1. Introduction

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and prostatitis are highly prevalent urological disorders that mainly affect men over the age of 40. Their incidence progressively increases with ageing, reaching an estimated prevalence of approximately 43% among individuals aged 60-69 and up to 80% in men older than 70 years, representing one of the leading causes of morbidity in elderly males [

1].

BPH is characterised by a non-malignant proliferation of the prostatic epithelium and stroma, which leads to lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), decreased urinary flow, and a deterioration in quality of life [

2]. It is considered a multifactorial disease in which hormonal, inflammatory, and oxidative factors converge. Chronic inflammation and persistent oxidative stress contribute to the hyperplastic microenvironment through activation of pro-inflammatory pathways such as NF-κB, which promote cellular proliferation and resistance to apoptosis [

2,

3].

Metabolic comorbidities such as obesity and insulin resistance exacerbate prostatic inflammation through cytokines including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, thereby enhancing oxidative damage and accelerating prostatic growth [

4]. These mechanisms suggest that simultaneous modulation of the redox and inflammatory axes could represent a more effective therapeutic strategy than treatments focused solely on androgen inhibition.

Conventional drugs such as α-adrenergic blockers and 5α-reductase inhibitors (finasteride and dutasteride) provide symptomatic relief but fail to correct the underlying redox-inflammatory imbalance. Moreover, they are associated with metabolic and sexual adverse effects upon long-term use. In this context, natural products represent a valuable source of bioactive compounds with therapeutic potential against BPH and prostatitis due to their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and androgen receptor-modulating properties [

5].

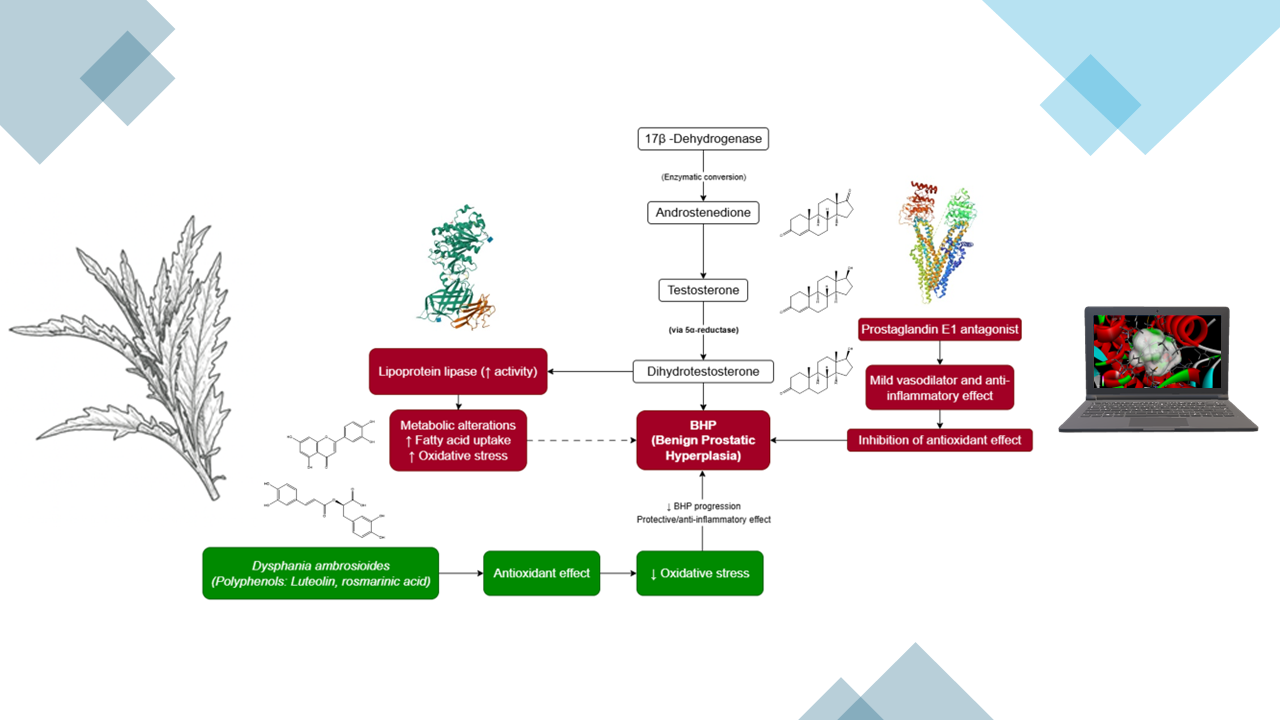

Furthermore, several studies have described the wide distribution and phytochemical richness of

D. ambrosioides, including monoterpenes and bioactive flavonoids with notable anti-inflammatory and antioxidant potential [

6,

7]. Given the increasing evidence linking oxidative stress to BPH progression [

2], the present study proposes a multitarget

in silico approach to identify

D. ambrosioides metabolites exhibiting affinity for the main prostatic targets (AR, 5AR2, COX-2, NLRP3, and α1A) (see

Figure 1).

Several flavonoids, such as quercetin, luteolin, and rutin, as well as phenolic acids including rosmarinic acid, have been reported to inhibit COX-2, reduce the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and modulate androgen receptor (AR) signalling, showing activity comparable to classical pharmacological agents [

8]. However, these compounds have not been evaluated in an integrated manner within the context of

D. ambrosioides nor against multiple targets associated with BPH. This computational approach enables the identification of natural candidates with pharmacological potential comparable to reference drugs, supporting their future validation through enzymatic, cellular, and

in vivo studies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Comparative Quantitative Analysis

A systematic search was conducted in PubMed, ScienceDirect, Wiley Online Library, and Google Scholar databases for the period 2005-2025, using the keywords: “Chenopodium ambrosioides AND antioxidant” and “Dysphania ambrosioides AND antioxidant”.

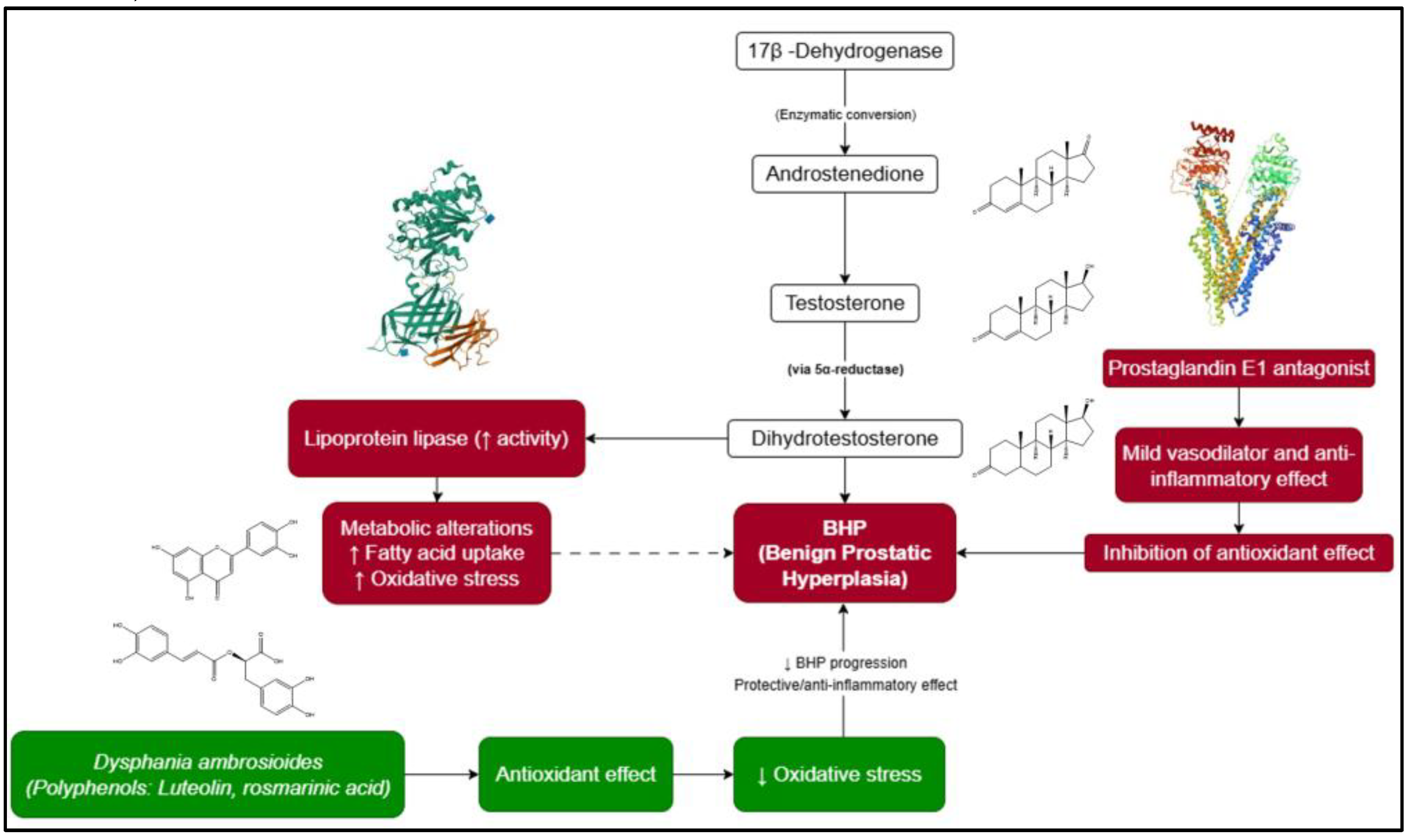

From 106 identified articles, 35 met the inclusion criteria, reporting IC₅₀ (µg/mL) values obtained through the DPPH assay. Data were extracted, normalised, and statistically analysed using Python (v3.12.3). The arithmetic mean, standard error of the mean (SEM), and sample size (n) were calculated, yielding a global average IC₅₀ value of 398.410 ± 81.810 µg/mL (n = 35).

