 15 | Evidence suggests microbiome-targeted cropping can enhance soil health and sustainable yields; targeted practices may enable resilient, low-input production through strategic microbial management. |

| Cabreira et al., 2019 [85] | Drones-Basel | Survey on Coverage Path Planning with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles | 10.3390/drones3010004 | 384 | 11 | UAV coverage-path planning improves monitoring efficiency and resource-use, enabling precise interventions that reduce inputs and environmental footprint. |

| Farooq et al., 2019 [86] | IEEE Access | A Survey on the Role of IoT in Agriculture for the Implementation of Smart Farming | 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2949703 | 376 | 3, 11 | IoT architecture facilitates continuous farm monitoring, supporting water and input efficiency while requiring security measures to protect data integrity. |

| Muangprathub et al., 2019 [87] |

Comput. Electron. Agric. | IoT and agriculture data analysis for smart farm | 10.1016/j.compag.2018.12.011 | 36 | 3, 11 | Low-cost WSN-based irrigation control optimizes water use, reduces costs, and increases productivity, promoting sustainable vegetable production via automated decision-making. |

| Maddikunta et al., 2021 [3] |

IEEE Sens. J. | Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Smart Agriculture: Applications, Requirements, and Challenges | 10.1109/JSEN.2021.3049471 | 348 | 11 | Affordable Bluetooth-enabled UAVs and sensors could democratize precision monitoring, lowering barriers and enabling sustainable smallholder uptake. |

| Rose & Chilvers 2018 [88] |

Front. Sustain. Food Syst. | Agriculture 4.0: Broadening Responsible Innovation in an Era of Smart Farming | 10.3389/fsufs.2018.00087 | 340 | 2 | Responsible innovation frameworks are essential to ensure smart technologies advance sustainability without marginalizing farming communities. |

| Nevavuori et al., 2019 [46] |

Comput. Electron. Agric. | Crop yield prediction with deep convolutional neural networks | 10.1016/j.compag.2019.104859 | 318 | 13, 15 | CNN-based UAV yield prediction supports precise input allocation and improved forecasting, enhancing resource efficiency and sustainable decision-making. |

| Wan & Goudos, 2020 [89] |

Comput. Netw. | Faster R-CNN for multi-class fruit detection using a robotic vision system | 10.1016/j.comnet.2019.107036 | 313 | 3 | Deep-learning fruit detection enables autonomous harvesting and accurate yield mapping, reducing labor needs and postharvest losses for sustainable production. |

| Ahmed et al., 2018 [90] |

IEEE Internet Things J. | Internet of Things (IoT) for Smart Precision Agriculture and Farming in Rural Areas | 10.1109/JIOT.2018.2879579 | 311 |

3, 11 | Fog-empowered IoT reduces latency and improves rural connectivity, enabling reliable, energy-efficient monitoring for sustainable farm management. |

| Verdouw et al., 2021 [4] |

Agric. Syst. | Digital twins in smart farming | 10.1016/j.agsy.2020.103046 | 300 | 9,12 | Digital Twins enable scenario testing and remote control, improving resource optimization and sustainability across diverse farming systems. |

| Wazid et al., 2018 [91] |

IEEE Internet Things J. | Design of Secure User Authenticated Key Management Protocol for Generic IoT Networks | 10.1109/JIOT.2017.2780232 | 287 | 3,11 | Secure hierarchical IoT authentication strengthens data trustworthiness, a prerequisite for sustainable, data-driven agricultural decisions. |

| Finger et al., 2019 [92] |

Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. | Precision Farming at the Nexus of Agricultural Production and the Environment | 10.1146/annurev-resource-100518-093929 | 275 | 2 | Multi-layered cybersecurity strategies are critical to maintain resilient, trustworthy IoT ecosystems that underpin sustainable precision agriculture. |

| Gupta et al., 2020 [5] | IEEE Access | Security and Privacy in Smart Farming: Challenges and Opportunities | 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2975142 | 275 | 3, 11 | Precision farming reduces input waste and environmental externalities, justifying policy support to democratize benefits for smallholders. |

| Zamora-Izquierdo et al., 2019 [93] | Biosyst. Eng. | Smart farming IoT platform based on edge and cloud computing | 10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2018.10.014 | 248 | 3, 11 | Open-source, low-cost platform for soilless greenhouses enables sustainable, resilient hydroponic production using edge-cloud orchestration and adaptive control. |

