1. Introduction

Historically, plant-based preparations have been used to enhance human health. Plants offer a multitude of ways to harness their therapeutic properties. The most common application is in homemade remedies, such as herbal teas. Additionally, the vast chemical variety in plants presents endless possibilities for new drug development. Systematically searching and documenting traditional medicine knowledge is crucial to identify bioactive compounds that support human health, backed by various scientific disciplines, and possessing commercial significance. However, native plants used as "natural remedies" for various ailments may be toxic. To confirm the presence of bioactive molecules that align with traditional uses, and potentially reveal new properties, ranges of standardized bioassays are conducted. Ensuring the efficacy and safety of these herbal drugs requires qualitative and quantitative analyses, which includes standardizing active ingredients, authenticating botanical materials, and conducting scientific research in order to confirm health benefits and understand the action mechanisms of various botanicals (Chaachouay & Zidane, 2024). Moreover, maintaining the integrity and trust in botanical products is essential to ensure they are safe and effective for consumer use (European Medicines Agency, 2006).

The chemical profile of preparations obtained from the same plant may vary depending on the solvent(s), the temperature and extraction time applied. Additionally, the active ingredients are influenced by multiple factors such as intraspecies variation, environmental conditions, season of the year, time and methods of collection, geographical location, and the specific part of the plant used Therefore, managing the natural variations of botanicals and employing standardized extraction procedures, can help to produce extracts with consistent composition (Monagas et al, 2022).

Cancer ranks among the leading causes of death and contributes to a significant global health burden due to the substantial costs associated with managing the disease for those affected. Cancer represents a significant challenge for society, public health, and the economy in the 21st century. According to the global cancer statistics based on updated estimates from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), in 2022, there were an estimated 20 million new cases of cancer and 9.7 million deaths from cancer (IARC Newsletter, 2024).

Regarding their medicinal properties, it is a well-recognized fact that some botanical preparations have anticancer effects. The bioactive phytochemicals present in these preparations can modulate signaling cascades responsible of cell proliferation, apoptosis, angiogenesis and cell migration-invasion processes. The modulation of these signaling pathways, which are implicated in tumoral growth and metastasis, would explain the anticancer effects of the extracts. In a recent review, Chandra et al. (2023) have revealed that plants and their phytochemicals could be crucial in fighting a range of cancers, including those of the oral cavity, breast, lungs, cervix, colon, stomach, and liver. Certain bioactive agents are known to stimulate biological responses that may contribute to control cancer cells. Among natural compounds that can trigger anticancer activity, phenolic molecules have been reported to inhibit tumor growth, metastasis and angiogenesis (Bolat et al., 2024).

Botanical derivatives have been used as lead compounds for the development of new anticancer drugs worldwide. In consequence, it is expected that novel therapeutics derived from medicinal plants can be developed to treat patients with cancer. Despite their effective activity against cancer cells, botanical preparations are recognized to induce fewer side effects compared to current anticancer medicine due to their natural origin (Banerjee et al., 2023). The beneficial effects described for the botanicals in cancer can be attributed to the synergistic interaction among the phytochemicals present into the preparations (Gnanaselvan et al., 2023).

Additionally, the anti-oxidative activity of botanical extracts is well-known, and it is recognized to confers health-promoting effects. It is widely accepted there is a strong correlation between the phenolic content of plant-derived extracts and their ability to prevent oxidative damage in biological systems. Different studies have shown that plant´s complex matrices are more effective at preventing oxidative damage at the biological level than isolated phytochemicals (Pasqualetti et al., 2021; Vigliante et al., 2019). There is substantial evidence linking oxidative stress to human diseases. In particular, the reactive oxygen species (ROS) were reported to be involved in all stages of cancer, contributing to cancer progression and metastasis. Therefore, antioxidant activity can significantly influence the course of this disease and the inhibition of ROS production is considered a crucial strategy for preventing the spread of cancer (Chugh & Koul, 2021).

The study of botanical preparations for medicinal purposes requires determining the correlation between its chemical composition and the attributed biological properties, adding value to these botanicals as a source of bioactive molecules that can be applied in a wide range of manufactured products (Paschoalinotto et al., 2021). In particular, there are numerous studies destined to characterize biological preparations by the correlation between its phytochemical content with cytotoxicity and/or antioxidant properties (Aboushanab et al., 2023; Bhajan et al., 2023; Mazumder et al., 2023).

Tessaria absinthioides (Hook. & Arn.) DC, Asteraceae, popularly called “pájaro bobo”, is a native plant of Bolivia, Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay y and northern and central Argentina. It has been widely used by the native populations from Argentina and Chile, because its medicinal properties as xa hipocholesterolemic, hipoglucemic, and anti-inflammatory agent, and also for the treatment of digestive disorders (Kurina Sanz et al., 1997; Madaleno & Delatorre-Herrera, 2013; Torres-Carro et al., 2017; Campos-Navarro & Scarpa, 2013). In previous reports, the aqueous preparation of T. absinthioides exhibited selective cytotoxicity on cancer cells lines, affecting glioblastoma, cervicouterine, mammary and colorectal human cancer cells. The oral administration of the aqueous extract induced antitumoral effects, improving the overall survival of mice with colorectal cancer and reducing the tumoral growth of murine melanoma (Persia et al., 2017 and Sosa-Lochedino et al., 2019; 2022). Additionally, the antioxidant activity of the T. absinthioides aqueous preparation was demonstrated in vitro (Gomez et al., 2019) and in vivo, on the ApoE-KO mice (Quesada et al., 2021).

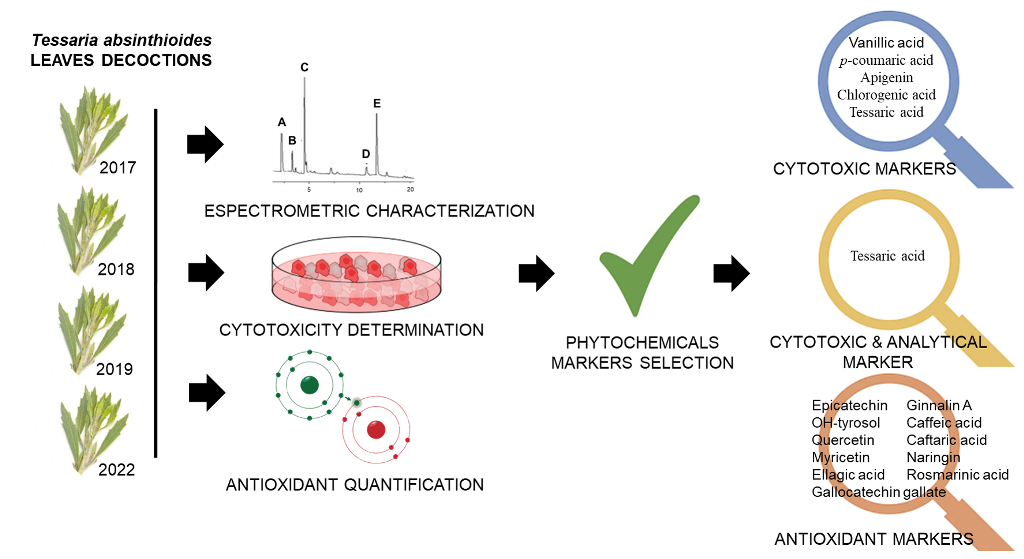

The aim of the current work is to analyze the T. absinthioides decoction (DETa) using a systematic correlation analysis, considering the chemical profile, cytotoxic activity in MCF-7 cells and antioxidant properties, to promote further research because on its anticancer potential.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemical Analysis

Using UHPLC-UV-Vis, UHPLC-DAD-FLD and UPLC-MS/MS, a total of thirty two compounds were quantified, of which 96.88% (n=31) are phenolic compounds belonging to phenolic acids, flavonoids, phenylethanoids and stilbenes groups. Additionally, the sesquiterpene eremophilane compound known as tessaric acid was identified and quantified.

A percentage of 70.97 (n=22) of the total quantified compounds was identified across the four collections analyzed. Concentrations are presented as mean ± standard deviation and categorized by year, as shown in

Table 1.

Out of the twenty two compounds identified and quantified in the four analyzed DETa collections, only six had been previously reported. Gomez et al., (2019) informed ginnalin A, chlorogenic, vanillic, and tessaric acids in lyophilized aqueous preparations of T. absinthioides, while hesperetin and quercetin were described in methanolic and hydroethanolic extracts (Rey et al., 2021 and 2023; Torres-Carro et al., 2017). In this study, the analysis of DETa collection samples resulted in the identification and quantification of sixteen phenolics compounds in T. absinthioides for the first time, including eight flavonoids: apigenin, catechin, epicatechin, gallocatechin gallate, luteolin, myricetin, naringin and quercetin-3-glucoside; six phenolic acids: caffeic, caftaric, ellagic, ferulic, p-coumaric, and rosmarinic acids; the phenylethanoid OH-tyrosol and the stilbene trans-piceatannol.

