Submitted:

31 January 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Transcriptional Networks

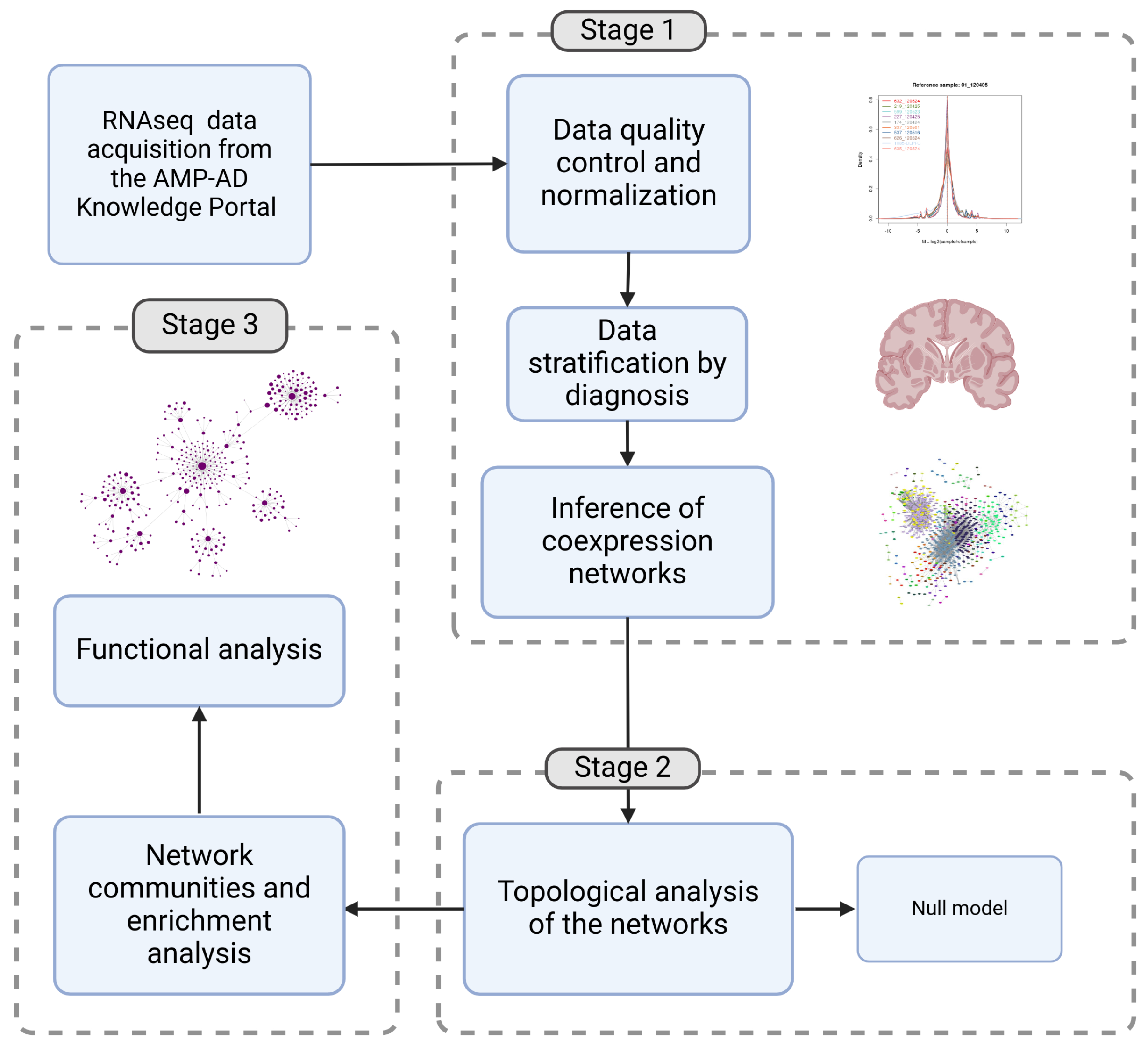

2. Methods

2.1. Data Acquisition and Classification

2.2. Quality Control

