Submitted:

23 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Urban Justice as a Concept of Distribution

3. Methods

- Mapping the Selected Phenomenon: The researcher begins by defining the phenomenon of interest and its boundaries. This includes clarifying why the phenomenon is theoretically significant and identifying the main domains or scholarly fields relevant to it.

- Extensive Reading and Categorization of the Literature: An iterative, open-ended review of diverse sources—academic articles, books, policy documents, and theoretical texts—is conducted. The goal is not merely to summarize prior research but to identify emerging patterns, recurrent themes, and key conceptual elements.

- Identifying and Naming Concepts: From the literature, the researcher extracts core concepts that explain, structure, or give meaning to the phenomenon. Concepts are selected for their analytical relevance, theoretical richness, and explanatory potential.

- Deconstructing and Categorizing the Concepts: Each concept is analyzed in depth. The researcher deconstructs its meanings, assumptions, uses, and variations across different academic contexts. Concepts are then grouped into categories or thematic clusters.

- Integrating and Synthesizing the Concepts Into a Coherent Framework: The relationships among concepts are mapped—hierarchical, causal, overlapping, or complementary. Through synthesis, the framework begins to take shape as an interconnected system of meanings.

- Validating the Conceptual Framework: The emerging framework is compared with the literature for coherence, comprehensiveness, and internal logic. Validation includes checking whether the framework effectively explains the phenomenon and whether it aligns with or contributes to existing theoretical debates.

- Rethinking, Refining, and Revising the Framework: The framework remains dynamic and is revised through further reading, reflection, and conceptual clarification. Jabareen emphasizes that conceptual frameworks are not static but evolve through continuous engagement with theory.

- Presenting the Framework: Finally, the framework is articulated visually and narratively, showing how the selected concepts interact to explain the phenomenon. The presentation highlights the logic of relationships and the theoretical contributions generated by the framework.

4. Results

4.1. Concepts of the Contributions of Spatial Planning or Zoning Parameters for Social Justice

| Parameters | Authors | Conclusion Regarding their Contribution to Social Justice |

|---|---|---|

| Density | [19] | “Restrictive density zoning produces higher housing prices in White areas and limits opportunities for people with modest incomes to leave segregated areas, a perspective [….] showing that this zoning increases housing prices” (p. 801) |

| [20] | “Zoning ordinances are used to deter the entry of minority residents into majority neighborhoods through density restrictions (exclusionary zoning) and locate manufacturing activity in minority neighborhoods (environmental racism)” (p.1) | |

| “Neighborhoods with more black residents were more likely to be zoned for higher density buildings, suggesting that volume restrictions were used as an early form of exclusionary zoning” (p.26) | ||

| [18] | “Suburban jurisdictions with more units zoned, or designated, for high-density development have greater increases in their multifamily housing stocks” and are disproportionately located in minority communities and are “lower in communities that are more predominantly White” (p, 446). | |

| Housing types | [21] | “Zoning exclusively for detached houses effectively excludes large numbers of non-White households, as well as many white ones, who rent” (p. 41) |

| [22] | “Zoning that privilege “single-family homes promote exclusion and […..] contributes to shortages of housing, thereby benefiting homeowners at the expense of renters and forcing many housing consumers to spend more on housing” (p.106) | |

| Minimum lot sizes | [52] | “Stringent minimum lot size restrictions significantly increase housing prices, primarily by shifting building characteristics, and intensify segregation by disproportionately attracting high-income white homeowners” (p. 26) |

| [53] | “High minimum lot sizes were used by white natives to restrict homes built for blacks and foreigners” (p. 8). | |

| [54] | “Larger plots have higher ownership costs such as higher land rent and property tax” making it unaffordable for low-income groups” (p. 471) | |

| Parking requirements | [23] | “Costs of parking provision are high, and these costs are passed on to renters” fostering unaffordability and hence exclusion to low-income populations” (p.19) |

