Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

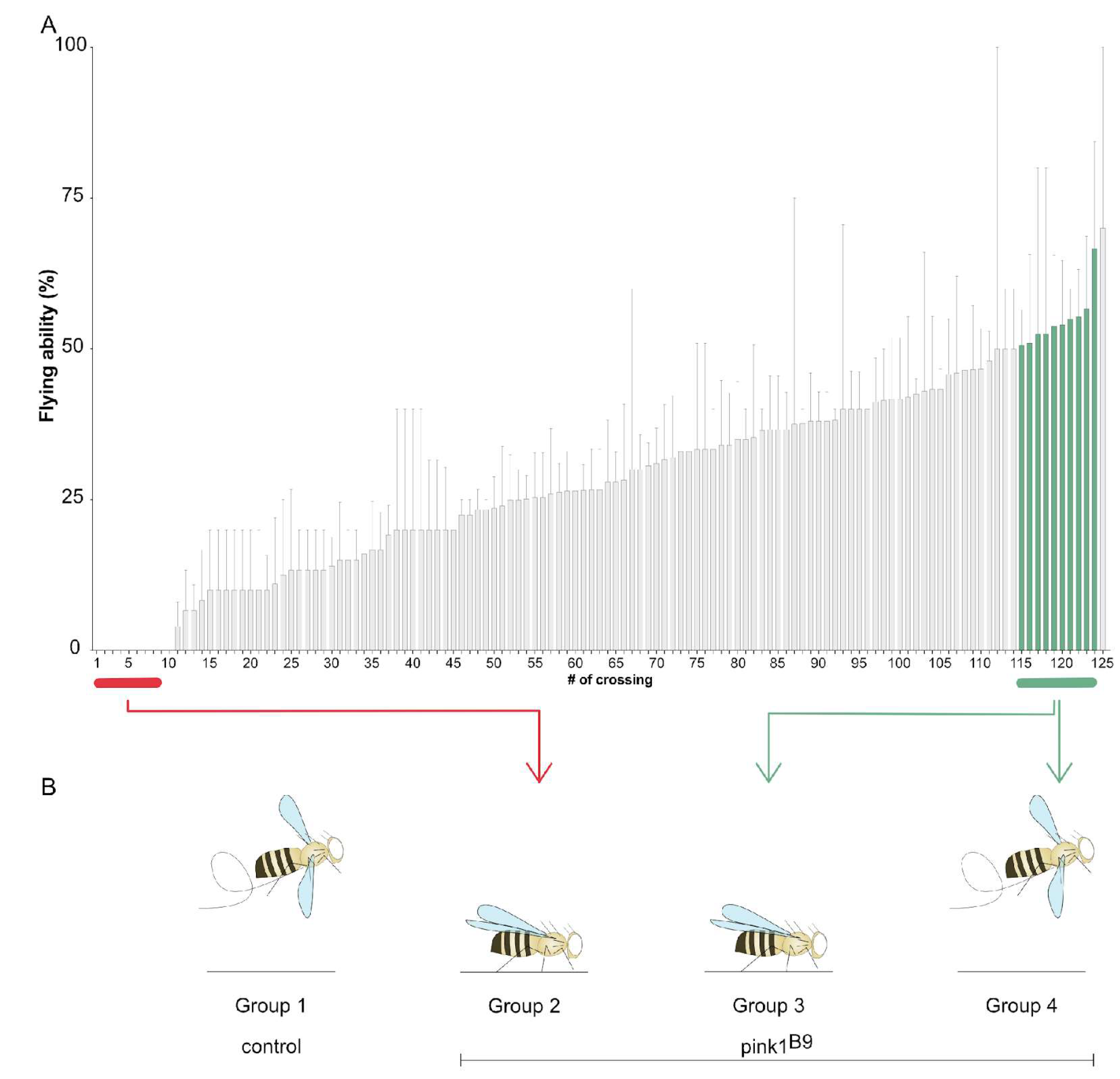

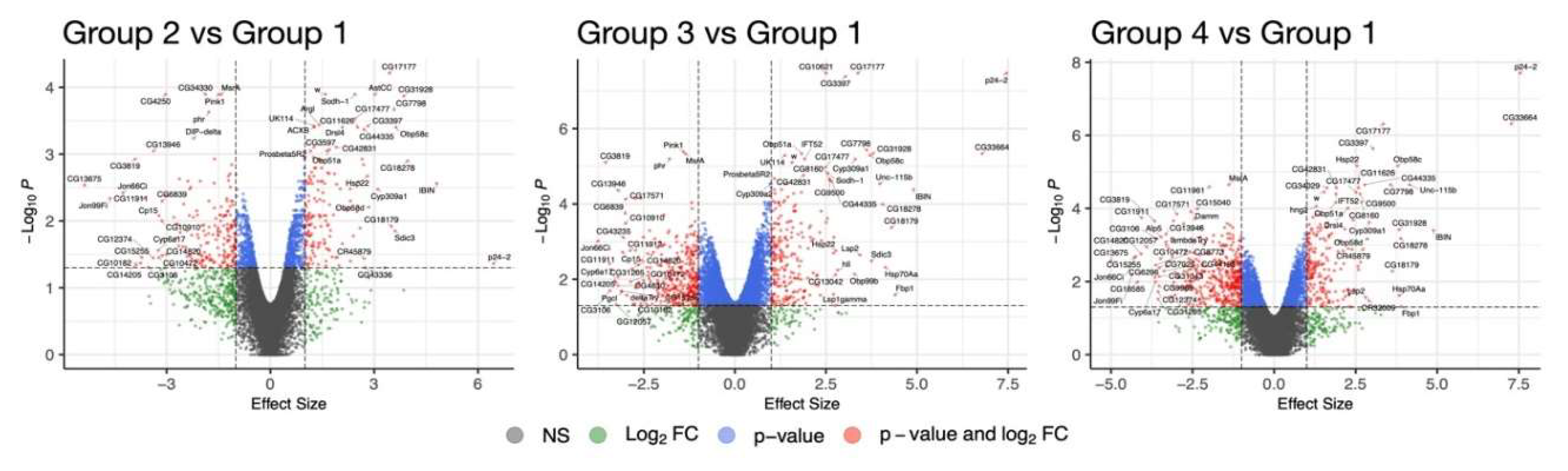

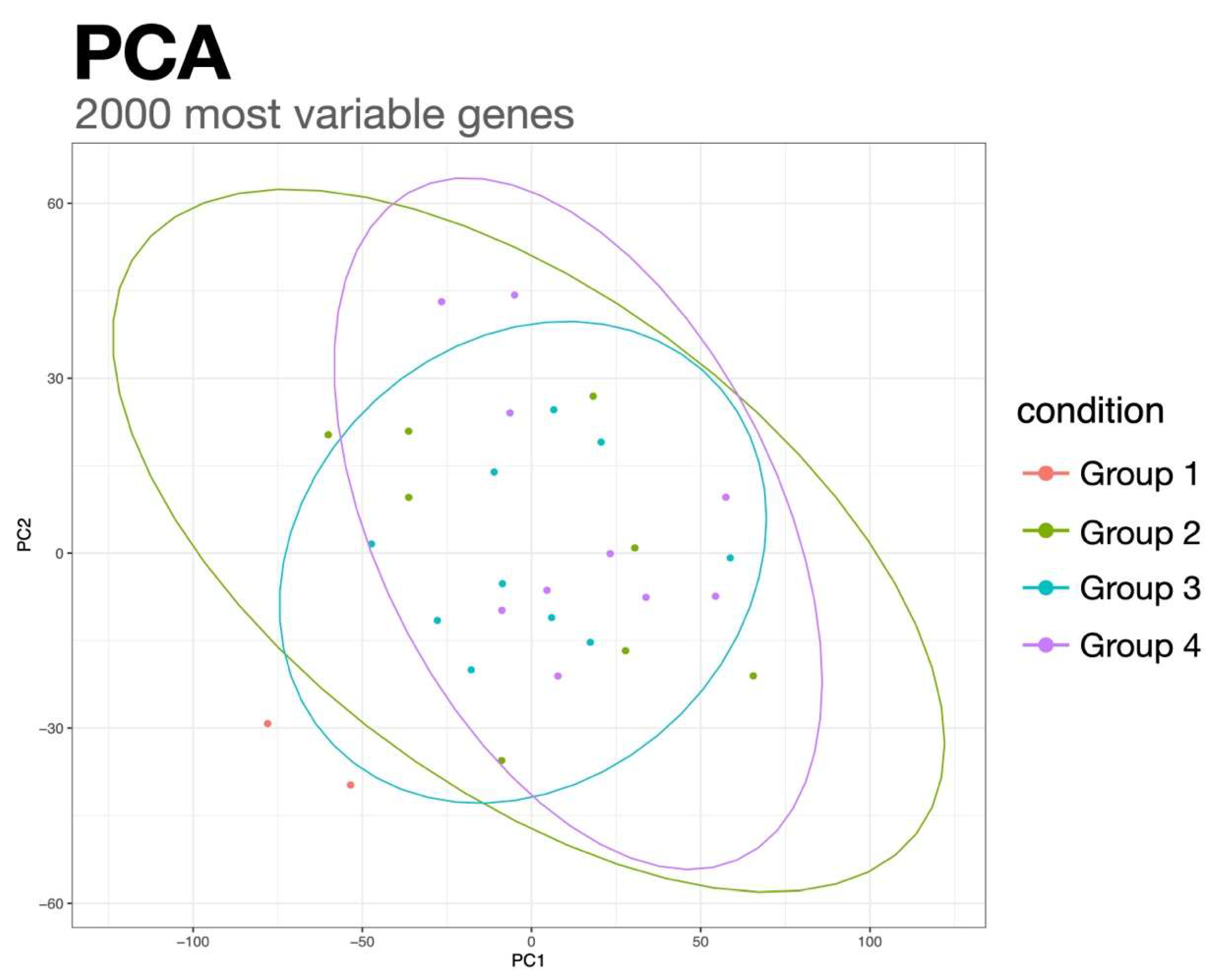

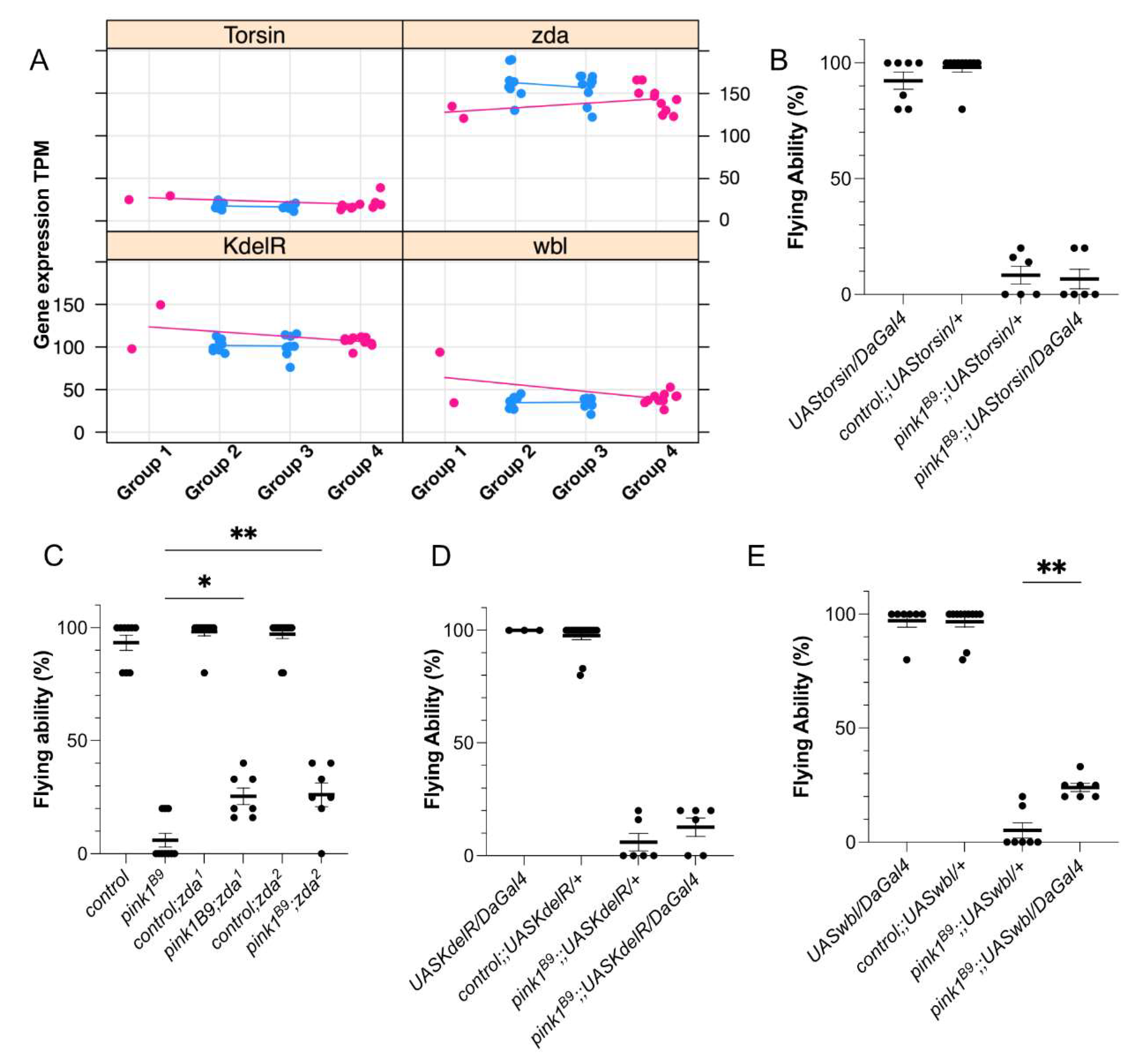

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder with a high variability of age at onset, disease severity, and progression. This suggests that other factors, including genetic, environ-mental, or biological factors, are at play in PD. Loss of PINK1 causes a recessive form of PD and is typically fully penetrant; however, it