3.1. Synthesis and Characterization

Our work determined that the ethanolic extract of taperebá peels exhibits a remarkable total polyphenol content, corresponding to 2623 mg of gallic acid equivalents (EAG) per liter of fresh peel extract, which was subsequently utilized in the development of lipid nanostructures. The antioxidant capacity of this extract was rigorously evaluated using both DPPH and ABTS assays, yielding values of 258 mM TEAC and 495 mM TEAC per 100 mL of peel extract, respectively.

Complementary to these findings, previous investigations by our group employed UPLC-MS/MS to chemically characterize and quantify a diverse array of phenolic compounds in the peels of

Spondias mombin. This comprehensive profiling revealed a substantial polyphenolic content, notably high in ellagic acid and quercetin, and marked the first successful identification and quantification of certain compounds within the

Spondias genus [

7]. In detail, the UPLC-MS/MS analysis enabled the quantification of several classes of phenolic compounds, including flavonols, phenylpropanoids, benzoic acid derivatives, coumarins, stilbenes, dihydrochalcones, flavones, and flavanones (

Table 1).

Within the flavonol category, 14 distinct compounds were quantified, with quercetin being the most abundant, followed by myricetin and kaempferol-3-glucoside; noteworthy levels of syringetin and isorhamnetin-3-glucoside were also observed. The phenylpropanoid group was represented by cinnamic acid and its derivatives—encompassing various hydroxycinnamic acids and sinapyl alcohol—with chlorogenic acid present in the highest concentration, followed by p-coumaric and cinnamic acids. Among the benzoic acid derivatives, ellagic acid predominated over gallic acid in the taperebá peel extract. Additionally, the coumarin esculin was prominently detected, while among the stilbenes, cis-piceid was quantified at notably high levels, accompanied by significant amounts of trans-piceid and trans-resveratrol. The flavone fraction was characterized by the predominance of sinensetin and luteolin-7-O-glucoside, and the analysis further identified glycosylated hydroquinone (arbutin) [

7].

In the quantitative analysis presented in

Table 1, the phenolic composition of the extract reveals a pronounced heterogeneity across several compound classes. Among the benzoic acid derivatives, ellagic acid exhibits an exceptionally high concentration, followed by gallic acid and cinnamic acid, underscoring their potential pivotal role in mediating the extract’s antioxidant properties. Within the coumarin group, esculin is notably predominant.The phenylpropanoid fraction is characterized by a high level of chlorogenic acid, with p-coumaric acid and sinapyl alcohol further enhancing the spectrum of bioactive compounds. Notably, the stilbene category is distinguished by a substantial amount of cis-piceid, which contrasts with the lower concentrations of trans-piceid and trans-resveratrol, potentially indicating isomer-specific functional differences. The flavonoid spectrum is further diversified, with flavones like sinensetin and luteolin-7-O-glucoside and the flavanone naringenin playing notable roles. The flavonol group is particularly prominent, with quercetin and myricetin dominating the profile, complemented by significant levels of kaempferol-3-O-glucoside and isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside, while additional compounds such as rutin and syringetin further contribute to the complexity. Moreover, the detection of arbutin as a hydroquinone derivative introduces an additional bioactive moiety to the extract. Collectively, these data illustrate a rich and diverse phenolic profile that is likely to underpin the extract’s multifaceted biological activities, thereby supporting its potential application in advanced therapeutic and cosmetic formulations [

7].

This integrated characterization not only underscores the rich and diverse polyphenolic profile of taperebá peels but also highlights the extract’s potent antioxidant capacity and its potential applicability in the design of bioactive nanostructured lipid systems. Such findings pave the way for further exploration into the utilization of natural phenolic compounds in advanced material and pharmaceutical applications [

7].

Table 1.

Quantification of metabolites from taperebá peel (µg/g) by UPLC-MS/MS Table adapted from De Brito et al. [

7].

Table 1.

Quantification of metabolites from taperebá peel (µg/g) by UPLC-MS/MS Table adapted from De Brito et al. [

7].

| Category |

Compound |

Concentration (µg/g) |

| Benzoic acid derivatives |

2,5-Dihydroxybenzoic acid |

0.102 ± 0.090 |

| Benzoic acid derivatives |

Cinnamic acid |

1.254 ± 0.040 |

| Benzoic acid derivatives |

Ellagic acid |

79.080 ± 3.272 |

| Benzoic acid derivatives |

Gallic acid |

21.994 ± 0.361 |

| Benzoic acid derivatives |

Methyl anthranilate |

0.003 ± 0.002 |

| Benzoic acid derivatives |

Methyl gallate |

0.031 ± 0.010 |

| Benzoic acid derivatives |

Syringaldehyde |

0.136 ± 0.053 |

| Benzoic acid derivatives |

Vanillic acid |

0.006 ± 0.003 |

| Benzoic acid derivatives |

Vanillin |

0.869 ± 0.080 |

| Coumarins |

Daphnetin |

0.377 ± 0.121 |

| Coumarins |

Esculin |

4.016 ± 0.371 |

| Coumarins |

Fraxin |

0.088 ± 0.030 |

| Coumarins |

Scopoletin |

0.382 ± 0.161 |

| Phenylpropanoids |

Caffeic acid |

0.239 ± 0.031 |

| Phenylpropanoids |

Chlorogenic acid |

10.236 ± 0.211 |

| Phenylpropanoids |

Cryptochlorogenic acid |

0.141 ± 0.012 |

| Phenylpropanoids |

Ferulic acid |

0.163 ± 0.025 |

| Phenylpropanoids |

Neochlorogenic acid |

0.129 ± 0.011 |

| Phenylpropanoids |

p-Coumaric acid |

1.868 ± 0.211 |

| Phenylpropanoids |

Sinapyl alcohol |

1.142 ± 0.042 |

| Phenylpropanoids |

trans-Coutaric acid |

0.036 ± 0.031 |

| Stilbenes |

cis-Piceid |

21.106 ± 1.330 |

| Stilbenes |

trans-Piceid |

3.577 ± 0.181 |

| Stilbenes |

trans-Resveratrol |

0.650 ± 0.022 |

| Dihydrochalcones |

Phloretin |

0.017 ± 0.004 |

| Dihydrochalcones |

Phloridzin |

0.215 ± 0.041 |

| Dihydrochalcones |

Trilobatin |

0.051 ± 0.011 |

| Flavones |

Apigenin |

0.035 ± 0.011 |

| Flavones |

Hesperidin |

0.129 ± 0.071 |

| Flavones |

Luteolin |

0.214 ± 0.011 |

| Flavones |

Luteolin-7-O-Glucoside |

1.185 ± 0.081 |

| Flavones |

Sinensetin |

1.453 ± 0.031 |

| Flavanones |

Naringenin |

1.037 ± 0.061 |

| Flavonols |

Isorhamnetin |

0.769 ± 0.051 |

| Flavonols |

Isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside |

1.788 ± 0.081 |

| Flavonols |

Kaempferol |

0.374 ± 0.061 |

| Flavonols |

Kaempferol-3-O-glucoside |

2.997 ± 0.091 |

| Flavonols |

Kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside |

0.089 ± 0.011 |

| Flavonols |

Myricetin |

8.137 ± 0.141 |

| Flavonols |

Quercetin |

66.402 ± 1.131 |

| Flavonols |

Quercetin-3-Glc-Ara |

0.065 ± 0.021 |

| Flavonols |

Quercetin-3-O-glucuronide |

0.078 ± 0.021 |

| Flavonols |

Quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside |

0.305 ± 0.041 |

| Flavonols |

Rhamnetin |

0.150 ± 0.071 |

| Flavonols |

Rutin |

1.326 ± 0.081 |

| Flavonols |

Syringetin |

1.811 ± 0.051 |

| Flavonols |

Syringetin-3-O-glucoside |

0.023 ± 0.011 |

| Hydroquinone derivative |

Arbutin |

1.279 ± 0.071 |

Design of NLC’s

Prior to the formulation of NLCs, the extract was concentrated using a rotary evaporator to reduce its volume and increase the concentration of bioactive compounds, thereby facilitating its subsequent incorporation into the nanoparticles. After concentration, the extract exhibited physical characteristics that made direct dissolution in water or conventional solvents challenging. To address this limitation, the concentrated extract was diluted in a pre-heated NaDES solvent, enabling more efficient incorporation into the lipid phase. As reported in the literature, NaDES are known for their ability to solubilize phenolic compounds from natural extracts [

20].

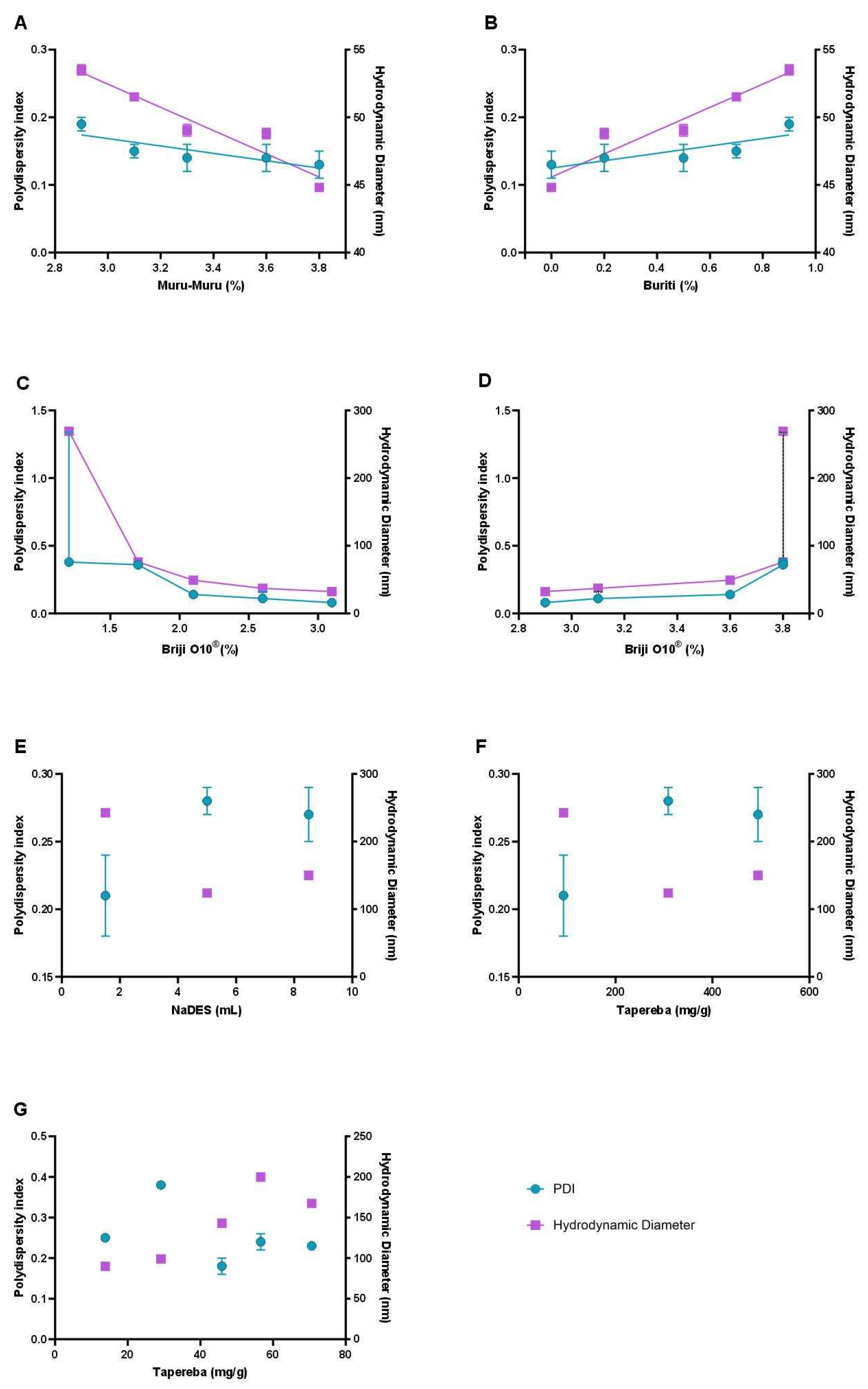

The NLC formulations were comprehensively evaluated using macroscopic analysis and detailed colloidal characterization, focusing on the influence of key variables such as lipid composition, surfactant concentration, extract content, and the incorporation of NaDES containing the extract (

Figure 2). Colloidal properties analyzed included the polydispersity index (PDI) and particle size, measured as the hydrodynamic diameter (HD). The PDI, ranging from 0 to 1, serves as an indicator of the uniformity in nanoparticle size distribution, with values closer to 0 signifying a more homogeneous system [

31]. Particle size was precisely determined in nanometers (nm) using hydrodynamic measurements, providing a reliable metric for assessing the stability and scalability of the formulations.

