In this study, we propose comparing humans and mice across the entire spectrum of diseases from three distinct perspectives: MVD using perfusion and metabolic data, MCA network clusters, and functional variations derived from metabolic readouts. To conduct these comparisons, we utilized previously developed pre-clinical and clinical workflows.[

17,

18,

20,

21] However, an important limitation in these inter-species comparisons lies in the absence of direct one-to-one structural and functional alignments.[

7,

11] In the case of AD, this is because no mouse model can encompass the full spectrum of the human disease.[

16,

19] Therefore, to overcome these limitations, it is essential to select a specific disease stage and utilize the corresponding reference and experimental mouse models. Moreover, non-diseased (wild-type) C57BL/6J mice (B6) are not a proper representation of CN human patients, due to differences between mouse and human APOE, leading to the creation of “humanized” APOE mice, which contains the APOE3 gene.[

27] Beyond the scope of this manuscript, B6 mice can be used to examine how these genes differ from normal mouse biology, thus serving as a reference under these conditions.[

28] In summary, while humans can always be compared to CN, in mouse models, it is necessary to include a reference group alongside the experimental group.

3.1. Neuro-Vascular and Metabolic Uncoupling Perspective

Following previous pre-clinical and clinical studies performed by our lab and others,[

17,

18,

20,

21] MVD represents one of the earliest changes in AD progression, occurring prior to hallmark pathological features (i.e., amyloid-beta and tau tangles accumulation) and manifestation of clinical symptoms (i.e., cognitive and memory decline, behavioral changes) regardless of species.[

17,

20] This dysregulation initiates a cascade of physiological events (i.e., neuroinflammation,[

29] glial cell activation,[

30] vascular proliferation[

31]), highlighting both widespread and region-specific alterations across the brain.[

17,

20,

32,

33] Hence, distinct disease phenotypes can be determined based on the set of characteristics associated with this dysregulation. For instance, as mentioned in our previous works,[

20] disease progression begins with uncoupled responses between metabolism and perfusion, resulting in two phenotypes: Type 1 Uncoupling (T1U; ↑CBF ↓MET) and Type 2 Uncoupling (T2U; ↓CBF ↑MET ).[

20] Then, the disease progression follows an abnormal coupled response, which results in two distinct phenotypes: Prodromal Coupling (PC; ↑CBF ↑MET ) and Neuro-metabolic-vascular failure (NMVF; ↓CBF ↓MET ).[

20] These trajectories has been referred to as the MVD pattern, and is common across species.[

17,

20] For instance, each brain region follows its own MVD trajectory, with susceptible regions, such as the temporal gyrus, occipital pole, and planum polare in humans, and primary somatosensory cortex (S1), parietal cortex post-rostral (PtPR), and retrosplenial cortex (RSC) in mice progressing faster through the MVD pattern (

Figure 1).[

17,

20]

For instance, by processing both mouse and human datasets using a translational-capable framework as described in our previous studies,[

17,

18,

20,

21] we can compare results within the same domain, with minor species-dependent differences. The comparative analysis using neurovascular uncoupling charts (

Figure 2) across human and mouse data reveals both conserved and divergent patterns of dysregulation associated with AD progression (or risk factors in mice). In these charts, the scatter plots illustrate the relationship between brain atlas region, cerebral perfusion (x-axis), and metabolic uptake (y-axis) for both sexes.

The human data (

Figure 2.A-D) show that the overall trajectory followed by the brain regions from EMCI to AD, both relative to CN, is: T1U→T2U→PC→NVMF. In addition, it can be observed that females progress faster through this sequence, as previously described.[

20] However, the dispersion at early stages of the AD is less pronounced compared to later stages, and described in our previous work.[