The most abundant compounds were tessaric acid (276.50 ± 224.31 µg/mL mean; range 559.50 – 29.80 µg/mL), rosmarinic acid (37.62 ± 38.58; 93.22 – 5.14 µg/mL), naringin (23.52 ±17.47; 44.43 – 1.92 µg/mL), caftaric acid (23.26 ± 35.02; 75.74 – 3,82 µg/mL), quercetin-3-glucoside (22.33 ± 21.92; 45.32 – 1.47 µg/mL) and chlorogenic acid (10.71 ± 1.96; 13.10 – 8.37 µg/mL). Additionally, the following compounds were detected and quantified: luteolin, caffeic acid, ginnalin A, ellagic acid, catechin, apigenin, myricetin and hesperetin (See table 1). The most abundant compounds identified (tessaric acid, chlorogenic acid, ginnalin A and hesperetin) are consistent with those reported in previous studies on T. absinthioides (Gomez et al., 2019; Rey et al., 2021 and 2023; Torres-Carro et al., 2017). In addition, ten compounds were detected occasionally in some of the collections; these compounds were phenolic acids as synaptic, syringic and trans-cinnamic, the phenylethanoid tyrosol; and flavonoids, as kaempferol-3-glucoside, naringenin, phloridzin, procyanidin B1, procyanidin B2 and rutin (See

Suplementary Table S1). These variations in the chemical profiles among DETa collections samples may be attributed to the edaphoclimatic conditions of each year, involving temperature, radiation, rainfall, soil characteristics, among other factors.

2.2. Determination of Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity

The total phenolic content (TPC) was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu method, and the antioxidant activity was measured using the DPPH decolorization method and the FRAP assay, for decoction samples of T. absinthioides harvested in different years. The quantification of polyphenols can be considered useful for estimating antioxidant activity (Chavez et al., 2020), due to the role that these compounds play in this bioactivity. Numerous publications applied the total phenols assay by Folin Ciocalteu Reagent and an Electron Transfer based antioxidant capacity assay (e.g., FRAP, TEAC, etc.) and often found excellent linear correlations between the “total phenolic profiles” and “the antioxidant activity”. This is not surprising if one considers the similarity of chemistry between the two assays (Huang et al., 2005).

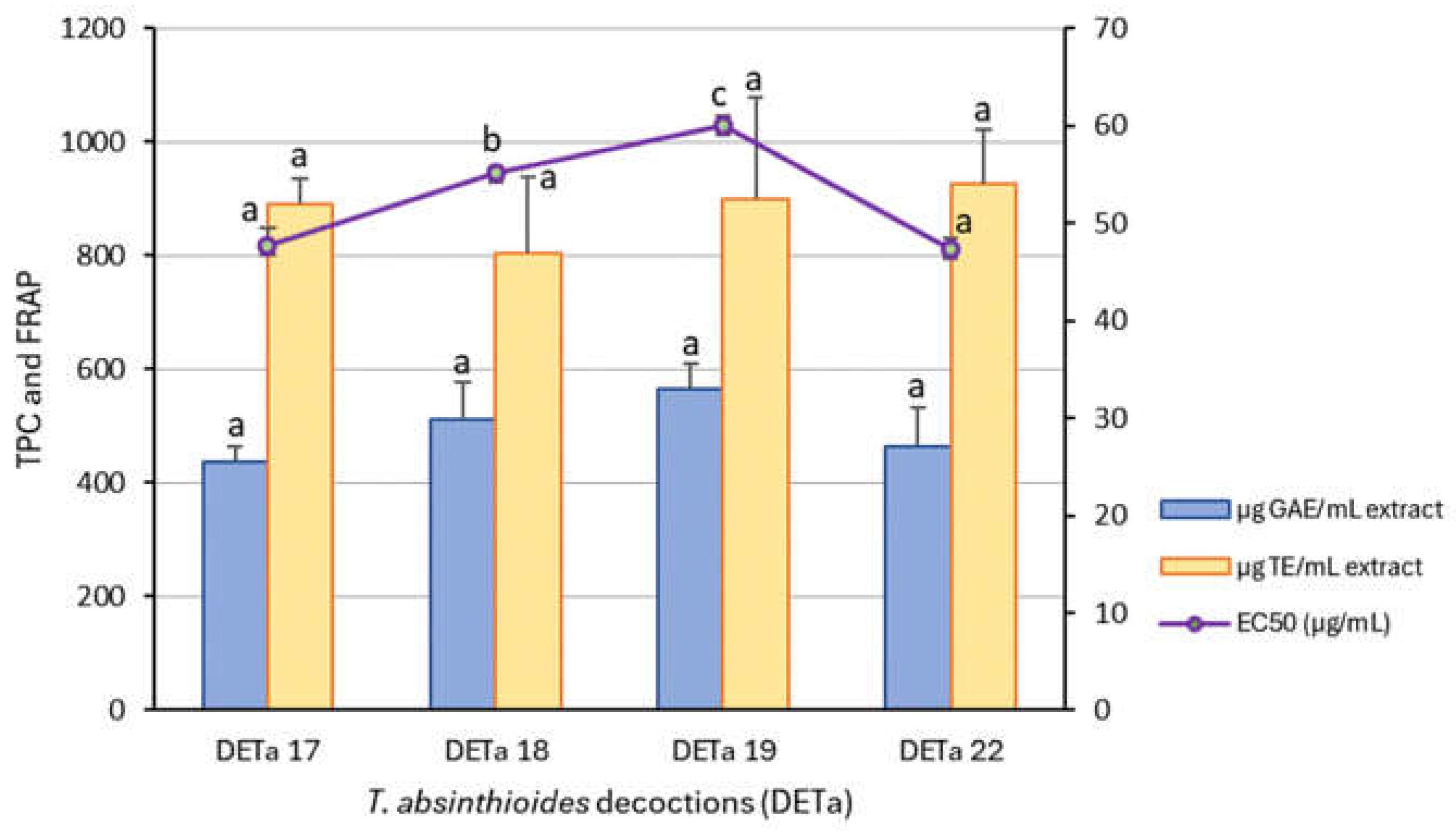

These results are shown in

Figure 1. Various studies have evaluated the antioxidant activity of this species (Gomez et al., 2019; Rey et al., 2021; 2023; Quesada et al., 2022). In this case, the DETa different collections samples did not show significant differences in TPC and FRAP assay. However, the results of DPPH radical decolorization assay, expressed as EC50 (µg/mL), showed lower values for DETa 2017 and DETa 2022 samples, indicating higher antioxidant capacity. Regarding the TPC content, there are not significant differences among the evaluated samples, with the highest value recorded in DETa 2019 (563.07 ± 44.15 µg GAE/mL), and the lowest in DETa 2017 (436.65 ± 25.57 µg GAE/mL). The TPC values for DETa 2018 and DETa 2022 were 511.31 ± 63.19 and 461.84 ± 70.62 µg GAE/mL, respectively (ANOVA, Tukey test, significance p<0.05). Similarly, Rey et al. (2021) reported a high total phenolic content in a 10% w/v decoction of T. absintioides, collected from the San Juan province in Argentina.

Concerning to the antioxidant potential, no significant differences (ANOVA, Tukey, p ≤ 0.05) were observed among the differents years of collection. The reducing power, assessed by the FRAP assay, remained consistent across all samples, suggesting a possible link to the bioactive compounds that reduce iron, with values ranging from 802.07 to 925.85 µgTE/mL. While the DPPH assay demonstrates effect in free radical scavenging, DETa 2018 (55.13 ± 0.68 µg/mL) and DETa 2019 (60.07 ± 0.85µg/mL) exhibited significant differences when compared to DETa 2017 (47.71 ± 1.73 µg/mL) and DETa 2022 (47.27 ± 1.23 µg/mL). The minor variations observed may be attributed to factors affecting plant physiology, including radiation and edaphoclimatics conditions. The stable antioxidant capacity of the species T. absintioides over various collection years is substantial for the development of potential phytopharmaceuticals. In this work, determinations were made directly from DETa. Although the TPC values obtained are lower than those obtained in other aqueous preparations such as green tea decoctions (908.46 µg GAE/mL), a common beverage with widely accepted medicinal properties and recognized for its high levels of polyphenols (Aggarwal et al. 2024, Si Said et al., 2024), they still fall within the range of high content for this type of compounds.

The antioxidant properties of T. absinthioides aqueous preparations have been previously documented through in vitro and in vivo studies. By the comparison of lyophilized decoctions from San Juan (Argentine), Mendoza (Argentine) and Antofagasta (Chile), Gomez et al. (2019) reported a strong antioxidant capability from all samples studied by DPPH, with IC50 values of 42, 41.6 and 43 µg/mL. These values resulted similar to the quantifications obtained in DETa 2017 and 2022, indicating similar antioxidant potency.