2.3. Inference Of Co-Expression Networks

2.4. Topological Analysis and Network Centralities Measure

2.5. Inference of Modular Structure and Functional Analysis

3. Results

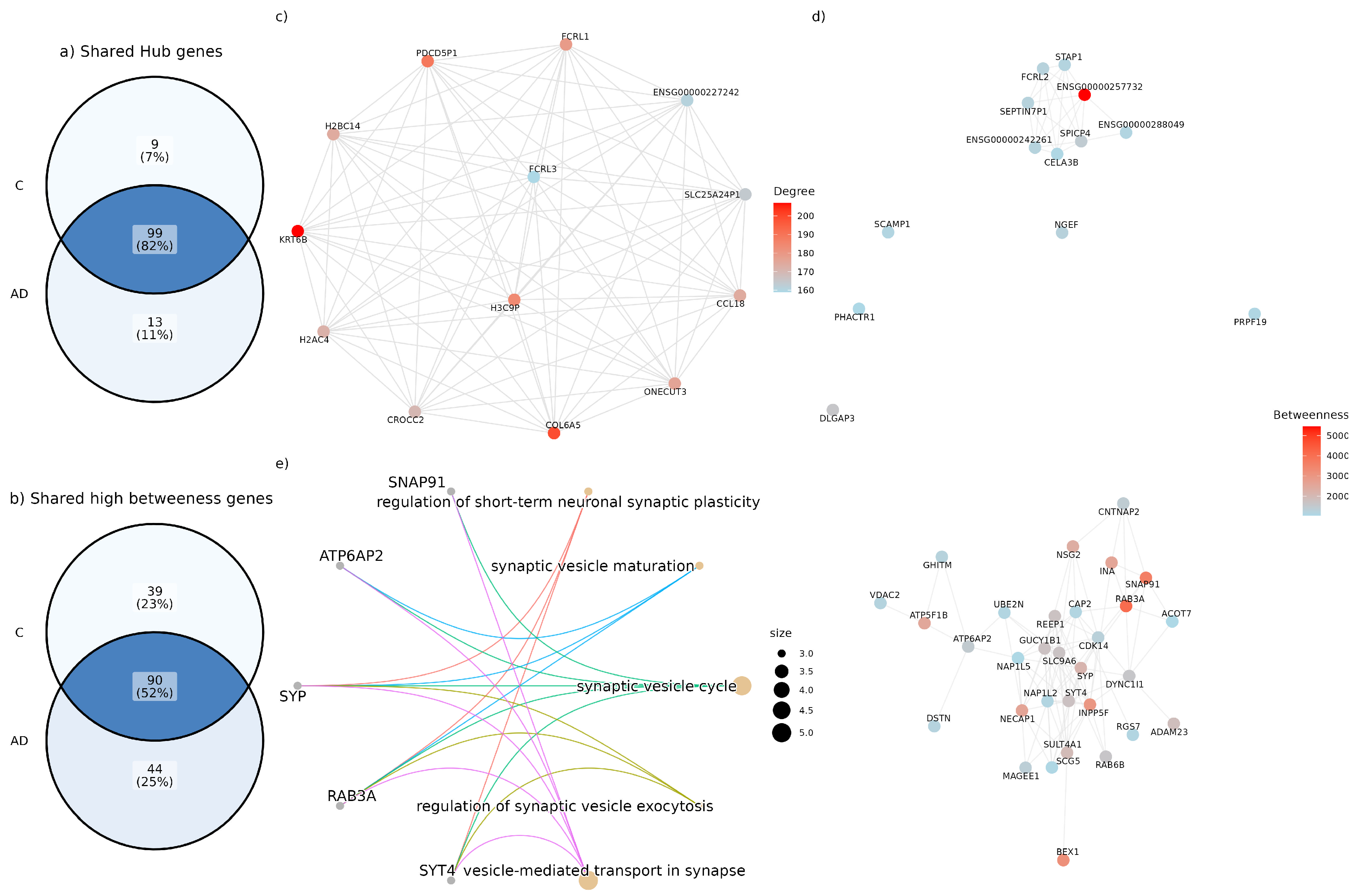

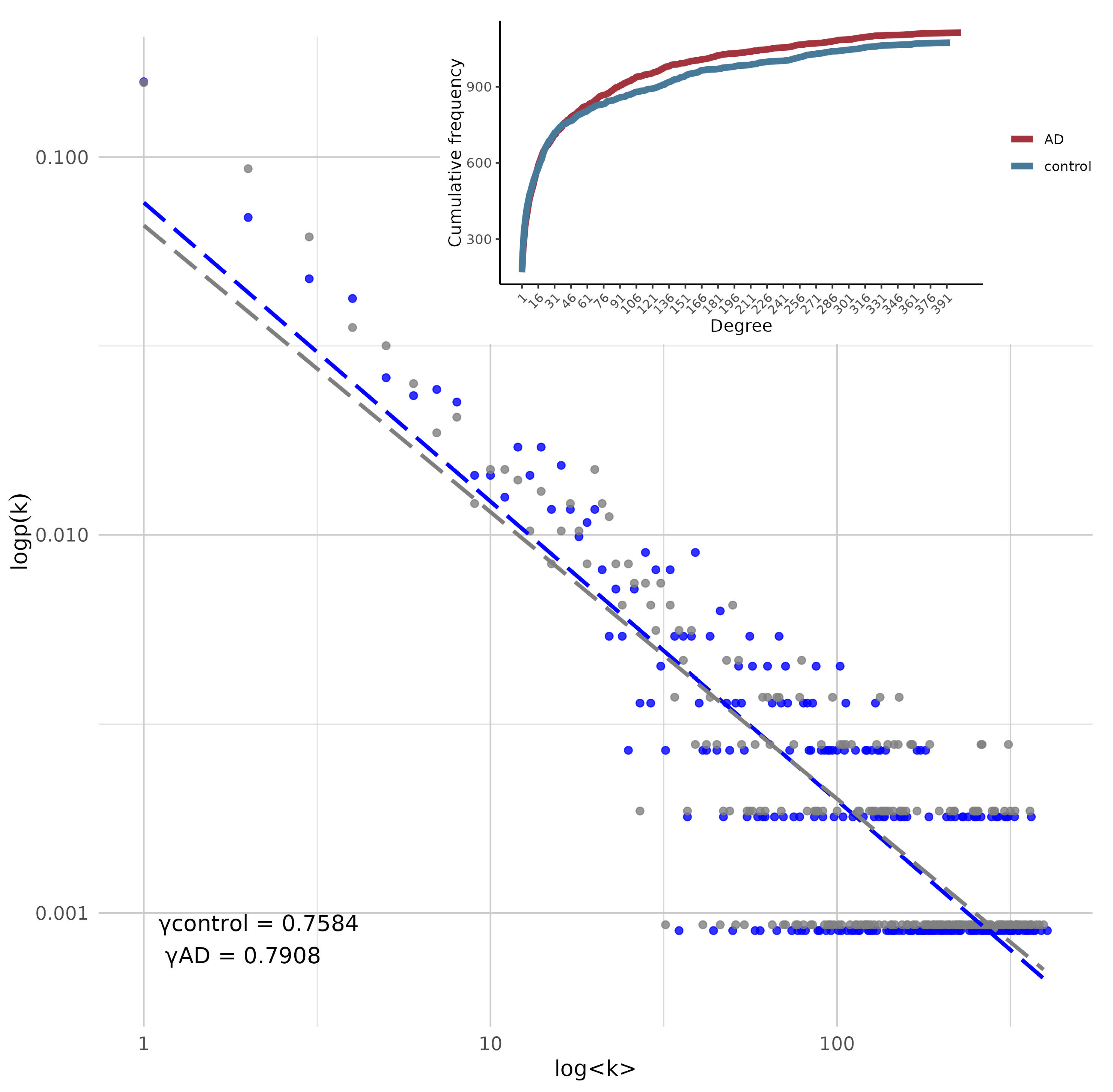

