Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Notation (Symbols Only)

| Symbol | Type / Domain | Meaning / Assumptions |

| Ambient Hilbert geometry (“one room”) | ||

| Hilbert space | Common comparison space with inner product and norm | |

| Closed subspaces | Statistical (blueprint, sDoF) and physical (response, pDoF) arenas | |

| Closed subspaces | Alternative notation for (sector–neutral definitions) | |

| Projections | Orthogonal projectors onto , in the ambient inner product | |

| Linear map | Calibration / interchangeability map (blueprint → ideal response) | |

| Closed subspace | Coherent image of on the physical side (after closure) | |

| Projection | Orthogonal projector onto U | |

| SPD operator | Instrument weight; induces instrument inner product and norm | |

| Norm | Instrument norm on , associated with W | |

| States, channels, duals | ||

| Hilbert space | Finite–dimensional quantum system, typically | |

| Operator space | Matrices / bounded operators on | |

| State space | Density matrices with | |

| Operators | Quantum states in | |

| Linear map | Quantum channel (CPTP) or general linear update on | |

| Linear map | Blueprint update on ; DSFL pair is | |

| Linear map | Hilbert–Schmidt adjoint of | |

| Operator norm | Induced norm ; DSFL admissibility requires | |

| Operators | Kraus operators of a CPTP channel, | |

| Operator on | Gram operator ; controls via its largest eigenvalue | |

| Scalar | Largest eigenvalue of ; equals in finite dimension | |

| Scalar | DSFL gap | |

| Residual of sameness and defects | ||

| Vector | Statistical (blueprint, sDoF) state | |

| Vector | Physical (response, pDoF) state | |

| Vector in | Calibrated mismatch (defect, residual direction) | |

| , | Scalar | Residual of sameness: |

| Scalar | Generic notation for a DSFL residual (when no sector is specified) | |

| Nonnegative scalar | Residual magnitude, e.g. half–width in DSFL band tests | |

| Scalar | Total residual in a block–diagonal room (QM+TD+GR toy) | |

| Scalars | Sectoral residuals in QM, TD and GR calibrations | |

| Scalar | Correlation residual (inside–outside or bipartite) | |

| Frames, projectors, angles | ||

| Closed subspace | Measurement / reconstruction / constraint frame | |

| Projection | Orthogonal projector onto V (ambient inner product) | |

| Closed subspace | Spectral frame of observable A (after graph transport) | |

| Angle | Friedrichs angle; | |

| Scalar in | Overlap constant | |

| Closed subspace | Closed linear span of two frames , | |

| Variance and graph transport (when used) | ||

| Operator | Centered observable: | |

| Isomorphism | Graph–norm isomorphism | |

| Closed subspace | A–frame in after graph transport | |

| Nonnegative scalar | Standard deviation: | |

| Admissibility, DPI, and operators | ||

| Linear map | Statistical update (blueprint side) | |

| Linear map | Physical update (response side) | |

| Identity | Intertwining (coherent blueprint → coherent response) | |

| Operator inequality | Spectral DPI / nonexpansiveness in | |

| DSFL–admissible | Property | and (equivalently DPI for R) |

| Inequality | Data–processing inequality for the single observable R | |

| Two–loop dynamics and DSFL time | ||

| Trajectory in | Time–dependent residual | |

| Operator on | Immediate loop generator; selfadjoint, | |

| Operator kernel | Retarded, Loewner–positive memory kernel for | |

| Vector in | Remainder; | |

| Nonnegative scalar | Coercivity bound: | |

| Nonnegative scalar | Remainder bound in the Lyapunov inequality | |

| Nonnegative scalar | Instantaneous decay rate (envelope rate) | |

| Nonnegative scalar | Residual energy in time | |

| Scalar | DSFL time via ; unit–slope Lyapunov clock | |

| Nonnegative scalars | Sectoral Lyapunov rates in QM, TD, GR calibrations | |

| Causality and cone parameters (relay loop) | ||

| c | Speed constant | Instrument light–cone speed (cone front speed) |

| Semigroup on | Relay evolution; cone bound with margin | |

| Projection/localiser | Projection onto defects supported in region O | |

| Length/time scale | Cone sharpness in bounds of the form | |

| Cutoff | Ultraviolet regulator; typically | |

| Finite–dimensional quantum sector | ||

| Hilbert spaces | Local qubit / qudit spaces, typically , | |

| Hilbert space | Tensor product | |

| Density matrix | Bipartite state on | |

| Density matrices | Reduced states: , | |

| Density matrix | Bell state in the two–qubit sector | |

| Partial transpose | Transposition on subsystem B in a fixed basis | |

| Entanglement and correlation proxies | ||

| Scalar | Negativity: | |

| Scalar | Sandwiched Rényi divergence to product form | |

| Scalar | Trace distance to product: | |

| Scalar | DSFL correlation residual | |

| Bell / CHSH notation | ||

| Observables | Local dichotomic () observables on | |

| Observables | Local dichotomic () observables on | |

| C | Operator | CHSH operator |

| Scalar | CHSH value | |

| Scalar | Classical (local hidden–variable) CHSH value; | |

| Scalar | DSFL / quantum CHSH value; (Tsirelson bound) | |

| Thermodynamic and GR model worlds | ||

| L | Generator | Markov generator on a finite state space (TD block) |

| Probability vector | Classical distribution at time t; stationary distribution | |