Moreover, Quesada et al. (2021) demonstrated a decrease in lipid peroxidation and an enhancement in the total antioxidant status in mice plasma after the oral administration of an aqueous extract. While, Rey et al. (2021), reported that in a hypercholesterolemic model using adult male rats, the consumption of T. absinthioides decoction led to a decrease in cholesterol levels, which is associated with the identified antioxidant compounds. Collectively, these findings affirm the significant antioxidant potential of T. absinthioides aqueous preparations and endorse their use in vivo.

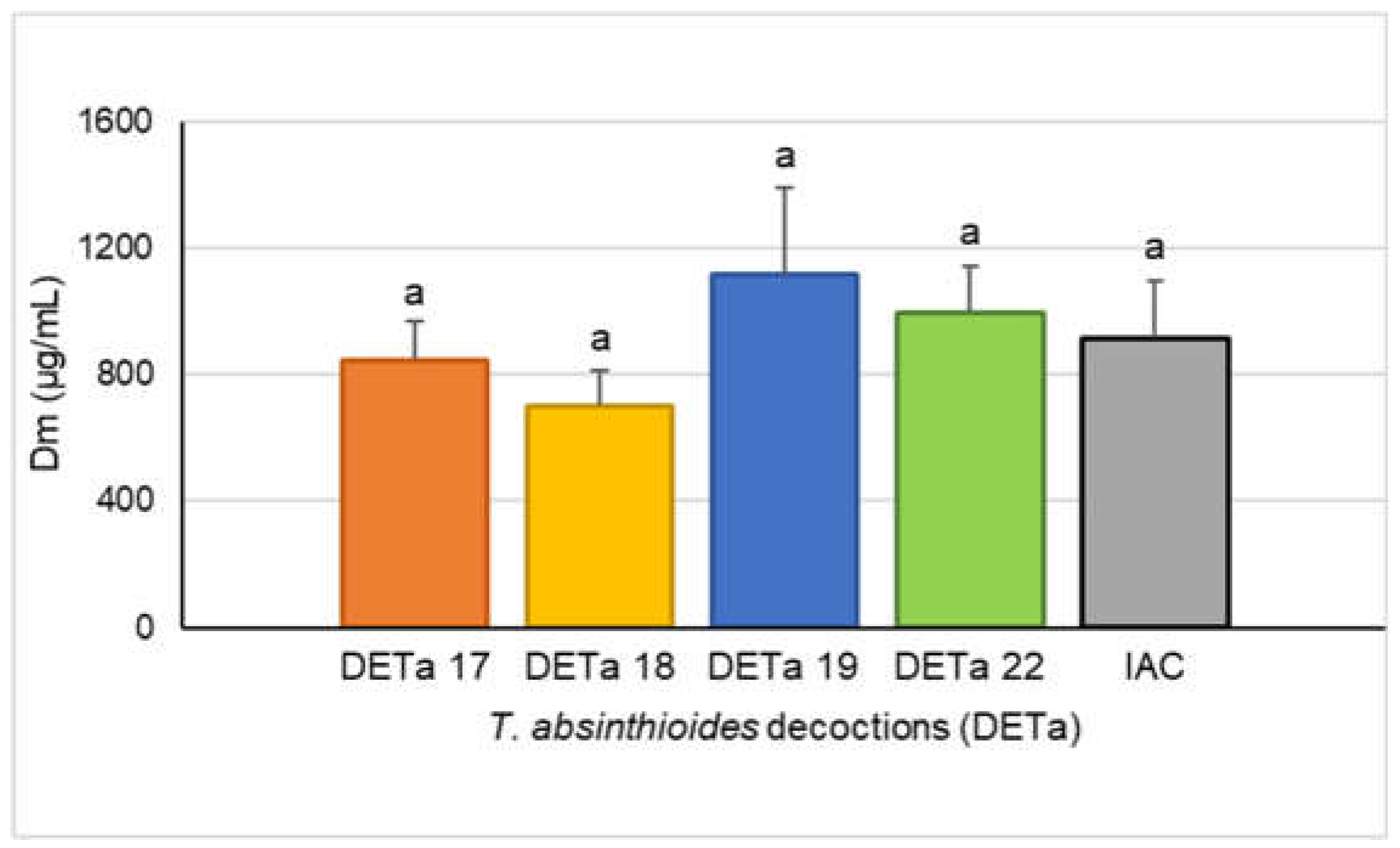

2.3. Determination of DETa Cytotoxic Acivity

To describe and compare the cytotoxicity induced by the 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2022 DETa collections, the MTT assay was used on the MCF-7 human breast adenocarcinoma cell line. It is a colorimetric test, commonly used to determine the cellular metabolic activity, providing information about cell proliferation, viability and toxicity under different paradigms of treatment. The cytotoxic potency of DETa was expressed by the median-dose effect (Dm) that is the concentration of treatment able to reduce cell proliferation by 50 %. The calculated Dm mean for the four DETa collections samples was 915.64 ± 182.13 µg/mL (interannual cytotoxicity, IAC), and there were no significant differences between each DETa year (ANOVA, Tukey, p ≤ 0.05). Moreover, while the highest cytotoxicity (lower dose that reduce 50% of proliferation) was measured on DETa 2018 with a Dm of 700.68 ± 111.36 µg/mL, the lowest was induced by DETa 2019 (Dm = 1116.00 ± 277.71 µg/mL). DETa 2017 and 2022 induced cytotoxicity with Dm values of 845.72 ± 123.45 and 997.5 ± 143.39, respectively (

Figure 2).

Cytotoxicity of the aqueous preparation of T. absinthioides against the MCF-7 cell line had been previously reported with (Persia et al., 2017). This study employed an alternative preparation method to preserve yield percentages and the phytochemical concentrations for each sample to ensuring the quality of DETa and facilitate the furthers correlation analyses.

In terms of comparative potency, DETa cytotoxicity resulted higher that some oncologic treatments prescribed by Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), such as Taohong Siwu Decoction (TSD), Shugan Liangxue Decoction (SLD), and a new TCM formula T33. These formulas, orally administered, are used clinically as adjuvant treatments on breast cancer due to their ability to increase the anticancer effects and control the side effects induced for chemotherapy (Jiang et al., 2021). When these treatments were tested against MCF-7 breast adenocarcinoma, Luminal A like, cell line, the reported Dm values were 5 mg/mL for T33 (Liu et al., 2019), 12 mg/ml for TSD (Liu et al., 2013) and 14.60 mg/mL for SLD (Zhang & Li, 2009). The Dm values obtainded in this study for the DETa collections obtained in this study ranged from 1.1 – 0.700 mg/mL, suggesting they could be used as a botanical preparation for breast cancer treatment.

2.4. Relationships between Bioactive Compound Content and Biological Properties

To determine the biological and chemical markers correlations, the twenty two compounds identified in the four DETa collections, cytotoxic and antioxidant activities were analized by the Pearson analysis (

Supplementary Table S2).

When the relation among particular phytochemicals were considered, the multivariate analysis evidence sixteen very strong correlations (r ≥ 0.95). The ellagic acid showed high correlations with epicatechin (r=0.98), gallocatechin gallate (r=1), myricetin (r=0.99), naringin (r=0.95), OH-tyrosol (r=0.97) and rosmarinic acid (r=0.98). Similarly, absolute correlations (r=1) were found between caffeic - caftaric acids and myricetin – rosmarinic acid.

Regarding to the compounds - cytotoxicity correlation, thirteen compounds presented a positive correlation values (see

Supplementary Table S2). While five of them evidenced weak correlation (Pearson r values ranging from 0.01 to 0.29): caffeic, caftaric, ferulic acids, ginnalin A and naringin; other three compounds showed moderate correlation (Person, r: 0.30 – 0.49): hesperetin, quercetin-3-glucoside and trans-piceatannol. Finally, the concentration of five compounds strongly correlated with cytotoxicity (Pearson, r > 0.5): apigenin, chlorogenic, p-coumaric, tessaric and vanillic acids (these correlation values are summarized in

Table 2). In this last group, special consideration should be given to chlorogenic acid (r=0.98) and tessaric acid (r=0.89), which evidenced the highest correlation values calculated.

The majority of the compounds analyzed that demonstrated a positive correlation with cytotoxicity have been widely reported for their effects on cancer cells. Previous in vitro studies reported no cytotoxic effects of tessaric acid on A2780 (ovarian), A549 (lung), HeLa (uterine cervix), SW1573 (lung), T47D (breast) nor WiDr (colon) cancer cell lines (León et al., 2009; Beer et al., 2022).

Among the five compounds that showed a strongly correlation with cytotoxicity, chlorogenic acid (Pearson, r=0.98) satnd out as an abundant dietary phenolic with demonstrated anticancer effects in various types of cancer cells by arresting cell proliferation, promoting apoptosis, and facilitating intracellular DNA impairment (Nguyen et al., 2024). Apigenin (r=0.74), a common flavonoid in the plant kingdom, has demonstrated anticancer properties in both in vitro and in vivo models (Fossatelli et al., 2023). Moreover, p-coumaric acid (r=0.73), derived from green propolis, has been reported to target antimelanoma cancer cells (Gastaldello et al., 2021), while vanillic acid (r=0.54) has been shown to impact the tumor growth on xenograft colorectal cancers (Gong et al., 2019).