20] By comparison, the mouse models (

Figure 2.E-H) follow the same MVD pattern as humans, but exhibit more pronounced variations in neurovascular uncoupling, making the overall MVD trajectory more noticeable. This exaggerated phenotypical response in mouse (compared with humans) could be due to the different combinations of genetic variants in the mouse models (i.e., LOAD1, LOAD2, APOE3, APOE4), age effect (i.e., 12-months, 18-months), environmental manipulations (i.e., diet effect), illustrating that no single mouse model is able to encapsulate the complete spectrum of human AD. Importantly, these responses offers the benefit of displaying clear, reproducible pathological changes, with a large dynamic range, which occur over a compressed timeframe, allowing rapid evaluation of disease mechanisms and therapeutic responses, and thereby circumventing the slow and variable progression seen in naturally occurring clinical cases, which take 15-30 times longer to develop than in mouse models.[

3] Importantly, this feature allows one to perform a precision medicine approach, where one selects a mouse model, which carefully aligns to the mechanism of action of the drug, thus permitting hypothesis testing with a translatable biomarker.

Overall, both mouse and human cases demonstrate substantial similarities in the MVD trend exhibited by brain regions with respect to cerebral perfusion and metabolic uptake alterations associated with AD progression. In both species, the progressive dysregulation of brain metabolism manifests as variable uncoupling and coupling between perfusion and metabolism, accompanied by the emergence of distinct metabolic brain region clusters. In particular, this process starts with T1U followed by T2U, two uncoupling phenotypes. Then, the disease progression shows prodromal and NVMF coupling phenotypes, which manifest with disease severity, age, and interaction of genes, age, and environmental drivers.

In

Figure 2, for each condition, the corresponding mouse model displayed below the human uncoupling chart serves as a functional and metabolic analog, such that the LOAD1+HFD relative to LOAD1 at 12 months mirrors the EMCI relative to CN transition in humans, modeling early-stage vascular and metabolic impairment under combined genetic and dietary risk. Likewise, LOAD2+HFD relative to LOAD2 at 12 months, LOAD2+HFD relative to LOAD2 at 18 months, and APOE4 relative to APOE3 mouse groups exhibit progressive genetically and diet-driven NVC alterations comparable to those observed across MCI, LMCI, and AD relative to CN. In each case, the clustering and directionality of the relation between perfusion–metabolism uncoupling/coupling phenotype in the mouse data recapitulate, with an increased and exaggerated effect, the organization observed in humans, and the appearance of coupled and uncoupled phenotypes. Notably, both species datasets exhibit sex-related dysregulation patterns, with recent findings confirming broad sex-specific metabolic signatures in AD patients and mouse models, including conserved alterations in lipid metabolism and energy pathways.[

21,

34] Collectively, these inter-species parallels underscore that the core metabolic disturbances underlying neurodegeneration are evolutionarily conserved,[

18,

21,

34,

35] validating the translational value of these animal models for elucidating disease mechanisms and testing targeted therapeutic strategies.

In summary, these MVD changes are consistently observed in both mouse models and clinical human cases, underscoring the relevance of regional MVD trajectories to disease progression rather than an isolated, species-specific phenomenon. Hence, the consistency of MVD as an inter-species event affirms the value of these changes as predictive and diagnostic biomarkers for disease staging, monitoring, and progression in humans, as well as highlighting the translational potential of mouse models. An important limitation is the need to strategically select mouse models that accurately reflect the disease phenotypes observed in humans, given that a single mouse model cannot capture the whole human AD spectrum. However, if the mouse models are correctly selected, it will allow researchers to use these systems to conduct therapeutic testing in mice, thereby improving the likelihood that observed effects will be meaningful in clinical settings. Such an approach not only advances understanding of disease mechanisms, but also enhances the development and preclinical validation of interventions that target these crucial physiological pathways.

