Submitted:

13 November 2025

Posted:

14 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

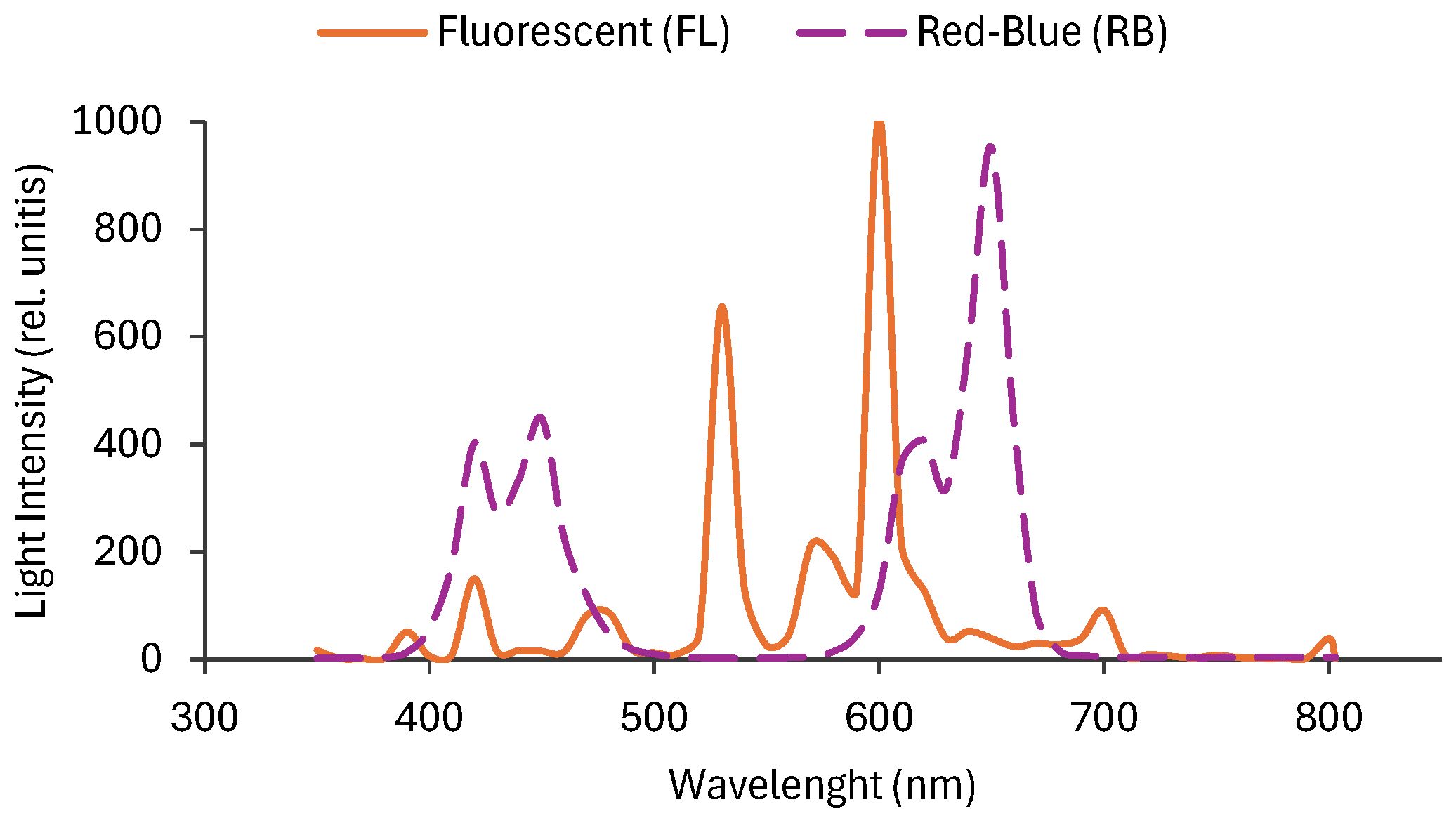

2.1. Plant Growth Conditions and Experimental Design

2.2. Determination of Total Polyphenol, Flavonoid and Anthocyanin Content

2.3. Determination of Total Carotenoid, Lycopene and Ascorbic Acid Content