When the antioxidant properties were considered, seventeen of the twenty two compounds present in the four DETa collections showed a positive correlation (see

Supplementary Table S2). Among them, the eleven phenolics that evidence a strong correlation (Pearson, r > 0.5) with the antioxidant capability are caffeic, caftaric, ellagic, rosmarinic acids, epicatechin, galocatechin gallate, ginnalin A, myricetin, naringin, OH-tyrosol, and quercetin (

Table 3).

Within the phenolics with strong antioxidant correlation, the presence of ginnalin A and naringin is remarkable, since these compounds evidenced the highest correlation values with r=0.96 and r=0.89, respectively. Ginnalin A is a phenolic molecule previously reported in aqueous preparations of T. absinthioides (Gomez et al., 2019 and Rey et al., 2021) with demonstrated antioxidant properties in cells, promoting the expression of antioxidant enzymes. In addition, ginnalin A has interesting chemopreventive activities in cancer cells, suppressing cell proliferation and reducing carcinogenesis (Ahsan et al., 2022). Regarding naringin, it is recognized as one of the main polyphenols present in citric fruits, and was previously recognized because of its antioxidant capability and its effects on cancer cell proliferation, angiogenesis and metastasis (Stabrauskiene et al., 2022). The remaining phytochemicals that evidenced strong correlation with antioxidant properties in DETa are widely accepted as phenolics present in foods, beverages and condiments, with a recognized reactive oxygen scavenger potency (Khojasteh et al., 2022; Tajner-Czopek et al., 2020; Qi et al., 2022; Tošović & Bren, 2020; Wang et al., 2023; Sochorova et al., 2020; Lammi et al., 2020)

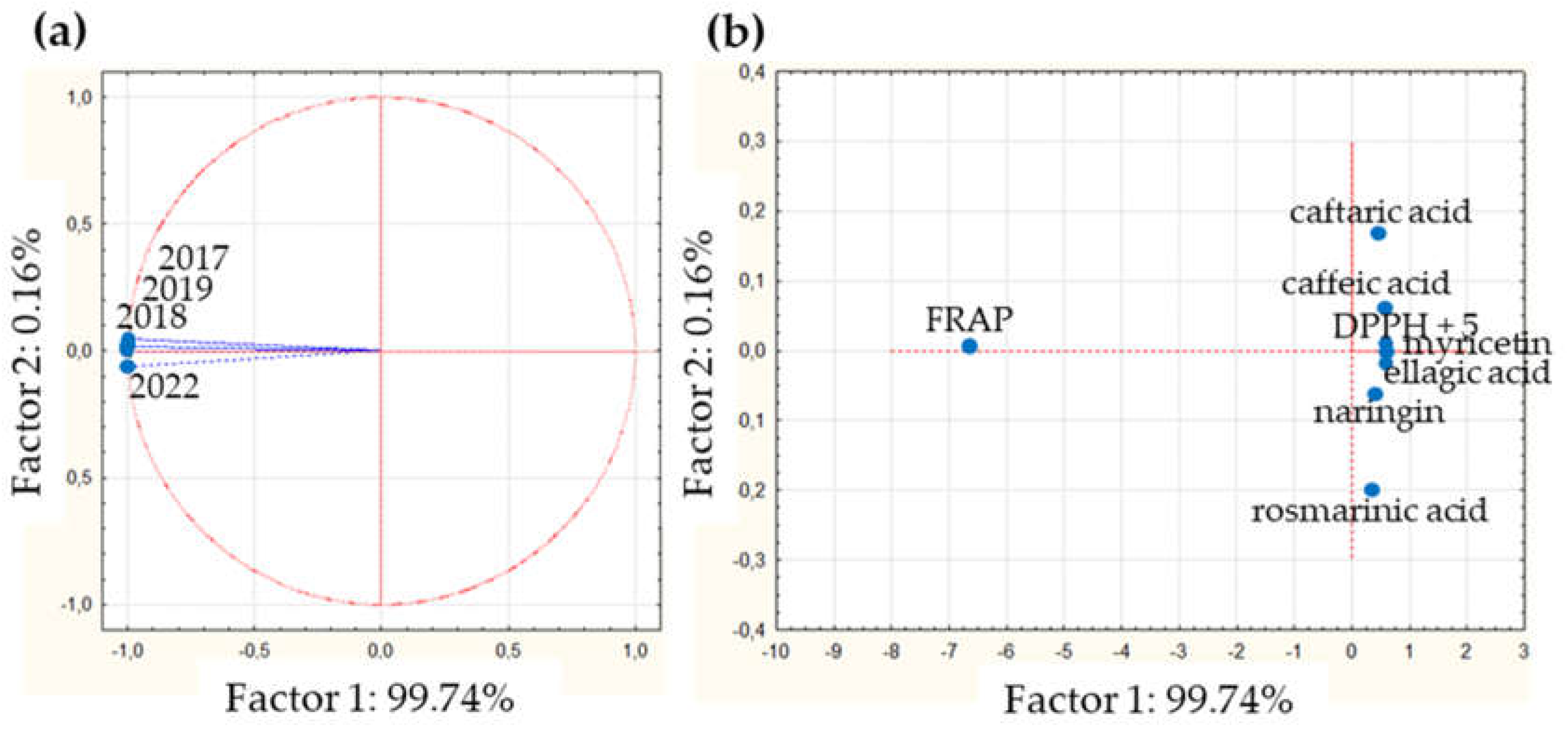

2.5. Principal Component Analysis

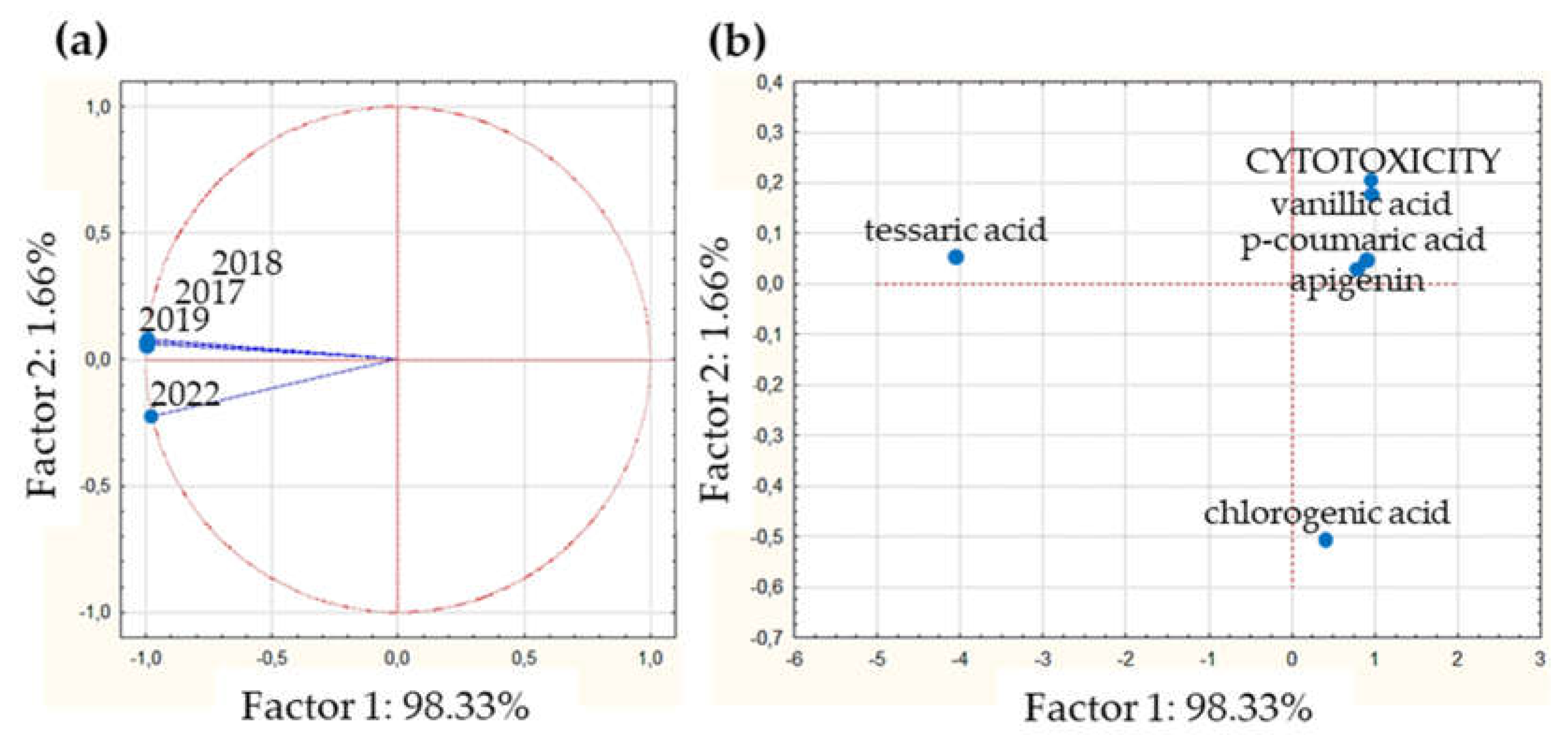

The principal component analysis (PCA) was applied to show the relationships between chemical composition, quantified compound values and bioassays of the samples (cytotoxicity and antioxidants properties).