Among these studies, 14 reported IC₅₀ values below the global mean, indicating higher antioxidant potency. The corresponding extracts were selected for metabolite analysis (

Figure 2). Given the heterogeneity in experimental methods across studies (solvent type, plant part, incubation time, and assay conditions), a descriptive quantitative approach was adopted. This enabled the identification of general trends and prioritisation of extracts with higher antioxidant capacity for subsequent

in silico analysis.

2.2. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

IC₅₀ values were organised in Microsoft Excel 365 and processed in Python (v3.12.3) using the libraries NumPy, pandas, matplotlib, and seaborn. Global averages and standard error intervals were computed. Comparative graphs and heatmaps were generated to visualise inter-study variability and highlight the most active extracts.

Due to the methodological heterogeneity among reports (different extraction techniques, concentrations, and experimental conditions), inferential statistical tests such as ANOVA or meta-regression were not applied. Instead, a descriptive comparative approach was employed to identify extracts of greater interest. All statistical analyses and visualisations were reproducible through scripts specifically developed for this study, which are provided as supplementary material.

2.3. Retrieval and Standardisation of Chemical Structures

Metabolites associated with extracts presenting IC₅₀ values below the global mean were retrieved from the PubChem database using the PubChemPy library (v1.0.5). For each compound, the compound identification number (CID), IUPAC name, molecular formula, and canonical SMILES representation were obtained.

The structures were validated and converted into a standardised format using RDKit (v2024.03.6). Molecular fingerprints (Morgan fingerprints, radius = 2, 208 bits) were generated to evaluate structural similarities through the Tanimoto index (threshold ≥ 0.85). Results were integrated into a standardised chemical database, which served as the input for the prioritisation and molecular docking analyses.

2.4. In Silico Prioritisation of Metabolites

In OSIRIS Property Explorer, the Drug-Score index was extracted, and toxicological alerts were normalized (green = 1, yellow = 0.5, red = 0). The OSIRIS score was calculated as the mean of the Drug-Score and toxicity index. In PASS Online, probabilities of activity (Pa) related to pharmacological functions relevant to BPH (Dihydrotestosterone 17β-dehydrogenase inhibition, prostaglandin E1 antagonism, and lipoprotein lipase inhibition) were obtained. The PASS score corresponded to the mean of these probabilities. In ProTox 3.0, hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity predictions were considered; molecules classified as “Inactive” were interpreted as safe (value = 1), whereas “Active” results were adjusted as (1 - probability). The ProTox score was defined as the average of these indicators.

Finally, a Composite Score was calculated as the simple mean of the three normalised values. The selection threshold was set at the global average of the Composite Score (0.221 ± 0.016; n = 30). Compounds with values above this threshold were considered priorities for molecular docking.

2.2. Ligand Preparation

Selected metabolites and reference drugs (MCC950, dexamethasone, finasteride, celecoxib, and tamsulosin) were downloaded from PubChem (

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) in “.sdf” format (accessed on 13 September 2025). Structures were processed in Avogadro (

https://avogadro.cc/) [

11], where charge redundancies were removed, protonation was adjusted to physiological pH (7.4), and energy minimisation was performed using the MMFF94s force field. Ligands were then exported in “.mol2” format, ensuring energetically stable conformations compatible with molecular docking.

2.3. Target Protein Selection and Preparation

Five key proteins involved in the pathophysiology of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and prostatic inflammation were selected: the androgen receptor (AR, PDB: 2AM9) corresponding to the ligand-binding domain complexed with Dihydrotestosterone; steroid 5α-reductase type 2 (5AR2, PDB: 7BW1), a human structure crystallised in complex with finasteride and NADPH; cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2, PDB: 3LN1) complexed with celecoxib; the NLRP3 complex (PDB: 7ALV), representing the NACHT domain bound to a selective inhibitor; and the α1A-adrenergic receptor (α1A, PDB: 7YMJ) complexed with tamsulosin. The 3D structures were downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (

https://www.rcsb.org/) using the “Fetch by ID” tool in UCSF Chimera v1.18 (

https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/). Native ligands, water molecules, and non-essential ions were removed, preserving only polypeptide chains relevant to the active site. Hydrogens were added at physiological pH (7.4), and the processed proteins were saved in “.pdb” format (e.g., “7YMJ_cleaned.pdb”) for use in molecular docking analyses.

2.4. Molecular Docking Using CB-Dock2

Molecular docking was performed using the CB-Dock2 server (

https://cadd.labshare.cn/cb-dock2/php/index.php) [

12], which automatically detects binding cavities and applies AutoDock Vina to estimate binding energies (kcal/mol). Initially, redocking of reference ligands (Dihydrotestosterone, finasteride, celecoxib, MCC950, and tamsulosin) was performed to validate the protocol. The cavity with the lowest binding energy was defined as the canonical binding site, and its coordinates (x, y, z) and box dimensions were recorded. These parameters were uniformly applied for docking of all natural compounds, ensuring comparability and consistency of results. The protocol was validated through ligand superposition in UCSF Chimera using the MatchMaker tool, achieving RMSD values < 2.0 Å, which confirmed the model’s precision. The results (Vina scores, coordinates, and poses) were archived for subsequent structural analysis.

2.5. Interaction Analysis

Ligand-protein interactions were analysed using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer 2021 v21.1.0.20298 (

https://www.3ds.com/products/biovia/discovery-studio), Interaction types were classified according to their relevance following the hierarchy described in the BIOVIA DS Visualizer 2021 manual: hydrogen bonds > π-π stacking > π-cation/π-anion > π-sulphur > hydrophobic (Alkyl/π-Alkyl) > van der Waals. Results were compiled into a comparative table summarising the binding energies (Vina scores, kcal/mol) for each ligand across the five target proteins-AR (2AM9), 5AR2 (7BW1), COX-2 (3LN1), NLRP3 (7ALV), and α1A (7YMJ). Values were organised by compound and binding cavity (CurPocket C1), highlighting both reference ligands (Dihydrotestosterone, finasteride, celecoxib, MCC950, and tamsulosin) and natural metabolites (rosmarinic acid and luteolin). This representation enabled comparison of relative affinities and multitarget profiles while corroborating the consistency of the docking protocol.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All quantitative data were processed and analysed using Python (v3.12.3) (

https://www.python.org/), For antioxidant activity (DPPH assay, IC₅₀ values in µg/mL), descriptive statistics were applied to estimate central tendency and variability (mean ± SEM). Visualisations were generated with matplotlib and seaborn libraries, including comparative graphs and heatmaps to illustrate variability among studies and highlight the most active extracts.

For pharmacoinformatic evaluation, values generated by OSIRIS Property Explorer, PASS Online, and ProTox 3.0 were analysed following the same statistical approach described in section 2.4, limited to calculations of central tendency and dispersion (mean ± SEM; n). This procedure allowed global distribution representation of scores without repeating methodological descriptions from the prioritisation stage.

