1. Introduction

The Amazon, the largest continuous tropical forest on the planet, harbors unparalleled biological and structural diversity shaped by complex interactions among stable climate, high water availability, and heterogeneous edaphic gradients [

1,

2]. This combination of factors supports highly specialized plant communities, including mega-trees that stand out not only for their exceptional dimensions but also for their central role in ecological and climatic regulation [

3].

Within the Amazonian landscape, large trees [

4] are defined as individuals with a diameter at breast height (DBH) ≥ 70 cm [

5]. These trees hold cultural significance for local communities, perform essential ecological functions, and sustain diverse forms of life [

3]. Furthermore, they store a substantial portion of forest biomass, playing a critical role in carbon storage and in maintaining the structural integrity of Amazonian forests [

6].

In this study, large trees were defined as those with DBH ≥ 70 cm. This threshold has been widely adopted in studies of forest structure and biomass distribution in tropical ecosystems and in global monitoring networks, as well as in the protocol proposed by Harris et al. [

7] for forest research in the Republic of the Congo. Similarly, recent surveys in the Amazon [

6] also employ this threshold, which marks the point above which individuals begin to concentrate a disproportionate fraction of total biomass [

8,

9]. This definition enables standardized comparisons among studies and reinforces the ecological and functional importance of large trees in maintaining carbon stocks and forest structure.

Recent studies have identified regions with high concentrations of giant trees in the states of Pará and Amapá [

6,

10]. Ecologically, these trees function as “ecosystem engineers,” influencing both the structure and diversity of plant communities and contributing substantially to forest carbon stocks [

3,

6]. Their capacity to store carbon further underscores their importance in the context of climate change [

6,

10].

Large trees account for a significant proportion of aboveground biomass. This concentration exemplifies the phenomenon of biomass hyperdominance, described by Slik et al. [

8], in which a small number of individuals or species are responsible for a disproportionate share of carbon storage. This is a universal pattern in Amazonian forests [

11], corroborated by pantropical evidence indicating that only about 1% of species can contain up to half of total biomass and carbon productivity [

12]. From a functional perspective, trees with DBH ≥ 60–70 cm may represent between one-third and nearly half of living biomass [

9,

13], making them structural keystones for stability and carbon storage in tropical forests.

Despite their ecological significance, little is known about the environmental conditions that support these monumental trees, particularly regarding the edaphic factors that determine their occurrence and growth. The physical and chemical composition of soils is recognized as one of the main drivers of tropical forest structure, influencing germination, growth, and interspecific competition [

2]. However, vast portions of the Amazon remain scientifically unexplored, limiting our understanding of its ecological heterogeneity [

14].

In this study, we assess whether the occurrence of large trees in specific regions is explained by edaphic attributes. Specifically, we test the hypothesis that soil characteristics are correlated with the diversity and biomass of large-sized individuals.

2. Materials and Methods

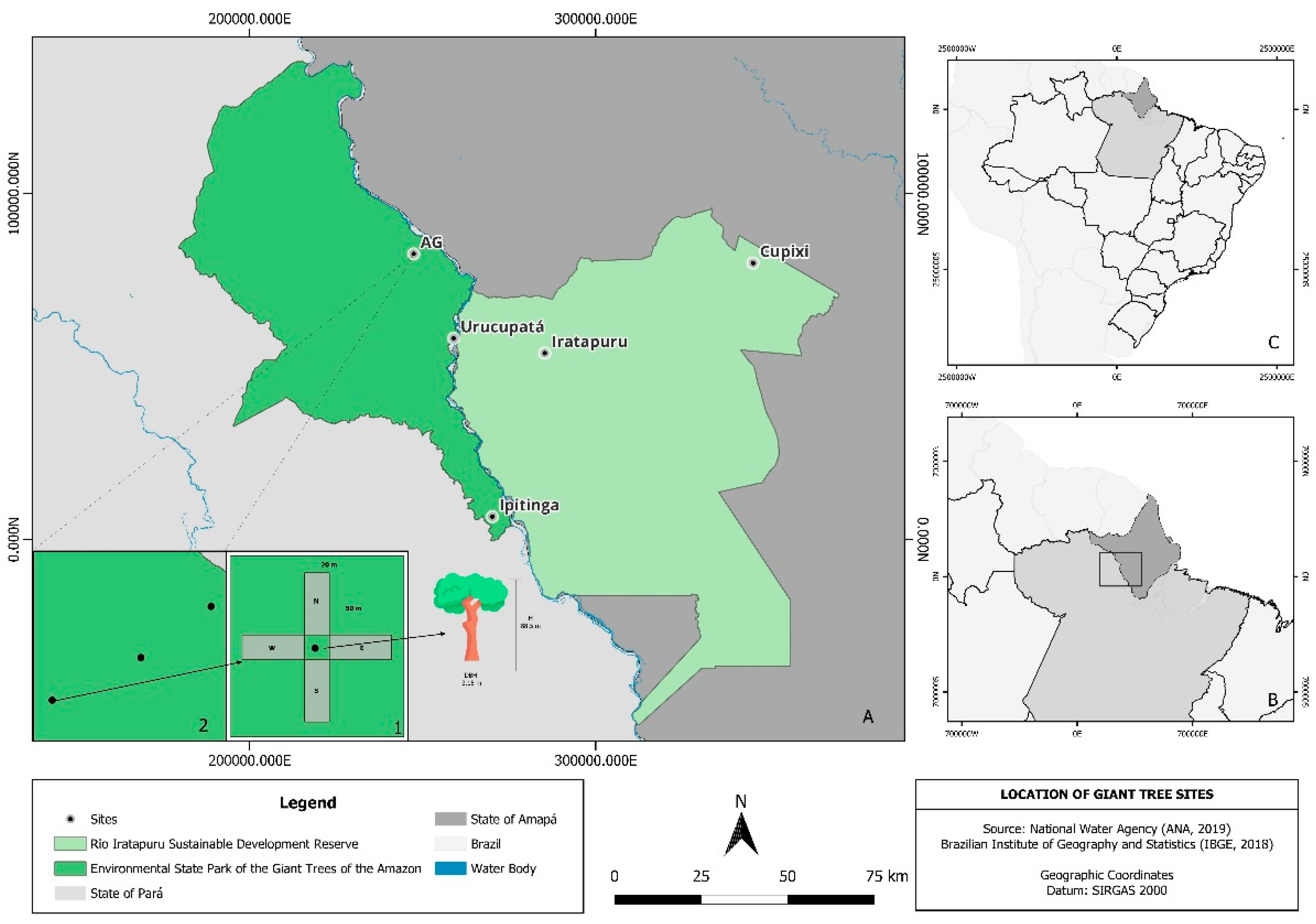

This study was conducted at five sites with a high occurrence of giant trees in the northern Amazon region [