features a wide range in disease onset, further supporting the existence of protective factors, endogenous or exogenous, to play a role. Loss of Pink1 in Drosophila melanogaster results in locomotion deficits, which are also observed in PINK1-related PD in humans. In flies, Pink1 deficiency induces defects in the ability to fly; none-theless, around ten percent of the mutant flies are still capable of flying, indicating that advanta-geous factors affecting penetrance also exist in flies. Here, we aimed to identify the mechanisms underlying this reduced penetrance in Pink1-deficient flies. We performed genetic screening in pink1-mutant flies to identify RNA expression alterations affecting the flying ability. The most important biological processes involved were transcription-al and translational activities, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) regulation, and flagellated movement and microtubule organization. We validated 2 ER-related proteins, zonda and windbeutel, to positively affect the flying ability of Pink1-deficient flies. Thus, our data suggest that these pro-cesses are involved in the reduced penetrance and that influencing them may be beneficial for Pink1 deficiency.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Lack of Flying Ability of Pink1-Deficient Flies Shows a Pattern of Reduced Penetrance

2.2. RNA Sequencing Analysis Identifies Genes Involved in Reduced Penetrance

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

Fly Genetics

Flight Assay

RNA Sequencing and Analyses

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- B.R. Bloem, M.S. Okun, C. Klein, Parkinson’s disease, Lancet 397 (2021) 2284–2303.