3. Results

3.1. Comparative Quantitative Analysis of Antioxidant Activity

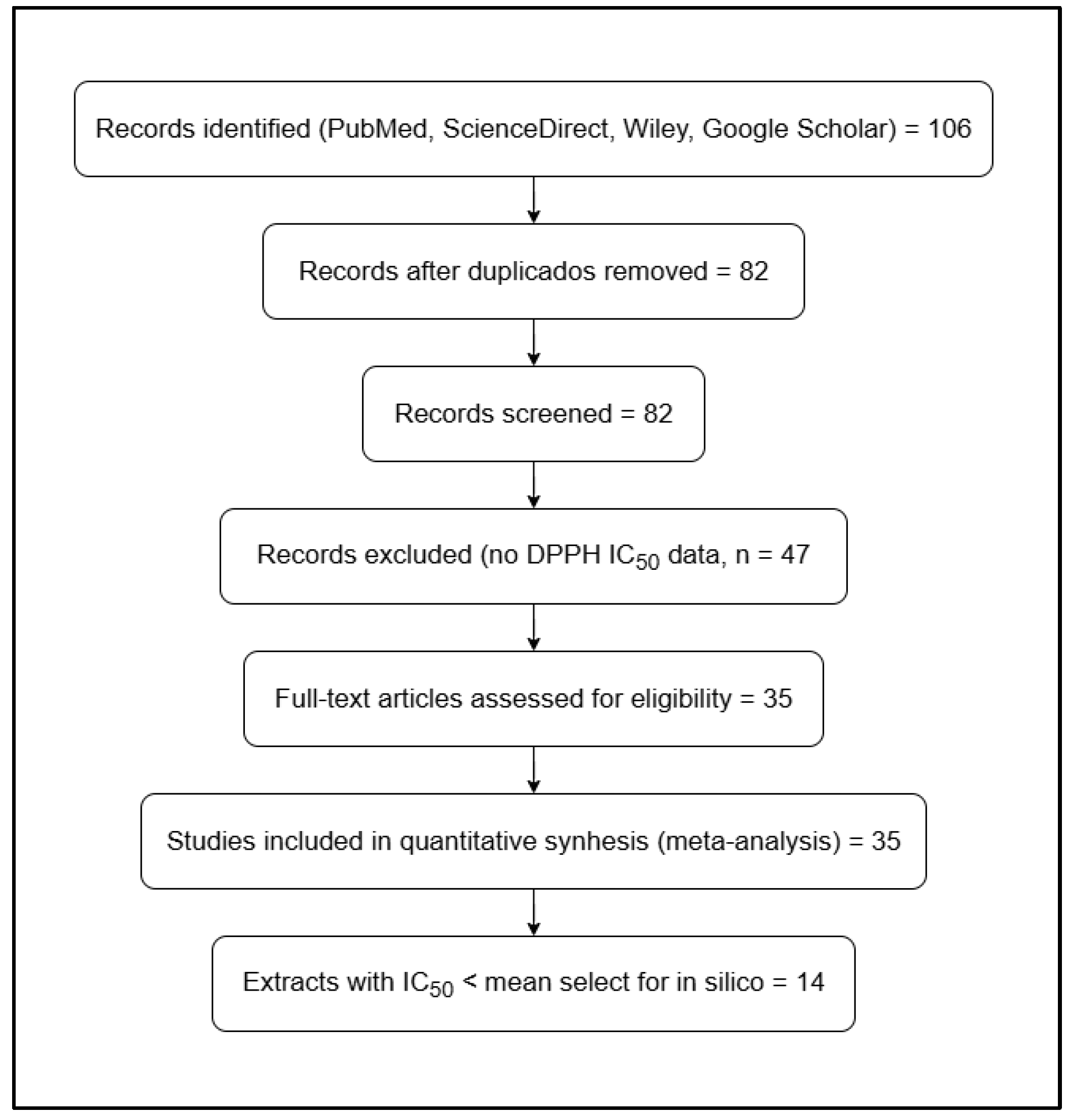

From the 14 selected articles, a global mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) IC₅₀ value of 398.410 ± 81.810 µg/mL (n = 35) was calculated for the DPPH assay, representing the average antioxidant activity of D. ambrosioides between 2013 and 2025.

The graphical analysis revealed marked variability among studies (

Figure 3). Extracts reported by Barros et al. (2013) [

13], Zohra et al. (2019) [

14], Ogunleye et al. (2020) [

15], Ouadja et al. (2021) [

16], Ez-Zriouli et al. (2023) [

17], Annaz et al. (2023) [

18], Drioua et al. (2024) [

19], Sekede et al. (2024) [

20], Ngolo et al. (2025) [

21], and Everton et al. (2025) [

22] exhibited IC₅₀ values below the global mean, indicating higher antioxidant potency. In contrast, the studies of Maningkas et al. (2019) [

23], Pandiangan et al. (2020) [

24], and Kandsi et al. (2021) [

25] and Kandsi et al. (2022) [

26] reported higher IC₅₀ values, reflecting lower antioxidant capacity, which was attributed to differences in extraction methods, solvent type, and the geographical origin of plant material.

From this comparative analysis, 41 metabolites were identified as being associated with the most active extracts (IC₅₀ < 398.410 µg/mL). Among them, notable representatives included monoterpenes ((+)-4-carene, isopinocampheol, ascaridole), unsaturated fatty acids ((E)-palmitoleic, linolenic, and linoleic acids), phenolic compounds (rosmarinic acid, syringic acid, phenol), and flavonoids (kaempferol, quercetin, luteolin, myricetin, and rutin). Of these, 30 metabolites (≈73.17%) were successfully standardised using PubChemPy and RDKit, yielding a harmonised database for subsequent in silico prioritisation and molecular docking analyses.

3.2. Pharmacoinformatic Evaluation and Prioritisation of Metabolites

The pharmacoinformatic assessment conducted using OSIRIS Property Explorer, PASS Online, and ProTox 3.0 enabled the calculation of an average Composite Score of 0.220 ± 0.016 (n = 30), which served as the selection threshold. Metabolites with values exceeding this threshold were considered priority candidates for molecular docking analysis.

Among the compounds showing the best overall performance, luteolin and rosmarinic acid were particularly noteworthy, as they combined the following characteristics:

High probability of biological activity (Pa > 0.6 in PASS Online),

Absence of significant toxicological alerts (green classification in OSIRIS), and

Favourable hepatic and renal safety predictions in ProTox 3.0.

These metabolites exhibited multitarget and pharmacologically safe profiles, thereby justifying their selection for docking experiments against the androgen receptor (AR), steroid 5α-reductase type 2 (5AR2), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), NLRP3 inflammasome, and α1A-adrenergic receptor.

To facilitate interpretation of the prioritisation results,

Table 1 presents the sixteen metabolites with the highest Composite Score values, calculated across the OSIRIS Property Explorer, PASS Online, and ProTox 3.0 platforms. Compounds with scores above the global mean (0.220 ± 0.016; n = 30) were considered of greater pharmacological relevance and were selected for molecular docking analyses.

3.3. Multitarget Molecular Docking

The molecular docking analysis performed using CB-Dock2 confirmed competitive binding affinities between the natural metabolites of

D. ambrosioides and the reference drugs employed to validate the protocol (

Table 2). Binding energies ranged from -13.4 to -8.1 kcal/mol across all evaluated proteins. As expected, the reference ligands displayed the lowest energy values - Dihydrotestosterone (-10.9), finasteride (-13.4), celecoxib (-11.4), MCC950 (-9.0), and tamsulosin (-7.3 kcal/mol) - thereby confirming the validity of the model and the precision of the canonical binding site (CurPocket C1).

Among the natural metabolites, rosmarinic acid and luteolin exhibited binding affinities ranging from -9.5 to -7.7 kcal/mol, values comparable to those of the pharmacological controls. Both compounds demonstrated clear multitarget binding profiles across the five target proteins: androgen receptor (2AM9), steroid 5α-reductase type 2 (7BW1), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2, 3LN1), NLRP3 inflammasome (7ALV), and α1A-adrenergic receptor (7YMJ). Notably, rosmarinic acid displayed the strongest affinity within the androgenic axis (AR/5AR2), whereas luteolin exhibited a more versatile binding profile, interacting effectively with both inflammatory (COX-2, NLRP3) and adrenergic (α1A) targets.

