1. Introduction

Anthocyanins are a class of water-soluble pigments widely present in plants, belonging to flavonoid-derived secondary metabolites. They are extensively distributed in the vacuoles of plant organs such as flowers, fruits, seeds, and leaves [

1]. In plants, anthocyanins serve multiple important functions, including attracting pollinating insects, deterring herbivores, activating chemical defenses, and providing protection against pathogen infections, ultraviolet radiation, low temperatures, and drought [

2]. Due to their significant antioxidant properties, anthocyanins also offer multiple health benefits to animals and humans, such as regulating blood glucose levels, lowering blood lipids, and inhibiting the occurrence of certain cancers [

3]. Currently, approximately 600 types of anthocyanins have been identified in nature, with six main types: delphinidin, pelargonidin, petunidin, cyanidin, peonidin, and malvidin. Among these, cyanidin is the most common. In terms of plant coloration, cyanidin and pelargonidin impart red hues, while delphinidin and its methylated derivatives (e.g., petunidin and malvidin) confer blue-purple colors [

4]. The final color displayed by anthocyanins is collectively influenced by various factors such as copigmentation, vacuolar pH, structural differences, and metal ions [

5].

The biosynthetic pathway of anthocyanins is a specific branch of the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway and is the end product of the phenylpropanoid/flavonoid pathway, involving multiple enzymes [

6]. Dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR) is the rate-limiting enzyme in this pathway. It determines the direction of carbon flow, leading to significant differences in the types of anthocyanins [

7]. Studies have shown that DFR can catalyze three colorless dihydroflavonols (dihydrokaempferol DHK, dihydroquercetin DHQ, dihydromyricetin DHM) into the corresponding leucoanthocyanidins. Therefore, DFR is regarded as a key regulatory node in the process of anthocyanin biosynthesis [

8]. There are three types of DFRs: The first is the Asparagine-type (Asn-type) DFRs, with Asn at position 134, widely distributed in plants, capable of catalyzing the conversion of all three dihydroflavonols; the second is the Aspartate-type (Asp-type) DFRs, with Asp at position 134, highly specific for DHQ and DHM, and cannot effectively catalyze DHK; the third type is called non-Asn/Asp-type DFRs, containing neither Asn nor Asp [

9]. Biochemical analyses indicate that DFR proteins have substrate specificity, which influences the content and proportion of different anthocyanins, ultimately leading to variations in plant color [

10]. For example, petunia DFR cannot effectively catalyze the monohydroxylated DHK, hence this species lacks orange flowers. However, when several amino acids at the active site of the DFR enzyme are modified, the mutated petunia DFR gains the ability to catalyze DHM, resulting in orange flowers producing pelargonidin-based anthocyanins [

11]. Consequently, DFR plays a crucial role in the anthocyanin pathway, and modulating its expression level can effectively alter plant color.

Lonicera japonica Thunb. (Caprifoliaceae) refers to the dried flower buds or nearly open flowers of the plant, commonly known as Jin-Yin-Hua, or Flos Lonicerae Japonicae (FLJ). It is a traditional Chinese medicinal herb with biological activities such as antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, antioxidant, anti-endotoxin, hypolipidemic, and antipyretic effects [

12]. Pharmacological studies have shown that its main active components include chlorogenic acid, luteolin-7-O-glucoside (luteoloside), and iridoid compounds, which can be used to treat arthritis, diabetes, fever, infections, ulcers, and swelling. Additionally, it is an important antiviral agent against SARS coronavirus, influenza A virus, and the novel coronavirus [

13].

Lonicera japonica Thunb. var.

chinensis (Wats.) Bak. (RFLJ) is a natural mutant of L. japonica. Its young branches, leaves, and stems are all purplish-red, and the corolla is purplish-red on the outside and white on the inside. Compared to L. japonica, RFLJ contains higher levels of luteoloside, quercetin, chlorogenic acid, and anthocyanins, as well as a greater variety of volatile oils. Research by Yuan et al. indicate that the anthocyanin content in RFLJ can be as high as 100 mg/100 g [

14]. Consequently, RFLJ is more fragrant, has a longer flowering period, blooms earlier, and exhibits higher ornamental and tea-drinking value, integrating medicinal, ornamental, and greening purposes, along with stronger cold resistance and drought tolerance. L. japonica flowers exhibit vivid coloration and a sweet scent, progressing through six developmental stages: S1 (young alabastrum), S2 (green alabastrum), S3 (slightly white alabastrum), S4 (whole white alabastrum), S5 (silvery flower), and S6 (golden flower). Differential anthocyanin accumulation and flower color at S4 distinguish L. japonica (GFLJ, with green flower) from RFLJ (with purple flower) [

15].

