Submitted:

08 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Plant Material

2.3. Extraction Procedure

2.4. CG-MS Analyses of EOPb

2.5. Preparation of Nanogels

2.6. Stability Assay of Nanogels

2.7. FTIR Analysis

2.8. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

2.9. DLS Analysis

2.10. Rheological Analysis

2.11. In Vitro Assay Against LLa Promastigotes Cells

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

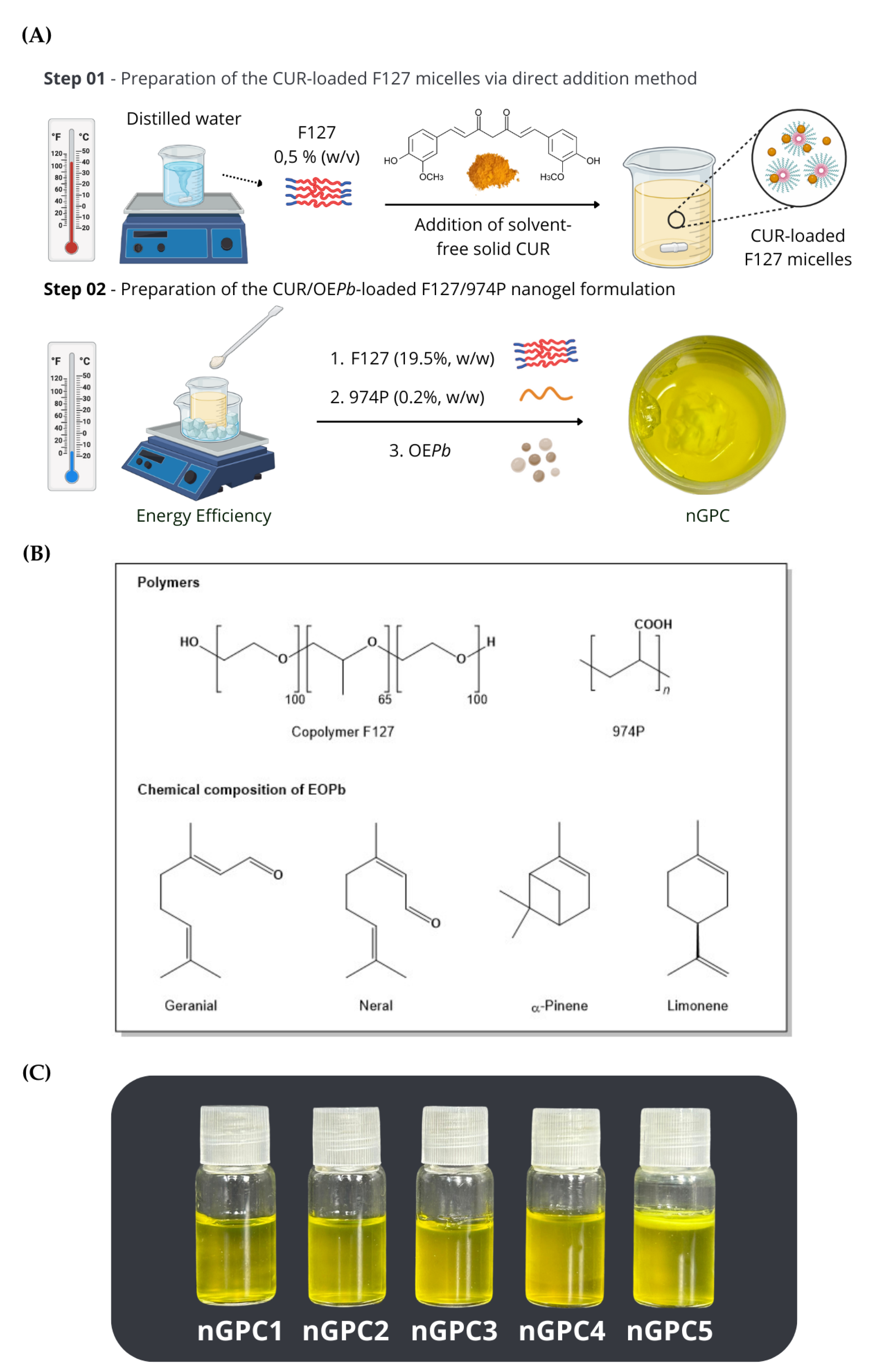

3.1. Development of Nanogels

3.2. Characterization of Nanogels