2.4. Antioxidant Capacity (FRAP assay) and Free Radical Scavenging Activity (DPPH Assay)

2.5. Cell Cultures

2.6. Extract Treatment of Cell Cultures

2.7. Cell Exposure to Clinical Photons

2.8. Measurement of Radiation-Induced DNA Damage

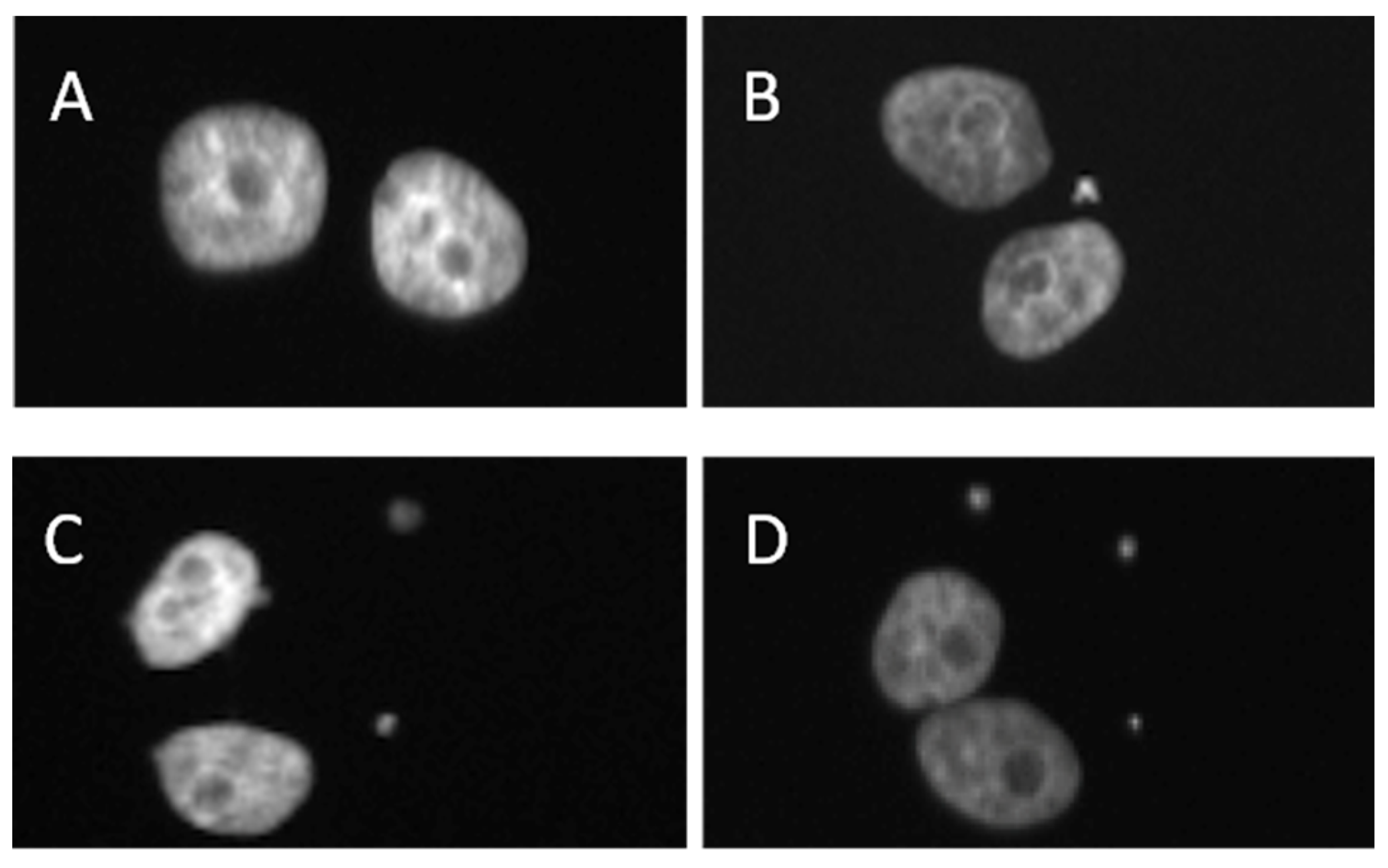

2.8.1. Micronucleus Frequency Measurement

2.9. Determination of Radiation-Induced Oxidative Stress

2.9.1. ROS Level Measurement

