1. Introduction

The worldwide prevalence of gout among younger individuals (15–39 years) increased to approximately 5.21 million in 2019, with the yearly incidence rising significantly from 38 to 45 per 100,000 population [1]. Gout is a form of inflammatory arthritis caused by excess of uric acid in the blood, characterized by formation of urate crystals affecting the big toe leading to hyperuricemia [2]. The increased uric acid level in the blood precipitates and is deposited in joints and triggers an inflammatory response by the immune system releasing cytokines and chemokines causing pain, swelling, and redness in the affected joints [3]. Xanthine oxidase (XO), a crucial enzyme in the purine breakdown pathway, has been linked to elevated uric acid production. XO catalyses the conversion of hypoxanthine and xanthine to uric acid, and generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydrogen peroxide and superoxide radicals [4]. The generation of these ROS has been associated with the potential onset of several comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular and renal diseases. [5,6]. Additionally, increased XO activity has been observed in many medical conditions such as malaria, sepsis and thalassemia [7]. There is also growing evidence to suggest that the pro-oxidant role of uric acid mediates the generation of ROS and inflammation to promote cancer development and progression by creating a microenvironment that supports tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis [8]. Primarily understanding the pathophysiology of gout at the molecular level led to the discovery of XO inhibitors [9].

Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved allopurinol, febuxostat and topiroxostat as widely used XO inhibitors in clinical settings [10]. However, recent clinical studies have reported side effects due to the long-term effects of these drugs, which induce cardiotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, renal failure and ocular sequelae [11,12]. Some metabolites of these inhibitors tend to modify cellular proteins and trigger an autoimmune response against skin and liver cells [13]. Other adverse side effects such as musculoskeletal symptoms, upper respiratory tract infections, and discrete liver and renal functions were documented in patients receiving synthetic XO inhibitors [14], which poses a restriction to the broad use of these inhibitors in patients. In addition, drug resistance, target enzyme mutations, pharmacokinetic properties, toxicity and off-targets due to selectivity and specificity failure remain as a major concern in the development of XO inhibitor [15]. Thus, there has been an emerging interest in the discovery and development of novel XO inhibitors having very fewer side effects for the treatment of gout and other diseases such as cancer [16]. Orhan and Deniz (2020) reviewed plant-derived secondary metabolites as a significant source of XO inhibitors as well as potent in vitro anti-proliferative activity against various cancer cell lines. These compounds are considered potential lead molecules for the design and development of drugs targeting XO inhibition and novel anticancer agents, due to their high selectivity and efficacy in targeting crucial human proteins or enzymes [18].

Anastatica (A.) hierochuntica (L.), popularly named as Kaff Maryam (Mary's hand), True Rose Jericho, or Genggam Fatimah, is a monotypic desert species of the plant family "Anastatica" with tumbleweed and resurrection properties [19]. A. hierochuntica has been in practice among the locals population for its ethnomedicinal properties, and its pharmacologically important activities have been systematically reviewed [20]. It has been reported to encompass novel compounds like anastatin A and B [21], hierochins A, B, and C [22], as well as several flavonoids, flavones, lignans, phenolic compounds, etc. [23]. Despite the insights into the hepatoprotective, gastroprotective, carcinopreventive, anti-proliferative properties of A. hierochuntica, there is a lack of knowledge on the XO inhibitory potential and pharmacokinetics properties of metabolites present in the methanolic extract of A. hierochuntica leaves. Thus, the current study focuses on identified A. hierochuntica methanolic leaves extract-derived metabolites exhibiting XO inhibitory activities using in vitro and in silico models, which provided prediction of their pharmacokinetic, toxic, and anticancer properties, as well as their oral bioavailability and endocrine disruption.

2. Results

2.1. Chemical Structures of the Metabolites Identified in Crude Methanolic Extracts of Leaves of A. hierochuntica

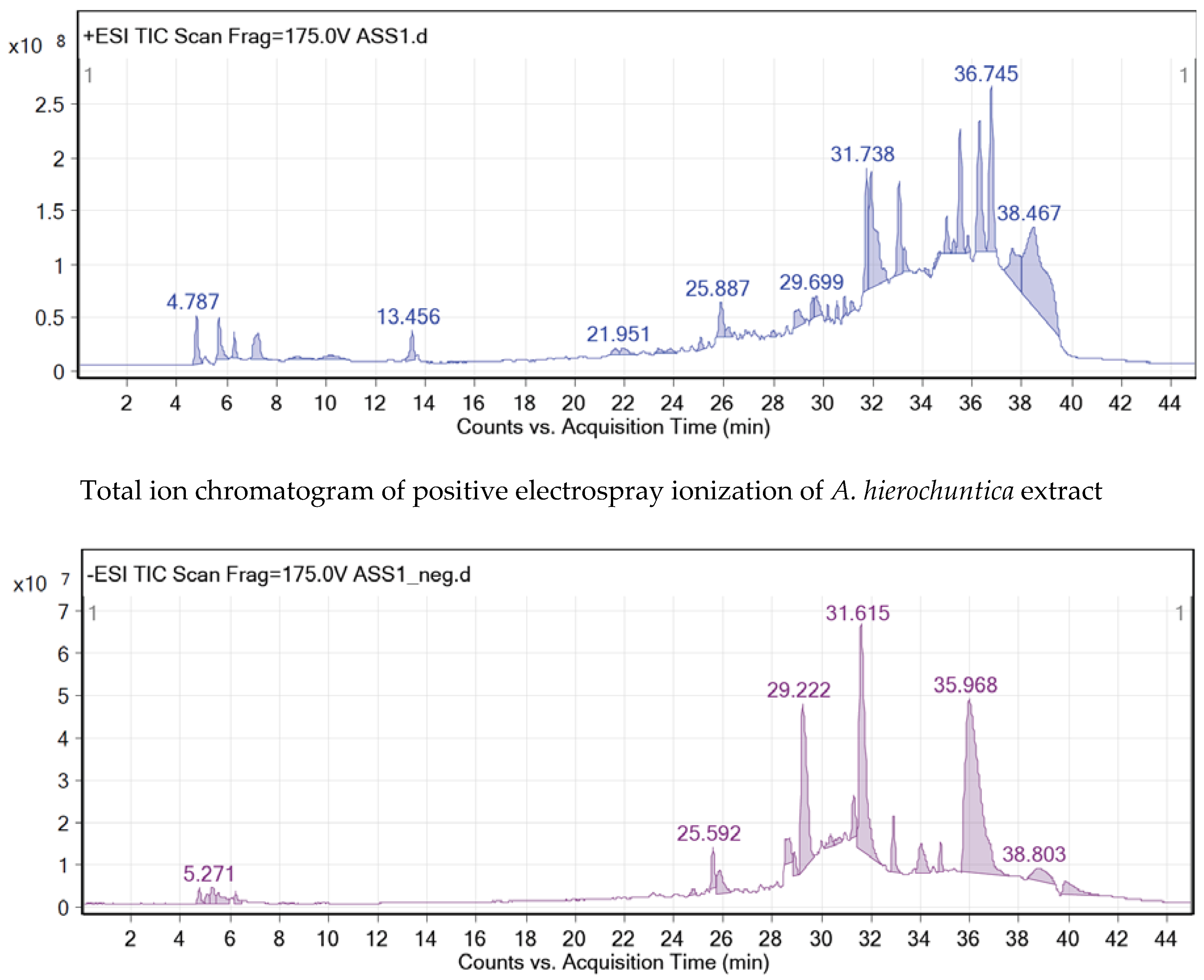

The crude methanolic leaves extract of the

A. hierochuntica was subjected to total ion current (TIC) spectra. Qualitative and quantitative data analyses by MassHunter software showed a mass screening spectrum in positive and negative ionization modes (

Figure 1). Chemical features were extracted from liquid chromatography-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (LC-QTOF-MS) data using the molecular feature extraction (MFE) algorithm. The recursive analysis workflow was extracted by screening detected nodes at various retention times per minute, with a minimum intensity of 6,000 counts and aligned with previously detected compounds (

Table 1) considering adducts ([M+K]

+ and [M-H]

-). Most metabolites were better ionized in positive mode than in negative mode, since flavonoid fragmentations can be documented in both positive and negative ion modes

. A total of 12 peaks were tentatively identified showing high content of flavonoids belonging to various classes such as flavones (4), flavonols (2), neolignans (2), flavanones (1), phenols (1), flavanonols (1) and quinic acid derivatives (1).

