Submitted:

19 November 2024

Posted:

20 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

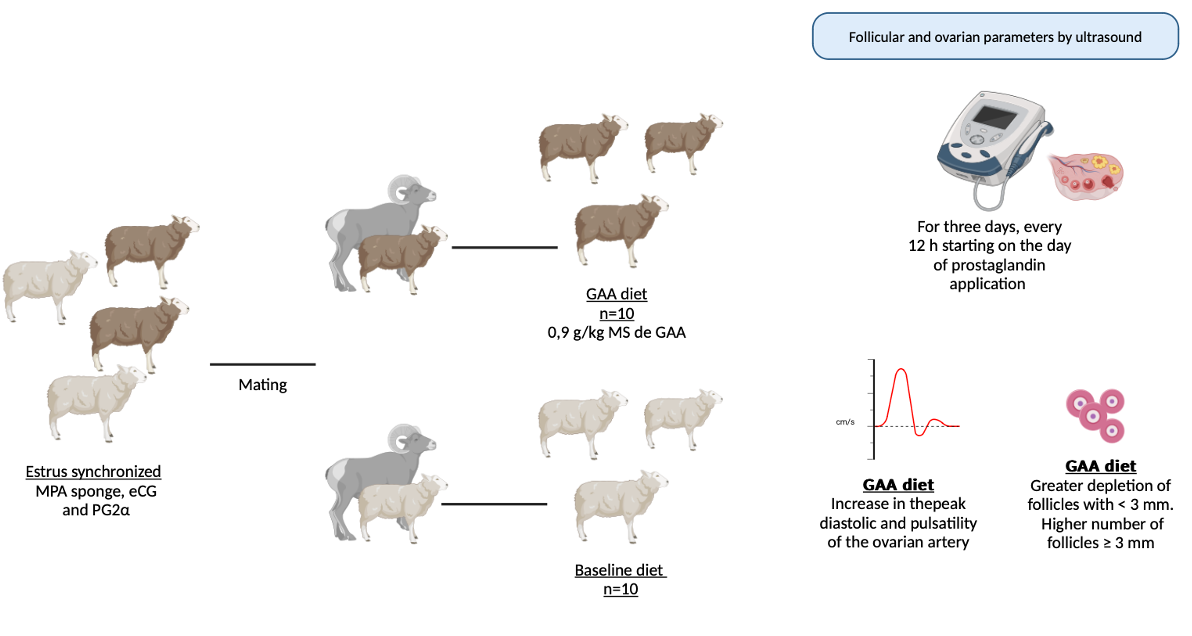

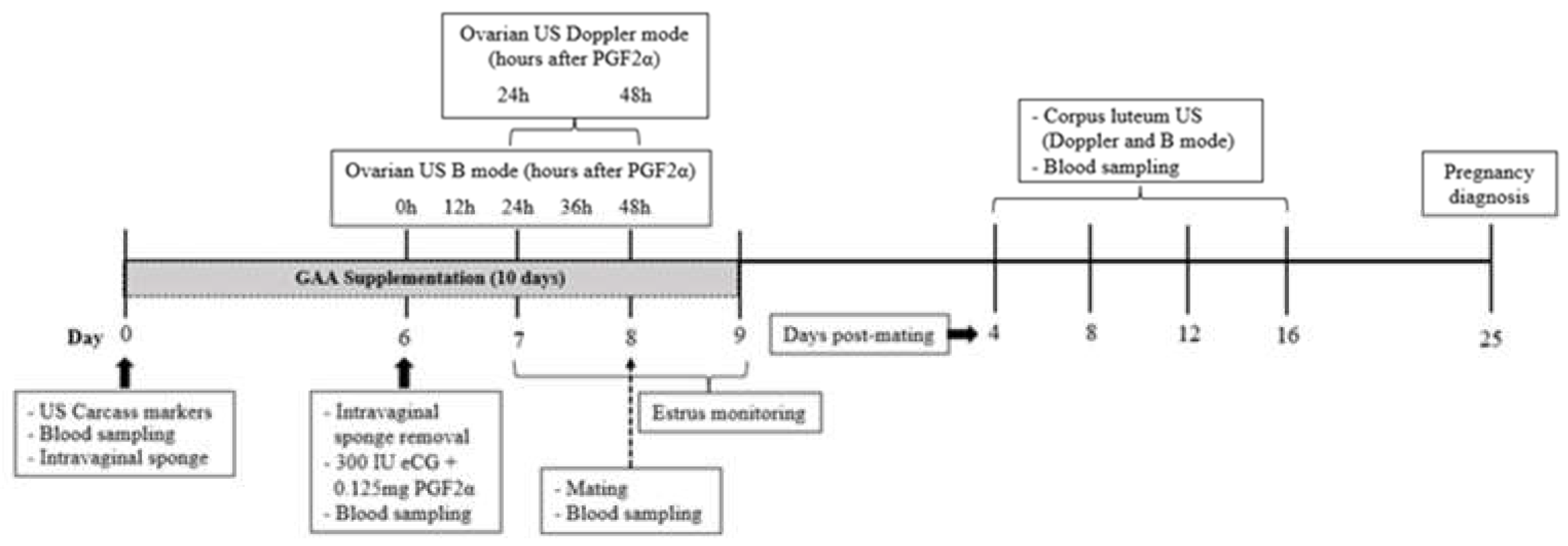

2.1. Location, Animals, Pre-Experimental Conditions, and Experimental Design

