1. Introduction

Natural products remain a major foundation for drug discovery and chemical innovation due to their structural diversity and broad pharmacological potential. Among these, phenolic compounds have received considerable attention for their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cytoprotective effects—properties largely attributed to their redox activity and capacity to modulate oxidative stress. Given the central involvement of oxidative stress in chronic disorders such as diabetes, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases, the characterization of plant-derived phenolics continues to be a priority in phytochemical and pharmaceutical research. [

1,

2]

Solenostemma argel (

argel) is a medicinal plant traditionally used across North and East Africa and parts of the Arabian Peninsula. Its secondary metabolome includes phenolic acids, flavonoids, pregnane glycosides, monoterpenes, and volatile constituents. Despite this chemical richness [

3], existing research on S. argel remains geographically limited, methodologically variable, and relatively scarce—particularly regarding phenolic-specific investigations. This gap underscores the need for a broadened and integrative analytical review.

The present expanded review synthesizes evidence from studies that directly or indirectly inform the phenolic composition, extraction efficiency, analytical characterization, and antioxidant-linked bioactivity of S. argel. Research was included when phenolics were explicitly targeted, co-extracted due to solvent polarity, or implicated through antioxidant-associated biological assays. In addition, analytical techniques applied to other metabolite classes were evaluated for their relevance to future phenolic profiling. Through this inclusive approach, the review aims to consolidate fragmented knowledge, clarify methodological trends, and support the advancement of phytochemical and pharmacological research on S. Argel.

To the best of our knowledge, this review provides the first systematic synthesis and gap-analysis focusing specifically on the phenolic profiling and antioxidant-linked bioactivity of Solenostemma argel. While previous studies remain limited in number and scope and primarily report isolated experimental findings, the present work critically consolidates these datasets, compares analytical and extraction methodologies, and identifies concrete methodological and knowledge gaps that can guide future targeted analytical and biological studies.

2. Methodology

Given the limited number of studies directly analyzing phenolic compounds in Solenostemma argel, this review adopted an expanded methodological framework to integrate chemically, analytically, and biologically relevant research. The approach consisted of three components: study identification, inclusion criteria, and comparative analytical strategy.

2.1. Study Identification

A structured literature search was conducted using Google Scholar, PubMed, ResearchGate, ScienceDirect, and regional phytochemistry journals. The search covered publications from 2000 to 2024 and used the keywords Solenostemma argel, phenolic compounds, flavonoids, antioxidant activity, extraction methods, chromatographic techniques, and phytochemical analysis. Additional sources were identified through citation tracking of the initially retrieved articles.

