1. Introduction

Elite volleyball athletes face intense physical demands, performing repeated high-intensity movements like jumps, sprints, and rapid changes in direction throughout a long and grueling season [

1]. Optimizing training is crucial for maximizing performance and minimizing injury risk [

2]. This requires careful management of training load, encompassing both external loads, the measurable physical demands placed on the athlete (e.g., jump height, distance covered), and internal load, the individual psychophysiological response to those demands (e.g., perceived exertion, heart rate) [

3].

The ability to jump high is a critical determinant of success in volleyball, influencing actions such as serving, attacking, and blocking [

4,

5]. However, the repetitive nature of these high-intensity movements can lead to fatigue, potentially impairing performance and increasing the risk of injury [

6]. Effective training programs must carefully balance the application of training stimuli with adequate recovery to mitigate these risks [

7].

Monitoring both EL and IL provides valuable insights into an athlete's training status and readiness [

3]. Recent research has explored EL and IL in elite male volleyball, examining training session characteristics [

8,

9], weekly load distribution [

10,

11,

12], and seasonal variations [

13,

14,

15], using methods such as rate of perceived exertion (RPE) and jump count as the most commonly used [

16,

17]. These studies have revealed a correlation between increased TL and poorer recovery, well-being, and a heightened risk of injury [

11,

14,

18]. Furthermore, EL varies among players depending on their specific roles and the associated movement demands [

15,

19].

Despite growing interest in TL monitoring, there remains considerable debate regarding the relationship between EL and IL [

8,

20,

21], likely due to variations in experimental designs and participant characteristics across studies. The complex interplay of exercise structure, training objectives, session types, and the distribution of stimuli and recovery further complicates this relationship. Moreover, there is a limited understanding of how accumulated TL acutely and chronically affects performance, and how TL fluctuations relative to game day impact athletes.

This study investigates the acute and chronic effects of IL and EL on neuromuscular performance and recovery status in elite male volleyball athletes at two distinct points in the season. We aim to address the current knowledge gap by examining how these factors influence performance in vertical jumps and multidirectional movements, key determinants of success in modern volleyball. Furthermore, we will analyze the relationship between EL and IL to provide practical insights for optimizing training programs and enhancing athletic performance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

The sample consisted of 14 male elite volleyball athletes from the same team competing in Brazil’s 1st division. Participants were non-randomly selected based on convenience, considering their acceptance and availability. Athletes (22.35 ± 4.14 years; 194 ± 9 cm; 89.15 ± 7.89 kg; 23.81 ± 2.16% body fat; 41.2 ± 5.62 cm CMJ) signed an informed consent form (ICF) after receiving verbal and written explanations about the study's risks, benefits, and procedures. This observational research was approved by the São Paulo University Research Ethics Committee (protocol: 23926919.9.0000.5659).