2.2. Assessment of Ovarian Blood Flow and Intraovarian Blood Perfusion Area

2.3. Follicular Dynamics, Corpus Luteum Growth, and Blood Perfusion Area

2.4. Blood Sampling and Metabolite Assays

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

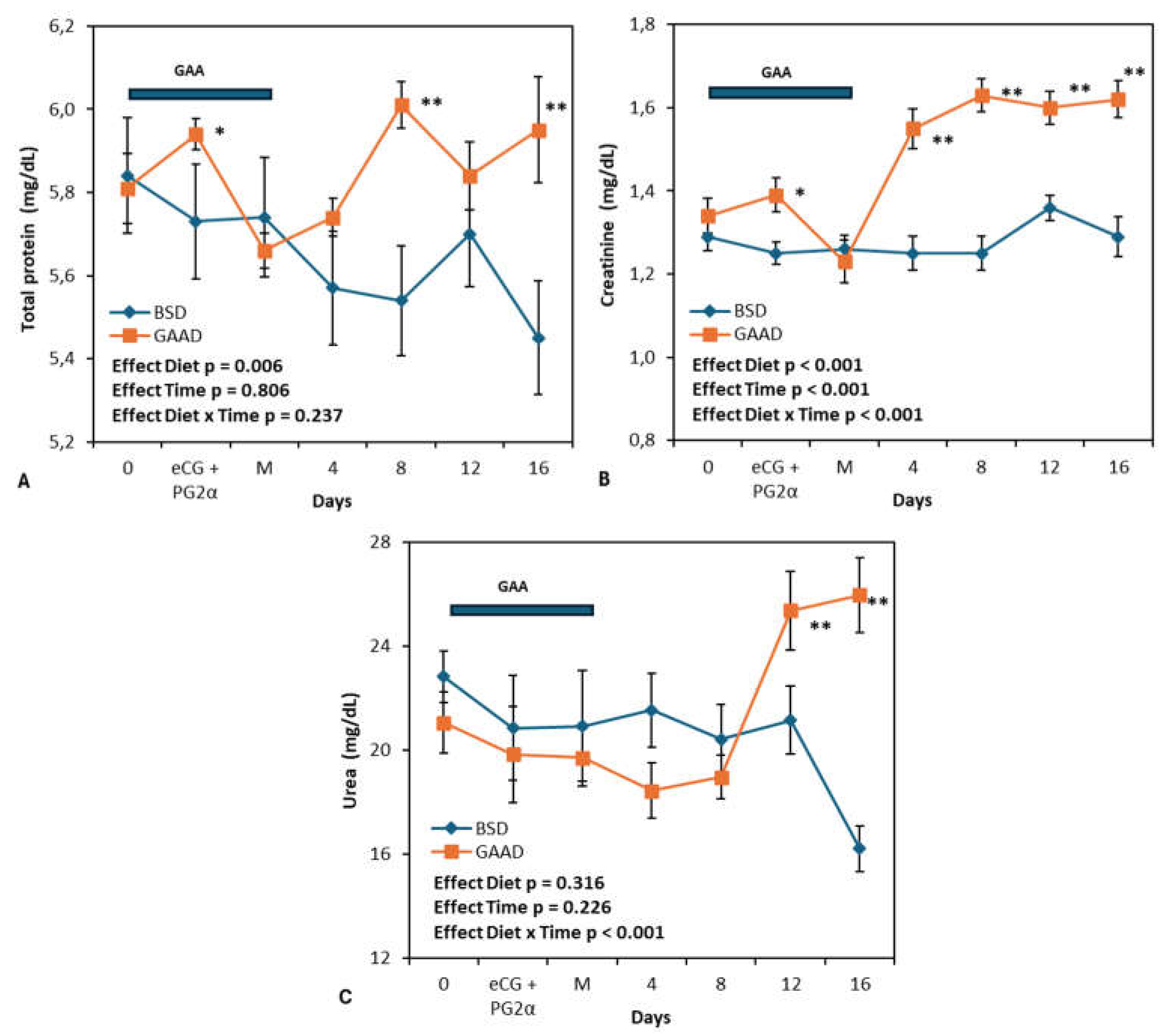

