Submitted:

13 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

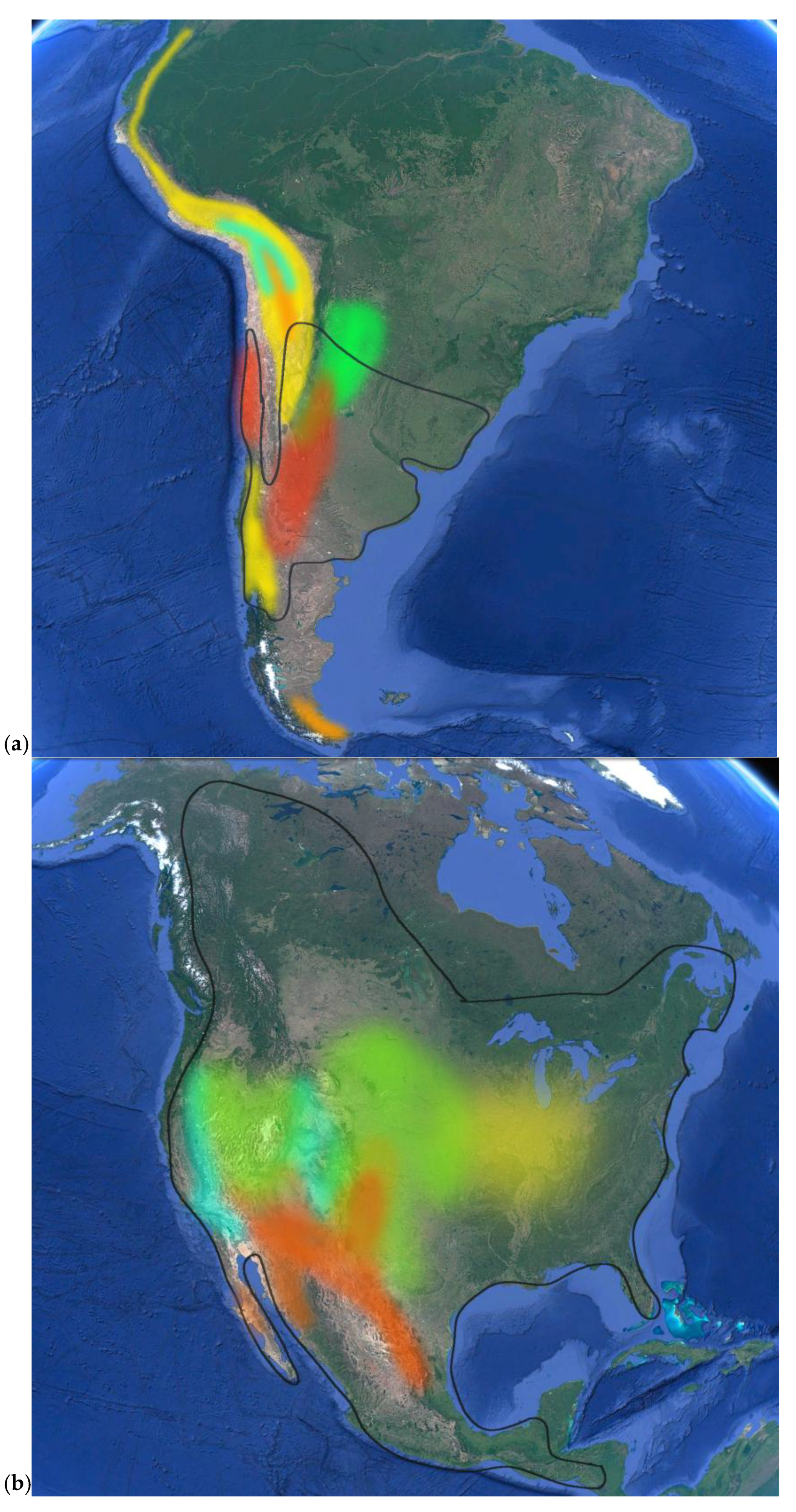

2. The Primary Gene Pool of C. quinoa

3. The Secondary Gene Pool of C. quinoa

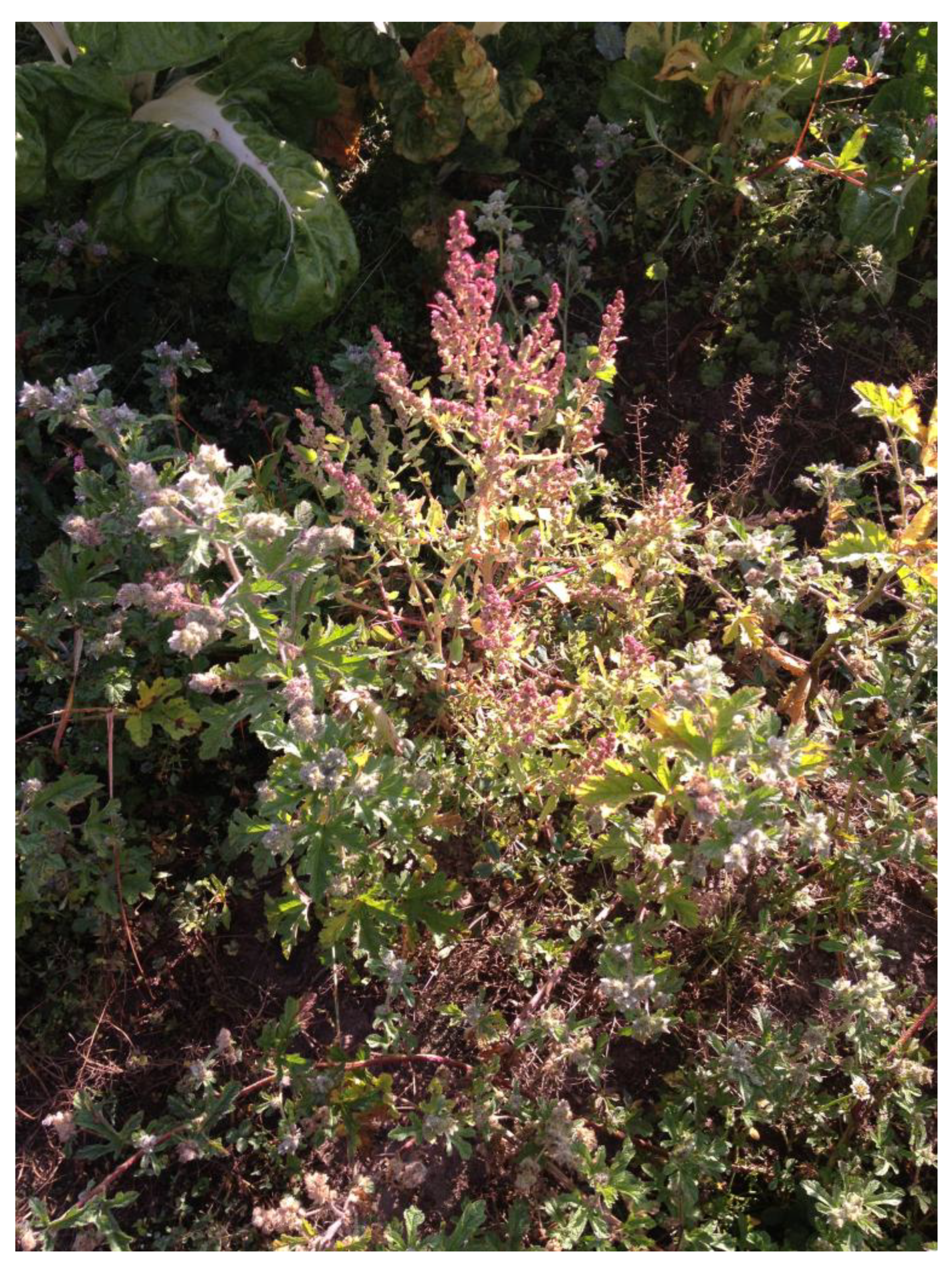

3.1. The Mesoamerican ATGC Gene Pool

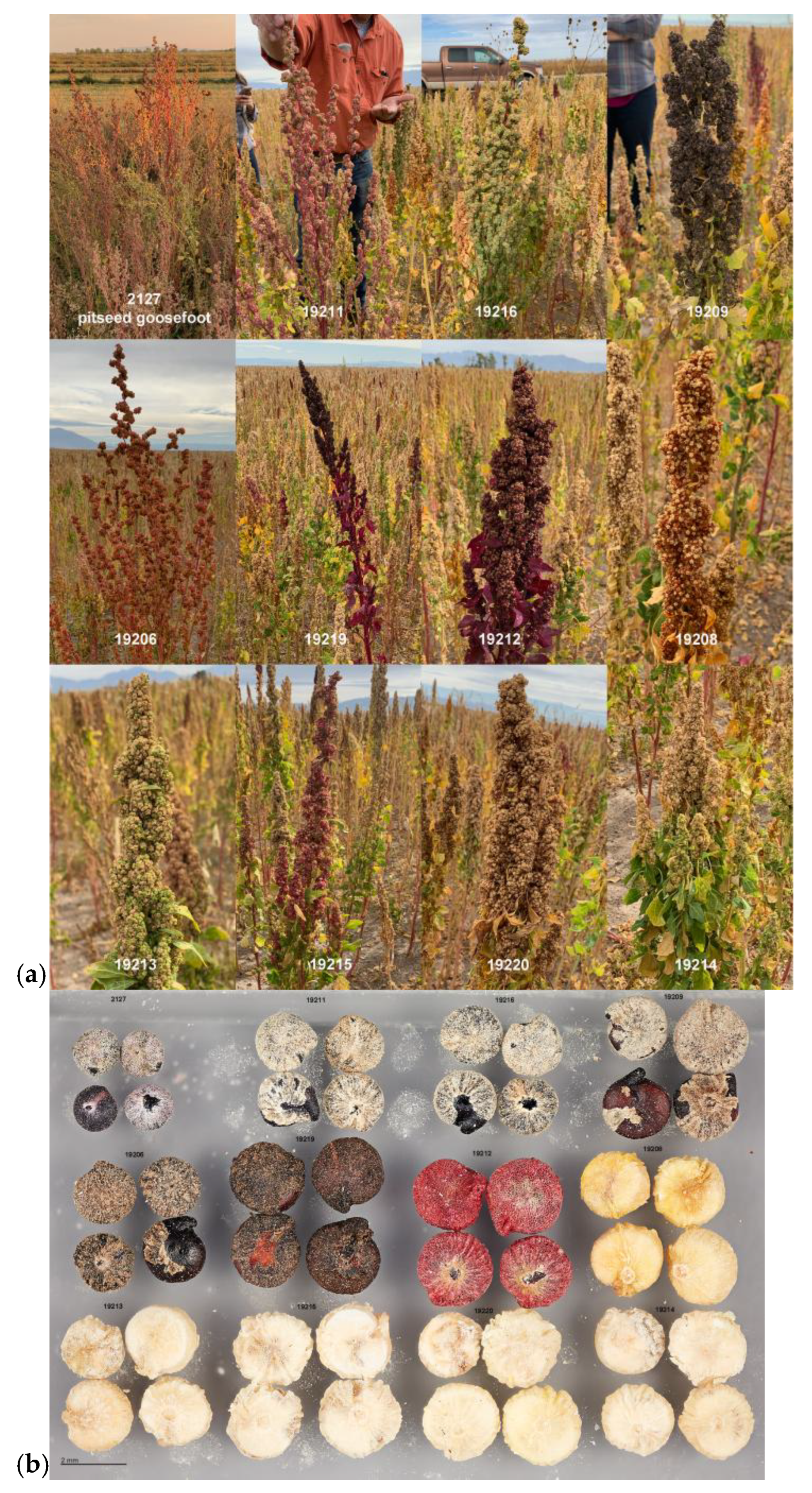

3.2. Crop-Weed Complexes in Colorado

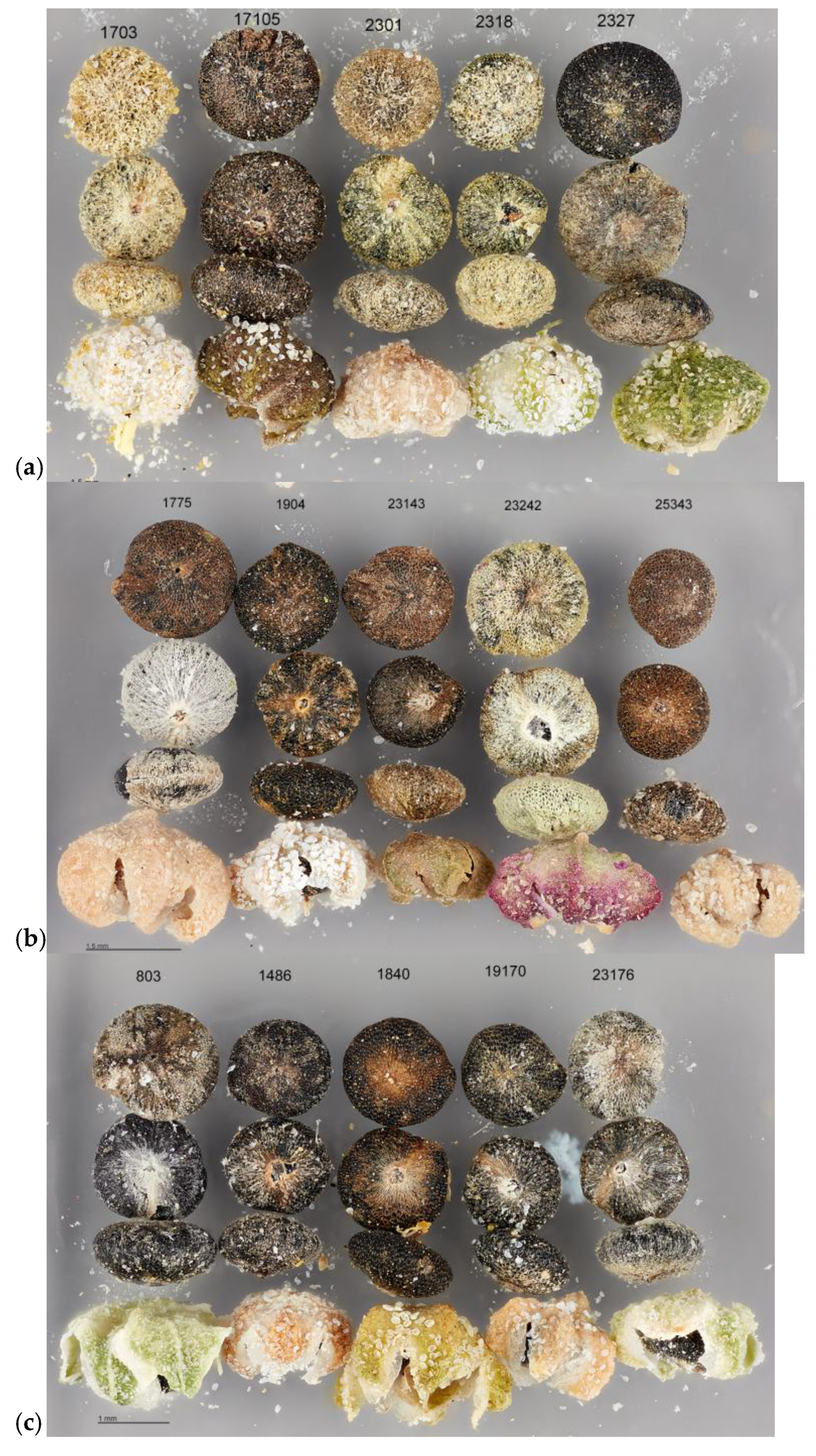

3.3. Quinoa Domestication Traits

3.4. Secondary Germplasm Collection and Characterization Looking into the Future

4. Tertiary Gene Pool of C. quinoa

4.1. The AA Diploids

4.2. The BB Diploids

4.3. Breeding value of AA and BB diploids

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATGC | Allotetraploid goosefoot complex |

| FISH | Fluorescence in situ hybridization |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association study |

| HIAN | C. hians taxonomic group |

| ITS | Internal transcribed sequence (rRNA) |

| LTR | Long-terminal repeat transposable element |

| MTA | Marker-trait association |

| NEOM | C. neomexicanum taxonomic group |

| PG | Pitseed goosefoot |

| QTL | Quantitative trait locus |

| SV | Structural variant |

| TMA | Trimethylamine |

| TMAO | Trimethylamine oxide |

References

