Submitted:

13 November 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Physical Variables

2.3.1. Physiological Variables

2.3.2. Biomechanical Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdelkrim, B.; El Fazaa, S.; El Ati, J. Time-Motion Analysis and Physiological Data of Elite Under-19-Year-Old Basketball Players During Competition. Br J Sports Med 2007, 41, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Grady, C.; Fox, J.; Dalbo, V.; Scanlan, A. A Systematic Review of the External and Internal Workloads Experienced during Games-Based Drills in Basketball Players. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2020, 15, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Pérez-Chao, E.; Portes, R.; Gómez, M.Á.; Parmar, N.; Lorenzo, A.; Jiménez Sáiz, S.L. A Narrative Review of the Most Demanding Scenarios in Basketball: Current Trends and Future Directions. J Hum Kinet 2023, 89, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, P.; Gasperi, L.; Makivic, B.; Gomez-Ruano, M.A.; Tessitore, A.; Conte, D. An Ecological Investigation of Average and Peak External Load Intensities of Basketball Skills and Game-Based Training Drills. Biol Sport 2023, 40, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, J.L.; Mclean, B.D.; Impellizzeri, F.M.; Strack, D.S.; Coutts, A.J. Measuring Physical Demands in Basketball : An Explorative Systematic Review of Practices. Sports Medicine 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Ronda, L.; Gámez, I.; Robertson, S.; Fernández, J. Epidemiology and Injury Trends in the National Basketball Association: Pre- and PerCOVID-19 (2017–2021). PLoS One 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, E.; Miranda, N.; Zhang, S.; Sosa, C.; Trapero, J.; Lorenzo, J.; Lorenzo, A. Peak Match Demands in Young Basketball Players: Approach and Applications. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, P.; Pyne, D.; Minahan, C. The Physical and Physiological Demands of Basketball Training and Competition. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2010, 5, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, R.; Ribas, C.; López García, A.; Alonso Pérez-Chao, E. A Comparison of Training and Competition Physical Demands in Professional Male Basketball Players. International Journal of Basketball Studies 2023, 2, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Ronda, L.; Ric, A.; Llabres-Torres, I.; De Las Heras, B.; Schelling, X. Position-Dependent Cardiovascular Response and Time-Motion Analysis during Training Drills and Friendly Matches in Elite Male Basketball Players. Journal of Stregth and Conditioning Research 2016, 30, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, F.M.; Junior, D.B.R.; da Cunha, V.F.; Meireles, G.B.; Filho, M.G.B. Differences between Training and Game Loads in Young Basketball Players. Revista Brasileira de Cineantropometria e Desempenho Humano 2019, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.L.; Stanton, R.; Scanlan, A.T. A Comparison of Training and Competition Demands in Semiprofessional Male Basketball Players. Res Q Exerc Sport 2018, 89, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, D.; Kolb, N.; Scalan, A.T.; Santolamazza, F. Monitoring Training Load and Well-Being during the Un-Season Phase in NCAA Division I Men’s Basketball. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2015, 13, 1067–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, C.G.; Aoki, M.S.; Arruda, A.F.S.; Franciscon, C.; Moreira, A. Monitoring Salivary Immunoglobulin A Responses to Official and Simulated Matches in Elite Young Soccer Players. J Hum Kinet 2016, 53, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupo, C.; Tessitore, A.; Gasperi, L.; Gomez, M.A.R. Session-RPE for Quantifying the Load of Different Youth Basketball Training Sessions. Biol Sport 2017, 34, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reina, M.; García-Rubio, J.; Feu, S.; Ibáñez, S.J. Training and Competition Load Monitoring and Analysis of Women’s Amateur Basketball by Playing Position: Approach Study. Front Psychol 2019, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, A.; Dascombe, B.; Kidcaff, A.P.; Peucker, J.; Dalbo, V. Gender-Specific Activity Demands Experienced during Semiprofessional Basketball Game Play. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2015, 10, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkrim, B.N.; Chaouachi, A.; Chamari, K.; Chtara, M.; Castagna, C. Positional Role and Competitive-Level Differences in Elite-Level Men’s Basketball Players. J Strength Cond Res 2010, 24, 1346–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa, C.; Lorenzo, A.; Trapero, J.; Ribas, C.; Alonso, E.; Jimenez, S.L. Specific Absolute Velocity Thresholds during Male Basketball Games Using Local Positional System; Differences between Age Categories. Applied Sciences 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojskić, H.; Šeparović, V.; Užičanin, E. Modelling Home Advantage in Basketball at Different Levels of Competition; 2011; Vol. 5;

- Trapero, J.; Sosa, C.; Shao Liang, Z.; Portes, R.; Gómez Ruano, M.A.; Bonal, J.; Jiménez Saiz, S.; Lorenzo, A. Comparison of the Movement Characteristics Based on Position-Specific Between Semi-Elite and Elite Basketball Players. Revista de Psicología del Deporte 2019, 28, 140–145. [Google Scholar]