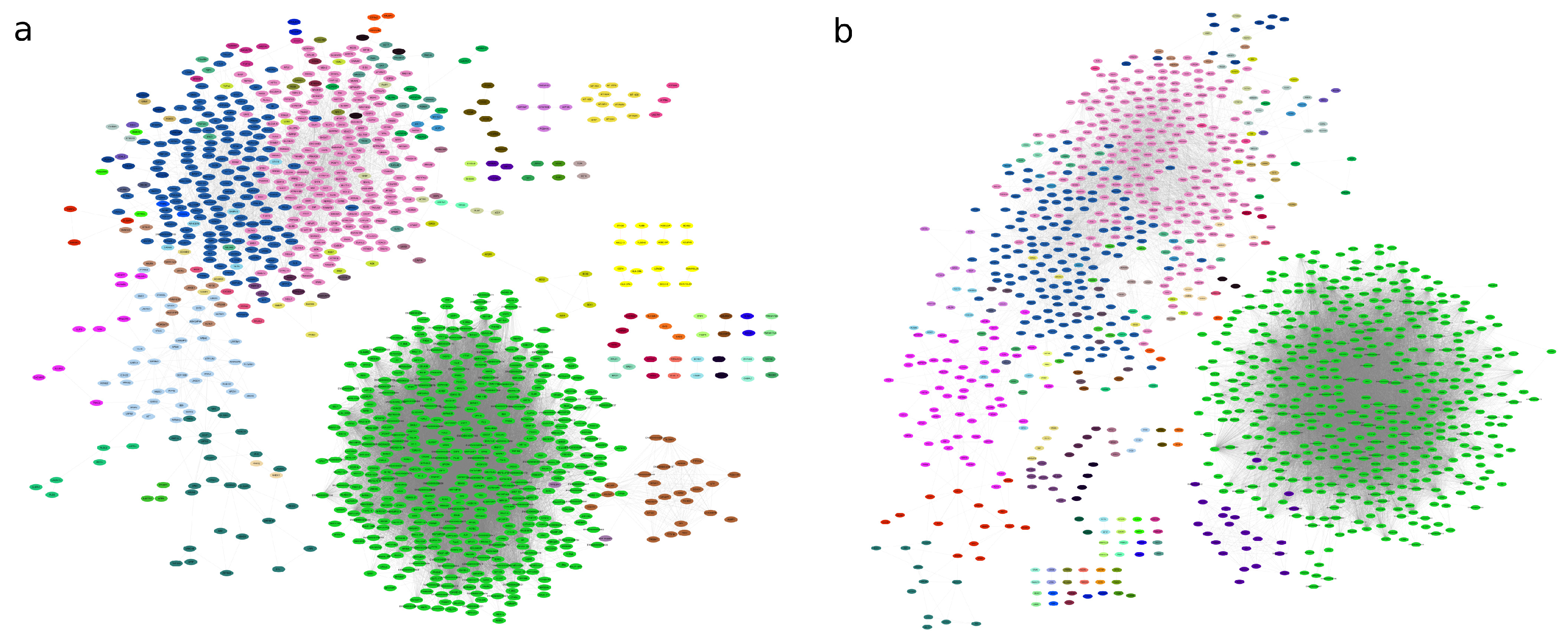

3.1. Mesoscopic Network Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Gene Coexpression Network Alterations in Alzheimer’s Disease: Structural and Connectivity Insights

