1. Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated in the body can damage cells and tissues, leading to the inactivation of proteins, attacks on unsaturated fatty acids, and overall deterioration of bodily functions. These processes contribute to oxidation, aging, and the development of cardiovascular and neurological diseases [

1]. Consequently, there is a demand for the development of antioxidants that can either enhance the body’s antioxidant defense system or regulate ROS [

2]. However, synthetic antioxidants such as butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) and butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) have been found to have toxic and carcinogenic side effects, limiting their use. Therefore, there is a need for safer natural antioxidants with fewer side effects [

3]. Aromatic medicinal herbs, among various natural plants, have traditionally been used for disease prevention and treatment. In recent years, research on the antioxidant activities of aromatic medicinal herbs has been ongoing. For example,

Cynanchum auriculatum,

Cynanchum bungei, and

Cynanchum wilfordii, which are native to East Asia and belong to the Asclepiadaceae family, have been used as traditional aromatic medicinal herbs and functional dietary supplements for hundreds of years. Studies have demonstrated their excellent antioxidant activity, immune-boosting properties, and anticancer effects [

4].

Cynanchum thesioides (Freyn) K. Schum (hereinafter referred to as

Cynanchum thesioides), also a member of the Asclepiadaceae family, is a perennial herb that stands erect or climbs, reaching heights of 15 to 25 cm. It contains white latex, and its stems are slender and weak, often branching extensively [

5].

Cynanchum thesioides grows on hillsides, dunes, wastelands, and farmland, with its flowering period from June to September and fruiting period from August to October. It is distributed across northern China, Mongolia, and Siberia [

6]. In several regions of Inner Mongolia and Mongolia, the fruits of

Cynanchum thesioides are consumed as food. The whole plant is traditionally used in folk medicine to promote lactation, reduce fever, and alleviate inflammation and pain. It has been a key ingredient in remedies for abdominal pain and diarrhea for centuries [

7]. Additionally,

Cynanchum thesioides has applications as food, fodder, and industrial raw material, and it is valuable for maintaining water and soil in pastures, holding significant economic and ecological importance [

8]. Prior studies have analyzed the components of

Cynanchum thesioides, revealing important antioxidant and anti-inflammatory compounds such as triterpenoids, flavonols, steroids, phenolic acids, amyrin, and oleanolic acid [

9]. Notably, quercetin, a representative flavonol, is known for its antioxidant and anti-aging effects [

10]. Thesioide oside, a unique compound of

Cynanchum thesioides, has been reported to possess various pharmacological effects, including cell protection and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases [

11].

Although there is substantial fundamental research on the bioactive effects of Cynanchum thesioides, studies evaluating and comparing the antioxidant activities of its solvent fractions are limited. Therefore, this study aims to assess the yield and antioxidant activities of the methanol extract and its sequential n-hexane, dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, n-butanol, and water fractions of Cynanchum thesioides. The goal is to provide a theoretical basis for developing food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic products using Cynanchum thesioides as a natural aromatic medicinal herb resource.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Yield of Methanol Extract and Solvent Fractions

In the measurement of antioxidant activity, the yield of natural aromatic plant extracts holds significant importance in terms of productivity and cost-effectiveness, as the extraction of antioxidant components can vary depending on the solubility differences of the solvents used. To evaluate the components of the methanol extract from

Cynanchum thesioides, sequential fractionation was performed using organic solvents with different polarities, namely n-hexane, dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, n-butanol, and water. The yield of the methanol extract from

Cynanchum thesioides was found to be 13.33%. The yields of the fractions obtained with each organic solvent (on a dry basis) are presented in

Table 1. The water fraction showed the highest yield at 13.92%, followed by n-hexane, n-butanol, dichloromethane, and ethyl acetate fractions with yields of 7.25%, 5.80%, 2.15%, and 1.29%, respectively.