| Scalar | TD residual | |

| Tensor | Einstein imbalance (GR toy) | |

| Scalar | GR residual | |

| Scalar | DSFL rate in GR toy, controlled by dominant quasi–normal modes | |

| Global / UV DSFL quantities | ||

| Scalar | Scale–resolved sectoral residual in sector at cutoff | |

| Scalar | Scale–resolved global residual | |

| Scalar | UV–limit sectoral residual in sector | |

| Scalar | UV–limit global residual | |

| Scalar | Scale–resolved DSFL rate in sector a at cutoff | |

| Scalar | UV–limit DSFL rate in sector a | |

| Scalar | Slowest sectoral rate at scale , | |

| Scalar | UV–limit slowest rate, | |

| Scalar | UV / global DSFL time: | |

| Scalar | Asymptotic Rsameness gap: (when it exists) | |

| Scalar | de Sitter / Kerr–de Sitter gap; positive QNM / energy–decay scale in GR models | |

| Scalar | Microscopic DSFL gap in a PPE–SABIM–gravity room (QG appendix) | |

| Sector label | Optional quantum–geometric sector in extended four–sector DSFL constructions | |

| Scrambling, Page time, and complexity | ||

| Scalar | DSFL scrambling time: minimal time/steps to reduce a residual by factor | |

| Scalar | DSFL Page–like time (inside/outside DSFL residuals equal, correlation residual peaked) | |

| Scalar | DSFL Lyapunov rate in simple toy models, | |

| Scalar | Entropy–response exponent, e.g. in the toy Page law | |

| Scalar | DSFL depth / complexity (Lyapunov depth or cumulative DSFL time) | |

| Scalar | Computational complexity (when used in conditional Susskind–type bounds) | |

| Scalar | Chaos / Lyapunov exponent in MSS OTOC bound[1] | |

| Scalar | Inverse temperature, | |

| Miscellaneous symbols | ||

| Norm | Ambient norm (context may indicate operator, Hilbert–Schmidt, or trace norm) | |

| Inner product | Ambient inner product | |

| Loewner order | Positive semidefinite operator: for all x | |

| Nonnegative scalar | Distance of x to subspace V in | |

1. Introduction

- Blueprints encode conditional statistics or target configurations (wave functions, probability measures, geometric data). They live in and need not carry their own dynamics; they say what an instrument is aiming to realise.

- Physical responses encode what an instrument or device actually outputs. They live in and are evaluated in a fixed instrument norm induced by W; they capture what is really delivered by the dynamics or measurement.

- Calibration is the deterministic map that realises blueprints as responses. The residual of sameness is the squared norm of this calibration mismatch and is the only scalar DSFL observable we use to talk about approach to equilibrium, contractivity, or locality.

2. Sector–Neutral DSFL Framework

- a calibrated room in which statistical blueprints and physical responses live side by side;

- a residual of sameness that measures calibration mismatch;

2.1. Structural Quantum Gravity

2.2. Room, Calibration, and Residual

- a Hilbert space ;

- a closed subspace of statistical degrees of freedom (sDoF, “blueprints”);

- a closed subspace of physical degrees of freedom (pDoF, “responses”);

- a bounded linear calibration map ;

- a bounded, selfadjoint, strictly positive instrument weight , inducing the inner product and norm

- (a)

- for all ;

- (b)

- if and only if .

2.3. Admissible Maps and a Residual Data–Processing Inequality

- (a)

- (calibration preservation)

- (b)

- (nonexpansiveness in the instrument norm)

- (i)

- is DSFL–admissible;

- (ii)

- for all one has the residual data–processing inequality

2.4. Rate–Bearing Feedback and the DSFL Clock

- (a)

- for each there exists a DSFL–admissible pair with ;

- (b)

-

the residual satisfies a Lyapunov inequalityfor some measurable rate function .

