Submitted:

05 November 2024

Posted:

06 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analysis of Water Samples Used for Irrigation

2.2. Studies on Germination and Seedling Growth

3. Results

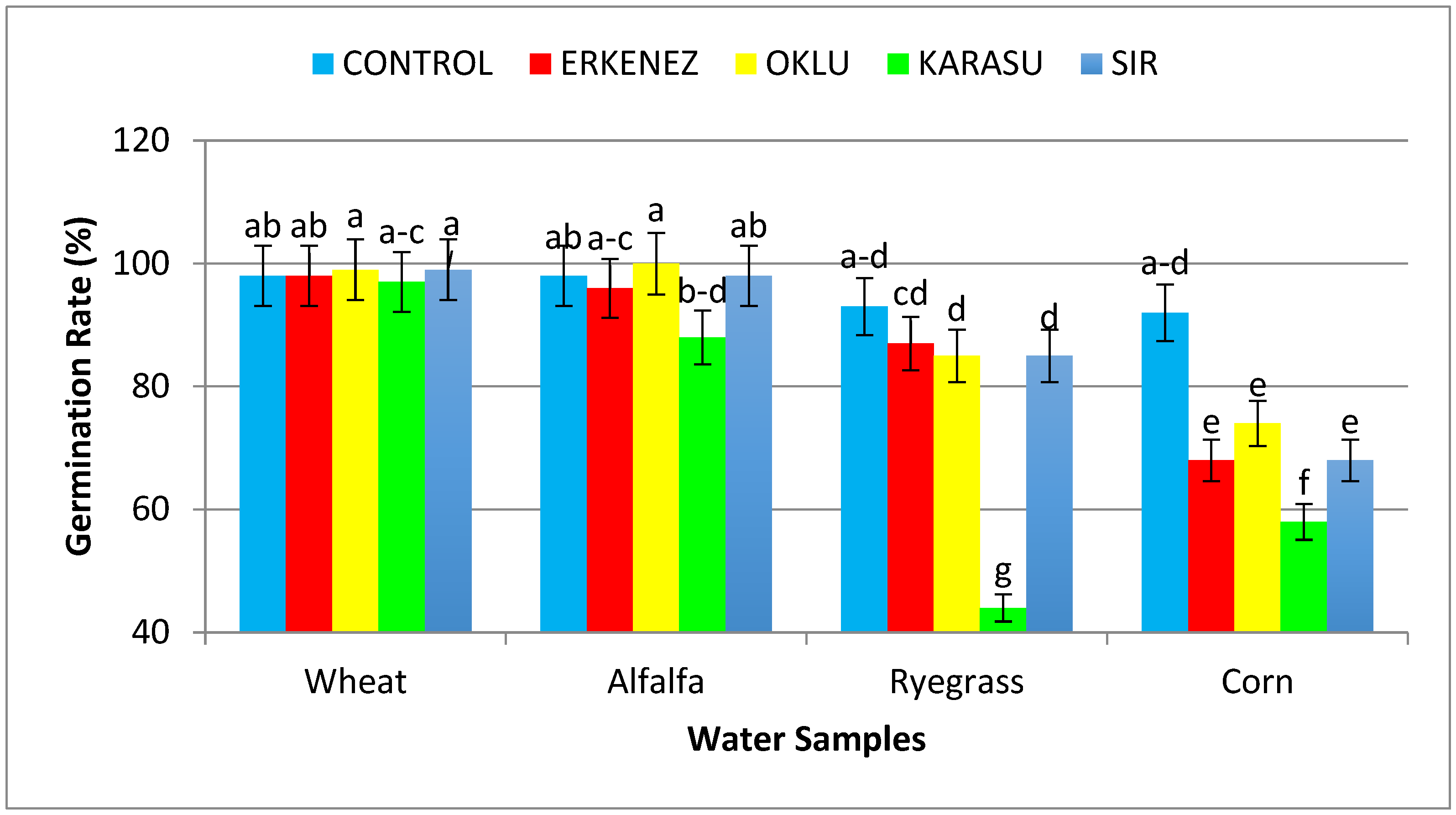

3.1. Germination Rate (%)

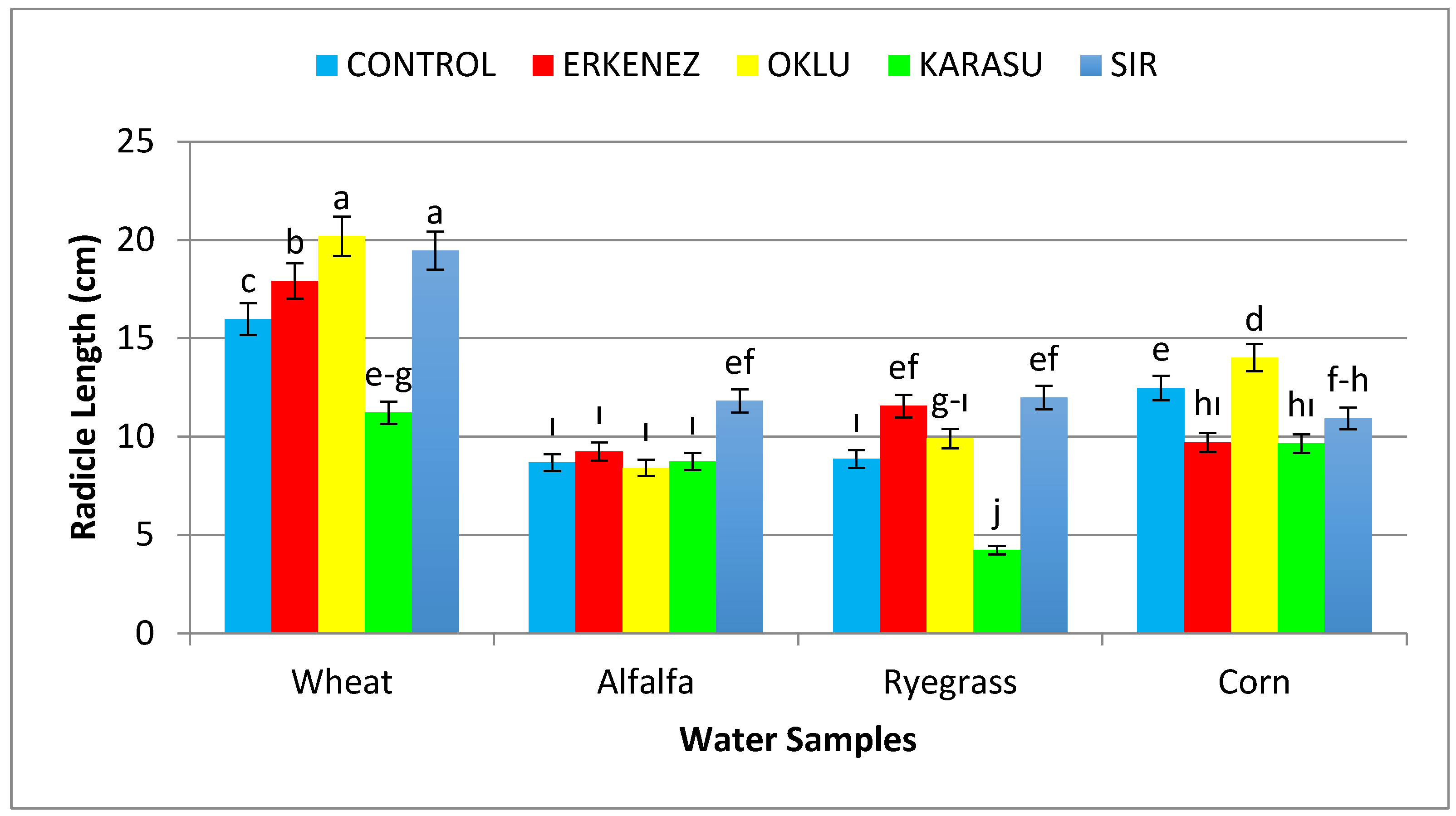

3.2. Radicle Length (cm)

3.3. Plumule Length (cm)

3.4. Seedling Length (cm)

3.5. Seedling Fresh Weight (g)

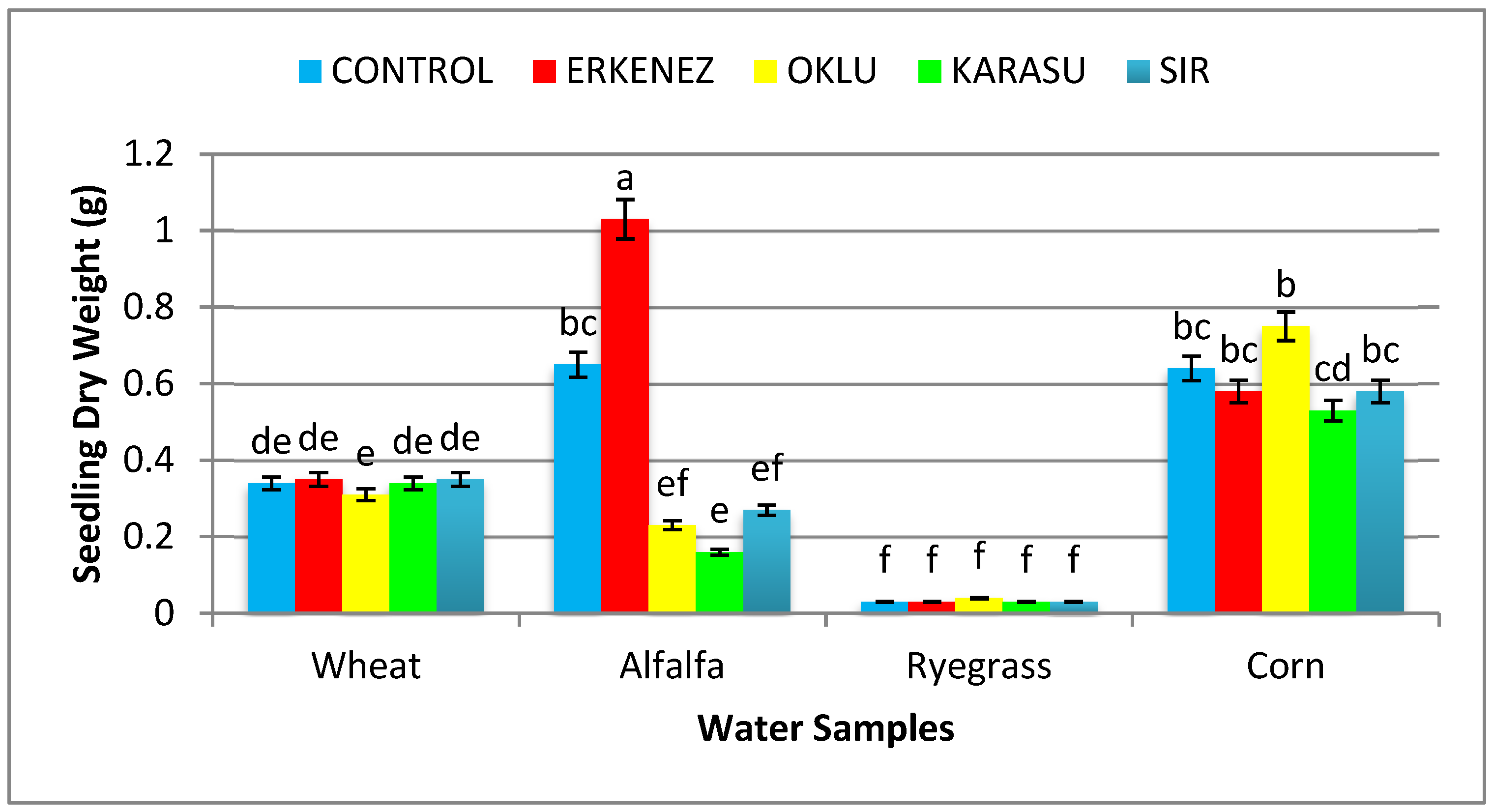

3.6. Seedling Dry Weight (g)

3.7. Vigor Index

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ogundele, D.T.; Oladejo, A.A.; Oke, C.O. Effect of pharmaceutical effluent on the growth of crops in Nigeria. Chem Sci Intern J 2018, 25, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Li, Q.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, C.; Ouyang, K.; You, P. Risk assessment of heavy metals in soils of a lead-zinc mining area in Hunan Province (China). Kemija u industriji: Časopis kemičara i kemijskih inženjera