1. Introduction

Lysosomal Storage Disorders (LSDs) are a group of rare diseases comprising more than 70 inherited metabolic disorders that are being characterized by lysosomal dysfunction and subsequent accumulation of undegraded substrates within lysosomes. LSDs are monogenic diseases caused by alterations in genes encoding proteins involved in normal lysosomal function, such as lysosomal enzymes and lysosomal membrane proteins, and their combined prevalence is estimated to be approximately 1 in 8,000 live births [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Lysosomal impairment leads to the dysregulation of a diverse range of cellular processes being associated with lysosomes, such as membrane repair, vesicle trafficking, lipid homeostasis, signaling, cell death pathways, autophagic flux and clearance of autophagosomes. Therefore, autophagic impairment has been described as a common mechanism of pathology in an increasing number of LSDs [

4,

5,

6]. Despite their heterogeneity, their major clinical symptoms include hepatosplenomegaly, pulmonary and cardiac disorders, skeletal abnormalities and -often- central nervous system (CNS) dysfunction, with patients being frequently presented with a progressive neurodegenerative clinical course [

6,

7]. Typically, LSDs are primarily classified according to the biochemical properties of the accumulated undegraded substrate, and include sphingolipidoses, glycogen storage diseases and mucopolysaccharidoses [

4,

8].

Sphingolipidoses are disorders caused by genetic defects in the catabolism of sphingosine-containing lipids, and their accumulation affects both the CNS and peripheral organs [

9]. Gaucher, Fabry, Tay-Sachs and Niemann-Pick are classified among the most common sphingolipid metabolism diseases [

8,

9,

10]. Gaucher disease (GD), which is subdivided into three different types, is the most prevalent form of sphingolipidoses, and is caused by mutations in the

GBA gene, which encodes for the lysosomal hydrolase β-Glucocerebrosidase, responsible for the degradation of glucosylceramide into glucose and ceramide [

4,

8,

9,

10]. Fabry, an inherited X-linked disease, is the second most common form of sphingolipidoses [

2], and is caused by mutations in the

GLA gene encoding the enzyme α-Galactosidase A, which catalyzes the lysosomal hydrolysis of globotriaosylceramide [

4,

7,

10]. Tay-Sachs, a type of GM2 gangliosidosis, is presented with severe neurological symptoms and is caused by mutations in the

HEXA gene encoding the enzyme β-Hexosaminidase A, which is responsible for breaking down GM2 gangliosides, resulting in their toxic accumulation in neuronal tissues [

11]. Niemann-Pick is a group of predominantly neurodegenerative disorders classified in types A and B, caused by mutations in the

SMPD1 gene, while type C derives from mutations in the

NPC1 or

NPC2 genes. In types A and B, the affected enzyme is the Sphingomyelinase (ASM), leading to sphingomyelin buildup, whereas in Niemann-Pick type C, proteins that mediate cholesterol transport from endosomes/lysosomes are seriously affected, causing endo-lysosomal accumulation of cholesterol, glycosphingolipids and sphingomyelin, resulting in severe neurological pathology [

1,

6,

12].

Glycogen storage diseases (GSDs) comprise a group of inherited metabolic disorders caused by mutations in genes encoding enzymes of glycogen metabolism. Among them, Pompe disease, also known as GSD II, is classified as a major LSD family member. Pompe disease results from mutations in the

GAA gene encoding α-Glucosidase, which is a key lysosomal enzyme responsible for the hydrolysis of glycogen to glucose. The hallmark of Pompe disease is glycogen accumulation in lysosomes, predominantly in muscle cells, leading to cardiorespiratory failure [

4,

7,

8].

Mucopolysaccharidoses (MPSs) form a group of eleven LSD pathologies, characterized by the cellular accumulation of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), which are negatively charged polysaccharides essential for several cellular processes, including signaling and development. The classification of MPSs is based on mutations in specific enzymes that catabolize target substrates, with MPS I, II and III being the most common ones [

4]. MPS type I (MPS I) is caused by the deficiency of lysosomal hydrolase α-L-Iduronidase (IDUA), leading to the accumulation of dermatan- and heparan-sulfate inside lysosomes of a wide range of tissues. The severe form of MPS I, known as Hurler syndrome, is characterized by early onset, and progressive somatic and neurological impairments [

13]. MPS II, also known as Hunter syndrome, is caused by mutations in the

IDS gene on the X chromosome and is typically described by neurological deterioration. These mutations result in a critical deficiency of Iduronate-2-sulfatase (IDS), an enzyme responsible for breaking down dermatan- and heparan-sulfate. Finally, Sly disease, also known as MPS VII, is caused by mutations in the

GUSB gene, resulting in β-Glucuronidase (GUSB) enzyme deficiency. This leads to the accumulation of dermatan-, heparan- and chondroitin-sulfate GAGs, causing progressive multi-system dysfunctions [

4,

14].

Neurological dysfunction and progressive neurodegeneration are key symptoms of LSDs [

6]. The study of -animal- model organisms is imperative for advancing our understanding of human pathologies, thus enabling the identification of novel disease-related pathways that have the potential to serve as drug targets. Furthermore, recent progress has led to development of more powerful and reliable animal models that can more precisely mirror aberrant phenotypes and pathological processes of human diseases and, in particular, LSDs [

15,

16,

17]. A recently explored therapeutic approach for LSDs is the targeted gene therapy that uses genome-editing technologies, like CRISPR/Cas9. However, these strategies encounter several technical challenges and bioethical considerations, making it essential to study their effects

in vivo, using animal models that can closely replicate LSD-specific phenotypes. Given the imminent need for robust

in vivo models, we have, herein, generated transgenic

Drosophila flies, via exploitation of the -combined- GAL4/UAS and RNAi gene-targeting system, to mechanistically illuminate LSD-associated pathologies, at the genetic level, during aging. This platform provides a dynamic, valuable and versatile tool to deeply investigate systemic pathologies and successfully explore novel therapies for LSD-affected cohorts.

4. Discussion

Most Lysosomal Storage Disorders (LSDs) lack effective treatments, rendering genome editing one of the most promising therapeutic strategies. However, before these genome editing tools can be applied in humans, several critical steps must precede, ranging from

in vitro testing to clinical trials. To maximize safety and gather extensive preliminary data,

in vivo modeling, using invertebrates, has gained major attention in the recent years [

15,

17]. These organisms offer a wide array of genetic tools and allow the

in vivo study of various biological pathways and therapeutic approaches, in shorter times and with fewer ethical concerns than those in mammals.

Drosophila melanogaster is a well-established invertebrate model system that offers an ideal background for genetic and biological studies of different human pathologies, as it contains functional orthologs for ~75% of the human disease-related genes [

31].

Drosophila also features a plethora of genetic tools, including the GAL4/UAS, CRISPR/Cas9 and RNAi molecular platforms, which allow cell/tissue-specific gene targeting/downregulation [

32,

33].

In the present study, we suitably employed the -binary- GAL4/UAS and RNAi genetic systems, to selectively knockdown fly orthologs of human LSD-related genes, along the brain-midgut axis, during aging. Employment of commercially available transgenic strains, directly obtained from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC; Indiana, USA), enabled us to systemically investigate their morbid effects, in vivo. These findings provide a powerful invertebrate model for future studies, to broadly explore and deeply comprehend the molecular mechanisms that control LSD-pathology (initiation and progression), and to successfully develop novel genetic- and drug-based strategies for LSD-targeting therapies.

Sphingolipidoses represent a sub-category of LSDs being developed by deficiencies in enzymes responsible for the catabolism of sphingolipids, and they mainly affect nervous-system and peripheral-organ tissues. Gaucher disease (GD) is the most prevalent form and derives from deficiencies in the β-Glucocerebrosidase (GBA1) enzyme, leading to toxic accumulation of glucosylceramide [

10]. Utilization of mouse models for Gaucher disease (GD) has proven challenging and limited, due to the elevated perinatal lethality associated with

GBA1 gene mutations [

10,

34].

