Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

21 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

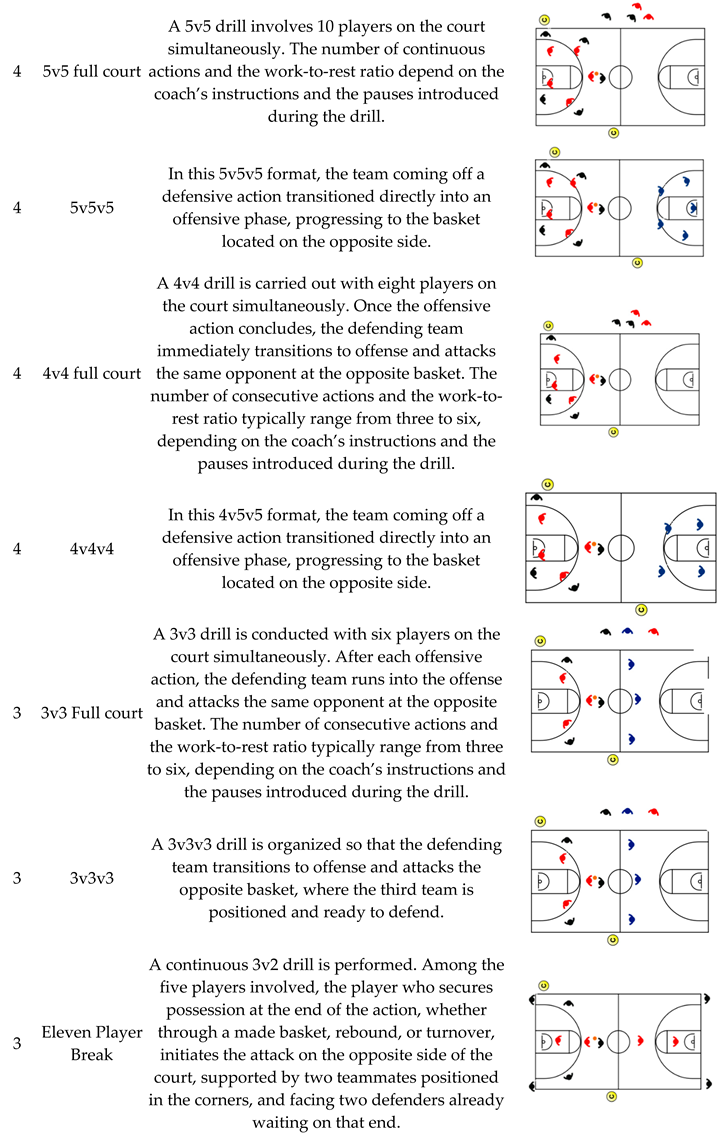

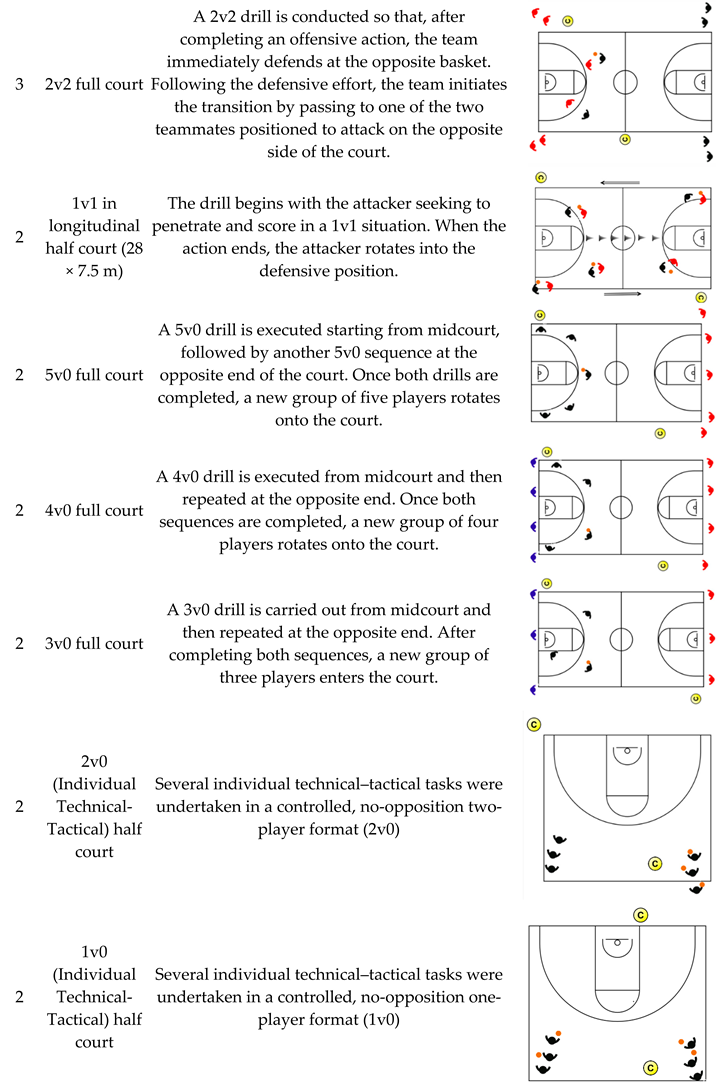

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Procedures

|

|

2.3. Physical Variables

2.3.1. Physiological Variables

2.3.2. Biomechanical Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

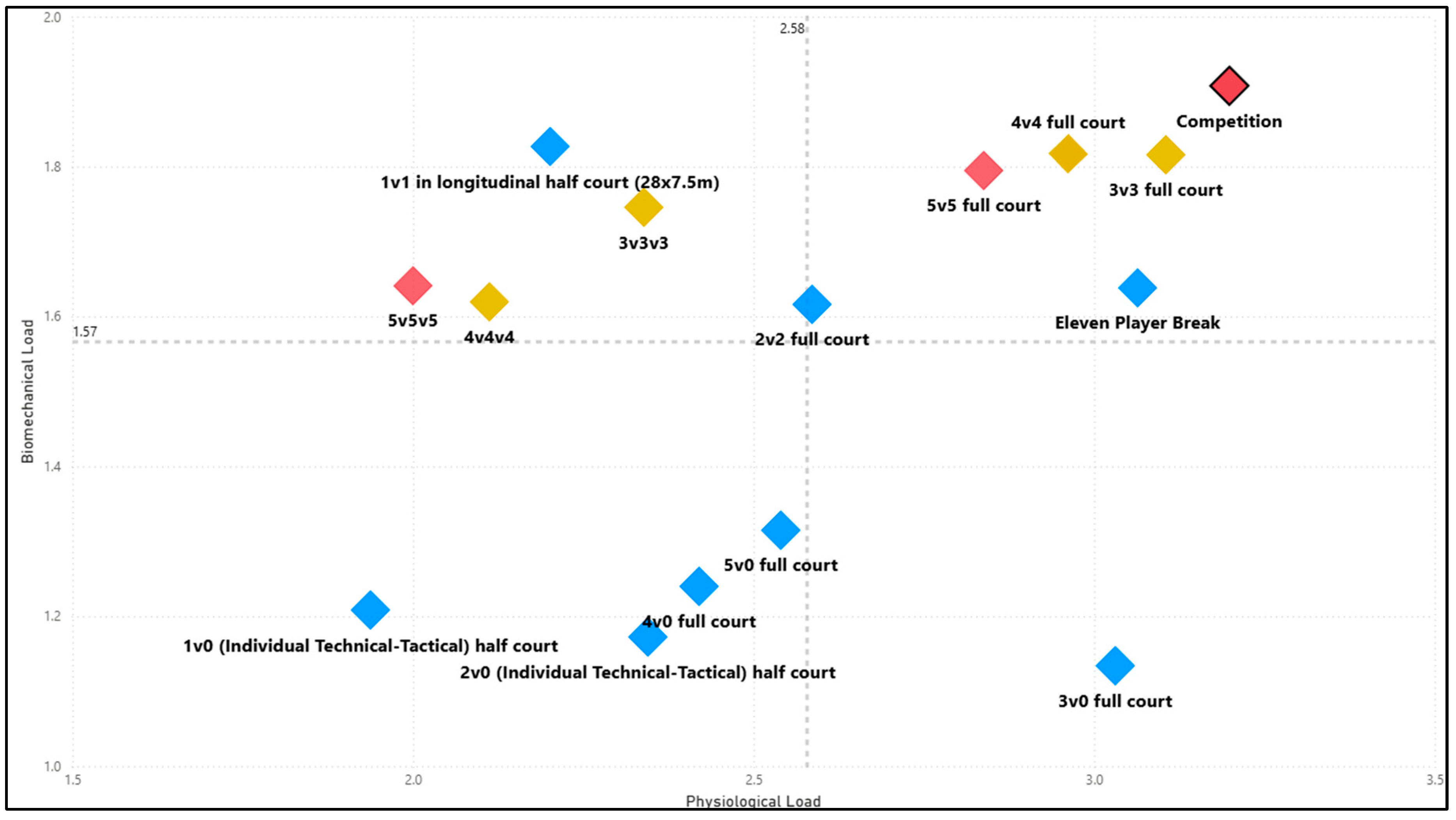

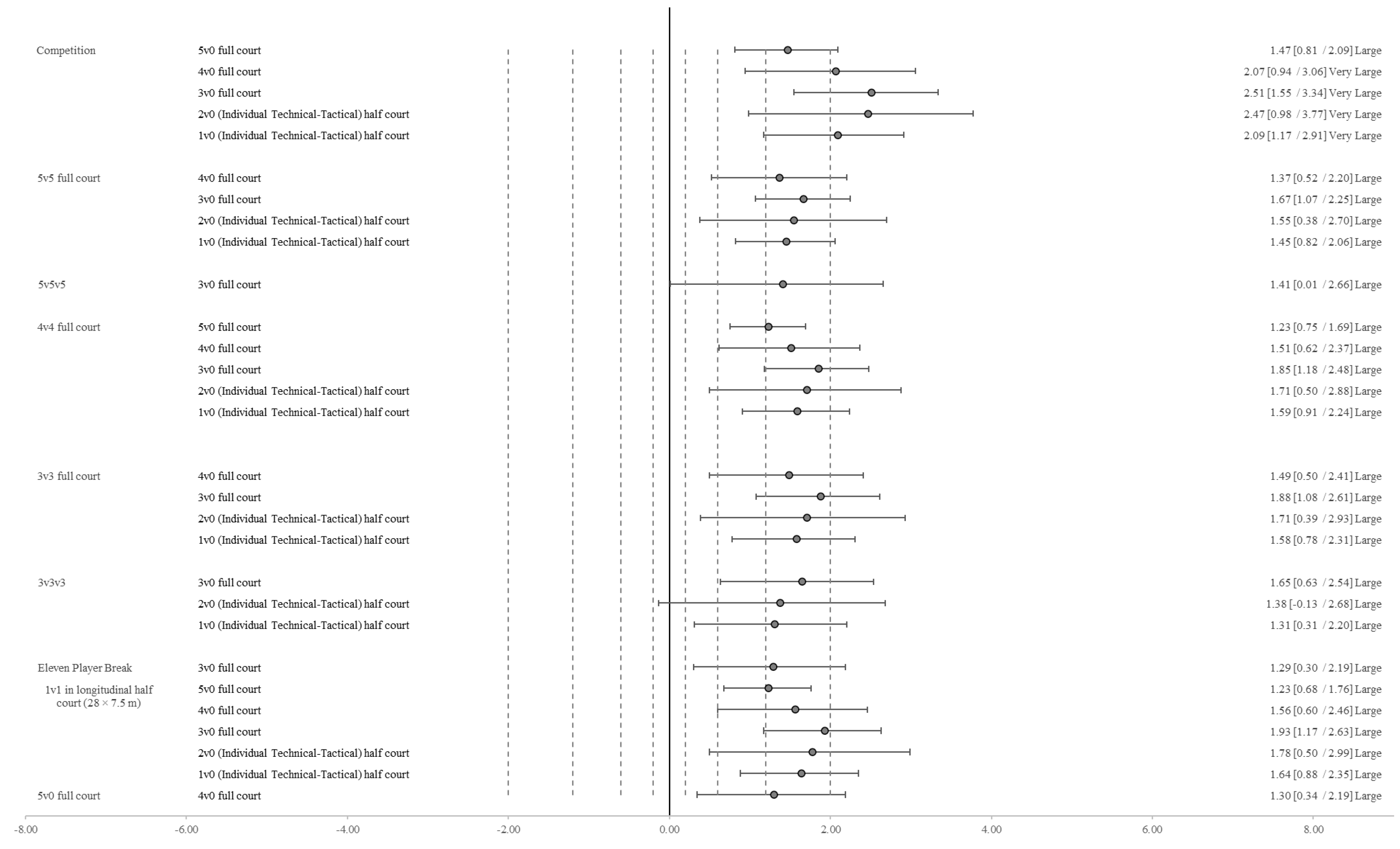

3. Results

4. Discussion

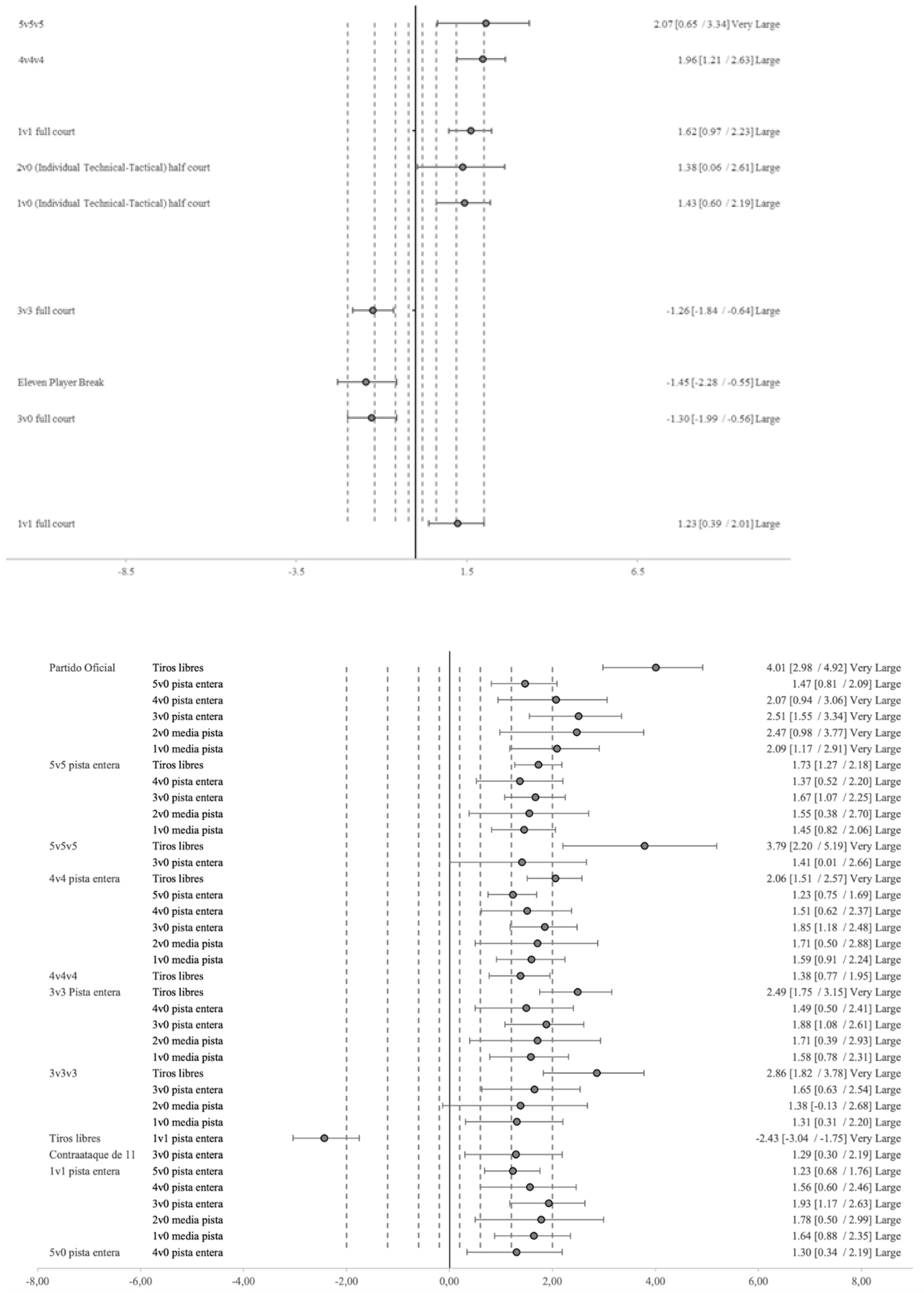

4.1. Considerably Inferior to Competitive Benchmarks Across Biomechanical and Physiological Dimensions

4.2. Progressing Toward Competitive Benchmarks Across Biomechanical and Physiological Dimensions

5. Conclusions

- Official competition consistently represents the most demanding context in both biomechanical and physiological load, exceeding all training tasks analyzed.

- Non-opposition drills (e.g., 1v0 to 5v0) show limited transferability to the physical demands of competition, suggesting they may be insufficient to replicate match intensity.

