1. Introduction

The “algarrobo”,

Neltuma pallida (Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd.) C.E. Hughes & G.P. Lewis is a tree species within the genus

Neltuma, which is distributed across the arid and seasonally dry tropical region of South America [

1].

N. pallida occurs naturally in the arid lowlands along the Pacific coast of Peru, Colombia, and Ecuador, and has been introduced into other regions of the Americas and Asia [

2]. It is a keystone species, highly adapted to the variable dry and wet conditions of northern coastal Peru [

3] and plays a vital role in sustaining rural livelihoods by providing firewood, charcoal, and forage for livestock [

4]. Currently,

N. pallida population is undergoing a decline due to illegal logging, pest outbreaks, and land-use change [

5,

6,

7]. It is considered a high-risk genetic resource in South America [

8].

Natural forest regeneration depends on seed dispersal, a critical ecological process for habitat colonization and landscape connectivity [

9,

10,

11].

N. pallida, like other species within the genus

Neltuma (formerly Prosopis), is primarily dispersed through endozoochoric [

12,

13], a form of seed dispersal mediated by animals that involves seed release, scarification, and transportation. The species produces indehiscent legumes with thick seed coats that protect the seeds [

14]. Seed release is essential, as seeds contained in intact pods and deposited on the ground typically fail to germinate [

15]. Moreover,

Neltuma seeds exhibit physical dormancy due to a water-impermeable seed coat [

16]; without scarification, germination rates can be lower than 7% for several

Neltuma species [

17].

Among the most important endozoochorous dispersers of

Neltuma species are wild and domestic herbivorous mammals, which are capable of transporting seeds over long distances [

15,

18,

19,

20]. In the case of N. pallida in dry forest ecosystems, this role would historically have been fulfilled by the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), a remnant of the Neotropical megafauna [

21]. However, this species is now highly scarce, mainly due to poaching. Conversely, since the expansion of goat (

Capra hircus) husbandry in the 18th century [

22], goat rearing has become widespread throughout these forests. Currently, in Peru alone, approximately 500,000 goats are raised in these ecosystems.

This shift in ruminant populations may influence the efficiency of

N. pallida endozoochory. Exotic dispersers can have negative effects on the germination of seeds from native species [

23]; even though both species are ruminants, they differ functionally in their feeding strategies. While the white-tailed deer is a concentrate se-lector (CS), the goat is classified as an intermediate feeder [

24]. These feeding types are associated with distinct morphophysiological traits that may influence seed recovery and scarification, potentially altering the natural regeneration dynamics of

N. pallida.

To date, no studies have evaluated the seed scarification efficiency of N. pallida by goats and white-tailed deer. We hypothesize that seed passage through the gastrointestinal tract enhances both the germination rate and percentage of N. pallida seeds, and that this effect may be greater when mediated by white-tailed deer. To assess endozoochorous efficiency in goats and deer, we evaluated seed recovery and germination of N. pallida through both controlled experiments and grazing trials in dry forest ecosystems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location

Two feeding trials for seed scarification were conducted: one under field conditions with grazing goats, and another under controlled feeding conditions with both goats and white-tailed deer. For the grazing trial, a goat herd was selected in the locality of Belén (5° 01′42.9″ S, 80° 09′31.41″ W; 104 m.a.s.l.), located within the dry forests of Chulucanas, Piura region. The controlled feeding experiments were conducted using enclosures at the Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina (UNALM) and a fenced area at the “White-tailed Deer” breeding center of the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú (PUCP) from May to September 2018.

2.2. Fruit Collection and Characteristics

Fruits of

N. pallida were randomly collected from 40 trees within a 12-hectare relict dry forest in Chulucanas, Piura region, Peru (5° 01′ S, 80°09′ W; 102 m.a.s.l.) during April 2018. The fruits were stored in a dry environment until the start of the feeding trials, two weeks later. Fruits were characterized by the number of viable seeds per kilogram, as N. pallida seeds are rapidly parasitized by bruchid beetles over successive generations [

25]. At the time of the experimental feeding, the average weight of a healthy seed was 38 ± 6 mg (n = 249), corresponding to an estimated 2,140 viable seeds per kilogram of fruit at the onset of the feeding experiment.

