Submitted:

07 November 2025

Posted:

14 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Seed Material and Preparation

2.2. Metal Solution Preparation

2.3. Germination Test

2.4. Measurements and Calculations

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

| Dependent Variable | Type III Sum of Squares | Df | Mean Square | F | R squ | Adj R | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoot length | 8.908a | 11 | 0.81 | 42.077 | 0.975 | .952 | <.001 |

| Root length | 2.135b | 11 | 0.194 | 8.774 | 0.889 | .788 | <.001 |

| Control shoot | .020c | 11 | 0.002 | 0.269 | 0.198 | -.537 | 0.981 |

| Control root | .364d | 11 | 0.033 | 3.547 | 0.765 | .549 | 0.02 |

| GR | 43202.855e | 11 | 3927.532 | 15.577 | 0.935 | .875 | <.001 |

| GI | 2745.852f | 11 | 249.623 | 64.544 | 0.983 | .968 | <.001 |

| Control GI | .000g | 11 | 0 | . | . | . | . |

| MGT | 17707.499h | 11 | 1609.773 | 9.341 | 0.895 | .800 | <.001 |

| VI | 53378.983i | 11 | 4852.635 | 19.291 | 0.946 | .897 | <.001 |

| VI control | 8.456j | 11 | 0.769 | 0.269 | 0.198 | -.537 | 0.981 |

| RGI | 63817.521k | 11 | 5801.593 | 64.544 | 0.983 | .968 | <.001 |

| RVI | 168118.702l | 11 | 15283.52 | 20.738 | 0.95 | .904 | <.001 |

| RRL | 19310.838m | 11 | 1755.531 | 7.581 | 0.874 | .759 | <.001 |

| RSL | 12077.614n | 11 | 1097.965 | 47.636 | 0.978 | .957 | <.001 |