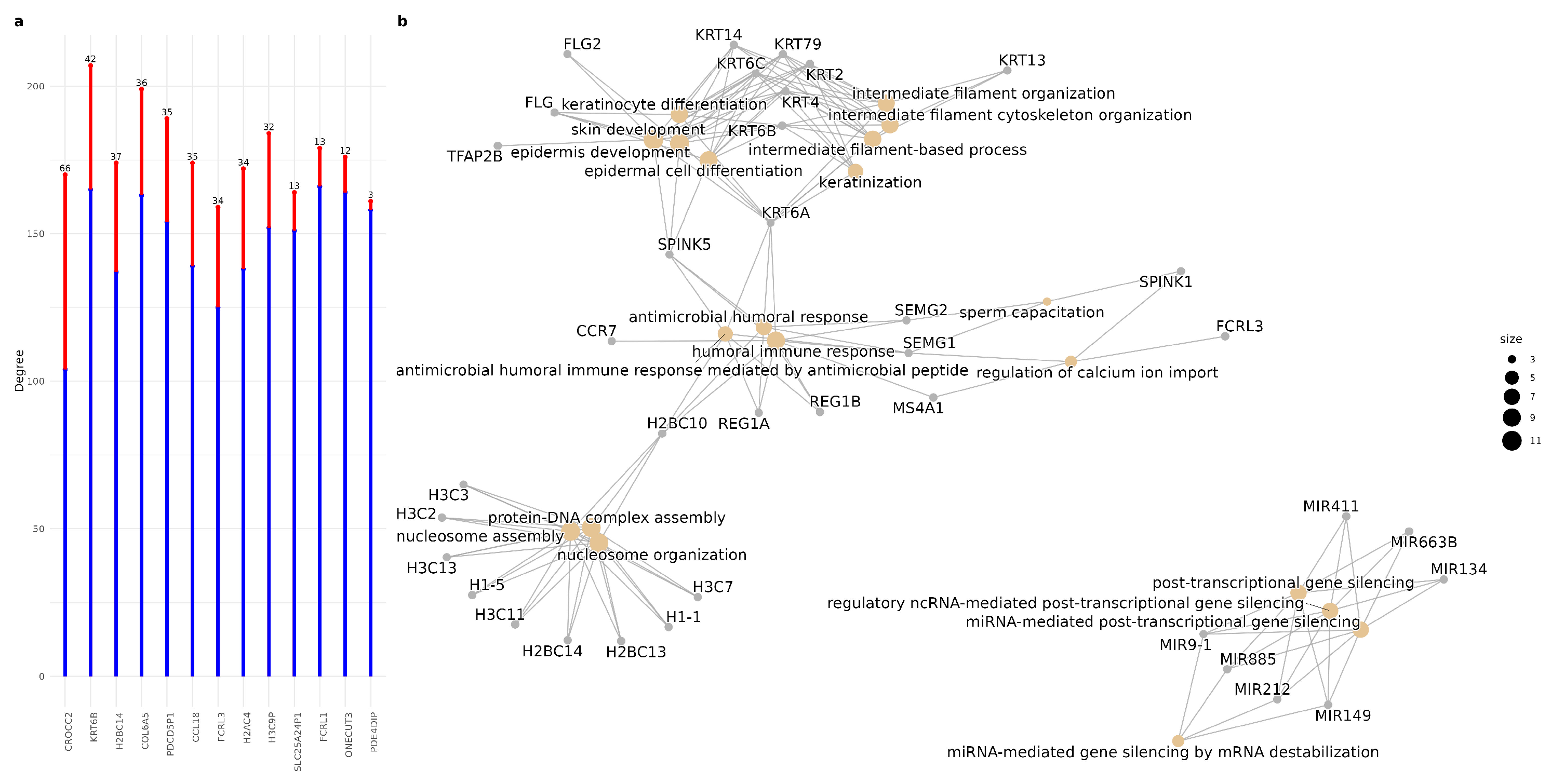

4.2. Functional Insights into Co-Expression Changes in the AD Network: Linking Epigenetic, Cytoskeletal, Immune, and Post-Transcriptional Pathways

