Submitted:

03 August 2024

Posted:

05 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Antioxidant Capacity in Response to Supplemental UV-B or UV-C Light

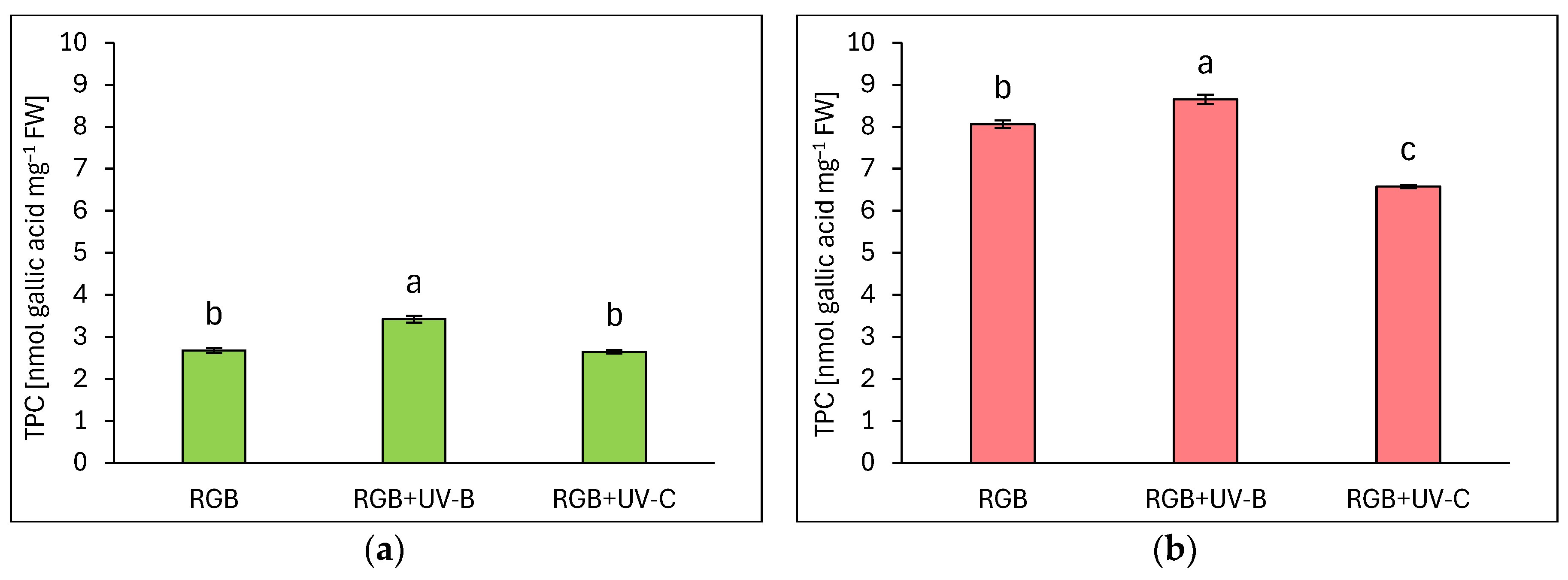

2.1.1. Total Phenolic Content

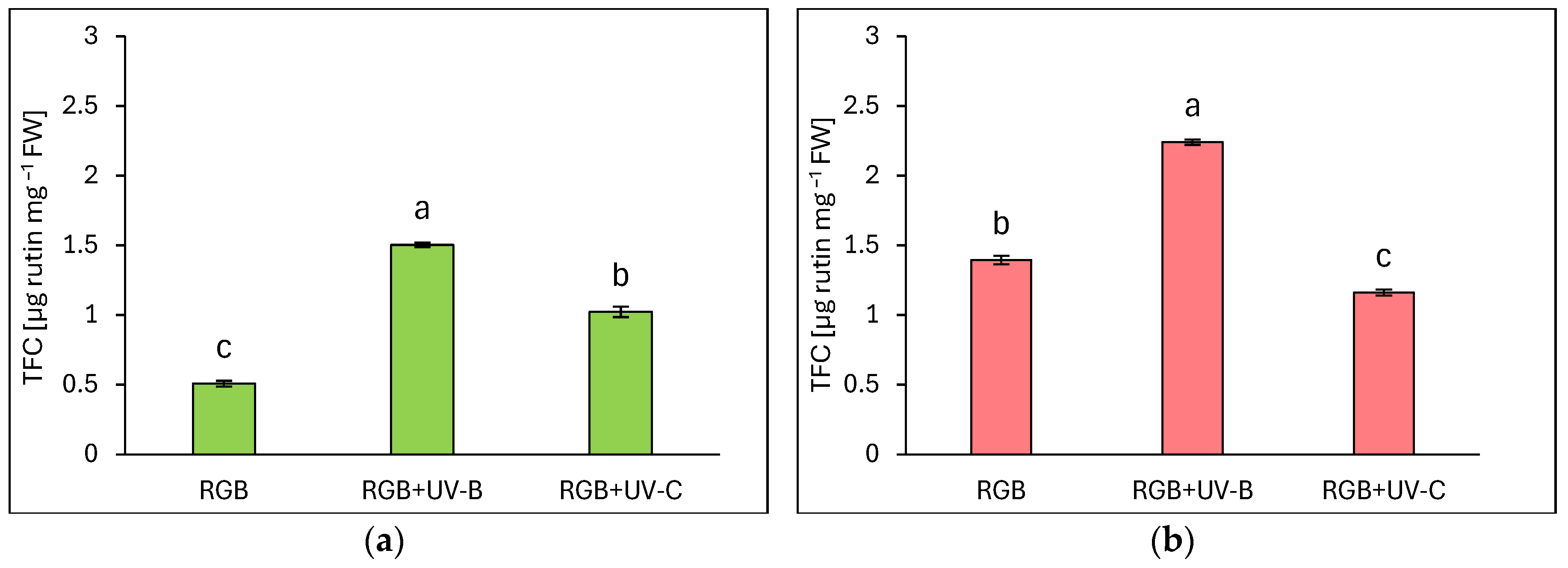

2.1.2. Total Flavonoid Content

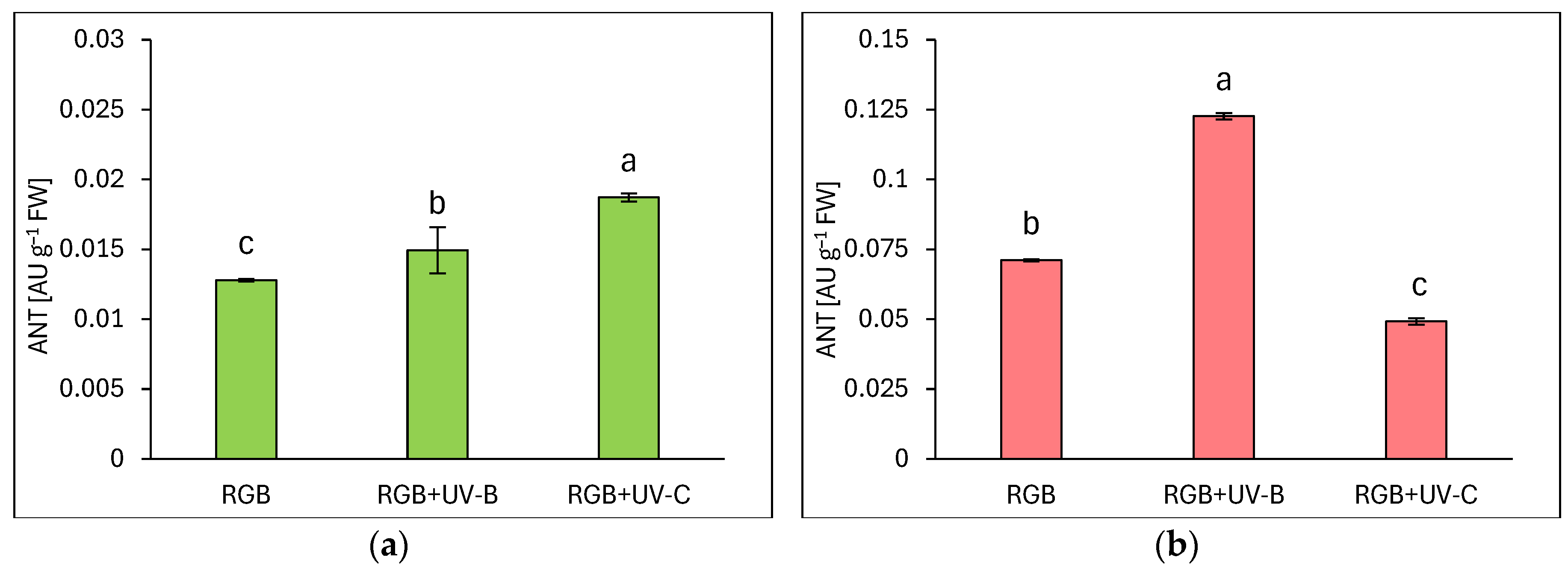

2.1.3. Anthocyanins Level

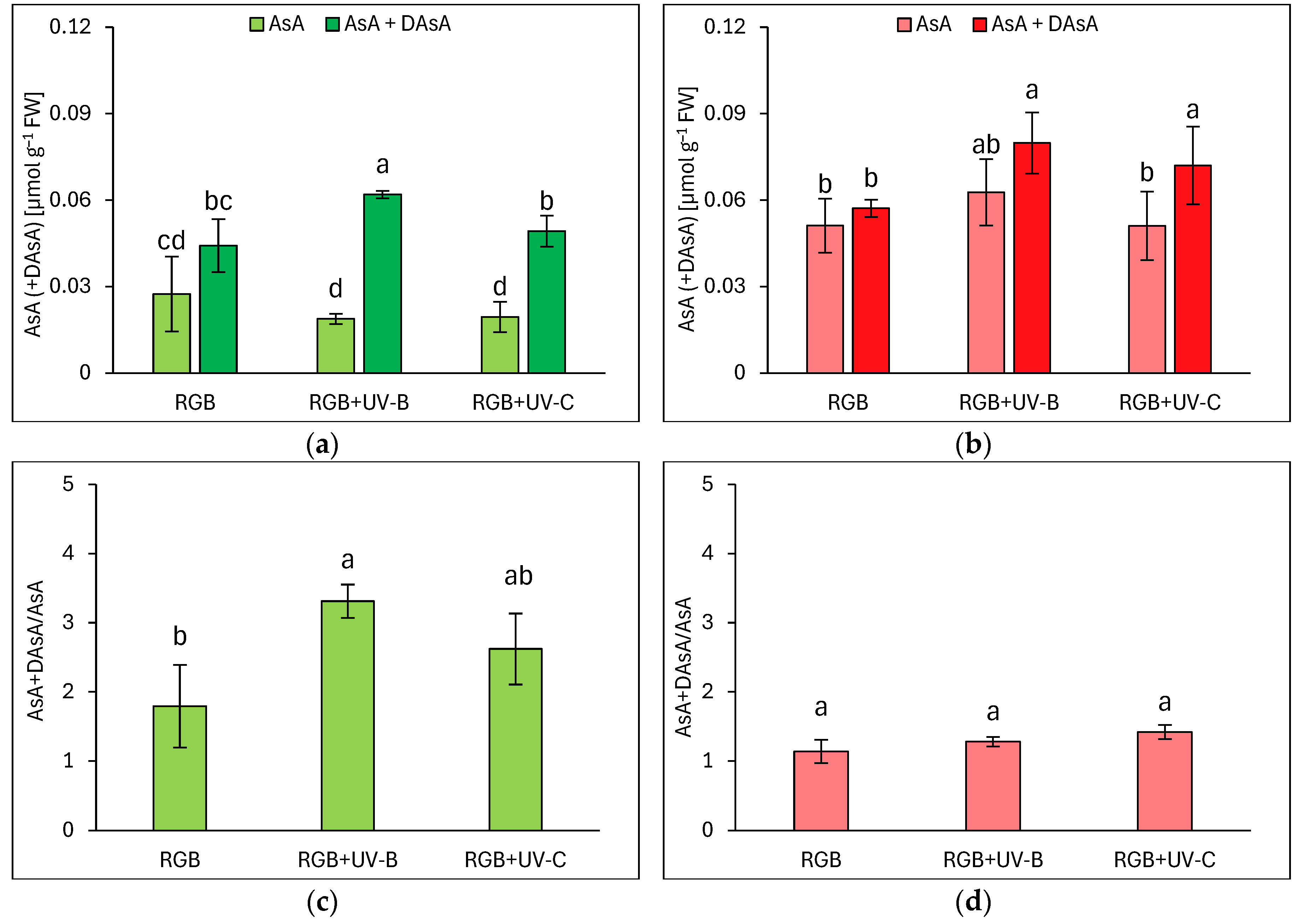

2.1.4. Ascorbic Acid Pool

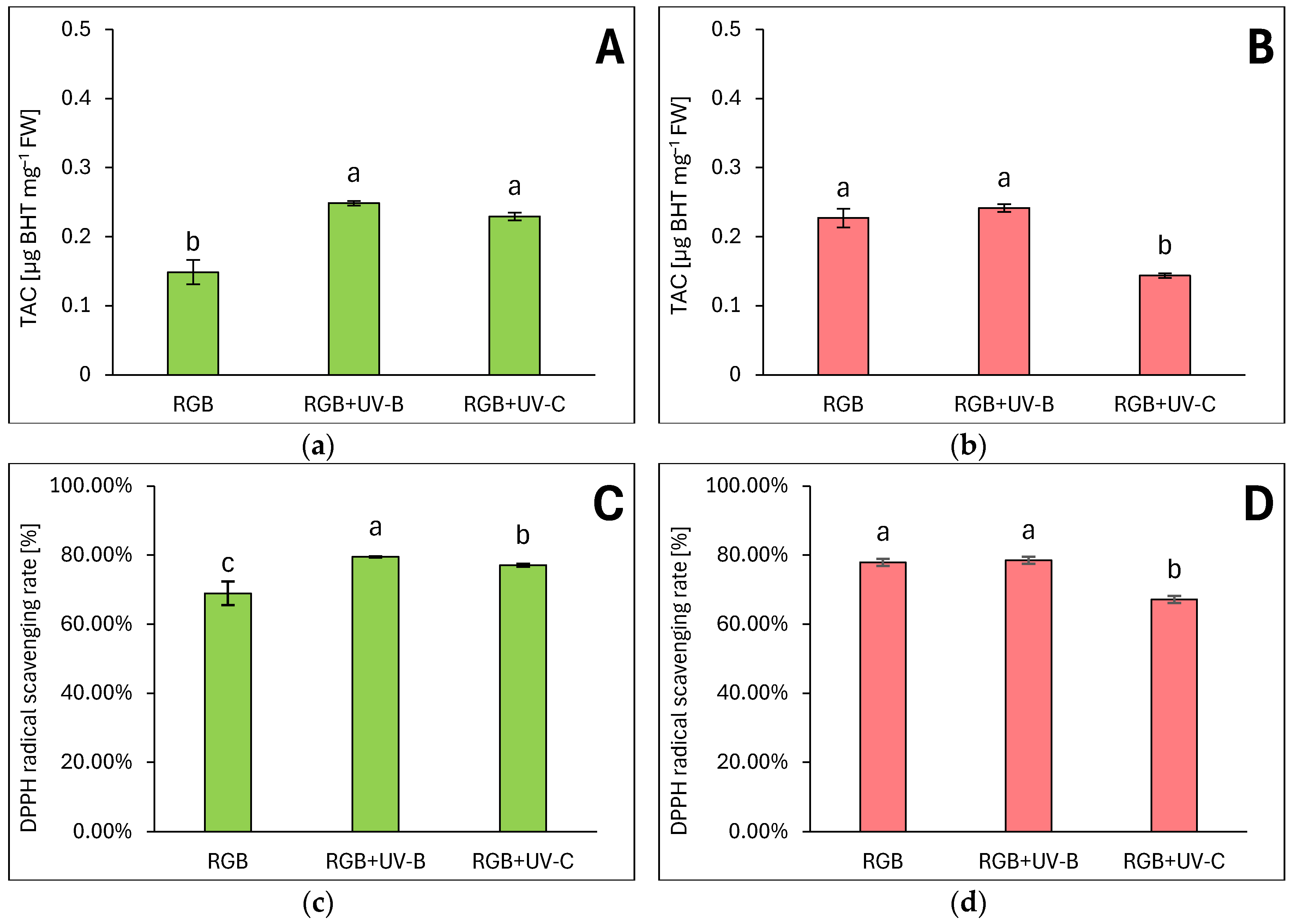

2.1.5. Overall Antioxidant Capacity

2.2. Photosynthetic Activity Under Short-Term Exposition to UV-B or UV-C Light

2.2.1. The effect of UV Light Supplementation on Photosynthetic Pigments and Soluble Leaf Protein Content

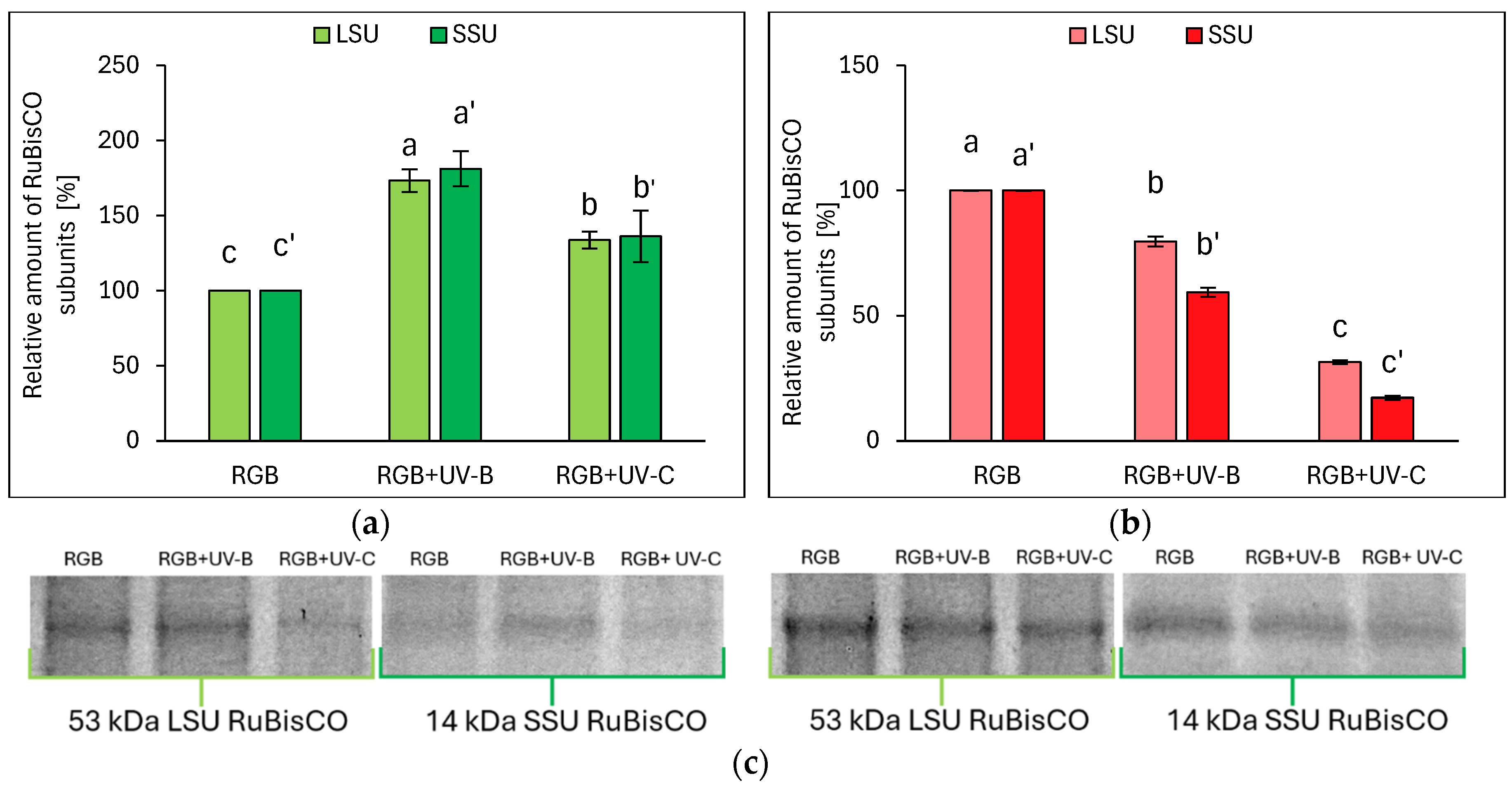

2.2.2. Influence of UV Light Supplementation on RuBisCO Abundance

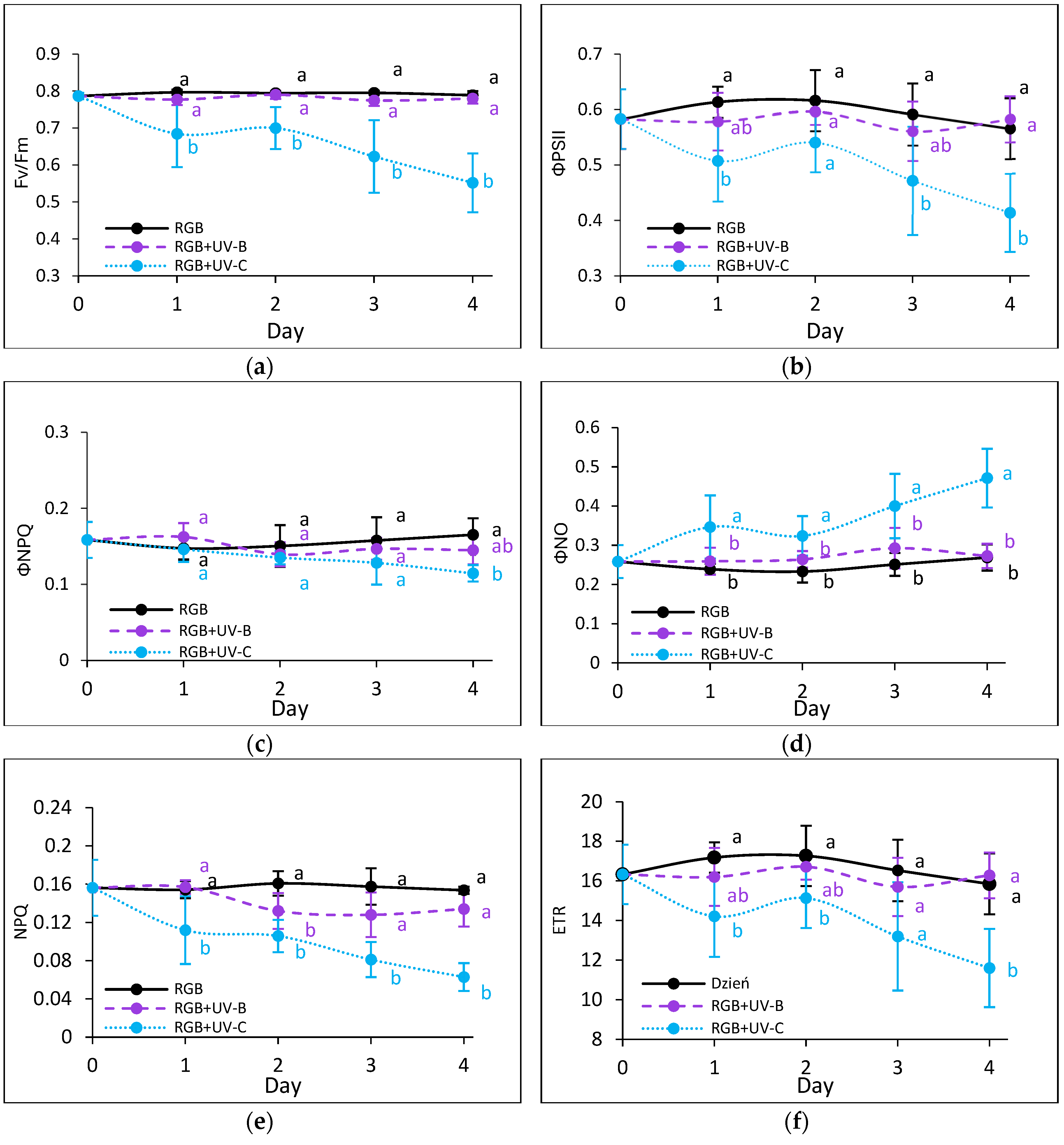

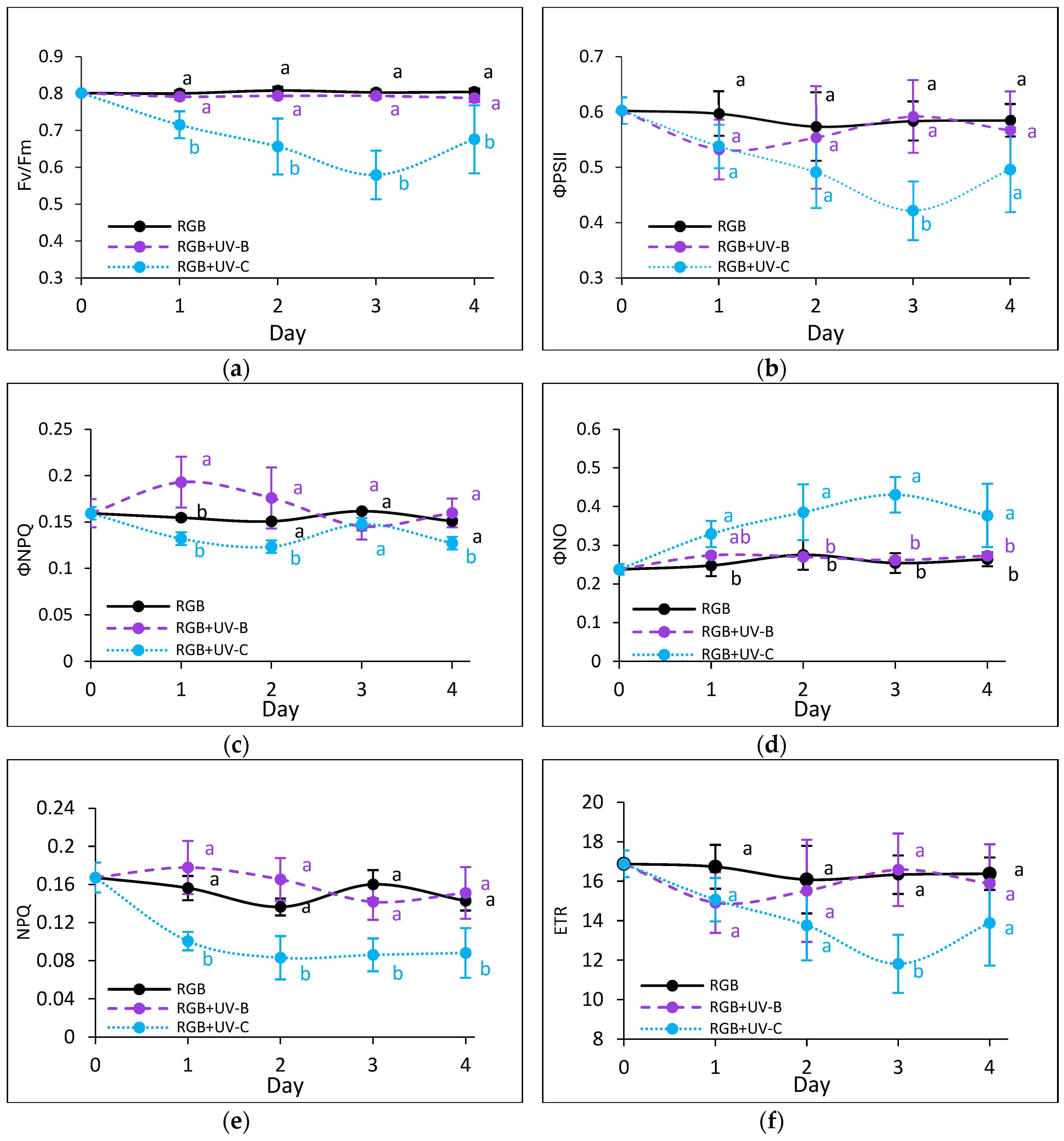

2.2.3. The effect of UV Light Supplementation on Subsequent Photosynthetic Efficiency of PSII

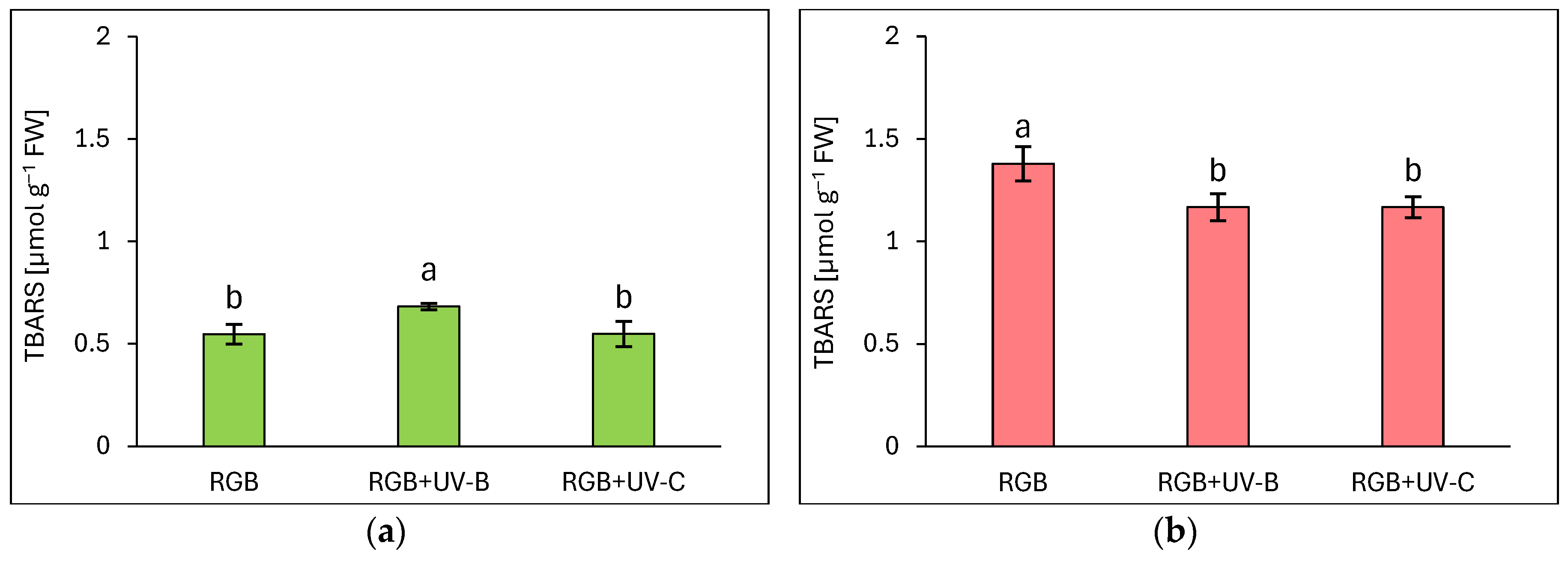

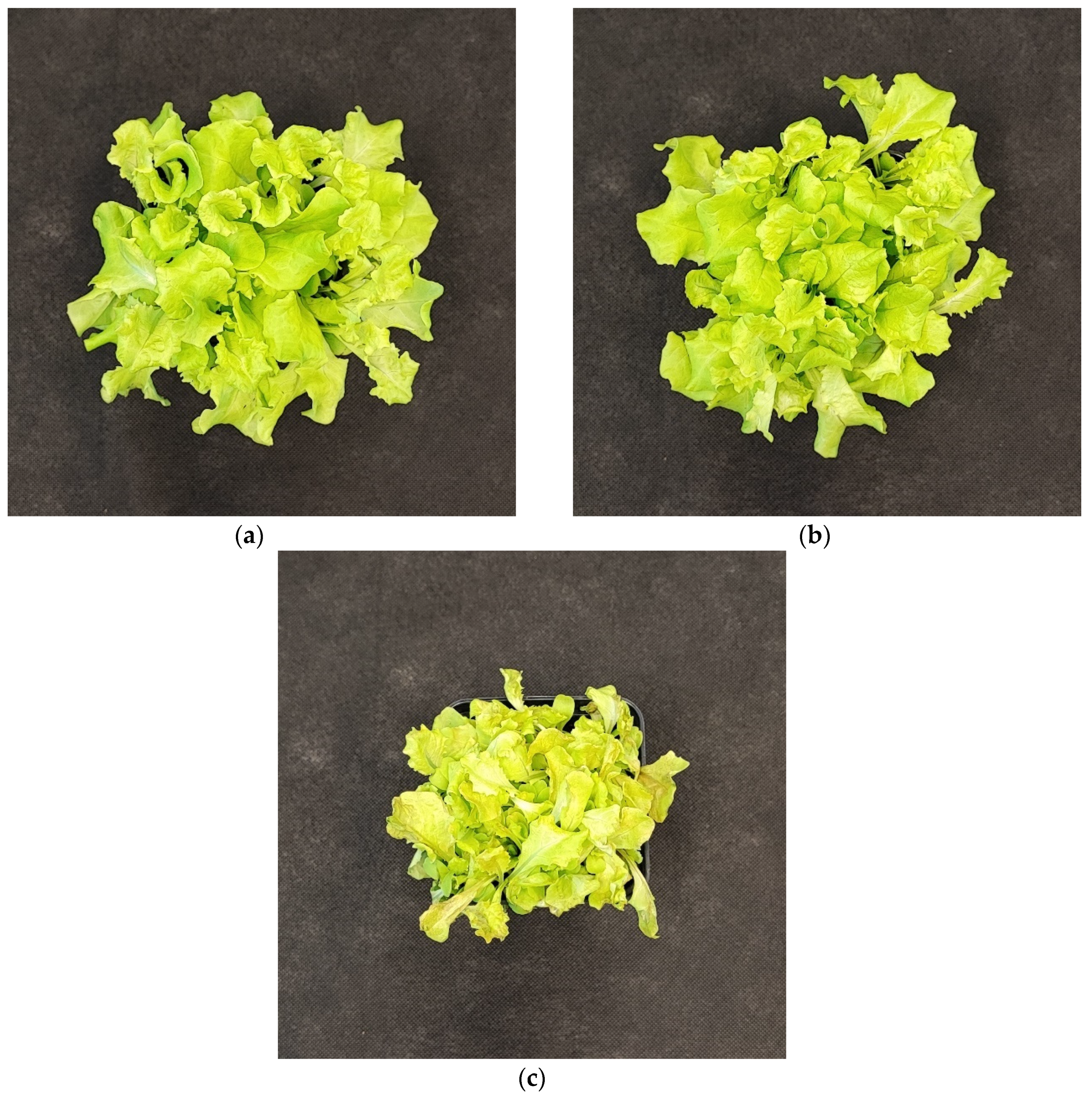

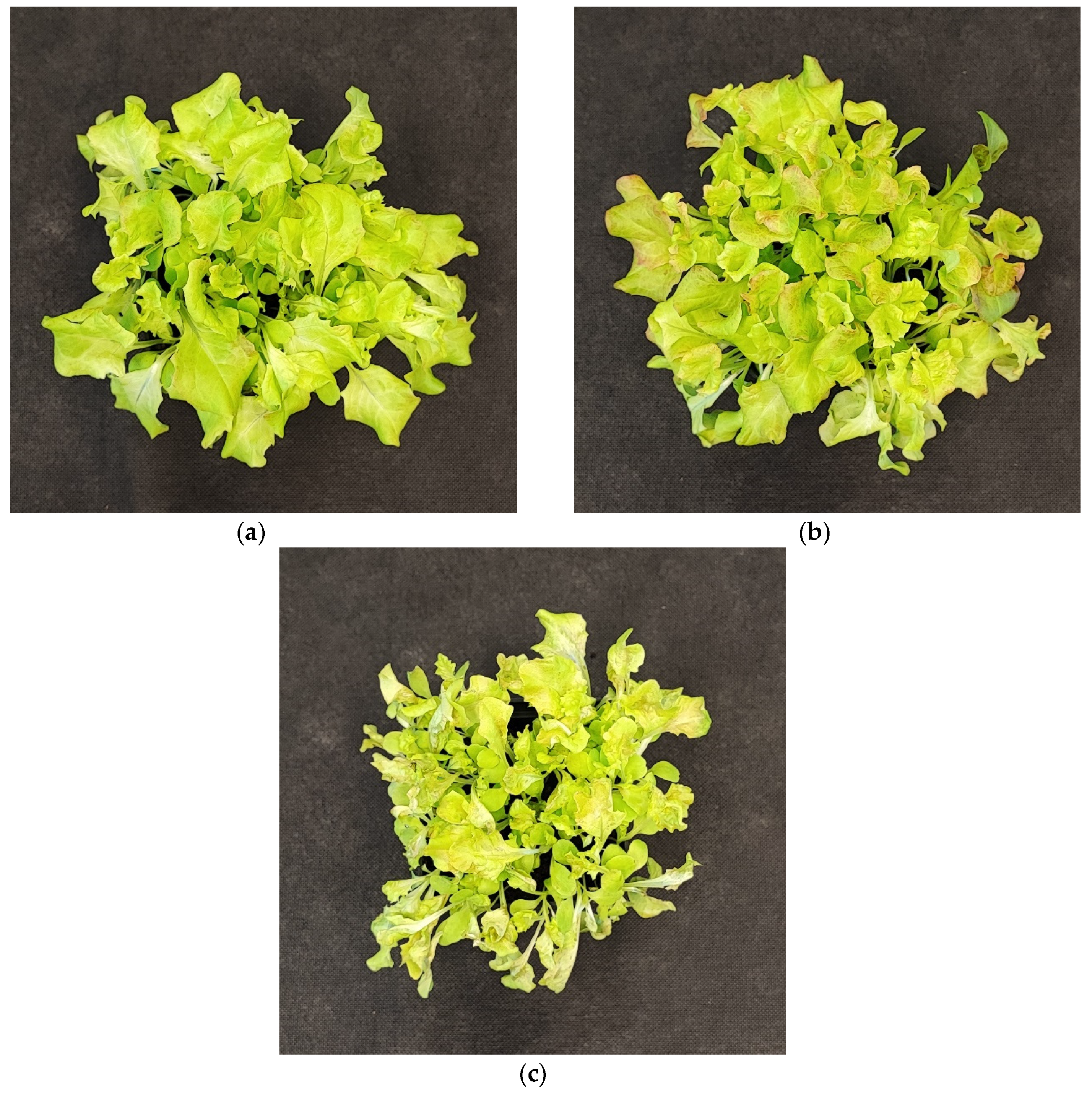

2.2.4. The Effect of UV Light Supplementation on Lipid Peroxidation Rate and Plant Morphology

3. Discussion

3.1. Efficiency of RGB Spectrum Supplementation With UV-B or UV-C Light on Antioxidant Capacity of Lettuce

3.2. Condition of Photosynthetic Apparatus in Response to UV-B or UV-C Supplementation to the RGB Spectrum

4. Materials and Methods

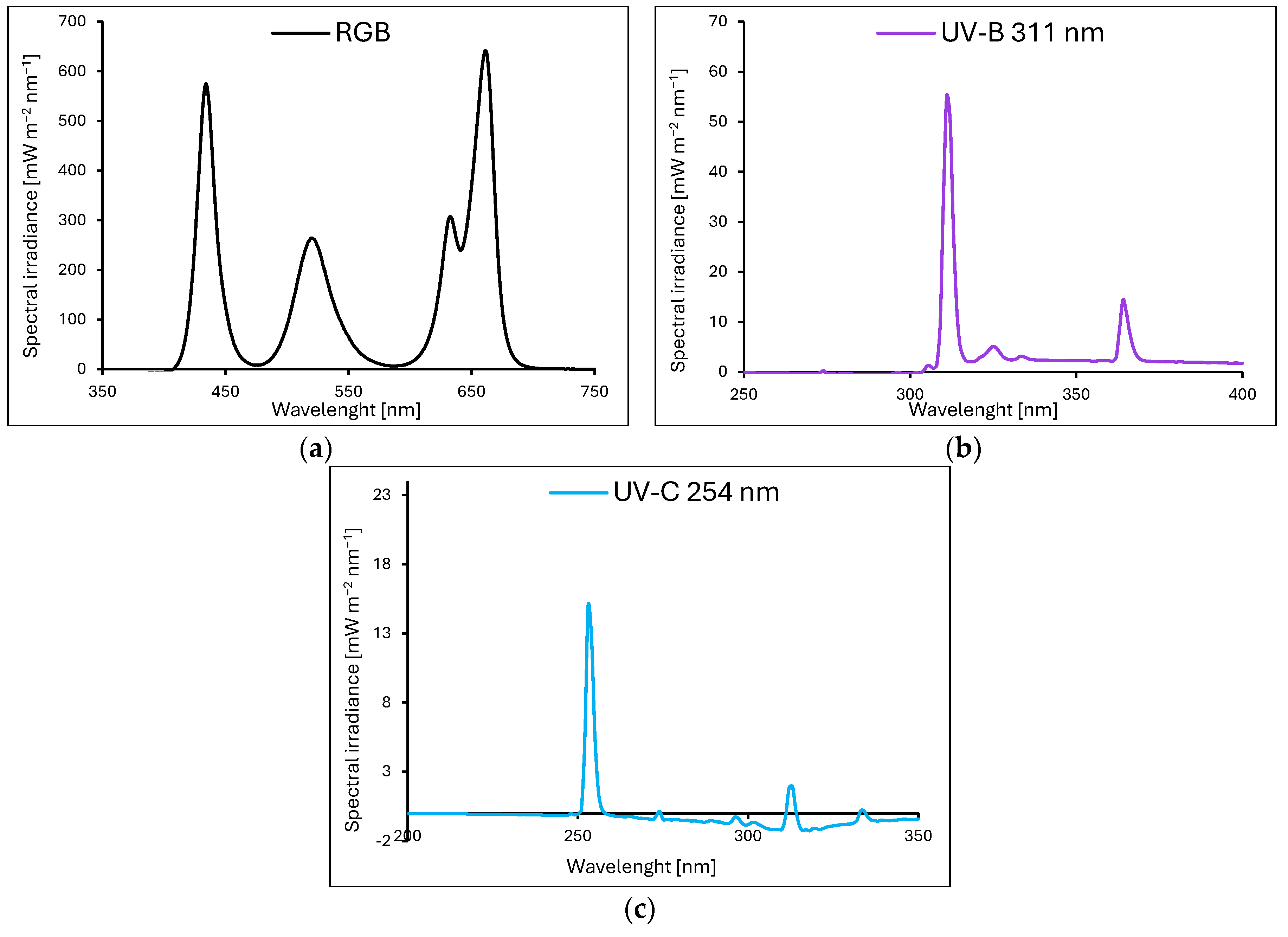