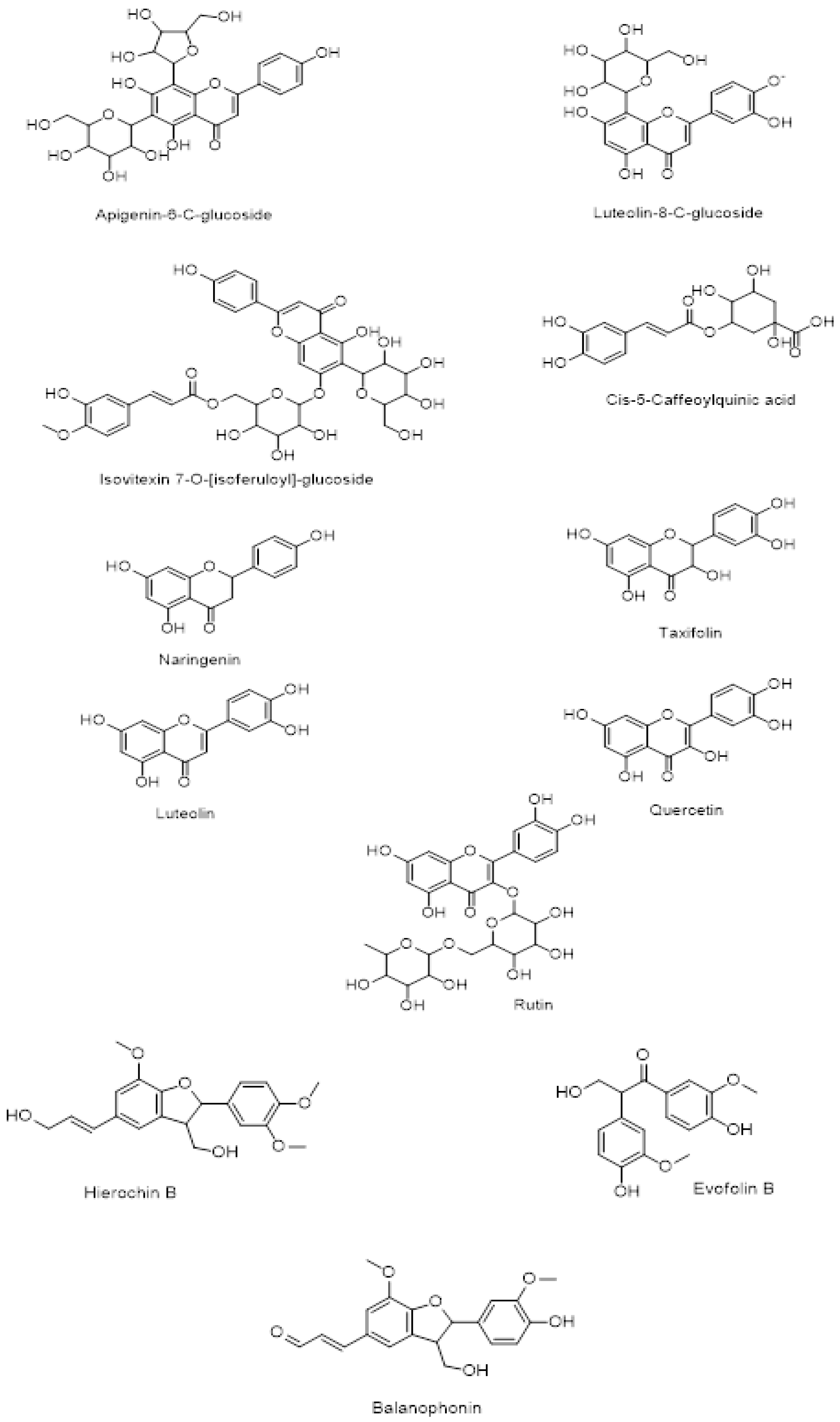

The chemical structure of secondary metabolites present in A. hierochuntica methanolic leaves extract (Figure 2) was drawn using ChemDraw software and the simplified molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES) was used to generate the computational results.

2.2. Molecular Docking of the Identified A. hierochuntica Methanolic Leaves Extract-Derived Metabolites with Crystal Structure of Bovine XO

Molecular docking was employed to explore the interactions between the tentatively identified compounds in the methanolic leaves extract of

A.hierochuntica for their potential XO inhibitory activity. From our experimental results, it appeared that

A. hierochuntica leaves extract exhibited remarkable inhibition of the XO enzyme. However, the molecular bases of this inhibition needed to be investigated. Therefore, the identified metabolites were docked into XO binding pocket, and the results of post-docking analysis of binding affinities and interactions between XO and metabolites are summarized in

Table 2.

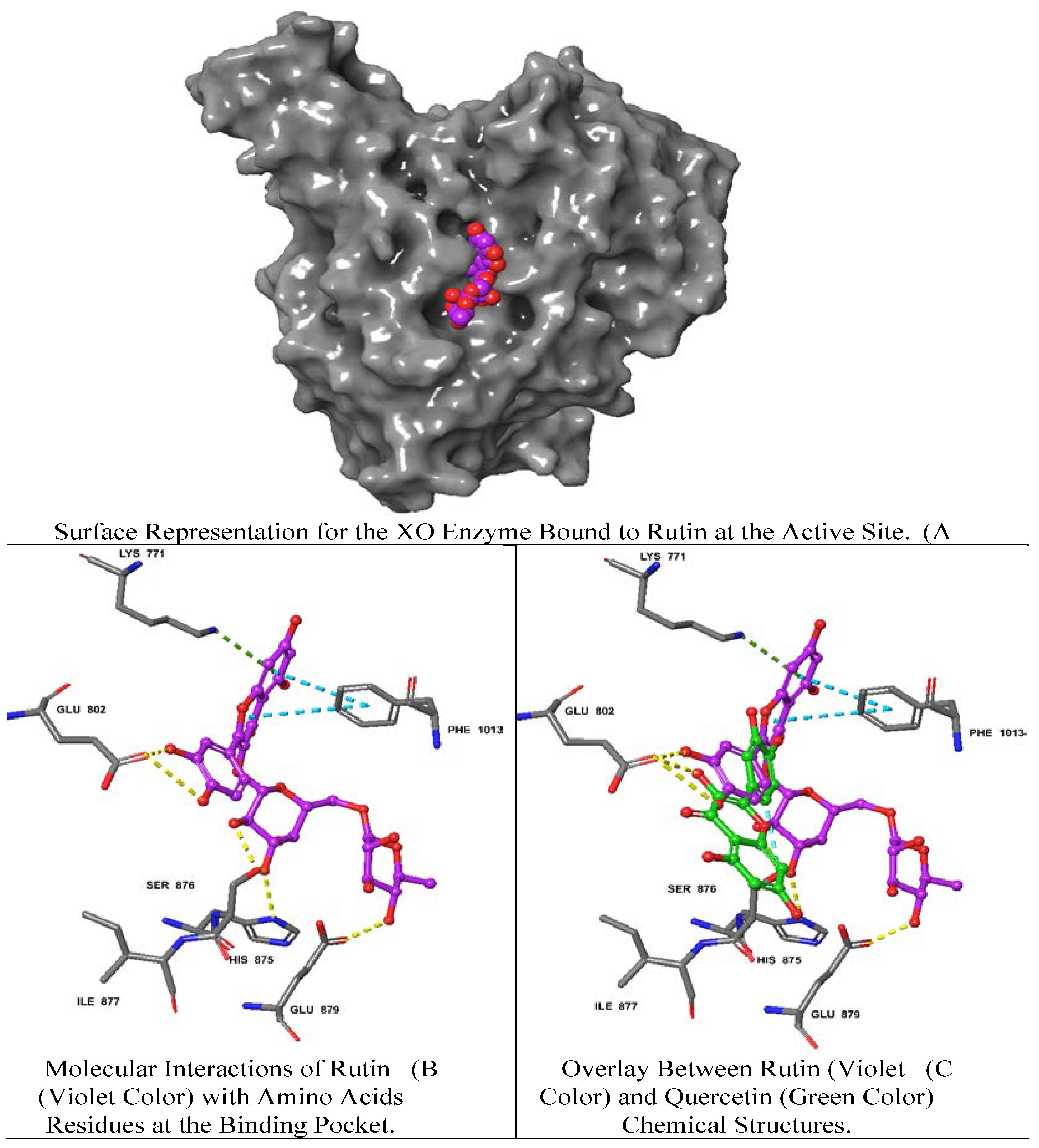

Rutin demonstrated the best docking score (-12.39) with multiple interactions including hydrogen bonds (H bond) with GLU 802, GLU 879, SER 876, HIS 875 residues, a pi (π)-cation interaction with LYS 771 and a π-π stacking interaction with PHE 1013. Moreover, quercetin and luteolin exhibited docking scores of -11.15, and -10.43, respectively, with multiple H-bonds and π-π interaction, as summarized in

Table 2. On the contrary, isovitexin 7-O-[isoferuloyl]-glucoside displayed a low interaction score of -4.49 including the least (H-bond) with THR 1010 and the π-π interaction at PHE 649, LYS 771, PHE 914, PHE 1009, PHE 1013 residues. Hierochin B showed a docking score of -7.75 with at π-π interaction only at PHE 1009.