When cytotoxicity was the property selected, the PCA was realized with four variables, corresponding to the years of collections (2017, 2018, 2019 and 2022) and six cases, including the concentrations of apigenin, chlorogenic, p-coumaric, tessaric, vanillic acids and cytotoxicity values (see

Table 2). Two principals components (PC) were generated, PC1 accounting for 98.33% of the variation and PC2, 1.66%; together they explain the 99.99% of the total variation (

Supplementary Figure S1a). When the projection on the factor-plane of collections is seen (

Figure 3a), they present similar, almost equal, projections values on factor 1. Values obtained were -0.99 for 2017, 2018 and 2019 collections; and -0.97 for the 2022, indicating that only slightly differences between the collections are present when the cytotoxicity is the explored variable. On the other hand, when the projections of major correlated compounds are analyzed on CP1 (

Figure 3b) only tessaric acid evidence a marked difference regard to the values estimated for the rest of the compounds. While the cytotoxicity value in CP1 coordinate is 0.98, the values are: 0.95 for vanillic acid, 0.87 for p-coumaric acid, 0.81 for apigenin and 0.41 for chlorogenic acid. Because of the variability explained by the CP2 is to small (only 1.66%), it could be considered that these compounds are strongly similar in terms of their cytotoxicity. Owing to the results obtained by the correlation analysis applied, these compounds could be proposed as bioactive citotoxicity markers for all DETa collections. Additionaly, tessaric acid could be considered as a chemical species marker, essential for ensuring the authenticity of T. absinthioides preparations.

To analyze the antioxidant activity relative to the chemical composition, the PCA considered four variables, corresponding to the years of collections (2017, 2018, 2019 and 2022) and thirteen cases, including the quantified compounds caffeic, caftaric, ellagic, rosmarinic acids, epicatechin, gallocatechin gallate, ginnalin A, myricetin, naringin, OH-tyrosol and quercetin, DPPH and FRAP values (see

Table 3). The two principal components explain almost the 100 % of variation; while PC1 explain 99.74%, PC2 0.16% (

Supplementary Figure S1b). The projection on the factor-plane of the harvests present almost identical values on CP1 (

Figure 4a), and the values obtained were 0.998 for 2017 collection, 0.999 for 2018, 0.999 for 2019 and 0.998 for 2022; indicating high similarities between DETa samples vs antioxidant activity. In the

Figure 4b, it is possible to visualize that only the projection of FRAP is notoriously different in CP1. Regarding the compounds, considering the value of CP2 (0.16%), all of them are similar to DPPH (CP1: 0.627). The individual values obtained were: epicatechin 0.625, OH-tyrosol 0.625, gallocatechin gallate 0.618, quercetin 0.611, myricetin 0.597, ellagic acid 0.587, ginnalin A 0.583, caffeic acid 0.574, caftaric acid 0.436, naringin 0.434 and rosmarinic acid 0.322. In accordance, these phenolics could be considered as markers for DETa collections antioxidant capability.

Summarizing, in the current study, as consequence of DETa botanical preparations analysis, it is possible to identify five compounds related to cytotoxicity markers: apigenin, chlorogenic, tessaric, p-coumaric and vanilic acids; and eleven compounds linked to the antioxidant capability: naringin, gallocatechin gallate, ginnalin A, myricetin, epicatechin, OH-tyrosol, quercetin caffeic, caftaric, ellagic and rosmarinic acids. In addition, tessaric acid also need to be considered as the specie analytical marker.

In accordance to this study results, the sixteen mentioned compounds represent a set of bioactive phytochemicals able to interact synergistically to ensure the demonstrated anticancer activities of DETa, covering the synergistic network of compounds that characterizes the activity of the botanical preparations.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

Standards of apigenin (≥95%), caffeic acid (99%), caftaric acid (≥97%), (+)-catechin (≥99%), chlorogenic acid (≥95%), ellagic acid (≥95%), (−)-epicatechin (≥95%), ferulic acid (≥99), gallic acid (GA, >95%), (−)-gallocatechin gallate (≥99%), ginnalin A (>97%), hesperetin (≥95%), hydroxytyrosol (≥99.5%), kaempferol-3-glucoside (≥99%), luteolin (≥98%), myricetin (≥96%), naringin (≥95%), naringenin (≥95%), p-coumaric acid (99%), phloridzin dehydrate (99%), procyanidin B1 (≥90%), procyanidin B2 (≥92%), quercetin (95%), quercetin 3-β-D-glucoside (≥90%), rosmarinic acid (98%), rutin trihydrate (99%), sinaptic acid (≥95%), syringic acid (≥95%), trans-cinnamic acid (≥95%), trans-piceatannol (>95%) and vanillic acid (≥97%), were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The standard of tyrosol (≥99.5%) was obtained from Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland). Tessaric acid (≥95%) was previously isolated from the aerial parts of T. absinthioides according to Donadel et al. (2005) (

Supplementary Figure S2). The acetonitrile (MeCN), ethanol (EtOH), methanol (MeOH) and formic acid (FA) were of HPLC-grade and acquired from Mallinckrodt Baker (Inc. Pillispsburg, NJ, USA). Ultrapure water (H

2O) was obtained from a Milli-Q system (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Commercial Folin-Ciocalteu (FC) reagent, 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

3.2. Plant Material and Decoction Preparation

T. absinthioides (Hook. & Arn.) DC. plants were collected during December on years 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2022 in Mendoza, Argentina (32° 89’ 79.310´´ S, 68° 87´ 57.630´´ W). The specimens were deposited in the Mendoza Ruiz Leal herbarium, voucher identification number MERL 65309. To obtain the T. absinthioides decoctions (DETa), the leaves of each collection (2017, 2018, 2019 and 2022) were washed with running water and 1% of sodium hypochlorite (V/V), rinsed with distilled water and dried at 22 – 24 °C, in a ventilated room, protected from direct solar irradiation until leaves reached a constant weight for 2 weeks. Then, the vegetal material was finely ground and stored at -20 °C until use. To prepare the decoctions 50 g of dry leaves were placed in 1 L of distilled water (5% P/V), boiled for 10 min and filtrated. Then, each decoction was sterilized by passing through a 0.22 μm pore size filter. The dry weight of each decoction was calculated three independent times, by triplicated, placing 1 mL of DETa into a sterile eppendorf at 37 °C, using a cultivation stove, until samples reach a constant weight for 2 weeks. The obtained yields were: 2017: 9.71 ± 0.04 mg/mL; 2018: 9.51 ± 0.04 mg/mL; 2019: 8.85 ± 0.05 mg/mL; and 9.20 ± 0.02 mg/mL. After this determination of soluble solids, the samples concentration were standardized (diluted with sterile MilliQ water) to obtain a equal final concentration of 8.8 mg/mL (dry weight/mL of DETa).

3.3. Chemical Analyses of T. Absinthioides Decoction

3.3.1. Quantification by UHPLC-UV-Vis

The UHPLC analysis was performed on an ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography system (Shimadzu, SIL30, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a binary pump system, an autosampler, a photodiode array UV-VIS detector and a C18 column (3 µm, 2.1 x 100 mm, UFLC Aqueous). Individual quantification of phenolic compounds was performed using the methodology previously reported by Soto et al. (2018) with a few modifications. Two mobile phases were used: water acidified with formic acid (0.1% v/v) as solvent A, and acetonitrile as solvent B. The gradient system was 0/5, 4/5, 17/30, 18/35, 19/50, 20/95, 21/95, 24/50, 27/5, and 37/5 min/% solvent B. The injection volume was 1 µL. The identification and quantification of each phenolic compounds were based on retention times recorded at λ=254 nm (vanillic acid and luteolin), λ=280 nm (cinnamic acid, tyrosol, catechin and naringenin), λ= 320 nm (caffeic acid, ferulic acid, apigenin, p-coumaric acid, chlorogenic acid, sinapic acid and rosmarinic acid) and 370 nm (rutin and quercetin). The UV-Vis spectra and standard curves were constructed using a commercial reference compounds (Sigma Aldrich, Atlanta, GA, USA). Data were expressed as µg/mL of DETa. All analyses were conducted in triplicate.