2.3. Feeding Trials

Feeding trials with N. pallida fruits were conducted using goats and while-tailed deer under confinement conditions in Lima, and with goats under grazing conditions in dry forest areas of Chulucanas, Piura. In the dry forest environment, only goats were used, as the extremely low density of while-tailed deer made it unfeasible to recover a sufficient quantity of seed-containing dung.

Five goats were housed in a shared 40 m² pen equipped with a large feeder, ad libitum forage, and water. The three deer were kept within a 150 m² fenced enclosure inside the breeding center. The base diet consisted of maize (Zea mays) and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) forage for the goat, and alfalfa (Medicago sativa) and broad bean pods (Vicia faba) for the deer. It was not possible to use the same forage source for both species, as the deer consistently rejected grasses. Both goats and deer underwent a 14-day adaptation period during which they were gradually offered N. pallida, increasing from 300 to 700 g/animal. After this period, the pods were removed from the diet, and animals were monitored for an additional 14 days to allow for complete defecation of any ingested seeds.

Finally, animals were fed a single dose of N. pallida pods: 940 g for deer (equivalent to 1,900 seeds). Dung were collected at 12-hour intervals over 7 days. To prevent premature seed germination, samples were immediately oven-dried at 48ºC (maintaining approximately 40ºC at the fecal surface) for 3 hours. The presence of seed in goat and deer dung was recorded daily to estimate the temporal pattern and percentage of seed recovery

2.4. Scarification Treatment

Seeds were recovered from the dung of goat and white-tailed deer (WTD) to evaluate germination performance, in comparison with manually extracted seeds and seeds subjected to physical scarification. The treatments are detailed in

Table 1. During seed recovery, two categories of seeds were observed: (1) normal seeds with an appearance identical to the ingested ones, and (2) germinating or degraded seeds, typically black in color and ranging from smooth to wrinkled. For germination trials, only seeds with normal appearance were counted and used (

Figure 2).

2.5. Germination Experiment

Germination experiment was conducted between June and July 2018 at the Laboratorio de Ecología y Utilización de Pastizales (LEUP) of the Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina, Peru. All seeds were disinfected by immersion in a 1% sodium hypochlorite solution for 2 minutes, followed by rinsing with distilled water. For each treatment, six 9 cm Petri dishes (replicates) were prepared, each containing 50 seeds. Seeds were placed on layers of filter paper, and moisture was maintained daily using distilled water. Petri dishes were placed in controlled environment germination chambers, set to a photoperiod of 12 h light at 30°C and 12 h dark at 15°C, with constant relative humidity at 70%. A gradual temperature transition between the light and dark periods was programmed to simulate natural dry forest conditions. Germination was monitored daily over 35 days. A seed was considered germinated when the radicle reached a length of 2 mm.

Figure 1.

(a) Fragments and seeds recovered from WTD dung, (b) Appearance of seeds considered for the germination experiment. (c) Seeds in the process of germination, with signs of inhibition and darkening.

Figure 1.

(a) Fragments and seeds recovered from WTD dung, (b) Appearance of seeds considered for the germination experiment. (c) Seeds in the process of germination, with signs of inhibition and darkening.

2.6. Data Analysis

Seed recovery and germination data were treated as proportions. The temporal dynamics of seed recovery and germination were described using the Morgan-Mercer-Flodin [

26], a commonly employed to method for modeling cumulative seed recovery and germination curves [

15]. This function models sigmoidal cumulative curves (assuming recovery and germination equal to zero at time zero). The model includes three parameters: alpha, gamma, and m. Parameters were estimated using nonlinear least squares.

In the model, g represents cumulative germination, t is time in days, alpha is the asymptote or maximum germination, m is the growth rate, and gamma is a parameter controlling the inflection point. These parameters were estimated using nonlinear least squares regression.

For germination analysis, final germination percentage at 35 days was calculated, along with two germination speed indices: time to reach 25% germination (T25) and mean germination time (MGT) [

27]. T25 was used instead of T50, as most treatments did not reach 50% cumulative germination within the 35-day evaluation. Final germination percentage and MGT were compared using one-way ANOVA, after verifying assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity. Pairwise comparisons among treatments were conducted using Tukey’s test.