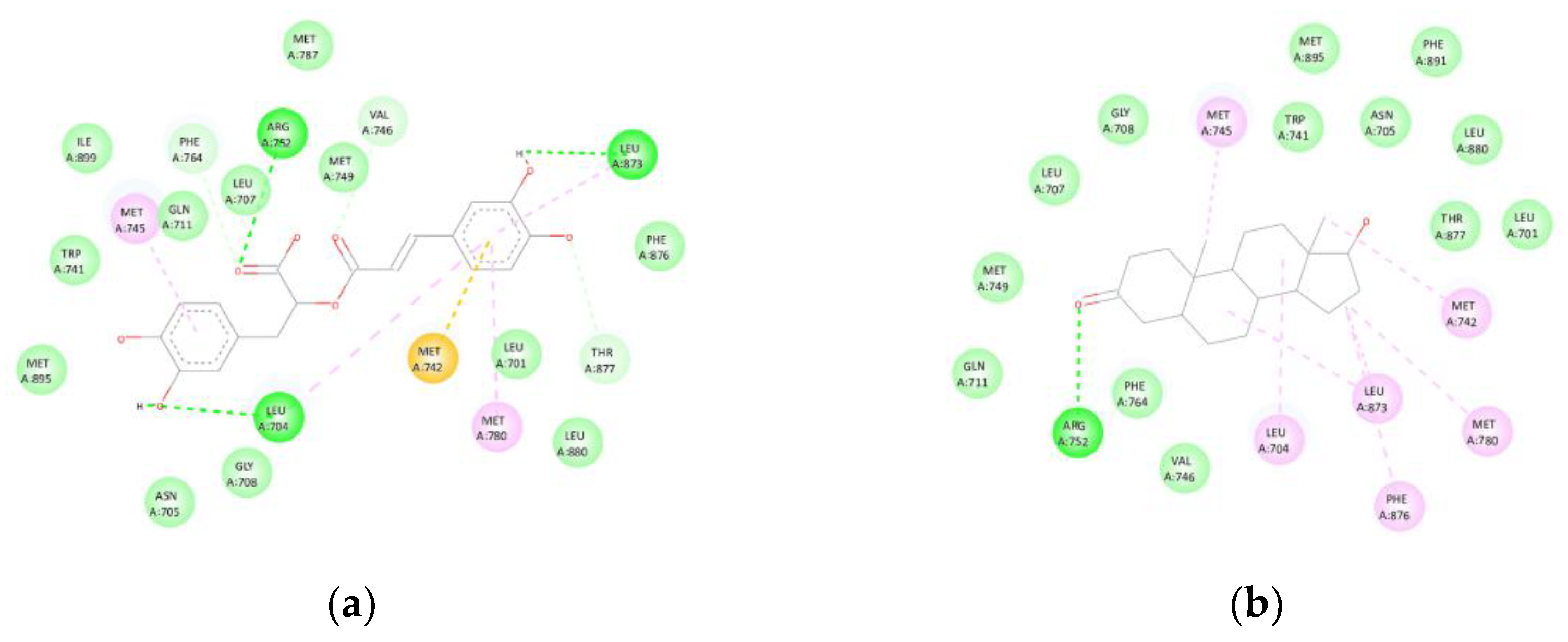

3.3.1. Androgen Receptor (AR, PDB: 2AM9)

Rosmarinic acid exhibited a binding affinity of -9.1 kcal/mol towards the androgen receptor (2AM9). The compound formed hydrogen bonds with LEU704, ARG752, and LEU873, as well as hydrophobic contacts (Alkyl/π-Alkyl) with LEU704, MET745, and MET780, and a π-sulphur interaction with MET742. Additionally, van der Waals contacts were observed with LEU701, ASN705, LEU707, GLY708, GLN711, TRP741, MET749, MET787, PHE876, LEU880, MET895, and ILE899, effectively reproducing the binding mode of Dihydrotestosterone (control, -10.9 kcal/mol) (

Figure 4). The superposition with the co-crystallised ligand revealed an RMSD value below 2 Å, confirming accurate spatial alignment within the canonical binding pocket.

3.3.2. Steroid 5α-Reductase Type 2 (5AR2, PDB: 7BW1):

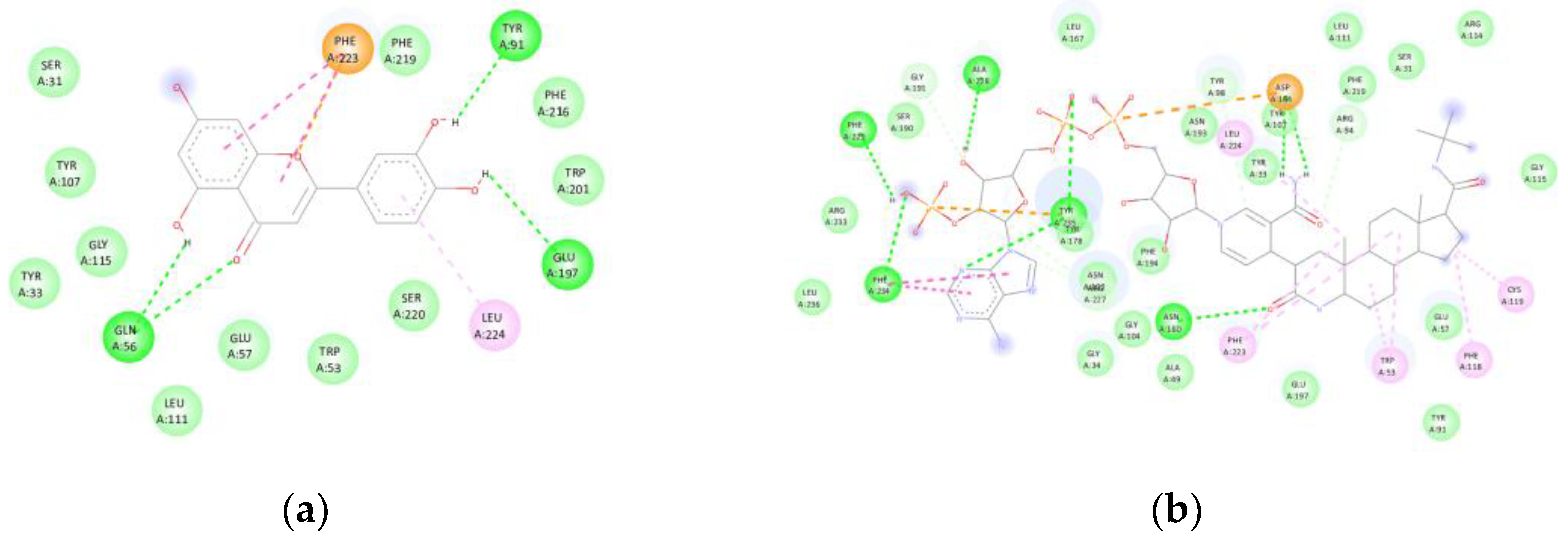

Luteolin exhibited a binding affinity of -9.4 kcal/mol with steroid 5α-reductase type 2 (7BW1). The compound formed hydrogen bonds with GLN56, TYR91, and GLU197, in addition to hydrophobic contacts with LEU224. Van der Waals interactions were observed with SER031, TYR033, TRP053, GLU057, TYR107, LEU111, GLY115, TRP201, PHE216, PHE219, and SER220, while a π-π stacking interaction with PHE223 reinforced its anchoring within the catalytic site of finasteride (-13.4 kcal/mol) (

Figure 5). The superposition with the co-crystallised ligand revealed an RMSD value below 2 Å, confirming consistent alignment within the canonical binding pocket.

3.3.3. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2, PDB: 3LN1)