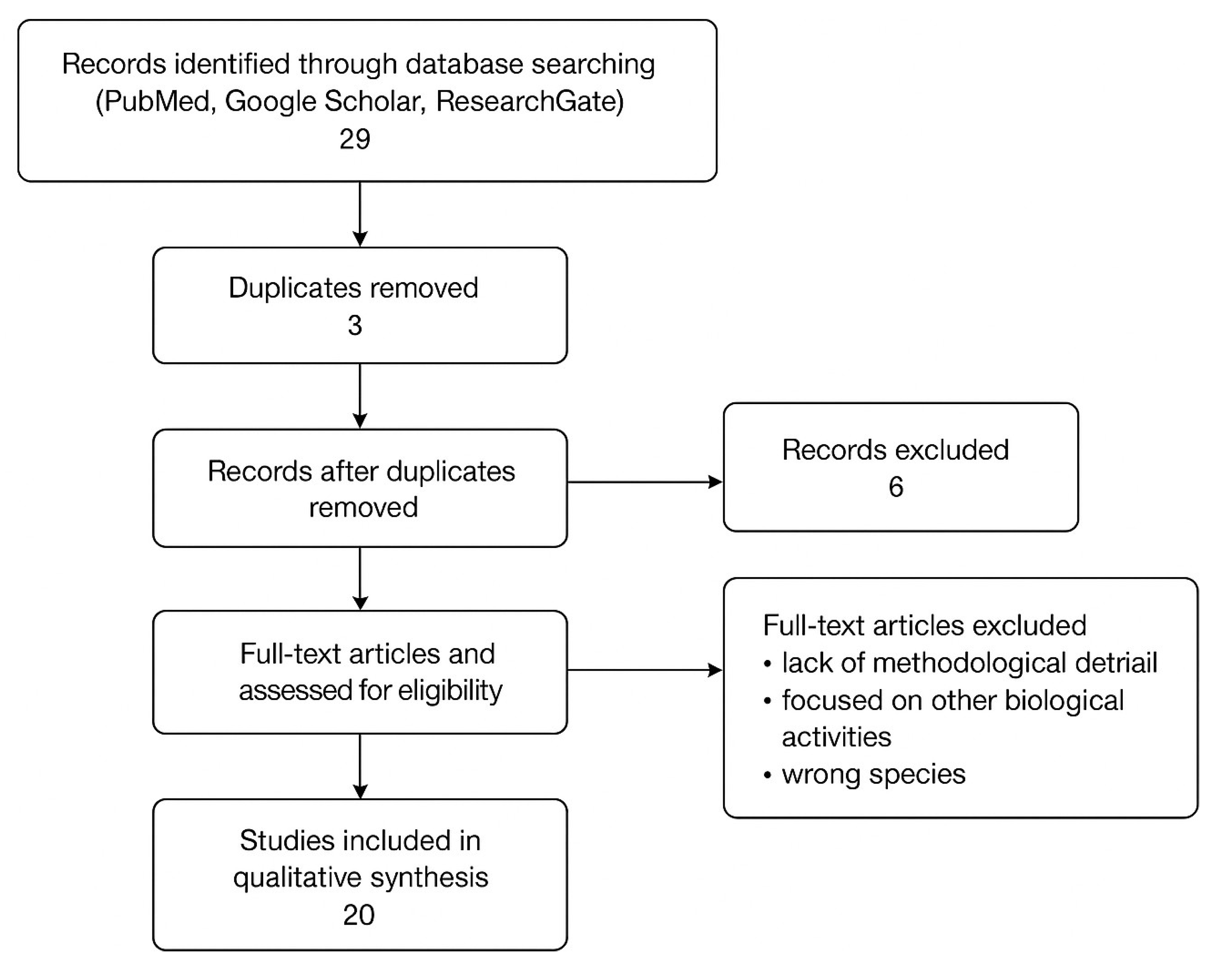

The overall identification, screening, and eligibility workflow followed PRISMA guidelines and is illustrated in

Figure 1.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Because phenolic-specific studies on S. argel are scarce, broadened inclusion criteria were applied. Studies were included if they met at least one of the following:

Direct phenolic analysis: identification, quantification, or characterization of phenolic acids, flavonoids, or related phenolic constituents.

Relevant extraction methodologies: use of moderately polar solvents (e.g., ethanol, methanol, acetone) capable of extracting phenolic compounds, even when phenolics were not the primary analytes.

Antioxidant-related biological studies: evaluation of antidiabetic, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, or neuroprotective effects associated with oxidative stress, given their relevance to phenolic bioactivity.

Analytical technique studies: application of chromatographic or spectroscopic platforms (HPLC, GC-MS, NMR) to S. argel extracts for any metabolite class, provided the techniques are suitable for phenolic profiling.

Studies were excluded if they (i) lacked methodological clarity; (ii) relied exclusively on non-polar solvents unsuitable for phenolic extraction; or (iii) assessed biological activity unrelated to oxidative stress without accompanying chemical analysis.

2.3. Comparative Analytical Strategy

To enable meaningful comparison, data from the included studies were extracted and organized according to the following dimensions:

Extraction efficiency: technique type (maceration, Soxhlet, UAE, MAE), solvent polarity, temperature, and reported yields.

Total phenolic content (TPC): methodological factors contributing to inter-study variability.

Analytical platforms: chromatographic and spectroscopic techniques used for metabolite separation, detection, and structural characterization, with emphasis on their applicability to phenolic analysis.

Antioxidant and antioxidant-related bioactivity: comparison across assay types (DPPH, FRAP, ORAC), extract polarity, plant part, and reported activity levels.

This expanded methodological framework enabled the integration of chemically focused studies with biological and analytical research, providing a holistic evaluation of S. argel phenolics and their pharmacological relevance.

3. Phenolic Profile of Solenostemma argel

3.1. Overview of Identified Phenolic Compounds

Over the past two decades, phytochemical investigations have demonstrated that

Solenostemma argel possesses a chemically diverse phenolic profile comprising phenolic acids, flavonoids, and phenolic glycosides. These metabolites are central to the plant’s antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cytoprotective properties. [

3]