4.1. Plant Material, Growth Conditions and Light Treatment

4.2. Estimation of Total Phenolic Content with Folin–Ciocalteu Assay

4.3. Estimation of Total Flavonoid Content

4.4. The Ascorbate/Dehydroascorbate (AsA/DAsA) Ratio Estimation

4.5. Anthocyanins Assay

4.6. Antioxidant Activity by DPPH Assay

4.7. Photosynthetic Pigments Determination

4.8. Leaf Soluble Protein Level and Densitometric Analysis of RuBisCO Subunits

4.9. Measurement of Chlorophyll Fluorescence (ChF) Induction Kinetics

4.10. Measurement of Lipid Peroxidation Rate

4.11. Models for Data Fitting and Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ampim, P.A.; Obeng, E.; Olvera-Gonzalez, E. Indoor vegetable production: An alternative approach to increasing cultivation. Plants 2022, 11, 2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amitrano, C.; Chirico, G.B.; De Pascale, S.; Rouphael, Y.; De Micco, V. Crop management in controlled environment agriculture (CEA) systems using predictive mathematical models. Sensors 2020, 20, 3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnauer, C.; Pichler, H.; Schmittner, C.; Tauber, M.; Christl, K.; Knapitsch, J.; Parapatits, M. A recommendation for suitable technologies for an indoor farming framework. Elektrotech. Informationstechnik 2020, 137, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojak, M.; Skowron, E. Light quality-dependent regulation of non-photochemical quenching in tomato plants. Biology 2021, 10, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surjadinata, B.B.; Jacobo-Velázquez, D.A.