Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Urban Parks Concept and Benefits

2.2. Planning Context of Urban Parks

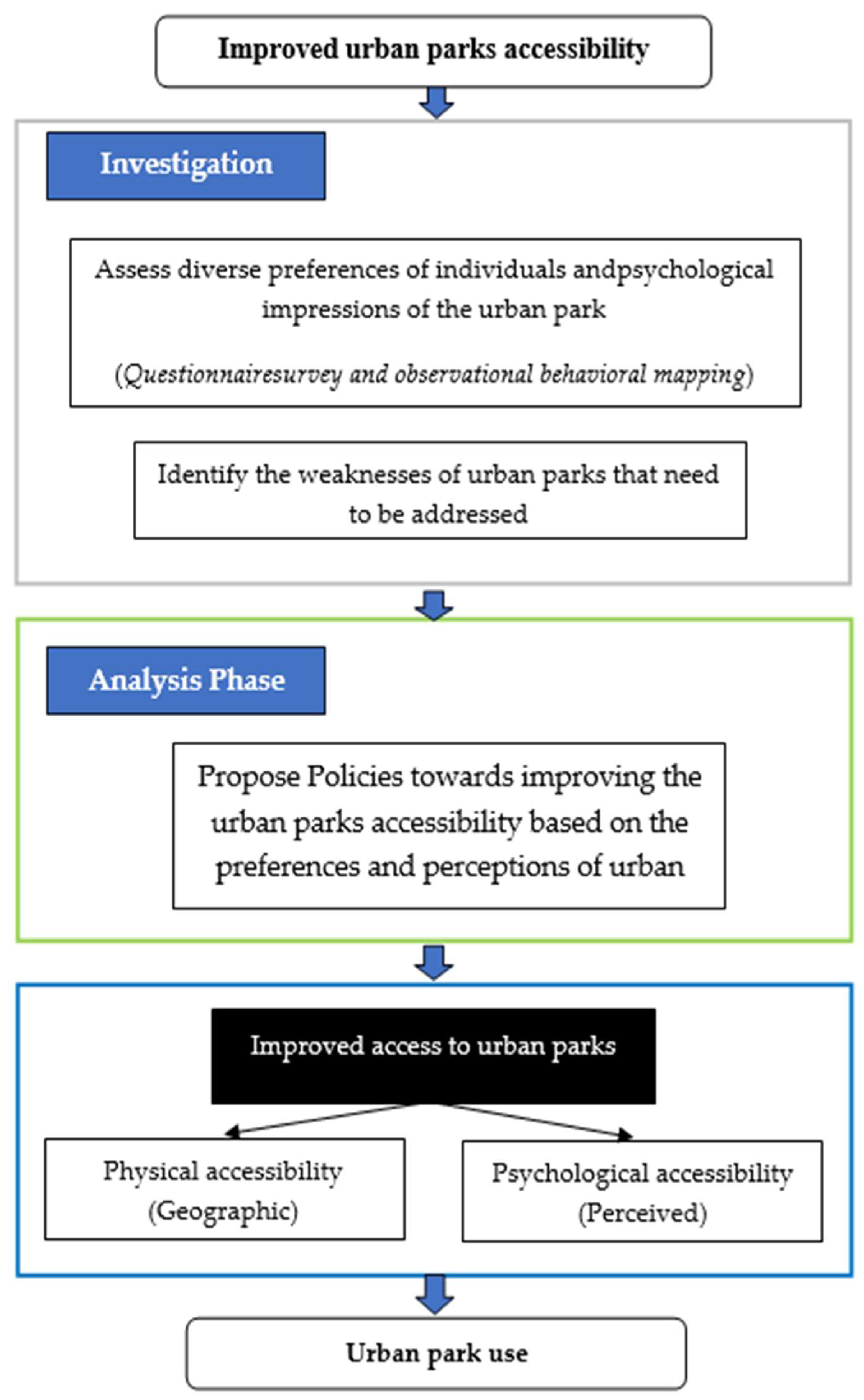

2.3. Urban Parks Accessibility

2.4. Measurement Tools of Urban Parks Accessibility