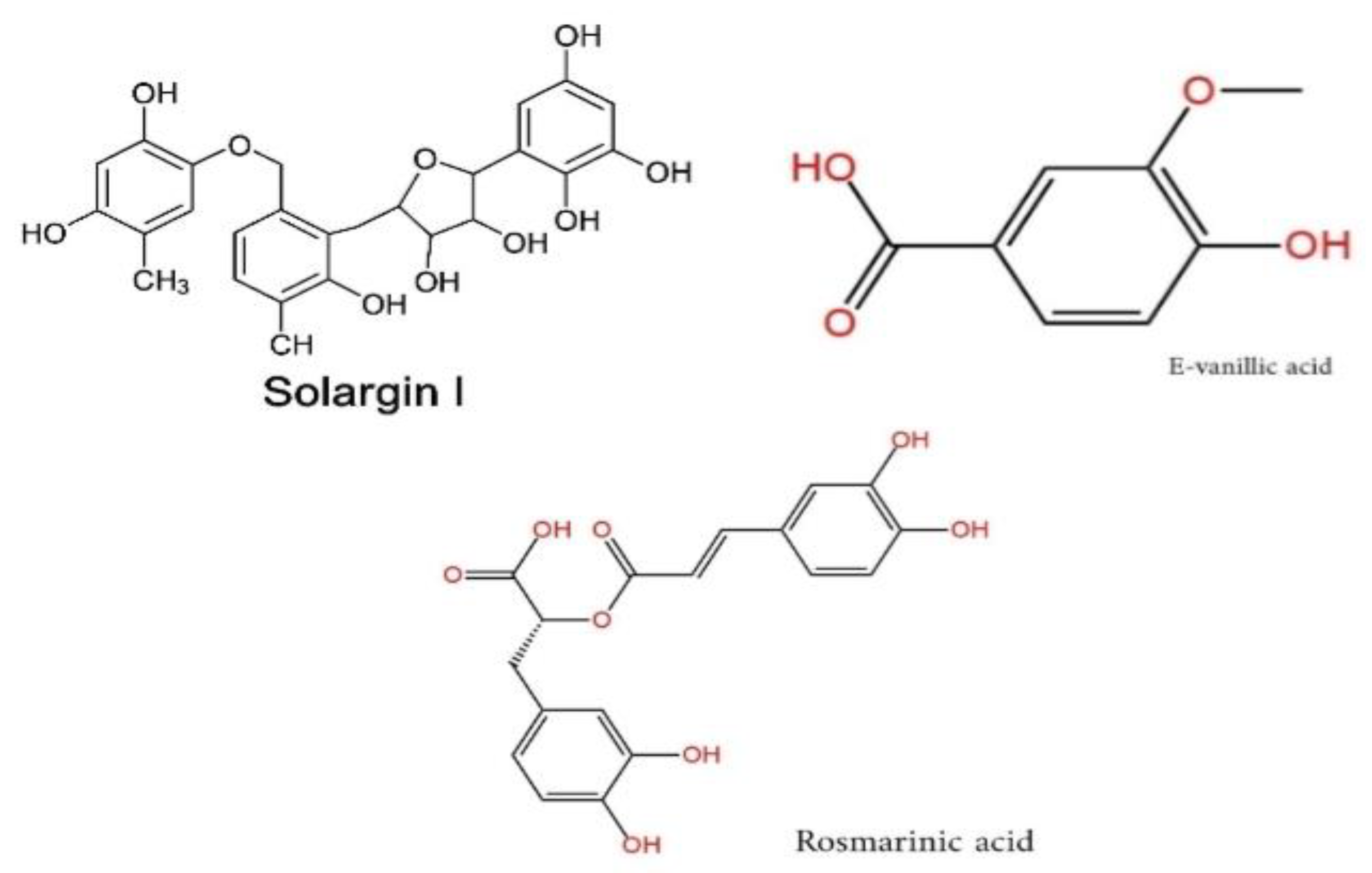

Chromatographic analyses—particularly HPLC and UPLC–MS—consistently highlight phenolic acids as one of the dominant classes. E-vanillic acid, pyrocatechol, pyrogallol, ferulic acid, and chlorogenic acid are frequently reported at relatively high levels. Owing to their ability to donate hydrogen atoms or electrons, these compounds play key roles in neutralizing reactive oxygen species, thereby contributing to the plant’s antioxidant potential.Flavonoids identified in S. argel include naringenin, quercetin, hesperidin, kaempferol, and their glycosides such as kaempferol-3-O-glucoside (astragalin) and quercetin-3-O-rhamnosyl-(1→2)-glucoside. Their multiple hydroxyl groups and conjugated π-systems provide strong radical-scavenging capacities and metal-chelating properties, supporting their well-documented biological. [

3,

4]

Notably, several novel phenolic glycosides—Solargins I–IV—have been isolated from the aerial parts of the plant. NMR and HR-ESI-MS analyses confirmed their structures as acylated phenolic glycosides with unique substitution patterns not previously reported in related taxa [

5]. The discovery of these compounds underscores the distinct chemical signature of S. argel within the Asclepiadaceae family and highlights its potential as a source of structurally unique antioxidant agents.

Table 1.

Major Phenolic Classes and Key Identified Compounds in Solenostemma argel.

Table 1.

Major Phenolic Classes and Key Identified Compounds in Solenostemma argel.

| Phenolic class |

Representative compounds |

Notes |

References |

| Phenolic acids |

Vanillic acid, E-vanillic acid, Ferulic acid, Chlorogenic acid, Gallic acid, Pyrogallol, Caffeic acid |

Highest concentration reported for E-vanillic acid; abundant across leaves and aerial parts |

[3,6] |

| Flavonoids |

Quercetin, Hesperidin, Narengin, Rutin, Kaempferol, Kaempferol glycosides

(3-O-glucoside, 3-O-arabinoside, 7-O-rhamnoside), Apigenin |

Major contributors to antioxidant activity; present in both free and glycosylated forms |

[3,6] |

| Phenolic glycosides |

Solargins I-IV |

Newly identified; structurally unique glycosides |

[3,5,7] |

| Other related metabolites |

Rosmarinic acid, Coumarins, Cinnamic derivatives |

Occur at moderate levels; contribute to total antioxidant capacity |

[8] |

The chemical structures of the key phenolic compounds identified in S. Argel—Solargin I, E-vanillic acid, and rosmarinic acid—are shown in

Figure 2 to support the phytochemical discussion.

In summary, S. argel contains a broad spectrum of phenolic metabolites ranging from low-molecular-weight acids to highly glycosylated flavonoids. This diversity likely contributes to the plant’s multifaceted antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cytoprotective effects.