We overlaid the chemical structure of rutin (violet) with that one of quercetin (green), revealing the aromatic ring of rutin stretched with several hydrophobic residues including GLU 802 and SER 876 (

Figure 3). It is worth mentioning that quercetin is the native ligand present in the XO crystal structure, and it is one of the metabolites identified in

A. hierochuntica methanolic leaves extract. It could be inferred that the H bond and electrostatic interactions stabilize both rutin and quercetin in the XO pocket. Interestingly, the rutin docking score was higher than that of quercetin, which might be due to the differences in chemical structure, as shown in

Figure 3.

The two-dimensional structures of rutin and the XO achieved the best docking score (-12.39) with multiple interactions including yellow dashed lines representing H bonds with GLU 802, GLU 879, SER 876, HIS 875 residues, dark green denoting π-cation interaction with LYS 771 and faded teal color indicating π-π interactions with PHE 1013.

2.3. Validation of XO Inhibitory Activity of Selected A. hierochuntica Methanolic Leaves Extract-Derived Metabolites Using an In Vitro Enzymatic Assay

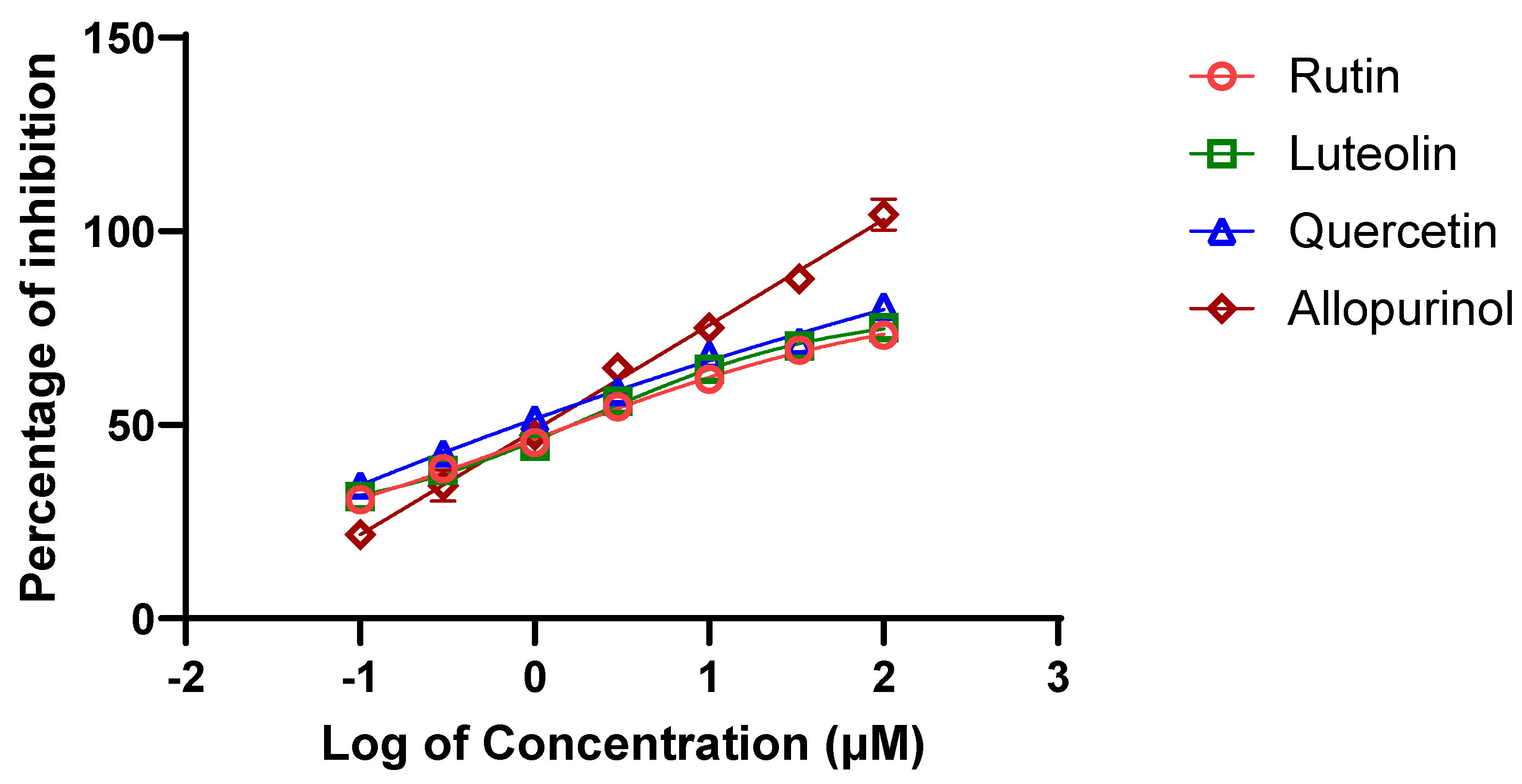

Among the 12 metabolites identified in the

A. hierochuntica methanolic leaves extract that showed the best predicted docking scores against bovine XO, we sought to evaluate the

in vitro potential XO inhibitory activity of three bioactive metabolites (i.e., rutin, quercetin and luteolin) along with the positive control, allopurinol. Using the XO enzymatic activity kit, the inhibitory effects of the metabolites were evaluated at increasing concentrations and their half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC

50) values resulting in 50% decrease in XO activity were determined from dose-response curves (

Figure 4). As shown in

Table 3, the IC

50 values for rutin and quercetin were both determined to be approximately 11.0 μM while the luteolin IC

50 was 21.5 μM. Thus, the inhibitory effect of luteolin was observed to be the weakest of the three metabolites, and the ranking of these IC

50 values confirmed the predictive results of interactions via molecular docking.

2.4. Physicochemical Parameter Evaluation of A. hierochuntica Methanolic Leaves Extract-Derived Metabolites

Drug molecules must be tested and evaluated for their physicochemical properties before entering the pharmaceutical field and clinical trials. Thus, several crucial properties for drug development, including oral bioavailability, safety and drug-likeness, were evaluated using the SwissADME web server. Data in

Table 4 showed that three metabolites (

i.e., apigenin-6-C-glucoside, isovitexin 7-O-[isoferuloyl]-glucoside, and rutin) exceeded the recommended range (500 g/mol) of molecular weight (MW) limit required for orally active drugs according to Lipinski's rule of five (ROF). Moreover, five metabolites violated the rule of the number of H bond donors and acceptors, including apigenin-6-C-glucoside, luteolin-8-C-glucoside, isovitexin 7-O-[isoferuloyl]-glucoside, Cis-5-caffeoylquinic acid, and rutin. Further computational analysis revealed that all the metabolites exhibited an acceptable degree of lipophilicity and hydrophilicity, as determined by Log Po/w and Log S. The results of our distribution prediction indicate that only seven metabolites would show high gastrointestinal (GI) absorption, while only Hierochin B would cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Additionally, very few metabolites were predicted to inhibit cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, while the majority of them did not appear to inhibit CYP enzymes (

Table 4).