Hrvatske 2017, 66, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabata-Pendias, A.; Pendias, H. Trace elements in soils and plants; CRC Press: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lasat, M.M. Phytoextraction of toxic metals. A review of biological mechanism, J Environ Quality, 2002, 31, 109-120.

- Rai, U.N.; Tripathi, R.D.; Vajpayee, P.; Jha, V.; Ali, M.B. Bioaccumulation of toxic metals (Cr, Cd, Pb and Cu) by seeds of Euryale ferox Salisb (Makhana). Chemosphere. 2002, 46, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dindaroğlu, T.; Babur, E.; Laz, B. Determination of the ecology and heavy metal tolerance limits of Alyssum Pateri subsp. Pateri growing on ultramafic soils. J Soil Sci Plant Nut. 2019, 7, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashmir, S.; Khan, M.A.; Shad, A.A.; Marwat, K.B.; Khan, H. Temperature and salinity affect the germination and growth of Silybum marianum Gaertn and Avena fatua L. Pak J of Botany. 2016, 48, 469–476. [Google Scholar]

- Kuriakose, S.V.; Prasad, M.N.V. Cadmium stress affects seed germination and seedling growth in Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench by changing the activities of hydrolysing enzymes. Plant Growth Regul. 2008, 54, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Keturi, P.H. Comparative seed germination test using ten plant species for toxicity assessment of metals engraving effluent sample. Water, Air, Soil Poll. 1990, 52, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, A.H.; Tabrez, S.; Ahmad, M. Validation of plant-based bioassays for the toxicity testing of Indian waters. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011, 179, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S.A.; Peerzada, P.H.; Javed, A.M.; Dawood, M.H.; Hussain, N.M.; Ahmad, S. Growth and development dynamics in agronomic crops under environmental stress. In Agronomic crops; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 83–114. [Google Scholar]