3.2. Metabolic Connectomics Perspective

Currently, ADRD is characterized by pronounced dysregulation of brain energy metabolism, with alterations in glucose uptake and mitochondrial dysfunction as central pathological features.[

32,

36] These metabolic impairments drive bioenergetic stress, as the human brain requires glucose transport and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to meet its high energy demands, supporting synaptic transmission and neuronal activity.[

32] Moreover, these variations precede clinical symptoms and are tightly linked to pathological processes such as amyloid-beta accumulation,[

32] tau hyperphosphorylation,[

32] and glial cell activation,[

30] which contribute to neuronal loss, synaptic weakening, and cognitive degradation.[

32,

37] The main theories that support these neurometabolic changes are the brain metabolic reprogramming,[

33,

38] energy fuel switching,[

39] and energy failure.[

40]

Functional connectomics studies highlight metabolic disconnection, which causes brain network remodeling in response to changes in the energy demand and disruption.[

33,

38] On the other hand, from the bioenergetic hypotheses,[

39,

40] it has been proposed that impaired cerebral glucose metabolism (especially in cortical regions, parietal lobes, and the hippocampus) drives pathogenesis and cognitive decline by contributing to amyloid and tau pathologies. Recent metabolomics studies confirm these findings, which include glycolytic flux impairment and activation of ketone metabolism.[

41] Furthermore, this emphasizes that metabolic deficits may trigger a cascade of events, including neuronal dysfunction due to energy deficits,[

36] chronic oxidative stress,[

42] and neuroinflammation,[

29] all of which are connected to metabolic stress and neurodegeneration.[

29,

36,

42] In addition to impairing ATP production, mitochondrial metabolic dysfunction exacerbates inflammatory responses in the brain due to the excessive production of reactive oxygen and altered redox signaling.[

32,

36] Lastly, glial cell activation alters cytokine signaling, causing a shift to astrocyte energy support, which further contributes to the destructive cycle that affects neuronal viability and network plasticity.[

43]

All these theories[33,38-40] share the idea that these metabolic changes trigger compensatory brain structural and functional restructuring to adapt the brain to increased bioenergetic deficits, switching energy fuel sources, neuronal loss due to oxidative stress, and/or a combination of factors[33,38-40] exhibited in preclinical and clinical studies.[

18,

21] Recent studies have shown that early local and global network changes are compensatory adaptations aimed at preserving cognitive function;[

18,

21,

33,

38] for example, an increase in metabolic uptake, which serves as a temporary buffer against functional loss.[

36] Importantly, this temporal buffer is designed to be short lived, and under disease conditions, this excessive energy consumption leads to network failure.[40,44-47]

An important factor that has been largely ignored is the sex-dependent changes, with recent studies advocating for sex-stratified analyses given the sexual dimorphism that occurs in network organization, mitochondrial function, and glucose metabolism.[

18,

21,

33,

48] For example, female-specific transcriptomic pathways involving ALDOA (aldolase A enzyme), ENO2 (enolase 2), PRKACB (beta-catalytic subunit of protein kinase A), and PPP2R5D (serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2A) reveal regulatory mechanisms of energy metabolism that are either delayed or absent in males.[

48] Other factors that need to be accounted for that further emphasize this sexual dimorphism are differential hormonal regulation,[

49] genetic risk,[

49] and neuroinflammatory response;[

49] all of which could help enhance our understanding of sex-specific neural adaptation strategies to metabolic stress.[

48,

49] Consequently, we hypothesize, as many in the research community do, that analyzing sex-specific metabolic alterations and compensatory mechanisms may enable accurate modeling of AD pathophysiology, as well as a more comprehensive framework for developing precision diagnostics and therapeutic strategies tailored to individual bioenergetic and network profiles.[

20,

21,

34,

50]

Analyzing and comparing inter-species metabolic connectomics changes offers a highly integrative framework for comparison by unifying molecular energy dysregulation, network reorganization, and sex-specific biology into a single analytical perspective.[

21,

34,

35] This framework is supported by distinct metabolic changes in the presence of pathological conditions and, from a comparative perspective, allows identification of shared versus disease-specific metabolic signatures across neurodegenerative conditions, regional metabolic dysfunction, and network-level changes. Ultimately, this provides a rationale for metabolic and functional network-based biomarkers that predict disease progression by tracking disease trajectories across brain regions and assessing the degree of specialization or integration of brain networks.

