Submitted:

16 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

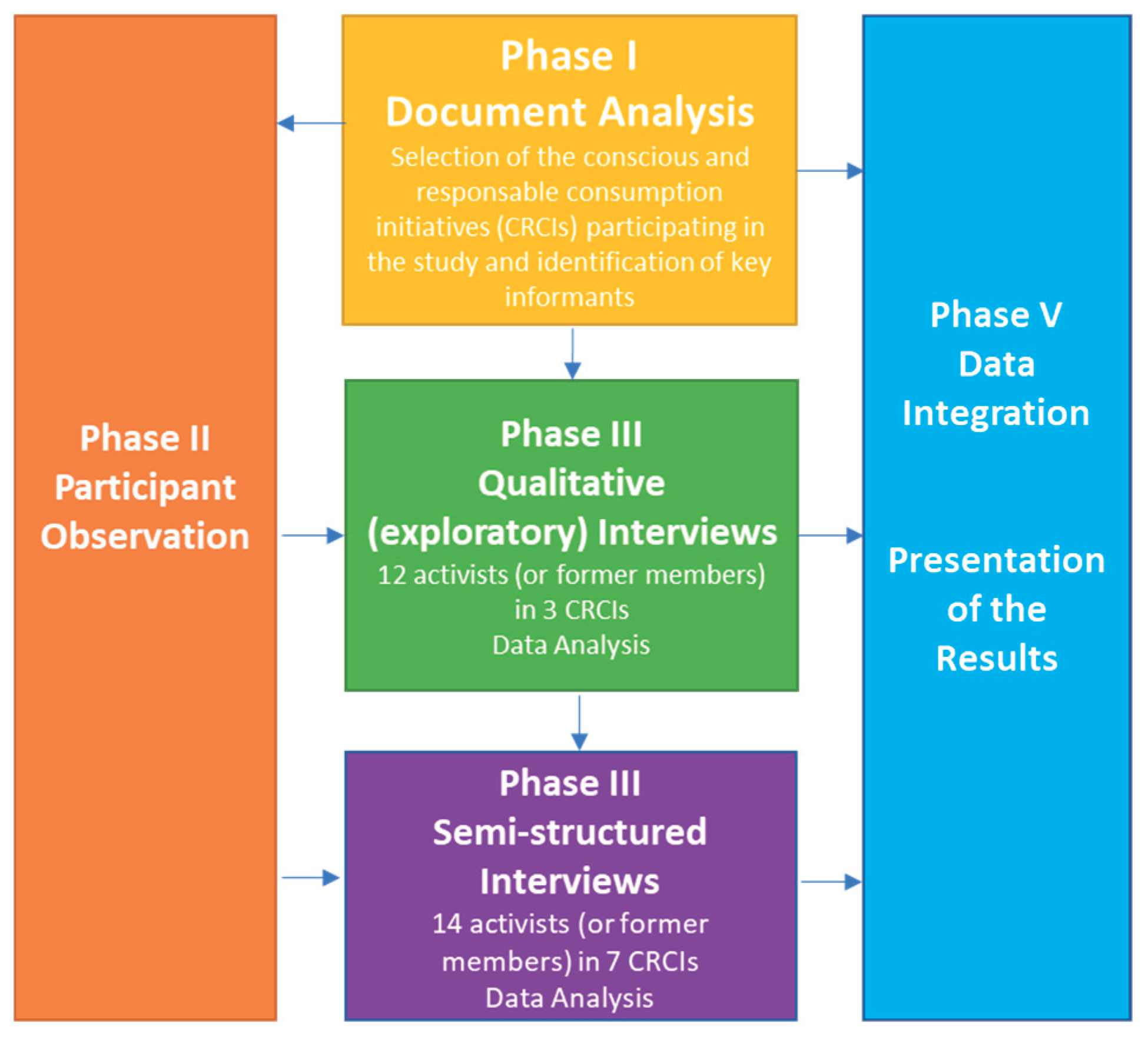

Considering sustainable consumption not just as an exercise of individual choice but a shared and collective activity, the study explores the role of conscious and responsible consumption initiatives (CRCIs) driving citizen´s adoption of sustainable lifestyles. The research followed a qualitative approach, combining documentary research and twenty-six in-depth interviews with practitioners in eight grassroots consumer initiatives located in Galicia (Spain). The results show that CRCIs favor members’ consumption of organic, seasonal, fair, and locally-produced food. The findings also reveal that engagement in these initiatives nurtures three interconnected types of learning—cognitive, attitudinal, and behavioral—which contributes to wider adoption of sustainable practices related to shifts in dietary habits, energy use, mobility, and frugality. CRCIs facilitate gradual transitions toward reduced meat consumption, favoring the intake of plant-based foods, and greater self-efficacy in preparing sustainable meals. These behavioral changes are incremental, motivated by inner re-flection, practical experience, and consciousness around alternative economic models. However, the consistent adoption of sustainable eating habits is hindered by cultural and psychological barriers like cultural traditions, entrenched habits, and time affluence. In conclusion, these grassroots initiatives are interesting entry points for engaging citizens in sustainable lifestyles, becoming also gateways to the broader social and solidarity economy movement.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Addressing Sustainable Food Consumption to Meet Zero-Net Goals

1.2. The Role of Grassroots Social Innovations in Sustainable Transitions

1.3. Social Learning Approaches in Transformative Social Innovations in the Food Domain

2. Research Goals, Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study Approach and Research Goals

- What are the consumption styles of practitioners involved in these grassroots food initiatives and to what extend food-coops are able to satisfying people´s needs?

- What are the conditions and dimensions that foster or inhibit food activists´ endeavors to consume sustainably in the food domain? To what extent are conscious and responsible consumption initiatives able to satisfy consumer´s food needs?

- What types of learning phenomena rise in these participatory contexts?

- To what extent do social learning processes influence or foster practitioner´s wider adoption of green lifestyles?

- To delve into the goals, functioning and main characteristics of the Galician Conscious and Responsible Consumption Network.

- To study the food consumption styles developed by the members of the CRCIs

- To explore the main barriers and constraints that inhibit the adoption of low-carbon consumption in the food domain.

