Submitted:

30 September 2024

Posted:

01 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

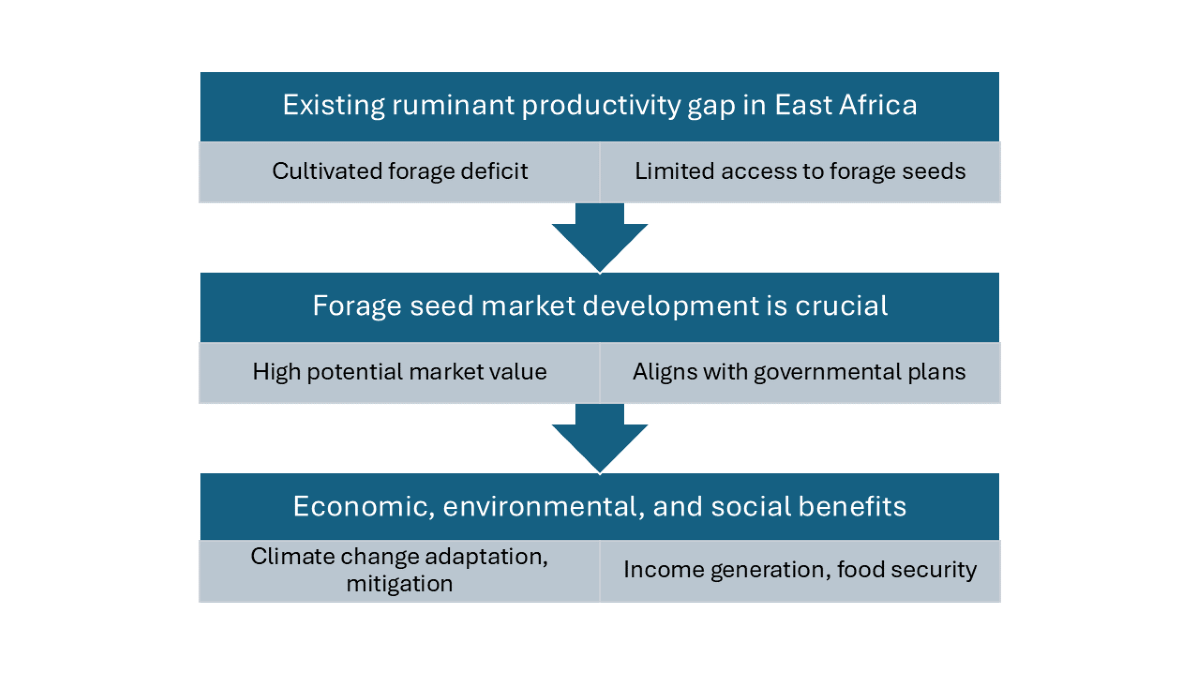

Highlights

- Governments prioritize forages to boost livestock productivity and sustainability

- East Africa faces a 40% annual feed deficit, impacting food security and livelihoods

- Cultivated forage seed requirement: 95,605 tons for 10% adoption over 10 years

- 2M hectares and 1.5M farmers are needed to close the forage deficit in the region

- Regional forage seed market could reach US$877 billion over 10 years

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Scenario 1: Where 100% of the identified is covered in the first year by simultaneously planting the two grass species at 35% each and the two legume species at 15% each. This scenario considers a 10-year evaluation horizon, the annual seed requirements for reseeding the legumes, and regeneration seed for the grasses for the last three years at 100%.

- Scenario 2: Where 10% of the identified is covered in the first year by simultaneously planting the two grass species at 35% each and the two legume species at 15% each. We projected a 10% annual increase in covering the and a lifespan of 7 years for the perennial grasses (Jank et al., 2014). For the two longer-term perennial grasses (Megathyrsus maximus, Urochloa hybrids), we included annual regeneration seed in the calculation after year 7 at 100%. The projected horizon for our calculations is 10 years.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Governmental Plans for the Livestock Sector in the Studied Countries

| Country | Focus and aspirations |

| Ethiopia | The Ethiopian government plans to quadruple milk production by 2031 by enhancing the productivity of dairy cows, camels, and goats. This goal is a key focus of the government’s ten-year strategic plan for the dairy sector. The plan aims to address significant challenges related to genetics, technology, feeding, health, marketing of inputs and outputs, value addition, product quality, and consumer safety (Legese et al., 2023). Ethiopia’s Livestock Master Plan (Shapiro et al., 2015) emphasizes the importance of forages in improving livestock productivity. The plan addresses forage shortages, particularly during dry periods, by promoting the cultivation of improved forage varieties and better pasture management. The government supports research and development of high-yielding forage crops and the integration of forage production into mixed farming systems. Additionally, there are efforts to enhance the dissemination of forage technologies and improve farmers’ access to quality seeds. By prioritizing forages, Ethiopia aims to boost livestock productivity and support the livelihoods of pastoral and agro-pastoral communities. |

| Tanzania | By 2025, the livestock sector is expected to be largely commercial, modern, and sustainable, leveraging improved and highly productive livestock to ensure food security, boost household and national income, and support environmental conservation (Ministry of Livestock Development Tanzania, 2006). Both Tanzania’s National Livestock Policy (Ministry of Livestock Development Tanzania, 2006) and Livestock Sector Transformation Plan (Ministry of Livestock and Fisheries Tanzania, 2022) prioritize the development and use of forages to modernize the livestock sector. The policy emphasizes the need for improved forage resources and sustainable feed management practices. The government promotes the cultivation of high-quality forage crops and supports research on forage technologies. Additionally, there are initiatives to enhance the availability of forage seeds and improve pasture management. By focusing on forages, Tanzania seeks to address feed scarcity, increase livestock productivity, and contribute to the overall development of the sector. |

