1. Introduction

1.1. Background & Research Problem

Urban accessibility is a fundamental aspect of sustainable urban development, yet with the majority of cities, provision of equal mobility to all citizens remains elusive [

1]. High growth rates of urban populations, combined with aging infrastructure and outdated policies, have created massive differences in accessibility. With or without international standards such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of inclusive cities, real implementation of accessibility policies remains uneven [

2].

Urban green spaces are an integral part of contemporary urban planning, contributing to environmental sustainability, public health, and social cohesion. With cities expanding, there

’s a growing necessity for accessible, inclusive public space for individuals with disabilities. Over one billion individuals worldwide live with disabilities, and addressing diverse impairments—intellectual, neurological, physical, psychological, and sensory—is a priority in urban planning [

3].

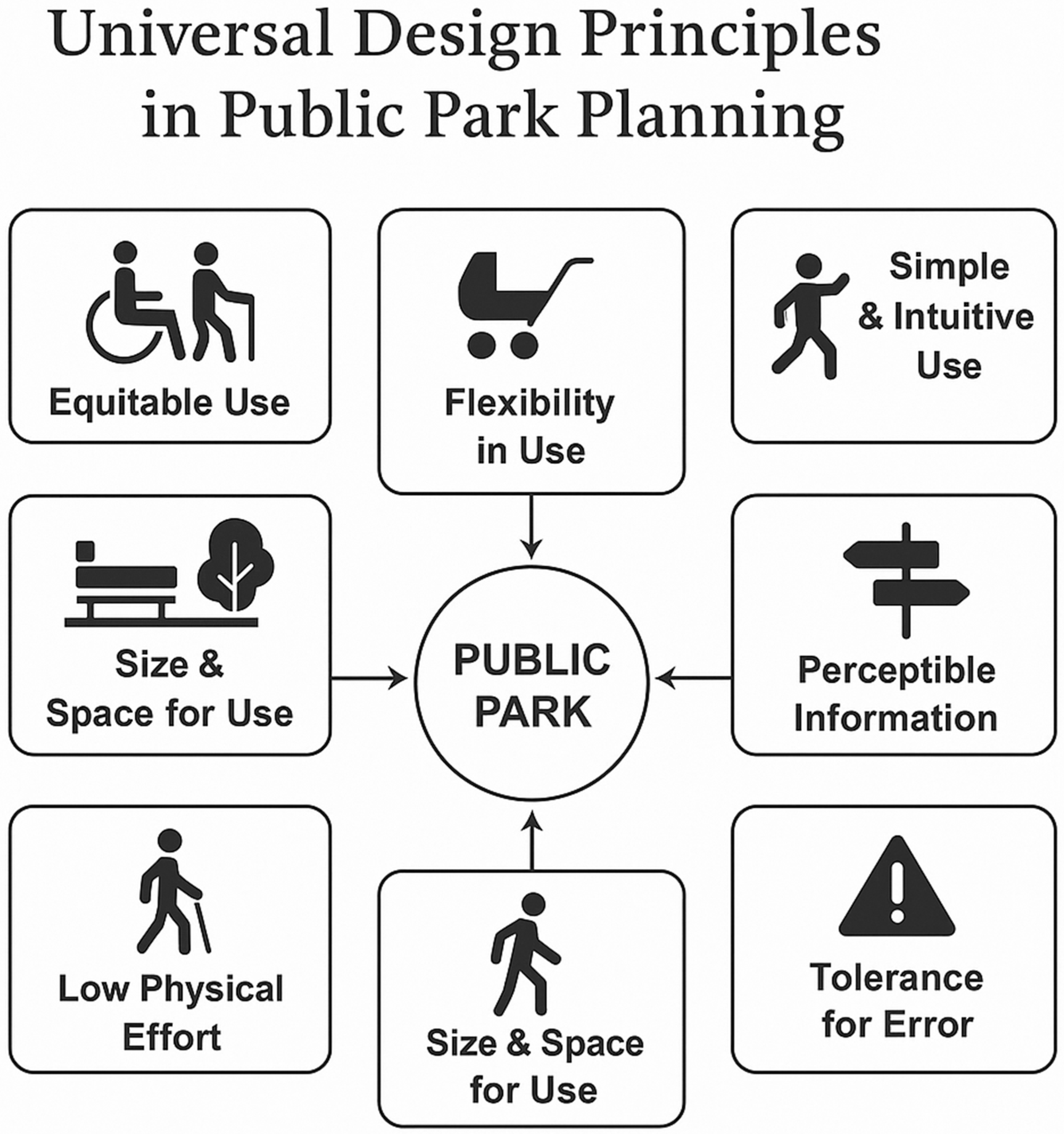

Universal Design (UD) is now a necessary approach to designing spaces for inclusivity. UD guidelines—Equitable Use, Flexibility in Use, Simple and Intuitive Use, Perceptible Information, Tolerance for Error, Low Physical Effort, and Size and Space for Approach and Use—above the minimum level of accessibility ensure urban spaces are accessible to various needs [

4,

5]. In parks, UD provides physical access but also aesthetic and psychological inclusion. [

6]

1.2. Objectives & Research Questions

The aim of this study is to investigate the extent to which current urban design methods enable accessibility and identify the principal barriers to implementing them. The primary research questions guiding this study are:

How do contemporary urban planning policies address issues of accessibility?

What are the principal obstacles preventing cities from being completely accessible?

What is the role of new technologies and participatory planning in improving accessibility?

1.3. Significance of Study

By responding to these questions, this study contributes to the literature on urban inclusivity. Its findings will provide urban planners, policymakers, and designers with insight into effective accessibility strategies and inform future research on sustainable urban mobility.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study employs a mixed-methods approach, combining both qualitative and quantitative research methodologies. This allows for a comprehensive analysis of urban accessibility by integrating statistical data with real-world case studies [

7,

8].