Due to the complexity of this analysis, the metabolic covariance networks comparison will focus on clinical cases of CN and AD compared to preclinical mice of humanized APOE3 and humanized APOE4. For this comparison, metabolic covariance matrices (MCMs) were computed from

18F-FDG SURV data for mice and humans, using the same analysis workflow as in previous studies in our lab.[

18,

21] Then, brain regions were clustered using multiresolution consensus clustering, and, in the same manner, these tasks were performed using the open-source packages: Brain Connectivity Toolbox,[

51] generalized Louvain modularity,[

52] and CovNet.[

18] The metabolic covariance matrices and the results of the multiresolution consensus clustering are shown in

Figure 3.

From the MCMs, males’ cases (

Figure 3.A-D) show a reduction in the number of clusters between CN and AD in humans and between APOE3 and APOE4 in mice, indicating that brain networks become more integrated in the presence of disease (or a risk factor in mice). In contrast, for females (

Figure 3.E-H), the number of clusters follows an opposite trend (increasing), indicating that brain networks become more fractured. Hence, the number of clusters in mice and humans follows the same sex-dependent trends. These data align with results from our previous studies,[

18,

21] and reinforces the notion that brain structures change in response to different risk factors. Although there is no direct one-to-one relationship between brain regions, functionally related regions tend to group. For instance, the mid-temporal gyrus regions (regions 11 to 16) tend to belong to the same cluster in humans, whereas regions related to sensorial inputs (e.g., posterior parietal cortex, secondary somatosensory cortex) tend to cluster together in mice. However, in the presence of disease or risk factors, these regions are broken apart.

At the whole-brain network-level (

Figure 4), similar patterns can be observed across species. For instance, by analyzing the trend of each metric in humans relative to CN, we can discern a “W” pattern relative to disease progression. However, in mice, the comparison needs to be performed between pairs of cohorts (i.e., LOAD1+HFD relative to LOAD1 at 12 months), where the “W” pattern observed in humans can be reconstructed. Consequently, these alterations reveal analogous network organization profiles across species and sexes, with males exhibiting more clustered, dense, and positively connected networks than females (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). This analysis supports the presence of disease-related alterations across both species and establishes a robust framework capable of discerning network-level distinctions between species, consistent across multiple metrics.

In summary, the variations in the number of clusters and network metrics occur across both species, indicating that these changes are disease-related rather than species-related. In addition, these changes can be used to identify similarities in disease progression across species and to monitor changes in disease-related and therapeutic responses within functional regional and brain organization.

3.3. Metabolic Functional Perspective

AD leads to progressive changes in the brain's structure and function, resulting in worsening behavioral and cognitive decline.[

21,

32,

35,

40] As the disease advances, neurodegeneration affects key brain regions (e.g., hippocampus, prefrontal cortex) responsible for memory, executive function, and emotion regulation.[

20,

21,

35,

40] This disruption results in clinical manifestations, including memory deficits, attentional problems, delusions, sleep disturbances, language difficulties, emotional dysregulation, and severe dementia.[

40,

41,

53] These symptoms can be observed at various stages of the disease.[

53]

Transgenic (e.g., APP/PS1, 5XFAD) and LOAD knock-in (e.g., LOAD1, LOAD2) mouse models of AD replicate many of the pathological and behavioral features observed in humans with AD, including amyloid and tau burden,[

3,

19] anxiety-like behaviors,[

3,

19] memory impairment,[

3,

19] social withdrawal[

3,

19], and neuro-metabolic and vascular dysregulation.[

17,

20] However, translating findings from mice to humans is complicated by noteworthy differences between the two species.[

6] These differences encompass variations in brain complexity, reduced cortical layering, and high-order integration levels of network connectivity.[

6,

19,

35] As a result, not all aspects of the diseases are identical, making it challenging to directly map human behavioral syndromes, such as depression and apathy, with their rodent counterparts.[

6,

19] Therefore, cross-species behavioral interpretation complicates translational research since animal behavioral tests can only approximate a fraction of human clinical symptoms.[

6,

19] The lack of this one-to-one correspondence is the primary barrier to preclinical-to-clinical extrapolation, which contributes to translational failures in AD drug development.[7,10-12]