| Kenya | Kenya’s Livestock Policy (Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Cooperatives Kenya, 2020) aims to harness livestock resources to enhance food and nutrition security and improve livelihoods while protecting the environment. This objective will be met through several measures, including improved management of livestock, feed, and rangeland resources, as well as promoting social inclusion and environmental resilience. Interventions in livestock nutrition, feeds, and feeding will involve various measures focused on roughage and concentrate feed resources. These measures will ensure the availability of adequate forage resources by enhancing the productivity and utilization of diverse roughage materials. Forages are thus a key component in improving livestock productivity and sustainability. The plan advocates for the development of improved forage varieties and the adoption of better forage management practices. The government supports the cultivation of forage crops, the use of high-quality feed supplements, and the establishment of forage banks to ensure availability during dry periods. Furthermore, there are initiatives to educate farmers on effective forage management through extension services. By prioritizing forages, Kenya aims to enhance livestock performance and support pastoral and agro-pastoral livelihoods. |

| Uganda | Uganda’s National Animal Feeds Policy (Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries Uganda, 2005) aims to address challenges in the livestock sector by improving the quality, availability, and affordability of animal feeds. This policy, first introduced in 2005, aligns with Uganda’s broader agricultural development strategy, particularly its Plan for the Modernization of Agriculture. The policy seeks to ensure optimal use of local feed resources, which would improve livestock productivity and increase the supply of animal products. The recent Animal Feeds Act (The Republic of Uganda, 2024) builds on this policy by introducing more stringent regulations for the production, sale, and transportation of animal feeds. It mandates licensing for all stakeholders involved in these activities and seeks to control the quality of animal feeds by regulating imports and exports. The Act also includes provisions for penalties for non-compliance, especially in cases involving counterfeit or low-quality feeds, which have been problematic in the sector. Additionally, inspectors will be empowered to ensure that feeds meet safety and nutritional standards. This policy and its legislative updates are expected to enhance Uganda’s livestock productivity by improving feed quality, reducing animal diseases linked to poor nutrition, and ultimately supporting the country’s growing livestock sector Uganda’s Livestock Sector Prioritization under the Agriculture Sector Strategic Plan (ASSP) (Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries Uganda, 2016) recognizes the role of forages in enhancing livestock productivity. The plan includes strategies to boost forage production through the development of improved forage varieties and the promotion of sustainable forage management practices. The government supports research and development in forage technologies and encourages private sector involvement in forage production. Additionally, efforts are made to improve the distribution of forage seeds and enhance farmers’ knowledge of forage cultivation. By prioritizing forages, Uganda aims to address feed shortages and support smallholder farmers. |

| Rwanda | Rwanda’s 5th Strategic Plan for Agricultural Transformation (PSTA5) highlights the crucial role of the livestock sector in the country’s economic growth and development from 2024 to 2030. The Rwandan government has established several targets for the sector, including boosting milk production from 785 million liters in 2018 to 1.5 billion liters by 2024, and expanding the national herd size from 1.5 million to 2.5 million (FAO, 2024). Rwanda’s National Livestock Policy and Livestock Master Plan (Shapiro et al., 2017) emphasize the importance of forages in increasing livestock productivity and sustainability. The plans focus on improving forage resources and management practices, including the cultivation of high-quality forage crops and the development of forage technologies. The government also supports integrated approaches that combine forage production with other agricultural activities to maximize resource use. By prioritizing forages, Rwanda aims to enhance livestock performance and contribute to food security and rural development. |

| Burundi | Burundi’s National Plan for Development (PND, 2018) focuses on enhancing productivity, encouraging private sector investment, and strengthening the capabilities of public and private institutions. Burundi’s National Agricultural Investment Plan (Ministere de L’Agriculture et de L’Elevage Burundi, 2011) places a strong emphasis on increasing livestock productivity through improved feeding systems, including the use of cultivated forages. The plan highlights the need for expanding forage cultivation to reduce the country’s dependence on natural pastures, which are often overgrazed and degraded. |

3.2. Annual Ruminant Feed Demand, Feed Deficit, and Cultivated Forage Deficit in the Region

3.3. Annual Forage Seed Requirements for Bridging the Regional Cultivated Forage Deficit

3.4. Land and farmers required in the forage adoption process

3.5. The Role of Vegetative Propagation in the Forage Adoption Process

3.6. Estimated Value of the Regional Forage Seed Market and Potential Forage Crop Value Generation

3.7. Developing the Forage Seed Market and Ensuring Forage Adoption

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Enhance feed and forage policy integration: Governments should enhance the integration of feed and forage policies with broader livestock sector strategies. This includes aligning forage production initiatives with overall livestock productivity and environmental sustainability goals. They should also emphasize the adoption of sustainable forage management practices to improve feed quality and availability. Likewise, policies that balance economic, environmental, and social objectives in forage production should be developed.

- Address feed and forage deficits: Strategies to significantly boost the availability of forage seeds should be developed. This could involve supporting seed production initiatives, reducing seed prices, and improving seed distribution channels. Investments in research to develop high-yielding and climate-resilient forage varieties is essential. Collaboration with international research organizations can help accelerate the development of suitable forage crops for the region.

- Improve seed systems and distribution: Regional trade blocs such as COMESA and EAC should be used to streamline the registration and movement of forage varieties across borders. This can reduce bureaucratic delays and enhance seed accessibility. Efficient seed distribution models that involve seed companies and producer associations should be developed to improve access to seeds in rural areas. Logistics and supply chain solutions to ensure timely delivery of forage seeds should be established.

- Support of farmers and land use: Comprehensive training and extension services to farmers on forage cultivation and management are essential. This should include practical advice on the use of forage technologies and addressing common challenges in forage production. Innovative land management practices should be explored to maximize the use of available land for forage cultivation. Policies that mitigate competition between livestock and crop production and promote sustainable land use planning should be developed.

- Enhance market incentives: Economic incentives for seed companies to enter and invest in the forage seed market should be created. This could involve subsidies, tax breaks, or public-private partnerships to support the development of the seed industry. The forage seed value chain should be developed by encouraging private sector involvement, improving market infrastructure, and fostering demand creation for forage crops.

- Address adoption barriers: Barriers related to high seed prices and limited seed availability should be addressed. This could involve subsidies or financial support mechanisms (e.g., credits) for farmers adopting improved forage varieties. Likewise, social, economic, and environmental factors that influence adoption rates must be addressed, e.g., through developing targeted interventions to overcome risk aversion, labor constraints, and other barriers to successful technology adoption.