- G.U. Höglinger, C.H. Adler, D. Berg, C. Klein, T.F. Outeiro, W. Poewe, R. Postuma, A.J. Stoessl, A.E. Lang, A biological classification of Parkinson’s disease: the SynNeurGe research diagnostic criteria, Lancet Neurol 23 (2024) 191–204. [CrossRef]

- V.A. Morais, M. Vos, Reduced penetrance of Parkinson’s disease models, Med Genet 34 (2022) 117–124. [CrossRef]

- M. Kasten, C. Hartmann, J. Hampf, S. Schaake, A. Westenberger, E.J. Vollstedt, A. Balck, A. Domingo, F. Vulinovic, M. Dulovic, I. Zorn, H. Madoev, H. Zehnle, C.M. Lembeck, L. Schawe, J. Reginold, J. Huang, I.R. König, L. Bertram, C. Marras, K. Lohmann, C.M. Lill, C. Klein, Genotype-Phenotype Relations for the Parkinson’s Disease Genes Parkin, PINK1, DJ1: MDSGene Systematic Review, Movement Disorders (2018). [CrossRef]

- C. Gabbert, I.R. König, T. Lüth, B. Kolms, M. Kasten, E.J. Vollstedt, A. Balck, A. Grünewald, C. Klein, J. Trinh, Coffee, smoking and aspirin are associated with age at onset in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, J Neurol 269 (2022) 4195–4203. [CrossRef]

- T. Lüth, I.R. König, A. Grünewald, M. Kasten, C. Klein, F. Hentati, M. Farrer, J. Trinh, Age at Onset of LRRK2 p.Gly2019Ser Is Related to Environmental and Lifestyle Factors, Mov Disord 35 (2020) 1854–1858. [CrossRef]

- M. Vos, C. Klein, A.A. Hicks, Role of Ceramides and Sphingolipids in Parkinson’s Disease, J Mol Biol 435 (2023). [CrossRef]

- F. Mandik, M. Vos, Neurodegenerative Disorders: Spotlight on Sphingolipids, Int J Mol Sci 22 (2021). [CrossRef]

- M. Vos, M. Dulovic-Mahlow, F. Mandik, L. Frese, Y. Kanana, S.H. Diaw, J. Depperschmidt, C. Böhm, J. Rohr, T. Lohnau, I.R. König, C. Klein, Ceramide accumulation induces mitophagy and impairs β-oxidation in PINK1 deficiency, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118 (2021) e2025347118. [CrossRef]

- M. Dulovic-Mahlow, I.R. König, J. Trinh, S.H. Diaw, P.P. Urban, E. Knappe, N. Kuhnke, L.C. Ingwersen, F. Hinrichs, J. Weber, P. Kupnicka, A. Balck, S. Delcambre, T. Vollbrandt, A. Grünewald, C. Klein, P. Seibler, K. Lohmann, Discordant Monozygotic Parkinson Disease Twins: Role of Mitochondrial Integrity, Ann Neurol 89 (2021) 158–164. [CrossRef]

- M. Vos, C. Klein, The Importance of Drosophila melanogaster Research to UnCover Cellular Pathways Underlying Parkinson’s Disease, Cells 10 (2021) 579. [CrossRef]

- J. Park, S.B. Lee, S. Lee, Y. Kim, S. Song, S. Kim, E. Bae, J. Kim, M. Shong, J.-M. Kim, J. Chung, Mitochondrial dysfunction in Drosophila PINK1 mutants is complemented by parkin, Nature 441 (2006) 1157–1161. [CrossRef]

- I.E. Clark, M.W. Dodson, C. Jiang, J.H. Cao, J.R. Huh, J.H. Seol, S.J. Yoo, B.A. Hay, M. Guo, Drosophila pink1 is required for mitochondrial function and interacts genetically with parkin, Nature 441 (2006) 1162–1166. [CrossRef]

- D. Narendra, A. Tanaka, D.F. Suen, R.J. Youle, Parkin-induced mitophagy in the pathogenesis of Parkinson disease, Autophagy 5 (2009) 706–708. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19377297.

- D.P. Narendra, S.M. Jin, A. Tanaka, D.F. Suen, C.A. Gautier, J. Shen, M.R. Cookson, R.J. Youle, PINK1 is selectively stabilized on impaired mitochondria to activate Parkin, PLoS Biol 8 (2010) e1000298. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=20126261.