2.5. Relay and Cone Locality

3. Three Calibrations in One DSFL Room

3.1. Quantum Calibration (QM Sector)

3.2. Thermodynamic Calibration (TD Sector)

3.3. Gravitational Calibration (GR Sector)

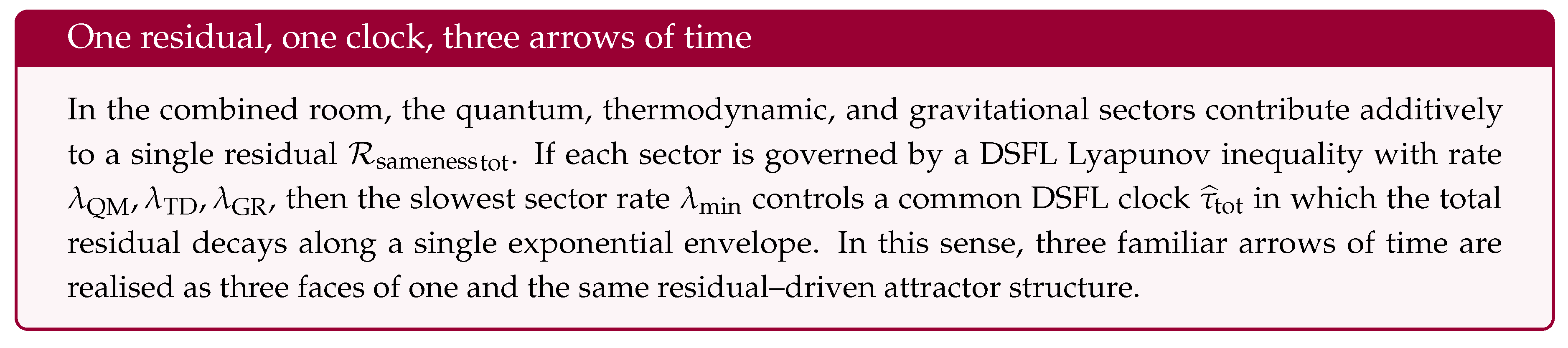

3.4. Putting Them in One Room: A Unification Theorem

4. Model–World Examples and Audits

4.1. Toy QM Calibration: Depolarising Qubit

4.2. Toy TD Calibration: Two–State Markov Chain

5. Spectral Representation of DSFL Dynamics (Summary)

5.1. Immediate Operator and Sameness Modes

- is bounded, selfadjoint, and nonnegative in ;

- is bounded in the form sense by a small function (for instance from subleading couplings or UV corrections).

5.2. Spectral DSFL Differential Inequality (Informal)

5.3. Finite–Dimensional Channel Case

6. Positioning and Relation to Prior Work

- a single observable in one comparison geometry, the residual of sameness , used in all three sectors and, in the UV master law of Section B, promoted to a global residual with a single asymptotic Rsameness gap;

- uncertainty and incompatibility (in the broader DSFL programme) recast as principal–angle remainders on a conserved norm, with commutators fixing only the numeric floors;

- collapse and nearest–point enforcement as the unique budget–preserving projections in that norm (sharp case);

- dimension–free stability envelopes driven by a single DPI that applies equally to quantum channels, Markov/Lindblad and Fokker–Planck flows, and linearised curvature–matter evolution; and

- a deterministic, rate–bearing law (DSFL) that makes locality, entropy production, near–horizon irreversibility, and (in the UV limit) the late–time tail of auditable rather than axiomatic, via explicit Lyapunov and cone bounds.