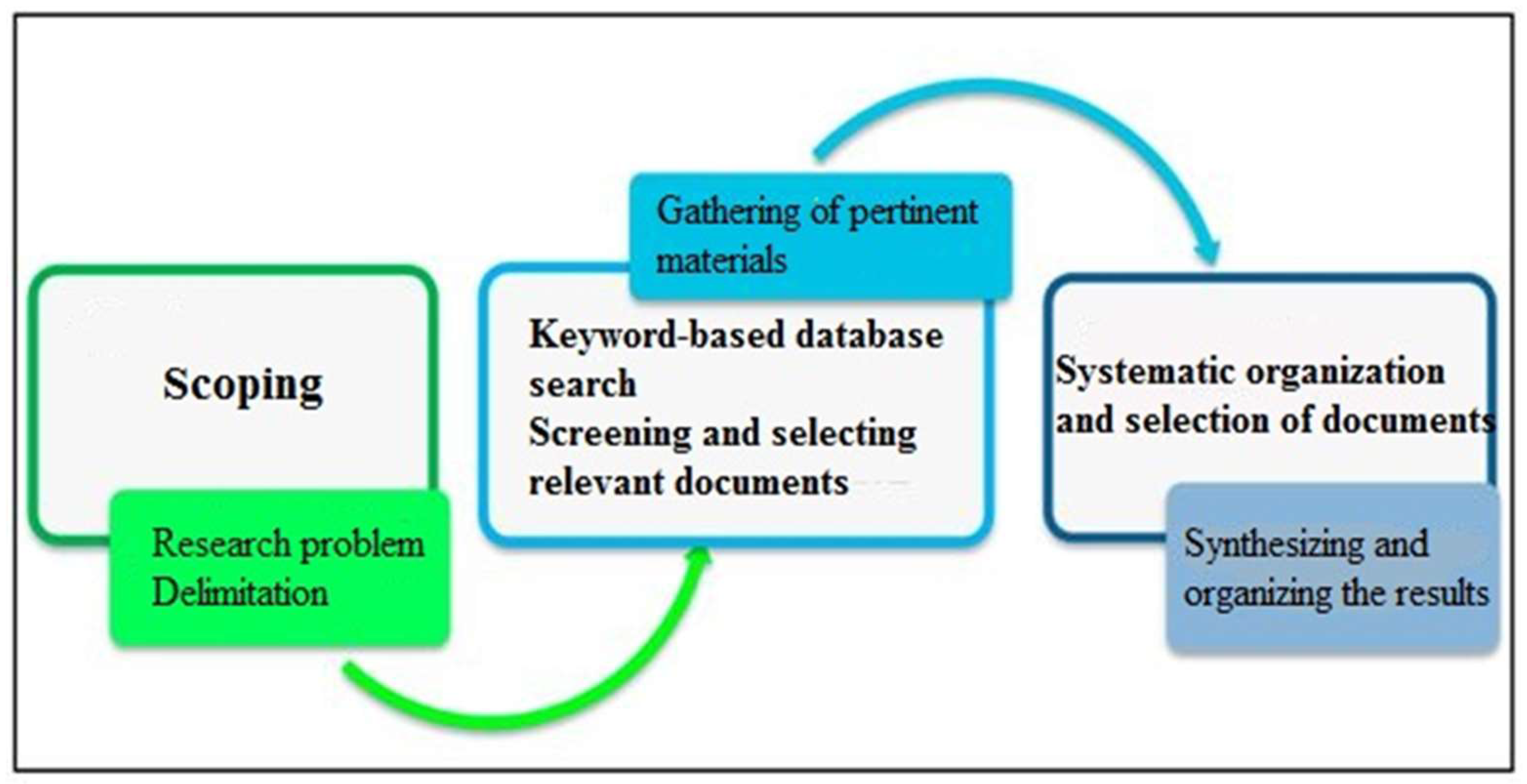

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNFPA. (2007). State of world population 2007: Unleashing the potential of urban growth NY. United Nations Population Fund.