- Monitor and evaluate adoption: Robust monitoring and evaluation systems to track progress in forage adoption, seed distribution, and impact on livestock productivity should be established. Data derived from such systems can be used to refine strategies and make evidence-based adjustments to policies and programs.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agroduka Limited (2024a). Brachiaria Hybrid Grass. Brachiaria Mulato II. https://agroduka.com/bracharia-hybrid-grass?srsltid=AfmBOooMq-FgEut_PQ_lO8VH5GAz_BFtsGUlxbSeDvzObp3QelMM3NJF.

- Agroduka Limited (2024b). Mombasa Grass (Panicum siambasa). https://agroduka.com/mombasa-grass-1kg-uf-?srsltid=AfmBOoqc63scT23wtzyTxselKMjRxU2JJCO-ReSLVI0tnt83cju3Jrz_.

- Alemu, B., Efrem, G., Zewudu, E., Habtemariam, K. (2015). Land use and land cover changes and associated driving forces in North Western Lowlands of Ethiopia. International Research Journal of Agricultural Science and Soil Science, 5 (1), 28-44. [CrossRef]

- Arango, J., Moreta, D., Nuñez, J., Hartmann, K., Dominguez, M., Ishitani, M., Miles, J., Subbarao, G., Peters, M., Rao, I. (2013). Developing methods to evaluate phenotypic variability in Biological Nitrification Inhibition (BNI) capacity of Brachiaria grasses. In: Michalk, D.L., Millar, G.D., Badgery, W.B. and Broadfoot, K.M. (eds.). 2013. Revitalising grasslands to sustain our communities: Proceedings of the XXII International Grassland Congress, Sydney, Australia, 15-19 September 2013. Australia: New South Wales Department of Primary Industry: 1517. [CrossRef]

- Bacigale, S.B., Nabahungu N.L., Okafor, C., Manyawu, G.J., Duncan, A. (2018). Assessment of livestock feed resources and potential feed options in the farming systems of Eastern DR Congo and Burundi. CLiP Working Paper 1. Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/100726.

- Bahta, S., Malope, P. (2014). Measurement of competitiveness in smallholder livestock systems and emerging policy advocacy: An application to Botswana. Food Policy, 49(Pt 2), 408–417. [CrossRef]

- Burkart, S. (2024). Global estimated CIAT Urochloa hybrid adoption, 2001-2023. LINK to come soon.

- Burkart, S. (2023). A public-private partnership for the dissemination of Urochloa hybrids: Impacts, potential, constraints. International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT). https://hdl.handle.net/10568/132674.

- Cohn, A.S., Mosnier, A., Havlík, P., Valin, H., Herrero, M., Schmid, E., O’Hare, M., Obersteiner, M. (2014). Cattle ranching intensification in Brazil can reduce global greenhouse gas emissions by sparing land from deforestation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences United States of America, 111(20), 7236–7241. 7236. [CrossRef]

- COMESA, ACTESA (2014) COMESA Seed Trade Harmonization Regulations. Lusaka, Zambia: Alliance for Commodity Trade in Eastern and Southern Africa (ACTESA). https://www.aatf-africa.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/COMESA-Seed-Trade-Harmonisation-Regulations-English.pdf.

- Creemers, J., Opinya, F.A. (2022). Advancing forage seed market in Uganda.

- Creemers, J., Alvarez-Aranguiz, A. (2019). Regional dairy policy brief. “Dairy the motor for healthy growth”. East Africa’s Forage Sub-Sector—Pathways to intensified sustainable forage production. Report. NEADAP. https://edepot.wur.nl/511474.

- Creemers, J., Maina, D., Opinya, F., Maosa, S. (2021). Forage value chain analysis for the counties of Taita Taveta, Kajiado and Narok. Final report of a scan of forage seed suppliers in Kenya (private companies and research institutions). SNV, KALRO. https://cowsoko.com/storage/publications/gisjh5y2lbDg.

- DAI. (2023). Improving livestock markets to generate economic growth and resilience in East Africa. https://dai-global-developments.com/articles/improving-livestock-markets-to-generate-economic-growth-and-resilience-in-east-africa/.

- de Haan, C. (2016). Prospects for Livestock-Based Livelihoods in Africa’s Drylands. A World Bank Study. World Bank: Washington, DC, USA. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/485591478523698174/pdf/109810-PUB-Box396311B-PUBLIC-DOCDATE-10-28-16.pdf?_gl=1*oba2d5*_gcl_au*OTM4MzI1NTYxLjE3MjY1OTQ1NjM.

- de Oto, L., Vrieling, A., Fava, F., de Bie, K.C.A.J.M. (2019). Exploring improvements to the design of an operational seasonal forage scarcity index from NDVI time series for livestock insurance in East Africa. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 82, 101885. [CrossRef]

- Dey, B. (2021). Adoption of cultivated forages and potential impact: The case of ethiopia. AgriLinks. https://www.agrilinks.org/post/adoption-cultivated-forages-and-potential-impact-case-ethiopia.

- Dey, B., Notenbaert, A., Makkar, H., Mwendia, S., Sahlu, Y., Peters, M. (2022). Realizing economic and environmental gains from cultivated forages and feed reserves in Ethiopia. CABI Reviews, 17(010). [CrossRef]

- East African Community. (2022). Livestock development. Agriculture & Food Security. https://www.eac.int/agriculture/livestock-development/63-sector/agriculture-food-security.

- Edwards, F.A., Massam, M.R., Cosset, C.C.P., Cannon, P.G., Haugaasen, T., Gilroy, J.J., Edwards, D.P. (2021). Sparing land for secondary forest regeneration protects more tropical biodiversity than land sharing in cattle farming landscapes. Current Biology, 31(6), 1284–1293. [CrossRef]

- Eleni, Y., Wolfgang, W., Michael, E., Dagnachew, L., Gunter, B. (2013). Identifying Land Use/Cover Dynamics in the Koga Catchment, Ethiopia, from Multi-Scale Data, and Implications for Environmental Change. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 2(2), 302–323. [CrossRef]

- FAO (2018). Ethiopia: Report on feed inventory and feed balance 2018. Rome, IT: FAO. https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/d9d97dc5-6414-4dc2-8365-858c797de6b5/content.

- FAO (2018). World livestock: Transforming the livestock sector through the sustainable development goals. Rome, IT: FAO. https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/ca1201.