Currently, research on DFR mainly focuses on gene cloning and functional identification. The

DFR gene family has been identified in only a few species, such as

Capsicum annuum [

16] and

Camellia sinensis [

17], while a comprehensive identification or systematic study of the

DFR gene family in L. japonica has been lacking. In this study, based on the genome and transcriptome databases of L. japonica, we identified members of the LjDFR family at the whole-genome level and cloned all LjDFR members. We systematically analyzed their physicochemical properties, chromosomal localization, collinearity, evolutionary relationships, conserved protein domains, gene structures, and promoter cis-acting elements. Additionally, the subcellular localization of LjDFR proteins was verified using GFP fusion protein expression method, and the expression patterns of

LjDFR genes in different tissues, at different flowering stages of varieties with different flower colors, and under drought and salt stresses were detected via qRT-PCR. This research lays a foundation for further exploring the function of

LjDFR genes in the anthocyanin metabolic pathway and provides theoretical guidance for the breeding of new

Lonicera varieties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Stress Treatments

The test materials, GFLJ and RFLJ, were provided by the Institute of Chinese Herbal Medicines, Henan Academy of Agricultural Sciences, and cultivated under natural conditions at the Modern Agricultural Research and Development Base of Henan Academy of Agricultural Sciences. During the first flowering stage, roots, stems, leaves, and flower buds from both varieties were collected, along with flowers at different developmental stages. For each sample, 3 biological replicates were prepared. After rapid freezing in liquid nitrogen, samples were stored at -80 °C for subsequent use.

One-year-old healthy cutting seedlings were selected and acclimated to hydroponic culture using 50% Hoagland nutrient solution followed by 100% Hoagland nutrient solution, each for two weeks. Seedlings with uniform growth were then subjected to drought stress (25% PEG 6000) or salt stress (300 mmol·L⁻¹ NaCl). Samples were collected at 0, 3, 12, 24, 48, and 80 hours after treatment initiation, with the 0-hour sample serving as the control. For each treatment, leaves from 3–5 seedlings were pooled to form one biological replicate. The mixed samples were quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C, three replicates were taken for each time point. The experiment was conducted in a constant-temperature light incubator under the following conditions: temperature (23±2) °C, relative air humidity 40%–50%, light intensity 1,000 μmol·m⁻²·s⁻¹, and a photoperiod of 14 h·d⁻¹.

2.2. Identification and Chromosomal Distribution of the LjDFR Gene Family

The L. japonica genome sequences, protein sequences, and genome annotation files (Project ID: PRJCA001719) were downloaded from the National Genomics Data Center (

https://bigd.big.ac.cn/gwh, accessed on 21 October 2025)[

18].

Arabidopsis thaliana DFR protein sequences were obtained from TAIR (

https://www.arabidopsis.org/, accessed on 21 October 2025), while the DFR protein sequences of

Capsicum annuum,

Camellia sinensis, and

Brassica napus were retrieved from the literature [

16]. The AtDFR protein sequences were used for a BLASTP search against the L. japonica database. Sequences with homology greater than 50%, E-value less than 1×10⁻⁵⁰, and bit-score greater than 300 were screened, and duplicates were removed. Two online databases—SMART (

http://smart.emblheidelberg.de/, accessed on 22 October 2025) and CD-Search Tool (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/bwrpsb/bwrpsb.cgi, accessed on 22 October 2025) were used for verification, and sequences lacking the complete DFR conserved domain were excluded. Chromosomal location information of

LjDFR genes was acquired from the genome annotation file (GFF), and the distribution was visualized using TBtools software.

2.3. Cloning, Physicochemical Properties, and Structural Characteristics Analysis of LjDFR Genes

Using the previously obtained

LjDFR gene sequences as references, specific primers were designed with Primer Premier 5 software (

Table S1). PCR amplification was performed using KOD enzyme with cDNA from L. japonica petals as the template. The 20 μL reaction system consisted of: 10 μL of 2×PCR buffer for KOD FX, 4 μL of 2 mM dNTPs, 2 μL of cDNA template, 0.6 μL each of forward and reverse primers, 0.4 μL of KOD FX, and 2.4 μL of sterile double-distilled water. The reaction program was set as follows: pre-denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min; 35 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, and extension at 68 °C for 2 min; and a final extension at 68 °C for 5 min. PCR products were ligated into a T-vector and sent to Henan Youkang Biotechnology for sequencing [

