1. Introduction

Hunger and health diseases are currently on the rise, worsened by recent crises associated to military conflicts and pandemics [

1]. Addressing these issues requires humanity to enhance the sustainability of diets and drive the transition towards a more sustainable food system ensuring food security and nutrition for both present and future generations [

2].

This condition can be fostered by locally produced foods, whose consumption has been increasingly advocated in recent years as a way to enhance social, economic and environmental sustainability [

3,

4,

5]. Indeed, local food (LF) choices are usually associated with sustainability-related advantages, such as supporting local economy, reduced energy consumption, environmental friendliness, low processing and scant use of preservative compounds, social capital and inclusivity improvements [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Recognizing these benefits has led to a rapid growth of LF demand over time [

10] as well as to an increased scientific interest from both scholars and academics.

Past research often focused on LF systems, policies and distribution providing large evidence about their environmental, economic and social implications [

11].

However, consumer behaviour and preferences related to LF consumption still require further attention, since the motivations behind consumer choices and the factors influencing their purchasing decisions are not fully understood [

12]. Notably, a critical examination of the existing literature reveals a lack of comprehensive studies that holistically analyze the factors influencing LF consumption from the consumer’s perspective.

Current research predominantly focused on isolated aspects, by identifying a number of both intrinsic motivations, including freshness, nutritional value, taste and healthiness of LF [

13,

14,

15,

16] and extrinsic motivations, such as environmental and social sustainability [

17], without providing an overall framework combining them to compare their predicting values. Nevertheless, a comprehensive approach considering multiple factors can help to understand the nuanced and multi-faceted nature of consumer motivations while supporting food producers, retailers and policy makers in designing effective strategies promoting LF consumption and the overall transition towards a more sustainable food system [

18].

Notably, combining extrinsic and intrinsic motivations into an inclusive framework is particularly valuable as intrinsic motivations should encourage a certain behaviour just due to a sense of obligation, such as satisfying social pressures invoking the use of LF for healthy purposes, while extrinsic factors should provide a more stable behavioural basis to explain long-term LF choices [

19,

20]. Therefore, their mutual consideration is promising to make LF consumption more persistent and predictable.

Based on this evidence, the present study investigates the drivers of consumer’s intention to purchase and consume LF, by focusing on both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations under the umbrella of self-determination theory (SDT) [

21], which has had an important impact in modern psychology and marketing research as it offers a robust framework for comparing the predicting value of different motivations inspiring a certain behaviour. The basic assumption of SDT is that individuals who are willing to reach a certain goal that is not set by themselves but results from a peer pressure or a sense of guilt (e.g., consuming LF as it is beneficial for personal health) may be more prone to being discouraged after negative experiences or failures and less persistent in reaching the desired outcome [

21]. Instead, people engaged in activities that reflect their own interests and values act mostly in a self-determined way and are more likely to achieve their goals [

21]. In the case of LF consumption, this leads to suppose that people could be intrinsically motivated to buy LF as they recognize its qualities and potential benefits for personal health. However, they may be less persistent in their behaviour in case of negative experiences, such as LF is not available or not consistent with own preferences. Meanwhile, their behaviour may be more unchanging if they are extrinsically motivated, recognizing that LF is not only tastier, healthier and more natural than non-local one, but also concurs to affirm their sustainable-oriented values, as LF supports the sustainability of food production and consumption markets.

In this study, extrinsic motivations are represented by individuals’ concern in food sustainability, i.e., the extent to which a person is engaged with sustainability issues when consuming food [

22], while intrinsic motivations are strictly related to LF’s attributes and benefits, personal knowledge and past experiences. Product-related elements have been commonly recognized as intrinsic motivations positively influencing LF choices [

23,

24]. Past experiences and knowledge can be also included among intrinsic motivations, since they generate signals that can be recalled to guide a certain behaviour (e.g., intention to buy and consume LF regularly) [

25]. Communication sources regarding LF are further considered in this study, since prior research commonly recognized that the more exposed consumers are to information dealing with a certain topic, such as pro-environmental actions [

26,

27], the more pronounced their engagement with the topic is. Hence, information on LF provided by different sources may be considered among the potential antecedents of consumers’ interest in LF and (consequently) buying intention.

Two research questions operationalize the purpose of this study:

RQ1) How do intrinsic and extrinsic motivations affect consumer intention to buy and consume LF?

RQ2) Standing from the SDT, can the influence of intrinsic motivations on behavioural intention towards LF be considered conditional on the presence of extrinsic motivations (i.e., food sustainability concern)?

The study applies a structural equation modelling (SEM) approach investigating the relationships between LF consumption and its potential antecedents, based on a questionnaire survey carried out on 931 young consumers, aged between 18 and 40 years. This population group represents an interesting target market, whose behaviour has been scarcely documented by the literature in the LF domain. Indeed, as LFs are often associated with healthy eating [

13,

16], past studies increasingly recommended their use by young people to prevent future diseases and to create an overall healthier lifestyle [

28]. Moreover, young consumers represent a suitable target market when speaking about sustainability, as they usually express high concern in environmental protection and social responsibility [

29,

30], so much that, nowadays, “selling products to young consumers might not be even possible without relying on green strategies, either in the production processes or in marketing them under sustainable principles” [

30] (p.140). Finally, young consumers are usually considered of high interest to marketers, given their buying and decision-making power and their prospective economic role in the society [

32]. Thus, exploring young consumers’ perception, attitudes and behaviour towards LF is a critical matter, which can support companies and retailers to target them and to properly satisfy their needs and overall desire to buy and consume locally.

The contribution of the study is manifold. Above all, it enables a better comprehension of the motivational system encouraging young people to LF consumption, on which the related literature is quite scarce, by proposing an integrated framework considering the influence of both intrinsic and extrinsic factors on behavioural intention towards LF and their mutual relationships. Moreover, it provides companies in the LF sector with valuable information to better adjust their offer to a relevant target (i.e., young consumers) and achieve an enduring preference supporting the current transition towards a more sustainable food system.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides a general overview of the literature on LF consumption and underlying motivations from which the main hypotheses are derived.

Section 3 presents the methodology, followed by the analysis of results (

Section 4) and their discussion (

Section 5). The concluding section highlights limitations and outlines directions for future research.

2. Literature Background

Local Local food (LF) can be categorized by three distinct proximity domains: geographical, relational, and value-based [

33]. While geographical proximity emphasizes short supply chains minimizing transportation distances, relational proximity focuses on direct producer-consumer relationships fostering community and trust, and value-based proximity includes shared values like environmental sustainability and local economic support. This definition is particularly helpful as it highlights the role of LF in strengthening community ties and upholding ethical standards, thus being crucial for analysing its impact on both food systems and sustainability, and consumer behaviour [

33].