3.3.2. Quantification by UHPLC-DAD-FLD

To perform this analysis, the DETa samples were separated and quantified on a Dionex Ultimate 3000 (Dionex Softron GmbH, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Germany) equipped with a vacuum degasser unit, an autosampler, a quaternary pump, a chromatographic oven, a diode-array (Dionex DAD-3000 (RS)) and a dual-channel fluorescence detector (FLD-3400RS Dual-PMT) connected in series as described previously by Ferreyra et al. (2021). The Chromeleon 7.1 software was used to control all the acquisition parameters of the LC DAD-FLD system. The chromatographic separation was achieved on a reversed-phase Kinetex C18 column (3.0 mm × 100 mm, 2.6 μm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) using as mobile phases an aqueous solution of 0.1% FA (A) and MeCN (B). The following gradient was used: 0–1.7 min, 5% B; 1.7–10 min, 30% B; 10–13.5 min, 95% B; 13.5–15 min, 95% B; 15–16 min, 5% B; 16–19, 5% B. The total flow rate was set at 0.8 mL/min and the column temperature at 35 °C. The injection volume was 5 μL for standards and 1 μL to DETa samples.

The analytical flow cell for DAD was set to scan from 200 nm to 400 nm. A data collection rate of 5 Hz, a bandwidth of 4 nm and a response time of 1.000 s were used. Wavelengths of 254 nm, 280 nm, 320 nm and 370 nm were used for DAD, while an excitation wavelength (Ex) of 290 nm and a monitored emission (Em) response of 315 nm, 360 and 400 nm were used for FLD. A data collection rate of 10 Hz (peak width of 0.04 min corresponding to a response time of 0.8 s and a photomultiplier (PMT) gain of 5 units was used for FLD.

The compounds were identified by comparison of retention times (tR) with those of authentic standards. While, the quantification was done by an external calibration with pure standards. All measurements were carried out three times to ensure precision.

3.3.3. Quantification by UPLC-MS/MS

The LC-MS/MS analysis were performed on an ACQUITY H–Class UPLC equipped with a XEVO TQ-S micro triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters Corp, Milford, MA, USA) with electrospray ionization (ESI) source as was described by Ortiz et al. (2023). An UPLC ACQUITY BEH C18 (1.7 μm, 2.1 mm × 50 mm) column was used for separation at 35°C. The mobile phase consisted of 1% FA (A) and MeCN (B). The gradient conditions were as follows: 0–2 min 95% A; 6min 85% A; 10-13 min 0% A; 13.10-15 min 95% A. The calibration curve was constructed by using five standard solutions of tessaric acid (1.1, 2.2, 4.4, 6.6, and 8.8 ppm) in triplicate. The DETa samples were prepared at 44 ppm. The samples were dissolved in a mixture of MeOH-H2O (50:50) and filtered through a nylon membrane filter (0.22 µm). The injection volume was 10 µl. The data were acquired in ESI+ mode using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) function of two channels (transitions 249.00 > 203.00; 249.00 > 231.00). Capillary, Cone, and Collision energy were 3.00kV, 33.94V, and 20eV, respectively. MassLynx Software V4.2 (TargetLynx™, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) was used for data processing and calibration curve acquisition.

3.3.4. Determination of Total Phenolic Contents

The TPC was determined by the colorimetric methods Folin-Ciocalteu described by Heldrich (1990) modified by Luna et al. (2018). The DETa samples (10 μL) were 4 times diluted and mixed with MilliQ water (150 μL), Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (12.5 μL) and 20% (w/v) sodium carbonate solution (37.5 μL). Then, the mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 20 min. Absorbance was measured at wavelength of 765 nm using a microplate reader (ThermoScientific Multiscan, USA). TPC were determined by linear regression from a calibration plot constructed using gallic acid (0-2.5 mM) and expressed as mM of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per mg of extract of DETa (g GAE/mg extract).

3.4. Bioassays

3.4.1. Cytotoxicity Assay

The MCF-7 cell line, human breast adenocarcinoma (ATCC, Virginia, USA), was selected to determine the cytotoxicity effects of DETa samples. Cells were cultured as a monolayer in DMEM (Gibco, USA), containing 10 % v/v fetal bovine serum (Internegocios, Argentina), 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco, USA) and 3.7 mg/ml NaHCO3 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Cells were grown in a humidified atmosphere, containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Cytotoxicity was determined by the MTT method [(3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrasodiumbromide)], which is a colorimetric assay for assessing cell metabolic activity as was described previously (Persia et al, 2020). Briefly, in 96-well microplates, 3.5 x 103/100 μL MCF-7 cells were seeded; after 24 h, the medium was changed by fresh medium containing DETa treatments at indicated doses and doxorubicin (Onkostatil®, Microsules, Argentina) as positive and interassay control. After 72 h of treatment, the medium was replaced by MTT solution, plates were incubated for an additional 4 h, MTT solution was removed and DMSO were added to dissolve the formazan crystals. The optical density was measured at wavelength of 570 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific Multiscan, USA). The 100% viability (control) was obtained in untreated cells (without DETa) ; and the other values were calculated in accordance. The assays were performed three times in triplicate for each DETa sample.

3.4.2. Antioxidant Activity

The antioxidant activity of DETa samples were evaluated by DPPH and FRAP assays.

DPPH scavenging activity: The free radical scavenging effect of samples was evaluated by DPPH assay, according to the procedure described by Brand-Williams et al. [1995], modified by Luna et al. (2018). Scavenging activities were evaluated at 517 nm in a Multiskan FC microplate photometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). Quercetin was used as the reference compound. The DETa concentration providing 50% of radicals scavenging activity (EC50) was calculated by plotting the inhibition percentage and expressed in µg/mL. Analyses were performed in triplicate; and values were reported as mean ± SD.

Ferric-reducing antioxidant power assay (FRAP): The assay was performed in accordance to Benzie & Strain (1996), with some modifications by Luna et al. (2018). Briefly, the FRAP solution was freshly prepared by mixing 10 mL of acetate buffer 300 mM at pH 3.6, 1 mL of ferric chloride hexahydrate 20 mM dissolved in distilled water and 1 mL of 2,4,6-tris(2-pyridyl)-s-triazine 10 mM dissolved in HCl 40 mM. Ten µL of DETa samples solution were mixed with 190 µL of the FRAP solution in 96-well microplates in triplicate the change in absorbance were evaluated at 620 nm in a Multiskan FC microplate photometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). Results were obtained by linear regression from a calibration plot obtained with Trolox equivalent per mL. All samples were analyzed in triplicate and data are informed as mean ± SD. Results are expressed as µg TE/mL of DETa.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± standard error (SEM) of triplicates. When comparison between groups resulted necessary, they were evaluated using analysis of variance (ANOVA), and the means were compared by the Tukey´s multiple comparison test, considering significance when p ≤ 0.05. Cytotoxic potency was expressed as Dm, which is the median-effect dose (ED50) that reduces proliferation by 50%. The multivariate analyses were performed using the Pearson correlation coefficient and the principal component analysis (PCA). The GraphPad Prism 6.0 (Graph Pad Software Inc., USA), CompuSyn (ComboSyn, Inc., USA), XLSTAT software (Addinsoft, USA) and Statistica 7 (StatSoft Inc., USA) softwares were used to perform the analyses.

3.5.1. PEARSON Correlation

The correlation matrix was calculated, giving the correlation coefficients between each pair of variables tested, by the use of XLSTAT software (Addinsoft, USA, 2011). The Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) between compounds content in the DETa, cytotoxic and antioxidant activities were determined. Only compounds quantified in the four DETa samples were considered.

3.5.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

The PCA was implemented in the Statistica software to classify the different collections based on their bioactive compounds and biological properties. Only compounds which positively correlated with cytotoxicity, DPPH or FRAP (pearwise Pearson, correlation coefficient values, r ≤ 0.5) were considered and the calculated phytochemical concentration of each DETa samples analyzed. The data set regarding cytotoxicity consisted on a matrix of the order 4 x 6, where the columns represent the harvest (2017, 2018, 2019 and 2022), and the rows comprised the data for the five phytochemicals concentrations that correlate with the cytotoxicity estimated by MTT. Meanwhile, the data set related to the antioxidant activity consisted on a matrix of the order 4 x 13, where the columns represent the DETa collection samples and the columns include the concentrations of compounds that correlated with the antioxidant capacity estimated by DPPH and FRAP.

4. Conclusions

In this study, a correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between the compounds quantified, cytotoxic activity, and antioxidant properties of the DETa samples collection, obtained during four different years, to determine its potential oncological applications. The cytotoxic as well as the antioxidant activities did not vary among collections. Regarding the quantified compounds, apigenin flavone, naringin, gallocatechin gallate, ginnalin A, myricetin, epicatechin, OH-tyrosol, quercetin, chlorogenic, and tessaric, p-coumaric, vanillic, caffeic, caftaric, ellagic and rosmarinic acids correlated as bioactive and chemical markers. Moreover, tessaric acid could be established as a species marker.