- Talen, E. (1997). The social equity of urban service distribution: An exploration of park access in Pueblo, Colorado, and Macon, Georgia. Urban Geography, 18(6), 521–541.

- Byrne, J., &Wolch, J. (2009). Nature, race, and parks: Past research and future direc- tions for geographic research. Progress in Human Geography, 33(6), 743–765.

- Brown, G., Schebella, M. F., & Weber, D. (2014). Using Participatory GIS to measure physical activity and urban park benefits. Landscape and Urban Planning, 121, 34–44. [CrossRef]

- Chiesura, A. (2004). The role of urban parks for the sustainable city. Landscape and Urban Planning, 68(1), 129–138. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D., Jin, J., 2018. Does happiness data say urban parks are worth it? Landsc. Urban Plan. 178, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Ward Thompson, C., 2011. Linking landscape and health: the recurring theme. Landsc.Urban Plan. 99 (3), 187–195. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.K., Svendsen, E.S., Sonti, N.F., Johnson, M.L., 2016. A social assessment of urban parkland: analyzing park use and meaning to inform management and resi- lience planning. Environ. Sci. Policy 62, 34–44. [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, S. (2001). Measuring the accessibility and equity of public parks: A case study using GIS. Managing Leisure, 6,201–219. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, O., Tratalos, J. A., Armsworth, P. R., Davies, R. G., Fuller, R. A., Johnson, P., & Gaston, K. J. (2007). Who benefits from access to green space? A case study from Sheffeld, UK. Landscape and Urban Planning, 83, 187–195. [CrossRef]

- Parra, D. C., Gomez, L. F., Fleischer, N. L., & Pinzon, J. D. (2010). Built environment characteristics and perceived active park use among older adults: Results from a multilevel study in Bogotá. Health & Place, 16, 1174–1181. [CrossRef]

- McCormack, G. R., Rock, M., Toohey, A. M., &Hignell, D. (2010). Characteristics of urban parks associated with park use and physical activity: A review of qualitative research. Health & Place, 16, 712–726. [CrossRef]

- Kaczynski, A. T., Potwarka, L. R., & Saelens, B. E. (2008). Association of park size, distance, and features with physical activity in neighborhood parks. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 1451–1456. [CrossRef]

- Ries, A. V., Voorhees, C. C., Roche, K. M., Gittelsohn, J., Yan, A. F., & Astone, N. M. (2009). A quantitative examination of park characteristics related to park use and physical activity among urban youth. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(Suppl. 3), 64–70. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, W. G. (1959). How accessibility shapes land use. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 25, 73–76. [CrossRef]

- Weibull, J. W. (1976). An axiomatic approach to the measurement of accessibility. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 6, 357–379. [CrossRef]

- van der Vlugt, A.-L.; Curl, A.; Wittowsky, D. What about the People? Developing Measures of Perceived Accessibility from Case Studies in Germany and the UK. Appl. Mobilities 2019, 4, 142–162. [CrossRef].