2.2. Total Polyphenol Content

Polyphenols are aromatic compounds with two or more phenolic hydroxyl (-OH) groups in one molecule, including flavonoids, tannins, catechins, and others. These compounds give color to aromatic plants and possess functional activities such as antioxidant and anticancer properties [

12]. The total polyphenol content of each fraction from

Cynanchum thesioides is shown in

Table 2. The results indicate that the ethyl acetate fraction had the highest polyphenol content at 112.54 ± 0.59 mg GAE/g (

p < 0.05), followed by n-butanol, dichloromethane, methanol, n-hexane, and water fractions with contents of 100.86 ± 0.63, 61.05 ± 0.78, 37.37 ± 0.20, 17.01 ± 0.20, and 5.92 ± 0.30 mg GAE/g, respectively (

p < 0.05). This suggests that the phenolic compounds in the methanol extract of

Cynanchum thesioides are predominantly present in the ethyl acetate fraction. According to the study by Wu et al., the ethyl acetate fraction of

Cynanchum bungei Decne., a medicinal aromatic plant in the Asclepiadaceae family, showed the highest total polyphenol content at 42.38 mg/g [

13]. This indicates that phenolic compounds such as quercetin, which are abundantly present in aromatic plants of the Asclepiadaceae family, interact well with ethyl acetate, making them easily soluble. Consequently, many studies have used ethyl acetate as a solvent for extraction and fractionation [

14,

15]. Based on these results, it is inferred that the ethyl acetate fraction in this study likely contains a rich variety of phenolic compounds, such as quercetin, tamarixetin, and thesioide oside.

2.3. Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP)

The ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) measures the antioxidant activity of a sample based on the reduction of the Fe

3+-TPTZ complex to Fe

2+-TPTZ at low pH, which reflects the degree of hydroxylation and polyphenol binding [

16]. The FRAP measurement results for each fraction of

Cynanchum thesioides are shown in

Table 3. The ethyl acetate fraction exhibited the highest FRAP value at 3.49 ± 0.00 M/g (

p < 0.05), followed by dichloromethane, n-butanol, methanol, n-hexane, and water fractions, which showed reducing powers of 2.32 ± 0.01, 2.24 ± 0.01, 1.52 ± 0.01, 1.20 ± 0.00, and 0.93 ± 0.00 M/g, respectively (

p < 0.05). Li reported a positive correlation between the antioxidant activity of phenolic substances and FRAP values, the trend observed in this study’s FRAP results is consistent with the total polyphenol content results of

Cynanchum thesioides [

17]. Therefore, it is inferred that the highest FRAP value of the ethyl acetate fraction in this study is due to its highest total polyphenol content.

2.4. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

The DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging activity assay is widely used to evaluate antioxidant activity. It measures the reduction and decolorization of the stable free radical DPPH by various compounds, making it a convenient method for assessing the activity of antioxidants such as ascorbic acid, cysteine, glutathione, tocopherol, polyhydroxy aromatics, and aromatic amines [

18]. The DPPH radical scavenging activity of the

Cynanchum thesioides methanol extract and its solvent fractions is expressed as IC

50 values in

Table 4. The ethyl acetate and n-butanol fractions exhibited the lowest IC

50 values, 0.42 ± 0.00 mg/mL and 0.48 ± 0.01 mg/mL, respectively, indicating the highest antioxidant activities among the methanol extract and its fractions (

p < 0.05). Following these were the dichloromethane, methanol, water, and n-hexane fractions with IC

50 values of 0.73 ± 0.00, 1.22 ± 0.00, 2.24 ± 0.03, and 6.12 ± 0.41 mg/mL, respectively (

p < 0.05). The IC

50 value for the positive control, ascorbic acid, was 0.01 ± 0.00 mg/mL. The results indicate that the ethyl acetate fraction, which had the highest total polyphenol content, also exhibited the highest DPPH radical scavenging activity. This is consistent with reports by Lee [

19] and Kim [

20] that higher polyphenol and flavonoid content in extracts correlates with increased antioxidant activity. It is suggested that the flavonols and triterpenoids, known for their antioxidant properties, are abundantly dissolved in the ethyl acetate and n-butanol fractions of

Cynanchum thesioides. Therefore, the methanol extract of

Cynanchum thesioides exhibited the highest DPPH radical scavenging activity when fractionated using ethyl acetate or n-butanol.