All analyses were performed using R software version 4.4.1 [

28], with the packages “growthmodels” (for nonlinear regression), “binom” (for binomial confidence intervals), and “multcompView” (for mean comparison visualizations).

3. Results

3.1. Seed Recovery

The estimated number of seeds consumed was 2,214 for goats and 1,914 for white-tailed deer (WTD), derived from the quantity of fruits ingested by the animals during the experimental trials. The recovery of N. pallida seeds from dung was 68 seeds (3.09%) for goats and 178 seeds (9.36%) for deer.

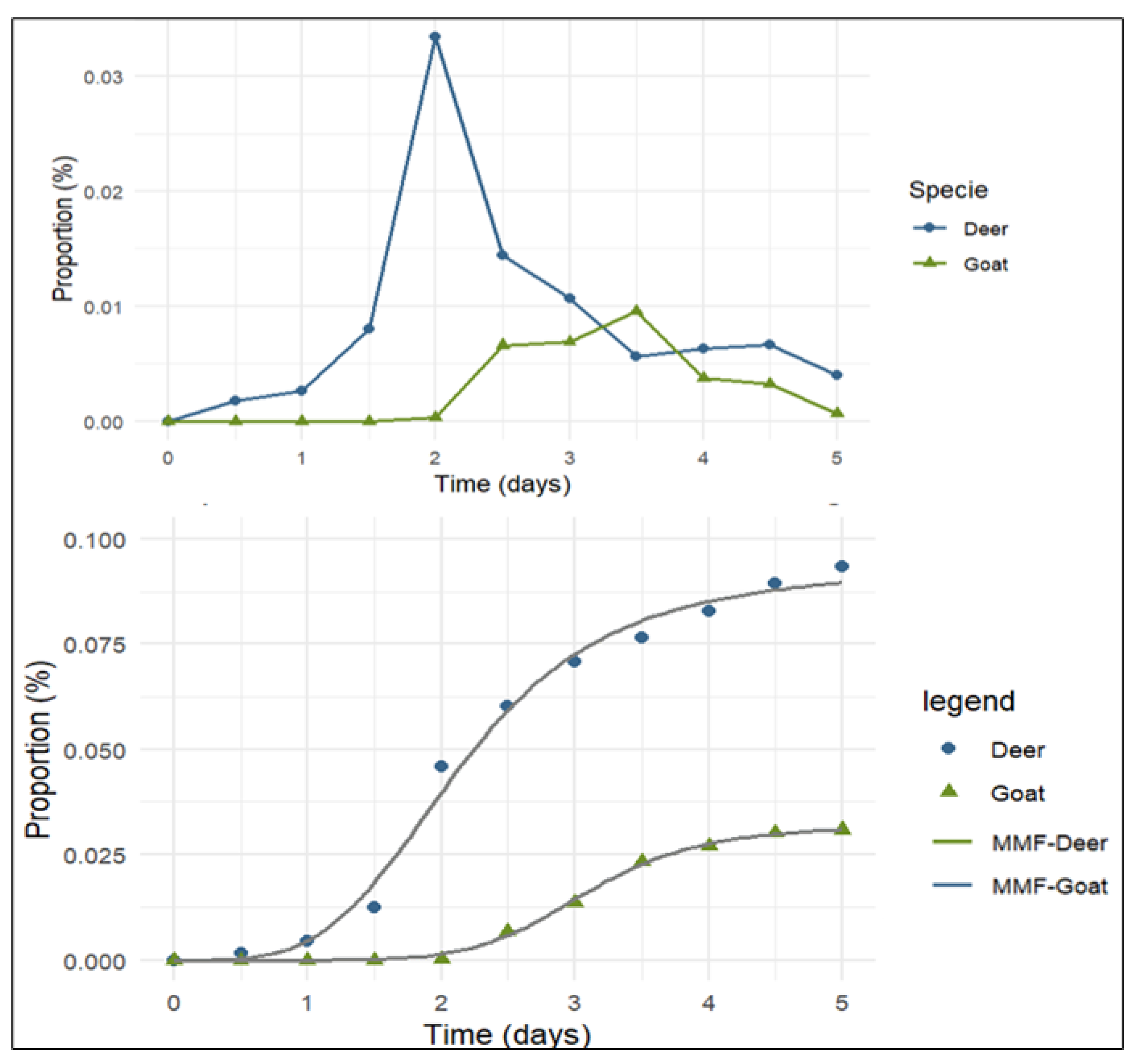

Table 2 presents the estimated parameters of the Morgan-Mercer-Flodin model for seed recovery; the asymptotes correspond to the final percentages of recovered seeds. Maximum seed recovery in WTD occurred at 48 hours (2 days), with 35.7% of total recovered seeds being defecated by that time. In goats, the peak recovery occurred at 84 hours (3.5 days), with 31% of seeds recovered (