| Building height | [20] | “Ordinance was to reduce the density of immigrant neighborhoods in the future via constraints on building height” (p.26) |

| Setbacks | [51] | “Higher minimum required set-backs […..] cause large declines in the share of homes that are affordable” (p. 266). |

| Land use distribution through parameters | ||

| Green Spaces | [31] | “The massive park allocation and construction results into “gentrifying neighboring communities and forcing marginalized people to move away from the new green spaces”(p. 11) |

| Commercial facilities | [37] | “Low-income households face higher food prices in large part as a result of a lack of supermarket availability in their neighborhoods” (p, 194) |

| Distribution through Parameters | Authors | Conclusion Regarding their Contribution to Social Justice |

|---|---|---|

| Green space | [29] | “White-majority census tracts, regardless of income level, have much better urban green space accessibility than minority- dominated census tracts” (p. 8) |

| [27] | “Accessibility to greenspaces was higher in neighborhoods with lower levels of deprivation and a lower proportion of ethnic minority residents.” (p.143) | |

| [57] | Neighborhoods with a higher concentration of African Americans, Asian and socioeconomically disadvantaged areas had significantly poorer access to green spaces (pp 237- 242) | |

| Public facilities | [32] | “The northern half of the city, which was the residence of the upper and middle classes, enjoyed a wide range of social and physical advantages over the southern half “ (p, 6549), |

| [33] | “Although many low-income households fall within the catchment areas of health facilities, there are still more low-income residents without access to health facilities than their higher income counterparts” (p.9) | |

| Road network | [38] | “Wealthier groups […….] have better access and provision of urban space for urban mobility adapted to their needs” (p.10) |

| Sidewalk | [39] | “Sidewalk unevenness and the number of natural or artificial obstructions are greater in neighborhoods that are predominantly African–American, […..] than in primarily white neighborhoods with a lower percentage of individuals living in poverty” (p.982) |

| Distribution through Parameters | Authors | Conclusion Regarding their Contribution to Social Justice |

|---|---|---|

| Green spaces | [28] | “Neighborhoods with higher socioeconomic status are more likely to have more Urban public green spaces (UPGSs) abundance” (p. 474) |

| [30] | “Urban green infrastructure is disproportionately more abundant in high-income relative to low-in- come and in White relative to Black-African, Colored and Indian’ census tracts” (p, 6) | |

| [62] | “Low-income ethnic areas have significantly less access to parks than high-income white areas” (p.88) | |

| Commercial facilities | [36] | “Predominantly White neighborhoods also have significantly more diverse food service activity than predominantly Black neighborhoods” (p. 84) |

| Signage | [63] | Restricts the visibility of minority signage, as seen in Chinese neighborhoods where “80 percent of signs must appear in English,” reflecting selective recognition of cultural and linguistic diversity (p.347). |

| Urban Amenity (Street trees) | [34] | Lower proportion of tree cover on public right-of-way in neighborhoods containing a higher proportion of African-Americans, low-income residents, and renters compared to White dominated areas (pp 2663–2664) |

| Street furniture | [64] | “Esthetic/social features were consistently worse in low-income and high racial/ethnic minority neighborhoods as compared to high-income or mostly White neighborhoods” (p. 215) |