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

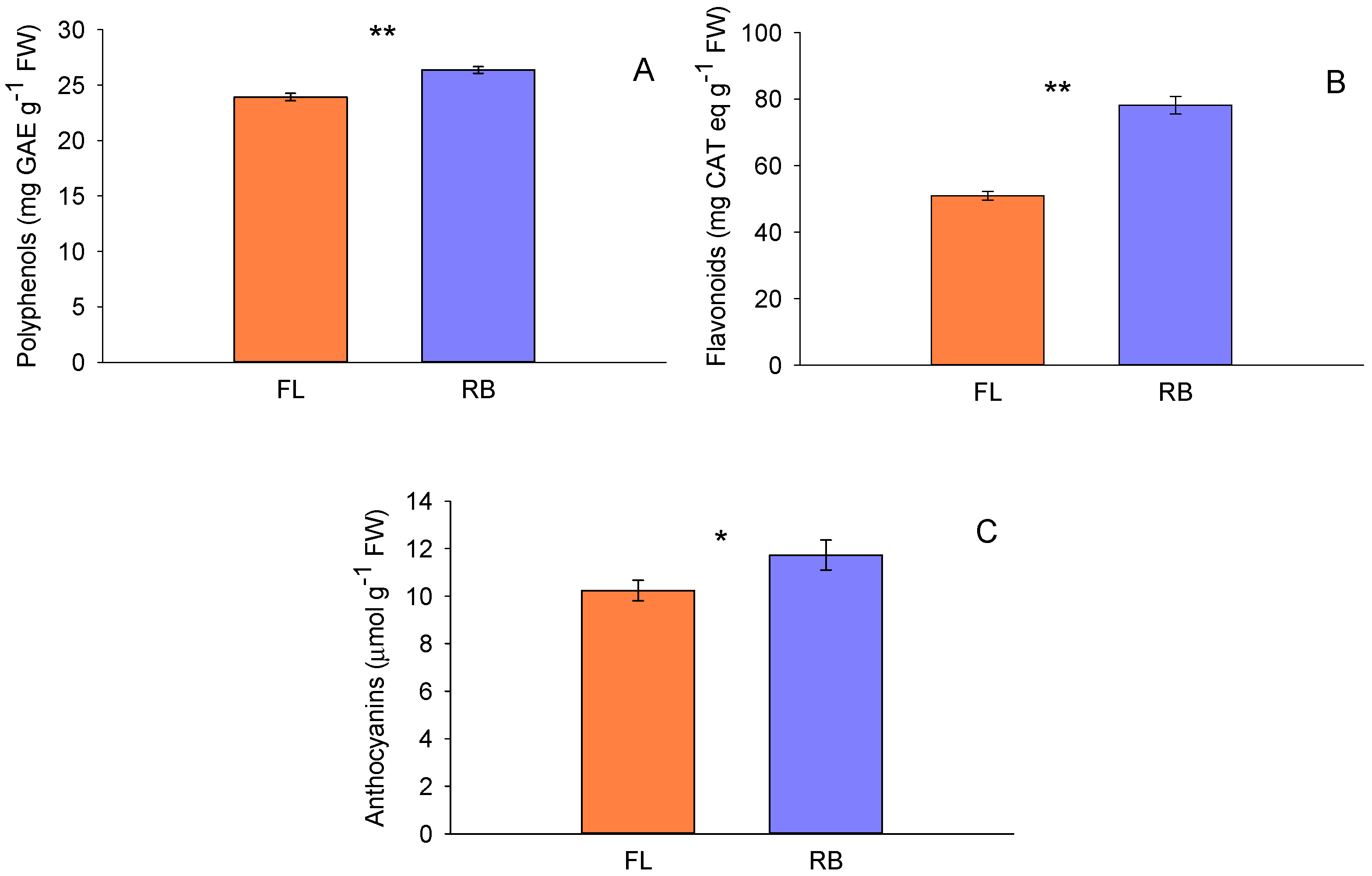

3.1. Total Phenolic Compounds

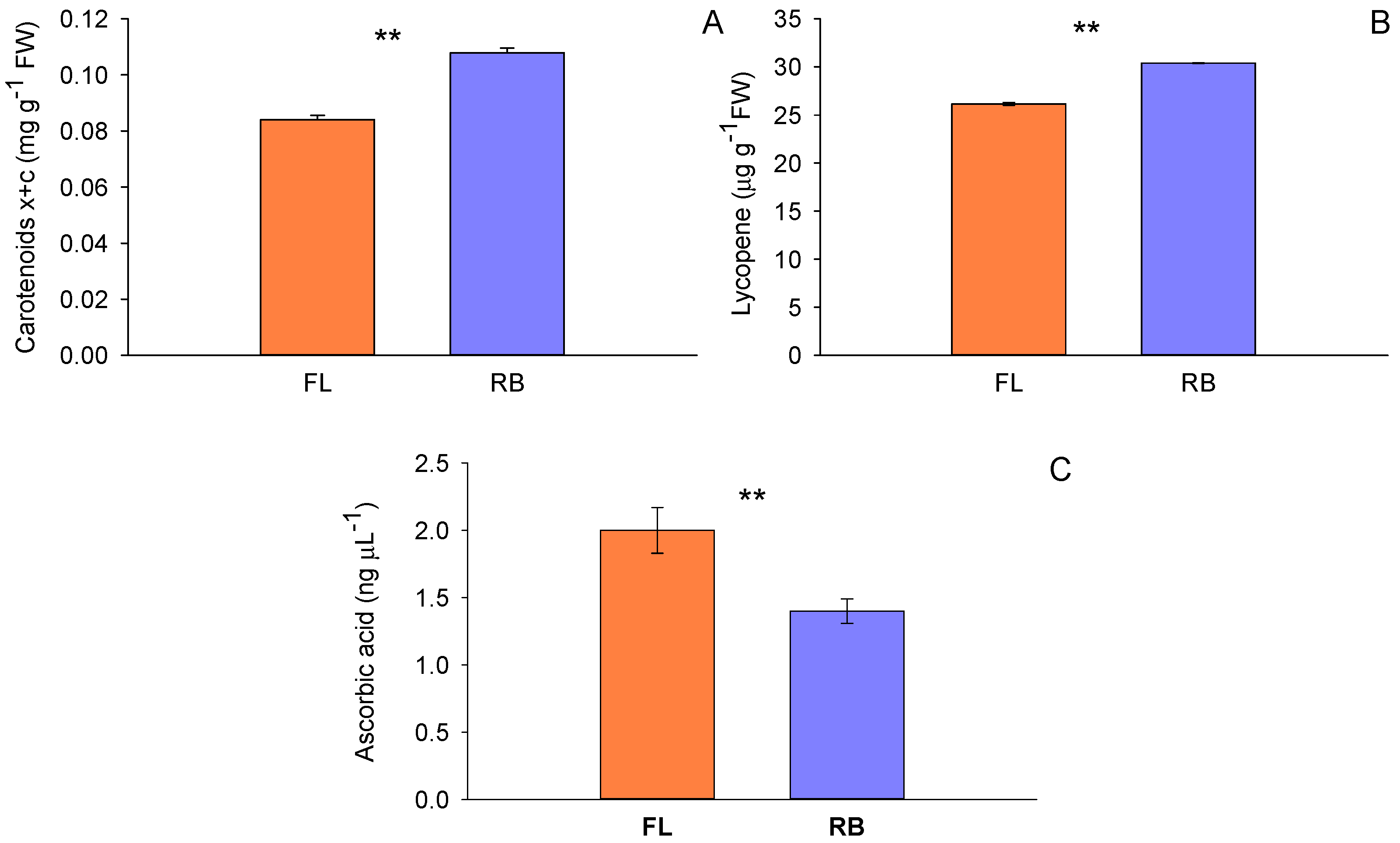

3.2. Total Carotenoids, Lycopene and Ascorbic Acid

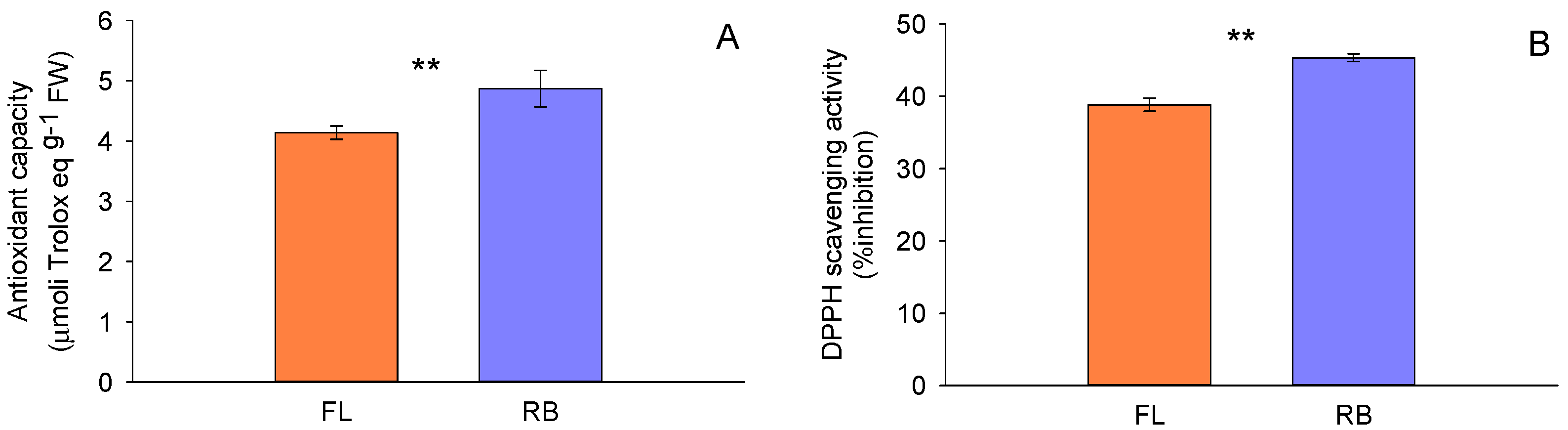

3.3. Sample Antioxidant Activity

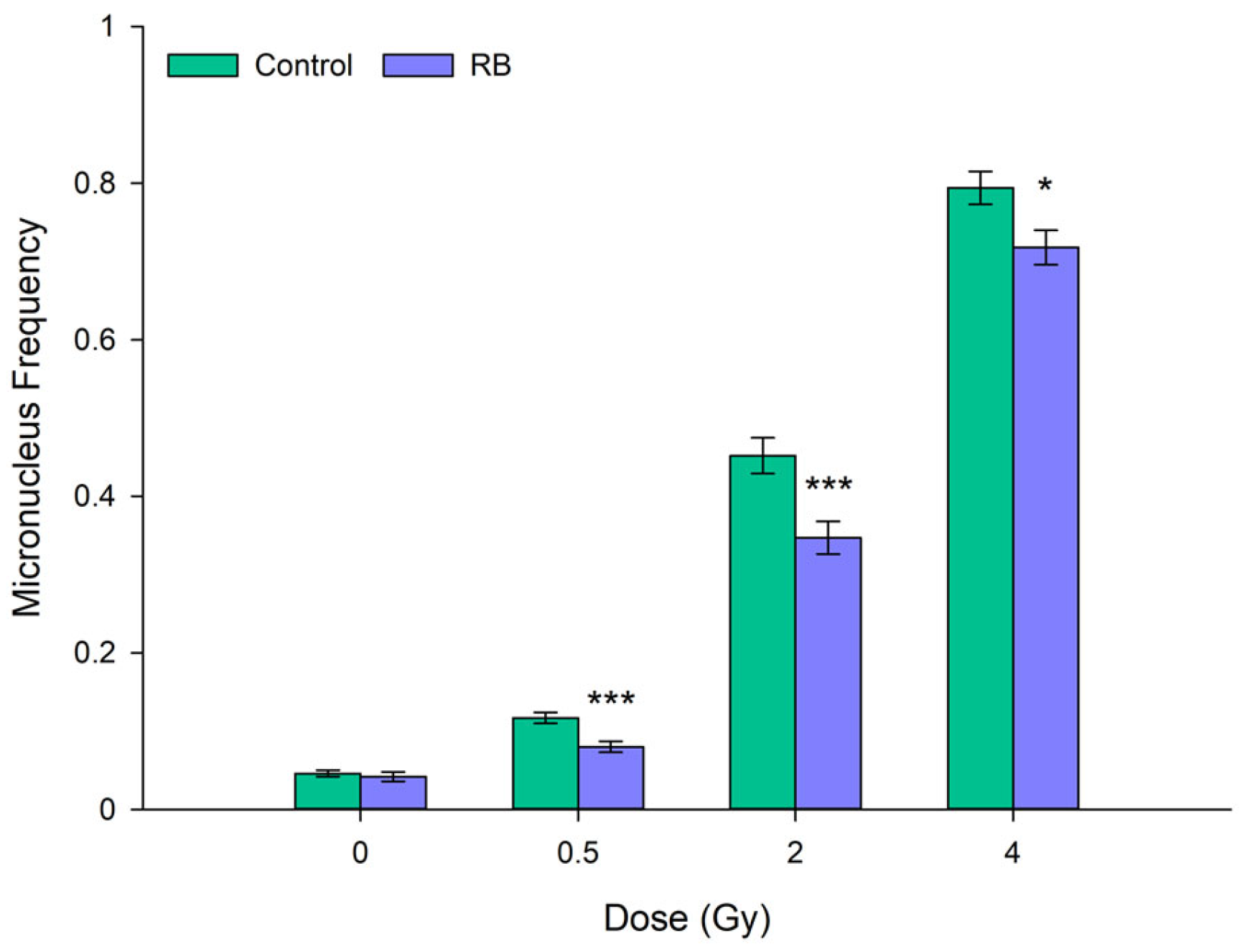

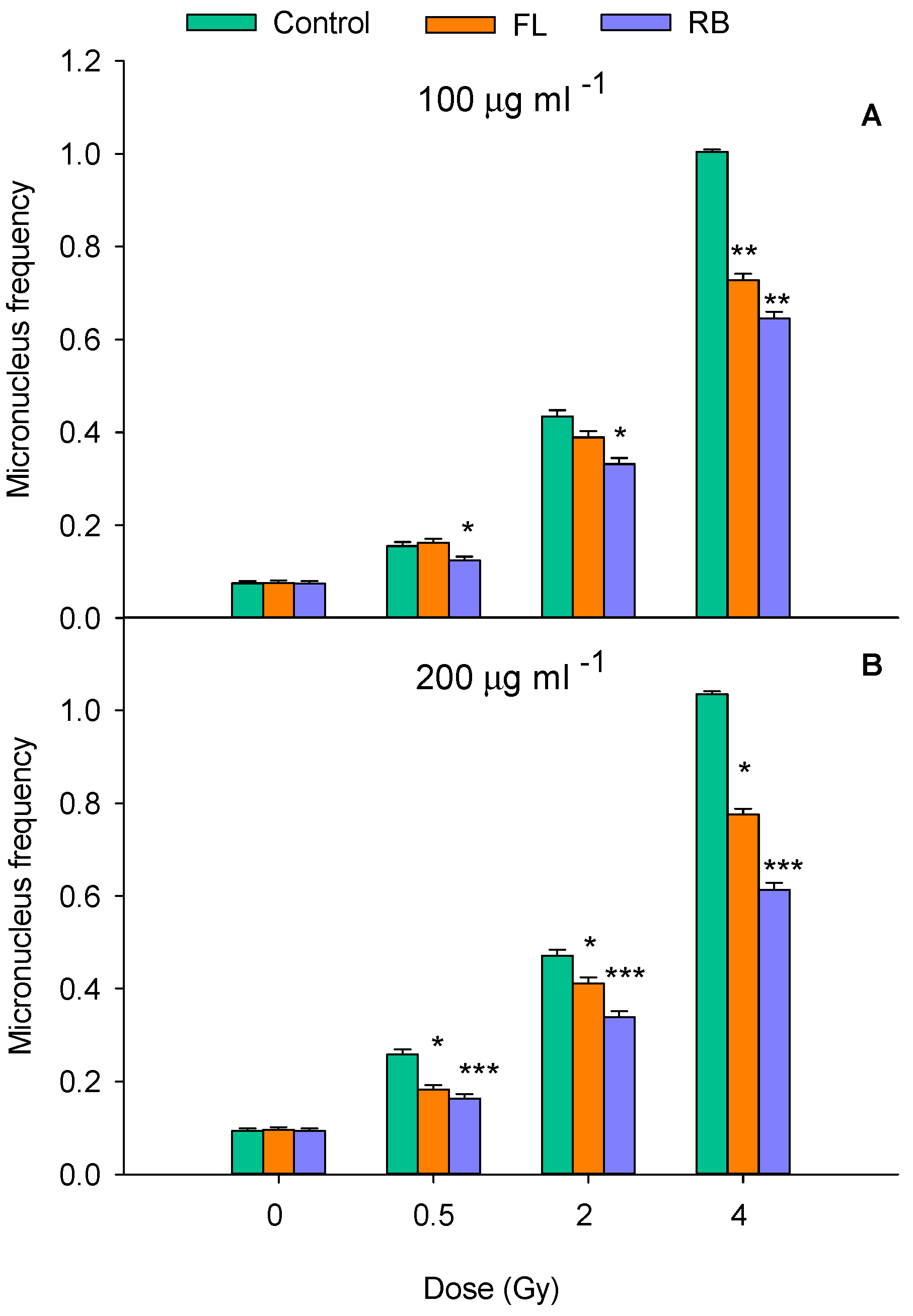