3.1. Feeding Response and Peripheral Metabolite Levels

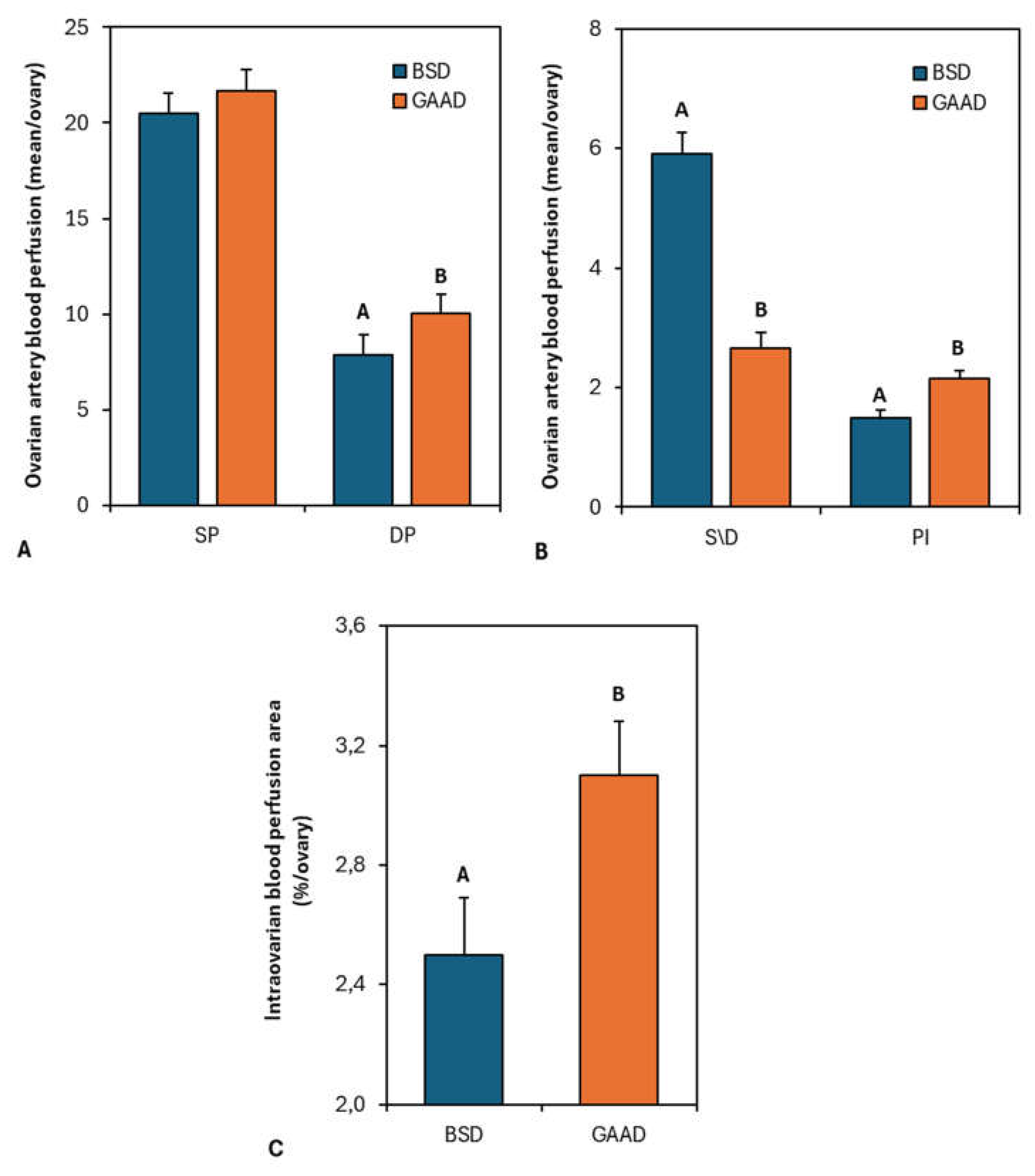

3.2. Ovarian Artery Blood Flow and Intraovarian Blood Perfusion Area

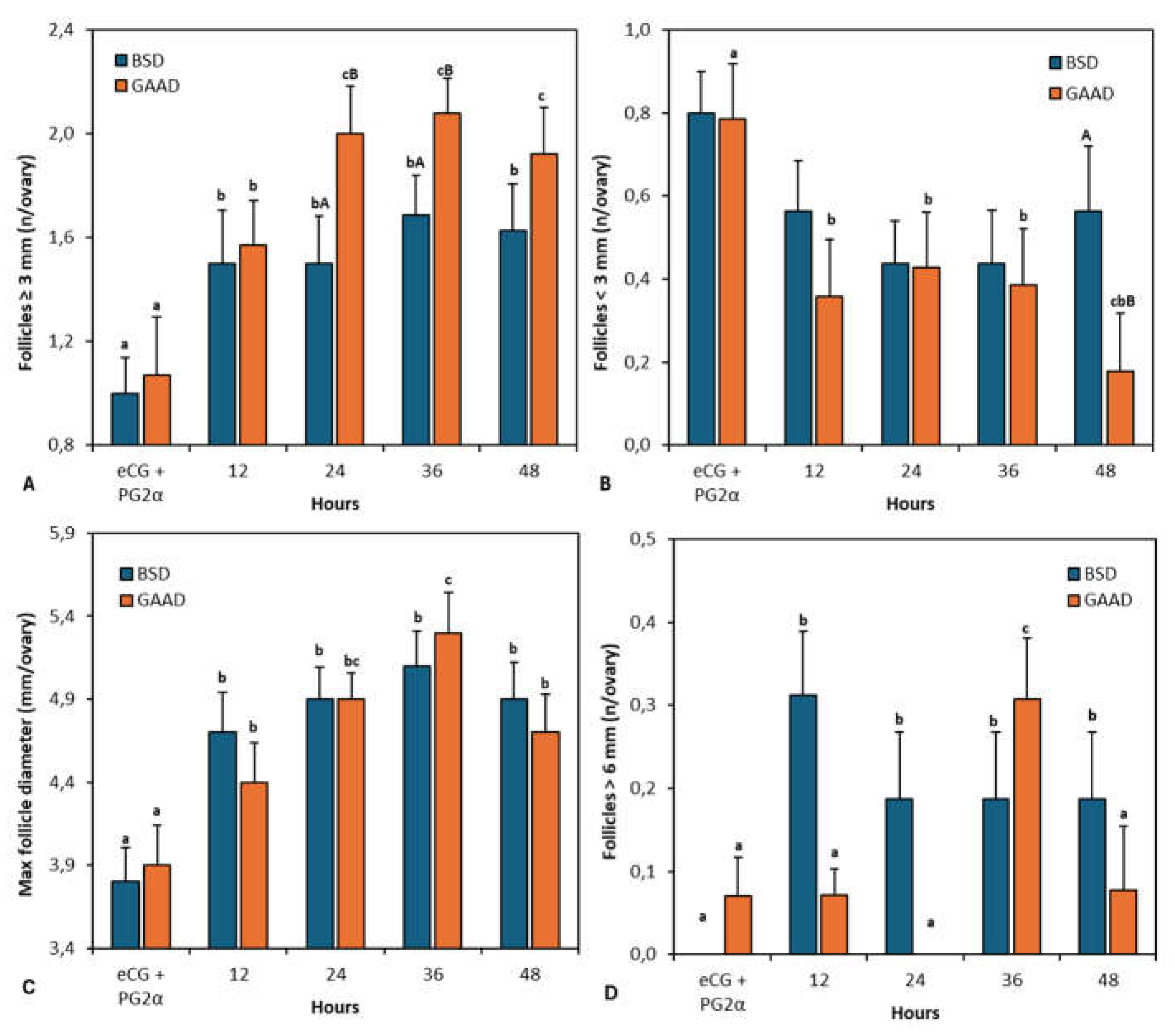

3.3. Follicle Turnover

3.4. Reproductive Outcome

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cao, Y.; Yao, J.; Sun, X.; Liu, S.; Martin, G.B. (2021). Amino acids in the nutrition and production of sheep and goats. Amino Acids in Nutrition and Health: Amino Acids in the Nutrition of Companion, Zoo and Farm Animals, 63-79.