- Sharbrough, J.; Conover, J.L.; Fernandes Gyorfy, M.; Grover, C.E.; Miller, E.R.; Wendel, J.F.; Sloan, D.B. Global Patterns of Subgenome Evolution in Organelle-Targeted Genes of Six Allotetraploid Angiosperms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2022, 39, msac074. [CrossRef]

- Soltis, P.S.; Soltis, D.E. The Role of Genetic and Genomic Attributes in the Success of Polyploids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000, 97, 7051–7057. [CrossRef]

- Panchy, N.; Lehti-Shiu, M.; Shiu, S.-H. Evolution of Gene Duplication in Plants. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 2294–2316. [CrossRef]

- Coughlan, J.M.; Han, S.; Stefanović, S.; Dickinson, T.A. Widespread Generalist Clones Are Associated with Range and Niche Expansion in Allopolyploids of Pacific Northwest Hawthorns (Crataegus L.). Mol. Ecol. 2017, 26, 5484–5499. [CrossRef]

- te Beest, M.; Le Roux, J.J.; Richardson, D.M.; Brysting, A.K.; Suda, J.; Kubešová, M.; Pyšek, P. The More the Better? The Role of Polyploidy in Facilitating Plant Invasions. Ann. Bot. 2012, 109, 19–45. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, A.G.; Moraga, R.; Tausen, M.; Gupta, V.; Bilton, T.P.; Campbell, M.A.; Ashby, R.; Nagy, I.; Khan, A.; Larking, A.; et al. Breaking Free: The Genomics of Allopolyploidy-Facilitated Niche Expansion in White Clover. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 1466–1487. [CrossRef]

- Schiavinato, M.; Bodrug-Schepers, A.; Dohm, J.C.; Himmelbauer, H. Subgenome Evolution in Allotetraploid Plants. Plant J. 2021, 106, 672–688. [CrossRef]

- Maughan, P.J.; Jarvis, D.E.; de la Cruz-Torres, E.; Jaggi, K.E.; Warner, H.C.; Marcheschi, A.K.; Bertero, H.D.; Gomez-Pando, L.; Fuentes, F.; Mayta-Anco, M.E.; et al. North American Pitseed Goosefoot (Chenopodium Berlandieri) Is a Genetic Resource to Improve Andean Quinoa (C. Quinoa). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12345. [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, D.E.; Ho, Y.S.; Lightfoot, D.J.; Schmöckel, S.M.; Li, B.; Borm, T.J.A.; Ohyanagi, H.; Mineta, K.; Michell, C.T.; Saber, N.; et al. The Genome of Chenopodium Quinoa. Nature 2017, 542, 307–312. [CrossRef]

- Patiranage, D.S.; Rey, E.; Emrani, N.; Wellman, G.; Schmid, K.; Schmöckel, S.M.; Tester, M.; Jung, C. Genome-Wide Association Study in Quinoa Reveals Selection Pattern Typical for Crops with a Short Breeding History. eLife 2022, 11, e66873. [CrossRef]