| Sa et al., 2018 [94] | IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. | weedNet: Dense Semantic Weed Classification Using Multispectral Images and MAV for Smart Farming | 10.1109/LRA.2017.2774979 | 241 | 3 | Dense semantic weed classification with MAVs enables selective herbicide application, greatly reducing chemical use and environmental impact. |

| Jakku et al., 2019 [95] | NJAS-Wagen. J. Life Sci. | If they don't tell us what they do with it, why would we trust them? Trust, transparency and benefit-sharing in Smart Farming | 10.1016/j.njas.2018.11.002 | 218 | 2 | Socio-technical analyses reveal trust and data governance as central to equitable, sustainable big-data agriculture adoption. |

| Caffaro et al., 2020 [7] | J. Rural Stud. | Drivers of farmers intention to adopt technological innovations in Italy: The role of information sources, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use | 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.04.028 | 206 | 2 | Farmers’ technology acceptance depends on perceived usefulness; tailored extension and credible information sources accelerate sustainable SFT uptake. |

| Jayaraman et al., 2016 [96] | Sensors | Internet of Things Platform for Smart Farming: Experiences and Lessons Learnt | 10.3390/s16111884 | 193 | 3, 11 | IoT-enabled crop performance platforms automate data collection and personalized recommendations, improving resource efficiency and adaptive management. |

| Wiseman et al., 2019 [97] | NJAS-Wagen. J. Life Sci. | Farmers and their data: An examination of farmers' reluctance to share their data through the lens of the laws impacting smart farming | 10.1016/j.njas.2019.04.007 | 185 | 2 | Deep-learning vineyard disease detection drastically reduces chemical usage by enabling targeted treatments, supporting sustainable viticulture. |

| Kerkech et al., 2020 [10] | Comput. Electron. Agric. | Vine disease detection in UAV multispectral images using optimized image registration and deep learning segmentation approach | 10.1016/j.compag.2020.105446 | 185 | 13, 15 | Lack of transparent data governance undermines farmer trust; robust policies and governance frameworks are essential for sustainable digital agriculture. |

| Jiang et al., 2020 [98] | Comput. Electron. Agric. | CNN feature based graph convolutional network for weed and crop recognition in smart farming | 10.1016/j.compag.2020.105450 | 184 | 3 | GCN-based weed recognition with limited labels supports affordable, accurate field automation, decreasing herbicide use and environmental harm. |

| Saggi & Jain 2019 [99] | Comput. Electron. Agric. | Reference evapotranspiration estimation and modeling of the Punjab Northern India using deep learning | 10.1016/j.compag.2018.11.031 | 175 | 6,13,14 | H2O ensemble models accurately estimate evapotranspiration, enabling water – efficient irrigation scheduling and sustainable water management. |

| Kernecker et al., 2020 [8] | Precis. Agric. | Experience versus expectation: farmers' perceptions of smart farming technologies for cropping systems across Europe | 10.1007/s11119-019-09651-z | 173 | 2 | SFT adoption varies by farm context; inclusive co-design and impartial advice improve relevance and sustainability across diverse farms |

| Alonso et al., 2020 [6] | AD HOC NETW | An intelligent Edge-IoT platform for monitoring livestock and crops in a dairy farming scenario | 10.1016/j.adhoc.2019.102047 | 169 | 3,11 | IoT, edge, and blockchain integration enhance traceability and resource optimization, improving dairy farm sustainability and food-chain transparency. |

| Sanchez-Iborra et al., 2018 [100] | Sensors | Performance Evaluation of LoRa Considering Scenario Conditions | 10.3390/s18030772 | 168 | 3,11 | LoRa WAN performance studies guide low-power network deployment, enabling scalable, energy-efficient monitoring for sustainable rural IoT applications |

| Sozzi et al., 2022 [101] | Agronomy-Basel | Automatic Bunch Detection in White Grape Varieties Using YOLOv3, YOLOv4, and YOLOv5 Deep Learning Algorithms | 10.3390/agronomy12020319 | 163 | 3 | YOLO object detection for grapes supports real-time yield estimation, enabling efficient resource planning and reduced waste. |

| Bhat et al., 2021 [49] | IEEE Access | Big Data and AI Revolution in Precision Agriculture: Survey and Challenges | 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3102227 | 162 | 2 | Big Data and ML applications can improve decision-making and sustainability, but social, economic, and policy barriers must be addressed. |