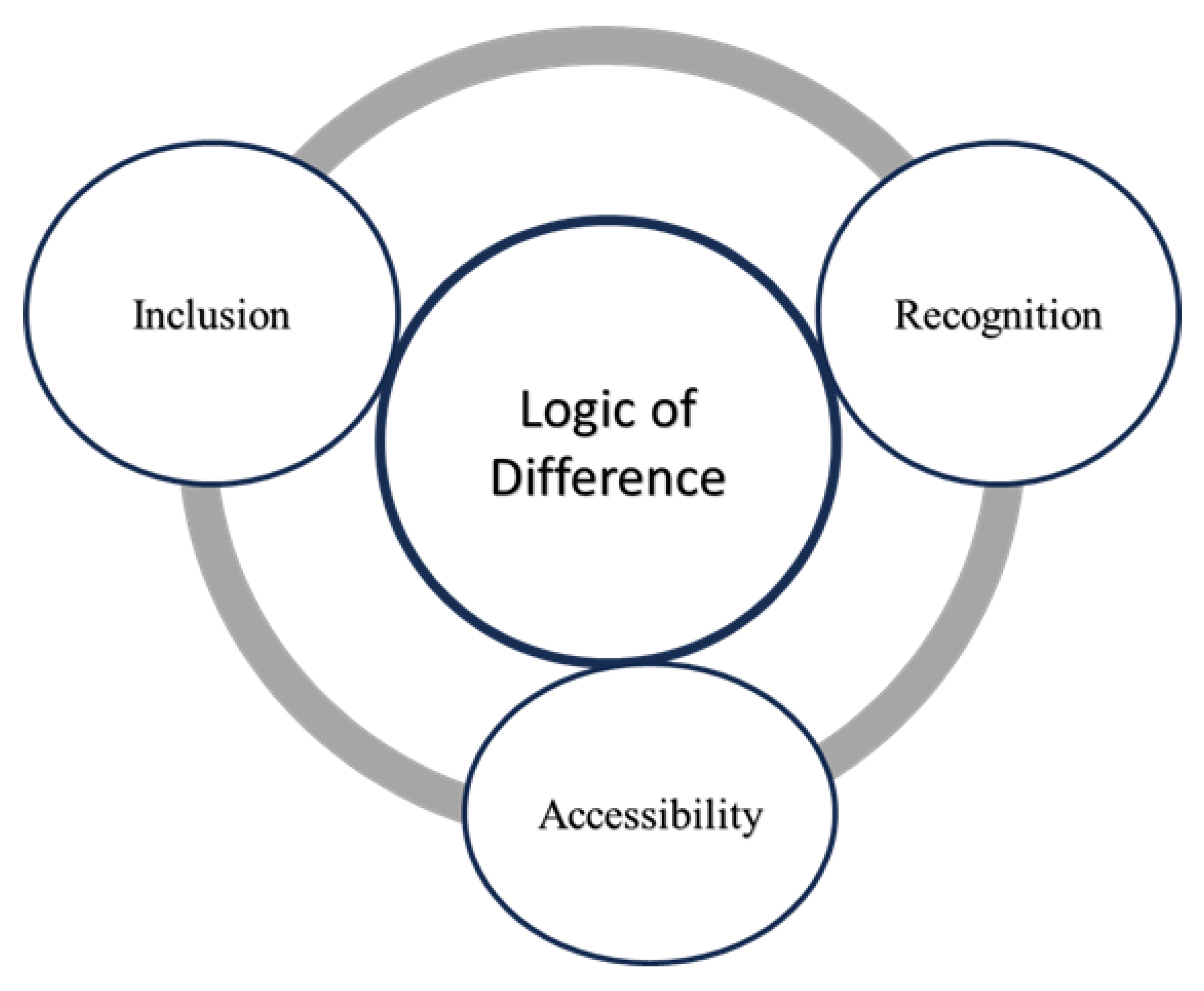

5. Conceptualization of the Role of Planning and Zoning Parameters in Promoting Social Justice

6. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Espitia, C. Urban Planning for Social Justice in Latin America; Routledge: London, 2023; ISBN 978-1-003-38081-8. [Google Scholar]

- Fainstein The Just City; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, 2010; ISBN 978-0-8014-4655-9.

- Fainstein, S. Resilience and Justice: Planning for New York City. The Resilience Machine; Routledge. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Social Justice and the City; The University of Georgia Press: Athens & London, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Marcuse, P.; Connolly, J.; Novy, J.; Olivo, I.; Potter, C.; Steil, J. Searching for the Just City: Debates in Urban Theory and Practice; 2009; ISBN 978-0-203-87883-5.