Figure 2.

Influence of formulation parameters on the colloidal properties of Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs). The graphs illustrate the effect of key variables, including murumuru butter percentage (A), buriti oil percentage (B), surfactant (Brij® O10) concentration in different ranges (C and D), NaDES volume (E), and Spondias mombin extract concentration in NaDES (F and G) on the polydispersity index (PDI) and hydrodynamic diameter (HD).

Figure 2.

Influence of formulation parameters on the colloidal properties of Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs). The graphs illustrate the effect of key variables, including murumuru butter percentage (A), buriti oil percentage (B), surfactant (Brij® O10) concentration in different ranges (C and D), NaDES volume (E), and Spondias mombin extract concentration in NaDES (F and G) on the polydispersity index (PDI) and hydrodynamic diameter (HD).

Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs) represent the second generation of lipid nanoparticles and are systems for encapsulating drugs and active compounds, with a core structure formed by the combination of solid and liquid lipids at room temperature, stabilized by a surfactant layer. This characteristic provides the NLCs with greater fluidity in the lipid matrix, resulting in enhanced solubilization and stabilization of active compounds, as well as enabling their controlled release [

32].

In this context, the formulation process for NLCs involves a careful selection of solid and liquid lipids to ensure the creation of small-sized, homogeneous particles. In this context, murumuru butter was selected as the solid lipid due to its high thermal stability and capacity to form crystalline lipid matrices, which are crucial for maintaining the structural integrity of the nanoparticles during storage and application [

33,

34].

The inclusion of buriti oil as the liquid lipid serves to enhance fluidity and improve the stability of the nanoparticles. Buriti oil is rich in monounsaturated fatty acids and antioxidants, such as tocopherols, which contribute to its stability and nutritional value [

35,

36]. The optimal ratio of murumuru butter to buriti oil is determined through systematic experiments that assess various parameters, including the polydispersity index (PDI), hydrodynamic diameter, and visual stability of the emulsions. Studies have shown that combinations with lower proportions of buriti oil and higher amounts of murumuru butter yield smaller and more stable particles, as indicated by PDI values remaining below 0.25, which is a benchmark for good emulsion stability.

The stability of emulsions is significantly influenced by the viscosity associated with the concentration of the dispersed phase, where higher viscosity can lead to improved stability [

37]. Furthermore, the fatty acid profile of buriti oil, which includes a high content of oleic acid, contributes to its effectiveness in stabilizing emulsions and enhancing the overall performance of the NLCs [

38,

39]. The presence of antioxidants in buriti oil not only aids in the stability of the nanoparticles but also provides additional health benefits, making it a suitable candidate for various applications, including drug delivery systems [

40]. These findings from systematic experiments underscore the importance of lipid selection and formulation parameters in achieving desirable characteristics in NLCs.

The integration of surfactants, such as Brij® O10, was also critical for stabilizing the NLCs. This nonionic surfactant was selected for its compatibility with biological systems and low toxicity, essential features for health applications. Surfactant concentrations were adjusted to minimize toxicity without compromising colloidal stability. Analysis of the results revealed that lower surfactant levels increased particle size and PDI, indicating greater heterogeneity, whereas intermediate concentrations produced more uniform and stable particles.

A major innovation of this study was the incorporation of natural deep eutectic solvents (NaDES) into the formulation of nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs). Composed of glycerol, choline chloride, and citric acid, NaDES were employed as a sustainable and biocompatible alternative to traditional solvents [

41,

42]. Beyond enhancing the solubility of phenolic compounds extracted from

Spondias mombin peel, NaDES contributed significantly to nanoparticle stabilization. This dual role was evidenced through improved colloidal stability and validated by infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), highlighting robust molecular interactions and protective effects that will be further detailed in subsequent sections [

43,

44].

Another pivotal aspect of the NLC development was the production method, which utilized hot emulsification followed by rapid cooling. This approach ensured the solidification of the lipid matrix, leading to the formation of nanoparticles with homogeneous sizes while effectively encapsulating phenolic compounds in a protective environment [

45]. Key variables in the process, including extract concentration and NaDES percentage, significantly influenced the final properties of the NLCs [

46]. Results demonstrated that higher emulsification temperatures (~80 °C) enhanced dispersion and reduced particle size in certain formulations. However, lower temperatures (~70 °C) were more appropriate for formulations containing NaDES, accommodating the thermal sensitivity of these solvents and ensuring optimal nanoparticle stability [

47,

48].

The physicochemical characterization of the NLCs was another strength of the study. Zeta potential analyses demonstrated that the particles exhibited negative surface charges, promoting greater colloidal stability through electrostatic repulsion. Below, in

Table 2, are the parameters of the final formulation with and without NaDES (NLC-TAP-NaDES), which were defined as the main formulations used in this study. These data provide a comprehensive overview of the physicochemical and structural characteristics that underpin the functional properties of each formulation, enabling detailed comparisons and highlighting the effects of NaDES presence on the systems analyzed.

Table 2.

Physicochemical properties of Nanostructured Lipid Carrier (NLC) formulations, including polydispersity index (PDI), hydrodynamic diameter (HD), zeta potential (ZP), total phenolic content (TP), and encapsulation efficiency (EE%).

Table 2.

Physicochemical properties of Nanostructured Lipid Carrier (NLC) formulations, including polydispersity index (PDI), hydrodynamic diameter (HD), zeta potential (ZP), total phenolic content (TP), and encapsulation efficiency (EE%).

| Formulation |

PDI |

HD (nm) |

ZP (mV) |

TP (mg GAE/mL NLC) |

EE% |

| NLC-Blank |

0.14 ± 0.02 |

46.71 ± 0.20 |

-19.39 ± 0.76 |

- |

- |

| NLC-NaDES |

0.26 ± 0.02 |

196.73 ± 2.37 |

-2.83 ± 0.27 |

- |

- |

| NLC-TAP |

0.23 ± 0.01 |

199.13 ± 0.91 |

-4.31 ± 0.16 |

27.05 ± 0.97 |

83,95 |

| NLC-TAP-NaDES |

0.21 ± 0.03 |

159.00 ± 0.66 |

-2.35 ± 0.35 |

20.64 ± 0.58 |

85,81 |

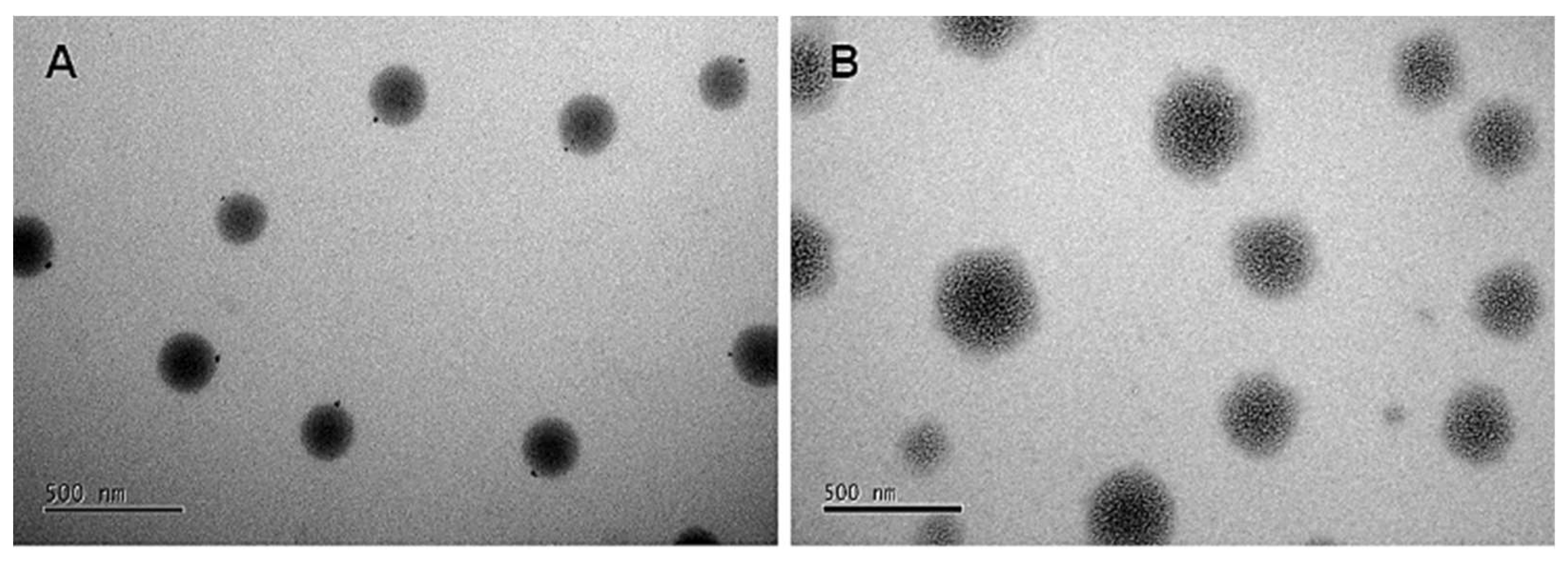

Nanoparticles (NPs) Morphology

The microscopic images in

Figure 4 illustrate the morphology of NLCs without NaDES (

Figure 4A) and with NaDES (

Figure 4B). Both formulations exhibit a spherical shape, but

Figure 4A displays a more organized structure, while Figure 3B reveals a diffuse morphology, likely influenced by NaDES. This suggests that NaDES interferes with the formation of lipid crystals, leading to structural disorganization.

These morphological differences provide critical insights into the impact of NaDES on particle structure. Further evidence supporting this phenomenon, such as FTIR analyses showing reduced C-H band intensities in NaDES-containing formulations, will be discussed in detail later in this study.

Figure 4.

Photomicrograph obtained by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) for the taperebá pell extract encapsulated in NLCs. (A) NLC without NaDES (NLC-TAP); and (B) NLC with NaDES (NLC-TAP-NaDES).

Figure 4.

Photomicrograph obtained by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) for the taperebá pell extract encapsulated in NLCs. (A) NLC without NaDES (NLC-TAP); and (B) NLC with NaDES (NLC-TAP-NaDES).