In accordance with our knowledge, the current work is the first report that correlates the chemical composition of an aqueous preparation of T. absinthioides with its cytotoxic and antioxidant properties. Altogether, these results provide relevant information on the biological properties of DETa, encouraging further exploration of its potential application in future studies seeking novel starting points as a promising anticancer agent. However, more studies are necessary to expand the knowledge of the anti-oncologic properties of this plant botanical derivative.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.preprints.org, Table S1: Occasional DETa phytochemicals concentrations; Table S2: Complete PEARSON correlations of phytochemicals and biological properties; Figure S1: CPA Eigenvalues; Figure S2:

1H-NMR spectra - Tessaric acid.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.E.F., L.L., J.O., L.I.P., M.B.H. and C.G-L.; methodology, L.L., J.O., O.J.D., L.I.P., R.G. and L.G-G.; software, L.L., L.G-G. and C.G-L.; formal analysis, J.O., L.L., G.E.F., R.G., M.B.H. and C.G-L.; resources, R.G., J.O.D., G.E.F. and C.G-L; writing—original draft preparation, G.E.F., L.L., L.I.P., M.B.H. and C.G-L.; visualization, L.L., L.G-G. and C.G-L.; supervision, G.E.F. and C.G-L.; project administration, G.E.F. and C.G-L.; funding acquisition, R.G., G.E.F., M.B.H. and C.G-L. All authors have read and agreed to the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by ANPCyT (PICT-2020-SERIEA-03883; PICT-2019-2019-03791; PICT-2021-CAT-II-00030), CONICET PIP 112202101 00902CO, CICITCA-UNSJ (Argentina), SIIP-UNCuyo (06/J019-T1; PIO2023-SIIP: 80020230100034UN) and INTA (grant numbers 2019-PD-E7-I152).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

L.I.P. and J.O. hold a fellowship from CONICET. L.G-G. hold a fellowship from UNCuyo. L.L., and G.E.F. are professors from UNSJ. O.J.D. is professor from UNSL. R.G., M.B.H. and C.G-L. are professors from UNCuyo. R.G. is a researcher from INTA. Finally, M.B.H., G.E.F. and C.G-L. are researchers from CONICET.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aboushanab, S. A., Shevyrin, V. A., Melekhin, V. V., Andreeva, E. I., Makeev, O. G., & Kovaleva, E. G. (2023). Cytotoxic activity and phytochemical screening of eco-friendly extracted flavonoids from Pueraria montana var. lobata (Willd.) Sanjappa & Pradeep and Trifolium pratense L. Flowers Using HPLC-DAD-MS/HRMS. AppliedChem, 3(1), 119-140. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, G., Sharma, M., Singh, R., & Sharma, U. (2024). Plant-based natural product chemistry: An overview of the multistep journey involved in scientific validation of traditional knowledge. Studies in Natural Products Chemistry, 80, 327-377. [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, H., Islam, S. U., Ahmed, M. B., & Lee, Y. S. (2022). Role of Nrf2, STAT3, and Src as molecular targets for cancer chemoprevention. Pharmaceutics, 14(9), 1775. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S., Nau, S., Hochwald, S. N., Xie, H., & Zhang, J. (2023). Anticancer properties and mechanisms of botanical derivatives. Phytomedicine Plus, 3(1), 100396. [CrossRef]

- Beer, M. F., Reta, G. F., Puerta, A., Bivona, A. E., Alberti, A. S., Cerny, N., ... & Donadel, O. J. (2022). Oxonitrogenated Derivatives of Eremophilans and Eudesmans: Antiproliferative and Anti-Trypanosoma cruzi Activity. Molecules, 27(10), 3067. [CrossRef]

- Benzie IF, Strain JJ (1996) The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: The FRAP assay. Anal Biochem 239:70–76. [CrossRef]

- Bhajan, C., Soulange, J. G., Sanmukhiya, V. M. R., Olędzki, R., & Harasym, J. (2023). Phytochemical Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Tambourissa ficus, a Mauritian Endemic Fruit. Applied Sciences, 13(19), 10908. [CrossRef]

- Bolat, E., Sarıtaş, S., Duman, H., Eker, F., Akdaşçi, E., Karav, S., & Witkowska, A. M. (2024). Polyphenols: Secondary Metabolites with a Biological Impression. Nutrients, 16(15). [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams W, Cuvelier ME & Berset C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT– Food Sci Technol 1995; 28: 25–30. [CrossRef]

- Campos-Navarro, R., & Scarpa, G. F. (2013). The cultural-bound disease “empacho” in Argentina. A comprehensive botanico-historical and ethnopharmacological review. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 148(2), 349-360. [CrossRef]

- Chaachouay, N.; Zidane, L. Plant-Derived Natural Products: A Source for Drug Discovery and Development. Drugs Drug Candidates 2024; 3: 184-207. [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S., Gahlot, M., Choudhary, A. N., Palai, S., de Almeida, R. S., de Vasconcelos, J. E. L., . & Coutinho, H. D. M. (2023). Scientific evidences of anticancer potential of medicinal plants. Food Chemistry Advances, 2, 100239. [CrossRef]

- Chaves, N., Santiago, A., & Alías, J. C. (2020). Quantification of the antioxidant activity of plant extracts: Analysis of sensitivity and hierarchization based on the method used. Antioxidants, 9(1), 76. [CrossRef]

- Chugh, N. A., & Koul, A. (2021). Reactive Oxygen Species Mediated Cancer Progression and Metastasis: Amelioration by Botanicals. In Handbook of Oxidative Stress in Cancer: Mechanistic Aspects (pp. 1-14). Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Donadel, O. J., Guerreiro, E., María, A. O., Wendel, G., Enriz, R. D., Giordano, O. S., & Tonn, C. E. (2005). Gastric cytoprotective activity of ilicic aldehyde: Structure–activity relationships. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 15(15), 3547-3550. [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. (2006). Guideline on Specifications: Test Procedures and Acceptance Criteria for Herbal Substances, Herbal Preparations and Herbal Medicinal Products/Traditional Herbal Medicinal Products. Document No 2006. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/specifications-test-procedures-acceptance-criteria-herbal-substances-herbal-preparations-herbal-medicinal-products-traditional-herbal-medicinal-products-scientific-guideline.

- Ferreyra, S., Bottini, R., & Fontana, A. (2021). Tandem absorbance and fluorescence detection following liquid chromatography for the profiling of multiclass phenolic compounds in different winemaking products. Food Chemistry, 338, 128030. [CrossRef]

- Fossatelli, L., Maroccia, Z., Fiorentini, C., & Bonucci, M. (2023). Resources for Human Health from the Plant Kingdom: The Potential Role of the Flavonoid Apigenin in Cancer Counteraction. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(1), 251. [CrossRef]

- Gastaldello, G. H., Cazeloto, A. C. V., Ferreira, J. C., Rodrigues, D. M., Bastos, J. K., Campo, V. L., ... & Tefé-Silva, C. (2021). Green Propolis Compounds (Baccharin and p-Coumaric Acid) Show Beneficial Effects in Mice for Melanoma Induced by B16f10. Medicines, 8(5), 20. [CrossRef]

- Gnanaselvan, S., Yadav, S. A., Manoharan, S. P., & Pandiyan, B. (2023). Uncovering the anticancer potential of phytomedicine and polyherbal's synergism against cancer–A review. Biointerface Research in Applied Chemistry, 13(4), 356.

- Gómez, J., Simirgiotis, M. J., Lima, B., Gamarra-Luques, C., Bórquez, J., Caballero, D., ... & Tapia, A. (2019). UHPLC–Q/Orbitrap/MS/MS fingerprinting, free radical scavenging, and antimicrobial activity of Tessaria absinthiodes (Hook. & arn.) DC.(Asteraceae) lyophilized decoction from Argentina and Chile. Antioxidants, 8(12), 593. [CrossRef]

- Gong, J., Zhou, S., & Yang, S. (2019). Vanillic acid suppresses HIF-1α expression via inhibition of mTOR/p70S6K/4E-BP1 and Raf/MEK/ERK pathways in human colon cancer HCT116 cells. International journal of molecular sciences, 20(3), 465. [CrossRef]

- Heldrich K (1990) Official methods of analysis of the association of official analytical chemists. Arlington, VA: Association of Official Chemists. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D., Ou, B., & Prior, R. L. (2005). The chemistry behind antioxidant capacity assays. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 53(6), 1841-1856. [CrossRef]

- IARC Newsletter, 2024. https://www.iarc.who.int/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/IARCNewsletter_May2024.pdf.

