Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

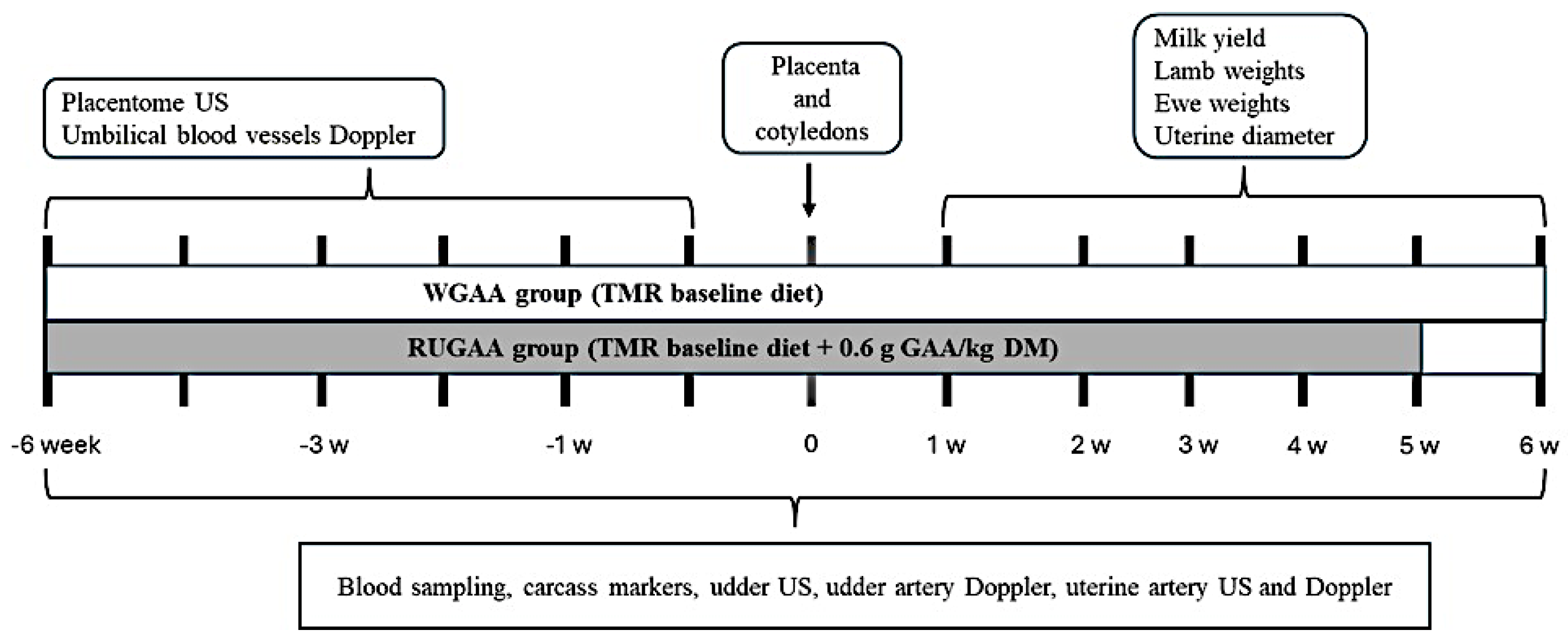

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location, Animals, Pre-Experimental Conditions, and Management