- Among the training formats, the 3v3 task most closely mirrors the physiological and biomechanical demands of official competition.

- 3v3 and 4v4 full-court tasks appear to be highly effective for eliciting elevated intensities, particularly in biomechanical load due to the high frequency of movements. These formats may be especially useful during training phases aimed at accumulating high external workload.

- In small-sided games with constrained space and continuous opposition (e.g., 3v3v3, 4v4v4, 5v5v5), physiological load is lower than in official matches, although biomechanical load remains comparable. This suggests these tasks may be well-suited for emphasizing technical-tactical development while minimizing excessive external load.

- Despite the greater overall load values observed in competition, a substantial portion of match time consists of low- or very low-intensity actions. This implies that decisive moments in competition are significantly more intense than what is typically elicited during training.

- The findings highlight the critical importance of players' abilities to accelerate, decelerate, change direction, and jump, as these actions underpin performance in basketball's high-intensity, intermittent context.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baker, J.; Côté, J.; Abernethy, B. Learning from the Experts: Practice Activities of Expert Decision Makers in Sport. Res Q Exerc Sport 2003, 74, 342–347. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D.C.; Wright, C. A Time-Motion Analysis of Professional Basketball to Determine the Relationship between Three Activity Profiles: High, Medium and Low Intensity and the Length of the Time Spent on Court. Int J Perform Anal Sport 2006, 6, 130–139. [CrossRef]

- Coyne, J.O.C.; Gregory Haff, G.; Coutts, A.J.; Newton, R.U.; Nimphius, S. The Current State of Subjective Training Load Monitoring—A Practical Perspective and Call to Action. Sports Med Open 2018, 4. [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, A.T.; Tucker, P.S.; Dascombe, B.J.; Berkelmans, D.M.; Hiskens, M.I.; Dalbo, V.J. Fluctuations in Activity Demands Across Game Quarters in Professional and Semiprofessional Male Basketball. J Strength Cond Res 2015, 29, 3006–3015. [CrossRef]

- Aschendorf, P.F.; Zinner, C.; Delextrat, A.; Engelmeyer, E.; Mester, J. Effects of Basketball-Specific High-Intensity Interval Training on Aerobic Performance and Physical Capacities in Youth Female Basketball Players. Physician and Sportsmedicine 2019, 47, 65–70. [CrossRef]

- Maggioni, M.A.; Bonato, M.; Stahn, A.; Torre, A. La; Agnello, L.; Vernillo, G.; Castagna, C.; Merati, G. Effects of Ball Drills and Repeated-Sprint-Ability Training in Basketball Players. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2019, 14, 757–764. [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, E.; Stojiljković, N.; Scanlan, A.T.; Dalbo, V.J.; Berkelmans, D.M.; Milanović, Z. The Activity Demands and Physiological Responses Encountered During Basketball Match-Play: A Systematic Review. Sports Medicine 2018, 48, 111–135.