- Uslu, O.S.; Babur, E.; Alma, M.H.; Solaiman, Z.M. Walnut shell biochar increases seed germination and early growth of seedlings of fodder crops. Agriculture 2020, 10, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, N.; Sharma, C.P. Effect of heavy metals Co2+, Ni2+ and Cd2+ on growth and metabolism of cabbage. Plant Sci. 2002, 163, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belimov, A.A.; Safronova, V.I.; Tsyganov, V.E.; Borisov, A.Y.; Kozhemyakov, A.P.; Stepanok, V.V.; Tikhonovich, I.A. Genetic variability in tolerance to cadmium and accumulation of heavy metals in pea (Pisum sativum L.). Euphytica. 2003, 131, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munzuroğlu, O.; Geçkil, H. Effects of metals on seed germination, root elongation, and coleoptile and hypocotyl growth in Triticum aestivum and Cucumis sativus. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2002, 43, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Ghamery, A.A.; El-Kholy, M.A.; Abou El-Yousser, M.A. Evaluation of cytological effects of Zn2+ in relation to germination and root growth of Nigella sativa L. and Triticum aestivum L. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2003, 537, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King-Díaz, B.; Montes-Ayala, J.; Escartín-Guzmán, C.; Castillo-Blum, S.E.; Iglesias-Prieto, R.; Lotina-Hennsen, B.; Barba-Behrens, N. Cobalt (LI) coordination compounds of ethyl 4-methyl-5-imidazolecarboxylate: chemical and biochemical characterization on photosynthesis and seed germination. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2005, 3, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.W.; Zhu, M.Y.; Chen, H. Aluminum-induced cell death in root-tip cells of barley. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2001, 46, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazkiewicz, M.; Baszynski, T. Growth parameters and photosynthetic pigments in leaf segments of Zea mays exposed to cadmium, as related to protection mechanisms. J Plant Physiol. 2005, 162, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarup, L. Hazard of heavy metal contamination, Br. Med. Bull. 2003, 68, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo, R.A.; Lea, P.J. Toxic metals in plants, Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2005, 17, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Babula, P.; Adam, V.; Opatrilova, R.; Zehnalek, J.; Havel, L.; Kizek, R. Uncommon heavy metals, metalloids and their plant toxicity: a review, Environ. Chem. Lett. 2008, 6, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.J.; Foy, C.D. Differential uptake and toxicity of ionic and chelated copper in Triticum aestivum, Canad. J. Bot. 1985, 63, 1271–1275. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, D.M.; Power., I.L.; Edmeades, D.C. Effect of various metal ions on growth of two wheat lines known to differ in aluminium tolerance. Plant Soil. 1993, 155/156, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater, 20th ed.; APHA; AWWA; WPCF: New York, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Anonymous. www.cygm.gov.tr/CYGM/Files/mevzuat/teblig/STYD1.doc. 1991. Date of access:18.11. 2017. Available online: www.cygm.gov.tr/CYGM/Files/mevzuat/teblig/STYD1.doc (accessed on 18 November 2017).

- Kacar, B.; Inal, A. Plant analysis. Nobel publication No. 1241; Nobel Publication Distribution Ltd.: Ankara, 2008; p. 892. [Google Scholar]