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L. UVA, UVB and UVC light enhances the biosynthesis of phenolic antioxidants in fresh-cut carrot through a synergistic effect with wounding. Molecules 2017, 22, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazaityte, A.; Virsile, A.; Jankauskiene, J.; Sakalauskiene, S.; Samuoliene, G.; Sirtautas, R.; Novičkovas, A.; Dabašinskas, L.; Miliauskienė, J.; Vaštakaitė, V.; Bagdonavičienė, A.; Duchovskis, P. Effect of supplemental UV-A irradiation in solid-state lighting on the growth and phytochemical content of microgreens. Int. Agrophys. 2015, 29, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yu, L.; Liu, L.; Yang, A.; Huang, X.; Zhu, A.; Zhou, H. Effects of ultraviolet-B radiation on the regulation of ascorbic acid accumulation and metabolism in lettuce. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takshak, S.; Agrawal, S.B. Defense potential of secondary metabolites in medicinal plants under UV-B stress. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2019, 193, 51–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darré, M.; Vicente, A.R.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Artés-Hernández, F. Postharvest ultraviolet radiation in fruit and vegetables: Applications and factors modulating its efficacy on bioactive compounds and microbial growth. Foods 2022, 11, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico-Damião, V.; Carvalho, R.F. Cryptochrome-related abiotic stress responses in plants. Front. Plant. Sci. 