1. Introduction

In recent years, global trends in bioeconomy and sustainability have motivated scientists and researchers to develop “green” technologies aimed at reducing carbon dioxide emissions, minimizing dependence on fossil fuels, and decreasing food waste [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. In alignment with these priorities, biomass valorization, the utilization of food and agricultural byproducts and side streams, and the reduction of food waste have become key areas of scientific focus [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. In the field of Food Technology, these efforts are primarily directed toward the recovery of biopolymers from biomass as sustainable alternatives to fossil fuel derived plastics, as well as the extraction of bioactive compounds for use in functional foods and bio-based preservatives [

9,

13,

14]. Among the most prominent categories of bioactive compounds are natural extracts and essential oils (EOs) [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20] which exhibit antioxidant, antibacterial, antifungal and anticancer properties rendering them highly promising for applications in food preservation and nutrition [

15,

18,

19,

20]. To enhance their efficacy and control their release, encapsulation within cost-effective nanocarriers such as layered silicates and natural zeolites has been proposed [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

Layered silicates include naturally abundant nanoclays such as montmorillonite and halloysite, as well as synthetically produced LDHs. The key distinction between these materials lies in their ion exchange capabilities: LDHs preferentially intercalate negatively charged ions, whereas natural nanoclays typically intercalate positively charged cations [

26,

27,

28]. Both LDHs and nanoclays have been widely studied in recent years as nanocarriers for bioactive compounds [

25,

29,

30]. LDHs, which are two dimensional (2D) clay materials of the hydrotalcite type, are particularly well suited for intercalating bioactive molecules within their interlayer spaces [

25]. These materials can be dispersed into polymeric matrices, enabling the incorporation of phenolics, polyphenols, and other bioactive compounds.

LDHs offer numerous advantages, including low cost, high biocompatibility, non-toxicity, pH-dependent stability, controlled release behavior, high anion exchange capacity, low surface charge, and excellent thermal and chemical stability [

25,

31]. Various bioactive anions such as salicylate, d-gluconate, citrate, l-ascorbic, and cinnamate have been successfully intercalated into LDHs to form LDH/bioactive hybrids with antioxidant and antibacterial properties, suitable for use in food preservation either directly or embedded in polymeric or biopolymeric matrices [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. To the best of our knowledge, polyphenols derived from olive oil or olive tree leaves have not yet been reported as intercalated compounds in LDHs. Encapsulation of such biologically active molecules within LDH layers may act as a protective “chemical flask jacket,” shielding them from biodegradation while enhancing their cellular uptake[

41].

Olive tree leaves, a byproduct of olive oil production, are typically discarded despite being a rich source of bioactive compounds [

42,

43]. These leaves contain high concentrations of valuable polyphenols including 3 hydroxytyrosol (HT), oleuropein (oleur), luteolin-7-o-glucoside (lut-7-ο-glu) and apigenin-4-o-glucoside (apig-4-o-glu) [

42]. Recovering these health promoting compounds supports their application in cosmetics, biomedicine, and the food industry as dietary supplements or natural additives [

42]. Recent studies have demonstrated the successful valorization of olive tree leaves using environmentally friendly extraction techniques, such as enzyme assisted methods, yielding OLE with a total polyphenol content of up to 605.55 mg GAE/L and high antioxidant activity [

44].

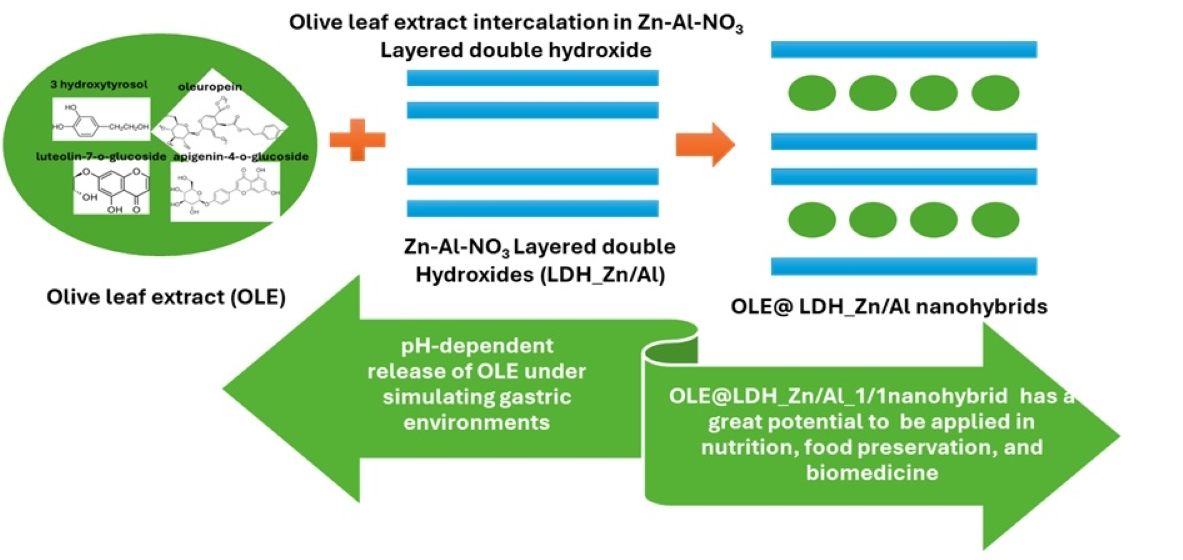

Herein, we report for the first time the successful intercalation and encapsulation of oleuropein rich OLE into Zn–Al-based layered double hydroxides (LDH_Zn/Al). LDHs were synthesized using three different Zn2+: Al3+ ratios (1:1, 2:1, and 3:1), resulting in the materials named LDH_Zn/Al_1_1, LDH_Zn/Al_2_1, and LDH_Zn/Al_3_1, respectively. The corresponding nanohybrids, OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 (x=3, 2, 1) were thoroughly characterized using X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy, High Resolution Scanning Electron Microscopy (HR-SEM) and N2 porosimetry. The antioxidant activity of the OLE@LDH_Zn/Al nanohybrids was assessed via the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay. Antibacterial activity was tested against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus Aureus and controlled release experiments were conducted to evaluate the release profile of OLE. This comprehensive study aims to identify the most effective OLE@LDH_Zn/Al nanohybrid for potential applications in nutrition and/or biomedicine as a controlled release nanocarrier for bioactive polyphenols.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Zn(NO3)2 x 6H2O, Al(NO3)3 x 9H2O, and NaOH were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany). For analytical purposes, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH·), 2,2-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt, hydrogenperoxide, 2,4,6-tripyridy-s-triazine (TPTZ), FeCl3, hydrochloric acid (37%), and formic acid (>98%) absolute ethanol (C2H5OH), sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), and acetate buffer (CH3COONa × 3H2O), Folin–Ciocalteu reagenwere purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany); and gallic acid (3,4,5-trihydrobenzoic acid) 99% isolated from Rhus chinensis Mill (JNK Tech. Co., Seongnam, Republic of Korea).

All solvents were HPLC grade; acetonitrile (99.9% purity), water (≥99.9% purity), methanol (>99.8% purity), were obtained from ChemLab (Zeldegem, Belgium). HT reference standard was purchased from ExtraSynthase (Lyon Nord, France), while the lut-7-o-glu, apig-4-o-glu and oleuropein reference standards were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany). Olive (olea europaea) leaves, koroneiki variety harvested year 2023, were obtained from a producer in the region of Agrinio, Greece. The leaves were dried at 50 °C for 5 h.

2.2. Enzymatic Assisted Extraction

The enzymatic assisted extraction of OLE was conducted according to our recent study and is described in detail in the supplementary material file [

40].

2.3. OLE@LDH_Zn/Al Nanohybrids Preparation

First, 50 mL of OLE was filtered under vacuum. An 8 M aqueous NaOH solution was prepared by dissolving 9.6 g of NaOH pellets in 30 mL of purified water. To obtain final Zn/Al molar ratios of 1:1, 2:1, and 3:1, the appropriate amounts of Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O and Al(NO₃)₃·9H₂O were accurately weighed using an analytical balance. The salts were then dissolved in 10 mL of purified water in a 250 mL beaker under stirring. Once fully dissolved, the beaker was placed in a chemical fume hood in an oil bath at 60 °C with continuous stirring. When the solution reached 60 °C, the filtered OLE was added, and stirring continued until the temperature stabilized. The prepared NaOH solution was then added dropwise to the mixture until pH=7. The reaction mixture was maintained at 60 °C under constant stirring for 24 hours. Afterward, the suspension was divided into two centrifuge tubes and centrifuged three times at 3000 rpm for 2–4 minutes. Following the first centrifugation, the pale-yellow supernatant was discarded. A small amount of purified water was added to the remaining sediment, followed by manual stirring and 3 minutes of ultrasonic treatment. The tubes were then filled with purified water and centrifuged a second time. This washing step was repeated for each centrifugation, although sonication was only applied after the first wash. After the third centrifugation, the now colorless and transparent supernatant was discarded. The remaining sediment was resuspended in a small volume of purified water, manually stirred, and transferred to a glass plate to maximize material recovery. The final product, OLE@LDH_Zn/Al nanohybrid, was dried overnight at 40 °C.