2.5. ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity

The ABTS radical scavenging activity assay is based on the generation of the activated cation radical ABTS+ through the reaction of ABTS with peroxidase and H

2O

2. The ABTS+ radical, which is blue-green, is reduced and decolorized by receiving electrons from antioxidant substances. This decolorization is then used to evaluate the antioxidant activity [

21]. The ABTS radical scavenging activity of the

Cynanchum thesioides methanol extract and its solvent fractions is expressed as IC

50 values in

Table 5. The ethyl acetate fraction showed the lowest IC

50 value of 0.43 ± 0.01 mg/mL, indicating the highest scavenging activity (

p < 0.05). This was followed by the n-butanol, dichloromethane, methanol, water, and n-hexane fractions, with IC

50 values of 0.60 ± 0.00, 0.92 ± 0.01, 1.61 ± 0.00, 3.48 ± 0.01, and 9.45 ± 0.02 mg/mL, respectively (

p < 0.05). The IC

50 value for the positive control, ascorbic acid, was 0.07 ± 0.00 mg/mL. Consistent with the results of the DPPH radical scavenging activity assay, the ethyl acetate fraction, which had the highest total polyphenol content, also exhibited the highest ABTS radical scavenging activity. This supports the findings of Kainama [

22] and Sanchez [

23], who reported a strong positive correlation between high antioxidant activity and high total polyphenol content in ethyl acetate fractions.

2.6. Reducing Power

Reducing power is an indication of the antioxidant capacity of a substance, where antioxidants stabilize free radicals by donating hydrogen to the ferric-ferricyanide (Fe

3+) complex, reducing it to the ferrous (Fe

2+) state. This reduction can be quantified by measuring absorbance; higher absorbance values correspond to stronger reducing power and result in a more greenish color [

24]. The EC

50 values of the reducing power of the

Cynanchum thesioides methanol extract and its solvent fractions are presented in

Table 6. The ethyl acetate and n-butanol fractions exhibited the most potent reducing power with EC

50 values of 0.87 ± 0.00 and 0.95 ± 0.00 mg/mL, respectively, among the methanol extract and its fractions (

p < 0.05). Following these were the dichloromethane, methanol, water, and n-hexane fractions with EC

50 values of 1.38 ± 0.03, 1.40 ± 0.01, 1.92 ± 0.00, and 10.36 ± 0.30 mg/mL, respectively (

p < 0.05). The EC

50 value for the positive control, ascorbic acid, was 0.04 ± 0.00 mg/mL. It is known that the reducing power activity of antioxidants is closely related to their ability to inhibit the formation of peroxides, prevent the binding of transition metals, and scavenge radicals [

25]. This aligns with the results of this study, which showed similar trends in the reducing power and DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging activities. Therefore, it was confirmed that higher DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging activities correspond to higher reducing power in the

Cynanchum thesioides methanol extract and its fractions.

2.7. Superoxide Dismutase-like Activity

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) is an antioxidant enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of harmful reactive oxygen species within cells into hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) and oxygen (O

2) through the reaction (2O

2 + 2H

→ H

2O

2 + O

2). The H

2O

2 generated by SOD is further converted into harmless water and oxygen molecules by peroxidase or catalase, thus protecting the body [

26]. The results of SOD-like activity measurements for the fractions of

Cynanchum thesioides are shown in

Table 7. The ethyl acetate fraction exhibited the highest activity at 30.36 ± 0.44% (

p < 0.05), followed by the n-butanol, dichloromethane, water, n-hexane, and methanol fractions, with activities of 28.98 ± 1.52, 28.17 ± 1.12, 19.20 ± 0.93, 10.36 ± 0.30, and 14.72 ± 1.36%, respectively (

p < 0.05). This study found a similar trend between the total polyphenol content and SOD-like activity measurements of the

Cynanchum thesioides fractions. Previous reports by Kim [

1] and Azuma [

27] have indicated that higher polyphenol content is associated with greater SOD-like activity. It is speculated that this is due to the presence of quercetin and similar phenolic antioxidant compounds in the methanol extract and fractions of