2.2. Study Design

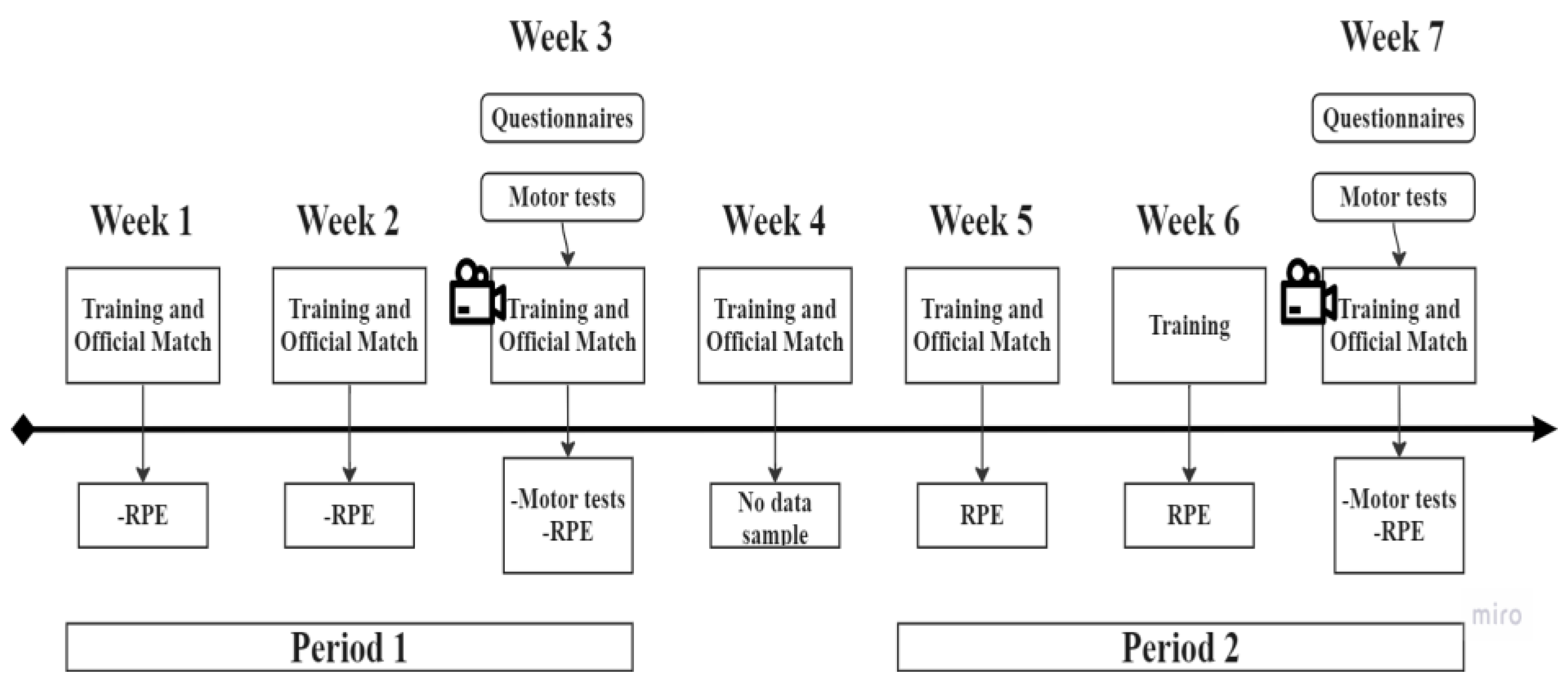

The study monitored the second part of the competitive season, following the year-end break. The design comprised two 3-week periods (Period 1 [P1] and Period 2 [P2]), separated by a 1-week break, totaling 7 weeks. During this time, 53 training sessions (physical, technical, tactical, technical-tactical, and simulated games) and 6 official matches were conducted. Internal Load (IL) was monitored across P1 and P2. Additional analyses, including External Load (EL), motor tests (pre- and post-training), and recovery/well-being questionnaires, were performed during weeks 3 and 7. These analyses spanned three consecutive days (Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday) in each respective week. Three athletes withdrew for personal reasons, resulting in a final sample size of 11 participants.

2.3. Body Composition

Body composition was assessed using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) with a GE Lunar iDXA device (GE Healthcare, Madison, WI, USA) and Encore 2011 software (version 13.6). Total body mass, lean mass, and fat mass were measured to characterize the sample. All assessments were conducted by the same technician to ensure consistency, with the equipment calibrated before each session.

2.4. Internal Load

Internal Load (IL) was quantified using Foster’s perceived exertion method (Borg CR-10 scale). Thirty minutes after each session, athletes rated their effort using the question: “How was your training?” IL metrics were calculated as follows:

Session Load (sRPE): RPE × session duration (minutes).

Daily Training Load (TL): Sum of all sRPE values for a day.

Period Training Load (PTL): Sum of TL values across a period.

Total Weekly Training Load (TWTL): Sum of TL values across a week.

Monotony (Mnt): Weekly load average ÷ standard deviation (SD).

Strain: TWTL × monotony.

Results were expressed in Arbitrary Units (AU).

2.5. External Load

External Load (EL) was quantified by counting jumps during training. Sessions were filmed using a GoPro Hero 5 camera (GoPro Inc., USA) positioned behind the court, ensuring an unobstructed view of the athletes. Jumps were classified based on their context (e.g., attacking, blocking, serving). An experienced evaluator performed the analysis, with reliability confirmed by a second evaluator. A randomly selected session (18% of total footage) demonstrated excellent inter- and intra-rater agreement (ICC = 0.99).