4.3. High Betweenness Genes only Present in the Disease Network Are Involved in Diverse Biological Pathways

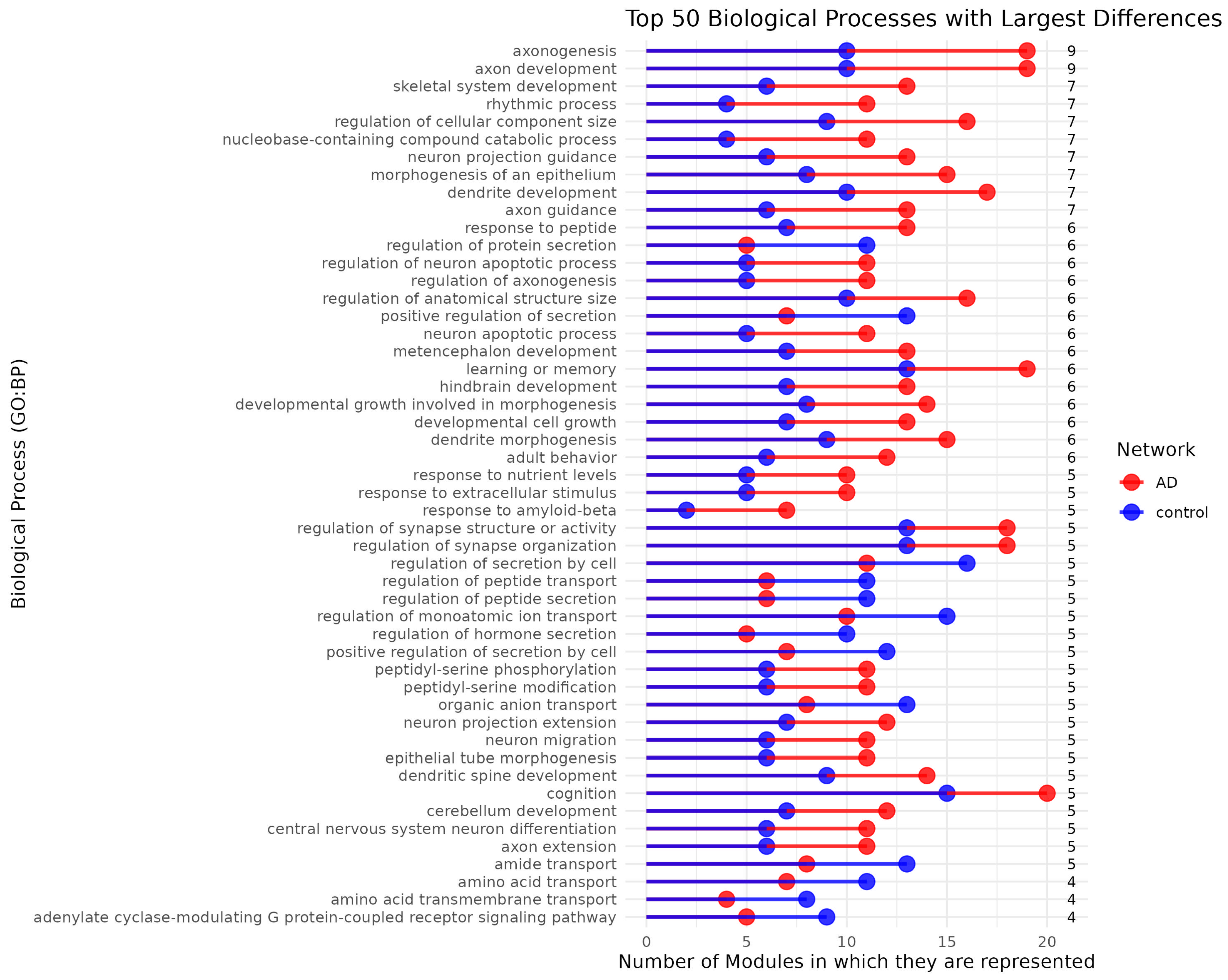

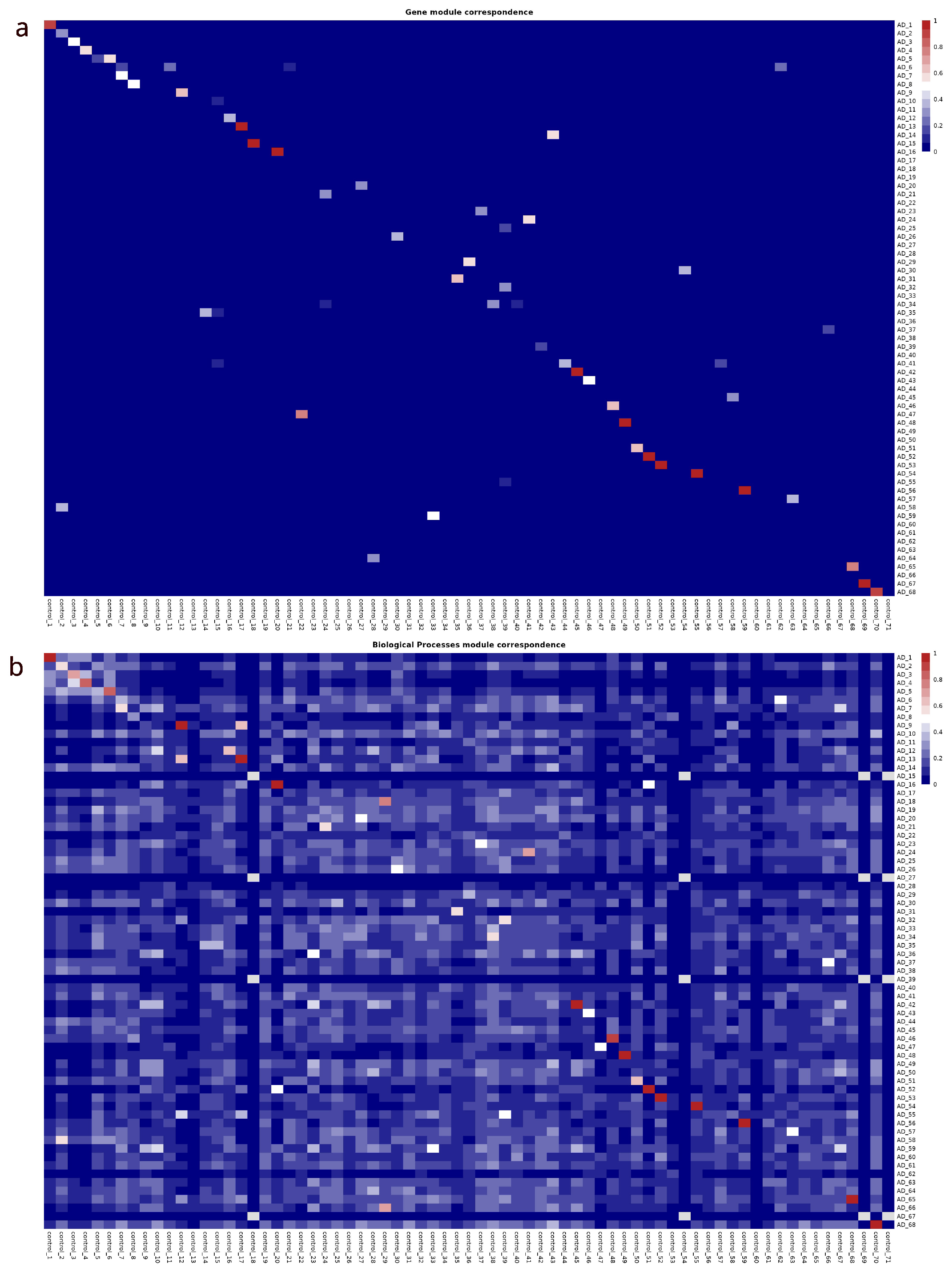

4.4. Network Functional Analysis Show Gene Modular Rearrangement

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aisen, P.S.; Cummings, J.; Jack, C.R.; Morris, J.C.; Sperling, R.; Frölich, L.; Jones, R.W.; Dowsett, S.A.; Matthews, B.R.; Raskin, J.; et al. On the path to 2025: Understanding the Alzheimer’s disease continuum. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy 2017, 9, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingo, T.S.; Lah, J.J.; Levey, A.I.; Cutler, D.J. Autosomal recessive causes likely in early-onset Alzheimer disease. Archives of Neurology 2012, 69, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitakis, Z.; Shah, R.C.; Bennett, D.A. Diagnosis and Management of Dementia: A Review. JAMA 2019, 322, 1589–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerreiro, R.; Bras, J. The age factor in Alzheimer’s disease. Genome Medicine 2015, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, C.F.; Jeste, D.V.; Sachdev, P.S.; Blazer, D.G. Mental health care for older adults: Recent advances and new directions in clinical practice and research. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 336–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, Y.C.; Ho, P.C.; Tu, Y.K.; Jou, I.M.; Tsai, K.J. Lipids and Alzheimer’s Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesi, N.; van der Lee, S.J.; Hulsman, M.; Jansen, I.E.; Stringa, N.; van Schoor, N.M.; Scheltens, P.; van der Flier, W.M.; Huisman, M.; Reinders, M.J.T.; et al. Immune response and endocytosis pathways are associated with the resilience against Alzheimer’s disease. Translational Psychiatry 2020, 10, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.; Lee, H. Correlation between Alzheimer’s disease and type 2 diabetes using non-negative matrix factorization. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 15265, Publisher: Nature Publishing Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzé, R.; Delangre, E.; Tolu, S.; Moreau, M.; Janel, N.; Bailbé, D.; Movassat, J. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Alzheimer’s Disease: Shared Molecular Mechanisms and Potential Common Therapeutic Targets. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 15287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, M.; Alkhayyat, M.; Abou Saleh, M.; Sarmini, M.T.; Singh, A.; Garg, R.; Garg, P.; Mansoor, E.; Padival, R.; Cohen, B.L. Alzheimer Disease Occurs More Frequently In Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Insight From a Nationwide Study. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 2023, 57, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, M.; Sahu, B.; Kaur, H.; Hasler, W.; Prakash, A.; Combs, C.K. Gastrointestinal Changes and Alzheimer’s Disease. Current Alzheimer research 2022, 19, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tini, G.; Scagliola, R.; Monacelli, F.; La Malfa, G.; Porto, I.; Brunelli, C.; Rosa, G.M. Alzheimer’s Disease and Cardiovascular Disease: A Particular Association. Cardiology Research and Practice 2020, 2020, 2617970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.Y.; Gan, Y.H.; Yang, L.; Cheng, W.; Yu, J.T. Depression in Alzheimer’s Disease: Epidemiology, Mechanisms, and Treatment. Biological Psychiatry 2024, 95, 992–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Q.; Chen, L. Associations of Alzheimer’s Disease Neuropathologic Changes with Clinical Presentations of Parkinson’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD 2021, 81, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampel, H.; Nisticò, R.; Seyfried, N.T.; Levey, A.I.; Modeste, E.; Lemercier, P.; Baldacci, F.; Toschi, N.; Garaci, F.; Perry, G.; et al. Omics sciences for systems biology in Alzheimer’s disease: State-of-the-art of the evidence. Ageing Research Reviews 2021, 69, 101346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Pozo, A.; Frosch, M.P.; Masliah, E.; Hyman, B.T. Neuropathological Alterations in Alzheimer Disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine: 2011, 1, a006189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braak, H.; Alafuzoff, I.; Arzberger, T.; Kretzschmar, H.; Del Tredici, K. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathologica 2006, 112, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.S.; Boyle, P.A.; Yu, L.; Barnes, L.L.; Sytsma, J.; Buchman, A.S.; Bennett, D.A.; Schneider, J.A. Temporal course and pathologic basis of unawareness of memory loss in dementia. Neurology 2015, 85, 984–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pàmies-Vilà, R.; Fabregat-Sanjuan, A.; Ros-Alsina, A.; Rigo-Vidal, A.; Pascual-Rubio, V. Analysis of the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex MNI Coordinates. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the XV Ibero-American Congress of Mechanical Engineering; Vizán Idoipe, A.; García Prada, J.C., Eds., Cham, 2023; pp. 132–138. [CrossRef]