6.1. Geometry of Information: Angles, Projections, and Alternating Schemes

6.2. Data Processing, Entropy Production, and Lyapunov Structure

6.3. Uncertainty and Incompatibility: Variance, Entropic, and Geometric Viewpoints

6.4. Collapse, Instruments and POVMs (Quantum Calibration)

6.5. Locality, Cones, and Finite Speed

6.6. Contextuality, EPR/Bell, and Tsirelson Bounds (Quantum Test Sector)

6.7. Operator–Algebraic and Spectral Backdrop

6.8. Holography and Boundary Perspectives (Motivation Only)

6.9. Summary

7. Concluding Discussion and Outlook

7.1. What Has Been Established

7.2. Limitations and Open Issues

7.3. How the Framework Might Be Used or Falsified

7.4. Outlook

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

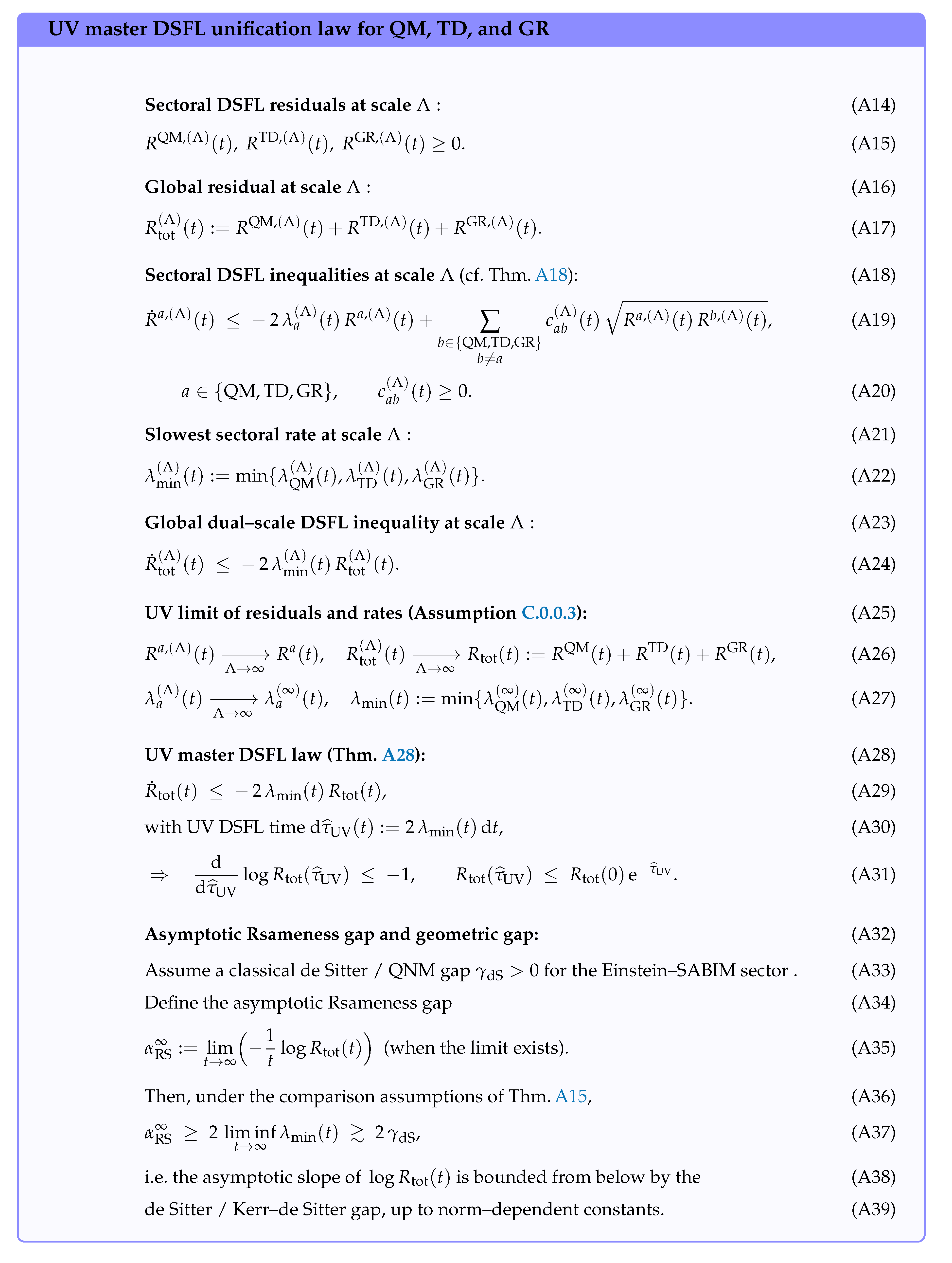

Appendix A. UV Master Inequality

Appendix A.1. Scale–Resolved Residuals and Assumptions

- (a)

-

(Weak coupling). There exists such that for all ,In particular, covers the uncoupled/block–diagonal case.

- (b)

-

(UV convergence of residuals and rates). For each sector there exist limiting functions and such that, for every ,We then define the limiting global residual and slowest rate by

Appendix A.2. Finite–Cutoff and UV Master Inequalities

Appendix A.3. DSFL Quantum–Gravity Completion

- (a)

-

Microscopic quantum DSFL room.A DSFL roomwith microscopic defect and microscopic residual satisfying a strictly positive DSFL gap

- (b)

-

Sectoral coarse–grainings at finite cutoff.For each UV cutoff and each sector there exists a DSFL roomand a DSFL–admissible coarse–graining such thatand there exist constants (independent of t) with

- (c)

-

UV stability of residuals and rates.The UV stability assumptions of Assumption C.0.0.3 hold: for each sector ,uniformly on compact time intervals, and the UV limiting global residualsatisfies the UV master DSFL inequality

- (d)

-

Einstein–SABIM gravitational sector.The GR sector is realised by an Einstein–SABIM DSFL room (Sections (d) and C.0.0.4), with residual , where is the Einstein residual, and the Einstein–SABIM PDE estimates provide a geometric DSFL gap comparable to a de Sitter / Kerr–de Sitter gap .