- FAO (2024). Family Farming Knowledge Platform. Smallholders dataportrait. Rome, IT: FAO. https://www.fao.org/family-farming/data-sources/dataportrait/farm-size/en/.

- FAO (2024). Rwanda’s 5th Strategic Plan for Agricultural Transformation (PSTA5). Rome, IT: FAO. https://www.fao.org/food-systems/news-events/news-detail/en/c/1641280/.

- FAO and IGAD (2019). East Africa Animal Feed Action Plan. Rome, IT: FAO. https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/19c3471b-fdb8-4dfd-83da-0ee5c80c3544/content#:~:text=The%20Animal%20Feed%20Action%20Plan,competitiveness%20and%20profitability%20and%20ensuring.

- Felis, A. (2020). The multidimensional role of livestock in Africa. ICE, Economic Journal, 914, 79–96. [CrossRef]

- Florez, J.F., Karimi, P., Paredes, J.J.J., Ángel, N.T., Burkart, S. (2024). Developments, bottlenecks, and opportunities in seed markets for improved forages in East Africa: The case of Kenya. Grassland Research 3(10, 79-96. [CrossRef]

- Greenspoon (2024). Pearl Lablab Beans (Njahi) – 1Kg. https://greenspoon.co.ke/product/pearl-lablab-beans-njahi-1kg/.

- Habiyaremye, N., Ouma, E.A., Mtimet, N., Obare, G.A. (2021). A Review of the Evolution of Dairy Policies and Regulations in Rwanda and Its Implications on Inputs and Services Delivery. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 8, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Hare, M.D., Pizarro, E.A., Phengphet, S., Songsiri, T. and Sutin, N. (2015). Evaluation of new hybrid brachiaria lines in Thailand. 2. Seed production. Tropical Grasslands-Forrajes Tropicales 3(2), 94–103. [CrossRef]

- IGAD (2021). Seed Systems Analysis in the IGAD region. Final report.

- Jank, L., Barrious, S., do Valle, C., Simeao, R., Alves, G. (2014). The value of improved pastures to Brazilian beef production. Crop Pasture Science 65, 1132–1137. [CrossRef]

- Junca Paredes, J.J., Florez, J.F., Enciso Valencia, K.J., Hernández Mahecha, L.M., Triana Ángel, N., Burkart, S. (2023). Potential Forage Hybrid Markets for Enhancing Sustainability and Food Security in East Africa. Foods, 12, 1607. [CrossRef]

- Karimi, P., Ugbede, J., Enciso, K., Burkart, S. (2022). Cost-benefit analysis for on-farm management options of improved forage varities in western Kenya. Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/119258.

- Legese, G., Gelmesa, U., Jembere, T., Degefa, T., Bediye, S., Teka, T., Temesgen, D., Tesfu, Y., Berhe, A., Gemeda, L., Takele, D., Beyene, G., Belachew, G. Hailu, G., Chemeda, S. (2023). Ethiopia National Dairy Development Strategy 2022–2031. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ministry of Agriculture, Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/135703.

- Little, P.D., Debsu, D.N., Tiki, W. (2014). How pastoralists perceive and respond to market opportunities: The case of the horn of Africa. Food Policy 49, 389–397. [CrossRef]

- Macedo Pezzopane, J.R., Nicodemo, M.L.F., Bosi, C., Garcia, A.R., Lulu, J. (2019). Animal thermal comfort indexes in silvopastoral systems with different tree arrangements. Journal of Thermal Biology 79, 103–111. [CrossRef]

- Maina, K.W., Ritho, C.N., Lukuyu, B.A., Rao, E.J.O. (2022). Opportunity cost of adopting improved planted forage: Evidence from the adoption of Brachiaria grass among smallholder dairy farmers in Kenya. African Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 17(1), 48–63. [CrossRef]

- Mary, T., Ewa, W., Elly, N.S., Denis, M. (2016). Feed resource utilization and dairy cattle productivity in the agro-pastoral system of South Western Uganda. African Journal of Agricultural Research 11(32), 2957–2967. [CrossRef]

- Mekuria, W., Mekonnen, K., Thorne, P. et al. (2018). Competition for land resources: driving forces and consequences in crop-livestock production systems of the Ethiopian highlands. Ecol Process 7, 30. [CrossRef]

- Ministere de L’Agriculture et de L’Elevage Burundi (2011). Plan National D’Investissement Agricole (PNIA) 2012-2017. Bujumbura, Burundi: Ministere de L’Agriculture et de L’Elevage. https://www.resakss.org/sites/default/files/pdfs//burundi-national-agricultural-investment-plan-2012-50991.pdf.

- Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Burundi (2012). Global Agriculture and Food Security Program. Bujumbura: Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Burundi. https://www.gafspfund.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/2-Burundi%20GAFSP%20Proposal.pdf.

- Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries Uganda (2005). The national animal feeds policy. Kampala, Uganda: Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries. https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/uga181883.pdf. =.

- Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries Uganda (2016). Agriculture Sector Strategic Plan 2015/16-2019/2020. Kampala, Uganda: Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries. https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/uga181565.pdf.

- Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Cooperatives Kenya (2020). Sessional Paper No. 3 of 2020 on The Livestock Policy. Nairobi, Kenya: Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Cooperatives. https://kilimo.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Livestock-Policy-Sessional-Paper-Number-3-of-2020-2.pdf.

- Ministry of Livestock and Fisheries Tanzania (2022). Livestock Sector Transformation Plan (LSTP) 2022/23-2026/27. Dodoma, Tanzania: Ministry of Livestock and Fisheries. https://www.mifugouvuvi.go.tz/uploads/publications/sw1675840376-LIVESTOCK%20SECTOR%20TRANSFORMATION%20PLAN%20(LSTP)%20202223%20-%20202627.pdf.

- Montagnini, F., Ibrahim, M., Murgueitio Restrepo, E. (2013). Silvopastoral systems and climate change mitigation in Latin America. Bois & Forêts des Tropiques, 67(316), 3–16. [CrossRef]

- Moritz, M. (2013). Livestock transfers, risk management, and human careers in a West African pastoral system. Human Ecology, 41(2), 205–219. [CrossRef]

- Mwendia, S., Ohmstedt, U., & Peters, M. (2020). Review of forage seed regulation framework in Kenya. Alliance of Bioversity and CIAT. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/111371.