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proportion of N. pallida seeds recovered from white-tailed deer (WTD) and goat feces. The curves show the predictions of the Morgan-Mercer-Flodin (MMF) model.

Figure 2.

Proportion of N. pallida seeds recovered from white-tailed deer (WTD) and goat feces. The curves show the predictions of the Morgan-Mercer-Flodin (MMF) model.

3.2. Germination Dynamics

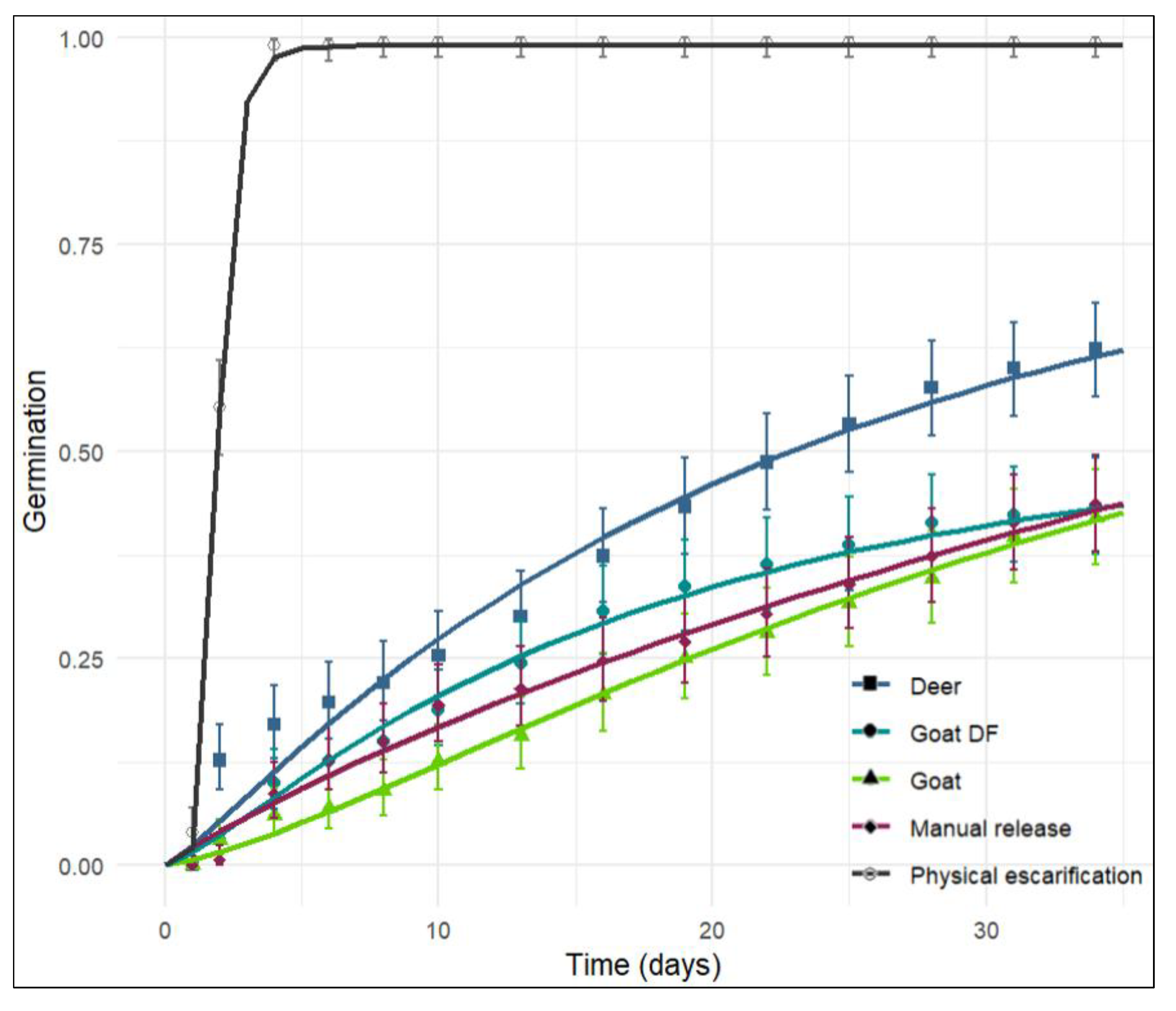

The modeled curves revealed substantial differences in the cumulative germination dynamics among treatments (

Figure 3). The highest asymptotic values (alpha) were observed for the manual extraction treatment (171%), followed by deer (101%), physical scarification (99%), confined goats (96%), and goats under dry forest grazing conditions (63%).

Table 3.

Model parameters for predicting the proportion of germinated seeds of N. pallida according to the Morgan-Mercer-Flodin.

Table 3.

Model parameters for predicting the proportion of germinated seeds of N. pallida according to the Morgan-Mercer-Flodin.

| Treament |

alpha |

gamma |

m |

R2 |

Final germination (35 days) |

Final germination (90 days) |

|

| Manual release |

1.71 |

76.66 |

0.92 |

0.87 |

0.46 |

0.76 |

|

| Physical scarification |

0.99 |

0.45 |

0.59 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

0.99 |

|

| Goat |

0.96 |

157.26 |

1.36 |

0.90 |

0.44 |

0.71 |

|

| Deer (WDT) |

1.01 |

39.76 |

1.17 |

0.91 |

0.63 |

0.82 |

|

| Goat in dry forest |

0.61 |

37.72 |

1.28 |

0.87 |

0.44 |

0.56 |

|

Final germination was significantly higher in seeds subjected to physical scarification and in seeds recovered from white-tailed deer dung (F = 40.99, Tukey test, p < 0.001). In contrast, seed passage through the gastrointestinal tract of goats, both under confined conditions and in dry forest grazing, had no significant effect compared to manually extracted seeds. Except for the physical scarification treatment, all treatments exhibited mean germination time (MGT) values similar to the untreated control (manual extraction). However, significant differences were detected between