Cynanchum thesioides. SOD is highly effective in eliminating free radicals and, therefore, has garnered significant interest in the pharmaceutical field for its superior efficacy compared to other antioxidants, and it is also widely used in anti-inflammatory and anti-aging cosmetic products [

1]. Consequently, the extract of

Cynanchum thesioides could potentially aid in the removal of reactive oxygen species both in the body and in food products.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and Extraction Preparation

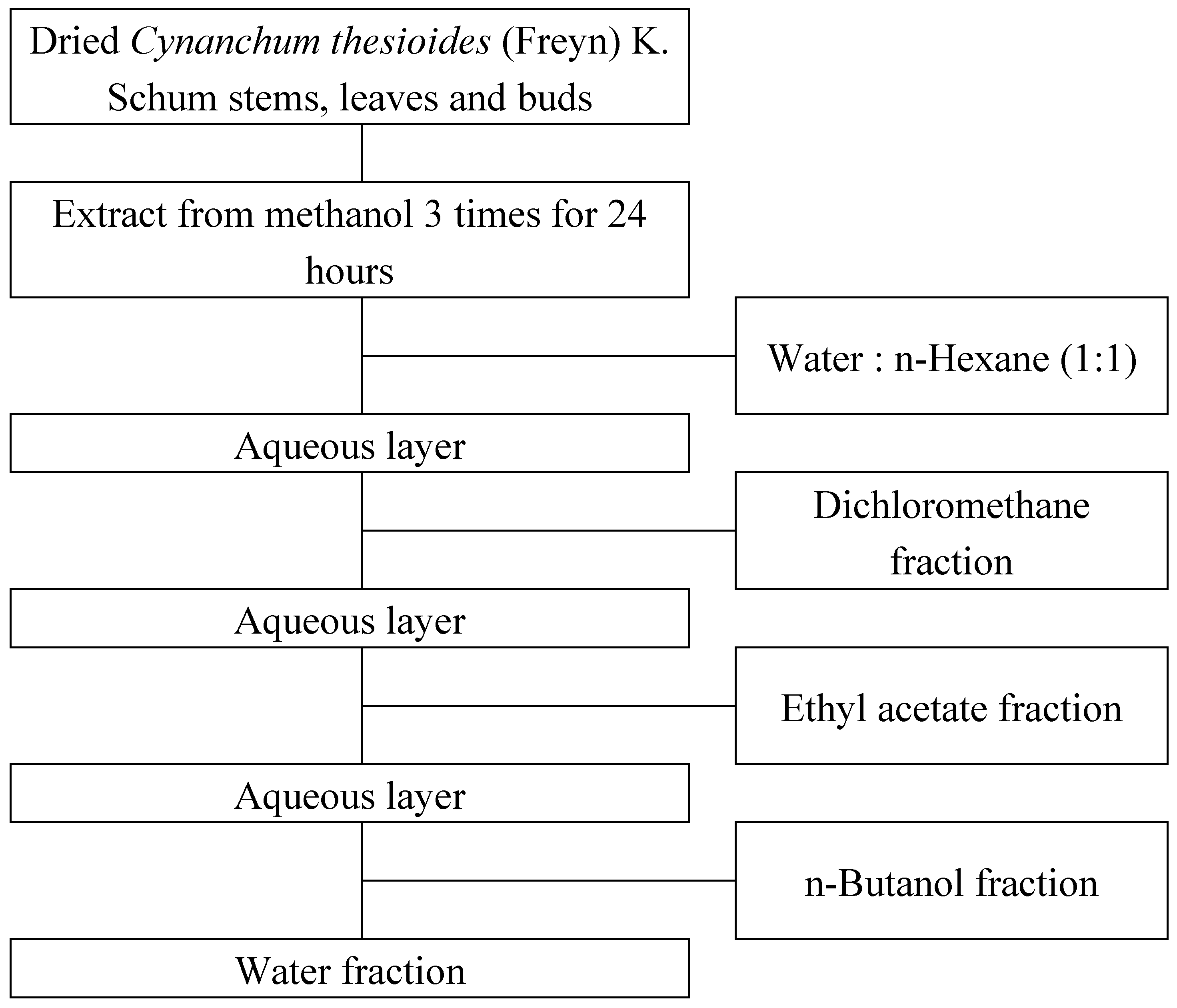

Cynanchum thesioides was collected from Inner Mongolia, China and purchased air-dried, and the whole herb including stems, leaves and flower buds were cut into 10-15 mm lengths, mixed equally and used for the experiments and analyses. A sample of 30 g was subjected to three rounds of extraction at room temperature, each lasting 24 hours, using methanol (99.5%, Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd., Pyeongtaek, Korea) in a 10:1 (w/v) ratio. The extracts were filtered using filter paper (Whatman No. 4, Whatman International Ltd., Maidstone, UK). The filtrate was then subjected to methanol removal and concentration under reduced pressure using a rotary vacuum evaporator (EYELA SB-1000S, Rikakikai Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) in a 40 °C heating bath. The methanol extract was dissolved in 200 mL of distilled water, as shown in

Figure 1, and then mixed with n-hexane (95%, Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd.) in a 1:1 (v/v) ratio. The mixture was fractionated using a separatory funnel and concentrated under reduced pressure with a rotary vacuum evaporator (EYELA SB-1000S, Rikakikai Co., Ltd.) in a 40 °C heating bath to obtain the n-hexane fraction. The same method was applied sequentially with dichloromethane (99.5%, Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd.), ethyl acetate (99.5%, SK Chemicals Co., Ltd., Seongnam, Korea), n-butanol (99%, Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd.), and water to obtain each fraction. All fractions were stored at temperatures below 4 °C and used in subsequent experiments. Each fraction was dissolved in DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide, Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd.) for the experiments.

3.2. Total Polyphenol Content

The total polyphenol content was measured by referencing the methods of Folin and Denis [

28]. A mixture of Folin-Ciocalteu’s phenol reagent (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) and distilled water at a ratio of 1:2 (v/v) was prepared. To this mixture, 40 μL of the sample was added and allowed to react in the dark at room temperature for 3 minutes. Subsequently, 600 μL of 10% Na