19]. The obtained nucleotide sequences were imported into DNAMAN 6.0 to derive the encoded amino acid sequences. Physicochemical properties of LjDFR proteins, such as number of amino acids, molecular weight, theoretical isoelectric point and hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity were predicted using the Protein Parameter Calc tool in TBtools-II v2.202. Subcellular localization was predicted via Plant-mPLoc (

http://www.csbio.sjtu.edu.cn/bioinf/plant-multi/, accessed on 23 October 2025). Secondary structure was predicted using Prabi (

https://npsa-prabi.ibcp.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl?page=/NPSA/npsa_sopma.html, accessed on 23 October 2025). Based on the principle of homology modeling, the tertiary structure models were constructed using SWISS-MODEL (

https://swissmodel.expasy.org/interactive, accessed on 24 October 2025). Transmembrane domains were analyzed with TMHMM-2.0 (

https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0/, accessed on 24 October 2025).

2.4. Subcellular Localization Analysis

Using the full-length plasmid obtained above as the template, the coding sequences of LjDFR3 and LjDFR6 without stop codons were amplified using primers with homologous arms and adapters. They were fused with the pCAMBIA1300 vector, and the 35S::LjDFR::GFP fusion vectors driven by the CaMV35S promoter were constructed using the ClonExpress® II One-Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The fusion vectors were transformed into the abaxial side of 3-week-old tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) leaves via Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. Tobacco plants were cultured in the dark at 25 °C for 24 h, then grown normally for 1–2 days. A Zeiss LSM710 confocal laser scanning microscope was used to observe fluorescence signals with 488 excitation light.

2.5. Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

Multiple sequence alignment of DFR proteins from L. japonica, Arabidopsis thaliana, Capsicum annuum, Camellia sinensis, and Brassica napus was performed using ClustalW in MEGA 7.0 software. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Neighbor-joining method with Bootstrap set to 1,000. The tree was optimized using Evolview online software and Adobe Illustrator. Multiple sequence alignment of LjDFR proteins was conducted using DNAMAN6.0 and visualized with GeneDoc and Adobe Illustrator.

2.6. Conserved Motif and Gene Structure Analysis

The amino acid sequences of LjDFR proteins were submitted to the online tool MEME 5.5.2 (

http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme, accessed on 24 October 2025) for conserved motif analysis (maximum number of motifs = 10, motif width = 6–50 amino acids). The exon-intron structure of

LjDFR genes was analyzed using GSDS 2.0 (

http://gsds.gao-lab.org/, accessed on 24 October 2025), and results were visualized using TBtools [

20].

2.7. Collinearity Analysis and Identification of Cis-Acting Elements in Promoters of the LjDFR Gene Family

The collinear relationships among

LjDFR gene family in the L. japonica genome were analyzed using One Step MCScanX [

21] in TBtools and visualized via the Advance Circos module. The 2,000 bp sequences upstream of the ATG start codon of

LjDFR genes were extracted from the L. japonica database. Cis-acting elements analysis was performed using PlantCARE (

https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/, accessed on 24 October 2025), and the screened cis-acting regulatory elements were visualized using TBtools .

2.8. RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis, and qRT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from roots, stems, leaves, flowers at different developmental stages, and stress-treated samples of both L. japonica varieties using the Vazyme FastPure® Universal Plant Total RNA Isolation Kit (Cat. No. RC411). RNA quality and integrity were assessed by 1.1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and concentration/purity were determined using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer. Total RNA (1 μg) with an A260/A280 ratio of 1.8–2.0 was selected for reverse transcription to synthesize cDNA using the Vazyme HiScript® Ⅲ 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (+gDNA wiper) (Cat. No. R312). Fluorescent quantitative primers were designed using Primer Premier 5 based on conserved regions of the cDNA sequences (

Table S1). The 10 μL qRT-PCR reaction system consisted of 5 μL of RealStar Fast SYBR qPCR Mix (2×) (GenStar), 1 μL of cDNA (10×), 0.3 μL each of forward and reverse primers (10 μmol·L⁻¹), and 3.4 μL of RNase-free ddH₂O. The reaction program was: pre-denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min; 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s and annealing/extension at 60 °C for 30 s. Amplification was performed on a QIAquant 96 2 plex real-time Detection System (Qiagen, Germany), and amplification specificity was monitored via melting curve analysis. Three biological replicates and three technical replicates were used. LjG6PD was used as the reference gene [

22], and relative expression levels were calculated using the 2

⁻ΔΔCT method. The experimental data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three biological replicates. Tukey’s test was used for significance analysis (

P< 0.05;

P< 0.01).