3.4. Radiation-Induced Genotoxicity

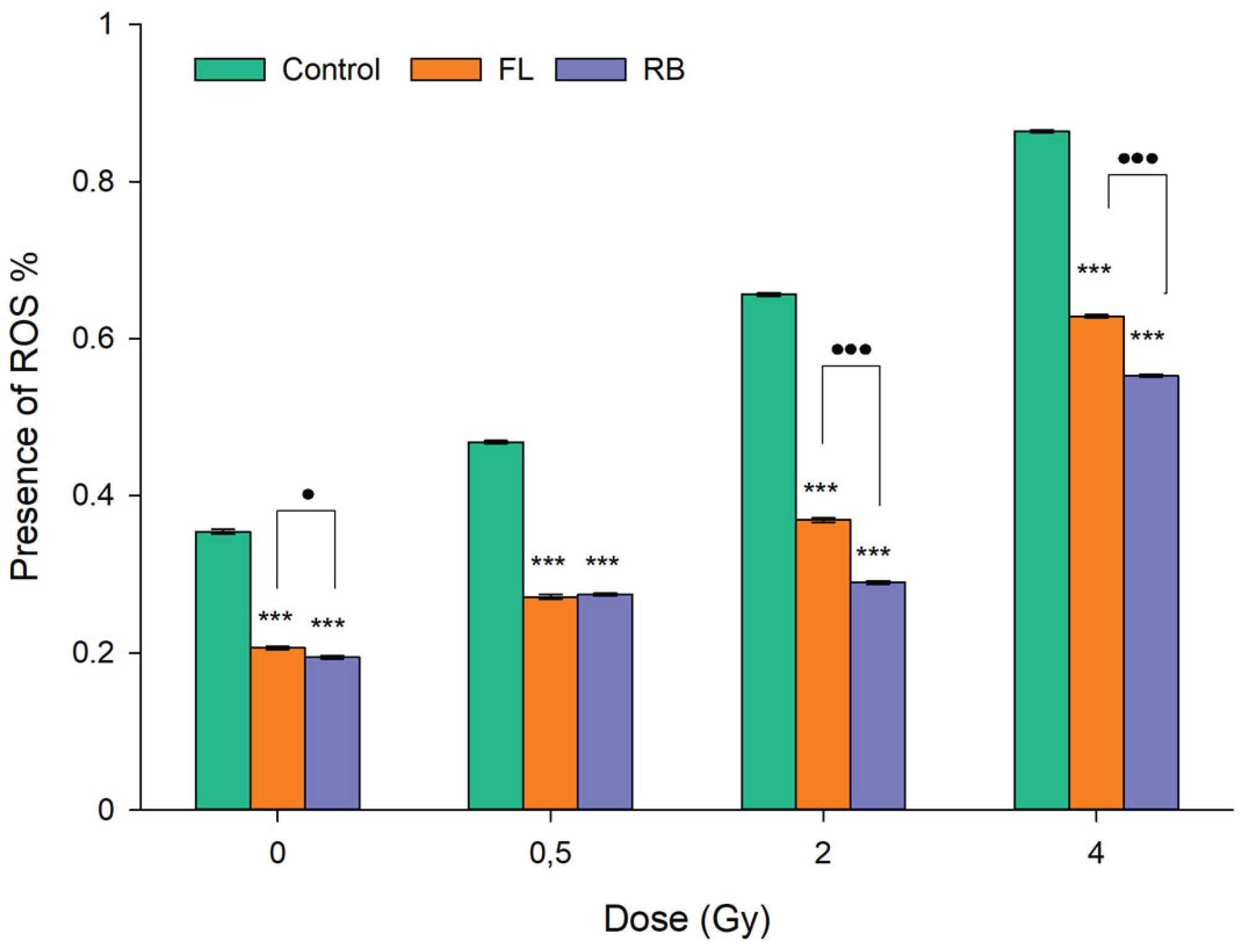

3.5. Oxidative Stress Levels

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- investigating the molecular pathways by which RB light enhances the synthesis of radioprotective polyphenols in tomato fruits;

- testing whether similar light-induced biochemical profiles can be obtained in other edible plant species;