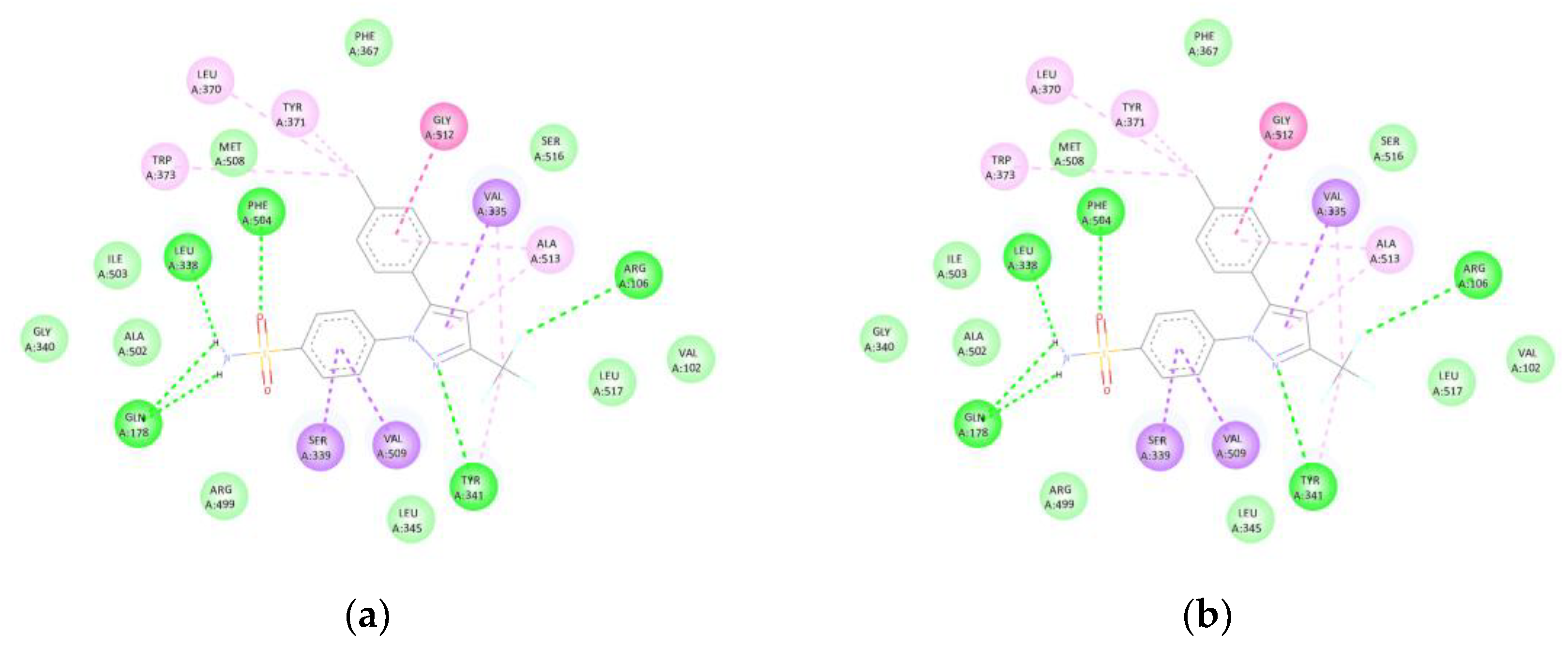

Luteolin (-9.5 kcal/mol) formed hydrogen bonds with TYR341, ILE503, and SER516, as well as hydrophobic interactions with VAL335, LEU338, and ALA502. An amide-π stacked interaction was also observed with GLY512, reproducing the binding mode of celecoxib (control, -11.4 kcal/mol) within the catalytic site of COX-2 (

Figure 6). The superposition with the co-crystallised ligand showed an RMSD < 2 Å, confirming precise spatial alignment within the active site.

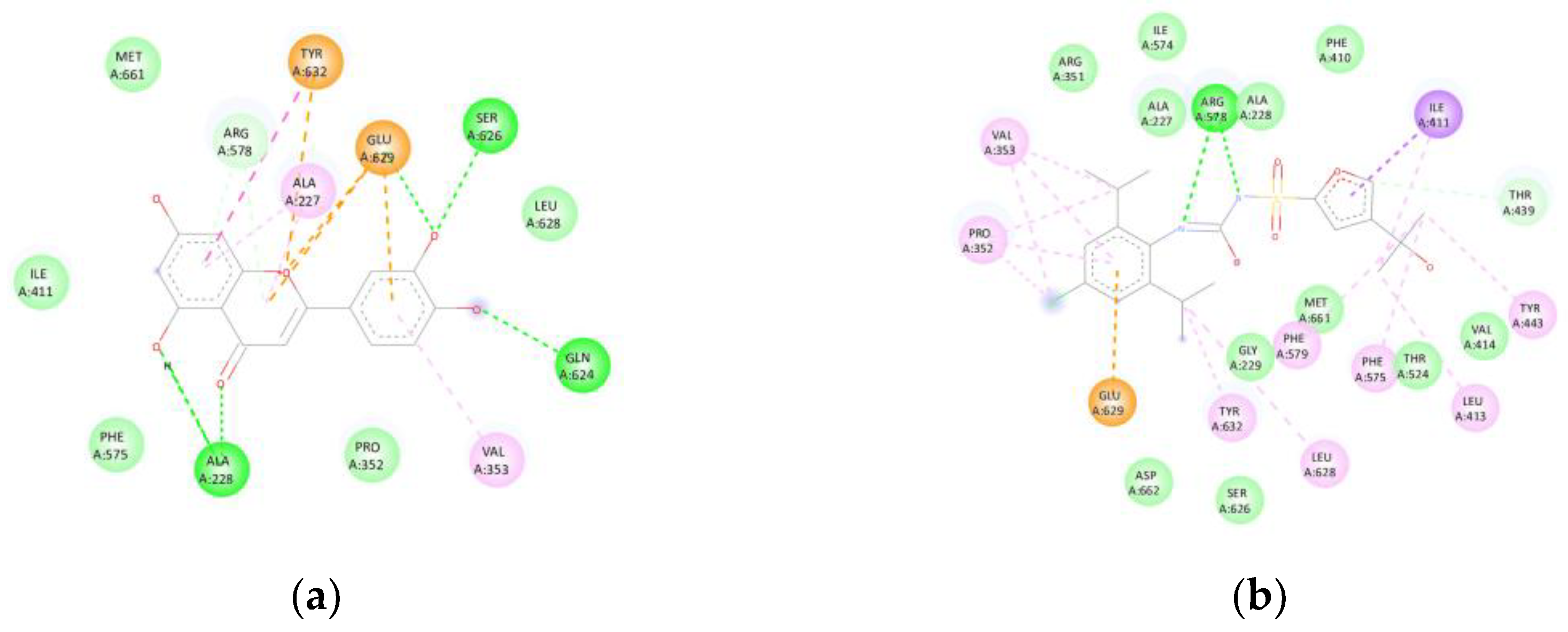

3.3.4. NLRP3 (PDB: 7ALV)

Luteolin exhibited a binding affinity of -8.7 kcal/mol with NLRP3 (7ALV). The compound formed hydrogen bonds with ALA228, GLN624, and SER626, as well as π-cation/π-anion interactions involving GLU629 and TYR632, and a π-π stacking interaction with TYR632. This binding pattern closely resembled that of the selective inhibitor MCC950 (-9.0 kcal/mol), suggesting potential inflammasome inhibition (

Figure 7). The superposition with the co-crystallised ligand displayed an RMSD < 2 Å, confirming accurate alignment within the canonical binding pocket.

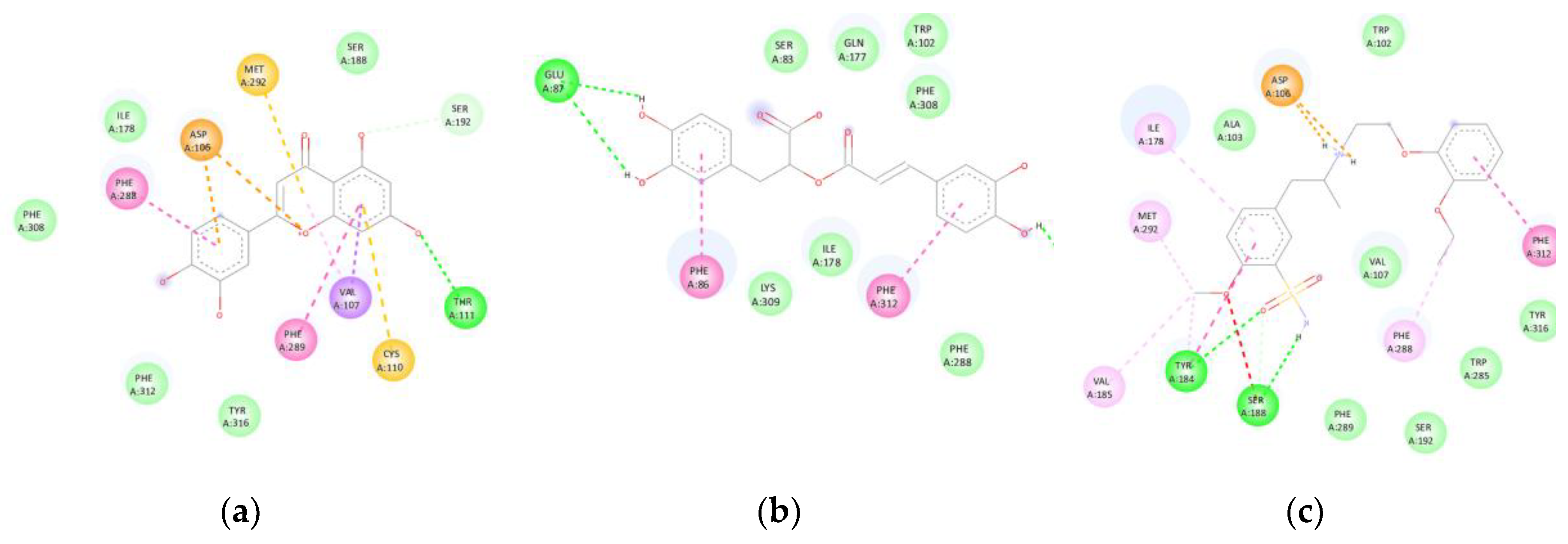

3.3.5. α1.A-Adrenergic Receptor (PDB: 7YMJ):

Luteolin and rosmarinic acid exhibited binding affinities of -7.7 kcal/mol, slightly higher than that of tamsulosin (-7.3 kcal/mol). Luteolin formed hydrogen bonds with THR111, π-anion interactions with ASP106, and π-π stacking interactions with PHE288 and PHE289, in addition to π-sulphur interactions with CYS110 and MET292. Rosmarinic acid, in turn, established hydrogen bonds with GLU87 and ASP106, π-π stacking interactions with PHE086 and PHE312, and van der Waals contacts with SER083, TRP102, GLN177, ILE178, PHE288, PHE308, LYS309, TRP313, and TYR316.