| Subeesh et al., 2021 [102] | Artif. Intell. Agric. | Automation and digitization of agriculture using artificial intelligence and internet of things | 10.1016/j.aiia.2021.11.004 | 160 | 3,11 | Integrated IoT–AI farm machinery accelerates automation, boosting productivity while demanding responsible governance to ensure sustainability and equity. |

| Carolan, 2020 [103] | J. Peasant Stud. | Automated agrifood futures: robotics, labor and the distributive politics of digital agriculture | 10.1080/03066150.2019.1584189 | 156 | 2 | Wind-energy–harvesting nanogenerators enable self-powered sensors, supporting autonomous, low-footprint monitoring and sustainable farm electrification. |

| Eastwood et al., 2019 [104] | J. Agric. Environ. Ethics | Managing Socio-Ethical Challenges in the Development of Smart Farming: From a Fragmented to a Comprehensive Approach for Responsible Research and Innovation | 10.1007/s10806-017-9704-5 | 151 | 2 | Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) adoption in smart dairying promotes socially inclusive, ethically grounded technological development for sustainable livestock systems. |

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Musa, S.F.P.D.; Basir, K.H. Smart Farming: Towards a Sustainable Agri-Food System. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 3085–3099. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.C.; Pandey, M. Highlighting the Role of Agriculture and Geospatial Technology in Food Security and Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 3175–3195. [CrossRef]

- Maddikunta, P.K.R.; Hakak, S.; Alazab, M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Khan, W.Z.; Pham, Q.-V. Unmanned aerial vehicles in smart agriculture: Applications, requirements, and challenges. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 17608–17619. [CrossRef]

- Verdouw, C.; Tekinerdogan, B.; Beulens, A.; Wolfert, S. Digital Twins in Smart Farming. Agric. Syst. 2021, 189, 103046. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Abdelsalam, M.; Khorsandroo, S.; Mittal, S. Security and privacy in smart farming: Challenges and opportunities. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 34564–34584. [CrossRef]

- Alonso, R.S.; Sittón-Candanedo, I.; García, Ó.; Prieto, J.; Rodríguez-González, S. An Intelligent Edge-IoT Platform for Monitoring Livestock and Crops in a Dairy Farming Scenario. Ad Hoc Netw. 2020, 98, 102047. [CrossRef]

- Caffaro, F.; Micheletti Cremasco, M.; Roccato, M.; Cavallo, E. Drivers of Farmers’ Intention to Adopt Technological Innovations in Italy: The Role of Information Sources, Perceived Usefulness, and Perceived Ease of Use. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 76, 264–271. [CrossRef]

- Kernecker, M.; Knierim, A.; Wurbs, A.; Kraus, T.; Borges, F. Experience versus Expectation: Farmers’ Perceptions of Smart Farming Technologies for Cropping Systems across Europe. Precis. Agric. 2020, 21, 34–50. [CrossRef]

- Giua, C.; Materia, V.C.; Camanzi, L. Smart Farming Technologies Adoption: Which Factors Play a Role in the Digital Transition? Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101869. [CrossRef]

- Kerkech, M.; Hafiane, A.; Canals, R. Vine Disease Detection in UAV Multispectral Images Using Optimized Image Registration and Deep Learning Segmentation Approach. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 174, 105446. [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Feng, Y.; Chen, P.; Liang, X.; Pang, H.; Jiang, T.; Wang, Z.L. Wind-driven Soft-contact Rotary Triboelectric Nanogenerator Based on Rabbit Fur with High Performance and Durability for Smart Farming. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2108580. [CrossRef]

- Idoje, G.; Dagiuklas, T.; Iqbal, M. Survey for Smart Farming Technologies: Challenges and Issues. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2021, 92, 107104. [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J.; Maye, D. What are the implications of digitalisation for agricultural knowledge? Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4. [CrossRef]

- Balaska, V.; Adamidou, Z.; Vryzas, Z.; Gasteratos, A. Sustainable Crop Protection via Robotics and Artificial Intelligence Solutions. Machines 2023, 11, 774. [CrossRef]