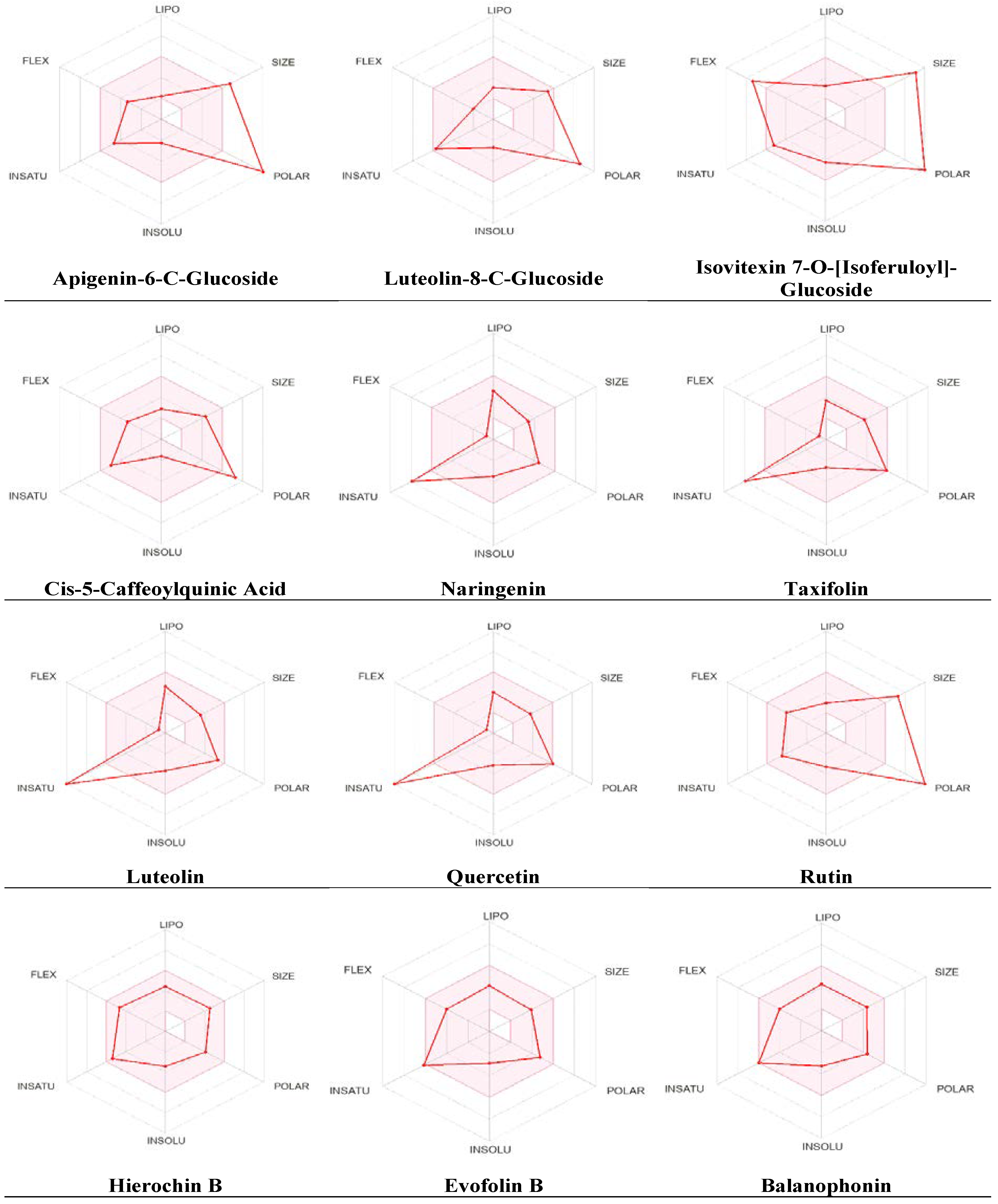

Additional pharmacokinetic evaluation was performed for the metabolites using the SwissADME tool to gain deeper insights into the improved bioavailability and drug-like attributes of the identified phytochemicals, we conducted an analysis using the bioavailability radar (

Figure 5). Predicted properties include Polarity (POLAR) measured by TPSA, which ranges from 20 to 130 Ų; insolubility (INSOLU) as indicated by log S, without exceeding 6; lipophilicity (LIPO) represented by XLOGP3, falling within the range of -0.7 to +5.0; flexibility (FLEX) with no more than 9 rotatable bonds; insaturation (INSATU) ensuring that the fraction of carbons in sp3 hybridization was not less than 0.25 and size (SIZE), with the molecular weight falling between 150 and 500 g/mol. The red line indicates the predicted property for the tested molecule, while the pink-shaded zone represents the recommended range for the properties. As shown in

Figure 5, most metabolites had significant drug-like characteristics that were within the recommended range, except for a few metabolites that were predicted to be out of the range.

The SwissADME tool was used to calculate oral bioavailability and the results were represented in radar chart. The pink-shaded zone represents the recommended range for the following properties: Polarity (POLAR), solubility (INSOLU), lipophilicity (LIPO), flexibility (FLEX), saturation (INSATU), and size (SIZE) for the A. hierochuntica methanolic leaves extract-derived metabolites.

2.5. Predicted Toxicity Assessment of A. hierochuntica Methanolic Leaves Extract-Derived Metabolites

It is crucial to evaluate a variety of toxicities for any promising molecule or lead compound before reaching the

in vivo and clinical stage. Thus, the toxicological profile of the

A. hierochuntica methanolic leaves extract-derived metabolites was computed using the ProTox-II web server. None of the metabolites exhibited hepatotoxicity (

Table 5). Furthermore, only three metabolites were predicted to be carcinogenic, while six metabolites were computed to exhibit immunotoxicity and four were predicted to be mutagenic. Only Naringenin was predicted to be cytotoxic according to the ProTox-II web server.

2.6. Estimation of Anticancer Activity Spectra of A. hierochuntica Methanolic Leaves Extract-Derived Metabolites

In this study, we sought to determine the anticancer activity of each bioactive metabolite identified in the

A. hierochuntica methanolic leaves extract using the Prediction of Activity Spectra for Substances (PASS) online web server. The probabilities of the presence of biological activity (Pa) or absence of biological inactivity (Pi) can be seen from the data in

Table 6. The majority of the metabolites demonstrated a significant positive anticancer activity prediction, as indicated by a Pa greater than 70%. Moreover, six out of twelve exhibited a predicted anticancer activity greater than 80%, suggesting a high probability for these metabolites to be active as anticancer agents.

2.7. Evaluation of Endocrine Disruption Potential

Molecular binding of identified metabolites to 14 nuclear receptors (androgen receptor (AR), estrogen receptors α (ER α) and β (ER β), glucocorticoid receptor (GR), liver X receptors α (LXR α) and β (LXR β), mineralocorticoid receptor (MR); peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors α (PPAR α), β (PPAR β), and γ (PPAR γ), progesterone receptor (PR), retinoid X receptor α (RXR α), and thyroid receptors α (TR α) and β (TR β)) was assessed and evaluated using Endocrine Disruptome, an open source web server. As depicted in

Table 7, these results represent the free binding energies of the tested compounds which were divided into 3 classes indicated by the different colors: red, yellow/orange and green showing high, intermediate and low likelihood of binding to the selected receptor, respectively.

Apigenin-6-C-glucoside showed a lack of affinity towards a variety of nuclear receptors while luteolin-8-C-glucoside, isovitexin 7-O-[isoferuloyl]-glucoside, and rutin exhibited a moderate binding prediction at AR, GR and PR, respectively. Moreover, cis-5-caffeoylquinic acid, naringenin, hierochin B, evofolin B, and balanophonin showed intermediate binding affinity for several nuclear receptors. Only a few metabolites demonstrated moderate binding affinity on multiple receptors with a high probability of binding to AR and MR such as naringenin, taxifolin, luteolin, and quercetin.

3. Discussion

In the search for novel natural XO inhibitors with potential anticancer activity, the present study aimed to unravel possible interactions between A. hierochuntica methanolic leaves extract-derived metabolites and XO protein binding sites via molecular docking as well as to validate their XO inhibitory activities using an enzymatic assay. Furthermore, pharmacokinetic properties, oral bioavailability, ADME predictions, assessment of CYP enzyme inhibition, predicted toxicity, endocrine disruptions and anticancer activity were evaluated for the bioactive metabolites identified in the A. hierochuntica methanolic leaves extract using various computational modeling tools.