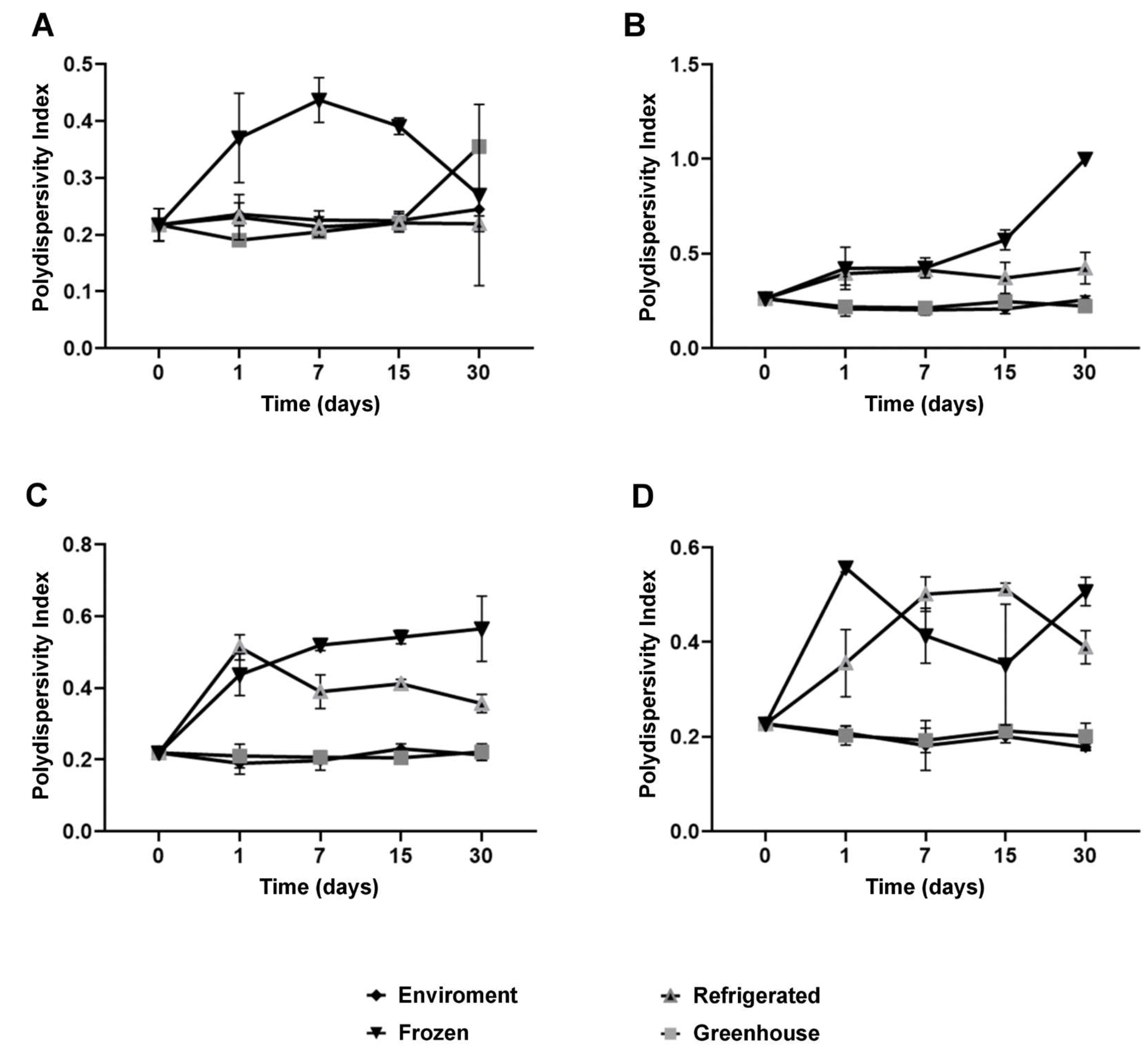

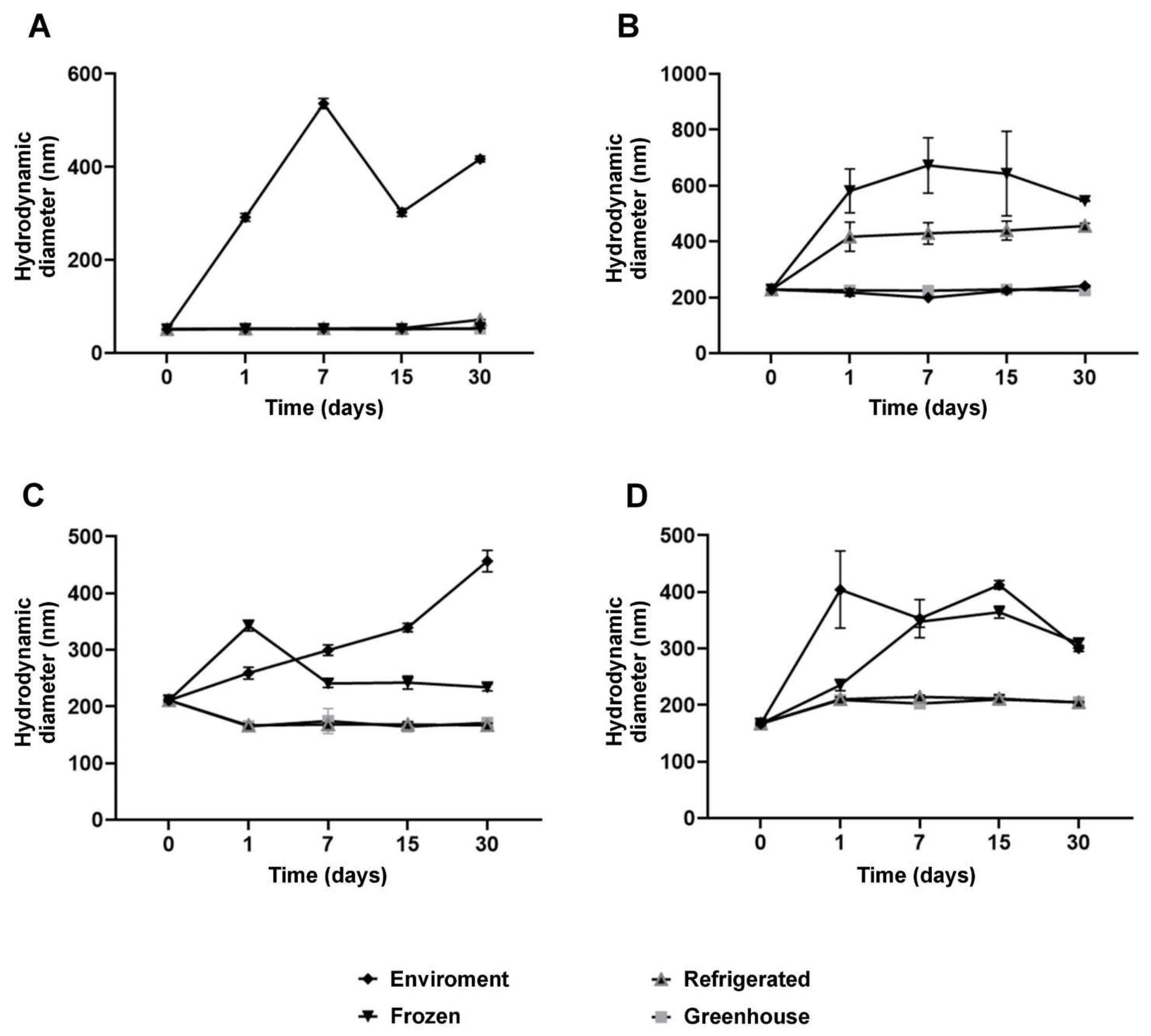

Colloidal Stability

Colloidal stability is a critical parameter for the performance of nanostructured systems, and the results of this study emphasize the pivotal role of NaDES in this context [

32]. The polydispersity index (PDI), a key indicator of the homogeneity in particle size distribution, remained below 0.25 for most formulations under ambient and refrigerated conditions for up to 30 days (

Figure 5). This indicates that the nanoparticles maintained high uniformity, essential for physical and functional stability.

Figure 5.

Polydispersity index (PDI) for each formulation stored at different temperature conditions over 30 days: NLC-Blank (A), NLC-NaDES (B), NLC-TAP-NaDESn (C), and NLC-TAP (D). Results are expressed as means of triplicates.

Figure 5.

Polydispersity index (PDI) for each formulation stored at different temperature conditions over 30 days: NLC-Blank (A), NLC-NaDES (B), NLC-TAP-NaDESn (C), and NLC-TAP (D). Results are expressed as means of triplicates.

Colloidal stability assays over time showed that NaDES-containing formulations maintained consistent particle sizes and PDI values under ambient and refrigerated conditions for up to 30 days. Under thermal stress (~40 °C), NaDES formulations outperformed their non-NaDES counterparts, highlighting their efficacy in preserving nanoparticle integrity and bioactive retention.

In summary, the development of NLCs in this study demonstrates a high degree of innovation, from component selection to the application of advanced production and characterization methodologies. The combinations of lipids, surfactants, and NaDES were optimized to maximize encapsulation efficiency, stability, and functionality of the nanoparticles. These advances pave the way for the application of NLCs in various fields, including nutraceuticals, pharmaceuticals, and cosmeceuticals, while representing a milestone in the sustainable utilization of agricultural byproducts in cutting-edge technologies.

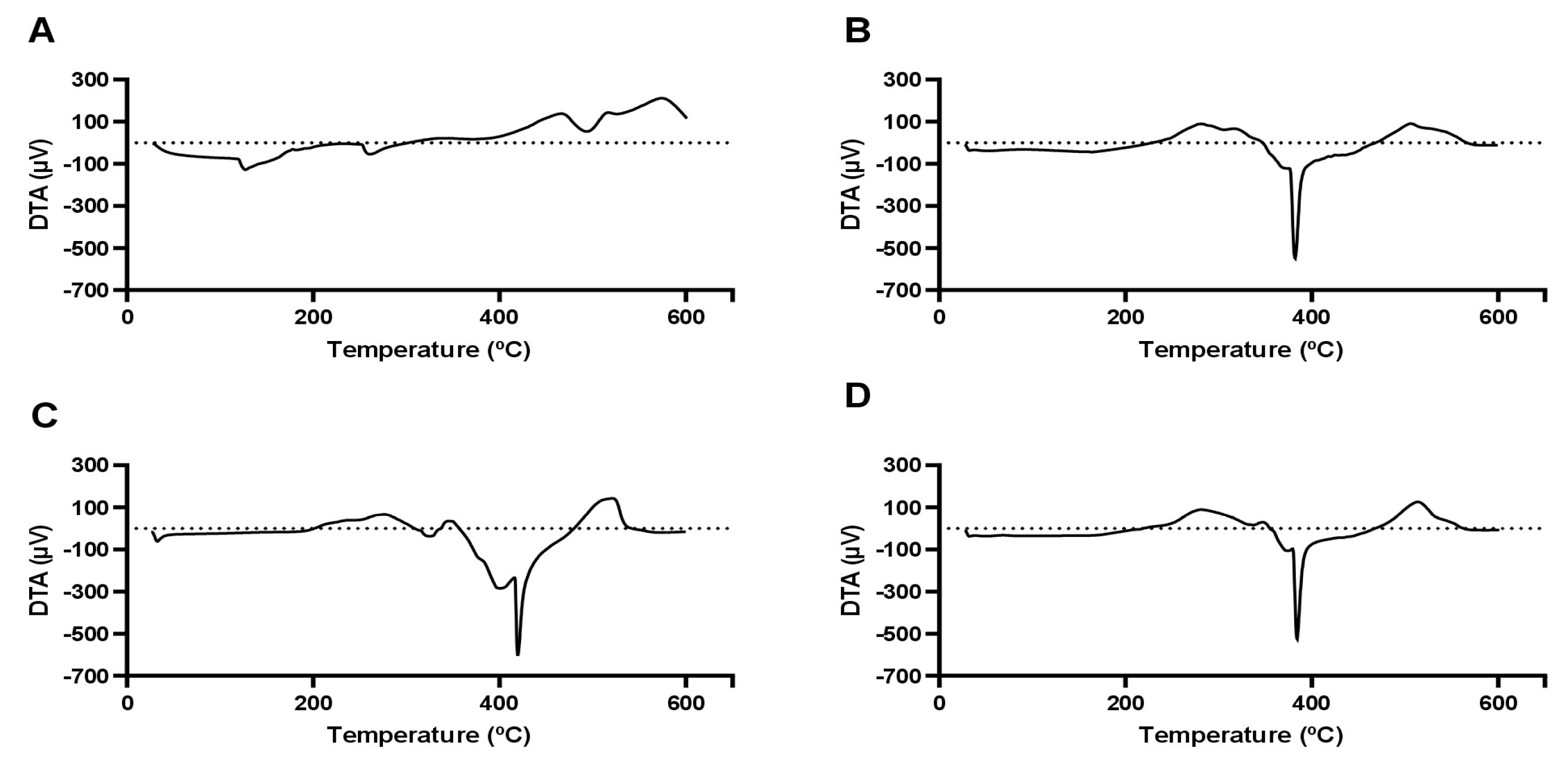

Measurements of hydrodynamic diameter further reinforced the stabilizing effects of NaDES. While formulations without NaDES exhibited minimal size variations, NaDES-containing formulations demonstrated enhanced structural flexibility, observed through moderate size increases under thermal stress and freezing conditions (

Figure 6). This behavior suggests that NaDES modulates the lipid matrix, promoting greater thermal and functional stability.