- Lytos, A.; Lagkas, T.; Sarigiannidis, P.; Zervakis, M.; Livanos, G. Towards Smart Farming: Systems, Frameworks and Exploitation of Multiple Sources. Comput. Netw. 2020, 172, 107147. [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, H.B.; Badarla, A. Cross-Layer Protocol for WSN-Assisted IoT Smart Farming Applications Using Nature Inspired Algorithm. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2021, 121, 3125–3149. [CrossRef]

- Abiri, R.; Rizan, N.; Balasundram, S.K.; Shahbazi, A.B.; Abdul-Hamid, H. Application of Digital Technologies for Ensuring Agricultural Productivity. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22601. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Kamble, S.; Mani, V.; Belhadi, A. An empirical investigation of the influence of industry 4.0 technology capabilities on agriculture supply chain integration and sustainable performance. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manage. 2024, 71, 12364–12384. [CrossRef]

- Balafoutis, A.T.; Van Evert, F.K.; Fountas, S. Smart Farming Technology Trends: Economic and Environmental Effects, Labor Impact, and Adoption Readiness. Agronomy (Basel) 2020, 10, 743. [CrossRef]

- Groher, T.; Heitkämper, K.; Walter, A.; Liebisch, F.; Umstätter, C. Status Quo of Adoption of Precision Agriculture Enabling Technologies in Swiss Plant Production. Precis. Agric. 2020, 21, 1327–1350. [CrossRef]

- Bolfe, É.L.; Jorge, L.A. de C.; Sanches, I.D.; Luchiari Júnior, A.; da Costa, C.C.; Victoria, D. de C.; Inamasu, R.Y.; Grego, C.R.; Ferreira, V.R.; Ramirez, A.R. Precision and Digital Agriculture: Adoption of Technologies and Perception of Brazilian Farmers. Agriculture 2020, 10, 653. [CrossRef]

- Mattivi, P.; Pappalardo, S.E.; Nikolić, N.; Mandolesi, L.; Persichetti, A.; De Marchi, M.; Masin, R. Can Commercial Low-Cost Drones and Open-Source GIS Technologies Be Suitable for Semi-Automatic Weed Mapping for Smart Farming? A Case Study in NE Italy. Remote Sens. (Basel) 2021, 13, 1869. [CrossRef]

- Jakku, E.; Fleming, A.; Espig, M.; Fielke, S.; Finlay-Smits, S.C.; Turner, J.A. Disruption Disrupted? Reflecting on the Relationship between Responsible Innovation and Digital Agriculture Research and Development at Multiple Levels in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. Agric. Syst. 2023, 204, 103555. [CrossRef]

- Latino, M.E.; Menegoli, M.; Corallo, A. Agriculture digitalization: A global examination based on bibliometric analysis. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manage. 2024, 71, 1330–1345. [CrossRef]

- Green, A.G.; Abdulai, A.-R.; Duncan, E.; Glaros, A.; Campbell, M.; Newell, R.; Quarshie, P.; Kc, K.B.; Newman, L.; Nost, E.; et al. A Scoping Review of the Digital Agricultural Revolution and Ecosystem Services: Implications for Canadian Policy and Research Agendas. Facets (Ott) 2021, 6, 1955–1985. [CrossRef]

- Kakamoukas, G.; Sarigiannidis, P.; Maropoulos, A.; Lagkas, T.; Zaralis, K.; Karaiskou, C. Towards Climate Smart Farming—A Reference Architecture for Integrated Farming Systems. Telecom 2021, 2, 52–74. [CrossRef]

- Kazancoglu, Y.; Lafci, C.; Kumar, A.; Luthra, S.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Berberoglu, Y. The Role of Agri-food 4.0 in Climate-smart Farming for Controlling Climate Change-related Risks: A Business Perspective Analysis. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2024, 33, 2788–2802. [CrossRef]

- Boronyak, L.; Jacobs, B.; Wallach, A.; McManus, J.; Stone, S.; Stevenson, S.; Smuts, B.; Zaranek, H. Pathways towards Coexistence with Large Carnivores in Production Systems. Agric. Human Values 2022, 39, 47–64. [CrossRef]

- Chukkapalli, S.S.L.; Mittal, S.; Gupta, M.; Abdelsalam, M.; Joshi, A.; Sandhu, R.; Joshi, K. Ontologies and artificial intelligence systems for the cooperative smart farming ecosystem. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 164045–164064. [CrossRef]

