Submitted:

27 November 2025

Posted:

28 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

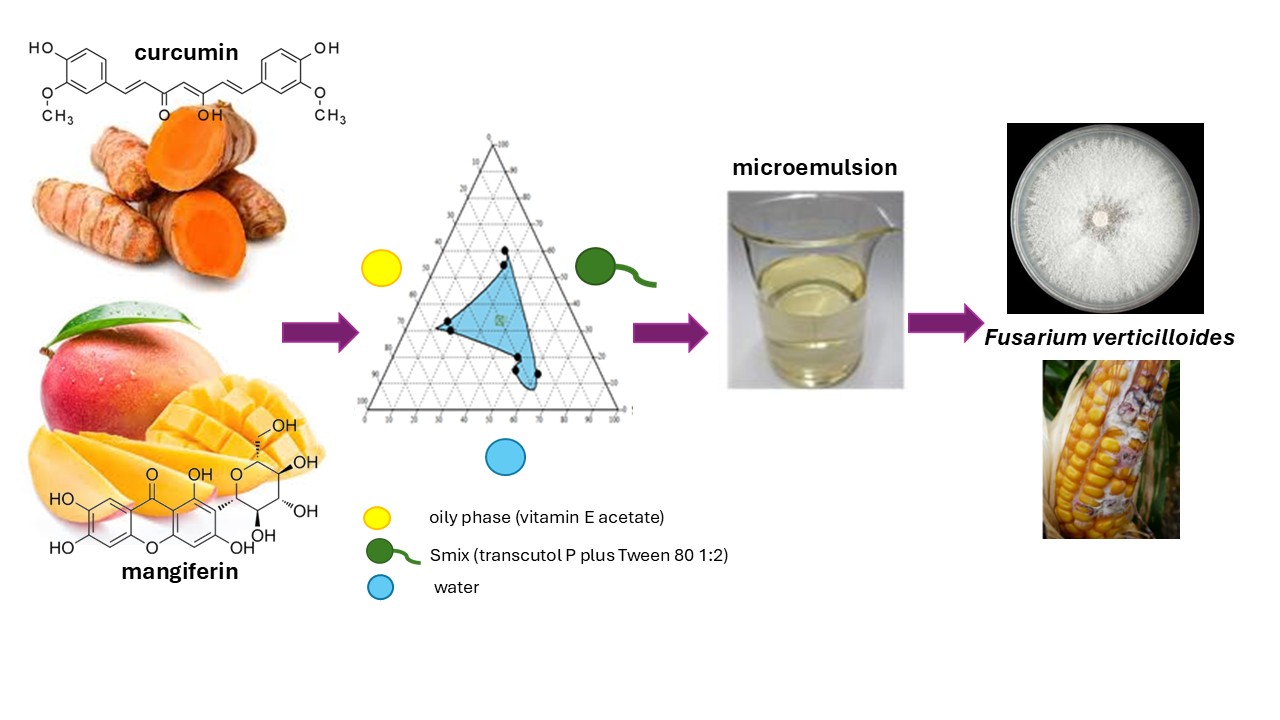

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Solvents

2.2. HPLC-DAD Analysis to Evaluate the Recovery of Curcumin and Mangiferin in Developed Microemulsions

2.3. Solubility Studies of Curcumin and Mangiferin in Different Surfactants

2.4. Development of Microemulsion

2.5. Solubilization of Curcumin and Mangiferin into Microemulsions and Chemical Characterization

2.6. Physical Characterization of the Microemulsions Loaded with Polyphenols

2.7. Antifungal Activity

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. HPLC-DAD Method

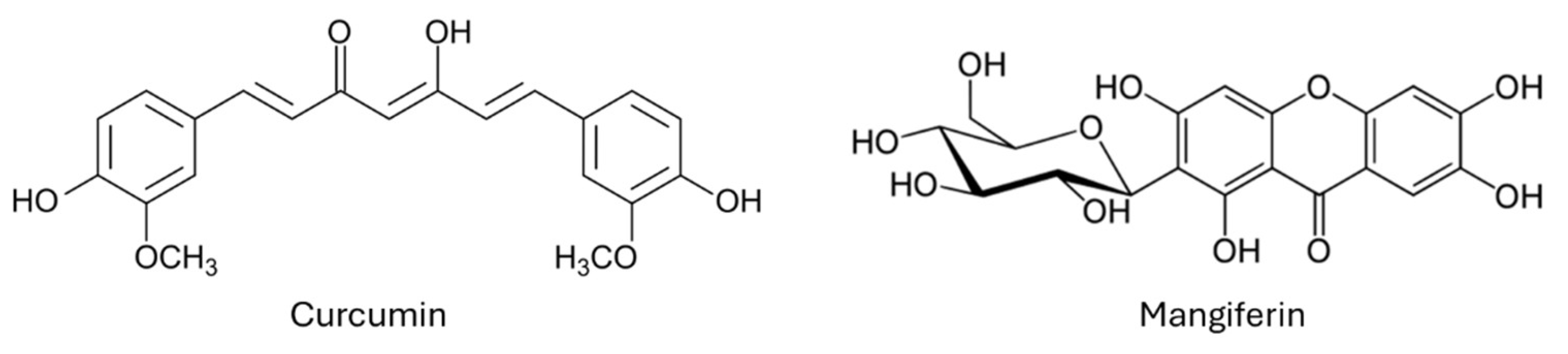

3.2. Selection of Vehicles

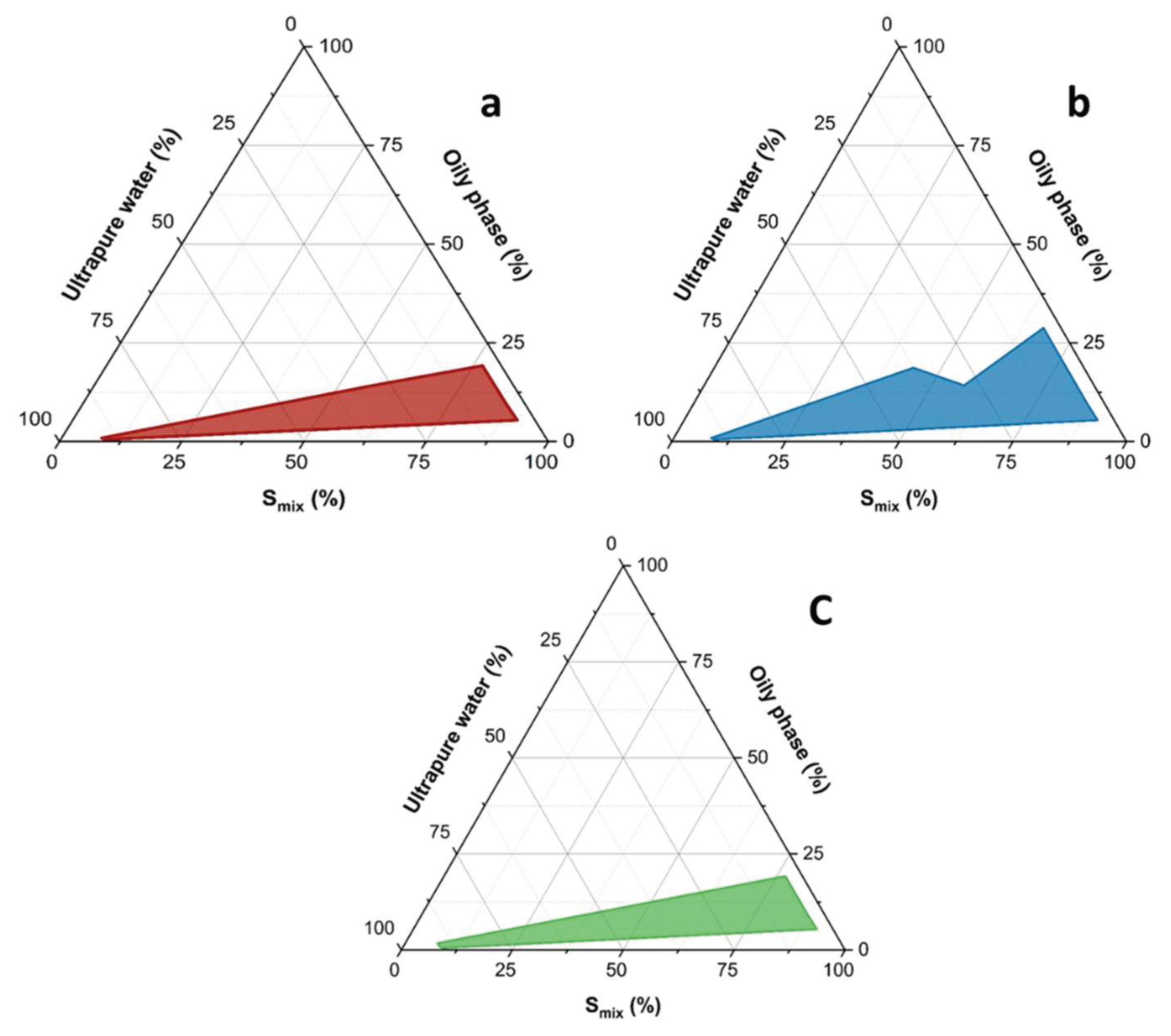

3.2. Microemulsion Development

3.3. Development of Curcumin and Mangiferin Loaded Microemulsions

3.4. Physical Characterization of Microemulsions Loaded with Polyphenols

3.5. Antifungal Activity