- To explore the learning processes nurtured in the participatory context of consumer initiatives and the outcomes in terms of positive behavioral spillover regarding sustainable lifestyles adoption.

2.2. Materials and Sample Description

2.3. Data Analysis Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Origin, Goals, Functioning and Main Characteristics of the Galician Conscious and Responsible Consumption Network

3.2. Practitioners ‘Patterns of Food Consumption and Dietary Choices

I usually go to the regular supermarket to buy other goods but food. For example, cleaning products. I do not buy them in organic stores because they are excessively expensive and difficult to find (Sara, Semente).

3.3. Consumption Spaces of Preference for Food Activists

The cooperative is able to satisfy weekly demands for the collection of organic foods, and we accomplish this like clockwork; it works extremely well (Alba, Zocamiñoca).

The initiative is able to cover a wide range of product demands that extend beyond fresh, local produce. This includes canned goods, pasta, flours, bulk legumes, as well as ecological cleaning and hygiene products, with the guarantee that they are not harming the planet (Diana, Millo Miúdo).

Yes, I try to buy at the market, not in large retail stores. I try to know whom I’m buying. Even for clothes, small shops — we really try at home to be consistent with that (Gabriela, Panxea).

About 80% of what I spend monthly on groceries I buy at Árbore, and the other 20% are products I can’t find there, so I go to supermarkets to get them. If I find them in other supermarkets, I try to make sure they are also organic. Now it seems to be kind of trendy. You go to any superstore and they have a whole aisle for organic products. And I try to buy those (Tomás, Árbore).

The fact that the coop exists and that makes accessible these products easier, has clearly shifted my shopping basket and our weekly grocery spending toward this type of product. I can’t tell you exactly, but right now, our weekly shopping — perishable and everyday items like plant-based milk and cereals are, I would say about 70% we buy here in Aldea. And it wasn’t like that at all at the beginning. Before, it was more of a complement — I would do my usual shopping elsewhere but come here for those rare or hard-to-find products. Then one day I realized and told my husband: look, it has been a month since we last went to a supermarket! (Patricia, Aldea)

3.4. Barriers and Constraints Undermining Individual´s Efforts for Sustainable Eating Practices

3.4.1. The Role of Long-Term Culinary Traditions and Meat-Based Gastronomy as Part of Proud Deep-Rooted Local Cultures

“If someone wants chorizo, there is no problem, I will prepare it. But I do the family menu, I organize it, and at home it is exceedingly difficult to find meat. My husband is not a vegetarian. No problem. My children are not, either, but it is true that they have adapted to this type of diet and are in good health. If they go to the grandparents' house at weekend and there is pork with green turnip, they eat it and enjoy it, and nothing happens"(Patricia, Aldea).