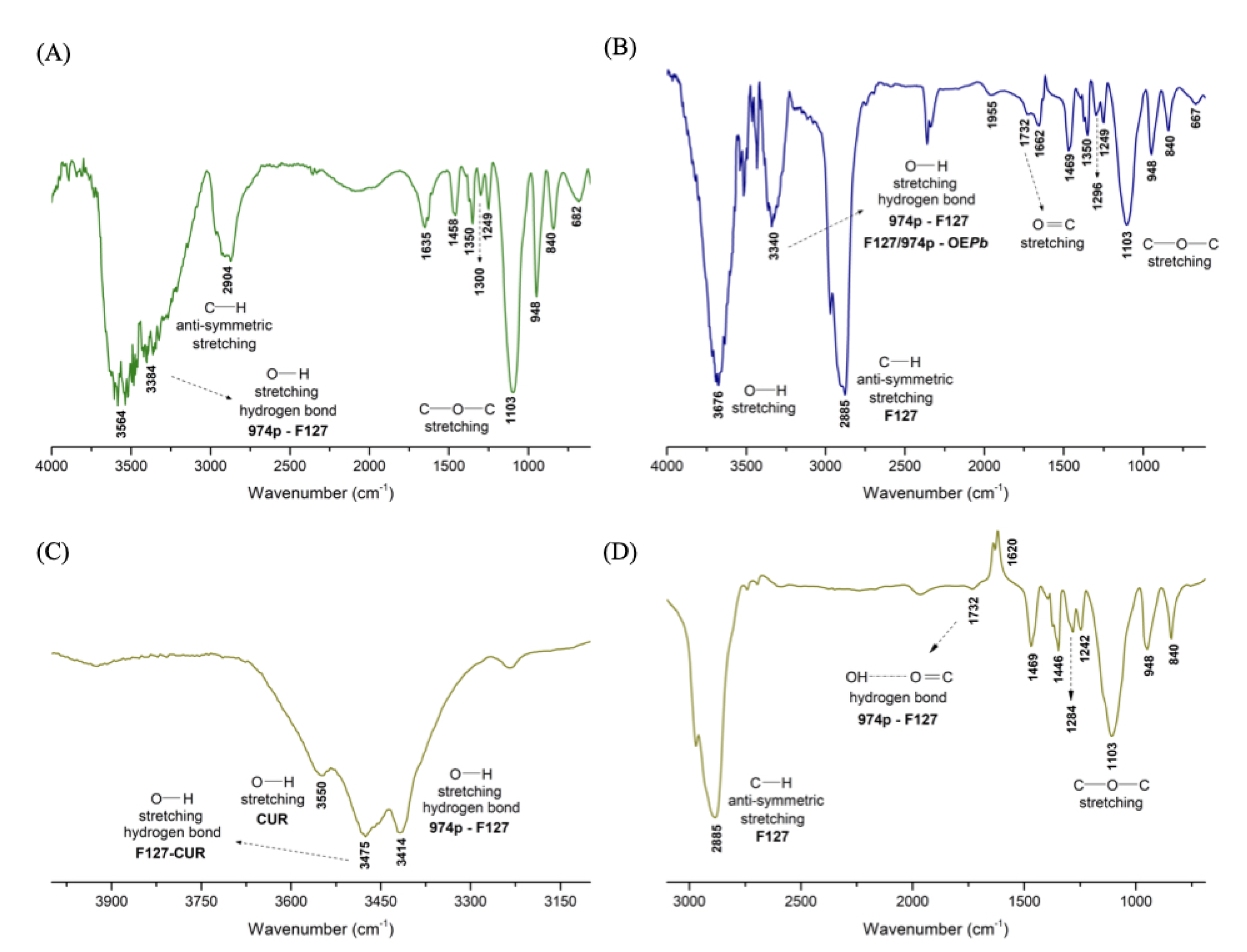

3.2.1. FTIR

3.2.2. SEM

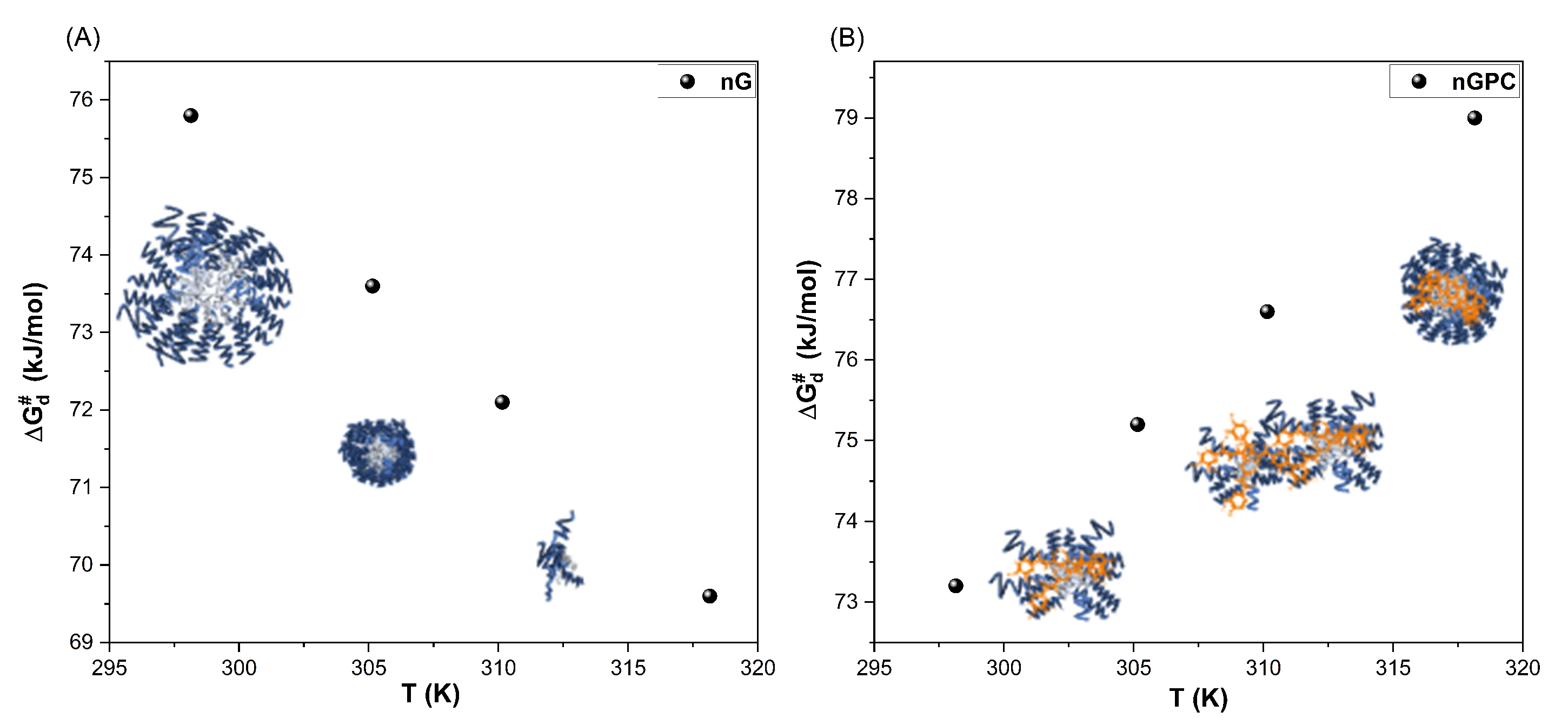

3.2.3. DLS

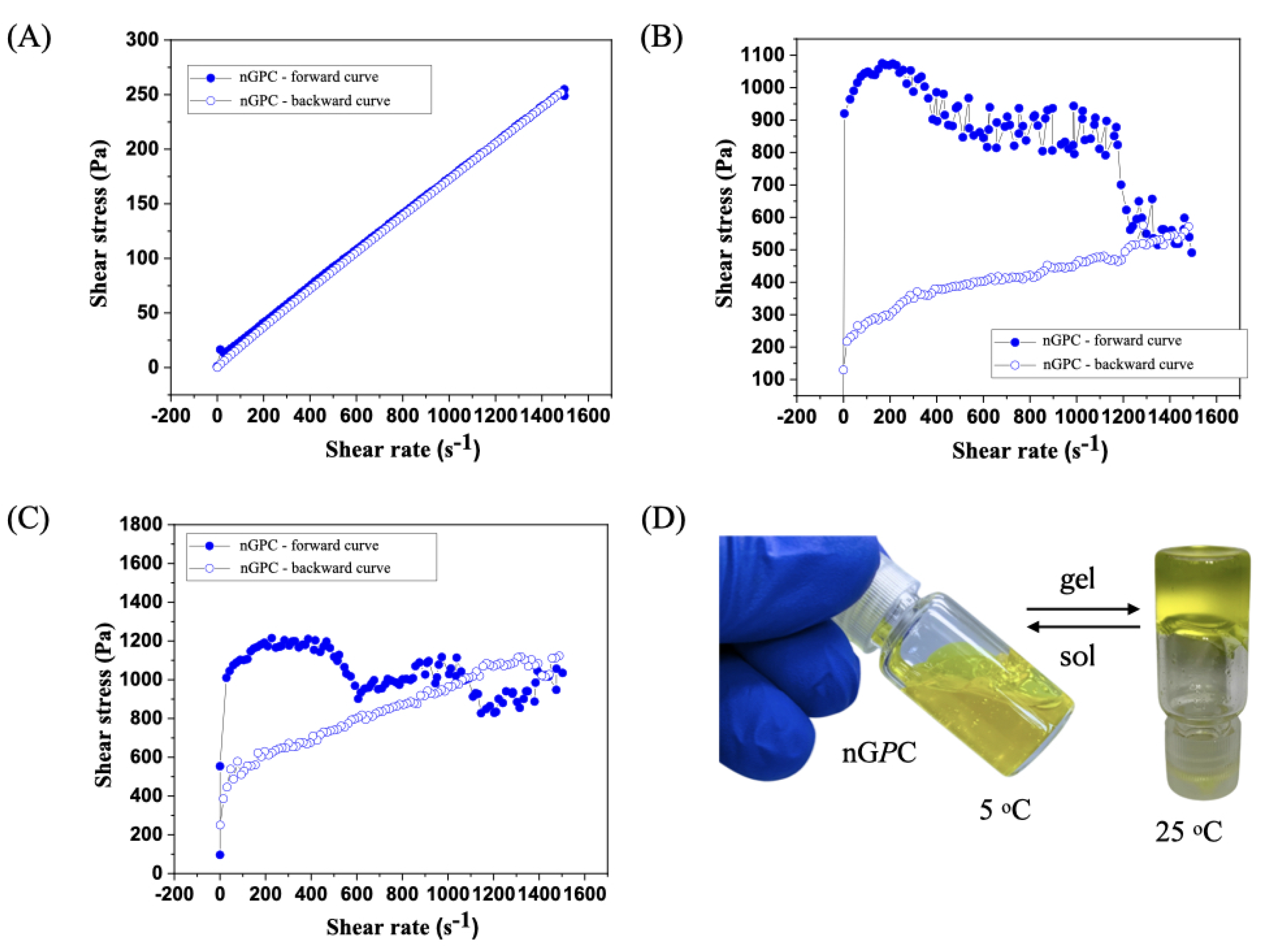

3.3. Rheological Analysis

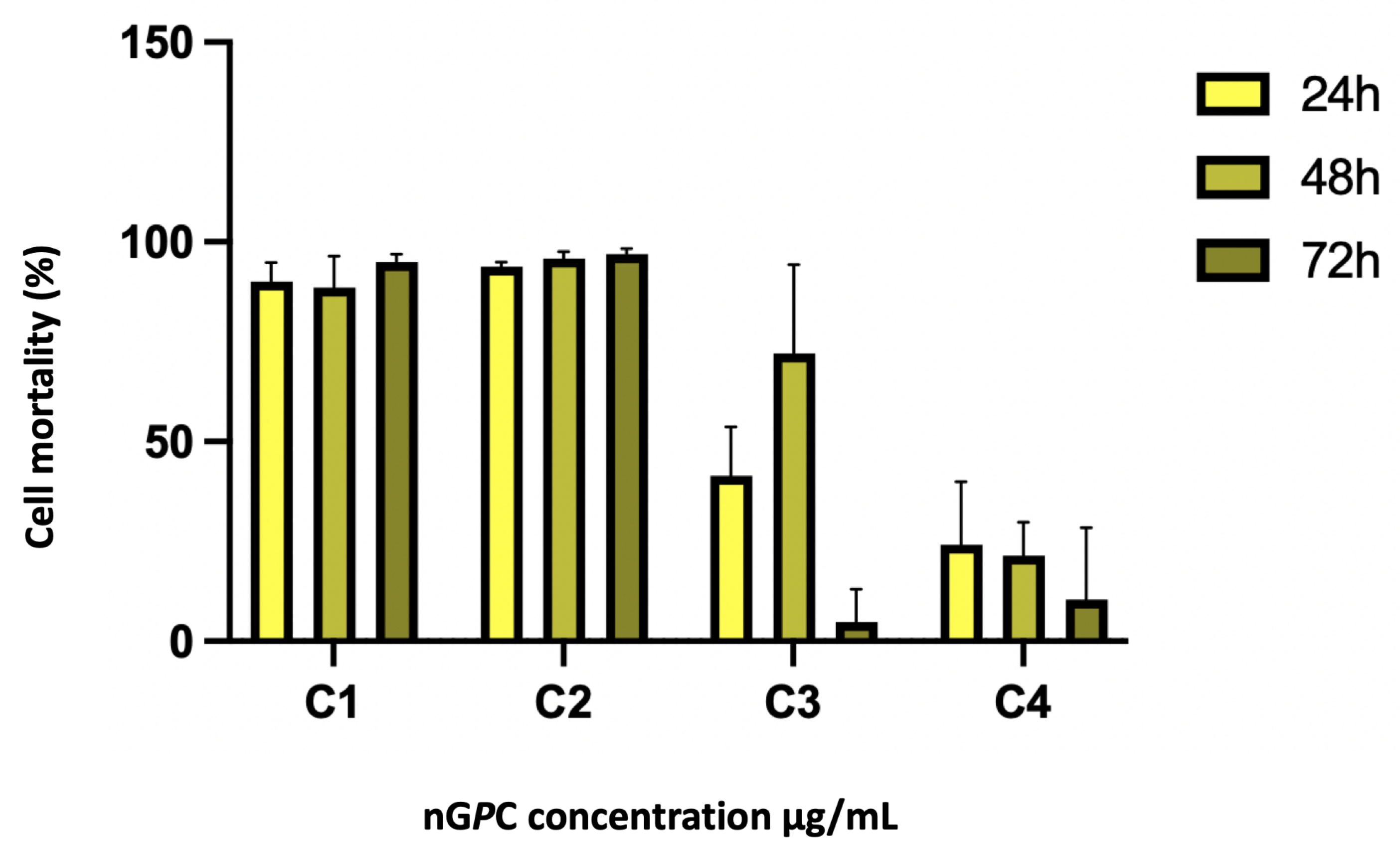

3.4. In Vitro Assay Against LLa Promastigotes

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Neglected tropical diseases. World Health Organization, 2025. Disponível em: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/neglected-tropical-diseases. Acesso em: 2 fev. 2025.