Appendix A.4. From Microscopic Gap to UV Rsameness Gap

- (i)

- The limiting slowest rate satisfies

- (ii)

-

Whenever the asymptotic Rsameness gapexists, it obeys the global lower bound

Appendix A.5. Interpretation

- the only genuinely quantised object is the microscopic DSFL room with gap ;

- thermodynamic and gravitational sectors are DSFL–admissible coarse–grainings and PDE reductions of this room;

- any such completion automatically inherits a single UV master residual whose late–time slope is fixed, up to constants, by and by the geometric GR gaps encoded in .

| Symbol | Type | Meaning / rôle in the DSFL law |

|---|---|---|

| Time and sectors | ||

| t | Scalar (time) | Physical time parameter along the evolution of the coupled QM+TD+GR system. |

| Sector label | Quantum sector (collapse/scrambling room; residual , rate ). | |

| Sector label | Thermodynamic sector (Markov / kinetic room; residual , rate ). | |

| Sector label | Gravitational sector (Einstein–SABIM room; residual , rate ). | |

| Label | Ultraviolet (UV) regime / limit; appears in , and in the UV DSFL time . | |

| a | Sector index | Generic sector label. In this paper we take to index the quantum, thermodynamic, and gravitational sectors, and write , , , etc. compactly. |

| ∈ | Membership symbol | Read as “is an element of”. For example, means that a is one of the three sector labels , , or . |

| Sectoral and global residuals (UV limit) | ||

| Scalar | Quantum DSFL residual at time t; collapse/scrambling mismatch in the quantum room. | |

| Scalar | Thermodynamic DSFL residual at time t; kinetic/TD mismatch (e.g. –type distance to equilibrium). | |

| Scalar | Gravitational DSFL residual at time t; Einstein–balance mismatch (norm of ). | |

| Scalar | Global residual of sameness at time t, defined by . Single scalar entering the unification and UV master equations. | |

| Sectoral contraction rates and slowest rate | ||

| Scalar | Quantum DSFL rate at time t; Lyapunov slope for (collapse / scrambling). | |

| Scalar | Thermodynamic DSFL rate at time t; Lyapunov slope for (mixing / transport). | |

| Scalar | Geometric DSFL rate at time t; Lyapunov slope for (ringdown / curvature relaxation). | |

| Scalar | Slowest sectoral rate at time t, . Appears in the global DSFL inequality and sets the effective arrow of time in UV DSFL time. | |

| DSFL time and master inequality | ||

| Scalar (time) | UV DSFL time. Defined by so that, in , the global residual satisfies the one–slope inequality , i.e. . | |

| Asymptotic Rsameness gap and Kerr–de Sitter data | ||

| Scalar | Asymptotic Rsameness gap, defined (when the limit exists) by . Measures the asymptotic exponential decay rate of the global mismatch. | |

| Scalar | Geometric de Sitter/Kerr–de Sitter gap: slowest decay rate from quasi–normal–mode (QNM) frequencies or geometric energy decay for linearised perturbations. The gap comparison theorems give , so the tail of carries (up to constants) the same information as the de Sitter gap. | |

| Scale–resolved / UV notation | ||

| Scalar (scale) | UV cutoff or resolution scale (e.g. inverse lattice spacing, frequency cutoff, or maximum energy) indexing scale–resolved DSFL rooms. | |

| Scalar | Scale–resolved sectoral residual at cutoff in sector . At fixed one has and . | |

| Scalar | Global residual at scale : sum of the three sectoral residuals. Obeys the scale–resolved master inequality . | |

| Scalar | Scale–resolved DSFL rate in sector a at cutoff ; appears in sectoral inequalities of the form . | |

| Scalar | Slowest sectoral rate at scale , ; controls the decay of via the scale–resolved master inequality. | |

| Scalar (nonnegative) | Scale– and time–dependent coupling coefficients between sectors a and b in the DSFL Lyapunov inequalities. Quantify cross–sector feed–in of residual via terms . | |

| Scalar | UV–limit sectoral rate in sector a, obtained as as . The limiting slowest rate enters the UV master inequality . | |

Appendix B. DSFL Unification Equation for QM, TD, GR and UV

Appendix B.1. Explaining the DSFL Equations for QM, TD, GR and UV

Scale–resolved sectoral and global residuals.

Appendix C. Sector Rooms and UV Master Law

Appendix D. Calibrations

Appendix D.1. Gravitational Two–Loop Lyapunov Law

- (i)

- Immediate loop. For each , is bounded, selfadjoint in , and there exists a measurable function such that

- (ii)

-

Positive memory kernel. For each , the kernel is bounded and selfadjoint in and satisfiesMoreover, is weakly measurable and for each finite t, so the Volterra term in (A57) is well defined.

- (iii)

- Small remainder. There exists a measurable function such that for all and all ,

- (a)

- Lyapunov inequality.For almost every ,

- (b)

- Exponential envelope under a uniform gap.If there exists such that for all , then for all ,

- (c)

-

Intrinsic DSFL time.On any interval where , define the gravitational DSFL clock byThen along the trajectory one hasi.e. in intrinsic DSFL time the semilogarithmic plot has slope at most .