the confined goat and grazing goat treatments (F = 40.96, Tukey test, p < 0.001). The time to reach 25% germination (T25) was lowest in physically scarified seeds (1.59 days), followed by seeds recovered from deer dung (8.98 days). Grazing goats reduced T25 to 12.81 days, whereas confined goats increased it to 19.25 days (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

4.1. Seed Recovery

Overall, seed recovery from goat and white-tailed deer (WTD) dung was low (9.4 % and 3.09 % respectively), consistent with previous studies. Recovery rates below 11% have been reported for Fabaceae species ingested by goat in dry forests of Brazil [

29]. In Mediterranean shrublands, seed recovery from goat dung ranges from 1% to 31% [

30,

31]. These values also fall within the range reported for other

Neltuma species. For

N. juliflora, recovery rates of 7% in goat and 15% in cattle have been reported [

15]; for

N. glandulosa, 9.2% and 11.3% for goats and sheep, respectively [

32]; and for

N. pallida, 2.1% in camels [

18]. These results confirm that a large proportion of seeds are lost during mastication and rumination processes. Regarding seed retention time, it was shorter in WTD (peak at 48 hours) than in goats (peak at 84 hours), which aligns with previous reports for medium-sized seeds, typically retained between 72 and 96 hours [

29]. For shrub species, the majority of seeds consumed by goats are excreted between 24 and 48 hours [

31]. The shorter retention time of

N. pallida seeds in WTD can be explained by a relatively smaller stomach size, fewer subdivisions, and larger openings that facilitate the passage of ingested material [

24]. "Similarly, a shorter seed recovery time in goats compared to cows has been reported for

N. juliflora [

15] and

N. flexuosa [

33]. This variation in seed retention is attributed to the presence of structures and mechanisms that delay the passage of ingested material in different types of ruminants: WTD (concentrate selector) exhibit shorter retention than goats (intermediate feeders), which in turn have shorter retention than cows (grazers) described by [

24].