- Aschendorf, P.F.; Zinner, C.; Delextrat, A.; Engelmeyer, E.; Mester, J. Effects of Basketball-Specific High-Intensity Interval Training on Aerobic Performance and Physical Capacities in Youth Female Basketball Players. Physician and Sportsmedicine 2019, 47, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggioni, M.A.; Bonato, M.; Stahn, A.; Torre, A. La; Agnello, L.; Vernillo, G.; Castagna, C.; Merati, G. Effects of Ball Drills and Repeated-Sprint-Ability Training in Basketball Players. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2019, 14, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, E.; Stojiljković, N.; Scanlan, A.T.; Dalbo, V.J.; Berkelmans, D.M.; Milanović, Z. The Activity Demands and Physiological Responses Encountered During Basketball Match-Play: A Systematic Review. Sports Medicine 2018, 48, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthew, D.; Delextrat, A. Heart Rate, Blood Lactate Concentration, and Time-Motion Analysis of Female Basketball Players During Competition. J Sports Sci 2009, 27, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McInnes, S.E.; Carlson, J.S.; Jones, C.J.; McKenna, M.J. The Physiological Load Imposed on Basketball Players During Competition. J Sports Sci 1995, 13, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doma, K.; Leicht, A.; Sinclair, W.; Schumann, M.; Damas, F.; Burt, D.; Woods, C. Impact of Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage on Performance Test Outcomes in Elite Female Basketball Players. J Strength Cond Res 2018, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, T.; Spiteri, T.; Piggott, B.; Bonhotal, J.; Haff, G.G.; Joyce, C. Monitoring and Managing Fatigue in Basketball. Sports 2018, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, A.; Wen, N.; Tucker, P.; Dalbo, V. The Relationships between Internal and External Training Load Models during Basketball Training. J Strength Cond Res 2014, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, J.O.C.; Gregory Haff, G.; Coutts, A.J.; Newton, R.U.; Nimphius, S. The Current State of Subjective Training Load Monitoring—a Practical Perspective and Call to Action. Sports Med Open 2018, 4, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oba, W.; Okuda, T. A Cross-Sectional Comparative Study of Movement Distances and Speed of the Players and a Ball in Basketball Game. International Journal of Sport and Health Science 2008, 6, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanrenterghem, J.; Nedergaard, N.J.; Robinson, M.A.; Drust, B. Training Load Monitoring in Team Sports: A Novel Framework Separating Physiological and Biomechanical Load-Adaptation Pathways. Sports Medicine 2017, 47, 2135–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, D.J.; McBurnie, A.J.; Santos, T.D.; Eriksrud, O.; Evans, M.; Cohen, D.D.; Rhodes, D.; Carling, C.; Kiely, J. Biomechanical and Neuromuscular Performance Requirements of Horizontal Deceleration: A Review with Implications for Random Intermittent Multi-Directional Sports. Sports Medicine 2022, 52, 2321–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warathanagasame, P.; Sakulsriprasert, P.; Sinsurin, K.; Richards, J.; McPhee, J.S. Comparison of Hip and Knee Biomechanics during Sidestep Cutting in Male Basketball Athletes with and without Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. J Hum Kinet 2023, 88, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandorino, M.; Tessitore, A.; Leduc, C.; Persichetti, V.; Morabito, M.; Lacome, M. A New Approach to Quantify Soccer Players’ Readiness through Machine Learning Techniques. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandorino, M.; Tessitore, A.; Lacome, M. Loading or Unloading? This Is the Question! A Multi-Season Study in Professional Football Players. Sports 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelling, X.; Torres, L. Accelerometer Load Profiles for Basketball-Specific Drills in Elite Players. J Sports Sci Med 2016, 15, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olthof, S.B.H.; Tureen, T.; Tran, L.; Brennan, B.; Winograd, B.; Zernicke, R.F. Biomechanical Loads and Their Effects on Player Performance in NCAA D-I Male Basketball Games. Front Sports Act Living 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svilar, L.; Castellano, J.; Jukic, I. Comparison of 5vs5 Training Games and Match Play Using Microsensor Technology in Elite Basketball. J Strength Cond Res 2019, 33, 1897–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, A.K.A.; Stellingwerff, T.; Smith, E.S.; Martin, D.T.; Mujika, I.; Goosey-Tolfrey, V.L.; Sheppard, J.; Burke, L.M. Defining Training and Performance Caliber: A Participant Classification Framework. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2022, 17, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harriss, D.J.; Atkinson, G. Ethical Standards in Sport and Exercise Science Research: 2014 Update. International Journal Sports Medicine 2014, 34, 1025–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodder, R.W.; Ball, K.A.; Serpiello, F.R. Criterion Validity of Catapult Clearsky T6 Local Positioning System for Measuring Inter-Unit Distance. Sensors 2020, 20, 3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luteberget, L.; Spencer, M.; Gilgien, M. Validity of the Catapult ClearSky T6 Local Positioning System for Team Sports Specific Drills, in Indoor Conditions. Front Physiol 2018, 9, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpiello, F.R.; Hopkins, W.G.; Barnes, S.; Tavrou, J.; Duthie, G.M.; Aughey, R.J.; Ball, K. Validity of an Ultra-Wideband Local Positioning System to Measure Locomotion in Indoor Sports. J Sports Sci 2018, 36, 1727–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoppe, M.W.; Baumgart, C.; Polglaze, T.; Freiwald, J. Validity and Reliability of GPS and LPS for Measuring Distances Covered and Sprint Mechanical Properties in Team Sports. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0192708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luteberget, L.; Holme, B.; Spencer, M. Reliability of Wearable Inertial Measurement Units to Measure Physical Activity in Team Handball. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2017, 13, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, J.; Casamichana, D.; Calleja-González, J.; Román, J.S.; Ostojic, S. Reliability and Accuracy of 10 Hz GPS Devices for Short-Distance Exercise. J Sports Sci Med 2011, 10, 233–234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Johnston, R.J.; Watsford, M.L.; Kelly, S.J.; Pine, M.J.; Spurrs, R.W. Validity and Interunit Reliability of 10 Hz and 15 Hz GPS Units for Assessing Athlete Movement Demands. J Strength Cond Res 2014, 28, 1649–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso Perez-Chao, E.; Lorenzo, A.; Scanlan, A.; Lisboa, P.; Sosa, C.; Gómez, M.A. Higher Playing Times Accumulated Across Entire Games and Prior to Intense Passages Reduce the Peak Demands Reached by Elite, Junior, Male Basketball Players. Am J Mens Health. [CrossRef]

- Svilar, L.; Castellano, J.; Jukic, I. Load Monitoring System in Top-Level Basketball Team: Relationship between External and Internal Training Load. Kinesiology 2018, 50, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso Pérez-Chao, E.; Gómez, M.Á.; Lisboa, P.; Trapero, J.; Jiménez, S.L.; Lorenzo, A. Fluctuations in External Peak Demands across Quarters during Basketball Games. Front Psychol. [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, William. ; Marshall, Stephen.; Batterham, Alan.; Hanin, J. Progressive Statistics for Studies in Sports Medicine and Exercise Science. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009, 41, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Guerrero, J.; Suarez-Arrones, L.; Gómez, D.C.; Rodas, G. Comparing External Total Load, Acceleration and Deceleration Outputs in Elite Basketball Players across Positions during Match Play. Kinesiology 2018, 50, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, F. Small-Sided and Conditioned Games in Basketball Training. Strength Cond J 2016, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atli, H.; Yusuf, K.; Alemdarog, U.; Fatma, U. italic>A Comparison of Heart Rate Response and Frequencies of Technical Actions Between Half-Court and Full-Court 3- a Side Games in High School Female Basketball Players. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, D.; Raya-González, J.; Clemente, F.M.; Conte, D.; Rodríguez-Fernández, A. The Effects of Defensive Style and Final Game Outcome on the External Training Load of Professional Basketball Players. Biol Sport 2021, 38, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 4 | 5v5 full court | A 5v5 game is played with 10 players on the court at the same time. The number of consecutive plays and the work-to-rest ratio vary depending on the coach’s feedback and the pauses they implement |  |

| 4 | 5v5v5 | A 5v5v5 game is played where the defending team transitions to offense and attacks the opposite basket |  |

| 4 | 4v4 full court | A 4v4 game is played with 8 players on the court at the same time. When the offensive play ends, the defending team transitions to offense and attacks the same team at the opposite basket. The number of consecutive plays and the work-to-rest ratio ranges between 3 and 6, depending on the coach’s feedback and pauses |  |

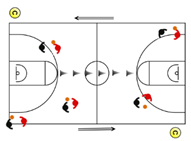

| 4 | 4v4v4 | A 4v4v4 game is played where the defending team transitions to offense and attacks the opposite basket, where another team is waiting to defend |  |