Appendix E. Spectral representation of DSFL residual dynamics

Appendix E.1. DSFL room, defect, and residual

Appendix E.2. Two–loop DSFL evolution and immediate damping

- is the immediate (time–local) part, bounded, selfadjoint and nonnegative in the instrument inner product ;

- is a remainder term, typically lower order and small in the sense of a form bound (see below).

Appendix E.3. Spectral decomposition of the immediate operator

Appendix E.4. Spectral DSFL differential inequality

Appendix E.5. Scalar DSFL lemma and DSFL clock

Appendix E.6. Finite–dimensional channel case

- (a)

- .

- (b)

- Φ is DSFL–admissible (nonexpansive) iff , i.e. .

- (c)

- If for some , then for iterates and residuals one has

Appendix F. Model–World Derivations

Appendix F.1. Amplitude–Damping Channel

- (a)

- The Liouville superoperator of has spectrum , so the DSFL contraction factor on the traceless subspace in Hilbert–Schmidt norm is and the corresponding effective Lyapunov rate is .

- (b)

-

The residual sequence satisfies the spectral DSFL envelopewith equality (up to a constant prefactor) for generic initial states . Equivalently,so the semilogarithmic plot of versus k has asymptotic slope .

Appendix F.2. Depolarising qubit

Appendix F.3. Two–state Markov chain

Appendix G. DSFL Numerical Audits

Appendix H. DSFL Room, Admissibility, and Lyapunov Structure

Appendix H.1. Residual of sameness

Appendix H.2. Admissible Maps and DPI for R

Appendix H.3. Lyapunov Envelope and Intrinsic DSFL Time

- (a)

- For all ,

- (b)

-

On any interval where , the map is strictly increasing, and along the trajectory one hasIn particular, in DSFL time the semilogarithmic plot has slope at most , with equality for ideal evolutions.

Appendix I. Frames, Principal Angles, and Budget Sharing

Appendix J. Core DSFL Structural Lemmas

Appendix J.1. Residual Positivity and Data–Processing

- (a)

- for all ;

- (b)

- if and only if .

- (i)

- is DSFL–admissible;

- (ii)

- for all one has

Appendix J.2. Spectral Characterisation in Finite Dimension

Appendix J.3. Scalar Lyapunov Lemma and DSFL Clock

Appendix J.4. Global Multi–Sector Lyapunov Inequality

- are measurable rate functions;

- are measurable couplings with ;

-

there exists such that for all t,where .

- (a)

- (Einstein–SABIM gap).In a Kerr–de Sitter–type playground the Einstein–SABIM PDE estimates yield a de Sitter / quasinormal–mode gap , in the sense that local energy for linearised perturbations decays at least like in a suitable graph norm.

- (b)

-

(Gravitational DSFL gap).The GR sector is realised as a DSFL room with residual and satisfies a Lyapunov inequalityfor some geometric DSFL gap .

- (c)

-

(Global residual and asymptotic Rsameness gap).The global residual is finite for all , and the asymptotic Rsameness gapexists.

Appendix K. Two–Qubit Bell Setup

Appendix K.1. Hilbert Space, Basis, and Pauli Operators

Appendix K.2. CHSH Observables and Bell Operator

Appendix K.3. Classical CHSH Bound

Appendix K.4. Tsirelson Bound and Bell State Saturation

Appendix L. DSFL Nonlocality in the Calibrated CHSH Sector

- (a)

- (b)

- There exist DSFL–admissible data (the Bell state and local observables ) such that , saturating Tsirelson’s bound in the DSFL room.[68]

- (c)

References

- Maldacena, J.; Shenker, S.H.; Stanford, D. A bound on chaos. Journal of High Energy Physics 2016, 2016, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information; Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Watrous, J. The Theory of Quantum Information; Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Wilde, M.M. Quantum Information Theory, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Horodecki, R.; Horodecki, P.; Horodecki, M.; Horodecki, K. Quantum Entanglement. Reviews of Modern Physics 2009, 81, 865–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, D.A.; Peres, Y.; Wilmer, E.L. Markov Chains and Mixing Times; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, 2009; With contributions by James G. Propp and others. [Google Scholar]

- Villani, C. Hypocoercivity; Memoirs of the American Mathematical Society, American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, 2009; Volume 202. [Google Scholar]

- Carlen, E.A.; Maas, J. Gradient flow and entropy inequalities for quantum Markov semigroups with detailed balance. Journal of Functional Analysis 2017, 273, 1810–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, R.M. General Relativity; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Wald, R.M. Quantum Field Theory in Curved Spacetime and the Problem of Gravity; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, 1994; Also published as Quantum Field Theory in Curved Spacetime and Black Hole Thermodynamics. [Google Scholar]