4.2. Seed Germination Dynamics

Species of the genus

Neltuma, like many members of the Fabaceae family, exhibit physical dormancy. The seed coat contains a water-impermeable layer that prevents imbibition and germination [

16]. This impermeability is due to a palisade layer of tightly packed cells impregnated with water-repellent substances [

16,

34]. This type of dormancy can be broken through mechanical or acid scarification [

35]. The 99% germination observed in the physical scarification (sandpaper) treatment, compared to the much lower germination in manually extracted seeds, confirms the presence of physical dormancy in

N. pallida.

Similar results have been reported for

N. juliflora using chemical scarification (Alvarez et al., 2017). Among the biological scarification treatments, only white-tailed deer (WTD) significantly increased the final germination of

N. pallida seeds. These findings are consistent with prior evidence indicating that physical dormancy is not always broken through endozoochory [

36]. The differences observed between WTD and goats under experimental feeding conditions may be explained by variation in hydrochloric acid (HCL) concentration in the abomasum. WTD have a greater proportion of HCl-producing tissues in the abomasum compared to goats, an adaptation related to their distinct evolutionary feeding strategies [

24]. However, the duration of seed exposure to acidic conditions is also important, as it can influence the extent of scarification by HCL [

35].

In terms of germination speed (T25), seeds recovered from goat dung (both experimental feeding and dry forest grazing) showed variable responses compared to untreated seeds (manual extraction). T25 was reduced in seed from goats under experimental feeding conditions. These differences may be linked to the frequency of seed consumption. In the experimental setup, goats ingested seed only once, while in the forest, goats consumed

Neltuma fruits daily. Previous studies have shown that variable exposure time of physically dormant seeds to HCL can influence germination timing, particularly T50 [

35]. Therefore, seeds recovered from grazing goat may have originated from fruits ingested at different times and retained for variable durations. Daily ingestion could also alter the overall passage time of seeds through the gastrointestinal tract. In similar studies with shrub species in Spain, seed germination following goat digestion showed inconsistent effects, with longer retention times not always improving germination outcomes [

30,

37].

5. Conclusions

Our study found clear differences in the recovery and germination of

N. pallida seeds ingested by goats. These results align with known morphophysiological differences among ruminant feeding types (Hofmann, 1989). Biological scarification by white-tailed deer was more effective than that by goats in enhancing seed germination. Additionally, the frequency of fruit ingestion by goats may either increase or reduce the germination speed of

N. pallida seeds recovered from dung. Although both species contribute to seed dispersal, the current low population density of white-tailed deer means that goats are now the primary seed dispersers in these dry forests. While goat digestion does not significantly enhance final germination rates, it does play a key role in seed release and dispersal. Moreover, ingestion and subsequent encapsulation of seeds in dung can protect them from bruchid predation [

25]. Goat dung also provides a favorable microenvironment by offering nutrients and moisture that can support seedling establishment, as observed in

N. juliflora. [

13].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S-M and L.A. methodology: J. S-M; investigation, J.S-M and L.A..; supervision, L.A.; writing—original draft, J. S-M., and L.A.; writing—review and editing, L.A. and J.C. funding acquisition: J.S-M.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

"This research was funded by the Vice-Rectorate for Research of the National Agrarian University La Molina through a thesis grant competition, and the APC was funded by the Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria (INIA), through the research goat project (CUI Nº 2506684).

Acknowledgments

"We express our gratitude to the Programa de Animales Menores of the Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina for their support during the goat experiments; to the Zoocriadero ‘Venado Cola Blanca’ of the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú for authorizing the experiments with white-tailed deer; and to the residents of the annex of Belén, Chulucanas, Piura, for their valuable assistance in accessing the forest, visiting goat herds, and collecting seeds.".