- Mitchell, D. Social Justice and the City and the Problem of Status Quo Theory. Scott. Geogr. J. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni, S. The Just City. Three Background Issues: Institutional Justice and Spatial Justice, Social Justice and Distributive Justice, Concept of Justice and Conceptions of Justice. Plan. Theory 2020, 19, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uitermark, J.; Nicholls, W. Planning for Social Justice: Strategies, Dilemmas, Tradeoffs. Plan. THEORY 2017, 16, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alterman, R. Planning Laws, Development Controls, and Social Equity: Lessons for Developing Countries. Law Justice Dev. Ser. 2013, 329–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M.K. Planning Standards and Spatial (in)Justice. Plan. Theory Pract. 2022, 23, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.; Hutson, M.; Mujahid, M. How Planning and Zoning Contribute to Inequitable Development, Neighborhood Health, and Environmental Injustice. Environ. Justice 2008, 1, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunda, J.G.; Jiao, J. Zoning Changes and Social Diversity in New York City, 1990–2015. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2019, 12, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J. Q The Politics of Regulation; (Ed.).; Basic Books: New York, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff, P.; Davidoff, L. Opening the Suburbs: Towards Inclusionary Land Use Controls. Syracuse Law Rev. 1971, 22, 509–536. [Google Scholar]

- Downs, A. Opening up the Suburbs: An Urban Strategy for America; 2. pr.; Yale Univ. Pr: New Haven, 1975; ISBN 978-0-300-01455-6. [Google Scholar]

- W. A. Fischel The Homevoter Hypothesis; Harvard University Press: Cambridge MA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, Jonathan Zoned Out: Regulation, Markets, and Choices in Transportation and Metropolitan Land-Use; Resources for the Future: Washington, DC, 2005.