2.6. Motor Tests

Motor performance was assessed through vertical jump (CMJ) and agility tests conducted pre- and post-training. Athletes performed a standardized warm-up (flexibility exercises, multidirectional movements, and jumps) before testing. Each test was performed three times per session, and the average score was used for analysis [

22].

Vertical Jump: CMJ height was measured using the Jump System Pro contact mat (Cefise, Nova Odessa, Brazil) based on Bosco’s protocol.

Agility: The Pro Agility Test involved running specific distances and touching markers. Times were recorded using a Vollo VL1809 hand stopwatch (1/100-second accuracy).

Data collection followed established protocols for CMJ [

23] and agility [

24].

2.7. Questionnaires

To evaluate recovery status and subjective perception of fatigue, athletes completed two questionnaires daily before the first training session during test weeks. Responses were collected via Google Forms (Google©, USA).

Well-Being Scale (WB): This scale assessed five dimensions: overall fatigue, sleep quality, general muscle pain, mood, and stress levels. Athletes rated each item on a scale from 1 (worst perception) to 5 (best perception), based on their current condition at the time of response [

25]. The overall well-being index was calculated as the sum of the scores across all dimensions, providing a comprehensive measure of athlete well-being.

Total Quality Recovery (TQR): This visual analog scale evaluated the athletes' subjective perception of recovery. Scores ranged from 6 (very poorly recovered) to 20 (very well recovered) [

26]. The athletes selected a single value corresponding to their recovery status, which was directly used for data analysis.

This standardized approach ensured consistent and reliable insights into the athletes' recovery and fatigue levels throughout the study.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Periods 1 and 2

The data for periods 1 and 2 are presented in

Table 1. Statistical tests revealed significant differences in IL parameters between P1 and P2 (p < 0.05) and between weeks (p < 0.01). Post hoc analyses showed that RPE, TWTL, monotony (Mnt), and strain were higher in P1 compared to P2 (p < 0.05).

Within P1, there were no significant differences in PSE across weeks. However, TWTL and strain were higher in week 1 compared to week 2 (p < 0.01), while Mnt was lower in week 2 (p < 0.02). In P2, significant differences were found for RPE and Mnt in week 2 (p < 0.01), and TWTL and strain were higher in week 1 compared to weeks 2 and 3 (p < 0.01). Additionally, TWTL and strain in week 2 were lower than in week 3 (p < 0.01).

Pairwise week analysis indicated significant differences in TWTL (p < 0.05) and strain (p < 0.01) between weeks 1 and 2, Mnt between weeks 1, 2 (p < 0.01), and 3 (p = 0.02), and RPE in week 2 (p < 0.01).

3.2. Analysis of Test Weeks Results

Data for Test Weeks 1 and 2 are shown in

Table 2. In P1, PTL, average load, Mnt, and strain were significantly higher than in P2 (p < 0.01). Within-week comparisons in P1 revealed significant differences in RPE, sRPE, TL, and the number of jumps on paired days (p < 0.01).

During Test Week 1, TL for D1.1 was higher than D2.1 (p < 0.01). RPE for court training on D2.1 was higher compared to D1.1 (p < 0.02) and D3.1 (p < 0.01), while sRPE was lower on D3.1 (p < 0.01) and D2.1 (p = 0.05) compared to D1.1. The number of jumps and frequency of jumps were significantly higher on D1.1 (p < 0.01) and lower on D2.1 (p < 0.01) compared to D3.1.

During Test Week 2, TL was higher on D2.2 compared to other days (p < 0.01). RPE and sRPE for D1.2 were lower compared to D3.2 and D2.2 (p < 0.05). There were no differences in the number and frequency of jumps within the week.

Paired day comparisons between weeks revealed significant differences in RPE for D2 and D3 (D2.1 vs. D2.2 and D3.1 vs. D3.2) (p < 0.01). For sRPE, significant differences were observed in D1 (p < 0.02), D2, and D3 (p < 0.01). Differences were also found in CT for D1, D2, and D3 (p < 0.01) and in the number of jumps for D1 and D2 (p < 0.01).