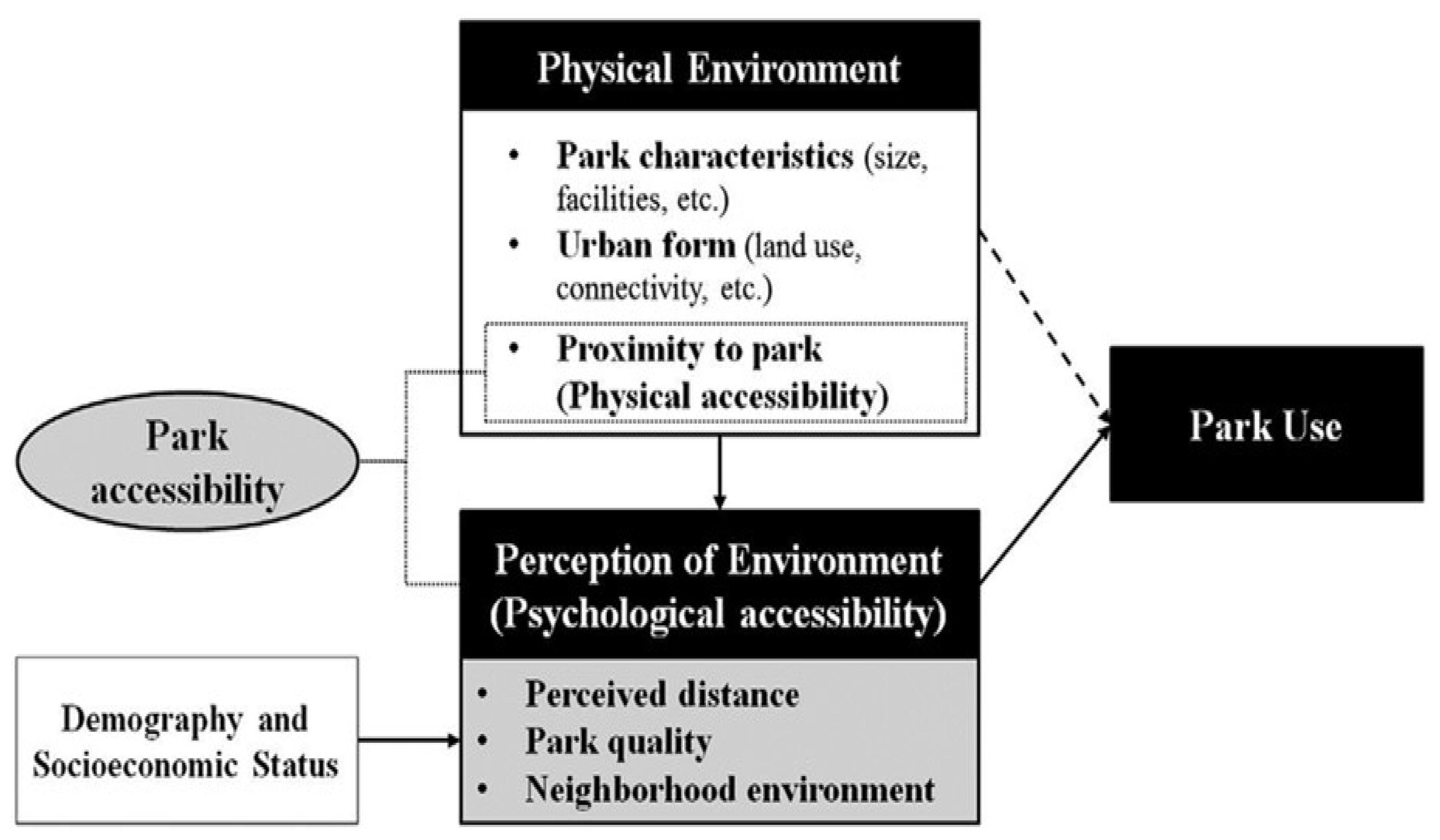

- Wang, D., Brown, G., Liu, Y., & Mateo-Babiano, I. (2015). A comparison of perceived and geographic access to predict urban park use. Cities, 42, 85–96.

- Leslie, E., Cerin, E., & Kremer, P. (2010). Perceived neighborhood environment and park use as mediators of the effect of area socio-economic status on waiking behaviors. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 7, 802–810.

- Stanis, S. A. W., Schneider, I. E., Shinew, K. J., Chavez, D. J., & Vogel, M. C. (2009). Physical activity and the recreation opportunity spectrum: Differences in important site attributes and perceived constraints. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 27, 73–91.

- Jenerette, D. G., Harlan, S. L., Stefanov, W. L., & Martin, C. A. (2011). Ecosystem services and urban heat riskscape moderation: Water, green spaces, and social inequality in Phoenix, USA. Ecological Applications, 21(7), 2637–2651. [CrossRef]

- Van Den Berg, M., Wendel-Vos, W., Van Poppel, M., Kemper, H., Van Mechelen, W., & Maas, J. (2015). Health benefits of green spaces in the living environment: A sys- tematic review of epidemiological studies. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 14(4), 806–816. [CrossRef]

- Walch, J. M., Rabin, B. S., Day, R., Williams, J. N., Choi, K., & Kang, J. D. (2005). The effect of sunlight on postoperative analgesic medication use: A prospective study of patients undergoing spinal surgery. Psychosomatic Medicine, 67(1), 156–163. [CrossRef]

- Heerwagen, J. (2009). Biophilia, Health and Well-being. In: Restorative Commons: Creating Health and Well-being through Urban Landscapes (pp. 39–57).