- Lieb, E.H.; Robinson, D.W. The finite group velocity of quantum spin systems. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1972, 28, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, M.B. Lieb–Schultz–Mattis in higher dimensions. Physical Review B 2004, 69, 104431, [cond-mat/0305505]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravyi, S.; Hastings, M.B.; Verstraete, F. Lieb–Robinson bounds and the generation of correlations and topological quantum order. Physical Review Letters 2006, 97, 050401, [quant-ph/0603121]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nachtergaele, B.; Sims, R. Lieb–Robinson bounds and the exponential clustering theorem. Communications in Mathematical Physics 2006, 265, 119–130, [math-ph/0506030]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T. Perturbation Theory for Linear Operators, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.; Simon, B. Methods of Modern Mathematical Physics II: Fourier Analysis, Self-Adjointness; Academic Press: New York, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, N.; Cavalcanti, D.; Pironio, S.; Scarani, V.; Wehner, S. Bell nonlocality. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2014, 86, 419–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohya, M.; Petz, D. Quantum Entropy and Its Use; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bakry, D.; Gentil, I.; Ledoux, M. Analysis and Geometry of Markov Diffusion Operators; Springer: Cham, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hawking, S.W. Particle creation by black holes. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1975, 43, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, D.N. Information in black hole radiation. Physical Review Letters 1993, 71, 3743–3746, [hep-th/9306083]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, E.; Cardoso, V.; Starinets, A.O. Quasinormal modes of black holes and black branes. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2009, 26, 163001, [arXiv:gr-qc/0905.2975]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konoplya, R.A.; Zhidenko, A. Quasinormal modes of black holes: From astrophysics to string theory. Reviews of Modern Physics 2011, arXiv:gr-qc/1102.4014]83, 793–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafermos, M.; Holzegel, G.; Rodnianski, I. Title of the Article. Journal Name Year, Volume, Pages. Add full details here.

- Maldacena, J.M. The Large N Limit of Superconformal Field Theories and Supergravity. Advances in Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 1998, 2, 231–252, [hep-th/9711200]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Takayanagi, T. Holographic Derivation of Entanglement Entropy from AdS/CFT. Physical Review Letters 2006, 96, 181602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raamsdonk, M.V. Building up spacetime with quantum entanglement. General Relativity and Gravitation 2010, 42, 2323–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, P.; Preskill, J. Black holes as mirrors: quantum information in random subsystems. Journal of High Energy Physics 2007, 2007, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekino, Y.; Susskind, L. Fast Scramblers. Journal of High Energy Physics 2008, 2008, 065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblad, G. Completely Positive Maps and Entropy Inequalities. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1975, 40, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblad, G. On the generators of quantum dynamical semigroups. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1976, 48, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlmann, A. Relative Entropy and the Wigner–Yanase–Dyson Skew Information. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1977, 54, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petz, D. Monotonicity of quantum relative entropy revisited. Quantum Information & Computation 2003, 3, 134–140, [arXiv:quant-ph/quant-ph/0209053]. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, R. Matrix Analysis; Vol. 169, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer: New York, 1997. [CrossRef]

- Gorini, V.; Kossakowski, A.; Sudarshan, E.C.G. Completely positive dynamical semigroups of N-level systems. Journal of Mathematical Physics 1976, 17, 821–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblad, G. On the generators of quantum dynamical semigroups. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1976, 48, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollands, S.; Wald, R.M. Quantum fields in curved spacetime. Reviews of Modern Physics 2008, 80, 1083–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spohn, H. Entropy production for quantum dynamical semigroups. Journal of Mathematical Physics 1978, 19, 1227–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueders, G. Title Placeholder. Journal Placeholder 1951, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Gleason, A.M. Measures on the Closed Subspaces of a Hilbert Space. Journal of Mathematics and Mechanics 1957, 6, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, P.; Lahti, P.; Werner, R.F. Measurement Uncertainty Relations. Journal of Mathematical Physics 2014, 55, 042111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, P.; Lahti, P.; Werner, R.F. Colloquium: Quantum Root-Mean-Square Error and Measurement Uncertainty Relations. Reviews of Modern Physics 2014, 86, 1261–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringström, H. The Cauchy Problem in General Relativity; European Mathematical Society: Zürich, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, C. Essai sur la géométrie à n dimensions. Bulletin de la Société Mathématique de France 1875. Classic introduction of principal (canonical) angles; bibliographic details vary by edition.

- Friedrichs, K. On Certain Inequalities and Characteristic Angles. Annals of Mathematics 1937. Hilbert-space formulation of the angle between subspaces (Friedrichs angle).

- Davis, C.; Kahan, W.M. The Rotation of Eigenvectors by a Perturbation. SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis 1970, 7, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J. Mathematische Grundlagen der Quantenmechanik; Springer: Berlin, 1932. English translation by R. T. Beyer: Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics, Princeton University Press, 1955.