- Le Reste, P.J.; Haegelen, C.; Gibaud, B.; Moreau, T.; Morandi, X. Connections of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex with the thalamus: a probabilistic tractography study. Surgical and radiologic anatomy: SRA 2016, 38, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bähner, F.; Demanuele, C.; Schweiger, J.; Gerchen, M.F.; Zamoscik, V.; Ueltzhöffer, K.; Hahn, T.; Meyer, P.; Flor, H.; Durstewitz, D.; et al. Hippocampal–Dorsolateral Prefrontal Coupling as a Species-Conserved Cognitive Mechanism: A Human Translational Imaging Study. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015, 40, 1674–1681, Publisher: Nature Publishing Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Qi, X.L.; Constantinidis, C. Distinct Roles of the Prefrontal and Posterior Parietal Cortices in Response Inhibition. Cell reports 2016, 14, 2765–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbey, A.K.; Koenigs, M.; Grafman, J. Dorsolateral prefrontal contributions to human working memory. Cortex 2013, 49, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertrich, I.; Dietrich, S.; Blum, C.; Ackermann, H. The Role of the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex for Speech and Language Processing. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2021, 15, 645209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rilling, J.K.; Sanfey, A.G. Social Interaction. In Encyclopedia of Neuroscience; Squire, L.R., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, 2009; pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, L.Q. Cognitive and behavioural flexibility: Neural mechanisms and clinical considerations. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2021, 22, 167–179, Publisher: Nature Publishing Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaller, C.P.; Rahm, B.; Spreer, J.; Weiller, C.; Unterrainer, J.M. Dissociable contributions of left and right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in planning. Cerebral Cortex (New York, N.Y.: 1991) 2011, 21, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeso, I.; Herrero, M.T.; Ligneul, R.; Rothwell, J.C.; Jahanshahi, M. A Causal Role for the Right Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex in Avoidance of Risky Choices and Making Advantageous Selections. Neuroscience 2021, 458, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.D.; Nystrom, L.E.; Engell, A.D.; Darley, J.M.; Cohen, J.D. The neural bases of cognitive conflict and control in moral judgment. Neuron 2004, 44, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition ed.; American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Zomorrodi, R.; Ghazala, Z.; Goodman, M.S.; Blumberger, D.M.; Cheam, A.; Fischer, C.; Daskalakis, Z.J.; Mulsant, B.H.; Pollock, B.G.; et al. Extent of Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex Plasticity and Its Association With Working Memory in Patients With Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 1266–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Bonchev, D. A survey of current software for network analysis in molecular biology. Human Genomics 2010, 4, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabási, A.L.; Oltvai, Z.N. Network biology: Understanding the cell’s functional organization. Nature Reviews. Genetics 2004, 5, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, J.M.; Segal, E.; Koller, D.; Kim, S.K. A gene-coexpression network for global discovery of conserved genetic modules. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2003, 302, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.A.; Oldham, M.C.; Geschwind, D.H. A Systems Level Analysis of Transcriptional Changes in Alzheimer’s Disease and Normal Aging. The Journal of Neuroscience 2008, 28, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altaf-Ul-Amin, M.; Afendi, F.M.; Kiboi, S.K.; Kanaya, S. Systems Biology in the Context of Big Data and Networks. BioMed Research International 2014, 2014, 428570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barabasi, A.L.; Albert, R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science (New York, N.Y.) 1999, 286, 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabási, A.L. Network science. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2013, 371, 20120375, Publisher: Royal Society. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Xu, J.; Tian, Y.; Liao, B.; Lang, J.; Lin, H.; Mo, X.; Lu, Q.; Tian, G.; Bing, P. Gene Coexpression Network and Module Analysis across 52 Human Tissues. BioMed Research International 2020, 2020, 6782046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura-García, A.K.; Espinal-Enríquez, J. Pseudogenes in Cancer: State of the Art. Cancers 2023, 15, 4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Pascual, A.; Rocamora-Pérez, G.; Ibanez, L.; Botía, J.A. Targeted co-expression networks for the study of traits. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 16675, Publisher: Nature Publishing Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, F.; Paci, P. Alzheimer’s disease: Insights from a network medicine perspective. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 16846, Publisher: Nature Publishing Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Bp, K.; C R, S.; Saikumar, N.V.; Philip, P.; Narayanan, M. Alzheimer’s disease rewires gene coexpression networks coupling different brain regions. npj Systems Biology and Applications 2024, 10, 1–16, Publisher: Nature Publishing Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.S.; Madaj, Z.; Cheema, C.T.; Kara, B.; Bennett, D.A.; Schneider, J.A.; Gordon, M.N.; Ginsberg, S.D.; Mufson, E.J.; Counts, S.E. Co-expression network analysis of frontal cortex during the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Cerebral Cortex 2022, 32, 5108–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Lin, J.; Zhang, L. The application of weighted gene co-expression network analysis in identifying key modules and hub genes associated with disease status in Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of Translational Medicine 2019, 7, 800–800, Number: 24 Publisher: AME Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D.A.; Buchman, A.S.; Boyle, P.A.; Barnes, L.L.; Wilson, R.S.; Schneider, J.A. Religious Orders Study and Rush Memory and Aging Project. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD 2018, 64, S161–S189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jager, P.L.; Ma, Y.; McCabe, C.; Xu, J.; Vardarajan, B.N.; Felsky, D.; Klein, H.U.; White, C.C.; Peters, M.A.; Lodgson, B.; et al. A multi-omic atlas of the human frontal cortex for aging and Alzheimer’s disease research. Scientific Data 2018, 5, 180142, Publisher: Nature Publishing Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, B.T.; Phelps, C.H.; Beach, T.G.; Bigio, E.H.; Cairns, N.J.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dickson, D.W.; Duyckaerts, C.; Frosch, M.P.; Masliah, E.; et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 2012, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarazona, S.; Furió-Tarí, P.; Turrà, D.; Pietro, A.D.; Nueda, M.J.; Ferrer, A.; Conesa, A. Data quality aware analysis of differential expression in RNA-seq with NOISeq R/Bioc package. Nucleic Acids Research 2015, 43, e140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nueda, M.J.; Ferrer, A.; Conesa, A. ARSyN: A method for the identification and removal of systematic noise in multifactorial time course microarray experiments. Biostatistics (Oxford, England) 2012, 13, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, M.D.; Oshlack, A. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biology 2010, 11, R25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, C.; Liu, C. Approximating discrete probability distributions with dependence trees. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1968, 14, 462–467, Conference Name: IEEE Transactionson Information Theory. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steuer, R.; Kurths, J.; Daub, C.O.; Weise, J.; Selbig, J. The mutual information: Detecting and evaluating dependencies between variables. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2002, 18 Suppl 2, S231–240. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, P. Information-Theoretic Variable Selection and Network Inference from Microarray Data 2008.