- SAS. SAS 9.3 User Guide, Copyright © 2013; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Steel, R.G.D.; Torrie, J.H. Principles and procedures of statistics.; McGraw-Hill: New York, 1980; p. 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Donohue, K.; de Casas, R.R.; Burghardt, L.; Kovach, K.; Willis, C.G. Germination, postgermination adaptation, and species ecological ranges. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2010, 41, 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioria, M.; Pyšek, P. Early bird catches the worm: Germination as a critical step in plant invasion. Biol. Invasions 2017, 19, 1055–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badalamenti, E.; Militello, M.; la Mantia, T.; Gugliuzza, G. Seedling growth of a native (Ampelodesmos mauritanicus) and an exotic (Pennisetum setaceum) grass. Acta Oecol. 2016, 77, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, N.; Lee, D.G.; Lee, S.H.; Kang, K.Y.; Lee, J.J.; Kim, P.J.; Yoon, H.S.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, B.H. Excess copper induced physiological and proteomic changes in germinating rice seeds. Chemosphere. 2007, 67, 1182–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, M.J.; Tao, Q.B.; Zhang, Z.X.; Lang, S.Q.; Li, J.H.; Chen, D.L.; Wang, Y.R.; Hu, X.W. Effect of drip irrigation on seed yield, seed quality and water use efficiency of Hedysarum fruticosum in the arid region of Northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 278, 108137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mircea, D.M.; Estrelles, E.; Al Hassan, M.; Soriano, P.; Sestras, R.E.; Boscaiu, M.; Sestras, A.F.; Vicente, O. Effect of Water Deficit on Germination, Growth and Biochemical Responses of Four Potentially Invasive Ornamental Grass Species. Plants 2023, 12, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dindaroglu, T.; Babur, E.; Battaglia, M.; Seleiman, M.; Uslu, O.S.; Roy, R. Impact of Depression Areas and Land-Use Change in the Soil Organic Carbon and Total Nitrogen contents in a Semi-Arid Karst Ecosystem. CERNE. 2021, 27, e-102980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babur, E.; Dindaroğlu, T.; Riaz, M.; et al. Seasonal Variations in Litter Layers’ Characteristics Control Microbial Respiration and Microbial Carbon Utilization Under Mature Pine, Cedar, and Beech Forest Stands in the Eastern Mediterranean Karstic Ecosystems. Microb Ecol. 2022, 84, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadinezhad, P.; Payamenur, V.; Mohamadi, J.; Ghaderifar, F. The effect of priming on seed germination and seedling growth in Quercus castaneifolia. Seed Sci. Technol. 2013, 41, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundada, P.S.; Sonawane, M.M.; Shaikh, S.S.; Barvkar, V.T.; Kumar, S.A.; Umdale, S.D.; Suprasanna, P.; Barmukh, R.B.; Nikam, T.D.; Ahire, M.L. Silicon alleviates PEG-induced osmotic stress in finger millet by regulating membrane damage, osmolytes, and antioxidant defense. Not. Sci. Biol. 2022, 14, 11097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, N.; Abdou, M.A.H.; Salaheldin, S.; Soliman, W.S. Lemongrass Growth, Essential Oil, and Active Substances as Affected by Water Deficit. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsamo, C.; Alanyuy, S.M.; Zama, E.F.; Tamu, C.C. Germination and survival of maize and beans seeds: effects of ırrigation with NaCl and heavy metals contaminated water. Open J Applied Sci. 2022, 12, 769–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvendran, S.; Johnson, D.; Acevedo, M.; Smithers, B.; Xu, P. Effect of Irrigation Water Quality and Soil Compost Treatment on Salinity Management to Improve Soil Health and Plant Yield. Water. 2024, 16, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, M.J.; AL-Mefleh, N.; Mohawesh, O. Effect of irrigation water qualities on Leucaena leucocephala germination and early growth stage. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 9, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.C.; Li, Y.Y.; Yang, J.S.; Laing, Y.S. Effect of brackish water irrigation and straw mulching on soil salinity and crop yields under monsoonal climatic conditions. Agri Water Manag. 2009, 97, 1971–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebi, S.; Kalat, S.N.; Darban, A.S. The study effects of heavy metals on germination characteristics and proline content of Triticale (Triticoseale Wittmack). Inter J Farm Allied Sci. 2014, 3, 1080–1087. [Google Scholar]

- Khajeh-Hosseini, M.; Powell, A.A.; Bingham, I.J. The interaction between salinity stress and seed vigour during germination of soybean seeds. Seed Sci. Technol. 2003, 31, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, Y.; Munzuroglu, O. The effects of lead on the seed germination and seedling growth of lens (Lens culinaris Medic.). Firat University, J. Sci. Eng. 2004, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman Khan, M.; Mahmud Khan, M. Effect of varying concentration of nickel and cobalt on the plant growth and yield of chickpea. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2010, 4, 1036–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, D.; Nath, K.; Kumar Sharma, Y. Response of wheat seed germination and seedling growth under copper stress. J. Environ. Biol. 2007, 28, 409–414. [Google Scholar]

- Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L.; Gomez, E.; Tiermann, K.J.; Parsons, J.G.; Carrillo, G. Effect of mixed cadmium, copper, nickel and zinc at different pHs upon alfalfa growth and heavy metal uptake. Environ. Poll. 2002, 119, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmat, R.; Haider, S.; Nasreen, H.; Aziz, F.; Riaz, M. A viable alternative mechanism in adapting the plants to heavy metal environment. Pakistan J. Bot. 2009, 41, 2729–2738. [Google Scholar]