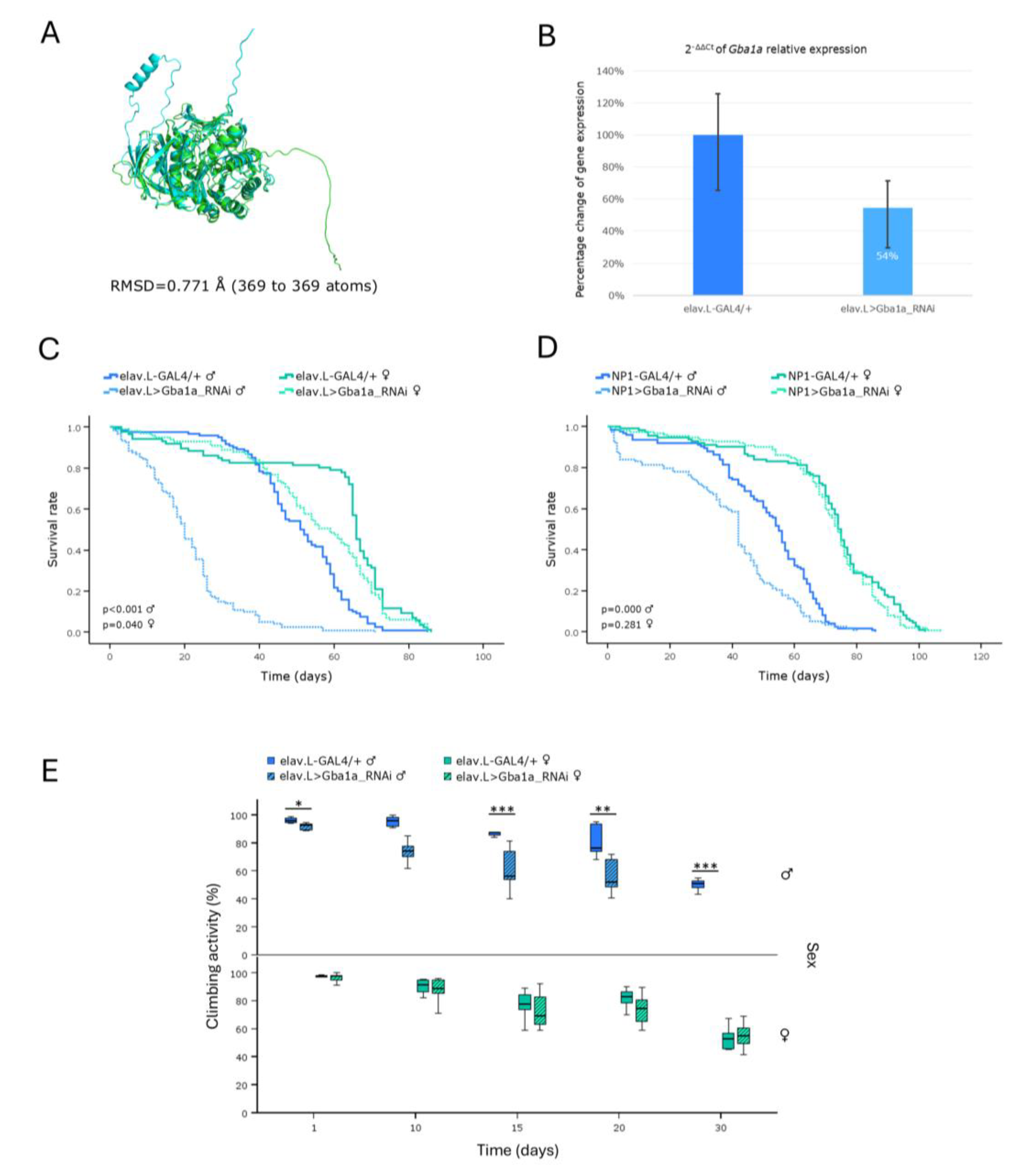

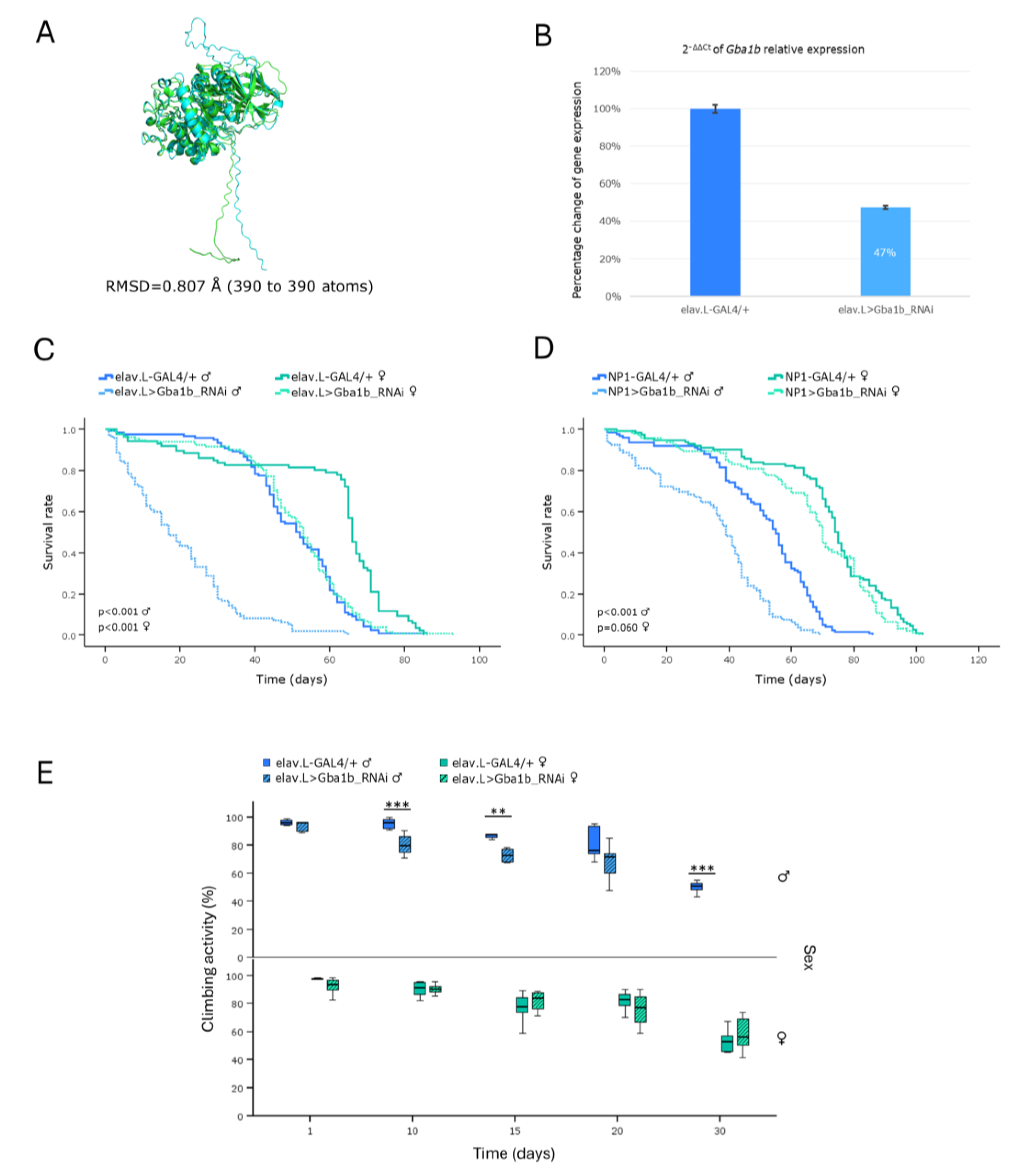

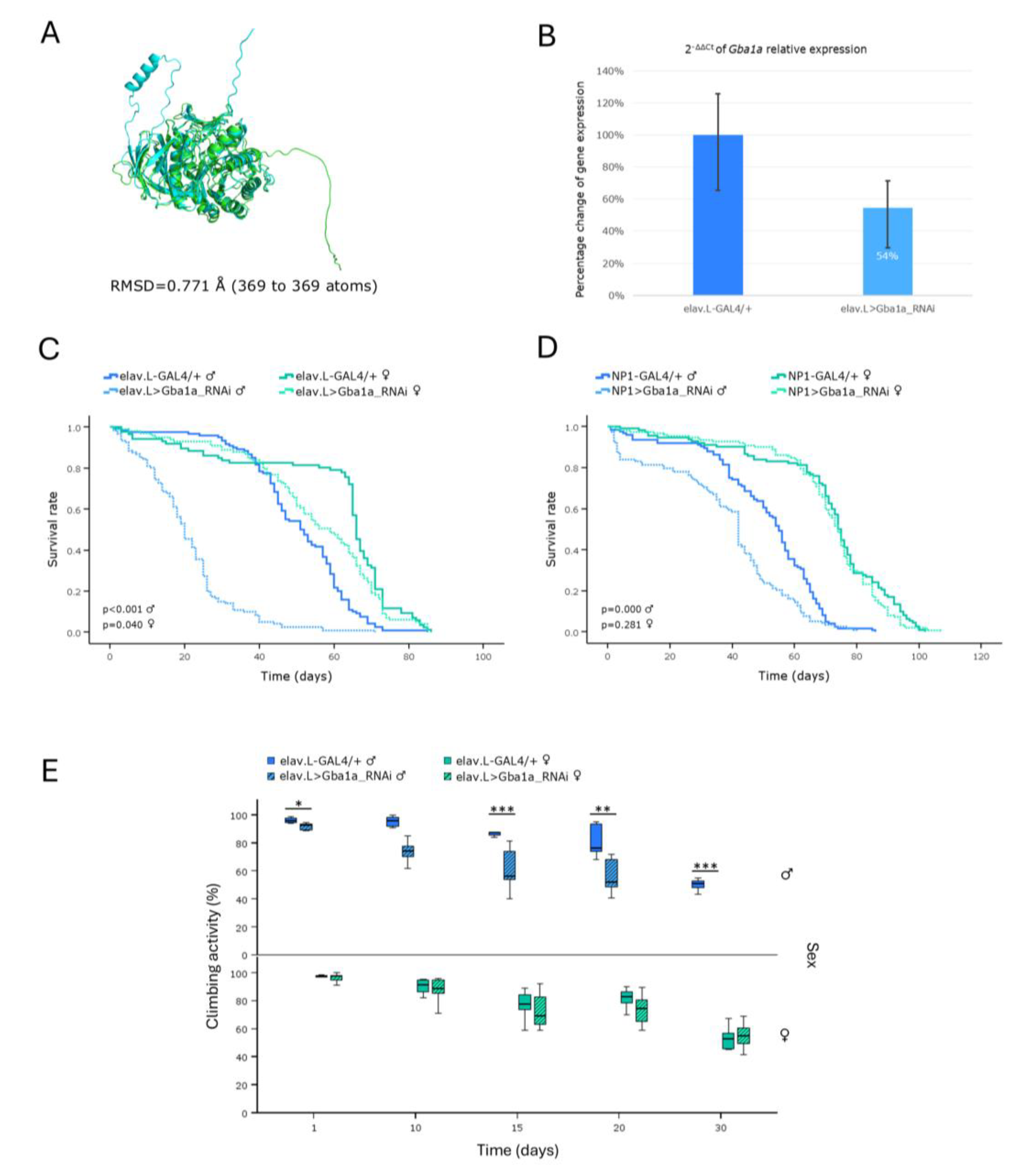

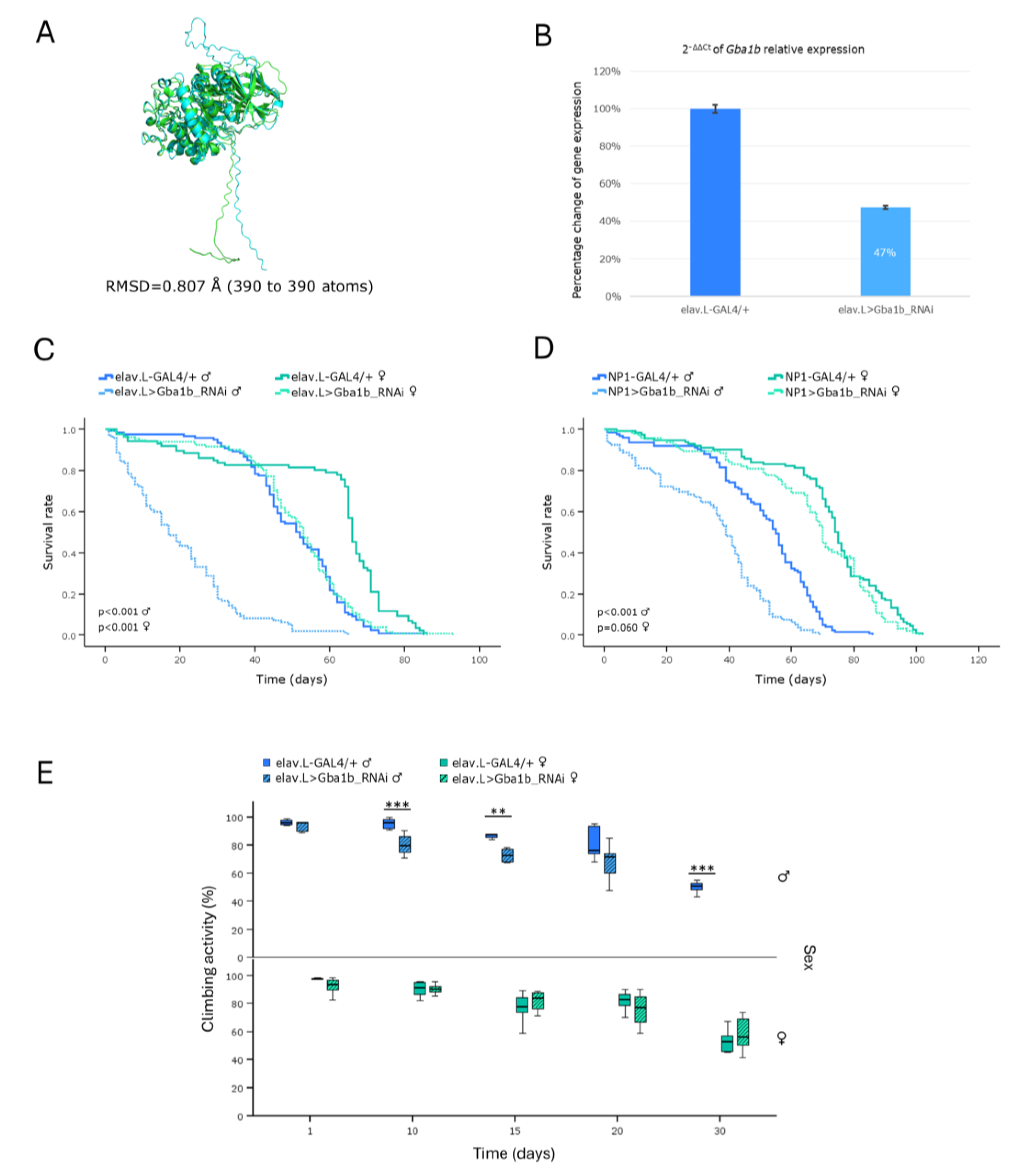

Hence, towards the establishment of a new

in vivo model for the disease (GD), we, herein, investigated the impact of downregulating the

Drosophila Gba1a and

Gba1b orthologs of human

GBA1 gene, along the brain-midgut axis, during aging. Our results revealed a marked reduction in lifespan and climbing ability, with females being more severely affected, compared to male populations. A previous study of

Drosophila Minos-insertion mutants of the

GBA1 orthologs reported that

Gba1b mutants exhibited shortened lifespan and impaired climbing ability, whereas

Gba1a mutants did not present significant pathologies [

35]. Although

Drosophila Gba1a and

Gba1b fly orthologs show differential tissue-expression patterns, with

Gba1a being primarily expressed in the midgut, and

Gba1b being detected in the adult head and fat body [

36], both genes seem to affect fly longevity and kinetic ability in a similar pattern, when downregulated in brain and midgut tissues.

Therefore, our approach indicates that both genes are essential for motor performance and survival in

Drosophila. The progressive loss of neuronal cells and the resulting neurotoxicity in Gaucher disease (GD) [

10] likely underlie the observed pathologies in locomotor activity and lifespan. The, herein, identified sex-specific differences in our

Drosophila Gaucher disease (GD) model system may arise from multiple factors, including hormonal regulation, metabolic programs, immune responses and reproductive properties [

37,

38,

39]. Taken together, our findings strongly support

Drosophila as a powerful and versatile

in vivo model for Gaucher disease (GD), providing insights into its genetic and pathophysiological mechanisms, including sex-specific disease manifestations.