- developing standardized tomato-derived extracts or formulations to reduce radiotherapy-induced normal tissue toxicity.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salehi, B.; Sharifi-Rad, R.; Sharopov, F.; Namiesnik, J.; Roointan, A.; Kamle, M.; Kumar, P.; Martins, N.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Beneficial Effects and Potential Risks of Tomato Consumption for Human Health: An Overview. Nutrition 2019, 62, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbadrawy, E.; Sello, A. Evaluation of Nutritional Value and Antioxidant Activity of Tomato Peel Extracts. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2016, 9, S1010–S1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, I.I.; Abdullahi, N.; Abdu, A.M.; Ibrahim, A.S. Proximate, Mineral and Vitamin Analysis of Fresh and Canned Tomato. Biosci Biotechnol Res Asia 2016, 13, 1163–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, P.; Sharma, A.; Singh, B.; Nagpal, A.K. Bioactivities of Phytochemicals Present in Tomato. J Food Sci Technol 2018, 55, 2833–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.M.; Koutsidis, G.; Lodge, J.K.; Ashor, A.W.; Siervo, M.; Lara, J. Lycopene and Tomato and Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Epidemiological Evidence. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2019, 59, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wu, X.; Zhuang, W.; Xia, L.; Chen, Y.; Wu, C.; Rao, Z.; Du, L.; Zhao, R.; Yi, M.; et al. Tomato and Lycopene and Multiple Health Outcomes: Umbrella Review. Food Chem 2021, 343, 128396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.-A.; Hayden, M.M.; Bannerman, S.; Jansen, J.; Crowe-White, K.M. Anti-Apoptotic Effects of Carotenoids in Neurodegeneration. Molecules 2020, 25, 3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-González, I.; García-Alonso, J.; Periago, M.J. Bioactive Compounds of Tomato: Cancer Chemopreventive Effects and Influence on the Transcriptome in Hepatocytes. J Funct Foods 2018, 42, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faramarzi, S.; Piccolella, S.; Manti, L.; Pacifico, S. Could Polyphenols Really Be a Good Radioprotective Strategy? Molecules 2021, 26, 4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta Gupta, S.; Jatothu, B. Fundamentals and Applications of Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDs) in in Vitro Plant Growth and Morphogenesis. Plant Biotechnol Rep 2013, 7, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Iersel, M.W. Optimizing LED Lighting in Controlled Environment Agriculture. In Light Emitting Diodes for Agriculture. In Light Emitting Diodes for Agriculture; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2017; pp. 59–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hossen, Md.S.; Ali, Md.Y.; Jahurul, M.H.A.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Gan, S.H.; Khalil, Md.I. Beneficial Roles of Honey Polyphenols against Some Human Degenerative Diseases: A Review. Pharmacological Reports 2017, 69, 1194–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, M.; Ezura, H. Profiling of Melatonin in the Model Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.) Cultivar Micro-Tom. J Pineal Res 2009, 46, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arena, C.; Vitale, E.; Hay Mele, B.; Cataletto, P.R.; Turano, M.; Simoniello, P.; De Micco, V. Suitability of Solanum Lycopersicum L. ‘Microtom’ for Growth in Bioregenerative Life Support Systems: Exploring the Effect of High- LET Ionising Radiation on Photosynthesis, Leaf Structure and Fruit Traits. Plant Biol 2019, 21, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, E.; Velikova, V.; Tsonev, T.; Costanzo, G.; Paradiso, R.; Arena, C. Manipulation of Light Quality Is an Effective Tool to Regulate Photosynthetic Capacity and Fruit Antioxidant Properties of Solanum Lycopersicum L. Cv. ‘Microtom’ in a Controlled Environment. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, E.; Vitale, L.; Costanzo, G.; Velikova, V.; Tsonev, T.; Simoniello, P.; De Micco, V.; Arena, C. Light Spectral Composition Influences Structural and Eco-Physiological Traits of Solanum Lycopersicum L. Cv. ‘Microtom’ in Response to High-LET Ionizing Radiation. Plants 2021, 10, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta Gupta, S.; Jatothu, B. Fundamentals and Applications of Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDs) in in Vitro Plant Growth and Morphogenesis. Plant Biotechnol Rep 2013, 7, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Iersel, M.W. Optimizing LED Lighting in Controlled Environment Agriculture. In Light Emitting Diodes for Agriculture. In Light Emitting Diodes for Agriculture; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2017; pp. 59–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hay Mele, B.; Vitale, E.; Velikova, V.; Tsonev, T.; Fontanarosa, C.; Spinelli, M.; Amoresano, A.; Arena, C. Harnessing Light Wavelengths to Enrich Health-Promoting Molecules in Tomato Fruits. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolillo, I.; Costanzo, G.; Delicato, A.; Villano, F.; Arena, C.; Calabrò, V. Light Quality Potentiates the Antioxidant Properties of Brassica Rapa Microgreen Extracts against Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage in Human Cells. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, G.; Vitale, E.; Iesce, M.R.; Spinelli, M.; Fontanarosa, C.; Paradiso, R.; Amoresano, A.; Arena, C. Modulation of Antioxidant Compounds in Fruits of Citrus Reticulata Blanco Using Postharvest LED Irradiation. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Wahab, M.; Gondhowiardjo, S.S.; Rosa, A.A.; Lievens, Y.; El-Haj, N.; Polo Rubio, J.A.; Prajogi, G. Ben; Helgadottir, H.; Zubizarreta, E.; Meghzifene, A.; et al. Global Radiotherapy: Current Status and Future Directions—White Paper. JCO Glob Oncol 2021, 827–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, V.C.; Fede, F.; Bortolussi, S.; Cansolino, L.; Ferrari, C.; Formicola, E.; Postuma, I.; Manti, L. Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization-Based Chromosome Aberration Analysis Unveils the Mechanistic Basis for Boron-Neutron Capture Therapy’s Radiobiological Effectiveness. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillaci, F.; Anzalone, A.; Cirrone, G.A.P.; Carpinelli, M.; Cuttone, G.; Cutroneo, M.; De Martinis, C.; Giove, D.; Korn, G.; Maggiore, M.; et al. ELIMED, MEDical and Multidisciplinary Applications at ELI-Beamlines. J Phys Conf Ser 2014, 508, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bláha, P.; Feoli, C.; Agosteo, S.; Calvaruso, M.; Cammarata, F.P.; Catalano, R.; Ciocca, M.; Cirrone, G.A.P.; Conte, V.; Cuttone, G.; et al. The Proton-Boron Reaction Increases the Radiobiological Effectiveness of Clinical Low- and High-Energy Proton Beams: Novel Experimental Evidence and Perspectives. Front Oncol 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardamuro, V.; Faramarzi, B.; Moggio, M.; Elia, V.C.; Portaccio, M.; Diano, N.; Manti, L.; Lepore, M. Analysis of the X-Ray Induced Changes in Lipids Extracted from Hepatocarcinoma Cells by Means of ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy. Vib Spectrosc 2024, 132, 103697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchan, W.T.; Pitroda, S.P.; Weichselbaum, R.R. Treatment of Cancer with Radio-Immunotherapy: What We Currently Know and What the Future May Hold. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 9573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sala, C.; Tarozzi, M.; Simonetti, G.; Pazzaglia, M.; Cammarata, F.P.; Russo, G.; Acquaviva, R.; Cirrone, G.A.P.; Petringa, G.; Catalano, R.; et al. Impact on the Transcriptome of Proton Beam Irradiation Targeted at Healthy Cardiac Tissue of Mice. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessonnier, T.; Filosa, D.I.; Karle, C.; Baltazar, F.; Manti, L.; Glimelius, L.; Haberer, T.; Abdollahi, A.; Debus, J.; Mein, S.; et al. First Dosimetric and Biological Verification for Spot-Scanning Hadron Arc Radiation Therapy With Carbon Ions. Adv Radiat Oncol 2024, 9, 101611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jenrow, K.A.; Brown, S.L. Mechanisms of Radiation-Induced Normal Tissue Toxicity and Implications for Future Clinical Trials. Radiat Oncol J 2014, 32, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patyar, R.R.; Patyar, S. Role of Drugs in the Prevention and Amelioration of Radiation Induced Toxic Effects. Eur J Pharmacol 2018, 819, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzam, E.I.; Jay-Gerin, J.-P.; Pain, D. Ionizing Radiation-Induced Metabolic Oxidative Stress and Prolonged Cell Injury. Cancer Lett 2012, 327, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sueiro-Benavides, R.A.; Leiro-Vidal, J.M.; Salas-Sánchez, A.Á.; Rodríguez-González, J.A.; Ares-Pena, F.J.; López-Martín, M.E. Radiofrequency at 2.45 GHz Increases Toxicity, pro-Inflammatory and Pre-Apoptotic Activity Caused by Black Carbon in the RAW 264.7 Macrophage Cell Line. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 765, 142681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yuan, H.; Li, L.; Li, Q.; Lin, P.; Li, K. Oxidative Stress and Reprogramming of Lipid Metabolism in Cancers. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravatà, V.; Minafra, L.; Cammarata, F.P.; Pisciotta, P.; Lamia, D.; Marchese, V.; Petringa, G.; Manti, L.; Cirrone, G.A.; Gilardi, M.C.; et al. Gene Expression Profiling of Breast Cancer Cell Lines Treated with Proton and Electron Radiations. Br J Radiol 2018, 20170934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravatà, V.; Cammarata, F.P.; Minafra, L.; Pisciotta, P.; Scazzone, C.; Manti, L.; Savoca, G.; Petringa, G.; Cirrone, G.A.P.; Cuttone, G.; et al. Proton-Irradiated Breast Cells: Molecular Points of View. J Radiat Res 2019, 60, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, E.; Velikova, V.; Tsonev, T.; Costanzo, G.; Paradiso, R.; Arena, C. Manipulation of Light Quality Is an Effective Tool to Regulate Photosynthetic Capacity and Fruit Antioxidant Properties of Solanum Lycopersicum L. Cv. ‘Microtom’ in a Controlled Environment. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, E.; Velikova, V.; Tsonev, T.; Costanzo, G.; Paradiso, R.; Arena, C. Manipulation of Light Quality Is an Effective Tool to Regulate Photosynthetic Capacity and Fruit Antioxidant Properties of Solanum Lycopersicum L. Cv. ‘Microtom’ in a Controlled Environment. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulehi, I.; Bourgou, S.; Ourghemmi, I.; Tounsi, M.S. Variety and Ripening Impact on Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Mandarin (Citrus Reticulate Blanco) and Bitter Orange (Citrus Aurantium L.) Seeds Extracts. Ind Crops Prod 2012, 39, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Ricardo-da-Silva, J.M.; Spranger, I. Critical Factors of Vanillin Assay for Catechins and Proanthocyanidins. J Agric Food Chem 1998, 46, 4267–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancinelli, A.L.; Rabino, I. Photocontrol of Anthocyanin Synthesis. Plant Physiol 1975, 56, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.-C.; Chen, S.-J.; Hsu, C.-K.; Chang, C.-T.; Chou, S.-T. Studies on the Antioxidative Activity of Graptopetalum Paraguayense E. Walther. Food Chem 2005, 91, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. Chlorophylls and Carotenoids: Pigments of Photosynthetic Biomembranes. In; 1987; pp. 350–382.