2018, 9, 431291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artés-Hernández, F.; Castillejo, N.; Martínez-Zamora, L. UV and visible spectrum led lighting as abiotic elicitors of bioactive compounds in sprouts, microgreens, and baby leaves—A comprehensive review including their mode of action. Foods 2022, 11, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanhaelewyn, L.; Van Der Straeten, D.; De Coninck, B.; Vandenbussche, F. Ultraviolet radiation from a plant perspective: The plant-microorganism context. Front. Plant. Sci. 2020, 11, 597642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreyra, M.L.F.; Serra, P.; Casati, P. Recent advances on the roles of flavonoids as plant protective molecules after UV and high light exposure. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 173, 736–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Chu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Bian, Y.; Xiao, J.; Xu, D. HY5: A pivotal regulator of light-dependent development in higher plants. Front. Plant. Sci. 2022, 12, 800989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, E.; Hayashi, K.; Furuyama, S.; Hikosaka, S.; Ishigami, Y. Effect of UV light on phytochemical accumulation and expression of anthocyanin biosynthesis genes in red leaf lettuce. Acta Hortic. 2016, 1134, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobo-Velázquez, D.A.; Moreira-Rodríguez, M.; Benavides, J. UVA and UVB radiation as innovative tools to biofortify horticultural crops with nutraceuticals. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, E.S. Induction of secondary metabolite production by UV-C radiation in Vitis vinifera L. Öküzgözü callus cultures. Biol. Res. 2014, 47, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, T.K.O.; Fabi, J.P. Valorization of polyphenolic compounds from food industry by-products for application in polysaccharide-based nanoparticles. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1144677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiland, M.; Weßler, C.F.; Filler, T.; Glaab, J.; Lobo Ploch, N.; Winterwerber, U. , Wiesner-Reinhold, M.; Schreiner, M.; Neugart, S. A comparison of consistent UV treatment versus inconsistent UV treatment in horticultural production of lettuce. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2023, 22, 1611–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacak, I.; Trojak, M.; Skowron, E. The use of UV-A radiation for biofortification of lettuce and basil plants with antioxidant phenolic and flavonoid compounds. Folia Biol. Oecol. 2024, 18, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Son, J.E.; Oh, M.M. Growth and phenolic compounds of Lactuca sativa L. grown in a closed-type plant production system with UV-A,-B, or-C lamp. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014; 94, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addison, R.; Weatherhead, S.C.; Pawitri, A.; Smith, G.R.; Rider, A.; Grantham, H.J.; Cockell, S.J.; Reynolds, N.J. Therapeutic wavelengths of ultraviolet B radiation activate apoptotic, circadian