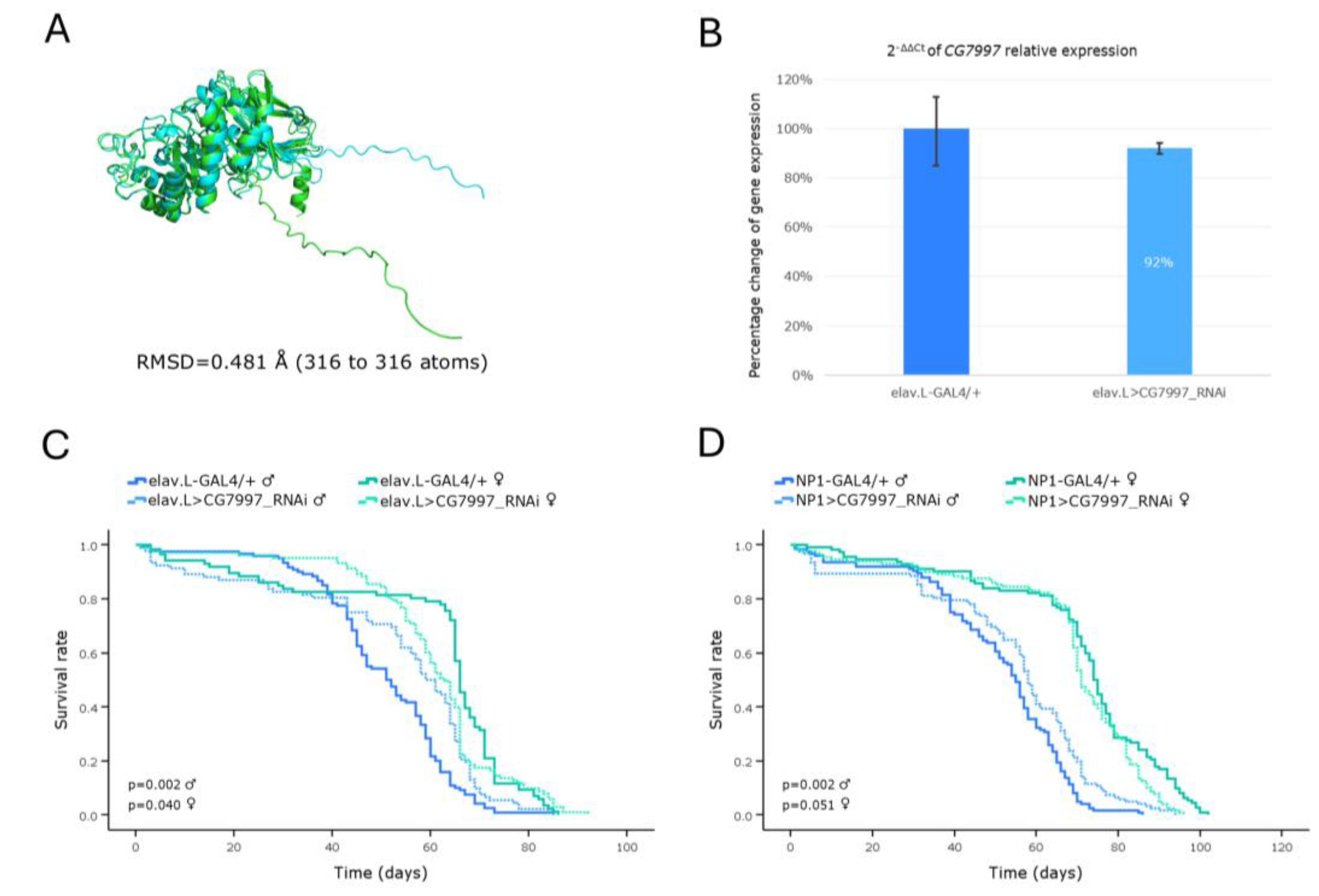

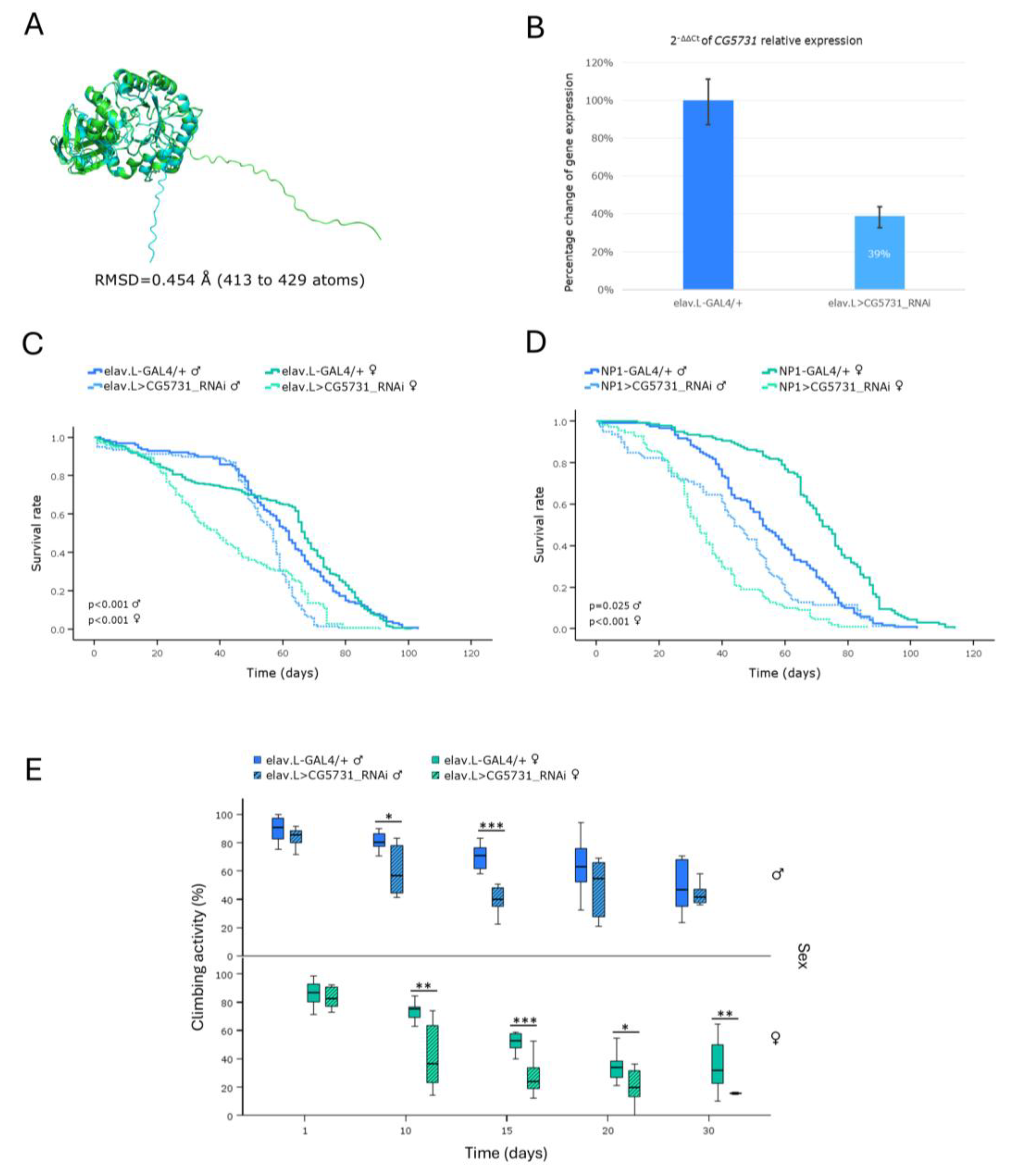

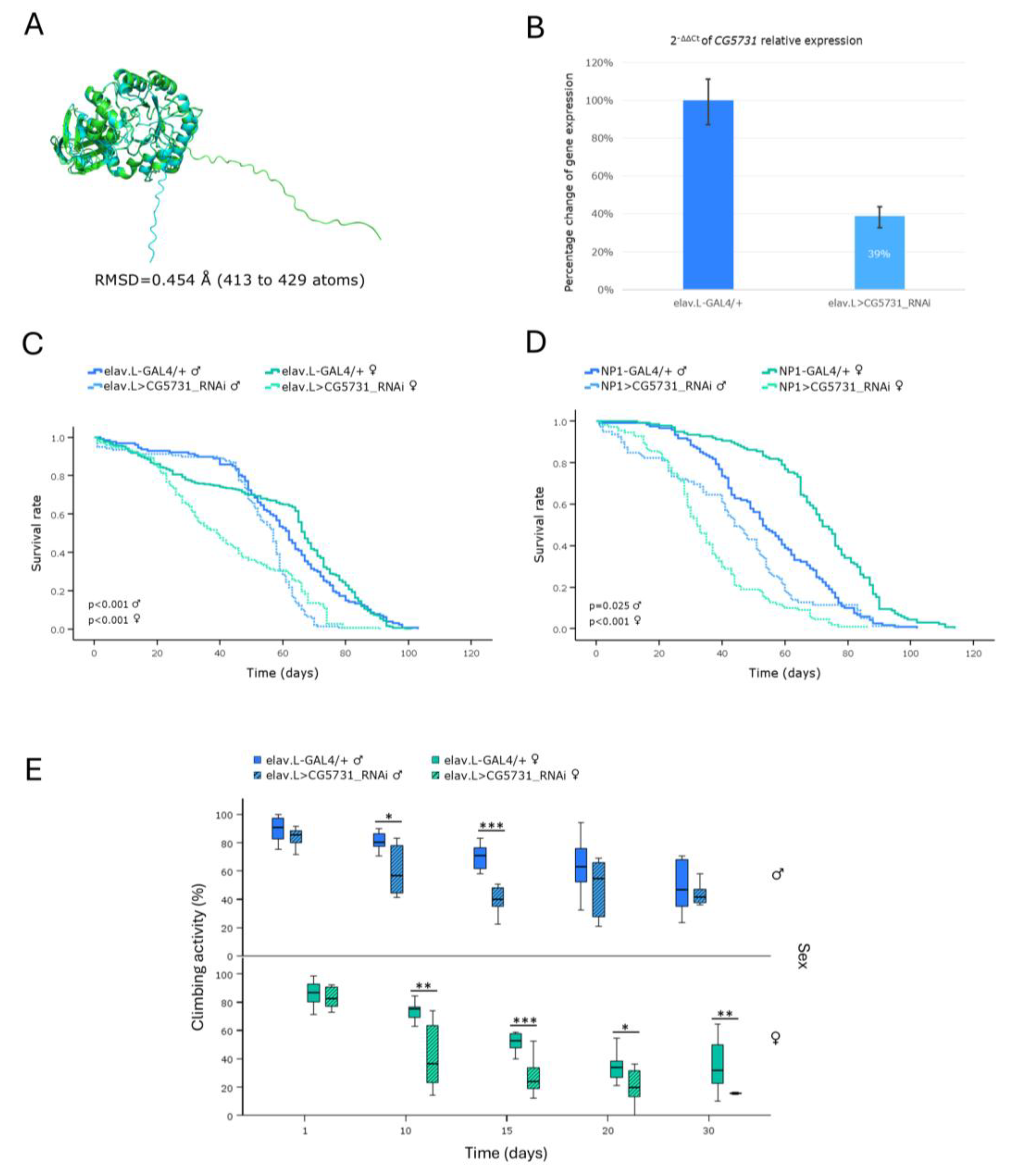

Fabry is an X-linked recessive sphingolipidosis caused by a deficiency in the lysosomal enzyme α-Galactosidase A, due to mutations in the human

GLA gene [

7]. Interestingly, in our model system, herein being investigated, genetic downregulation of the fly

GLA ortholog,

CG5731, proved capable to more severely affect female flies, in both life expectancy and climbing capacity, compared to male populations. Of note, the sex-linked inheritance pattern having been observed in humans cannot be directly applied in

Drosophila, since male flies upregulate their single X chromosome via dosage compensation [

40] and, additionally,

CG5731 is not an X-linked gene. A mechanistic explanation for the -comparatively- increased sensitivity detected in female flies may be associated with gender- and/or tissue-specific gene-expression programs, and differences in metabolic/nutritional demands and/or hormonal pathway/network activities. Moderate homologies might also reflect redundant or compensatory functions by other enzymes, or alternative mechanisms, in

Drosophila that are absent or less efficient in humans. In a mouse model of the disease (FD), both male and female mice, deficient in α-Gal A (α-Galactosidase A), manifested a clinically normal phenotype at the 10

th-14

th weeks of age, thus rendering Fabry-disease (FD) modeling, in this vertebrate/mammalian system, challenging and limited [

41]. However, in a study of

Drosophila transgenic populations, expressing the human mutant

GLA (variant) forms A156V and A285D, significant locomotor dysfunction and reduced lifespan were observed, compared to control flies (expressing the human wild-type enzyme). Strikingly, these phenotypes could be ameliorated with Migalastat (Fabry disease -FD- medication) treatment [

42].

Altogether, our RNAi-based genetic platform, which targets the endogenous expression of CG5731 fly gene (human GLA homolog), specifically in the brain-midgut axis, during aging, may offer a powerful, reliable, multifaceted, dynamic and sensitive in vivo model system, for comprehensively studying Fabry disease (FD), to enabling efficient drug screening and to illuminating underlying disease mechanisms.