Figure 6.

Hydrodynamic diameter (HD) size of the nanoparticle for each formulation stored at different temperature conditions over 30 days: NLC-Blank (A), NLC-NaDES (B), NLC-TAP-NaDES (C), and NLC-TAP (D). Results are expressed as means of triplicates

Figure 6.

Hydrodynamic diameter (HD) size of the nanoparticle for each formulation stored at different temperature conditions over 30 days: NLC-Blank (A), NLC-NaDES (B), NLC-TAP-NaDES (C), and NLC-TAP (D). Results are expressed as means of triplicates

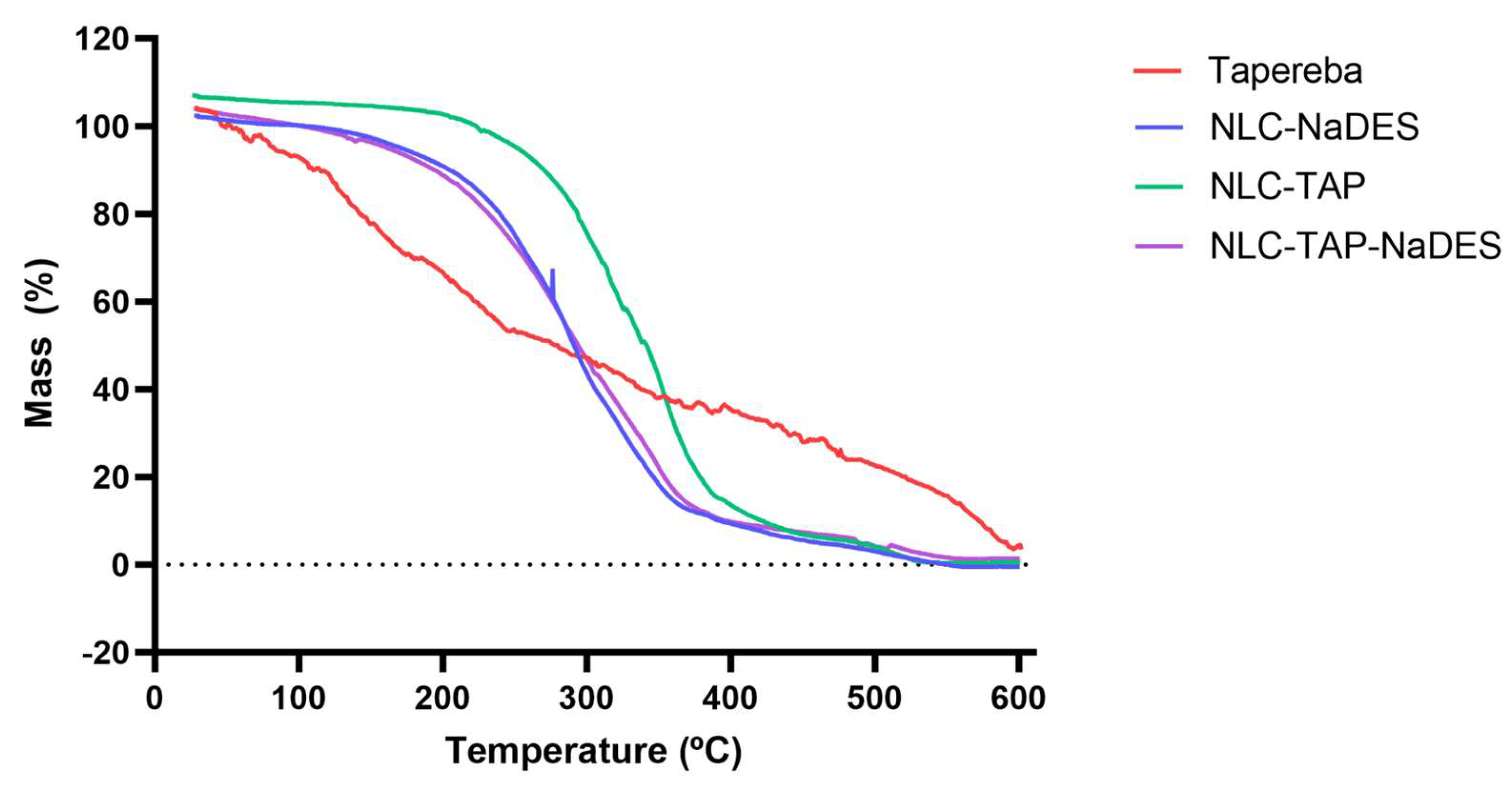

Differential thermal analysis (DTA) and Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

In the DTA curves shown in

Figure 7(A), it is possible to observe 3 endothermic events (127.27 °C, 260.70 °C, and 493.81 °C) and an exothermic event at 574.15 °C, which may be associated with the melting points of some components of the extract already quantified by this research group [

7]. According to these quantification results, the taperebá peel extract contains several phenolic compounds, notably ellagic acid, quercetin, gallic acid and cis-Piceid [

49].

Figure 7.

Differential thermal analysis (DTA) curves. (A) Tapereba extract; (B) NLC-NaDES; (C) NLC-TAP; (D) NLC-TAP-NaDES.

Figure 7.

Differential thermal analysis (DTA) curves. (A) Tapereba extract; (B) NLC-NaDES; (C) NLC-TAP; (D) NLC-TAP-NaDES.

The other curves shown in

Figure 7B and D represent an endothermic event around 380 °C, which shifts to higher values when NaDES is not used. This result demonstrates that NaDES enhances the dispersibility of the nanocarrier components, yielding a material with amorphous characteristics that are ideal for drug delivery systems [

1]. This behavior is observed in the mass loss curves shown in

Figure 8, indicating the influence of NaDES on thermal stability.

The thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) graph (

Figure 8) illustrates the mass loss of different formulations of nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) and the pure taperebá extract as a function of temperature. The y-axis represents mass loss (%), indicating thermal degradation, while the x-axis represents temperature (°C), ranging from 0 to 600°C. The curves correspond to different samples: Taperebá extract (red), NLC-NaDES (blue), NLC-TAP (green), and NLC-TAP-NaDES (purple).

The pure taperebá extract (red) exhibits the earliest degradation, with mass loss beginning at approximately 100–150°C and a significant decomposition phase extending up to 400°C. This indicates the volatilization and thermal breakdown of bioactive phenolic compounds present in the extract.

The formulations containing NaDES (NLC-NaDES in blue and NLC-TAP-NaDES in purple) display higher thermal stability, with delayed mass loss compared to the pure extract. Degradation occurs primarily between 200–400°C, suggesting that NaDES plays a protective role in reducing the volatility of bioactive molecules and stabilizing the lipid matrix at elevated temperatures.

The NLC-TAP formulation (green), which lacks NaDES, shows a slightly delayed decomposition compared to the pure extract, initiating at around 150–200°C. However, its degradation occurs more rapidly than in NaDES-containing formulations, reinforcing the hypothesis that NaDES contributes to enhanced thermal stability.

The investigation into the thermal stability of various formulations reveals significant insights regarding the efficacy of nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) compared to pure extracts. Specifically, pure extracts exhibit lower thermal stability, which can be attributed to their unprotected nature against thermal degradation. In contrast, NLC formulations demonstrate improved thermal resistance, which is critical for maintaining the integrity of bioactive compounds during processing and storage [

50] . Among the NLC formulations, those incorporating natural deep eutectic solvents (NaDES) show enhanced thermal protection. This stability is likely due to favorable molecular interactions between NaDES and the lipid matrix, which effectively minimize premature volatilization of the active ingredients. Such interactions are crucial as they protect the bioactive compounds from thermal degradation and enhance their retention within the lipid matrix [

51]. The presence of NaDES can alter the physicochemical properties of the lipid carriers, leading to improved encapsulation efficiency and stability under thermal stress [

52]. The findings underscore the potential applications of NLC-NaDES systems across various fields, including pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and nutraceuticals. The improved stability and bioactive retention offered by these formulations make them suitable for thermal processing, which is often a requisite in the production of food and cosmetic products [

53]. The ability of NLCs to withstand thermal degradation while preserving bioactive compounds positions them as a promising delivery system, ensuring that the therapeutic efficacy of the encapsulated agents is maintained even under challenging conditions [

52,

54]. In conclusion, the integration of NaDES into NLC formulations not only enhances thermal stability but also opens avenues for their application in diverse industries, ensuring that bioactive compounds are effectively preserved and delivered.

Figure 8.

Thermogravimetric curves obtained for different materials and formulations: NLC-Blank, NLC-TAP, NLC-NaDES, and NLC-TAP-NaDES.

Figure 8.

Thermogravimetric curves obtained for different materials and formulations: NLC-Blank, NLC-TAP, NLC-NaDES, and NLC-TAP-NaDES.

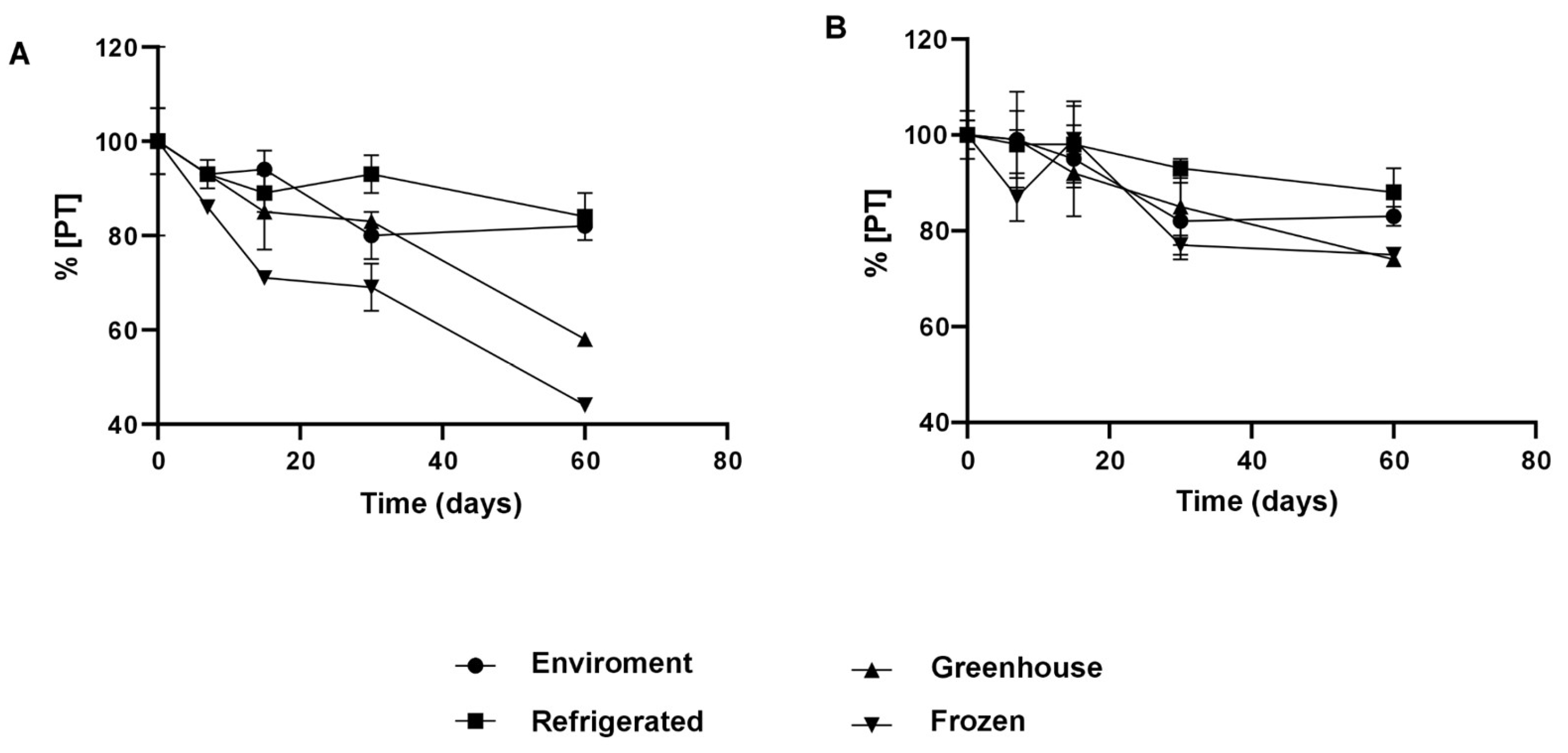

Retention and Stability of Phenolic Compounds

The integration of NaDES into NLCs resulted in significantly higher retention of phenolic compounds, even under adverse conditions (

Figure 9). After 30 days, the NLC-TAP-NaDES formulation retained approximately 85% of its phenolic content under ambient conditions and 95% under refrigeration, whereas the NLC-TAP formulation showed inferior retention, particularly under thermal stress (~40 °C) and freezing. These results reflect the stabilizing role of NaDES, which reduce the exposure of phenolic compounds to environmental factors and prevent oxidative degradation.