Based on the above proximities, several factors have been identified as potential antecedents of LF consumption. These include environmental concerns, where consumers choose LF to reduce their carbon footprint and support sustainable practices [

34,

35]; the desire for fresher, higher-quality products, as local foods often reach the consumer more quickly after harvest [

35]; and the support for local economies, where purchasing LF helps to sustain local farmers and businesses [

36]. Health considerations, such as the perception that LF is less likely to contain harmful pesticides or additives, have been also included among the main drivers of LF choices [

15].

While these studies provide valuable insights, they tend to compartmentalize factors rather than considering the interrelationships and cumulative effects on consumers, thus limiting the understanding of consumer behaviour regarding LF choices.

An interesting way to address this gap is represented by the Self-Determination Theory (SDT), originally developed by Ryan and Deci [

21], suggesting that individuals are more likely to engage in behaviours that fulfil their intrinsic needs. SDT posits that human motivations are simultaneously driven by the need for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. In the context of LF consumption, this means that consumers may be motivated by the desire for autonomy in making food choices that align with their personal values and beliefs, such as environmental sustainability and supporting local economies [

37]. The sense of competence achieved by selecting high-quality, healthy, and fresh LFs can further enhance consumer satisfaction and reinforce these purchasing behaviours [

35]. Additionally, the need for relatedness is also significant, as purchasing LF often involves direct interactions with producers, thus fostering a sense of community and trust [

9,

38].

Integrating SDT into the LF consumption domain can offer a robust explanatory framework that accounts for a range of intrinsic motivations, besides the extrinsic ones. This approach enables the comparison of different motivational factors within a single model, thus addressing the fragmentation in the existing literature. Moreover, it supports researchers and companies to better identify the most effective ways to promote LF choices, while aligning with broader sustainability goals.

2.1. Hypotheses Development

In this study, the behavioural intention to purchase and consume LF serves as the dependent variable, rooted in the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) which posits that intention is a critical antecedent of actual behaviour [

39]. Understanding the factors influencing behavioural intention within the LF context is crucial for promoting more sustainable consumption practices among the young consumers.

2.1.1. Intrinsic Motivations

One significant area of research focuses on the attributes and benefits of LF. Research indicates that attributes such as perceived freshness, quality, health benefits, and environmental sustainability are main motivators influencing the preferences and intentions of younger demographics towards LF [

35]. For instance, Pelletier et al. [

40] underscored that young consumers are increasingly drawn to LF due to its perceived healthfulness and freshness, which align with their preferences for high dietary quality and environmentally responsible food choices. Similarly, Beke et al. [

41] observed that high quality, distinctiveness, and excellent taste are primary drivers for purchasing local food, along with the opportunity to acquire unique products that are not found in large retail stores or other outlets. Notably, they emphasized that product attributes hold greater importance compared to price, availability, and purchasing convenience.

These attributes not only enhance the appeal of LF products but also resonate deeply with the values and concerns of younger generations, who prioritize transparency in food production and sustainability [

42]. This aligns with broader societal shifts towards more conscientious consumption patterns among young adults, influenced by their environmental consciousness and desire to support local economies [

43,

44].

In addition to perceived attributes, individual knowledge about LF has been identified as a key-determinant of behavioural intention [

15]. In the context of SDT, individual knowledge is considered as a part of intrinsic motivations, as acquiring knowledge often fulfils the innate psychological needs of competence, autonomy, and relatedness, which are central to intrinsic motivation [

21]. Consumers who are well-informed about the benefits of LF are more likely to express stronger intentions to purchase and consume these foods [

35]. Indeed, knowledge empowers consumers to make informed decisions consistent with their values and concerns, thereby influencing their intention to support local producers and sustainable food systems. Sirieix et al. [

45] emphasized the importance of knowledge highlighting how consumers need to know about the advantages of LF production and believe in its relevance before they develop an intention to purchase it.

Recent research highlights that well-informed youth regarding the benefits of LF show heightened intentionality towards embracing sustainable dietary behaviours [

46,

47]. This phenomenon is also supported by behavioural theories such as Social Cognitive Theory [

48], which posits that knowledge acquisition and educational attainment enhance self-regulatory capacities and sustainable behaviour adoption. Beyond mere awareness of personal benefits, knowledge encompasses a broader understanding of the environmental and societal implications of dietary choices [

34]. Therefore, informed youth are more inclined to make conscientious dietary decisions aligning with their values of sustainability and supporting for local producers. That is, improved knowledge on LF’s benefits and attributes may encourage individuals to consider not only their immediate well-being but also the well-being of future generations and the ecosystems they inhabit.

Satisfaction derived from previous experiences with LF consumption emerged as a further determinant of behavioural intention among young consumers. It represents a further component of intrinsic motivation, supported by the SDT framework, since satisfaction derived from consuming LF often stems from fulfilling intrinsic needs such as a sense of community, personal well-being, and environmental stewardship. For instance, Zepeda and Deal [

15] found that consumers of LF experience significant satisfaction from the perceived quality and health benefits of local products, which are seen as fresher and more trustworthy. This satisfaction aligns with the intrinsic need for competence in making healthy choices, autonomy in making independent choices that reflect personal values, and relatedness in feeling connected to the community and supporting local farmers. Prior research found that positive past experiences, encompassing satisfaction with taste, freshness, and overall quality of LFs, decisively augment the likelihood of continued engagement with them [

49,

50]. This is probably because food choices naturally involve an emotional attachment (King et al., 2008). For instance, in the context of organic food among Generation Z, Bhutto et al. [

51] demonstrated that customer satisfaction with previous experiences strongly influences their intention to repurchase, emphasizing the importance of ensuring high-quality LF to foster repeat business. These findings suggest that satisfaction from past consumption experiences acts as a reinforcing mechanism, strengthening consumers’ commitment to LF and encouraging them to continue supporting local producers.