3.4. Distribution Across Plant Parts

The qualitative and quantitative distribution of phenolic compounds in Solenostemma argel varies notably among leaves, aerial parts, roots, and fruit peels, reflecting organ-specific physiological roles and metabolic specialization.

Leaves

Leaves consistently show the highest phenolic concentrations, enriched particularly in E-vanillic acid, pyrogallol, ellagic acid, hesperidin, and quercetin derivatives [

8]. Reported total phenolic contents (TPC) typically range between 60–80 mg GAE/g DW, depending on solvent polarity and extraction technique. The abundance of polyhydroxylated phenolics is consistent with the protective function of leaves against ultraviolet radiation and oxidative stress, explaining the strong antioxidant activity observed in ethanolic and methanolic extracts.

Aerial Parts.

Extracts derived from combined aerial tissues (leaves, stems, and flowers) generally show slightly lower phenolic concentrations but greater structural diversity. These extracts commonly contain phenolic acids, flavonoids, glycosides, and the distinctive Solargins I–IV [

3,

5]. The mixed tissue composition facilitates the co-accumulation of both glycosylated metabolites and aglycones, making aerial parts particularly useful for comprehensive profiling.

Roots and Fruit Peels.

Although less frequently studied, both organs exhibit noteworthy phenolic content. Microwave-assisted extraction of root material yielded up to 15.6% dry extract enriched in ethanol-soluble phenolic acids [

8]. Fruit peels demonstrated the highest extraction yield (53.5%) using ethanol/water (25:75), indicating substantial levels of phenolic or phenolic-like constituents likely associated with cuticular defense mechanisms.

Comparative Interpretation.

Overall patterns indicate the following gradient of phenolic abundance:

Leaves > Aerial parts > Fruit peels > Roots

Each organ contributes a distinct metabolic fingerprint: leaves predominantly accumulate phenolic acids, aerial parts are rich in glycosides and flavonoids, and roots contain simpler phenolics. These distributional differences highlight compartmentalized biosynthesis and adaptive metabolic responses typical of stress-modulated secondary metabolism.

Understanding these organ-specific patterns is essential for optimizing extraction strategies and selecting suitable plant parts for pharmacological, nutraceutical, or industrial applications.

Integrated Analysis of Phenolic Extraction, Characterization, and Antioxidant-Linked Bioactivity

4. Integrated Comparative Analysis

4.1. Extraction Methods

Studies investigating

Solenostemma argel consistently demonstrate that extraction efficiency is strongly influenced by both solvent polarity and extraction technique. Moderately polar solvents—particularly ethanol, methanol, and acetone—are the most effective for solubilizing phenolic compounds due to their compatibility with the hydrogen-bonding capacity and partial polarity of phenolic structures [

9,

10].

Among extraction techniques, ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) and microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) repeatedly outperform conventional maceration and Soxhlet extraction. UAE and MAE achieve higher yields in significantly shorter times and better preserve thermolabile constituents, making them ideal for phenolic-rich extracts [

9]. Conversely, maceration yields moderate extraction efficiency and requires prolonged durations [

10,

11], while Soxhlet extraction introduces risk of thermal degradation despite providing relatively [

12].

Regarding fractionation and separation, most studies followed sequential solvent extraction protocols with increasing polarity (petroleum ether, chloroform, ethyl acetate, n-butanol) [

6,

7,

13,

14], followed by chromatographic techniques (silica gel column, Sephadex LH-20, RP-18, HPLC) to isolate specific compounds such as argel glycosides, flavonoid derivatives, and phenolic glycosides.

Variability among reported extraction outcomes can be attributed to several methodological factors, including solvent composition, temperature, extraction time, plant part used, and particle size. These parameters collectively influence diffusion rates and solvent penetration, ultimately affecting phenolic recovery.

Table 2.

Summary of Extraction Methods and Their Estimated Yields in Solenostemma argel.

Table 2.

Summary of Extraction Methods and Their Estimated Yields in Solenostemma argel.

| Extraction Technique |

Solvent System |

Typical Yield (%) |

General Evaluation |

References |

| Maceration (RT, days) |

Methanol 80%, Ethanol 80% |

10–14% |

Simple; long time; moderate yield |

[6,15] |

| Soxhlet (60°C) |

Methanol 95% |

~12% |

Higher yield; risk of thermal degradation |

[11] |

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) |

Ethanol 25–50% |

— |

Best antioxidant potency; good extraction selectivity |

[9] |

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) |

EtOH/H₂O (various ratios) |

15–53% |

Highest yields; short time; preserves thermolabile compounds |

[9] |

| Hot Water Extraction |

Water |

Low |

Mimics traditional use; weak extraction of phenolics |

[10] |

4.2. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

Reported total phenolic content in S. argel extracts varies substantially across studies, reflecting broad methodological differences. The highest TPC values have been recorded using acetone 80%, followed by ethanol-based extracts, while aqueous extractions consistently show the lowest TPC [

10], highlighting the limited ability of water to solubilize mid-polarity phenolics.