4. Discussion

Flower color is a key ornamental trait and a primary target for breeding. It is mainly determined by the accumulation and combination of pigments such as chlorophyll, carotenoids, and anthocyanins [

2]. DFR as the first key enzyme committed to anthocyanin biosynthesis, plays a pivotal role. Its functional loss prevents anthocyanin production, directly affecting color. The first

DFR gene was identified in maize research and has been successfully applied in genetic engineering studies to alter the flower color of petunias [

23]. In addition, overexpression of

HvDFR in tobacco deepened the flower color of tobacco [

24], overexpressing

OjDFR1 in

AtDFR mutant tt3-1 successfully restored anthocyanin content and heterologous expression of

OjDFR1 in transgenic tobacco led to darker flower color by upregulating the expression of endogenous

NtANS and

NtUFGT [

25], transgenic expression of

RdDFR1 restored the anthocyanin biosynthesis defects in the seed coat, hypocotyls, and cotyledons of tt3-1 and changed the flower color of tobacco from pale pink to deep pink [

26]. This study identified six

DFR genes in L. japonica, a number comparable to families in

Camellia sinensis (5 members) [

17] but smaller than in

Capsicum annuum (9 members) [

16].

The structure of

DFR genes is associated with their functions. The length of the amino acid sequences of DFR proteins in L. japonica ranges from 328 to 391 amino acids, with an average molecular weight of 39.241 kDa, which is comparable to the length of DFR amino acid sequences reported in most other plant species [

27]. The number of neutral amino acids is much larger than the number of acidic and basic amino acids, which may be more conducive to the formation of α-helix secondary structures. The α-helix content of all 6 LjDFR proteins is over 39%, and except for LjDFR2, the α-helix is the most abundant secondary structure among the other 5 LjDFR proteins. The folding pattern of a protein determines its function by influencing its shape, surface characteristics, and spatial structure. All members of the

LjDFR gene family are hydrophilic and unstable proteins, which may be related to their relatively high proportions of α-helix and random coil structures [

28]. Similar DFR structures have also been found in

Brassica oleracea,

Glycine max,

Meconopsis [

29,

30,

31].

In addition, the function of DFR is also related to its site of action. Subcellular localization experiments showed that LjDFR3 and LjDFR6 are localized to the cell membrane and nucleus, similar to DFRs in

Hosta ventricosa [

24] and

Brassica oleracea [

32], but differing from the cytoplasmic localization in

Loropetalum chinense [

33,

34], indicating diverse subcellular localization patterns for DFRs across species. Studies have shown that anthocyanins are mainly synthesized in the cytoplasm and then transported to vacuoles for storage via transport proteins. This suggests that

DFR genes may play roles in multiple organelles.

Phylogenetic analysis grouped LjDFRs into four subfamilies, showing high conservation and clustering with DFRs from other species, similar to the pattern in

Capsicum annuum [

16], indicating that there are no members with species-specific evolution in L. japonica. Eukaryotic organisms undergo frequent gene duplication events during evolution. These events generate new genes for organisms, thereby helping plants adapt to environmental conditions and providing a rich genetic basis [

35]. Further collinearity analysis showed that there is no collinearity among

LjDFR genes, suggesting that there are almost no gene duplication events among members of the LjDFR family during evolution. Gene structure plays a crucial role in the evolution of gene families. Studies have shown that structural differentiation contributes more to the divergence of duplicated genes and is the main reason for the rapid emergence of new functions and new genes [

36]. In this study, most

LjDFR genes possess 6 exons, while two members (

LjDFR5,

LjDFR6) have 5, hinting at potential functional divergence.