2CO

3 (Duksan Pure Chemical Co., Ltd., Ansan, Korea) was added, and the reaction was allowed to proceed in the dark at room temperature for 1 hour. The absorbance was then measured at 765 nm using a xMark™ Microplate Absorbance Spectrophotometer (168-1150, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The total polyphenol content was calculated by inserting the absorbance values into a standard curve prepared using gallic acid (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) as the standard. The results were expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per gram of dry sample (mg GAE/g).

3.3. Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP)

The ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) was measured based on the method of Benzie and Strain [

29]. An acetate buffer (300 mM, pH 3.6) was prepared by mixing sodium acetate (Shimakyu’s Pure Chemical Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) and acetic acid (Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd.). A 10 mM solution of 2,4,6-tris(2-pyridyl)-s-triazine (TPTZ, Sigma-Aldrich Co.) in 40 mM HCl (Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd.) and a 20 mM solution of FeCl

3·6H

2O (Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd.) were then mixed in a ratio of 10:1:1 (v/v/v). The mixture was incubated at 37 °C in an incubator (650D, Fisher Scientific, Ottawa, Canada) for 10 minutes. For the assay, 30 μL of the sample was mixed with 90 μL of distilled water and 0.9 mL of the FRAP reagent, and the reaction was carried out at 37 °C for 10 minutes. The absorbance was measured at 593 nm. The FRAP values were calculated using a standard curve prepared with FeSO

4·7H

2O (Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd.), and the results were expressed as the molar concentration of FeSO

4·7H

2O per gram of sample.

3.4. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

The DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging activity was measured based on the method of Blois [

30]. The sample and a 0.2 mM DPPH solution (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) were mixed in a 1:1 (v/v) ratio and allowed to react in the dark at room temperature for 30 minutes. The absorbance was then measured at 517 nm. The DPPH radical scavenging activity was expressed as a percentage using the following equation (1), and the IC

50 value (the inhibitory concentration at which 50% of radicals are scavenged) was calculated and expressed in mg/mL. In this study, ascorbic acid (Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd.), a known antioxidant, was used as a positive control for comparison.