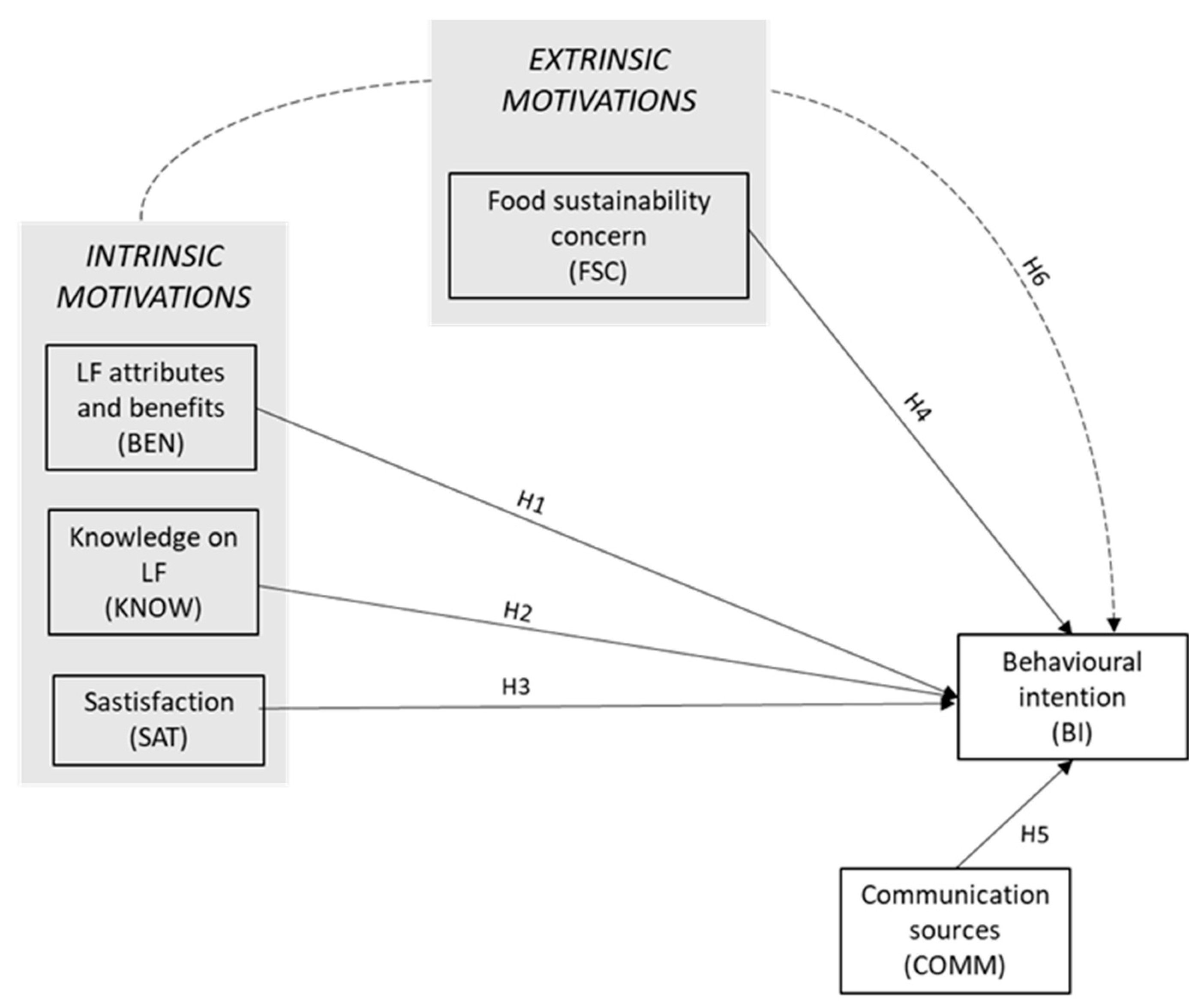

Drawing on these evidence, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1: Perceived attributes and benefits of LF positively influence young consumers’ behavioural intention.

H2: Individual knowledge about LF positively influences young consumers’ behavioural intention.

H3: Satisfaction from past consumption of LF positively influences young consumers’ behavioural intention.

2.1.2. Extrinsic Motivations

As for the extrinsic motivations driving the consumers’ intention to buy and consume locally, high attention has been devoted to the individual concern to sustainability encompassing a broad spectrum of issues, ranging from environmental impacts (e.g., carbon footprint, biodiversity conservation) to social and economic dimensions (e.g., fair trade, local economic development) [

52]. The consumers’ awareness and consideration of sustainability aspects in their food choices (i.e., food sustainability concern) can create a powerful motivation for consuming LF. Prior studies of Sunding [

53] and Thilmany et al. [

54] claimed that premium prices were more likely to be paid by consumers that were motivated to buy alternatively produced foods (e.g., organic food, local food) for altruistic reasons. Specifically, Hughner et al. [

55] found that consumers are willing to pay up to 30% more for organic products because they believe they help to preserve biodiversity and soil health. This willingness to pay a premium is driven by the desire to support farming practices that are less detrimental to the environment. Similarly, food sustainability concern has been linked to a greater likelihood of purchasing LFs, as consumers seek to support agricultural practices that are environmentally friendly and socially responsible [

56]. For instance, consumers who are concerned about food sustainability may prefer local products because they support local farmers [

57], reduce food miles and overall carbon footprint [

54], and often involve less packaging [

58].

Hence, our fourth hypothesis emerge as follows in relation to LF consumption by the young consumers:

H4. Food sustainability concern positively influences young consumers’ behavioural intention towards LF.

2.1.3. External Factors: Communication Sources

Communication sources play a crucial role in shaping consumer behaviours according to various behavioural theories, such as the Theory of Planned Behavior, emphasizing the influence of external factors, including communication channels, in determining attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control, which collectively determine behavioural intentions [

39].

Communication channels like social media, traditional media, and interpersonal interactions exert substantial influence over how consumers perceive and intend to engage with LF purchases. A study by Jung et al. [

8] found that promotional events, posters, emails, samples of LFs, and especially social media can be used as effective ways to increase awareness of LF among college students. Similarly, in the case of interpersonal communication, Bianchi and Mortimer [

18], highlighted how recommendations from friends and family significantly enhance consumers’ perceived value and trust in LF products.

Understanding the impact of communication sources can help marketers, policymakers, and researchers effectively promote behaviours, such as LF consumption, by strategically leveraging communication strategies able to improve young consumers’ engagement with locally produced food, as a way for developing a more sustainable food system in the long-term. Hence, information cues have been considered in this study to investigate their predictive power when compared to other intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. The next hypothesis is thus formulated:

H5. Communication sources positively influence young consumers’ behavioural intention towards LF.

2.1.4. The Mediating Role of Extrinsic Motivations

As far, the research based on the SDT often suggested that extrinsic motivations are more important than intrinsic ones in orienting long-term and stable self-determined choices. Indeed, while intrinsic motivations are undoubtedly important for immediate engagement and satisfaction, the internalization of extrinsic motivations can play a pivotal role in ensuring sustained behaviour change [

21]. This process is particularly evident in the context of LF choices. Zepeda and Leviten-Reid [

57] found that consumers who began buying LF to support local farmers continued doing so as they internalized the value of their contributions to the community. A similar pattern has been observed with environmental motivations. A study by Brown and Miller [

36] demonstrated that consumers who were initially driven by environmental concerns to buy LF often continued this behaviour as they recognized the broader ecological benefits. These consumers initially supported local agriculture to reduce greenhouse gas emissions associated with long-distance food transportation. As they learned more about the environmental impact and the importance of sustainable practices, these extrinsic motivations became internalized, leading to a lasting preference for such foods. Another example is the participation in Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) programs. Initially, many consumers can join CSA programs to support local agriculture and receive fresh products. Over time, as they experience the benefits of direct farmer support and community building, these extrinsic motivations become internalized, resulting in a stable long-term commitment in CSA programs [

59].