A systematic literature review was conducted to establish a theoretical framework for evaluating accessibility of public space. Scholarly articles, policy documents, and global guidelines (e.g., ISO 21542, ADA Guidelines, and UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities) were analyzed to identify best practices and design parameters for universal public space. The review was focused on UD principles, accessibility standards, and the functional requirements of users with different disabilities [

9,

10,

11].

2.2. Data Collection Methods

Case Study Analysis: Selected cities with varying degrees of accessibility implementation were analyzed to identify best practices and challenges.

Policy Review: Existing accessibility policies were examined to assess their effectiveness and areas for improvement.

Observational research was conducted in Kaimakli Linear Park with a structured evaluation checklist based on a literature review. This checklist systematically assessed physical accessibility features, including:

Mobility infrastructure: Ramps, handrails, pathways, and curb cuts

Wayfinding and signage: Accessible symbols, tactile and Braille elements, and direction signs

Seating and resting areas: Ergonomic design, spacing, and wheelchair-accessible seating availability

Parking and transport links: Accessible parking bays, proximity to public transport

Recreational spaces: Accessible exercise machinery and play areas for all users

2.3. Data Analysis

Quantitative Data: Survey responses were analyzed using statistical methods to identify trends and correlations between accessibility policies and urban mobility outcomes [

8].

Qualitative Data: Thematic analysis was conducted on interview transcripts to uncover key themes related to accessibility challenges and proposed solutions [

8].

Observations were conducted at different times of day to accommodate various user interactions. Data were qualitatively analyzed to ascertain UD principles compliance, existing barriers, and potential areas of improvement [

5].

The information collected were analyzed thematically, with patterns and trends drawn on the basis of recurring accessibility problems. A comparative approach was employed, overlaying the observed features against established design guidelines to evaluate the park’s inclusivity. This analysis informed recommendations for enhancing the park’s accessibility and broader urban design policy.

By integrating theoretical frameworks and empirical research, this method gives a rigorous assessment of Universal Design in public parks, thus contributing to urban planning and inclusive design discourse.

2.4. Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights, certain limitations exist. The research focuses primarily on case studies from specific geographic locations, which may limit generalizability. The study does not conduct cost-benefit analysis of implementing accessibility improvements, which could be explored in future research. Common barriers to effective accessibility implementation include:

Infrastructure limitations: Many cities have legacy infrastructure that is difficult to retrofit for accessibility.

Financial constraints: Governments often prioritize other urban development projects over accessibility improvements.

Lack of stakeholder coordination: Accessibility planning requires collaboration among architects, urban planners, policymakers, and advocacy groups, yet coordination efforts are often fragmented.

3. Legal Framework and Technical Specifications

Universal Design (UD) principles serve as a guiding framework for evaluating spatial inclusion in public environments [

5]. When applied to urban parks, these principles inform decisions on path gradients, seating, signage, sensory cues, and spatial connectivity [

12].

Figure 1, presents a conceptual visualization of how Universal Design principles are operationalized in the planning of accessible public parks. These principles guide the integration of inclusive features such as tactile paving, ramp access, multi-height signage, and seating arrangements suitable for diverse users.

3.1. Theoretical Frameworks on Urban Accessibility

Urban accessibility is grounded in several theoretical perspectives, including universal design principles, social inclusion theory, and sustainable urbanism [

13]. Universal design promotes environments that accommodate all individuals, regardless of physical ability, while social inclusion theory emphasizes equal access to public spaces. The integration of these frameworks into urban planning ensures that accessibility is not an afterthought but a fundamental aspect of city design.

3.2. Existing Urban Accessibility Policies and Guidelines

Several international policies and guidelines shape urban accessibility standards, including [

14,

15,

16]:

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which mandates accessible public spaces in the U.S.

The European Accessibility Act, focusing on standardizing accessibility measures across the EU.

The UN Sustainable Development Goals (Goal 11: Sustainable Cities & Communities), advocating for inclusive urban environments.

Despite these policies, compliance and enforcement remain inconsistent, highlighting the need for stronger governmental oversight and community engagement. This research applies a qualitative approach, with the use of systematic review of literature and analysis of direct observation, to explore the implementation of Universal Design (UD) principles in Kaimakli Linear Park, Nicosia. The mixed-method approach enables comprehensive understanding of accessibility issues and opportunities in urban parks [

8].

In 2017, under Article 19 of the Legislation on the Regulation of Roads and Buildings, the Cyprus Council of Ministers promulgated the Regulations for Roads and Buildings [

17]. This legal framework, ratified by the House of Representatives, underwent significant amendments post-2018, notably the introduction of Regulation 61H and its successor, Regulation 61HA [

17]. Regulation 61HA specifically addresses Accessibility and Safety in use, mandating comprehensive guidelines for the planning and construction of roads and buildings [

18]. Its objective is to minimize accident and damage risks while ensuring universal accessibility, particularly for individuals with disabilities or mobility impairments, throughout their utilization and operational phases.

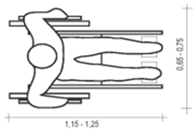

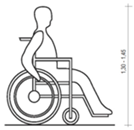

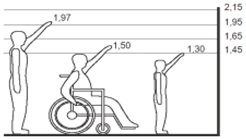

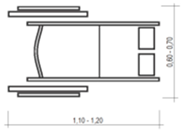

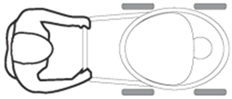

3.3. Basic Anthropometric Dimensions

In the context of accessibility and ergonomic design, certain anthropometric dimensions are crucial for catering to the needs of individuals with disabilities, including those with reduced mobility (e.g., wheelchair users) and individuals with visual challenges. The anthropometric parameters outlined in

Table 1 are specifically tailored to accommodate the requirements of individuals with disabilities, reduced mobility, and visual impairments, ensuring their accessibility and usability in various environments.