2.4. Phytochemical Analyses of OLE

The determination of HT, lut-7-o-glu, apig-4-o-glu and oleur in the olive leaf extract was performed following the analytical method proposed by the IOC, in accordance with the conditions described in IOC/T.20/Doc No 29 method [

45]. Separation of components was achieved using a reversed phase Discovery® HS C18 column (250×4.6 mm, 5 µm particle size). The mobile phase consisted of 0.2% v/v aqueous orthophosphoric acid (solvent A) and a methanol/acetonitrile mixture (50:50 v/v) as solvent B. Chromatographic separation was carried out at ambient temperature with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min and an injection volume of 20 µL.

The gradient elution was as follows: i) 0 min: 96% A and 4% B, ii) 40 min: 50% A and 50% B, iii) 45 min: 40% A and 60% B, iv) 60 min: 0% A and 100% B, v) 70 min: 0 A and 100% B, vi) 72 min: 96% A and 4% B and vii) 82 min: 96% A and 4% B. Chromatograms were recorded at 280 nm.

Quantification of the major compounds, i.e. HT, lut-7-o-glu, apig-4-o-glu, and oleur was achieved using regression analysis. Calibration curves were constructed for each standard compound.

2.5. Physicochemical Characterization of OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 Nanohybrids

The synthesized OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids were characterized using XRD, FTIR and HR-SEM. Details of the instrumentation are provided in supplementary material file in detail.

2.6. Antioxidant activity of OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 Nanohybrids

For all OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids, as well as pure freeze-dried OLE the concentration required to achieve a 50% antioxidant effect (EC50) was evaluated by three different assays: ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), dyphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging, and 2,2-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS). The experimental methodology used for the evaluation of EC50,FRAP, EC50,DPPH, and EC50,ABTS mean values described in supplementary material file in detail.

2.7. Total Polyphenols Content (TPC) of OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 Nanohybrids

The TPC of obtained OLE and all the obtained Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids was measured by using a SHIMADJU UV/VIS spectrophotometer (UV-1900, Kyoto, Japan) via the following methodology.

TPC of OLE: 0.2 mL of OLE were added in a 5 mL volumetric flask along with 2.5 mL of distilled water and 0.25 mL of Folin-Ciocalteü reagent. After 3 min, 0.5 mL of saturated sodium carbonate (Na2CO3, 30% w/v) was also added into the mixture. Finally, the solution obtained was adjusted to 5 mL using distilled water for measurements at pH=7, with 1 M citric acid aqueous solution for measurements at pH=3.6, and with 0.1 M HCl aqueous solution for measurements at pH=1. The mixture was incubated in the dark at room temperature for 2 h after which the absorbance was measured at λ = 760 nm. The results were presented as equivalents of gallic acid (GAE). Each sample was analyzed in triplicate (n = 3).

TPC of Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids: 10 mg of each nanohybrid were added in 10 mL of ethanol. The mixture was stirred and filtered with 0.45 μm filters to obtain 10 mL of an ethanolic extraction. Then 0.20 mL of such ethanolic extraction were added in a 5 mL volumetric flask, 0.20 mL of the ethanolic extracts followed by the addition of 2.50 mL of distilled water and 0.25 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. After 3 min, 0.50 mL of saturated sodium carbonate (Na2CO3, 30% w/v) was also added into the mixture. Finally, the solution obtained was brought to 5 mL with distilled water for the mesuraments at pH=7, with 1 M citric acid aquatic solution for measurements at pH=3.6, and with 0.1 M HCl aquatic solution for measurements at pH=1. This solution was left for 2 h in the dark at room temperature and the absorbance was measured at λ = 760 nm. The results were presented as equivalents of gallic acid (GAE). Each sample was analyzed in triplicate (n = 3).

All TPC measurements were performed using 1 cm pathlength cuvettes.

2.8. Antibacterial Activity

2.8.1. Antimicrobial Activity of of OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 Nanohybrids

Standard and isolated strains of the following three bacteria, including one gram-positive (

Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC25923) and

E. Coli) and one gram-negative (

Escherichia coli (ATCC25922) and

S. Aureus) bacteria were used in screening the antimicrobial activity. The antimicrobial activity of the OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids was determined using the disk diffusion method according to EUCAST guidelines and the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) was determined after applying the resazurin-based 96-well plate microdilution method [

46]

. MIC, MBC and ZOI (zone of inhibition) antibacterial activity mean values obtained after three repetitions of antibacterial activity tests.

2.8.2. Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Test

Aseptically, 50 mg of each of the OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids were weighed and directly applied as a defined circular deposit onto the surface of Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) plates which had been previously inoculated with the respective test microorganism (108 CFU ml-1). A minimum center-to-center distance of 24 mm was maintained between each sample application site to prevent overlapping of the inhibition zones. The inoculated MHA plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After the incubation, the diameter of the clear zone of inhibition surrounding each disc was calculated using a calibrated ruler. The actual diameter of inhibition was then calculated by subtracting the initial diameter of the applied sample deposit from this measurement. Specifically, the actual inhibition diameter was calculated by subtracting the initial diameter of the applied sample deposit from this measurement. The test was performed in duplicate for each test microorganism and OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids concentration.

2.8.3. Resazurin-Based 96-Well Plate Microdilution Method

The MIC determination of OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids samples was performed following the protocol described by [

46]. The analyses were carried out in a microdilution plate with 96 wells (see

Figure S4) (sterilized, 300 μL capacity, MicroWell, NUNC, Thermo-FisherScientific, Waltham, MA). The OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids were dissolved in sterile dH

2O. Initial solutions of OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids were prepared at a concentration of 50 mg·ml

-1 and further serial dilutions were performed in the 96-well plate in Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB). The concentrations tested ranged from 25 to 0.05 mg·mL

-1. Positive controls (growth control) containing inoculum as well as negative controls with broth (MHB) were prepared. After adding a standardized inoculum of the target bacteria (108 CFU ml

-1), the microplate was then incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. After incubation, 50 μL of a 0.015% w/v resazurin solution was added to each well and the plate was incubated for another 2 hours. If there's no metabolic activity (inhibition) the resazurin stays blue and if there is activity (growth) turns pink/purple. Wells without color change were scored as concentrations above the MIC. Treatments that showed inhibition of microorganisms were then tested for bactericidal activity (MBC) by plating a 10 μL sample onto MHA plates and incubating for 24 hours at 37 °C. The lowest treatment concentration that did not show colony formation after incubation in all replicates was considered the MBC.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics for OLE extraction yield, HΤ content, lut-7-ο-glu content and oleur content, as well as for EC50, TPC, and ZOI parameters were estimated using SPSS software (version 29.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The last three properties were also subjected to statistical analysis to investigate the statistically significant differences of their mean values. For such investigation the statistical test method ANOVA was chosen. A significance level of p < 0.05 was adopted for all comparisons.

3. Results

3.1. HPLC-DAD Analyses of OLE

The results of the phytochemical analysis, including the mean values of total polyphenol yield and the contents of HT, lut-7-ο-glu, apig-4-o-glu and oleur in the OLE sample, as determined by HPLC-DAD, are summarized in

Table 1. These values were calculated using the calibration curves of HT, lut-7-ο-glu, apig-4-o-glu and oleur (

Figure S1), along with the HPLC-DAD chromatogram of pure OLE recorded at 280 nm (

Figure S2).

As shown in

Table 1 a high extraction yield of 24.0±2.8 mg/L was obtained for the pure OLE. This high extraction yield value is attributed to the optimum combination of viscozyme and pectinolytic enzymes used in the microwave-assisted extraction process [

44]. According to the HPLC-DAD analysis results (

Table 1), the pure OLE contains 2.19% wt. HT (0.53 mg/L), 2.89% wt. lut-7-ο-glu (0.70 mg/L), 0.75% wt. apig-4-o-glu (0.18 mg/L) and 17.64% wt. oleur (4.24 mg/L). These findings indicate that the extract is rich in total polyphenols, with approximately 25% wt. comprising high value bioactive compounds.