More recently, Annunziata et al. [

22] (p. 92), by combining organic and LF consumption with consumers’ adherence to the Mediterranean diet, considered them “to be part of an overall orientation to sustainability, rather than being just seen as a healthier and more sustainable diet”.

These findings illustrate how extrinsic motivations can evolve into intrinsic values, producing sustained consumer behaviour. On these bases, one can suppose that FSC mediates the relationship between BI and other intrinsic motivations, since BI could proportionally increase when consumers are concerned with food sustainability problems, regardless of their personal knowledge, satisfaction and perception of LF attributes and benefits, as proposed in the following hypothesis:

H6. FSC mediates the positive relationships between intrinsic motivations (i.e., LF attributes and benefits, knowledge on LF and satisfaction) and behavioural intention.

Figure 1 depicts the investigated framework with relative hypotheses.

3. Materials and Methods

Data for this study have been collected, from March to September 2023, by means of an online self-administered questionnaire on a sample population aged 18-35 years. Italy has been selected as research setting for a twofold reason. First, LFs from Italy represent a salient expression of authenticity and local culture, and have acquired an increasing appeal and popularity during the last decade [

24,

50] resulting in the highest number of LFs labelled with geographical indications in Europe [

50]. Second, prior research confirmed that in Italy, as in many developed countries [

12], people are highly involved with sustainable food consumption and related food choices, including buying and consuming locally [

22].

The questionnaire was developed and pre-tested with a small number of respondents (15) to ensure its clarity and comprehensibility. After being slightly modified, the final instrument consisted of three sections investigating (i) the overall respondents’ food consumption and purchasing habits, (ii) their perception, knowledge and attitudes towards LF, and (iii) their level of food sustainability concern. An additional section investigated the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample.

The questionnaire included a preliminary screening question ascertaining the respondents’ consumption of LF (i.e.,

When given the chance, how frequently would you consume local foods?), based on a five-point Likert scale. We considered only people consuming LF ‘occasionally/sometimes’, ‘almost every time’ or ‘every time’, by excluding ‘almost never’ and ‘never’ responses. This ensured that respondents were familiar with LFs properties and that their preference towards them was consistent. Accordingly, the original number of 1.080 collected questionnaire was reduced to 931 valid questionnaires for the analysis.

Table 1 provides a general overview of the sample profile.

3.1. Measures

The questionnaire items were derived from existing literature to ensure the highest content validity of the scales. Specifically, behavioural intention (BI) is the dependent variable, perceived attributes and benefits of LF (BEN), knowledge (KNOW), satisfaction (SAT), and food sustainability concern (FSC) are the independent ones. FSC is also investigated as the mediator, to specifically address RQ2 (i.e., Standing from the SDT, can the influence of intrinsic motivations on behavioural intention towards LF be considered conditional on the presence of extrinsic motivations (i.e., food sustainability concern?).

Items for measuring perceived attributes and benefits of local foods were adapted from Schönhart et al. [

60] analysing the most frequent expected effects of typical-local food systems on potential stakeholders. Additional items were included according to Roininen et al. [

61], exploring the consumers’ perception of LF, and the recent Barilla Food Center’s [

62] Report on global trends, which particularly underlines the opportunity to protect the environment, local culture and traditions among the main factors influencing the attention towards LF consumption.

Items concerning knowledge, satisfaction and behavioural intention towards LF have been drawn from Lee et al.’ [

63] study, based on prior research of Shepherd and Towler [

64] for knowledge, Oliver [

65] for satisfaction, and Zeithaml et al. [

66] for behavioural intention respectively.

Communication sources have been extracted from the IFIC Survey [

67] on Food and health, investigating the main trusted sources guiding food choices under a healthy perspective.

Finally, items for food sustainability concerns were taken, with few adaptations, from Annunziata et al. [

22], analysing the organic and LF consumption of Italian families. All items were measured on a 7-point Likert scale of agreement (1=strongly disagree; 7=strongly agree).

Appendix A provides full description of the variables with related references.

3.2. Data Processing

The data analysis followed a multi-step procedure, combining descriptive statistics with multivariate techniques. The former was useful to provide a preliminary overview of the respondents’ profile and food habits, based on frequencies, mean values and standard deviations. Multivariate techniques were applied to investigate the hypothesized relationships among variables. Specifically, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA), based on the maximum likelihood estimation, was performed to identify the key-factors associated to those antecedents of behavioural intention that are based on a relevant number of items, i.e., LF benefits (BEN), food sustainability concern (FSC), and communication sources (COMM). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity supported the appropriateness of such analysis [

68]. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the reliability and validity of the model and to investigate the multiple relationships among variables. Before running the multivariate analysis, the inter-items correlation of each construct was observed [

69]. It was not higher than 0.50, thus avoiding collinearity problems. Finally structural equation modelling (SEM) was applied to assess the hypothesized relationships among variables.

Data analysis was conducted through R 3.5.0 statistical software package.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Factor Analysis

Food Food habits of young respondents are characterized as follows. More than 89% of the sample buy food products from one to three times a week and the average expenditure is between 30 and 100€, revealing their intention to minimize time and shopping efforts by reducing the weekly shopping in one or few expeditions. Respondents typically shop in their city of residence (mean: 3.25), preferring supermarkets (mean: 3.06) and local convenience stores (mean: 2.12), mainly due to their balance between convenience and product variety. Store selection is primarily driven by the search for convenience, encompassing economic factors (such as good prices and promotions), location (including store proximity, parking facilities, and hours of operation), product assortment (size and variety), and the high quality of fresh foods.

Respondents reported having a good knowledge of LFs (mean: 4.33) and expressed high satisfaction with their past consumption experiences (mean: 5.17). Additionally, they indicated a strong intention to purchase and consume these foods in the future (mean: 5.62).

Then, they were asked to identify which LF they had purchased in the past two weeks, selecting from up to nine different food categories. The highest mean values were observed for fruit and vegetables (mean: 4.58), olive oil (mean: 4.55), and eggs (mean: 4.39), aligning with the food categories most frequently bought directly from producers [

70].

Overall, respondents declared to be highly willing to pay for buying a food that is both locally produced and environmentally sustainable (mean: 5.51).

The exploratory factor analysis produced significant results for the investigated constructs (i.e., BEN, FSC and COMM), revealing that economic and environmental protection are the most representative benefits associated to LF, followed by safety and health-related ones. With respect to FSC, mean values higher than 0.5 reveal that respondents are usually highly concerned with sustainability issues related to food choices. However, results from the EFA revealed that environmental dimensions are prominent, followed by social and economic issues related to food sustainability and package-related ones. Finally, specialized and mass communication conveyed through daily press, TV and social networks, emerged as the most prominent communications sources informing on LF, followed by scientific studies and product or process certifications. Informal communication appears to be the less relevant informing source (

Table 2).