3.4. Technical Specifications for Universal Design

Universal design principles are at the heart of creating environments that are accessible, usable, and inclusive to all, regardless of their physical disabilities or abilities. Universal design principles involve designing environments for use by a wide user base, including individuals with disabilities, the elderly, as well as individuals with temporary impairment [

19]. In achieving universal design, technical specifications are essential to ensure that all aspects of the built environment, such as entrances and circulation, furniture and technology, are accessible and safe for everyone. Some of the key technical specifications include the utilization of adjustable spaces to allow easy movement, non-slip surfaces to provide safety, and clear visual and tactile cues for way-finding. Ramp grades, doorway openings, hallway widths, and the placement of fixtures and furniture must meet universal standards to provide barrier-free access for wheelchair users, people with vision disabilities, and others with mobility impairments [

17,

18]. The design should also consider the integration of assistive technologies and adaptable solutions that allow for change of use over time. Lastly, technical standards for universal design ensure that environments are flexible, sustainable, and fully accessible to all, facilitating independence and equal access.

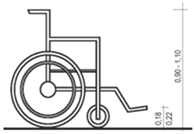

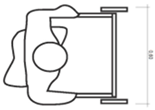

3.4.1. Wheelchair Users

Wheelchair accessibility is a significant consideration in the design and construction of public spaces to ensure equality of access and inclusivity for individuals with mobility disabilities. The physical environment must have sufficient provisions, from parking facilities and pathways to rest areas and toilets, to facilitate the autonomy and safety of wheelchair users [

17]. These encompass thoughtful elements such as appropriate gradients, traversable spaces, and the provision of accessible facilities on all levels of public areas. The implementation of these standards not only provides physical accessibility but also encourages social inclusion by enabling individuals with disabilities to participate fully in everyday activities. This chapter outlines the most significant design principles and technical specifications required for enabling wheelchair users in public areas.

Signage for wheelchair users: Signage in public spaces plays a critical role in wayfinding and accessibility, requiring precision, clarity, and strategic placement to ensure effective communication (

Table 2). For individuals with mobility impairments, particularly wheelchair users, signage should adhere to universal design principles, incorporating the International Symbol of Accessibility (ISA) alongside universally recognized pictograms and high-contrast directional arrows [

20]. These elements enhance legibility and usability, guiding users efficiently to accessible facilities. Additionally, factors such as font size, color contrast, tactile and Braille elements, and mounting height should align with established accessibility standards, such as those outlined by the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and ISO 21542 on building accessibility [

14,

15,

16]. Properly designed signage not only facilitates independent mobility but also promotes inclusivity and equal access in public spaces.

- i.

-

Parking Spaces: Designated parking spaces for individuals with disabilities must be marked in blue and display the International Accessibility Symbol, both on the ground and on signage positioned at a height of 1.50 meters. Clear wayfinding signage should guide users from the parking entrance to these spaces. These spaces must be directly connected to entrances or adjacent sidewalks via inclined surfaces at least 1.20 meters wide, with a slope not exceeding 6%. The cross slope should not exceed 1% to ensure ease of access. Parking spaces should be designed to accommodate different vehicle sizes:

- ii.

Pedestrian Pathways and Movement: Cross-sectional Slope: Pedestrian pathways should maintain a maximum cross-sectional slope of 1-2%.

- iii.

Walking Paths: Walking paths should have a compact, smooth, and anti-slip surface. For visually impaired individuals, tactile guiding paths must be integrated to ensure safe navigation.

- iv.

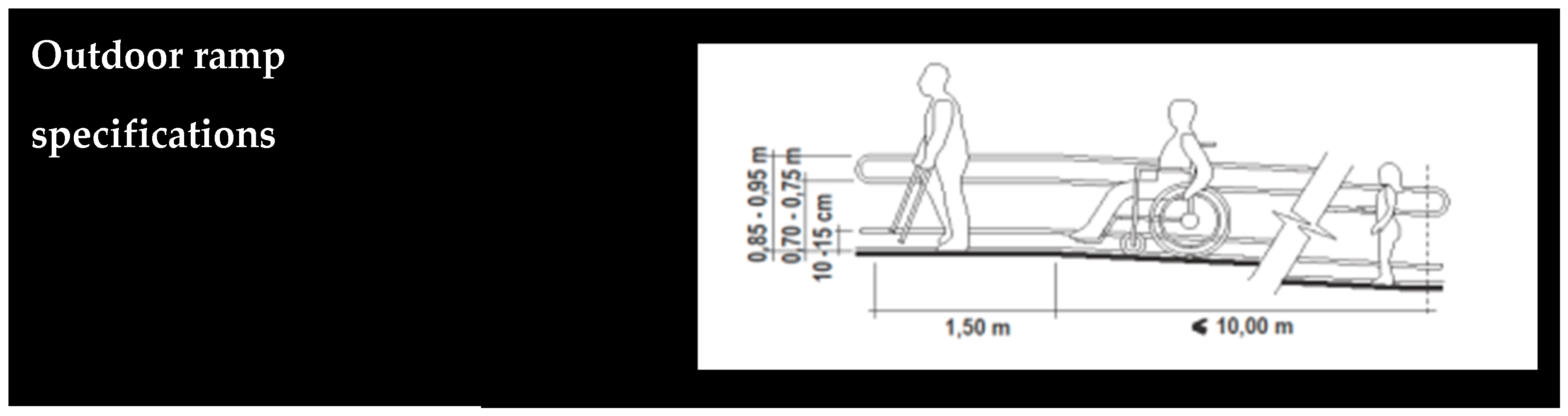

Ramps: Ramp gradients should be designed based on the required elevation change, with slope and length carefully calibrated to ensure safe and efficient movement for wheelchair users and individuals with mobility impairments (

Table 3). For ramps, the requirement for railings is contingent on their length. Ramps shorter than 1.50 meters necessitate a railing on at least one side, whereas ramps exceeding this length must have railings on both sides. Conversely, if the ramp’s length is under 0.60 meters, the installation of a railing is not required. The design of railings for ramps requires them to have a minimum height of 1.10 meters. Additionally, they must be constructed in a manner that prevents any individual from slipping through them, thereby ensuring safety against falls. For outdoor ramps, the installation of double-height handrails is mandated at heights of 0.70 meters and 0.90 meters, accompanied by a metal rod positioned between 0.10 to 0.15 meters high. Furthermore, every 10 meters of ramp length necessitates a landing platform, which should be at least 1.5 meters in length (

Figure 2).