6], located in the states of Amapá and Pará. Forest inventory and soil data were collected and analyzed between 2019 and 2024. Three of the study sites are located within the Environmental State Park of the Giant Trees of the Amazon (0°41′29″N, 53°28′41″W), and two sites are situated in the Rio Iratapuru Sustainable Development Reserve (0°19′05″N, 52°43′29″W) (

Figure 1).

Both areas are situated within the domain of Amazonian dense ombrophilous forest, under a climate classified as Af (Köppen), characterized by a humid equatorial regime with abundant rainfall throughout the year, mean annual temperatures above 25 °C, and total annual precipitation generally exceeding 2,500 mm [

15].

At each study area, three plots were established, each composed of four subplots (north, east, south, and west) measuring 20 × 50 m, with a giant tree serving as the central reference point (

Figure 1A). All woody individuals with a diameter at breast height (DBH) ≥ 10 cm were measured. Tree height was estimated using a hypsometer, except for the giant trees that served as central references for the clusters, whose heights were determined using LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) data [

10].

Botanical identification was performed with the assistance of experienced local parataxonomists, based on dendrological characteristics such as leaves, crown shape, trunk, and bark. Scientific names and families were validated using the Flora and Funga of Brazil database (

http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/). The geographic coordinates of each tree were recorded using a GPS receiver (Garmin 65 CSx).

Each subplot was subdivided into quadrants of 25 m², from which eight were systematically selected for soil sampling in the 0–20 cm layer. The simple samples were homogenized to form a composite sample representative of each subplot [

16]. Physical and chemical analyses were conducted at the EMBRAPA Soil Laboratories of Amapá and Pará, following the protocols established by [

17].

Biomass estimation was performed using regional allometric models implemented in the

BIOMASS package [

18]. The equation followed the allometric model developed by Chave et al. [

19], which incorporates as independent variables the diameter at breast height (DBH, in cm), tree height (H, in m), and wood density (WD, in g/cm³), expressed as:

where AGB represents the aboveground biomass of each tree (in kg). The total biomass of each sampling unit was converted to biomass per area (Mg/ha), considering the effective sampled area in each plot.

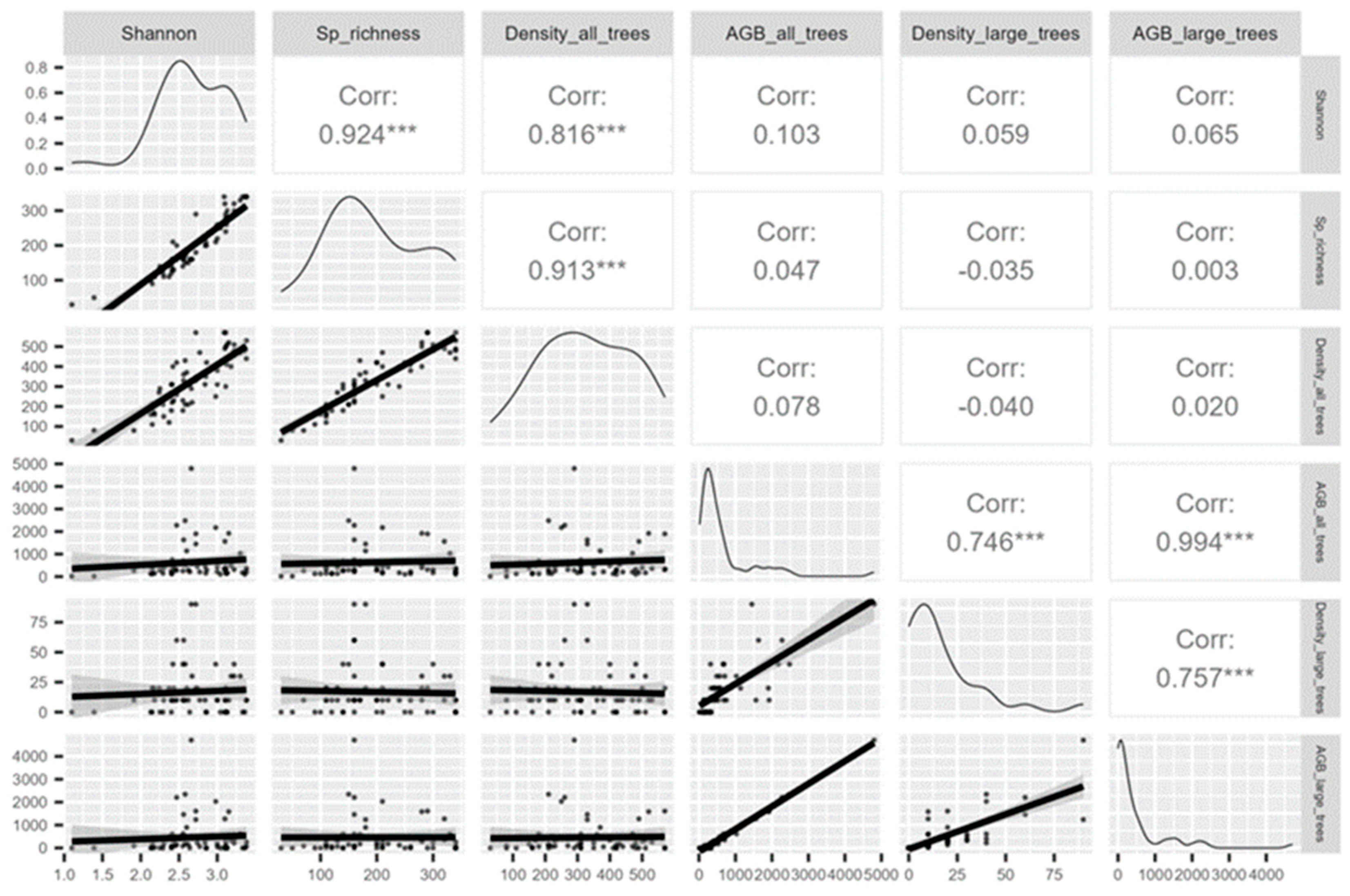

To assess the relationship between the biomass of trees with DBH ≥ 70 cm, overall floristic diversity (species richness and Shannon index), and forest structure (individual density), Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was applied.