- Naranjo Ramírez, J.F., Tarazona Morales, A.M., Murgueitio Restrepo, E., Chará Orozco, J.D., Ku Vera, J., Solorio Sánchez, F.J., Flores Estrada, M.X., Solorio Sánchez, B., Barahona Rosales, R. (2014). Contribution of intensive silvopastoral systems to animal performance and to adaptation and mitigation of climate change. Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Pecuarias, 27(2), 76–94. [CrossRef]

- Narjes Sanchez, M.E., Cardoso Arango, J.A., Burkart, S. (2021). Promoting forage legume–pollinator interactions: Integrating crop pollination management, native beekeeping and silvopastoral systems in tropical Latin America. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 5, 725981. [CrossRef]

- Ngango, J., Hong, S. (2022). Assessing production efficiency by farm size in Rwanda: A zero-inefficiency stochastic frontier approach. Scientific African 16, e01143. [CrossRef]

- Njuki, J., Mburu, S. (2013). Gender and ownership of livestock assets. In J. Njuki, E. Waithanji, J. Lyimo-Macha, J. Kariuki, Mburu, S. (Eds.), Women, livestock ownership and markets: Bridging the gender gap in Eastern and Southern Africa. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Osiemo, J., Waluse, K., Karanja, S., An, M., Notenbaert, O. (2024). Are dairy farmers willing to pay for improved forage varieties? Experimental evidence from Kenya. Food Policy, 102615. [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.K., Butterbach-Bahl, K., Notenbaert, A., Nduah Nderi, A., Ericksen, P. (2021). Sustainable livestock development in low- and middle-income countries: Shedding light on evidence-based solutions. Environmental Research Letters 16(1), 011001. [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.K., Koge, J., Maass, B.L., Notenbaert, A., Peters, M., Groot, J.C.J., Tittonell, P. (2020). Tropical forage technologies can deliver multiple benefits in sub-Saharan Africa. A meta-analysis. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 40, 22. [CrossRef]

- PND (2018). National Plan for the Development of Burundi 2018-2027. https://climate-laws.org/documents/national-plan-for-the-development-of-burundi-2018-2027-pnd-burundi-2018-2027_dfc5?id=national-plan-for-the-development-of-burundi-2018-2027-pnd-burundi-2018-2027_e36c.

- Rao, I., Peters, M., Castro, A., Schultze-Kraft, R., White, D., Fisher, M., Miles, J., Lascano, C., Blummel, M., Bungenstab, D., Tapasco, J., Hyman, G., Bolliger, A., Paul, B., Van Der Hoek, R., Maass, B., Tiemann, T., Cuchillo, M., Douxchamps, S., … Rudel, T. (2015). LivestockPlus—The sustainable intensification of forage-based agricultural systems to improve livelihoods and ecosystem services in the tropics. Tropical Grasslands-Forrajes Tropicales 3, 59–82. [CrossRef]

- Robran Mall (2024). Lablab per kg. https://robranmall.com/product/lablab-per-kg/.

- Schiek, B., González, C., Mwendia, S., Prager, S.D. (2018). Got forages? Understanding potential returns on investment in Brachiaria spp. for dairy producers in Eastern Africa. Tropical Grasslands-Forrajes Tropicales 6(3), 117–133. [CrossRef]

- Selina Wamucii (2024a). Tanzania Cow Peas (Black Eyed Peas) Prices. https://www.selinawamucii.com/insights/prices/tanzania/cow-peas-black-eyed-peas/.

- Selina Wamucii (2024b). Ethiopia Cow Peas (Black Eyed Peas) Prices. https://www.selinawamucii.com/insights/prices/ethiopia/cow-peas-black-eyed-peas/.

- Selina Wamucii (2024c). Uganda Cow Peas (Black Eyed Peas) Prices. https://www.selinawamucii.com/insights/prices/uganda/cow-peas-black-eyed-peas/.

- Selina Wamucii (2024d). Rwanda Cow Peas (Black Eyed Peas) Prices. https://www.selinawamucii.com/insights/prices/rwanda/cow-peas-black-eyed-peas/.

- Selina Wamucii (2024e). Burundi Cow Peas (Black Eyed Peas) Prices. https://www.selinawamucii.com/insights/prices/burundi/cow-peas-black-eyed-peas/. =.

- Shapiro, B.I, Getachew, G., Solomon, D., Nigussie, K. (2017). Rwanda Livestock Master Plan. https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/rwa172923.pdf.

- Shapiro, B.I., Gebru, G., Desta, S., Negassa, A., Negussie, K., Aboset, G., Mechal, H. (2015). Ethiopia Livestock Master Plan. Roadmaps for Growth and Transformation. A Contribution to the Growth and Transformation Plan II (2015-2020). Adis Ababa, Ethiopia: International Livestock Research Institute. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/68037.

- Simlaw Seeds (2024a). Brachiaria Hybrid Grass 1kg. https://simlaw.co.ke/product-details/210/69.

- Simlaw Seeds (2024b). cowpeas k.k.1 1kg. https://www.simlaw.co.ke//product-details/296/99.

- Smale, M., Simpungwe, E., Biroi, E., Sassie, G.T., Groote, H. (2014). The Changing Structure of the Maize Seed Industry in Zambia: Prospects for Orange Maize. Agribusiness 31(1), 132-146. [CrossRef]

- Strauch, B.A., Stockton, M.C. (2017). Feed cost Cow-Q-Lator. NebGuide University of Nebraska. https://extensionpublications.unl.edu/assets/pdf.

- TASAI (The Africa Seed Access Index) (2024). TASAI Dashboard. https://www.tasai.org/en/dashboard/cross-country-dashboard/.

- Tekalign, E. (2014). Forage seed systems in Ethiopia: A scoping study. ILRI. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/65142.

- The Republic of Uganda (2024). The Animal Feeds Act, 2024. Kampala, Uganda: The Republic of Uganda. https://www.parliament.go.ug/cmis/views/e014e205-9cc5-4d21-8e5c-3a0ea6a64024%253B1.0.