The metabolic profiling of the A. hierochuntica leaves extracted with methanol were analyzed using LC-QTOF-MS, which confirmed the detection of unknown constituents present in the extract. The presence of flavonoids outweighed phenols, neolignans and quinic acid derivatives in the leaves extract. Within the flavonoid group, reports on the presence of quercetin, naringenin, isovitexin 7-O-[isoferuloyl]-glucoside and apigenin-6-C-glucoside were confirmed by the NMR studies of the methanolic plant extract [25]. Similarly, neolignans and phenolic acid such as hierochin B, balaanophonin and evofolin B, respectively, reported to have potential to inhibit melanogenesis and nitric oxide production [21,22]. Additionally, luteolin, taxifolin, rutin as well as naringenin and quercetin have demonstrated anti-melanogenic activity [21]. Quercetin, taxifolin and naringenin have also exhibited hepatoprotective and antileukemia properties, respectively. Furthermore, AlGamdi et al. (2011) reported the antioxidant potential of apigenin-6-C-glucoside, luteolin-8-C-glucoside, isovitexin 7-O-[isoferuloyl]-glucoside, Cis-5-Caffeoylquinic acid in the aqueous extract of the A. hierochuntica plant [23].

Molecular docking simulation studies were performed between the 12 metabolites tentatively identified in the methanolic leaves extract of A. hierochuntica and the binding pocket of bovine XO enzyme. Bovine XO is an enzyme that mediates the oxidation of the hypoxanthine scaffold to xanthine and is structurally composed of dimeric metallo-flavoprotein that shares 90% homology with the human enzyme [27]. Ligand formation with H bonds in the protein promotes the stabilization of protein- ligand complexes while π–π interactions are generally weaker than H bonds, but contribute to the binding affinity of ligand-protein complexes, especially when ligands or protein residues contain aromatic rings [28].

In the present study, the H bond analysis was performed to reveal the stability of the XO protein with the rutin ligand complex, confirming the formation of 4 H bonds with GLU 802, GLU 879, SER 876, HIS 875 amino acid residues with a docking score of -12.39. Similar docking scores for rutin and its derivatives (RU3a1, RU3a2, RU3a3, RU4b1, RU4b2, RU7c1, RU7c2, RU7c3) against the binding site of XO were reported in the range of -10.944 to -13.244 [29], exhibiting comparable molecular interactions. Furthermore, the formation of π–π bond with PHE 1013 was due to the interaction of the C ring of rutin within the structural domain of XO, leading to the establishment of hydrophobic interactions [30].

Similarly, quercetin and luteolin demonstrated similar H bond formation with amino acid residues SER 876, ARG 880, THE 1010, while quercetin exhibited additional H bond formation with GLU 802, with scores of -11.15 and -10.45, respectively. Lin et al. (2002) reported the interaction identical to that observed in the present study, where the C3 polar hydroxyl group of quercetin was surrounded by PHE 914, PHE 1009, THE 1010 and ARG 880 residues. Luteolin exhibited additional hydrophobic interactions at Glu802, Leu873, Val1011, Leu1014, and Pro1076 apart from the interactions reported in the present research, resulting in reduced catalytic activity and altered secondary structure of XO [32].

In our results, isovitexin 7-O-[isoferuloyl]-glucoside showed the formation of 4 π–π interactions with PHE 649, 914, 1009, 1013 residues belonging to the phenylalanine aromatic ring residue of and one π–π interaction with LYS 771 residue. Likewise, naringenin, quercetin, 5-caffeoylquinic acid, luteolin, balanophonin and evofolin B presented two π–π interactions at PHE 914, 1009 residues. Derived from luteolin, 6-hydroxyluteolin exerts electrostatic interaction forces (π–π bond) and H bonds and exhibits high affinity for the XO binding site [33]. Moreover, a good binding affinity for a particular application may differ depending on the intended use of the interaction. Thus, these metabolites prove to ensure the stability and specificity of the complex and also justify the docking result.

In the present study, in vitro XO inhibitory assays was performed to validate and assess the inhibitory potential of the flavonoids identified in the methanolic leaves extract of A. hierochuntica against XO activity. Among all flavonoids, quercetin had the lowest IC50 value of 11.1 µM, followed by rutin and luteolin. However, rutin failed to act as a supreme inhibitor of XO compared to quercetin, as predicated by molecular docking, which could be primarily due to the implausibility of achieving the entropy effect, which does not work reliably for all targets [34]. It is crucial to note that binding affinity can vary depending on factors like pH, temperature, and the presence of other ligands or cofactors [35].

Xue et al. (2023) comprehensively reviewed the function of flavonoids in XO inhibition through in silico and in vivo studies. Reports on in vitro inhibition of XO by rutin and its derivatives displayed reduced catalytic activity of XO with an IC50 for rutin of 20.87 μM, which almost aligns with our results in the present study, while rutin derivatives showed IC50 ranging from 4.71 μM to 19.38 μM [29]. Studies on the inhibitory potential of luteolin against XO are discussed because many researches presented a varied range of IC50 value of 4.79 μM [33], while 6-hydroxyluteolin, a luteolin derivative showed an IC50 value of 7.52 μM, which are comparable to the results of the present study. Quercetin inhibited XO most effectively with an IC50 value of 6.45 μM, in research conducted to explore the XO inhibitory mechanism of phenolic compounds [37]. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2018) reported the formation an XO–quercetin complex alters the conformation of XO and decreases its activity to an IC50 of 2.74 μM [38]. Finally, it has been reported that the methanolic leaves extract of A. hierochuntica exhibited XO inhibitory properties as it encompasses the presence of different flavonoid group. Likewise, many plant extracts rich in secondary metabolites known to reduce XO catalytic activity are systematically reviewed [23,39]. Furthermore, reports on the planar structure of flavonoids [40], and the induction of conformational change in the active site of XO rationalize the role of flavonoids as a potential XO inhibitors.

It was also crucial to assess the pharmacokinetic profile of A. hierochuntica metabolites to be evaluated as a prospective drug candidate, in addition to demonstrating the desired biological activity. The solubility of the compound is one of the crucial characteristics that impacts its absorption and distribution within the body and was determined by assessing its aqueous solubility [42]. These findings indicate that a large portion of the compounds exhibit high water solubility. Lipophilicity and skin permeability coefficient (Kp) should be analyzed together effectively for the transport of compounds across mammalian skin. A lower log Kp value indicates lower permeability of the molecule through the skin and a lipophilicity between 0 and 5 is usually considered optimal for drug design [43]. Most compound log Kp values were between -6.17 and -10.19 with naringenin, quercetin, luteolin hierochin B, evofolin B, and balanophonin, demonstrating effective permeability with optimal lipophilicity [44]. Apigenin-6-C-glucoside, luteolin-8-C-glucoside, isovitexin 7-O-[isoferuloyl]-glucoside, Cis-5-caffeoylquinic acid, and rutin illustrates minimal gastrointestinal (GI) absorption, indicating a low rate of entry into the bloodstream, thereby supporting its limited systemic distribution and reduced adverse effects [45].

Comprehending the interplay between compounds and the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system is of significant importance for understanding the pharmacokinetics of potential drug candidates, as they play a pivotal role in the metabolism and clearance of drugs from the body [46]. It is well known that many polyphenolic compounds inhibit specific isoforms of CYP enzyme due to the most complex, varied structure with multiple functional groups, enhancing their binding affinity with different CYP enzyme isoforms [47]. In the present study, naringenin, luteolin, quercetin, hierochin B, and evofolin B were predicted to inhibit some specific isoforms within the CYP enzyme that would ultimately be useful in enhancing the bioavailability of certain drugs by reducing their metabolism, thus potentially increasing their therapeutic effects [48]. According to the ADMET predictions, it is noteworthy that a significant proportion of the phytoconstituents showed drug-likeness properties by satisfying Lipinski's Rule of 5 (RO5), while three compounds were found to violate, possibly due to the complex structures of the phytoconstituents and the majority of them achieved favorable scores for bioavailability.

On the analysis of the toxicity, it should be noted that none of the compounds reported hepatoxicity, which may be attributed to the potential hepatoprotective effects of the studied plant extract on D-galactosamine-induced cytotoxicity in primary cultured mouse hepatocytes [21]. Furthermore, these results were linked to the in vivo investigation reporting the improvement in liver function of the rats exposed to carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced and subsequently treated with plant extracts due to the effect of anti-oxidant compounds that reduce lipid peroxidation.