- Matthew, D.; Delextrat, A. Heart Rate, Blood Lactate Concentration, and Time-Motion Analysis of Female Basketball Players during Competition. J Sports Sci 2009, 27, 813–821. [CrossRef]

- McInnes, S.E.; Carlson, J.S.; Jones, C.J.; McKenna, M.J. The Physiological Load Imposed on Basketball Players during Competition. J Sports Sci 1995, 13, 387–397. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.B.; Wright, A.A.; Dischiavi, S.L.; Townsend, M.A.; Marmon, A.R. Activity Demands During Multi-Directional Team Sports: A Systematic Review. Sports Medicine 2017, 47, 2533–2551.

- Doma, K.; Leicht, A.; Sinclair, W.; Schumann, M.; Damas, F.; Burt, D.; Woods, C. Impact of Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage on Performance Test Outcomes in Elite Female Basketball Players. J Strength Cond Res 2018, 32, 1731–1738. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, T.; Spiteri, T.; Piggott, B.; Bonhotal, J.; Haff, G.G.; Joyce, C. Monitoring and Managing Fatigue in Basketball. Sports 2018, 6.

- Scanlan, A.; Dascombe, B.; Reaburn, P. A Comparison of the Activity Demands of Elite and Sub-Elite Australian Men’s Basketball Competition. J Sports Sci 2011, 29, 1153–1160. [CrossRef]

- Sosa, C.; Alonso-Pérez-Chao, E.; Ribas, C.; Schelling, X.; Lorenzo, A. Description and Classification of Training Drills, Based on Biomechanical and Physiological Load, in Elite Basketball. Sensors 2025, 25. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, S.; Joyce, D. Evaluating Strategic Periodisation in Team Sport. J Sports Sci 2018, 36, 279–285. [CrossRef]

- Dawson, B.; Hopkinson, R.; Appleby, B.; Stewart, G.; Roberts, C. Comparison of Training Activities and Game Demands in the Australian Football League. J Sci Med Sport 2004, 7, 292–301. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.P.; Trewartha, G.; Higgitt, R.J.; El-Abd, J.; Stokes, K.A. The Physical Demands of Elite English Rugby Union. J Sports Sci 2008, 26, 825–833. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.J. A Framework for Understanding the Training Process Leading to Elite Performance; 2003; Vol. 33;.

- Champion, L.; Middleton, K.; MacMahon, C. Many Pieces to the Puzzle: A New Holistic Workload Approach to Designing Practice in Sports. Sports Med Open 2023, 9, 38. [CrossRef]

- Román, M.R.; García-Rubio, J.; Feu, S.; Ibáñez, S.J. Training and Competition Load Monitoring and Analysis of Women’s Amateur Basketball by Playing Position: Approach Study. Front Psychol 2019, 9. [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.L.; O’Grady, C.J.; Scanlan, A.T. Game Schedule Congestion Affects Weekly Workloads but Not Individual Game Demands in Semi-Professional Basketball. Biol Sport 2020, 37, 59–67. [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.L.; Scanlan, A.T.; Stanton, R.; Sargent, C. The Effect of Game-Related Contextual Factors on Sleep in Basketball Players The Role of Micro-Technologies for Monitoring Players in Basketball View Project A Comparison of Training and Competition Demands in Semi-Professional Male Basketball Players View Project; 2020;

- Fox, J.L.; Stanton, R.; Scanlan, A.T. A Comparison of Training and Competition Demands in Semiprofessional Male Basketball Players. Res Q Exerc Sport 2018, 89, 103–111. [CrossRef]

- Svilar, L.; Castellano, J.; Jukic, I. Comparison of 5vs5 Training Games and Match-Play Using Microsensor Technology in Elite Basketball. J Strength Cond Res 2019, 33, 1897–1903. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Ronda, L.; Ric, A.; Llabres-Torres, I.; de las Heras, B.; Schelling i del Alcazar, X. Position-Dependent Cardiovascular Response and Time-Motion Analysis During Training Drills and Friendly Matches in Elite Male Basketball Players. J Strength Cond Res 2016, 30, 60–70. [CrossRef]

- Brandão, F.M.; Junior, D.B.R.; da Cunha, V.F.; Meireles, G.B.; Filho, M.G.B. Differences between Training and Game Loads in Young Basketball Players. Revista Brasileira de Cineantropometria e Desempenho Humano 2019, 21. [CrossRef]

- Conte, D.; Kolb, N.; Scanlan, A.T.; Santolamazza, F. Monitoring Training Load and Well-Being during the in-Season Phase in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division i Men’s Basketball. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2018, 13, 1067–1074. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, K.D.; Quiggle, G.T. Tensiomyographical Responses to Accelerometer Loads in Female Collegiate Basketball Players. J Sports Sci 2017, 35, 2334–2341. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, K.J.; Allen, S. V.; McGuigan, M.R.; Whatman, C.S. The Relationship between Training Load and Injury in Men’s Professional Basketball. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2017, 12, 1238–1242. [CrossRef]

- Piedra, A.; Peña, J.; Ciavattini, V.; Caparrós, T. Relationship between Injury Risk, Workload, and Rate of Perceived Exertion in Professional Women’s Basketball. Apunts Sports Medicine 2020, 55, 71–79. [CrossRef]

- Caparrós, T.; Casals, M.; Solana, Á.; Peña, J. External Workloads Are Related to Higher Injury Risk in Professional Male Basketball Games; 2018; Vol. 17;.