2.2. Experimental Design and TMR Diet Intake

2.3. Lambing and Lamb Weaning Management

2.4. Measurements of Carcass Markers and Ewe Weight Changes Postpartum

2.5. Ultrasonography Evaluation in Late Pregnancy

2.5.1. Uterine Artery Diameter and Hemodynamic Parameters

2.5.2. Placentome Growth

2.5.3. Umbilical Vascular Development

2.5.4. Umbilical Artery Hemodynamics

2.6. Placenta and Cotyledon Traits Measured at Lambing

2.7. Postpartum Uterine Involution

2.8. Mammary Gland and Artery Development

2.8.1. Udder Volume

2.8.2. B-Mode Ultrasound – Mammary Gland and Pulsed Doppler – Udder Artery

2.9. Ewes’ Milk Yield and Lamb Growth During the Suckling Period

2.10. Blood Sampling and Biochemical Marker Analysis

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

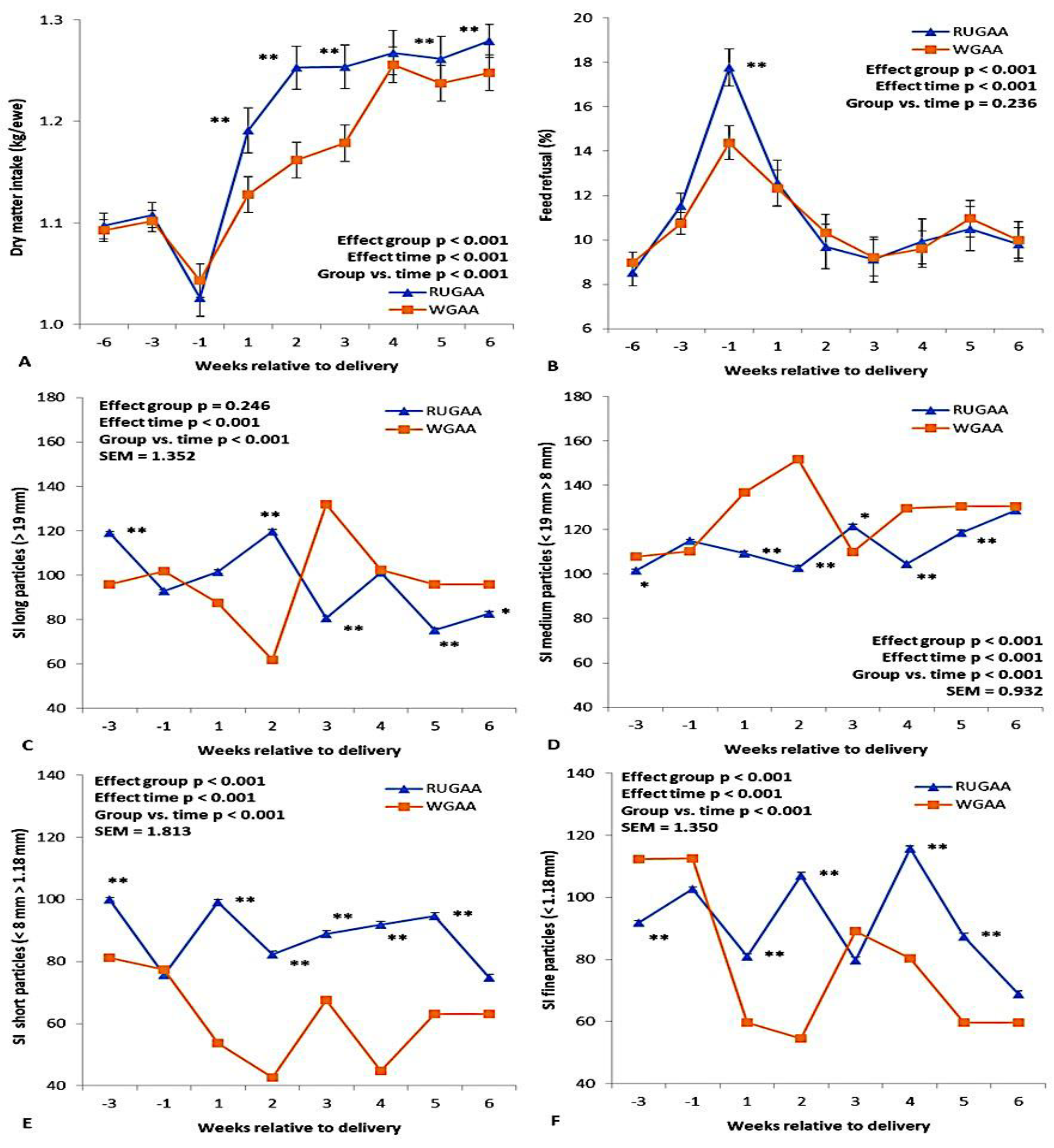

3.1. TMR Diet Intake and Selective Feeding Behavior

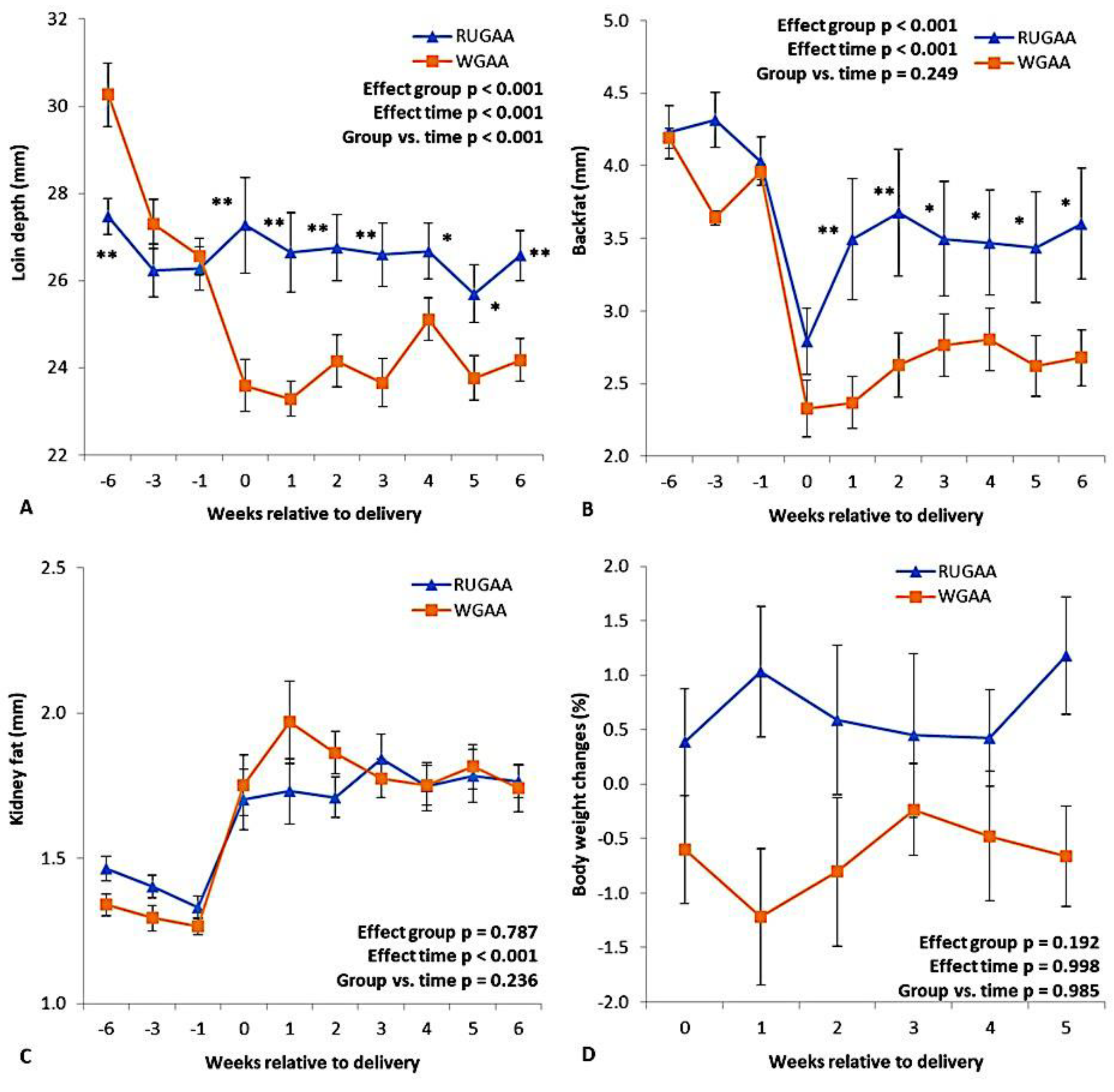

3.2. Carcass Marker Dynamics and Ewe Body Weight Changes Postpartum

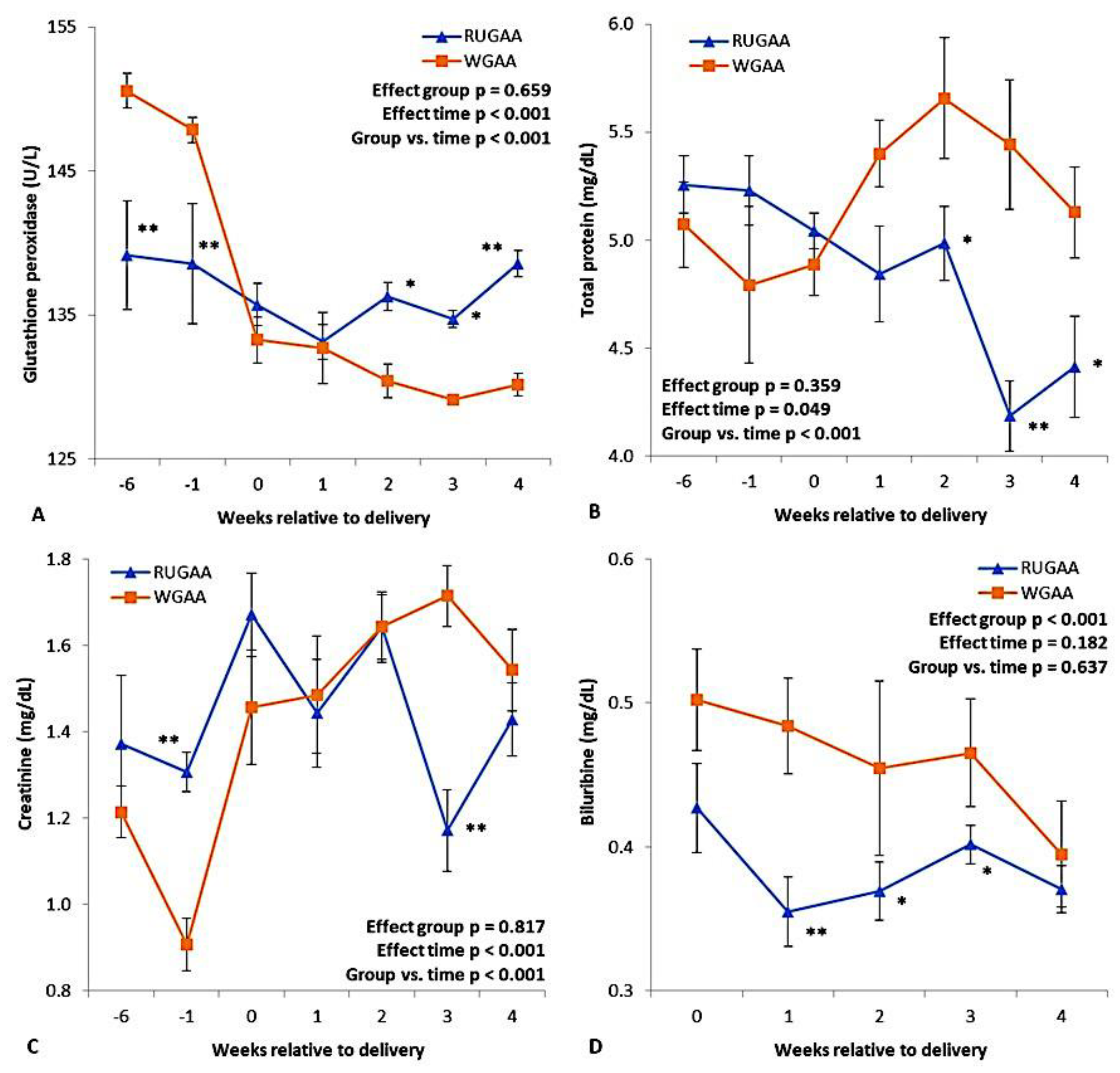

3.3. Peripheral Metabolites, GPx, and BHB

3.4. Maternal-Fetal Communication System

3.4.1. Umbilical Vascular Development and Umbilical Artery Hemodynamics

3.4.2. Placentome Growth, Placenta Weight, and Fetal Cotyledonary Outcome

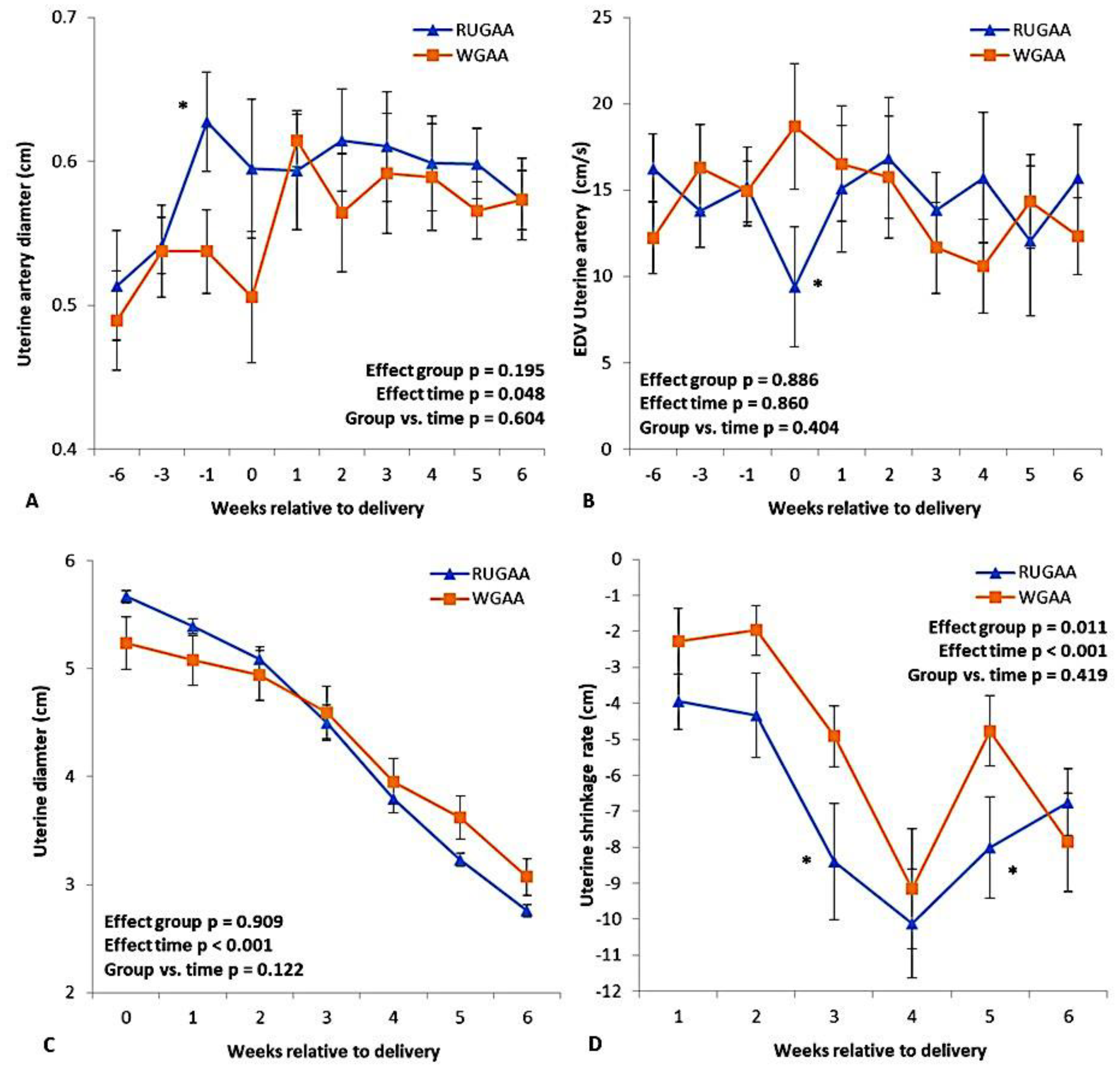

3.4.3. Uterine Artery Size and Hemodynamics

3.5. Postpartum Uterine Lumen Involution

3.6. Mammary Gland Development, Udder Volume, and Milk Yield Outcomes Postpartum

3.7. Lamb Growth Outcome During the Suckling Period

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Code Availability