rhythm, redox signalling and key canonical pathways in psoriatic epidermis. Redox Biol. 2021, 41, 101924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.E.; Teo, Z.W.N.; Shen, L.; Yu, H. Seeing the lights for leafy greens in indoor vertical farming. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 106, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, A.A.O.; Pérez-Gálvez, A. Carotenoids as a Source of Antioxidants in the Diet. In Carotenoids in Nature; Stange, C., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 79, pp. 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, C.R.; Britz, S.J. Effect of supplemental ultraviolet radiation on the carotenoid and chlorophyll composition of green house-grown leaf lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) cultivars. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006; 19, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milić Komić, S.; Živanović, B.; Dumanović, J.; Kolarž, P.; Sedlarević Zorić, A.; Morina, F.; Vidocić, M.; Veljović Jovanović, S. Differential antioxidant response to supplemental UV-B irradiation and sunlight in three basil varieties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otake, M.; Okamoto Yoshiyama, K.; Yamaguchi, H.; Hidema, J. 222 nm ultraviolet radiation C causes more severe damage to guard cells and epidermal cells of Arabidopsis plants than does 254 nm ultraviolet radiation. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2021, 20, 1675–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claus, H. Ozone generation by ultraviolet lamps. Photochem. Photobiol. 2021, 97, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Mina, U. Ozone stress responsive gene database (OSRGD ver. 1.1): A literature curated database for insight into plants’ response to ozone stress. Plant Gene 2022, 31, 100368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillejo, N.; Martínez-Zamora, L.; Artés-Hernández, F. Postharvest UV radiation enhanced biosynthesis of flavonoids and carotenes in bell peppers. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 184, 111774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás-Callejas, A.; Otón, M.; Artés, F.; Artés-Hernández, F. Combined effect of UV-C pretreatment and high oxygen packaging for keeping the quality of fresh-cut Tatsoi baby leaves. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2012, 14, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabelo, M.C.; Bang, W.Y.; Nair, V.; Alves, R.E.; Jacobo-Velázquez, D.A.; Sreedharan, S.; Alcântara de Miranda, M.R.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L. UVC light modulates vitamin C and phenolic biosynthesis in acerola fruit: Role of increased mitochondria activity and ROS production. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vass, I.; Szilárd, A.; Sicora, C. Adverse effects of UV-B light on the structure and function of the photosynthetic apparatus In Handbook of Photosynthesis, 2nd ed.; Pessarakli, M., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; pp. 827–843. [Google Scholar]