4.2. Factors Affecting Behavioural Intention Towards LF: The SEM Analysis

Before analyzing the multiple relationships among variables, the SEM method was used to assess the reliability, unidimensionality, and validity of the investigated model, based on the factor solutions that emerged from the EFA. Each construct’s reliability was evaluated by calculating Alpha values and Composite Reliability (CR). The ranges of both indices indicate an appropriate level of internal consistency [

71,

72]. All factor loadings exceeded the lower limit of 0.4, and inter-construct correlations generally fell between 0.20 and 0.70, suggesting that items measure the same underlying characteristic while maintaining unique variance [

71]. Both convergent and discriminant validity were confirmed, as the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct exceeded the threshold value of 0.50 and the square of its inter-construct correlation [

72], thereby supporting the overall validity of the model (

Table 3 and

Table 4).

Besides assessing the model validity, a multiple regression analysis allowed to verify whether and how the intrinsic and extrinsic motivations and communication sources impact on behavioural intention, based on the results of previous factor analysis.

The findings revealed statistically significant relationships between BI and the following variables: economic and environmental benefits (BEN1: β=0.356***), KNOW (β=0.234), SAT (β=1.502***), environmental-related concern (FSC1: β=0.381), and informal sources (COMM4: β=0.132). This provided response to our RQ1, investigating the way intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, as well as communications sources, influence the consumer intention to buy and consume LF. Specifically, H1, H4 and H5 have been partially confirmed, while H2 and H3 have been fully confirmed (

Table 5).

The coefficient of determination (R

2) values, assessing the variance in the endogenous variable explained by the exogenous ones and the overall model predictivity [

68], were between 0.58 and 0.88, suggesting an adequate model’s explanatory power (

Table 3).

Thereafter, to assess the second research question (RQ2) of this study, a second run of SEM was performed, by analysing the mediating role of FSC.

By following Hair et al. [

68], mediation occurs when (i) the dependent variable (i.e., BI) and the investigated mediator (i.e., FSC) are significantly related to the independent ones (i.e., BEN, KNOW, SAT) and (ii) the indirect effects between the dependent and independent variables (after having introduced the mediating variable) are significant. Accordingly, the mediation analysis was restricted to environmental-related concern (FSC1) as a mediator on the relationships between behavioural intention (BI) and economic and environmental benefits (BEN1), knowledge (KNOW), and satisfaction (SAT).

Table 6 shows the results. FSC1 was positively related to BEN1, KNOW and SAT, satisfying the first criterion of Hair et al. [

68]. On the other hand, the indirect effects were significant only for BEN1 and KNOW. Therefore, the mediating role of FSC1 on the relationship between SAT and BI was excluded. Assessing the mediation intensity by the Variance Accounted For (VAF) index [

68], it emerged that a partial mediation of FSC1 can be confirmed only for the relationship between BI and BEN1 (25%). That is, the perception of LFs benefits improves the intention to consume them especially when individuals are concerned with environmental-related issues. Hence, sustainability concern is critical for improving the overall influence of LF benefits on consumers buying intention.

5. Discussion and implications

The findings suggest that respondents’ behavioural intention towards LF is mainly affected by their perception of economic and environmental benefits (H1), which emerged also as the most important factor, in terms of proportional variance, from the factor analysis. Consumers recognize that LF production and consumption assure better respect for the territory of origin, the biodiversity, the animal welfare and the overall environment, and this represents a good reason for buying and consuming LF.

Both knowledge (H2) and satisfaction (H3) are positively related to behavioural intention, revealing that the more consumers are aware about LFs’ quality and benefits, the more they are willing to buy and consume them. Similarly, satisfactory past experiences with LF consumption act as a predictor of future behavioural intention.

Food sustainability concern (H4) related to environmental issues significantly impacts on behavioural intention meaning that the more consumers are concerned with environmental problems, the more they are inclined to eat locally produced food. Indeed, they also associate local food to several environmental benefits.

The role of external communication (H5) appears quite scant: despite the factorial structure suggested the importance of specialized and mass communication, the SEM analysis highlighted the significant impact of informal sources (i.e., communication conveyed by relatives and friends) on behavioural intention, thus stressing the role of social norms and influences on LF choices.

Further insights emerged from the investigation of the relationships between food sustainability concerns and the intrinsic factors influencing behavioural intention. Findings revealed that economic and environmental benefits associated to LF, personal knowledge and the use of informal communication sources are positively related to food sustainability concern, while satisfaction did not. That is, the more consumers perceive the environmental-related benefits of LF, are recommended to consume them by their relatives and friend, and are able to recognize and distinguish LFs from generic ones, the more they become sensitive to food sustainability issues. In turn, such involvement in environmental concern act as a potential mediator (H6) highlighting the important role of extrinsic motivations besides intrinsic ones.

Several implications can be drawn from the findings of this study.

From a theoretical perspective, the results contribute significantly to the existing literature on LF consumption by offering a comprehensive framework that integrates both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations for LF consumption, an approach that has been previously underexplored. Previous research, indeed, predominantly focused on isolated aspects, such as environmental benefits, economic impacts, and health advantages. For instance, studies by Feldmann and Hamm [

35] and Pearson et al. [

73] emphasized the environmental benefits of reduced food miles and the economic support of local producers. Other scholars emphasized the importance of intrinsic motivations that are strictly related to LF properties including freshness, nutritional value, taste and healthiness [

13,

14,

15,

16]. A significant attention was also put on psychological and cultural factors, such as health consciousness and ethical considerations [

74]. While these studies provided valuable insights, they tend to compartmentalize factors rather than considering their interrelationships and cumulative effects, thus limiting the understanding of their influence on consumer choices.

By applying Self-Determination Theory (SDT), this study elucidates how different motivational factors, of both intrinsic and extrinsic nature, interact to influence young consumers’ intentions to purchase and consume LF. This holistic approach provides a more nuanced understanding of consumer patterns, as it considers the complex interplay between several motivational dimensions [

12,

19].

Furthermore, this research underscores the mediating role of food sustainability concern (FSC) in enhancing the predictive power of intrinsic motivations on behavioural intentions. By demonstrating that FSC can partially mediate the relationship between perceived LF benefits and behavioural intention, the findings highlight the importance of sustainability considerations in driving consistent and long-term LF consumption. This result corroborates the basic assumption of Self-Determination Theory, suggesting that extrinsic motivations can reinforce and stabilize intrinsic motivations over time [

21]. Notably, it is particularly relevant as it aligns with broader sustainability goals and adds depth to our understanding of how extrinsic factors can reinforce intrinsic motivations [

22].