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meikle, A.; et al. Influences of nutrition and metabolism on reproduction of the female ruminant. Anim. Reprod. 2018, 15 (Suppl 1), 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halloran, K.M.; Stenhouse, C. Key biochemical pathways during pregnancy in livestock: mechanisms regulating uterine and placental development and function. Reprod. Fertil. 2025, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemley, C. Fetal programming: maternal-fetal interactions and postnatal performance. Clin. Theriogenol. 2020, 12, 252–267. [Google Scholar]

- Limesand, S.W.; et al. Impact of thermal stress on placental function and fetal physiology. Anim. Reprod. 2018, 15 (Suppl 1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simões, J.; Margatho, G. Metabolic Periparturient Diseases in Small Ruminants: An Update. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.; et al. Characteristics of Holstein cows predisposed to ketosis during the post-partum transition period. Vet. Med. Sci. 2023, 9, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; et al. An overview of the development of perinatal stress-induced fatty liver and therapeutic options in dairy cows. Stress Biology 2025, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniamuthan, S.; Manimaran, A.; Kumaresan, A.; Wankhade, P.R.; Karuthadurai, T.; Sivaram, M.; Rajendran, D. Biochemical Indicators of Energy Balance in Blood and Other Secretions of Dairy Cattle: A Review. Agric. Rev. 2025, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsampasi, B.; et al. Nutritional strategies to alleviate stress and improve welfare in dairy ruminants. Animals 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; et al. Comparing responses of dairy cows to short-term and long-term heat stress in climate-controlled chambers. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 2346–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loor, J.J.; et al. Physiological impact of amino acids during heat stress in ruminants. Anim. Front. 