3.3. Analysis of the Training Effect on Motor Performance

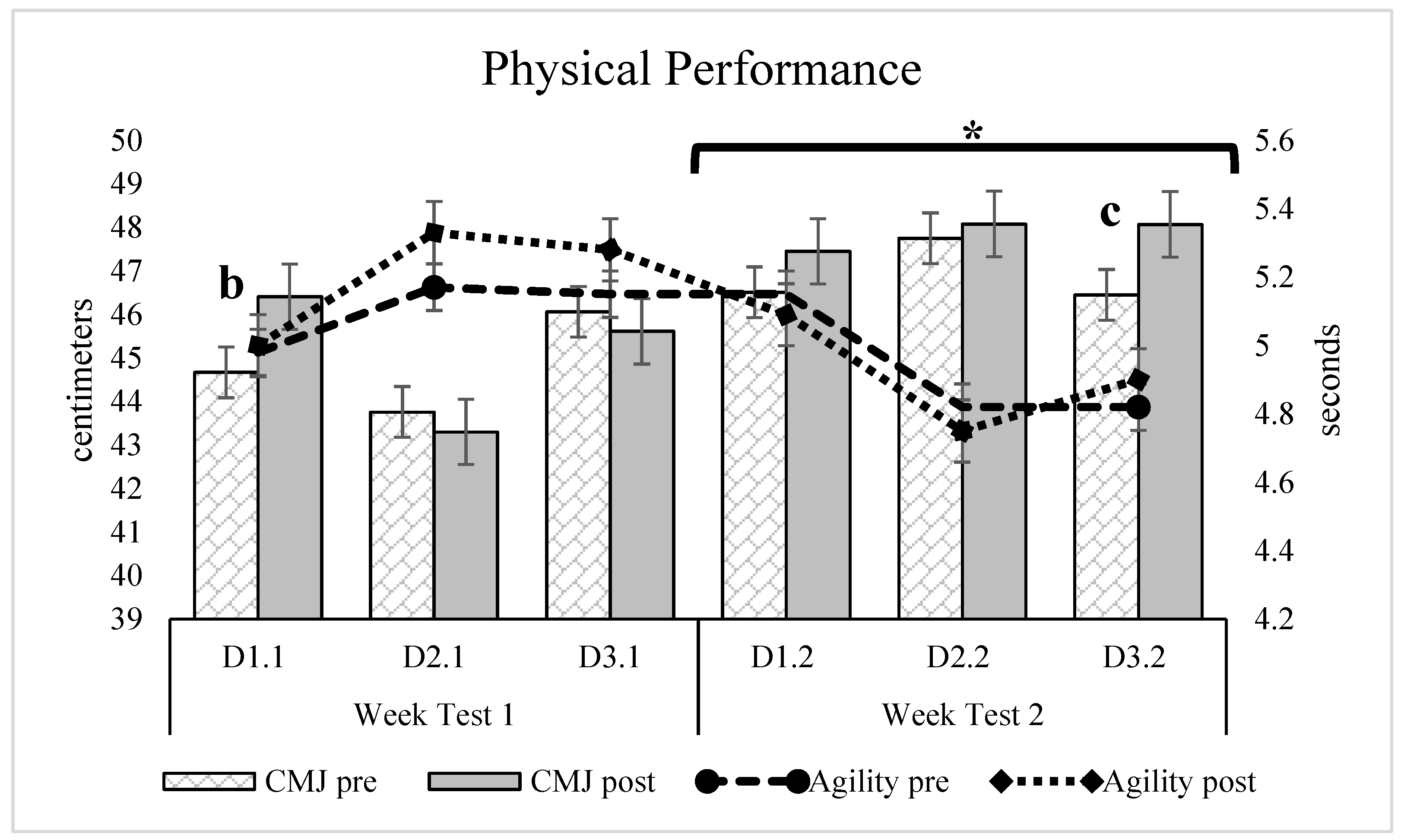

Table 3 summarizes motor performance data. Differences in performance were observed between periods, with week 7 (P2) showing better vertical jump (CMJ) height (p < 0.01) and agility (p < 0.02).