Figure 9.

Representation of the concentration of total polyphenols (%) nanoencapsulated and stored at different temperature conditions. (A) NLC-TAP: formulation with murumuru butter, Brij® O10, buriti oil and extract and (B) NLC-TAP-NaDES: formulation with murumuru butter, Brij® O10, buriti oil and NaDES + extract.

Figure 9.

Representation of the concentration of total polyphenols (%) nanoencapsulated and stored at different temperature conditions. (A) NLC-TAP: formulation with murumuru butter, Brij® O10, buriti oil and extract and (B) NLC-TAP-NaDES: formulation with murumuru butter, Brij® O10, buriti oil and NaDES + extract.

The incorporation of Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NaDES) into Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs) has been demonstrated to significantly enhance the retention of phenolic compounds, even when subjected to adverse environmental conditions (

Figure 9). After 30 days, the NLC-TAP-NaDES formulation retained approximately 85% of its phenolic content under ambient conditions and 95% under refrigeration, whereas the NLC-TAP formulation showed inferior retention, particularly under thermal stress (~40 °C) and freezing. These results reflect the stabilizing role of NaDES, which reduce the exposure of phenolic compounds to environmental factors and prevent oxidative degradation.

About the results of the percentage of total polyphenol content (TP) retention of nanoparticles formulated with taperebá peel extract, NLC-TAP (without the addition of NaDES) and NLC-TAP-NaDES (with the addition of NaDES), it was verified that, between the beginning of the test and the 15th day, there was no significant difference between the temperatures studied (p≥0.05).

After 30 days of storage, it was found that refrigeration temperature showed the highest retention of TP in NLC-TAP (~95%), followed by ambient and stressful temperatures (~80%) (p≥0.05). Ambient (~80%) and refrigeration (~85%) temperatures were those that obtained the highest values of TP retention in the nanoparticles at the end of the 60 days of testing (p≥0.05).

NLCs without the addition of NaDES (NLC-TAP) that were kept at freezing temperature were not able to protect the phenolic content (~40% TP retention) as effectively as under storage conditions at room temperature and refrigerated (~85%). This may be a consequence of the loss of colloidal stability of the nanoparticles due the phase separation during the freezing process. This separation leads to a high concentration of particles, which can generate irreversible aggregation and fusion of particulate material, in addition to the crystallization of ice, exerting mechanical stress on the system [

41].

After 60 days of storage at stressful temperatures, NLCs without NaDES (NLC-TAP) showed a significant decrease in TP retention (~50%). In theory, this type of entrapment of the active ingredient in nanostructures, which are made up of lipids in the solid and liquid phases (NLCs), has a lower melting point temperature than nanostructures made up only of lipids in the solid phase (SLN). This characteristic makes them unstable at stressful temperatures, but suitable for storage at room temperature [

23]. Therefore, it is possible to suggest that there was instability of NLC-TAP when stored at ~40 °C, which promoted greater degradation of TP, as phenolic compounds are known to be thermolabile [

6,

37].

In general, at the end of this experiment, it was possible to verify that the NLCs with the addition of NADES obtained better results when compared to those without (p≥ 0.05). The best storage conditions were refrigeration and room temperatures (~85% TP retention), followed by stressful and freezing temperatures (~75% TP retention), demonstrating interesting results on the use of NADES in these formulations.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) results (Figure 3) complement these findings, showing that NLC-TAP-NaDES particles exhibited a more diffuse morphology compared to the organized structure of NLC-TAP particles. This structural disorganization in NaDES-containing particles, also evidenced by the reduction in C-H band intensity in FTIR, enhances thermal flexibility and stability, particularly under extreme storage conditions.

Under freezing conditions, the cryoprotective effect of NaDES was evident. While the NLC-TAP-NaDES formulation retained approximately 75% of its phenolic compounds after 30 days, the NLC-TAP formulation showed a reduced retention of about 50% (

Figure 9). This behavior can be attributed to the ability of NaDES to mitigate ice crystal formation and phase separation, phenomena known to promote aggregation and degradation of bioactives.

Infrared Spectroscopy

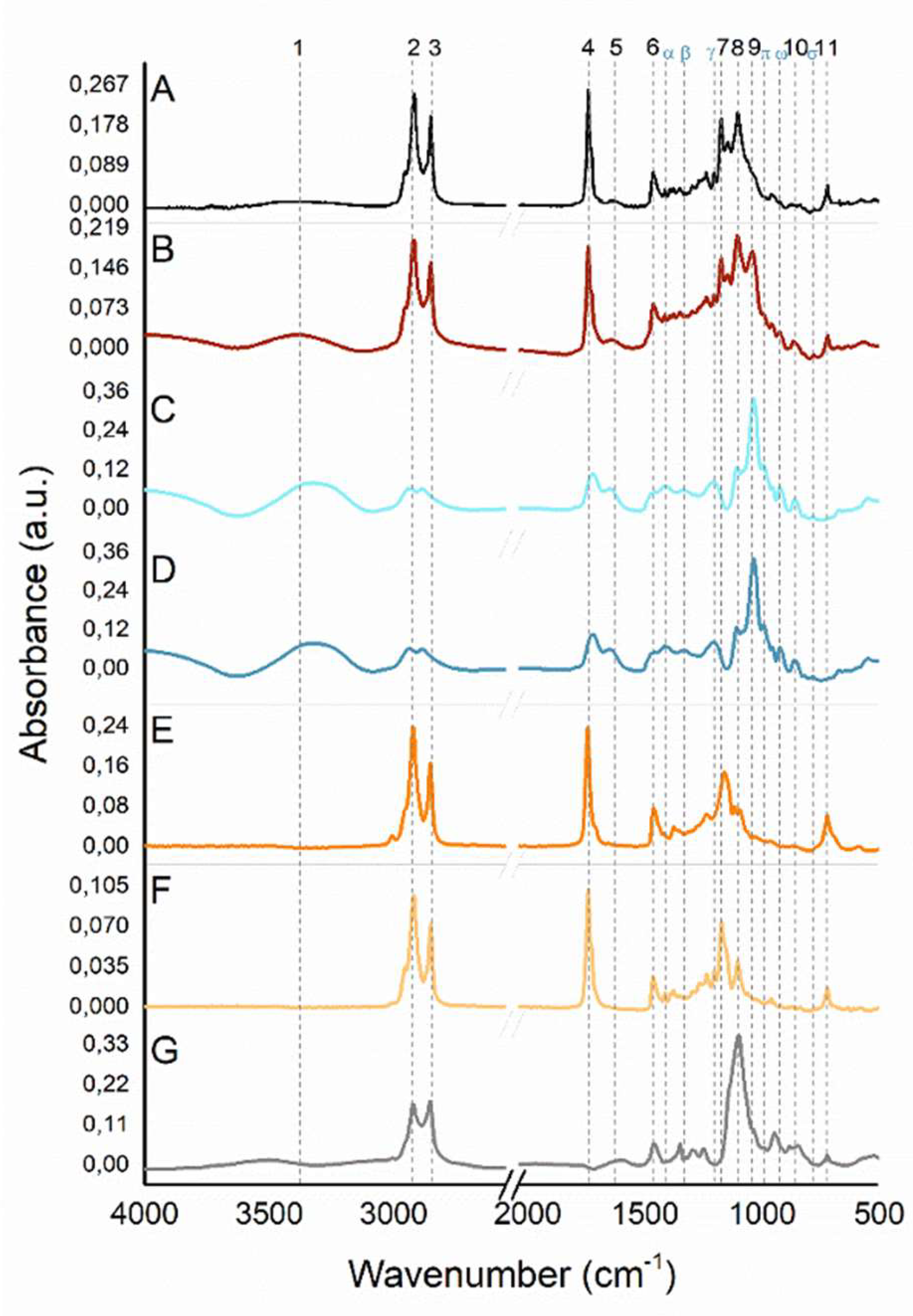

Samples containing

NaDES with extract (

Figure 10C) and

NaDES without extract (

Figure 10D) showed minimal variations in relation to the identified peaks positions. The largest shift observed was ± 5 cm

-1. Thus, since the NLCs were formulated with

Spondias mombin L. extract, the reference values considered to this analysis will be given from

NaDES with extract sample (C). The signatures (sig.) found are in consonance with the literature and correspond to the presence of glycerol, citric acid, and choline chloride. The broad band at 3321 cm

-1 (sig.1) is related to ν(OH), the narrow peaks at 2934 (sig. 2) and 2890 cm

-1 (sig. 3) assign to ν

as(CH

2) and ν

s(CH

2), respectively. 1721 (sig. 4) and 1646 cm

-1 (sig. 5) can be assigned to ν(C=O). In the fingerprint region (1500-500 cm

-1), the narrow and strong peak situated in 1035 cm

-1 (sig. 9) refers to ν

as(C-C-O) assignment, and can be associated to glycerol, as well as choline chloride presence. The additional medium and weak peaks in this region at 1411 (sig. α), 1331 (sig. β), 1205 (sig. γ), 1107 (sig. 8), 991 (sig. π), 921 (sig. ω), 860 (sig. 10), and 780 cm

-1 (sig. σ) may be accredited, correspondingly, to δ(C-O-H), ρ(C-O-H), ν(C-C-O), δ(OH), ν(CN), δ(OH), ν

s(C-C-O), and ρ(CH

2). The taperebá extract did not indicate any influence regard to the molecular pattern in the IR spectra containing NaDES.

Figure 10.

Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectra. (A) NLC with extract and without NaDES (NLC-TAP), (B) NLC with NaDES and extract (NLC-TAP-NaDES), (C) NaDES with extract, (D) NaDES without extract, (E) Buriti oil, (F) Murumuru butter, and (G) Brij® O10. The numbered dashed lines correspond to the peak’s positions, referring to sample B (Nano extract with NaDES). The dashed lines with greek letters correspond to the peak’s positions referring to sample D (NaDES).

Figure 10.

Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectra. (A) NLC with extract and without NaDES (NLC-TAP), (B) NLC with NaDES and extract (NLC-TAP-NaDES), (C) NaDES with extract, (D) NaDES without extract, (E) Buriti oil, (F) Murumuru butter, and (G) Brij® O10. The numbered dashed lines correspond to the peak’s positions, referring to sample B (Nano extract with NaDES). The dashed lines with greek letters correspond to the peak’s positions referring to sample D (NaDES).