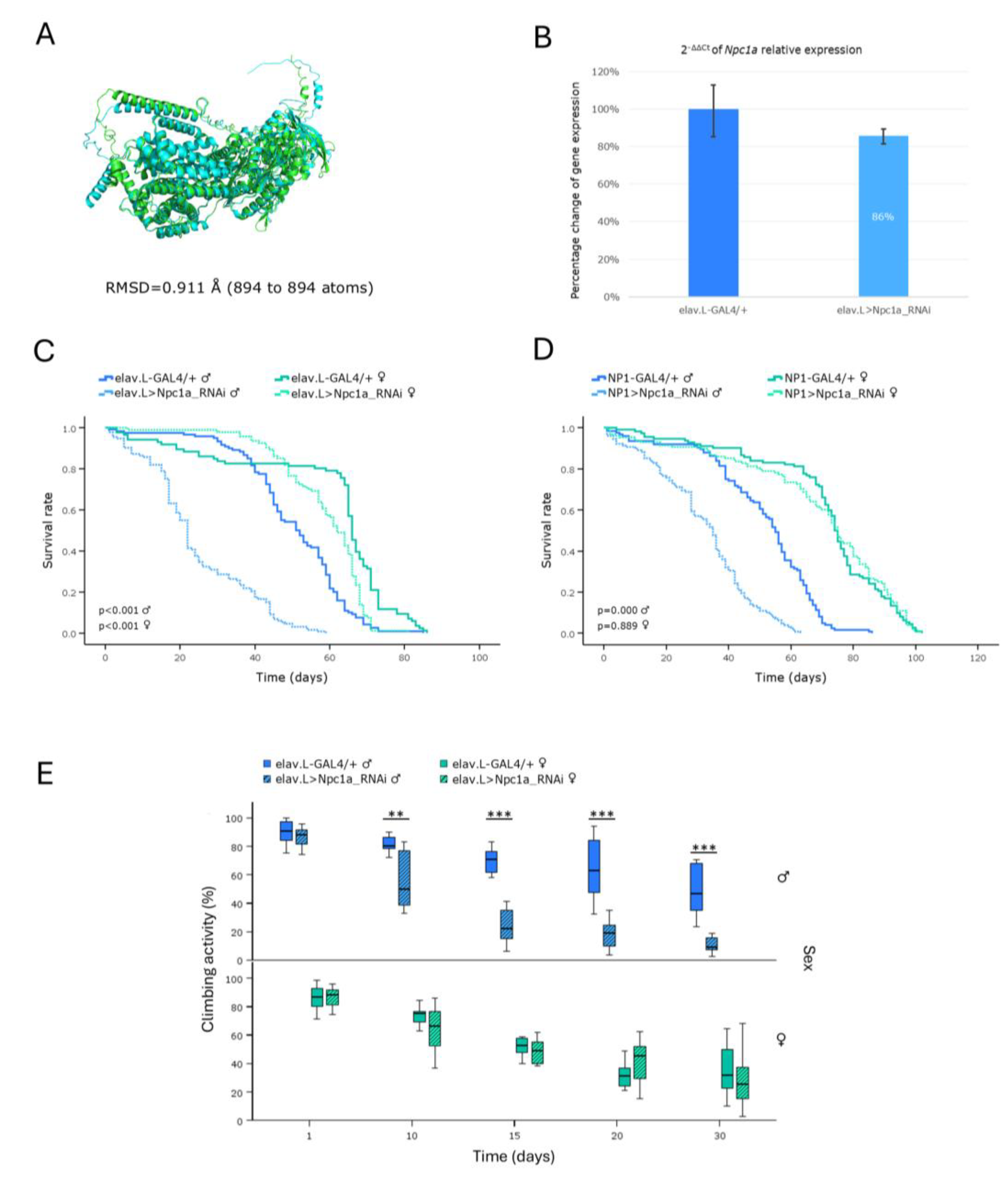

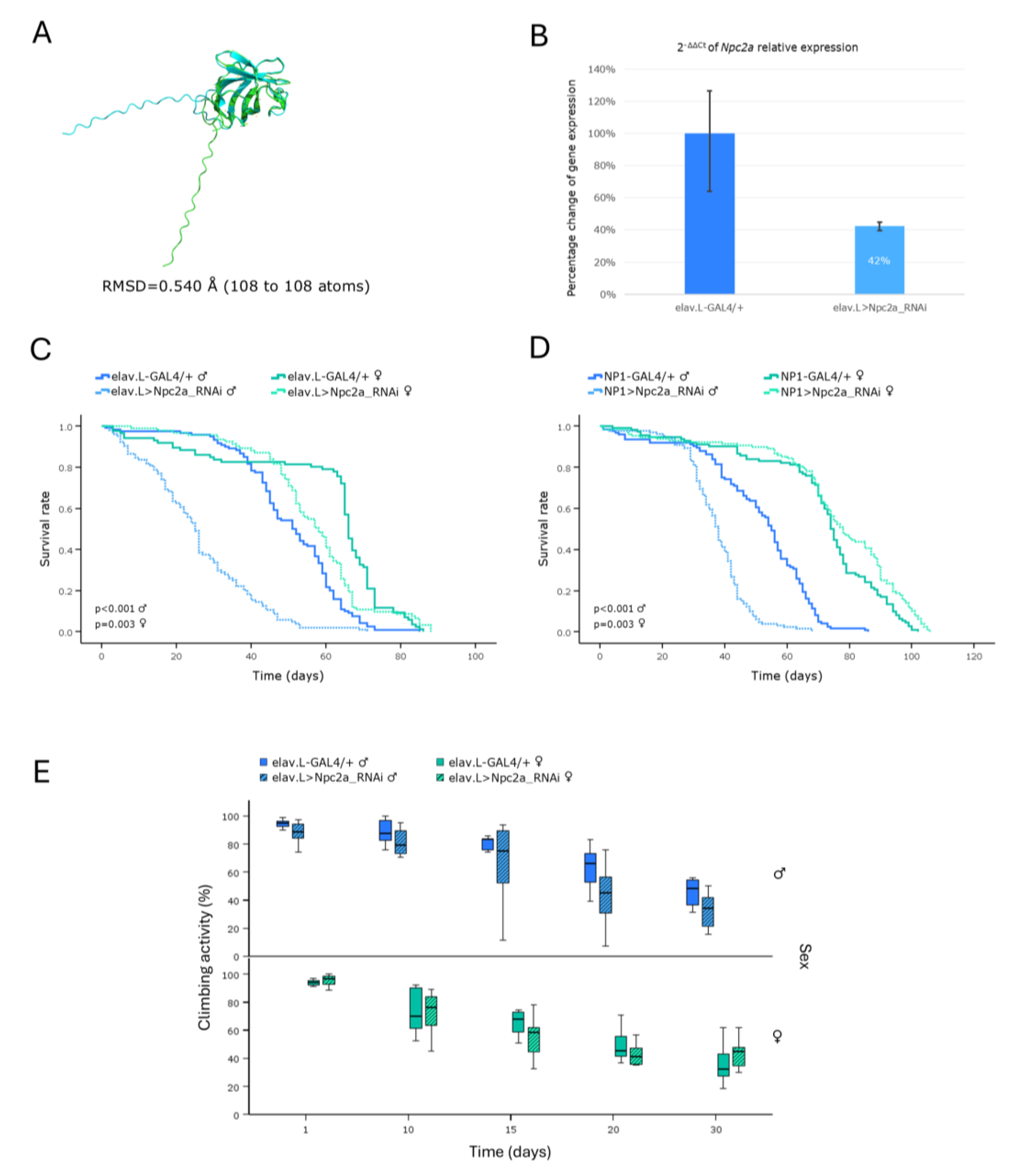

Niemann-Pick type C disease (NPC) is a neurodegenerative disorder that is sub-divided into types C1 and C2, depending on the respective -human- gene (

NPC1 or

NPC2) that is mutated. It is characterized by abnormalities in the intracellular transport of endocytosed cholesterol, which leads to the accumulation of cholesterol and sphingolipids within endo-lysosomes [

6,

12]. In the present study, we investigated the consequences of RNAi-mediated knockdown of

Drosophila Npc1a and

Npc2a gene orthologs, suitably engaging the GAL4/UAS genetic system, along the brain-midgut axis, during aging. The obtained male -transgenic- flies were characterized by reduced lifespan and locomotor dysfunction, for either organ-specific (brain, or midgut) targeting, in contrast to the female flies, which exhibited near-to-normal phenotypes.

A previous study in

Drosophila, using loss-of-function mutants of the

Npc1a gene, revealed developmental arrest at the first larval stage [

43], thus rendering age-dependent pathologies during adulthood impossible to be profiled. Strikingly, in our model, although the viability patterns for the two genes are largely similar, the relative expression of

Npc1a gene was detected less markedly reduced, compared to the

Npc2a respective one (

Figure 5B and

Figure 6B). This indicates that even a modest decrease in the

Npc1a gene-expression levels, within the nervous system (brain) setting, is sufficient to trigger a pathological phenotype, thereby highlighting the

Npc1a essential role(s) in

Drosophila well-being, during aging.

In toto, our genetic approach provides a powerful, trustworthy and manageable model system, for mechanistically illuminating and therapeutically advancing Niemann-Pick type C disease (NPC), in vivo.

GM2 gangliosidoses are characterized by excessive accumulation of ganglioside -GM2- species and related glycolipids in the lysosomes. The main forms include Tay-Sachs disease (TSD), caused by mutations in the

HEXA gene, and Sandhoff disease (SD), caused by mutations in the

HEXB gene [

9,

10,

11]. In

Drosophila, three genes (

Hexo1,

Hexo2 and

fdl) have been identified, as encoding β-Hexosaminidase-like enzymes, based on sequence homologies to human Hexosaminidases [

44,

45]. Strikingly, RNAi-mediated downregulation of the

Hexo2 (but not

Hexo1) gene, specifically in the brain, revealed a remarkable reduction in life expectancy of

Drosophila -transgenic- male flies (

Figure 7G). Given that GM2 gangliosidoses are known to predominantly affect the central nervous system (CNS) [

10,

11], our results point to the essential contribution of -certain- β-Hexosaminidases to neuronal development and CNS/brain functionality in

Drosophila, during aging, thereby validating model’s relevance to molecularly investigating GM2 gangliosidoses-induced neuro-pathologies,

in vivo.

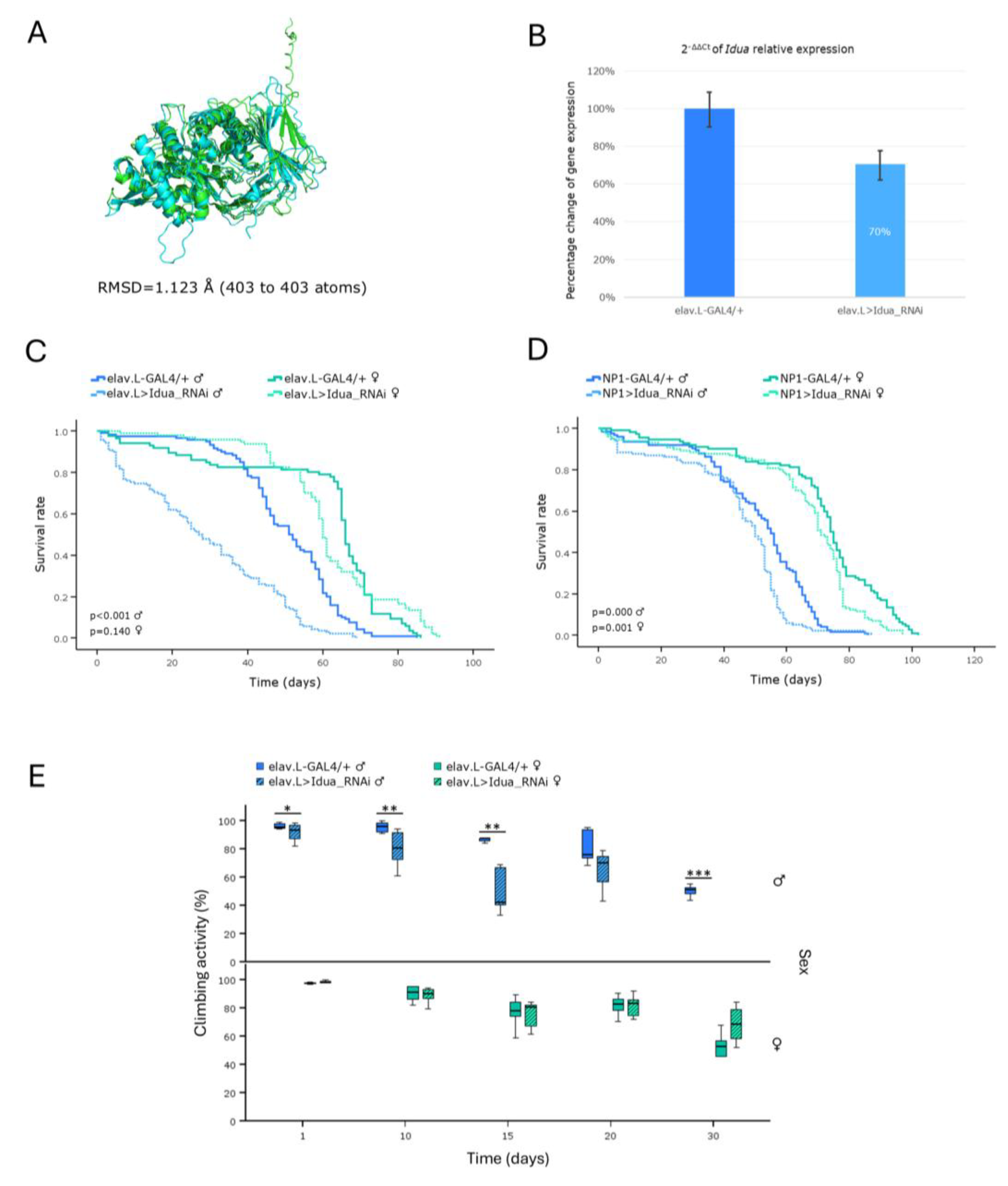

Mucopolysaccharidoses (MPSs) comprise a class of 11 lysosomal storage disorders, with each one being derived from -driver- deficiency in the activity of a distinct lysosomal hydrolase; they all belong to a family of enzymes that are critically involved in the sequential degradation of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). MPS I and MPS II sub-types were typically classified among the first syndromes identified within this group [

8]. In our Hurler syndrome (HLS) (MPS I; α-L-Iduronidase deficiency)

in vivo model, although the expression of

IDUA gene is not severely downregulated, reduced lifespan and locomotor deficiency, along the brain-midgut axis, were observed. Of note, a distinct study, regarding Hurler-syndrome (HLS) modeling, using a similar strategy, but different RNAi strains, which can still target the same

Drosophila IDUA ortholog (

CG6201) gene, has been previously reported by Filippis

et al. [

46]. However, in their set of experiments, although flies with reduced expression of the

IDUA gene, in neuronal and glial cells, were presented with locomotion deficiencies, they, unexpectedly, manifested a longer lifespan, compared to controls [

46].

Hence, our Drosophila Hurler-syndrome (HLS) model represents an invaluable, powerful, informative, constructive, manageable, novel, and, also, complementary (to the existing) -biological- tool, for genetically dissecting disease mechanisms and systemically expanding the repertoire of -experimental- in vivo models, hitherto available, to deeper investigating Hurler-syndrome (HLS) pathology, both mechanistically and therapeutically, for human’s maximum benefit.

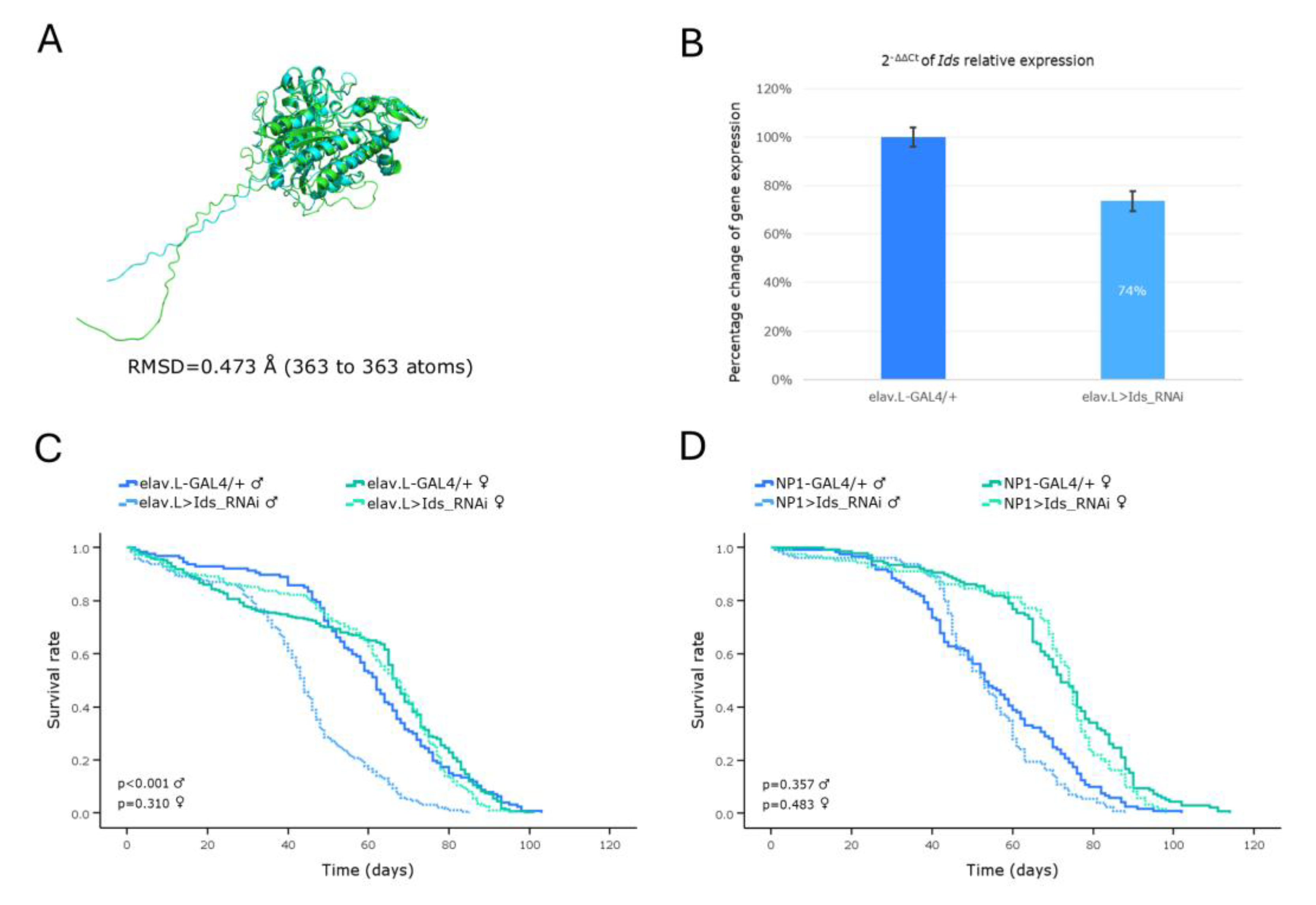

Hunter syndrome (HNS) (MPS II; Iduronate-2-sulphatase deficiency) is an X-linked recessive LSD. Remarkably, in our -invertebrate- model system, only males exhibited a notable reduction in life expectancy, a pathological phenotype that is genetically associated with the sex-dependent nature of the (HNS) disease, in humans. The genetic modeling of Hunter syndrome (HNS) in

Drosophila has been previously described, using the same (“RNAi”) strains, with the authors concluding that residual

Ids/Ids activity(ties) may be sufficient to rescue MPS II-related pathologies, since, in their lethality assays, the survival from larva to pupa and the metamorphosis to the adult phase were not affected [

47]. In contrast to their argument that engagement of RNAi-dependent -transgenic- technology for MPS II knockdown is not an effective strategy, our data strongly suggest that, under certain circumstances and specific settings, the exploitation of male flies, as a novel and reliable model system, for Hunter syndrome (HNS)-pathology research,

in vivo, should not be ignored, or disregarded.