3.2. Physicochemical Characterization of OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 Nanohybrids

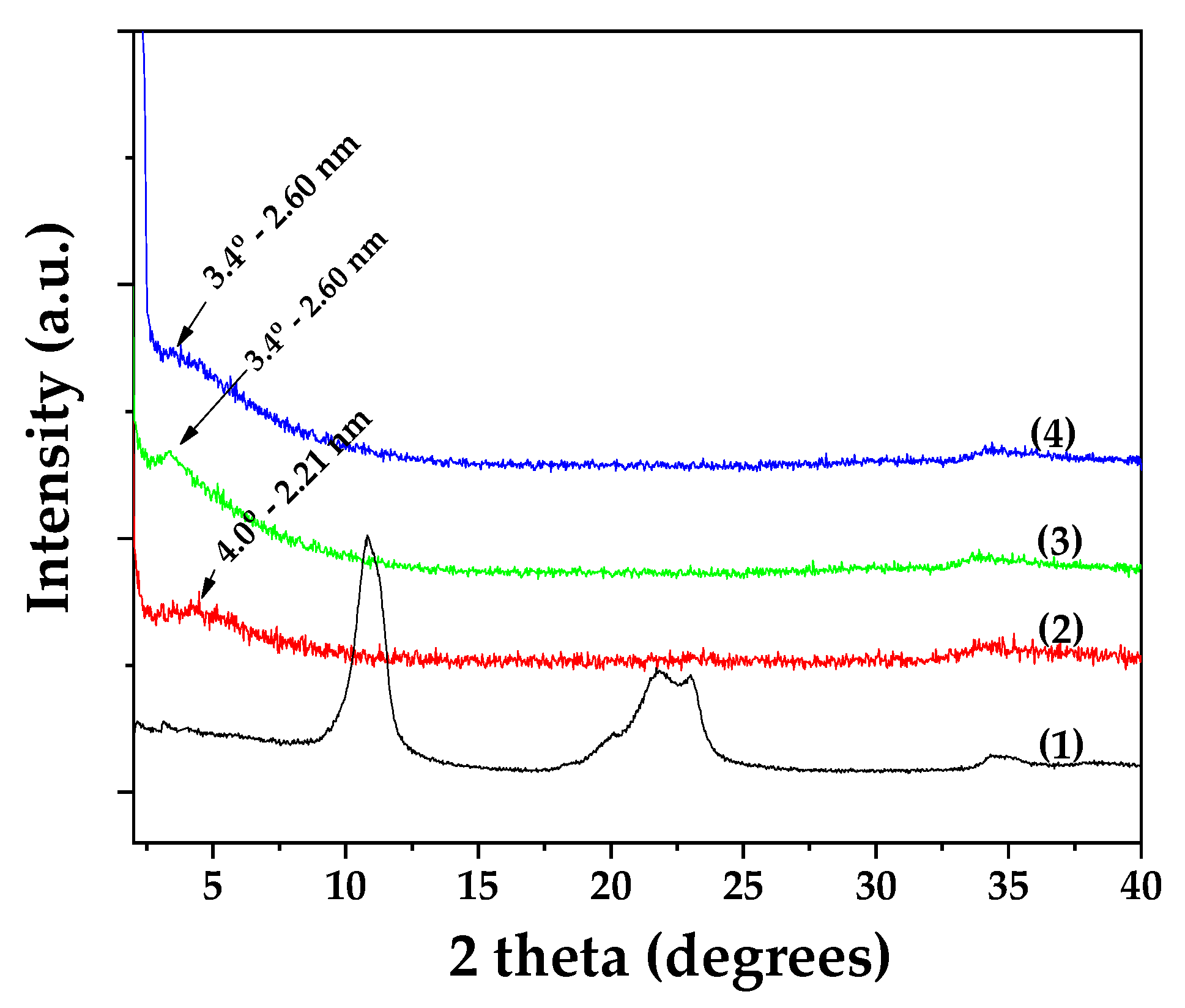

3.2.1. XRD Analysis of OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 Nanohybrids

Figure 1 presents the XRD patterns of all synthesized OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids, alongside that of pure LDH_NaNO₃_Zn/Al for comparison. As shown and consistent with previous studies, the characteristic (003) reflection of pure LDH_NaNO₃_Zn/Al (plot line 1) appears at approximately 10°, corresponding to a basal spacing of 0.83 nm. [

47,

48]. In the XRD patterns of the OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids, a broad peak observed around 5° indicates a shift of the (003) reflection to lower angles. Specifically, the basal spacing increases to 2.21 nm for OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_1/1 (plot line 2) and to 2.6 nm for both OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_2/1 (plot line 3) and OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_3/1 (plot line 4). This variation in basal spacing among the nanohybrids suggests differences in the orientation of the intercalated OLE molecules within the LDH interlayers, rather than differences in the amount of OLE adsorbed [

49,

50]. Among the three formulations, OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_2/1 exhibits the most intense (003) reflection, indicating superior platelet orientation. Overall, the XRD results confirm the successful intercalation of OLE molecules into the interlayer space of the LDH structure.

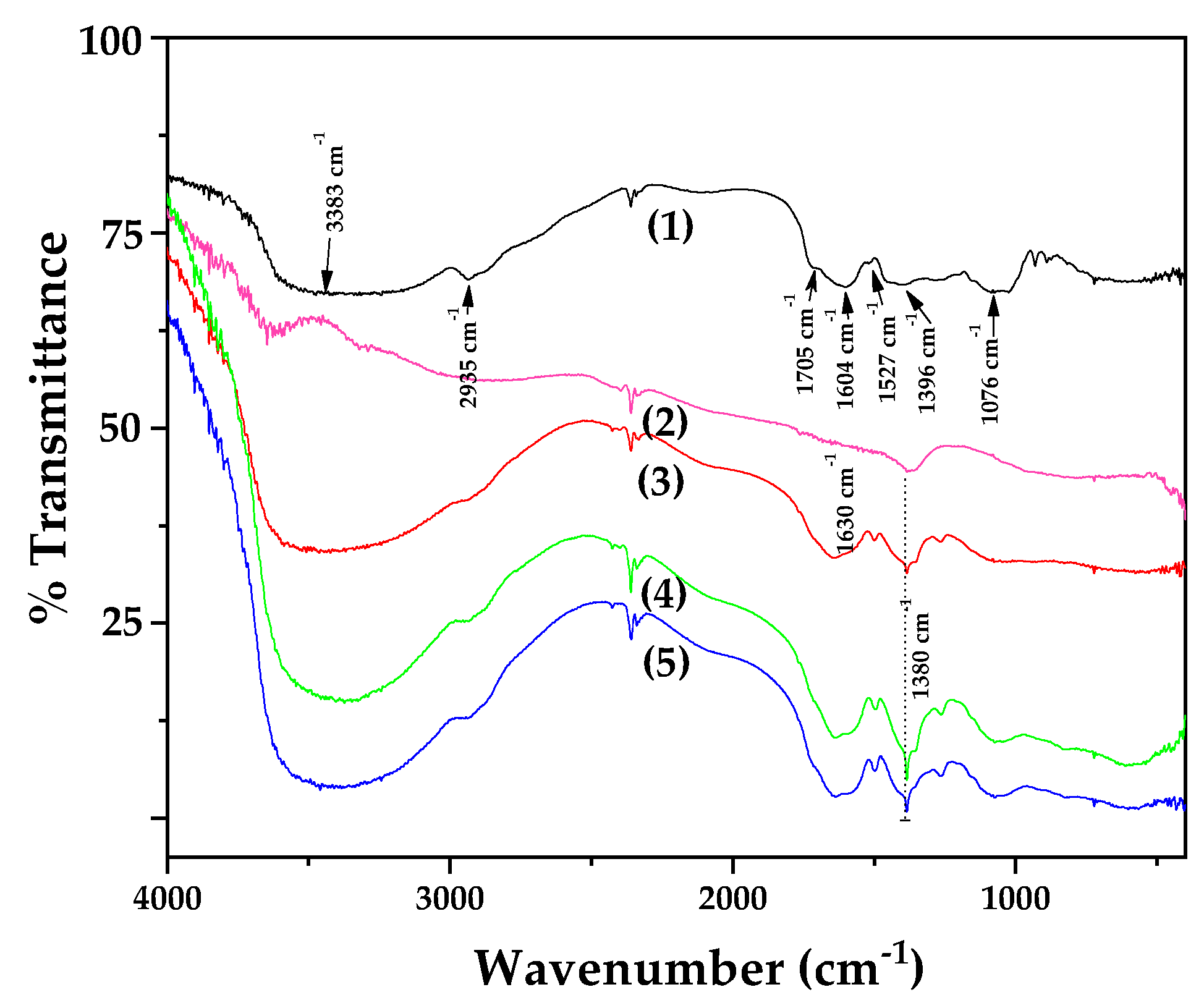

3.2.2. FTIR of OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 Nanohybrids

Figure 2 displays the FTIR spectra of all synthesized OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids, along with those of pure LDH_NaNO₃_Zn/Al and pure OLE for comparison.