The ProTox-II cytotoxicity model classifies compounds as cytotoxic if their IC50 values are ≤10 μM in the in vitro toxicity assay using HepG2 cells [50], which could be the reason for the positive score obtained against naringenin only. Nevertheless, numerous studies have documented the antiproliferative potential of plant extracts against various cancer cell lines, including HeLa [51], AMN-3 [52], and MCF-7 [53,54], indicating their promising cytotoxicity against cancer cells. Roughly, about 30% of the phytoconstituents were found to be mutagenic, which was contrary to the in vivo results of the plant extracts tested by in vivo mammalian erythrocyte micronucleus assays demonstrating no significant mutagenicity in Sprague Dawley rats [55].

Moving forward, the anticancer activity was predicted based on the anticarcinogenic parameter of PASS web server by comparing the structure of A. hierochuntica metabolites with structure of standard active biological substrate including drugs, drug-candidates, leads and toxic compounds in the training set based on the Bayesian approach [56]. Experimental studies related to the anticancer activity of metabolites were conducted in skin [26,57], leukemia [24], cervical [58], breast [54], lung cancer confirming the anticancer properties of the metabolites based on previous experimental results.

Despite the ill-famed status, endocrine disruptors are increasingly recognized for their numerous beneficial effects [60]. Phytoestrogens, found naturally in plants and foods, are a type of endocrine-disrupting chemical considered safe for consumption and use in moderation [61]. Flavonoids has demonstrated high affinity toward the androgen receptor (AR) in human prostate cancer cell lines through the AR-dependent signalling pathway by decreasing the secretion of prostate-specific antigen levels and heat shock proteins [62]. Thus naringenin, taxifolin, luteolin, quercetin was suggested to exert non-genomic actions, promoting their role as a therapeutic agent against hormone-dependent cancer types [63]. Furthermore, a retrospective study reported the underlying mechanistic link of reduced secretion of serum urate levels in patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy [64]. These finding further strengthen the therapeutic potential of these metabolites in the management of hyperuricemia.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals

Analytical grade methanol, water and standards (rutin, quercetin, luteolin, allopurinol) of HPLC grade were purchased from Merck (Kenilworth, NJ, USA).

4.2. Plant Extraction

A. hierochuntica was collected during the spring season from Raudhat Shams in the central region of Saudi Arabia. The plant was authenticated by the Siddha Central Research Institute, Chennai, India and the voucher specimen number code A25072201H was issued with the certificate. The leaves were separated from the whole plant, then ground into fine particles and extracted with methanol and water in a 1:3 ratio. Later, the solvents were concentrated using a rotary evaporator and the methanolic leaves extracts were weighed and stored at 4℃ until use.

4.3. Screening of A. hierochuntica Methanolic Leaves Extract-Derived Metabolites Using LC-QTOF-MS

The identification of A. hierochuntica methanolic leaves extract-derived metabolites was performed using the Agilent 1260 Infinity high-performance liquid chromatography (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) coupled with Agilent 6530 Quadrupole Time of Flight (Q-TOF). The analysis was performed using SB-C18 Agilent column (4.6 mm × 150 mm, 1.8 μm) with the elution gradient; 0–2 min, 5% B; 2–17 min, 5–100% B; 17–21 min, 95% B; 21–25 min, 5%B, using mobile phase A (0.1% formic acid in water) and mobile phase B (0.1% formic acid in methanol). The flow rate was set at 250 μL/min, with an injection volume of 10 μL. The scanning range was set at 50–800 (m/z), gas temperature at 300°C, gas flow at 8 L/min, nebulizer pressure at 35 psi, sheath gas temperature at 350°C, and sheath gas flow rate at 11 L/min. High-resolution masses were measured using Agilent MassHunter qualitative analysis software (version B.06.00).

4.4. Molecular Docking Study

A molecular docking study was conducted for the identified metabolites against the crystal structure of bovine XO using Maestro, Schrödinger (Release 2022-3, New York, NY) to assess and evaluate the molecular interactions between XO binding site and metabolites. Thus, the crystal structure of bovine XO in the complex with quercetin (PDB ID: 3NVY,

https://www.rcsb.org/structure/3nvy) was utilized because it shares 90% similarity with the human enzyme. Briefly, two-dimensional structures of metabolites were prepared using the LigPrep tool, followed by enzyme preparation using the protein preparation workflow. The docking grid was generated using the receptor grid generation tool. The metabolites were docked and the results were subjected to post-docking analysis. Both docking scores and molecular protein-ligand interactions were used as parameters for docking pose selection.

4.5. Enzyme Inhibition Assay

The XO inhibitory activity of the three bioactive metabolites (i.e., rutin, quercetin and luteolin) that showed the best docking scores, among the 12 metabolites, were evaluated using Xanthine Oxidase Activity Assay Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Co LLC, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Allopurinol was used as a positive control. The experiments were performed in triplicate and each experiment was repeated independently three times. The control and reagent blank were prepared without the extracts and enzyme, respectively. The enzyme inhibition percentage was calculated using the formula: (ΔODcontrol−ΔODsample)/ ΔODcontrol×100, where OD (optical density) ΔODcontrol and ΔODsample are reagent blank-corrected optical density values of control and test samples, respectively.

4.6. Pharmacokinetic Properties Predictions

The absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties of the identified metabolites were predicted using SwissADME web server (

http://www.swissadme.ch/, accessed on April 30, 2024). These properties include molecular weight, lipophilicity, solubility, gastrointestinal absorption, CYP enzyme inhibition, and most importantly, drug-likeness property. The recommended range for each property was based on Lipinski’s ROF for orally active drugs, and violations of one or more of these rules indicate lower oral bioavailability.

4.7. Organ and Endpoint Toxicity Assessment

Toxicity predictions for the identified metabolites were performed using the ProTox-II web server (

https://tox-new.charite.de/protox_II/, accessed on April 30, 2024). The website uses machine learning models to provide rapid and accurate predictions of small molecule toxicity. The evaluation includes hepatotoxicity, cytotoxicity, carcinogenicity, mutagenicity, and immunotoxicity, thereby reducing the need to conduct animal toxicity experiments. Results are represented as the probability of activity (toxic) or inactivity (non-toxic) for a specific type of toxicity.

4.8. Prediction of Anticancer Activity

The PASS Online web server is a freely accessible website that contains a database of active compounds with over 4,000 types of biological activity (

http://www.way2drug.com/passonline/, accessed on April 28, 2024). The two-dimensional structure is used to generate anticancer computational predictions for the identified metabolites. Results are represented as the probability that the compound is active (P

a) and inactive (P

i) for a specific biological activity. A probability greater than 50% indicates a higher potential for the compound to be experimentally active.

4.9. Predictions of Endocrine Disruptors Properties

Prediction of metabolite activity on 14 nuclear receptors was performed using the Endocrine Disruptome web server (

http://endocrinedisruptome.ki.si/, accessed on April 30, 2024). The web server docks each metabolite into crystal structures of nuclear receptors including receptors AR, ER α/β, glucocorticoid receptor (GR), liver X receptor (LXR) α/β, mineralocorticoid receptor (MR); peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors α (PPAR α), β (PPAR β), and γ (PPAR γ), progesterone receptor (PR), retinoid X receptor α (RXR α), and thyroid receptors α (TR α) and β (TR β). The web server outcomes are classified into three main classes: red (high binding potential), orange, and yellow, which suggest moderate binding, and green, which indicates low probability of binding to docked receptors.

4.10. Statistical Analysis

All the data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). IC50 values were determined using GraphPad Prism software version 6 for Windows (La Jolla, California, USA).