That is a work that you may have to do at a certain moment, to reaffirm yourself in certain things, such as being vegan. In my case, it was nothing traumatic, or anything, they respected me. Fortunately, my closest family are very respectful people, even if they do not share my lifestyles, they did not try to influence me negatively. I see that they positively value certain things that I can do and that they learned it and do it as well, instead of rejecting it. There are many things that My parents recognize that being in contact with this world has been positive (Fabio, Zocamiñoca).

3.4.2. Well-Established Eating Habits and Routines that Are Difficult to Tackle

Changing eating habits it is a substantial change, one of the most difficult to make (…) Is something not easy, but rather challenging (Brais, Zocamiñoca),

Eating organic is one thing but eating seasonal and local is another. There are people who still want tomatoes all year round (Brais, Zocamiñoca).

(Q) How would you say your consumption style? Do you mostly purchase in Árbore or do you go other establishments? (A) I see it as progression because it’s exceedingly difficult. Changing from shopping at big supermarkets to completely avoiding them, not purchasing in big corporations, and buying everything organic, is quite a drastic change. In my case, I started slowly. You can’t do it all at once. You are also used to certain things (Tomás, Arbore).

3.4.3. Perceived Time Pressure

Does time matters? Yes. I have two children and when I have just given birth, there were a few months that I did not have time to buy fresh vegetables, or even to cut them. There are periods of time when I noticed the lack of time and I solved it out by buying frozen vegetables at supermarket (Elisa, Millo Miúdo).

(The food coop) was far away, and distance is a factor that also matters, because it took me to reach the organic shop about half an hour from home on foot. At that time, I didn't have much time either, it required an enormous effort to go there and pick the basket up. In the end, the shop only supplied half of the things I needed (Gabriela, Panxea).

3.5. Cognitive, Attitudinal, and Practical Learning Nurtured in Conscious and Responsible Consumption Initiatives

3.5.1. Cognitive Learning: Deep Understanding of the Functioning and Socio-Environmental Impact of the Global Food System and Worldviews Change

In Zocamiñoca I realized to what extent it is important to consume. That is, one as an individual can have influence through our consumption choices... Right now, it seems to me that we achieve more impact with our consumption habits than just with our vote. It is not that I consider it important to vote and participate on a social level, but it seems more diluted. Otherwise, once you put your grain of sand, which is tiny, but you are supporting the rural to move forward, we help three or four farmers. Once you realize that there is a change, you see that your way of consuming is meaningful (Iria, Zocamiñoca).

Every week, the people who consume here do something that connects them. You’re not carrying out a protest act, but you’re protesting in another way. And it’s every week. Every week. Every week. And of course, it is a place that defends certain principles” (Fabio, Zocamiñoca).

Zocamiñoca represents, in its total humility, a form of activism without being explicit activism. It is subtle, daily, indispensable, even though they do not explicitly engage in activism or pedagogy (Ernesto, Zocamiñoca).

Caring each other, fostering real channels for participation, and transparency helped newcomers to feel included (Gael, Zocamiñoca).

We did not want an exclusive group of convinced people, as this would exclude others. Participation needed to be feasible and inclusive (Fabio, Zocamiñoca).

Some people might think that cooperatives or eco-stores must be vegetarian—but we are not. We respect vegetarians and vegans very much, but we also welcome people who eat meat or fish (Olivia, Aldea)

Intermediate solutions do exist. In intentional communities, vegan, vegetarian, and omnivorous options coexist, influencing each other without isolation (Gael, Zocamiñoca).

3.5.2. Attitudinal Change Towards Alternative and Plant-Based Dietary Styles

People is curious about these new lifestyles, and encourage themselves to try something new, they wonder if they are capable of (Daniela, Zocamiñoca).

New members learn other ways of doing things and that “one can be fed in another way (Helena, Zocamiñoca).

New members observe that things can be done differently, that there are alternatives (…) That you can organize yourself in another way (Alba, Zocamiñoca).