- v.

Spaces for Public Gatherings: Public spaces must accommodate individuals with disabilities, ensuring that wheelchair-accessible areas are integrated into spectator sections. These areas should be spread across different levels and located near spaces for accompanying ambulant individuals. The required ratio of wheelchair spaces varies with seating capacity (e.g., 3 spaces per 50 seats, 5 spaces for 51-100 seats, and 2% of total seating for larger areas). Special attention is given to the design of changing rooms and shower facilities for accessibility.

- vi.

Pedestrian Paths, Sidewalks, and Squares: Public sidewalks and pedestrian paths must be designed for continuous accessibility. Surfaces must minimize slipping risks, and the pedestrian walkway zone should maintain a minimum width of 1.20 meters, free from obstacles. In areas where the walkway width is constrained, solutions such as adjusting sidewalk height or road elevation should be considered. The minimum unobstructed height within walking zones should be 2.20 meters to ensure accessibility.

- vii.

Slope & Surface Materials: Surfaces must be designed to avoid slip hazards, using smooth, solid, and anti-slip materials in both dry and wet conditions.

- viii.

Sidewalks & Ramps: Sidewalks must align with adjacent building entrances, either level or with ramps (max slope 6%). Ramps between sidewalks and pavements must follow the same slope criteria.

- ix.

Cross Slope of Sidewalks: The cross slope of sidewalks should be between 1-2% for effective rainwater drainage.

- x.

Floor Coverings: Joints in floor coverings must not exceed 0.010 meters in width and must be flush with the floor level to prevent tripping or wheelchair entrapment.

- xi.

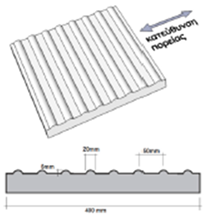

Water Drainage Grates: Drainage grates should have bars perpendicular to pedestrian traffic or a dense mesh with 0.010m clearances.

- xiii.

Tactile Floor Markings: In areas with level differences, tactile floor markings must be placed 0.40m from the ends of ramps to guide visually impaired individuals.

3.4.2. Individuals with Visual Impairments

This section outlines the requirements for tactile walking guides, their dimensions, and their installation standards to support individuals with visual impairments [

14,

15,

21]. The tactile paths should help individuals move safely and independently in public spaces.

-

i.

Signage for individuals with visual impairments:must incorporate Braille to enhance accessibility and comprehension for visually impaired individuals.

-

ii.

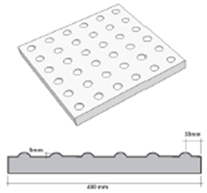

Blind Walking Guide (Tactile Paving):A tactile guide path is used to assist visually impaired individuals in navigating public spaces. The path consists of distinct strips of plates with different textures and colors to provide tactile and visual cues for safer movement.

-

iii.

Dimensional Standards:The minimum width of the tactile guide path must be 0.40 meters.

-

iv.

The guide should be positioned within the free pedestrian walkway, ideally located on the side closest to the road for safety.

-

v.

Sidewalk Tile Specifications:The tiles used for the tactile guide path are made from precast concrete with a yellow color for high visibility. The surface features a special texture to be easily distinguishable underfoot by individuals with visual impairments. The tiles follow the CYS EN TS 15209:2008 standards, and each tile measures 400mm by 400mm with a thickness of 50mm.

-

vi.

-

Tactile Ground Surface Indicators (TGSI)are presented in Table 4:

Type A (GUIDANCE): For guiding individuals along safe paths.

Type B (DANGER): To indicate hazardous areas or obstacles.

Type C (WARN): To provide warning of changes or potential dangers in the path.