2023, 13, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsampasi, B.; et al. Effects of Rumen-Protected Methionine, Choline, and Betaine Supplementation on Ewes’ Pregnancy and Reproductive Outcomes. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uztimür, M.; Gazioğlu, A.; Yilmaz, Ö. Changes in free amino acid profile in goats with pregnancy toxemia. Vet. Res. Commun. 2024, 48, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Burghardt, R.C.; Wu, G.; Johnson, G.A.; Spencer, T.E.; Bazer, F.W. Select nutrients in the ovine uterine lumen. VII. Effects of arginine, leucine, glutamine, and glucose on trophectoderm cell signaling, proliferation, and migration. Biol. Reprod. 2011, 84, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Wu, G.; Spencer, T.E.; Johnson, G.A.; Li, X.; Bazer, F.W. Select nutrients in the ovine uterine lumen. I. Amino acids, glucose, and ions in uterine lumenal flushings of cyclic and pregnant ewes. Biol. Reprod. 2009, 80, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yao, J.; Sun, X.; Liu, S.; Martin, G.B. Amino acids in the nutrition and production of sheep and goats. In Amino Acids in Nutrition and Health: Amino Acids in the Nutrition of Companion, Zoo and Farm Animals; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkacemi, L.; Nelson, D.M.; Desai, M.; Ross, M.G. Maternal undernutrition influences placental-fetal development. Biol. Reprod. 2010, 83(3), 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saevre, C.B.; Caton, J.S.; Luther, J.S.; Meyer, A.M.; Dhuyvetter, D.V.; Musser, R.E.; Schauer, C.S. Effects of rumen-protected arginine supplementation on ewe serum-amino-acid concentration, circulating progesterone, and ovarian blood flow. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 89, 103. [Google Scholar]