- The United Republic of Tanzania (2021). National Sample Census of Agriculture 2019/20. Key findings Report. https://www.nbs.go.tz/index.php/en/census-surveys/agriculture-statistics/659-2019-20-national-sample-census-of-agriculture-key-findings-report#:~:text=The%20National%20Sample%20Census%20of,were%20involved%20in%20agricultural%20activities.

- Tiley, G.E.D. (1959). Elephant grass in Uganda. Kawanda report.

- Tiley, G.E.D. (1969). Elephant Grass. Kawanda Technical Communication No.23, Kawanda Research Station.

- WFP (World Food Programme of the United Nations) (2022). Regional Food Security and Nutrition Update Eastern Africa Region 2022. World Food Programme of the United Nations: Rome, Italy.

| Characteristic | Forage | |||

| Urochloa hybrid | Megathyrsus maximus | Lablab purpureus | Vigna unguiculata | |

| Share of forage deficit to cover (%) | 35 | 35 | 15 | 15 |

| Seed rate (t ha-1) | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Yield (dry matter t ha-1) | 17 | 20 | 8 | 8 |

| Growth type | Perennial | Perennial | Annual | Annual |

| Days to first cut | 90 | 75-90 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Days to regrowth cutting | 30-45 | 30-45 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Days to cutting after sowing | n.a. | n.a. | 90 | 70-90 |

| Lifespan (years) | 8 | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| Adoption rate (%) | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Regeneration seed | 100% after year 7 | 100% after year 7 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Source: based on Dey et al. (2022) | ||||

| Country |

Urochloa hybrids (cv. Mulato II) |

Megathyrsus maximus (cv. Mombasa) |

Lablab purpureus | Vigna unguiculata | ||||

| Current price (US$ t-1) |

Reduced price** (US$ t-1) |

Current price (US$ t-1) |

Reduced price** (US$ t-1) |

Current price (US$ t-1) |

Reduced price** (US$ t-1) |

Current price (US$ t-1) |

Reduced price** (US$ t-1) |

|

| Ethiopia | 50,460 | 37,845 | 48,670 | 36,503 | 6,245* | 4,684* | 9,426 | 7,070 |

| Tanzania | 50,460 | 37,845 | 48,670 | 36,503 | 6,245* | 4,684* | 4,378 | 3,284 |

| Kenya | 43,660 | 32,745 | 48,670 | 36,503 | 2,291 | 1,718 | 1,975 | 1,481 |

| Uganda | 50,460 | 37,845 | 48,670 | 36,503 | 10,199 | 7,649 | 1,485 | 1,113 |

| Rwanda | 50,460 | 37,845 | 48,670 | 36,503 | 6,245* | 4,684* | 4,442 | 3,332 |

| Burundi | 50,460 | 37,845 | 48,670 | 36,503 | 6,245* | 4,684* | 2,719 | 2,040 |

| Notes: all prices in 2023 US$; *no price available, the average price was built for Kenya and Uganda and applied to the countries with no information on prices; **reduced price by 25% to reflect a scenario in which a) some of the seed is produced locally and b) economies of scale apply due to higher seed purchases. Sources: Agroduka Limited (2024a, 2024b); Simlaw Seeds (2024a, 2024b); Robran Mall (2024); Greenspoon (2024); Selina Wamucii (2024a, 2024b, 2024c, 2024d, 2024e). | ||||||||

| Country | Ruminant population | Tropical Livestock Units (TLU) |

Dry matter deficit (%) |

Annual feed demand (dry matter t y-1) |

Annual feed deficit (dry matter t y-1) |

Annual cultivated forage deficit (dry matter t y-1) |

| Ethiopia | 156,968,403 | 64,524,901 | 21.6 | 176,636,918 | 38,153,574 | 8,813,476 |

| Tanzania | 66,900,000 | 27,030,000 | 72.3 | 73,994,625 | 53,498,114 | 12,358,064 |

| Kenya | 69,481,459 | 23,455,031 | 60 | 64,208,147 | 38,524,888 | 8,899,249 |

| Uganda | 32,461,107 | 12,126,138 | 13 | 33,195,304 | 4,315,389 | 996,855 |

| Rwanda | 4,758,591 | 1,199,288 | 42 | 3,283,051 | 1,378,881 | 318,522 |

| Burundi | 2,673,929 | 621,212 | 35 | 1,755,316 | 614,361 | 141,917 |

| Notes: Ruminants include cattle, sheep, goats, and camels. 1 TLU = 250kg Sources: FAO (2018); Federal Democratic of Ethiopia (2022); The United Republic of Tanzania (2021); FAO & IGAD (2019); Mary et al. (2016); Bacigale et al. (2018). | ||||||

| Country | Forages |

Scenario 1: 100% adoption rate, AFSR (t/y1) / FSR (t/10y) |

Scenario 2: 10% adoption rate, AFSR for 10 years (t) | ||||||||||

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5 | Year 6 | Year 7 | Year 8 | Year 9 | Year 10 | FSR (t/10y) | |||

| Ethiopia | Megathyrsus maximus | 463 / 463 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 46 | 463 |

| Urochloa hybrids | 1,452 / 1,452 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 145 | 1,452 | |

| Vigna unguiculata | 2,203 / 22,030 | 220 | 441 | 661 | 881 | 1,102 | 1,322 | 1,542 | 1,763 | 1,983 | 2 | 12,119 | |

| Lablab purpureus | 2,203 / 22,030 | 220 | 441 | 661 | 881 | 1,102 | 1,322 | 1,542 | 1,763 | 1,983 | 2 | 12,119 | |

| Regeneration seed M. maximus | 0 / 139 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 46 | 46 | 46 | 139 | |

| Regeneration seed Urochloa hybrids | 0 / 436 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 145 | 145 | 145 | 436 | |

| Total | 6,321 / 46,556 | 632 | 1,073 | 1,514 | 1,954 | 2,395 | 2,836 | 3,276 | 3,908 | 4,349 | 4,790 | 26,726 | |

| Tanzania | Megathyrsus maximus | 649 / 649 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 649 |

| Urochloa hybrids | 2,035 / 2,035 | 204 | 204 | 204 | 204 | 204 | 204 | 204 | 204 | 204 | 204 | 2,035 | |