5. Conclusions

Our results show the presence of rich sources of 12 secondary metabolites in the methanolic leaves extract of A. hierochuntica. Rutin inhibited the XO active site, as revealed by molecular docking studies and was further validated in vitro through an XO inhibition assay. Moreover, the in silico prediction model strongly suggests the safety and drug-likeness of these metabolites, providing a promising approach to treat hyperuricemia and may serve as good candidates for selective screening of anticancer leads. Thus, the current study aims to introduce a new paradigm for treating human malignancies, supported by future investigations of metabolites in in vivo studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Saranya Rameshbabu and Zeyad Alehaideb; Data curation, Saranya Rameshbabu, Zeyad Alehaideb, Feras Almourfi, Syed Yacoob, Anuradha Venkataraman and Safia Messaoudi; Formal analysis, Zeyad Alehaideb, Sahar Alghamdi, Rasha Suliman and Feras Almourfi; Funding acquisition, Zeyad Alehaideb; Methodology, Saranya Rameshbabu, Zeyad Alehaideb and Safia Messaoudi; Project administration, Zeyad Alehaideb and Sabine Matou-Nasri; Resources, Saranya Rameshbabu and Zeyad Alehaideb; Software, Sahar Alghamdi and Rasha Suliman; Supervision, Zeyad Alehaideb, Syed Yacoob, Anuradha Venkataraman and Sabine Matou-Nasri; Validation, Syed Yacoob, Anuradha Venkataraman, Safia Messaoudi and Sabine Matou-Nasri; Visualization, Saranya Rameshbabu, Zeyad Alehaideb, Feras Almourfi and Sabine Matou-Nasri; Writing – original draft, Saranya Rameshbabu, Zeyad Alehaideb, Sahar Alghamdi, Rasha Suliman and Sabine Matou-Nasri; Writing – review & editing, Saranya Rameshbabu, Zeyad Alehaideb, Sahar Alghamdi, Rasha Suliman, Feras Almourfi, Syed Yacoob, Anuradha Venkataraman, Safia Messaoudi and Sabine Matou-Nasri.

Funding

This study was funded by King Abdullah International Medical Research Centre under grant number RC16/175/R.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the host institutions for their support throughout the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no financial or commercial conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

ADME, absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion; BBB, blood-brain barrier; CYP, cytochrome P450; ESI, electrospray ionization; FLEX, flexibility; GI, gastrointestinal; H, hydrogen; INSATU, insaturation; INSOLU, insolubility; LC-QTOF-MS, liquid chromatography-quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometry; LIPO, lipophilicity; LOX, lipoxygenase; LT, leukotrienes; MFE, molecular feature extraction; MW, molecular weight; POLAR, polarity; ROF, rule-of-five; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SD, standard deviation; SMILES, simplified molecular-input line-entry system; TIC, total ion current; XO, xanthine oxidase

References

- Zhang, J.; Jin, C.; Ma, B.; Sun, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Han, C.; Liu, T.; Li, Y. Global, regional and national burdens of gout in the young population from 1990 to 2019: a population-based study. RMD Open. 2023, 9, e003025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murdoch, R.; Barry, M.J.; Choi, H.K.; Hernandez, D.; Johnsen, B.; Labrador, M.; Reid, S.; Singh, J.A.; Terkeltaub, R.; Vazquez Mellado, J.; et al. Gout, hyperuricaemia and crystal-associated disease network (G-CAN) common language definition of gout. RMD Open. 2021, 7, e001623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamp, L.K.; Dalbeth, N. Prevention and treatment of gout. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2019, 15, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battelli, M.G.; Polito, L.; Bortolotti, M.; Bolognesi, A. Xanthine oxidoreductase-derived reactive species: physiological and pathological effects. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016, 2016, 3527579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Joshi, G.; Kler, H.; Kalra, S.; Kaur, M.; Arya, R. Toward an understanding of structural insights of xanthine and aldehyde oxidases: an overview of their inhibitors and role in various diseases. Med Res Rev. 2018, 38, 1073–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; Cheng, J.D. Uric acid and cardiovascular disease: an update from molecular mechanism to clinical perspective. Front Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 582680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charles Seychell, B.; Vella, M.; James Hunter, G.; Hunter, T. The Good and the Bad: The Bifunctional Enzyme Xanthine Oxidoreductase in the Production of Reactive Oxygen Species [Internet]. Reactive oxygen species – Advances and Developments. IntechOpen; 2024. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.112498. [CrossRef]