Both compounds partially reproduced the binding mode of tamsulosin, suggesting their potential role as smooth muscle relaxants in the prostate (

Figure 8). The superposition with the co-crystallised ligand revealed an RMSD < 2 Å, confirming accurate alignment within the active site.

3.4. Global Comparison of Binding Affinities

The integrated comparison of binding affinities demonstrated that the two major metabolites of D. ambrosioides exhibit consistent and competitive binding patterns relative to the pharmacological controls. Rosmarinic acid showed the highest affinity within the androgenic axis (AR/5AR2), whereas luteolin displayed greater versatility towards inflammatory (COX-2, NLRP3) and adrenergic (α1A) targets. These findings confirm that D. ambrosioides represents a natural source of multitarget compounds with therapeutic potential against benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and prostatitis, integrating antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and androgen receptor-modulating properties.

4. Discussion

The results obtained demonstrate that the metabolites luteolin and rosmarinic acid, identified in

D. ambrosioides [

7], exhibit high affinity towards the main molecular targets involved in the pathophysiology of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and prostatitis. These molecules displayed docking energies comparable to those of reference drugs and reproduced key interactions within the active sites of the evaluated proteins, supporting their multitarget and synergistic potential.

Rosmarinic acid stood out as a dual modulator of the androgen receptor (AR) and steroid 5α-reductase type 2 (5AR2), two essential targets in the prostatic hormonal axis. Its interactions with conserved residues (LEU704, ARG752, and LEU873 in AR; GLU197 in 5AR2) suggest that it may interfere with androgen binding or inhibit the conversion of Dihydrotestosterone to dihydroDihydrotestosterone (DHT), thereby reducing proliferative stimulation of the prostatic epithelium. This behaviour partially resembles the mechanism of action of finasteride, whose crystal structure with SRD5A2 reveals the formation of an NADP-dihydrofinasteride adduct within a closed catalytic cavity [

27]. Therefore, the interaction of rosmarinic acid with GLU197 and catalytic domains may partially mimic the occupancy of the active site described for finasteride, but with a lower predicted toxicity risk according to ProTox 3.0 estimations.

Conversely, luteolin exhibited remarkable pharmacodynamic versatility by interacting with proteins associated with both prostatic inflammation (COX-2 and NLRP3) and smooth muscle tone (α₁A-adrenergic receptor). Within COX-2, its stable anchoring in the catalytic site (contacts with TYR341, ILE503, and SER516) partially reproduced the binding mode of celecoxib, suggesting potential competitive inhibition of proinflammatory prostaglandin biosynthesis. In the NACHT domain of NLRP3, the π-anion and π-cation interactions with GLU629 and TYR632 imply a possible blockade of inflammasome oligomerisation, a key step in the activation of IL-1β and TNF-α.

These findings are consistent with those reported by Mahdiani et al. (2022), who demonstrated that luteolin coordinately inhibits the NF-κB, ERK/MAPK, and JNK pathways, thereby reducing the expression of iNOS, COX-2, and proinflammatory cytokines [

28]. In addition, its antioxidant capacity, mediated by the activation of Nrf2 and the upregulation of endogenous enzymes (CAT, SOD, GPx), reinforces its protective role against oxidative stress. This dual anti-inflammatory and antioxidant action aligns with the interaction patterns identified in COX-2 and NLRP3 in the present study.

Our findings support the hypothesis that the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory metabolites of

D. ambrosioides act on multiple therapeutic targets involved in BPH. The ability of these compounds to modulate simultaneously the androgenic axis (AR/5AR2), the inflammatory axis (COX-2/NLRP3), and the smooth muscle tone (α₁A) suggests a combined or synergistic mechanism that could enhance therapeutic efficacy while reducing adverse effects compared with single-target drugs. This observation agrees with experimental models showing that flavonoid-rich extracts, such as purple corn, downregulate AR and Srd5a2 expression and inhibit NF-κB and Nrf2 activation in Dihydrotestosterone-induced BPH in rats [

29].

The in silico prioritisation approach (OSIRIS-PASS-ProTox) enabled the selection of metabolites with a favourable balance between pharmacological potential, bioavailability, and safety. In particular, the prioritised compounds showed no significant mutagenic or hepatotoxic alerts, reinforcing their feasibility as multitarget phytopharmaceutical prototypes.

Furthermore, the results strengthen the recognised link between oxidative stress and prostatic inflammation, two physiopathological processes that are closely interconnected. The reduction of oxidative damage by these metabolites could contribute to attenuating NLRP3 activation and the production of proinflammatory cytokines, thereby disrupting the redox-inflammatory pathogenic loop characteristic of BPH [

29].

In this context, the integration of comparative antioxidant activity analysis (DPPH IC₅₀) with pharmacoinformatic prioritisation and multitarget molecular docking represents a rational and reproducible strategy for identifying bioactive natural candidates. This combined approach optimises the selection of metabolites with complementary mechanisms of action, reducing both cost and preclinical development time. Overall, this study constitutes an integrative and reproducible framework combining three analytical levels: (1) a quantitative meta-analysis of antioxidant capacity; (2) a multicriteria pharmacoinformatic prioritisation; and (3) a multitarget molecular docking validated by redocking. This methodological architecture represents an original contribution to the study of natural products applied to urological disorders and can serve as a model for the rational identification of bioactive compounds in other species with therapeutic potential [

7]

Finally, although this study provides robust computational evidence, it remains necessary to experimentally validate these findings through enzymatic assays, cell-based studies, and in vivo models to confirm the effective modulation of the proposed targets. Moreover, pharmacokinetic evaluation and the potential synergy between the identified metabolites will represent crucial steps towards their therapeutic application against BPH and prostatitis, including in vitro assays on 5AR2 and Dihydrotestosterone-induced BPH murine models.

5. Conclusions

From a translational perspective, the results of this study identify luteolin and rosmarinic acid as the most promising metabolites of D. ambrosioides for the intervention in benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and prostatitis. These compounds exhibit competitive affinities with reference drugs and reproduce key interactions within the active sites of AR, 5AR2, COX-2, NLRP3, and α1A, suggesting a multitarget mechanism of action. Their combined antioxidant and anti-inflammatory profiles, together with their ability to modulate prostatic smooth muscle tone, support their potential as safe and synergistic natural candidates. Future studies should experimentally validate these findings and further explore their pharmacokinetic properties and formulation strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Supplementary Material S1: Heatmap Polarity Analysis (IC₅₀ ± SEM) - Python 3.12 reproducible notebook for comparative antioxidant analysis of Dysphania ambrosioides extracts (DPPH assay, 2005-2025). The script generates heatmaps and statistical summaries from IC₅₀ data, identifying the most active extracts. Supplementary Material S2: Unique Major Compounds (Clean & Sorted) - Python 3.12 notebook for data cleaning and deduplication of the three main metabolites (Major_compound_1-3) from the meta-analysis dataset. Produces a harmonised list of unique compounds used for downstream analyses. Supplementary Material S3: PubChem SMILES Retrieval (Validated with RDKit) - Notebook for automatic retrieval of PubChem SMILES and structural validation with RDKit, producing the standardised Smiles_compounds.csv used for pharmacoinformatic and docking analyses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.J.-F. and R.A.-V.; Investigation, E.J.-F., T.A.-S., A.A.V.-R., J.J.F.-M., and D.V.L.; Data curation and analysis, T.A.-S. and A.A.V.-R.; Writing-original draft preparation, R.A.-V.; Writing-review and editing, E.J.-F., J.J.F.-M., and R.A.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve humans or animals; all data were obtained from previously published studies and public databases.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its

Supplementary Materials. Additional datasets and code are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the technical support provided by the Faculty of Medicine of the Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos (UAEM). The computational resources used in this work were supported by institutional infrastructure.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Garraway, W.M.; Collins, G.N.; Lee, R.J. High Prevalence of Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy in the Community. Lancet 1991, 338, 469–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltsas, A.; Giannakas, T.; Stavropoulos, M.; Kratiras, Z.; Chrisofos, M. Oxidative Stress in Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Mechanisms, Clinical Relevance and Therapeutic Perspectives. Diseases 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-J.; Wedamulla, N.E.; Kim, S.-H.; Oh, M.; Seo, K.S.; Han, J.S.; Lee, E.J.; Park, Y.H.; Park, Y.J.; Kim, E.-K. Salvia Miltiorrhiza Bunge Ameliorates Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia through Regulation of Oxidative Stress via Nrf-2/HO-1 Activation. J Microbiol Biotechnol 2024, 34, 1059–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sherbiny, M.; El-Shafey, M.; El-din El-Agawy, M.S.; Mohamed, A.S.; Eisa, N.H.; Elsherbiny, N.M. Diacerein Ameliorates Dihydrotestosterone-Induced Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia in Rats: Effect on Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Apoptosis. International Immunopharmacology 2021, 100, 108082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmenko A, V.; Gyaurgiev T, A.; Kuzmenko V, V.; Kuzmenko G, A. [The use of antioxidants in combination therapy of chronic prostatitis]. Urologiia 2024, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavisiony Hewis; Giovanni Daeli; Kenjiro Tanoto; Carlos Carlos; Agnes Sahamastuti A Review of Botany, Phytochemical, and Pharmacological Effects of Dysphania ambrosioides. IJLS 2020, 2. [CrossRef]