- Chakraborty, A.; Knaap, G.-J.; Nguyen, D. ; Jung Ho Shin The Effects of High-Density Zoning on Multifamily Housing Construction in the Suburbs of Six US Metropolitan Areas. Urban Stud. 2010, 47, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, J.; Massey, D.S. The Effect of Density Zoning on Racial Segregation in U.S. Urban Areas. Urban Aff. Rev. 2009, 44, 779–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shertzer, A.; Twinam, T.; Walsh, R.P. Race, Ethnicity, and Discriminatory Zoning. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2016, 8, 217–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furth, S.; Webster, M. Single-Family Zoning and Race: Evidence From the Twin Cities. Hous. Policy Debate 2023, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manville, M.; Monkkonen, P.; Lens, M. It’s Time to End Single-Family Zoning. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 2020, 86, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbe, C.J.; Pierce, G. Hidden Costs and Deadweight Losses: Bundled Parking and Residential Rents in the Metropolitan United States. Hous. Policy Debate 2016, 27, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z. Residential Street Parking and Car Ownership. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 2013, 79, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manville, M. Parking Requirements and Housing Development. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 2013, 79, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, S.; Madar, J.; Been, V. Minimum Parking Requirements and Housing Affordability in New York City. Hous. Policy Debate 2010, 21, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, M.; Roberts, H.E.; McEachan, R.R.C.; Dallimer, M. Contrasting Distributions of Urban Green Infrastructure across Social and Ethno-Racial Groups. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 175, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, Y. Neighborhood Socioeconomic Disadvantage and Urban Public Green Spaces Availability: A Localized Modeling Approach to Inform Land Use Policy. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Kwan, M.-P.; Kan, Z. Analysis of Urban Green Space Accessibility and Distribution Inequity in the City of Chicago. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 59, 127029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z.S.; Shackleton, C.M.; Van Staden, F.; Selomane, O.; Masterson, V.A. Green Apartheid: Urban Green Infrastructure Remains Unequally Distributed across Income and Race Geographies in South Africa. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 203, 103889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; G. Rowe, P. Green Space Progress or Paradox: Identifying Green Space Associated Gentrification in Beijing. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 219, 104321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, A.; Farhadi, E.; Hussaini, F.; Pourahmad, A.; Seraj Akbari, N. Analysis of Spatial (in)Equality of Urban Facilities in Tehran: An Integration of Spatial Accessibility. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 6527–6555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayaud, J.R.; Tran, M.; Nuttall, R. An Urban Data Framework for Assessing Equity in Cities: Comparing Accessibility to Healthcare Facilities in Cascadia. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2019, 78, 101401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, S.M.; Chakraborty, J. Street Trees and Equity: Evaluating the Spatial Distribution of an Urban Amenity. Environ. Plan. Econ. Space 2009, 41, 2651–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, C.M.; Conway, T.L.; Cain, K.L.; Gavand, K.A.; Saelens, B.E.; Frank, L.D.; Geremia, C.M.; Glanz, K.; King, A.C.; Sallis, J.F. Disparities in Pedestrian Streetscape Environments by Income and Race/Ethnicity. SSM - Popul. Health 2016, 2, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, R.; Schuetz, J. Bodegas or Bagel Shops? Neighborhood Differences in Retail and Household Services. Econ. Dev. Q. 2012, 26, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, L.M.; Slater, S.; Mirtcheva, D.; Bao, Y.; Chaloupka, F.J. Food Store Availability and Neighborhood Characteristics in the United States. Prev. Med. 2007, 44, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, L.A.; Oviedo, D.; Arellana, J.; Cantillo-García, V. Buying a Car and the Street: Transport Justice and Urban Space Distribution. Transp. Res. Part Transp. Environ. 2021, 95, 102860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.M.; Schootman, M.; Baker, E.A.; Barnidge, E.K.; Lemes, A. The Association of Sidewalk Walkability and Physical Disorder with Area-Level Race and Poverty. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 978–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornell, D. , Rosenfeld, M.; Carlson, D.G. (Eds. ) Deconstruction and the Possibility of Justice; Psychology Press. 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, J. Of Grammatology; Translated by Gayatri Chakravorty Spirat, Ed.; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore and London, 1997.

- Gormley, S. Deliberative Theory and Deconstruction. In Deliberative Theory and Deconstruction; Edinburgh University Press. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rasche, A. Organizing Derrida Organizing: Deconstruction and Organization Theory. In In Philosophy and organization theory; Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2011; pp. 254–255.

- Rawls, J. A Theory of Justice (Revised Edition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Nozick Anarchy, State, and Utopia; 1974; Vol. 5038;

- Pogge, T Realizing Rawls.; Cornell University Press, 1989.

- Sen, A The Idea of Justice; Penguin Books Ltd.: New Delhi, 2009.