- Lassala, A.; Bazer, F.W.; Cudd, T.A.; Datta, S.; Keisler, D.H.; Satterfield, M.C.; Spencer, T.E.; Wu, G. Parenteral administration of L-arginine enhances fetal survival and growth in sheep carrying multiple fetuses. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciascia, Q.L.; van der Linden, D.S.; Sales, F.A.; Wards, N.J.; Blair, H.T.; Pacheco, D.; McCoard, S.A. Parenteral administration of l-arginine to twin-bearing Romney ewes during late pregnancy is associated with reduced milk somatic cell count during early lactation. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 3071–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, B.; Wu, H.; Zha, X.; Elsabagh, M.; Zhao, J.; Shu, G. Maternal N-carbamylglutamate and L-arginine supplementations improve foetal jejunal oxidation resistance, integrity and immune function in malnutrition sheep during pregnancy. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 23, 989–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sherbiny, H.R.; et al. Exogenous L-arginine administration improves uterine vascular perfusion, uteroplacental thickness, steroid concentrations and nitric oxide levels in pregnant buffaloes under subtropical conditions. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2022, 57, 1493–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallet, J.L.; Miles, J.R.; Rempel, L.A. Effect of creatine supplementation during the last week of gestation on birth intervals, stillbirth, and preweaning mortality in pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 2122–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellery, S.J.; LaRosa, D.A.; Kett, M.M.; Della Gatta, P.A.; Snow, R.J.; Walker, D.W.; Dickinson, H. Dietary creatine supplementation during pregnancy: a study on the effects of creatine supplementation on creatine homeostasis and renal excretory function in spiny mice. Amino Acids 2016, 48, 1819–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, N.; Stenhouse, C.; Halloran, K.M.; Moses, R.M.; Seo, H.; Burghardt, R.C.; Bazer, F.W. Creatine metabolism at the uterine–placental interface throughout gestation in sheep. Biol. Reprod. 2023, 109(1), 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.T.; Kelly, S.B.; Snow, R.J.; Walker, D.W.; Ellery, S.J.; Galinsky, R. Assessing creatine supplementation for neuroprotection against perinatal hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy: a systematic review of perinatal and adult pre-clinical studies. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihatsch, W.A.; Stahl, B.; Braun, U. The umbilical cord creatine flux and time course of human milk creatine across lactation. Nutrients 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedeljkovic, D.; Ostojic, S.M. Dietary exposure to creatine-precursor amino acids in the general population. Amino Acids 2025, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiriwardhana, M.; Bertolo, R.F. Guanidinoacetic acid supplementation: A narrative review of its metabolism and effects in swine and poultry. Front. Anim. Sci. 2022, 3, 972868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.A.; Scholtz, E.L.; Chenier, T.S. The nitric oxide system in equine reproduction: current status and future directions. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2015, 35, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, S.M.; Mastronardi, C.; Walczewska, A.; Karanth, S.; Rettori, V.; Yu, W.H. The role of nitric oxide in reproduction. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 1999, 32, 1367–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speer, H.F.; Pearl, K.A.; Titgemeyer, E.C. Relative bioavailability of guanidinoacetic acid delivered ruminally or abomasally to cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giraldi, G.C.; Wolschick, G.J.; Signor, M.H.; Lago, R.V.P.; de Souza Muniz, A.L.; Draszevski, T.M.R.; Balzan, M.M.; Wagner, R.; da Silva, A.S. Effects of dietary guanidinoacetic acid on the performance, rumen fermentation, metabolism, and meat of confined steers. Animals 2024, 14, 2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Wang, J.; Ye, B.; Yi, X.; Abudukelimu, A.; Wu, H.; Zhou, Z. Guanidinoacetic acid and methionine supplementation improve the growth performance of beef cattle via regulating the antioxidant levels and protein and lipid metabolisms in serum and liver. Antioxidants 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xue, C.; Lang, J.; Pei, C.; Liu, Q. Effect of rumen-protected guanidinoacetic acid provision as a dietary supplement on the growth, slaughter performance, and meat quality in Simmental bulls. Meat Sci. 2025, 109889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Du, Z.; Fan, X.; Qin, L.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q. Effect of guanidinoacetic acid on production performance, serum biochemistry, meat quality and rumen fermentation in Hu sheep. Animals 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yimamu, M.; Ma, C.; Pan, J.; Wang, C.; Cai, W.; Yang, K. Dietary guanidinoacetic acid supplementation improves rumen metabolism, duodenal nutrient flux, and growth performance in lambs. Front. Vet. Sci. 12, 1528861. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Mo, X.; Zeng, W.; Ye, Z.; Liu, M. Effects of guanidinoacetic acid supplementation on growth performance, serum biochemical parameters, immune function, and antioxidant capacity in Xinjiang Hu sheep. Front. Anim. Sci. 2025, 6, 1639519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA FEEDAP Panel; Bampidis, V.; Azimonti, G.; Bastos, M.L.; Christensen, H.; Dusemund, B.; Fasmon Durjava, M.; Kouba, M.; Lopez-Alonso, M.; Lopez Puente, S.; et al. Scientific opinion on the safety and efficacy of a feed additive consisting of guanidinoacetic acid for all animal species (Alzchem Trostberg GmbH). EFSA J. 2022, 20, 7269. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L.C.O.; Matos, E.M.A.; Santos, M.M.; Detmann, E.; Sampaio, C.B.; Sancler-Silva, Y.F.R.; Rennó, L.N.; Serão, N.V.L.; Paulino, P.V.R.; Resende, T.L.; et al. Dietary guanidinoacetic acid as arginine spare molecule for beef cows at late gestation: Effects on cow’s performance and metabolism, and offspring growth and development. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2024, 315, 116047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.C.; Cavalcanti, C.M.; Conde, A.J.H.; Alves, B.V.F.; Cesar, L.F.B.; de Sena, J.N.; Miguel, Y.H.; Fernandes, C.C.L.; Alves, J.P.M.; Teixeira, D.Í.A.; et al. Short supply of high levels of guanidinoacetic acid alters ovarian artery flow and improves intraovarian blood perfusion area associated with follicular growth in sheep. Animals 2025, 15, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Research Council (NRC). Nutrient Requirements of Small Ruminants: Sheep, Goats, Cervids, and New World Camelids; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kononoff, P.J.; Heinrichs, A.J.; Buckmaster, D.R. Modification of the Penn State forage and total mixed ration particle separator and the effects of moisture content on its measurements. J. Dairy Sci. 2003, 86, 1858–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, C.; Armentano, L.E. Effect of quantity, quality, and length of alfalfa hay on selective consumption by dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2003, 86, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Martinez, M.A.; et al. Developing equations for predicting internal body fat in Pelibuey sheep using ultrasound measurements. Small Rumin. Res. 2020, 183, 106031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; et al. Effects of dietary inclusion of tannin-rich sericea lespedeza hay on relationships among