Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

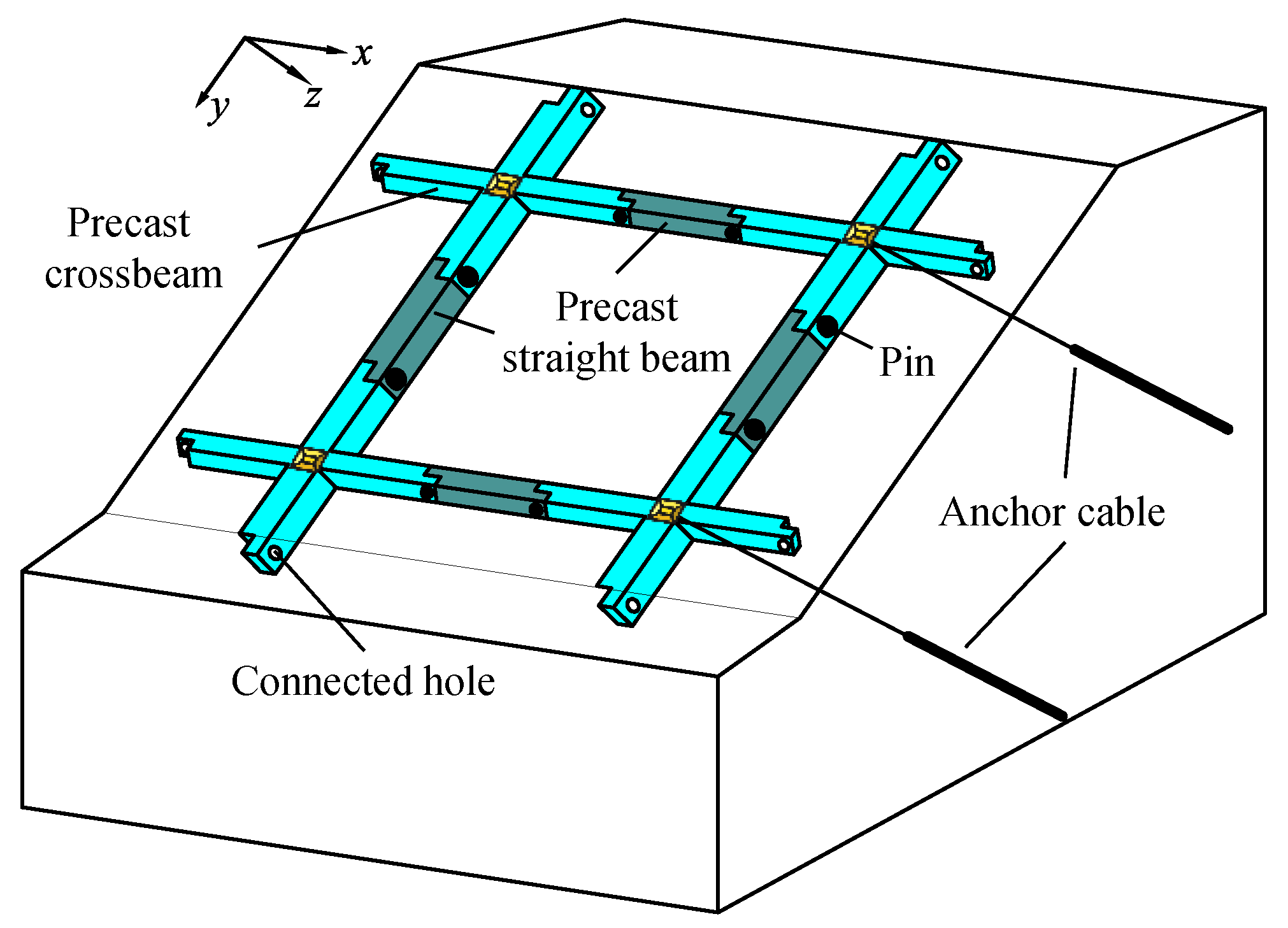

2. Structural Analysis Framework for HPFB Structures

2.1. Basic Assumptions

- (1)

- The self-weight of the precast components and the frictional resistance at the beam-soil interface are neglected;

- (2)

- Only the component of anchor cable prestress perpendicular to the slope surface is considered, idealized as a concentrated load applied at the anchorage point and distributed to both the horizontal and longitudinal segments of the crossbeam;

- (3)

- Torsional interactions between orthogonally oriented beams are neglected. Specifically, bending moments in a beam along one direction are assumed not to induce torsion in perpendicular beams and are fully resisted within the originating beam;

- (4)

- Transverse stress propagation through the subgrade is neglected, with the underlying soil modeled as a Winkler elastic foundation.

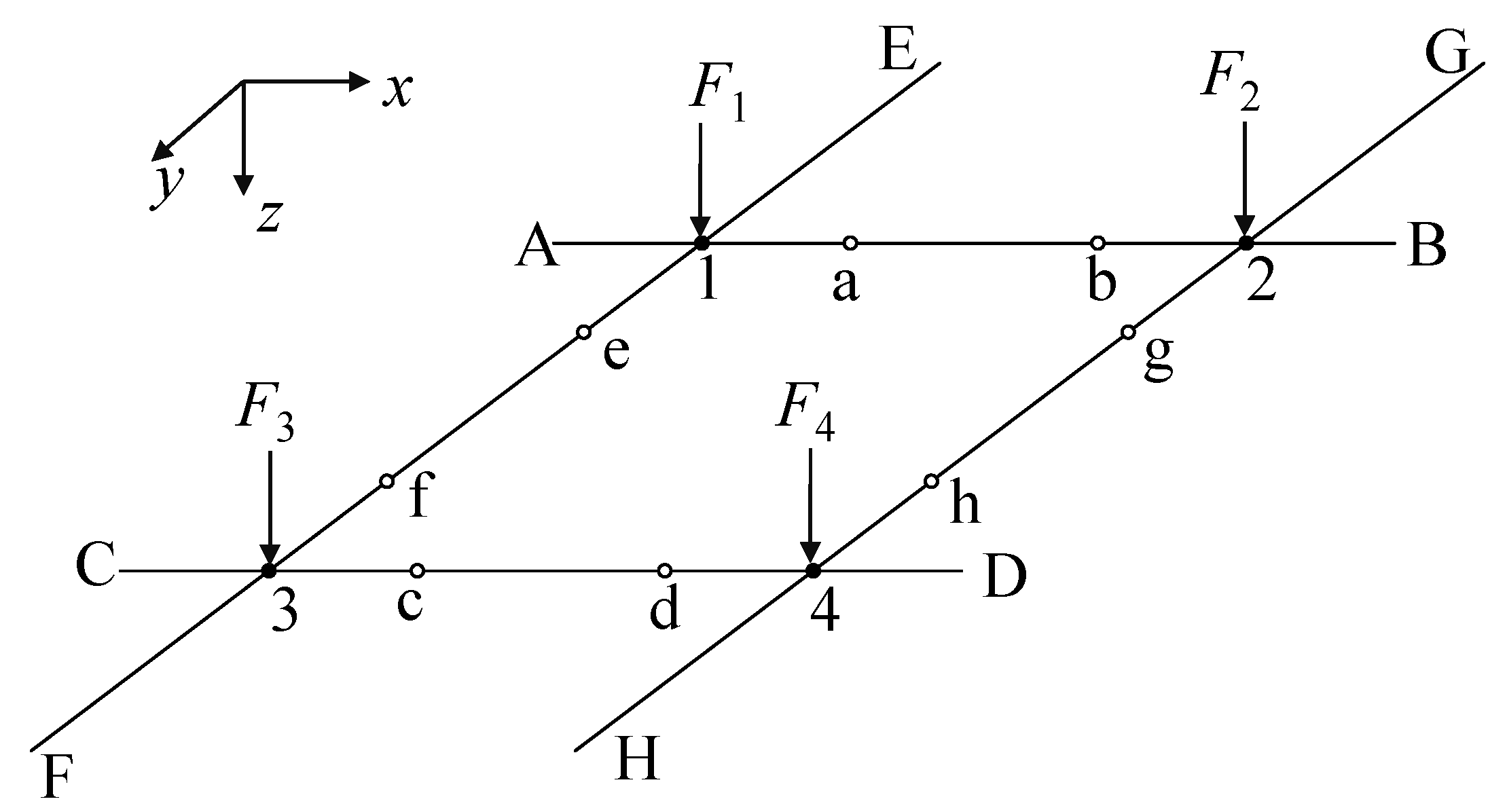

2.2. Structural Decomposition

- (1)

- Loads F1x, F2x, F3x, and F4x are allocated to the horizontal beams AB and CD at anchor points 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively;

- (2)

- Loads F1y, F3y, F2y, and F4y are assigned to the longitudinal beams EF and GH at anchor points 1, 3, 2, and 4, respectively.