- Valentini, L. A Paradigm Shift in Theorizing about Justice? A Critique of Sen. Econ. Philos. 2011, 27, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttiroiko, A.-V.; De Jong, M. Conceptualizing Exclusion and Inclusion. In The Inclusive City; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-61364-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J. Re-Orienting Geographies of Urban Diversity and Coexistence: Analyzing Inclusion and Difference in Public Space. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2019, 43, 478–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihlanfeldt, K.R.; Moore, L.; Ihlanfeldt, K.R. Exclusionary Land-Use Regulations within Suburban Communities: A Review of the Evidence and Policy Prescriptions. Urban Stud. 2004, 41, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J. The Effects of Residential Zoning in U.S. Housing Markets. SSRN Electron. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Ward, B.A. The Causes and Consequences of Land Use Regulation: Evidence from Greater Boston. J. Urban Econ. 2009, 65, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusugga Kironde, J.M. The Regulatory Framework, Unplanned Development and Urban Poverty: Findings from Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. Land Use Policy 2006, 23, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, B.M.; Thompson, G.L.; Brown, J.R. Estimating Transit Accessibility with an Alternative Method: Evidence from Broward County, Florida. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2010, 2144, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páez, A.; Scott, D.M.; Morency, C. Measuring Accessibility: Positive and Normative Implementations of Various Accessibility Indicators. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 25, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D. Racial/Ethnic and Socioeconomic Disparities in Urban Green Space Accessibility: Where to Intervene? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 102, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H. The Politics of Recognition and Planning Practices in Diverse Neighbourhoods: Korean Chinese in Garibong-Dong, Seoul. Urban Stud. 2021, 58, 2863–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizenberg, E.; Jabareen, Y.; Arviv, T.; Arussy, D. Urban Space of Recognition: Design for Ethno-Cultural Diversity in the German Colony, Haifa. J. Urban Des. 2022, 27, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. Recognition or Redistribution? A Critical Reading of Iris Young’s Justice and the Politics of Difference *. J. Polit. Philos. 1995, 3, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, H.I.; Alkan Olsson, J. The Link Between Urban Green Space Planning Tools and Distributive, Procedural and Recognition Justice. In Human-Nature Interactions; Misiune, I., Depellegrin, D., Egarter Vigl, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; ISBN 978-3-031-01979-1. [Google Scholar]

- A. , R.; Flohr Access to Parks for Youth as an Environmental Justice Issue: Access Inequalities and Possible Solutions. buildings 2014, 4, 69–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaides, B.M.; Zarsadiaz, J. Design Assimilation in Suburbia: Asian Americans, Built Landscapes, and Suburban Advantage in Los Angeles’s San Gabriel Valley since 1970. J. Urban Hist. 2017, 43, 332–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, C.M.; Conway, T.L.; Cain, K.L.; Gavand, K.A.; Saelens, B.E.; Frank, L.D.; Geremia, C.M.; Glanz, K.; King, A.C.; Sallis, J.F. Disparities in Pedestrian Streetscape Environments by Income and Race/Ethnicity. SSM - Popul. Health 2016, 2, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laclau, E. On Populist Reason.; Verso. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jabareen, Y.; Eizenberg, E. Theorizing Urban Social Spaces and Their Interrelations: New Perspectives on Urban Sociology, Politics, and Planning. Plan. Theory 2021, 20, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, I.M. Justice and the Politics of Difference.; Princeton University Press.: New Jersey:, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lens, M.C.; Monkkonen, P. Do Strict Land Use Regulations Make Metropolitan Areas More Segregated by Income? J. Am. Plan. Assoc. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2016, 82, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynge, H.; Visagie, J.; Scheba, A.; Turok, I.; Everatt, D.; Abrahams, C. Developing Neighbourhood Typologies and Understanding Urban Inequality: A Data-Driven Approach. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2022, 9, 618–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiftachel, O. Planning and Social Control: Exploring the Dark Side. J. Plan. Lit. 1998, 12, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, B.; Ferm, J. Planning, Regulation and Space Standards in England: From “homes for Heroes” to “Slums of the Future.” Town Plan. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendall, R. Local Land Use Regulation and the Chain of Exclusion. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 2000, 66, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribot, J.C.; Peluso, N.L. A Theory of Access*. Rural Sociol. 2003, 68, 153–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, E. Writing the City Spatially 1. City 2003, 7, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, D. Making the Links between Accessibility, Social and Spatial Inequality, and Social Exclusion: A Framework for Cities in Latin America. Adv. Transp. Policy Plan. 2021, 8, 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincher, R.; Iveson, K.; Leitner, H.; Preston, V. Planning in the Multicultural City: Celebrating Diversity or Reinforcing Difference? Prog. Plan. 2014, 92, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. Rethinking Recognition; 2000; Vol. New left review.

- Yiftachel, O. Critical Theory and ‘Gray Space’: Mobilization of the Colonized. City 2009, 13, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).