Within-week comparisons in week 3 revealed better CMJ performance on D1.1 compared to D2.1 (p < 0.05) and better agility on D1.1 compared to D2.1 and D3.1 (p < 0.01). In week 7, agility performance was worse on D1.2 compared to D2.2 and D3.2 (p < 0.001), with no differences in CMJ. Paired day comparisons showed differences in CMJ for D2 (p < 0.001) and agility for D2 and D3 (p < 0.001).

A training effect (p < 0.03) was identified for CMJ performance on D1.1 (p < 0.01) and D3.2 (p < 0.04), but no effect was observed for agility performance.

Graphic 1.

Analysis of the acute and chronic effect of training load on athletes’ motor performance (mean ± SE). * = difference to week test 1 (p < 0.02), b = difference between moments (pre x post) (p < 0.01), c = difference between moments (pre x post) (p < 0.05).

Graphic 1.

Analysis of the acute and chronic effect of training load on athletes’ motor performance (mean ± SE). * = difference to week test 1 (p < 0.02), b = difference between moments (pre x post) (p < 0.01), c = difference between moments (pre x post) (p < 0.05).

3.4. Correlations

Correlation analysis excluded libero players due to the low number of jumps performed. No significant correlation was found between the number of jumps and RPE or sRPE. A moderate correlation was observed between session duration and sRPE (r = 0.59; p < 0.01), TQR and WB scales with RPE (r = -0.47 and -0.40, p < 0.01), sRPE (r = -0.45 and -0.50, p < 0.01), and between TQR and WB (r = 0.53; p < 0.01).

The number of jumps on D1.1 showed a moderate correlation with WB on the following day (D2.1) (r = -0.67, p < 0.05). Weak correlations were found between CMJ and agility performance (r = 0.30; p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

This study analyzed the acute and chronic effects of training load on the motor performance of professional volleyball athletes, as well as the relationship between external load (EL) and internal load (IL). The main findings indicate that the training sessions analyzed did not acutely impair motor performance. On the contrary, the number and frequency of vertical jumps performed by the athletes contributed to improved jump height in some sessions. As a chronic effect, it was observed that periods of high training loads or significant load reductions influenced motor performance, particularly in terms of vertical jump height and agility.

Although no correlation was found between the number of jumps performed and the perceived IL of the athletes, IL was more closely related to the duration of the training session. Previous studies have indicated that intense training sessions may lead to energy depletion and intramuscular metabolite accumulation, resulting in expected performance reductions [

27]. However, in this study, the recovery interval between stimuli (~30s) appeared sufficient to maintain motor performance, as corroborated by Guan et al. [

28] and Carroll et al. [

29].

The results showed that the significant number of jumps performed on D1.1 negatively impacted the recovery status reported by the athletes, affecting vertical jump performance on D2.1 and agility performance on D2.1 and D3.1. This residual fatigue effect was observed for at least 24 hours in vertical jump performance and 48 hours in agility. Previous studies, such as that of Thomas et al. [

2], also indicated that intense stimuli like jumps or sprints could reduce neuromuscular function for similar periods.

Despite this, the positive results in vertical jump performance on D1.1 and D3.2 suggest an effect of post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE). The high frequency of jumps and maintenance of performance may be related to the athletes' adaptation to daily intense training, which promotes resistance to muscular fatigue and improvements in the stretch-shortening cycle [

30]. Factors such as increased muscle temperature, enhanced blood flow, and higher firing frequency of alpha motor neurons may also contribute to improved performance [

31,

32].

Additionally, short intervals between actions (~30s) may be sufficient for partial recovery and performance maintenance in volleyball. This phenomenon aligns with studies showing that intermittent stimuli allow efficient recovery, particularly in well-trained athletes [

33,

34], and suggest that the ability to maintain or increase jump height after training serves as a training state marker.

Similar findings were reported by Berriel et al. [

35], where a combination of strength and plyometric exercises before a 60-minute technical/tactical session led to improved vertical jump performance in athletes. Similarly, Villalon-Gasch et al. [

36] analyzed the effect of PAPE in female volleyball players during a real game. Comparing a control group (normal warm-up) to an experimental group (strength stimuli), they measured vertical jump performance at various intervals: post-activation (8 min), pre-game (23 min), and across five sets (46, 68, 95, 120, and 123 min). The experimental group achieved peak jump height after the 2nd set (68 minutes post-activation), while the control group peaked after 90 minutes. However, by the 3rd set, both groups showed similar performance improvements, with the PAPE effect diminishing by the end of the match.