- Takano, T., Nakamura, K., & Watanabe, M. (2002). Urban residential environments and senior citizens’ longevity in megacity areas: The importance of walkable green spaces. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 56(12), 913–918. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, E. A., Pearce, J., Mitchell, R., & Kingham, S. (2013). Role of physical activity in the relationship between urban green space and health. Public Health, 127(4), 318–324.

- Lafortezza, R., Carrus, G., Sanesi, G., & Davies, C. (2009). Benefits and well-being per- ceived by people visiting green spaces in periods of heat stress. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, 8(2), 97–108.

- de Haan, L., & Zoomers, A. (2005). Exploring the frontier of livelihood research. Development and Change (January 2005).

- Maniruzzaman, K. M., Alqahtany, A., Abou-Korin, A., & Al-Shihri, F. S. (2021). An analysis of residents’ satisfaction with attributes of urban parks in Dammam city, Saudi Arabia. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 12(3), 3365-3374.

- Alshehri, R. M., Alzenifeer, B. M., Alqahtany, A. M., Alrawaf, T., Alsayed, A. H., Afify, H. M. N., ... & Alshammari, M. S. (2025). Impact of Urban Green Spaces on Social Interaction Among People in Neighborhoods: Case Study for Jubail, Saudi Arabia.

- Alnaim, A., Dano, U. L., & Alqahtany, A. M. (2025). Framework for Enhancing Social Interaction Through Improved Access to Recreational Parks in Residential Neighborhoods in the Saudi Context: Case Study of Dammam Metropolitan Area.

- Alnaim, A., Dano, U. L., & Alqahtany, A. M. (2025). Factors Influencing Social Interaction in Recreational Parks in Residential Neighborhoods: A Case Study of the Dammam Metropolitan Area, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 17(9), 3810.

- MARUANI, T. & AMIT-COHEN, I. 2007. Open space planning models: A review of approaches and methods. Landscape and Urban Planning, 81, 1-13.

- DAVIES, R. G., BARBOSA, O., FULLER, R. A., TRATALOS, J., BURKE, N., LEWIS, D., WARREN, P. H. & GASTON, K. J. 2008. City-wide relationships between green spaces, urban land use and topography. Urban Ecosystems, 11, 269-287.

- MCCANN, B. A. & EWING, R. 2003. Measuring the health effects of sprawl: A national analysis of physical activity, obesity and chronic disease.

- ALFONZO, M., GUO, Z., LIN, L. & DAY, K. 2014. Walking, obesity and urban design in Chinese neighborhoods. Preventive medicine, 69, S79-S85.

- BADLAND, H., WHITZMAN, C., LOWE, M., DAVERN, M., AYE, L., BUTTERWORTH, I.,HES, D. & GILES-CORTI, B. 2014. Urban liveability: emerging lessons from Australia for exploring the potential for indicators to measure the social determinants of health. Social Science & Medicine, 111, 64-73.

- REYES, M., PÁEZ, A. & MORENCY, C. 2014. Walking accessibility to urban parks by children: A case study of Montreal. Landscape and Urban Planning, 125, 38-47.

- GOLD, S. M. 1973. Urban recreation planning. Journal of Health, Physical Education, Recreation, 44, 79-79.

- Gregory, D., Johnston, R., Pratt, G., Watts, M., & Whatmore, S. (2009). The dictionary of human geography (5th ed.). UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Wendel, H. E. W., Zarger, R. K., & Mihelcic, J. R. (2012). Accessibility and usability: Green space preferences, perceptions, and barriers in a rapidly urbaniz- ing city in Latin America. Landscape and Urban Planning, 107(3), 272–282. [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B., Broomhall, M. H., Knuiman, M., Collins, C., Douglas, K., Ng, K., … Donovan, R. J. (2005). Increasing walking: How important is distance to, attractiveness, and size of public open space? American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28(2 Suppl. 2), 169–176. [CrossRef]

- Gregory, D., Johnston, R. J., & Smith, D. M. (1986). The dictionary of human geography. Oxford: Blackwell Reference.