Current research trends using glycolytic metabolism readout have gained prominence as a translational biomarker that links neuronal activity and network integrity in both human and mouse studies.[

18,

40,

54] Although mouse and human brains possess different numbers of anatomical and functional subdivisions, correspondences can still be established at the level of related functional categories, since previous transcriptomic analyses have revealed that many gene co-expressions and biological processes (e.g., energy metabolism, glial activity, and synaptic function) are preserved across species.[

17,

20,

21,

34,

55] As such, mice can be used to model specific AD mechanisms[

3,

19] by comparing functional variations from metabolic-based readouts, rather than behavioral outputs, thus resulting in a translational framework to bridge inter-species gaps by integrating metabolic functional signatures.[

56,

57]

To bridge current limitations, and to compare inter-species functional changes, region set enrichment analysis (RSEA), a technique developed by our lab,[

21] quantitatively detects brain functional changes based on regional metabolic readout variations relative to a reference group. This method works by weighting changes in each region (experimental group minus the reference group) and then linking these changes to functional set enrichment categories (FSEC). [

21] Therefore, RSEA offers a promising way to align inter-species differences in brain function via energy metabolism patterns rather than using raw behavior, since it is not a species-specific technique, as it uses glycolytic metabolism readouts, a validated biomarker of functional brain activity that correlates with neuronal network activity and decline in AD pathology. However, due to species differences, the FSEC between humans and mice are different, where in humans, the FSECs are auditory, autonomics, cognition, emotions, language, memory, motor, sensorial, speech, and visual. By contrast, in mice, the FSECs have been classified into auditory, learning, motor, perception, sensory, integration, and visual based on the brain parcellations of Paxinos-Franklin atlas. Then, using the modules obtained for CN in humans and B6 in mice in the previous section (

Section 3.2,

Figure 3), modular FSEC scores were generated for each experimental group by summing the columns within the corresponding module, per our previous work.[

21] Although several studies have attempted to perform translational mapping between mouse and human brain organization and function;[

35,

58] however, to the best of our knowledge, using RSEA to make this type of comparisons is the first of its kind.