- Rey, E.; Maughan, P.J.; Maumus, F.; Lewis, D.; Wilson, L.; Fuller, J.; Schmöckel, S.M.; Jellen, E.N.; Tester, M.; Jarvis, D.E. A Chromosome-Scale Assembly of the Quinoa Genome Provides Insights into the Structure and Dynamics of Its Subgenomes. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 1263. [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.D.; Yarnell, R.A. Initial Formation of an Indigenous Crop Complex in Eastern North America at 3800 B.P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 6561–6566. [CrossRef]

- Kistler, L.; Shapiro, B. Ancient DNA Confirms a Local Origin of Domesticated Chenopod in Eastern North America. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2011, 38, 3549–3554. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, H.D. Quinua and Relatives (Chenopodium Sect.Chenopodium Subsect.Celluloid). Econ. Bot. 1990, 44, 92–110. [CrossRef]

- Young, L.A.; Maughan, P.J.; Jarvis, D.E.; Hunt, S.P.; Warner, H.C.; Durrant, K.K.; Kohlert, T.; Curti, R.N.; Bertero, D.; Filippi, G.A.; et al. A Chromosome-Scale Reference of Chenopodium Watsonii Helps Elucidate Relationships within the North American A-Genome Chenopodium Species and with Quinoa. Plant Genome 2023, 16, e20349. [CrossRef]

- Bazile, D. Global Trends in the Worldwide Expansion of Quinoa Cultivation. Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2023, 25, 13. [CrossRef]

- Khoury, C.K.; Carver, D.; Greene, S.L.; Williams, K.A.; Achicanoy, H.A.; Schori, M.; León, B.; Wiersema, J.H.; Frances, A. Crop Wild Relatives of the United States Require Urgent Conservation Action. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 33351–33357. [CrossRef]

- Fundación PROINPA; Bonifacio, A. Improvement of Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd.) and Qañawa (Chenopodium Pallidicaule Aellen) in the Context of Climate Change in the High Andes. Cienc. E Investig. Agrar. 2019, 46, 113–124. [CrossRef]

- Hodková, E.; Mandák, B. An Overlooked Hybrid between the Two Diploid Chenopodium Species in Central Europe Determined by Microsatellite and Morphological Analysis. Plant Syst. Evol. 2018, 304, 295–312. [CrossRef]

- Benet-Pierce, N.; Simpson, M.G. Chenopodium Littoreum (Chenopodiaceae), a New Goosefoot from Dunes of South-Central Coastal California. Madroño 2010, 57, 64–72. [CrossRef]

- Benet-Pierce, N.; Simpson, M.G. Taxonomic Recovery of the Species in the Chenopodium Neomexicanum (Chenopodiaceae) Complex and Description of Chenopodium Sonorense Sp. Nov.1. J. Torrey Bot. Soc. 2017, 144, 339–356. [CrossRef]

- Benet-Pierce, N.; Simpson, M.G. THE TAXONOMY OF CHENOPODIUM HIANS, C. INCOGNITUM, AND TEN NEW TAXA WITHIN THE NARROW-LEAVED CHENOPODIUM GROUP IN WESTERN NORTH AMERICA, WITH SPECIAL ATTENTION TO CALIFORNIA. Madroño 2019, 66, 56–75. [CrossRef]

- S.l, M.; B, M. Chenopodium Ucrainicum (Chenopodiaceae / Amaranthaceae Sensu APG), a New Diploid Species: A Morphological Description and Pictorial Guide. Ukr. Bot. J. 2020, 77, 237–248.

- Fuentes-Bazan, S.; Uotila, P.; Borsch, T. A Novel Phylogeny-Based Generic Classification for Chenopodium Sensu Lato, and a Tribal Rearrangement of Chenopodioideae (Chenopodiaceae). Willdenowia 2012, 42, 5–24. [CrossRef]

- Gandarillas, H. Razas de Quinua; Bull; Instituto Boliviano de Cultivos Andinos, División de Investigaciones Agrícolas, Ministerio de Agricultura: La Paz, Bolivia, 1968;

- Tapia, M.E. Origen, Distribución Geográfica y Sistemas de Producción de La Quinua. In; Proceedings of the Reunión Sobre Genética y Fitomejoramiento de la Quinua: Puno, Peru, 1980.

- Risi, J. C.; Galwey, N. W. The Chenopodium Grains of the Andes: Inca Crops for Modern Agriculture. In; Advances in Applied Biology; Academic Press, 1984; pp. 145–215.

- Quinua Biosystematics I: Domesticated Populations on JSTOR Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4255110?seq=1 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Mason, S.L.; Stevens, M.R.; Jellen, E.N.; Bonifacio, A.; Fairbanks, D.J.; Coleman, C.E.; McCarty, R.R.; Rasmussen, A.G.; Maughan, P.J. Development and Use of Microsatellite Markers for Germplasm Characterization in Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd.). Crop Sci. 2005, 45, 1618–1630. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, S.A.; Pratt, D.B.; Pratt, C.; Nelson, P.T.; Stevens, M.R.; Jellen, E.N.; Coleman, C.E.; Fairbanks, D.J.; Bonifacio, A.; Maughan, P.J. Assessment of Genetic Diversity in the USDA and CIP-FAO International Nursery Collections of Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd.) Using Microsatellite Markers [Abstract].

- Fuentes, F.F.; Martinez, E.A.; Hinrichsen, P.V.; Jellen, E.N.; Maughan, P.J. Assessment of Genetic Diversity Patterns in Chilean Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd.) Germplasm Using Multiplex Fluorescent Microsatellite Markers. Conserv. Genet. 2009, 10, 369–377. [CrossRef]

- Maughan, P.J.; Smith, S.M.; Rojas-Beltrán, J.A.; Elzinga, D.; Raney, J.A.; Jellen, E.N.; Bonifacio, A.; Udall, J.A.; Fairbanks, D.J. Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Identification, Characterization, and Linkage Mapping in Quinoa. Plant Genome 2012, 5. [CrossRef]

- Genetic Identity Based on Simple Sequence Repeat (SSR) Markers for Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd.) | International Journal of Agriculture and Natural Resources Available online: https://ojs.uc.cl/index.php/ijanr/article/view/28571 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Morillo, A.C.; Manjarres, E.H.; Reyes, W.L.; Morillo, Y. Research Article Molecular Characterization of Intrapopulation Genetic Diversity in Chenopodium Quinoa (Chenopodiaceae). Genet. Mol. Res. 2020, 19. [CrossRef]

- EL-Harty, E.H.; Ghazy, A.; Alateeq, T.K.; Al-Faifi, S.A.; Khan, M.A.; Afzal, M.; Alghamdi, S.S.; Migdadi, H.M. Morphological and Molecular Characterization of Quinoa Genotypes. Agriculture 2021, 11, 286. [CrossRef]