3.5.3. Behavioral Learning and De-Learning Process Crucial for Adoption of Plant-Based Diets

I don't know how to tell you, but we ate meat and chicken, I don't know if every day of the week. We used to eat meat and fish, which is like you feel healthier, say three days I eat meat, three fish, but there were no days when you only ate vegetables, or legumes. And that was gradually changing, in fact, we turned it around. In fact, it was quite natural. As I ate more vegetables, more legumes, well, I cooked other menus, and the consumption of meat became anecdotal, and at a certain point, it was linked to an ethical commitment. If I can be healthy without killing an animal that feels, thinks, and suffers, well, I'm not going to do it (Daniela, Zocamiñoca).

I had flaked oats from the cooperative, I had freshly bought nuts from the cooperative, I had agave syrup, and we made some wonderful cookies with nuts that we had for breakfast this morning and that is really a satisfaction, as a mother, as a member of the cooperative, as a consumer. For health, for economy, for ecology, for me, that is all positive, in every way (Patricia, Aldea).

In case of my friends, who did not have a special sensitivity or anything, nor did they reflect much on the matter, nor read a lot, on the matter of food, but at a certain moment, they get involved. And I see that little by little they are changing things, habits, of course. I don't romanticize it much, either. Because creating this opportunity is important, but there must be a work of sensitivity and quite personal motivation (Fabio, Zocamiñoca).

3.5.4. Positive Behavioral Spillover: Towards More Frugal and Self-Sufficient Lifestyles in Different Settings and Contexts

Now I follow the same pattern of consumption. I should find a sustainable substitute for everything. When you go to superstores, I also see sustainable alternatives, so such alternatives do really exist. Elsewhere. For example, not long ago, C&A had a line of organic cotton clothing. Well, if they have it, someone else has it. And someone has decided to create green fashion, and I searched where can I buy it. For example, now on Facebook I follow a responsible Galician fashion initiative, Movenet. So, I follow them and see what initiatives they have, where they have open stores and things like that (Daniela, Zocamiñoca).

I don't buy many clothes, but I want the ones I buy to be durable (Rocío, Semente)

I used to buy more. Something I do is to buy when I need and only what I need (Helena, Zocamiñoca).

Concerning energy use, I live in a rented flat, and we have electric heating and what we are doing is not putting it on, we are wrapping ourselves up more. I don't get cold in my house either, I don't live badly either and if I were very cold on a specific day, we put it on, we bundled up. Let's see, I wrap myself a lot, I wrap myself a lot, but I prefer to keep warm, to be comfortable but warm than not to use so much electricity heating home (Helena, Zocamiñoca).

I have a garden. Besides joining the consumer group, I have a small garden, I moved from the city for that. For having a garden and for being able to compost my waste. Because it seemed like a tremendous incoherence to throw away the food scraps. I couldn't live with it. It caused me tremendous frustration. Now I have the compost bin next to the garden, and I feel super happy to close the circle (Rocío, Semente).

Engagement in Third Sector organizations and cooperatives

I also got to know other consumer models. Fiare or different economic models I knew thanks to Panxea. It is clearly a key point of information (Gabriela, Panxea).

I am committed to decreasing and reducing total consumption, consuming the minimum and being as self-sufficient as possible in everything. (...) I am not resigned to the model we have. I always try to find alternatives. In consumption, in the generation of waste, in mobility. At the energy level, I joined SOM Energía, an energy cooperative, because I am committed to a different energy model. I don't want that terrible energy monopoly. I do not adapt to what there is, and I try to look forward (Rocío, Semente).

Inexistence of contextual spillover

4. General Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Capstick, S.; Khosla, R. ; Wang, S. ; van den Berg, N. ; Ivanova, D. ; Otto, I. M., ... Whitmarsh, L. Bridging the gap–the role of equitable low-carbon lifestyles. UNEP Emission Gap Report 2020, pp. 62-75. UNEP. https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/34432 1.

- IPCC. Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. Summary for Policymakers. 2018. World Meteorological Organization. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm/ (accessed on 25.10.2025).