- Wu, G.; Bazer, F.W.; Johnson, G.A.; Satterfield, M.C.; Washburn, S.E. Metabolism and Nutrition of L-Glutamate and L-Glutamine in Ruminants. Animals 2024, 14, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lass, G.; Li, X.F.; Voliotis, M.; Wall, E.; de Burgh, R.A.; Ivanova, D.; O’Byrne, K.T. GnRH pulse generator frequency is modulated by kisspeptin and GABA-glutamate interactions in the posterodorsal medial amygdala in female mice. Journal of Neuroendocrinology 2022, 34, e13207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conde, A.J.H.; Alves, J.P.M.; Fernandes, C.C.L.; Silva, M.R.L.; Cavalcanti, C.M.; Bezerra, A.F.; Rondina, D. Effect of one or two fixed glutamate doses on follicular development, ovarian-intraovarian blood flow, ovulatory rate, and corpus luteum quality in goats with a low body condition score. Animal Reproduction 2023, 20, e20220117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, A.C.S.; Alves, J.P.M.; Fernandes, C.C.L.; Silva, M.R.L.; Conde, A.J.H.; Teixeira, D.Í. A.; Rondina, D. Use of monosodium-glutamate as a novel dietary supplement strategy for ovarian stimulation in goats. Animal Reproduction 2023, 20, e20230094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luna-García LA, Meza-Herrera CA, Pérez-Marín CC, Corona R, Luna-Orozco JR, Véliz-Deras FG, DelgadoGonzalez R, Rodriguez-Venegas R, Rosales-Nieto CA, Bustamante-Andrade JA, Gutierrez-Guzman UN. Goats as valuable animal model to test the targeted glutamate supplementation upon antral follicle number, ovulation rate, and LH-Pulsatility. Biology 2022, 11, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, D.T.; Goodman, R.L.; Hileman, S.M.; Lehman, M.N. Evidence that synaptic plasticity of glutamatergic inputs onto KNDy neurones during the ovine follicular phase is dependent on increasing levels of oestradiol. Journal of neuroendocrinology 2021, 33, e12945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alborzi, P.; Atrabi, M.J.; Akbarinejad, V.; Khanbabaei, R.; Fathi, R. Incorporation of arginine, glutamine or leucine in culture medium accelerates in vitro activation of primordial follicles in 1-day-old mouse ovary. Zygote 2020, 28, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monte, A.P.O.; Barros, V.R.P.; Santos, J.M.; Menezes, V.G.; Cavalcante, A.Y.P.; Gouveia, B.B.; Matos, M.H.T. Immunohistochemical localization of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) in the sheep ovary and the synergistic effect of IGF-1 and FSH on follicular development in vitro and LH receptor immunostaining. Theriogenology 2019, 129, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdenis van Berlekom, A.; Kübler, R.; Hoogeboom, J.W.; Vonk, D.; Sluijs, J.A.; Pasterkamp, R.J.; Boks, M.P. Exposure to the amino acids histidine, lysine, and threonine reduces mTOR activity and affects neurodevelopment in a human cerebral organoid model. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, L.; Qi, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Li, J. BCAA insufficiency leads to premature ovarian insufficiency via ceramide-induced elevation of ROS. EMBO molecular medicine 2023, 15, e17450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simcox, J.; Lamming, D.W. The central moTOR of metabolism. Developmental cell 2022, 57, 691–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.S.; Micevych, P.E.; Mermelstein, P.G. Membrane estrogen signaling in female reproduction and motivation. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2022, 13, 1009379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Torre, S.; Rando, G.; Meda, C.; Stell, A.; Chambon, P.; Krust, A.; Maggi, A. Amino acid-dependent activation of liver estrogen receptor alpha integrates metabolic and reproductive functions via IGF-1. Cell metabolism 2011, 13, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lu, C.; Zhang, D.; Liu, H.; Cui, S. Taurine promotes estrogen synthesis by regulating microRNA-7a2 in mice ovarian granulosa cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2022, 626, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Li, S.; Cai, S.; Zhou, J.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, S.; Zeng, X. Dietary methionine supplementation during the estrous cycle improves follicular development and estrogen synthesis in rats. Food & Function 2024, 15, 704–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosnan, J.T.; Brosnan, M.E. Creatine: endogenous metabolite, dietary, and therapeutic supplement. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2007, 27, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muccini, A.M.; Tran, N.T.; de Guingand, D.L.; Philip, M.; Della Gatta, P.A.; Galinsky, R.; Ellery, S.J. Creatine metabolism in female reproduction, pregnancy and newborn health. Nutrients 2021, 13, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlattner, U.; Klaus, A.; Ramirez Rios, S.; Guzun, R.; Kay, L.; Tokarska-Schlattner, M. Cellular compartmentation of energy metabolism: creatine kinase microcompartments and recruitment of B-type creatine kinase to specific subcellular sites. Amino Acids 2016, 48, 1751–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiriwardhana, M.; Bertolo, R.F. Guanidinoacetic acid supplementation: a narrative review of its metabolism and effects in swine and poultry. Frontiers in Animal Science 2022, 3, 972868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scantland, S.; Tessaro, I.; Macabelli, C.H.; Macaulay, A.D.; Cagnone, G.; Fournier, É.; Robert, C. The adenosine salvage pathway as an alternative to mitochondrial production of ATP in maturing mammalian oocytes. Biology of reproduction 2014, 91, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamanho do mercado de ácido guanidinoacético – Relatório 2024 a 2032. Disponível em: <https://www.businessresearchinsights.com/pt/market-reports/guanidinoacetic-acid-market-100386>. Acesso em: 3 out. 2024.