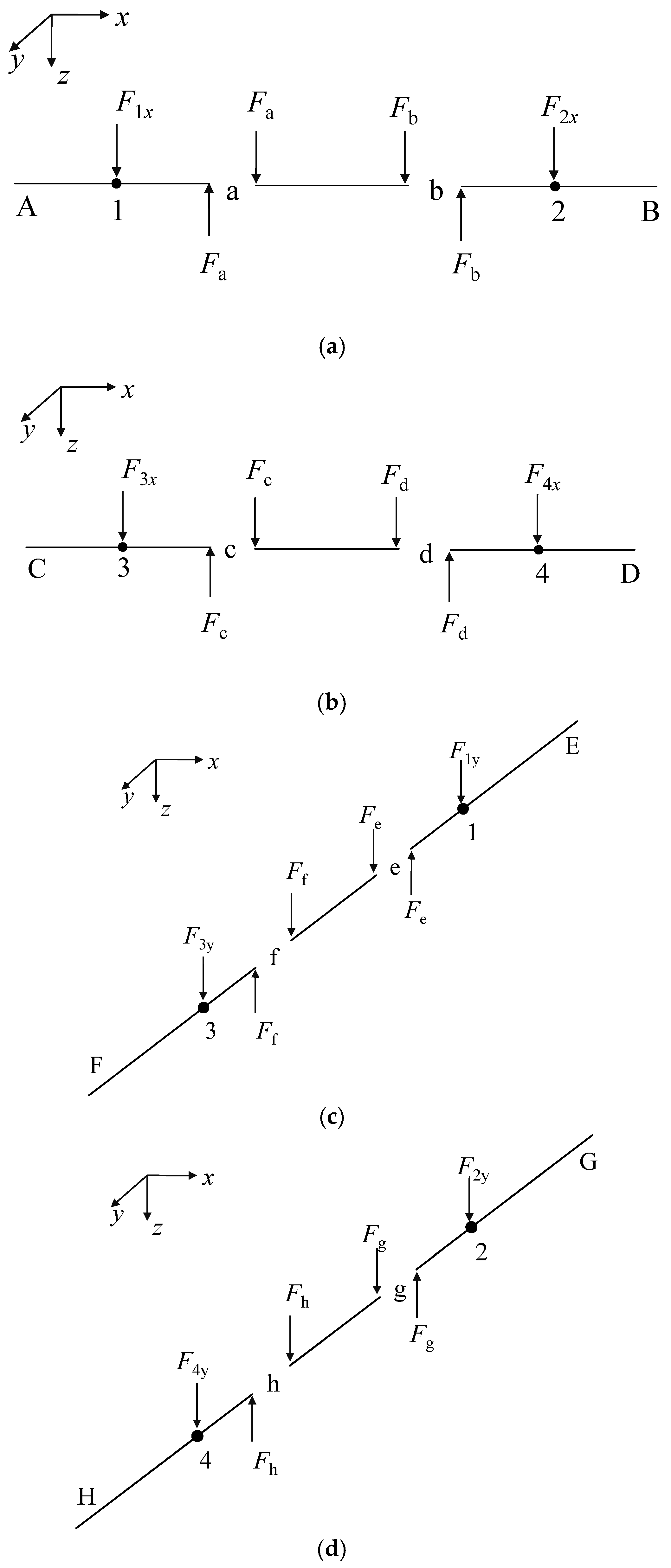

2.3. Load Distribution and Beam-End Shear Forces Determination

2.3.1. Analysis of Anchor Points

2.3.2. Analysis of Hinged Points

2.3.3. Formulation and Solution of a System of Linear Equations