- Halperin, I. The Product of Projection Operators. Acta Scientiarum Mathematicarum (Szeged) 1962, 23, 96–99. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, F. The method of alternating orthogonal projections. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 1965, 118, 272–276. [Google Scholar]

- Bauschke, H.H.; Borwein, J.M. On Projection Algorithms for Solving Convex Feasibility Problems. SIAM Review 1996, 38, 367–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, F.; Hundal, H. The Rate of Convergence for the Method of Alternating Projections. Journal of Approximation Theory 2006, 141, 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Heisenberg, W. Über den anschaulichen Inhalt der quantentheoretischen Kinematik und Mechanik. Zeitschrift für Physik 1927, 43, 172–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, H.P. The Uncertainty Principle. Physical Review 1929, 34, 163–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, E. Zum Heisenbergschen Unschärfeprinzip. Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Physikalisch-mathematische Klasse 1930, pp. 296–303.

- Hirschman, I. I., J. A Note on Entropy. American Journal of Mathematics 1957, 79, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckner, W. Inequalities in Fourier Analysis. Annals of Mathematics 1975, 102, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białynicki-Birula, I.; Mycielski, J. Uncertainty Relations for Information Entropy in Wave Mechanics. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1975, 44, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maassen, H.; Uffink, J.B.M. Generalized Entropic Uncertainty Relations. Physical Review Letters 1988, 60, 1103–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, M. Universally valid reformulation of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle on noise and disturbance in measurement. Physical Review A 2003, 67, 042105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naimark, M.A. Spectral functions of a symmetric operator. Izvestiya Akademii Nauk SSSR. Seriya Matematicheskaya 1940, 4, 277–318. [in Russian]; English transl. Amer. Math. Soc. Transl. (2) 16 (1960), 103–239.

- Stinespring, W.F. Positive functions on C*-algebras. Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 1955, 6, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haag, R. Local Quantum Physics: Fields, Particles, Algebras, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisognano, J.J.; Wichmann, E.H. On the Duality Condition for a Hermitian Scalar Field. Journal of Mathematical Physics 1975, 16, 985–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratteli, O.; Robinson, D.W. Operator Algebras and Quantum Statistical Mechanics I, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takesaki, M. Theory of Operator Algebras II; Vol. 125, Encyclopaedia of Mathematical Sciences, Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Kochen, S.; Specker, E.P. The Problem of Hidden Variables in Quantum Mechanics. Journal of Mathematics and Mechanics 1967, 17, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J. On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen paradox. Physics 1964, 1, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirelson, B.S. Quantum generalizations of Bell’s inequality. Letters in Mathematical Physics 1980, 4, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J. Mathematische Grundlagen der Quantenmechanik; Springer: Berlin, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, M.H. Linear transformations in Hilbert space. III. Operational methods and group theory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1930, 16, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J. Die Eindeutigkeit der Schrödingerschen Operatoren. Mathematische Annalen 1931, 104, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakry, D.; Émery, M. Diffusions hypercontractives. In Séminaire de probabilités XIX 1983/84; Azéma, J., Meyer, P.A., Yor, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, 1985; Volume 1123, Lecture Notes in Mathematics; pp. 177–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cercignani, C.; Illner, R.; Pulvirenti, M. The Mathematical Theory of Dilute Gases; Vol. 106, Applied Mathematical Sciences, Springer: New York, 1994. [CrossRef]

- Mouhot, C.; Neumann, L. Quantitative perturbative study of convergence to equilibrium for collisional kinetic models in the torus. Nonlinearity 2006, 19, 969–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, D.; Klainerman, S. The Global Nonlinear Stability of the Minkowski Space; Princeton Mathematical Series; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, 1993; Volume 41. [Google Scholar]

- Dafermos, M.; Rodnianski, I. Decay for solutions of the wave equation on Kerr exterior spacetimes I: The cases |a|≪M or axisymmetry. arXiv preprint 2010, arXiv:1010.5132. [Google Scholar]

- Dafermos, M.; Holzegel, G.; Rodnianski, I. The Linear Stability of the Schwarzschild Solution to Gravitational Perturbations. Acta Mathematica 2019, 222, 1–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintz, P.; Vasy, A. The Global Non-Linear Stability of the Kerr–de Sitter Family of Black Holes. Acta Mathematica 2018, 220, 1–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, C. Hypocoercivity; Number 950 in Memoirs of the American Mathematical Society, American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Björck, Å.; Golub, G.H. Numerical methods for computing angles between linear subspaces. Mathematics of Computation 1973, 27, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauser, J.F.; Horne, M.A.; Shimony, A.; Holt, R.A. Proposed Experiment to Test Local Hidden-Variable Theories. Physical Review Letters 1969, 23, 880–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).