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmad, M.F.; Ahmad, F.A.; Alsayegh, A.A.; Zeyaullah, M.; AlShahrani, A.M.; Muzammil, K.; Saati, A.A.; Wahab, S.; Elbendary, E.Y.; Kambal, N.; Abdelrahman, M.H.; Hussain, S. Pesticides impacts on human health and the environment with their mechanisms of action and possible countermeasures. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Union, Farm to Fork Strategy. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/horizontal-topics/farm-fork-strategy_en (accessed on 2nd March 2025).

- EU Vision for Agriculture and Food 2025–2029. Available online: https://agrinfo.eu/book-of-reports/eu-vision-for-agriculture-and-food-20252029 (accessed on 23rd March 2025).

- EU Pesticide Reduction (Sustainable Use Regulation SUR). Available online: https://www.pan-europe.info/eu-legislation/eu-pesticide-reduction-sustainable-use-regulation-sur (accessed on 23rd March 2025).

- Moghadamtousi, S.Z.; Kadir, H.A.; Hassandarvish, P.; Tajik, H.; Abubakar, S.; Zandi, K.A. A review on antibacterial, antiviral, and antifungal activity of curcumin. BioMed Res Int 2014, 186864. [Google Scholar]

- Beshah, T.D.; Fekry saad, M.A.; el Gazar, S. : Farag, M.A. Curcuminoids: A multi-faceted review of green extraction methods and solubilization approaches to maximize their food and pharmaceutical applications. Adv Sample Prep 2025, 13, 100159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torquato, I.O.; Corrales, A.; Mussagy, C.U.; Pereira, J.F.B.; Lopes, A.M. Revolutionizing Curcumin Extraction: New Insights From Non-Conventional Methods-A Comparative Analysis of the Last Decade. J Sep Sci. 2025, 48, e70198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivaswamy, G.; Rudra, S.G.; Dorjee, L.; Kundu, A.; Gogoi, R.; Singh, A. Valorisation of raw mango pickle industry waste into antimicrobial agent against postharvest fungal pathogens. Curr Res Microb Sci 2024, 6, 100243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizwan, A.; Mohammed, A.; Ahmed, M.; Aljawharah, A.; Alaa, A.; Asma, A.; Leena, A.; Salem, B.; Muath, A.; Saeed, A. A novel green extraction and analysis technique for the comprehensive characterization of Mangiferin in different parts of the fresh mango fruit (Mangifera indica). LWT, 2022, 159, 113176. [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni, V.; Rathod, V. Green Process for Extraction of Mangiferin from Mangifera indica Leaves. J Biol Active Prod Nature, 2016, 6, 406–411. [Google Scholar]