To investigate the association between floristic composition and edaphic attributes across sites, a Redundancy Analysis (RDA) was performed. This multivariate ordination technique combines elements of Principal Component Analysis and multiple linear regression [

20], allowing the simultaneous evaluation of how multiple soil attributes explain variation in floristic composition among plots. The species abundance matrix was constructed based on species counts per plot and transformed using the Hellinger method [

21].

Continuous edaphic variables were standardized (mean = 0, standard deviation = 1) to ensure comparability among scales. To reduce multicollinearity among predictors, a

forward selection procedure based on statistical significance (p < 0.05) was applied using the

forward.sel function from the

adespatial package [

22]. The RDA was conducted using the rda() function of the

vegan package [

23]. The significance of canonical axes and individual predictor variables was tested using permutation tests (999 iterations). The adjusted coefficient of determination (

adjusted R²) was used to quantify the explanatory power of the model.

To evaluate whether the physical and chemical characteristics of the plots’ soils influenced the variation in large-tree biomass, a Generalized Linear Model (GLM) with Gamma distribution and log link function was initially fitted, which is suitable for continuous and strictly positive data. From the full model, edaphic variables were selected through a bidirectional stepwise procedure based on the Akaike Information Criterion (

AIC), in order to reduce collinearity among predictors and avoid model overfitting [

24]. The functions glm() and step() from the

stats package [

25] were used.

The variables selected through the stepwise procedure were subsequently employed to fit a Generalized Additive Model (GAM) with Gaussian family, which incorporates smoothing functions (splines) to model nonlinear relationships between soil attributes and tree biomass [

26]. This approach does not impose a rigid functional form on the relationships, providing greater flexibility for describing complex ecological patterns [

27]. The model was fitted using the gam() function of the

mgcv package [

26]. The analysis considered only plots with positive biomass values of large trees, excluding 17 plots with zero values to satisfy the assumptions of the Gamma distribution and focus inference on areas with the actual presence of these trees.

3. Results

The results indicate that biomass, particularly that of large trees, depends more strongly on the abundance of these individuals (r = 0.75,

p < 0.001) than on overall floristic diversity (

Figure 2). This outcome is expected, as biomass accumulation is directly related to the number of large-sized individuals present. A strong correlation was also observed between the biomass of large trees and the total forest biomass (r = 0.99,

p < 0.001), demonstrating that a small number of large trees concentrate a substantial proportion of the total biomass stock across the evaluated sites.

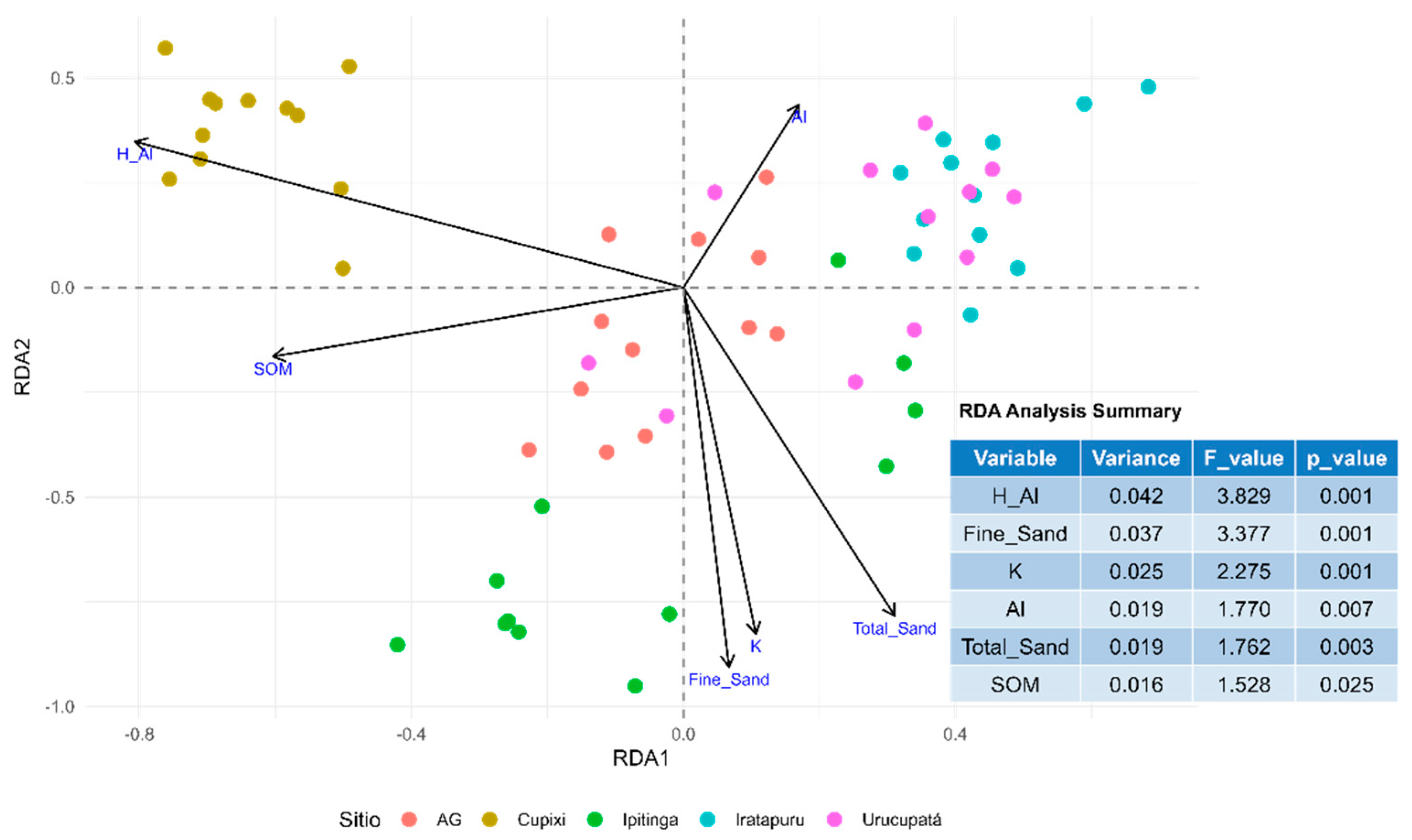

The Redundancy Analysis (RDA) revealed that six edaphic variables, potential acidity (H⁺ + Al³⁺), fine sand content, potassium (K⁺), aluminum (Al³⁺), total sand, and soil organic matter (SOM), jointly explained 21.5% of the variation in tree species composition (