- Hass, K. (2009). Measuring accessibility of regional parks: A comparison of three GIS techniques. (Dissertation/thesis).

- Wang, D., Brown, G., & Mateo-Babiano, D. (2013). Beyond proximity: An integrated model of accessibility for public parks. Asian Journal of Social Sciences & Human- ities, 2(3), 486–498.

- Ferreira, A., & Batey, P. (2007). Re-thinking accessibility planning: A multi-layer conceptual framework and its policy implications. Town Planning Review, 78(4), 429–458.

- Aday, L. A., & Andersen, R. (1974). A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Services Research, 9(3), 208–220.

- Ball, K., Jeffery, R. W., Crawford, D. A., Roberts, R. J., Salmon, J., & Tim- perio, A. F. (2008). Mismatch between perceived and objective measures of physical activity environments. Preventive Medicine, 47(3), 294–298. [CrossRef]

- Jones, A., Hillsdon, M., & Coombes, E. (2009). Greenspace access, use, and physi- cal activity: Understanding the effects of area deprivation. Preventive Medicine, 49(6), 500–505.

- McCormack, G., Cerin, E., Leslie, E., DuToit, L., & Owen, N. (2008). Objective versus perceived walking distances to destinations: Correspondence and predictive validity. Environment and Behavior, 40(3), 401–425.79–96.

- Scott, M., Evenson, K., Cohen, D., & Cox, C. (2007). Comparing perceived and objectively measured access to recreational facilities as predictors of phys- ical activity in adolescent girls. Journal of Urban Health, 84(3), 346–359. [CrossRef]

- Boehmer, T., Hoehner, C., Wyrwich, K., Brennan Ramirez, L., & Brownson, R. (2006). Correspondence between perceived and observed measures of neighborhood environmental supports for physical activity. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 3, 22–36.

- Kruger, J., Carlson, S. A., & Kohl, H. W., III. (2007). Fitness facilities for adults: Dif- ferences in perceived access and usage. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 32(6), 500–505. [CrossRef]

- Hoehner, C. M., Brennan Ramirez, L. K., Elliott, M. B., Handy, S. L., & Brownson, R. C. (2005). Perceived and objective environmental measures and physical activity among urban adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28(2), 105–116.

- Zondag, B., & Pieters, M. (2005). Influence of accessibility on residential location choice. Transportation Research Record, 1902(1), 63–70.