The FTIR spectrum of pure OLE (plot line 1) displays several absorption peaks, reflecting its complex chemical composition. The peak at 3383 cm

−1 can be attributed to the N–H stretching vibration of amino groups and also indicates the presence of bonded hydroxyl (-OH) group [

51]. The absorption peak at 2935 cm

−1 corresponds to –CH stretching vibrations of both –CH

3 and –CH

2 functional groups [

51,

52,

53,

54]. The shoulder peak at 1705 cm

-1 is assigned to the C=O stretching vibration of carboxylic acids. These two prominent bands at 3383 and 1705 cm

-1 are characteristic of the O–H and C=O stretching modes, potentially originating from compounds such as οleur, apig-4-o-glu and/or lut-7-ο-glu [

51,

52,

55,

56]. The peak at 1604 cm

−1 lies within the fingerprint region and is associated with the presence of CO, C–O and O–H functional groups found in OLE [

4]. Specifically, it can be attributed to C–O stretching in carboxyl groups coupled with the amide I linkage. The band at 1527 cm

-1, characteristic of amide II arises from N-H stretching modes in the amide linkage [

57]. The peak at 1396 cm

-1 is attributed to methylene scissoring vibrations associated with protein content. A strong band at 1076 cm

-1 is assigned to C-N stretching vibrations of aliphatic amines or C-OH vibrations in proteins derived from olive leaves [

51,

52,

55,

56,

58].

In the FTIR spectra of all synthesized LDHs (plot lines 2, 3, 4 and 5) characteristic bands of hydrotalcite-like compounds are revealed. The broad and intense band centered at 3620 cm

−1 is attributed to the stretching of OH groups and adsorbed H

2O molecules [

59]. The region between 603-430 cm

-1 corresponds to Al-O and Zn-O vibrational modes [

59]. Additionally, a weak band at 1630 cm

−1 is attributed to the bending vibration of interlayer water molecules. [

59]. The FTIR spectrum of LDH_NaNO

3_Zn/Al reveals a strong peak near 1380 cm

−1 , corresponding to the antisymmetric stretching mode (v

3) of nitrate anions present in the LDH structure [

59]. Comparing the FTIR spectra of pure LDH_NaNO

3_Zn/Al with those of all OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids reveals a significant difference: a large, broad peak around 3500 cm

-1 appears in all nanohybrid spectra. This peak results from overlapping hydroxyl group vibrations from both the LDH and OLE, indicating strong interactions between the intercalated hydroxyl groups of OLE and the internal hydroxyl groups of the LDH platelets.

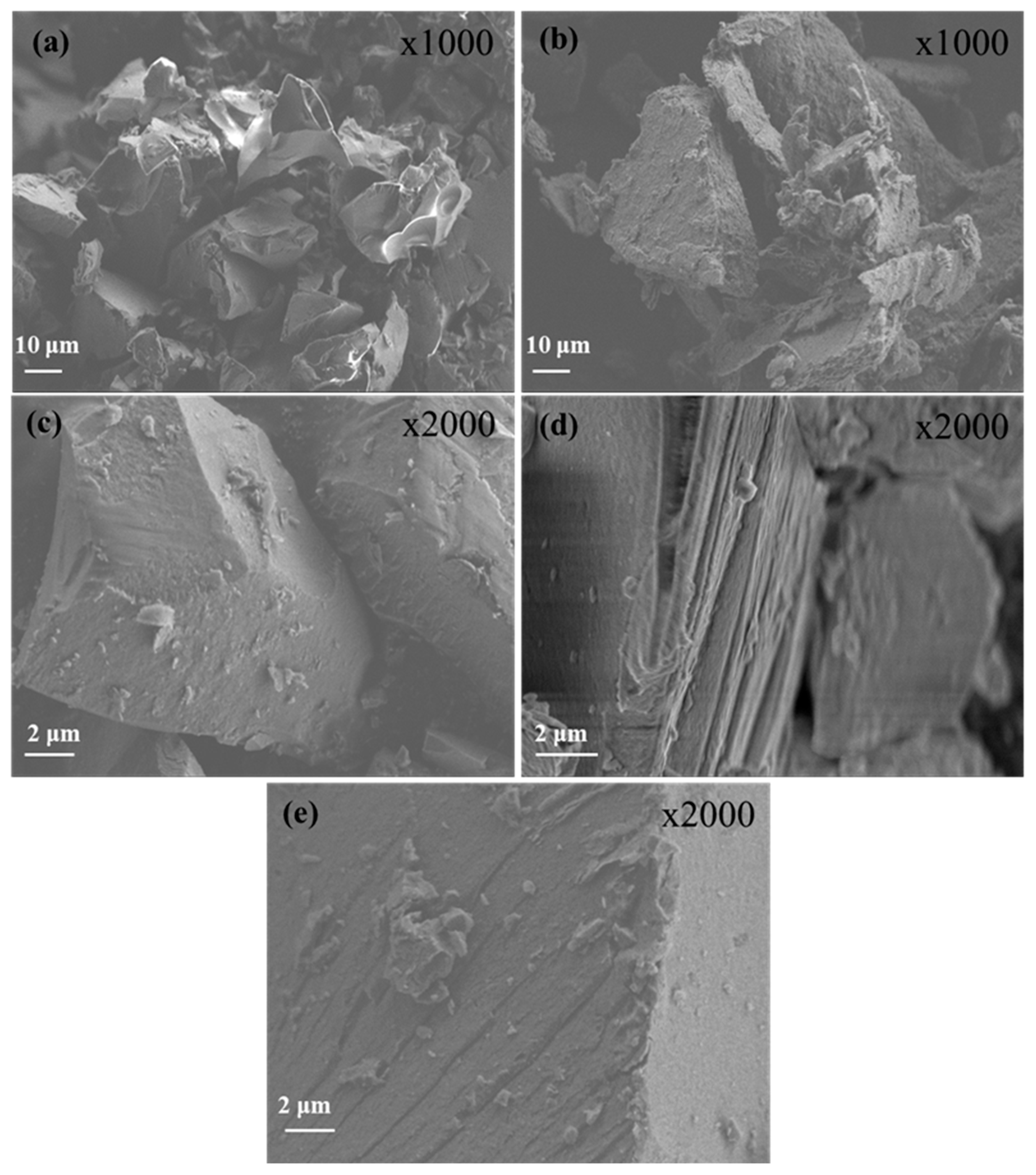

3.2.3. HR-SEM Analysis of OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 Nanohybrids

The morphological characteristics of pure OLE and LDH along with the corresponding nanohybrids are presented in

Figure 3. Representative images of pure freeze-dried OLE and LDH are shown in Figures 3a and 3b, respectively. Pure freeze-dried OLE structure has a sponge-like structure with large holes which indicate the evaporated water molecules. Pure LDH structure reveal an irregular disk-like or flakes-like morphology with obvious lamellar structure, which is a typical characteristic of LDH nanostructures [

60,

61]. Larger platelets or clusters of LDH are also observed indicating their tendency to agglomerate or overlap due to interlayer forces and particle-particle interactions [

61,

62]. The SEM images of LDH-modified nanohybrids (see images in

Figure 3c, d, and e) reveal notable morphological changes compared to the unmodified nanostructures. In all OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids, large sandwich-like particles are observed, suggesting successful OLE intercalation and particle agglomeration. Additionally, irregular nanostructures or particles appear on the surface of the LDH layers, which can be attributed to the OLE nanostructure. Among the nanohybrids, the sandwich-like morphology is most pronounced in OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_2/1. This observation is consistent with the XRD results, which indicate that the most favorable platelet orientation occurs in the OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_2/1 nanohybrid.