This holistic perspective not only contributes to academic knowledge but also aids policymakers and marketers in promoting LF more effectively.

Firstly, emphasizing the economic and environmental benefits of LF can effectively resonate with young consumers’ values and enhance their intention to purchase and consume these foods. Marketing strategies should therefore highlight how LF supports local economies, reduces carbon footprints, and promotes biodiversity [

6,

35]. For instance, companies can create campaigns that feature local farmers and their sustainable practices, showcasing the direct impact of consumer purchases on the community. An example could be a video series on social media that follows the journey of LF from farm to table, highlighting the environmental benefits and local economic support.

Moreover, enhancing consumer knowledge about LF can significantly boost their purchasing intentions. Companies can achieve this through educational campaigns that inform consumers about the health benefits, freshness, and superior quality of LF. Utilizing various communication channels, including social media, blogs, and in-store promotions, can help disseminate this information effectively [

15]. For example, grocery stores could host cooking demonstrations and tasting events featuring local chefs who prepare dishes using LF, coupled with informative sessions about the nutritional benefits and origins of the ingredients used. In addition, considering the impact of informal and personal communication on consumers’ intention to consume LF, companies can create community-based programs that facilitate informal communication and knowledge sharing about LF. For example, firms can organize neighborhood potluck events where participants bring dishes made with LF, providing opportunities for people to share recipes, cooking tips, and personal experiences with LF. These gatherings can strengthen community bonds and enhance collective knowledge about the benefits of LF. Another approach is to engage local influencers and community leaders who can act as ambassadors for LF. These individuals can share their positive experiences and knowledge about LF through social media, local events, and community meetings, thereby leveraging their influence to reach a broader audience. For instance, a well-respected local chef could host a series of cooking classes or workshops focusing on LF, which could be promoted through both online platforms and local community centers. Lastly, educational institutions can play a pivotal role in enhancing informal communication about LF. Schools and universities can integrate LF topics into their curricula and organize educational field trips to local farms. These activities can increase students’ knowledge and interest in LF, which they are likely to share with their families and peers, thus spreading awareness and appreciation for LF within their communities.

Other implications derive from the critical role of satisfaction in shaping future behaviours suggesting that ensuring high-quality products and positive consumer experiences should be a priority for LF producers and retailers. Providing consistent product quality, fostering direct interactions between consumers and producers, and offering taste tests or sample promotions can be critical to enhance consumer satisfaction and loyalty [

49]. For example, farmers’ markets could implement a “Meet the Farmer” day where consumers can directly interact with the producers, learn about their farming practices, and sample their produce. This can build trust and satisfaction, encouraging repeat purchases.

Finally, the finding that extrinsic motivations, i.e., food sustainability concern (FSC), act as a mediator for intrinsic motivations, while supporting the basic foundations of the SDT framework, implies that business efforts to foster intrinsic motivations can be more effective when coupled with strategies that enhance extrinsic motivations (e.g., promoting the environmental and social benefits of LF consumption). For instance, marketing campaigns can simultaneously highlight the superior taste and freshness of LF while also underscoring how purchasing LF supports local farmers and reduces environmental impact. This dual approach can lead to more persistent and consistent consumer behaviour, as individuals who initially choose LF for intrinsic reasons (e.g., health and taste) may develop a stronger, more stable commitment when they also recognize the broader extrinsic benefits. Therefore, businesses should design comprehensive marketing strategies that integrate both intrinsic and extrinsic appeals. For example, loyalty programs that reward customers for purchasing LF can further reinforce these motivations. Such programs could offer points not only for buying LF but also for participating in sustainability-related activities, such as attending workshops on reducing food waste or supporting local environmental initiatives.

6. Conclusions

This study advances the understanding of local food (LF) consumption among young consumers by integrating both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations within a comprehensive framework, guided by Self-Determination Theory (SDT). The findings highlight the significant roles of perceived LF benefits, consumer knowledge, satisfaction, and food sustainability concern (FSC) in shaping behavioral intentions. Furthermore, the mediating effect of FSC underscores the importance of combining intrinsic and extrinsic motivations to foster sustained consumer behavior.

However, this study is not without limitations. Firstly, the research relies on self-reported data, which may be subject to social desirability bias and inaccuracies in recall. Future research could address this limitation by incorporating observational or experimental methodologies to validate self-reported behaviors. Secondly, the study focuses on young consumers in Italy, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other age groups and cultural contexts. Future studies should explore LF consumption patterns across diverse demographics and geographic regions to enhance the applicability of the results. Moreover, while the study integrates various motivational factors, it does not extensively explore the potential interactions between these factors and other psychological constructs such as attitudes and subjective norms. Future research could examine these interactions to provide a more holistic understanding of the determinants of LF consumption. Lastly, the study does not consider external factors such as availability and accessibility of LF, which could significantly influence consumption behaviour. Investigating how these external factors interact with intrinsic and extrinsic motivations could offer more comprehensive insights for promoting LF consumption.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The entire research pSrocedure adhered to the Ethical Committee’s guidelines of Urbino University, aligned with European data security and protection standards.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Before starting the questionnaire, participants were informed of the research’s scope and their right to decline participation at any time.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Measures.