- Manjarres-Hernández, E.H.; Morillo-Coronado, A.C.; Morillo-Coronado, Y. Characterization of the Genetic Diversity of Chenopodium Quinoa from the Department of Boyacá-Colombia Using Microsatellite Markers. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 2025, 26. [CrossRef]

- Costa Tártara, S.M.; Manifesto, M.M.; Bramardi, S.J.; Bertero, H.D. Genetic Structure in Cultivated Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd.), a Reflection of Landscape Structure in Northwest Argentina. Conserv. Genet. 2012, 13, 1027–1038. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.; Quipildor, V.B.; Giamminola, E.M.; Bramardi, S.J.; Jarvis, D.; Maughan, J.; Xu, J.; Farooq, H.U.; Ortega-Baes, P.; Jellen, E.; et al. Climate Links Leaf Shape Variation and Functional Strategies in Quinoa’s Wild Ancestor. AoB PLANTS 2025, 17, plaf049. [CrossRef]

- Winkel, T.; Aguirre, M.G.; Arizio, C.M.; Aschero, C.A.; Babot, M. del P.; Benoit, L.; Burgarella, C.; Costa-Tártara, S.; Dubois, M.-P.; Gay, L.; et al. Discontinuities in Quinoa Biodiversity in the Dry Andes: An 18-Century Perspective Based on Allelic Genotyping. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0207519. [CrossRef]

- Diversity of Quinoa in a Biogeographical Island: A Review of Constraints and Potential from Arid to Temperate Regions of Chile | Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca Available online: https://www.notulaebotanicae.ro/index.php/nbha/article/view/9733 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Rey, E.; Abrouk, M.; Dufau, I.; Rodde, N.; Saber, N.; Cizkova, J.; Fiene, G.; Stanschewski, C.; Jarvis, D.E.; Jellen, E.N.; et al. Genome Assembly of a Diversity Panel of Chenopodium Quinoa. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 1366. [CrossRef]

- X Chromosome Inversions and Meiosis in Drosophila Melanogaster | PNAS Available online: https://www.pnas.org/doi/abs/10.1073/pnas.21.6.384 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Schaal, S.M.; Haller, B.C.; Lotterhos, K.E. Inversion Invasions: When the Genetic Basis of Local Adaptation Is Concentrated within Inversions in the Face of Gene Flow. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2022, 377, 20210200. [CrossRef]

- Aroni, J. C.; Aroni, G.; Quispe, R.; Bonifacio, A. Quinua Real: Catálogo; Fundación McKnight; Fundación PROINPA: La Paz, Bolivia, 2003;

- Apaza, V.; Cáceres, G.; Estrada, R.; Pinedo, R. Catalogue of Commercial Varieties of Quinoa in Peru; UN-FAO; INIA: Lima, Peru, 2015; p. 74;.

- Yadav, R.; Gore, P.G.; Gupta, V.; Saurabh; Siddique, K.H.M. Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd.)—a Smart Crop for Food and Nutritional Security. In Neglected and Underutilized Crops; Farooq, M., Siddique, K.H.M., Eds.; Academic Press, 2023; pp. 23–43 ISBN 978-0-323-90537-4.

- Quinoa Seeds Wholesale | Quinoa Quality Available online: https://www.quinoaquality.com (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Institute of Crop Science; Xiu-shi, Y.; Pei-you, Q.; Quinoa Committee of the Crop Science Society of China; Hui-min, G.; Gui-xing, R. Quinoa Industry Development in China. Cienc. E Investig. Agrar. 2019, 46, 208–219. [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Isla, F.; Apaza, J.-D.; Mujica Sanchez, A.; Blas Sevillano, R.; Haussmann, B.I.G.; Schmid, K. Enhancing Quinoa Cultivation in the Andean Highlands of Peru: A Breeding Strategy for Improved Yield and Early Maturity Adaptation to Climate Change Using Traditional Cultivars. Euphytica 2023, 219, 26. [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Isla, F.; Kienbaum, L.; Haussmann, B.I.G.; Schmid, K. A High-Throughput Phenotyping Pipeline for Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa) Panicles Using Image Analysis With Convolutional Neural Networks. Plant Breed. n/a. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Pando, L.R.; Barra, A.E. la Developing Genetic Variability of Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd.) with Gamma Radiation for Use in Breeding Programs. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 349–355. [CrossRef]

- Heddle, J.A.; Whissell, D.; Bodycote, D.J. Changes in Chromosome Structure Induced by Radiations: A Test of the Two Chief Hypotheses. Nature 1969, 221, 1158–1160. [CrossRef]

- Imamura, T.; Takagi, H.; Miyazato, A.; Ohki, S.; Mizukoshi, H.; Mori, M. Isolation and Characterization of the Betalain Biosynthesis Gene Involved in Hypocotyl Pigmentation of the Allotetraploid Chenopodium Quinoa. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 496, 280–286. [CrossRef]

- Mestanza, C.; Riegel, R.; Vásquez, S.C.; Veliz, D.; Cruz-Rosero, N.; Canchignia, H.; Silva, H. Discovery of Mutations in Chenopodium Quinoa Willd through EMS Mutagenesis and Mutation Screening Using Pre-Selection Phenotypic Data and next-Generation Sequencing. J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 156, 1196–1204. [CrossRef]

- Moog, M.W.; Trinh, M.D.L.; Nørrevang, A.F.; Bendtsen, A.K.; Wang, C.; Østerberg, J.T.; Shabala, S.; Hedrich, R.; Wendt, T.; Palmgren, M. The Epidermal Bladder Cell-Free Mutant of the Salt-Tolerant Quinoa Challenges Our Understanding of Halophyte Crop Salinity Tolerance. New Phytol. 2022, 236, 1409–1421. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, H.D. Quinua Biosystematics II: Free-Living Populations. Econ. Bot. 1988, 42, 478–494. [CrossRef]

- Mabry, M.E.; Rowan, T.N.; Pires, J.C.; Decker, J.E. Feralization: Confronting the Complexity of Domestication and Evolution. Trends Genet. 2021, 37, 302–305. [CrossRef]

- Ellstrand, N.C.; Heredia, S.M.; Leak-Garcia, J.A.; Heraty, J.M.; Burger, J.C.; Yao, L.; Nohzadeh-Malakshah, S.; Ridley, C.E. Crops Gone Wild: Evolution of Weeds and Invasives from Domesticated Ancestors. Evol. Appl. 2010, 3, 494–504. [CrossRef]

- Curti, R.N.; Rodriguez, J.; Ortega-Baes, P.; Bramardi, S.J.; Jellen, E.N.; Jarvis, D.E.; Maughan, P.J.; Tester, M.; Bertero, H.D. Leaf Shape of Quinoa’s Wild Ancestor Chenopodium Hircinum (Amaranthaceae) in a Geographic Context. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2025, boaf040. [CrossRef]

- Anton, A. M.; Zuloaga, F. O. Flora Argentina: Vascular Flora of the Argentine Republic. Dicotyledonae: Caryophyllales, Ericales, Gentianales. Chenopodium L.; Flora Argentina; IBODA, CONICET: San Isidro, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2022; Vol. 19;.