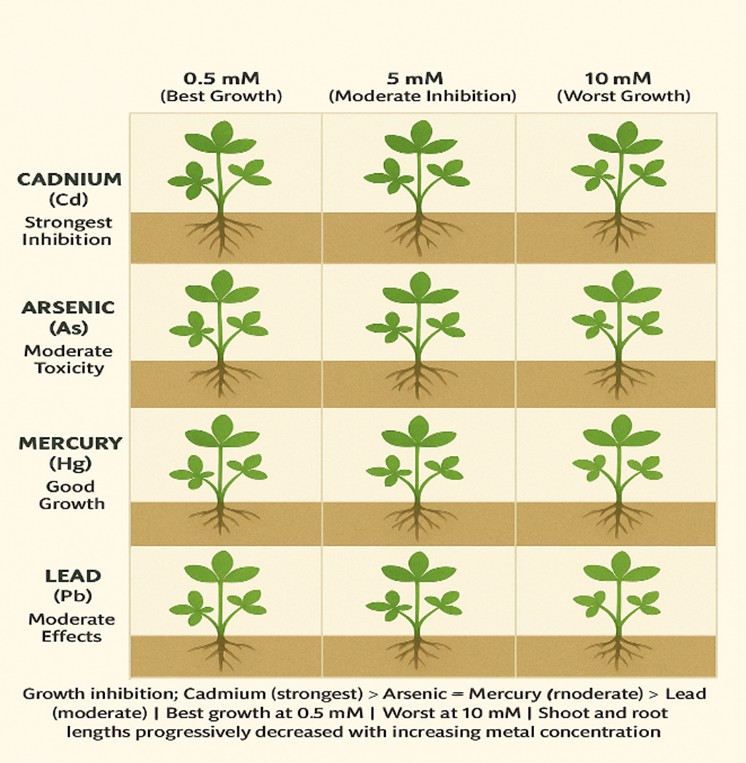

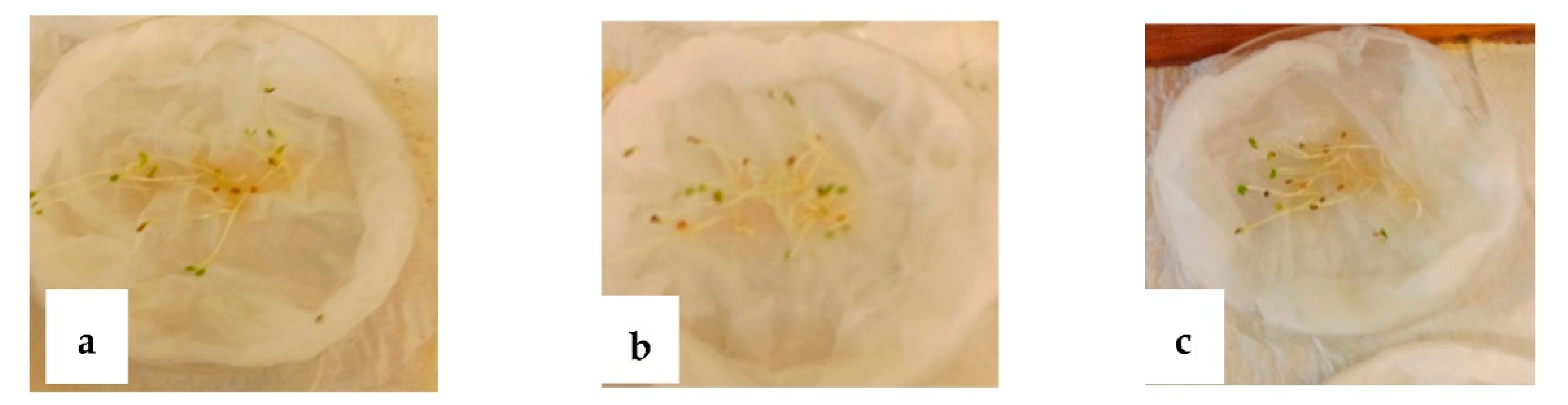

3.1. Effect of Metal Type on the Germination and Early Growth of Trifolium Repens L

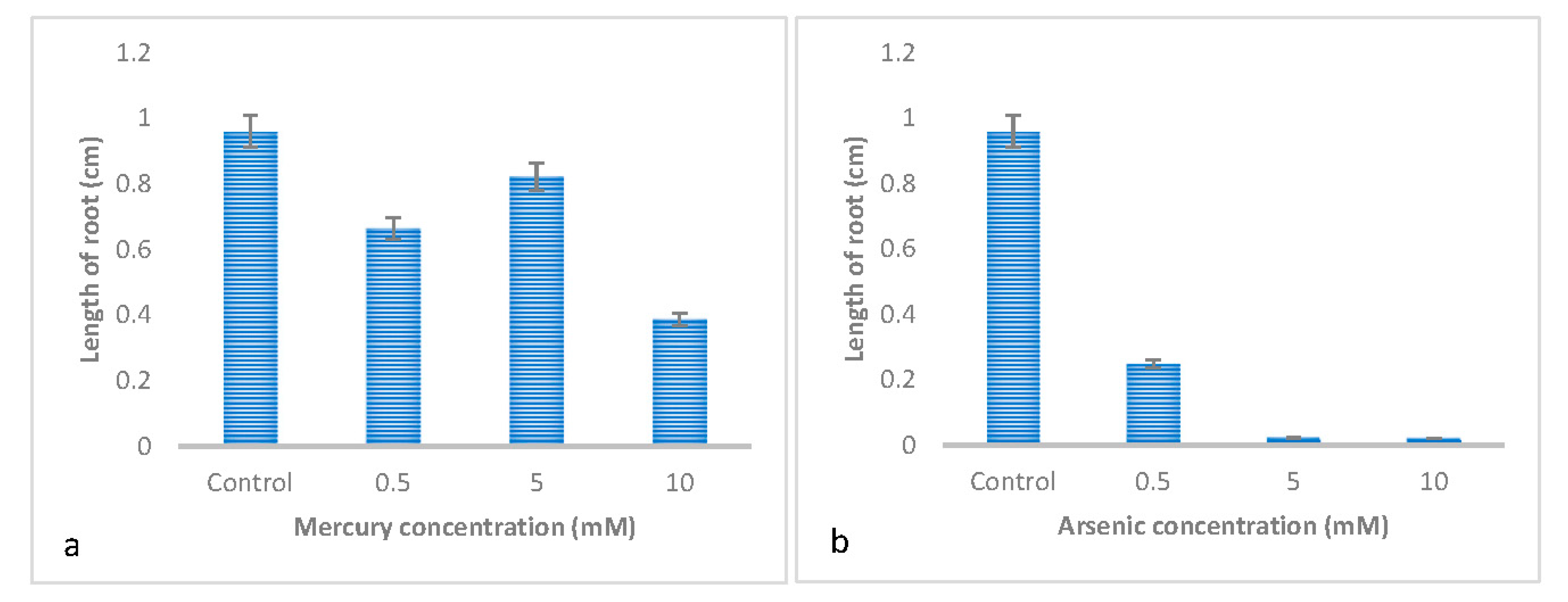

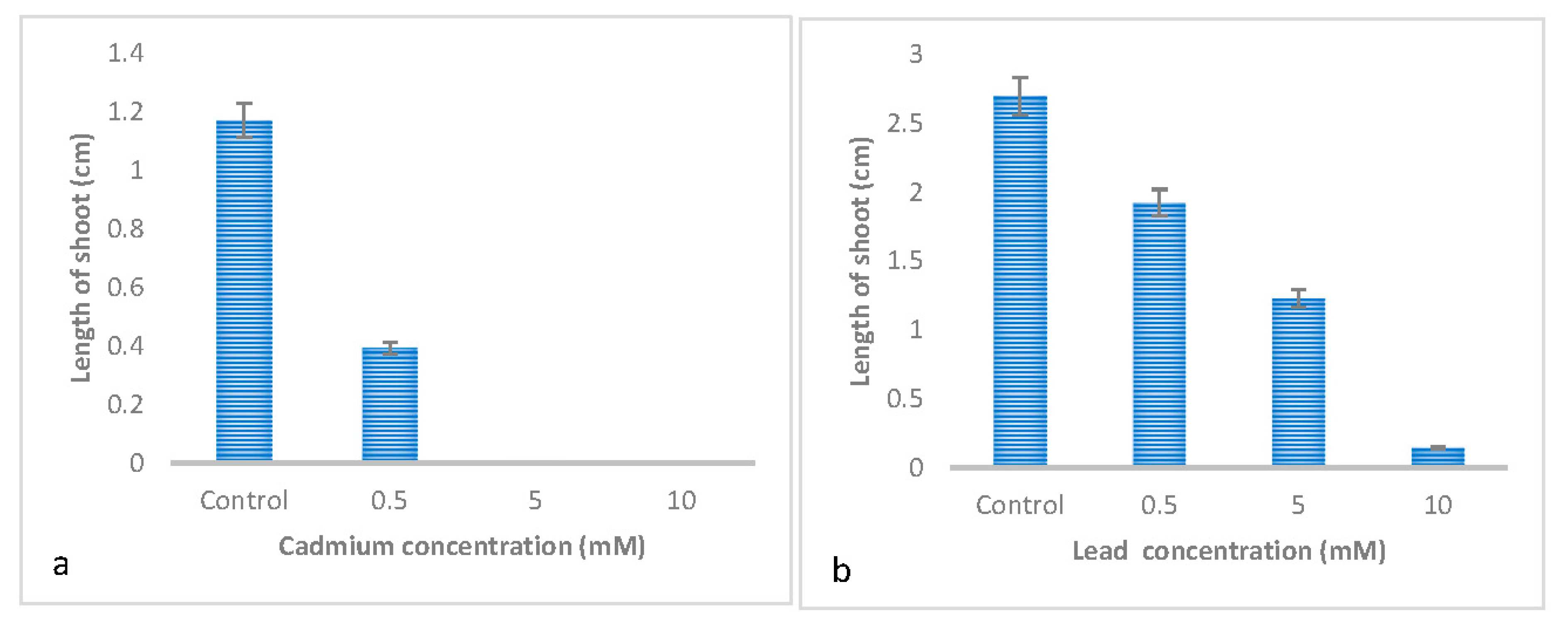

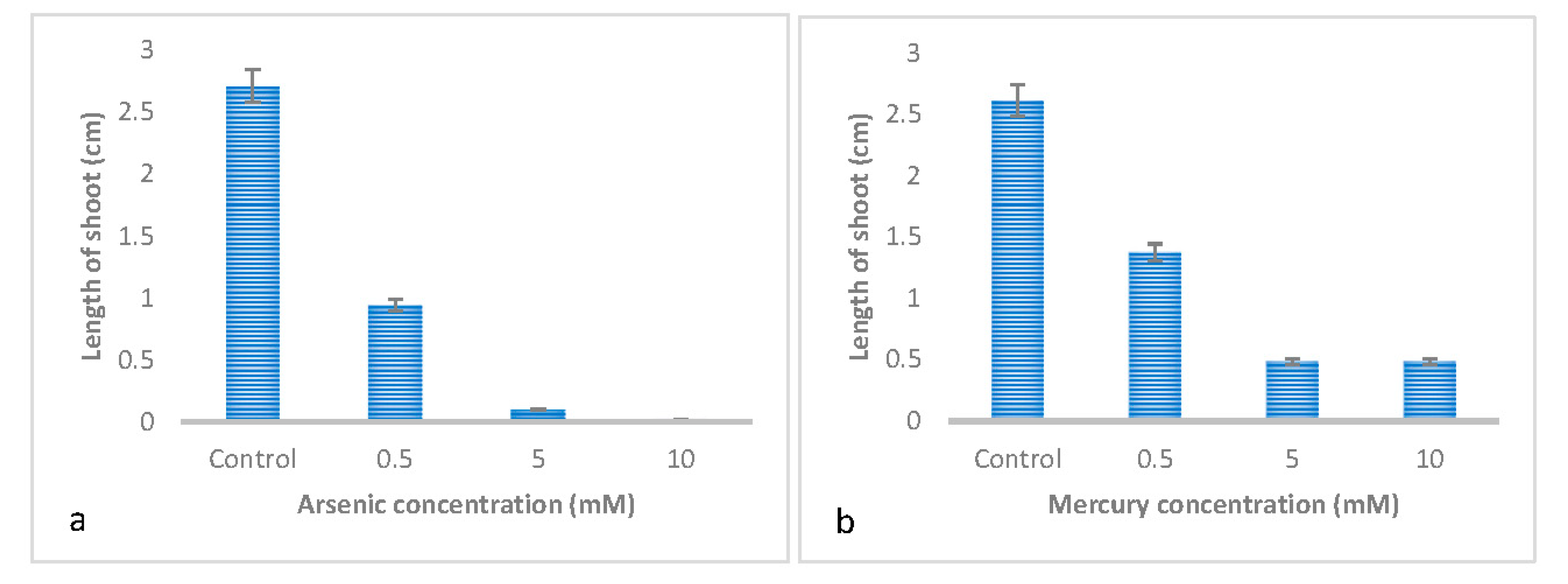

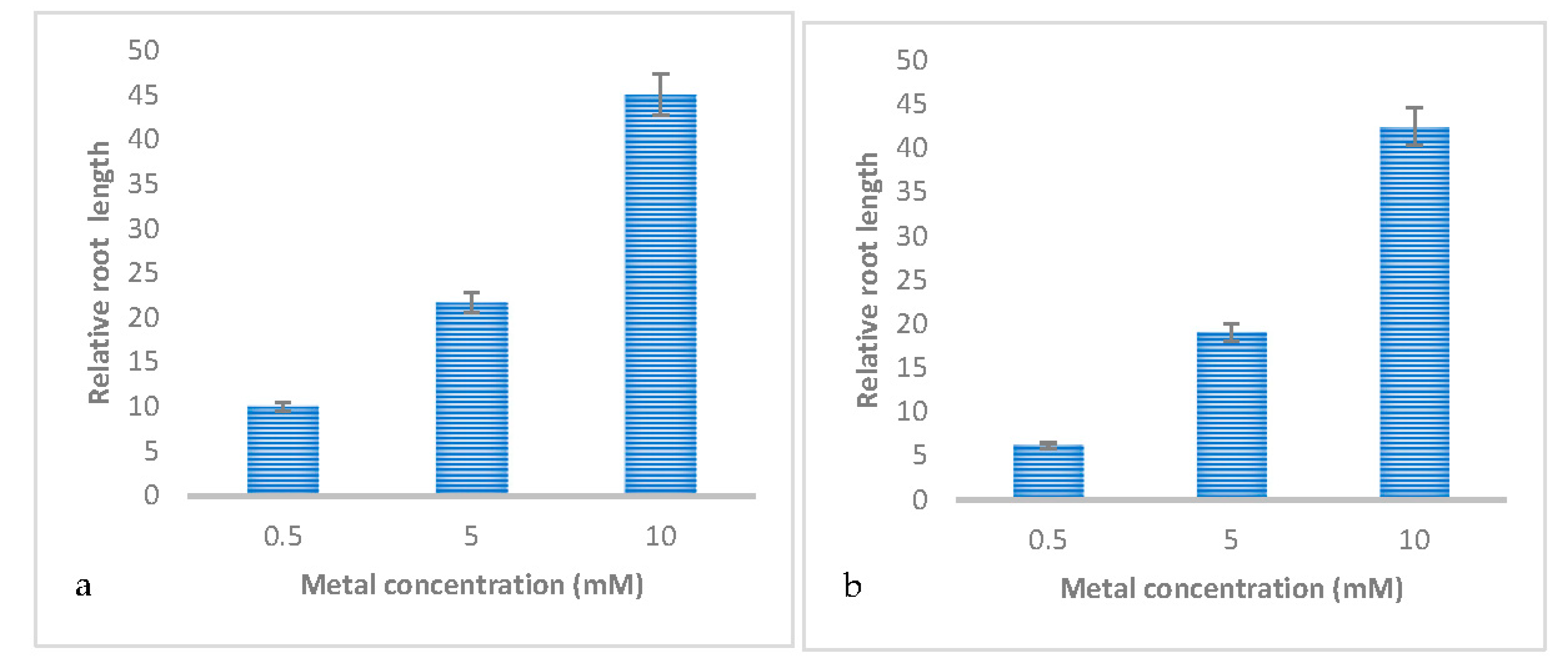

3.2. Effect of Metal Concentrations on the Germination and Early Growth of Trifolium Repens L

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

AppendixA

References

- Müller, F.; Masemola, L.; Britz, E.; Ngcobo, N.; Modiba, S.; Cyster, L.; Samuels, I.; Cupido, C.; Raitt, L. (2022). Seed germination and early seedling growth responses to drought stress in annual Medicago L. and Trifolium L. forages. Agronomy, 12(12), 2960. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12122960. [CrossRef]

- Ertekin, E.N.; Ertekin, İ.; Bilgen, M. (2020). Effects of some heavy metals on germination and seedling growth of sorghum. KSÜ Tarım ve Doğa Dergisi, 23(3), 1608–1615. [CrossRef]

- Kalinhoff C, Calderón NT (2022. Mercury Phytotoxicity and Tolerance in Three Wild Plants during Germination and Seedling Development. Plants (Basel). 5;11(15):2046. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalinhoff, C.; Calderón, N.-T. (2022). Mercury Phytotoxicity and Tolerance in Three Wild Plants during Germination and Seedling Development. Plants, 11, 2046.