- Hotez, P. J.; Kamath, A. Neglected tropical diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: review of their prevalence, distribution, and disease burden. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2009, 3, e412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molyneux, D. H.; Savioli, L.; Engels, D. Neglected tropical diseases: progress towards addressing the chronic pandemic. The Lancet 2017, 389, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, C.; Nwankwo, U.; Lenk, E.; de Vlas, S. J.; Bundy, D. A. P. An Investment Case for Ending Neglected Tropical Diseases. In Holmes, K. K.; Bertozzi, S., Bloom, B. R., Jha, P. (Eds.) Major Infectious Diseases, Eds.; 3rd ed.; The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank: Washington (DC), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hotez, P.; Aksoy, S. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases: Ten years of progress in neglected tropical disease control and elimination … More or less. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2017, 11, e0005355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezike, T. C.; Okpala, U. S.; Onoja, U. L.; Nwike, C. P.; Ezeako, E. C.; Okpara, O. J.; Okoroafor, C. C.; Eze, S. C.; Kalu, O. L.; Odoh, E. C.; Nwadike, U. G.; Ogbodo, J. O.; Umeh, B. U.; Ossai, E. C.; Nwanguma, B. C. Advances in drug delivery systems, challenges and future directions. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chan, H. F.; Leong, K. W. Advanced materials and processing for drug delivery: The past and the future. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2013, 65, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupolillo, E.; Grimaldi, G. Jr.; Momen, H. A general classification of New World Leishmania using numerical zymotaxonomy. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1994, 50, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, H.; Uezato, H.; Gomez, E. A.; Terayama, Y.; Calvopiña, M.; Iwata, H.; Hashiguchi, Y. Establishment of a mass screening method of sand fly vectors for Leishmania infection by molecular biological methods. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2007, 77, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A. C. L.; Oliveira, D. A. P.; Guimarães, C. L.; et al. Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis: A review of its biology, clinical manifestations, and treatment. Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária 2020, 29, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, S.; Frasca, K.; Scherrer, S.; Henao-Martínez, A. F.; Newman, S.; Ramanan, P.; Suarez, J. A. A Review of Leishmaniasis: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Current Tropical Medicine Reports 2021, 8, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, C. S.; Marques, E. M.; do Nascimento, J. R.; Lima, V. A. S.; Santos-Oliveira, R.; Figueredo, A. S.; de Jesus, C. M.; de Souza Nunes, G. C.; Brandão, C. M.; de Jesus, E. T.; Sa, M. C.; Tanaka, A. A.; Braga, G.; Santos, A. C. F.; de Lima, R. B.; Silva, L. A.; Alencar, L. M. R.; da Rocha, C. Q.; Gonçalves, R. S. Design of Liquid Formulation Based on F127-Loaded Natural Dimeric Flavonoids as a New Perspective Treatment for Leishmaniasis. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, E. M.; Rocha, R. L.; Brandão, C. M.; Xavier, J. K. A. M.; Camara, M. B. P.; Mendonça, C. J. S.; de Lima, R. B.; Souza, M. P.; Costa, E. V.; Gonçalves, R. S. Development of an Eco-Friendly Nanogel Incorporating Pectis brevipedunculata Essential Oil as a Larvicidal Agent Against Aedes aegypti. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, E. M.; Santos Andrade, L. G.; Rebelo Alencar, L. M.; Dias Rates, E. R.; Ribeiro, R. M.; Carvalho, R. C.; de Souza Nunes, G. C.; Sara Lopes Lera-Nonose, D. S.; Gonçalves, M. J. S.; Lonardoni, M. V. C.; Souza, M. P.; Costa, E. V.; Gonçalves, R. S. Nanotechnological formulation incorporating Pectis brevipedunculata (Asteraceae) essential oil: an ecofriendly approach for leishmanicidal and anti-inflammatory therapy. Polymers 2025, 17, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, C. E.; Sobrinho-Junior, E. P.; Brito, L. M.; Nicolau, L. A.; Carvalho, T. P.; Moura, A. K.; Rodrigues, K. A.; Carneiro, S. M.; Arcanjo, D. D.; Citó, A. M.; Carvalho, F. A. Anti-Leishmania activity of essential oil of Myracrodruon urundeuva (Engl.) Fr. All.: composition, cytotoxicity and possible mechanisms of action. Experimental Parasitology 2017, 175, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, O. O.; Cruz, J. N.; de Moraes, Â. A. B.; de Jesus Pereira Franco, C.; Lima, R. R.; Anjos, T. O. D.; Siqueira, G. M.; Nascimento, L. D. D.; Cascaes, M. M.; de Oliveira, M. S.; Andrade, E. H. A. Essential