- Rahman, H.; Vikram, P.; Hu, Y.; Asthana, S.; Tanaji, A.; Suryanarayanan, P.; Quadros, C.; Mehta, L.; Shahid, M.; Gkanogiannis, A.; et al. Mining Genomic Regions Associated with Agronomic and Biochemical Traits in Quinoa through GWAS. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9205. [CrossRef]

- Colque-Little, C.; Abondano, M.C.; Lund, O.S.; Amby, D.B.; Piepho, H.-P.; Andreasen, C.; Schmöckel, S.; Schmid, K. Genetic Variation for Tolerance to the Downy Mildew Pathogen Peronospora Variabilis in Genetic Resources of Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa). BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 41. [CrossRef]

- Trinh, M.D.L.; Visintainer, D.; Günther, J.; Østerberg, J.T.; da Fonseca, R.R.; Fondevilla, S.; Moog, M.W.; Luo, G.; Nørrevang, A.F.; Crocoll, C.; et al. Site-Directed Genotype Screening for Elimination of Antinutritional Saponins in Quinoa Seeds Identifies TSARL1 as a Master Controller of Saponin Biosynthesis Selectively in Seeds. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 2216–2234. [CrossRef]

- Maughan, P.J.; Chaney, L.; Lightfoot, D.J.; Cox, B.J.; Tester, M.; Jellen, E.N.; Jarvis, D.E. Mitochondrial and Chloroplast Genomes Provide Insights into the Evolutionary Origins of Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd.). Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 185. [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, S.-E. The Worldwide Potential for Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoaWilld.). Food Rev. Int. 2003, 19, 167–177. [CrossRef]

- Mandák, B.; Krak, K.; Vít, P.; Pavlíková, Z.; Lomonosova, M.N.; Habibi, F.; Wang, L.; Jellen, E.N.; Douda, J. How Genome Size Variation Is Linked with Evolution within Chenopodium Sensu Lato. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2016, 23, 18–32. [CrossRef]

- Mandák, B.; Krak, K.; Vít, P.; Lomonosova, M.N.; Belyayev, A.; Habibi, F.; Wang, L.; Douda, J.; Štorchová, H. Hybridization and Polyploidization within the Chenopodium Album Aggregate Analysed by Means of Cytological and Molecular Markers. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2018, 129, 189–201. [CrossRef]

- Štorchová, H.; Drabešová, J.; Cháb, D.; Kolář, J.; Jellen, E.N. The Introns in FLOWERING LOCUS T-LIKE (FTL) Genes Are Useful Markers for Tracking Paternity in Tetraploid Chenopodium Quinoa Willd. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2015, 62, 913–925. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, B.M.; Adhikary, D.; Maughan, P.J.; Emshwiller, E.; Jellen, E.N. Chenopodium Polyploidy Inferences from Salt Overly Sensitive 1 (SOS1) Data. Am. J. Bot. 2015, 102, 533–543. [CrossRef]

- Kolano, B.; McCann, J.; Orzechowska, M.; Siwinska, D.; Temsch, E.; Weiss-Schneeweiss, H. Molecular and Cytogenetic Evidence for an Allotetraploid Origin of Chenopodium Quinoa and C. Berlandieri (Amaranthaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2016, 100, 109–123. [CrossRef]

- Hinojosa, L.; Leguizamo, A.; Carpio, C.; Muñoz, D.; Mestanza, C.; Ochoa, J.; Castillo, C.; Murillo, A.; Villacréz, E.; Monar, C.; et al. Quinoa in Ecuador: Recent Advances under Global Expansion. Plants 2021, 10, 298. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, H.; Manhart, J. Crop/Weed Gene Flow:Chenopodium Quinoa Willd. andC. Berlandieri Moq. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1993, 86, 642–648. [CrossRef]

- Artificial Hybridization Among Species of Chenopodium Sect. Chenopodium on JSTOR Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2418372?origin=crossref&seq=1 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Heiser, C.B.; Nelson, D.C. On the Origin of the Cultivated Chenopods (Chenopodium). Genetics 1974, 78, 503–505. [CrossRef]

- Bazile, D. Le Quinoa, Les Enjeux d’une Conquête. 2015, 1–112.

- Rodriguez, J.P.; Bonifacio, A.; Gómez-Pando, L.R.; Mujica, A.; Sørensen, M. Cañahua (Chenopodium Pallidicaule Aellen). In Neglected and Underutilized Crops; Farooq, M., Siddique, K.H.M., Eds.; Academic Press, 2023; pp. 45–93 ISBN 978-0-323-90537-4.

- Samuels, M.E.; Lapointe, C.; Halwas, S.; Worley, A.C. Genomic Sequence of Canadian Chenopodium Berlandieri: A North American Wild Relative of Quinoa. Plants 2023, 12, 467. [CrossRef]

- Jellen, E.N.; Jarvis, D.E.; Hunt, S.P.; Mangelsen, H.H.; Maughan, P.J. New Seed Collections of North American Pitseed Goosefoot (Chenopodium Berlandieri) and Efforts to Identify Its Diploid Ancestors through Whole-Genome Sequencing. Int. J. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2019, 46, 187–196. [CrossRef]

- Mangelson, H.; Jarvis, D.E.; Mollinedo, P.; Rollano-Penaloza, O.M.; Palma-Encinas, V.D.; Gomez-Pando, L.R.; Jellen, E.N.; Maughan, P.J. The Genome of Chenopodium Pallidicaule: An Emerging Andean Super Grain. Appl. Plant Sci. 2019, 7, e11300. [CrossRef]

- Habibi, F.; Mosyakin, S.L.; Shynder, O.I.; Krak, K.; Čortan, D.; Filippi, G.A.; Mandák, B. Chenopodium Ucrainicum (Amaranthaceae), a New ‘BB’ Genome Diploid Species: Karyological, Cytological, and Molecular Evidence. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2023, 203, 401–410. [CrossRef]