- Trilles, S.; González-Pérez, A.; Huerta, J. An IoT Platform Based on Microservices and Serverless Paradigms for Smart Farming Purposes. Sensors (Basel) 2020, 20, 2418. [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, F.K.; Karim, S.; Zeadally, S.; Nebhen, J. Recent trends in internet-of-things-enabled sensor technologies for smart agriculture. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 23583–23598. [CrossRef]

- Mahbub, M. A Smart Farming Concept Based on Smart Embedded Electronics, Internet of Things and Wireless Sensor Network. Internet Things (Amst.) 2020, 9, 100161. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Xue, Y.; Srivastava, G.; Dou, W. Service Offloading Oriented Edge Server Placement in Smart Farming. Softw. Pract. Exp. 2021, 51, 2540–2557. [CrossRef]

- Debauche, O.; Mahmoudi, S.; Manneback, P.; Lebeau, F. Cloud and Distributed Architectures for Data Management in Agriculture 4.0 : Review and Future Trends. J. King Saud Univ. - Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 7494–7514. [CrossRef]

- Almalki, F.A.; Soufiene, B.O.; Alsamhi, S.H.; Sakli, H. A Low-Cost Platform for Environmental Smart Farming Monitoring System Based on IoT and UAVs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5908. [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Miranda, A.; Castaño-Meneses, V.M. Internet of Things for Smart Farming and Frost Intelligent Control in Greenhouses. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 176, 105614. [CrossRef]

- Chaganti, R.; Varadarajan, V.; Gorantla, V.S.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Ravi, V. Blockchain-Based Cloud-Enabled Security Monitoring Using Internet of Things in Smart Agriculture. Future Internet 2022, 14, 250. [CrossRef]

- Pagano, A.; Croce, D.; Tinnirello, I.; Vitale, G. A survey on LoRa for smart agriculture: Current trends and future perspectives. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 3664–3679. [CrossRef]

- Jamil, F.; Ibrahim, M.; Ullah, I.; Kim, S.; Kahng, H.K.; Kim, D.-H. Optimal Smart Contract for Autonomous Greenhouse Environment Based on IoT Blockchain Network in Agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 192, 106573. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, I.; Rawat, J.; Mohd, N.; Husain, S. Opportunities of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in the Food Industry. J. Food Qual. 2021, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Glaroudis, D.; Iossifides, A.; Chatzimisios, P. Survey, Comparison and Research Challenges of IoT Application Protocols for Smart Farming. Comput. Netw. 2020, 168, 107037. [CrossRef]

- Rajak, P.; Ganguly, A.; Adhikary, S.; Bhattacharya, S. Internet of Things and Smart Sensors in Agriculture: Scopes and Challenges. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100776. [CrossRef]

- Vangala, A.; Sutrala, A.K.; Das, A.K.; Jo, M. Smart contract-based blockchain-envisioned authentication scheme for smart farming. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 10792–10806. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.H.; Zhang, X.; Xu, K.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Luo, G.; Xing, M.; Zhong, W. Self-Powered and Plant-Wearable Hydrogel as LED Power Supply and Sensor for Promoting and Monitoring Plant Growth in Smart Farming. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 422, 129499. [CrossRef]

- Codeluppi, G.; Cilfone, A.; Davoli, L.; Ferrari, G. LoRaFarM: A LoRaWAN-Based Smart Farming Modular IoT Architecture. Sensors (Basel) 2020, 20, 2028. [CrossRef]

- Nevavuori, P.; Narra, N.; Lipping, T. Crop Yield Prediction with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 163, 104859. [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Rashid, M.M.; Wibowo, S.; Xu, C.-Y.; Morshed, A.; Wasimi, S.A.; Moore, S.; Rahman, S.M. Early Weed Detection Using Image Processing and Machine Learning Techniques in an Australian Chilli Farm. Agriculture 2021, 11, 387. [CrossRef]

- Taneja, M.; Byabazaire, J.; Jalodia, N.; Davy, A.; Olariu, C.; Malone, P. Machine Learning Based Fog Computing Assisted Data-Driven Approach for Early Lameness Detection in Dairy Cattle. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 171, 105286. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.A.; Huang, N.-F. Big data and AI revolution in precision agriculture: Survey and challenges. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 110209–110222. [CrossRef]

- Raj, M.; Gupta, S.; Chamola, V.; Elhence, A.; Garg, T.; Atiquzzaman, M.; Niyato, D. A Survey on the Role of Internet of Things for Adopting and Promoting Agriculture 4.0. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2021, 187, 103107, do . [CrossRef]