3.5. ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity

The ABTS radical scavenging activity was measured based on the method of Fellegrini [

31]. The ABTS reagent was prepared by adding 5 mL of distilled water to 88 μL of 140 mM K

2S

2O

8 (Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd.) and then adding two ABTS diammonium salt tablets (Sigma-Aldrich Co.). This mixture was allowed to react in the dark for 14-16 hours. The resulting solution was then diluted with 95% ethanol (Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd.) at a ratio of 1:88 (v/v) until the absorbance measured at 734 nm reached 0.7 ± 0.02. For the assay, 50 μL of the sample was mixed with 1 mL of the diluted ABTS reagent and allowed to react in the dark for 2 minutes and 30 seconds. The absorbance was then measured at 734 nm. The ABTS radical scavenging activity was expressed as a percentage using the following equation (2), and the IC

50 value (the inhibitory concentration at which 50% of radicals are scavenged) was calculated and expressed in mg/mL. In this study, ascorbic acid (Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd.), a known antioxidant, was used as a positive control for comparison.

3.6. Reducing Power

The measurement of reducing power was conducted based on the method of Oyaizu [

32]. To 125 μL of the sample, 125 μL of sodium phosphate buffer (200 mM, pH 6.6), prepared by mixing sodium phosphate monobasic (J.T. Baker Chemical Co., Phillipsburg, NJ, USA) and sodium phosphate dibasic (Sigma-Aldrich Co.), and 125 μL of 1% potassium ferricyanide (Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd.) were sequentially added and mixed. The resulting mixture was then reacted in a 50 °C heating bath for 20 minutes, followed by cooling at room temperature for 10 minutes. After cooling, 125 μL of 10% trichloroacetic acid (Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd.) was added, and the mixture was centrifuged (Smart R17, Hanil Science industrial Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea) at 6,000 rpm for 10 minutes. To 250 μL of the supernatant, 250 μL of distilled water and 25 μL of 1% ferric chloride (Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd.) were added, and the absorbance was measured at 700 nm. The reducing power of the sample was expressed as a percentage (%) by converting the absorbance values to a range of 0 to 100%, where an absorbance range of 0 to 1 was considered equivalent to 0 to 100%. The EC

50 (effective concentration) value, representing the sample concentration at which 50% reducing power is observed, was calculated and expressed in mg/mL.

3.7. Superoxide Dismutase (SOD)-like Activity

The measurement of superoxide dismutase (SOD)-like activity was conducted based on the method of Marklund [

33]. To 40 μL of the sample prepared at a concentration of 1 mg/mL, 520 μL of Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.5), prepared by mixing Tris (50 mM, Sigma-Aldrich Co.) and EDTA (10 mM, Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd.), and 40 μL of 7.2 mM pyrogallol (Sigma-Aldrich Co.) were thoroughly mixed. The mixture was then reacted at 25 °C for 10 minutes. Subsequently, 20 μL of 1 N HCl was added to stop the reaction, and the absorbance was measured at 420 nm. The results were expressed as a percentage (%), and the SOD-like activity was calculated using the following equation (3).