| Vigna unguiculata | 3,090 / 30,900 | 309 | 618 | 927 | 1,236 | 1,545 | 1,854 | 2,163 | 2,472 | 2,781 | 3,090 | 3,090 | |

| Lablab purpureus | 3,090 / 30,900 | 309 | 618 | 927 | 1,236 | 1,545 | 1,854 | 2,163 | 2,472 | 2,781 | 3,090 | 3,090 | |

| Regeneration seed M. maximus | 0 / 195 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 65 | 65 | 65 | 195 | |

| Regeneration seed Urochloa hybrids | 0 / 611 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 204 | 204 | 204 | 611 | |

| Total | 8,863 / 65,280 | 886 | 1,504 | 2,122 | 2,740 | 3,358 | 3,976 | 4,594 | 5,480 | 6,098 | 6,716 | 37,474 | |

| Kenya | Megathyrsus maximus | 467 / 467 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 467 |

| Urochloa hybrids | 1,466 / 1,466 | 147 | 147 | 147 | 147 | 147 | 147 | 147 | 147 | 147 | 147 | 1,466 | |

| Vigna unguiculata | 2,225 / 22,250 | 223 | 445 | 667 | 890 | 1,112 | 1,335 | 1,557 | 1,780 | 2,002 | 2,225 | 12,236 | |

| Lablab purpureus | 2,225 / 22,250 | 223 | 445 | 667 | 890 | 1,112 | 1,335 | 1,557 | 1,780 | 2,002 | 2,225 | 12,236 | |

| Regeneration seed M. maximus | 0 / 140 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 47 | 47 | 47 | 140 | |

| Regeneration seed Urochloa hybrids | 0 / 440 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 147 | 147 | 147 | 440 | |

| Total | 6,383 / 47,009 | 638 | 1,083 | 1,528 | 1,973 | 2,418 | 2,863 | 3,308 | 3,946 | 4,391 | 4,836 | 26,986 | |

| Uganda | Megathyrsus maximus | 52 / 52 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 52 |

| Urochloa hybrids | 164 / 164 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 164 | |

| Vigna unguiculata | 249 / 2,490 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 100 | 125 | 150 | 174 | 199 | 224 | 249 | 1,371 | |

| Lablab purpureus | 249 / 2,490 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 100 | 125 | 150 | 174 | 199 | 224 | 249 | 1,371 | |

| Regeneration seed M. maximus | 0 / 16 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 16 | |

| Regeneration seed Urochloa hybrids | 0 / 49 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 16 | 16 | 16 | 49 | |

| Total | 715 / 5,266 | 72 | 121 | 171 | 221 | 271 | 321 | 371 | 442 | 492 | 542 | 3,023 | |

| Rwanda | Megathyrsus maximus | 17 / 17 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 17 |

| Urochloa hybrids | 53 / 53 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 53 | |

| Vigna unguiculata | 80 / 800 | 8 | 16 | 24 | 32 | 40 | 48 | 56 | 64 | 72 | 80 | 438 | |

| Lablab purpureus | 80 / 800 | 8 | 16 | 24 | 32 | 40 | 48 | 56 | 64 | 72 | 80 | 438 | |

| Regeneration seed M. maximus | 0 / 6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | |

| Regeneration seed Urochloa hybrids | 0 / 15 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5 | 5 | 5 | 16 | |

| Total | 228 / 1,683 | 23 | 39 | 55 | 71 | 87 | 103 | 118 | 141 | 157 | 173 | 966 | |

| Burundi | Megathyrsus maximus | 7 / 7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 7 |

| Urochloa hybrids | 23 / 23 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 23 | |

| Vigna unguiculata | 36 / 360 | 4 | 7 | 11 | 14 | 18 | 21 | 25 | 28 | 32 | 36 | 195 | |

| Lablab purpureus | 36 / 360 | 4 | 7 | 11 | 14 | 18 | 21 | 25 | 28 | 32 | 36 | 195 | |

| Regeneration seed M. maximus | 0 / 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 2 | |

| Regeneration seed Urochloa hybrids | 0 / 7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 7 | |

| Total | 102 / 750 | 10 | 17 | 24 | 32 | 39 | 46 | 53 | 63 | 70 | 77 | 430 | |

| Grand Total | 22,612 / 166,543 | 2,261 | 3,838 | 5,414 | 6,990 | 8,566 | 10,143 | 11,720 | 13,981 | 15,557 | 17,134 | 95,605 | |

| Forage | Ethiopia (ha) | Tanzania (ha) | Kenya (ha) | Uganda (ha) | Rwanda (ha) | Burundi (ha) | Total (ha) |

| Megathyrsus maximus | 154,236 | 216,266 | 155,737 | 17,445 | 5,574 | 2,484 | 551,741 |

| Urochloa hybrids | 181,454 | 254,431 | 183,220 | 20,523 | 6,558 | 2,922 | 649,108 |

| Vigna unguiculata | 110,168 | 154,476 | 111,241 | 12,461 | 3,982 | 1,774 | 394,101 |

| Lablab purpureus | 110,168 | 154,476 | 111,241 | 12,461 | 3,982 | 1,774 | 394,101 |

| Total (ha) | 556,027 | 779,648 | 561,438 | 62,890 | 20,095 | 8,953 | 1,989,051 |

| Notes: Based on Dey et al. (2022), the following seed rates were applied: Megathyrsus maximus 3kg/ha; Urochloa hybrids 8kg/ha; Vigna unguiculata and Lablab purpureus 20kg/ha | |||||||

| Country | Average farm size (ha) | Number of farms (total) |

Number of farms (annual, 10% adoption rate) |

| Ethiopia | 1.4 | 397,162 | 39,716 |

| Tanzania | 1.89 | 412,512 | 41,251 |

| Kenya | 0.86 | 652,835 | 65,284 |

| Uganda | 1.51 | 41,649 | 4,165 |

| Rwanda | 0.72 | 27,910 | 2,791 |

| Burundi | 0.5 | 17,907 | 1,791 |

| Total | 1,549,974 | 154,998 | |

| Note: For this analysis, we estimated that each farm is led by a single farmer. Sources: Average farm sizes were consulted from the Family Farming Knowledge Platform of FAO (2024) for Ethiopia, Tanzania, Kenya, and Uganda; for Rwanda, we used Ngango and Hong (2022); for Burundi we used information provided by the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Burundi (2012). | |||