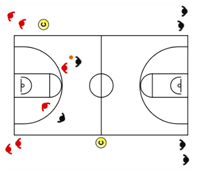

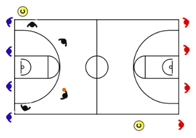

| 3 | 3v3 Full court | A 3v3 game is played with 6 players on the court at the same time. When the offensive play ends, the defending team transitions to offense and attacks the same team at the opposite basket. The number of consecutive plays and the work-to-rest ratio varies between 3 and 6, depending on the coach’s feedback and pauses |  |

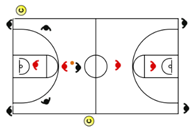

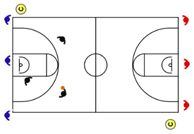

| 3 | 3v3v3 | A 3v3v3 game is played where the defending team transitions to offense and attacks the opposite basket, where another team is waiting to defend |  |

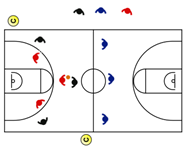

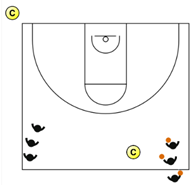

| 3 | Eleven Player Break | A continuous 3v2 situation is played. Among the 5 players involved, the one who gains possession when the play ends (whether through a basket, rebound, or turnover) attacks on the opposite side with two players positioned in the corners against two defenders waiting on the other side |  |

| 3 | 2v2 full court | A 2v2 game is played where, after an offensive play, the team defends at the opposite basket. Following the defensive effort, the team passes to one of the two teammates positioned to transition and attack on the opposite court |  |

| 2 | 1v1 in longitudinal half court (28x7.5m) | The attacking player must attempt to drive past and score after playing a 1v1. Once the offensive play is over, the player who attacked transitions to defense |  |

| 2 | 5v0 full court | A 5v0 drill is conducted at midcourt, followed by another drill at the opposite end. After completing these drills, 5 new players enter the court. |  |

| 2 | 4v0 full court | A 4v0 drill is conducted at midcourt, followed by another drill at the opposite end. After completing these drills, 4 new players enter the court |  |

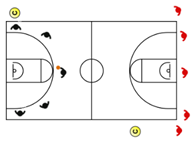

| 2 | 3v0 full court | A 3v0 drill is conducted at midcourt, followed by another drill at the opposite end. After completing these drills, 3 new players enter the court |  |

| 2 | 2v0 (Individual Technical-Tactical) half court | Different individual technical-tactical situations are practiced without opposition in a 2v0 setting |  |

| 2 | 1v0 (Individual Technical-Tactical) half court | Different individual technical-tactical situations are practiced without opposition in a 1v0 setting |  |