In our study, there was a difference between the loads and the motor performance of the analyzed periods, demonstrating that cumulative exposure to training sessions can both improve and impair athletic readiness. In week 6, the team had three consecutive days off, and there were no official matches, allowing for a significant reduction in chronic TL and strain. In this context, the lower demand condition led to improved motor performance in the test week, functioning as a tapering period [

37]. Regarding the accumulation of vertical jumps performed by volleyball players, de Leew et al., [

38] found that performing a large number of jumps in the week before the game is related to worse reception performance, possibly due to neuromuscular fatigue interfering with fine control of technical movement and can be an indicator of the cause of injury [

39]

The correlation between TQR and WB scale results with RPE values reinforces that athletes' recovery status influences their perception of effort. Although no direct influence of training load on next-day motor performance was observed, excessive jump loads did have an impact. Monitoring chronic load accumulation is essential to adjust planning, optimize performance, and reduce injury risk [

12].

Finally, our findings highlight that maintaining or improving vertical jump performance after training sessions can serve as a key marker of training status in volleyball. Load management strategies should be refined to maximize performance and prevent adverse effects of fatigue accumulation.

5. Limitations

This study is not without limitations, and among these, we can list: (i) only one volleyball team was evaluated, which hinders the extrapolation of data regarding the load effect; (ii) the results reflect the analysis of a few weeks of training in the second part of the season; (iii) the analysis was performed considering the team and was not divided by positions and game functions.

6. Conclusions

In our study, it was found that vertical jump measures are effective in assessing the athletic readiness of elite volleyball players. In this sense, it was observed that sessions with EL involving a large number of vertical jumps can enhance jump height performance through mechanisms related to the PAPE effect. This effect can last until the end of sessions lasting around 90 minutes, provided that fatigue does not surpass potentiation, and this balance is related to individual variables such as strength level, task adaptation, and athletic condition. On the other hand, sessions with large quantities of vertical jumps should be avoided up to 3 days before an official game since the residual effect can impair athletes' physical and cognitive performance. Thus, volleyball training sessions should be divided into sessions capable of promoting sufficient stimuli for the activation of potentiation mechanisms and sessions to develop/maintain specific motor endurance for the sport.

Accumulated load has an effect on athletes' motor performance, and a week with reduced training load near the end of the season was able to provide subsequent improvement in vertical jump performance and agility. No correlation was observed between the IL analyzed by RPE and the EL of vertical jumps, a fact that has already been observed in scientific literature, including questioning the adequacy of terms for their purpose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Marcel Pisa and Enrico Puggina.; Methodology, Marcel Pisa.; Software, Marcel Pisa.; Validation, Marcel Pisa and Ricardo Filho; Formal Analysis, Arthur Zecchin; Investigation, Matheus Norberto; Data Curation, Matheus Norberto; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Marcel Pisa and Arthur Zecchin; Writing – Review & Editing, Marcel Pisa and Arthur Zecchin; Supervision, Enrico Puggina.

Funding

This work was not funded by any funding agency.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest that could influence the research outcome.

References

- Soares YM. Treinamento esportivo. 1a. Rio de Janeiro: MedBook; 2014.

- Thomas K, Brownstein CG, Dent J, Parker P, Goodall S, Howatson G. Neuromuscular Fatigue and Recovery after Heavy Resistance, Jump, and Sprint Training. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018 Dec;50(12):2526–35. [CrossRef]

- Impellizzeri FM, Jeffries AC, Weisman A, Coutts AJ, McCall A, McLaren SJ, et al. The “training load” construct: Why it is appropriate and scientific. J Sci Med Sport. 2022 May;25(5):445–8.