Figure 3), with an adjusted R² of 12.6%. The canonical axes (RDA1 and RDA2) represent the main edaphic gradients among plots. RDA1 was associated with lower concentrations of H⁺ + Al³⁺ and SOM, and higher levels of Al³⁺, K⁺, total sand, and fine sand. In contrast, RDA2 was related to higher concentrations of H⁺ + Al³⁺ and Al³⁺, and lower values of SOM, K⁺, fine sand, and total sand.

All variables were significant (p < 0.001), indicating the presence of environmental gradients that influence species distribution. Among the analyzed sites, Cupixi stood out for its strong association with the potential acidity gradient (H⁺ + Al³⁺), positioned at the negative extreme of the RDA1 axis. All selected variables showed individual statistical significance, reinforcing that edaphic factors play a key role in shaping the floristic structure and composition of the studied area.

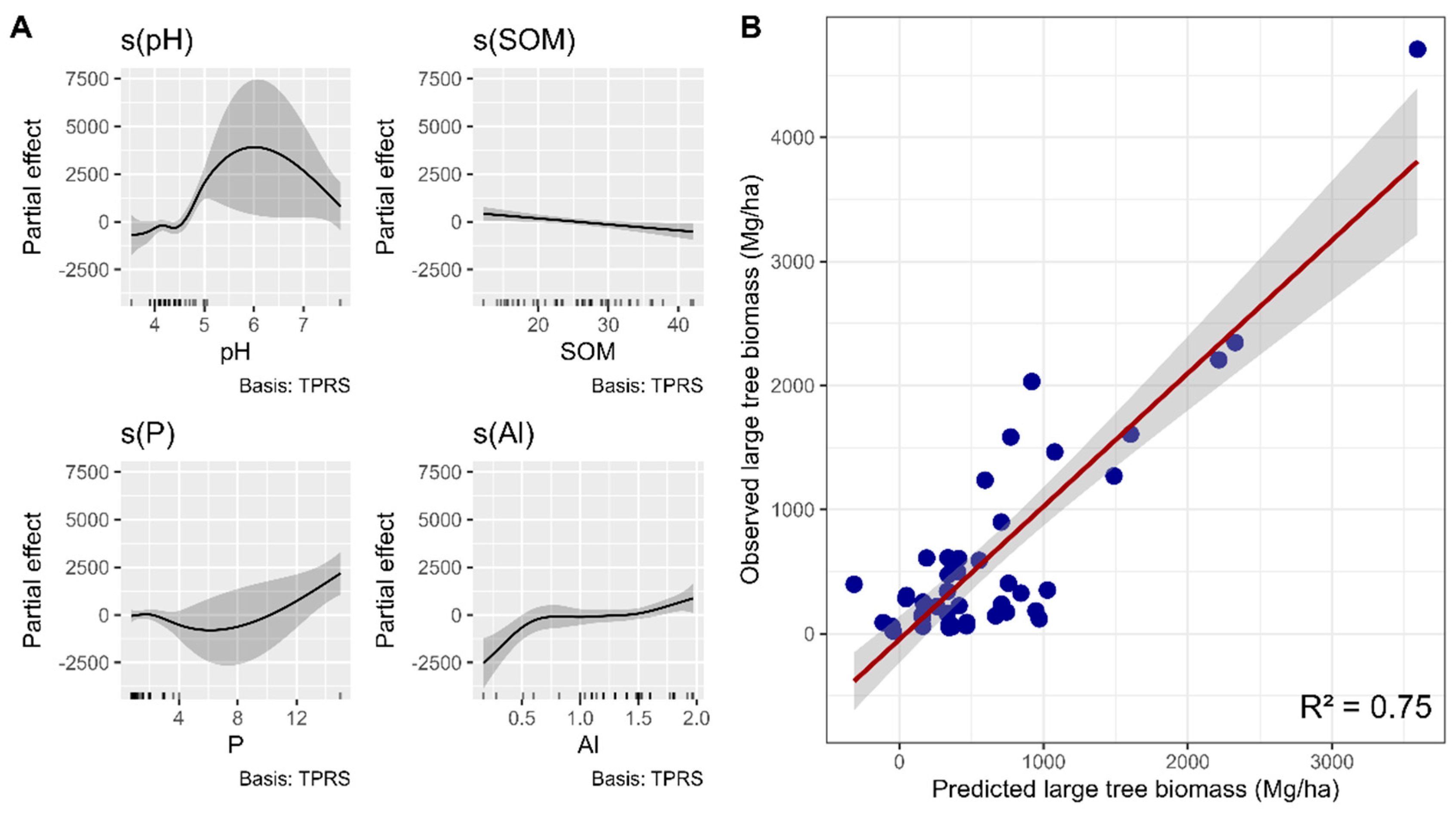

The GAM analysis examining the relationship between edaphic conditions and giant-tree biomass indicated that the soil variables pH, SOM, P, and Al³⁺ exhibited significant nonlinear effects on the biomass of giant trees. The model explained 74.6% of the total variance (adjusted pseudo-R² = 0.631), demonstrating a good fit to the data. Moreover, the analysis revealed nonlinear effects of soil pH, soil organic matter (SOM), phosphorus (P), and aluminum (Al³⁺) on the aboveground biomass of large trees (Mg/ha).

Figure 4.