2.4. Analysis of Deformation and Internal Forces for Beam Segments

3. Case Study and Results

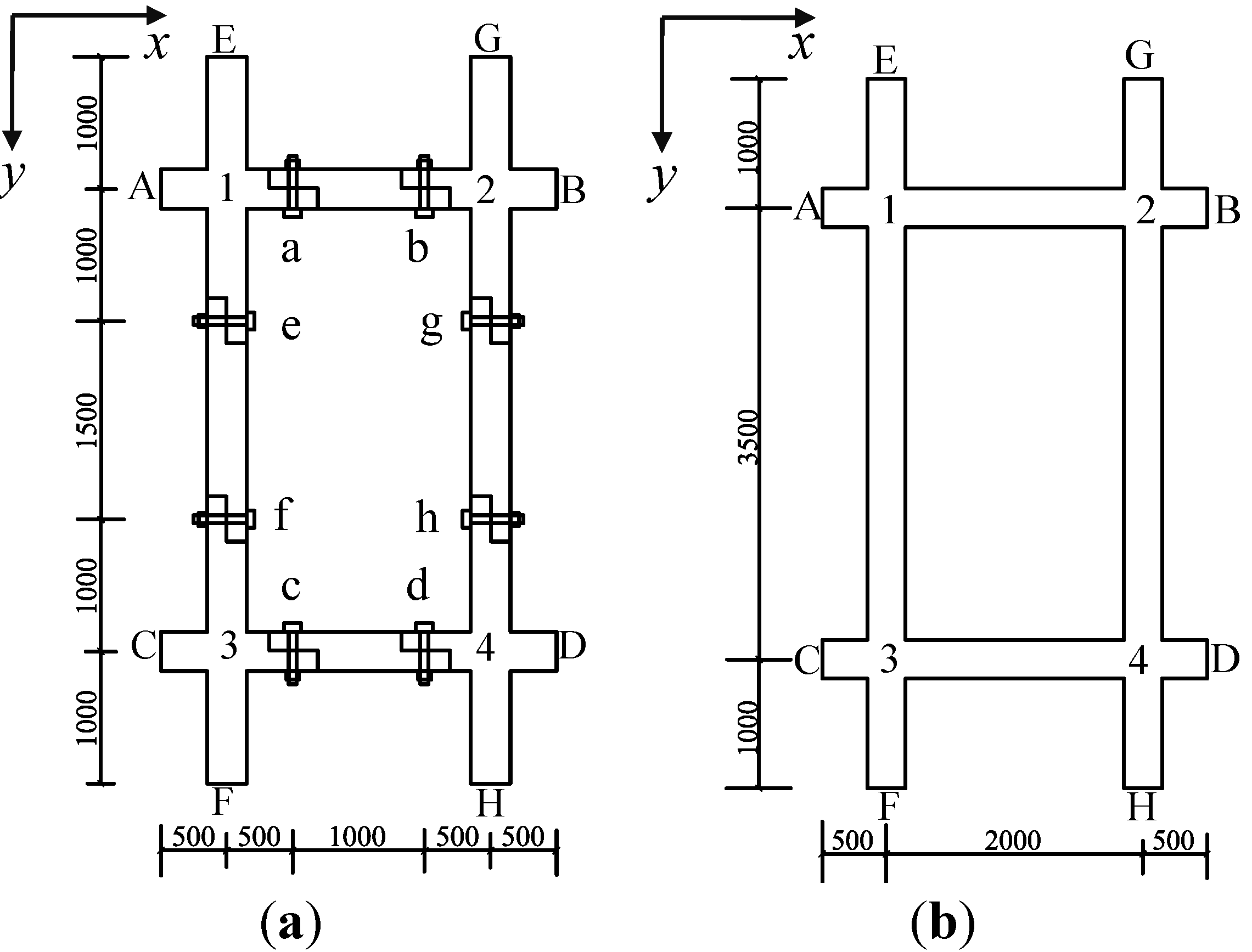

3.1. Project Overview

3.2. Comparative Analysis

3.2.1. Load Distribution and Verification of Deformation Compatibility