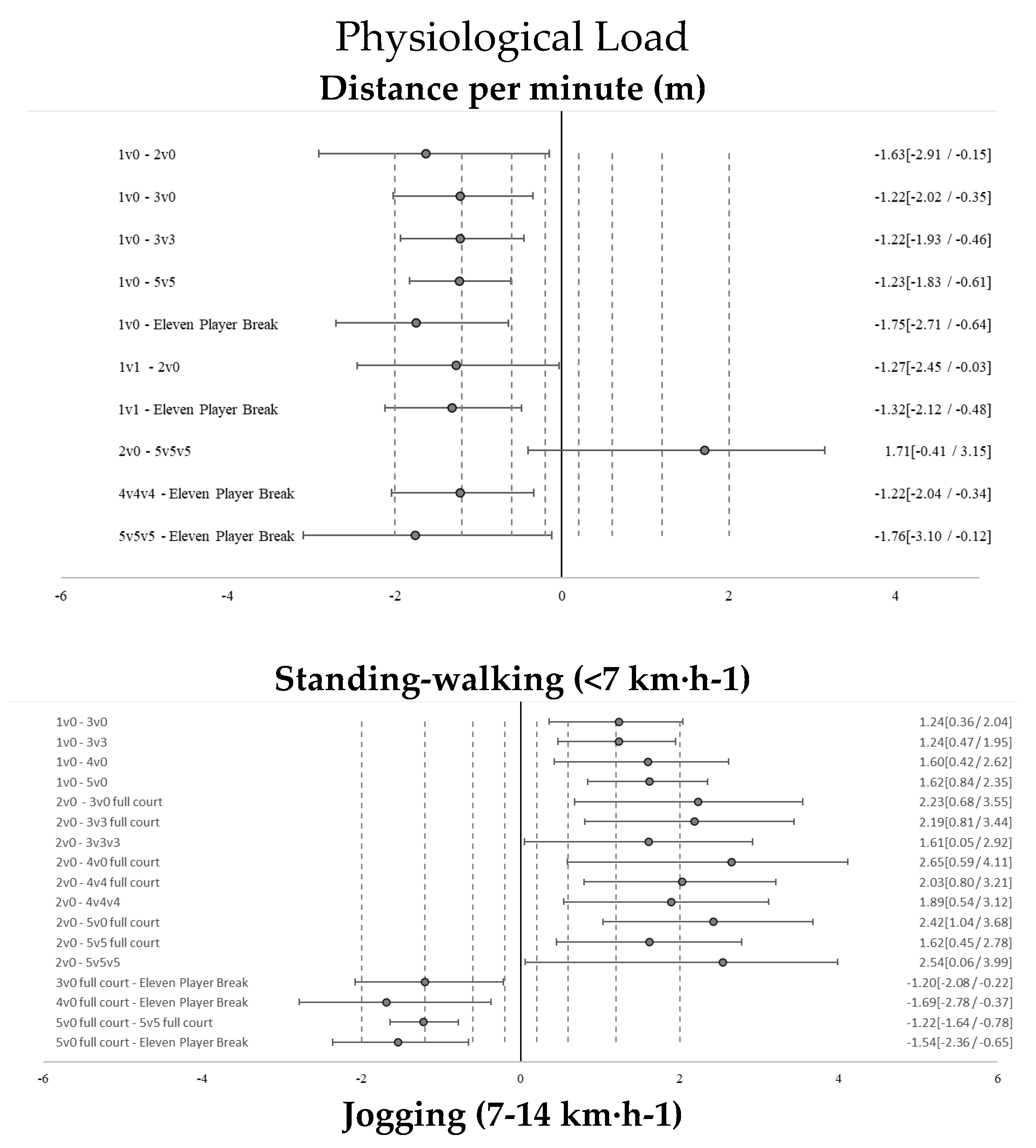

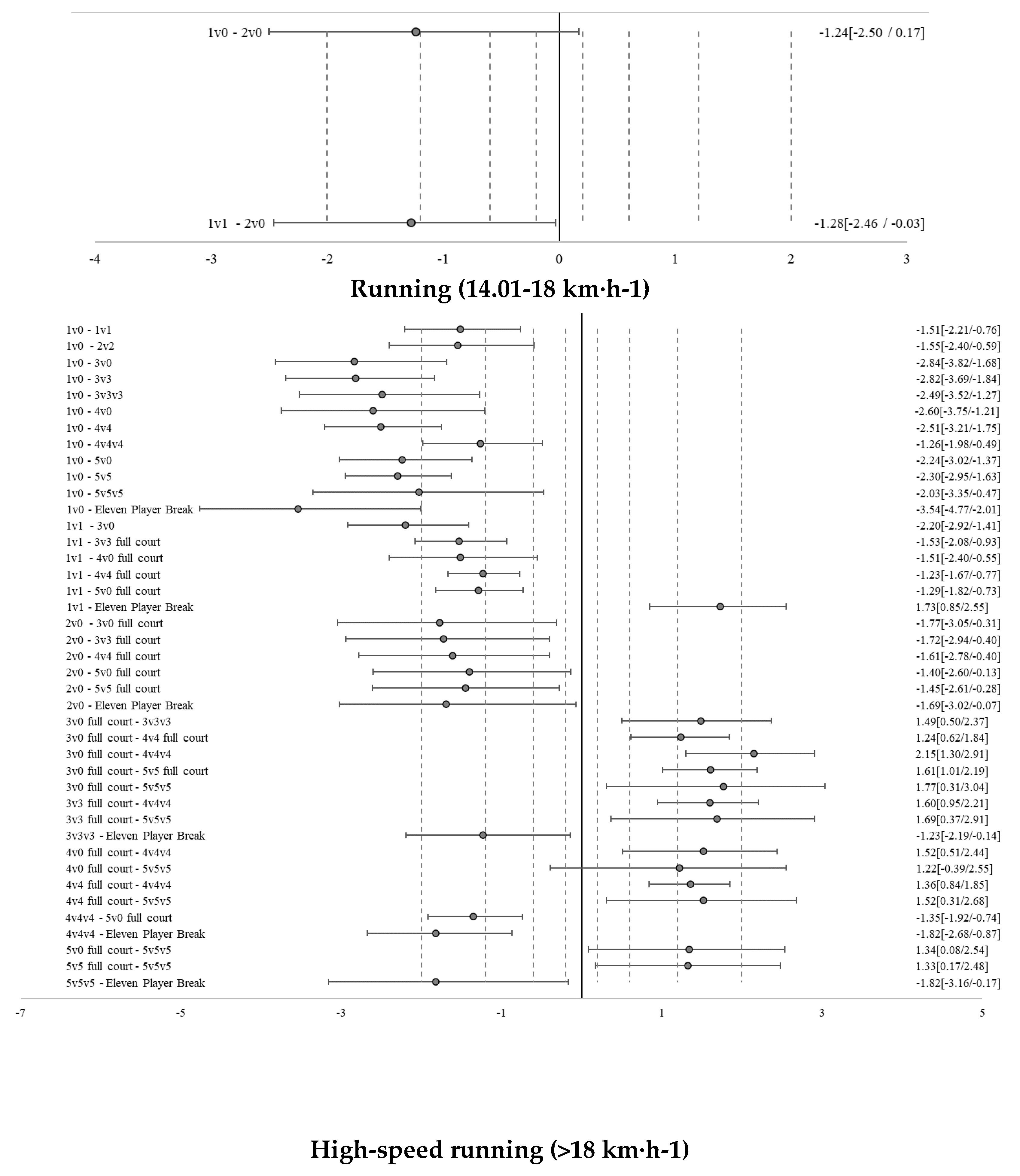

| Variables | Physiological Load | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | Very High | |