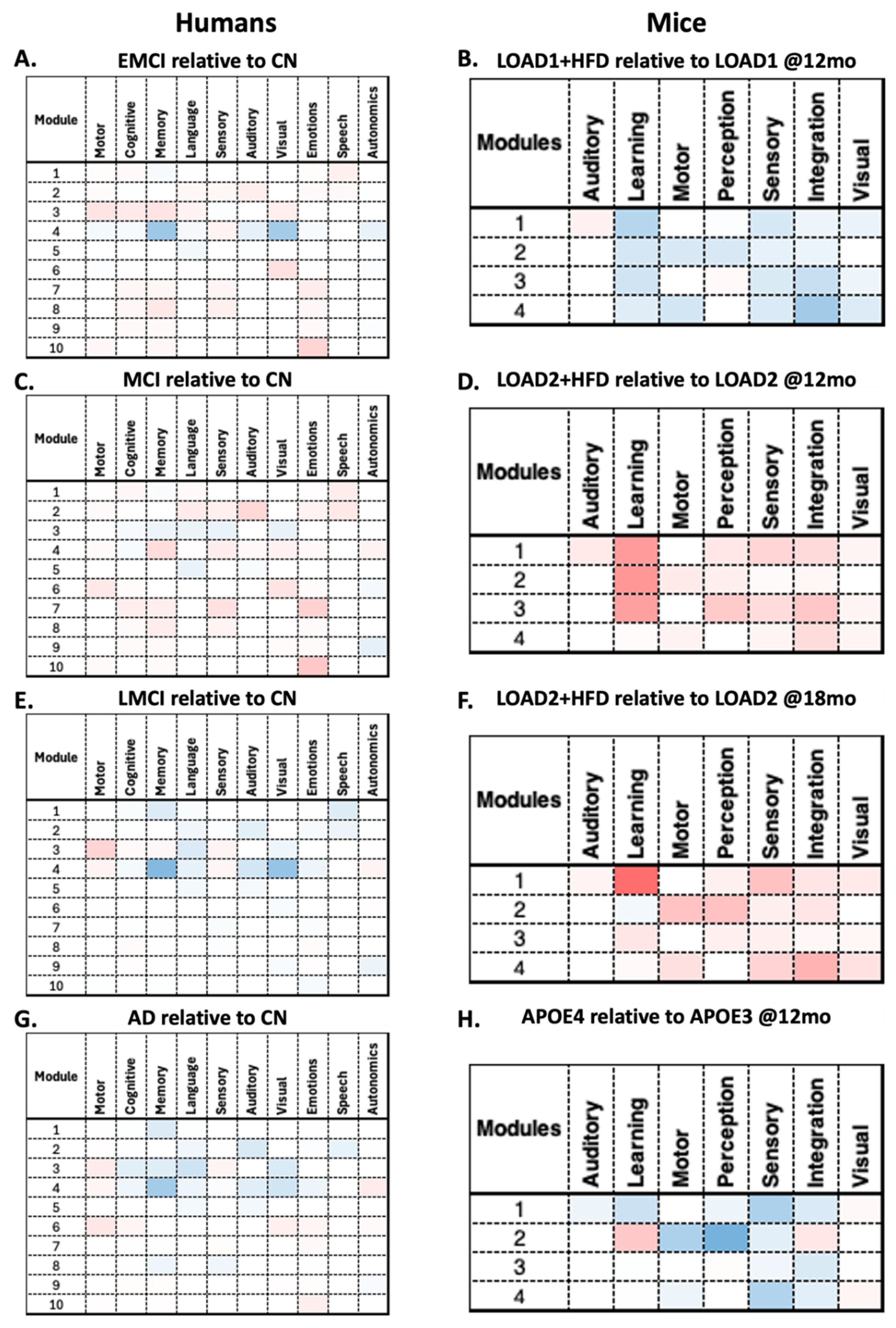

RSEA analysis revealed similar patterns between humans and mice. For instance, males' EMCI relative to CN shows decreases in functional changes in Module 4 across multiple human FSECs (

Figure 5.A). In contrast, mice LOAD1+HFD (12 months) relative to LOAD1 (12 months) show decreases across all modules in the mice's FSECs (

Figure 5.B). For the human MCI relative to CN and the mouse LOAD2+HFD (12 months) relative to LOAD2 (12 months), both show increases across multiple modules (

Figure 5.C-D). In contrast, human LMCI relative to CN and the mouse LOAD2+HFD (18 months) relative to LOAD2 (18 months) show opposite behaviors (

Figure 5.E-F). Finally, human AD relative to CN and the mouse APOE4 (12 months) relative to APOE3 (12 months) show a similar patterns to those of human AD (

Figure 5.G-H). This again illustrates the limitations of mouse models, which cannot capture the complete spectrum of AD, but can replicate disease components for specific phenotypes. On the other hand, RSEA results for females are shown in