linear body measurements, body condition score, body mass indexes, and performance of growing alpine doelings and katahdin ewe lambs. Animals 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, T.; et al. Differential appearance of placentomes and expression of prostaglandin H synthase type 2 in placentome subtypes after betamethasone treatment of sheep late in gestation. Placenta 2011, 32, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ababneh, M.M.; Degefa, T. Ultrasonic assessment of puerperal uterine involution in Balady goats. J. Vet. Med. A Physiol. Pathol. Clin. Med. 2005, 52, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslin, E.; et al. Mammary gland structures are not affected by an increased growth rate of yearling ewes post-weaning but are associated with growth rates of singletons. Animals 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntemka, A.; Tsakmakidis, I.; Boscos, C.; Theodoridis, A.; Kiossis, E. The role of ewes’ udder health on echotexture and blood flow changes during the dry and lactation periods. Animals 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celi, P.; Di Trana, A.; Claps, S. Effects of perinatal nutrition on lactational performance, metabolic and hormonal profiles of dairy goats and respective kids. Small Rumin. Res. 2008, 79, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkestani, L.; et al. Effect of corn and millet silage and their particle size on feed intake, digestibility, rumen parameters, and feed intake behavior in Kermani sheep. J. Livest. Sci. Technol. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, R.C.A.; et al. Effects of cutting height and bacterial inoculant on corn silage aerobic stability and nutrient digestibility by sheep. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2020, 49, e20190231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.P.; et al. Synthesis of guanidinoacetate and creatine from amino acids by rat pancreas. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; et al. Effects of propylene glycol on negative energy balance of postpartum dairy cows. Animals 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sammad, A.; et al. Major nutritional metabolic alterations influencing the reproductive system of postpartum dairy cows. Metabolites 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.P.; et al. Compensation response to hepatic gluconeogenesis via β-hydroxybutyrylation of FBP1 and PCK1 in dairy cows. Anim. Res. One Health 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.; et al. Metabolic evaluation of dairy cows submitted to three different strategies to decrease the effects of negative energy balance in early postpartum. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2011, 31, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.B.B.; et al. Impact of body condition on postpartum features in Morada Nova sheep. Semina: Ciênc. Agrar. 2016, 37, 1581–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, C.M.; et al. Impact of parity on carcase and metabolic markers associated with oxidative stress during uterine involution in periparturient goat. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 22, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, F.; et al. The hindgut microbiome contributes to host oxidative stress in postpartum dairy cows by affecting glutathione synthesis process. Microbiome 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q.; et al. Short-term feed restriction induces inflammation and an antioxidant response via cystathionine-β-synthase and glutathione peroxidases in ruminal epithelium from Angus steers. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulková, K.; Illek, J.; Kadek, R. Glutathione redox state, glutathione peroxidase activity and selenium concentration in periparturient dairy cows, and their relation with negative energy balance. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 2020, 29, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Píšťková, K. , Illek, J., & Kadek, R. (2019). Determination of antioxidant indices in dairy cows during the periparturient period. Acta Veterinaria Brno, 2019, 88, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Dunière, L.; et al. Changes in digestive microbiota, rumen fermentations and oxidative stress around parturition are alleviated by live yeast feed supplementation to gestating ewes. J. Fungi 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, L.P.; et al. Role of the placenta in developmental programming: observations from models using large animals. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2023, 257, 107322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redifer, C.A.; Wichman, L.G.; Rathert-Williams, A.R.; Meyer, A.M. Effects of late gestational nutrient restriction on uterine artery blood flow, placental size, and cotyledonary mRNA expression in primiparous beef females. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Yang, X. A review of roles of uterine artery Doppler in pregnancy complications. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 813343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vonnahme, K.A.; et al. Effect of morphology on placentome size, vascularity, and vasoreactivity in late pregnant sheep. Biol. Reprod. 2008, 79, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toschi, P.; Baratta, M. Ruminant placental adaptation in early maternal undernutrition: An overview. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 755034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaiges, G.; et al. Comparison of color Doppler uterine artery indices in a population at high risk for adverse outcome at 24 weeks' gestation. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 21, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, U.; et al. Fetal umbilical vascular response to chronic reductions in uteroplacental blood flow in late-term sheep. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 187, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erichsen, C.; et al. Increasing the understanding of nutrient transport capacity of the ovine placentome. Animals 2024, 14, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; et al. Placental adaptations in growth restriction. Nutrients 2015, 7, 360–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, L.P.; et al. Animal models of placental angiogenesis. Placenta 2005, 26, 689–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D.S.; et al. The effect of a reversible period of adverse intrauterine conditions during late gestation on fetal and placental weight and placentome distribution in sheep. Placenta 2002, 23, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, L.M.; et al. Methylation demand and homocysteine metabolism: effects of dietary provision of creatine and guanidinoacetate. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 281, E1095–E1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardalan, M.; et al. Effects of guanidinoacetic acid supplementation on nitrogen retention and methionine flux in cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 99, skab172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, B.D.; et al. Rumen-protected methionine supplementation during the transition period under artificially induced heat stress: Effects on cow-calf performance. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 8654–8669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouvêa, V.N.; et al. Methionine supply during mid-gestation modulates the bovine placental mTOR pathway, nutrient transporters, and offspring birth weight in a sex-specific manner. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unadkat, S.V.; et al. Association between homocysteine and coronary artery disease—trend over time and across the regions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Egypt. Heart J. 2024, 76, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubowski, H.; Witucki, Ł. Homocysteine metabolites, endothelial dysfunction, and cardiovascular disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, D.; et al. Mechanism of homocysteine-mediated endothelial injury and its consequences for atherosclerosis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 9, 1109445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arutjunyan, A.V.; et al. Imbalance of angiogenic and growth factors in placenta in maternal hyperhomocysteinemia. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2023, 88, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, C.A.; et al. Postpartum uterine involution in sheep: histoarchitecture and changes in endometrial gene expression. Reproduction 2003, 125, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayder, M.; Ali, A. Factors affecting the postpartum uterine involution and luteal function of sheep in the subtropics. Small Rumin. Res. 2008, 79, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmetwally, M.; Bollwein, H. Uterine blood flow in sheep and goats during the peri-parturient period assessed by transrectal Doppler sonography. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2017, 176, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madbouly, H.; et al. Determination of the impacts of supplemental dietary curcumin on post-partum uterine involution using pulsed-wave doppler ultrasonography in Zaraibi goat. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heppelmann, M.; et al. The effect of metritis and subclinical hypocalcemia on uterine involution in dairy cows evaluated by sonomicrometry. J. Reprod. Dev. 2015, 61, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafrah, H.A.; Alotaibi, M.F. The effect of extracellular ATP on rat uterine contraction from different gestational stages and its possible mechanisms of action. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2017, 28, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, M. Changes in expression of P2X7 receptors in rat myometrium at different gestational stages and the mechanism of ATP-induced uterine contraction. Life sciences, 2018, 199, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.J.; et al. Guanidine acetic acid exhibited greater growth performance in younger (13–30 kg) than in older (30–50 kg) lambs under high-concentrate feedlotting pattern. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 954675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Hao, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Zhang, J. Effects of guanidinoacetic acid and betaine on growth performance, energy and nitrogen metabolism, and rumen microbial protein synthesis in lambs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2022, 292, 115402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; et al. Effect of enhanced uterine involution on reproductive performance in multiparous ewes. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2025, 60, e70044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Guo, G.; Huo, W.; Xia, C.; Liu, Q. Effects of guanidinoacetic acid supplementation on lactation performance, nutrient digestion and rumen fermentation in Holstein dairy cows. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103(3), 1522–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zang, C.; Pan, J.; Ma, C.; Wang, C.; Li, X.; Yang, K. Effects of dietary guanidinoacetic acid on growth performance, guanidinoacetic acid absorption and creatine metabolism of lambs. PLoS ONE 2022, 17(3), e0264864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nørgaard, J.V.; Nielsen, M.O.; Theil, P.K.; Sørensen, M.T.; Safayi, S.; Sejrsen, K. Development of mammary glands of fat sheep submitted to restricted feeding during late pregnancy. Small Rumin. Res. 2008, 76(3), 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo Paffetti, M.; Cárcamo, J.; Arias-Darraz, L.; Alvear, C.; Ojeda, J. Effect of type of pregnancy on transcriptional and plasma metabolic response in sheep and its further effect on progeny lambs. Animals 2020, 10(12), 2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadsell, D.L.; Olea, W.; Wei, J.; Fiorotto, M.L.; Matsunami, R.K.; Engler, D.A.; Collier, R.J. Developmental regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis and function in the mouse mammary gland during a prolonged lactation cycle. Physiol. Genomics 2011, 43(6), 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadsell, D.L.; Torres, D.; George, J.; Capuco, A.V.; Ellis, S.E.; Fiorotto, M.L. Changes in secretory cell turnover, and mitochondrial oxidative damage in the mouse mammary gland during a single prolonged lactation cycle suggest the possibility of accelerated cellular aging. Exp. Gerontol. 2006, 41, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favorit, V.; Hood, W.R.; Kavazis, A.N.; Skibiel, A.L. Graduate student literature review: Mitochondrial adaptations across lactation and their molecular regulation in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 10415–10425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lérias, J.R.; Hernández-Castellano, L.E.; Suárez-Trujillo, A.; Castro, N.; Pourlis, A.; Almeida, A.M. The mammary gland in small ruminants: major morphological and functional events underlying milk production–a review. J. Dairy Res. 2014, 81, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.M.; Bislev, S.L.; Bendixen, E.; Almeida, A.M. The mammary gland in domestic ruminants: A systems biology perspective. J. Proteomics 2013, 94, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; van Baal, J.; Ma, L.; Gao, X.; Dijkstra, J.; Bu, D. MRCKα is a novel regulator of prolactin-induced lactogenesis in bovine mammary epithelial cells. Anim. Nutr. 2022, 10, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepper, M.S.; Baetens, D.; Mandriota, S.J.; Di Sanza, C.; Oikemus, S.; Lane, T.F.; Iruela-Arispe, M.L. Regulation of VEGF and VEGF receptor expression in the rodent mammary gland during pregnancy, lactation, and involution. Dev. Dyn. 2000, 218, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovey, R.C.; Goldhar, A.S.; Baffi, J.; Vonderhaar, B.K. Transcriptional regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in epithelial and stromal cells during mouse mammary gland development. Mol. Endocrinol. 2001, 15, 819–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbagianni, M.S.; Gouletsou, P.G.; Valasi, I.; Petridis, I.G.; Giannenas, I.; Fthenakis, G.C. Ultrasonographic findings in the ovine udder during lactogenesis in healthy ewes or ewes with pregnancy toxaemia. J. Dairy Res. 2015, 82, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.A.C.C.; Camacho, L.E.; Lemley, C.O.; Hallford, D.M.; Swanson, K.C.; Vonnahme, K.A. Effects of nutrient restriction and subsequent realimentation in pregnant beef cows: Maternal endocrine profile, umbilical hemodynamics, and mammary gland development and hemodynamics. Theriogenology 2022, 191, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.A.; Knight, C.H.; Cameron, G.G.; Foster, M.A. In-vivo studies of mammary development in the goat using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Reproduction 1990, 89, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collier, R.J.; Bauman, D.E. Triennial Lactation Symposium/BOLFA: Historical perspectives of lactation biology in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 95, 5639–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Attributes | TMR diet | |