- Yiu, A.; Van Hemelrijck, M.; Garmo, H.; Holmberg, L. , Malmström, H., Lambe, M., Hammar, N., Walldius, G., Jungner, I.; Wulaningsih, W. Circulating uric acid levels and subsequent development of cancer in 493,281 individuals: findings from the AMORIS Study. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 42332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heckmann, C.M.; Paradisi, F. Looking back: a short history of the discovery of enzymes and how they became powerful chemical tools. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 6082–6102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rullo, R.; Cerchia, C.; Nasso, R.; Romanelli, V.; Vendittis, E.D.; Masullo, M.; Lavecchia, A. Novel reversible inhibitors of xanthine oxidase targeting the active site of the enzyme. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, S.N.; Korb-Wells, C.S.; Kannangara, D.R.; Smith, M.W.; Wang, N.; Roberts, D.M.; Graham, G.G.; Williams, K.M.; Day, R.O. Allopurinol hypersensitivity: a systematic review of all published cases, 1950–2012. Drug Saf. 2013, 36, 953–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, M.; Vuppalanchi, R.; Chalasani, N. Febuxostat-induced acute liver injury. Hepatology 2016, 63, 1047–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kataoka, H.; Yang, K.; Rock, K.L. The xanthine oxidase inhibitor Febuxostat reduces tissue uric acid content and inhibits injury-induced inflammation in the liver and lung. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015, 746, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, A.; Gresser, U. Side effects and interactions of the xanthine oxidase inhibitor febuxostat. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Abreu, M.F.S.; Wegermann, C.A.; Ceroullo, M.S.; Sant’Anna, I.G.M.; Lessa, R.C. Ten years milestones in xanthine oxidase inhibitors discovery: Febuxostat-based inhibitors trends, bifunctional derivatives, and automatized screening assays. Organics 2022, 3, 380–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, F.; Fernandes, E.; Roleira, F. Progress towards the discovery of xanthine oxidase inhibitors. Curr Med Chem. 2002, 9, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orhan, I.E.; Deniz, F.S. Natural products and extracts as xantine oxidase inhibitors - A hope for gout disease? Curr Pharm Des. 2021, 27, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Huang, G. The inhibitory activity of natural products to xanthine oxidase. Chem Biodivers. 2023, 20, e202300005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleh, J.; Machado, L. Rose of jericho: a word of caution. Oman Med J. 2012, 27, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zin, S.R.M.; Kassim, N.M.; Alshawsh, M.A.; Hashim, N.E.; Mohamed, Z. Biological activities of Anastatica hierochuntica L.: A systematic review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 91, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Xu, F.; Morikawa, T.; Ninomiya, K.; Matsuda, H. Anastatins A and B, new skeletal flavonoids with hepatoprotective activities from the desert plant Anastatica hierochuntica. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003, 13, 1045–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, M.; Morikawa, T.; Xu, F.; Ando, S.; Matsuda, H. (7R,8S) and (7S,8R) 8-5' linked neolignans from Egyptian herbal medicine Anastatica hierochuntica and inhibitory activities of lignans on nitric oxide production. Heterocycles 2003, 60, 1787–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlGamdi, N.; Mullen, W.; Crozier, A. Tea prepared from Anastatica hirerochuntica seeds contains a diversity of antioxidant flavonoids, chlorogenic acids and phenolic compounds. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Garawani, I.M.; Abd El-Gaber, A.S.; Algamdi, N.A.; Saeed, A.; Zhao, C.; Khattab, O.M.; AlAjmi, M.F.; Guo, Z.; Khalifa, S.A.M.; El-Seedi, H.R. In Vitro induction of apoptosis in isolated acute myeloid leukemia cells: The role of Anastatica hierochuntica methanolic Extract. Metabolites 2022, 12, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzouk, M.M.; Al-Nowaihi, A.S.M.; Kawashty, S.A.; Saleh, N.A.M. Chemosystematic studies on certain species of the family Brassicaceae (Cruciferae) in Egypt. Biochem System Ecol. 2010, 38, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, S.; Matsuda, H.; Oda, Y.; Nakamura, S.; Xu, F.; Yoshikawa, M. Melanogenesis inhibitors from the desert plant Anastatica hierochuntica in B16 melanoma cells. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010, 18, 2337–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enroth, C.; Eger, B.T.; Okamoto, K.; Nishino, T.; Nishino, T.; Pai, E.F. Crystal structures of bovine milk xanthine dehydrogenase and xanthine oxidase: Structure-based mechanism of conversion. Proc Natl Acad Sci. USA 2000, 97, 10723–10728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, Y.; Nakashima, Y.; Tsukamoto, S.; Kurohara, T.; Suzuki, M.; Sakae, Y.; Oda, M.; Okamoto, Y.; Suzuki, T. N+-C-H···O Hydrogen bonds in protein-ligand complexes. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, N.; Dhiman, P.; Khatkar, A. In silico design and synthesis of targeted rutin derivatives as xanthine oxidase inhibitors. BMC chem. 2019, 13, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Zhang, G.; Liao, Y.; Pan, J.; Gong, D. Dietary flavonoids as xanthine oxidase inhibitors: Structure–affinity and structure–activity relationships. J Agric Food Chem. 2015, 63, 7784–7794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.M.; Chen, C.S.; Chen, C.T.; Liang, Y.C.; Lin, J.K. Molecular modeling of flavonoids that inhibits xanthine oxidase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002, 294, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zhang, G.; Hu, Y.; Ma, Y. Effect of luteolin on xanthine oxidase: Inhibition kinetics and interaction mechanism merging with docking simulation. Food Chem 2013, 141, 3766–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.C.; Murugaiyah, V.; Chan, K.L. Flavonoids and phenylethanoid glycosides from Lippia nodiflora as promising antihyperuricemic agents and elucidation of their mechanism of action. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 176, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantsar, T.; Poso, A. Binding affinity via docking: fact and fiction. Molecules 2018, 23, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Ai, X.; Pan, F.; Zhou, N.; Zhao, L.; Cai, S.; Tang, X. Novel peptides with xanthine oxidase inhibitory activity identified from macadamia nuts: Integrated in silico and in vitro analysis. European Food Res Technol. 2022, 248, 2031–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Xu, M.; Gong, D.; Zhang, G. Mechanism of flavonoids inhibiting xanthine oxidase and alleviating hyperuricemia from structure–activity relationship and animal experiments: A review. Food Frontiers 2023, 4, 1643–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, A.; Li, J.; Rehman, A.U.; Kobun, R.; Llah, I.U.; Khan, I.; Althobaiti, F.; Albogami, S.; Usman, M.; Alharthi, F.; Soliman, M.M.; et al. Xanthine oxidase inhibitory study of eight structurally diverse phenolic compounds. Front Nutr. 2022, 9, 966557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, R.; Zhang, G.; Gong, D. Mechanistic insights into the inhibition of quercetin on xanthine oxidase. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018, 112, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, U.; Hudaib, M.; Issa, A.; Tawaha, K.; Bustanji, Y. Plant products and their inhibitory activity against xanthine oxidase. FARMACIA 2021, 69, 1042–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, A.; Seki, M.; Kobayashi, H. Inhibition of xanthine oxidase by flavonoids. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1999, 63, 1787–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.Y.; Li, Q.; Bi, K.S. Bioactive flavonoids in medicinal plants: Structure, activity and biological fate. Asian J Pharm Sci. 2018, 13, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, L.; Choudhari, Y.; Patel, P.; Gupta, G.D.; Singh, D.; Rosenholm, J.M.; Bansal, K.K.; Kurmi, B.D. . Advancement in solubilization approaches: A step towards bioavailability enhancement of poorly soluble drugs. Life 2023, 13, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.P.; Chen, C.C.; Huang, C.W.; Chang, Y.C. Evaluating molecular properties involved in transport of small molecules in stratum corneum: A quantitative structure-activity relationship for skin permeability. Molecules 2018, 23, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantinescu, T. , Lungu, C.N., Lung, I. Lipophilicity as a Central Component of Drug-Like Properties of Chalchones and Flavonoid Derivatives. Molecules 2019, 24, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Effinger, A.; O'Driscoll, C.M.; McAllister, M.; Fotaki, N. Impact of gastrointestinal disease states on oral drug absorption–implications for formulation design–a PEARRL review. , 71(4), pp.674-698. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2019, 71(4), 674–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basheer, L.; Kerem, Z. Interactions between CYP3A4 and dietary polyphenols. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015, 2015, 854015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.Y.; Koh, K.H.; Jeong, H. Isoform-specific regulation of cytochromes P450 expression by estradiol and progesterone. Drug Metab Dispos. 2013, 41, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sayed, M.; El-Sherif, F.; Elhassaneen, Y.; Abd El-Rahman, A. . Potential therapeutic effects of some Egyptian plant parts on hepatic toxicity induced by carbon tetrachloride in rats. Life Sci. J. 2012, 9, 3747–3755. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, P.; Eckert, A.O.; Schrey, A.K.; Preissner, R. ProTox-II: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W257–W263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Elella, F.; Ahmed, E.; Gavamukulya, Y. Determination of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, as well as in vitro cytotoxic activities of extracts of Anastatica hierochuntica (Kaff Maryam) against HeLa cell lines. J Medicinal Plants Res. 2016, 10, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammd, T.U.; Baker, R.K.; Al-Ameri, K.A.; Abd-Ulrazzaq, S.S. Cytotoxic effect of aqueous extract of Anastatica hierochuntica L. on AMN-3 cell line in vitro. Adv Life Sci Technol. 2015, 31, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.A.; Abul Farah, M.; Al-Hemaid, F.M.; Abou-Tarboush, F.M. In vitro cytotoxicity screening of wild plant extracts from Saudi Arabia on human breast adenocarcinoma cells. Genet Mol Res. 2014, 13, 3981–3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rameshbabu, S.; Messaoudi, S.A.; Alehaideb, Z.I.; Ali, M.S.; Venktraman, A.; Alajmi, H.; Al-Eidi, H.; Matou-Nasri, S. Anastatica hierochuntica (L.) methanolic and aqueous extracts exert antiproliferative effects through the induction of apoptosis in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Saudi Pharm J 2020, 28, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Md Zin, S.R.; Mohamed, Z.; Alshawsh, M.A.; Wong, W.F.; Kassim, N.M. Mutagenicity evaluation of Anastatica hierochuntica L. aqueous extract in vitro and in vivo. Exp Biol Med. 2018, 243, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filimonov, D.A.; Lagunin, A.; Gloriozova, T.A.; Rudik, A.V.; Druzhilovskii, D.S.; Pogodin, P.V.; Poroikov, V.V. Prediction of the biological activity spectra of organic compounds using the PASS online web resource. Chem Heterocyclic Comp. 2014, 50, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokce, M.; Guler, E.M. A. hierchuntica extract exacerbates genotoxic, cytotoxic, apoptotic and oxidant effects in B16F10 melanoma cells. Toxicon. 2021, 198, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajjar, D.; Kremb, S.; Sioud, S.; Emwas, A.H.; Voolstra, C.R.; Ravasi, T. Anti-cancer agents in Saudi Arabian herbals revealed by automated high-content imaging. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0177316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazeam, J.A.; El-Emam, S.Z. Middle Eastern plants with potent cytotoxic effect against lung cancer cells. J Med Food 2024, 27, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domańska, A.; Orzechowski, A.; Litwiniuk, A.; Kalisz, M.; Bik, W.; Baranowska-Bik, A. The beneficial role of natural endocrine disruptors: Phytoestrogens in Alzheimer’s disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021, 2021, 3961445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humfrey, C.D. Phytoestrogens and human health effects: weighing up the current evidence. Nat Toxins 1998, 6, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeriglio, A.; Trombetta, D.; Marcoccia, D.; Narciso, L.; Mantovani, A.; Lorenzetti, S. Intracellular distribution and biological effects of phytochemicals in a sex steroid- sensitive model of human prostate adenocarcinoma. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2014, 14, 1386–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Arrigo, G.; Gianquinto, E.; Rossetti, G.; Cruciani, G.; Lorenzetti, S.; Spyrakis, F. Binding of androgen-and estrogen-like flavonoids to their cognate (non) nuclear receptors: a comparison by computational prediction. Molecules 2021, 26, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.W.; Lee, J.H.; Cho, H.J.; Ha, Y.J.; Kang, E.H.; Shin, K.; Byun, S.S.; Lee, E.Y.; Song, Y.W.; Lee, Y.J. Influence of androgen deprivation therapy on serum urate levels in patients with prostate cancer: A retrospective observational study. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0209049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).