where, A = Absorbance at 420 nm determined with sample; B = Absorbance at 420 nm determined with buffer instead of pyrogallol; C = Absorbance at 420 nm determined with buffer instead of sample.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we evaluated the antioxidant activity of different solvent fractions of Cynanchum thesioides methanol extract to provide a theoretical basis for product development using this natural aromatic medicinal herb plants. The methanol extract yield was 13.33%, with the water fraction yielding the highest among the solvent fractions, followed by n-hexane, n-butanol, dichloromethane, and ethyl acetate. The ethyl acetate fraction exhibited the highest antioxidant activity based on total polyphenol content and ABTS radical scavenging activity measurements. The results for DPPH radical scavenging activity, reducing power, and SOD-like activity showed no significant differences between the ethyl acetate and n-butanol fractions, both displaying the highest activity, while the FRAP activity measurement indicated the n-butanol fraction had the third highest value. Despite the ethyl acetate fraction demonstrating the highest antioxidant activity, its low yield of 1.29% makes it unsuitable for product development considering productivity and economic feasibility. The n-butanol fraction, with the second-highest antioxidant activity and a yield of 5.80% (more than four times higher than the ethyl acetate fraction), is deemed suitable for product development and production, balancing both productivity and economic feasibility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.K.; Validation, W.K.; Formal analysis, T.L.; Data curation, T.L.; Writing—original draft, T.L.; Writing—review & editing, W.K.; Supervision, W.K.; Project administration, W.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) grant funded by the Korea Government (MOTIE) (RS-2024-00409639, HRD Program for Industrial Innovation) and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (RS-2023-00281517).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kim, M.S.; Kim, K.H.; Jo, J.E.; Choi, J.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, J.H.; Jang, S.A.; Yook, H.S. Antioxidative and antimicrobial activities of Aruncus dioicus var. kamtschaticus Hara extracts. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2011, 40, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, S.C.; Kho, E.G.; Choi, S.H.; Ryu, G.C. Protective effect of naringin on carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic injury in mice. J. Environ. Toxicol. 2008, 23, 325–335. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.M.; Moon, H.I. Antioxidants and acetyl-cholinesterase inhibitory activity of solvent fractions extracts from Dendropanax morbiferus. Korean J. Plant Res. 2018, 31, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Cai, F.J.; Zhao, W.; Tian, J.L.; Kong, D.G.; Sun, X.H.; Liu, Q.; Chen, Y.R.; An, Y.; Wang, F.L.; et al. Cynanchum auriculatum Royle ex Wight., Cynanchum bungei Decne., and Cynanchum wilfordii (Maxim.) Hemsl.: Current research and prospects. Molecules. 2021, 26, 7065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Zhang, Y.K. Research progress of Cynanchum thesioides (Freyn) K. Schum. Shandong J. Anim. Sci. Vet. Med. 2020, 12, 54–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gou, Z.P.; Yang, Y.J.; Zhao, R.N. Revision of Latin names of the medicinal plants of genus Cynanchum in Gansu Province. Northwest Pharma J. 2001, 16, 56–57. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.J.; Chang, F.H.; Jie, H.X.; Qu, B.; Liu, C.; Lv, X.L.; Bai, T.Y. Quality standard of Cynanchum thesioides (Freyn) K. Schum. Central S. Pharm. 2014, 12, 918–921. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, X.J.; Yang, Z.R.; Zhang, F.L.; Hao, L.Z.; Zhang, X.Y. Study on the flowering biology and pollination adaptability of Cynanchum thesioides (Freyn) K. Schum. J. Chinese Hortic. Plant. 2017, 2616. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Chen, G.; Qiao, L.; Zhang, N.; Lv, A.L.; Dang, Q.; Pei, Y.H. The chemical constituents from the fruits of Cynanchum thesioides (Freyn) K. Schum. Chin. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 17, 101–103. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, R.H. Comparative study on antioxidant activities of 100 medicinal plants from Inner Mongolia. Master’s thesis, Inner Mongolia Normal University, 2013.

- Tang, M.W.; Liao, K.; Wei, X.; Xie, Z.X.; Fu, C.H.; Jin, W.W. Research progress and application of edible and medicinal plant Cynanchum thesioides. J. Food Saf. Qual. 2020, 11, 7684–7693. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.H. The study on verification of cosmeceutical activities from Aster glehni Fr. Schm. and application of oleosome on advanced formulation. MS Thesis, Daegu Haany University, 2010.