| Late Pregnancy | Early Lactation | |

| Ingredient, g/kg of DM | ||

| Corn silage | 700 | 700 |

| Ground corn grain | 140 | 60 |

| Soybean meal | 40 | 140 |

| Wheat bran | 100 | 90 |

| Mineral mixture * | 20 | 20 |

| Chemical fraction | ||

| Dry matter, g/kg as-fed basis | 551.6 | 553.3 |

| Crude protein, g/kg of DM | 98.4 | 133.3 |

| Ether extract, g/kg of DM | 33.0 | 31.3 |

| Ash, g/kg of DM | 59.1 | 64.8 |

| Neutral-detergent fiber, g/kg of DM | 493.7 | 491.8 |

| Acid-detergent fiber, g/kg of DM | 233.9 | 236.1 |

| Non-fibrous carbohydrates, g/kg of DM | 333.1 | 429.4 |

| Attributes | Group | P-value | ||||

| WGAA | RUGAA | SEM | Group | Time | G x T | |

| Dry matter intake, %/BW* | 2.3 | 2.4 | 0.011 | 0.325 | < 0.001 | 0.121 |

| Ewes body weight changes | ||||||

| Delivery, kg | 48.2 | 49.9 | 2.484 | 0.747 | - | - |

| Weaning, kg | 47.9 | 50.3 | 2.401 | 0.632 | - | - |

| Average weight changes, kg | -0.3 | 0.4 | 0.539 | 0.537 | - | - |

| Total weight change from delivery, % | -0.7 | 1.2 | 1.192 | 0.461 | - | - |

| Energy metabolism | ||||||

| Glucose, mg/dL | 63.7 | 59.8 | 1.236 | 0.032 | < 0.001 | 0.222 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL | 53.2 | 53.7 | 1.220 | 0.931 | < 0.001 | 0.839 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 18.4 | 17.3 | 0.781 | 0.221 | < 0.001 | 0.316 |

| BHB, mmol/L | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.011 | 0.864 | 0.872 | 0.763 |

| Proteins | ||||||

| Albumin, mg/dL | 2.6 | 2.3 | 0.049 | 0.002 | 0.133 | 0.426 |

| Globulin, mg/dL | 2.7 | 2.4 | 0.090 | 0.039 | 0.024 | 0.047 |

| Kidney injury | ||||||

| Urea, mg/dL | 24.8 | 27.3 | 0.999 | 0.068 | < 0.001 | 0.824 |

| Liver injury | ||||||

| Albumin/globulin ratio | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.048 | 0.759 | 0.059 | 0.134 |

| GOT, U/L | 76.6 | 81.2 | 1.877 | 0.503 | 0.001 | 0.110 |

| GPT, U/L | 16.3 | 16.0 | 0.455 | 0.535 | 0.283 | 0.404 |

| Attributes | Group | P-value | ||||

| WGAA | RUGAA | SEM | Group | Time | G x T | |

| Umbilical vascular development | ||||||

| Artery diameter, cm | 7.2 | 7.4 | 0.164 | 0.351 | < 0.001 | 0.425 |

| Vein diameter, cm | 5.6 | 5.9 | 0.142 | 0.157 | < 0.001 | 0.631 |

| Total vascular area, cm2 | 135.1 | 145.3 | 6.297 | 0.211 | < 0.001 | 0.435 |

| Umbilical artery hemodynamic | ||||||

| Peak systolic velocity, cm/s | 48.0 | 50.3 | 0.540 | 0.004 | < 0.001 | 0.001 |

| End-diastolic velocity, cm/s | 24.1 | 22.9 | 1.089 | 0.505 | 0.720 | 0.463 |

| Placentome | ||||||

| Placentome diameter, cm | 2.1 | 2.2 | 0.030 | 0.413 | 0.868 | 0.034 |

| Reproductive features at delivery | ||||||

| Day of pregnancy, days | 147 | 146 | 0.241 | 0.335 | - | - |

| Placenta weight, g | 485.7 | 542.9 | 47.29 | 0.646 | - | - |

| Placental efficiency ratio* | 9.6 | 7.9 | 0.699 | 0.248 | - | - |

| Total cotyledon weight, g | 179.0 | 146.5 | 14.75 | 0.175 | - | - |

| No of cotyledons, n | 72.1 | 61.1 | 4.283 | 0.175 | - | - |

| Total cotyledon surface area, mm2 | 7589.2 | 4941.3 | 536.6 | 0.008 | - | - |

| Cotyledon efficiency ratio** | 593.0 | 843.8 | 58.65 | 0.024 | - | - |

| Attributes | Cotyledon Subtype | ||||

| A | B | C | D | SEM | |

| Average cotyledon weight, g | |||||

| WGAA | 1.9a | 2.8b | 3.7cA | 2.4d | 0.109 |

| RUGAA | 1.9a | 2.6ab | 3.1bB | 2.0a | 0.134 |

| Cotyledon surface area, mm2 | |||||

| WGAA | 89.7a | 125.0bA | 92.1aA | 96.5aA | 3.190 |

| RUGAA | 80.3 | 87.9B | 76.1B | 78.9B | 2.572 |

| Attributes | Group | P-value | ||||

| WGAA | RUGAA | SEM | Group | Time | G x T | |

| Mammary gland artery | ||||||

| Diameter, mm | 57.5 | 55.9 | 0.594 | 0.019 | < 0.001 | 0.306 |

| Peak systolic velocity, cm/s | 40.7 | 41.2 | 0.351 | 0.444 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| End-diastolic velocity, cm/s | 20.1 | 20.1 | 0.348 | 0.595 | < 0.001 | 0.048 |

| Udder trait and milk yield | ||||||

| Udder volume, cm3 | 3716.9 | 3537.3 | 100.6 | 0.134 | < 0.001 | 0.993 |

| Milk yield, kg/day | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.022 | 0.002 | < 0.001 | 0.799 |

| Attributes | Group | P-value | ||||||

| WGAA | RUGAA | SEM | Group | Time | Sex | G x T | G x S | |

| Body weight at lambing, kg | 4.4 | 3.6 | 0.216 | 0.043 | - | 0.567 | - | 0.127 |

| Body weight at weaning, kg | 14.4 | 12.6 | 0.764 | 0.369 | - | 0.731 | - | 0.253 |

| Daily weight gain, g/day | 222.2 | 200.0 | 16.23 | 0.391 | 0.018 | 0.474 | 0.949 | 0.488 |

| Total weight gain from delivery, % | 227.3 | 250.0 | 9.760 | 0.039 | < 0.001 | 0.069 | 0.967 | 0.488 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).