| Distance per minute (m) | 18.56 | 62.09 | 75.28 | 80.50 |

| Standing-walking (<7 km·h-1) | 15.53 | 31.75 | 65.40 | 34.35 |

| Jogging (7-14 km·h-1) | 3.13 | 21.36 | 51.81 | 28.05 |

| Running (14.01-18 km·h-1) | 0.85 | 6.37 | 17.32 | 12.29 |

| High-speed running (>18 km·h-1) | 0.22 | 2.42 | 3.77 | 6.02 |

| Samples size (N) | 141 | 1831 | 122 | 1042 |

| Sample proportion (%) | 4.5% | 58.4% | 3.9% | 32.2% |

| Bayesian information criterion (BIC) | 9214.44 | |||

| Average silhouette | 0.5 | |||

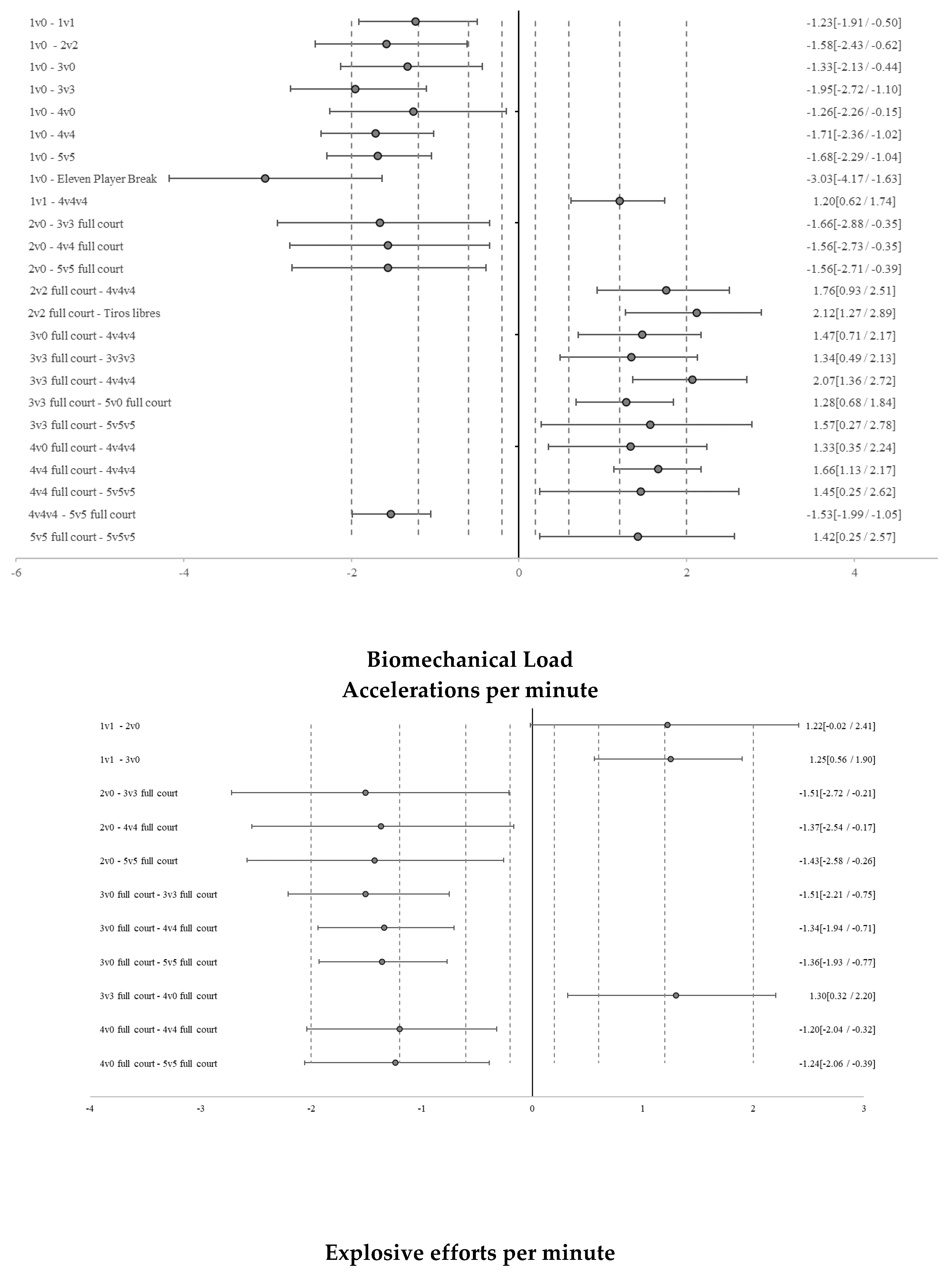

| Variables | Biomechanical Load | |

|---|---|---|

| Low | High | |

| Accelerations per minute | 1.35 | 2.71 |

| Decelerations per minute | 1.20 | 3.38 |

| Explosive efforts per minute | 1.56 | 3.26 |

| PlayerLoad per minute | 5.91 | 8.42 |

| Jumps per minute | 0.65 | 0.73 |

| Sample size (N) | 128 | 2124 |

| Sample proportion (%) | 47.4% | 67.7% |

| Bayesian information criterion (BIC) | 10677,49 | |

| Average silhouette | 0.5 | |

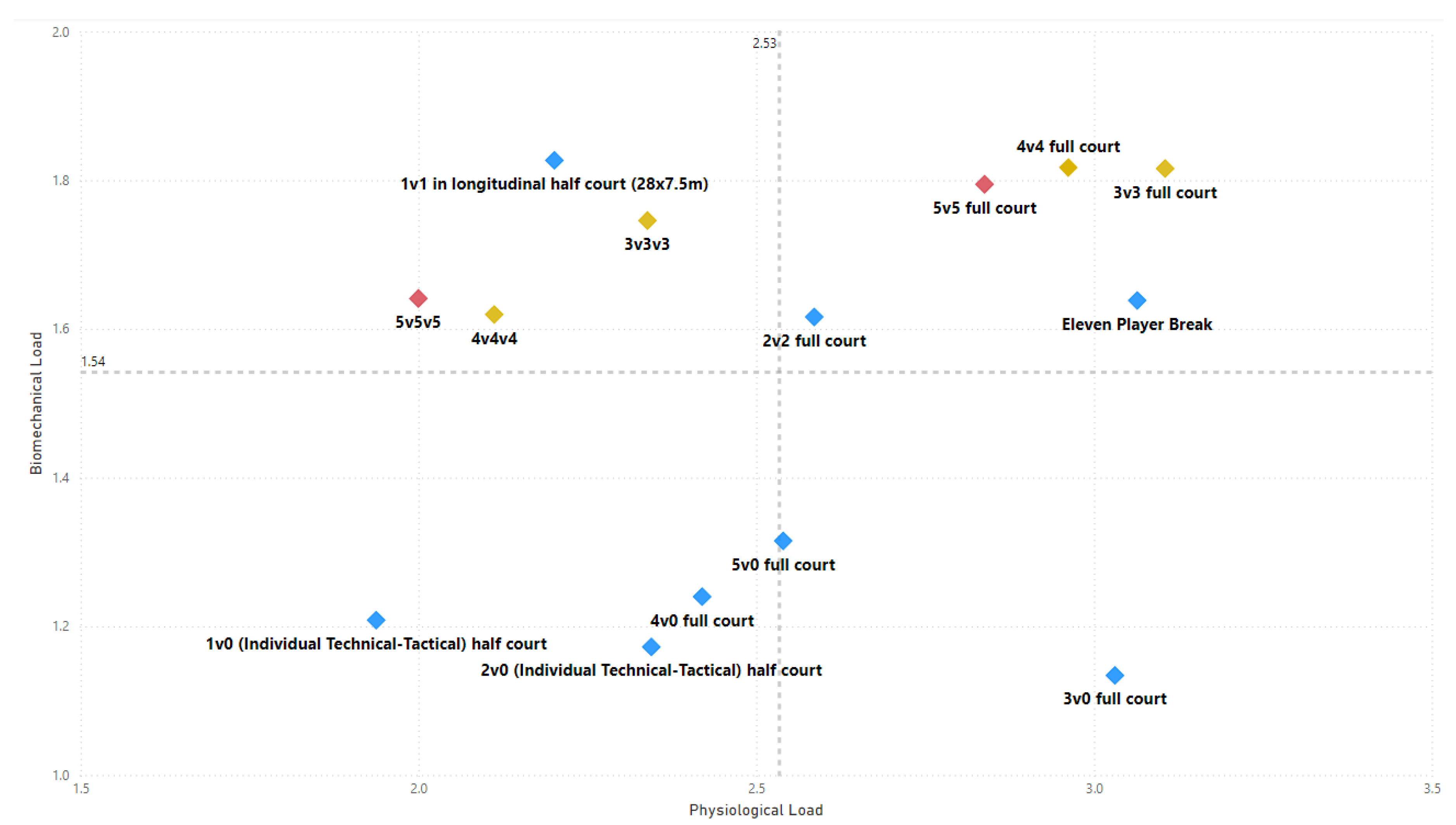

| Drill | Specificity | Physiological Load | Biomechanical Load | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Mean ± SD (% CV) | Median | Mean ± SD (% CV) | ||

| 5v5 full court | 4 | 2 | 2.84 ± 0.99 (35%) | 2 | 1.79 ± 0.40 (22%) |

| 5v5v5 | 2 | 2.00 ± 0.00 (0%) | 2 | 1.64 ± 0.48 (29%) | |

| 4v4 full court | 3 | 2 | 2.96 ± 1.01 (34%) | 2 | 1.82 ± 0.38 (21%) |

| 4v4v4 | 2 | 2.11 ± 0.51 (24%) | 2 | 1.62 ± 0.48 (30%) | |

| 3v3 Full court | 4 | 3.11 ± 0.99 (32%) | 2 | 1.82 ± 0.38 (21%) | |

| 3v3v3 | 2 | 2.34 ± 0.75 (32%) | 2 | 1.75 ± 0.43 (25%) | |

| Eleven Player Break | 2 | 4 | 3.06 ± 1.00 (33%) | 2 | 1.64 ± 0.48 (29%) |

| 2v2 full court | 2 | 2.59 ± 0.99 (38%) | 2 | 1.62 ± 0.48 (30%) | |

| 1v1 in longitudinal half court (28x7.5m) | 2 | 2.20 ± 0.62 (28%) | 2 | 1.83 ± 0.37 (20%) | |