- Whitmarsh, L.; Poortinga, W.; Capstick, S. (2021). Behaviour change to address climate change. Current Opinion in Psychology, 42: 76–81. [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P.; Whitmarsh, L.; Gatersleben, B.; O’Neill, S.; Hartley, S.; Burningham, K.; Sovacool, B.; Barr, S.; Anable, J. Placing people at the heart of climate action. PLOS Climate 2022, 1, e0000035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, P.; Jacobs, N.; Villa, V.; Thomas, J.; Bacon, M.H.; Vandelac, L.; Schlavoni, C. A Long Food Movement: Transforming Food Systems by 2045; IPESFOOD and ETC Group: 2021. Available online: https://www.ipes-food.org/_img/upload/files/LongFoodMovementEN.pdf (accessed on 25.10.2025).

- Sims, R.E. Energy-Smart" Food for People and Climate: Issue Paper; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2011; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i2454e/i2454e.pdf (accessed on 25.10.2025).

- Joyce, A.; Hallett, J.; Hannelly, T.; Carey, G. The impact of nutritional choices on global warming and policy implications: examining the link between dietary choices and greenhouse gas emissions. Energy and Emission Control Technologies 2014, 2, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrowicz, L.; Green, R.; Joy E. J. M.; Smith, P.; Haines, A. The Impacts of Dietary Change on Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Land Use, Water Use, and Health: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11(11): e0165797.

- Hampton, S., & Whitmarsh, L. (2023). Choices for climate action: A review of the multiple roles individuals play. One Earth, 6(9), 1157-1172. [CrossRef]

- Vita, G.; Ivanova, D.; Dumitru, A.; García-Mira, R.; Carrus, G.; Stadler, K.; Krause, K.; Wood, R.; Hertwich, E.G. Happier with less? Members of European environmental grassroots initiatives reconcile lower carbon footprints with higher life satisfaction and income increases. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 60, 101329. [CrossRef]

- Lema-Blanco, I.; García-Mira, R.; Muñoz-Cantero, J. M. Understanding Motivations for Individual and Collective Sustainable Food Consumption: A Case Study of the Galician Conscious and Responsible Consumption Network. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M.; Clark, M.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Wiebe, K.; Bodirsky, B.; Lassaletta, L.; de Vries, W.; … Willett, W. Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits. Nature 2018, 562, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbyshire, E. J. (2017). Flexitarian diets and health: a review of the evidence-based literature. Frontiers in nutrition, 3, 231850.

- Vermeir, I.; Weijters, B.; De Houwer, J.; Geuens, M.; Slabbinck, H.; Spruyt, A.; Van Kerckhove, A.; Van Lippevelde, W.; De Steur, H.; Verbeke, W. Corrigendum: Environmentally Sustainable Food Consumption: A Review and Research Agenda From a Goal-Directed Perspective. Front. Psych. 2020, 11, 160311–585387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.D.; Chen, A.K. Why aren’t we taking action? Psychological barriers to climate-positive food choices. Clim. Change 2017, 140, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable Food Consumption: Exploring the Consumer Attitude-Behavior Gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Devine-Wright, P.; Swim, J.; Bonnes, M.; Steg, L.; Whitmarsh, L.; Carrico, A. Expanding the role of psychology in addressing environmental challenges. American Psychologist 2016, 71(3), 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, S.; Kleinhückelkotten, S. Good intents, but low impacts: diverging importance of motivational and socioeconomic determinants explaining pro-environmental behavior, energy use, and carbon footprint. Environment and behavior 2018, 50(6), 626–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, I.; Sadat Shimul, A.; Liang, J.; Phau, I. Drivers and barriers toward reducing meat consumption. Appetite 2020, 149, 104636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, E. S.; Oberrauter, L.; Normann, A.; Norman, C.; Svensson, M.; Niimi, J.; Bergman, P. Identifying barriers to decreasing meat consumption and increasing acceptance of meat substitutes among Swedish consumers. Appetite 2021, 167(105643). [CrossRef]

- Bryła, P. Organic food consumption in Poland: Motives and barriers. Appetite 2016, 105, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, N.; Whitmarsh, L.; Capstick, S.; Hargreaves, T.; Poortinga, W.; Thomas, G.; ... Xenias, D. Climate-relevant behavioral spillover and the potential contribution of social practice theory. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 2017, 8(6), e481. [CrossRef]