4. The Case Study

4.1. Site Context

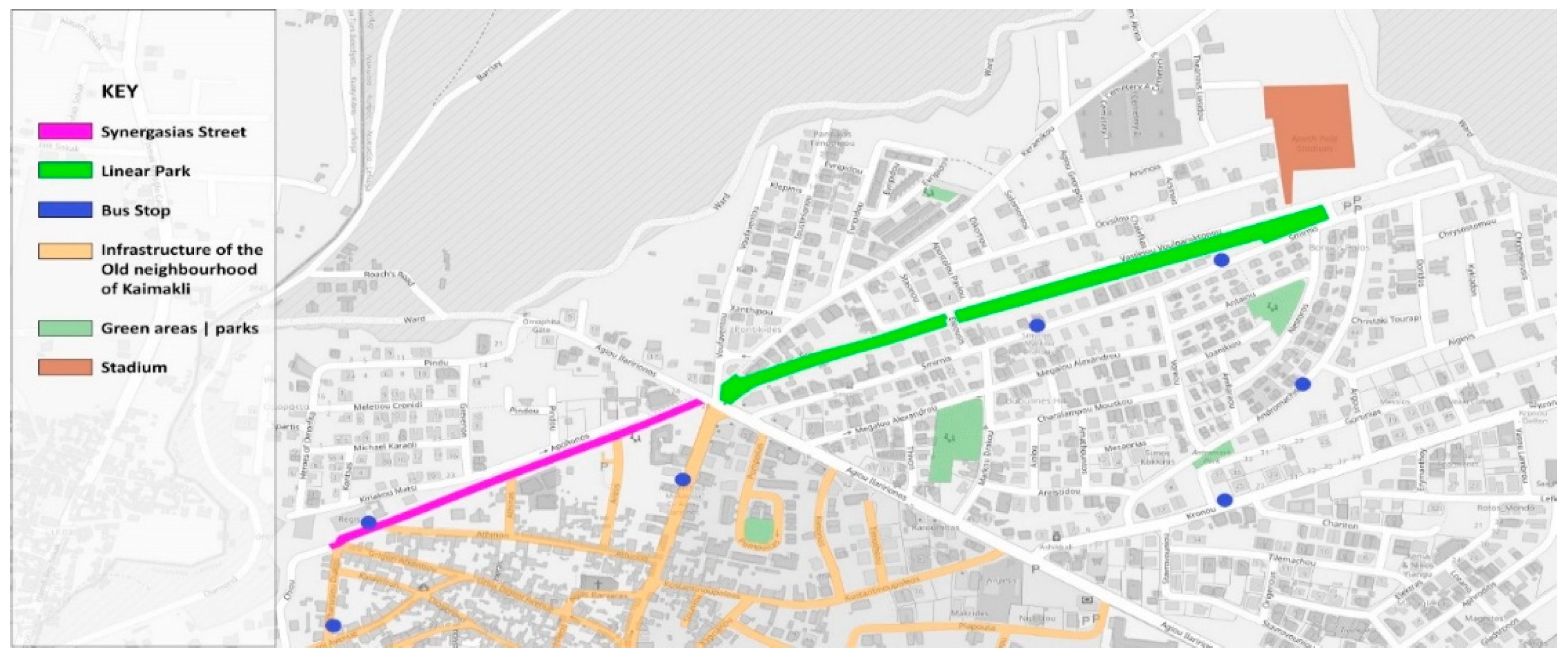

The Kaimakli Linear Park, situated in the historically rich and socially diverse neighborhood of Kaimakli in Nicosia, Cyprus, serves as the focus of this study. As illustrated in

Figure 3, the park runs longitudinally through the neighborhood along Synergasias Street and intersects a series of diverse urban typologies, from dense residential areas to civic and athletic facilities.

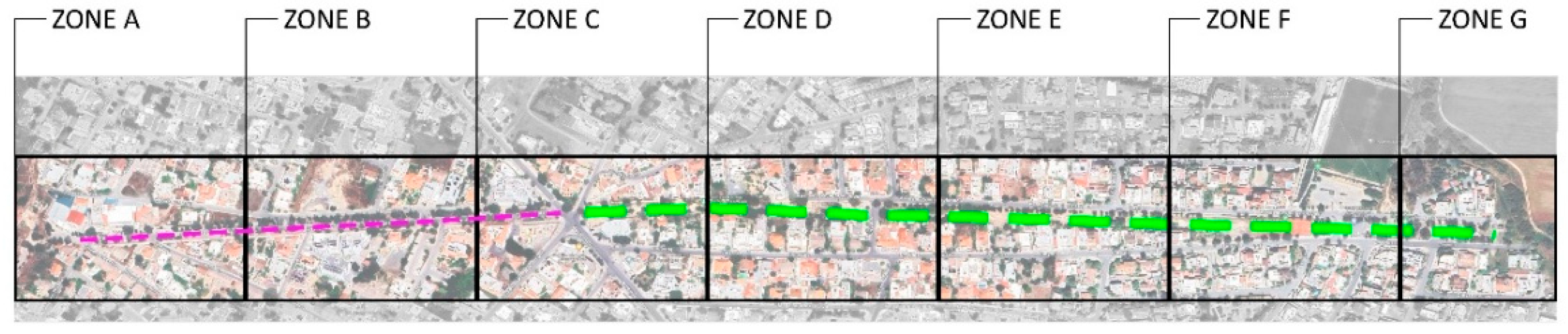

The park

’s spatial sequence has been divided into seven distinct zones—A through G—each corresponding to a unique spatial character and functionality, as outlined in

Figure 4.

4.2. Observational Analysis and Key Findings

Zone A: Old Neighbourhood of Kaimakli

Zone A presented in

Figure 5, acts as a gateway, setting the precedent for accessibility and inclusivity. The presence of obstacles along designated routes for visually impaired individuals, issues arising from the placement of construction materials, and the constraints caused by the uneven pavement are focal points. Moreover, the accessibility of historical elements like the Old Railway route is evaluated, underscoring the balance between preserving heritage and ensuring inclusivity.

The area in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, is pivotal in evaluating the park’s accessibility in terms of mobility for wheelchair users and the visually impaired. The absence of necessary infrastructure, such as ramps and consistent bollard placement, is a primary concern. The incline of pedestrian routes in Zone B is another crucial aspect, requiring compliance with regulations for maximum slopes.

The zone in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 encompasses the entrance and central area of the linear park. This zone’s evaluation is centered around the pathway conditions for visually impaired individuals, the presence of necessary ramps, restroom accessibility, and the quality of sitting areas. The entrance is assessed for any barriers and the choice of materials, while seating is evaluated for its inclusivity.

The zone in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 includes a patio shade structure and two entry points. Issues include vandalism, inaccessibility for wheelchair users, blocked entry routes, and lack of interconnected pathways. The evaluation emphasizes the importance of continuity in accessibility and inclusive design.

The zone in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13, includes the park’s amphitheatre and outdoor gym. Issues include damaged flooring materials, steep inclines exceeding 6%, and design flaws that make the amphitheatre and gym inaccessible to users with disabilities. Recommendations include pavement redesign and installation of accessible equipment.

Zone F in

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 includes the football field and the nearby bus stop. Key concerns are the lack of connection between the bus stop and park, absence of seating and shaded areas, narrow pathways, and non-compliant changing rooms and parking spaces. The field is poorly integrated with the rest of the park.