3.3. Antioxidant Activity of OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 Nanohybrids

Antioxidant activity of all obtained OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids as well as pure OLE was evaluated via DPPH, ABTS and FRAP assay method and the determination of effective concentration for 50% antioxidant activity (EC

50). Calculated mean values of EC

50,DPPH, EC

50,ABTS, and EC

50,FRAP are listed in

Table 2 for comparison.

As it is shown

Table 2, the EC

50 values measured via different assay method follow the same trend for all OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids. Thus, OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_1/1 exhibited the lowest EC

50,DPPH, EC

50,ABTS, and EC

50,FRAP values while OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_3/1 exhibited the highest EC

50,DPPH, EC

50,ABTS, and EC

50,FRAP values. Statistical hypothesis analysis shown that in all cases of EC

50 parameters the mean value of OLE, OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_1/1, and OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_2/1 were statistically equal while the only statistically different value occurred for the sample OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_3/1. An exception occurs in the case of EC

50,FRAP measurements where OLE and OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_1/1 samples exhibited statistically equal mean values while the OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_2/1 and OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_3/1 samples exhibited statistically different mean values. This result indicates that as the Zn/Al molar ratio increases, the EC

50,DPPH, EC

50,ABTS, and EC

50,FRAP values also increase, reflecting a corresponding decrease in antioxidant activity. This trend can be attributed to the increasing positive charge of the LDH layers as the Zn content decreases. More positively charged LDH sheets can intercalate a greater amount of negatively charged polyphenols from the OLE, which explains the superior antioxidant performance of the OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_1/1 nanohybrid [

63,

64].

The Zn/Al molar ratio is well known to influence the photocatalytic, optical, and dielectric properties of Zn–Al LDHs [

65]. Herein, it is reported for the first time that this ratio also plays a critical role in determining the antioxidant capacity of OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids. Furthermore, as shown in

Figure 4, the antioxidant capacity of the OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_1/1 nanohybrid exceeds that of the pure freeze-dried OLE, suggesting a possible synergistic effect between the antioxidant activity of the nanoencapsulated polyphenols and that of the Zn/Al LDH matrix.

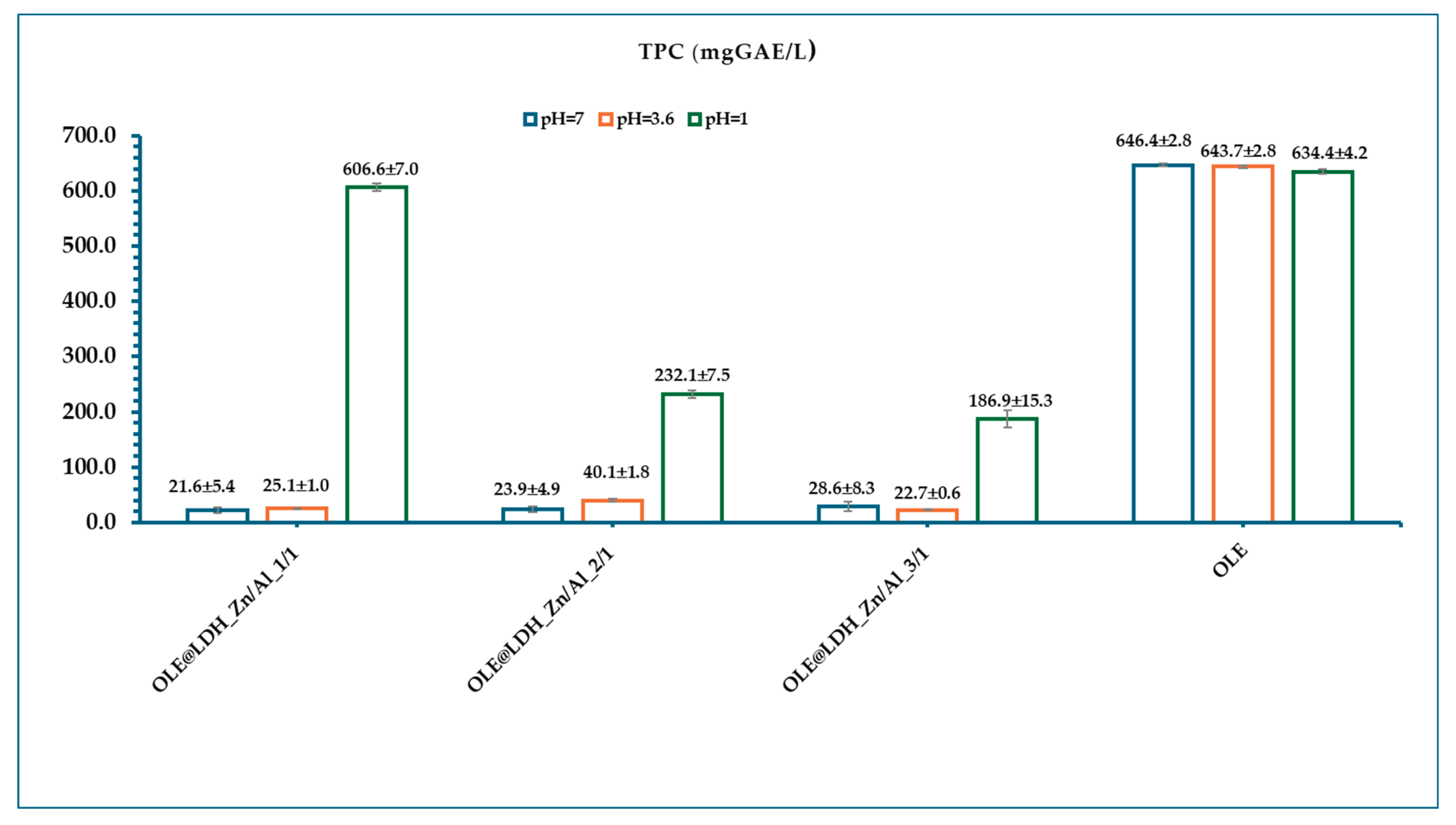

3.4. Total Polyphenols Content (TPC) of OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 Nanohybrids

Figure 4 presents the calculated mean TPC values of all OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids at pH=7, 3.6, and 1. As shown in Figure 5, pure OLE exhibits high mean TPC values of 646.4±2.8, 643.7±2.8, and 634.4±4.2 mg GAE/L at pH=7, 3.6, and 1, respectively, indicating that polyphenols remain stable across a wide pH range. In contrast, all OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids show very low TPC values at pH=7 and 3.6, suggesting that the polyphenols remain encapsulated within the LDH interlayers and are not released into the surrounding medium. However, at pH=1, a significant increase in TPC is observed for all nanohybrids, with mean values of 606.6±7.0 mg GAE/L for OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_1/1, 232.1±7.5 mg GAE/L for OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_2/1, and 186.9±15.3 mg GAE/L for OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_3/1. This confirms that under acidic conditions, mimicking the stomach environment (pH=1.2–1.8), the LDH structure disintegrates, releasing the encapsulated polyphenols. These findings demonstrate that the LDH nanocarriers effectively protect the OLE polyphenols at neutral and slightly acidic pH, while enabling their controlled release in gastric conditions, supporting their potential use in nutritional and biomedical applications [

66,

67].

Moreover, the TPC trends align with the antioxidant activity results: both EC₅₀ and TPC values follow the same pattern, with OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_1/1 exhibiting the highest values. This further supports that the 1:1 Zn/Al molar ratio yields the most positively charged LDH layers, allowing greater polyphenol loading and thus superior antioxidant performance.

3.5. Antibacterial Activity of OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 Nanohybrids

The antibacterial activity results of all OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids against

E. coli and

S. aureus, assessed by ZOI, MIC and MBC, are summarized in

Table 3 for comparison. As shown, all nanohybrids demonstrated significant antibacterial activity against both bacterial strains across all methods. These findings are consistent with previous studies in which OLE encapsulated in maltodextrin-based and maltodextrin/casein-based matrices exhibited notable antibacterial activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria [

68,

69]. Among the three assessment methods, MIC and MBC are considered more reliable for drawing comparative conclusions on antibacterial efficacy [

70,

71]. Based on these metrics, the OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_1/1 nanohybrid exhibited the strongest antibacterial activity against both

E. coli and

S. aureus. This result aligns with its highest TPC and lowest EC₅₀ values, further validating the enhanced bioactivity of this formulation and supporting the overall findings of the study.