- Holzinger, A.; Saranti, A.; Angerschmid, A.; Retzlaff, C.O.; Gronauer, A.; Pejakovic, V.; Medel-Jimenez, F.; Krexner, T.; Gollob, C.; Stampfer, K. Digital Transformation in Smart Farm and Forest Operations Needs Human-Centered AI: Challenges and Future Directions. Sensors (Basel) 2022, 22, 3043. [CrossRef]

- Elbasi, E.; Zaki, C.; Topcu, A.E.; Abdelbaki, W.; Zreikat, A.I.; Cina, E.; Shdefat, A.; Saker, L. Crop Prediction Model Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Appl. Sci. (Basel) 2023, 13, 9288. [CrossRef]

- Unal, Z. Smart farming becomes even smarter with deep learning—A bibliographical analysis. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 105587–105609. [CrossRef]

- Zupic, I.; Cater, T. Bibliometric Methods in Management and Organization. Org. Res. Meth. 2015, 18, 429-472. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Lim, W.M.; Kumar, S.; Donthu, N. Guidelines for advancing theory and practice through bibliometric research. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 148, 101–115. [CrossRef]

- Clarivate (2025). Web of Science. Available at: https://www.webofknowledge.com (Accessed October 17, 2025).

- Price, D.A general theory of bibliometric and other cumulative advantage processes. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. 1976, 27, 292–306. [CrossRef]

- Dobrov, G.; Randolph, R.; Rauch, W. New options for team research via international computer networks. Scientometrics 1979, 1, 387–404. [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, P. Price’s square root law: Empirical validity and relation to Lotka’s law. Inf. Process. Manag. 1988, 24, 469–477. [CrossRef]

- Bulik, S. Book use as a Bradford-Zipf phenomenon. Coll. Res. Libr. 1978, 39, 215–219. [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.; Veras, L.; Gosain, A. Using Bradford's law of scattering to identify the core journals of pediatric surgery. J. Surgical Research 2018, 229, 90-95. [CrossRef]

- Lotka, A. The frequency distribution of scientific productivity. J. Wash. Acad. Sci. 1926, 16.

- Hirsch, J.E. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 16569–16572. [CrossRef]

- Crespo, N., and Simoes, N. Publication performance through the lens of the h-index: how can we solve the problem of the ties? Soc. Sci. Q. 2019, 100, 2495–2506. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H. Knowledge management vs. data mining: Research trend, forecast and citation approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 3160–3173. [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, R.U. Growth of Literature on Bradford’s Law. Investig. Bibl. Arch. Bibliotecol. Inf. 2016, 30, 51–72, . [CrossRef]

- Garfield, E. Citation Analysis as a Tool in Journal Evaluation. Science 1972, 178, 471–479. [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N. J., and Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [CrossRef]

- Harzing, A.W.; Alakangas, S. Google Scholar, Scopus and the Web of Science: a longitudinal and cross-disciplinary comparison. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 787-804. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Quirós, L.; Ortega, J.L. Citation counts and inclusion of references in seven free-access scholarly databases: A comparative analysis. J. Inf. 2025, 19, 101618. [CrossRef]

- Asubiaro, T.; Onaolapo, S.; Mills, D. Regional disparities in Web of Science and Scopus journal coverage. Scientometrics 2024, 129, 1469–1491. [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91-108. [CrossRef]

- Armenta-Medina, D.; Ramirez-delReal, T.A.; Villanueva-Vásquez, D.; Mejia-Aguirre, C. Trends on Advanced Information and Communication Technologies for Improving Agricultural Productivities: A Bibliometric Analysis. Agronomy (Basel) 2020, 10, 1989. [CrossRef]

- Sott, M.K.; Nascimento, L. da S.; Foguesatto, C.R.; Furstenau, L.B.; Faccin, K.; Zawislak, P.A.; Mellado, B.; Kong, J.D.; Bragazzi, N.L. A Bibliometric Network Analysis of Recent Publications on Digital Agriculture to Depict Strategic Themes and Evolution Structure. Sensors (Basel) 2021, 21, 7889. [CrossRef]