oil of the plants growing in the Brazilian Amazon: chemical composition, antioxidants, and biological applications. Molecules 2022, 27, 4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lara da Silva, C. E.; Oyama, J.; Ferreira, F. B. P.; de Paula Lalucci-Silva, M. P.; Lordani, T. V. A.; de Lara da Silva, R. C.; de Souza Terron Monich, M.; Teixeira, J. J. V.; Lonardoni, M. V. C. Effect of essential oils on Leishmania amazonensis: a systematic review. Parasitology 2020, 147, 1392–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A. B.; da Silva Bortoleti, B. T.; Tomiotto-Pellissier, F.; Ganaza, A. F. M.; Gonçalves, M. D.; Carloto, A. C. M.; Rodrigues, A. C. J.; Silva, T. F.; Nakazato, G.; Kobayashi, R. K. T.; Lazarin-Bidóia, D.; Miranda-Sapla, M. M.; Costa, I. N.; Pavanelli, W. R.; Conchon-Costa, I. Synergistic Antileishmanial Effect of Oregano Essential Oil and Silver Nanoparticles: Mechanisms of Action on Leishmania amazonensis. Pathogens 2023, 12, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, A. D.; Alghabban, A. J. Antileishmanial and synergic effects of Rhanterium epapposum essential oil and its main compounds alone and combined with glucantime against Leishmania major infection. International Journal for Parasitology: Drugs and Drug Resistance 2024, 26, 100571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzote, L.; Geroldinger, G.; Tonner, M.; Scull, R.; De Sarkar, S.; Bergmann, S.; Bacher, M.; Staniek, K.; Chatterjee, M.; Rosenau, T.; Gille, L. Interaction of ascaridole, carvacrol, and caryophyllene oxide from essential oil of Chenopodium ambrosioides L. with mitochondria in Leishmania and other eukaryotes. Phytotherapy Research 2018, 32, 1729–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essid, R. , Damergi, B., Fares, N., Jallouli, S., Limam, F., Tabbene, O. Synergistic combination of Cinnamomum verum and Syzygium aromaticum treatment for cutaneous leishmaniasis and investigation of their molecular mechanism of action. International Journal of Environmental Health Research 2024, 34, 2687–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, R. C. , Rosa, A. D. S., Mateus, M. H. D. S., Soares, D. C., Atella, G., Guimarães, A. C., Siani, A. C., Ramos, M. F. S., Saraiva, E. M., Pinto-da-Silva, L. H. In vitro leishmanicidal activity of monoterpenes present in two species of Protium (Burseraceae) on Leishmania amazonensis. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 2020, 259, 112981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S. L.; Marques, A. M.; Sudo, R. T.; Kaplan, M. A.; Zapata-Sudo, G. Vasodilator Activity of the Essential Oil from Aerial Parts of Pectis brevipedunculata and Its Main Constituent Citral in Rat Aorta. Molecules 2013, 18, 3072–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S. R.; Melo, M. A.; Cardoso, A. V.; Santos, R. L.; de Sousa, D. P.; Cavalcanti, S. C. Structure-Activity Relationships of Larvicidal Monoterpenes and Derivatives against Aedes aegypti Linn. Chemosphere 2011, 84, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limane, B. B.; Ezzine, O.; Dhahri, S.; Ben Jamaa, M. L. Essential Oils from Two Eucalyptus from Tunisia and Their Insecticidal Action on Orgyia trigotephras (Lepidoptera, Lymantriidae). Biol. Res. 2014, 47, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varzandeh, M.; Mohammadinejad, R.; Esmaeilzadeh-Salestani, K.; Dehshahri, A.; Zarrabi, A.; Aghaei-Afshar, A. Photodynamic therapy for leishmaniasis: Recent advances and future trends. Photodiagnosis and photodynamic therapy 2021, 36, 102609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dourado, D.; Silva Medeiros, T.; do Nascimento Alencar, É.; Matos Sales, E.; Formiga, F. R. Curcumin-loaded nanostructured systems for treatment of leishmaniasis: a review. Beilstein journal of nanotechnology 2024, 15, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albalawi, A. E.; Alanazi, A. D.; Sharifi, I.; Ezzatkhah, F. A Systematic Review of Curcumin and its Derivatives as Valuable Sources of Antileishmanial Agents. Acta parasitologica 2021, 66, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, M.; Sauvain, M.; Deharo, E. Curcuma as a parasiticidal agent: a review. Planta medica 2011, 77, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Nadhman, A.; Sehgal, S. A.; Siraj, S.; Yasinzai, M. M. Formulation and Characterization of a Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery System (SEDDS) of Curcumin for the Topical Application in Cutaneous and Mucocutaneous Leishmaniasis. Current topics in medicinal chemistry 2018, 18, 1603–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Pharmacopeia and National Formulary (USP 41-NF 36); United States Pharmacopeial Convention: 2016.