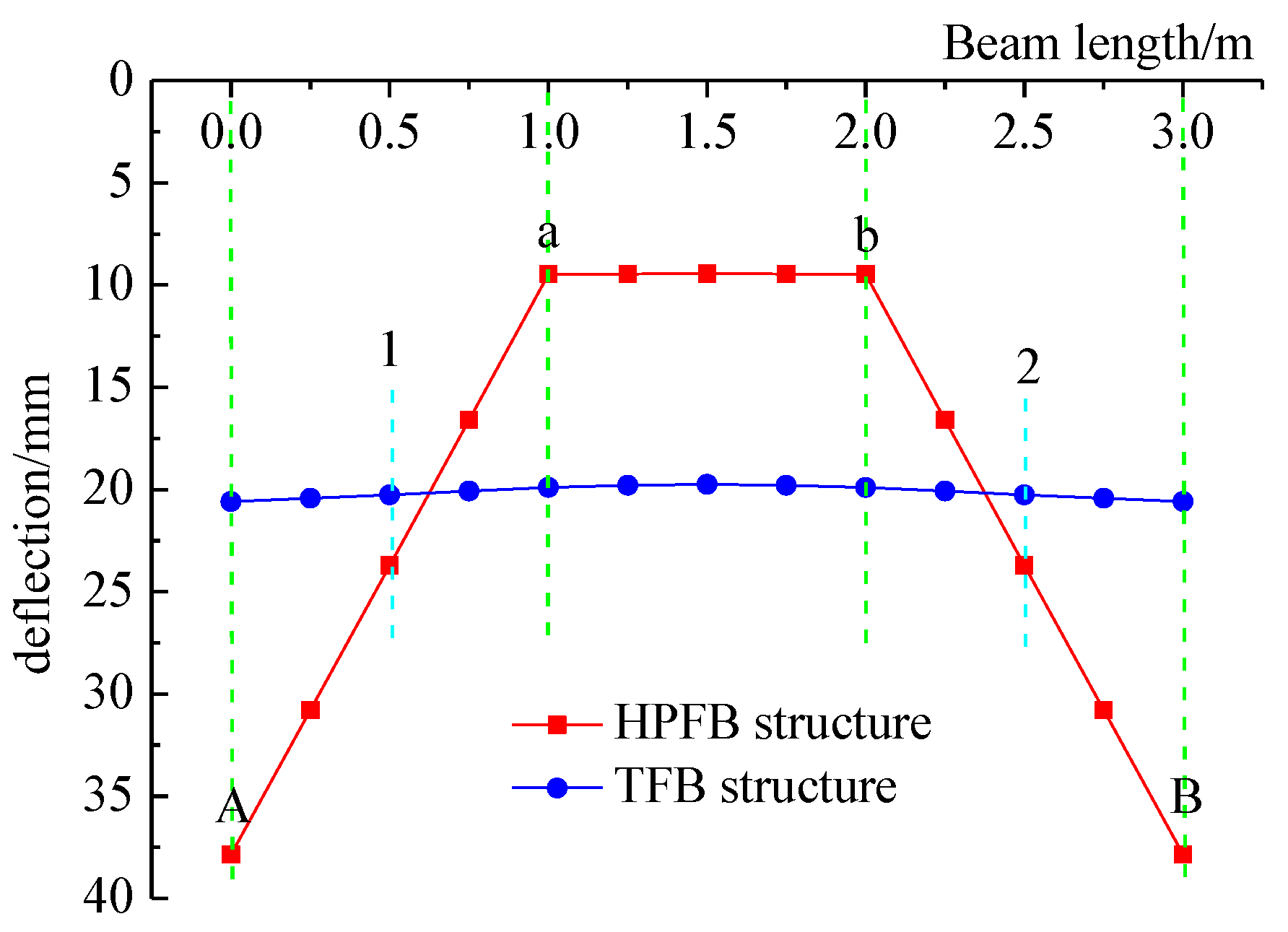

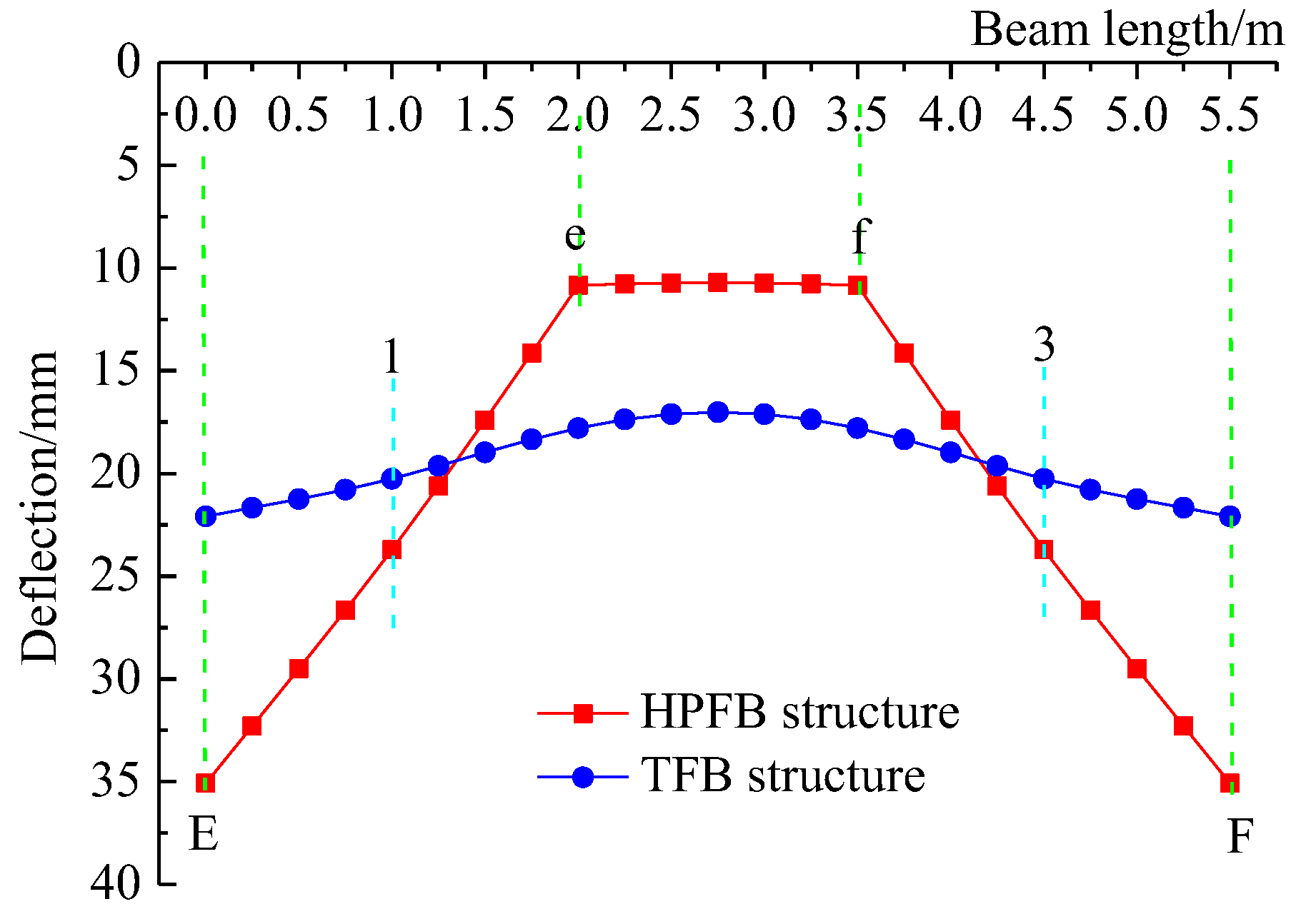

3.2.2. Comparative Analysis of Deflection Curves

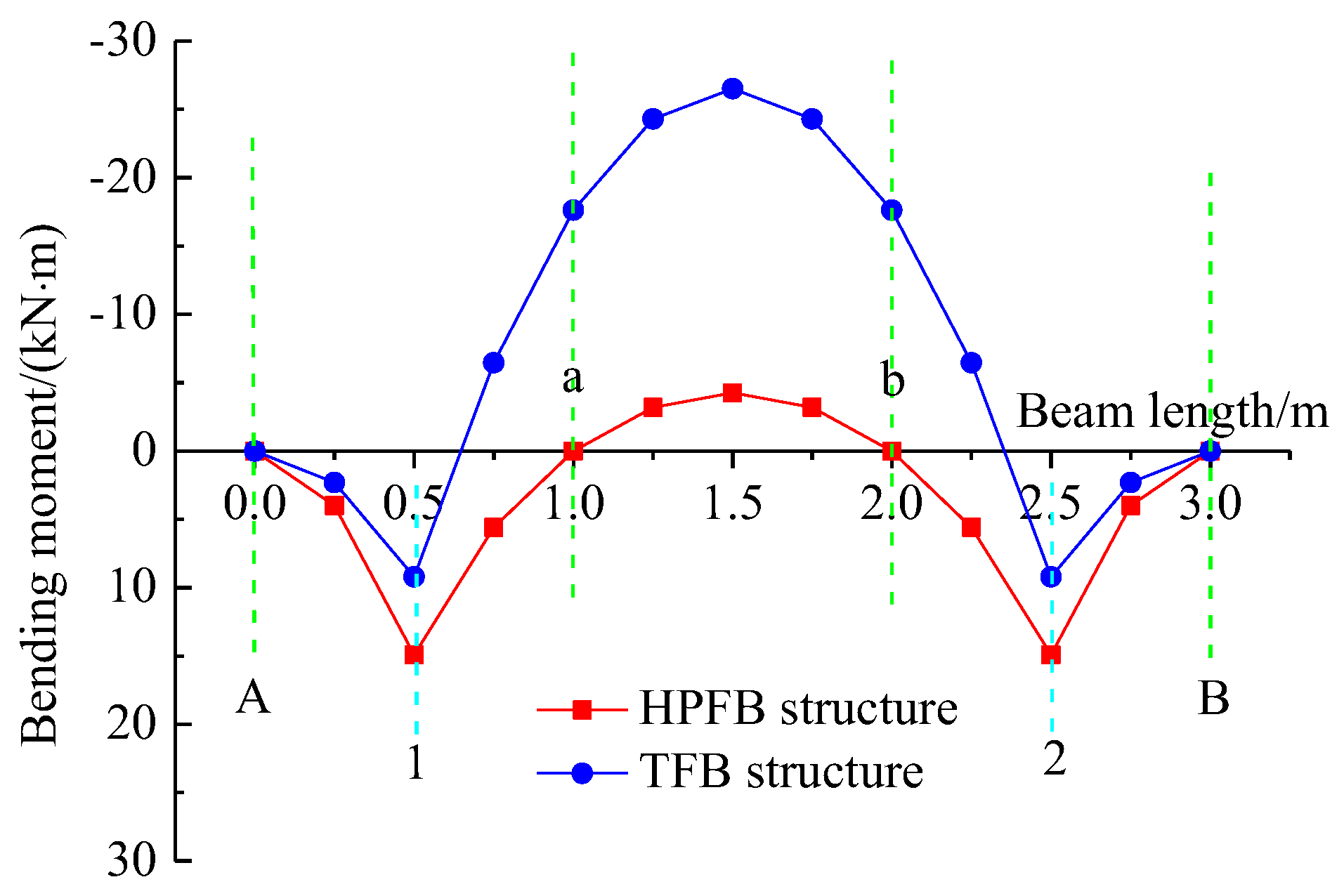

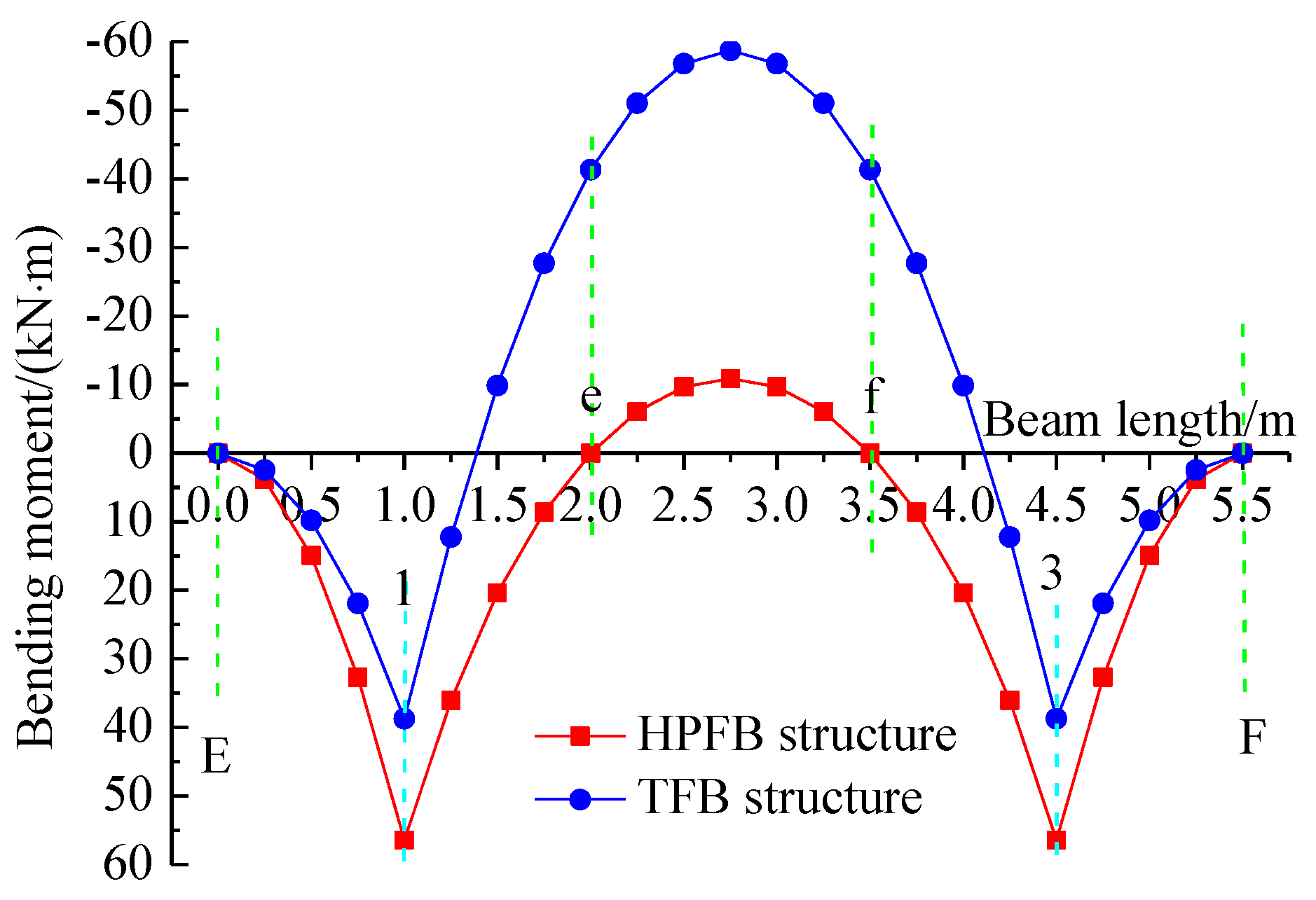

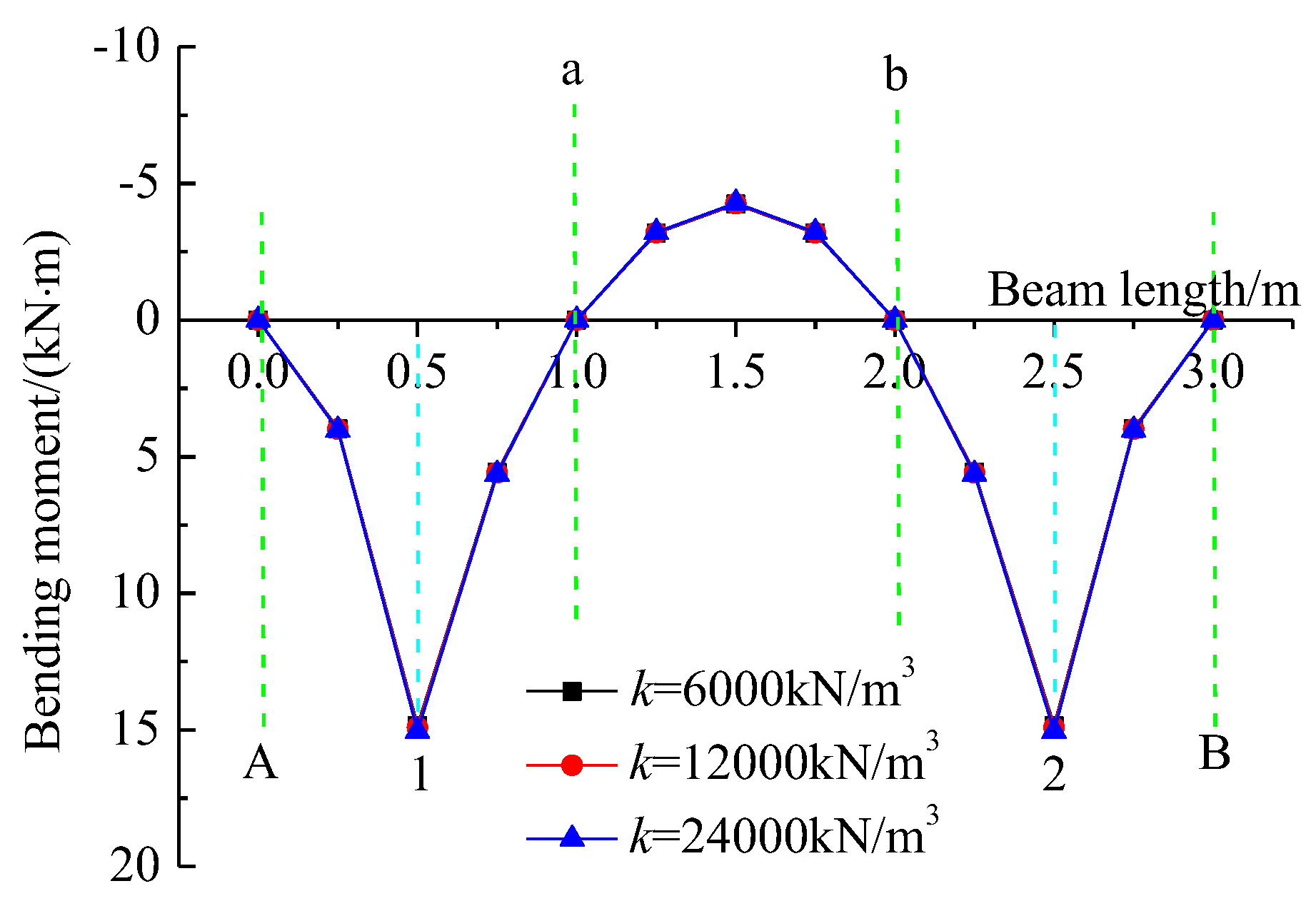