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hughes, C.E.; Ringelberg, J.J.; Lewis, G.P.; Catalano, S.A. Disintegration of the Genus Prosopis L. (Leguminosae, Caesalpinioideae, Mimosoid Clade). PhytoKeys 2022, 205, 147–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkart, A. A Monograph of the Genus Prosopis (Leguminosae Subfam. Mimosoideae). Journal of the Arnold Arboretum 1976, 57, 450–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar Zarzosa, P.; Mendieta-Leiva, G.; Navarro-Cerrillo, R.M.; Cruz, G.; Grados, N.; Villar, R. An Ecological Overview of Prosopis Pallida, One of the Most Adapted Dryland Species to Extreme Climate Events. Journal of Arid Environments 2021, 193, 104576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depenthal, J.; Meitzner Yoder, L.S. Community Use and Knowledge of Algarrobo (Prosopis Pallida) and Implications for Peruvian Dry Forest Conservation. Rev. Ambientales. 2017, 52, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, E.; Salazar, W.; Gálvez-Paucar, D.; Valqui-Valqui, L.; Saravia, D.; Gonzales, J.; Aldana, W.; Vásquez, H.V.; Arbizu, C.I. Cover and Land Use Changes in the Dry Forest of Tumbes (Peru) Using Sentinel-2 and Google Earth Engine Data. Environmental Sciences Proceedings 2022, 22, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, E.; Cruz, C.; Barboza, E.; Salazar, W.; Canta, J.; Salazar, E.; Vásquez, H.V.; Arbizu, C.I. Change of Vegetation Cover and Land Use of the Pómac Forest Historical Sanctuary in Northern Peru. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 21, 8919–8930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorogastúa Cruz, P.; Quiroz Guerra, R.; Garatuza Payán, J. Evaluación de Cambios En La Cobertura y Uso de La Tierra Con Imágenes de Satélite En Piura - Perú. Ecología Aplicada 2011, 10, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zonneveld, M.; Thomas, E.; Castañeda-Álvarez, N.P.; Van Damme, V.; Alcazar, C.; Loo, J.; Scheldeman, X. Tree Genetic Resources at Risk in South America: A Spatial Threat Assessment to Prioritize Populations for Conservation. Diversity and Distributions 2018, 24, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schupp, E.W.; Jordano, P.; Gómez, J.M. Seed Dispersal Effectiveness Revisited: A Conceptual Review. New Phytologist 2010, 188, 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, M.L.; Milligan, B.G.; Strand, A.E. Long-Distance Seed Dispersal in Plant Populations. American Journal of Botany 2000, 87, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichberg, C.; Storm, C.; Schwabe, A. Endozoochorous Dispersal, Seedling Emergence and Fruiting Success in Disturbed and Undisturbed Successional Stages of Sheep-Grazed Inland Sand Ecosystems. Flora: Morphology, Distribution, Functional Ecology of Plants 2007, 202, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.M.; Ramos, L.; Manrique, N.; Cona, M.I.; Sartor, C.; De Los Ríos, C.; Cappa, F.M. Filling Gaps in the Seed Dispersal Effectiveness Model for Prosopis Flexuosa : Quality of Seed Treatment in the Digestive Tract of Native Animals. Seed Sci. Res. 2020, 30, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, C.E.D.S.; Da Silva, C.A.D.; Leal, I.R.; Tavares, W.D.S.; Serrão, J.E.; Zanuncio, J.C.; Tabarelli, M. Seed Germination and Early Seedling Survival of the Invasive Species Prosopis Juliflora (Fabaceae) Depend on Habitat and Seed Dispersal Mode in the Caatinga Dry Forest. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunn, C.R. Fruits and Seeds of G,Enerain the Subfamily Mimosoideae (Fabaceae); Agricultural Research Service, Ed.; 1986. 1986.

- Alvarez, M.; Leparmarai, P.; Heller, G.; Becker, M. Recovery and Germination of Prosopis Juliflora (Sw.) DC Seeds after Ingestion by Goats and Cattle. Arid Land Research and Management 2017, 31, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, J.M.; Baskin, C.C. A Classification System for Seed Dormancy. Seed Sci. Res. 2004, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aubeterre, R.; Principal, J.; García, J. Effect of Different Scarification Methods on the Germination of Three Species of the Prosopis Genera. Revista Científica 2002, 7, 575–577. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, A.M.; Mancilla-Leytón, J.M.; Castillo, J.M. Can Camels Disperse Seeds of the Invasive Tree Prosopis Juliflora ? Weed Research 2018, 58, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.M.; Campos, V.E.; Mongeaud, A.; Borghi, C.E.; De los Rios, C.; Giannoni, S.M. Relationships between Prosopis Flexuosa (Fabaceae) and Cattle in the Monte Desert: Seeds, Seedlings and Saplings on Cattle-Use Site Classes. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 2011, 84, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.M.; Velez, S. Opportunistic scatter hoarders and frugivores: the role of mammals in dispersing Prosopis flexuosa in the Monte desert, Argentina. ECOS 2015, 24, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara-Guerrero, A.; Escribano-Avila, G.; Espinosa, C.I.; De La Cruz, M.; Méndez, M. White-tailed Deer as the Last Megafauna Dispersing Seeds in Neotropical Dry Forests: The Role of Fruit and Seed Traits. Biotropica 2018, 50, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivasplata Varillas, E.P. Cambio de paisajes de la costa norte peruana desde una perspectiva histórica y geográfica. Historia 2.0: Conocimiento Histórico en Clave Digital 2014, 47–73.