| 5v0 full court | 2 | 2.54 ± 0.92 (36%) | 1 | 1.32 ± 0.46 (35%) | |

| 4v0 full court | 2 | 2.42 ± 0.81 (33%) | 1 | 1.24 ± 0.43 (35%) | |

| 3v0 full court | 3 | 3.03 ± 0.97 (32%) | 1 | 1.13 ± 0.34 (30%) | |

| 2v0 (Individual Technical-Tactical) half court | 2 | 2.34 ± 0.72 (31%) | 1 | 1.17 ± 0.38 (32%) | |

| 1v0 (Individual Technical-Tactical) half court | 2 | 1.94 ± 0.24 (12%) | 1 | 1.21 ± 0.40 (33%) | |

| Physiological Load | Biomechanical Load | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dif. Mean [I / S] | Sig. | Dif. Mean [I / S] | Sig. | ||

| 1v0 | 1v1 | -0.26 [-0.63 / 0.10] | 1.000 | -0.62* [-0.79 / -0.45] | 0.000 |

| 2v0 | -0.41 [-1.06 / 0.25] | 1.000 | 0.04 [-0.26 / 0.34] | 1.000 | |

| 2v2 | -0.64* [-1.09 / -0.21] | 0.000 | -0.41* [-0.61 / -0.2] | 0.000 | |

| 3v0 | -1.09* [-1.54 / -0.65] | 0.000 | 0.07 [-0.13 / 0.28] | 1.000 | |

| 3v3 | -1.16* [-1.54 / -0.80] | 0.000 | -0.61* [-0.78 / -0.44] | 0.000 | |

| 3v3v3 | -0.40 [-0.91 / 0.11] | 0.670 | -0.54* [-0.77 / -0.3] | 0.000 | |

| 4v0 | -0.48 [-1.02 / 0.06] | 0.190 | -0.03 [-0.28 / 0.22] | 1.000 | |

| 4v4 | -1.02* [-1.37 / -0.68] | 0.000 | -0.61* [-0.77 / -0.45] | 0.000 | |

| 4v4v4 | -0.17 [-0.56 / 0.21] | 1.000 | -0.41* [-0.59 / -0.24] | 0.000 | |

| 5v0 | -0.60* [-0.99 / -0.22] | 0.000 | -0.11 [-0.28 / 0.07] | 1.000 | |

| 5v5 | -0.90* [-1.23 / -0.57] | 0.000 | -0.59* [-0.74 / -0.43] | 0.000 | |

| 5v5v5 | -0.06 [-0.65 / 0.52] | 1.000 | -0.43* [-0.7 / -0.16] | 0.000 | |

| Eleven Player Break | -1.13* [-1.68 / -0.58] | 0.000 | -0.43* [-0.68 / -0.18] | 0.000 | |

| 1v1 | 2v0 | -0.14 [-0.75 / 0.46] | 1.000 | 0.65* [0.38 / 0.93] | 0.000 |

| 2v2 | -0.38* [-0.75 / -0.02] | 0.020 | 0.21* [0.05 / 0.38] | 0.000 | |

| 3v0 | -0.83* [-1.19 / -0.47] | 0.000 | 0.69* [0.53 / 0.86] | 0.000 | |

| 3v3 | -0.90* [-1.17 / -0.64] | 0.000 | 0.01 [-0.11 / 0.13] | 1.000 | |

| 3v3v3 | -0.14 [-0.58 / 0.31] | 1.000 | 0.08 [-0.12 / 0.28] | 1.000 | |

| 4v0 | -0.22 [-0.69 / 0.26] | 1.000 | 0.59* [0.37 / 0.8] | 0.000 | |

| 4v4 | -0.76* [-0.99 / -0.53] | 0.000 | 0.01 [-0.09 / 0.11] | 1.000 | |

| 4v4v4 | 0.09 [-0.19 / 0.37] | 1.000 | 0.21* [0.08 / 0.34] | 0.000 | |

| 5v0 | -0.34* [-0.62 / -0.05] | 0.000 | 0.51* [0.38 / 0.64] | 0.000 | |

| 5v5 | -0.64* [-0.85 / -0.43] | 0.000 | 0.03 [-0.06 / 0.13] | 1.000 | |

| 5v5v5 | 0.20 [-0.33 / 0.73] | 1.000 | 0.19 [-0.06 / 0.43] | 0.800 | |

| Eleven Player Break | -0.86* [-1.35 / -0.38] | 0.000 | 0.19 [-0.03 / 0.41] | 0.340 | |

| 2v0 | 2v2 | -0.24 [-0.89 / 0.41] | 1.000 | -0.44* [-0.74 / -0.14] | 0.000 |

| 3v0 | -0.69* [-1.34 / -0.03] | 0.030 | 0.04 [-0.26 / 0.34] | 1.000 | |

| 3v3 | -0.76* [-1.37 / -0.16] | 0.000 | -0.64* [-0.92 / -0.37] | 0.000 | |

| 3v3v3 | 0.01 [-0.70 / 0.71] | 1.000 | -0.57* [-0.89 / -0.25] | 0.000 | |

| 4v0 | -0.08 [-0.80 / 0.65] | 1.000 | -0.07 [-0.4 / 0.26] | 1.000 | |

| 4v4 | -0.62* [-1.21 / -0.03] | 0.030 | -0.65* [-0.91 / -0.37] | 0.000 | |

| 4v4v4 | 0.23 [-0.38 / 0.85] | 1.000 | -0.45* [-0.73 / -0.17] | 0.000 | |

| 5v0 | -0.20 [-0.81 / 0.42] | 1.000 | -0.14 [-0.42 / 0.14] | 1.000 | |

| 5v5 | -0.49 [-1.08 / 0.09] | 0.340 | -0.62* [-0.89 / -0.36] | 0.000 | |

| 5v5v5 | 0.34 [-0.41 / 1.10] | 1.000 | -0.47* [-0.82 / -0.12] | 0.000 | |

| Eleven Player Break | -0.72 [-1.45 / 0.01] | 0.060 | -0.47* [-0.8 / -0.13] | 0.000 | |