- Marcelino R, Mesquita I, Afonso J. The weight of terminal actions in Volleyball. Contributions of the spike, serve and block for the teams’ rankings in the World League 2005. Int J Perform Anal Sport [Internet]. 2008 Jul 1;8(2):1–7. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Castro J, Souza A, Mesquita I. Attack efficacy in volleyball: elite male teams. Percept Mot Skills. 2011 Oct;113(2):395–408. [CrossRef]

- Enoka RM, Duchateau J. Translating Fatigue to Human Performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016 Nov;48(11):2228–38. [CrossRef]

- Kellmann M. Preventing overtraining in athletes in high-intensity sports and stress/recovery monitoring. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010 Oct;20 Suppl 2:95–102. [CrossRef]

- Horta TAG, Filho MGB, Miranda R, Coimbra DR, Werneck FZ. Influência dos saltos verticais na percepção da carga interna de treinamento no voleibol. Rev Bras Med do Esporte [Internet]. 2017 Sep 1 [cited 2020 Apr 4];23(5):403–6. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1517-86922017000500403&lng=en&nrm=isso.

- Duarte TS, Alves DL, Coimbra DR, Miloski B, Bouzas Marins JCJC, Bara Filho MGMG. Technical and Tactical Training Load in Professional Volleyball Players. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2019 Sep;14(10):1–6. [CrossRef]

- Horta TAG, Bara Filho MG, Coimbra DR, Miranda R, Werneck FZ. Training Load, Physical Performance, Biochemical Markers, and Psychological Stress During A Short Preparatory Period in Brazilian Elite Male Volleyball Players. J Strength Cond Res. 2017;1.

- Mendes B, Palao JM, Silvério A, Owen A, Carriço S, Calvete F, et al. Daily and weekly training load and wellness status in preparatory, regular and congested weeks: a season-long study in elite volleyball players. Res Sports Med [Internet]. 2018;26(4):462–73. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Lima RF, González Férnandez FT, Silva AF, Laporta L, de Oliveira Castro H, Matos S, et al. Within-Week Variations and Relationships between Internal and External In-tensities Occurring in Male Professional Volleyball Training Sessions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Jul;19(14).

- Clemente FM, Silva AF, Clark CCTT, Conte D, Ribeiro JJ, Mendes B, et al. Analyzing the Seasonal Changes and Relationships in Training Load and Wellness in Elite Vol-leyball Players. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2020 Feb;1–10.

- Debien PB, Mancini M, Coimbra DR, de Freitas DGS, Miranda R, Bara Filho MG. Monitoring Training Load, Recovery, and Performance of Brazilian Professional Vol-leyball Players During a Season. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2018 Oct;13(9):1182–9.

- García-de-Alcaraz A, Ramírez-Campillo R, Rivera-Rodríguez M, Romero-Moraleda B. Analysis of jump load during a volleyball season in terms of player role. J Sci Med Sport [Internet]. 2020 Oct;23(10):973–8. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Pisa MF, Zecchin AM, Gomes LG, Norberto MS, Puggina EF. Internal load in male professional volleyball: a systematic review. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2022 Nov;62(11):1465–73. [CrossRef]

- Pisa MF, Zecchin AM, Gomes LG, Puggina EF. External load in male professional volleyball: A systematic review. Balt J Heal Phys Act [Internet]. 2022;14(2):article 7. Available from: https://www.balticsportscience.com/journal/vol14/iss2/7/.

- Timoteo TF, Debien PB, Miloski B, Werneck FZ, Gabbett T, Bara Filho MG. Influence of Workload and Recovery on Injuries in Elite Male Volleyball Players. J strength Cond Res. 2018 Aug. [CrossRef]

- Pawlik D, Mroczek D. Fatigue and Training Load Factors in Volleyball. Int J Envi-ron Res Public Health. 2022 Sep;19(18). [CrossRef]

- Bartlett JD, O’Connor F, Pitchford N, Torres-Ronda L, Robertson SJ. Relationships Between Internal and External Training Load in Team-Sport Athletes: Evidence for an Individualized Approach. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2017 Feb;12(2):230–4. [CrossRef]

- Lima RF, Silva A, Afonso JJ, Castro H, Clemente FM. External and internal Load and their Effects on Professional Volleyball Training. Int J Sports Med. 2020 Feb. [CrossRef]

- Claudino JG, Cronin J, Mezêncio B, McMaster DT, McGuigan M, Tricoli V, et al. The countermovement jump to monitor neuromuscular status: A meta-analysis. J Sci Med Sport. 2017 Apr;20(4):397–402. [CrossRef]

- Bosco C, Luhtanen P, Komi P V. A simple method for measurement of mechanical power in jumping. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1983;50(2):273–82.