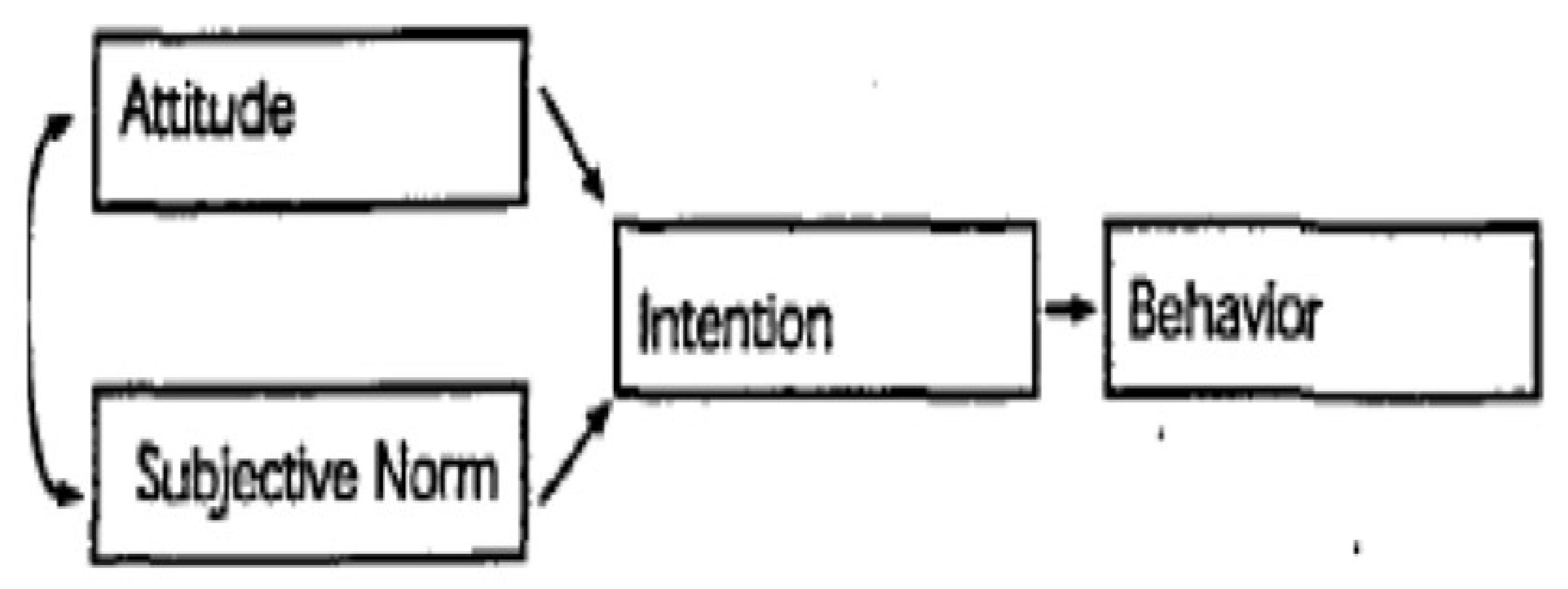

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [CrossRef].

- Zhang, H.; Wang, E. Attitude and Behavior Relationship. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 1, 163–168.

- Elliott, M.A.; Armitage, C.J.; Baughan, C.J. Drivers’ Compliance with Speed Limits: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 964–972. [CrossRef].

- Malle, B.F.; Moses, L.J.; Baldwin, D.A. Intentions and Intentionality: Foundations of Social Cognition; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001.

- Pereira, H.V.; Palmeira, A.L.; Encantado, J.; Marques, M.M.; Santos, I.; Carraça, E.V.; Teixeira, P.J. Systematic Review of Psychological and Behavioral Correlates of Recreational Running. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 624783. [CrossRef].

- FISHBEIN, M. & AJZEN, I. 1975. Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, X. Research on the Changnanjing Historical Trail Protection Effect and Its Priority Improvement Strategy Based on Psychological Accessibility/Pan Yujuan, Zhang Zhengtao, Tian Xiangyang. Planners 2020, 36, 72–77+86.

- Li, L.; Gao, T.; Wang, Y.; Jin, Y. Evaluation of Public Transportation Station Area Accessibility Based on Walking Perception. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2023, in press. [CrossRef].

- Lättman, K.; Olsson, L.E.; Friman, M. A New Approach to Accessibility—Examining Perceived Accessibility in Contrast to Objectively Measured Accessibility in Daily Travel. Res. Transp. Econ. 2018, 69, 501–511. [CrossRef].

- Oriade, A.; Schofield, P. An Examination of the Role of Service Quality and Perceived Value in Visitor Attraction Experience. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 11, 1–9. [CrossRef].

- Lu, Y.; Deng, J.; Han, G.; Lei, J. A study on multidimensional accessibility dynamics assessment ofurban parks. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2022, 38, 92–97.

- Grow, H. M., Saelens, B. E., Kerr, J., Durant, N. H., Norman, G. J., & Sallis, J. F. (2008). Where are youth active? Roles of proximity,active transport, and built environment. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 40, 2071–2079. [CrossRef]

- Kaczynski, A. T., & Henderson, K. A. (2007). Environmental correlates of physical activity: A review of evidence about parks and recreation. Leisure Sciences, 29, 315–354. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D. A., Marsh, T., Williamson, S., Derose, K. P., Martinez, H., Setodji, C., & McKenzie, T. L. (2010). Parks and physical activity:.