| Variables |

Id |

Items |

References |

| BEHAVIOURAL INTENTION (BI) |

BI1 |

I intend to keep eating more local food |

[63,66] |

| BI2 |

The likelihood that I would recommend local food to a friend is high |

| BI3 |

The probability that I will choose local food is high |

| LOCAL FOOD BENEFITS (BEN) |

LF1 |

Local food provides fresher and better tasting |

[60,61,62] |

| LF2 |

Local food provides better health and nutrition |

| LF3 |

Local food improves agricoltural production and economy in the region |

| LF4 |

Local food respects the environment |

| LF5 |

Local food fosters environmentally friendly production method |

| LF6 |

Local food improves the safety |

| LF7 |

Local food contributes to conserving local traditions |

| LF8 |

Local food contributes to conserving traditional agricoltural landscape |

| LF9 |

Local food fosters environmentally friendly production methods |

| LF10 |

Local foods is critical for conserving traditional production and techniques |

| LF11 |

Local foods is critical for conserving local culture |

KNOWLEDGE ON LOCAL FOOD

(KNOW) |

K1 |

I am knowledgeable about local foods |

[63,64,75] |

| K2 |

I have more knowledge of local foods than my friends |

| K3 |

I am confident in knowing which food is local. |

SATISFACTION ABOUT LOCAL FOOD

(SAT) |

S1 |

I am satisfied with local food |

[63,65] |

| S2 |

Considering all my experiences with foods, my local food choices are wise |

| S3 |

Overall, I am pleased with local food based on my experience |

FOOD SUSTAINABILITY CONCERN

(FSC) |

FSC1 |

It is packaged in an environmentally friendly way |

[22] |

| FSC2 |

It is produced without the use of pesticides |

| FSC3 |

It is produced in a way that respects biodiversity |

| FSC4 |

It is produced in an unspoilt environment |

| FSC5 |

It is obtained in an environmentally friendly way |

| FSC6 |

It is produced respecting animal welfare |

| FSC7 |

It is grown using sustainable agricoltural practices |

| FSC8 |

It is produced in respect of human rights |

| FSC9 |

It is sold at a fair price for the producer |

| FSC10 |

It is locally produced to support local farmers |

COMMUNICATION SOURCES

(COMM) |

C1 |

Conversation with relatives |

[67] |

| C2 |

Conversation with friends |

| C3 |

Process certifications |

| C4 |

Product certifications |

| C5 |

Scientific study on local food sustainability |

| C6 |

Scientific study on local food safety |

| C7 |

Article on a specialized Journal |

| C8 |

Article on daily press |

| C9 |

TV |

| C10 |

Social networks |

| C11 |

Government and institutional communication |

References

- McLaren, S.; Berardy, A.; Henderson, A.; Holden, N.; Huppertz, T.; Jolliet, O.; De Camillis, C.; Renouf, C.; Rugani, B. Integration of Environment and Nutrition in Life Cycle Assessment of Food Items: Opportunities and Challenges; Food & Agriculture Org., 2021; ISBN 978-92-5-135532-9.

- Food Losses and Waste in the Context of Sustainable Food Systems. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-I3901e.pdf (accessed on 01/08/2025).

- Cappelli, L.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Ruggieri, R.; Gorelova, I. Is Buying Local Food a Sustainable Practice? A Scoping Review of Consumers’ Preference for Local Food. Sustainability 2022, 14, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Stanton, J.; Qu, Y. Consumers’ Evolving Definition and Expectations for Local Foods. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1808–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, A.M.; de Moura, A.P.; Deliza, R.; Cunha, L.M. The Role of Local Seasonal Foods in Enhancing Sustainable Food Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review. Foods 2021, 10, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiroki, S.; Garnevska, E.; McLaren, S. Consumer Perceptions About Local Food in New Zealand, and the Role of Life Cycle-Based Environmental Sustainability. J Agric Env. Ethics 2016, 29, 479–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, H. Local Food Systems from a Sustainability Perspective: Experiences from Sweden. Int. J. Sustain. Soc. 2009, 1, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.E.; Shin, Y.H.; Dougherty, R. A Multi Theory–Based Investigation of College Students’ Underlying Beliefs About Local Food Consumption. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 52, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.T.; Aknin, L.B.; Axsen, J.; Shwom, R.L. Unpacking the Relationships Between Pro-Environmental Behavior, Life Satisfaction, and Perceived Ecological Threat. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 143, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentsen, K.; Pedersen, P.E. Consumers in Local Food Markets: From Adoption to Market Co-Creation? Br. Food J. 2020, 123, 1083–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enthoven, L.; Van den Broeck, G. Local Food Systems: Reviewing Two Decades of Research. Agric. Syst. 2021, 193, 103226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable Food Consumption among Young Adults in Belgium: Theory of Planned Behaviour and the Role of Confidence and Values. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 64, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, J.; Arroyo, P.; Carrete, L. Conceptualizing Healthy Food: How Consumer’s Values Influence the Perceived Healthiness of a Food Product. JFNR 2019, 7, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trobe, H.L. Farmers’ Markets: Consuming Local Rural Produce. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2001, 25, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, L.; Deal, D. Organic and Local Food Consumer Behaviour: Alphabet Theory. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagevos, H.; Ophem, J. van Food Consumption Value: Developing a Consumer-Centred Concept of Value in the Field of Food. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 1473–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bravo, P.; Chambers, E.; Noguera-Artiaga, L.; López-Lluch, D.; Chambers, E.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A.; Sendra, E. Consumers’ Attitude towards the Sustainability of Different Food Categories. Foods 2020, 9, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.; Mortimer, G. Drivers of Local Food Consumption: A Comparative Study. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 2282–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahelices-Pinto, C.; Lanero-Carrizo, A.; Vázquez-Burguete, J.L. Self-Determination, Clean Conscience, or Social Pressure? Underlying Motivations for Organic Food Consumption among Young Millennials. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimbo, F.; Russo, C.; Di Fonzo, A.; Nardone, G. Consumers’ Environmental Responsibility and Their Purchase of Local Food: Evidence from a Large-Scale Survey. Br. Food J. 2020, 123, 1853–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Overview of Self-Determination Theory: An Organismic-Dialectical Perspective. In Handbook of self-determination research; University of Rochester Press: Rochester, NY, US, 2002; pp. 3–33. ISBN 978-1-58046-108-5. [Google Scholar]

- Annunziata, A.; Agovino, M.; Mariani, A. Sustainability of Italian Families’ Food Practices: Mediterranean Diet Adherence Combined with Organic and Local Food Consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megicks, P.; Memery, J.; Angell, R.J. Understanding Local Food Shopping: Unpacking the Ethical Dimension. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 264–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memery, J.; Angell, R.; Megicks, P.; Lindgreen, A. Unpicking Motives to Purchase Locally-Produced Food: Analysis of Direct and Moderation Effects. Eur. J. Mark. 2015, 49, 1207–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassarre, G. What Are Intrinsic Motivations? A Biological Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Development and Learning (ICDL); August 2011; Vol. 2, pp. 1–8.

- Grønhøj, A.; Thøgersen, J. Like Father, like Son? Intergenerational Transmission of Values, Attitudes, and Behaviours in the Environmental Domain. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Kaiser, F.G. Ecological Behavior across the Lifespan: Why Environmentalism Increases as People Grow Older. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, L.K.; Sabounchi, N.S.; Kemner, A.L.; Hovmand, P. Systems Thinking in 49 Communities Related to Healthy Eating, Active Living, and Childhood Obesity. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2015, 21, S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabija, D.-C.; Bejan, B.M.; Pușcaș, C. A Qualitative Approach to the Sustainable Orientation of Generation Z in Retail: The Case of Romania. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, T.M.; Paunović, I.; Milovanović, M.; Lozović, N.; Đurović, M. Examining Generation Z’s Attitudes, Behavior and Awareness Regarding Eco-Products: A Bayesian Approach to Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabija, D.-C.; Bejan, B.M.; Dinu, V. HOW SUSTAINABILITY ORIENTED IS GENERATION Z IN RETAIL? A LITERATURE REVIEW. | EBSCOhost. Available online: https://openurl.ebsco.com/contentitem/gcd:136924269?sid=ebsco:plink:crawler&id=ebsco:gcd:136924269 (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Franc-Dąbrowska, J.; Ozimek, I.; Pomianek, I.; Rakowska, J. Young Consumers’ Perception of Food Safety and Their Trust in Official Food Control Agencies. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 2693–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, S.N. Defining Local Food: Constructing a New Taxonomy—Three Domains of Proximity. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B — Soil Plant Sci. 2013, 63, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P. Adolescents’ Perceptions of Sustainable Diets: Myths, Realities, and School-Based Interventions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, C.; Hamm, U. Consumers’ Perceptions and Preferences for Local Food: A Review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 40, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Miller, S. The Impacts of Local Markets: A Review of Research on Farmers Markets and Community Supported Agriculture (CSA). Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2008, 90, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, L.G.; Sharp, E. Persuasive Communication and Proenvironmental Behaviours: How Message Tailoring and Message Framing Can Improve the Integration of Behaviours through Self-Determined Motivation. Can. Psychol. / Psychol. Can. 2008, 49, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkmann, J.; Welle, T.; Solecki, W.; Lwasa, S.; Garschagen, M. Boost Resilience of Small and Mid-Sized Cities. Nature 2016, 537, 605–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, J.E.; Laska, M.N.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Story, M. Positive Attitudes toward Organic, Local, and Sustainable Foods Are Associated with Higher Dietary Quality among Young Adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beke, J.; Balázsné Lendvai, M.; Kovács, I. Young Consumers’ Product Perception and Consumer Motivation Towards Buying Local Products.; 2021; pp. 85–92.