Zone G,

Figure 16,

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 highlights the consequences of inadequate maintenance and poor planning. The lack of adaptive play equipment, deteriorating infrastructure, and barriers to access make this a critical area for intervention.

To summarize and structure the site analysis, the park was divided into seven key zones based on functionality, spatial configuration, and connectivity. Each zone was assessed using an observational audit informed by Universal Design principles.

Table 5, summarizes the accessibility strengths, key barriers, and priority interventions for each zone, providing a snapshot of inclusion performance and physical usability across the site.

4.3. Accessibility Evaluation by Design Principle

Equitable Use: Multiple zones, particularly A, E, F, and G, do not provide equitable access for users with disabilities.

Flexibility in Use: Seating and gym equipment are not adaptable. No provisions exist for sensory or inclusive elements.

Simple and Intuitive Use: Absence of signage, tactile indicators, and maps across all zones.

Perceptible Information: No Braille signage or auditory information systems exist.

Tolerance for Error: Poor surface conditions, steep ramps, and obstacles pose safety risks.

Low Physical Effort: Steep slopes and lack of rest areas make navigation physically demanding.

Size and Space for Approach and Use: Many paths and furniture arrangements do not support wheelchair users or groups.

4.4. Summary of Challenges

Recurring accessibility issues identified across the zones include:

Non-compliance with Regulation 61HA.

Physical barriers such as narrow paths and uneven surfaces.

Poor maintenance and unsafe infrastructure.

Absence of inclusive amenities and signage.

Lack of spatial and functional integration between zones.

These shortcomings result in a park that is not accessible or inclusive, thus excluding many potential users.

4.5. Potential for Transformation

Despite these challenges, the park holds significant potential. Its linear layout supports phased implementation of accessibility interventions [

22]. Immediate opportunities include:

Inclusive redesign of the amphitheatre and outdoor gym (Zone E);

Restroom and seating upgrades (Zone C);

Adaptive play features and improved pathway connectivity (Zone G);

Bus stop and parking integration (Zones D and F).

By following Universal Design principles and engaging the community, Kaimakli Linear Park can become a national model for inclusive urban regeneration [

13].

4.6. Critical / SWOT Analysis

A SWOT analysis of the proposed enhancements for Kaimakli Linear Park highlights both the transformative potential and the practical challenges involved in achieving an inclusive and accessible urban environment [

23].

Among the key strengths is the emphasis on Universal Design principles, particularly in improving accessibility through the installation of ramps, tactile surfaces, and adjusted pathways. These measures aim to benefit a diverse user base, including individuals with disabilities, elderly residents, and families with young children. The proposed redesign of restrooms, seating areas, the amphitheatre, and the outdoor gym supports broader inclusivity and enhances community engagement by encouraging diverse forms of social interaction.

However, the proposed interventions are not without weaknesses. Budget constraints present a significant limitation, particularly given the scope and scale of the redesign. The addition of specialized features—such as accessible gym equipment and tactile markings—may also introduce higher maintenance demands over time. Furthermore, construction activities could temporarily disrupt park access and use, potentially deterring current visitors.

Several opportunities emerge from this transformation effort. If successfully implemented, the project could serve as a model for inclusive urban green spaces in Cyprus and beyond. The enhancements could also facilitate environmental improvements through the use of sustainable materials and practices, while simultaneously raising public awareness about the importance of inclusive design. Strengthened community ties and increased park usage by a more diverse population are further potential benefits.

Nonetheless, potential threats must be acknowledged. Resistance from certain community groups especially if familiar park features are altered—may hinder public support. Regulatory compliance and permitting processes could delay implementation, and environmental disturbances during construction may impact local biodiversity. Additionally, there is a risk that accessible features could be subject to misuse or vandalism, increasing long-term costs.

In summary, while the redevelopment of Kaimakli Linear Park presents substantial opportunities for improving accessibility and quality of life, its success depends on careful planning, stakeholder engagement, regulatory oversight, and sustainable maintenance strategies. Addressing these factors will be key to transforming the park into an inclusive and resilient public space.

5. Conclusions

This study has examined the principles and challenges of accessible urban design, focusing on its impact on inclusivity, mobility, and sustainability. The findings highlight a persistent gap between theoretical frameworks advocating universal accessibility and the practical implementation of inclusive urban policies. Despite legislative efforts and design guidelines, urban environments often fail to meet the needs of individuals with disabilities and other marginalized groups.

Before proposing policy solutions, it is important to understand how systemic accessibility drivers translate into design actions and user-level impacts.

Figure 18 presents a conceptual model that illustrates this pathway from foundational inputs (such as guidelines and participatory planning) through urban design interventions to measurable social outcomes in public space use. The framework illustrates how systemic decisions translate into physical interventions that shape the everyday experiences of diverse users.

Moreover, a key finding of this research is the necessity of a multi-stakeholder approach in accessibility planning. The study underscores that urban accessibility should not be seen as a niche concern but rather as an essential aspect of sustainable urban development. Inclusive design benefits not only individuals with disabilities but also aging populations, parents with young children, and temporary users such as tourists.

Moreover, the research highlights significant limitations in current urban accessibility measures, particularly in cities where historical architecture poses challenges for adaptation. While technological advancements, such as smart city solutions and assistive technologies, offer promising interventions, they are not yet widely implemented in urban planning.

This study also emphasizes the importance of data-driven decision-making in urban accessibility. By integrating real-time data collection and community feedback mechanisms, policymakers can ensure that accessibility interventions are responsive to actual user needs rather than based solely on prescriptive regulations. Policy Implications include:

The findings suggest that governments and urban planners should:

Adopt mandatory accessibility audits for public infrastructure.

Encourage community participation in urban planning processes to reflect diverse needs.

Implement smart technology solutions, such as sensor-based navigation for visually impaired individuals.

Develop incentive structures for private developers to incorporate accessibility features in new constructions.