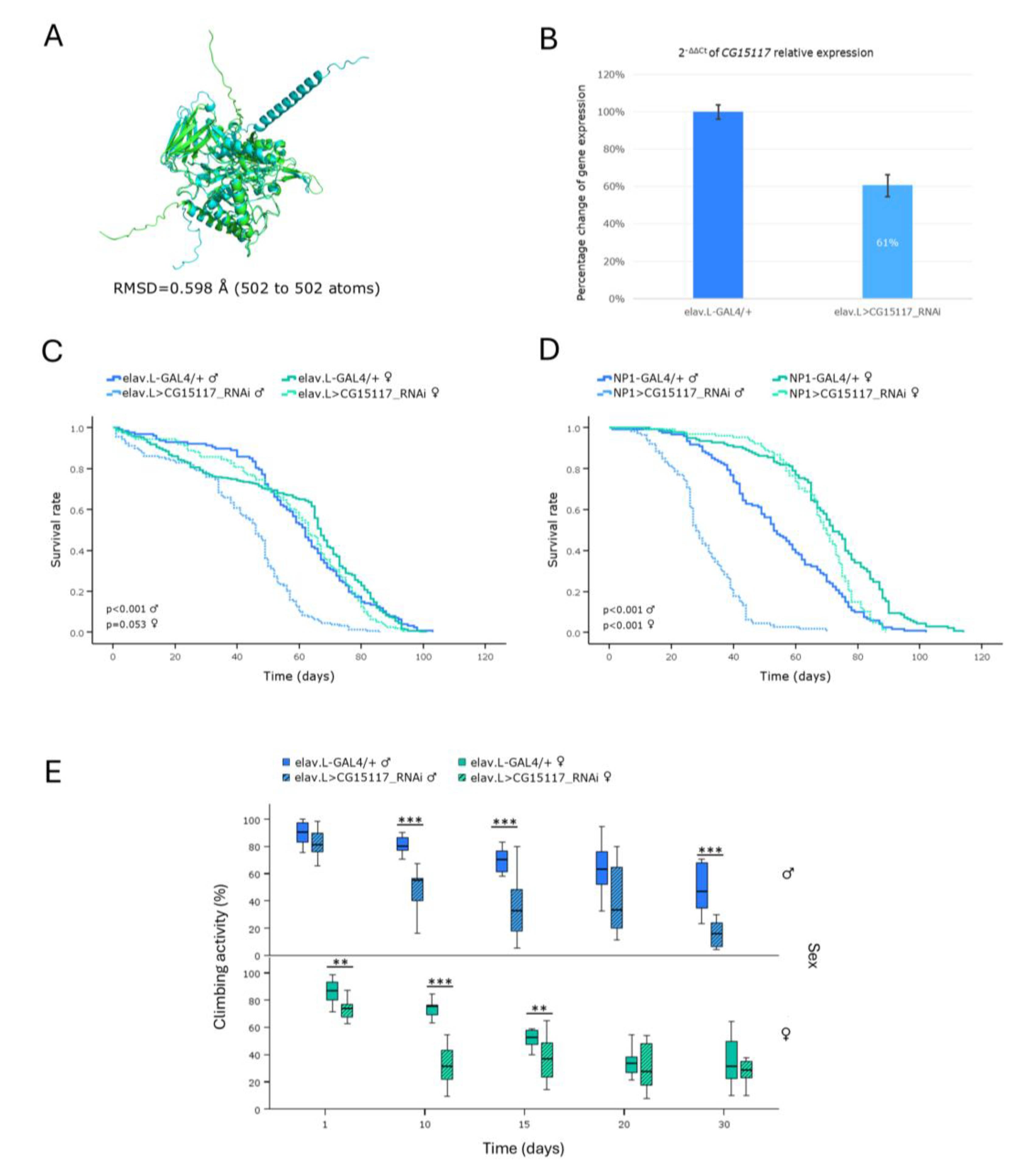

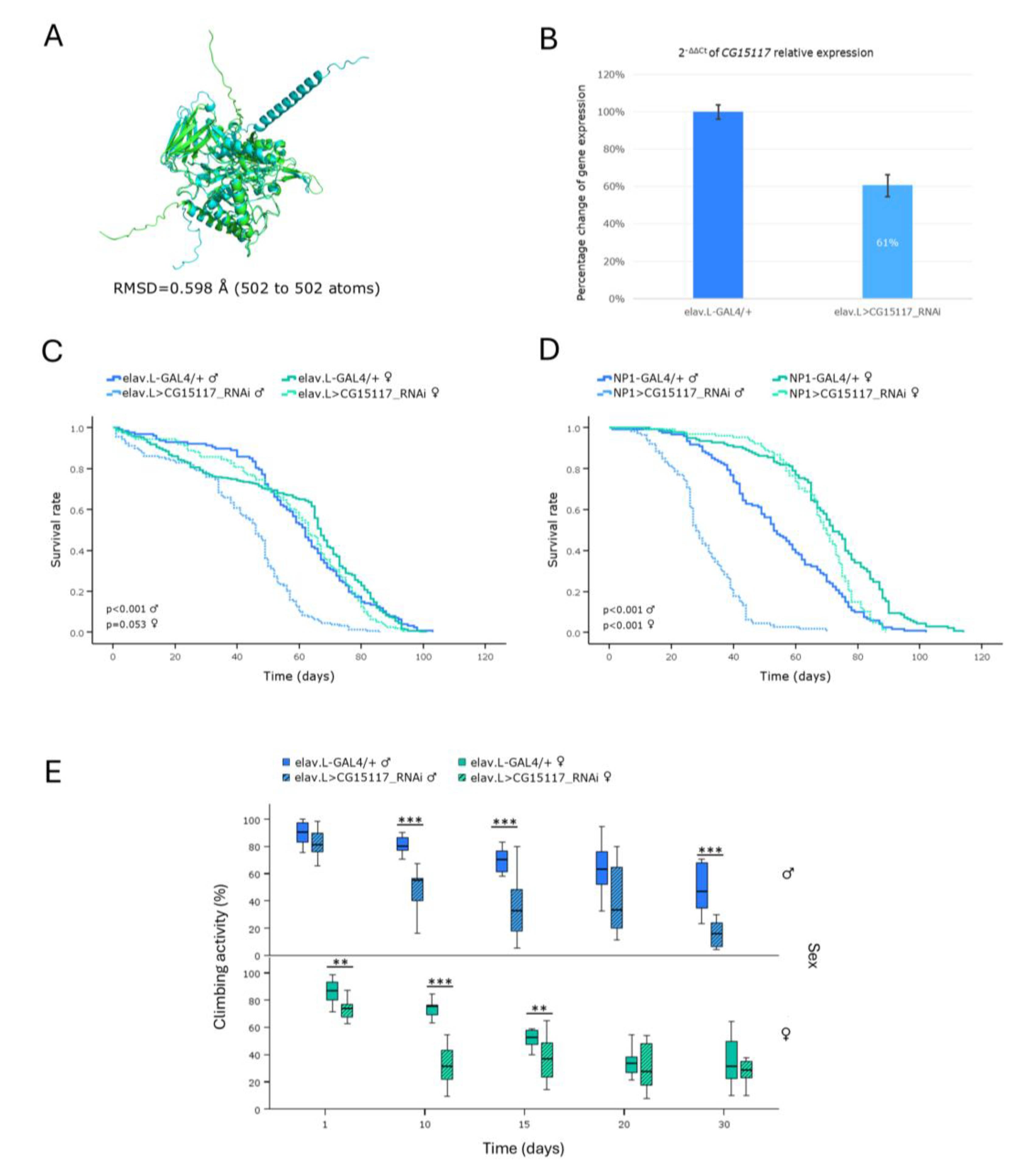

Employment of our Sly-disease (SLD) (MPS VII; β-Glucuronidase deficiency) -LSD- model demonstrated a remarkable reduction in the viability of male flies, along the brain-midgut axis, together with a progressive decline in locomotor activity for both sexes, during aging. A

Drosophila model of MPS VII, developed by knocking-out the

CG2135 gene, the fly ortholog of human

GUSB, has been previously established, by Bar

et al., successfully recapitulating key features of the Sly disease (SLD), such as shortened lifespan, motor deficiencies and neurological abnormalities [

48]. Notably,

Drosophila possesses two orthologs of the human

GUSB gene; the

CG2135 (

βGlu) and the

CG15117, with the latter exhibiting a slightly higher similarity score in DIOPT [

25]. Although Bar

et al. found that CG15117 was 6-fold less active than CG2135, our results clearly demonstrate that targeted downregulation of

CG15117, in either brain or midgut tissues, during aging, critically compromises male fly viability, thereby strongly suggesting its (

CG15117) beneficial utilization as an additional, but important and powerful, screening tool, for Sly disease (SLD) research,

in vivo.

Altogether, we have, herein, identified the Drosophila orthologs of genes that are responsible for the most common Lysosomal Storage Disorders (LSDs), in humans, and systematically screened them for “patho-phenotypic” effects on life expectancy and climbing proficiency, specifically within the brain-midgut axis, during aging, suitably engaging the GAL4/UAS -binary- transgenic system, in combination with the RNAi-mediated gene-silencing platform. Most of these, in vivo, LSD models in Drosophila, herein, proved capable to successfully recapitulate key-disease phenotypes being identified in humans, including significantly reduced lifespan and progressive climbing deficiency, which serve as proxy for neuro-muscular disintegration, in age- and sex-dependent manners.

These -consistent- phenotypic parallels undoubtedly underline the value and importance of Drosophila as a robust, reliable, powerful, rapid, multifaceted, versatile and manageable, invertebrate, model system, ideally suitable and exploitable, for high-throughput genetic and pharmacological, in vivo, screenings, aiming at pathological-phenotype(s) rescue(s), while, also, providing invaluable insights into the underlying molecular and neurological mechanisms, tightly controlling LSD-specific pathologies and therapeutic-treatment responses.

Figure 1.

In vivo genetic modeling of Gaucher disease in Drosophila, via Gba1a ortholog-gene targeting, specifically in the brain-midgut axis. (A) Structural alignment of AlphaFold-predicted protein structures being encoded by the human GBA1 gene (light green) and its Drosophila ortholog Gba1a (light cyan). The human protein structure was aligned to the Drosophila respective structure, using the PyMOL molecular graphics system. (B) Relative expression analysis of the Gba1a gene in fly neuronal (brain) tissues following its (Gba1a) RNAi-mediated knockdown (elav.L>Gba1a_RNAi), compared to control flies (elav.L-GAL4/+), as determined by real-time qPCR technology. (C) Lifespan profiling of male and female flies following Gba1a gene knockdown, specifically in the nervous system (brain). (D) Survival curves of male and female flies being subjected to Gba1a gene downregulation, specifically in midgut tissues (NP1>Gba1a_RNAi). (E) Climbing performance (negative geotaxis assay) of male and female flies with neuronal-specific (brain) Gba1a gene silencing, during aging (0-30 days, post-eclosion). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Figure 1.

In vivo genetic modeling of Gaucher disease in Drosophila, via Gba1a ortholog-gene targeting, specifically in the brain-midgut axis. (A) Structural alignment of AlphaFold-predicted protein structures being encoded by the human GBA1 gene (light green) and its Drosophila ortholog Gba1a (light cyan). The human protein structure was aligned to the Drosophila respective structure, using the PyMOL molecular graphics system. (B) Relative expression analysis of the Gba1a gene in fly neuronal (brain) tissues following its (Gba1a) RNAi-mediated knockdown (elav.L>Gba1a_RNAi), compared to control flies (elav.L-GAL4/+), as determined by real-time qPCR technology. (C) Lifespan profiling of male and female flies following Gba1a gene knockdown, specifically in the nervous system (brain). (D) Survival curves of male and female flies being subjected to Gba1a gene downregulation, specifically in midgut tissues (NP1>Gba1a_RNAi). (E) Climbing performance (negative geotaxis assay) of male and female flies with neuronal-specific (brain) Gba1a gene silencing, during aging (0-30 days, post-eclosion). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Genetic modeling of Gaucher disease in Drosophila brain-midgut axis, via Gba1b ortholog-gene targeting, in vivo. (A) Structural alignment of AlphaFold-derived protein structures being encoded by the human GBA1 gene (light green) and its Drosophila ortholog Gba1b gene (light cyan), with the human reference protein being aligned to the Drosophila one through employment of the PyMOL molecular graphics system. (B) Relative expression levels of the Gba1b gene in neuronal (brain) tissues of RNAi-targeted flies (elav.L>Gba1b_RNAi), compared to control flies (elav.L-GAL4/+), having been measured by real-time qPCR. (C) Survival curves of male and female flies, following Gba1b gene knockdown, specifically in the nervous system (brain). (D) Lifespan profiles of male and female flies after Gba1b gene silencing, specifically in midgut tissues (NP1>Gba1b_RNAi). (E) Climbing-activity (negative-geotaxis) patterns of male and female transgenic flies carrying downregulated Gba1b protein contents, specifically in the nervous system (brain), during aging (0-30 days, post-eclosion). **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Genetic modeling of Gaucher disease in Drosophila brain-midgut axis, via Gba1b ortholog-gene targeting, in vivo. (A) Structural alignment of AlphaFold-derived protein structures being encoded by the human GBA1 gene (light green) and its Drosophila ortholog Gba1b gene (light cyan), with the human reference protein being aligned to the Drosophila one through employment of the PyMOL molecular graphics system. (B) Relative expression levels of the Gba1b gene in neuronal (brain) tissues of RNAi-targeted flies (elav.L>Gba1b_RNAi), compared to control flies (elav.L-GAL4/+), having been measured by real-time qPCR. (C) Survival curves of male and female flies, following Gba1b gene knockdown, specifically in the nervous system (brain). (D) Lifespan profiles of male and female flies after Gba1b gene silencing, specifically in midgut tissues (NP1>Gba1b_RNAi). (E) Climbing-activity (negative-geotaxis) patterns of male and female transgenic flies carrying downregulated Gba1b protein contents, specifically in the nervous system (brain), during aging (0-30 days, post-eclosion). **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Figure 3.