- Azmat, R.; Haider, S.; Askari, S. Phyotoxicity of Pb: I. Effect of Pb on germination, growth, morphology and histomorphology of Phaseolus mungo and Lens culinaris. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2006, 9, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhead, J.L.; Gogolin Reynolds, K.A.; Abdel-Ghany, S.E.; Cohu, C.M.; Pilon, M. Copper homeostasis. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 799–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Peñalver, A.; Graña, E.; Reigosa, M.J.; Sánchez-Moreiras, A.M. The early response of Arabidopsis thaliana to cadmium- and copper-induced stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2012, 78, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.A.; Fariduddin, Q.; Ali, B.; Hayat, S.; Ahmad, A. Cadmium: Toxicity and tolerance in plants. J.Environ. Biol. 2009, 30, 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Skórzyńska-Polit, E.; Drążkiewicz, M.; Krupa, Z. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidative response in Arabidopsis thaliana exposed to cadmium and copper. Acta Physiol Plant 2010, 32, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, R.; Gadgil, K.; Sharma, G. Heavy metal toxicity: Effect on plant growth, biochemical parameters and metal accumulation by Brassica juncea L. Inter. J. Plant Prod. 2009, 3, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Blum, W.H. Cadmium uptake by higher plants. In Proceedings of Extended Abstracts from the Fourth International Conference on the Biogeochemistry of Trace Elements, University of California, Berkeley, USA, 1997; pp. 109–110. [Google Scholar]

- An, Y.J. Soil ecotoxicity assessment using cadmium sensitive plants. Environ. Pollut. 2004, 127, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Jiang, W.; Meng, Q.; Zou, J.; Gu, J.; Zeng, M. Cytogenetical and ultrastructural effects of copper on root meristem cells of Allium sativum L. Biocell. 2009, 33, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radha, J.; Srivastava, S.; Solomon, S.; Shrivastava, A.K.; Chandra, A. Impact of excess zinc on growth parameters, cell division, nutrient accumulation, photosynthetic pigments and oxidative stress of sugarcane (Saccharum spp.). Acta Physiol. Plant 2010, 32, 979–986. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, A.K.; Prasad, S.; Srivastava, S.K.; Singh, S.P.; Singh, R.P. Allelopathic effect of thatch grass (Imperata cylindrica L.) on various Kharif and Rabi season crops and weeds. Indian J. Weed Sci. 2003, 35, 163–166. [Google Scholar]

- Maity, M.; Chatterjee, G.; Banerjee, R. Water Quality Demonstrates Detrimental Effects on Two Different Seeds during Germination, Curr. Agri. Res. J. 2019, 7, 377–389. [Google Scholar]

- Benavides, M.P.; Gallego, S.M.; Tomaro, M.L. Cadmium toxicity in plants. Braz J Plant Physiol 2005, 17, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, M.; Horváth, E.; Janda, T.; Paldi, E.; Szalai, G. Physiological changes and defense mechanisms induced by cadmium stress in maize. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci. 2006, 169, 239–246. [Google Scholar]

- Eshghi, S.; Mahmoodabadi, M.R.; Abdi, G.R.; Jamali, B. Zeolite Ameliorates the Adverse Effect of Cadmium Contamination on Growth and Nodulation of Soybean Plant (Glycine max L.). J Biol Environ Sci. 2010, 4, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Jun-yu, H.; Yan-fang, R.; Cheng, Z.; De-an, J. Effects of cadmium stress on seed germination, seedling growth and seed amylase activities in rice (Oryza sativa). Rice Sci. 2008, 15, 319–325. [Google Scholar]

- Athar, R.; Ahmad, M. Heavy metal toxicity effect on plant growth and metal uptake by wheat, and on free-living Azotobacter. Water Air Soil Poll. 2002, 180, 138–165. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, L.S.; Liao, M.; Chen, L.C.; Huang, Y.C. Effects of lead contamination on soil enzymatic activities, microbial biomass and rice physiological indices in soil-lead-rice (Oryza sativa L.) system. Ecotoxicol. Environm. Safety. 2007, 67, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OnceOncel, I.; Kele, Y.; Ustun, A.S. Interactive effects of temperature and heavy metal stress on the growth and some biochemical compounds in wheat seedlings. Environ Sci. Technol. 2000, 29, 1232–1238. [Google Scholar]

- Ciamporova, M.; Mistrik, I. The ultra-structural response of root cells to stressful conditions. Environ. Exp. Bot. 1993, 33, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkay, F.; Kiran, S.; Taş, B.I.; Kuşvuran, C.S. Effects of Copper, Zinc, Lead and Cadmium Applied with Irrigation Water on Some Eggplant Plant Growth Parameters and Soil Properties. Turk. J. Agri. Natur. Sci. 2014, 1, 377–383. [Google Scholar]