As occurs with NaDES samples, several functional groups with the same signature are present in the buriti oil, murumuru butter, and some in Brij® O10 IR spectra. What takes place with Brij® O10 signatures is that this surfactant comes from vegetable-based fatty ethers. Brij® O10 similar signatures to the lipid part used in the formulation (buriti and murumuru) correspond to νas(CH2), νs(CH2), δ(CH2), ν(C-C-O), and ρ(CH2), respectively, 2920 (sig.2), 2853 (sig. 3), 1463 (sig. 6), 1101 (sig. 8), and 723 cm-1 (sig.11). The narrow medium peaks (absent in Brij® O10) around 1741 and 1744 cm-1 (sig. 4), and 1172 and 1161 cm-1(sig. 7), for murumuru butter and buriti oil, correspond, subsequently, to ν(C=O) and ν(C=C-C-O).

Comparing the obtained NLCs IR spectra, it is observed, at ν(OH) (3367 and 3375 cm

-1, for

NLC-TAP (

Figure 10A) and

NLC-TAP-NaDES (

Figure 10B), respectively), the difference on the band shape between the samples. For

NLC-TAP-NaDES this broad band (sig. 1) becomes defined, as well as presenting greater relative intensity, indicating that the amount/ concentration of these (OH) groups is also higher. This contribution can be given due to the substantial availability of hydroxyl compounds related to glycerol, citric acid, and choline chloride, since water content used in the formulation is also smaller than

NLC-TAP. The peaks corresponding to ν

as(CH

2) and ν

s(CH

2) (2914 and 2927 cm

-1 (sig. 2), and 2855 and 2853 cm

-1(sig. 3)), for

NLC-TAP-NaDES and

NLC-TAP, resemble the same peaks present in the precursors (butter, oil and tensioactive). The shifts that occur in the spectral region between 4000-2500 cm

-1 (vibrational modes ν(OH), ν(CH) or ν(NH)) may happen due to the overlapping of organic molecules involved in the reaction, as is the case of shifts (± 10 cm

-1) situated in ν(OH) and ν

as(CH

2), when comparing the NLCs. The other signatures found (ν(C=O) (sig. 4), δ(CH

2) (sig. 6), ν(C=C-C-O) (sig.7), and ρ (CH

2) (sig. 11)), in both samples, are in line with the buriti oil, and murumuru butter. The exclusive peaks found in the

NLC-TAP-NaDES sample (1030 (sig. 9), 991 (sig. π), 923 (sig. ω), and 864 cm

-1 (sig. 10), subsequently, ν

as(C-C-O), δ(OH), ν(CN), and ν

s(C-C-O), ascribed to NaDES. Additionally, it should be evidenced that the presence of glycerol among the exclusive signatures mentioned for

NLC-TAP-NaDES is relevant, since this compound, besides being coming from natural/ vegetable bases, is related to several technological applications to the pharmaceutical (capsules, antibiotics, antiseptics), and cosmeceutical (moisturizers, deodorants, and makeup) industries.

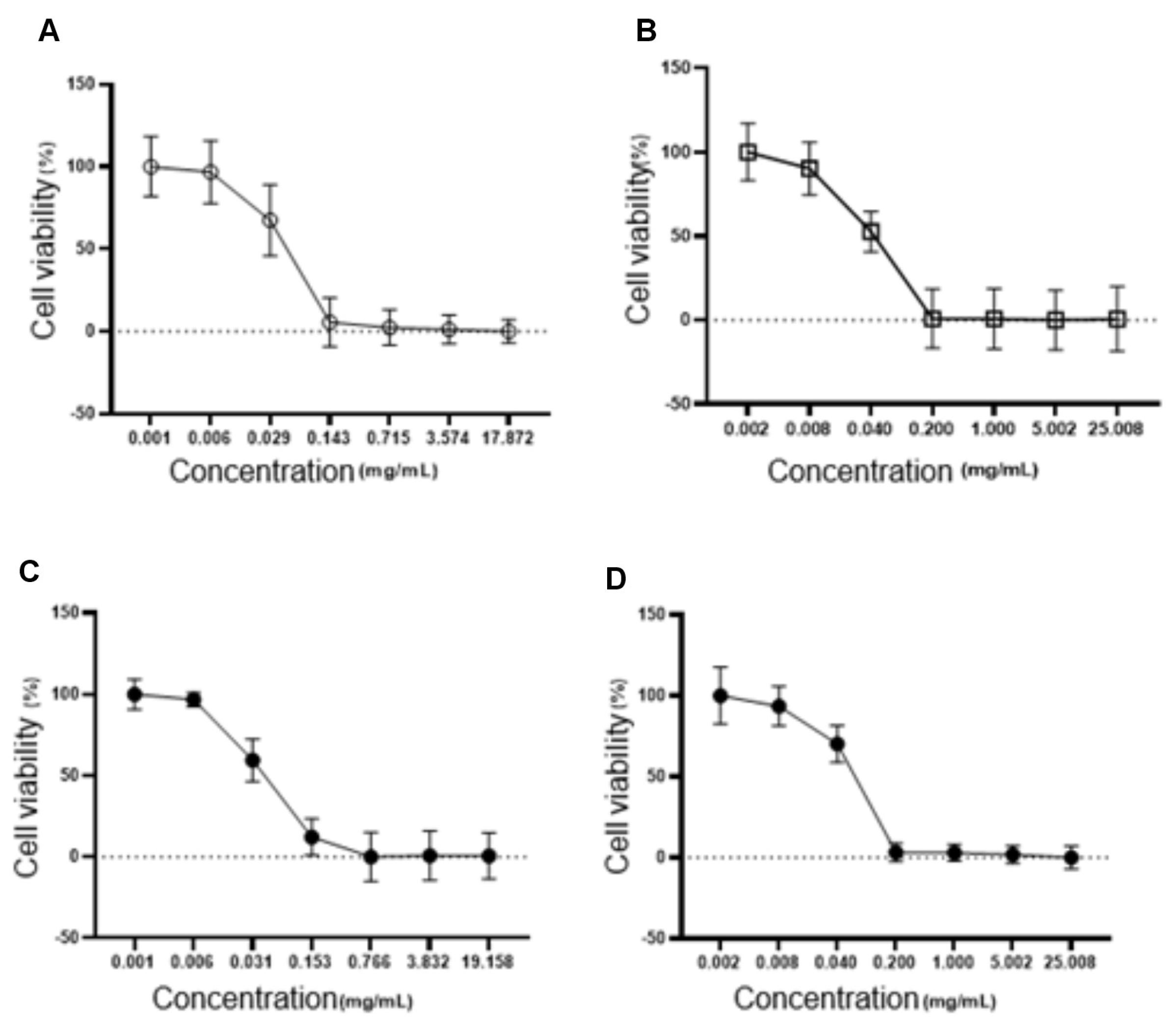

3.2. Embryotoxicity, Cytotoxicity Testing and in vitro ROS Production

Cytotoxicity assays in fibroblasts (L929) showed a higher IC50 for the NLC-TAP-NaDES formulation (56.48 µg/mL) compared to formulations without NaDES (NLC–TAP), indicating reduced cytotoxicity in normal cells (

Figure 11). These results align with the hypothesis that NaDES enhance the encapsulation efficiency and stability of phenolic compounds, reducing their direct interaction with cellular targets and mitigating toxicity. The combined results of these bioassays suggest that while NaDES-containing NLCs offer significant advantages in phenolic stabilization, further studies are needed to optimize their concentrations and evaluate their long-term effects in more complex biological systems. The cytotoxicity of NLCs was also tested on fibroblasts, and is represented in

Figure 15. The IC50 values obtained were 39.95 µg/mL for NLC-Blank; 40.75 µg/mL for NLC-NaDES; 40.10 µg/mL for NLC-TAP; and 56.48 µg/mL for NLC-TAP-NaDES, the latter being the only one that showed a statistical difference (p<0.05).

Figure 11.

Cytotoxicity assays in fibroblasts (L929). The graphs illustrate the dose-dependent effect of different NLC formulations on cell viability (%), with IC50 values for each formulation. The IC50 values obtained were 39.95 µg/mL for NLC-Blank (A), 40.75 µg/mL for NLC-NaDES (B), 40.10 µg/mL for NLC-TAP (C), and 56.48 µg/mL for NLC-TAP-NaDES (D). The NLC-TAP-NaDES formulation exhibited significantly lower cytotoxicity compared to other formulations (p<0.05), supporting the hypothesis that NaDES reduces the direct interaction of phenolic compounds with cellular targets, thereby enhancing biocompatibility. These results highlight the potential of NaDES-containing NLCs in mitigating toxicity while maintaining phenolic stabilization.

Figure 11.

Cytotoxicity assays in fibroblasts (L929). The graphs illustrate the dose-dependent effect of different NLC formulations on cell viability (%), with IC50 values for each formulation. The IC50 values obtained were 39.95 µg/mL for NLC-Blank (A), 40.75 µg/mL for NLC-NaDES (B), 40.10 µg/mL for NLC-TAP (C), and 56.48 µg/mL for NLC-TAP-NaDES (D). The NLC-TAP-NaDES formulation exhibited significantly lower cytotoxicity compared to other formulations (p<0.05), supporting the hypothesis that NaDES reduces the direct interaction of phenolic compounds with cellular targets, thereby enhancing biocompatibility. These results highlight the potential of NaDES-containing NLCs in mitigating toxicity while maintaining phenolic stabilization.