- Parera, V., Parera, C. A., & Feresin, G. E. (2023). Germination and Early Seedling Growth of High Andean Native Plants under Heavy Metal Stress. Diversity, 15(7), 824. [CrossRef]

- Cakaj, A.; Hanć, A.; Lisiak-Zielińska, M.; Borowiak, K.; Drapikowska, M. (2023). Trifolium pratense and the heavy metal content in various urban areas. Sustainability, 15(9), 7325. [CrossRef]

- Soudek, P. , et al., (2016). Characteristics of different types of biochar and effects on the toxicity of heavy metals to germinating sorghum seeds, Journal of. Geochemistry. Explore. [CrossRef]

- Makarova, A., Nikulina, E., Avdeenkova, T., & Pishaeva, K. (2021). The Improved Phytoextraction of Heavy Metals and the Growth of Trifolium repens L.: The Role of K2HEDP and Plant Growth Regulators Alone and in Combination. Sustainability, 13(5), 2432. [CrossRef]

- Sotiriou V, Michas G, Xiong L, Drosos M, Vlachostergios D, et al. (2023). Effects of heavy metal ions on white clover (Trifolium repens L.) growth in Cd, Pb and Zn contaminated soils using zeolite. Soil Science and Environment 2:4. [CrossRef]

- Kalinhoff C, Calderón NT (2022). Mercury Phytotoxicity and Tolerance in Three Wild Plants during Germination and Seedling Development. Plants (Basel). 5;11(15):2046. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yáñez-Espinosa, L.; Briones-Gallardo, R.; Flores, J.; del Castillo, E. (2020). Effect of heavy metals on seed germination and seedling development of Nama aff. stenophylla collected on the slope of a mine tailing dump. International Journal of Phytoremediation。 22, 1448–1461.

- Nedjimi, B. (2020). Germination characteristics of Peganum harmala L. (Nitrariaceae) subjected to heavy metals: Implications for use in polluted dryland restoration. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 17, 2113–2122. [CrossRef]

- Parera, V., Parera, C. A., & Feresin, G. E. (2023). Germination and Early Seedling Growth of High Andean Native Plants under Heavy Metal Stress. Diversity, 15(7), 824. [CrossRef]

- Sawicka, Barbara, Barbara Krochmal-Marczak, Józef Sawicki, Dominika Skiba, Piotr Pszczółkowski, Piotr Barbaś, Viola Vambol, Mohammed Messaoudi, and Alaa K. Farhan. (2023). "White Clover (Trifolium repens L.) Cultivation as a Means of Soil Regeneration and Pursuit of a Sustainable Food System Model" Land 12, no. 4: 838. [CrossRef]

- Shaiban, H.; Dutoit, T.; Buisson, E.; De Almeida, T.; Khater, C. Trifolium subterraneum as a Potential Nurse Plant for Restoring Soil and Mediterranean Grasslands after Quarry Exploitation in Lebanon. Ecol. Eng. 2025, 216, 107632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai Lin, Chenjing Liu, Bing Li, Yingbo Dong, Trifolium repens L. regulated phytoremediation of heavy metal contaminated soil by promoting soil enzyme activities and beneficial rhizosphere associated microorganisms, Journal of Hazardous Materials, Volume 402, 2021, 123829, ISSN 0304-3894. [CrossRef]

- Cakaj, A.; Hanć, A.; Lisiak-Zielińska, M.; Borowiak, K.; Drapikowska, M. (2023). Trifolium pratense and the heavy metal content in various urban areas. Sustainability, 15(9), 7325. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Wang, J., Bao, Y. et al. Quantitative trait loci controlling rice seed germination under salt stress. Euphytica 78, 297–307 (2011).

- Hossain, M.A. Enhancing Seed Germination and Seedling Growth Attributes of a Medicinal Tree Species (Terminalia chebula) through Depulping of Fruits and Soaking the Seeds in Water. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2013, 11(3–4), 2573–2578.

- Soudek, Petr, et al. "Effect of heavy metals on inhibition of root elongation in 23 cultivars of flax (Linum usitatissimum L.)." Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 59.2 (2010): 194-203.

- Amooaghaie R, Nikzad K. The role of nitric oxide in priming-induced low-temperature tolerance in two genotypes of tomato. Seed Science Research. 2013;23(2):123-131. [CrossRef]

- Li, Peng, et al. "Germination and dormancy of seeds in Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench (Asteraceae)." Seed Science and Technology 35.1 (2007): 9-20.