- Štroch, M.; Materová, Z.; Vrábl, D.; Karlický, V.; Šigut, L.; Nezval, J.; Špunda, V. Protective effect of UV-A radiation during acclimation of the photosynthetic apparatus to UV-B treatment. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 96, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataria, S.; Jajoo, A.; Guruprasad, K.N. Impact of increasing Ultraviolet-B (UV-B) radiation on photosynthetic processes. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2014, 137, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovanić, B.R.; Radenković, B.; Despotović-Zrakić, M.; Bogdanović, Z.; Barać, D. Effect of UV-B radiation on chlorophyll fluorescence, photosynthetic activity and relative chlorophyll content of five different corn hybrids. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 2022, 10, 100115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosobryukhov, A.; Khudyakova, A.; Kreslavski, V. Impact of UV radiation on photosynthetic apparatus: Adaptive and damaging mechanisms. In Plant Ecophysiology and Adaptation under Climate Change: Mechanisms and Perspectives I.; Spinger: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 555–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, L.; Charles, F.; de Miranda, M.R.A.; Aarrouf, J. Understanding the physiological effects of UV-C light and exploiting its agronomic potential before and after harvest. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 105, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusaczonek, A.; Czarnocka, W.; Willems, P.; Sujkowska-Rybkowska, M.; Van Breusegem, F.; Karpiński, S. Phototropin 1 and 2 influence photosynthesis, UV-C induced photooxidative stress responses, and cell death. Cells 2021, 10, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Gu, Y.; Liu, S.; Jiang, L.; Han, M.; Geng, D. Flavonoids metabolism and physiological response to ultraviolet treatments in Tetrastigma hemsleyanum Diels et Gilg. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 926197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bijlsma, J.; de Bruijn, W.J.; Velikov, K.P.; Vincken, J.P. Unravelling discolouration caused by iron-flavonoid interactions: Complexation, oxidation, and formation of networks. Food Chem. 2022, 370, 131292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrikova, A.G.; Krasteva, V.; Apostolova, E.L. Damage and protection of the photosynthetic apparatus from UV-B radiation. I. Effect of ascorbate. J. Plant Physiol. 2013, 170, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Romero, D.; Guillén, F.; Pérez-Aguilar, H.; Castillo, S.; Serrano, M.; Zapata, P.J.; Valero, D. Is it possible to increase the aloin content of Aloe vera by the use of ultraviolet light? J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 2165–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainsworth, E.A.; Gillespie, K.M. Estimation of total phenolic content and other oxidation substrates in plant tissues using Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 875–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shraim, A.M.; Ahmed, T.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Hijji, Y.M. Determination of total flavonoid content by aluminum chloride assay: A critical evaluation. LWT 2021, 150, 111932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampfenkel, K.; Vanmontagu, M.; Inzé, D. Extraction and determination of ascorbate and dehydroascorbate from plant tissue. Anal. Biochem. 1995, 225, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laby, R.J.; Kincaid, M.S.; Kim, D.; Gibson, S.I. The Arabidopsis sugar-insensitive mutants sis4 and sis5 are defective in abscisic acid synthesis and response. Plant J. 2000, 23, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehmood, A.; Javid, S.; Khan, M.F.; Ahmad, K.S.; Mustafa, A. In vitro total phenolics, total flavonoids, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of selected medicinal plants using different solvent systems. BMC Chem. 2022, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellburn, A.R. The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. J. Plant Physiol. 1994, 144, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsugama, D.; Liu, S.; Takano, T. A rapid chemical method for lysing Arabidopsis cells for protein analysis. Plant Methods 2011, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skowron, E.; Trojak, M. Effect of exogenously-applied abscisic acid, putrescine and hydrogen peroxide on drought tolerance of barley. Biologia 2021, 76, 453–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, D.M.; DeLong, J.M.; Forney, C.F.; Prange, R.K. Improving the thiobarbituric acid-reactive-substances assay for estimating lipid peroxidation in plant tissues containing anthocyanin and other interfering compounds. Planta 1999, 207, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| RGB | RGB+UV-B | RGB+UV-C | |

| Chlorophyll a+b [mg g–1 FW] |

0.839 ± 0.013a | 0.764 ± 0.003b | 0.323 ± 0.002c |

| Chlorophyll a [mg g–1 FW] |

0.601 ± 0.010a | 0.547 ± 0.002b | 0.205 ± 0.001c |

| Chlorophyll b [mg g–1 FW] |

0.238 ± 0.003a | 0.217 ± 0.001b | 0.117 ± 0.001c |

| Chlorophyll a/b | 2.521 ± 0.016a | 2.520 ± 0.002a | 1.748 ± 0.010b |

| Carotenoids [mg g–1 FW] |

0.114 ± 0.002a | 0.112 ± 0.000a | 0.031 ± 0.000b |

| Chlorophyll a+b/ Carotenoids |

7.373 ± 0.031b | 6.807 ± 0.012c | 10.361 ± 0.069a |

| Soluble leaf proteins [mg g–1 FW] |

26.92 ± 0.15c | 42.89 ± 1.12a | 31.46 ± 0.57b |

| Parameter | Treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| RGB | RGB+UV-B | RGB+UV-C | |

| Chlorophyll a+b [mg g–1 FW] |

0.824 ± 0.004b | 0.836 ± 0.006a | 0.798 ± 0.008c |

| Chlorophyll a [mg g–1 FW] |

0.575 ± 0.003a | 0.520 ± 0.003c | 0.531 ± 0.004b |

| Chlorophyll b [mg g–1 FW] |

0.250 ± 0.002c | 0.316 ± 0.003a | 0.267 ± 0.004b |

| Chlorophyll a/b | 2.301 ± 0.011a | 1.645 ± 0.011c | 1.986 ± 0.018b |

| Carotenoids [mg g–1 FW] |

0.124 ± 0.001b | 0.141 ± 0.001a | 0.092 ± 0.000c |

| Chlorophyll a+b/ Carotenoids |

6.645 ± 0.042b | 5.936 ± 0.039c | 8.651 ± 0.088a |

| Soluble leaf proteins [mg g–1 FW] |

40.16 ± 0.15a | 39.70 ± 1.20a | 27.13 ± 1.72b |

| Treatment, wavelength peak (nm) | Daily time exposure (min), diurnal time | Total time (h) |

Total irradiance (W m–2) |

Irradiance (PAR) (W m–2) |

Cummulative dose (kJ m–2) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | |||||

| UV-B, 311 | 15 12.00-12.15 pm |

30 12.00-12.30 pm |

60 12.00-13.00 pm |

120 12.00-14.00 pm |

3.75 | 1.1572 | 0.253 | 15.622 |

| UV-C, 254 | 7,5 12.00-12.08 pm |

15 12.00-12.15 pm |

30 12.00-12.30 pm |

60 12.00-13.00 pm |

1.875 | 0.8901 | 0.177 | 6.008 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).