- Speer, H.F. (2019). Efficacy of guanidinoacetic acid supplementation to growing cattle and relative bioavailability of guanidinoacetic acid delivered ruminally or abomasally (Doctoral dissertation, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KU, USA).

- Li, S.Y.; Wang, C.; Wu, Z.Z.; Liu, Q.; Guo, G.; Huo, W.J.; Zhang, S.L. Effects of guanidinoacetic acid supplementation on growth performance, nutrient digestion, rumen fermentation and blood metabolites in Angus bulls. Animal 2020, 14, 2535–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zang, C.; Pan, J.; Ma, C.; Wang, C.; Li, X.; Yang, K. Effects of dietary guanidinoacetic acid on growth performance, guanidinoacetic acid absorption and creatine metabolism of lambs. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L.C.O.; et al. Dietary guanidinoacetic acid as arginine spare molecule for beef cows at late gestation: Effects on cow’s performance and metabolism, and offspring growth and development. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2024, 315, 116047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA FEEDAP Panel (EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed), Bampidis V, Azimonti G, Bastos ML, Christensen H, Dusemund B, Fasmon Durjava M, Kouba M, Lopez-Alonso M, Lopez Puente S, Marcon F, Mayo B, Pechova A, Petkova M, Ramos F, Sanz Y, Villa RE, Woutersen R, Gropp J, Anguita M, Galobart J, Ortu~ no Casanova J, Pizzo F and Tarres-Call J, 2022. Scientific Opinion on the safety and efficacy of a feed additive consisting of guanidinoacetic acid for all animal species (Alzchem Trostberg GmbH). EFSA Journal 2022;20:7269, 17pp. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.C.L.; Aguiar, L.H.; Calder’on, C.E.M.; Silva, A.M.; Alves, J.P.M.; Rossetto, R.; Bertolini, L.R.; Bertolini, M.; Rondina, D. Nutritional impact on gene expression and competence of oocytes used to support embryo development and livebirth by cloning procedures in goats. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2018, 188, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Research Council. (2007). Nutrient requirements of small ruminants: Sheep, goats, cervids, and new world camelids.

- Morales-Martinez, M.A.; et al. Developing equations for predicting internal body fat in Pelibuey sheep using ultrasound measurements. Small Ruminant Research 2020, 183, 106031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza S.S, Alves B.G, Alves K.A, Santos J.D.R, Diogenes Y.P, Bhat M.H, Melo L.M, Freitas V.J.F, Teixeira D. I.A. Relationship of Doppler velocimetry parameters with antral follicular population and oocyte quality in Canindé goats. Small Rumin Res. 2016;141:39-44. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.E.; Feliciano, M.A.; D’Amato, C.C.; Oliveira, L.G.; Bicudo, S.D.; Fonseca, J.F.; Bartlewski, P.M. Correlations between ovarian follicular blood flow and superovulatory responses in ewes. Animal Reproduction Science 2014, 144, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaro, M.F.A.; Santos, A.S.; Moura, L.F.G.; Fonseca, J.F.; Brandão, F.Z. Luteal dynamic and functionality assessment in dairy goats by luteal blood flow, luteal biometry, and hormonal assay. Theriogenology 2017, 95, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G. Important roles of dietary taurine, creatine, carnosine, anserine and 4-hydroxyproline in human nutrition and health. Amino Acids 2020, 52, 329–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, E.; Chan, S.; Monfared, M.; Wallimann, T.; Clarke, K.; Neubauer, S. Creatine transporter activity and content in the rat heart supplemented by and depleted of creatine. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 2003, 284, E399–E406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, R.J.; Murphy, R.M. Creatine and the creatine transporter: a review. Molecular and cellular biochemistry 2001, 224, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlattner, U.; Tokarska-Schlattner, M.; Wallimann, T. Mitochondrial creatine kinase in human health and disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease 2006, 1762, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derave, W.; Marescau, B.; Eede, E.V.; Eijnde, B.O.; De Deyn, P.P.; Hespel, P. Plasma guanidino compounds are altered by oral creatine supplementation in healthy humans. Journal of Applied Physiology 2004, 97, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, M.; Kaddurah-Daouk, R. Creatine and creatinine metabolism. Physiological reviews 2000, 80, 1107–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G. (2021). Amino Acids: Biochemistry and Nutrition (2nd ed.). CRC Press. [CrossRef]