- M. Vos, G. Esposito, J.N. Edirisinghe, S. Vilain, D.M. Haddad, J.R. Slabbaert, S. Van Meensel, O. Schaap, B. De Strooper, R. Meganathan, V.A. Morais, P. Verstreken, Vitamin K2 is a mitochondrial electron carrier that rescues pink1 deficiency, Science (1979) 336 (2012) 1306–1310. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=22582012.

- M. Vos, A. Geens, C. Böhm, L. Deaulmerie, J. Swerts, M. Rossi, K. Craessaerts, E.P. Leites, P. Seibler, A. Rakovic, T. Lohnau, B. De Strooper, S.-M. Fendt, V.A. Morais, C. Klein, P. Verstreken, Cardiolipin promotes electron transport between ubiquinone and complex I to rescue PINK1 deficiency, J Cell Biol 216 (2017) 695–708.

- D. Lindholm, H. Wootz, L. Korhonen, ER stress and neurodegenerative diseases, Cell Death Differ 13 (2006) 385–392. [CrossRef]

- K. Yamamoto, H. Hamada, H. Shinkai, Y. Kohno, H. Koseki, T. Aoe, The KDEL receptor modulates the endoplasmic reticulum stress response through mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascades, J Biol Chem 278 (2003) 34525–34532. [CrossRef]

- E.S. Wires, K.A. Trychta, L.M. Kennedy, B.K. Harvey, The Function of KDEL Receptors as UPR Genes in Disease, Int J Mol Sci 22 (2021). [CrossRef]

- P. Wang, B. Li, L. Zhou, E. Fei, G. Wang, The KDEL receptor induces autophagy to promote the clearance of neurodegenerative disease-related proteins, Neuroscience 190 (2011) 43–55. [CrossRef]

- M. Vos, C. Klein, Ceramide-induced mitophagy impairs ß-oxidation-linked energy production in PINK1 deficiency, Https://Doi.Org/10.1080/15548627.2022.2027193 18 (2022) 703–704. [CrossRef]

- Y. Her, D.M. Pascual, Z. Goldstone-Joubert, P.C. Marcogliese, Variant functional assessment in Drosophila by overexpression: what can we learn?, Genome 67 (2024) 158–167. [CrossRef]

- S. Nagarkar-Jaiswal, P.T. Lee, M.E. Campbell, K. Chen, S. Anguiano-Zarate, M.C. Gutierrez, T. Busby, W.W. Lin, Y. He, K.L. Schulze, B.W. Booth, M. Evans-Holm, K.J.T. Venken, R.W. Levis, A.C. Spradling, R.A. Hoskins, H.J. Bellen, A library of MiMICs allows tagging of genes and reversible, spatial and temporal knockdown of proteins in Drosophila, Elife 4 (2015). [CrossRef]

- J. Sen, J.S. Goltz, M. Konsolaki, T. Schüpbach, D. Stein, Windbeutel is required for function and correct subcellular localization of the Drosophila patterning protein Pipe, Development 127 (2000) 5541–5550. [CrossRef]

- M. Konsolaki, T. Schüpbach, windbeutel, a gene required for dorsoventral patterning in Drosophila, encodes a protein that has homologies to vertebrate proteins of the endoplasmic reticulum, Genes Dev 12 (1998) 120–131. [CrossRef]

- H.R.B. Pelham, The retention signal for soluble proteins of the endoplasmic reticulum, Trends Biochem Sci 15 (1990) 483–486. [CrossRef]

- K. Yamamoto, R. Fujii, Y. Toyofuku, T. Saito, H. Koseki, V.W. Hsu, T. Aoe, The KDEL receptor mediates a retrieval mechanism that contributes to quality control at the endoplasmic reticulum, EMBO J 20 (2001) 3082–3091. [CrossRef]

- M. Brecker, S. Khakhina, T.J. Schubert, Z. Thompson, R.C. Rubenstein, The Probable, Possible, and Novel Functions of ERp29, Front Physiol 11 (2020). [CrossRef]