Differences in TPC measurements arise from variations in solvent polarity, extraction technique (UAE/MAE vs. maceration), plant part analyzed, and assay conditions, particularly those related to the Folin–Ciocalteu method. Despite this variability, a consistent pattern emerges: extracts with higher TPC exhibit stronger antioxidant activity [

8], underscoring the central role of phenolics in driving the plant’s bioactivity. Consolidated TPC data from the literature are summarized in

Table 3.

4.3. Antioxidant Activity

The antioxidant potential of S. argel has been evaluated through multiple in vitro assays, primarily DPPH, FRAP, and ORAC [

9,

10,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Across studies, extracts obtained using UAE and MAE consistently exhibit the strongest antioxidant performance [

9], aligning with their higher phenolic recovery. Extracts prepared with acetone or ethanol also demonstrate superior radical-scavenging activity relative to aqueous extracts [

9,

10], reflecting the higher solubility of phenolic compounds in mid-polar solvents.

A clear positive correlation is observed between TPC and antioxidant activity, particularly in assays measuring electron-transfer (FRAP) and radical-scavenging (DPPH) capacities [

10]. Leaf extracts generally demonstrate the highest antioxidant potency, followed by aerial parts, fruit peels, and roots—mirroring the gradient of phenolic abundance. [

15,

18]

Table 3.

Integrated Summary of Extraction Method, TPC, and Antioxidant Activity.

Table 3.

Integrated Summary of Extraction Method, TPC, and Antioxidant Activity.

| Extraction Method / Solvent |

TPC (mg GAE/g) |

Antioxidant Results (DPPH / FRAP / ORAC) |

Interpretation |

References |

| MAE – EtOH/H₂O |

15–53% (yield) |

High ORAC; strong radical scavenging |

Best overall extraction efficiency |

[9] |

| UAE – EtOH 25–50% |

63–72 |

Up to 91% DPPH inhibition |

Optimal balance of solvent + sonication |

[9] |

| Acetone 80% |

81.45 |

IC₅₀ = 48.87 µg/mL (DPPH); highest FRAP |

Most effective solvent for phenolics |

[10] |

| Ethanol 80% |

62.58 |

Moderate DPPH & FRAP |

Good extraction but lower bioactivity |

[10] |

| Methanol extract |

24.53 |

13.7–44.8% (DPPH) |

Lower phenolic levels → weaker activity |

[19] |

| Ethyl acetate extract |

— |

19–58% inhibition (DPPH) |

Extracts moderately polar antioxidant compounds |

[16] |

| Hot Water |

46.72 |

Lowest activity |

Poor extraction of phenolics |

[10] |

| Crude extracts (general) |

— |

Up to 86,263 µmol TE/100g (ORAC) |

Rich in mixed flavonoids |

[18] |

4.4. Analytical Techniques

A range of chromatographic and spectroscopic platforms has been employed to characterize the phenolic constituents of S. Argel. HPLC is the most widely used technique, providing reliable qualitative and quantitative separation of phenolic acids and flavonoids. UPLC–MS offer deeper structural insights, particularly for glycosylated flavonoids and newly reported phenolic glycosides such as Solargins I–IV [

3,

5,

6,

20,

21,

22]. These mass-spectrometric approaches enable precise detection of minor constituents and are essential for establishing comprehensive phenolic fingerprints.

NMR spectroscopy remains the definitive tool for structural confirmation of novel metabolites, playing a central role in elucidating the substitution patterns of the Solargin series [

9,

22]. Although GC–MS is primarily applied to volatile metabolites, studies employing GC–MS on S. Argel were considered in this review when they provided methodological relevance or insights into the analytical suitability of the technique for future phenolic work [

3,

9,

22].

Table 4.

Comparative Overview of Analytical Techniques Applied to Solenostemma argel and Their Suitability for Phenolic Analysis.

Table 4.

Comparative Overview of Analytical Techniques Applied to Solenostemma argel and Their Suitability for Phenolic Analysis.

| Technique |

Purpose in S. argel Studies |

Strengths |

Limitations |

Relevance to Phenolic Analysis

|

References |

| HPLC |

Quantification of phenolic acids and flavonoids; profiling of major compounds |

High-resolution separation; reproducible quantification; widely validated for phenolics |

Limited ability to identify unknowns without MS coupling |

Strongly suitable for routine phenolic profiling and quantification |

[3,5,6,20,21,22] |

| UPLC–MS |

Identification of phenolic acids, flavonoids, and novel glycosides (e.g., Solargins I–IV) |

High sensitivity; structural elucidation; detection of minor and complex metabolites |

Requires advanced instrumentation and expertise |

Essential for comprehensive phenolic profiling and discovering new phenolics |

[3,5,6,20,21,22] |

| GC–MS |

Mainly used for volatile oils and non-phenolic constituents |

Excellent for volatile and semi-volatile compounds; rich spectral libraries |

Phenolics generally non-volatile; requires derivatization |

Indirect relevance—useful for evaluating analytical feasibility and method transferability |