- Kandsi, F.; Lafdil, F.Z.; El Hachlafi, N.; Jeddi, M.; Bouslamti, M.; El Fadili, M.; Seddoqi, S.; Gseyra, N. Dysphania ambrosioides (L.) Mosyakin and Clemants: Bridging Traditional Knowledge, Photochemistry, Preclinical Investigations, and Toxicological Validation for Health Benefits. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology 2024, 397, 969–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metri, N.A.; Mandl, A.; Paller, C.J. Harnessing Nature’s Therapeutic Potential: A Review of Natural Products in Prostate Cancer Management. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 2025, 43, 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filimonov, D.A.; Lagunin, A.A.; Gloriozova, T.A.; Rudik, A.V.; Druzhilovskii, D.S.; Pogodin, P.V.; Poroikov, V.V. Prediction of the Biological Activity Spectra of Organic Compounds Using the PASS Online Web Resource. Chemistry of Heterocyclic Compounds 2014, 50, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Eckert, A.O.; Schrey, A.K.; Preissner, R. ProTox-II: A Webserver for the Prediction of Toxicity of Chemicals. Nucleic Acids Research 2018, 46, W257–W263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanwell, M.D.; Curtis, D.E.; Lonie, D.C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Zurek, E.; Hutchison, G.R. Avogadro: An Advanced Semantic Chemical Editor, Visualization, and Analysis Platform. Journal of Cheminformatics 2012, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Grimm, M.; Dai, W.; He, X.; He, C.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y. CB-Dock2: Improved Protein-Ligand Blind Docking by Integrating Cavity Detection, Docking and Homologous Template Fitting. Nucleic Acids Research 2022, 50, W159–W164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, L.; Pereira, E.; Calhelha, R.C.; Dueñas, M.; Carvalho, A.M.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Bioactivity and Chemical Characterization in Hydrophilic and Lipophilic Compounds of Chenopodium ambrosioides L. Journal of Functional Foods 2013, 5, 1732–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohra, T.; Ovais, M.; Khalil, A.T.; Qasim, M.; Ayaz, M.; Shinwari, Z.K. Extraction Optimization, Total Phenolic, Flavonoid Contents, HPLC-DAD Analysis and Diverse Pharmacological Evaluations of Dysphania ambrosioides (L.) Mosyakin & Clemants. Natural Product Research 2019, 33, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogunleye, G.S.; Fagbohun, O.F.; Babalola, O.O. Chenopodium ambrosioides Var. ambrosioides Leaf Extracts Possess Regenerative and Ameliorative Effects against Mercury-Induced Hepatotoxicity and Nephrotoxicity. Industrial Crops and Products 2020, 154, 112723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouadja, B.; Katawa, G.; Toudji, G.A.; Layland, L.; Gbekley, E.H.; Ritter, M.; Anani, K.; Ameyapoh, Y.; Karou, S.D. Anti-Inflammatory, Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities of Chenopodium ambrosioides L. (Chenopodiaceae) Extracts. Journal of Applied Biosciences 2021, 162, 16764–16794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ez-Zriouli, R.; ElYacoubi, H.; Imtara, H.; Mesfioui, A.; ElHessni, A.; Al Kamaly, O.; Zuhair Alshawwa, S.; Nasr, F.A.; Benziane Ouaritini, Z.; Rochdi, A. Chemical Composition, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities and Acute Toxicity of Cedrus atlantica, Chenopodium ambrosioides and Eucalyptus camaldulensis Essential Oils. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annaz, H.; Abdelaal, S.; Mandour, D.A.; Mahdi, I.; Mahmoud, M.F.; Sobeh, M. Mexican Tea (Dysphania ambrosioides (L.) Mosyakin & Clemants) Seeds Attenuate Tourniquet-Induced Hind Limb Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury by Modulating ROS and NLRP3 Inflammasome Pathways. Journal of Functional Foods 2023, 108, 105712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drioua, S.; El-Guourrami, O.; Assouguem, A.; Ameggouz, M.; Kara, M.; Ullah, R.; Bari, A.; Zahidi, A.; Skender, A.; Benzeid, H.; et al. Phytochemical Study, Antioxidant Activity, and Dermoprotective Activity of Chenopodium ambrosioides (L.). 2024, 22, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekede, K.D.; Dermane, A.; Motto, E.A.; Kpoyizoun, P.K.; Metowogo, K.; Eklu-Gadegbeku, K. In Vitro Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Ex Vivo Nephroprotective Activities of Chenopodium ambrosioides. International Journal of Pharmaceutical, Physical, Chemical and Nutritional Analysis (IJPPNA) 2024, 1, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngolo, L.M.; Faraja, F.M.; Ngandu, O.K.; Kapepula, P.M.; Mutombo, S.M.; Tshitenge, T.B. Phytochemical Screening, UPLC Analysis, Evaluation of Synergistic Antioxidant and Antibacterial Efficacy of Three Medicinal Plants Used in Kinshasa, D.R. Congo. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 10083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everton, G.O.; Serejo, A.P.M.; Arruda, M.O.; Mattos, M.C.A.B.; Gomes, P.R.B.; Marinho, S.C.; Luz, D.A.; Bandeira, M. da G.A.; Dantas, A.R.; Mouchrek Filho, V.E. Antioxidant and Anticancer Activity in Vitro of Chenopodium ambrosioides L. Essential Oil. In Open Science Research; Editora Científica: São Paulo, Brazil, 2025; Vol. 19, pp. 48-63 ISBN 978-65-5360-944-0.

- Maningkas, P.; Pandiangan, D.; Kandou, F. Uji Antikanker Dan Antioksidan Ekstrak Metanol Daun Pasote (Dysphania ambrosioides L.) Anticancer and Antioxidant Test of Methanol Extract of Epazote Leaves (Dysphania ambrosioides L.). JBL 2019, 9, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandiangan, D. Product Quality Test of Pasote Tea Bags Leaves Pasote (Dysphania ambrosioides): Comparison of Antioxidant Activities of Water Extract with Acetone Extract. 2020.

- Kandsi, F.; Conte, R.; Marghich, M.; Lafdil, F.Z.; Alajmi, M.F.; Bouhrim, M.; Mechchate, H.; Hano, C.; Aziz, M.; Gseyra, N. Phytochemical Analysis, Antispasmodic, Myorelaxant, and Antioxidant Effect of Dysphania ambrosioides (L.) Mosyakin and Clemants Flower Hydroethanolic Extracts and Its Chloroform and Ethyl Acetate Fractions. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandsi, F.; Elbouzidi, A.; Lafdil, F.Z.; Meskali, N.; Azghar, A.; Addi, M.; Hano, C.; Maleb, A.; Gseyra, N. Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activity of Dysphania ambrosioides (L.) Mosyakin and Clemants Essential Oils: Experimental and Computational Approaches. Antibiotics 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Wang, L.; Supekar, S.; Shen, T.; Liu, H.; Ye, F.; Huang, J.; Fan, H.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, C. Structure of Human Steroid 5α-Reductase 2 with the Anti-Androgen Drug Finasteride. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdiani, S.; Omidkhoda, N.; Heidari, S.; Hayes, A.W.; Karimi, G. Protective Effect of Luteolin against Chemical and Natural Toxicants by Targeting NF-κB Pathway. BioFactors 2022, 48, 744–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-O.; Choi, A.; Lee, H.-H.; Lee, J.-Y.; Park, S.J.; Kim, B.-H. Purple Corn Extract Improves Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia by Inhibiting 5 Alpha-Reductase Type 2 and Inflammation in Dihydrotestosterone Propionate-Induced Rats. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2025, Volume 15-2024. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Pathophysiological axes in BHP and antioxidant targets of D. ambrosioides.

Figure 1.

Pathophysiological axes in BHP and antioxidant targets of D. ambrosioides.

Figure 2.

PRISMA-like flow diagram of study identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion for the antioxidant activity analysis of D. ambrosioides (DPPH assay, 2005-2025).

Figure 2.

PRISMA-like flow diagram of study identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion for the antioxidant activity analysis of D. ambrosioides (DPPH assay, 2005-2025).

Figure 3.