- A.A. Dukes, V.S. Van Laar, M. Cascio, T.G. Hastings, Changes in endoplasmic reticulum stress proteins and aldolase A in cells exposed to dopamine, J Neurochem 106 (2008) 333–346. [CrossRef]

- P.M.E.S.M.I.S.M.N.L.S.I.-S.I. Slominsky, A common 3-bp deletion in the DYT1 gene in Russian families with early-onset torsion dystonia, Hum Mutat 3 (1999) 269. [CrossRef]

- P. Shashidharan, P.F. Good, A. Hsu, D.P. Perl, M.F. Brin, C.W. Olanow, TorsinA accumulation in Lewy bodies in sporadic Parkinson’s disease, Brain Res 877 (2000) 379–381. [CrossRef]

- N. Sharma, J. Hewett, L.J. Ozelius, V. Ramesh, P.J. McLean, X.O. Breakefield, B.T. Hyman, A close association of torsinA and alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies: a fluorescence resonance energy transfer study, Am J Pathol 159 (2001) 339–344. [CrossRef]

- S. Cao, C.C. Gelwix, K.A. Caldwell, G.A. Caldwell, Torsin-Mediated Protection from Cellular Stress in the Dopaminergic Neurons of Caenorhabditis elegans, (2005). [CrossRef]

- M. Melani, A. Valko, N.M. Romero, M.O. Aguilera, J.M. Acevedo, Z. Bhujabal, J. Perez-Perri, R. V. De La Riva-Carrasco, M.J. Katz, E. Sorianello, C. D’Alessio, G. Juhász, T. Johansen, M.I. Colombo, P. Wappner, Zonda is a novel early component of the autophagy pathway in Drosophila, Mol Biol Cell 28 (2017) 3070. [CrossRef]

- Z. Bhujabal, Å.B. Birgisdottir, E. Sjøttem, H.B. Brenne, A. Øvervatn, S. Habisov, V. Kirkin, T. Lamark, T. Johansen, FKBP8 recruits LC3A to mediate Parkin-independent mitophagy, EMBO Rep 18 (2017) 947–961. [CrossRef]

- D. Narendra, A. Tanaka, D.-F. Suen, R.J. Youle, Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy, J Cell Biol 183 (2008) 795–803. [CrossRef]

- S.M. Yoo, S. ichi Yamashita, H. Kim, D.H. Na, H. Lee, S.J. Kim, D.H. Cho, T. Kanki, Y.K. Jung, FKBP8 LIRL-dependent mitochondrial fragmentation facilitates mitophagy under stress conditions, FASEB J 34 (2020) 2944–2957. [CrossRef]

- G.P. Solis, O. Bilousov, A. Koval, A.M. Lüchtenborg, C. Lin, V.L. Katanaev, Golgi-Resident Gαo Promotes Protrusive Membrane Dynamics, Cell 170 (2017) 939-955.e24. [CrossRef]

- S. Chen, Y. Zhou, Y. Chen, J. Gu, fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor, Bioinformatics 34 (2018) i884–i890. [CrossRef]

- H. Pimentel, N.L. Bray, S. Puente, P. Melsted, L. Pachter, Differential analysis of RNA-seq incorporating quantification uncertainty, Nature Methods 2017 14:7 14 (2017) 687–690. [CrossRef]

- M.E. Ritchie, B. Phipson, D. Wu, Y. Hu, C.W. Law, W. Shi, G.K. Smyth, limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies, Nucleic Acids Res 43 (2015) e47–e47. [CrossRef]

- C. Soneson, M.I. Love, M.D. Robinson, Differential analyses for RNA-seq: Transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences, F1000Res 4 (2016). [CrossRef]

- W. Luo, M.S. Friedman, K. Shedden, K.D. Hankenson, P.J. Woolf, GAGE: Generally applicable gene set enrichment for pathway analysis, BMC Bioinformatics 10 (2009) 1–17. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).