- Fish, W.W.; Perkins-Veazie, P.; Collins, J.K. A Quantitative Assay for Lycopene That Utilizes Reduced Volumes of Organic Solvents. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2002, 15, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.R.; Fish, W.W.; Perkins-Veazie, P. A Rapid Spectrophotometric Method for Analyzing Lycopene Content in Tomato and Tomato Products. Postharvest Biol Technol 2003, 28, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, G.; Vitale, E.; Iesce, M.R.; Naviglio, D.; Amoresano, A.; Fontanarosa, C.; Spinelli, M.; Ciaravolo, M.; Arena, C. Antioxidant Properties of Pulp, Peel and Seeds of Phlegrean Mandarin (Citrus Reticulata Blanco) at Different Stages of Fruit Ripening. Antioxidants 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, B.; Kaur, C.; Khurdiya, D.S.; Kapoor, H.C. Antioxidants in Tomato (Lycopersium Esculentum) as a Function of Genotype. Food Chem 2004, 84, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudonné, S.; Vitrac, X.; Coutiére, P.; Woillez, M.; Mérillon, J.M. Comparative Study of Antioxidant Properties and Total Phenolic Content of 30 Plant Extracts of Industrial Interest Using DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, SOD, and ORAC Assays. J Agric Food Chem 2009, 57, 1768–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, J.; Muthuswamy, S.K.; Brugge, J.S. Morphogenesis and Oncogenesis of MCF-10A Mammary Epithelial Acini Grown in Three-Dimensional Basement Membrane Cultures. Methods 2003, 30, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenech, M.; Chang, W.P.; Kirsch-Volders, M.; Holland, N.; Bonassi, S.; Zeiger, E. HUMN Project: Detailed Description of the Scoring Criteria for the Cytokinesis-Block Micronucleus Assay Using Isolated Human Lymphocyte Cultures; 2003; Vol. 534;

- Fenech, M. The Cytokinesis-Block Micronucleus Technique and Its Application to Genotoxicity Studies in Human Populations; 1993; Vol. 101;

- Fenech, M. The in Vitro Micronucleus Technique; 2000; Vol. 455;

- Njus, D.; Kelley, P.M.; Tu, Y.-J.; Schlegel, H.B. Ascorbic Acid: The Chemistry Underlying Its Antioxidant Properties. Free Radic Biol Med 2020, 159, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntagkas, N.; Woltering, E.; Nicole, C.; Labrie, C.; Marcelis, L.F.M. Light Regulation of Vitamin C in Tomato Fruit Is Mediated through Photosynthesis. Environ Exp Bot 2019, 158, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagna, A.; Dall’Asta, C.; Chiavaro, E.; Galaverna, G.; Ranieri, A. Effect of Post-Harvest UV-B Irradiation on Polyphenol Profile and Antioxidant Activity in Flesh and Peel of Tomato Fruits. Food Bioproc Tech 2014, 7, 2241–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Liu, H.; Sun, G.; Chen, R. Effects of Light Quality on The Quality Formation of Tomato Fruits; 2016.