- Jiang, H., Li, M., Du, K., Ma, C., Cheng, Y., Wang, S., ... & He, Y. (2021). Traditional Chinese Medicine for adjuvant treatment of breast cancer: Taohong Siwu Decoction. Chinese Medicine, 16, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Khojasteh, A., Mirjalili, M. H., Alcalde, M. A., Cusido, R. M., Eibl, R., & Palazon, J. (2020). Powerful plant antioxidants: A new biosustainable approach to the production of rosmarinic acid. Antioxidants, 9(12), 1273. [CrossRef]

- Kurina Sanz, M. B., Donadel, O. J., Rossomando, P. C., Tonn, C. E., & Guerreiro, E. (1997). Sesquiterpenes from Tessaria absinthioides. Phytochemistry, 44(5), 897-900. [CrossRef]

- Lammi, C., Bellumori, M., Cecchi, L., Bartolomei, M., Bollati, C., Clodoveo, M. L., ... & Mulinacci, N. (2020). Extra virgin olive oil phenol extracts exert hypocholesterolemic effects through the modulation of the LDLR pathway: In vitro and cellular mechanism of action elucidation. Nutrients, 12(6), 1723. [CrossRef]

- León, L. G., Donadel, O. J., Tonn, C. E., & Padrón, J. M. (2009). Tessaric acid derivatives induce G2/M cell cycle arrest in human solid tumor cell lines. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry, 17(17), 6251-6256. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Fan, J., Wang, S., Wang, Z., Wang, C., Zuo, Z., ... & Huang, Y. (2013). Transcriptional profiling of Chinese medicinal formula Si-Wu-Tang on breast cancer cells reveals phytoestrogenic activity. BMC complementary and Alternative Medicine, 13, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. T., Hsiao, C. H., Tzang, B. S., & Hsu, T. C. (2019). In vitro and in vivo effects of traditional Chinese medicine formula T33 in human breast cancer cells. BMC complementary and Alternative Medicine, 19, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Luna, L., Simirgiotis, M. J., Lima, B., Bórquez, J., Feresin, G. E., & Tapia, A. (2018). UHPLC-MS Metabolome Fingerprinting: The Isolation of Main Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of the Andean Species Tetraglochin ameghinoi (Speg.) Speg. Molecules, 23(4), 793. [CrossRef]

- Madaleno, I. M., & Delatorre-Herrera, J. (2013). Medicina popular de Iquique, Tarapacá. Idesia (Arica), 31(1), 67-78. [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, M. A. R., Tolaema, A., Chaikhemarat, P., & Rawdkuen, S. (2023). Antioxidant and anti-cytotoxicity effect of phenolic extracts from Psidium guajava Linn. leaves by novel assisted extraction techniques. Foods, 12(12), 2336. [CrossRef]

- Monagas, M., Brendler, T., Brinckmann, J., Dentali, S., Gafner, S., Giancaspro, G., ... & Marles, R. (2022). Understanding plant to extract ratios in botanical extracts. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 13, 981978. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V., Taine, E. G., Meng, D., Cui, T., & Tan, W. (2024). Chlorogenic Acid: A Systematic Review on the Biological Functions, Mechanistic Actions, and Therapeutic Potentials. Nutrients, 16(7), 924. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, J. E., Piñeiro, M., Martinez-Peinado, N., Barrera, P., Sosa, M., Bastida, J., Alonso-Padilla, J., & Feresin, G. E. (2023). Candimine from Hippeastrum escoipense (Amaryllidaceae): Anti-Trypanosoma cruzi activity and synergistic effect with benznidazole. Phytomedicine: international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 114, 154788. [CrossRef]

- Paschoalinotto, B. H., Dias, M. I., Pinela, J., Pires, T. C., Alves, M. J., Mocan, A., ... & Ferreira, I. C. (2021). Phytochemical characterization and evaluation of bioactive properties of tisanes prepared from promising medicinal and aromatic plants. Foods, 10(2), 475. [CrossRef]

- Pasqualetti, V., Locato, V., Fanali, C., Mulinacci, N., Cimini, S., Morgia, A. M., ... & De Gara, L. (2021). Comparison between in vitro chemical and ex vivo biological assays to evaluate antioxidant capacity of botanical extracts. Antioxidants, 10(7), 1136. [CrossRef]

- Persia, F. A., Rinaldini, E., Carrión, A., Hapon, M. B., & Gamarra-Luques, C. (2017). Evaluation of cytotoxic and antitumoral properties of Tessaria absinthioides (Hook & Arn) DC," pájaro bobo", aqueous extract. MEDICINA (Buenos Aires), 77(4), 283-290.

- Persia, F. A., Troncoso, M. E., Rinaldini, E., Simirgiotis, M., Tapia, A., Bórquez, J., ... & Gamarra-Luques, C. (2020). UHPLC–Q/Orbitrap/MS/MS fingerprinting and antitumoral effects of Prosopis strombulifera (LAM.) BENTH. aqueous extract on allograft colorectal and melanoma cancer models. Heliyon, 6(2). [CrossRef]

- Qi, W., Qi, W., Xiong, D., & Long, M. (2022). Quercetin: its antioxidant mechanism, antibacterial properties and potential application in prevention and control of toxipathy. Molecules, 27(19), 6545. [CrossRef]

- Quesada, I., de Paola, M., Alvarez, M. S., Hapon, M. B., Gamarra-Luques, C., & Castro, C. (2021). Antioxidant and anti-atherogenic properties of prosopis strombulifera and Tessaria absinthioides aqueous extracts: Modulation of NADPH oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species. Frontiers in Physiology, 12, 662833. [CrossRef]

- Rey, M., Kruse, M. S., Gómez, J., Simirgiotis, M. J., Tapia, A., & Coirini, H. (2023). Ultra-High-Resolution Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Electrospray Ionization Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Tessaria absinthioides (Hook. & Arn.) DC.(Asteraceae) and Antioxidant and Hypocholesterolemic Properties. Antioxidants, 13(1), 50.

- Rey, M., Kruse, M. S., Magrini-Huamán, R. N., Gómez, J., Simirgiotis, M. J., Tapia, A., ... & Coirini, H. (2021). Tessaria absinthioides (Hook. & arn.) D.C. (asteraceae) decoction improves the hypercholesterolemia and alters the expression of lxrs in rat liver and hypothalamus. Metabolites, 11(9), 579. [CrossRef]

- Si Said, Z. B. O., Arkoub-Djermoune, L., Bouriche, S., Brahmi, F., & Boulekbache-Makhlouf, L. (2024). Supplementation species effect on the phenolic content and biological bioactivities of the decocted green tea. The North African Journal of Food and Nutrition Research, 8(17), 202-215. [CrossRef]

- Sochorova, L., Prusova, B., Jurikova, T., Mlcek, J., Adamkova, A., Baron, M., & Sochor, J. (2020). The study of antioxidant components in grape seeds. Molecules, 25(16), 3736. [CrossRef]

- Sosa-Lochedino, A., Hapon, M. B., & Gamarra-Luques, C. (2022). A systematic review about the contribution of the genus Tessaria (Asteraceae) to cancer study and treatment. Uniciencia, 36(1), 467-483. [CrossRef]

- Sosa-Lochedino AL, Persia A, Gómez L, Hapon MB, Gamarra-Luques C. (2019). Effects of Tessaria absinthioides aqueous extract in murine melanoma. XXXVII Reunión Anual de la Sociedad de Biología de Cuyo: pp 55. https://sbcuyo.org.ar/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Libro-de-resumenes-2019.pdf.

- Soto VC, Caselles CA, Silva MF & Galmarini CR. (2018). Onion hybrid seed production: Relation with nectar composition and flower traits. J Econ Entomol 111:1023-1029. [CrossRef]

- Stabrauskiene, J., Kopustinskiene, D. M., Lazauskas, R., & Bernatoniene, J. (2022). Naringin and naringenin: Their mechanisms of action and the potential anticancer activities. Biomedicines, 10(7), 1686. [CrossRef]

- Tajner-Czopek, A., Gertchen, M., Rytel, E., Kita, A., Kucharska, A. Z., & Sokół-Łętowska, A. (2020). Study of antioxidant activity of some medicinal plants having high content of caffeic acid derivatives. Antioxidants, 9(5), 412. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Carro, R., Isla, M. I., Thomas-Valdes, S., Jimenez-Aspee, F., Schmeda-Hirschmann, G., & Alberto, M. R. (2017). Inhibition of pro-inflammatory enzymes by medicinal plants from the Argentinean highlands (Puna). Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 205, 57-68. [CrossRef]

- Tošović, J., & Bren, U. (2020). Antioxidative action of ellagic acid—A kinetic DFT study. Antioxidants, 9(7), 587. [CrossRef]

- Vigliante, I., Mannino, G., & Maffei, M. E. (2019). OxiCyan®, a phytocomplex of bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) and spirulina (Spirulina platensis), exerts both direct antioxidant activity and modulation of ARE/Nrf2 pathway in HepG2 cells. Journal of Functional Foods, 61, 103508. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Le, T., Wang, W., Yu, L., Yang, L., & Jiang, H. (2023). Effects of key components on the antioxidant activity of black tea. Foods, 12(16), 3134. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., & Li, P. P. (2009). Evaluation of estrogenic potential of Shu-Gan-Liang-Xue Decoction by dual-luciferase reporter based bioluminescent measurements in vitro. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 126(2), 345-349. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).