- Alexander, S.; Cosgrove, T.; Prescott, S. W.; Castle, T. C. Flurbiprofen Encapsulation Using Pluronic Triblock Copolymers. Langmuir 2011, 27, 8054–8060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haillant, O.; Dumbleton, D.; Zielnik, A. An Arrhenius Approach to Estimating Organic Photovoltaic Module Weathering Acceleration Factors. Solar Energy Materials & Solar Cells 2011, 95, 1889–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P. C.; Stilbs, P.; Yu, G. E.; Booth, C. Role of Molecular Architecture in Polymer Diffusion: A PGSE-NMR Study of Linear and Cyclic Poly(ethylene Oxide). Journal of Physical Chemistry 1995, 99, 16752–16756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, M.; Bhattacharya, S. C.; Moulik, S. P.; Panda, A. K. Interfacial Composition, Structural and Thermodynamic Parameters of Water/(Surfactant+n-Butanol)/n-Heptane Water-in-Oil Microemulsion Formation in Relation to the Surfactant Chain Length. Journal of Surfactants and Detergents 2010, 13, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, D.; Ramsey, J. D.; Kabanov, A. V. Polymeric micelles for the delivery of poorly soluble drugs: From nanoformulation to clinical approval. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2020, 156, 80–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, M.; Panda, A. K. Spectral Behaviour of Eosin Y in Different Solvents and Aqueous Surfactant Media. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2011, 81, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandridis, P.; Hatton, T. A. Poly(ethylene Oxide)-poly(propylene Oxide)-poly(ethylene Oxide) Block Copolymer Surfactants in Aqueous Solutions and at Interfaces: Thermodynamics, Structure, Dynamics, and Modeling. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 1995, 96, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanka, G.; Hoffmann, H.; Ulbricht, W. Phase Diagrams and Aggregation Behavior of Poly(oxyethylene)-Poly(oxypropylene)-Poly(oxyethylene) Triblock Copolymers in Aqueous Solutions. Macromolecules 1994, 27, 4145–4159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, S.; Cosgrove, T.; Castle, T. C.; Grillo, I.; Prescott, S. W. Effect of Temperature, Cosolvent, and Added Drug on Pluronic–Flurbiprofen Micellization. Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2012, 116, 11545–11551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, W.; Schillin, K. Triblock Copolymers in Aqueous Solution Studied by Static and Dynamic Light Scattering and Oscillatory Shear Measurements: Influence of Relative Block Sizes. American Chemical Society 1992, 6044, 6038–6044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P. K.; Bhatia, S. R. Effect of Anti-Inflammatories on Pluronic® F127: Micellar Assembly, Gelation and Partitioning. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2004, 278, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, M.; Håkansson, B.; Söderman, O.; Topgaard, D. Influence of Polydispersity on the Micellization of Triblock Copolymers Investigated by Pulsed Field Gradient Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 8250–8258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landazuri, G.; Fernandez, V. V. A.; Soltero, J. F. A.; Rharbi, Y. Kinetics of the Sphere-to-Rod like Micelle Transition in a Pluronic Triblock Copolymer. Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2012, 116, 11720–11727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, W.; Stilbs, P. On the Solution Conformation of Poly(ethylene Oxide): An FT-Pulsed Field Gradient NMR Self-Diffusion Study. Polymer 1982, 23, 1780–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espenson, J. H. Chemical Kinetics and Reaction Mechanisms. Second Edition. McGraw-Hill Series in Advanced Chemistry, 1995.