- Curti, R. n.; Andrade, A. j.; Bramardi, S.; Velásquez, B.; Daniel Bertero, H. Ecogeographic Structure of Phenotypic Diversity in Cultivated Populations of Quinoa from Northwest Argentina. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2012, 160, 114–125. [CrossRef]

- Curti, R.N.; de la Vega, A.J.; Andrade, A.J.; Bramardi, S.J.; Bertero, H.D. Multi-Environmental Evaluation for Grain Yield and Its Physiological Determinants of Quinoa Genotypes across Northwest Argentina. Field Crops Res. 2014, 166, 46–57. [CrossRef]

- Curti, R.N.; de la Vega, A.J.; Andrade, A.J.; Bramardi, S.J.; Bertero, H.D. Adaptive Responses of Quinoa to Diverse Agro-Ecological Environments along an Altitudinal Gradient in North West Argentina. Field Crops Res. 2016, 189, 10–18. [CrossRef]

- Subedi, M.; Neff, E.; Davis, T.M. Developing Chenopodium Ficifolium as a Potential B Genome Diploid Model System for Genetic Characterization and Improvement of Allotetraploid Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa). BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 490. [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, C.D.; Maughan, P.J.; Jellen, E.N.; Davis, T.M. The Genome of Chenopodium Ficifolium: Developing Genetic Resources and a Diploid Model System for Allotetraploid Quinoa. G3 GenesGenomesGenetics 2025, 15, jkaf162. [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, D.E.; Sproul, J.S.; Navarro-Domínguez, B.; Krak, K.; Jaggi, K.; Huang, Y.-F.; Huang, T.-Y.; Lin, T.C.; Jellen, E.N.; Maughan, P.J. Chromosome-Scale Genome Assembly of the Hexaploid Taiwanese Goosefoot “Djulis” (Chenopodium Formosanum). Genome Biol. Evol. 2022, 14, evac120. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, H.D. Quinua and Relatives (Chenopodium Sect. Chenopodium Subsect. Cellulata). Econ. Bot. 1990, 44, 92–110.

- Wilson, H.D.; Heiser, C.B. The Origin and Evolutionary Relationships of ‘Huauzontle’ (Chenopodium Nuttaliae Safford), Domesticated Chenopod of Mexico. Am. J. Bot. 1979, 66, 198–206.

- Spengler, R.N.; Mueller, N.G. Grazing Animals Drove Domestication of Grain Crops. Nat. Plants 2019, 5, 656–662. [CrossRef]

- Langlie, B.S.; Hastorf, C.A.; Bruno, M.C.; Bermann, M.; Bonzani, R.M.; Condarco, W.C. Diversity In Andean Chenopodium Domestication: Describing A New Morphological Type From La Barca, Bolivia 1300-1250 B.C. J. Ethnobiol. 2011, 31, 72–88. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, N.G.; SpenglerIII, R.N.; Glenn, A.; Lama, K. Bison, Anthropogenic Fire, and the Origins of Agriculture in Eastern North America. Anthr. Rev. 2021, 8, 141–158. [CrossRef]

- Belcher, M.E.; Williams, D.; Mueller, N.G. Turning Over a New Leaf: Experimental Investigations into the Role of Developmental Plasticity in the Domestication of Goosefoot (Chenopodium Berlandieri) in Eastern North America. Am. Antiq. 2023, 88, 554–569. [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Gao, Y.; Zeng, F.; Zheng, C.; Ge, W.; Wan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wu, X. Evaluation of Pre-Harvest Sprouting (PHS) Resistance and Screening of High-Quality Varieties from Thirty-Seven Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd.) Resources in Chengdu Plain. Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 92, 2921–2936. [CrossRef]

- Craine, E.B.; Davies, A.; Packer, D.; Miller, N.D.; Schmöckel, S.M.; Spalding, E.P.; Tester, M.; Murphy, K.M. A Comprehensive Characterization of Agronomic and End-Use Quality Phenotypes across a Quinoa World Core Collection. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Tovar, J.C.; Quillatupa, C.; Callen, S.T.; Castillo, S.E.; Pearson, P.; Shamin, A.; Schuhl, H.; Fahlgren, N.; Gehan, M.A. Heating Quinoa Shoots Results in Yield Loss by Inhibiting Fruit Production and Delaying Maturity. Plant J. 2020, 102, 1058–1073. [CrossRef]

- Halwas, S.; Worley, A.C. Incorporating Chenopodium Berlandieri into a Seasonal Subsistence Pattern: Implications of Biological Traits for Cultural Choices. J. Ethnobiol. 2019, 39, 510–529. [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.D. The Economic Potential of Chenopodium Berlandieri in Prehistoric Eastern North America. J. Ethnobiol. 1987, 7, 29–54.

- Rojas, W. Multivariate Analysis of Genetic Diversity of Bolivian Quinoa Germplasm. Food Rev. Int. 2003, 19, 9–23.

- Otterbach, S.; Wellman, G.; Schmöckel, S.M. Saponins of Quinoa: Structure, Function and Opportunities. In The Quinoa Genome; Schmöckel, S.M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 119–138 ISBN 978-3-030-65237-1.

- Kollmar, M.; Böndel, K.B.; John, L.; Arold, S.; Schmid, K.; Jarvis, D.; Schmöckel, S.M.; Otterbach, S.L. Investigating the bHLH Transcription Factor TSARL1 as Marker and Regulator of Saponin Biosynthesis in Chenopodium Quinoa. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 7329–7339. [CrossRef]

- El Hazzam, K.; Hafsa, J.; Sobeh, M.; Mhada, M.; Taourirte, M.; EL Kacimi, K.; Yasri, A. An Insight into Saponins from Quinoa (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd): A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 1059. [CrossRef]

- Bustos, K.A.G.; Muñoz, S.S.; da Silva, S.S.; Alarcon, M.A.D.F.; dos Santos, J.C.; Andrade, G.J.C.; Hilares, R.T. Saponin Molecules from Quinoa Residues: Exploring Their Surfactant, Emulsifying, and Detergent Properties. Molecules 2024, 29, 4928. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Iafelice, G.; Lavini, A.; Pulvento, C.; Caboni, M.F.; Marconi, E. Phenolic Compounds and Saponins in Quinoa Samples (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd.) Grown under Different Saline and Nonsaline Irrigation Regimens. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 4620–4627. [CrossRef]