- Galizzi, M. M.; Whitmarsh, L. How to measure behavioral spillovers: a methodological review and checklist. Frontiers in psychology 2019, 10, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Ölander, F. Human values and the emergence of a sustainable consumption pattern: A panel study. J. Eco. Psych. 2002, 23, 605–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Crompton, T. Simple and painless? The limitations of spillover in environmental campaigning. Journal of Consumer Policy 2009, 32(2), 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verfuerth, C.; Jones, C. R.; Gregory-Smith, D.; Oates, C. Understanding Contextual Spillover: Using Identity Process Theory as a Lens for Analyzing Behavioral Responses to a Workplace Dietary Choice Intervention. Frontiers in psychology 2019, 10, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhorst, J.; Klöckner, C. A.; Matthies, E. Saving electricity–For the money or the environment? Risks of limiting pro-environmental spillover when using monetary framing. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2015, 43(9), 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elf, P., Gatersleben, B., & Christie, I. (2019). Facilitating positive spillover effects: New insights from a mixed-methods approach exploring factors enabling people to live more sustainable lifestyles. Frontiers in psychology, 9, 2699. [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, F., Mehmood, A., MacCallum, D., & Leubolt, B. (2017). Social innovation as a trigger for transformations-the role of research. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Seyfang, G., & Smith, A. (2007). Grassroots innovations for sustainable development: Towards a new research and policy agenda. Environmental politics, 16(4), 584-603. [CrossRef]

- Haxeltine, A.; Avelino, F.; Wittmayer, J. M.; Kunze, I.; Longhurst, N.; Dumitru, A.; O’Riordan, T. Conceptualizing the role of social innovation in sustainability transformations. Social innovation and sustainable consumption. Research and action for societal transformation, 2017, pp.12-25. London: Routledge.

- Haxeltine A.; Jørgensen, M. S.; Pel, B.; Dumitru, A.; Avelino, F.; Bauler, T.; Lema-Blanco, I. (…)Wittmayer J. M. On the agency and dynamics of transformative social innovation. TRANSIT working paper #7. 2016. http://hdl.handle.net/2183/30105.

- Avelino, F.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Pel, B.; Weaver, P.; Dumitru, A.; Haxeltine, A.; Kemp, R.; Jørgensen, M.S.; Bauler, T.; Ruijsink, S; O’Riordan, T.Transformative Social Innovation and (Dis)Empowerment. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2019, 145, 195–206. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A. Beyond Food Provisioning: The Transformative Potential of Grassroots Innovation around Food. Agriculture 2017, 7(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, G.; Terragni, L.; Torjusen, H. The local in the global–creating ethical relations between producers and consumers. Anthropology of food 2007, (S2). [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, A.; Lema-Blanco, I.; Kunze, I.; García-Mira, R. The Slow Food Movement, A Case-Study Report; TRANSIT Project. 2016. http://hdl.handle.net/2183/30043.

- Seyfang, G. Ecological citizenship, and sustainable consumption: Examining local organic food networks. J. Rural. Stud. 2006, 22, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeurwaerdere, T.; De Schutter, O.; Hudon, M.; Mathijs, E.; Annaert, B.; Avermaete, T.; Joachain, H.; Vivero, J.L. The governance features of social enterprise and social network activities of collective food buying groups. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 140, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, A.; Lema-Blanco, I.; García-Mira, R.; Kunze, I.; Strasser, T.; Kemp, R. Social learning for transformative social innovation, TRANSIT deliverable 2.3. 2016. http://hdl.handle.net/2183/30112.

- Dumitru, A.; Lema-Blanco, I.; Kunze, I.; Kemp, R.; Wittmayer, J.; Haxeltine, A.; García-Mira, R.; Zuijderwijk, L.; Cozan, S. Social learning in social innovation initiatives: learning about systemic relations and strategies for transformative change. TRANSIT Brief:4. 2017. http://hdl.handle.net/2183/30073.