- Ferioli, D.; La Torre, A.; Tibiletti, E.; Dotto, A.; Rampinini, E. Determining the Relationship between Load Markers and Non-Contact Injuries during the Competitive Season among Professional and Semi-Professional Basketball Players. Research in Sports Medicine 2021, 29, 265–276. [CrossRef]

- Sosa Marín, C.; Alonso-Pérez-Chao, E.; Schelling, X.; Lorenzo, A. How to Optimize Training Design? A Narrative Review of Load Modulators in Basketball Drills. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2025, 15.

- Sansone, P.; Gasperi, L.; Makivic, B.; Gomez-Ruano, M.; Tessitore, A.; Conte, D. An Ecological Investigation of Average and Peak External Load Intensities of Basketball Skills and Game-Based Training Drills. Biol Sport 2023, 40, 649–656. [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.L.; McLean, B.D.; Impellizzeri, F.M.; Strack, D.S.; Coutts, A.J. Measuring Physical Demands in Basketball: An Explorative Systematic Review of Practices. Sports Medicine 2021, 51, 81–112.

- Vanrenterghem, J.; Nedergaard, N.J.; Robinson, M.A.; Drust, B. Training Load Monitoring in Team Sports: A Novel Framework Separating Physiological and Biomechanical Load-Adaptation Pathways. Sports Medicine 2017, 47, 2135–2142. [CrossRef]

- McKay, A.K.A.; Stellingwerff, T.; Smith, E.S.; Martin, D.T.; Mujika, I.; Goosey-Tolfrey, V.L.; Sheppard, J.; Burke, L.M. Defining Training and Performance Caliber: A Participant Classification Framework. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2022, 17, 317–331. [CrossRef]

- Harriss, D.J.; Atkinson, G. Ethical Standards in Sport and Exercise Science Research: 2014 Update. International Journal Sports Medicine 2014, 34, 1025–1029.

- Hodder, R.W.; Ball, K.A.; Serpiello, F.R. Criterion Validity of Catapult Clearsky T6 Local Positioning System for Measuring Inter-Unit Distance. Sensors 2020, 20, 3693. [CrossRef]

- Luteberget, L.; Spencer, M.; Gilgien, M. Validity of the Catapult ClearSky T6 Local Positioning System for Team Sports Specific Drills, in Indoor Conditions. Front Physiol 2018, 9, 115. [CrossRef]

- Serpiello, F.R.; Hopkins, W.G.; Barnes, S.; Tavrou, J.; Duthie, G.M.; Aughey, R.J.; Ball, K. Validity of an Ultra-Wideband Local Positioning System to Measure Locomotion in Indoor Sports. J Sports Sci 2018, 36, 1727–1733.

- Hoppe, M.W.; Baumgart, C.; Polglaze, T.; Freiwald, J. Validity and Reliability of GPS and LPS for Measuring Distances Covered and Sprint Mechanical Properties in Team Sports. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0192708.

- Luteberget, L.; Holme, B.; Spencer, M. Reliability of Wearable Inertial Measurement Units to Measure Physical Activity in Team Handball. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2017, 13, 467–473. [CrossRef]

- Castellano, J.; Casamichana, D.; Calleja-González, J.; Román, J.S.; Ostojic, S. Reliability and Accuracy of 10 Hz GPS Devices for Short-Distance Exercise. J Sports Sci Med 2011, 10, 233–234.

- Schelling, X.; Torres, L. Accelerometer Load Profiles for Basketball-Specific Drills in Elite Players. J Sports Sci Med 2016, 15, 585–591.

- Coyne, J.O.C.; Gregory Haff, G.; Coutts, A.J.; Newton, R.U.; Nimphius, S. The Current State of Subjective Training Load Monitoring—a Practical Perspective and Call to Action. Sports Med Open 2018, 4, 58. [CrossRef]

- Vanrenterghem, J.; Nedergaard, N.J.; Robinson, M.A.; Drust, B. Training Load Monitoring in Team Sports: A Novel Framework Separating Physiological and Biomechanical Load-Adaptation Pathways. Sports Medicine 2017, 47, 2135–2142. [CrossRef]

- Sosa, C.; Lorenzo, A.; Trapero, J.; Ribas, C.; Alonso, E.; Jimenez, S.L. Specific Absolute Velocity Thresholds during Male Basketball Games Using Local Positional System; Differences between Age Categories. Applied Sciences 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Alonso Perez-Chao, E.; Lorenzo, A.; Scanlan, A.; Lisboa, P.; Sosa, C.; Gómez, M.A. Higher Playing Times Accumulated Across Entire Games and Prior to Intense Passages Reduce the Peak Demands Reached by Elite, Junior, Male Basketball Players. Am J Mens Health 2021, “in press,”. [CrossRef]

- Svilar, L.; Castellano, J.; Jukic, I. Load Monitoring System in Top-Level Basketball Team: Relationship between External and Internal Training Load. Kinesiology 2018, 50, 25–33. [CrossRef]

- Alonso Pérez-Chao, E.; Gómez, M.Á.; Lisboa, P.; Trapero, J.; Jiménez, S.L.; Lorenzo, A. Fluctuations in External Peak Demands across Quarters during Basketball Games. Front Psychol 2022, “in press,”. [CrossRef]