- Kowalska, A.; Ratajczyk, M.; Manning, L.; Bieniek, M.; Mącik, R. “Young and Green” a Study of Consumers’ Perceptions and Reported Purchasing Behaviour towards Organic Food in Poland and the United Kingdom. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farace, B.; Apicella, A.; Tarabella, A. The Sustainability in Alcohol Consumption: The “Drink Responsibly” Frontier. Br. Food J. 2019, 122, 1593–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyrwa, J.; Barska, A.; Jędrzejczak-Gas, J.; Kononowicz, K. Sustainable Consumption in the Behavior of Young Consumers. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 12, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirieix, L.; Delanchy, M.; Remaud, H.; Zepeda, L.; Gurviez, P. Consumers’ Perceptions of Individual and Combined Sustainable Food Labels: A UK Pilot Investigation. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irazusta-Garmendia, A.; Orpí, E.; Bach-Faig, A.; González Svatetz, C.A. Food Sustainability Knowledge, Attitudes, and Dietary Habits among Students and Professionals of the Health Sciences. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronto, R.; Saberi, G.; Carins, J.; Papier, K.; Fox, E. Exploring Young Australians’ Understanding of Sustainable and Healthy Diets: A Qualitative Study. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 2957–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, I.A.; Gutsche, S. Consumer Motivations for Mainstream “Ethical” Consumption. Eur. J. Mark. 2016, 50, 1326–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savelli, E.; Bravi, L.; Murmura, F.; Pencarelli, T. Understanding the Consumption of Traditional-Local Foods through the Experience Perspective : The Case of the Truffle. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 1261–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, M.Y.; Khan, M.A.; Sun, C.; Hashim, S.; Khan, H.T. Factors Affecting Repurchase Intention of Organic Food among Generation Z (Evidence from Developing Economy). PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0281527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollani, L.; Bonadonna, A.; Peira, G. The Millennials’ Concept of Sustainability in the Food Sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunding, D.L. The Role for Government in Differentiated Product Markets: Looking to Economic Theory. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2003, 85, 720–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilmany, D.; Bond, C.A.; Bond, J.K. Going Local: Exploring Consumer Behavior and Motivations for Direct Food Purchases. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2008, 90, 1303–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughner, R.S.; McDonagh, P.; Prothero, A.; Shultz II, C.J.; Stanton, J. Who Are Organic Food Consumers? A Compilation and Review of Why People Purchase Organic Food. J. Consum. Behav. 2007, 6, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Zielke, S. Can’t Buy Me Green? A Review of Consumer Perceptions of and Behavior Toward the Price of Organic Food. J. Consum. Aff. 2017, 51, 211–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, L.; Leviten-Reid, C. Consumers’ Views on Local Food. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2004, 35, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, C.; Rhein, S.; Sträter, K.F. Consumers’ Sustainability-Related Perception of and Willingness-to-Pay for Food Packaging Alternatives. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 181, 106219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, J.; Eisenhauer, B. Motivations for Participating in Community-Supported Agriculture and Their Relationship with Community Attachment and Social Capital. J. Rural Soc. Sci. 2008, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Schönhart, M.; Penker, M.; Schmid, E. Sustainable Local Food Production and Consumption: Challenges for Implementation and Research. Outlook Agric 2009, 38, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roininen, K.; Arvola, A.; Lähteenmäki, L. Exploring Consumers’ Perceptions of Local Food with Two Different Qualitative Techniques: Laddering and Word Association. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- One Health: Un nuovo approccio al cibo. Available online: http://sprecoalimentare.anci.it/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/one-health-un-nuovo-approccio-al-cibo-BCFN.pdf (accessed on 01/08/2025).

- Lee, S.-M.; Jin, N. (Paul); Kim, H.-S. The Effect of Healthy Food Knowledge on Perceived Healthy Foods’ Value, Degree of Satisfaction, and Behavioral Intention: The Moderating Effect of Gender. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 19, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, R.; Towler, G. Nutrition Knowledge, Attitudes and Fat Intake: Application of the Theory of Reasoned Action. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 1992, 5, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. A Cognitive Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction Decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The Behavioral Consequences of Service Quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2017 Food and Health Survey. Available online: https://ozscientific.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2017-Food-and-Health-Survey-Final-Report.pdf (accessed on 01/08/2025).

- Hair, J.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM): An Emerging Tool in Business Research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, N.R.; Smith, H. Applied Regression Analysis; John Wiley & Sons, 1998; ISBN 978-0-471-17082-2.

- Giampietri, E.; Koemle, D.B.A.; Yu, X.; Finco, A. Consumers’ Sense of Farmers’ Markets: Tasting Sustainability or Just Purchasing Food? Sustainability 2016, 8, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. An Overview of Psychological Measurement. In Clinical Diagnosis of Mental Disorders: A Handbook; Wolman, B.B., Ed.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1978; pp. 97–146. ISBN 978-1-4684-2490-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, D.; Henryks, J.; Trott, A.; Jones, P.; Parker, G.; Dumaresq, D.; Dyball, R. Local Food: Understanding Consumer Motivations in Innovative Retail Formats. Br. Food J. 2011, 113, 886–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, D.; Memery, J.; De Silva Kanakaratne, M. The Mindful Consumer: Balancing Egoistic and Altruistic Motivations to Purchase Local Food. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 40, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, T.H.; Laverie, D.A.; Wilcox, J.F.; Duhan, D.F. Differential effects of experience, subjective knowledge, and objective knowledge on sources of information used in consumer wine purchasing. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2005, 29, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).