- Duyen Thi My Huynh, Linh My Le, Lam Thanh Nguyen, Trung Ho Nhan Nguyen, Minh Hoang Nguyen, Khang Tran Vinh Nguyen, Khanh Quoc Tran, Trung Le Quoc Tran, Minh-Ngoc Thi Le, Huynh Nhu Ma. Investigation of acute, sub-chronic toxicity, effects of mangiferin and mangiferin solid dispersion (HPTR) on Triton WR1339-induced hyperlipidemia on Swiss albino mice. Pharmacia, 2024, 71, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Moghadamtousi, S.Z.; Kadir, H.A.; Hassandarvish, P.; Tajik, H.; Abubakar, S.; Zandi, K. A review on antibacterial, antiviral, and antifungal activity of curcumin. Biomed Res Int. 2014, 186864. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M. K.; Choi, G. J.; Lee, H. S. Fungicidal property of Curcuma longa L. rhizome-derived curcumin against phytopathogenic fungi in a greenhouse. J Agric Food Chem, 2003, 51, 1578–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radwan, M. M.; Tabanca, N.; Wedge, D. E.; Tarawneh, A. H.; Cutler, S. J. Antifungal compounds from turmeric and nutmeg with activity against plant pathogens. Fitoterapia, 2014, 99, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seididamyeh, M.; Netzel, M.E.; Mereddy, R.; Harmer, J. R.; Sultanbawa, Y. Effect of gum Arabic on antifungal photodynamic activity of curcumin against Botrytis cinerea spores. Int J Biol Macrom, 2024, 283, 137019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, P.; Zhao, Y.; Fang, J.; Yang, T.; Yang, R. Isolation and identification of Alternaria alstroemeriae causing postharvest black rot in citrus and its control using curcumin-loaded nanoliposomes. Front Microbiol, 2025, 16, 1555774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Long, L.; Zhang, F.; Chen, Q.; Chen, C.; Yu, X.; Liu, Q.; Bao, J.; Long, Z. Antifungal activity, main active components and mechanism of Curcuma longa extract against Fusarium graminearum. PLoS One, 2018, 13, e0194284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, J.; Islam, M. Z.; Takara, K.; Hossain, M. A.; Sano, A. Isolation and structural elucidation of antifungal compounds from Ryudai gold (Curcuma longa) against Fusarium solani sensu lato isolated from American manatee. Comp Biochem Phys Part C: Toxicol Pharmacol, 2019, 219, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loron, A.; Navikaitė-Šnipaitienė, V.; Rosliuk, D.; Rutkaitė, R.; Gardrat, C.; Coma, V. Polysaccharide Matrices for the Encapsulation of Tetrahydrocurcumin-Potential Application as Biopesticide against Fusarium graminearum. Molecules, 2021, 26, 3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ediriweera, M. K.; Tennekoon, K. H.; Samarakoon, S. R. A review on ethnopharmacological applications, pharmacological activities, and bioactive compounds of Mangifera indica (Mango). Evid-Based Compl Altern Med 2017, 6949835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehia, R. S.; Altwaim, S. A. An insight into in vitro antioxidant, antimicrobial, cytotoxic, and apoptosis induction potential of mangiferin, a bioactive compound derived from Mangifera indica. Plants, 2023, 12, 1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shivaswamy, G.; Rudra, S.G.; Dorjee, L.; Kundu, A.; Gogoi, R.; Singh, A. Valorisation of raw mango pickle industry waste into antimicrobial agent against postharvest fungal pathogens. Curr Res Microb Sci 2024, 6, 100243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.S.; Nazeer, M.; Abd El-Gawad, H.H.; Inam, M.; Ibrahim, M.M.; El-Bahy, Z.M.; Nazar, M.F. Microemulsions as potential pesticidal carriers: A review. J Molec Liquids, 2023, 390, 122969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICH. International Conference on Harmonisation, in Q2(R1) 2005. Validation of analytical procedures: text and methodology. Geneva: Geneva.

- European Medicines Agency. EMA Guidelines 2012, 44, 1–23.