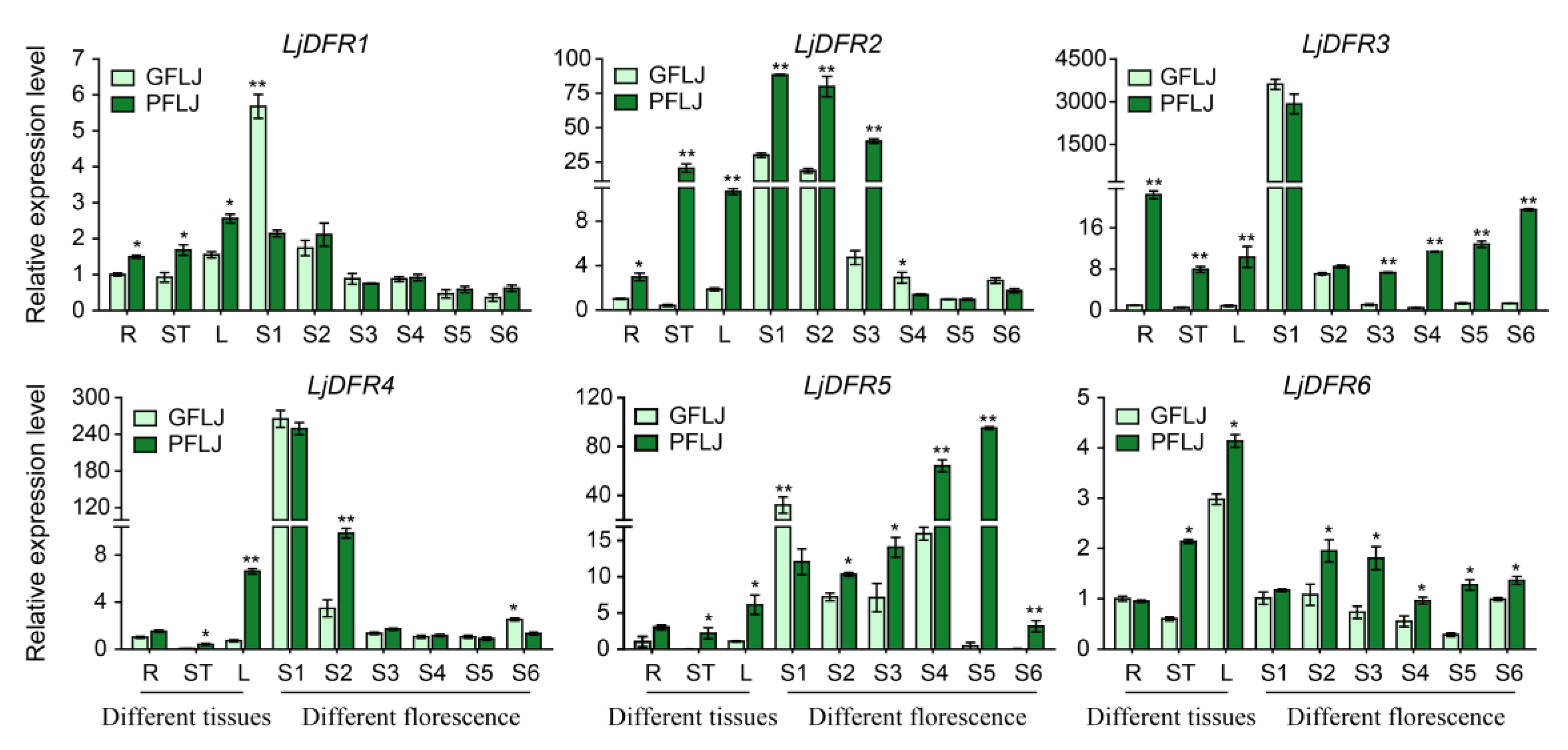

LjDFR genes exhibited tissue-specific and developmentally regulated expression. Most showed highest expression in flowers, followed by leaves, consistent with findings in

Hosta ventricosa [

24] and

Carthamus tinctorius [

27]. During flower development (S1–S6), most

LjDFR genes showed gradually decreased expression from S1, lowest at S5, and a slight increase at S6, similar to the findings to

Meconopsis [

31] and

Cineraria [

37], but inconsistent with the expression pattern of

HvDFR—which gradually increases from S1 to S3 stage of flower development and then decreases [

24]. These results indicate that the expression of

DFR genes is species- and stage-specific regulation.

Crucially, the expression levels of

LjDFR genes were generally higher in the red-flowered variety (RFLJ) than in the green-flowered (GFLJ), particularly in pigmented tissues and specific developmental stages, such as stems, leaves and some flowering periods. All

LjDFR genes in stems and leaves of RFLJ were significantly higher than in GFLJ, the expression levels of

LjDFR2,

LjDFR3,

LjDFR4,

LjDFR5 and

LjDFR6 in RFLJ were extremely significantly higher than in GFLJ at S1-S3, S3-S6, S2, S2-S6 and S2-S6 respectively. This correlation between higher

DFR expression and darker pigmentation aligns with observations in

Rhododendron hybridum [

38] and

Chrysanthemum morifolium [

39,

40]. Phylogenetically, LjDFR2 clusters closely with functionally characterized DFRs CsDFRa [

17] and CaDFR5 [

16]. Previous studies have confirmed that the CsDFRa protein has DFR activity and can convert dihydroflavonols into leucoanthocyanidins in vitro. Moreover, overexpression of

CsDFRa in the

AtDFR mutant (tt3) showed that these proteins are involved in the biosynthesis of anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins (PAs): they not only restored the purple petiole phenotype but also improved the seed coat color [

17]. Additionally, the expression level of

CaDFR5 is consistent with changes in anthocyanin content [

16]. This, combined with its high expression in RFLJ, strongly suggests that

LjDFR2 plays a positive role in anthocyanin accumulation and flower color formation in L. japonica.