- Racchi, M. Antioxidant Defenses in Plants with Attention to Prunus and Citrus Spp. Antioxidants 2013, 2, 340–369. Antioxidants 2013, 2, 340–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Shi, L.; Chen, W.; Cao, S.; Su, X.; Yang, Z. Effect of Blue Light Treatment on Fruit Quality, Antioxidant Enzymes and Radical-Scavenging Activity in Strawberry Fruit. Sci Hortic 2014, 175, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Kubota, C. Effects of Supplemental Light Quality on Growth and Phytochemicals of Baby Leaf Lettuce. Environ Exp Bot 2009, 67, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Zhang, L.; Setiawan, C.K.; Yamawaki, K.; Asai, T.; Nishikawa, F.; Maezawa, S.; Sato, H.; Kanemitsu, N.; Kato, M. Effect of Red and Blue LED Light Irradiation on Ascorbate Content and Expression of Genes Related to Ascorbate Metabolism in Postharvest Broccoli. Postharvest Biol Technol 2014, 94, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giliberto, L.; Perrotta, G.; Pallara, P.; Weller, J.L.; Fraser, P.D.; Bramley, P.M.; Fiore, A.; Tavazza, M.; Giuliano, G. Manipulation of the Blue Light Photoreceptor Cryptochrome 2 in Tomato Affects Vegetative Development, Flowering Time, and Fruit Antioxidant Content. Plant Physiol 2005, 137, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi-Kaneko, K.; Takase, M.; Kon, N.; Fujiwara, K.; Kurata, K. Effect of Light Quality on Growth and Vegetable Quality in Leaf Lettuce, Spinach and Komatsuna. Environment Control in Biology 2007, 45, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaleye, M.; Crown, O.; Akinmoladun, A.; Akindahunsi, A. Rutin and Quercetin Show Greater Efficacy than Nifedipin in Ameliorating Hemodynamic, Redox, and Metabolite Imbalances in Sodium Chloride-Induced Hypertensive Rats. Hum Exp Toxicol 2014, 33, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Rocha, E.V.; Falchetti, F.; Pernomian, L.; de Mello, M.M.B.; Parente, J.M.; Nogueira, R.C.; Gomes, B.Q.; Bertozi, G.; Sanches-Lopes, J.M.; Tanus-Santos, J.E.; et al. Quercetin Decreases Cardiac Hypertrophic Mediators and Maladaptive Coronary Arterial Remodeling in Renovascular Hypertensive Rats without Improving Cardiac Function. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2023, 396, 939–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernatova, I. Biological Activities of (−)-Epicatechin and (−)-Epicatechin-Containing Foods: Focus on Cardiovascular and Neuropsychological Health. Biotechnol Adv 2018, 36, 666–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmani, A.H.; Alsahli, M.A.; Almatroudi, A.; Almogbel, M.A.; Khan, A.A.; Anwar, S.; Almatroodi, S.A. The Potential Role of Apigenin in Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Molecules 2022, 27, 6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, G. Protection against Developing Type 2 Diabetes by Coffee Consumption: Assessment of the Role of Chlorogenic Acid and Metabolites on Glycaemic Responses. Food Funct 2020, 11, 4826–4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Ali, A.; Ali, J.; Sahni, J.K.; Baboota, S. Rutin: Therapeutic Potential and Recent Advances in Drug Delivery. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2013, 22, 1063–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Mishra, A.P.; Nigam, M.; Sener, B.; Kilic, M.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Fokou, P.V.T.; Martins, N.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Resveratrol: A Double-Edged Sword in Health Benefits. Biomedicines 2018, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, Y.B.; Li, X.; Choi, S.R.; Park, S.; Park, J.S.; Lim, Y.P.; Park, S.U. Accumulation of Phenylpropanoids by White, Blue, and Red Light Irradiation and Their Organ-Specific Distribution in Chinese Cabbage (Brassica Rapa Ssp. Pekinensis). J Agric Food Chem 2015, 63, 6772–6778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, J.-R.; Liu, J.; Fu, L.; Shu, T.; Yang, L.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, Z.-H.; Bai, L.-P. Anti-Entry Activity of Natural Flavonoids against SARS-CoV-2 by Targeting Spike RBD. Viruses 2023, 15, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costanzo, G.; Iesce, M.R.; Naviglio, D.; Ciaravolo, M.; Vitale, E.; Arena, C. Comparative Studies on Different Citrus Cultivars: A Revaluation of Waste Mandarin Components. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, A.; Itaki, C.; Saito, A.; Yonezawa, T.; Aizawa, K.; Hirai, A.; Suganuma, H.; Miura, T.; Mariya, Y.; Haghdoost, S. Possible Benefits of Tomato Juice Consumption: A Pilot Study on Irradiated Human Lymphocytes from Healthy Donors. Nutr J 2017, 16, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ruysscher, D.; Niedermann, G.; Burnet, N.G.; Siva, S.; Lee, A.W.M.; Hegi-Johnson, F. Author Correction: Radiotherapy Toxicity. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manti, L.; Durante, M.; Grossi, G.; Ortenzia, O.; Pugliese, M.; Scampoli, P.; Gialanella, G. Measurements of Metaphase and Interphase Chromosome Aberrations Transmitted through Early Cell Replication Rounds in Human Lymphocytes Exposed to Low-LET Protons and High-LET 12C Ions. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis 2006, 596, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manti, L.; Jamali, M.; Prise, K.M.; Michael, B.D.; Trott, K.R. Genomic Instability in Chinese Hamster Cells after Exposure to X Rays or Alpha Particles of Different Mean Linear Energy Transfer. Radiat Res 1997, 147, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaki, T.; Millar, R.; Hiley, C.T.; Boulton, S.J. Micronuclei Induced by Radiation, Replication Stress, or Chromosome Segregation Errors Do Not Activate CGAS-STING. Mol Cell 2024, 84, 2203–2213.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Liu, S.; Yang, L.; Song, P.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Yan, X.; Dong, Q. Roles of Reactive Oxygen Species in Inflammation and Cancer. MedComm (Beijing) 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faramarzi, S.; Piccolella, S.; Manti, L.; Pacifico, S. Could Polyphenols Really Be a Good Radioprotective Strategy? Molecules 2021, 26, 4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongtip, A.; Mosaleeyanon, K.; Janta, S.; Wanichananan, P.; Chutimanukul, P.; Thepsilvisut, O.; Chutimanukul, P. Assessing Light Spectrum Impact on Growth and Antioxidant Properties of Basil Family Microgreens. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 27875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borbély, P.; Gasperl, A.; Pálmai, T.; Ahres, M.; Asghar, M.A.; Galiba, G.; Müller, M.; Kocsy, G. Light Intensity- and Spectrum-Dependent Redox Regulation of Plant Metabolism. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugasi, A.; Hóvári, J. Antioxidant Properties of Commercial Alcoholic and Nonalcoholic Beverages. Nahrung/Food 2003, 47, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marie, A.; Hortresearch, C.; Stephens, M.J.; Hall, H.K.; Alspach, P.A. Variation and Heritabilities of Antioxidant Activity and Total Phenolic Content Estimated from a Red Raspberry Factorial Experiment; 2005; Vol. 130;

- Cárdeno, A.; Sánchez-Hidalgo, M.; Rosillo, M.A.; De La Lastra, C.A. Oleuropein, a Secoiridoid Derived from Olive Tree, Inhibits the Proliferation of Human Colorectal Cancer Cell through Downregulation of HIF-1α. Nutr Cancer 2013, 65, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benot-Dominguez, R.; Tupone, M.G.; Castelli, V.; d’Angelo, M.; Benedetti, E.; Quintiliani, M.; Cinque, B.; Forte, I.M.; Cifone, M.G.; Ippoliti, R.; et al. Olive Leaf Extract Impairs Mitochondria by Pro-Oxidant Activity in MDA-MB-231 and OVCAR-3 Cancer Cells. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy 2021, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, D.; Shin, S.H.; Bae, J.S. Natural Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Compounds in Foodstuff or Medicinal Herbs Inducing Heme Oxygenase-1 Expression. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacifico, S.; Bláha, P.; Faramarzi, S.; Fede, F.; Michaličková, K.; Piccolella, S.; Ricciardi, V.; Manti, L. Differential Radiomodulating Action of Olea Europaea L. Cv. Caiazzana Leaf Extract on Human Normal and Cancer Cells: A Joint Chemical and Radiobiological Approach. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasbinder, A.; Cheng, R.K.; Heckbert, S.R.; Thompson, H.; Zaslavksy, O.; Chlebowski, R.T.; Shadyab, A.H.; Johnson, L.; Wactawski-Wende, J.; Wells, G.; et al. Chronic Oxidative Stress as a Marker of Long-Term Radiation-Induced Cardiovascular Outcomes in Breast Cancer. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 2023, 16, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiyaveettil, D.; Joseph, D.; Malik, M. Cardiotoxicity in Breast Cancer Treatment: Causes and Mitigation. Cancer Treat Res Commun 2023, 37, 100760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P. How Mitochondria Produce Reactive Oxygen Species. Biochemical Journal 2009, 417, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manti, L.; Durante, M.; Cirrone, G.; Grossi, G.; Lattuada, M.; Pugliese, M.; Sabini, M.; Scampoli, P.; Valastro, L.; Gialanella, G. Modelled Microgravity Does Not Modify the Yield of Chromosome Aberrations Induced by High-Energy Protons in Human Lymphocytes. Int J Radiat Biol 2005, 81, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manti, L. Does Reduced Gravity Alter Cellular Response to Ionizing Radiation? Radiat Environ Biophys 2006, 45, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertucci, A.; Durante, M.; Gialanella, G.; Grossi, G.; Manti, L.; Pugliese, M.; Scampoli, P.; Mancusi, D.; Sihver, L.; Rusek, A. Shielding of Relativistic Protons. Radiat Environ Biophys 2007, 46, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sishc, B.J.; Zawaski, J.; Saha, J.; Carnell, L.S.; Fabre, K.M.; Elgart, S.R. The Need for Biological Countermeasures to Mitigate the Risk of Space Radiation-Induced Carcinogenesis, Cardiovascular Disease, and Central Nervous System Deficiencies. Life Sci Space Res (Amst) 2022, 35, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S. The Effects of Microgravity and Space Radiation on Cardiovascular Health: From Low-Earth Orbit and Beyond. IJC Heart & Vasculature 2020, 30, 100595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).