Smoothed effects of the edaphic variables pH (p = 0.00107), SOM (p = 0.01410), P (p = 0.00426), and Al (p = 0.00235) on the biomass of large trees (DBH ≥ 70 cm) in the Eastern Amazon, according to the Generalized Additive Model (GAM) fitted for the states of Pará and Amapá, Brazil. Panel (A) displays the nonlinear effects of each soil attribute on biomass (Mg ha-1), while panel (B) shows the relationship between observed and predicted values. The model explained 74.6% of the total variance (adjusted pseudo-R² = 0.631).

Figure 4.

Smoothed effects of the edaphic variables pH (p = 0.00107), SOM (p = 0.01410), P (p = 0.00426), and Al (p = 0.00235) on the biomass of large trees (DBH ≥ 70 cm) in the Eastern Amazon, according to the Generalized Additive Model (GAM) fitted for the states of Pará and Amapá, Brazil. Panel (A) displays the nonlinear effects of each soil attribute on biomass (Mg ha-1), while panel (B) shows the relationship between observed and predicted values. The model explained 74.6% of the total variance (adjusted pseudo-R² = 0.631).

4. Discussion

Total biomass was strongly related to the abundance of large trees, confirming the pattern of biomass hyperdominance in the Amazon [

8]. This phenomenon reflects the disproportionate contribution of a few individuals to the total aboveground biomass stock, indicating that emergent trees play a central structural role in the stability and functioning of the ecosystem [

13,

28]. In some sites, a single individual accounted for up to 82% of the living biomass, supporting previous studies that emphasize the importance of large trees as key carbon reservoirs and regulators of forest dynamics [

6].

Potential acidity, fine sand, potassium, aluminum, total sand, and soil organic matter explained a significant portion of the variation in total species composition. This pattern reflects the naturally low fertility of Amazonian soils [

29], which limits both diversity and growth, consistent with studies highlighting the direct influence of edaphic properties on species composition and distribution [

30,

31,

32]. The strong association of the Cupixi site with potential acidity (H⁺ + Al³⁺) suggests that the higher soil acidity in Cupixi may be related to its lower species richness (Figure S1), reflecting more restrictive edaphic conditions for regeneration and species coexistence.

Among the analyzed attributes, soil pH emerged as one of the most relevant predictors, with a marked increase in biomass observed between values of 3.6 and 6.0. This trend can be explained by the role of pH in regulating nutrient availability [

33,

34]. Such a pattern aligns with studies reporting an association between lower soil acidity and higher aboveground biomass production [

35,

36], as pH directly influences the availability of essential nutrients [

33,

37]. At the Amazonian scale, this suggests that areas with soils within the aforementioned pH range may function as productivity hotspots, indicating that even small variations in acidity can induce substantial biomass responses.

Total phosphorus behaved as a limiting nutrient, with a marked increase in biomass above the threshold of 7.09 mg kg⁻¹, beyond which biomass accumulation rose sharply. This finding suggests the existence of a functional phosphorus threshold. The pattern is consistent with previous studies identifying total phosphorus as the main edaphic factor related to coarse wood production in the Amazon [

31]. Therefore, the increase in biomass observed above this threshold indicates that the total phosphorus reservoir is a key determinant of sustained growth in large trees. The study region lies predominantly on dystrophic Oxisols and Ultisols [

38,

39], typically oxidic soils characterized by low phosphorus availability, low cation-exchange capacity (CEC), and high aluminum content [

29]. These conditions constrain nutrient availability and explain the strong influence of phosphorus on biomass variation. The phosphorus range identified in this study therefore represents an optimal availability window, capable of sustaining the growth of large trees even in highly weathered soils.

Aluminum exhibited a positive response to biomass within the range of 0.18 to 1.97 cmolc kg

-1, indicating physiological tolerance or adaptive mechanisms of Amazonian species to acidic soils. Studies have shown that some aluminum-tolerant plants can modify cell wall composition and employ specific transporters that sequester aluminum into vacuoles, where it becomes isolated and loses its toxic effect [

40]. This ability may enhance the performance of species adapted to acidic soils, particularly light-demanding species, for which aluminum has been shown to correlate positively with growth [

41]. Collectively, these findings suggest that certain Amazonian species have developed adaptive strategies to thrive in acidic soils.

The relationship with soil organic matter (SOM) remained relatively stable along the gradient, indicating that, despite its central role in fertility, it did not emerge as a limiting variable for biomass. SOM functions as a strategic reservoir of nutrients for both plants and microorganisms [

42]. Its maintenance strongly depends on litter input and decomposition processes, which are regulated by litter quality and environmental conditions [

35]. However, the dynamics of litter production and decomposition in tropical forest ecosystems are complex and still poorly understood [

43]. This stability suggests that the biomass of large trees responds less to short-term fluctuations in SOM and more to long-term processes related to nutrient cycling, key mechanisms underpinning the resilience of Amazonian ecosystems.

In summary, the biomass of large trees in the Amazon also results from the interaction between edaphic composition and the functional responses of species along soil gradients. This relationship highlights the role of soil as a structuring component of ecological heterogeneity and reinforces the need to integrate edaphic parameters into predictive models and management policies aimed at conserving high-biomass tropical forests.