- Floyd, M. F., Spengler, J. O., Maddock, J. E., Gobster, P. H., &Suau, L. J. (2008). Park-based physical activity in diverse communities of two U.S. cities: An observational study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 34, 299–305. [CrossRef]

- Akpinar, A. (2016). How is quality of urban green spaces associated with physical activity and health? Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 16, 76–83. [CrossRef]

- Mowen, A. J., & Confer, J. J. (2003). The relationship between perceptions, distance, and socio-demographic characteristics upon public use of an urban park “In-Fill”. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 21, 58–74.

- Borumand, M., & Rezaee, S. (2014). Evaluating the performance of the parks of women in promoting the gender equality in cities case study: Madar Park of Women in Tehran 15th municipal district. Indian Journal of Scientific Research, 4, 280–290.

- Brorsson, A., Ohman, A., Lundberg, S., & Nygard, L. (2011). Accessibility in public space as perceived by people with Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia, 10, 587–602. [CrossRef]

- Kemperman, A. D. A. M., & Timmermans, H. J. P. (2006). Preferences, benefits, and park visits: A latent class segmentation analysis. Tourism Analysis, 11, 221–230. [CrossRef]

- Özgüner, H. (2011). Cultural differences in attitudes towards urban parks and green spaces. Landscape Research, 36, 599–620. [CrossRef]

- Koohsari, M. (2013). Public open space and walking: The role of proximity, perceptual qualities of the surrounding builtenvironment, and street configuration. Environment and Behavior, 45, 706–736. [CrossRef]

- Westley, T., Kaczynski, A. T., Stanis, S. A. W., & Besenyi, G. M. (2013). Parental neighborhood safety perceptions and their children’s health behaviors: Associations by child age, gender and household income. Children, Youth and Environment, 23, 118–147. [CrossRef]

- Park, K. (2017). Psychological park accessibility: a systematic literature review of perceptual components affecting park use. Landscape research, 42(5), 508-520.

- Reynolds, K. D., Wolch, J., Byrne, J., Chou, C.-P., Feng, G., Weaver, S., et al. (2007). Trail characteristics as correlates of urban trail use. American Journal of Health Promotion, 21(4s), 335L 345.

- Gobster, P. H. (1998). Urban parks as green walls or green magnets? Interracial rela- tions in neighborhood boundary parks. Landscape and Urban Planning, 41(1), 43–55.

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A., & Stieglitz, O. (2002). Children in Los Angeles parks: A study of equity, quality and children’s satisfaction with neighbourhood parks. The Town Planning Review, 73(4), 467–488. [CrossRef]

- Jim, C. Y., & Chen, W. Y. (2006). Recreation–amenity use and contingent valuation of urban greenspaces in Guangzhou, China. Landscape and urban planning, 75(1-2), 81-96.

- Fermino, R. C., Reis, R. S., Hallal, P. C., & de Farias Júnior, J. C. (2013). Perceived environment and public open space use: a study with adults from Curitiba, Brazil. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 10(35), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D., & Han, B. (2016). The paradox of parks in low-income areas park use and perceived threats. Environment and Behavior, 48, 230–245. [CrossRef]

- Wan, C., & Shen, G. (2015). Encouraging the use of urban green space: The mediating role of attitude, perceived usefulness and perceived behavioural control. Habitat International, 50, 130–139. [CrossRef]

- Tucker, P., Gilliland, J., & Irwin, J. D. (2007). Splashpads, swings, and shade: Parents’ preferences for neighbourhood parks. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 98, 198–202.

- Gehl, J., & Svarre, B. (2013). How to study public life. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Balogun, A. L., Adebisi, N., Abubakar, I. R., Dano, U. L., andTella, A. (2022). Digitalization for transformative urbanization, climate change adaptation, and sustainable farming in Africa: trend, opportunities, and challenges. Journal of Integrative Environmental Sciences, 19(1), 17-37.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).