- Vanti, G.; Micheli, L.; Di Cesare Mannelli, L.; Manera, C.; Sestito, S.; Bergonzi, M.C.; Rapposelli, S.; Ghelardini, C.; Bilia, A.R. Efficacy of memantine prodrug microemulsion in a Preclinical model of tendinopathy. Int J Pharm, 2025, 681, 125823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifoni, L.; De Donno, G.; Vanti, G.; Bergonzi, M.C.; Tan, L.; Luceri, C.; Bilia, A.R. Development, characterization and in vitro assessment of a novel self-microemulsifying drug delivery system to increase cannabidiol intestinal bioaccessibility. Int J Pharm, 2025, 685, 126284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanti, G.; Micheli, L.; Berrino, E.; Di Cesare Mannelli, L.; Bogani, I.; Carta, F.; Bergonzi, M.C.; Supuran, C.T.; Ghelardini, C.; Bilia, A.R. Escinosome thermosensitive gel optimizes efficacy of CAI-CORM in a rat model of rheumatoid arthritis. J Control Release, 2023, 358, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grifoni, L.; Landucci, E.; Pieraccini, G.; Mazzantini, C.; Bergonzi, M.C.; Pellegrini-Giampietro, D.E.; Bilia, A.R. Development and Blood-Brain Barrier Penetration of Nanovesicles Loaded with Cannabidiol. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacco, C.; Donato, R.; Zanella, B.; Pini, G.; Pettini, L.; Marino, M. F.; Rookmin, A.D.; Marvasi, M. Mycotoxins and flours: Effect of type of crop, organic production, packaging type on the recovery of fungal genus and mycotoxins. Int J Food Microbiol, 2020, 334, 108808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Chemicals Agency, Performance Criteria Overview of (EN) Standards, Test Conditions, and Pass Criteria. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/20733977/overview_of_standards_test_conditions_pass_criteria_en.pdf/ f728e5c1-afd6-4c25-8cc3-ca300cd9b1cf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Grifoni, L.; Sacco, C.; Donato, R.; Tziakas, S.; Tomou, E.M.; Skaltsa, H.; Vanti, G.; Bergonzi, M.C.; Bilia, A. R. Environmentally friendly microemulsions of essential oils of Artemisia annua and Salvia fruticosa to protect crops against Fusarium verticillioides. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Vitamin E Exemption from Tolerance Requirements in Pesticide Formulations, Environmental Protection Agency. United States of America. 2008. Available online: https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/9vbht8 (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Gattefossè. Available online: https://www.pharmaexcipients.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Brochure-Transcutol-P-for-efficient-skin-penetration.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Abd Sisak, M.A.; Daik, R.; Ramli, S. Study on the effect of oil phase and co-surfactant on microemulsion systems. Malays J Anal Scie 2017, 21, 1409–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Pratap, A.P.; Bhowmick, D.N. Pesticides as Microemulsion Formulations. J Disp Scie Techn, 2008, 29, 1325–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Surfactant (HLB) |

Curcumin solubility |

Mangiferin Solubility |

|---|---|---|

| Tween 20 (16.7) | 8mg/ml | 26 mg/ml |

| Tween 80 (15.0) | 30 mg/ml | 36 mg/ml |

| Tween 60 (14.9) | 13 mg/ml | 31 mg/ml |

| Transcutol P (4.2) | 95 mg/ml | 29 mg/ml |

| Labrasol (12) | 15 mg/ml | 23 mg/ml |

| Water | 0.1 mg/ml | 0.8 mg/ml |

| ME | Vitamin E acetate (% v/v) |

Transcutol P (% v/v) | Tween 80 (% v/v) |

Water (% v/v) |

Curcumin (% w/v) |

Mangiferin (% w/v) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CU-ME | 10 | 10 | 20 | 60.0 | 0.5 | |

| MA-ME | 10 | 10 | 20 | 60.0 | 0.5 |

| Empty-ME | MA-ME | SEO-ME | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size (nm) | 95.2±10.3 nm | 121.7±29.2 nm | 172.6±19.3 nm |

| Polidispersity Index | 0.100±0.009 | 0.280±0.010 and | 0.299±0.009 |

| F. verticilloides | Tested curcumin concentration (mg) | ||||||||||||

| 2.4x105 (ufc/20μL) | 3.62 | 3.26 | 2.90 | 2.53 | 2.17 | 1.81 | |||||||

| Log reduction | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | |||||||

| F. verticilloides | Tested mangiferin concentration (mg) | ||||||||||||

| 2.4x105 (ufc/20μL) | 3.71 | 3.34 | 2.97 | 2.60 | 2.23 | 1.86 | |||||||

| Log reduction | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | |||||||

| F. verticilloides | Curcumin concentration in CU-ME (mg) | ||||

| 8.8x104 (ufc/20μL) | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | |

| Log reduction | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | |

| F. verticilloides | Mangiferin concentration in MA-ME (mg) | ||||

| 8.8x104 (ufc/20μL) | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | |

| Log reduction | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).