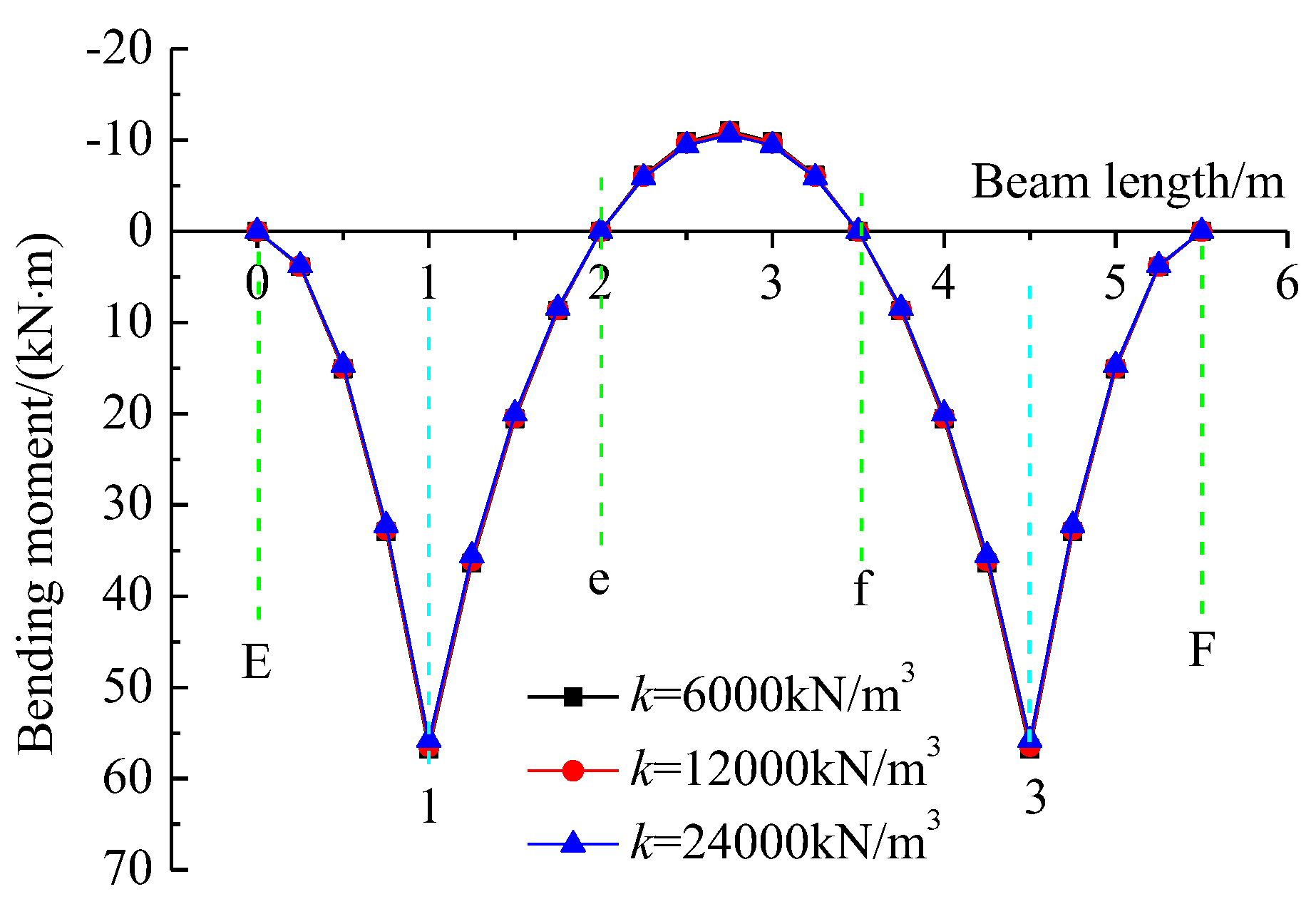

3.2.3. Comparative Analysis of Bending Moment Curves

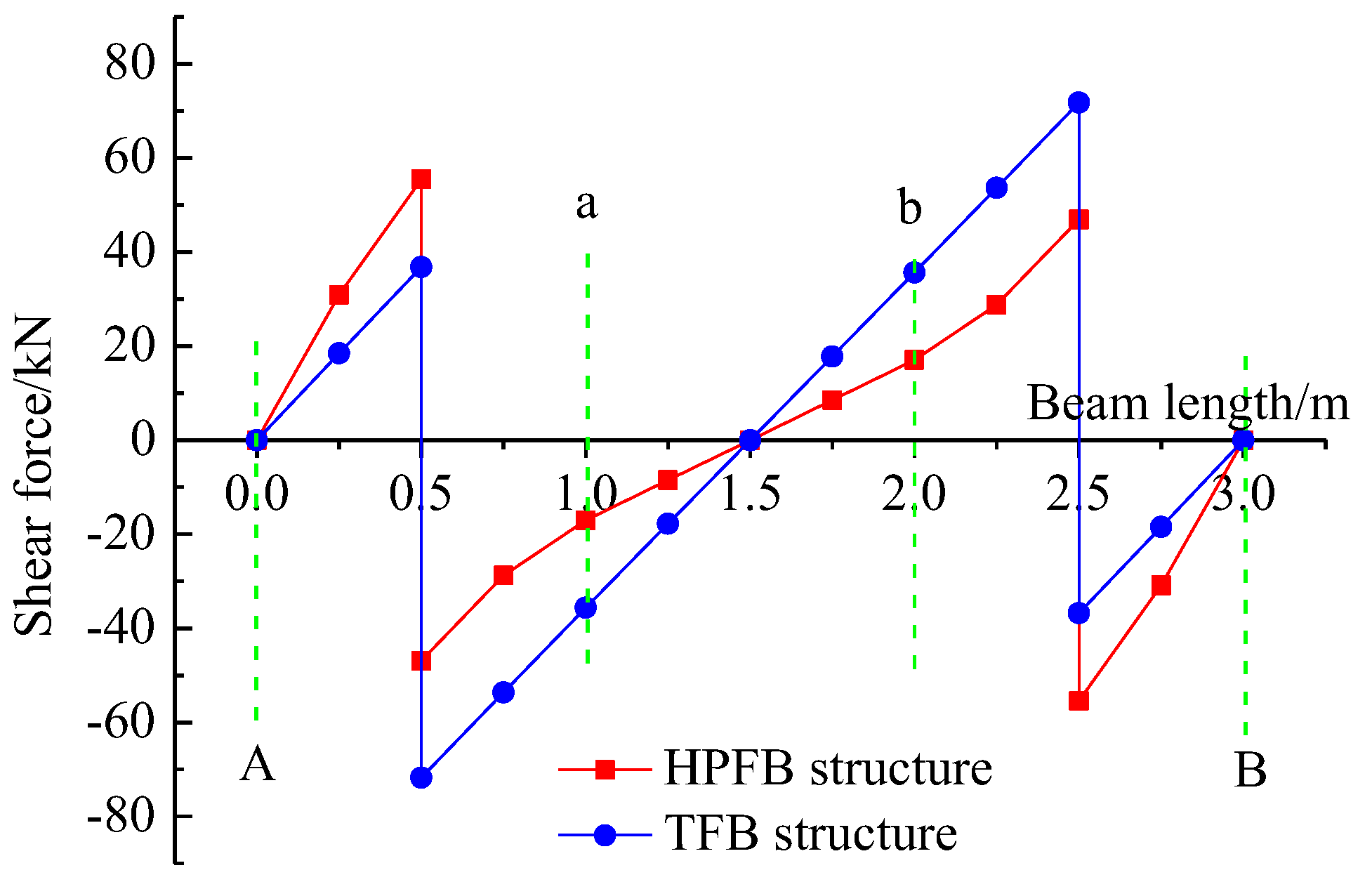

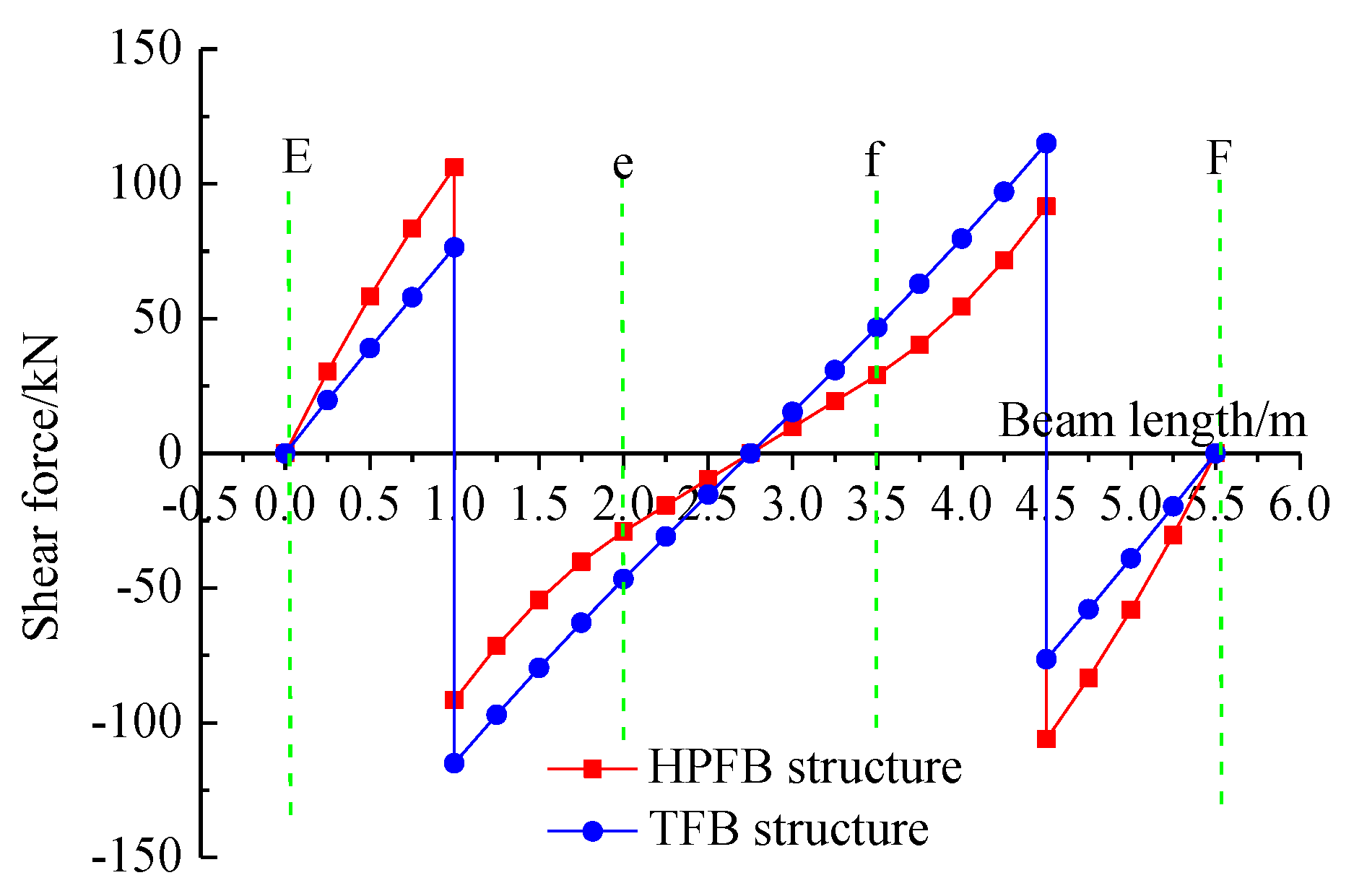

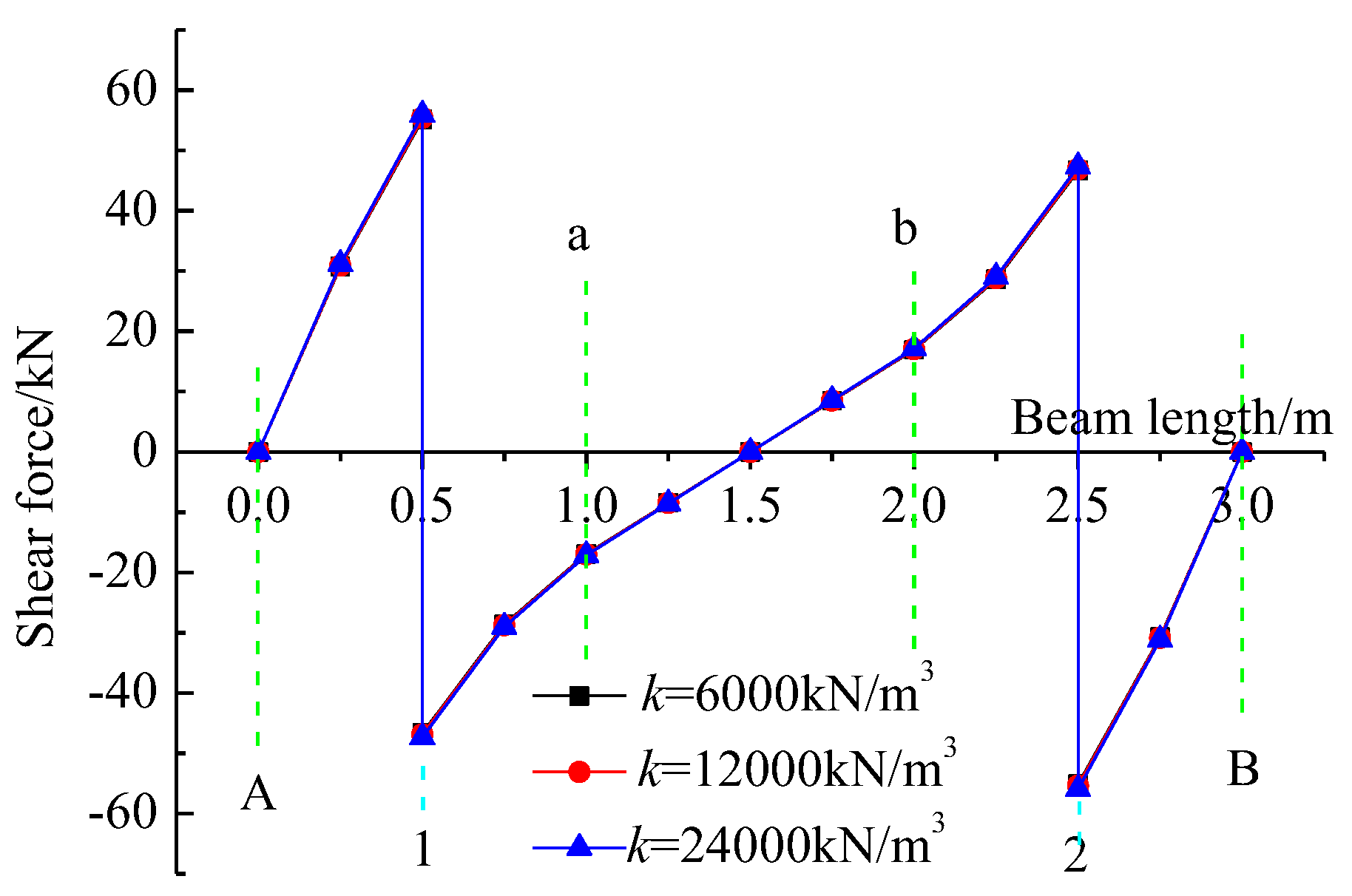

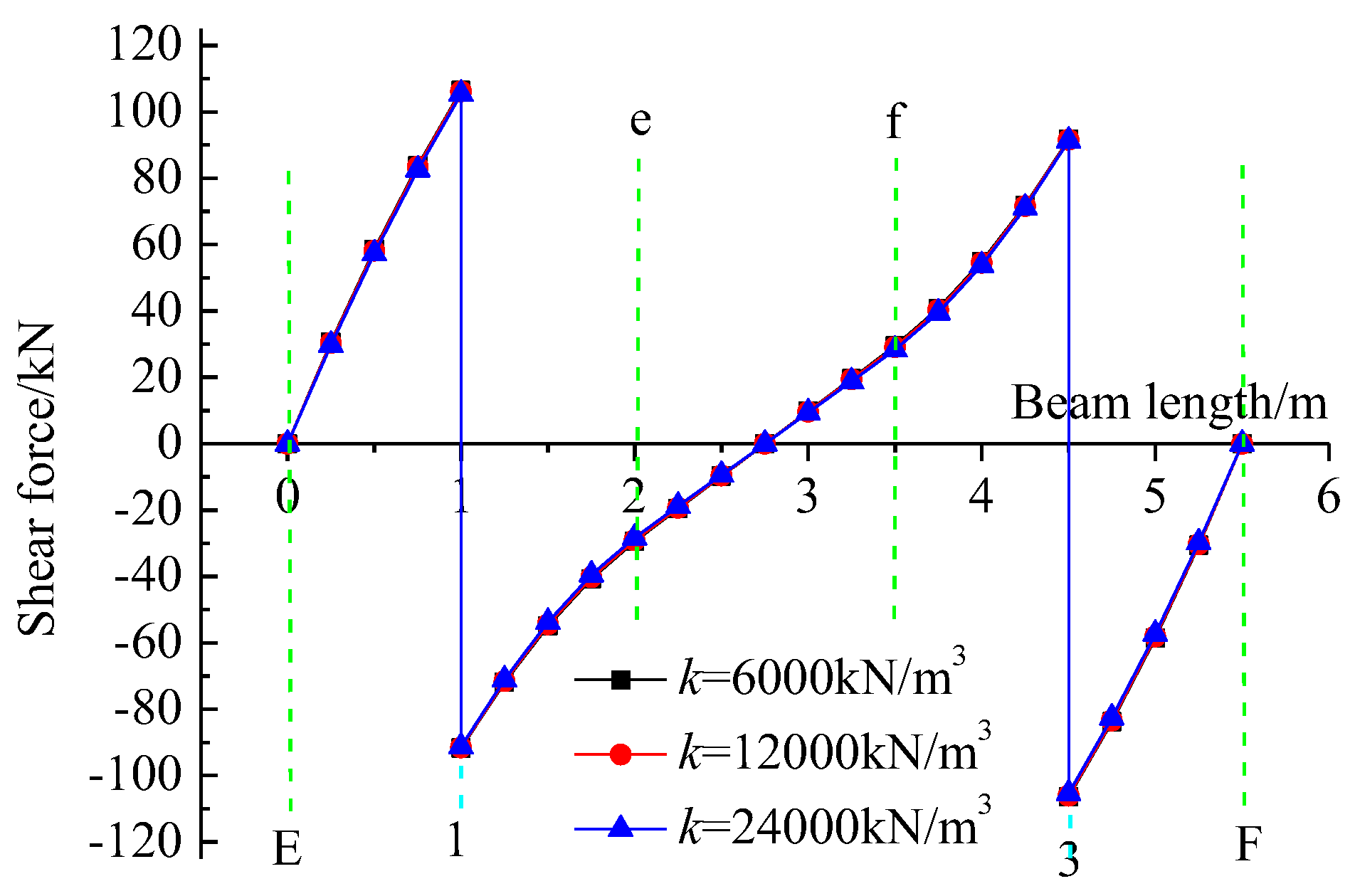