- Kamran, M.; Khan, H.U.; Nisar, W.; Farooq, M.; Rehman, S.-U. Blockchain and Internet of Things: A Bibliometric Study. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2020, 81, 106525. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, M.; Kumar, P.; Singh, A. Bibliometric Review of Digital Transformation in Agriculture: Innovations, Trends and Sustainable Futures. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Patil, R.R.; Kumar, S.; Rani, R.; Agrawal, P.; Pippal, S.K. A Bibliometric and Word Cloud Analysis on the Role of the Internet of Things in Agricultural Plant Disease Detection. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2023, 6, 27. [CrossRef]

- Luque-Reyes, J.R.; Zidi, A.; Peña-Acevedo, A.; Gallardo-Cobos, R. Assessing Agri-Food Digitalization: Insights from Bibliometric and Survey Analysis in Andalusia. World 2025, 6, 57. [CrossRef]

- Kushartadi, T.; Mulyono, A.E.; Al Hamdi, A.H.; Rizki, M.A.; Sadat Faidar, M.A.; Harsanto, W.D.; Suryanegara, M.; Asvial, M. Theme Mapping and Bibliometric Analysis of Two Decades of Smart Farming. Information (Basel) 2023, 14, 396. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, M.; Gupta, D.; Tharewal, S.; Goyal, D.; Kaur Sandhu, J.; Kaur, M.; Ali Alzubi, A.; Mutared Alanazi, J. Internet of things-based smart precision farming in soilless agriculture: Opportunities and challenges for global food security. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 34238–34268. [CrossRef]

- Ragazou, K.; Garefalakis, A.; Zafeiriou, E.; Passas, I. Agriculture 5.0: A New Strategic Management Mode for a Cut Cost and an Energy Efficient Agriculture Sector. Energies 2022, 15, 3113. [CrossRef]

- Gamage, A.; Gangahagedara, R.; Subasinghe, S.; Gamage, J.; Guruge, C.; Senaratne, S.; Randika, T.; Rathnayake, C.; Hameed, Z.; Madhujith, T.; et al. Advancing Sustainability: The Impact of Emerging Technologies in Agriculture. Curr. Plant Biol. 2024, 40, 100420. [CrossRef]

- Apeh, O.O.; Nwulu, N.I. Improving Traceability and Sustainability in the Agri-Food Industry through Blockchain Technology: A Bibliometric Approach, Benefits and Challenges. Energy Nexus 2025, 17, 100388. [CrossRef]

- Hartman, K.; van der Heijden, M.G.A.; Wittwer, R.A.; Banerjee, S.; Walser, J.C.; Schlaeppi, K. Cropping practices manipulate abundance patterns of root and soil microbiome members paving the way to smart farming. Microbiome 2018, 6, 14. [CrossRef]

- Cabreira, T.M.; Brisolara, L.B.; Paulo, R.F. Survey on Coverage Path Planning with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Drones-Basel 2019, 3, 4. [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.S.; Riaz, S.; Abid, A.; Abid, K.; Naeem, MA. A Survey on the Role of IoT in Agriculture for the Implementation of Smart Farming . IEEE Access 2019, 7, 156237-156271. [CrossRef]

- Muangprathub, J.; Boonnam, N.; Kajornkasirat, S.; Lekbangpong, N.; Wanichsombat, A.; Nillaor, P. IoT and agriculture data analysis for smart farm. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 156, 467-474. [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.C.; Chilvers, J. Agriculture 4.0: Broadening Responsible Innovation in an Era of Smart Farming. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 2, 87. [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.H.; Goudos, S. Faster R-CNN for multi-class fruit detection using a robotic vision system. Comput. Netw. 2020, 168, 107036. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; De, D.; Hussain, M.I. Internet of Things (IoT) for Smart Precision Agriculture and Farming in Rural Areas. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 4890 -4899. [CrossRef]

- Wazid, M.; Das, A.K.; Odelu, V.; Kumar, N.; Conti, M.; Jo, M. Design of Secure User Authenticated Key Management Protocol for Generic IoT Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 269-282. [CrossRef]

- Finger, R; Swinton, SM; El Benni, N; Walter, A. Precision Farming at the Nexus of Agricultural Production and the Environment. In Annual Reviews of Resources Economics; Rausser, G.C.; Zilberman, D., Eds.; Annual Reviews: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2019, Volume 11, pp. 313 – 335. [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Izquierdo, M.A.; Santa, J.; Martínez, J.A.; Martínez, V.; Skarmeta, A.F. Smart farming IoT platform based on edge and cloud computing. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 177, 4-17. [CrossRef]