4. Discussion

In this study, olive leaf valorization was achieved through an environmentally friendly enzyme-assisted extraction method, yielding an aqueous, polyphenol-rich olive leaf extract containing HT (0.53 mg/L), lut-7-ο-glu (0.70 mg/L), apig-4-ο-glu (0.18 mg/L) and oleur (4.24 mg/L). Olive leaves, typically considered agricultural and industrial waste, possess significant potential for economic and medicinal applications [

68,

69,

72,

73]. While previous studies have explored the extraction of OLE using various solvent systems, including ethanol or ethanol/water mixtures with acetic acid the enzyme-assisted aqueous extraction used here offers a simpler, greener, and more cost-effective alternative[

69,

73]. For instance, Tarchi et al. (2025) [

68] produced an oleuropein-rich aqueous extract with a TPC of 395.45±8.21 mg GAE/g via autoclave, a method that although effective is more complex and expensive than the one employed in this work. Following extraction, the OLE was nano-encapsulated in LDHs by varying the Zn²⁺/Al³⁺ molar ratio to 1:1, 2:1, and 3:1. Previous encapsulation efforts utilized organic matrices. For example, Medfai et al. (2023) [

69] encapsulated ethanolic OLE using spray-drying with maltodextrin-based systems. Oliveira et al. (2022) [

73] used gelatin/tragacanth gum blends, and Tarchi et al. (2025) [

68] employed maltodextrin and sodium caseinate to enhance compound stability and bioavailability. This work, however, is the first to report the successful nanoencapsulation of OLE in inorganic LDH nanocarriers.

The obtained OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_1/1, OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_2/1, and OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_3/1 nanohybrids physiochemically characterized via XRD, FTIR and SEM analysis which clearly shown the incorporation of OLE inside the interlayer space of LDHs in all cases to obtain intercalated nanocomposite structures. Both antioxidant and antibacterial activity tests revealed that OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_1/1 nanohybrid has the lowest the lowest EC50,DPPH, EC50,ABTS, and EC50,FRAP values (27.88±1.82, 25.70±0.76, and 39.42±2.16mg/mL), and the highest MIC (3.12-1.56 mg/mL) and MBC (12.5-6.25 mg/mL) values against E. Coli and S. Aureus correspondingly. The antioxidant and antibacterial result align with the highest TPC (606.6 ± 7.0 mgGAE/L) value also obtained for OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_1/1 nanohybrid. The highest antioxidant antibacterial activity of OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_1/1 nanohybrid in line with its highest TPC capacity exhibited due to its highest positive sheets of LDH which can intercalate more negative charged OLE amount.

Thus, this study not only reports, for the first time, the preparation and characterization of OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids, but also identifies the 1:1 Zn²⁺/Al³⁺ molar ratio as the most effective formulation for OLE encapsulation. Moreover, TPC measurements at various pH levels clearly demonstrated that the encapsulated OLE is well protected at neutral (pH= 7) and mildly acidic (pH=3.6) conditions, and is effectively released under highly acidic conditions (pH=1), mimicking the gastric environment.

Overall, this work demonstrates that (i) LDHs are highly promising nanocarriers for the encapsulation and controlled release of OLE under stomach-like conditions, and (ii) the OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_1/1 nanohybrid exhibits strong potential for future applications in nutrition, food preservation, and biomedicine.

5. Conclusions

This work introduces an efficient, green valorization strategy for olive leaves via enzymatic-assisted extraction, yielding a polyphenol-rich OLE containing HT, lut-7-ο-glu, apig-4-ο-glu and oleur. For the first time, this extract was successfully nanoencapsulated into LDHs at varying Zn²⁺/Al³⁺ molar ratios. Comprehensive structural and functional characterizations confirmed the formation of intercalated nanohybrids, with the 1:1 Zn/Al ratio (OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_1/1) demonstrating superior performance. This hybrid exhibited the highest total polyphenol content, the strongest antioxidant activity, and the most potent antibacterial effect among the tested formulations. Furthermore, pH-responsive release studies revealed that OLE polyphenols are effectively retained within the LDH interlayers under neutral and mildly acidic conditions, and are selectively released under acidic conditions mimicking gastric pH. These findings underscore the potential of LDH-based nanohybrids as effective delivery systems for plant-derived polyphenols, with promising applications in food preservation, nutrition, and biomedicine.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/doi/s1, Figure S1: Calibration curves obtained for (a) HT, (b) lut-7-ο-glu, (c) apig-4-o-glu, and (d) oleur.; Figure S2: HPLC-DAD chromatogram of pure oleur recorded at 280 nm.; Figure S3: Linear plots used for the calculation of average values of EC

50,DPPH; Figure S4: Linear plots used for the calculation of average values of EC

50,ABTS; Figure S5: Linear plots used for the calculation of average values of EC

50,FRAP; Figure S6: Results from three independent replicates for the determination of the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of all OLE@LDH_Zn/Al_x/1 nanohybrids against

E. coli and

S. aureus. Representative images from the resazurin-based 96-well plate microdilution method used for MBC determination are also shown..; Table S1: Experimental data used for the calculation of obtained average EC

50,DPPH values; Table S2: Experimental data used for the calculation of obtained average EC

50,ABTS values; Table S3: Experimental data used for the calculation of obtained average EC

50,FRAP values; Table S4: Statistical analysis results of EC

50,DPPH values; Table S5: Statistical analysis results of EC

50,ABTS values; Table S6: Statistical analysis results of EC

50,FRAP values; Table S7: Statistical analysis results of TPC values.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization—C.E.S. and A.E.G.; data curation—A.V., A.A.L., P.St., M.X., P.S., N.C., A.E.G. and C.E.S.; formal analysis—A.K., A.A.L., P.St., C.P., E.P.G., A.E.G., and C.E.S.; investigation—A.K., A.A.L., N.C., M.X., P.S., C.P., E.P.G., C.E.S., and A.E.G.; methodology—A.K., A.A.L., P.St., M.X., P.S., N.C., C.E.S., and A.E.G.; project administration—C.E.S., and A.E.G.; resources—A.K., A.A.L., N.C., C.E.S., and A.E.G.; software—A.V., A.A.L., N.C., C.E.S., and A.E.G.; supervision—C.E.S., and A.E.G.; validation—A.K., A.A.L., N.C., E.P.G., C.E.S., and A.E.G..; visualization—A.K., N.C., C.E.S., and A.E.G.; writing, original draft—N.C., C.E.S., A.E.G. and A.E.G.; writing, review and editing—A.K., N.C., A.A.L., C.E.S., and A.E.G.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are expressed to Prof. Skaltsounis Alexios-Leandros, Director of the Laboratory of Valorization of Bioactive Natural Product, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Athens, for his insightful comments and valuable contribution to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cooney, R.; de Sousa, D.B.; Fernández-Ríos, A.; Mellett, S.; Rowan, N.; Morse, A.P.; Hayes, M.; Laso, J.; Regueiro, L.; Wan, A.HL.; et al. A Circular Economy Framework for Seafood Waste Valorisation to Meet Challenges and Opportunities for Intensive Production and Sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 392, 136283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, B.; Sessa, M.R.; Sica, D.; Malandrino, O. Towards Circular Economy in the Agri-Food Sector. A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamam, M.; Chinnici, G.; Di Vita, G.; Pappalardo, G.; Pecorino, B.; Maesano, G.; D’Amico, M. Circular Economy Models in Agro-Food Systems: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panáček, D.; Zdražil, L.; Langer, M.; Šedajová, V.; Baďura, Z.; Zoppellaro, G.; Yang, Q.; Nguyen, E.P.; Álvarez-Diduk, R.; Hrubý, V.; et al. Graphene Nanobeacons with High-Affinity Pockets for Combined, Selective, and Effective Decontamination and Reagentless Detection of Heavy Metals. Small 2022, 18, 2201003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rontogianni, A.; Chalmpes, Ν.; Nikolaraki, E.; Botzolaki, G.; Androulakis, A.; Stratakis, A.; Zygouri, P.; Moschovas, D.; Avgeropoulos, A.; Karakassides, M.A.; et al. Efficient CO2 Hydrogenation over Mono- and Bi-Metallic RuNi/MCM-41 Catalysts: Controlling CH4 and CO Products Distribution through the Preparation Method and/or Partial Replacement of Ni by Ru. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 474, 145644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cansado, I.P. da P.; Mourão, P.A.M.; Castanheiro, J.E.; Geraldo, P.F.; Suhas; Suero, S.R.; Cano, B.L. A Review of the Biomass Valorization Hierarchy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, N.C.; Sinha, S.; Bhatnagar, P.; Nath, Y.; Negi, B.; Kumar, V.; Gururani, P. A Concise Review on Waste Biomass Valorization through Thermochemical Conversion. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2024, 6, 100237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areti, H.A.; Muleta, M.D.; Abo, L.D.; Hamda, A.S.; Adugna, A.A.; Edae, I.T.; Daba, B.J.; Gudeta, R.L. Innovative Uses of Agricultural By-Products in the Food and Beverage Sector: A Review. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 5, 100838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.T.; Khong, N.M.H.; Lim, S.S.; Hee, Y.Y.; Sim, B.I.; Lau, K.Y.; Lai, O.M. A Review: Modified Agricultural by-Products for the Development and Fortification of Food Products and Nutraceuticals. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 59, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruff, A.J. Food Industry Side Streams: An Unexploited Source for Biotechnological Phosphorus Upcycling. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2024, 90, 103209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, I.; Leue-Rüegg, R.; Beretta, C.; Müller, N. Valorisation Potential and Challenges of Food Side Product Streams for Food Applications: A Review Using the Example of Switzerland. Future Foods 2024, 9, 100325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmpes, N.; Tantis, I.; Alsmaeil, A.W.; Aldakkan, B.S.; Dimitrakou, A.; Karakassides, M.A.; Salmas, C.E.; Giannelis, E.P. Elevating Waste Biomass: Supercapacitor Electrode Materials Derived from Spent Coffee Grounds. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 1305–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillard, V.; Gaucel, S.; Fornaciari, C.; Angellier-Coussy, H.; Buche, P.; Gontard, N. The Next Generation of Sustainable Food Packaging to Preserve Our Environment in a Circular Economy Context. Front. Nutr. 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Sharma, S.; Kumar Nadda, A.; Saad Bala Husain, M.; Gupta, A. Biopolymers from Waste Biomass and Its Applications in the Cosmetic Industry: A Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 68, 873–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maqtari, Q.A.; Rehman, A.; Mahdi, A.A.; Al-Ansi, W.; Wei, M.; Yanyu, Z.; Phyo, H.M.; Galeboe, O.; Yao, W. Application of Essential Oils as Preservatives in Food Systems: Challenges and Future Prospectives – a Review. Phytochem. Rev. 2022, 21, 1209–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Souza, F.; Magalhães, I.F.B.; Guedes, A.C.; Santana, V.M.; Teles, A.M.; Mouchrek, A.N.; Calabrese, K.S.; Abreu-Silva, A.L. Safety Assessment of Essential Oil as a Food Ingredient. In Essential Oils: Applications and Trends in Food Science and Technology; Santana de Oliveira, M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 123–171. ISBN 978-3-030-99476-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bakkali, F.; Averbeck, S.; Averbeck, D.; Idaomar, M. Biological Effects of Essential Oils – A Review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 446–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, E.; Oliveira, J.; Perez-Gregorio, R. Editorial: Natural Extracts as Food Ingredients: From Chemistry to Health. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, H.; Weng, Y. Natural Extracts and Their Applications in Polymer-Based Active Packaging: A Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakas, A.E. Plant Extracts-Based Food Packaging Films. In Natural Materials for Food Packaging Application; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2023; pp. 23–49 ISBN 978-3-527-83730-4.