- Wu, C.D.; Zhang, M.; He, M.T.; Gu, M.F.; Lin, M.; Zhang, G. Selection of solvent for extraction of antioxidant components from Cynanchum auriculatum, Cynanchum bungei, and Cynanchum wilfordii roots. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawzy, G.A.; Abdallah, H.M.; Marzouk, M.S.A.; Soliman, F.M.; Sleem, A.A. Antidiabetic and antioxidant activities of major flavonoids of Cynanchum acutum L. (Asclepiadaceae) growing in Egypt. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C. 2008, 63, 658–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kviecinski, M.R.; Felipe, K.B.; Correia, J.F.G.; Ferreira, E.A.; Rossi, M.H.; Gatti, F.M.; Filho, D.W.; Pedrosa, R.C. Brazilian Bidens pilosa Linne yields fraction containing quercetin-derived flavonoid with free radical scavenger activity and hepatoprotective effects. Libyan J. Med. 2011, 6, 5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.J.; Kim, K.H.; Yook, H.S. Whitening and antioxidant activities of solvent extracts from hot-air dried Allium hookeri. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 44, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.B.; Wong, C.C.; Cheng, K.W.; Chen, F. Antioxidant activities in vitro and total phenolic contents in methanol extracts from medicinal plants. Swiss Soc. Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 41, 385–390. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.C.; Kim, K.H.; Xu, H.D.; Park, D.H.; Choi, Y.S.; Hwang, H.R.; Lee, M.J.; Choi, J.J.; Kwon, M.S.; Yook, H.S. Antioxidative effects and anti-proliferative effects of MeOH, BuOH, and ethyl acetate fractions from Stephania delavayi Diels. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 38, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.S.; Kim, K.H.; Yook, H.S. Antioxidant effects of fractional extracts from strawberry (Fragaria ananassa var. ‘Seolhyang’) leaves. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 47, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Kim, N.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Han, I.A.; Yook, H.S. Study on antioxidant effects of fractional extracts from Ligularia stenocephala leaves. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012, 41, 1220–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.A.; Jang, Y.A. Efficacy of a cosmetic material from complex extracts of Vaccinium spp., Phellinus linteus, Castanea crenata, and Cimicifuga heracleifolia. Asian J. Beauty Cosmetol. 2017, 15, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainama, H.; Fatmawati, S.; Santoso, M.; Papilaya, P.M.; Ersam, T. The relationship of free radical scavenging and total phenolic and flavonoid contents of Garcinia lasoar PAM. Pharm. Chem. J. 2020, 53, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, C.S.; Gonzalez, A.M.T.; Garcia-Parrilla, M.C.; Granados, J.J.Q.; Serrana, H.L.G.; Martinez, M.C.L. Different radical scavenging tests in virgin olive oil and their relation to the total phenol content. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2007, 593, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byun, E.B.; Park, W.Y.; Ahn, D.H.; Yoo, Y.C.; Park, C.H.; Park, W.J.; Jang, B.S.; Byun, E.H.; Sung, N.Y. Comparison study of three varieties of red peppers in terms of total polyphenol, total flavonoid contents, and antioxidant activities. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 45, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.J.; Jung, C.J.; Seo, J.G.; Li, X.; Yu, Y.E.; Beik, G.Y. Effect of aeration process on changes of prosapogenin content and antioxidant activity of red ginseng powder extract. Korean J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 51, 576–583. [Google Scholar]

- Youn, S.J.; Cho, J.G.; Choi, U.K.; Kwoen, D.J. Change of biological activity of strawberry by frozen storage and extraction method. Korean J. Life Sci. 2007, 17, 1734–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, K.; Nakayama, M.; Koshika, M.; Ippoushi, K.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Hohata, K.; Yamauchi, Y.; Ito, H.; Higashio, H. Phenolic antioxidants from the leaves of Corchorus olitorius L. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 3963–3966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folin, O.; Denis, W. On phosphotungstic-phosphomolybdic compounds as color reagents. J. Biol. Chem. 1912, 12, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: The FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blois, M.S. Antioxidant determinations by the use of a stable free radical. Nature. 1958, 181, 1199–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, N.; Ke, R.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Screening of dietary carotenoids and carotenoid-rich fruit extracts for antioxidant activities applying 2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylenebenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid radical cation decolorization assay. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 379–389. [Google Scholar]

- Oyaizu, M. Studies on products of browning reaction: Antioxidative activities of products of browning reaction prepared from glucosamine. Jpn. J. Nutr. 1986, 44, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marklund, S.; Marklund, G. Involvement of the superoxide anion radical in the autoxidation of pyrogallol and a convenient assay for superoxide dismutase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1974, 47, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).