[3,9,22] |

| NMR |

Structural confirmation of newly identified compounds (e.g., Solargins) |

Definitive structural clarification; essential for new compound validation |

Low sensitivity; requires high-purity isolates; time-consuming |

Crucial for full structural characterization of isolated phenolic glycosides |

[5,6] |

| UV–Vis Spectrophotometry |

Used for general phenolic assays (TPC) |

Simple; rapid; cost-effective |

Non-specific; subject to interference |

Useful for total phenolic estimation but not compound-level analysis |

[7,9,10,19] |

5. Discussion

The collective findings synthesized in this review demonstrate that the phenolic composition, extraction efficiency, and antioxidant performance of Solenostemma argel are governed by a combination of chemical, methodological, and biological factors. The superiority of moderately polar solvents and modern extraction technologies reflects fundamental principles of phenolic chemistry: mid-polarity phenolics exhibit optimal solubility in hydroalcoholic and acetone-based systems, and their recovery is enhanced under conditions that increase mass transfer without exposing compounds to excessive thermal degradation. Techniques such as UAE and MAE achieve this balance efficiently, explaining their consistent advantage over maceration and Soxhlet extraction.

Variability in reported total phenolic content (TPC) across studies can be attributed to differences not only in solvent polarity but also in protocol parameters—extraction time, temperature, particle size, and plant part used. These methodological disparities underscore the need for harmonized extraction protocols, particularly when comparing TPC values across independent research groups. The strong alignment between phenolic-rich extracts and antioxidant potency across multiple assay types further highlights the central contribution of phenolic compounds to the biological activity of S. argel. This relationship is consistent with established antioxidant mechanisms, where phenolic acids and flavonoids act as electron or hydrogen donors, stabilize reactive oxygen species, and participate in metal chelation.

Organ-specific differences in phenolic distribution also hold biological significance. The predominance of highly hydroxylated phenolic acids and flavonoids in leaves is congruent with their protective roles against oxidative stress, mirroring patterns observed in other members of the Asclepiadaceae family. In contrast, aerial parts provide broader chemical diversity due to the coexistence of glycosides and aglycones, while fruit peels and roots contain simpler phenolics associated with defense or structural functions. These distributional patterns suggest compartmentalized biosynthesis and adaptive allocation of phenolic metabolites, offering useful guidance for selecting specific organs for targeted phytochemical or pharmacological applications.

The analytical methodologies used across studies further shape the current understanding of S. argel phytochemistry. HPLC remains adequate for profiling major phenolics, but the limited use of advanced NMR platforms constrains the structural resolution of minor or novel metabolites. The recent identification of Solargins I–IV illustrates the capacity of modern spectroscopic tools to reveal previously unrecognized constituents, suggesting that the phenolic profile of the plant is likely richer than currently documented. The underutilization of these techniques represents a key limitation in existing research and highlights an important direction for future analytical work.

Collectively, these insights reveal both the biochemical potential and the methodological challenges associated with phenolic research on S. argel. While the available evidence establishes the plant as a promising source of bioactive phenolics, the current literature remains fragmented, heterogeneous in methodology, and limited in analytical depth. Addressing these gaps will be essential for fully characterizing the pharmacological relevance of this underexplored species.

6. Limitations

The current body of literature on Solenostemma argel presents several methodological and analytical limitations that influence the depth and consistency of available findings. First, phenolic-specific studies remain limited in number, necessitating the inclusion of research where phenolics were co-extracted or indirectly implicated through antioxidant-related biological assays. Second, substantial methodological variability exists across studies, particularly in solvent composition, extraction duration, temperature, and plant parts used, making direct quantitative comparison challenging.

Analytical characterization is also constrained by the limited use of advanced platforms such as UPLC–MS, and NMR. While these techniques have enabled the identification of structurally unique compounds such as Solargins I–IV, their underutilization restricts the ability to establish a comprehensive phenolic fingerprint for the species. In addition, inconsistencies in total phenolic content (TPC) protocols—especially variations in Folin–Ciocalteu calibration standards and reporting units—further contribute to inter-study discrepancies.

Finally, few studies directly link identified phenolic constituents to specific antioxidant or pharmacological mechanisms, with most biological evaluations relying on crude extracts. These gaps collectively indicate that the phenolic profile of S. Argel is likely more complex than currently documented and highlight the need for more standardized and analytically rigorous investigations.

7. Conclusions

The collective evidence reviewed in this study demonstrates that Solenostemma argel possesses a structurally diverse and biologically significant phenolic profile. Moderately polar extraction systems and modern techniques such as UAE and MAE consistently yield phenolic-rich extracts, reflecting the chemical characteristics of dominant phenolic acids and flavonoids within the plant. Across studies, higher total phenolic content aligns with stronger antioxidant performance, underscoring the central role of phenolics in mediating the plant’s cytoprotective potential.

Although current analytical data remain fragmented and uneven in methodological rigor, recent findings—particularly the identification of structurally unique phenolic glycosides—highlight S. argel as an underexplored yet promising source of bioactive metabolites. Taken together, the available literature positions this species as a valuable candidate for further phytochemical and pharmacological investigation, particularly in the context of natural antioxidant development.

Recommendations

Based on the integrated analysis of existing literature, several priority areas can guide future research on the phenolic composition and antioxidant potential of Solenostemma argel:

1. Standardizing extraction parameters—particularly solvent composition, temperature, and duration—to improve comparability of phenolic yield data.