- Giannakas, A.E. 7 - Bionanocomposites with Hybrid Nanomaterials for Food Packaging Applications. In Advances in Biocomposites and their Applications; Karak, N., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Composites Science and Engineering; Woodhead Publishing, 2024; pp. 201–225 ISBN 978-0-443-19074-2.

- Deshmukh, R.K.; Hakim, L.; Akhila, K.; Ramakanth, D.; Gaikwad, K.K. Nano Clays and Its Composites for Food Packaging Applications. Int. Nano Lett. 2023, 13, 131–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinka, T.A.; Edwards, F.B.; Miranda, N.R.; Speer, D.V.; Thomas, J.A. Zeolite in Packaging Film 1997.

- Salmas, C.E.; Giannakas, A.E.; Karabagias, V.K.; Moschovas, D.; Karabagias, I.K.; Gioti, C.; Georgopoulos, S.; Leontiou, A.; Kehayias, G.; Avgeropoulos, A.; et al. Development and Evaluation of a Novel-Thymol@Natural-Zeolite/Low-Density-Polyethylene Active Packaging Film: Applications for Pork Fillets Preservation. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, S.; Soni, S.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, V.; Jaswal, V.S.; Bhatia, S.K.; Sharma, A.K. Layered Double Hydroxides Based Composite Materials and Their Applications in Food Packaging. Appl. Clay Sci. 2024, 247, 107216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, S.; Thomas, S. 1 - Layered Double Hydroxides: Fundamentals to Applications. In Layered Double Hydroxide Polymer Nanocomposites; Thomas, S., Daniel, S., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Composites Science and Engineering; Woodhead Publishing, 2020; pp. 1–76 ISBN 978-0-08-102261-0.

- Alexandre, M.; Dubois, P. Polymer-Layered Silicate Nanocomposites: Preparation, Properties and Uses of a New Class of Materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2000, 28, 1–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmpes, N.; Kouloumpis, A.; Zygouri, P.; Karouta, N.; Spyrou, K.; Stathi, P.; Tsoufis, T.; Georgakilas, V.; Gournis, D.; Rudolf, P. Layer-by-Layer Assembly of Clay–Carbon Nanotube Hybrid Superstructures. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 18100–18107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, L.H.; Trigueiro, P.; Souza, J.S.N.; de Carvalho, M.S.; Osajima, J.A.; da Silva-Filho, E.C.; Fonseca, M.G. Montmorillonite with Essential Oils as Antimicrobial Agents, Packaging, Repellents, and Insecticides: An Overview. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 209, 112186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, R.K.; Kumar, L.; Gaikwad, K.K. Halloysite Nanotubes for Food Packaging Application: A Review. Appl. Clay Sci. 2023, 234, 106856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha Roy, A.; Kesavan Pillai, S.; Ray, S.S. Layered Double Hydroxides for Sustainable Agriculture and Environment: An Overview. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 20428–20440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghotbi, M.Y.; Hussein, M.Z. bin; Yahaya, A.H.; Rahman, M.Z.A. LDH-Intercalated d-Gluconate: Generation of a New Food Additive-Inorganic Nanohybrid Compound. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2009, 70, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugatti, V.; Bernardo, P.; Clarizia, G.; Viscusi, G.; Vertuccio, L.; Gorrasi, G. Ball Milling to Produce Composites Based of Natural Clinoptilolite as a Carrier of Salicylate in Bio-Based PA11. Polymers 2019, 11, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Dasgupta, S.; Maji, K. MgAl- Layered Double Hydroxide Nanoparticles for Controlled Release of Salicylate. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 68, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisawa, S.; Higashiyama, N.; Takahashi, S.; Hirahara, H.; Ikematsu, D.; Kondo, H.; Nakayama, H.; Narita, E. Intercalation Behavior of L-Ascorbic Acid into Layered Double Hydroxides. Appl. Clay Sci. 2007, 35, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmanian, O.; Dinari, M.; Neamati, S. Synthesis and Characterization of Citrate Intercalated Layered Double Hydroxide as a Green Adsorbent for Ni2+ and Pb2+ Removal. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 36267–36277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintieri, L.; Bugatti, V.; Caputo, L.; Vertuccio, L.; Gorrasi, G. A Food-Grade Resin with LDH–Salicylate to Extend Mozzarella Cheese Shelf Life. Processes 2021, 9, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugatti, V.; Vertuccio, L.; Zuppardi, F.; Vittoria, V.; Gorrasi, G. PET and Active Coating Based on a LDH Nanofiller Hosting P-Hydroxybenzoate and Food-Grade Zeolites: Evaluation of Antimicrobial Activity of Packaging and Shelf Life of Red Meat. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscusi, G.; Bugatti, V.; Vittoria, V.; Gorrasi, G. Antimicrobial Sorbate Anchored to Layered Double Hydroxide (LDH) Nano-Carrier Employed as Active Coating on Polypropylene (PP) Packaging: Application to Bread Stored at Ambient Temperature. Future Foods 2021, 4, 100063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugatti, V.; Vertuccio, L.; Zara, S.; Fancello, F.; Scanu, B.; Gorrasi, G. Green Pesticides Based on Cinnamate Anion Incorporated in Layered Double Hydroxides and Dispersed in Pectin Matrix. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 209, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalawade, P.; Aware, B.; Kadam, V.; Hirlekar, R. Layered Double Hydroxides: A Review. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mir-Cerdà, A.; Granados, M.; Saurina, J.; Sentellas, S. Olive Tree Leaves as a Great Source of Phenolic Compounds: Comprehensive Profiling of NaDES Extracts. Food Chem. 2024, 456, 140042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debs, E.; Abi-Khattar, A.-M.; Rajha, H.N.; Abdel-Massih, R.M.; Assaf, J.-C.; Koubaa, M.; Maroun, R.G.; Louka, N. Valorization of Olive Leaves through Polyphenol Recovery Using Innovative Pretreatments and Extraction Techniques: An Updated Review. Separations 2023, 10, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardakas, A.; Kechagias, A.; Penov, N.; Giannakas, A.E. Optimization of Enzymatic Assisted Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Olea Europaea Leaves. Biomass 2024, 4, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOC STANDARDS, METHODS AND GUIDES. Int. Olive Counc.