5.1. Policy Recommendations for Inclusive Urban Design

The analysis of Kaimakli Linear Park highlights not only physical design shortcomings but also systemic governance gaps that impact the realization of accessibility goals. To improve the inclusiveness and long-term functionality of urban green spaces, the following policy directions are recommended:

- I.

Mandate accessibility audits

Local authorities should require regular, standardized accessibility audits of public parks, based on internationally recognized frameworks such as ISO 21542 and the CRPD guidelines [

9,

24]. This would enable early detection of barriers and inform targeted upgrades.

- II.

Integrate Universal Design into planning codes

UD principles should be embedded in national and municipal planning regulations, not treated as optional or supplementary. Minimum standards must be enforced at both the design and construction phases.

- III.

Institutionalize participatory design

Persons with disabilities and representative organizations should be involved in the co-design and consultation phases of public space projects. Their experiential knowledge can ensure that design decisions address real-world usability.

- IV.

Provide financial incentives for compliance

Municipalities can introduce grants, tax benefits, or co-financing schemes to encourage private developers or public agencies to proactively adopt inclusive design beyond minimum legal requirements.

- V.

Adopt smart tools for inclusive navigation

Digital innovations—such as interactive accessibility maps, real-time sensor feedback, or wayfinding apps—can enhance usability for a wider range of users and support dynamic adaptation of public spaces.

5.2. Future Research

Future research should expand the evidence base for inclusive urban design by conducting cross-country comparative studies that highlight systemic differences in accessibility planning and implementation. Such studies can illuminate best practices and contextual barriers across diverse regulatory and cultural environments. Moreover, longitudinal research is needed to assess the long-term effectiveness of Universal Design (UD) interventions in public parks, focusing on user experience, behavioral change, and maintenance outcomes over time.

An emerging and underexplored area involves the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and smart technologies to support real-time accessibility solutions—such as sensor-based navigation tools, AI-driven urban modeling, and dynamic user feedback systems [

25]. Additionally, future work could develop economic feasibility models for accessibility improvements, comparing upfront investments with long-term social, health, and economic benefits. This would support evidence-based decision-making and policy justification.

Future applications of AI could include real-time accessibility mapping using sensors and geospatial tools, adaptive lighting and signage systems, and predictive maintenance of inclusive infrastructure based on usage patterns. These tools can enhance the responsiveness and adaptability of urban environments.

Finally, co-creation and participatory research methods involving persons with disabilities, urban planners, and policymakers can lead to more grounded, human-centered solutions. Future studies should explore how inclusive governance models can improve the design and monitoring of accessible public space.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation |

Full Term |

| UD |

Universal Design |

| PwD |

Persons with Disabilities |

| ISO |

International Organization for Standardization |

| CRPD |

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities |

| EU |

European Union |

| N/A |

Not Applicable (used in observational tables, possibly implied) |

References

- Brussel, M.; Zuidgeest, M.; Pfeffer, K.; van Maarseveen, M. Access or Accessibility? A Critique of the Urban Transport SDG Indicator. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Information 2019, 8, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S. , & Kaur, N. (2024). Leaving no one behind: Achieving the sustainable development goals through accessibility for people with disabilities. International Journal of Educational Communications and Technology, 4(1), 16-26.

- Magidimisha-Chipungu, H. H. (2024). A Global Perspective on Planning for Disability. In People Living with Disabilities in South African Cities: A Built Environment Perspective on Inclusion and Accessibility (pp. 9-28). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Steinfeld, E. , & Maisel, J. (2012). Universal design: Creating inclusive environments. John Wiley & Sons.

- Story, M.F. Maximizing Usability: The Principles of Universal Design. Assist. Technol. 1998, 10, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public open space. (n.d.). Wikipedia. Retrieved , 2024, from https://en.wikipedia. 2 January.

- Cuesta, R.; Sarris, C.; Signoretta, P.; Moughtin, J. Urban Design: Method and Techniques; Taylor & Francis: London, United Kingdom, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeili, M.; Sheydayi, A.; Jamalabadi, F. A Systematic Review of Qualitative and Quantitative Content Analysis Applications in Urban Planning Research: Proposing a Mixed Method Approach. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2025, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 21542:2021 Building construction — Accessibility and usability of the built environment, Retrieved 22 January, 2025, from https://www.iso.org/standard/71860.

- Praça, B. American with Disabilities Act (ADA) 38, 102 automobile-centric planning 35 automobile cities 15 Batista, Alberti 75. health, 109, 138.

- Hendriks, A. (2007). UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. European Journal of Health Law, 14(3), 273-298.

- Lynch, H. , Moore, A., Edwards, C., & Horgan, L. (2019). Community parks and playgrounds: Intergenerational participation through universal design.

- Kopeva, A.; Ivanova, O.; Zaitseva, T. Application of Universal Design principles for the adaptation of urban green recreational facilities for low-mobility groups (Vladivostok case-study).CONFERENCE NAME, LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 022018.

- Cook, T. M. (1991). The americans with disabilities act: The move to integration. Temp. LR, 64, 393.

- Directive (EU) 2019/882 of the European Parliament and of the Council of on the accessibility requirements for products and services, Retrieved January 22, 2025, from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/? 17 April 3201.

- THE 17 GOALS | Sustainable Development. Accessed: Sep. 20, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://sdgs.un.

- Regulation for accessibility of the public places build environment, Retrieved , 2025, from https://www.cylaw.org/nomoi/arith/2017_1_111. 22 January.

- Accessibility: Principles And Guidelines, Retrieved , 2025, from https://opak.org. 22 January.

- Null, R. (Ed.) . (2013). Universal design: Principles and models. CRC Press.

- Guidance on Use of the International Symbol of Accessibility, Under the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Architectural Barriers Act, , 2017, Retrieved January 22, 2025, from https://www.access-board.gov/files/aba/guides/ISA-guidance. 27 March.