| 2v2 | 3v0 | -0.45* [-0.89 / 0.00] | 0.050 | 0.48* [0.28 / 0.68] | 0.000 |

| 3v3 | -0.52* [-0.88 / -0.16] | 0.000 | -0.20* [-0.37 / -0.03] | 0.000 | |

| 3v3v3 | 0.25 [-0.26 / 0.76] | 1.000 | -0.13 [-0.36 / 0.1] | 1.000 | |

| 4v0 | 0.17 [-0.37 / 0.70] | 1.000 | 0.38* [0.13 / 0.62] | 0.000 | |

| 4v4 | -0.38* [-0.71 / -0.04] | 0.010 | -0.20* [-0.36 / -0.05] | 0.000 | |

| 4v4v4 | 0.47* [0.10 / 0.85] | 0.000 | 0 [-0.18 / 0.17] | 1.000 | |

| 5v0 | 0.05 [-0.33 / 0.43] | 1.000 | 0.30* [0.13 / 0.48] | 0.000 | |

| 5v5 | -0.25 [-0.58 / 0.08] | 0.790 | -0.18* [-0.33 / -0.03] | 0.000 | |

| 5v5v5 | 0.59* [0.00 / 1.17] | 0.050 | -0.02 [-0.29 / 0.24] | 1.000 | |

| Eleven Player Break | -0.48 [-1.03 / 0.07] | 0.250 | -0.02 [-0.27 / 0.23] | 1.000 | |

| 3v0 | 3v3 | -0.07 [-0.44 / 0.29] | 1.000 | -0.68* [-0.85 / -0.51] | 0.000 |

| 3v3v3 | 0.69* [0.18 / 1.20] | 0.000 | -0.61* [-0.85 / -0.38] | 0.000 | |

| 4v0 | 0.61* [0.07 / 1.15] | 0.010 | -0.11 [-0.35 / 0.14] | 1.000 | |

| 4v4 | 0.07 [-0.27 / 0.41] | 1.000 | -0.68* [-0.84 / -0.53] | 0.000 | |

| 4v4v4 | 0.92* [0.54 / 1.30] | 0.000 | -0.49* [-0.66 / -0.31] | 0.000 | |

| 5v0 | 0.49* [0.11 / 0.87] | 0.000 | -0.18* [-0.36 / -0.01] | 0.030 | |

| 5v5 | 0.19 [-0.14 / 0.52] | 1.000 | -0.66* [-0.81 / -0.51] | 0.000 | |

| 5v5v5 | 1.03* [0.44 / 1.62] | 0.000 | -0.51* [-0.78 / -0.24] | 0.000 | |

| Eleven Player Break | -0.03 [-0.58 / 0.52] | 1.000 | -0.50* [-0.76 / -0.25] | 0.000 | |

| 3v3 | 3v3v3 | 0.77* [0.32 / 1.21] | 0.000 | 0.07 [-0.13 / 0.27] | 1.000 |

| 4v0 | 0.69* [0.21 / 1.16] | 0.000 | 0.58* [0.36 / 0.79] | 0.000 | |

| 4v4 | 0.14 [-0.09 / 0.38] | 1.000 | 0 [-0.11 / 0.11] | 1.000 | |

| 4v4v4 | 0.99* [0.71 / 1.28] | 0.000 | 0.20* [0.06 / 0.33] | 0.000 | |

| 5v0 | 0.57* [0.28 / 0.85] | 0.000 | 0.50* [0.37 / 0.63] | 0.000 | |

| 5v5 | 0.27* [0.05 / 0.48] | 0.000 | 0.02 [-0.08 / 0.12] | 1.000 | |

| 5v5v5 | 1.11* [0.57 / 1.64] | 0.000 | 0.17 [-0.07 / 0.42] | 1.000 | |

| Eleven Player Break | 0.04 [-0.45 / 0.53] | 1.000 | 0.18 [-0.05 / 0.4] | 0.620 | |

| 3v3v3 | 4v0 | -0.08 [-0.68 / 0.51] | 1.000 | 0.51* [0.23 / 0.78] | 0.000 |

| 4v4 | -0.62* [-1.05 / -0.20] | 0.000 | -0.07 [-0.27 / 0.12] | 1.000 | |

| 4v4v4 | 0.23 [-0.23 / 0.68] | 1.000 | 0.13 [-0.08 / 0.34] | 1.000 | |

| 5v0 | -0.20 [-0.66 / 0.26] | 1.000 | 0.43* [0.22 / 0.64] | 0.000 | |

| 5v5 | -0.50* [-0.91 / -0.08] | 0.000 | -0.05 [-0.24 / 0.14] | 1.000 | |

| 5v5v5 | 0.34 [-0.30 / 0.98] | 1.000 | 0.1 [-0.19 / 0.4] | 1.000 | |

| Eleven Player Break | -0.73* [-1.33 / -0.12] | 0.000 | 0.11 [-0.17 / 0.38] | 1.000 | |

| 4v0 | 4v4 | -0.54* [-1.00 / -0.08] | 0.000 | -0.58* [-0.79 / -0.37] | 0.000 |

| 4v4v4 | 0.31 [-0.18 / 0.80] | 1.000 | -0.38* [-0.6 / -0.16] | 0.000 | |

| 5v0 | -0.12 [-0.61 / 0.37] | 1.000 | -0.08 [-0.3 / 0.15] | 1.000 | |

| 5v5 | -0.42 [-0.87 / 0.03] | 0.120 | -0.56* [-0.76 / -0.35] | 0.000 | |

| 5v5v5 | 0.42 [-0.24 / 1.08] | 1.000 | -0.40* [-0.7 / -0.1] | 0.000 | |

| Eleven Player Break | -0.64* [-1.27 / -0.02] | 0.040 | -0.40* [-0.69 / -0.11] | 0.000 | |

| 4v4 | 4v4v4 | 0.85* [0.59 / 1.10] | 0.000 | 0.20* [0.08 / 0.31] | 0.000 |

| 5v0 | 0.42* [0.16 / 0.68] | 0.000 | 0.50* [0.38 / 0.62] | 0.000 | |

| 5v5 | 0.12 [-0.05 / 0.29] | 1.000 | 0.02 [-0.06 / 0.1] | 1.000 | |

| 5v5v5 | 0.96* [0.45 / 1.48] | 0.000 | 0.18 [-0.06 / 0.41] | 0.980 | |

| Eleven Player Break | -0.10 [-0.57 / 0.37] | 1.000 | 0.18 [-0.04 / 0.39] | 0.410 | |

| 4v4v4 | 5v0 | -0.43* [-0.74 / -0.12] | 0.000 | 0.31* [0.16 / 0.45] | 0.000 |

| 5v5 | -0.73* [-0.97 / -0.49] | 0.000 | -0.18* [-0.28 / -0.07] | 0.000 | |

| 5v5v5 | 0.11 [-0.43 / 0.65] | 1.000 | -0.02 [-0.27 / 0.23] | 1.000 | |

| Eleven Player Break | -0.95* [-1.45 / -0.45] | 0.000 | -0.02 [-0.25 / 0.21] | 1.000 | |