- Alonso, E.; Miranda, N.; Zhang, S.; Sosa, C.; Trapero, J.; Lorenzo, J.; Lorenzo, A. Peak Match Demands in Young Basketball Players: Approach and Applications. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 2256. [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, William.; Marshall, Stephen.; Batterham, Alan.; Hanin, J. Progressive Statistics for Studies in Sports Medicine and Exercise Science. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009, 41, 3–12. [CrossRef]

- Reina, M.; García-Rubio, J.; Pino-Ortega, J.; Ibáñez, S.J. The Acceleration and Deceleration Profiles of U-18 Women’s Basketball Players during Competitive Matches. Sports 2019, 7. [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.N.C.; Dalbo, V.J.; Fox, J.L.; O’Grady, C.J.; Scanlan, A.T. Comparing Weekly Training and Game Demands According to Playing Position in a Semiprofessional Basketball Team. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2021, 16, 772–778. [CrossRef]

- Brandão, F.M.; Ribeiro Junior, D.B.; Cunha, V.F. da; Meireles, G.B.; Bara Filho, M.G. Differences between Training and Game Loads in Young Basketball Players. Revista Brasileira de Cineantropometria & Desempenho Humano 2019, 21. [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.L.; Stanton, R.; O’grady, C.J. Are Acute Player Workloads Associated with In-Game Performance in Basketball?;

- Sosa, C.; Lorenzo, A.; Trapero, J.; Ribas, C.; Alonso, E.; Jimenez, S.L. Specific Absolute Velocity Thresholds during Male Basketball Games Using Local Positional System; Differences between Age Categories. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.N.C.; Fox, J.L.; O’Grady, C.J.; Gardner, S.; Dalbo, V.J.; Scanlan, A.T. Weekly Training Demands Increase, but Game Demands Remain Consistent Across Early, Middle, and Late Phases of the Regular Season in Semiprofessional Basketball Players. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2022, 17, 350–357. [CrossRef]

- Sosa, C.; Lorenzo, A.; Trapero, J.; Ribas, C.; Alonso, E.; Jimenez, S.L. Specific Absolute Velocity Thresholds during Male Basketball Games Using Local Positional System; Differences between Age Categories. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 4390. [CrossRef]

- Sosa, C.; Alonso-Pérez-Chao, E.; Ribas, C.; Schelling, X.; Lorenzo, A. Description and Classification of Training Drills, Based on Biomechanical and Physiological Load, in Elite Basketball. Sensors 2025, 25. [CrossRef]

- Bredt, S.D.G.T.; Chagas, M.H.; Peixoto, G.H.; Menzel, H.J.; Andrade, A.G.P. De Understanding Player Load: Meanings and Limitations. J Hum Kinet 2020, 71, 5–9. [CrossRef]

- Heishman, A.D.; Daub, B.D.; Miller, R.M.; Freitas, E.D.S.; Bemben, M.G. External Training Loads and Neuromuscular Performance for Division I Basketball Players over the Preseason; 2020; Vol. 19;.

- Montgomery, P.G.; Pyne, D.B.; Minahan, C.L. The Physical and Physiological Demands of Basketball Training and Competition; 2010; Vol. 5;.

- Feu, S.; García-Ceberino, J.M.; López-Sierra, P.; Ibáñez, S.J. Training to Compete: Are Basketball Training Loads Similar to Competition Achieved? Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 12512. [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, J.; Abrantes, C.; Leite, N. POWER, HEART RATE AND PERCEIVED EXERTION RESPONSES TO 3X3 AND 4X4 BASKETBALL SMALL-SIDED GAMES. Revista de Psicología del Deporte 2009, 18, 463–467.

- Piedra, A.; Caparrós, T.; Vicens-Bordas, J.; Peña, J. Internal and External Load Control in Team Sports through a Multivariable Model. J Sports Sci Med 2021, 20, 751–758. [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Guerrero, J.; Reche, X.; Cos, F.; Casamichana, D.; Sampaio, J. Changes in External Load When Modifying Rules of 5-on-5 Scrimmage Situations in Elite Basketball. J Strength Cond Res 2018, 00, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Svilar, L.; Castellano, J.; Jukic, I. Comparison of 5vs5 Training Games and Match-Play Using Microsensor Technology in Elite Basketball. J Strength Cond Res 2019, 33, 1897–1903. [CrossRef]

- Mccormick, B.T.; Hannon, J.C.; Newton, M.; Shultz, B.; Miller, N.; Young, W.; Arias, J.; Jenkins, D. Comparison of Physical Activity in Small-Sided Basketball Games Versus Full-Sided Games; 2012; Vol. 7;.

- Torres-Ronda, L.; Ric, A.; Llabres-Torres, I.; de Las Heras, B.; Schelling I Del Alcazar, X. Position-Dependent Cardiovascular Response and Time-Motion Analysis During Training Drills and Friendly Matches in Elite Male Basketball Players. J Strength Cond Res 2016, 30, 60–70. [CrossRef]

- Dupont, G.; Akakpo, K.; Berthoin, S. The Effect of In-Season, High-Intensity Interval Training in Soccer Players. J Strength Cond Res 2004, 18, 584–589. [CrossRef]

- Clark, N.A.; Edwards, A.M.; Morton, R.H.; Butterly, R.J. Season-to-Season Variations of Physiological Fitness Within a Squad of Professional Male Soccer Players. J Sports Sci Med 2008, 7, 157–165.