| Components % (w/w) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | Water | F127 | 974p | EOPb | CUR | Stability |

| nGPC1 | 78.99 | 20 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.01 | S |

| nGPC2 | 78.78 | 20 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.02 | S |

| nGPC3 | 78.47 | 20 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.03 | S |

| nGPC4 | 78.36 | 20 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.04 | S |

| nGPC5 | 78.25 | 20 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.05 | PS |

| nG | nGPC | |

|---|---|---|

| Temperatura (°C) | Dh (nm) / PDI | |

| 25 | 661.00 ± 6.00 / 0.34 | 288.00 ± 74.00 / 0.29 |

| 32 | 124.00 ± 5.00 / 0.24 | 296.00 ± 24.00 / 0.44 |

| 37 | 17.00 ± 3.00 / 0.25 | 237.00 ± 17.00 / 0.42 |

| 45 | 16,93 ± 3.00 / 0.26 | 333.50 ± 22.00 / 0.45 |

| nG | nGPC | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

| (kJ mol−1) | 208.53 | (kJ mol−1) | -10.76 |

| (kJ K−1 mol−1) | 0.31 | (kJ K−1 mol−1) | -0.29 |

| (kJ mol−1) | 168.20 | (kJ mol−1) | -13.30 |

| (kJ mol−1) at different temperatures | |||

| Temperature (K) | nG | Temperature (K) | nGPC |

| 298.15 | 75.80 | 298.15 | 73.20 |

| 303.15 | 73.60 | 303.15 | 75.20 |

| 305.15 | 72.10 | 305.15 | 76.60 |

| 310.15 | 69.60 | 310.15 | 79.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).