- Acosta, T.J.; Hayashi, K.G.; Ohtani, M.; Miyamoto, A. Local changes in blood flow within the preovulatory follicle wall and early corpus luteum in cows. Reproduction 2003, 125, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelnaby, E.A.; Alhaider, A.K.; El-Maaty, A.M.A.; Ragab, R.S.; Seida, A.A.; El-Badry, D.A. Ovarian and uterine arteries blood flow velocities waveform, hormones and nitric oxide in relation to ovulation in cows superstimulated with equine chorionic gonadotropin and luteolysis induction 10 and 17 days after ovulation. BMC Veterinary Research 2023, 19, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambliss, K.L.; Shaul, P.W. Estrogen modulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Endocrine Reviews 2002, 23, 665–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, E.; Anter, E.; Zou, M.H.; Keaney Jr, J.F. Estradiol-mediated endothelial nitric oxide synthase association with heat shock protein 90 requires adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Circulation 2005, 111, 3473–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, A.J.; Reyes, R.; Kang, L.S.; Dailey, R.A.; Stallone, J.N.; Moningka, N.C.; Muller-Delp, J.M. Estrogen replacement restores flow-induced vasodilation in coronary arterioles of aged and ovariectomized rats. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2009, 297, R1713–R1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oess, S.; et al. Subcellular targeting and trafficking of nitric oxide synthases. Biochemical Journal 2006, 396, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsey, K.E.; Ellis, P.J.; Sargent, C.A.; Sturmey, R.G.; Leese, H.J. Expression and localization of creatine kinase in the preimplantation embryo. Molecular reproduction and development 2013, 80, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlén, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Pontén, F. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015, 347, 1260419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelli, M.A.; Iuliano, A.; Schettini, S.C.A.; Petruzzi, D.; Ferri, A.; Colucci, P.; Ostuni, A. Metabolic changes in follicular fluids of patients treated with recombinant versus urinary human chorionic gonadotropin for triggering ovulation in assisted reproductive technologies: A metabolomics pilot study. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2020, 302, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umehara, T.; Kawai, T.; Goto, M.; Richards, J.S.; Shimada, M. Creatine enhances the duration of sperm capacitation: a novel factor for improving in vitro fertilization with small numbers of sperm. Human Reproduction 2018, 33, 1117–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Gorman, A.; Wallace, M.; Cottell, E.; Gibney, M.J.; McAuliffe, F.M.; Wingfield, M.; Brennan, L. Metabolic profiling of human follicular fluid identifies potential biomarkers of oocyte developmental competence. Reproduction 2013, 146, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.S.; Liu, C.H.; Lee, T.H.; Wu, H.M.; Huang, C.C.; Huang, L.S.; Cheng, E.H. Association of creatin kinase B and peroxiredoxin 2 expression with age and embryo quality in cumulus cells. Journal of assisted reproduction and genetics 2010, 27, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhde, K.; van Tol, H.T.; Stout, T.A.; Roelen, B.A. Metabolomic profiles of bovine cumulus cells and cumulus-oocyte-complex-conditioned medium during maturation in vitro. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 9477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, C.; Neto, A.C.; Matos, L.; Silva, E.; Ribeiro, Â.; Silva-Carvalho, J.L.; Almeida, H. Follicular Fluid redox involvement for ovarian follicle growth. Journal of Ovarian Research 2017, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA FEEDAP Panel (EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed), 2016. Scientific opinion on the safety and efficacy of guanidinoacetic acid for chickens for fattening, breeder hens and roosters, and pigs. EFSA Journal 2016;14:4394, 39pp. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Villasana, J.; López-Aguirre, D.; Peña-Avelino, L.Y.; Zapata-Campos, C.C.; Alvarado-Ramírez, E.R.; González, D.N.T.; Salem, A.Z.M. Influence of dietary supplementation of guanidinoacetic acid on growth performance and blood chemistry profile of growing steers. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2024, 18, 101327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Wei, M.; Ju, J.; Du, L.; Zhang, R.; Xiao, M.; Bao, M. Effects of guanidinoacetic acid on in vitro rumen fermentation and microflora structure and predicted gene function. Frontiers in Microbiology 2024, 14, 1285466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leese, H.J.; McKeegan, P.J.; Sturmey, R.G. Amino acids and the early mammalian embryo: Origin, fate, function and life-long legacy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 9874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Cano, A.M.; Calzada-Mendoza, C.C.; Estrada-Gutierrez, G.; Mendoza-Ortega, J.A.; Perichart-Perera, O. Nutrients, mitochondrial function, and perinatal health. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabozzi, G.; Iussig, B.; Cimadomo, D.; Vaiarelli, A.; Maggiulli, R.; Ubaldi, N.; Ubaldi, F.M.; Rienzi, L. The impact of unbalanced maternal nutritional intakes on oocyte mitochondrial activity: implications for reproductive function. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krisher, R.L. Oocyte and embryo metabolomics. Biosci. Proc. 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Sturmey, R.; Zhang, J. Dynamic metabolism during early mammalian embryogenesis. Development 2023, 150, dev202148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placidi, M.; Di Emidio, G.; Virmani, A.; D’Alfonso, A.; Artini, P.G.; D’Alessandro, A.M.; Tatone, C. Carnitines as mitochondrial modulators of oocyte and embryo bioenergetics. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, L.; Monti, M.; Sebastiano, V.; Merico, V.; Nicolai, R.; Calvani, M. Single-cell quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Cpt1b and Cpt2 gene expression in mouse antral oocytes and in preimplantation embryos. Cytogenetic and genome research 2004, 105, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Diet | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSD | GAAD | SEM | Diet | Time | D x T | |