- Channappagoudar, B.B.; Jalager, B.R.; Biradar, N.R. Allelopathic effect of aqueous extracts of weed species on germination and seedling growth of some crops. Karnataka J. Agric. Sci. 2005, 18, 916–920. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh, I.R.; Shaikh, P.R.; Shaikh, R.A.; Shaikh, A.A. Phytotoxic effects of heavy metals (Cr, Cd, Mn and Zn) on wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seed germination and seedlings growth in black cotton soil of Nanded. Res J Chemical Sci 2013, 3, 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Laz, B.; Babur, E.; Akpınar, D.M.; Avgın, S.S. Determination of biotic and abiotic pests observed in Kahramanmaraş-Elmalar green belt Annex-3 plantation area. KSÜ Agri. Nature J. 2018, 21, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibuike, G.U.; Obiora, S.C. Heavy Metal Polluted Soils: Effect on Plants and Bioremediation Methods. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2014, 752708, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.M.; Kumar, S.G.; Jyonthsnakumari, G.; Thimmanaik, S.; Sudhakar, C. Lead Induced Changes in Antioxidant Metabolism of Horsegram (Macrotyloma uniflorum (Lam.) Verdc.) and Bengalgram (Cicemr arietinum L.). Chemosphere 2002, 60, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, A.K.; Das, A.B. Salt Tolerance and Salinity Effects on Plants: A Review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2005, 60, 324–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, A.; Vangronsveld, J.; Yordanov, I. Cadmium Phytoremediation: present State, Biological Background and Research Needs. Bulg. J. Plant physiol. 2002, 28, 68–95. [Google Scholar]

- Kalyanaraman, S.B.; Sivagurunathan, P. Effect of cadmium, copper and zinc on the growth of blackgram, J. Plant Nutr. 1993, 16, 2029–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewley, R.J.F.; Stotzky, G. Effects of cadmium and zinc on microbial activity in soil; Influence of clay minerals. Part II: Metal added simultaneously. Sci.Tot. Environ. 1983, 31, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgare, S.A.; Acharekar, C. Effect of industrial pollution on growth and content of certain weeds. J.Nat.Conserve. 1992, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.L. Copper uptake and inhibition of growth, photosynthetic pigments and macromolecules in the cyanobacterium Anacystis ridulans. Phytosynthetica 1986, 20, 447–452. [Google Scholar]

- Satayakala, G.; Jamil, K. Studies on the effect of heavy metal pollution on Pistia statiotes L., (Water lettuce). Indian. J. Environ. Health 1997, 39, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

| Karasu Creek | Erkenez Creek | Oklu Creek | Sır Dam | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude | 37°31'3.45"K | 37°32'25.56"K | 37°33'49.39"K | 37°34'30.35"K |

| Longitude | 36°56'0.85"D | 36°55'13.30"D | 36°54'42.67"D | 36°48'6.19"D |

| Elements | Maximum amount that can be given to the unit (kg ha-1) | Allowable Maximum Concentrations | |

| Boundary values in case of continuous irrigation of all kinds of soil (mg L-1) | When watering less than 24 years in clay soils with a pH value between 6.0-8.5 (mg L-1) | ||

| Arsenic (As) | 90 | 0.1 | 2.0 |

| Cadmium (Cd) | 09 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Chrome (Cr) | 09 | 0.1 | 1.0 |

| Copper (Cu) | 190 | 0.2 | 5.0 |

| Iron (Fe) | 4600 | 5.0 | 20.0 |

| Lead (Pb) | 4600 | 5.0 | 10.0 |

| Nickel (Ni) | 920 | 0.2 | 2.0 |

| AMC | KC | CS | OC | CS | EC | CS | SD | CS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | 0.2 | 0.98 | H | 1.627 | H | 0.945 | H | 1.218 | H |

| Fe | 5.0 | 18.69 | H | 0.555 | L | 2.395 | L | 8.89 | H |

| Pb | 5.0 | 0.00015 | L | 0.00056 | L | 4.5 | L | 0.013 | L |

| Cr | 5.0 | 0.097 | L | 0.00038 | L | 0.02 | L | 0.00013 | L |

| As | 1.0 | 0.206 | L | 0.171 | L | 0.165 | L | 0.132 | L |

| Ni | 0.5 | 0.00328 | L | 0.04 | L | 0.00067 | L | 0.00067 | L |

| Cd | 0.005 | 0.00068 | L | 0.00069 | L | 0.099 | H | 0.115 | H |

| GR (%) | RL (cm) | PL (cm) | SL (cm) | SFW (g) | SDW (g) | VI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ||

| Species | Wheat | 98 a | 16.96 a | 11.63 a | 28.58 a | 1.68 b | 0.34 c | 2812 a |