- Harman, E., Garhammer, J., & Pandorf C. Administration, scoring, and interpreta-tion of selected tests. In: T. R. Baechle & RWE, editor. Essentials of strength training and conditioning. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 2000. p. 287–317.

- 34. McLean BD, Coutts AJ, Kelly V, McGuigan MR, Cormack SJ. Neuromuscular, endocrine, and perceptual fatigue responses during different length between-match microcycles in professional rugby league players. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2010 Sep;5(3):367–83. [CrossRef]

- Kenttä G, Hassmén P. Overtraining and recovery. A conceptual model. Sports Med. 1998 Jul;26(1):1–16. [CrossRef]

- Ade JD, Drust B, Morgan OJ, Bradley PS. Physiological characteristics and acute fatigue associated with position-specific speed endurance soccer drills: production vs maintenance training. Sci Med Footb. 2021 Feb;5(1):6–17. [CrossRef]

- Guan S, Lin N, Yin Y, Liu H, Liu L, Qi L. The Effects of Inter-Set Recovery Time on Explosive Power, Electromyography Activity, and Tissue Oxygenation during Plyome-tric Training. Sensors (Basel). 2021 Apr;21(9). [CrossRef]

- Carroll TJ, Taylor JL, Gandevia SC. Recovery of central and peripheral neuromus-cular fatigue after exercise. J Appl Physiol [Internet]. 2016 Dec 8;122(5):1068–76. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Lima RF, Silva AF, Matos S, de Oliveira Castro H, Rebelo A, Clemente FM, et al. Using inertial measurement units for quantifying the most intense jumping move-ments occurring in professional male volleyball players. Sci Rep. 2023 Apr;13(1):5817.

- Stone MH, Sands WA, Pierce KC, Ramsey MW, Haff GG. Power and power poten-tiation among strength-power athletes: preliminary study. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2008 Mar;3(1):55–67.

- Hodson-Tole EF, Wakeling JM. Motor unit recruitment for dynamic tasks: current understanding and future directions. J Comp Physiol B, Biochem Syst Environ Physiol. 209 Jan;179(1):57–66. [CrossRef]

- Dobbs WC, Tolusso D V, Fedewa M V, Esco MR. Effect of Postactivation Potentia-tion on Explosive Vertical Jump: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J strength Cond Res. 2019 Jul;33(7):2009–18.

- Chen Y, Su Q, Yang J, Li G, Zhang S, Lv Y, et al. Effects of rest interval and training intensity on jumping performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis investigat-ing post-activation performance enhancement. Vol. 14, Frontiers in physiology. Swit-zerland; 2023. p. 1202789.

- Berriel GP, Cardoso AS, Costa RR, Rosa RG, Oliveira HB, Kruel LFM, et al. Effects of Postactivation Performance Enhancement on The Vertical Jump in High-Level Vol-leyball Athletes. J Hum Kinet. 2022 Apr;82:145–53.

- Villalon-Gasch L, Penichet-Tomas A, Sebastia-Amat S, Pueo B, Jimenez-Olmedo JM. Postactivation Performance Enhancement (PAPE) Increases Vertical Jump in Elite Fe-male Volleyball Players. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Jan;19(1):5817.

- Mujika I, Padilla S. Scientific bases for precompetition tapering strategies. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003 Jul;35(7):1182–7. [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw A-W, van Baar R, Knobbe A, van der Zwaard S. Modeling Match Per-formance in Elite Volleyball Players: Importance of Jump Load and Strength Training Characteristics. Sensors (Basel). 2022 Oct;22(20). [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw A-W, van der Zwaard S, van Baar R, Knobbe A. Personalized machine learning approach to injury monitoring in elite volleyball players. Eur J Sport Sci. 2022 Apr;22(4):511–20. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).