3.2.4. Comparative Analysis of Shear Force Curves

3.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Subgrade Reaction Coefficient on the Mechanical Response of HPFB Structures

3.3.1. Load Distribution and Determination of Beam-End Shear Forces

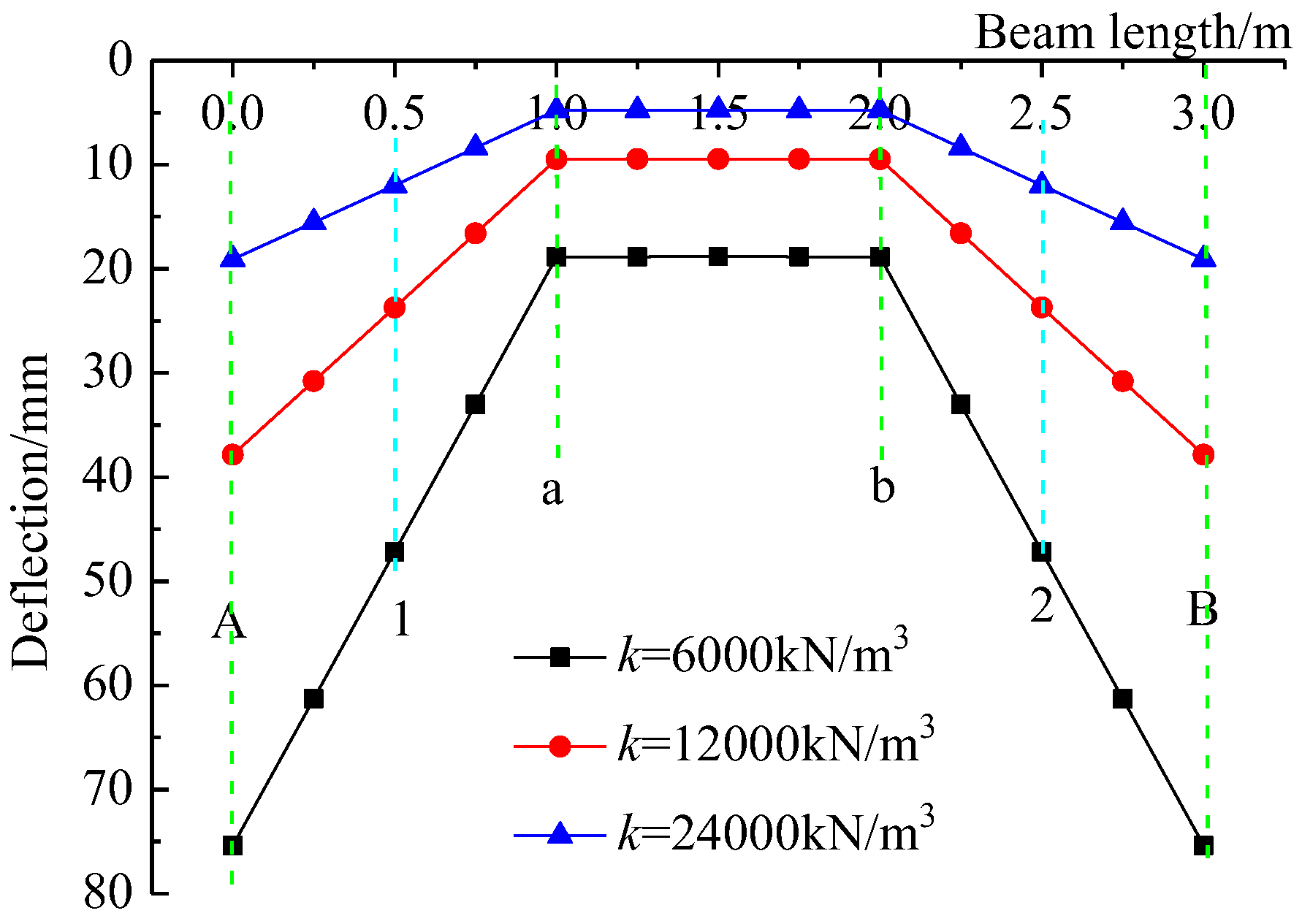

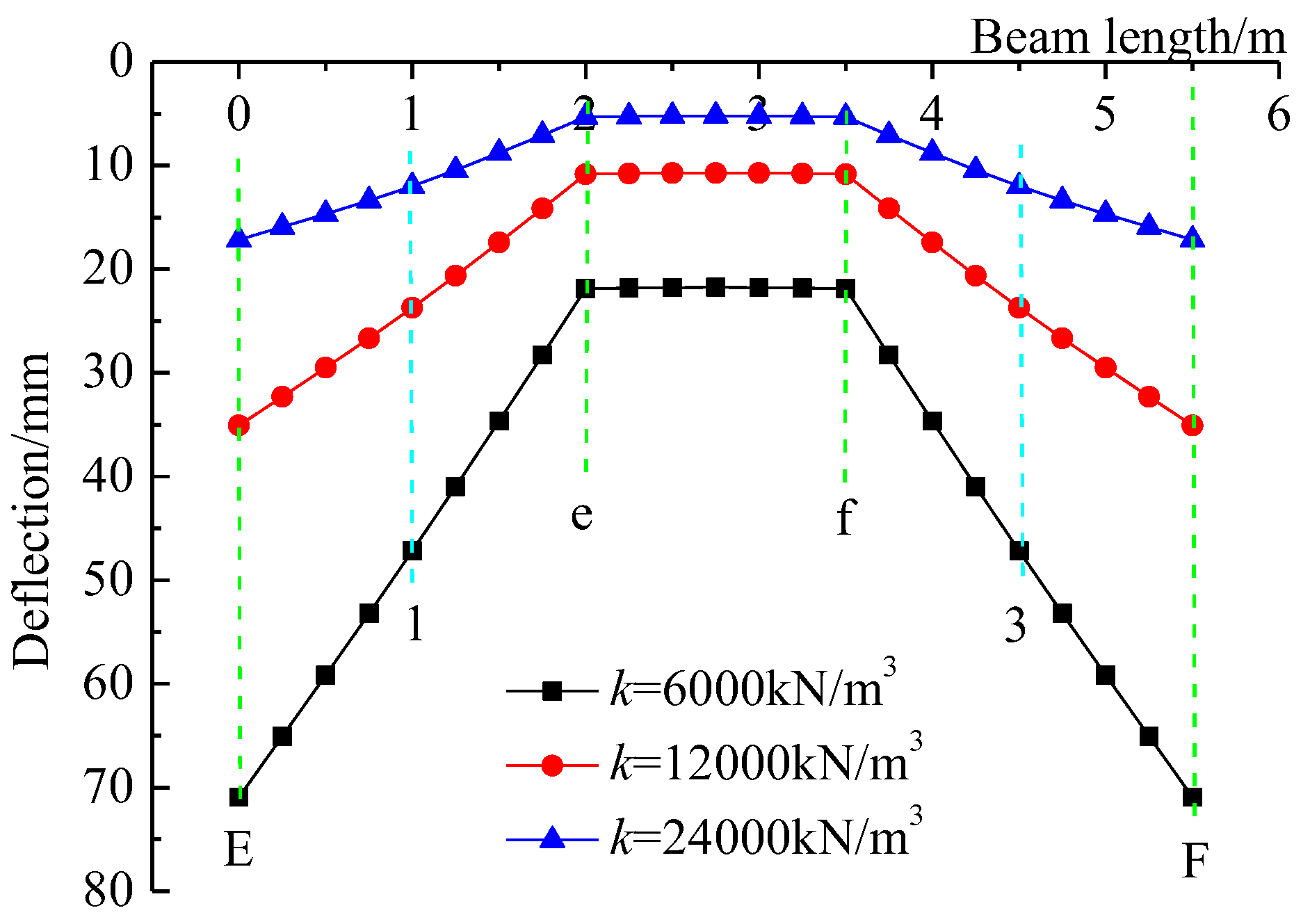

3.3.2. Sensitivity Analysis of Deflection to the Subgrade Reaction Coefficient

3.3.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Bending Moment to the Subgrade Reaction Coefficient