- Torres-Ronda, L.; Ric, A.; Llabres-Torres, I.; de Las Heras, B.; Schelling I Del Alcazar, X. Position-Dependent Cardiovascular Response and Time-Motion Analysis During Training Drills and Friendly Matches in Elite Male Basketball Players. J Strength Cond Res 2016, 30, 60–70. [CrossRef]

- Ben Abdelkrim, N.; Castagna, C.; Jabri, I.; Battikh, T.; El Fazaa, S.; Ati, J. El Activity Profile and Physiological Requirements of Junior Elite Basketball Players in Relation to Aerobic-Anaerobic Fitness. J Strength Cond Res 2010, 24, 2330–2342. [CrossRef]

- Narazaki, K.; Berg, K.; Stergiou, N.; Chen, B. Physiological Demands of Competitive Basketball. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2009, 19, 425–432. [CrossRef]

- O’grady, C.J.; Dalbo, V.J.; Teramoto, M.; Fox, J.L.; Scanlan, A.T. External Workload Can Be Anticipated during 5 vs. 5 Games-Based Drills in Basketball Players: An Exploratory Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17. [CrossRef]

- Schelling, X.; Torres, L. Accelerometer Load Profiles for Basketball-Specific Drills in Elite Players; 2016; Vol. 15;.

- Malone, S.; Owen, A.; Newton, M.; Mendes, B.; Collins, K.D.; Gabbett, T.J. The Acute:Chonic Workload Ratio in Relation to Injury Risk in Professional Soccer. J Sci Med Sport 2017, 20, 561–565. [CrossRef]

- Narazaki, K.; Berg, K.; Stergiou, N.; Chen, B. Physiological Demands of Competitive Basketball. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2009, 19, 425–432. [CrossRef]

- Weaving, D.; Jones, B.; Till, K.; Abt, G.; Beggs, C. The Case for Adopting a Multivariate Approach to Optimize Training Load Quantification in Team Sports. Front Physiol 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Absolute Average | Relative Time Average (per Minute) | Peak Demand Relative to Time (per Minute) in a 1-Minute Window |

| PL | 240-423 ua | 6-10 ua/min | 18.45-19.92 ua/min |

| Distance | 3209 m – 3325 m (LPS) 4404 m -7558 m (TMA) |

70-95 m/min 93.1 – 133.1 m/min |

120-144 m/min X |

| Distance <7 Km/h | 1259 m -1455 m (LPS) 404 m – 1838 m (TMA) |

X | X |

| Distance 7-14 Km/h | 1122.72 m – 1199.01 m (LPS) 1424 m - 2208 m (TMA) |

X | X |

| Distance 14-18 Km/h | 483.89 m – 451.78 (LPS) 928 m – 2845 m (TMA) |

X | X |

| Distance >18 Km/h | 139.83 m – 195.29 m (LPS) 70 m – 1096 m (TMA) |

2-4 m/min X |

20-30 m/min X |

| Accelerations | 100-140 | 2.5-4.2 n/min | 6.4-9.2 n/min |

| Decelerations | 84-124 | 2.1-3.1 n/min | 6.3-8.4 n/min |

| Jumps | 32-52 | 1.1-1.6 n/min | X |

| Activity change (frequency) | 1-3 sg | X | X |

| Lactate concentration | 2.7-6.8 mmol/L-1 | X | X |

| HR Max | 170 – 198 lpm | X | X |

| HR Avg | 136-158 lpm | X | X |

| % time <85% HR Max | 19.6 - 35% | X | X |

| % time >85% HR Max | 80.4 – 65 % | X | X |

| Variables | Physiological Load | |||

| Low | Medium | High | Very High | |

| Distance per minute (m) | 18.56 | 62.09 | 75.28 | 80.50 |

| Standing–walking (<7 km·h−1) | 15.53 | 31.75 | 65.40 | 34.35 |

| Jogging (7–14 km·h−1) | 3.13 | 21.36 | 51.81 | 28.05 |

| Running (14.01–18 km·h−1) | 0.85 | 6.37 | 17.32 | 12.29 |

| High-speed running (>18 km·h−1) | 0.22 | 2.42 | 3.77 | 6.02 |

| Sample size (N) | 141 | 1831 | 122 | 1042 |

| Sample proportion (%) | 4.5% | 58.4% | 3.9% | 32.2% |

| Bayesian information criterion (BIC) | 9214.44 | |||

| Average silhouette | 0.5 | |||

| Variables | Biomechanical Load | |

| Low | High | |

| Accelerations per minute | 1.35 | 2.71 |

| Decelerations per minute | 1.20 | 3.38 |

| Explosive efforts per minute | 1.56 | 3.26 |

| PlayerLoad per minute | 5.91 | 8.42 |

| Jumps per minute | 0.65 | 0.73 |

| Sample size (N) | 128 | 2124 |

| Sample proportion (%) | 47.4% | 67.7% |

| Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) | 10,677.49 | |

| Average silhouette | 0.5 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).