- Sa, I; Chen, Z.T.; Popovic, M.; Khanna, R.; Liebisch, F.; Nieto, J.; Siegwart, R. weedNet: Dense Semantic Weed Classification Using Multispectral Images and MAV for Smart Farming. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 588-595. [CrossRef]

- Jakku, E.; Taylor, B.; Fleming, A.; Mason, C.; Fielke, S.; Sounness, C.; Thorburn, P. If they don't tell us what they do with it, why would we trust them? Trust, transparency and benefit-sharing in Smart Farming. NJAS-Wagen. J. Life Sci. 2019, 90-91, 100285. [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, P.P.; Yavari, A.; Georgakopoulos, D.; Morshed, A.; Zaslavsky, A. Internet of Things Platform for Smart Farming: Experiences and Lessons Learnt. Sensors 2016, 16, 1884. [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, L.; Sanderson, J.; Zhang, A.R.; Jakku, E. Farmers and their data: An examination of farmers' reluctance to share their data through the lens of the laws impacting smart farming. NJAS-Wagen. J. Life Sci. 2019, 90-91, 100301. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.H.; Zhang, C.Y.; Qiao, Y.L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W.J.; Song, C.Q. CNN feature based graph convolutional network for weed and crop recognition in smart farming. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 174, 105450. [CrossRef]

- Saggi, M.K.; Jain, S. Reference evapotranspiration estimation and modeling of the Punjab Northern India using deep learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 156, 387-398. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Iborra, R.; Sanchez-Gomez, J.; Ballesta-Viñas, J.; Cano, M.D.; Skarmeta, A.F. Performance Evaluation of LoRa Considering Scenario Conditions. Sensors 2018, 18, 772. [CrossRef]

- Sozzi, M.; Cantalamessa, S.; Cogato, A.; Kayad, A.; Marinello, F. Automatic Bunch Detection in White Grape Varieties Using YOLOv3, YOLOv4, and YOLOv5 Deep Learning Algorithms. Agronomy-Basel 2022, 12, 319. [CrossRef]

- Subeesh, A.; Mehta, C.R. Automation and digitization of agriculture using artificial intelligence and internet of things. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2021, 5, 278-291. [CrossRef]

- Carolan, M. Automated agrifood futures: robotics, labor and the distributive politics of digital agriculture. J. Peasant Stud. 2020, 47, 184 -207. [CrossRef]

- Eastwood, C.; Klerkx, L.; Ayre, M.; Dela Rue, B. Managing Socio-Ethical Challenges in the Development of Smart Farming: From a Fragmented to a Comprehensive Approach for Responsible Research and Innovation. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2019, 32, 741-768. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Value / Sample (n) | Unit of Analysis | Subsampling criterion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time period | 1983 – 2025 | Years | Price’s Law |

| Sources analyzed | 582 | Journals / Sources | Bradford’s Law |

| Authors identified | 6244 | Researchers | Lotka’s Law |

| Documents total | 1580 | Scientific articles | Hirsch’s index (h-index) |

| Keywords Plus | 6337 | Terms | Zipf’s Law |

| Statistic | Exponential Model | Logistic (S) Model |

|---|---|---|

| R | 0.967 | 0.967 |

| R² | 0.934 | 0.935 |

| Adjusted R² | 0.927 | 0.928 |

| Std. Error of Estimate | 0.512 | 0.510 |

| F (ANOVA) | 128.279 | 129.186 |

| Sig. (ANOVA) | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Predictor Coefficient | B = 0.553 (PY) | B = -2,254,803 (1/PY) |

| Constant | 0.000 | 1120.495 |

| Dependent Variable | ln(ART)* | ln(ART)* |

| SDG | Published Articles * |

SDG | Published Articles * |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDG 1 | 5 | SDG 10 | 1 |

| SDG 2 | 447 | SDG 11 | 318 |

| SDG 3 | 472 | SDG 12 | 53 |

| SDG 4 | 12 | SDG 13 | 297 |

| SDG 5 | 1 | SDG 14 | 61 |

| SDG 6 | 27 | SDG 15 | 140 |

| SDG 7 | 40 | SDG 16 | 3 |

| SDG 8 | 2 | SDG 17 | 1 |

| SDG 9 | 47 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).