| Body and carcass marker* | ||||||

| BMI | 10.5 | 9.1 | 0.486 | 0.142 | - | - |

| SLFT, mm | 3.2 | 2.9 | 0.106 | 0.310 | - | - |

| KFT, mm | 1.3 | 1.4 | 0.025 | 0.130 | - | - |

| LD, mm | 23.5 | 22.9 | 0.593 | 0.619 | - | - |

| Feed intake | ||||||

| DMI, kg/ewe | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.012 | 0.567 | 0.800 | 0.965 |

| DMI, % BW | 2.4 | 2.3 | 0.028 | 0.569 | 0.782 | 0.984 |

| Peripheral metabolic marker | ||||||

| Glucose, mg/dL | 60.0 | 58.4 | 0.554 | 0.146 | 0.224 | 0.562 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL | 55.2 | 53.1 | 0.909 | 0.321 | 0.904 | 0.312 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 25.5 | 24.0 | 0.823 | 0.132 | 0.128 | 0.336 |

| *Performed at the beginning of the experiment; BW, body weight; BMI, body mass index, SLFT, subcutaneous loin fat thickness; KFT, kidney fat thickness; LD, loin depth; DMI, dry matter intake. Time: ANOVA effect for the assessment interval adopted. | ||||||

| Parameter | Diet | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSD | GAAD | SEM | Diet | Time | D x T | |

| N of ewes in estrus, % (n\n) | 100.0 (10/10) | 100.0 (10/10) | - | - | ||

| Estrus onset *, h | 33.6 | 31.4 | 2.465 | 0.646 | - | - |

| Estrus length, h | 46.4 | 38.5 | 2.893 | 0.180 | - | - |

| CL, n\goat | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.163 | 0.876 | - | - |

| CL area, mm2 | 8.1 | 7.3 | 0.339 | 0.079 | < 0.001 | 0.546 |

| CL doppler area, mm2/ovary | 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.076 | 0.095 | < 0.001 | 0.905 |

| Pregnancy rate, % (n/n) | 80.0 (8/10) | 70.0 (7/10) | - | 0.879 | - | - |

| Twinning rate, % (n/n) | 25.0 (2/8) | 28.5 (2/7) | - | 0.784 | - | - |

| Litter size, n (n/n) | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.118 | 0.886 | - | - |

| Pregnancy failure**, % (n/n) | 20.0 (2/10) | 30.0 (3/10) | - | 0.823 | - | - |

| *Interval between progesterone sponge removal and estrus onset; **Gestation failures occurred from mating to pregnancy diagnosis; CL, corpus luteum; Time: ANOVA effect for the assessment interval adopted. | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).