Genetic modeling of Fabry disease in Drosophila brain-midgut axis, through targeting the CG7997 ortholog gene, in vivo. (A) PyMOL-mediated structural alignment of the AlphaFold-generated protein structure of the human GLA gene (light green) aligned to its Drosophila counterpart that is being encoded by the CG7997 ortholog (light cyan). (B) Relative expression levels of the CG7997 gene in neuronal (brain) tissues of RNAi-targeted flies (elav.L>CG7997_RNAi), compared to control (elav.L-GAL4/+) population, through engagement of the real-time qPCR technology. (C) Survival curves of flies, for both sexes, following CG7997 gene knockdown, specifically in the nervous system (brain). (D) Lifespan profiles of male and female flies, after CG7997 gene silencing, specifically in midgut tissues (NP1>CG7997_RNAi).

Figure 3.

Genetic modeling of Fabry disease in Drosophila brain-midgut axis, through targeting the CG7997 ortholog gene, in vivo. (A) PyMOL-mediated structural alignment of the AlphaFold-generated protein structure of the human GLA gene (light green) aligned to its Drosophila counterpart that is being encoded by the CG7997 ortholog (light cyan). (B) Relative expression levels of the CG7997 gene in neuronal (brain) tissues of RNAi-targeted flies (elav.L>CG7997_RNAi), compared to control (elav.L-GAL4/+) population, through engagement of the real-time qPCR technology. (C) Survival curves of flies, for both sexes, following CG7997 gene knockdown, specifically in the nervous system (brain). (D) Lifespan profiles of male and female flies, after CG7997 gene silencing, specifically in midgut tissues (NP1>CG7997_RNAi).

Figure 4.

In vivo genetic modeling of Fabry disease in Drosophila, via RNAi-mediated targeting of CG5731 ortholog gene, in the brain-midgut axis, during aging. (A) Structural alignment of AlphaFold-derived protein structures of human GLA (light green) and its Drosophila ortholog CG5731 (light cyan), having been generated and visualized using the PyMOL molecular graphics system. The human reference sequence (GLA) is aligned to the Drosophila protein (CG5731). (B) Quantitative analysis of CG5731 mRNA levels in neuronal (brain) tissues of CG5731RNAi-expressing flies (elav.L>CG5731_RNAi), relatively to control (elav.L-GAL4/+), using real-time qPCR technology. (C) Survival curves of male and female flies, following nervous system (brain)-specific silencing of the CG5731 gene. (D) Viability profiles of flies being characterized by targeted CG5731 knockdown, specifically in midgut tissues (NP1>CG5731_RNAi) (compared to control). (E) Negative-geotaxis (climbing-activity) assay, during aging (0-30 days, post-eclosion), demonstrating progressive locomotor decline in flies with neuronal (brain)-specific CG5731 downregulation, compared to control fly population. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Figure 4.

In vivo genetic modeling of Fabry disease in Drosophila, via RNAi-mediated targeting of CG5731 ortholog gene, in the brain-midgut axis, during aging. (A) Structural alignment of AlphaFold-derived protein structures of human GLA (light green) and its Drosophila ortholog CG5731 (light cyan), having been generated and visualized using the PyMOL molecular graphics system. The human reference sequence (GLA) is aligned to the Drosophila protein (CG5731). (B) Quantitative analysis of CG5731 mRNA levels in neuronal (brain) tissues of CG5731RNAi-expressing flies (elav.L>CG5731_RNAi), relatively to control (elav.L-GAL4/+), using real-time qPCR technology. (C) Survival curves of male and female flies, following nervous system (brain)-specific silencing of the CG5731 gene. (D) Viability profiles of flies being characterized by targeted CG5731 knockdown, specifically in midgut tissues (NP1>CG5731_RNAi) (compared to control). (E) Negative-geotaxis (climbing-activity) assay, during aging (0-30 days, post-eclosion), demonstrating progressive locomotor decline in flies with neuronal (brain)-specific CG5731 downregulation, compared to control fly population. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Figure 5.

In vivo genetic modeling of the Niemann-Pick disease type C1 in Drosophila, through targeting of the Npc1a ortholog gene, in the brain-midgut axis, during aging. (A) Structural alignment of AlphaFold-derived protein structures of the human NPC1 (light green) and its Drosophila ortholog Npc1a (light cyan) genes, being generated and visualized via engagement of the PyMOL molecular graphics system. (B) Relative expression of the Npc1a gene in neuronal (brain) tissues of RNAi-targeted flies (elav.L>Npc1a_RNAi), compared to control population (elav.L-GAL4/+), being quantified by real-time qPCR technology. (C) Survival curves of male and female -transgenic- flies, following Npc1a gene targeting, specifically in the nervous system (brain). (D) Lifespan profiles of flies that are being typified by midgut-specific Npc1a gene silencing (NP1>Npc1a_RNAi). (E) Climbing activity (negative geotaxis) of -transgenic- flies with Npc1a gene downregulation, specifically in the nervous system (brain), indicating severe and progressive locomotor decline in Drosophila male populations, during aging (0-30 days, post-eclosion). **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Figure 5.

In vivo genetic modeling of the Niemann-Pick disease type C1 in Drosophila, through targeting of the Npc1a ortholog gene, in the brain-midgut axis, during aging. (A) Structural alignment of AlphaFold-derived protein structures of the human NPC1 (light green) and its Drosophila ortholog Npc1a (light cyan) genes, being generated and visualized via engagement of the PyMOL molecular graphics system. (B) Relative expression of the Npc1a gene in neuronal (brain) tissues of RNAi-targeted flies (elav.L>Npc1a_RNAi), compared to control population (elav.L-GAL4/+), being quantified by real-time qPCR technology. (C) Survival curves of male and female -transgenic- flies, following Npc1a gene targeting, specifically in the nervous system (brain). (D) Lifespan profiles of flies that are being typified by midgut-specific Npc1a gene silencing (NP1>Npc1a_RNAi). (E) Climbing activity (negative geotaxis) of -transgenic- flies with Npc1a gene downregulation, specifically in the nervous system (brain), indicating severe and progressive locomotor decline in Drosophila male populations, during aging (0-30 days, post-eclosion). **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Figure 6.

In vivo genetic modeling of the Niemann-Pick disease type C2 in Drosophila, through targeting of the Npc2a ortholog gene, in the brain-midgut axis, during aging. (A) Structural alignment of AlphaFold-derived protein structures of the human NPC2 (light green) and its Drosophila ortholog Npc2a (light cyan) genes, with the human reference sequence (NPC2) being aligned to the Drosophila protein (Npc2a), using the PyMOL molecular graphics system. (B) Relative expression of the Npc2a gene in neuronal (brain) tissues of RNAi-targeted flies (elav.L>Npc2a_RNAi), versus control population (elav.L-GAL4/+), as examined and quantified by real-time qPCR. (C) Lifespan curves of male and female -transgenic- flies being characterized by Npc2a gene downregulation, specifically in the nervous system (brain), compared to control population. (D) Survival profiles, after midgut-specific knockdown of the Npc2a ortholog gene (NP1>Npc2a_RNAi), compared to control (NP1-GAL4/+). (E) Negative-geotaxis (climbing-activity) assay of flies with neuronal (brain)-specific Npc2a gene knockdown, presenting an unimpaired (physiological), age-dependent, decline in motor function(s), compared to controls.

Figure 6.

In vivo genetic modeling of the Niemann-Pick disease type C2 in Drosophila, through targeting of the Npc2a ortholog gene, in the brain-midgut axis, during aging. (A) Structural alignment of AlphaFold-derived protein structures of the human NPC2 (light green) and its Drosophila ortholog Npc2a (light cyan) genes, with the human reference sequence (NPC2) being aligned to the Drosophila protein (Npc2a), using the PyMOL molecular graphics system. (B) Relative expression of the Npc2a gene in neuronal (brain) tissues of RNAi-targeted flies (elav.L>Npc2a_RNAi), versus control population (elav.L-GAL4/+), as examined and quantified by real-time qPCR. (C) Lifespan curves of male and female -transgenic- flies being characterized by Npc2a gene downregulation, specifically in the nervous system (brain), compared to control population. (D) Survival profiles, after midgut-specific knockdown of the Npc2a ortholog gene (NP1>Npc2a_RNAi), compared to control (NP1-GAL4/+). (E) Negative-geotaxis (climbing-activity) assay of flies with neuronal (brain)-specific Npc2a gene knockdown, presenting an unimpaired (physiological), age-dependent, decline in motor function(s), compared to controls.

Figure 7.

Genetic modeling of Tay-Sachs and Sandhoff diseases, via targeting their Drosophila ortholog genes, in the brain-midgut axis, during aging, in vivo. (A-D) Functional analysis of Hexo1 gene: (A) Alignment of AlphaFold-derived molecular structures of the proteins produced by human HEXA and HEXB genes (light green) with their Drosophila ortholog protein being encoded by the Hexo1 gene (light cyan), using the PyMOL molecular graphics system. (B) Relative expression levels of the Hexo1 gene in neuronal (brain) tissues of RNAi-targeted flies (elav.L>Hexo1_RNAi), compared to controls (elav.L-GAL4/+), as measured and quantified by real-time qPCR technology. (C) Survival curves of -transgenic- male and female flies, following nervous system (brain)-specific knockdown of Hexo1 gene, compared to controls. (D) Lifespan profiles, after Hexo1-gene knockdown, specifically in midgut tissues (NP1>Hexo1_RNAi), compared to control (NP1-GAL4/+). (E-H) Functional analysis of Hexo2 gene: (E) Structural alignment of AlphaFold-predicted protein structures being derived from human HEXA and HEXB genes (light green), and the Drosophila ortholog protein synthesized by the Hexo2 gene (light cyan). (F) Relative expression levels of Hexo2 gene in transgenic flies over-expressing the Hexo2RNAi species, specifically in the nervous system (brain) (elav.L>Hexo2_RNAi), versus control populations (elav.L-GAL4/+), via real-time qPCR technology employment. (G) Survival curves of male and female flies being characterized by (pan-)neuronal Hexo2 knockdown, compared to control conditions. (H) Lifespan profiles, after Hexo2-gene silencing, specifically in the midgut tissues (NP1>Hexo2_RNAi), compared to control (NP1-GAL4/+).

Figure 7.

Genetic modeling of Tay-Sachs and Sandhoff diseases, via targeting their Drosophila ortholog genes, in the brain-midgut axis, during aging, in vivo. (A-D) Functional analysis of Hexo1 gene: (A) Alignment of AlphaFold-derived molecular structures of the proteins produced by human HEXA and HEXB genes (light green) with their Drosophila ortholog protein being encoded by the Hexo1 gene (light cyan), using the PyMOL molecular graphics system. (B) Relative expression levels of the Hexo1 gene in neuronal (brain) tissues of RNAi-targeted flies (elav.L>Hexo1_RNAi), compared to controls (elav.L-GAL4/+), as measured and quantified by real-time qPCR technology. (C) Survival curves of -transgenic- male and female flies, following nervous system (brain)-specific knockdown of Hexo1 gene, compared to controls. (D) Lifespan profiles, after Hexo1-gene knockdown, specifically in midgut tissues (NP1>Hexo1_RNAi), compared to control (NP1-GAL4/+). (E-H) Functional analysis of Hexo2 gene: (E) Structural alignment of AlphaFold-predicted protein structures being derived from human HEXA and HEXB genes (light green), and the Drosophila ortholog protein synthesized by the Hexo2 gene (light cyan). (F) Relative expression levels of Hexo2 gene in transgenic flies over-expressing the Hexo2RNAi species, specifically in the nervous system (brain) (elav.L>Hexo2_RNAi), versus control populations (elav.L-GAL4/+), via real-time qPCR technology employment. (G) Survival curves of male and female flies being characterized by (pan-)neuronal Hexo2 knockdown, compared to control conditions. (H) Lifespan profiles, after Hexo2-gene silencing, specifically in the midgut tissues (NP1>Hexo2_RNAi), compared to control (NP1-GAL4/+).

Figure 8.