| Alfalfa | 96 a | 9.38 c | 7.25 b | 16.64 b | 1.46 b | 0.47 b | 1598 b | |

| Ryegrass | 78 b | 9.31 c | 6.97 b | 16.28 b | 0.28 c | 0.04 d | 1352 c | |

| Corn | 72 b | 11.36 b | 6.63 b | 17.99 b | 4.66 a | 0.62 a | 1322 c | |

| LSD | 6.97 | 1.76 | 0.88 | 2.17 | 0.68 | 0.09 | 232.60 | |

| ** | ** | ** | ** | ns | ** | ** | ||

| Irrigation waters | Control | 95 a | 11.50 a | 8.16 a | 19.66 a | 2.17 | 0.42ab | 1874 a |

| Erkenez Creek | 87 a | 12.11 a | 8.55 a | 20.67 a | 2.02 | 0.50 a | 1841 a | |

| Oklu Creek | 89 a | 13.14 a | 8.55 a | 21.69 a | 2.45 | 0.34bc | 1967 a | |

| Karasu Creek | 71 b | 8.46 b | 6.60 b | 15.06 b | 1.61 | 0.27 c | 1177 b | |

| Sır Dam | 87 a | 13.55 a | 8.73 a | 22.28 a | 1.84 | 0.31 bc | 1997 a | |

| LSD | 7.98 | 1.97 | 0.98 | 2.43 | 0.76 | 0.11 | 260.10 | |

| ** | * | ns | Ns | ns | ** | * | ||

| Wheat | Control | 98ab | 15.99 c | 11.03 | 27.01 | 1.51 | 0.34de | 2643 c |

| Erkenez Creek | 98ab | 17.93 b | 11.63 | 29.56 | 1.62 | 0.36de | 2899 b | |

| Oklu Creek | 99a | 20.19 a | 12.83 | 33.02 | 2.04 | 0.32e | 3266 a | |

| Karasu Creek | 97abc | 11.22efg | 10.76 | 21.98 | 1.55 | 0.34de | 2143 d | |

| Sır Dam | 99a | 19.46 a | 11.88 | 31.34 | 1.67 | 0.35de | 3107 a | |

| Alfalfa | Control | 98ab | 8.69ı | 7.00 | 15.68 | 1.37 | 0.65bc | 1538 f |

| Erkenez Creek | 96abc | 9.23ı | 8.06 | 17.31 | 1.83 | 1.04a | 1659ef | |

| Oklu Creek | 100a | 8.42ı | 6.57 | 14.98 | 1.34 | 0.23ef | 1498fg | |

| Karasu Creek | 88bcd | 8.73ı | 6.18 | 14.91 | 1.09 | 0.17ef | 1306gh | |

| Sır Dam | 98ab | 11.83ef | 8.48 | 20.30 | 1.67 | 0.27e | 1988 d | |

|

Italian Ryegrass |

Control | 93abcd | 8.86ı | 7.65 | 16.51 | 0.33 | 0.04f | 1536 f |

| Erkenez Creek | 87cd | 11.56ef | 7.39 | 18.95 | 0.26 | 0.04f | 1653ef | |

| Oklu Creek | 85d | 9.91ghı | 7.40 | 17.31 | 0.36 | 0.05f | 1467fg | |

| Karasu Creek | 44g | 4.25 j | 4.70 | 8.95 | 0.21 | 0.03f | 429 j | |

| Sır Dam | 85d | 11.98ef | 7.69 | 19.67 | 0.23 | 0.04f | 1672ef | |

| Corn | Control | 92abcd | 12.48 e | 6.97 | 19.45 | 5.48 | 0.65bc | 1778 e |

| Erkenez Creek | 68e | 9.71 hı | 7.14 | 16.85 | 4.36 | 0.59bc | 1149 h | |

| Oklu Creek | 74e | 14.03 d | 7.41 | 21.44 | 6.08 | 0.76b | 1636ef | |

| Karasu Creek | 58f | 9.65 hı | 4.77 | 14.41 | 3.58 | 0.53cd | 827ı | |

| Sır Dam | 68e | 10.93fgh | 6.87 | 17.80 | 3.78 | 0.58bc | 1218 h | |

| LSD | 9.09 | 1.37 | 0.46 | 1.60 | 0.38 | 0.18 | 186.90 | |

| Mean | 86 | 11.75 | 8.12 | 19.87 | 2.02 | 0.37 | 1771 | |

| CV % | 12.77 | 23.64 | 17.04 | 17.24 | 53.28 | 41.27 | 20.74 | |

| **Significant at P<0.01; * Significant at P<0.05 ns: not significant; GR: Germination Rate; RL: Radicle length; PL: Plumule Length; SFW: Seedling Fresh Weight; SDW: Seedling Dry Weight; VI: Vigour Index (Different letters stand for statistically significant differences at p<0.05 (Fisher LSD test)). | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).