5. Conclusions

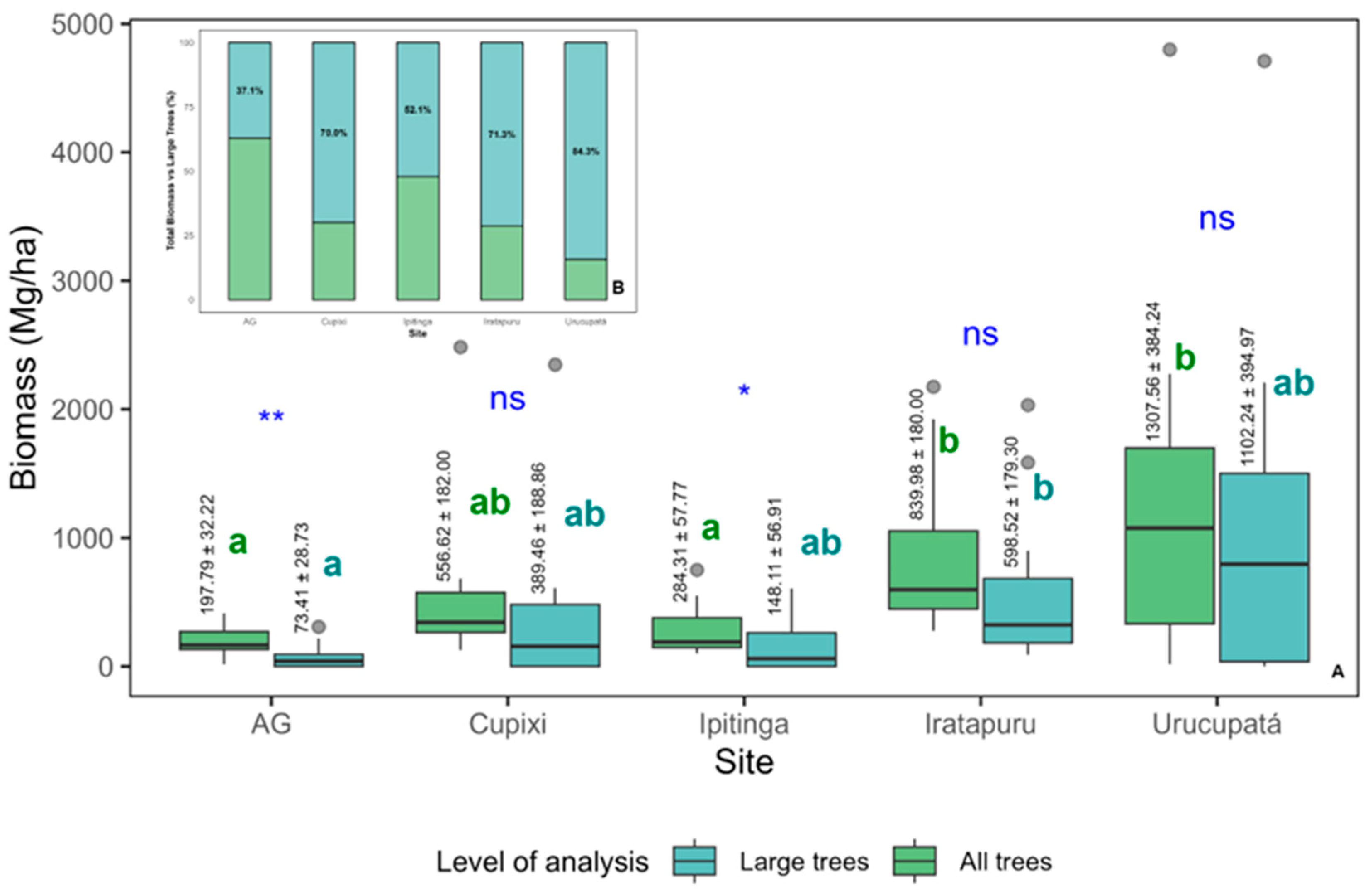

Amazonian giant trees stand out as key structural elements, accounting for a disproportionate share of the forest’s biomass and carbon stocks. In some sites, these individuals concentrated more than 80% of the total biomass (

Figure A1), underscoring their essential role in regulating forest dynamics and maintaining ecosystem stability and services.

Our results also demonstrate that edaphic attributes such as pH, phosphorus, and aluminum are associated with the occurrence and biomass of these trees. This pattern indicates that conserving areas with a high density of large individuals should be a priority in forest management and climate policies, as their loss would compromise the resilience of the Amazon forest.

Author Contributions

Data curation, M.P.; Formal analysis, M.P., J.R.B. and D.A.S.; Investigation, M.P., J.R.B. and D.A.S.; Methodology, M.P., J.R.B., D.A.S. and R.L.; Project administration, D.A.S. and R.L.; Supervision, D.A.S. and J.R.B.; Writing—original draft preparation, M.P. and J.R.B.; Writing—review and editing, M.P., D.A.S., J.R.B., R.L., E.G., M.G., G.A., P.B., J.S., C.S., J.P.S., and E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the Universidade do Estado do Amapá — UEAP.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study include geographic coordinates and ecological information regarding the occurrence of giant trees within protected areas. Due to the sensitive nature of these data and conservation restrictions, they are not publicly available. Data can be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with authorization from the managing institutions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Long-Term Ecological Research Program: Integrated Monitoring of Amazonian Giant Trees for its scientific, logistical, and field support throughout this study. We also acknowledge the collaboration of local communities from Rio Iratapuru Sustainable Development Reserve for facilitating access to the study areas. We further thank the EMBRAPA Soil Laboratory for conducting physical and chemical analyses, and the parataxonomists who contributed to botanical identifications and the Instituto de Desenvolvimento Florestal e da Biodiversidade (Ideflor-Bio) for providing access to soil data that supported this research. The authors have reviewed and edited all generated content and take full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

The biomass of all trees and the biomass of large trees also showed significant variations among the evaluated sites, following a similar pattern (Figure 6A). When comparing the two levels within each site, no statistically significant differences were observed between the mean biomass values of all trees and those of large trees alone in Urucupatá, Iratapuru, and Cupixi. This finding reinforces the idea that, in these locations, large trees account for a large proportion of the stored biomass.

Figure A1.

The biomass of all trees and that of large trees also showed significant variation among the evaluated sites, following a similar pattern. When comparing the two levels within each site, no statistically significant differences were observed between the mean biomass of all trees and that of large trees alone in Urucupatá, Iratapuru, and Cupixi. This finding reinforces the idea that, in these locations, large trees are responsible for a substantial share of the stored biomass.

Figure A1.

The biomass of all trees and that of large trees also showed significant variation among the evaluated sites, following a similar pattern. When comparing the two levels within each site, no statistically significant differences were observed between the mean biomass of all trees and that of large trees alone in Urucupatá, Iratapuru, and Cupixi. This finding reinforces the idea that, in these locations, large trees are responsible for a substantial share of the stored biomass.

The relative importance of large trees in the composition of forest biomass varied considerably among the evaluated sites. In Urucupatá, 84.3% of the total biomass of all trees was attributed to large trees, followed by Iratapuru (71.3%), Cupixi (70.0%), and Ipitinga (52.1%). These results suggest that, in some sites, large trees play a dominant role in the structure and accumulation of forest biomass.