Modeling of Pompe disease-related orthologs in Drosophila brain-midgut axis, during aging. (A-D) Functional analysis of the GCS2alpha gene: (A) Structural alignment of AlphaFold-derived, superimposed, protein products of the human GAA (light green) and the Drosophila ortholog GCS2alpha (light cyan) genes, being generated and visualized using the PyMOL molecular graphics system. (B) Relative (endogenous) GCS2alpha mRNA expression levels in neuronal (brain) tissues of RNAi-targeted flies (elav.L>GCS2alpha_RNAi), compared to controls (elav.L-GAL4/+), measured and quantified by real-time qPCR. (C) Survival curves of male and female flies, following (pan-)neuronal GCS2alpha-gene knockdown, versus control conditions. (D) Lifespan profiling, after GCS2alpha-targeted downregulation, specifically in Drosophila midgut tissues (NP1>GCS2alpha_RNAi), compared to control (NP1-GAL4/+). (E-H) Functional analysis of the tobi gene: (E) Structural alignment of AlphaFold-derived, superimposed, protein products of the human GAA (light green) and the Drosophila ortholog tobi (light cyan) genes, via PyMOL engagement. (F) Relative (endogenous) tobi mRNA expression levels in neuronal (brain) tissues, after specific downregulation of tobi gene in the nervous system (brain) (elav.L>tobi_RNAi), versus control fly population (elav.L-GAL4/+), via real-time qPCR platform engagement. (G) Survival curves of male and female flies, being characterized by nervous system (brain)-specific tobi-gene knockdown, compared to control conditions. (H) Viability profiles of, male and female, transgenic flies, after tobi-gene silencing, specifically in Drosophila midgut tissues (NP1>tobi_RNAi), versus control, respective, genetic crosses (NP1-GAL4/+).

Figure 8.

Modeling of Pompe disease-related orthologs in Drosophila brain-midgut axis, during aging. (A-D) Functional analysis of the GCS2alpha gene: (A) Structural alignment of AlphaFold-derived, superimposed, protein products of the human GAA (light green) and the Drosophila ortholog GCS2alpha (light cyan) genes, being generated and visualized using the PyMOL molecular graphics system. (B) Relative (endogenous) GCS2alpha mRNA expression levels in neuronal (brain) tissues of RNAi-targeted flies (elav.L>GCS2alpha_RNAi), compared to controls (elav.L-GAL4/+), measured and quantified by real-time qPCR. (C) Survival curves of male and female flies, following (pan-)neuronal GCS2alpha-gene knockdown, versus control conditions. (D) Lifespan profiling, after GCS2alpha-targeted downregulation, specifically in Drosophila midgut tissues (NP1>GCS2alpha_RNAi), compared to control (NP1-GAL4/+). (E-H) Functional analysis of the tobi gene: (E) Structural alignment of AlphaFold-derived, superimposed, protein products of the human GAA (light green) and the Drosophila ortholog tobi (light cyan) genes, via PyMOL engagement. (F) Relative (endogenous) tobi mRNA expression levels in neuronal (brain) tissues, after specific downregulation of tobi gene in the nervous system (brain) (elav.L>tobi_RNAi), versus control fly population (elav.L-GAL4/+), via real-time qPCR platform engagement. (G) Survival curves of male and female flies, being characterized by nervous system (brain)-specific tobi-gene knockdown, compared to control conditions. (H) Viability profiles of, male and female, transgenic flies, after tobi-gene silencing, specifically in Drosophila midgut tissues (NP1>tobi_RNAi), versus control, respective, genetic crosses (NP1-GAL4/+).

Figure 9.

In vivo genetic modeling of Hurler syndrome in Drosophila, via the Idua ortholog gene targeting, in the brain-midgut axis, during aging. (A) Structural alignment of AlphaFold-derived protein, superimposed, structures being encoded by the human IDUA (light green) and its Drosophila ortholog Idua (light cyan) -respective- genes, generated and visualized via the PyMOL molecular graphics system. (B) Relative expression levels of the Idua gene in neuronal (brain) tissues of RNAi-targeted flies (elav.L>Idua_RNAi), versus control ones (elav.L-GAL4/+), suitably quantified via the real-time qPCR technology engagement. (C) Survival curves of male and female, transgenic, flies, following Idua gene downregulation, specifically, in the nervous system (brain), compared to controls. (D) Viability profiles, after midgut-specific silencing of the Idua gene (NP1>Idua_RNAi), versus control conditions (NP1-GAL4/+). (E) Climbing performance of flies with neuronal (brain)-specific knockdown of the Idua gene (elav.L>Idua_RNAi), compared to control genetic crosses (elav.L-GAL4/+). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Figure 9.

In vivo genetic modeling of Hurler syndrome in Drosophila, via the Idua ortholog gene targeting, in the brain-midgut axis, during aging. (A) Structural alignment of AlphaFold-derived protein, superimposed, structures being encoded by the human IDUA (light green) and its Drosophila ortholog Idua (light cyan) -respective- genes, generated and visualized via the PyMOL molecular graphics system. (B) Relative expression levels of the Idua gene in neuronal (brain) tissues of RNAi-targeted flies (elav.L>Idua_RNAi), versus control ones (elav.L-GAL4/+), suitably quantified via the real-time qPCR technology engagement. (C) Survival curves of male and female, transgenic, flies, following Idua gene downregulation, specifically, in the nervous system (brain), compared to controls. (D) Viability profiles, after midgut-specific silencing of the Idua gene (NP1>Idua_RNAi), versus control conditions (NP1-GAL4/+). (E) Climbing performance of flies with neuronal (brain)-specific knockdown of the Idua gene (elav.L>Idua_RNAi), compared to control genetic crosses (elav.L-GAL4/+). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Figure 10.

In vivo genetic modeling of Hunter syndrome in Drosophila: RNAi-mediated targeting of the Ids ortholog gene, in the brain-midgut axis, during aging. (A) Structural alignment of the AlphaFold-predicted, superimposed, protein structures being derived from the human IDS (light green) and its Drosophila ortholog Ids (light cyan) genes. Human protein was aligned to the Drosophila structure, using the PyMOL molecular graphics system. (B) Relative expression levels of the (endogenous) Ids gene, specifically, in neuronal (brain) tissues of RNAi-targeted flies (elav.L>Ids_RNAi), compared to controls (elav.L-GAL4/+), suitably quantified by real-time qPCR technology. (C) Survival curves of transgenic flies from both sexes, following Ids gene knockdown, specifically, in the nervous system (brain) (elav.L>Ids_RNAi), versus control conditions (elav.L-GAL4/+). (D) Lifespan profiles of male and female -transgenic- flies, after Ids gene silencing, specifically, in midgut tissues (NP1>Ids_RNAi), compared to control genetic crosses (NP1-GAL4/+).

Figure 10.

In vivo genetic modeling of Hunter syndrome in Drosophila: RNAi-mediated targeting of the Ids ortholog gene, in the brain-midgut axis, during aging. (A) Structural alignment of the AlphaFold-predicted, superimposed, protein structures being derived from the human IDS (light green) and its Drosophila ortholog Ids (light cyan) genes. Human protein was aligned to the Drosophila structure, using the PyMOL molecular graphics system. (B) Relative expression levels of the (endogenous) Ids gene, specifically, in neuronal (brain) tissues of RNAi-targeted flies (elav.L>Ids_RNAi), compared to controls (elav.L-GAL4/+), suitably quantified by real-time qPCR technology. (C) Survival curves of transgenic flies from both sexes, following Ids gene knockdown, specifically, in the nervous system (brain) (elav.L>Ids_RNAi), versus control conditions (elav.L-GAL4/+). (D) Lifespan profiles of male and female -transgenic- flies, after Ids gene silencing, specifically, in midgut tissues (NP1>Ids_RNAi), compared to control genetic crosses (NP1-GAL4/+).

Figure 11.

In vivo genetic modeling of Sly disease in Drosophila, via the CG15117 ortholog gene targeting, in the brain-gut axis, during aging. (A) Structural alignment of AlphaFold-derived, superimposed, protein structures being encoded by the human GUSB (light green) and its Drosophila ortholog CG15117 (light cyan) genes, generated and visualized using the PyMOL molecular graphics system. (B) Quantitative analysis of the CG15117 mRNA levels, specifically, in neuronal (brain) tissues of CG15117RNAi-(over-)expressing flies (elav.L>CG15117_RNAi), compared to controls (elav.L-GAL4/+), via the real-time qPCR technology engagement. (C) Lifespan curves of male and female -transgenic- flies, following nervous system (brain)-specific targeting of the CG15117 gene (elav.L>CG15117_RNAi), compared to control conditions (elav.L-GAL4/+). (D) Survival profiles of transgenic flies (both sexes) with targeted CG15117-gene knockdown, specifically, in midgut tissues (NP1> CG15117_RNAi), compared to control genetic crosses (NP1-GAL4/+). (E) Climbing performance of transgenic flies with neuronal (brain)-specific CG15117-gene downregulation (elav.L>CG15117_RNAi), versus control genetic settings (elav.L-GAL4/+), measured and quantified over time (0-30 days, post-eclosion) (using the negative-geotaxis assay), demonstrating the progressive, age- and sex-dependent, impairment in motor function(s). **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Figure 11.

In vivo genetic modeling of Sly disease in Drosophila, via the CG15117 ortholog gene targeting, in the brain-gut axis, during aging. (A) Structural alignment of AlphaFold-derived, superimposed, protein structures being encoded by the human GUSB (light green) and its Drosophila ortholog CG15117 (light cyan) genes, generated and visualized using the PyMOL molecular graphics system. (B) Quantitative analysis of the CG15117 mRNA levels, specifically, in neuronal (brain) tissues of CG15117RNAi-(over-)expressing flies (elav.L>CG15117_RNAi), compared to controls (elav.L-GAL4/+), via the real-time qPCR technology engagement. (C) Lifespan curves of male and female -transgenic- flies, following nervous system (brain)-specific targeting of the CG15117 gene (elav.L>CG15117_RNAi), compared to control conditions (elav.L-GAL4/+). (D) Survival profiles of transgenic flies (both sexes) with targeted CG15117-gene knockdown, specifically, in midgut tissues (NP1> CG15117_RNAi), compared to control genetic crosses (NP1-GAL4/+). (E) Climbing performance of transgenic flies with neuronal (brain)-specific CG15117-gene downregulation (elav.L>CG15117_RNAi), versus control genetic settings (elav.L-GAL4/+), measured and quantified over time (0-30 days, post-eclosion) (using the negative-geotaxis assay), demonstrating the progressive, age- and sex-dependent, impairment in motor function(s). **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Table 1.

Drosophila orthologs of human Lysosomal Storage Disorder (LSD)–associated genes identified via DIOPT.

Table 1.

Drosophila orthologs of human Lysosomal Storage Disorder (LSD)–associated genes identified via DIOPT.

Lysosomal Storage Disorders

(LSDs)

|

Human Gene

|

Protein Name |

DrosophilaOrtholog

|

Homology

(Rank)

(DIOPTScore)

|

RNAi Strain |

|

| 1. Autosomal recessive spastic paraplegia type 48 (SPG48) |

AP5Z1 |

Adaptor-related protein complex 5 subunit zeta 1 |

Lpin / CG8709

|

Low

(1) |

636141

|

|

| 771701

|

|

| 2. Disorders of lysosomal amino acid transport |

|

|

| A. Cystinosis |

CTNS |

Cystinosin, Lysosomal Cystine transporter |

Ctns / CG17119

|

High

(16) |

408231

|

|

| B. Free sialic acid storage disease (free SASD) |

|

|

| a) Salla disease (SD) |

SLC17A5 |

Sialin, Solute carrier

family 17 member 5 |

VGlut2 / MFS9 / CG4288

|

High

(10) |

293051

|

|

b) Intermediate severity Salla

disease |

v1041452

|

|

c) Infatile free sialic acid storage

disease (ISSD) |

|

|

| 3. Disorders of sialic acid metabolism |

|

|

| Sialuria |

GNE |

Glucosamine (UDP-N-acetyl)-2-epimerase / N-Acetyl-mannosamine kinase |

- |

- |

- |

|

| 4. Glycoproteinoses |

|

|

| A. Mucolipidoses (ML) |

|

|

a) ML type II α/β: Inclusion (I)-

cell disease |

GNPTAB |

N-Acetyl-glucosamine-1-phosphotransferase

subunits α/β |

Gnptab / CG8027

|

High

(15) |

v1094002

|

|

b) ML type III: Pseudo-Hurler

polydystrophy: |

|

|

| type III α/β |

GNPTG |

N-Acetyl-glucosamine-1-phosphotransferase

subunit γ |

GCS2beta / CG6453

|

Moderate

(3) |

350081

|

|

| type III γ |

CG7685 |

Low

(2) |

622541

|

|

| c) ML type IV: Sialolipidosis |

MCOLN1 |

Mucolipin 1, Mucolipin transient receptor potencial (TRP) cation channel 1 |

CG42638 |

Moderate

(14) |

440981

|

|

|

Trpml / CG8743

|

Moderate

(14) |

312941

|

|

| 316731

|

|

| v1080882

|

|

| v459892

|

|

| B. Oligosaccharidoses |

|

|

| a) α-Mannosidosis |

MAN2B1 |

Lysosomal α-Mannosidase, Mannosidase alpha class 2B member 1 |

LManII / CG6206

|

High

(16) |

532941

|

|

|

LManI / CG5322

|

Moderate

(14) |

444731

|

|

|

LManV / CG9466

|

Moderate

(14) |

v1043002

|

|

| v130402

|

|

|

LManIV / CG9465

|

Moderate

(14) |

669921

|

|

|

LManIII / CG9463

|

Moderate

(13) |

v155892

|

|

| v480632

|

|

|

LManVI / CG9468

|

Moderate

(12) |

612161

|

|

|

alpha-Man-IIa / CG18802

|

Low

(3) |

v58382

|

|

|

alpha-Man-IIb / CG4606

|

Low

(2) |

v1080432

|

|

| v426522

|

|

| b) β-Mannosidosis |

MANBA |

β-Mannosidase |

beta-Man / CG12582

|

High

(14) |

532721

|

|

| c) Fucosidosis |

FUCA1 |

α-L-Fucosidase 1 |

Fuca / CG6128

|

High

(13) |

- |

|

d) Aspartyglucosaminuria

(AGU) |

AGA |

Aspartylglucosaminidase |

CG1827 |

High

(14) |

651411

|

|

| CG10474 |

High

(14) |

514441

|

|

| CG4372 |

Moderate

(8) |

v364312

|

|

| CG7860 |

Low

(2) |

v1082812

|

|

| v343942

|

|

|

Tasp1 / CG5241

|

Low

(2) |

649071

|

|

e) α-Ν-Acetyl-

galactosaminidase deficiency

(NAGA deficiency): Schindler

disease: |

|

|

type I: Infantile onset

Neuroaxonal dystrophy |

NAGA |

α-N-Acetyl-galactosaminidase |

CG5731 |

High

(16) |

670251

|

|

| type II: Kanzaki disease |

CG7997 |

Moderate

(15) |

636551

|

|

| type III: Intermediate severity |

577811

|

|

f) Galactosialidosis:

Goldberg syndrome |

CTSA |

Protective protein Cathepsin A, and a secondary deficiency in β-Galactosidase and Neuraminidase-1 |

CG4572 |

Moderate

(4) |

343371

|

|

| CG32483 |

Low

(2) |

v1062632

|

|

| v229762

|

|

|

hiro / CG3344

|

Low

(2) |

v1104022

|

|

| v152132

|

|

| CG31821 |

Low

(2) |

v1060592

|

|

| v154962

|

|

| CG31823 |

Low

(2) |

669411

|

|

| 670271

|

|

| g) Sialidosis: |

|

|

type I (ST-1): Cherry-red spot-

myoclonus syndrome |

NEU1 |

Neuraminidase-1, Lysosomal Sialidase |

- |

- |

- |

|

| type II (ST-2): Mucolipidosis I |

|

5. Lysosomal acid phosphatase

deficiency |

|

|

6. Glycogen storage disease(s)

[GSD(s)] |

|

|

GSD type II (due to acid maltase

deficiency): Pompe disease |

GAA |

Lysosomal α-Glucosidase, Acid maltase |

GCS2alpha / CG14476

|

Moderate

(5) |

343341

|

|

|

tobi / CG11909

|

Low

(3) |

533791

|

|

| CG33080 |

Low

(2) |

425541

|

|

GSD due to LAMP-2 deficiency:

Danon disease |

LAMP2 |

Lysosomal-associated membrane protein 2 |

Lamp1 / CG3305

|

Moderate

(8) |

383351

|

|

| 382541

|

|

| CG32225 |

Low

(3) |

v1023452

|

|

| v53832

|

|

| 7. Mucopolysaccharidoses (MPSs) |

|

|

| MPS I: |

|

|

| Hurler syndrome (MPSIH) |

IDUA |

α-L-Iduronidase |

Idua / CG6201

|

High

(14) |

649311

|

|

Hurler-Scheie syndrome

(MPSIH/S) |

|

| Scheie syndrome (MPSIS) |

|

| MPS II: Hunter syndrome |

|

|

| type A (MPSIIA), severe form |

IDS |

Iduronate 2-sulfatase |

Ids / CG12014

|

High

(18) |

519011

|

|

| type B (MPSIIB), attenuated form |

630041

|

|

| MPS III: Sanfilippo syndrome: |

|

|

| type A (MPSIIIA) |

SGSH |

N-Sulfoglucosamine sulfohydrolase |

Sgsh / CG14291

|

High

(16) |

v1073842

|

|

| v168972

|

|

| type B (MPSIIIB) |

NAGLU |

N-Acetyl-α-glucosaminidase |

Naglu / CG13397

|

High

(17) |

518081

|

|

| type C (MPSIIIC) |

HGSNAT |

Heparan-α-glucosaminide N-acetyltransferase |

Hgsnat / CG6903

|

High

(15) |

334231

|

|

| type D (MPSIIID) |

GNS |

N-Acetylglucosamine-6-sulfatase |

Gns / CG18278 |

High

(15) |

285201

|

|

| 518781

|

|

| v1099442

|

|

| v229362

|

|

| MPS IV: Morquio syndrome: |

|

|

| type A (MPSIVA) |

GALNS |

N-Acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfatase |

CG7408 |

Moderate

(3) |

653591

|

|

|

Gns / CG18278

|

Moderate

(3) |

285201

|

|

| 518781

|

|

| CG7402 |

Moderate

(3) |

v1039472

|

|

| v373022

|

|

| CG32191 |

Moderate

(3) |

v1015782

|

|

| v142942

|

|

| type B (MPSIVB) |

GLB1 |

β-Galactosidase 1 |

Ect3 / CG3132

|

Moderate

(15) |

622171

|

|

|

Gal / CG9092

|

Moderate

(14) |

429221

|

|

| 506801

|

|

MPS VI: Maroteaux-Lamy

syndrome |

ARSB |

Arylsulfatase B |

CG7402 |

High

(13) |

v1039472

|

|

| v373022

|

|

| MPS VII: Sly disease |

GUSB |

β-Glucuronidase |

CG15117 |

High

(17) |

336931

|

|

|

beta-Glu / CG2135

|

Moderate

(15) |

622361

|

|

|

beta-Man / CG12582

|

Low

(2) |

532721

|

|

MPS IX: Hyaluronidase

deficiency |

HYAL1 |

Hyaluronidase 1 |

- |

- |

- |

|

| 8. Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses (NCL): Batten disease |

|

|

CLN1: Haltia-Santavuori disease

/ Hagberg-Santavuori disease /

Santavuori disease (INCL) |

PPT1 |

Palmitoyl-protein thioesterase 1 |

Ppt1 / CG12108

|

High

(14) |

553311

|

|

| 622911

|

|

| 259521

|

|

|

Ppt2 / CG4851

|

Low

(3) |

283621

|

|

| v1068192

|

|

| v14592

|

|

CLN2: Jansky-Bielschowsky

disease (LINCL) |

TPP1 |

Tripeptidyl peptidase 1 |

- |

- |

- |

|

CLN3: Batten-Spielmeyer-

Sjogren disease (JNCL) |

CLN3 |

Battenin, Endosomal transmembrane protein |

Cln3 / CG5582

|

High

(14) |

357341

|

|

CLN4: Parry disease / Kufs

disease type A and B (ANCL) |

DNAJC5 |

Cysteine string protein, DnaJ Heat shock protein family (Hsp40) member C5 |

Csp / CG6395

|

High

(14) |

336451

|

|

| 312901

|

|

| 316691

|

|

| CG7130 |

Low

(2) |

578541

|

|

| CG7133 |

Low

(2) |

604591

|

|

| 428201

|

|

|

l(3)80Fg / CG40178

|

Low

(2) |

445781

|

|

| CLN5: Finnish variant |

CLN5 |

Ceroid-lipofuscinosis neuronal protein 5 |

- |

- |

- |

|

CLN6: Lake-Cavanagh or Indian

variant |

CLN6 |

Transmembrane ER protein |

- |

- |

- |

|

| CLN7: Turkish variant |

MFSD8 |

Major-facilitator superfamily domain containing 8 |

Cln7 / CG8596

|

High

(16) |

619601

|

|

| 556641

|

|

|

rtet / CG5760

|

Low

(2) |

v1104732

|

|

| v440022

|

|

CLN8: Northern epilepsy /

Epilepsy mental retardation |

CLN8 |

Protein CLN8, Transmembrane ER and ERGIC protein |

CG17841 |

Moderate

(3) |

349481

|

|

| CLN9 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

|

|

|

| CLN10: Congenital NCL |

CTSD |

Cathepsin D, Lysosomal Aspartyl peptidase / protease |

cathD / CG1548

|

High

(16) |

289781

|

|

| 538821

|

|

| 551781

|

|

| CLN11 |

GRN |

Granulin (precursor) |

CG15011 |

Low

(1) |

582841

|

|

| 315891

|

|

|

NimC2 / CG18146

|

Low

(1) |

259601

|

|

| v31202

|

|

| v362612

|

|

CLN12: Kufor-Raked syndrome /

PARK9 / Juvenile parkinsonism-

NCL |

ATP13A2 |

Cation-transporting ATPase 13A2, PARK9 |

anne / CG32000

|

Moderate

(13) |

440051

|

|

| 304991

|

|

| CG6230 |

Low

(3) |

773711

|

|

|

SPoCk / CG32451

|

Low

(2) |

440401

|

|

| 283521

|

|

| CLN13 |

CTSF |

Cathepsin F |

CtsF / CG12163

|

High

(14) |

339551

|

|

CLN14: Progressive myoclonic

epilepsy type 3 |

KCTD7 |

Potassium channel tetramerization domain

containing 7 |

Ktl / CG10830

|

Moderate

(2) |

571711

|

|

| 258481

|

|

| CG14647 |

Moderate

(2) |

600641

|

|

| 270321

|

|

|

twz / CG10440

|

Moderate

(2) |

573971

|

|

| 258461

|

|

9. Pycnodysostosis: Toulouse-Lautrec syndrome – Osteopetrosis

acro-osteolytica |

CTSK |

Cathepsin K |

CtsL1 / CG6692

|

Moderate

(8) |

419391

|

|

| 329321

|

|

| 10. Sphingolipidoses |

|

|

A. Acid sphingomyelinase

deficiency (ASMD) |

|

|

Niemann-Pick disease

types A and B |

SMPD1 |

Sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase |

Asm / CG3376

|

High

(17) |

367601

|

|

| CG15533 |

Moderate

(8) |

367611

|

|

| CG15534 |

Moderate

(8) |

367621

|

|

| CG32052 |

Moderate

(6) |

367631

|

|

B. Autosomal recessive cerebellar

ataxia with late-onset spasticity

(due to GBA2 deficiency) |

GBA2 |

β-Glucosylceramidase 2 |

CG33090 |

High

(18) |

366881

|

|

C. Encephalopathy due to

prosaposin deficiency -

Combined PSAP deficiency

(PSAPD) |

PSAP |

Prosaposin |

Sap-r / CG12070

|

High

(14) |

v511292

|

|

| v511302

|

|

| D. Fabry disease – Angiokeratoma corporis diffusum |

GLA |

α-Galactosidase A |

CG7997 |

Moderate

(14) |

636551

|

|

| 577811

|

|

| CG5731 |

Moderate

(13) |

670251

|

|

| E. Farber lipogranulomatosis |

ASAH1 |

Acid Ceramidase |

- |

- |

- |

|

| F. Gangliosidoses |

|

|

a) GM1 gangliosidosis:

Landing disease: |

|

|

type I (infantile):

Norman-Landing disease |

GLB1 |

β-Galactosidase |

Ect3 / CG3132

|

Moderate

(15) |

622171

|

|

| type II (juvenile - late infantile) |

Gal / CG9092

|

Moderate

(14) |

506801

|

|

| type III (adult) |

429221

|

|

| b) GM2 gangliosidosis: |

|

|

| Tay-Sachs disease (B variant) |

HEXA |

β-Hexosaminidase subunit α |

Hexo1 / CG1318

|

Moderate

(13) |

673121

|

|

|

Hexo2 / CG1787

|

Moderate

(12) |

571991

|

|

|

fdl / CG8824

|

Moderate

(11) |

529871

|

|

| 282981

|

|

| Sandhoff disease (0 variant) |

HEXB |

β-Hexosaminidase subunit β |

Hexo1 / CG1318

|

High

(14) |

673121

|

|

|

Hexo2 / CG1787

|

Moderate

(12) |

571991

|

|

|

fdl / CG8824

|

Moderate

(12) |

529871

|

|

| 282981

|

|

c) GM2 activator deficiency (AB

variant) |

GM2A |

GM2 Ganglioside activator |

- |

- |

- |

|

| G. Gaucher disease (GD) |

|

|

| GD type 1 |

GBA1 |

β-Glucocerebrosidase 1 / β-Glucosidase 1 |

Gba1a / CG31148

|

High

(15) |

383791

|

|

| GD type 2 |

390641

|

|

| GD type 3 |

Gba1b / CG31414

|

High

(15) |

389701

|

|

Fetal / Perinatal lethal

Gaucher disease |

389771

|

|

Atypical Gaucher disease due

to Saposin C deficiency |

PSAP |

Prosaposin |

Sap-r / CG12070

|

High

(14) |

v511292

|

|

| v511302

|

|

Gaucher-like disease /

Gaucher disease-

ophthalmoplegia-cardiovascular calcification syndrome / Gaucher disease type 3C |

GBA1 |

β-Glucosylceramidase 1 |

Gba1a / CG31148

|

High

(15) |

383791

|

|

| 390641

|

|

|

Gba1b / CG31414

|

High

(15) |

389701

|

|

| 389771

|

|

H. Globoid cell leukodystrophy –

Krabbe disease |

GALC |

Galactosylceramidase |

- |

- |

- |

|

| I. Lipid storage disease |

|

|

a) Lysosomal acid lipase

deficiency |

|

|

Cholesterol ester storage

disease |

LIPA |

Lipase A lysosomal acid type, Cholesterol ester hydrolase |

Lip3 / CG8823

|

High

(15) |

650251

|

|

| Wolman disease |

|

| b) Niemann-Pick disease type C: |

|

|

| type C1 |

NPC1 |

NPC Intracellular cholesterol transporter 1 |

Npc1a / CG5722

|

High

(16) |

375041

|

|

|

Npc1b / CG12092

|

Moderate

(11) |

382961

|

|

|

SCAP / CG33131

|

Low

(2) |

315661

|

|

| type C2 |

NPC2 |

NPC Intracellular cholesterol transporter 2 |

Npc2a / CG7291

|

High

(16) |

382371

|

|

|

Npc2b / CG3153

|

Moderate

(7) |

382381

|

|

| 429141

|

|

|

Npc2d / CG12813

|

Moderate

(6) |

v310952

|

|

|

Npc2c / CG3934

|

Moderate

(6) |

613151

|

|

|

Npc2e / CG31410

|

Moderate

(6) |

679561

|

|

|

Npc2f / CG6164

|

Moderate

(4) |

v1021722

|

|

| v129152

|

|

|

Npc2h / CG11315

|

Moderate

(3) |

678031

|

|

|

Npc2g / CG11314

|

Moderate

(3) |

630301

|

|

J. Metachromatic leukodystrophy

(MLD) |

ASRA PSAP |

Arylsulfatase A

Prosaposin |

|

|

|

|

K. Multiple Sulfatase deficiency

(MSD) / Mucosulfatidosis |

SUMF1 |

Sulfatase modifying factor 1, Formylglycine-generating enzyme |

CG7049 |

High

(14) |

518961

|

|

Action myoclonus-renal failure syndrome / Myoclonus-nephropathy syndrome /

Progressive myoclonic epilepsy type 4 |

SCARB2 |

Scavenger receptor class B member 2, Lysosomal integral membrane protein II |

emp / CG2727

|

High

(15) |

409471

|

|