2. Applying advanced analytical platforms (UPLC–MS, LC–MS/MS, NMR) to establish comprehensive phenolic fingerprints and identify minor or structurally novel metabolites.

3. Harmonizing TPC determination protocols and reporting formats to reduce inter-study variability.

4. Employing multiple complementary antioxidant assays rather than single-test evaluations to obtain more reliable assessments of redox-related activity.

5. Conducting mechanistic in vivo studies to clarify molecular pathways underlying antioxidant, antidiabetic, neuroprotective, and anticancer effects.

6. Establishing clearer links between specific phenolic structures and biological outcomes, including the potential contribution of synergistic interactions among metabolite classes.

7. Developing quality-controlled, standardized phenolic-rich extracts suitable for nutraceutical or phytopharmaceutical applications.

8. Integrating metabolomics and chemoinformatics approaches to support deeper structural characterization and comprehensive profiling.

Author Contributions

Ehsan M. G. Abdullah: Conceptualization, Methodology, Literature Search, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Drafting the original manuscript, Review & Editing. Eilaf A. M. Suleman and Yasmeen Y. A. Hamid: Assistance with literature acquisition and minor review of the initial draft. Rehab A. Ibrahim: Supervision, Project Administration, and critical review of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The AI tool ChatGPT-4 was used exclusively for the purpose of improving linguistic quality, checking grammar, and adjusting the phrasing style in this research. We confirm that the process of quantitative data collection and analysis, as well as the scientific conclusions, is the original and human effort of the authors, who bear full responsibility for the accuracy and reliability of all information presented in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Phenolic compounds identified in Solenostemma argel.

Table A1.

Phenolic compounds identified in Solenostemma argel.

| Category |

Compound |

Amount (µg/g) |

Plant Part |

Reference |

| Phenolic acids |

Pyrocatechol |

9519.95 |

Aerial parts |

[3] |

| |

Ferulic acid |

3221.41 |

Aerial parts |

[3] |

| |

Chlorogenic acid |

3221.41 |

Aerial parts |

[3] |

| |

Gallic acid |

2730.85 |

Aerial parts |

[3] |

| |

Pyrogallol |

4666.3 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

4-Amino benzoic acid |

206.2 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

Catechol |

1292.2 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

Epicatechin |

749.8 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

Caffeine |

372.5 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

p-Hydroxy benzoic acid |

1940.7 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

Caffeic acid |

623.8 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

Vanillic acid |

938.8 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

Iso-ferulic acid |

364 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

E-vanillic acid |

26289.4 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

Resveratrol |

115.2 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

Ellagic acid |

3451.8 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

A- Coumaric acid |

638.4 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

Benzoic acid |

2153.7 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

3,4,5-Methoxy cinnamic acid |

1458 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

Coumarin |

386.4 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

p-Coumaric acid |

189.4 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

Cinnamic acid |

477.7 |

Leave |

[8] |

| Flavonoids |

Naringenin |

2262.8 |

Aerial parts |

[3] |

| |

Quercetin |

1750.25 |

Aerial part |

[3] |

| |

Rutin |

947.1 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

Hesperidin |

3863.3 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

Narengin |

1462.1 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

Rosmarinic acid |

1213.3 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

Quercetrin |

216.8 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

Hesperetin |

998.8 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

Apigenin |

783 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

Kaempferol |

372.5 |

Leaves |

[8] |

| |

Kaempferol-3-O-glucoside (Astragalin) |

6% of extract |

Leaves & flowers |

[7] |

| |

Kaempferol-3-O-arabinoside |

– |

Leaves |

[3] |

| |

Kaempferol-3-O-xyloside |

– |

Leaves |

[3] |

| |

Kaempferol-7-O-rhamnoside |

– |

Leaves |

[3] |

| |

Kaempferol-7-O-arabinoside |

_ |

Leaves |

[3] |

| |

Kaempferol-3,7-di-O-β-D-glucoside |

_ |

Leaves |

[3] |

| |

Quercetin-3-O-rhamnosyl-(1→2)-glucoside |

– |

Leaves |

[3] |

| |

Quercetin-3-O-glucoside |

_ |

Leaves |

[3] |

| |

Isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside |

_ |

Leaves |

[3] |

| Phenolic glycosides |

Solargins I–IV |

_ |

Aerial parts |

[3,5] |

References

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. Journal of Natural Products 2020, 83, 770–803. [CrossRef]

- Ogbodo, J.O.; Agbo, C.P.; Echezona, A.C.; Ezike, T.C.; Emencheta, S.C.; Onyia, O.C.; Iguh, T.C.; Ihim, S.A. Therapeutic role of phenolic antioxidants in herbal medicine. In: Upaganlawar, A.B.; Dhote, V.V.; Raja, M.K.M., Eds. Health Benefits of Phenolic Antioxidants; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 149–166.