- Marcin, O.; Bosiacki, M.; Świerczyński, S. (2025). The effect of increasing doses of heavy metals on seed germination of selected ornamental plant species. Agronomy, 15(6), 1262. [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, M.; Zafar, I.M.; Athar, M. (2008). Effect of lead and cadmium on germination and seedling growth of Leucaena leucocephala. Journal of Applied Science and Environmental Management, 12(2), 61–66. [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.; Shafiq, F.; Nisa, Z.U.; Usman, U.; Ashraf, M.Y.; Ali, N. (2021). Effect of cadmium stress on seed germination, plant growth and hydrolyzing enzyme activities in mungbean seedlings. Journal of Seed Science, 43, e202143042. [CrossRef]

- Marcin et al 2025.

- Mittal, N.; Vaid, P.; Avneet, K. (2015). Effect on amylase activity and growth parameters due to metal toxicity of iron, copper and zinc. Indian Journal of Applied Research, 5(4), 662–664.

- Bezini, E.; Abdelguerfi, A.; Nedjimi, B.; Touati, M.; Adli, B.; Yabrir, B. (2019). Effect of some heavy metals on seed germination of Medicago arborea L. (Fabaceae). Agriculturae Conspectus Scientificus, 84, 29–34.

- Patel et al., 2013.

- Abusriwil, L.M.H.; Hamuda, H.E.A.F.; Elfoughi, A.A. (2011). Seed germination, growth and metal uptake of Medicago sativa L. grown in heavy metal contaminated clay loam brown forest soil. Journal of Landscape Ecology, 9, 111–125.

- Đukić, M.; Đunisijević-Bojović, D.; Samuilov, S. (2014). The influence of cadmium and lead on Ulmus pumila L. seed germination and early seedling growth. Archives of Biological Sciences, 66(1), 253–259. [CrossRef]

| Effect | Value | F | Hypothesis df | Error df | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Pillai's Trace | 1 | 24544.908b | 11 | 2 | <.001 |