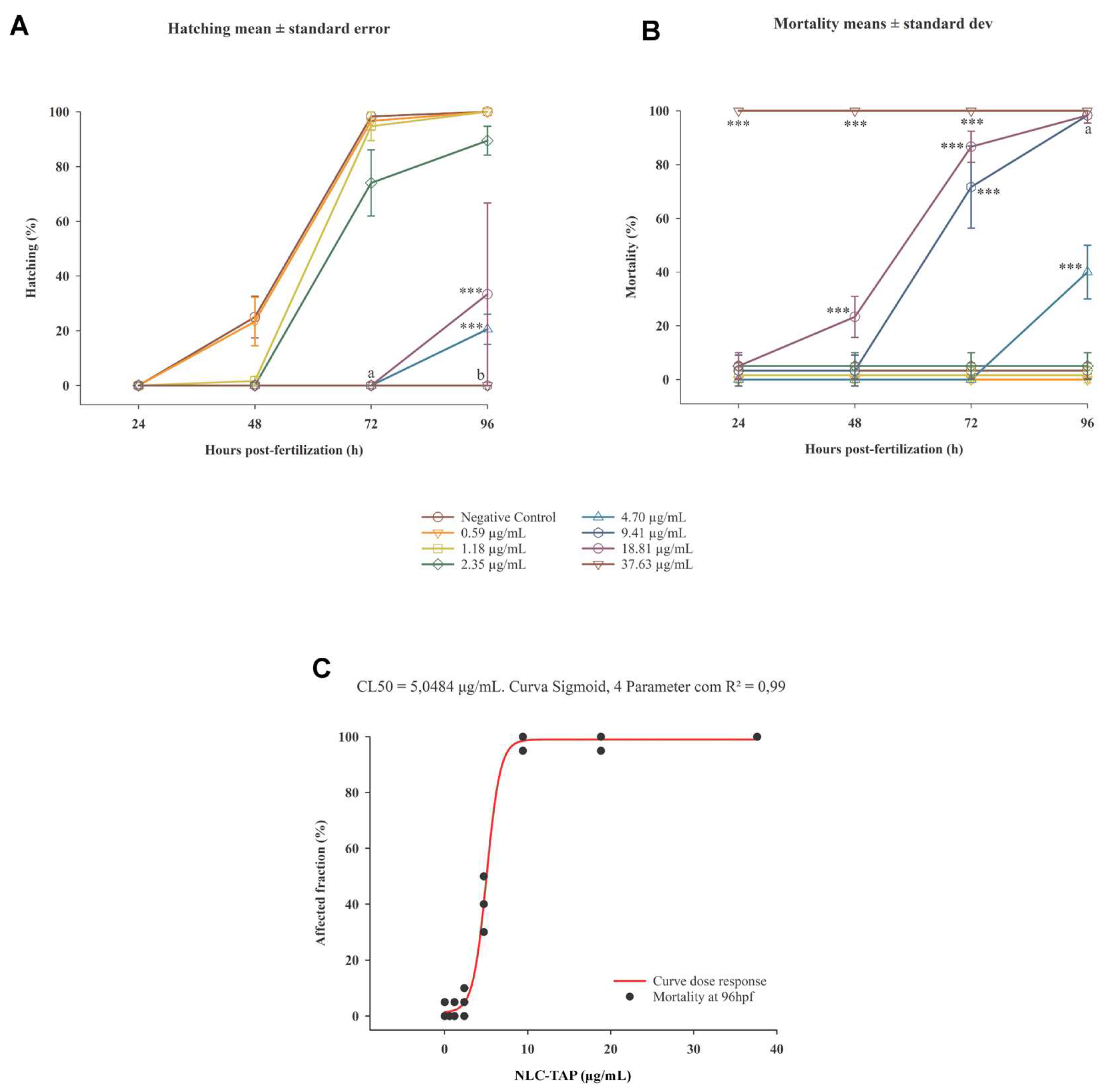

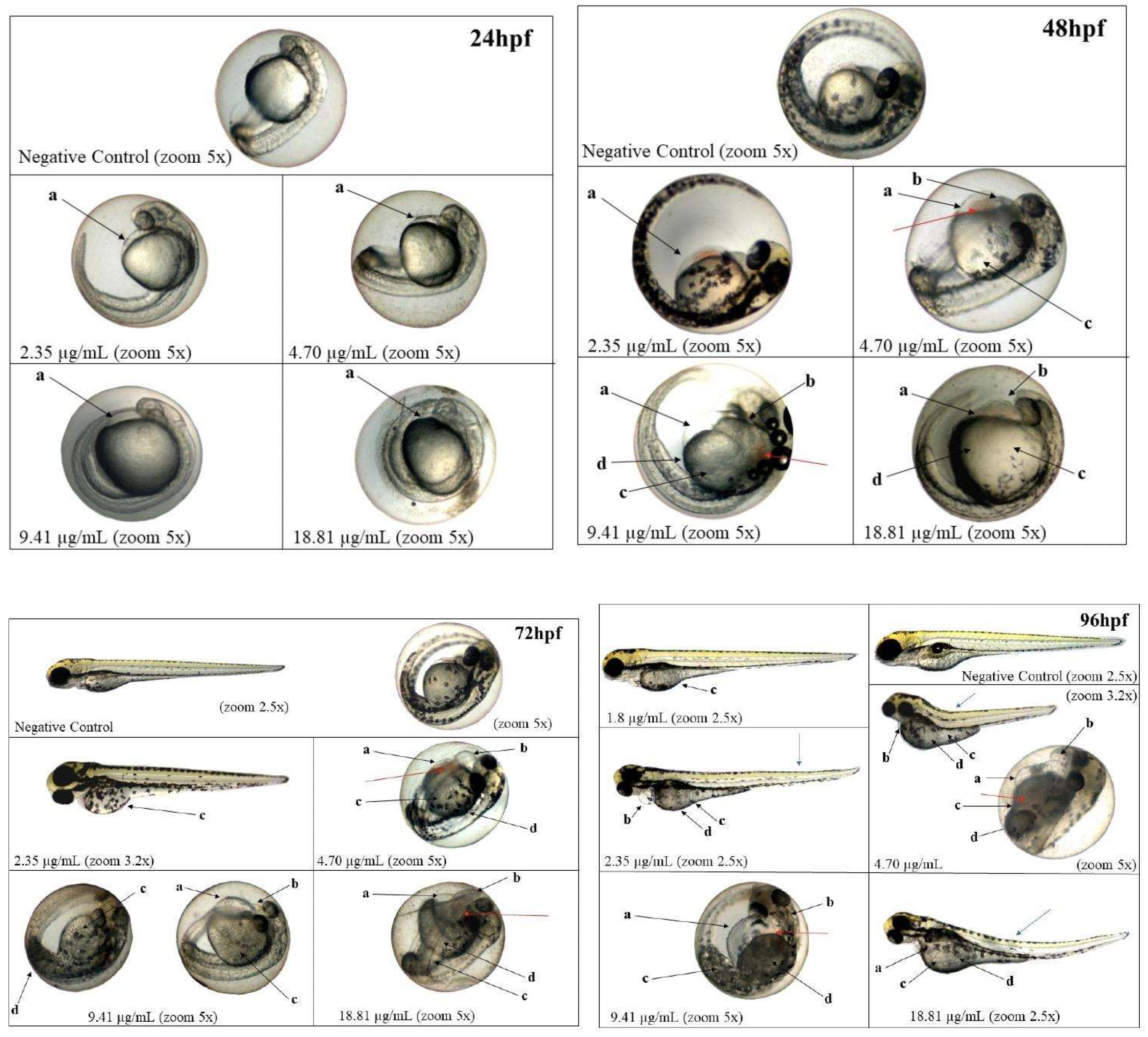

The embryotoxicity and cytotoxicity assays revealed important awareness into the biocompatibility and potential therapeutic window of NLC-TAP-NaDES. Zebrafish embryo tests showed a dose-dependent toxicity profile, with an LC50 of 5.05 μg/mL for the NLC-TAP-NaDES formulation. The results indicated significant mortality at higher concentrations, particularly at 37.63 μg/mL, where 100% lethality was observed within 24 hours (

Figure 12).

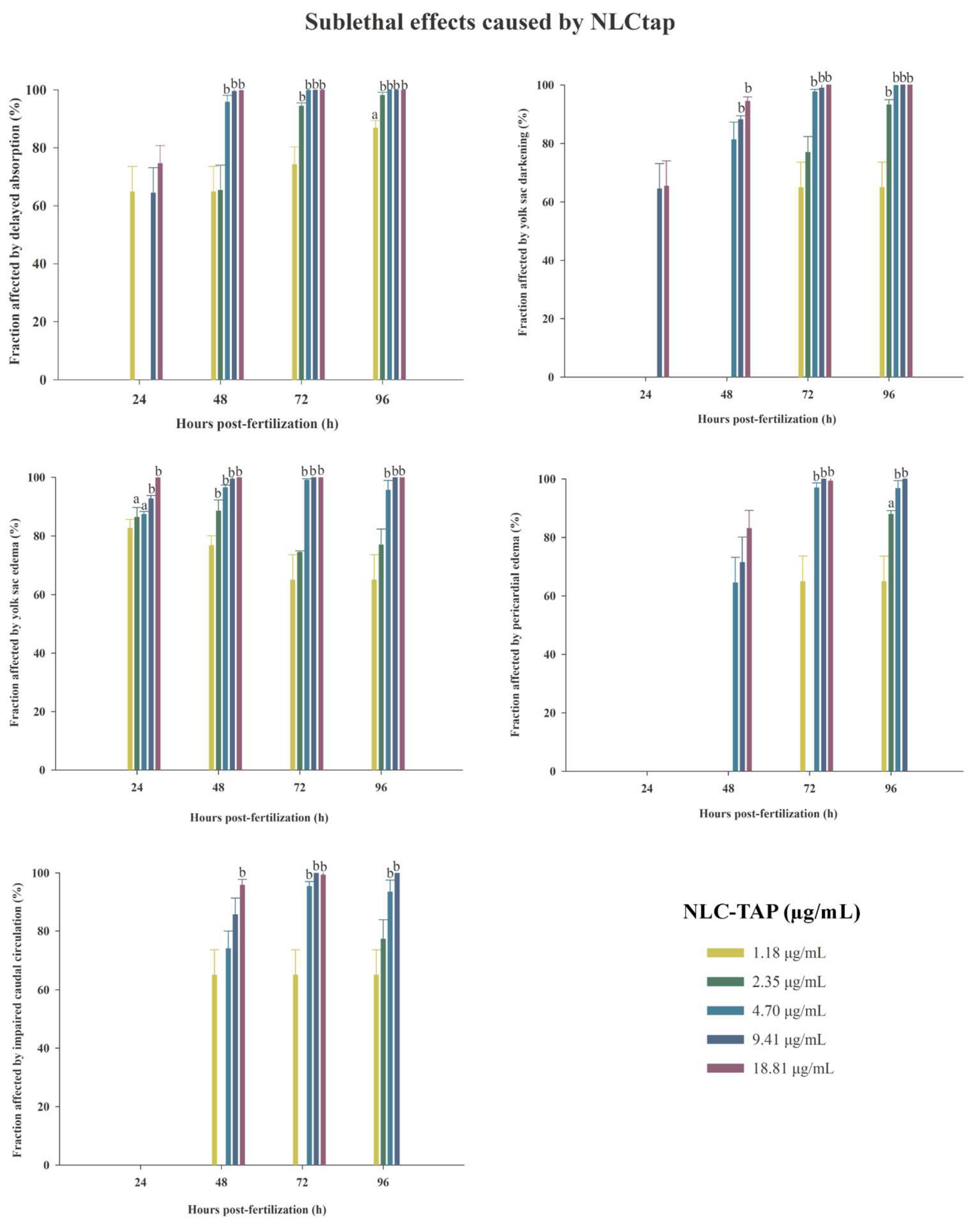

These findings underscore the importance of optimizing formulation concentrations for safe application in biological systems. Sublethal effects, such as delayed yolk sac absorption, yolk sac darkening, and pericardial edema, were observed predominantly at higher concentrations (

Figure 13). Notably, the NLC-TAP-NaDES formulation demonstrated a less pronounced impact on embryonic development compared to formulations without NaDES, suggesting a potential mitigating role of NaDES in modulating the bioavailability and toxicity of phenolic compounds. It is also possible to observe the photodocumentation of organisms exposed to NLC-TAP in

Figure 14.

Figure 12.

Graphics depicting the embryotoxicity test of NLC-TAP in zebrafish. A. Chart illustrating the hatching rate over the 96-hour exposure period. B. Graph depicting the mortality rate throughout the 96-hour exposure period. Significant differences compared to the negative control are indicated by *** p<0.001, where both a and b also signify statistical differences of p<0.001. In (A) concentrations of 4.70 μg/mL, 9.41 μg/mL, 18.81 μg/mL, and 37.63 μg/mL are associated, with data presented as mean ± standard error. In (B) concentrations of 9.41 μg/mL and 37.63 μg/mL are presented, with data shown as mean ± standard deviation. (C) Concentration-response curve (mortality) of organisms exposed to NLC-TAP for 96 hours, revealing an LC50 of 5.05 μg/mL - Model: sigmoidal - 4 parameters. R² = 0.99.

Figure 12.

Graphics depicting the embryotoxicity test of NLC-TAP in zebrafish. A. Chart illustrating the hatching rate over the 96-hour exposure period. B. Graph depicting the mortality rate throughout the 96-hour exposure period. Significant differences compared to the negative control are indicated by *** p<0.001, where both a and b also signify statistical differences of p<0.001. In (A) concentrations of 4.70 μg/mL, 9.41 μg/mL, 18.81 μg/mL, and 37.63 μg/mL are associated, with data presented as mean ± standard error. In (B) concentrations of 9.41 μg/mL and 37.63 μg/mL are presented, with data shown as mean ± standard deviation. (C) Concentration-response curve (mortality) of organisms exposed to NLC-TAP for 96 hours, revealing an LC50 of 5.05 μg/mL - Model: sigmoidal - 4 parameters. R² = 0.99.

Figure 13.

Graphics of sublethal effects caused by various concentrations of NLC-TAP during the embryotoxicity test in zebrafish. A: Delayed absorption of the yolk sac. B: Darkening of the yolk sac. C: Edema in the yolk sac. D: Edema in the pericardium. E: Alteration in caudal circulation. Significant difference represented by a and b, where a is p < 0.005, and b is p < 0.001. The data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Figure 13.