- Elshikh, M.; Ahmed, S.; Funston, S.; Dunlop, P.; McGaw, M.; Marchant, R.; Banat, I.M. Resazurin-Based 96-Well Plate Microdilution Method for the Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Biosurfactants. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016, 38, 1015–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhalfa, N.; Boutahala, M.; Djebri, N. Synthesis and Characterization of ZnAl-Layered Double Hydroxide and Organo-K10 Montmorillonite for the Removal of Diclofenac from Aqueous Solution. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 2017, 35, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.A.A.; Talib, Z.A.; Hussein, M.Z. bin Thermal, Optical and Dielectric Properties of Zn–Al Layered Double Hydroxide. Appl. Clay Sci. 2012, 56, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smalenskaite, A.; Pavasaryte, L.; Yang, T.C.K.; Kareiva, A. Undoped and Eu3+ Doped Magnesium-Aluminium Layered Double Hydroxides: Peculiarities of Intercalation of Organic Anions and Investigation of Luminescence Properties. Materials 2019, 12, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.I.; O’Hare, D. Intercalation Chemistry of Layered Double Hydroxides: Recent Developments and Applications. J. Mater. Chem. 2002, 12, 3191–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agatonovic-Kustrin, S.; Gegechkori, V.; Petrovich, D.S.; Ilinichna, K.T.; Morton, D.W. HPTLC and FTIR Fingerprinting of Olive Leaves Extracts and ATR-FTIR Characterisation of Major Flavonoids and Polyphenolics. Molecules 2021, 26, 6892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir1, G.A.; Mohammed2, A.K.; Samir3, H.F. Biosynthesis and Characterization of Silver Nanoparticles Using Olive Leaves Extract and Sorbitol. Iraqi J. Biotechnol. 2016, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmpes, N.; Bourlinos, A.B.; Talande, S.; Bakandritsos, A.; Moschovas, D.; Avgeropoulos, A.; Karakassides, M.A.; Gournis, D. Nanocarbon from Rocket Fuel Waste: The Case of Furfuryl Alcohol-Fuming Nitric Acid Hypergolic Pair. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouloumpis, A.; Vourdas, N.; Zygouri, P.; Chalmpes, N.; Potsi, G.; Kostas, V.; Spyrou, K.; Stathopoulos, V.N.; Gournis, D.; Rudolf, P. Controlled Deposition of Fullerene Derivatives within a Graphene Template by Means of a Modified Langmuir-Schaefer Method. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 524, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shameli, K.; Ahmad, M.B.; Jazayeri, S.D.; Shabanzadeh, P.; Sangpour, P.; Jahangirian, H.; Gharayebi, Y. Investigation of Antibacterial Properties Silver Nanoparticles Prepared via Green Method. Chem. Cent. J. 2012, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, M.M.H.; Ismail, E.H.; El-Baghdady, K.Z.; Mohamed, D. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Olive Leaf Extract and Its Antibacterial Activity. Arab. J. Chem. 2014, 7, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmpes, N.; Patila, M.; Kouloumpis, A.; Alatzoglou, C.; Spyrou, K.; Subrati, M.; Polydera, A.C.; Bourlinos, A.B.; Stamatis, H.; Gournis, D. Graphene Oxide–Cytochrome c Multilayered Structures for Biocatalytic Applications: Decrypting the Role of Surfactant in Langmuir–Schaefer Layer Deposition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 26204–26215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmpes, N.; Moschovas, D.; Tantis, I.; Bourlinos, A.B.; Bakandritsos, A.; Fotiadou, R.; Patila, M.; Stamatis, H.; Avgeropoulos, A.; Karakassides, M.A.; et al. Carbon Nanostructures Derived through Hypergolic Reaction of Conductive Polymers with Fuming Nitric Acid at Ambient Conditions. Molecules 2021, 26, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahjoubi, F.Z.; Khalidi, A.; Abdennouri, M.; Barka, N. Zn–Al Layered Double Hydroxides Intercalated with Carbonate, Nitrate, Chloride and Sulphate Ions: Synthesis, Characterisation and Dye Removal Properties. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2017, 11, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, H.; Xu, J.; Jaber, F.; Musharavati, F.; Zalnezhad, E.; Bae, S.; Hui, K.S.; Hui, K.N.; Liu, J. Synthesis and Characterization of a NiCo2O4@NiCo2O4 Hierarchical Mesoporous Nanoflake Electrode for Supercapacitor Applications. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, L.; Xue, Y.; Huang, B.; Yu, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, D.; Jia, D.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; et al. Overall Water Splitting by Graphdiyne-Exfoliated and -Sandwiched Layered Double-Hydroxide Nanosheet Arrays. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kechagias, A.; Salmas, C.E.; Chalmpes, N.; Leontiou, A.A.; Karakassides, M.A.; Giannelis, E.P.; Giannakas, A.E. Laponite vs. Montmorillonite as Eugenol Nanocarriers for Low Density Polyethylene Active Packaging Films. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; O’Hare, D. Recent Advances in the Synthesis and Application of Layered Double Hydroxide (LDH) Nanosheets. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 4124–4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanty, U.A.; Sahoo, D.P.; Paramanik, L.; Parida, K. A Critical Review on Layered Double Hydroxide (LDH)-Derived Functional Nanomaterials as Potential and Sustainable Photocatalysts. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2023, 7, 1145–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.A.A.; Talib, Z.A.; bin Hussein, M.Z.; Zakaria, A. Zn–Al Layered Double Hydroxide Prepared at Different Molar Ratios: Preparation, Characterization, Optical and Dielectric Properties. J. Solid State Chem. 2012, 191, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobek, L.; Ištuk, J.; Barron, A.R.; Matić, P. Bioactive Phenolic Compounds from Apples during Simulated In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion: Kinetics of Their Release. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Gao, Z.; Xu, J.; Sun, W.; Wu, J.; Zhu, L.; Gao, M.; Zhan, X. Encapsulation of Polyphenols in pH-Responsive Micelles Self-Assembled from Octenyl-Succinylated Curdlan Oligosaccharide and Its Effect on the Gut Microbiota. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 219, 112857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarchi, I.; Olewnik-Kruszkowska, E.; Aït-Kaddour, A.; Bouaziz, M. Innovative Process for the Recovery of Oleuropein-Rich Extract from Olive Leaves and Its Biological Activities: Encapsulation for Activity Preservation with Concentration Assessment Pre and Post Encapsulation. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 6135–6146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medfai, W.; Oueslati, I.; Dumas, E.; Harzalli, Z.; Viton, C.; Mhamdi, R.; Gharsallaoui, A. Physicochemical and Biological Characterization of Encapsulated Olive Leaf Extracts for Food Preservation. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajic, I.; Kabic, J.; Kekic, D.; Jovicevic, M.; Milenkovic, M.; Mitic Culafic, D.; Trudic, A.; Ranin, L.; Opavski, N. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: A Comprehensive Review of Currently Used Methods. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balouiri, M.; Sadiki, M.; Ibnsouda, S.K. Methods for in Vitro Evaluating Antimicrobial Activity: A Review. J. Pharm. Anal. 2016, 6, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paciulli, M.; Grimaldi, M.; Rinaldi, M.; Cavazza, A.; Flamminii, F.; Mattia, C.D.; Gennari, M.; Chiavaro, E. Microencapsulated Olive Leaf Extract Enhances Physicochemical Stability of Biscuits. Future Foods 2023, 7, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.M.; Oliveira, R.M.; Gehrmann Buchweitz, L.T.; Pereira, J.R.; Cristina dos Santos Hackbart, H.; Nalério, É.S.; Borges, C.D.; Zambiazi, R.C. Encapsulation of Olive Leaf Extract (Olea Europaea L.) in Gelatin/Tragacanth Gum by Complex Coacervation for Application in Sheep Meat Hamburger. Food Control 2022, 131, 108426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).