| Country | Scenario | Seed market value (in millions 2023 US$) | ||||

| Megathyrsus maximus* | Urochloa hybrids* | Vigna unguiculata | Lablab purpureus | Total | ||

| Ethiopia | 1a / 1b | 29.28 / 21.96 | 95.22 / 71.42 | 207.69 / 155.77 | 137.60 / 103.20 | 469.79 / 352.34 |

| 2a / 2b | 29.28 / 21.96 | 95.22 / 71.42 | 114.23 / 85.67 | 75.68 / 56.76 | 314.41 / 235.81 | |

| Tanzania | 1a / 1b | 41.05 / 30.79 | 133.52 / 100.14 | 135.26 / 101.45 | 192.94 / 144.70 | 502.78 / 377.08 |

| 2a / 2b | 41.05 / 30.79 | 133.52 / 100.14 | 74.40 / 55.80 | 106.12 / 79.59 | 355.08 / 266.31 | |

| Kenya | 1a / 1b | 29.56 / 22.17 | 83.19 / 62.40 | 43.94 / 32.95 | 50.96 / 38.22 | 207.66 / 155.74 |

| 2a / 2b | 29.56 / 22.17 | 83.19 / 62.40 | 24.16 / 18.12 | 28.03 / 21.02 | 164.95 / 123.71 | |

| Uganda | 1a / 1b | 3.31 / 2.48 | 10.77 / 8.08 | 3.70 / 2.77 | 25.42 / 19.06 | 43.20 / 32.40 |

| 2a / 2b | 3.31 / 2.48 | 10.77 / 8.08 | 2.03 / 1.53 | 13.98 / 10.48 | 30.10 / 22.57 | |

| Rwanda | 1a / 1b | 1.06 / 0.79 | 3.44 / 2.58 | 3.54 / 2.65 | 4.97 / 3.73 | 13.01 / 9.76 |

| 2a / 2b | 1.06 / 0.79 | 3.44 / 2.58 | 1.95 / 1.46 | 2.74 / 2.05 | 9.18 / 6.89 | |

| Burundi | 1a / 1b | 0.47 / 0.35 | 1.53 / 1.15 | 0.96 / 0.72 | 2.22 / 1.66 | 5.19 / 3.89 |

| 2a / 2b | 0.47 / 0.35 | 1.53 / 1.15 | 0.53 / 0.40 | 1.22 / 0.91 | 3.75 / 2.82 | |

| Total | 1a / 1b | 104.73 / 78.55 | 327.68 / 245.76 | 395.09 / 296.32 | 414.11 / 310.58 | 1,241.62 / 931.21 |

| 2a / 2b | 104.73 / 78.55 | 327.68 / 245.76 | 217.30 / 162.98 | 227.76 / 170.82 | 877.47 / 658.11 | |

| Notes: Scenario 1a: 100% adoption rate, 10 years evaluation horizon, current seed prices; Scenario 1b: 100% adoption rate, 10 years evaluation horizon, reduced seed prices by 25%; Scenario 2a: 10% adoption rate, 10 years evaluation horizon, current seed prices; Scenario 2b: 10% adoption rate, 10 years evaluation horizon, reduced seed prices by 25%. *Regeneration seed included. | ||||||

| Country | Scenario | Estimated cultivated forage crop value (in millions 2015 US$) | ||||

| Megathyrsus maximus* | Urochloa hybrids* | Vigna unguiculata | Lablab purpureus | Total | ||

| Ethiopia | 1 / 2 | 1,110 / 611 | 1,110 / 611 | 317 / 175 | 317 / 175 | 2,856 / 1,571 |

| Tanzania | 1 / 2 | 1,557 / 856 | 1,557 / 856 | 445 / 245 | 445 / 245 | 4,004 / 2,202 |

| Kenya | 1 / 2 | 1,121 / 617 | 1,121 / 617 | 320 / 167 | 320 / 167 | 2,883 / 1,586 |

| Uganda | 1 / 2 | 126 / 69 | 126 / 69 | 36 / 20 | 36 / 20 | 323 / 178 |

| Rwanda | 1 / 2 | 40 / 22 | 40 / 22 | 11 / 6 | 11 / 6 | 103 / 57 |

| Burundi | 1 / 2 | 18 / 10 | 18 / 10 | 5 / 3 | 5 / 3 | 46 / 25 |

| Total | 1 / 2 | 3,972 / 2,185 | 3,972 / 2,185 | 1,134 / 616 | 1,134 / 616 | 10,215 / 5,619 |

| Notes: Scenario 1: 100% adoption rate, 10 years evaluation horizon; Scenario 2: 10% adoption rate, 10 years evaluation horizon. | ||||||

| Country | COMESA | IGAD | EAC | SADC | Total memberships |

| Angola | 1 | ||||

| Botswana | 1 | ||||

| Burundi | 2 | ||||

| Comoros | 2 | ||||

| Djibouti | 2 | ||||

| Democratic Republic of Congo | 3 | ||||

| Egypt | 1 | ||||

| Eritrea | 2 | ||||

| Eswatini | 2 | ||||

| Ethiopia | 2 | ||||

| Kenya | 3 | ||||

| Lesotho | 1 | ||||

| Libya | 1 | ||||

| Madagascar | 2 | ||||

| Malawi | 2 | ||||

| Mauritius | 2 | ||||

| Mozambique | 1 | ||||

| Namibia | 1 | ||||

| Rwanda | 2 | ||||

| Seychelles | 2 | ||||

| Somalia | 3 | ||||

| South Africa | 1 | ||||

| South Sudan | 2 | ||||

| Sudan | 2 | ||||

| Tanzania | 2 | ||||

| Tunisia | 1 | ||||

| Uganda | 3 | ||||

| Zambia | 2 | ||||

| Zimbabwe | 2 | ||||

| Total member countries | 21 | 8 | 8 | 16 | |

| Note: Shaded cells indicate membership | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).