- Niesz, T.; Korora, A. M.; Walkuski, C. B.; Foot, R. E. Social movements and educational research: Toward a united field of scholarship. Teachers College Record 2018, 120(3), 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, S.; Middlemiss, L. The role of learning in sustainable communities of practice. Local environment 2015, 20(7), 796–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, J.; Wever, C. Learning alterity in the social economy: the case of the Local Organic Food Co-ops Network in Ontario, Canada. European Journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults 2017, 8(2), 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opitz, I.; Specht, K.; Piorr, A.; Siebert, R.; Zasada, I. Effects of consumer-producer interactions in alternative food networks on consumers’ learning about food and agriculture. Moravian Geographical Reports 2017, 25(3), 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunori, G.; Rossi, A.; Guidi, F. On the new social relations around and beyond food. Analysing consumers' role and action in Gruppi di Acquisto Solidale (Solidarity Purchasing Groups). Sociologia Ruralis 2012, 52(1), 1-30. [CrossRef]

- Russell, W. S., ; Zepeda, L. The adaptive consumer: shifting attitudes, behavior change and CSA membership renewal. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 2008, 136-148. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44491516.

- Yin, R. K. Case Study Research Design and Methods (5th ed.). 2014. SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2014.

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research, 5th ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2014.

- Kvale, S. Interviews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing. SAGE: London, UK, 1996.

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis; SAGE: London, UK, 2006.

- ATLAS. ti Scientific Software Development GmbH. 2022. Available online: https://atlasti.com (accessed on 25.10.2025).

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook; SAGE: New York, USA, 2018.

- Papaoikonomou, E.; Alarcón, A. Revisiting Consumer Empowerment: An Exploration of Ethical Consumption Communities. J. Macromarketing 2017, 37, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzell, D. (2010). Collective solutions to a global problem. The Psychologist, 23(11). https://openresearch.surrey.ac.uk/esploro/outputs/99512760902346 (accessed on 25.10.2025).

- Zoll, F.; Specht, K.; Opitz, I.; Siebert, R.; Piorr, A.; Zasada, I. Individual choice or collective action? Exploring consumer motives for participating in alternative food networks. International J. Cons. Stud. 2018, 42, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verfuerth, C.; Demski, C.; Capstick, S.; Whitmarsh, L.; & Poortinga, W. A people-centred approach is needed to meet net zero goals. Journal of the British Academy 2023, 11(S4), 97-124. [CrossRef]

- García Mira, R.; Dumitru, A. Green Lifestyles, Alternative Models and Upscaling Regional Sustainability; GLAMURS Final Report; Instituto Xoan Vicente Viqueira: A Coruña, Spain, 2017. Available online: http://www.people-environment-udc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/revista_glamurs_bj.pdf (accessed on 25.10.2025). Available online:.

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda." Journal of environmental psychology 2009, 29.3 (2009): 309-317. [CrossRef]

- Maio, G. R.; Verplanken, B.; Manstead, A. S.; Stroebe, W.; Abraham, C.; Sheeran, P.; Conner, M. Social psychological factors in lifestyle change and their relevance to policy. Social Issues and Policy Review 2007, 1(1), 99–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Donoso, C.; Sacks, G.; Vanderlee, L.; Hammond, D. ... & Cameron, A. J. Public support for healthy supermarket initiatives focused on product placement: a multi-country cross-sectional analysis of the 2018 International Food Policy Study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2021, 18(1), 78. [CrossRef]

- Rees, J. H.; Bamberg, S.; Jäger, A.; Victor, L.; Bergmeyer, M.; Friese, M. Breaking the Habit: On the Highly Habitualized Nature of Meat Consumption and Implementation Intentions as One Effective Way of Reducing It. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 2018, 40(3), 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hielkema, M. H.; Lund, T. B. Reducing meat consumption in meat-loving Denmark: Exploring willingness, behavior, barriers and drivers. Food Quality and Preference 2021, 93, 104257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll-Kleemann, S.; Schmidt, U.J. Reducing meat consumption in developed and transition countries to counter climate change and biodiversity loss: a review of influence factors. Reg Environ Change 2017, 17, 1261–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reipurth, M. F. S.; Hørby, L.; Gregersen, C. G.; Bonke, A.; Perez Cueto, F. J. A. Barriers and facilitators towards adopting a more plant-based diet in a sample of Danish consumers. Food Quality and Preference 2019, 73, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Organizational model | Name of the Initiative | Town (province) |