- Torres, D.A.; Castaño, J.H.; Carranza-Quiceno, J.A. Global Patterns in Seed Germination after Ingestion by Mammals. Mammal Review 2020, 50, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, R.R. Evolutionary Steps of Ecophysiological Adaptation and Diversification of Ruminants: A Comparative View of Their Digestive System. Oecologia 1989, 78, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattar, V.T.; Hollmann, A.; Rodriguez, S.A. Insecticidal and Repellent Properties of Baccharis Salicifolia Essential Oil against the Stored Product Pest of Neltuma Alba, Riphibruchus Picturatus (F.) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Bruchinae): Chemical Composition and Mechanism of Action. South African Journal of Botany 2025, 184, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjørve, E. Shapes and Functions of Species–Area Curves: A Review of Possible Models. Journal of Biogeography 2003, 30, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, E.; Ghaderi-Far, F.; Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. Problems with Using Mean Germination Time to Calculate Rate of Seed Germination. Aust. J. Bot. 2015, 63, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. CoreTeam R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2024 2024.

- Nóbrega, J.S.; de Lucena Alcântara Bruno, R.; Gleide da Silva, L.; Lima, L.K.S.; Nunes de Medeiros, A.; Pereira de Andrade, A.; Rodrigues Magalhães, A.L.; Rufino de Lima, C. Seed Recovery of Native Plant Species of the Caatinga Biome Ingested by Goats and Its Effect on Seed Germination, in Brazilian Semiarid Region. Arid Land Research and Management 2024, 38, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, D.; Mancilla-Leytón, J.M.; Delgado-Pertiñez, M.; Martín-Vicente, A. Endozoochorus Seed Dispersal by Goats: Recovery, Germinability and Emergence of Five Mediterranean Shrub Species. Span. j. agric. res. 2013, 11, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancilla-Leytón, J.M.; Fernández-Alés, R.; Vicente, A.M. Plant-Ungulate Interaction: Goat Gut Passage Effect on Survival and Germination of Mediterranean Shrub Seeds: Plant-Ungulate Interaction. Journal of Vegetation Science 2011, 22, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneuper, C.L.; Scott, C.B.; Pinchak, W.E. Consumption and Dispersion of Mesquite Seeds by Rumi- Nants. Rangeland Ecology & Management/Journal of Range Management Archives 2000.

- Egea, Á.V.; Campagna, M.S.; Cona, M.I.; Sartor, C.; Campos, C.M. Experimental Assessment of Endozoochorous Dispersal of Prosopis Flexuosa Seeds by Domestic Ungulates. Applied Vegetation Science 2022, 25, e12651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasuriya, K.M.G.G.; Baskin, J.M.; Geneve, R.L.; Baskin, C.C. A Proposed Mechanism for Physical Dormancy Break in Seeds of Ipomoea Lacunosa (Convolvulaceae). Annals of Botany 2009, 103, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider Ali, H.; Tanveer, A.; Ather Nadeem, M.; Naeem Asghar, H. Methods to Break Seed Dormancy of Rhynchosia Capitata, a Summer Annual Weed. Chilean J. Agric. Res. 2011, 71, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaganathan, G.K.; Yule, K.; Liu, B. On the Evolutionary and Ecological Value of Breaking Physical Dormancy by Endozoochory. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 2016, 22, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancilla Leytón, J.M.; Fernández-Alés, R.; Martín Vicente, Á. Seed dispersal effectiveness of shrubs by goat. ECOS 2015, 24, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).