| 5v0 | 5v5 | -0.30* [-0.54 / -0.06] | 0.000 | -0.48* [-0.59 / -0.37] | 0.000 |

| 5v5v5 | 0.54 [0.00 / 1.08] | 0.050 | -0.33* [-0.57 / -0.08] | 0.000 | |

| Eleven Player Break | -0.52* [-1.03 / -0.02] | 0.030 | -0.32* [-0.55 / -0.09] | 0.000 | |

| Partido oficial | -0.66* [-1.00 / -0.32] | 0.000 | -0.59* [-0.75 / -0.44] | 0.000 | |

| Tiros libres | 1.54* [1.16 / 1.92] | 0.000 | 0.32* [0.14 / 0.49] | 0.000 | |

| 5v5 | 5v5v5 | 0.84* [0.33 / 1.34] | 0.000 | 0.15 [-0.08 / 0.39] | 1.000 |

| Eleven Player Break | -0.23 [-0.69 / 0.24] | 1.000 | 0.16 [-0.06 / 0.37] | 1.000 | |

| 5v5v5 | Eleven Player Break | -1.06* [-1.73 / -0.39] | 0.000 | 0 [-0.3 / 0.31] | 1.000 |

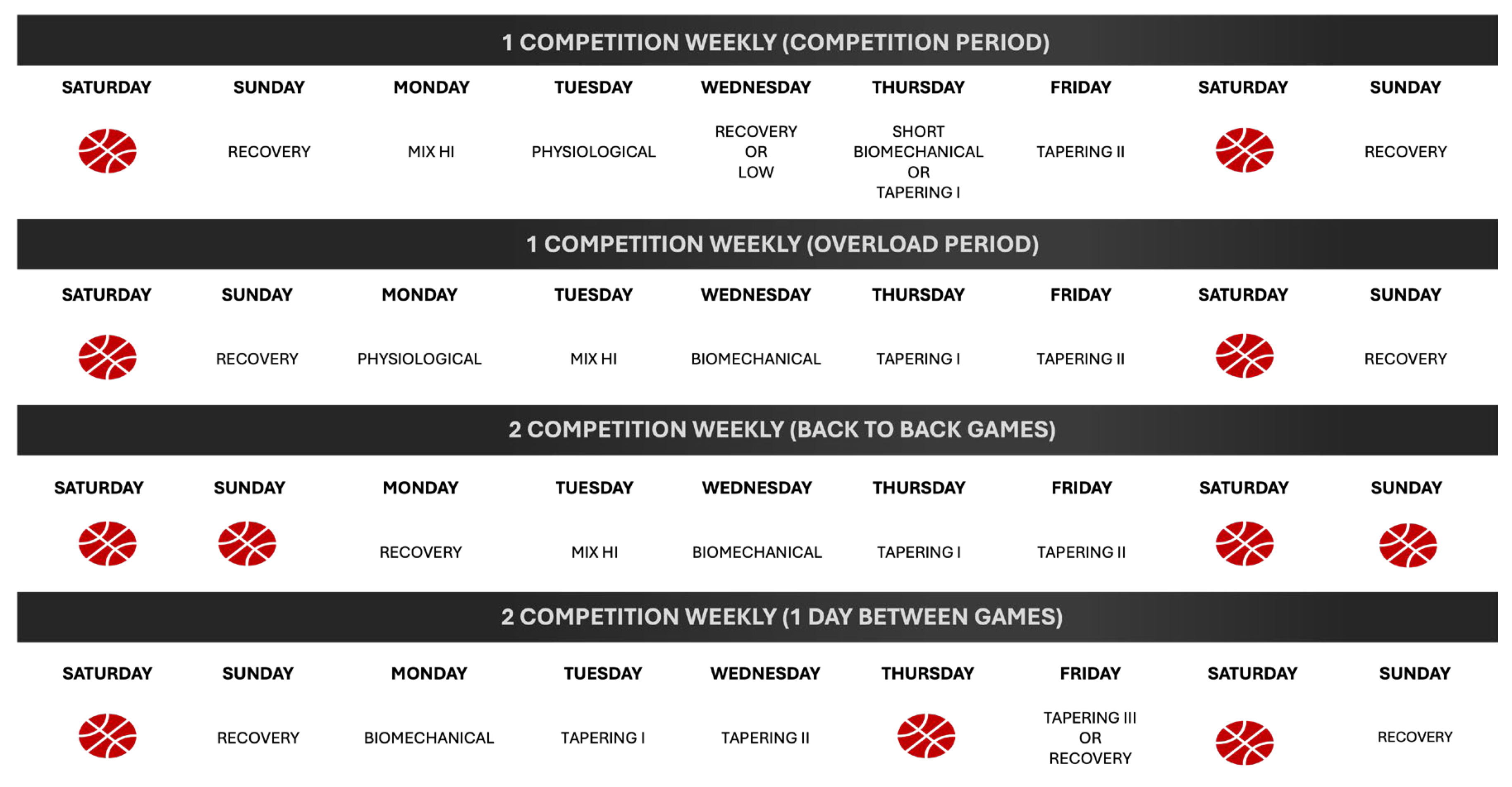

| Orientation | Session duration | Tasks | Task duration |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main: | 3v0-4v0-5v0 | 15-20 min | ||

| Physiological | 60-90 min | Reinforcing: | 3v3-4v4-5v5 | 10-12 min |

| Accessories: | 1v0-2v0 | 10-12 min | ||

| Main: | 1v1FC-3v3v3-4v4v4-5v5v5 | 15-20 min | ||

| Biomechanical | 60-90 min | Reinforcing: | 5v5HC | 10-12 min |

| Accessories: | 1v0-2v0 | 10-12 min | ||

| Main: | 2v2 FC-11PB-3v3-4v4-5v5-SGs | 15-20 min | ||

| Mixed high intensity | 60-90 min | Reinforcing: | - | - |

| Accessories: | 1v0-2v0 | 10-12 min | ||

| Main: | 3v3v3-4v4v4-5v5v5-4v4-5v5 | 15-20 min | ||

| Tapering I | 60-75 min | Reinforcing: | 3v3 | 10-12 min |

| Accessories: | 1v0-2v0 | 10-12 min | ||

| Main: | 5v5v5-4v4-5v5 | 15-20 min | ||

| Tapering II | 45-60 min | Reinforcing: | 5v0 | 10-12 min |

| Accessories: | 1v0-2v0 | 10-12 min | ||

| Main: | 5v0 | 8-10 min | ||

| Tapering III | 30-45 min | Reinforcing: | 5v5v5-5v5 (limited contact, no tape) | 5-8 min |

| Accessories: | 1v0-2v0 | 10-12 min | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).