| Wilks' Lambda | 0 | 24544.908b | 11 | 2 | <.001 | |

| Hotelling's Trace | 134997 | 24544.908b | 11 | 2 | <.001 | |

| Roy's Largest Root | 134997 | 24544.908b | 11 | 2 | <.001 | |

| Metals | Pillai's Trace | 2.993 | 153.676 | 33 | 12 | <.001 |

| Wilks' Lambda | 0 | 545.683 | 33 | 6.596 | <.001 | |

| Hotelling's Trace | 19557.32 | 395.097 | 33 | 2 | 0.003 | |

| Roy's Largest Root | 11390.94 | 4142.159c | 11 | 4 | <.001 | |

| Conc | Pillai's Trace | 1.981 | 27.832 | 22 | 6 | <.001 |

| Wilks' Lambda | 0 | 147.271b | 22 | 4 | <.001 | |

| Hotelling's Trace | 12762.89 | 580.131 | 22 | 2 | 0.002 | |

| Roy's Largest Root | 12712.15 | 3466.951c | 11 | 3 | <.001 | |

| Metals * Conc | Pillai's Trace | 5.215 | 4.226 | 66 | 42 | <.001 |

| Wilks' Lambda | 0 | 21.012 | 66 | 16.158 | <.001 | |

| Hotelling's Trace | 13629.36 | 68.835 | 66 | 2 | 0.014 | |

| Roy's Largest Root | 13320.92 | 8476.947c | 11 | 7 | <.001 |

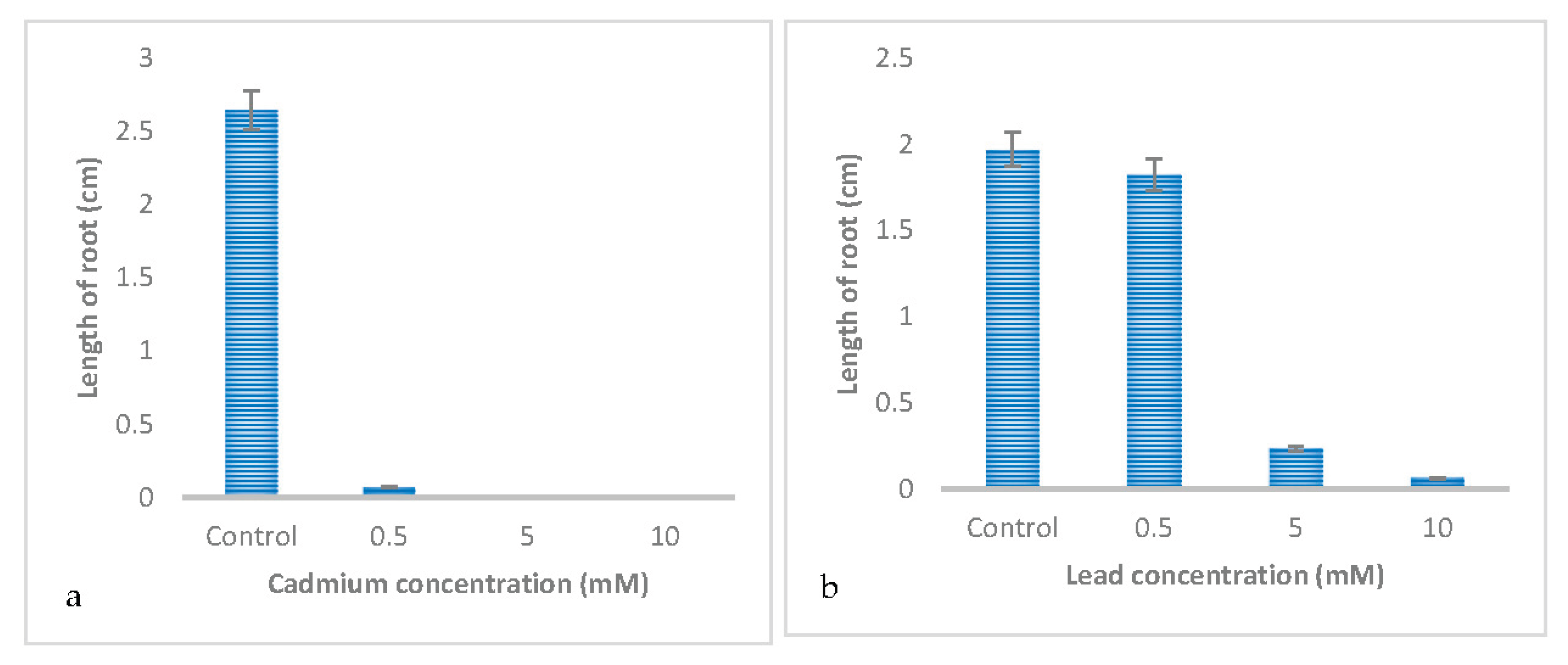

| Metals | Cadmium | Lead | Arsenic | Mercury |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoot length | 0.126 ± 0.057 c | 1.101 ± 0.057 a | 0.354 ± 0.057 b | 0.861 ± 0.057 a |