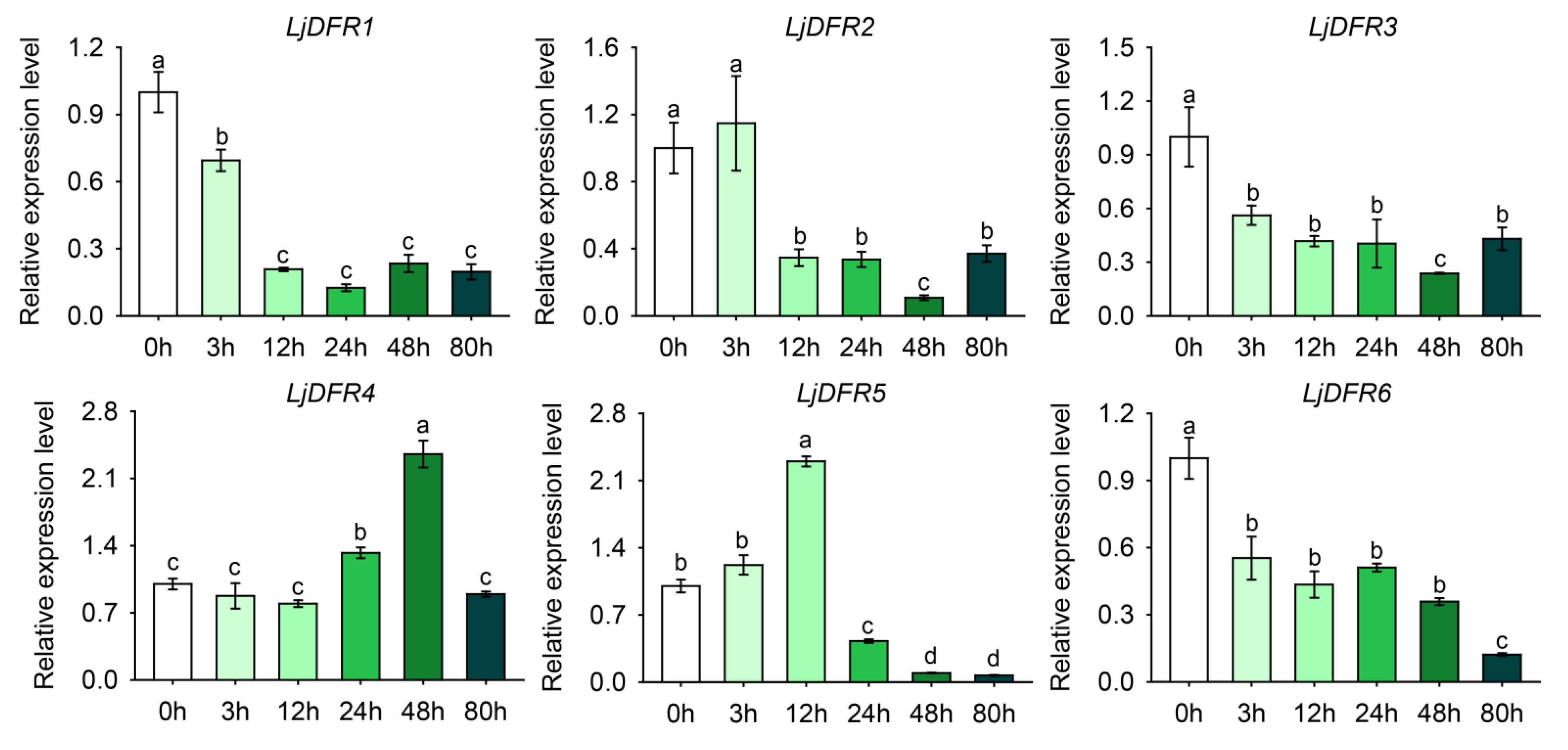

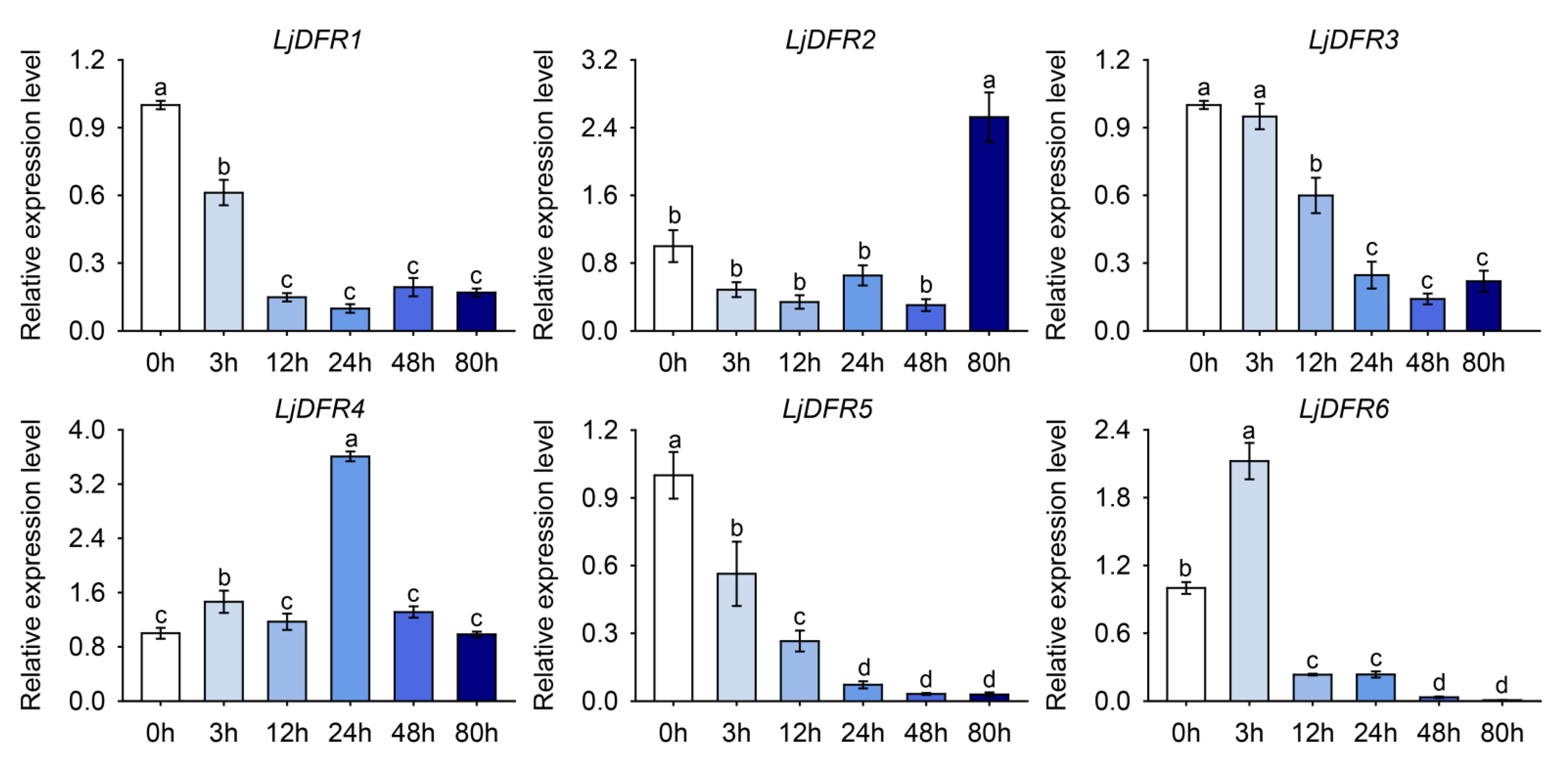

Promoter is a DNA sequence located upstream of a gene. Gene promoters contain various cis-acting elements, which can function individually or collectively to enhance or inhibit transcription; they can also bind to different transcription factors to regulate the transcriptional level of genes in response to biotic or abiotic stresses. Therefore, studying gene promoters to analyze the expression characteristics and functions of plant genes is of great significance. In this study, promoter analysis revealed an abundance of stress-responsive cis-elements, prompting investigation under abiotic stress. Accordingly, drought and salt stress treatments were applied to L. japonica. The results showed that under drought stress, LjDFR2, LjDFR4, and LjDFR5 all exhibited upregulated expression to varying degrees during the treatment period, reaching 1.2-fold, 2.4-fold, and 2.3-fold of the control, respectively. Under salt stress, LjDFR2, LjDFR4, and LjDFR6 also showed upregulated expression being 2.5-fold, 3.6-fold, and 2.1-fold of the control, respectively. Among them, both LjDFR2 and LjDFR4 were significantly induced under drought and salt stress, indicating their potential roles in abiotic stress response, which lays a foundation for further analyzing the functions and mechanisms of LjDFR genes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Zhengwei Tan, Huizhen Liang; methodology, Dandan Lu, Xiaoyu Su; software, Lei Li, Lina Wang; validation, Yiwen Cao; formal analysis, Yongliang Yu, Meiyu Qiao ; investigation, Yao Sun; resources, Mengfan Su; data curation, Yiwen Cao, Chunming Li; writing—original draft preparation, Dandan Lu; writing—review and editing, Zhengwei Tan, Xiaoyu Su; visualization, Hongqi Yang, Yiwen Cao; supervision, Huizhen Liang; project administration, Zhengwei Tan, Chunming Li ; funding acquisition, Zhengwei Tan, Huizhen Liang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Distribution of LjDFR family members on chromosomes map (A) and PCR amplification of LjDFR genes (B). 1-6: LjDFR1-LjDFR6; M: DL 5000 marker (5000, 3000, 2000, 1000, 750, 500, 250, 100 bp).