3.3.4. Sensitivity Analysis of Shear Force to the Subgrade Reaction Coefficient

3.4. Comparison with the Results Reported by Zhang et al. [27]

4. Conclusions

Data availability

Declaration of Competing Interest

Acknowledgments

References

- Zhang, H.; Lu, Y.; Cheng, Q. Numerical simulation of reinforcement for rock slope with rock bolt (anchor cable) frame beam. J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev. (Engl. Ed.) 2008, 3, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xi, H.; Zou, L.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, C. Recent advances in high slope reinforcement in China: Case studies. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2016, 8, 775–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.P.; Zhao, L.H.; Li, L. Limit-equilibrium analysis on stability of a reinforced slope with a grid beam anchored by cables. Int. J. Geomech. 2017, 17, 06017013. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Shi, K.Y.; Wu, X.P.; Dai, S.L. Coupled calculation model for anchoring force loss in a slope reinforced by a frame beam and anchor cables. Eng. Geol. 2019, 260, 105245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, G.; et al. Experimental and numerical evaluation of creep and coupling mechanism with lattice structure of the deposits coarse-grained soils in reservoir area. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2025, 29, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Yang, S.; Deng, B.; et al. A New Technique of Lattice Beam Construction with Pre-Anchoring for Strengthening Cut Slope: A Numerical Analysis of Temporary Stability during Excavation. Buildings 2022, 12, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Pei, X.; Wang, S.; Huang, R.; Zhang, X. Centrifuge model testing of loess landslides induced by excavation in Northwest China. Int. J. Geomech. 2020, 20, 04020022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gu, D.; Zhang, W. Influence of excavation schemes on slope stability: A DEM study. J. Mt. Sci. 2020, 17, 1509–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, Y.M.; Zhang, K.B.; et al. Field investigation and numerical study of a siltstone slope instability induced by excavation and rainfall. Landslides 2020, 17, 1485–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yubonchit, S.; Chinkulkijniwat, A.; Horpibulsuk, S.; et al. Influence factors involving rainfall-induced shallow slope failure: Numerical study. Int. J. Geomech. 2017, 17, 04016158. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L.M.; Gofar, N.; Rahardjo, H. A simple model for preliminary evaluation of rainfall-induced slope instability. Eng. Geol. 2009, 108, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, A.; Rahardjo, H.; Leong, E.C. Effect of antecedent rainfall patterns on rainfall-induced slope failure. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2011, 137, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Zhou, C.; Jiang, N.; et al. Stability analysis for high-steep slope subjected to repeated blasting vibration. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yan, C.; Zhao, X.; et al. Monitoring of train-induced vibrations on rock slopes. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2017, 13, 1550147716687557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhu, M.; Gobin, R. Seepage-induced slope failures on sandbars in Grand Canyon. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 1995, 121, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Z.; et al. Multiscale modelling of the seepage-induced failure of a soft rock slope. Acta Geotech. 2022, 17, 4717–4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, Z.; Ren, J.; et al. Mechanism of slope failure in loess terrains during spring thawing. J. Mt. Sci. 2018, 15, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paranunzio, R.; Laio, F.; Nigrelli, G.; et al. A method to reveal climatic variables triggering slope failures at high elevation. Nat. Hazards 2015, 76, 1039–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, A.; Hatakeyama, O. Characteristics of slope surfaces deformed by frost heaving. In Transportation Soil Engineering in Cold Regions, Volume 1: Proceedings of TRANSOILCOLD 2019; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, M.; Dou, G.; Yang, J.; Wei, S. Field Test and Numerical Study of Three Types of Frame Beams Subjected to a 600 kN Anchoring Force. Buildings 2024, 14, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.; Yang, J.; Wei, S. Calculation of precast prestressed beam with variable cross-sections on Pasternak foundation under anchoring force. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 28, 3941–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Cao, Y.; Wei, S.; Wei, P.; Huo, H.; Cai, J.; Li, Y. Analysis of reinforcement effect of different anchoring forces on slope stabilised by precast anchorage cable frame beams. Structures 2024, 69, 107476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, Q.; Li, F.; Zhang, S. Case study of field application of precast anchoring frame beam structure in slope supporting projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148, 05022008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, X. Stability Analysis of Red Clay Slope of Jiang-yu Expressway in Guizhou Province and Support of Fabricated Frame Beam. Master’s Thesis, Changsha University of Science & Technology, Changsha, China, 2019. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q. Study on Node Mechanical Properties and Shear Behavior of Hinged Precast Anchoring Frame Beam Structure. Master’s Thesis, Changsha University of Science & Technology, Changsha, China, 2022. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- DB43/T 2938-2024;Technical specification for the anchoring of hinged assembled frame beam structure; Administration for Market Regulation of Hunan Province: Changsha, China, 2024. (in Chinese)

- Zhang, J. , Zhou,S., Zhang,S., Li, F. Stress-induced deformation characteristics of a hinged precast anchor frame beam. J Changsha Univ Sci Tech 2025, 22, 1–14. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.B.; Zhu, Y.P.; Ye, S.H.; M, X.R. Internal force analysis and field test of lattice beam based on Winkler theory for elastic foundation beam. Math. Probl. Eng. 2019, 2019, 5130654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Yang, S.; Deng, B.; Sun, B.; Liu, T. A Comparison of Load Distribution Methods at the Node and Internal Force Analysis of the Lattice Beam Based on the Winkler Foundation Model. Buildings 2023, 13, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusama, T. ANALYSIS OF GRID WORKS AND ORTHOTROPIC PLATES ON WINKLER-TYPE FOUNDATIONS Contribution to Design of Grid Foundation and Mat[J]. Trans. Jpn. Soc. Civ. Eng. 1968, 152, 26–33. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Y.P. Calculation of internal forces of framed flexible supporting structure with prestressed anchors based on torsional effects among beams and columns[J]. J. Lanzhou Univ. Technol. 2009, 35, 116–121. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Selvadurai, A.P.S. Elastic Analysis of Soil-Foundation Interaction; Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Dinev, D. Analytical solution of beam on elastic foundation by singularity functions. Eng. Mech. 2012, 19, 381–392. [Google Scholar]

- Papusha, A.N. Beam Theory for Subsea Pipelines: Analysis and Practical Applications; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, J.E. Foundation Analysis and Design, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

| Loads | HPFB Structure | TFB Structure |

| F1x/kN | 102.331 | 108.557 |

| F1y/kN | 197.699 | 191.443 |

| Fa/kN | 17.0278 | —— |

| Fe/kN | 29.0528 | —— |

| HPFB Structure | TFB Structure | ||||||

| w1x/mm | w1y/mm | waAa/mm | waab/mm | weEe/mm | weef/mm | w1x/mm | w1y/mm |

| 23.7151 | 23.7151 | 9.4738 | 9.4739 | 10.8409 | 10.8409 | 20.2595 | 20.2595 |

| Loads | k=6000kN/m3 | k=12000kN/m3 | k=24000kN/m3 |

| F1x/kN | 101.833 | 102.331 | 103.305 |

| F1y/kN | 198.167 | 197.669 | 196.695 |

| Fa/kN | 16.9585 | 17.0278 | 17.1622 |

| Fe/kN | 29.4237 | 29.0528 | 28.3292 |

| Response Parameter | This study | Zhang et al. |

| Ratio of Maximum Negative Bending Moments | 16.0%-18.5% | 350% |

| Ratio of Maximum Positive Bending Moments | 146%-162% | 78.3% |

| Ratio of Maximum Shear Forces | 62.4%-77.2% | 114.3% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).