- FNA: Chenopodium Desiccatum vs. Chenopodium Simplex Available online: https://nwwildflowers.com/compare/?t=Chenopodium+desiccatum,+Chenopodium+simplex (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Catalá, R.; López-Cobollo, R.; Berbís, M.Á.; Jiménez-Barbero, J.; Salinas, J. Trimethylamine N-Oxide Is a New Plant Molecule That Promotes Abiotic Stress Tolerance. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabd9296. [CrossRef]

- Jellen, E.N.; Jarvis, D.E.; Hunt, S.P.; Mangelsen, H.H.; Maughan, P.J. New Seed Collections of North American Pitseed Goosefoot (Chenopodium Berlandieri) and Efforts to Identify Its Diploid Ancestors through Whole-Genome Sequencing. Int. J. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2019, 46, 187–196. [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Edwards, C.G.; Fellman, J.K.; Mattinson, D.S.; Navazio, J. Biosynthetic Origin of Geosmin in Red Beets (Beta Vulgaris L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 1026–1029. [CrossRef]

- Freidig, A.K.; Goldman, I.L. Geosmin (2β,6α-Dimethylbicyclo[4.4.0]Decan-1β-Ol) Production Associated with Beta Vulgaris Ssp. Vulgaris Is Cultivar Specific. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 2031–2036. [CrossRef]

- Zaroubi, L.; Ozugergin, I.; Mastronardi, K.; Imfeld, A.; Law, C.; Gélinas, Y.; Piekny, A.; Findlay, B.L. The Ubiquitous Soil Terpene Geosmin Acts as a Warning Chemical. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e00093-22. [CrossRef]

- Tararina, M.A.; Allen, K.N. Bioinformatic Analysis of the Flavin-Dependent Amine Oxidase Superfamily: Adaptations for Substrate Specificity and Catalytic Diversity. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432, 3269–3288. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Vázquez, G.; Osuna-Vallejo, V.; Castro-López, V.; Israde-Alcántara, I.; Bischoff, J.A. Changes in Vegetation Structure during the Pleistocene–Holocene Transition in Guanajuato, Central Mexico. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2019, 28, 81–91. [CrossRef]

- Caballero, M.; Ortega, B.; Lozano-García, S.; Montero, D.; Torres, E.; Soler, A.M. Environmental Changes in Central Mesoamerica in the Archaic and Formative Periods. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2025, 34, 669–684. [CrossRef]

- Aellen, P. Illustrierte Flora von Mitteleuropa; 2nd ed.; Hanser: Munich, Germany, 1960; Vol. 3;.

| Chenopodium Taxon | Common Name(s) | Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| berlandieri subsp. berlandieri | Pitseed goosefoot | |

| var. berlandieri | South Texas | |

| var. boscianum | Gulf of Mexico Coast | |

| var. bushianum | Eastern North America | |

| var. macrocalycium | New England Coast | |

| var. sinuatum | Mojave and Sonoran Deserts | |

| var. wilsonii1 | Eastern Oklahoma | |

| var. zschackei | Great Basin, Rocky Mountains, western Great Plains | |

| berlandieri subsp. nuttaliae | ||

| var. nuttaliae | Huauzontle, chia | South-central Mexico |

| var. pueblense1 | quelite | South-central Mexico |

| hircinum | Avian goosefoot | Southern South America |

| quinoa subsp. melanospermum | Ajara, ayara | Quinoa fields |

| quinoa subsp. milleanum | Ajara, ayara | Quinoa fields |

| quinoa subsp. quinoa | Quinoa, quinua, dzawe, jirwa | Andes, South-central Chile |

| Chenopodium Taxon | Subgroup | Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| albescens Small | Texas; South America (?) | |

| arizonicum Standl. | NEOM | Arizona, New Mexico |

| atrovirens Rydb. | Great Basin, Rocky Mts. | |

| aureum Benet-Pierce | HIAN | Sierra Nevada Mts. |

| brandegeeae Benet-Pierce | HIAN | S California |

| bryoniifolium | NE Asia | |

| carnosolum Moq | S Patagonia, Andes Mts. | |

| cordobense Aellen | W Argentina | |

| cycloides A. Nelson | Southern Great Plains | |

| desiccatum A. Nelson | W North America, South America | |

| eastwoodiae Benet-Pierce | HIAN | Sierra Nevada Mts. |

| ficifolium Sm. | BB | Eurasia; global weed |

| flabellifolium Standl. | NEOM | Isla San Martin (Mexico) |

| foggii Wahl | Appalachian Mts. | |

| fremontii S. Wats. | W North America | |

| hians Wahl | HIAN | W North America |

| howellii Benet-Pierce | HIAN | Sierra Nevada Mts. |

| incanum A. Heller | Great Basin, Arizona, Great Plains | |

| incognitum Wahl | HIAN | Great Basin, Rocky Mts. |

| lenticulare Aellen | NEOM | Chihuahuan Desert |

| leptophyllum (Nutt ex Moq) B.D. Jacks | W North America | |

| lineatum Benet-Pierce | HIAN | Sierra Nevada Mts. |

| littoreum Benet-Pierce & M.G. Simpson | Central California Coast | |

| luteum Benet-Pierce | HIAN | Sierra Nevada Mts. |

| neomexicanum Standl. | NEOM | Arizona, New Mexico |

| nevadense Standl. | W Great Basin | |

| nitens Benet-Pierce & M.G. Simpson | W North America | |

| obscurum Aellen | W Argentina | |

| pallescens Standl. | Great Plains | |

| pallidicaule Aellen | Andes Mts.; incl. cultigens (cañahua) | |

| palmeri Standl. | NEOM | Sonoran Desert |

| papulosum Moq | W Argentina | |

| parryi Standl. | NEOM | Sierra Madre Oriental Mts. |

| petiolare Kunth | Andes Mts., Peruvian Coast | |

| philippianum Aellen | Andes Mts. | |

| pilcomayense Aellen | N Pampas, Gran Chaco | |

| pratericola Rydb. | W North America, South America | |

| ruiz-lealii Aellen | W Argentina | |

| sandersii Benet-Pierce | HIAN | S California |

| scabricaule Speg. | Patagonia | |

| simpsonii Benet-Pierce | HIAN | S California |

| sonorense Benet-Pierce & M.G. Simpson | NEOM | Sonoran Desert |

| standleyanum Aellen | E North America | |

| subglabrum (S. Watson) A. Nelson | Great Plains, Great Basin | |

| suecicum Murr | BB | Alaska, Eurasia; global weed |

| twisselmannii Benet-Pierce | HIAN | Sierra Nevada Mts. |

| ucrainicum Mosyakin & Mandák | BB | E Europe |

| wahlii Benet-Pierce | HIAN | S California |

| watsonii A. Nelson | NEOM | Colorado Plateau, Great Plains |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).