Graphics of sublethal effects caused by various concentrations of NLC-TAP during the embryotoxicity test in zebrafish. A: Delayed absorption of the yolk sac. B: Darkening of the yolk sac. C: Edema in the yolk sac. D: Edema in the pericardium. E: Alteration in caudal circulation. Significant difference represented by a and b, where a is p < 0.005, and b is p < 0.001. The data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Figure 14.

Photodocumentation of organisms exposed for 96 hours to NLC-TAP. Black arrows - a: yolk sac edema; b : pericardial edema; c: delayed absorption; d: yolk sac darkening. Blue and red arrows indicate sublethal changes that did not show statistically significant differences. Blue arrows: alterations in the notochord. Red arrows: blood stasis.

Figure 14.

Photodocumentation of organisms exposed for 96 hours to NLC-TAP. Black arrows - a: yolk sac edema; b : pericardial edema; c: delayed absorption; d: yolk sac darkening. Blue and red arrows indicate sublethal changes that did not show statistically significant differences. Blue arrows: alterations in the notochord. Red arrows: blood stasis.

The results of the embryotoxicity and cytotoxicity assays conducted on nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) containing natural deep eutectic solvents (NaDES) provide compelling evidence for the viability of these formulations as a platform for the delivery of bioactive compounds. The findings indicate a significant reduction in cytotoxicity when these NLCs are administered to normal cells, suggesting a favorable biocompatibility profile [

55]. This characteristic is particularly important in the context of drug delivery systems, where the safety of the carrier is paramount to ensure that therapeutic agents can be delivered effectively without causing undue harm to healthy tissues.

Moreover, the moderated impact on embryonic development observed at sublethal doses further supports the notion that NaDES-containing NLCs can be designed to minimize adverse effects during critical stages of development [

56]. This is a crucial consideration, especially in applications involving reproductive health and developmental therapeutics. The ability to maintain a balance between efficacy and safety is a hallmark of successful drug delivery systems, and the data presented in this study suggest that NaDES-containing NLCs may achieve this balance effectively.

However, it is essential to note the dose-dependent toxicity observed at higher concentrations of these formulations. This finding underscores the necessity for meticulous optimization of the NLC formulations to ensure that they can be safely utilized across a range of concentrations [

57]. The implications of this observation are significant; it highlights the importance of conducting thorough dose-response studies to establish safe dosage thresholds that maximize therapeutic benefits while minimizing potential risks.

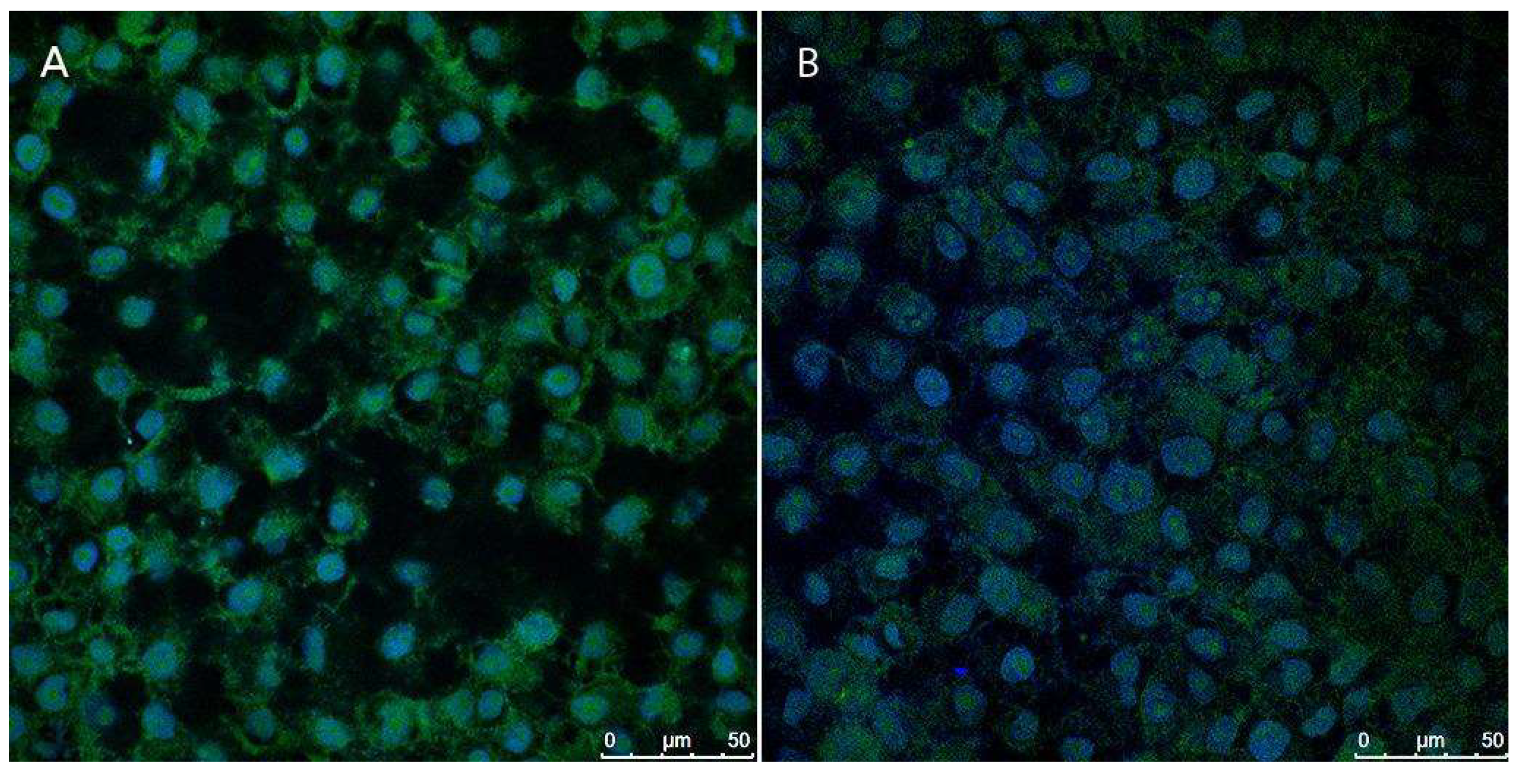

Figure 15 presents fluorescence images depicting the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cells initially subjected to H₂O₂-induced oxidative stress, followed by treatment with the NLC-TAP-NaDES formulation in the treated group. Panel A represents the control group, where stressed cells were left untreated, while panel B shows the cellular response to the NLC-TAP-NaDES treatment.

Figure 15.

The fluorescence images of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, assessed using the CellROX® Green Reagent assay after treatment with NLC-TAP-NaDES for 24 h, are shown. Panel (A) displays the control cells, while panel (B) depicts the cells treated with NLC-TAP-NaDES.

Figure 15.

The fluorescence images of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, assessed using the CellROX® Green Reagent assay after treatment with NLC-TAP-NaDES for 24 h, are shown. Panel (A) displays the control cells, while panel (B) depicts the cells treated with NLC-TAP-NaDES.

The results highlight a markedly lower fluorescence signal in panel B, demonstrating the formulation's ability to mitigate the intracellular accumulation of ROS caused by H₂O₂. This antioxidant effect is attributed to the bioactive phenolic compounds derived from the peel extract of taperebá (

Spondias mombin), which are rich in ellagic acid and quercetin—well-known radical scavengers. Previous studies by our group have shown that taperebá peel extract exhibits a high polyphenol content (2623 mg GAE/L) and strong antioxidant activity, as assessed by the DPPH (258 mM TEAC/100 mL) and ABTS (495 mM TEAC/100 mL) assays [

7]. These properties make the extract a promising source for antioxidant applications.

Moreover, the role of NaDES combined with the NLC system was pivotal in enhancing the stability and bioavailability of the bioactive compounds. The NLC-NaDES system effectively protected polyphenols from oxidative degradation and enabled controlled release of antioxidants, targeting their action to mitigate the oxidative damage induced by H₂O₂. Consequently, treated cells exhibited a significantly reduced oxidative load compared to the control, as evidenced by the diminished fluorescence intensity associated with ROS production.

This study underscores the capability of NLC-NaDES-based formulations to alleviate oxidative damage under conditions of pre-induced stress, as demonstrated here with H₂O₂. The approach leverages underutilized by-products, such as taperebá peels, aligning with the principles of sustainability and circular bioeconomy. The proposed technology represents a substantial advancement in the development of innovative antioxidant therapies, with potential applications in addressing oxidative stress-related diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and chronic inflammation.

These findings also support the feasibility of employing this platform in preclinical studies to evaluate its efficacy under more complex conditions and, eventually, its application in pharmaceutical and nutraceutical formulations aimed at managing redox imbalance in living systems. The combination of bioactive natural extracts, NaDES, and NLC exemplifies a modern paradigm of green nanotechnology with broad applications and global impact in the field of antioxidant science.

To further substantiate the therapeutic potential and safety of NaDES-containing NLCs, future research should prioritize in vivo assessments. These studies are critical for understanding the pharmacokinetics, biodistribution, and long-term effects of these formulations within a living organism [

58]. In vivo models can provide insights that are not attainable through in vitro studies alone, particularly regarding the interactions between the NLCs and biological systems, including immune responses and metabolic pathways.

Additionally, long-term evaluations are necessary to assess the chronic effects of these formulations, particularly in relation to their cumulative exposure and potential for toxicity over extended periods [

59]. Such studies will be instrumental in determining the feasibility of these NLCs for clinical applications, especially in health-related fields where sustained delivery of bioactive compounds is desired.

In conclusion, while the preliminary results are promising, the path forward requires a comprehensive approach that includes optimization of formulation parameters, rigorous in vivo testing, and long-term safety evaluations. By addressing these critical areas, researchers can pave the way for the successful application of NaDES-containing NLCs in various therapeutic contexts, ultimately contributing to advancements in drug delivery systems and improving patient outcomes.

3.3. Sustainable Implications and Future Applications

The integration of nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) with natural deep eutectic solvents (NaDES) represents a significant advancement in the utilization of agricultural byproducts, particularly the peel of

Spondias mombin. This innovative approach aligns with global sustainability trends and circular economy practices, emphasizing the efficient use of natural resources [

60,

61]. Agricultural and food industries produce substantial volumes of underutilized byproducts, which are often discarded as waste. The transformation of

S. mombin peel, rich in bioactive phenolic compounds, into a valuable resource through advanced nanotechnology exemplifies the potential of co-product-based innovations to address critical environmental challenges, such as waste accumulation and resource inefficiency [

62].

The application of NLCs and NaDES not only enhances the bioavailability and stability of phenolic compounds but also reduces the environmental footprint associated with traditional manufacturing processes. By leveraging agricultural byproducts and eliminating the need for toxic solvents, this approach provides a sustainable model for industrial innovation [

53]. This synergy between green solvents and nanostructured delivery systems illustrates how environmentally friendly and biocompatible technologies can support the production of scalable solutions that align with green chemistry principles [

64,

65].

From a neo-industrialization perspective, the valorization of

S. mombin peel and similar co-products contributes to building resilient value chains that prioritize resource efficiency, reduced carbon emissions, and technological innovation. These efforts resonate with policies promoting green industrial development, particularly in emerging economies where agricultural byproducts represent an abundant yet untapped resource [

66,

67]. Furthermore, this study highlights the potential for such technologies to catalyze the development of next-generation materials that address global health challenges, integrating the principles of bioeconomy, circular economy, and technological innovation [

68,

69].

Future research should focus on scaling these technologies for industrial applications, exploring their potential in broader sectors such as environmental remediation, food preservation, and renewable energy systems. Collaborations between academia, industry, and policymakers will be essential to accelerate the adoption of co-product-based innovations, ensuring they contribute to global efforts towards a more sustainable and equitable industrial future [

70,

71].