References

- Marengo, J.A.; Souza, C.M.; Thonicke, K.; Burton, C.; Halladay, K.; Betts, R.A.; Alves, L.M.; Soares, W.R. Changes in Climate and Land Use Over the Amazon Region: Current and Future Variability and Trends. Frontiers in Earth Science 2018, 6, 228. [CrossRef]

- Quesada, C.A.; Paz, C.; Oblitas Mendoza, E.; Phillips, O.L.; Saiz, G.; Lloyd, J. Variations in Soil Chemical and Physical Properties Explain Basin-Wide Amazon Forest Soil Carbon Concentrations. SOIL 2020, 6, 53–88. [CrossRef]

- Pinho, B.X.; Peres, C.A.; Leal, I.R.; Tabarelli, M. Chapter Seven - Critical Role and Collapse of Tropical Mega-Trees: A Key Global Resource. In Advances in Ecological Research; Dumbrell, A.J., Turner, E.C., Fayle, T.M., Eds.; Tropical Ecosystems in the 21st Century; Academic Press, 2020; Vol. 62, pp. 253–294.

- Enquist, B.J.; Abraham, A.J.; Harfoot, M.B.J.; Malhi, Y.; Doughty, C.E. The Megabiota Are Disproportionately Important for Biosphere Functioning. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 699. [CrossRef]

- de Lima, R.B.; Görgens, E.B.; da Silva, D.A.S.; de Oliveira, C.P.; Batista, A.P.B.; Caraciolo Ferreira, R.L.; Costa, F.R.C.; Ferreira de Lima, R.A.; da Silva Aparício, P.; de Abreu, J.C.; et al. Giants of the Amazon: How Does Environmental Variation Drive the Diversity Patterns of Large Trees? Global Change Biology 2023, 29, 4861–4879. [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.B. de; Silva, D.A.S. da; Nunes, M.H.; Bittencourt, P.R. de L.; Groenendijk, P.; Oliveira, C.P. de; Souza, D.G. de; Ferreira, R.L.C.; Silva, J.A.A. da; Aguirre-Gutiérrez, J.; et al. Mapping Giant-Tree Density in the Amazon 2025, 2025.02.25.640223.

- Harris, D.J.; Ndolo Ebika, S.T.; Sanz, C.M.; Madingou, M.P.N.; Morgan, D.B. Large Trees in Tropical Rain Forests Require Big Plots. PLANTS, PEOPLE, PLANET 2021, 3, 282–294. [CrossRef]

- Slik, J.W.F.; Paoli, G.; McGuire, K.; Amaral, I.; Barroso, J.; Bastian, M.; Blanc, L.; Bongers, F.; Boundja, P.; Clark, C.; et al. Large Trees Drive Forest Aboveground Biomass Variation in Moist Lowland Forests across the Tropics. Global Ecology and Biogeography 2013, 22, 1261–1271. [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.; Murphy, H.T. The importance of large-diameter trees in the wet tropical rainforests of Australia. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0208377. [CrossRef]

- Gorgens, E.B.; Motta, A.Z.; Assis, M.; Nunes, M.H.; Jackson, T.; Coomes, D.; Rosette, J.; Aragão, L.E.O.E.C.; Ometto, J.P. The Giant Trees of the Amazon Basin. Frontiers in Ecol & Environ 2019, 17, 373–374. [CrossRef]

- Draper, F.C.; Costa, F.R.C.; Arellano, G.; Phillips, O.L.; Duque, A.; Macía, M.J.; ter Steege, H.; Asner, G.P.; Berenguer, E.; Schietti, J.; et al. Amazon Tree Dominance across Forest Strata. Nat Ecol Evol 2021, 5, 757–767. [CrossRef]

- Fauset, S.; Johnson, M.O.; Gloor, M.; Baker, T.R.; Monteagudo M., A.; Brienen, R.J.W.; Feldpausch, T.R.; Lopez-Gonzalez, G.; Malhi, Y.; ter Steege, H.; et al. Hyperdominance in Amazonian Forest Carbon Cycling. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 6857. [CrossRef]

- Lutz, J.A.; Furniss, T.J.; Johnson, D.J.; Davies, S.J.; Allen, D.; Alonso, A.; Anderson-Teixeira, K.J.; Andrade, A.; Baltzer, J.; Becker, K.M.L.; et al. Global Importance of Large-Diameter Trees. Global Ecology and Biogeography 2018, 27, 849–864. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, R.L.; Resende, A.F.; Barlow, J.; França, F.M.; Moura, M.R.; Maciel, R.; Alves-Martins, F.; Shutt, J.; Nunes, C.A.; Elias, F.; et al. Pervasive Gaps in Amazonian Ecological Research. Current Biology 2023, 33, 3495-3504.e4. [CrossRef]

- Alvares, C.A.; Stape, J.L.; Sentelhas, P.C.; Leonardo, J.; Gonçalves, M.; Sparovek, G. Köppen’s Climate Classification Map for Brazil. Meteorologische Zeitschrift 2013, 26, 711–728. [CrossRef]

- Guarçoni, A.; Alvarez V., V.H.; Sobreira, F.M.; Guarçoni, A.; Alvarez V., V.H.; Sobreira, F.M. Fundamentação teórica dos sistemas de amostragem de solo de acordo com a variabilidade de características químicas. Terra Latinoamericana 2017, 35, 343–352.

- Teixeira, P. C.; Donagemma, G. K.; Fontana, A.; Teixeira, W. G. Manual de Métodos de Análise de Solo; Embrapa Solos, 2017.

- Réjou-Méchain, M.; Tanguy, A.; Piponiot, C.; Chave, J.; Hérault, B. Biomass: An r Package for Estimating above-Ground Biomass and Its Uncertainty in Tropical Forests. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2017, 8, 1163–1167. [CrossRef]

- Chave, J.; Réjou-Méchain, M.; Búrquez, A.; Chidumayo, E.; Colgan, M.S.; Delitti, W.B.C.; Duque, A.; Eid, T.; Fearnside, P.M.; Goodman, R.C.; et al. Improved Allometric Models to Estimate the Aboveground Biomass of Tropical Trees. Global Change Biology 2014, 20, 3177–3190. [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P.; Legendre, L. Numerical Ecology; Elsevier, 2012; ISBN 978-0-444-53869-7.