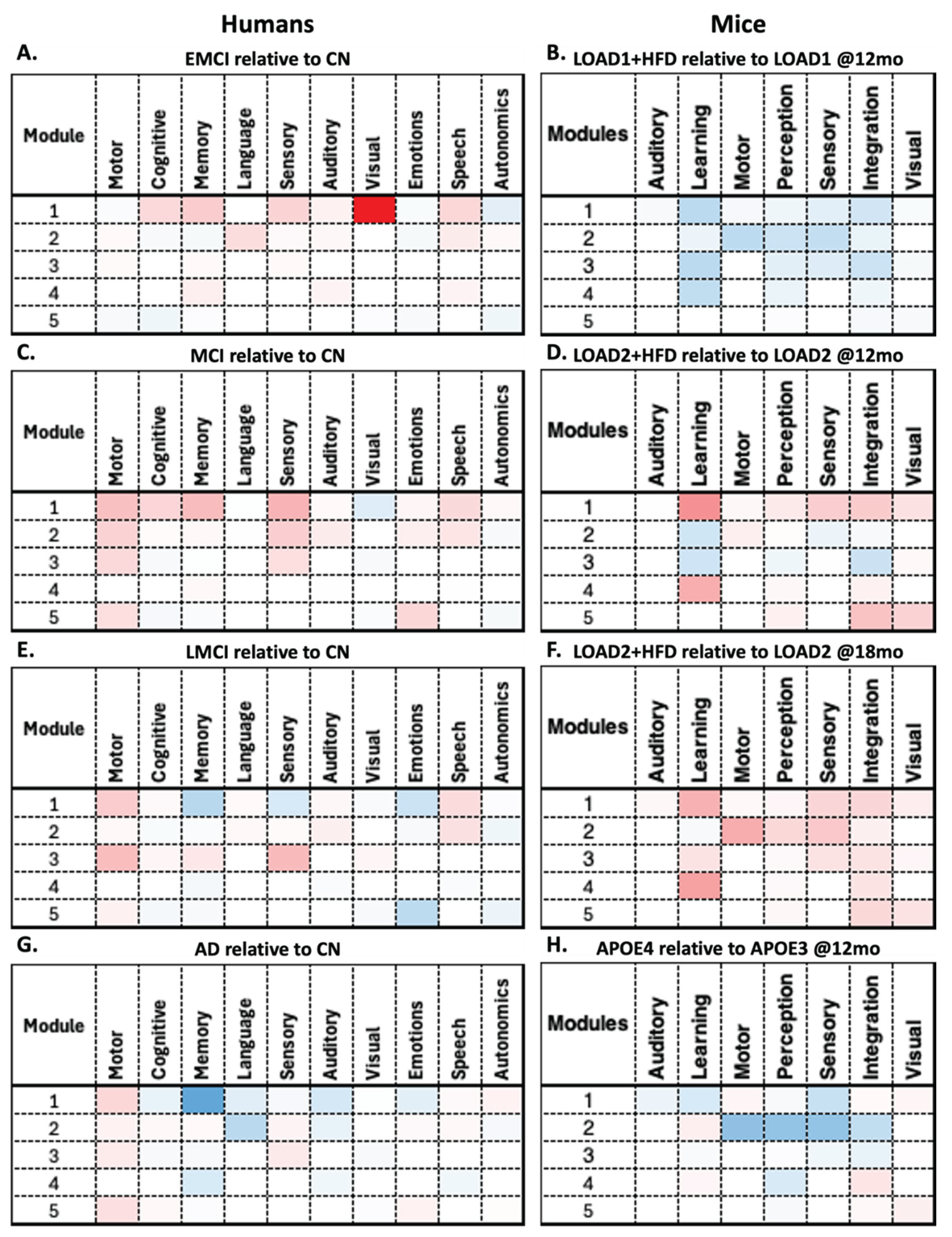

Figure 6, where all comparisons show similar patterns except for human EMCI relative to CN (

Figure 6.A) and LOAD1+HFD (12 months) relative to LOAD1 (12 months) (

Figure 6.B) show opposite trends.

By comparing these findings in detail, RSEA can be used to identify functional changes across comparable categories. For instance, human FSECs motor, memory, cognition, and language follow similar trends to mouse FSECs motor, learning, and perception across multiple modules in both males and females. These findings suggest that these FSECs may be correlated across species (

Figure 6); however, further studies are required to confirm this observation. Moreover, the overall trends between decreases and increases across the different comparisons indicate an energy balance dysregulation, which is supported by the brain reorganization and energy failure theories.[33,38-40] For instance, overall metabolic fluctuations indicate that disease progression starts with a hypo-metabolic phase, followed by a hyper-metabolic phase, which then enters a second hypo-metabolic phase. The intermediate hyper-metabolic phase aligns with previous studies indicating that the brain attempts to balance bioenergetic demands, which it eventually cannot sustain, ultimately leading to energy failure, as expressed in the second hypo-metabolic phase.