| Root length | 0.022±0.061 c | 0.351±0.061 b | 0.097±0.061 c | 0.625±0.061 a |

| Control shoot | 2.687±0.033a | 2.687±0.033a | 2.687±0.033a | 2.688±0.033a |

| Control root | 1.128±0.039a | 1.128±0.039a | 1.128±0.039a | 1.128±0.039a |

| GR | 18.849±6.483b | 27.877±6.483b | 26.885±6.483b | 79.984±6.483a |

| GI | 12.029±0.803c | 17.517±0.803b | 34.916±0.803a | 10.733±0.803c |

| Control GI | 20.743±0a | 20.743±0a | 20.743±0a | 20.743±0a |

| MGT | 90.539±5.359b | 141.465±5.359a | 136.515±5.359a | 136.515±5.359a |

| VI | 1.962±6.475b | 18.954±6.475b | 12.172±6.475b | 79.984±6.475a |

| VI control | 55.746±0.69a | 55.746±0.69a | 55.746±0.69a | 55.746±0.69a |

| RGI | 57.989±3.871c | 84.451±3.871b | 168.327±3.871a | 51.745±3.871c |

| RVI | 3.486±11.083b | 33.714±11.083b | 21.611±11.083b | 141.775±11.083a |

| RRL | 2.248±6.212b | 34.049±6.212a | 9.847±6.212b | 56.272±6.212a |

| RSL | 4.634±1.96c | 40.603±1.96a | 13.039±1.96b | 31.947±1.96a |

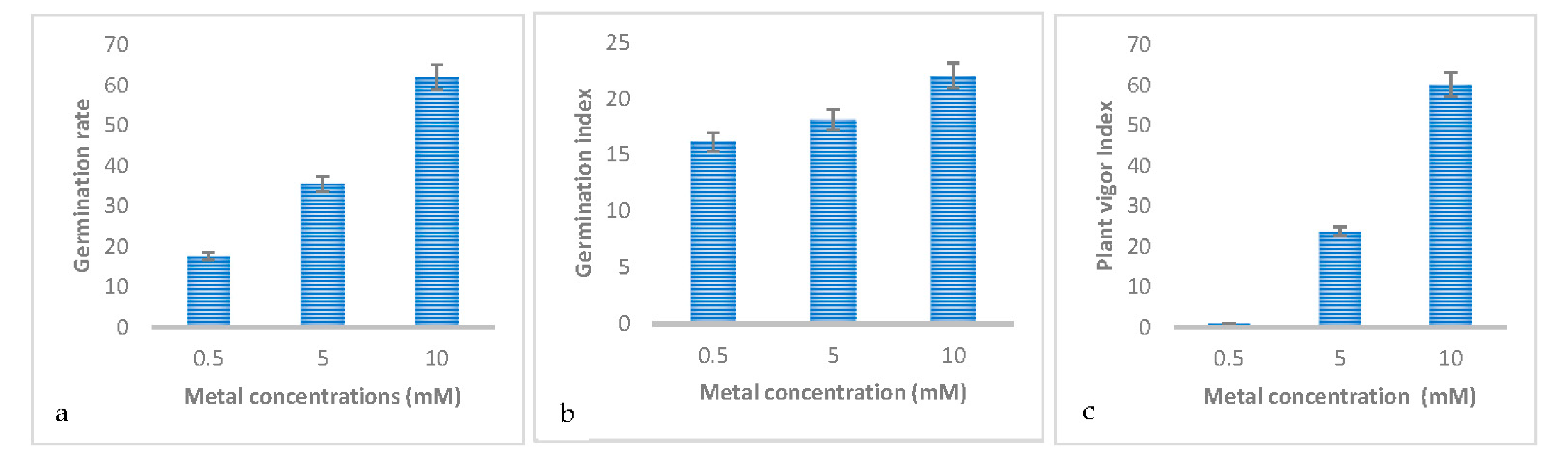

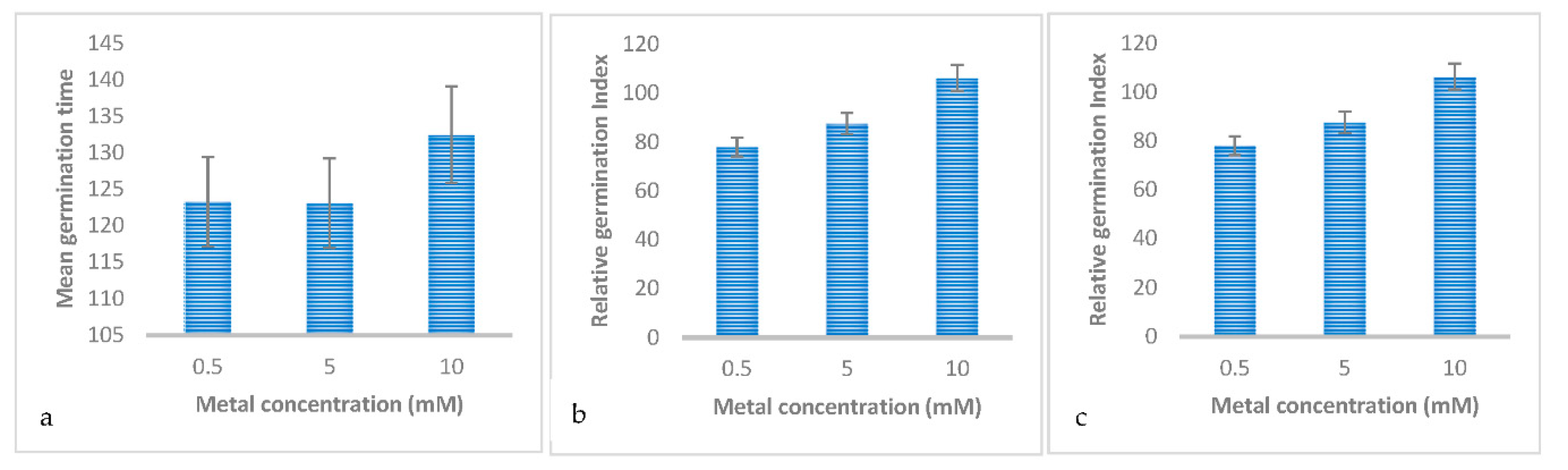

| Conc | 0.5mM | 5mM | 10mM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shoot length | 0.164±0.049c | 0.515±0.049b | 1.153±0.049a |

| Root length | 0.118±0.053b | 0.27±0.053ab | 0.4330.053a |

| Control shoot | 2.648±0.029a | 2.7±0.029a | 2.715±0.029a |

| Control root | 1.171±0.034a | 1.252±0.034a | 0.96±0.034b |

| Germination rate | 17.634±5.614b | 35.553±5.614b | 62.009±5.614a |

| Germination index | 16.179±0.695b | 18.162±0.695b | 22.055±0.695a |

| Control germination index | 20.743±0a | 20.743±0a | 20.743±0a |

| Mean germination time | 123.258±4.641a | 123.058±4.641a | 132.459±4.641a |

| Relative vigor | 1.544±9.598c | 42.048±9.598b | 106.848±9.598a |

| Relative germination index | 78±3.352b | 87.556±3.352b | 106.327±3.352a |

| Control vigor | 54.925±0.597a | 56.006±0.597a | 56.308±0.597a |

| Vigor | 0.859±5.607c | 23.783±5.607b | 60.162±5.607a |

| Relative shoot length | 6.16±1.697b | 19.05±1.697b | 42.457±1.697a |

| Relative root length | 10.047±5.38b | 21.692±5.38b | 45.073±5.38a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).