- Legendre, P.; Gallagher, E.D. Ecologically Meaningful Transformations for Ordination of Species Data. Oecologia 2001, 129, 271–280. [CrossRef]

- Dray, S.; David, B.; Guillaume, B.; Daniel, B.; Sylvie, C.; Guillaume, G. Adespatial: Multivariate Multiscale Spatial Analysis 2016, 0.3-28.

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.; Friendly, M.; Kindt, R. Vegan: Community Ecology Package (R Package Version 2.5–5). 2019.

- Advanced Issues and Deeper Insights. In Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach; Burnham, K.P., Anderson, D.R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, 2002; pp. 267–351 ISBN 978-0-387-22456-5.

- Team R Core R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2024.

- Wood, S. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R; CRC press, 2017.

- Guisan, A.; Zimmermann, N.E. Predictive Habitat Distribution Models in Ecology. Ecological Modelling 2000, 135, 147–186. [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, N.L.; Das, A.J.; Condit, R.; Russo, S.E.; Baker, P.J.; Beckman, N.G.; Coomes, D.A.; Lines, E.R.; Morris, W.K.; Rüger, N.; et al. Rate of Tree Carbon Accumulation Increases Continuously with Tree Size. Nature 2014, 507, 90–93. [CrossRef]

- Luizão, F.J.; Fearnside, P.M.; Cerri, C.E.P.; Lehmann, J. The Maintenance of Soil Fertility in Amazonian Managed Systems. In Geophysical Monograph Series; Keller, M., Bustamante, M., Gash, J., Silva Dias, P., Eds.; American Geophysical Union: Washington, D. C., 2009; Vol. 186, pp. 311–336 ISBN 978-0-87590-476-4.

- Quesada, C.; Lloyd, J.; Schwarz, M.; … S.P.-; 2010, undefined Variations in Chemical and Physical Properties of Amazon Forest Soils in Relation to Their Genesis. bg.copernicus.org 2010, 7, 1515–1541. [CrossRef]

- Quesada, C.A.; Phillips, O.L.; Schwarz, M.; Czimczik, C.I.; Baker, T.R.; Patiño, S.; Fyllas, N.M.; Hodnett, M.G.; Herrera, R.; Almeida, S.; et al. Basin-Wide Variations in Amazon Forest Structure and Function Are Mediated by Both Soils and Climate. Biogeosciences 2012, 9, 2203–2246. [CrossRef]

- Sayer, E.J.; Banin, L.F. Tree Nutrient Status and Nutrient Cycling in Tropical Forest—Lessons from Fertilization Experiments. Tropical Tree Physiology 2016, 6, 275–297. [CrossRef]

- McCauley, A.; Jones, C.; Jacobsen, J. Soil pH and Organic Matter. 2009.

- Poggio, L.; de Sousa, L.M.; Batjes, N.H.; Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Kempen, B.; Ribeiro, E.; Rossiter, D. SoilGrids 2.0: Producing Soil Information for the Globe with Quantified Spatial Uncertainty. SOIL 2021, 7, 217–240. [CrossRef]

- van der Sande, M.T.; Arets, E.J.M.M.; Peña-Claros, M.; Hoosbeek, M.R.; Cáceres-Siani, Y.; van der Hout, P.; Poorter, L. Soil Fertility and Species Traits, but Not Diversity, Drive Productivity and Biomass Stocks in a Guyanese Tropical Rainforest. Functional Ecology 2018, 32, 461–474. [CrossRef]

- Hornink, B.; Zuidema, P.A.; van der Sleen, P.; Zanne, A.E.; Assis-Pereira, G.; Ortega Rodriguez, D.R.; Fontana, C.; Portal-Cahuana, L.A.; Requena-Rojas, E.J.; Barbosa, A.C.M.C.; et al. Biomass Production of Tropical Trees across Space and Time: The Shifting Roles of Diameter Growth and Wood Density. Journal of Ecology 2025, n/a. [CrossRef]

- Isa, N.; Razak, S.A.; Abdullah, R.; Khan, M.N.; Hamzah, S.N.; Kaplan, A.; Dossou-Yovo, H.O.; Ali, B.; Razzaq, A.; Wahab, S.; et al. Relationship between the Floristic Composition and Soil Characteristics of a Tropical Rainforest (TRF). Forests 2023, 14, 306. [CrossRef]

- Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics - IBGE Amapá – Mapa Exploratório de Solos Em Escala 1:5.000.000 Available online: https://geoftp.ibge.gov.br/informacoes_ambientais/pedologia/mapas/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics - IBG Pará – Mapa Exploratório de Solos Em Escala 1:5.000.000 Available online: https://geoftp.ibge.gov.br/informacoes_ambientais/pedologia/mapas/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Kochian, L.V.; Piñeros, M.A.; Liu, J.; Magalhaes, J.V. Plant Adaptation to Acid Soils: The Molecular Basis for Crop Aluminum Resistance. 2015, 66, 571–598. [CrossRef]

- Reategui-Betancourt, J.L.; Freitas, L.J.M. de; Nascimento, R.G.M.; Briceño, G.; Figueiredo, A.E.S.; Rezende, A.V.; Alder, D. Species Grouping and Diameter Growth of Trees in the Eastern Amazon: Influence of Environmental Factors after Reduced-Impact Logging. Forest Ecology and Management 2025, 578, 122465. [CrossRef]

- Lange, D.F.; Schröter, S.A.; da Luz, F.M.; Pires, E.; Santos, Y.R.; da Silva, J.S.; Hildmann, S.; Hoffmann, T.; Ferreira, S.J.F.; Schäfer, T.; et al. Cycling of Dissolved Organic Nutrients and Indications for Nutrient Limitations in Contrasting Amazon Rainforest Ecosystems. Biogeochemistry 2024, 167, 1567–1588. [CrossRef]

- Giweta, M. Role of Litter Production and Its Decomposition, and Factors Affecting the Processes in a Tropical Forest Ecosystem: A Review. j ecology environ 2020, 44, 11. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).