Figure 1.

Distribution of LjDFR family members on chromosomes map (A) and PCR amplification of LjDFR genes (B). 1-6: LjDFR1-LjDFR6; M: DL 5000 marker (5000, 3000, 2000, 1000, 750, 500, 250, 100 bp).

Figure 2.

Prediction of secondary structure (A), tertiary structure (B) and transmembrane structure (C) of LjDFR proteins.

Figure 2.

Prediction of secondary structure (A), tertiary structure (B) and transmembrane structure (C) of LjDFR proteins.

Figure 3.

Subcellular localization of LjDFR proteins. GFP indicates the green fluorescence field, mCherry stands for the nuclear marker, Luc-mCherry stands for the membrane marker, Bright field indicates the bright field images, and Merge stands for the superimposed field. Scale bar =20 μm.

Figure 3.

Subcellular localization of LjDFR proteins. GFP indicates the green fluorescence field, mCherry stands for the nuclear marker, Luc-mCherry stands for the membrane marker, Bright field indicates the bright field images, and Merge stands for the superimposed field. Scale bar =20 μm.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree of DFRs in Lonicera japonica (Lj, ▲), Camellia sinensis (Cs, ●), Capsicum annuum (Ca, ■), Brassica napus (Bn, ♦) and Arabidopsis thaliana (At, ★).

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree of DFRs in Lonicera japonica (Lj, ▲), Camellia sinensis (Cs, ●), Capsicum annuum (Ca, ■), Brassica napus (Bn, ♦) and Arabidopsis thaliana (At, ★).

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree (A), conserve motif (B) and gene structure (C) analysis of LjDFR gene family. (A) The phylogenetic tree of LjDFR proteins; (B) The conserved motifs of LjDFR proteins, Motif 1–10 in different colored blocks represent the motif composition; (C) Gene structure of LjDFR genes. CDS: coding sequence.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree (A), conserve motif (B) and gene structure (C) analysis of LjDFR gene family. (A) The phylogenetic tree of LjDFR proteins; (B) The conserved motifs of LjDFR proteins, Motif 1–10 in different colored blocks represent the motif composition; (C) Gene structure of LjDFR genes. CDS: coding sequence.

Figure 6.

Cis-elements in the LjDFR gene promoters. (A) The location of the promoter cis-acting elements. (B) Statistical analysis of number of cis-acting elements in promoter region of LjDFR gene family.

Figure 6.

Cis-elements in the LjDFR gene promoters. (A) The location of the promoter cis-acting elements. (B) Statistical analysis of number of cis-acting elements in promoter region of LjDFR gene family.

Figure 7.

Differential expression patterns of LjDFR genes in different tissues and different florescence petals in GFLJ and RFLJ. All the data indicate means ±SD of three replicates. *indicates P < 0.05, **indicates P < 0.01.

Figure 7.

Differential expression patterns of LjDFR genes in different tissues and different florescence petals in GFLJ and RFLJ. All the data indicate means ±SD of three replicates. *indicates P < 0.05, **indicates P < 0.01.

Figure 8.

Expression patterns of LjDFR genes in L. japonica under drought treatment. All the data indicate means ±SD of three replicates. Different letters represented significant difference in purity (P<0.05).

Figure 8.

Expression patterns of LjDFR genes in L. japonica under drought treatment. All the data indicate means ±SD of three replicates. Different letters represented significant difference in purity (P<0.05).

Figure 9.

Expression patterns of LjDFR genes in L. japonica under NaCl treatment. All the data indicate means ±SD of three replicates. Different letters represented significant difference in purity (P<0.05).

Figure 9.

Expression patterns of LjDFR genes in L. japonica under NaCl treatment. All the data indicate means ±SD of three replicates. Different letters represented significant difference in purity (P<0.05).