- Abdel-Sattar, E.; El-Shiekh, R.A. A comprehensive review on Solenostemma argel (Del.) Hayne: An Egyptian medicinal plant. Bulletin of the Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University 2024, 62, Article 3. [CrossRef]

- El-shiekh, R.A.; Al-Mahdy, D.A.; Mouneir, S.M.; Hifnawy, M.S.; Abdel-Sattar, E.A. Anti-obesity effect of argel (Solenostemma argel) on obese rats fed a high fat diet. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2019, 238, 111893. [CrossRef]

- Kamel, M.S. Acylated phenolic glycosides from Solenostemma argel. Phytochemistry 2003, 62, 1247–1250. [CrossRef]

- Demmak, R.G.; Bordage, S.; Bensegueni, A.; Boutaghane, N.; Hennebelle, T.; Mokrani, E.H.; Sahpaz, S. Chemical constituents from Solenostemma argel and their cholinesterase inhibitory activity. Natural Product Sciences 2019, 25, 115–121. [CrossRef]

- Hassabelrasoul, H.; Moriguchi, M.; Kang, B.; Siribel, A.A.; Kuse, M. Isolation and identification of metabolites from ethyl acetate leaf extract of Solenostemma argel. Agriculture and Natural Resources 2021, 55, 757–763. [CrossRef]

- Azer, D.D.; Kahlil, A.F.; Hafez, A.A.; El-Hadidy, E.M. Hepato effect of argel herb (Solenostemma argel) against carbon tetrachloride-induced liver damage in albino rats. International Journal of Family Studies, Food Science and Nutrition Health 2021, 4, 142–161.

- Ahmed, I.A.M.; et al. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity from argel (Solenostemma argel Hayne) leaves using response surface methodology (RSM). Journal of Food Science and Technology 2020, 57, 3071–3080. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, E.A.; Gaafar, A.A.; Salama, Z.A.; El Baz, F.K. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity of Solenostemma argel extract. International Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemical Research 2015, 7, 635–641.

- Abouzaid, O.A.R.; Mansour, S.Z.; Sabbah, F. Evaluation of the antitumor activity of Solenostemma argel in the treatment of lung carcinoma induced in rats. Benha Veterinary Medical Journal 2018, 35, 178–189.

- Hamadnalla, H.M.Y.; El-Jack, M.M. Phytochemical screening and antibacterial activity of Solenostemma argel: A medicinal plant. Acta Scientific Agriculture 2019, 3, 2–4.

- Farah, A.A.; Ahmed, E.H. Beneficial antibacterial, antifungal and anti-insecticidal effects of ethanolic extract of Solenostemma argel leaves. Mediterranean Journal of Biosciences 2016, 1, 184–191.

- Taha, L.E.; Bakhit, S.M.A.; Al-Sa’aidi, J.A.A.; Uro, A.B. The anti-hyperglycemic effect of Solenostemma argel compared with Glibenclamide. Al-Qadisiya Journal of Veterinary Medical Sciences 2014, 13, 113–117.

- Taj Al-Deen, A.; Al-Naqeb, G. Hypoglycemic effect and in vitro antioxidant activity of methanolic extract from argel (Solenostemma argel) plant. International Journal of Herbal Medicine 2014, 2, 128–131.

- Abdel-Motaal, F.F.; Maher, Z.M.; Ibrahim, S.F.; El-Mleeh, A.; Behery, M.; Metwally, A.A. Comparative studies on the antioxidant, antifungal, and wound healing activities of Solenostemma argel ethyl acetate and methanolic extracts. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 4121. [CrossRef]

- El-Zayat, M.M.; Eraqi, M.M.; Alfaiz, F.A.; Elshaer, M.M. Antibacterial and antioxidant potential of some Egyptian medicinal plants used in traditional medicine. Journal of King Saud University–Science 2021, 33, 101466. [CrossRef]

- Ounaissi, K.; Pertuit, D.; Mitaine-Offer, A.-C.; Miyamoto, T.; Tanaka, C.; Delemasure, S.; Dutartre, P.; Smati, D.; Lacaille-Dubois, M.-A. New pregnane and phenolic glycosides from Solenostemma argel. Fitoterapia 2016, 114, 98–104. [CrossRef]

- Maad, A.H.; Al-Gamli, A.H.; Shamarekh, K.Sh.; Refat, M.; Shayoub, M.E. Antiproliferative and apoptotic effects of Solenostemma argel leaf extracts on colon cancer cell line HCT-116. Biomedical & Pharmacology Journal 2024, 17, 1987–1996. [CrossRef]

- Abd Alhady, M.R.; Hegazi, G.A.; Abo El-Fadl, R.E.; Desoukey, S.Y. Biosynthetical capacity of kaempferol from in vitro produced argel (Solenostemma argel) callus. Research Journal of Applied Biotechnology 2016, Special Issue.

- El-Beltagi, H.S.; Abdel-Mobdy, Y.E.; Abdel-Rahim, E. Toxicological influences of cyfluthrin attenuated by Solenostemma argel extracts on carbohydrate metabolism of male albino rats. Fresenius Environmental Bulletin 2017, 26, 1673–1681.

- Soliman, M.S.M.; Abdella, A.; Khidr, Y.A.; Osman, H.G.O.; Aladadh, M.A.; Elsanhoty, R.M. Pharmacological activities and characterization of phenolic and flavonoid compounds in Solenostemma argel extract. Research Square 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).