|---|---|---|

| NGO | A Cova da Terra | Lugo (Lugo) |

| Panxea | Santiago de Compostela (A Coruña) | |

| Amarante-Setem | Pontevedra y Santiago de Compostela | |

| Consumers´ cooperative | A Xoaniña | Ferrol (A Coruña) |

| Aldea SCG | Vigo (Pontevedra) | |

| Árbore | Vigo (Pontevedra) | |

| Eirado | Santiago de Compostela (A Coruña) | |

| Zocamiñoca | A Coruña (A Coruña) | |

| Non-profit organization | A Landra | O Carballiño (Ourense) |

| Loaira | Redondela (Pontevedra) | |

| Millo Miúdo | Oleiros (A Coruña) | |

| Semente | Ourense (Ourense) | |

| Consumers’ group | A Gradicela | Pontevedra (Pontevedra) |

| As Grelas | Ribadeo (Lugo) | |

| Agrelar | Allariz (Ourense |

| Typology | Name of the Initiative | Number of Participants |

| Cooperative with a store open to the public | Árbore (Vigo, Pontevedra) | 3 |

| Aldea (Vigo, Pontevedra) | 3 | |

| Panxea (Santiago de Compostela, A Coruña) | 1 | |

| Cooperative with a store (only for associates) | Zocamiñoca (A Coruña) | 11 |

| Non-profit organization | Semente (Ourense) | 2 |

| Millo Miúdo (Oleiros, Coruña) | 4 | |

| Consumers’ group | Agrelar (Allariz, Ourense) | 1 |

| A Gradicela (Pontevedra) | 1 |

| Category | Description | Groundedness and Frequency |

| Organic food | Organic locally produced food aligned with the principles of organic farming and sustainable livestock or seafood production | G: 38; F: 15 |

| Seasonal food | Consumption of fresh seasonal food (fresh vegetables, fruits and other groceries produced seasonally) | G:14; F:4 |

| Artisan and fair-trade products | Manufactured high-added value alimentary products or Fair-Trade goods (e.g., Coffee, tea, cocoa) | G:20; F: 12 |

| Socio-labor conditions | Organic products produced by enterprises and social economy initiatives that respect fair labor conditions and ethical criteria | G:14; F: 11 |

| "Price" | Price and accessibility | G:7; F: 2 |

| Category | Description | Groundedness and Frequency |

| CRCI- High frequency | The food-coop is the main place to purchase food and other goods (e.g., cleaning products) | G:15; F: 10 |

| Local markets | Food markets or neighborhood shops are complementary to the food-coop | G: 13; F: 7 |

| Other stores | It is necessary to go to other consumer spaces to be able to purchase food and other products. The ICCR does not fully meet the needs. | G: 10; F: 6 |

| CRCI- Low frequency | Purchase made at the CRCI is minority or exceptional, preference is shown for other consumer spaces like supermarkets | G:6; F:5 |

| Category | Description | Groundedness and Frequency |

| Cultural barriers | Cultural or social barriers such as, for example, the existence of a deep-rooted gastronomic culture that makes it difficult to adopt vegetarian or low-meat diets | G:19; F: 12 |

| Habits and routines | Changing eating habits is perceived as a challenge that requires a significant effort for people to chain well-stablish habits and routines | G:12; F:6 |

| Time pressure | Perception of a shortage of time to consume sustainable | G: 10; F:8 |

| Category | Description | Groundedness and Frequency |

| Cognitive learning |

Increasing knowledge on the functioning of the global food system and its social and environmental impact. Awareness of transformative discourses and practices in economy and alternative ways of production and consumption | G:81; F: 21 |

| Attitudinal learning |

Attitudinal change toward the adoption of low-carbon eating styles, reduction of meat intake or positive attitude toward vegetarian or vegan diets | G:46; F:15 |

| Behavioral learning |

New culinary skills, experimentation with plant-based products and foods, adaptation to seasonality and available fresh products | G:23; F:10 |

| Category | Description | Groundedness and Frequency |

| Green lifestyles | Adoption of new low-carbon behaviors aligned with green lifestyles and frugality, such as vegetarian diets, reduced energy consumption at home or sustainable mobility | G:29; F:12 |

| Cooperativism | Participation in organizations of the social and solidarity economy, such as energy cooperatives or ethical banking | G:17; F:9 |

| Political activism |

Involvement in new political participation movements | G:10; F:10 |

| Contextual spillover | Transference of sustainable consumption to workplaces | G: 11; F: 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).