- Horton, E.L.; Renganathan, R.; Toth, B.N.; Cohen, A.J.; Bajcsy, A.V.; Bateman, A.; Jennings, M.C.; Khattar, A.; Kuo, R.S.; Lee, F.A.; et al. A review of principles in design and usability testing of tactile technology for individuals with visual impairments. Assist. Technol. 2016, 29, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, V. , & Mahato, B. (2021). Designing urban parks for inclusion, equity, and diversity. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 14(4), 457-489.

- Leigh, D. (2009). SWOT analysis. Handbook of Improving Performance in the Workplace: Volumes 1-3, 115-140.

- Gómez, L.E.; Monsalve, A.; Morán, M.L.; Alcedo, M.Á.; Lombardi, M.; Schalock, R.L. Measurable Indicators of CRPD for People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities within the Quality of Life Framework. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2020, 17, 5123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froehlich, J. E. , Li, C. , Hosseini, M., Miranda, F., Sevtsuk, A., & Eisenberg, October). The Future of Urban Accessibility: The Role of AI. In Proceedings of the 26th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (pp. 1-6)., Y. (2024. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Universal Design Principles in Public Park Planning.

Figure 1.

Universal Design Principles in Public Park Planning.

Figure 2.

Outdoor ramp specifications.

Figure 2.

Outdoor ramp specifications.

Figure 3.

Illustrated map of Kaimakli neighbourhood.

Figure 3.

Illustrated map of Kaimakli neighbourhood.

Figure 4.

Zone separation map.

Figure 4.

Zone separation map.

Figure 5.

Zone A- Old neighbourhood of Kaimakli Map.

Figure 5.

Zone A- Old neighbourhood of Kaimakli Map.

Figure 6.

Zone B- Crossroad area.

Figure 6.

Zone B- Crossroad area.

Figure 7.

Zone B- Crossroad area map.

Figure 7.

Zone B- Crossroad area map.

Figure 8.

Zone C- Entrance and central area.

Figure 8.

Zone C- Entrance and central area.

Figure 9.

Zone C- Entrance and central area map.

Figure 9.

Zone C- Entrance and central area map.

Figure 10.

Zone D- Patio and entry point.

Figure 10.

Zone D- Patio and entry point.

Figure 11.

Zone D- Patio and entry point map.

Figure 11.

Zone D- Patio and entry point map.

Figure 12.

Zone E- Amphitheatre and outdoor gym.

Figure 12.

Zone E- Amphitheatre and outdoor gym.

Figure 13.

Zone E-Amphitheatre and outdoor gym map.

Figure 13.

Zone E-Amphitheatre and outdoor gym map.

Figure 14.

Zone F- Sports Fields and Bus Stop.

Figure 14.

Zone F- Sports Fields and Bus Stop.

Figure 15.

Zone F-Sports Fields and Bus Stop Map.

Figure 15.

Zone F-Sports Fields and Bus Stop Map.

Figure 16.

Zone G: Neglected Section-a.

Figure 16.

Zone G: Neglected Section-a.

Figure 17.

Zone G- Neglected Section Map.

Figure 17.

Zone G- Neglected Section Map.

Figure 18.

Zone G- Neglected Section-b.

Figure 18.

Zone G- Neglected Section-b.

Figure 18.

Conceptual model linking accessibility inputs, urban design strategies, and inclusive user outcomes in public park environments.

Figure 18.

Conceptual model linking accessibility inputs, urban design strategies, and inclusive user outcomes in public park environments.

Table 1.

Basic Anthropometric dimensions.

Table 2.

Signage for wheelchair users.

Table 3.

Ramp slope specifications.

Table 3.

Ramp slope specifications.

| Maximum slope |

Maximum length (m) |

Maximum height (m) |

Handrail required |

| 5.0% |

10.00 |

0.500 |

Yes |

| 5.5% |

8.00 |

0.440 |

Yes |

| 6.0% |

5.00 |

0.300 |

Yes |

| 6.5% |

4.00 |

0.260 |

Yes |

| 7.0% |

3.00 |

0.210 |

Yes |

| 7.5% |

1.50 |

0.120 |

Yes |

| 8.0% |

0.60 |

0.050 |

No |

| 8.3% |

0.50 |

0.040 |

No |

| 10.0% |

0.30 |

0.030 |

No |

| 12.5% |

0.20 |

0.025 |

No |

| 13.3% |

0.15 |

0.020 |

No |

Table 4.

Tactile Ground Surface Indicators.

Table 5.

Accessibility Audit Results by Zone.

Table 5.

Accessibility Audit Results by Zone.

| Zone |

Accessibility Strengths |

Key Barriers |

Priority Interventions |

| A |

Historic context |

Uneven pavement, obstacles |

Level surface, tactile paths |

| B |

Connectivity |

Lack of ramps, poor incline |

Add compliant ramps |

| C |

Central location |

Limited signage, seating |

Upgrade signs, accessible toilets |

| D |

Entry & patio |

Vandalism, blocked routes |

Clean access, connect pathways |

| E |

Amphitheatre & gym |

Functional layout |

Inaccessible equipment |

| F |

Bus stop & fields |

None |

No seating, poor connection |

| G |

Green edge |

Neglected |

All infrastructure deficient |

Table 6.

SWOT Analysis of Accessibility Interventions in Kaimakli Linear Park.

Table 6.

SWOT Analysis of Accessibility Interventions in Kaimakli Linear Park.

| Strengths |

Weaknesses |

| Adoption of UD principles |

Budget constraints |

| Inclusive redesign plans |

High maintenance demand |

| Community engagement potential |

Temporary disruption during upgrades |

| Opportunities |

Threats |

| Replicability across cities |

Community resistance to change |

| Smart tech integration |

Vandalism, regulatory delays |

| Environmental upgrades |

Biodiversity disruption |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).