Heatmap of IC₅₀ values (μg/mL) reported for D. ambrosioides in the DPPH assay. The numerical values represent the concentration required to achieve 50% antioxidant activity, where lighter tones indicate higher potency (lower IC₅₀ values). The vertical scale displays the concentration range from 200 to 1800 μg/mL. Data correspond to studies published between 2013 and 2025.

Figure 3.

Heatmap of IC₅₀ values (μg/mL) reported for D. ambrosioides in the DPPH assay. The numerical values represent the concentration required to achieve 50% antioxidant activity, where lighter tones indicate higher potency (lower IC₅₀ values). The vertical scale displays the concentration range from 200 to 1800 μg/mL. Data correspond to studies published between 2013 and 2025.

Figure 4.

(AR): (a) Interactions of rosmarinic acid with the androgen receptor (AR, 2AM9). Hydrogen bonds are observed with LEU704, ARG752, and LEU873, together with hydrophobic contacts (Alkyl/π-Alkyl) involving LEU704, MET745, and MET780, π-sulphur interactions with MET742, and van der Waals contacts with multiple residues within the active site. (b) The ligand orientation replicates the binding mode of Dihydrotestosterone (control, -10.9 kcal/mol).

Figure 4.

(AR): (a) Interactions of rosmarinic acid with the androgen receptor (AR, 2AM9). Hydrogen bonds are observed with LEU704, ARG752, and LEU873, together with hydrophobic contacts (Alkyl/π-Alkyl) involving LEU704, MET745, and MET780, π-sulphur interactions with MET742, and van der Waals contacts with multiple residues within the active site. (b) The ligand orientation replicates the binding mode of Dihydrotestosterone (control, -10.9 kcal/mol).

Figure 5.

(5AR2): (a) Interactions of luteolin with steroid 5α-reductase type 2 (5AR2, 7BW1). Hydrogen bonds are observed with GLN56, TYR91, and GLU197, together with hydrophobic interactions involving LEU224, and a π-π stacking interaction with PHE223, along with van der Waals contacts with TRP053, GLU057, PHE219, and SER220, among others. (b) The binding affinity (-9.4 kcal/mol) was comparable to that of the control compound finasteride (-13.4 kcal/mol).

Figure 5.

(5AR2): (a) Interactions of luteolin with steroid 5α-reductase type 2 (5AR2, 7BW1). Hydrogen bonds are observed with GLN56, TYR91, and GLU197, together with hydrophobic interactions involving LEU224, and a π-π stacking interaction with PHE223, along with van der Waals contacts with TRP053, GLU057, PHE219, and SER220, among others. (b) The binding affinity (-9.4 kcal/mol) was comparable to that of the control compound finasteride (-13.4 kcal/mol).

Figure 6.

(COX-2): (a) Interactions of luteolin with COX-2 (3LN1). Hydrogen bonds are observed with TYR341, ILE503, and SER516, along with hydrophobic contacts involving VAL335, LEU338, and ALA502, and amide-π stacking interactions with GLY512. (b) The binding pattern replicates the active site occupied by celecoxib (-11.4 kcal/mol).

Figure 6.

(COX-2): (a) Interactions of luteolin with COX-2 (3LN1). Hydrogen bonds are observed with TYR341, ILE503, and SER516, along with hydrophobic contacts involving VAL335, LEU338, and ALA502, and amide-π stacking interactions with GLY512. (b) The binding pattern replicates the active site occupied by celecoxib (-11.4 kcal/mol).

Figure 7.

(NLRP3): (a) Interactions of luteolin with NLRP3 (7ALV). Hydrogen bonds are identified with ALA228, GLN624, and SER626, together with π-cation/π-anion interactions involving GLU629 and TYR632, and a π-π stacking interaction with TYR632, (b) analogous to the binding mode of the MCC950 inhibitor (-9.0 kcal/mol).

Figure 7.

(NLRP3): (a) Interactions of luteolin with NLRP3 (7ALV). Hydrogen bonds are identified with ALA228, GLN624, and SER626, together with π-cation/π-anion interactions involving GLU629 and TYR632, and a π-π stacking interaction with TYR632, (b) analogous to the binding mode of the MCC950 inhibitor (-9.0 kcal/mol).

Figure 8.

(α1A): Interactions of luteolin and rosmarinic acid with the α1A-adrenergic receptor (7YMJ). (a) Luteolin forms hydrogen bonds with THR111, π-anion interactions with ASP106, π-π stacking interactions with PHE288/PHE289, and π-sulphur interactions with CYS110 and MET292. (b) Rosmarinic acid exhibits hydrogen bonds with GLU87 and ASP106, π-π stacking interactions with PHE086 and PHE312, and van der Waals contacts with residues within the transmembrane domain. (c) Both compounds displayed binding affinities (-7.7 kcal/mol) comparable to that of tamsulosin (-7.3 kcal/mol).

Figure 8.

(α1A): Interactions of luteolin and rosmarinic acid with the α1A-adrenergic receptor (7YMJ). (a) Luteolin forms hydrogen bonds with THR111, π-anion interactions with ASP106, π-π stacking interactions with PHE288/PHE289, and π-sulphur interactions with CYS110 and MET292. (b) Rosmarinic acid exhibits hydrogen bonds with GLU87 and ASP106, π-π stacking interactions with PHE086 and PHE312, and van der Waals contacts with residues within the transmembrane domain. (c) Both compounds displayed binding affinities (-7.7 kcal/mol) comparable to that of tamsulosin (-7.3 kcal/mol).

Table 1.

Ranking of the sixteen metabolites with the highest Composite Score values, derived from the normalised mean of the OSIRIS Property Explorer, PASS Online, and ProTox 3.0 indices. Values in bold indicate the compounds with the best overall performance, which were considered priority candidates for multitarget molecular docking studies.

Table 1.

Ranking of the sixteen metabolites with the highest Composite Score values, derived from the normalised mean of the OSIRIS Property Explorer, PASS Online, and ProTox 3.0 indices. Values in bold indicate the compounds with the best overall performance, which were considered priority candidates for multitarget molecular docking studies.

| N° |

Compound |

OSIRIS Property Explorer |

PASS Online |

ProTox 3.0 |

Composite Score |

| 1 |

(+)-4-Carene |

0.340 |

0.569 |

1.000 |

0.636 |

| 2 |

(1R,2R,3R,5S)-(-)-Isopinocampheol |

0.745 |

0.763 |

1.000 |

0.279 |

| 3 |

(E)-Palmitoleic acid |

0.640 |

0.851 |

1.000 |

0.277 |

| 4 |

Linolenic acid, ethyl ester |

0.610 |

0.699 |

1.000 |

0.257 |

| 5 |

(9Z,12Z)-9,12-Octadecadienoic acid |

0.445 |

0.840 |

1.000 |

0.254 |

| 6 |

Ethyl hexadecanoate |

0.610 |

0.647 |

1.000 |

0.251 |

| 7 |

1,4-Dihydroxy-p-menth-2-ene |

0.745 |

0.478 |

1.000 |

0.247 |

| 8 |

2,3-Dihydrobenzofuran |

0.815 |

0.381 |

1.000 |

0.244 |

| 9 |

Isoascaridol |

0.740 |

0.436 |

1.000 |

0.242 |

| 10 |

Phytol |

0.615 |

0.555 |

1.000 |

0.241 |

| 11 |

Palmitic acid |

0.295 |

0.792 |

1.000 |

0.232 |

| 12 |

m-Cymene |

0.525 |

0.494 |

1.000 |

0.224 |

| 13 |

Luteolin |

0.920 |

0.338 |

0.690 |

0.216 |

| 14 |

p-Cymene |

0.418 |

0.502 |

1.000 |

0.213 |

| 15 |

Rosmarinic acid |

0.745 |

0.451 |

0.680 |

0.208 |

| 16 |

Syringic acid |

0.658 |

0.538 |

0.670 |

0.207 |

Table 2.

Binding energies (Vina scores, kcal/mol) of reference drugs and D. ambrosioides metabolites against the five target proteins associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

Table 2.

Binding energies (Vina scores, kcal/mol) of reference drugs and D. ambrosioides metabolites against the five target proteins associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

| Compound |

Site (CurPocket) |

AR (2AM9) |

5AR2 (7BW1) |

COX-2 (3LN1) |

NLRP3 (7ALV) |

α1A (7MYJ) |

| Dihydrotestosterone |

C1 |

-10.9 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Finasteride |

C1 |

- |

-13.4 |

- |

- |

- |

| Celecoxib |

C1 |

- |

- |

-11.4 |

- |

- |

| MCC950 |

C1 |

- |

- |

- |

-9.0 |

- |

| Tamsulosin |

C1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

-7.3 |

| Rosmarinic acid |

C1 |

-9.1 |

-9.3 |

-9.3 |

-8.4 |

-7.7 |

| Luteolin |

C1 |

-8.3 |

-9.4 |

-9.5 |

-8.7 |

-7.7 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).