- Margolin, A.A.; Nemenman, I.; Basso, K.; Wiggins, C.; Stolovitzky, G.; Favera, R.D.; Califano, A. ARACNE: An Algorithm for the Reconstruction of Gene Regulatory Networks in a Mammalian Cellular Context. BMC Bioinformatics 2006, 7, S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csardi, G.; Nepusz, T. The Igraph Software Package for Complex Network Research. InterJournal 2005, Complex Systems, 1695. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Research 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schank, T.; Wagner, D. Approximating Clustering Coefficient and Transitivity. Journal of Graph Algorithms and Applications 2005, 9, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, S.; Faust, K. Social network analysis: Methods and applications; Social network analysis: Methods and applications, Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, US, 1994. Pages: Xxxi, 825. [CrossRef]

- Barrat, A.; Barthélemy, M.; Pastor-Satorras, R.; Vespignani, A. The architecture of complex weighted networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2004, 101, 3747–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papin, J.A.; Reed, J.L.; Palsson, B.O. Hierarchical thinking in network biology: The unbiased modularization of biochemical networks. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2004, 29, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosvall, M.; Axelsson, D.; Bergstrom, C.T. The map equation. The European Physical Journal Special Topics 2009, 178, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlin, L.; Edler, D.; Lancichinetti, A.; Rosvall, M. Community Detection and Visualization of Networks with the Map Equation Framework. In Measuring Scholarly Impact: Methods and Practice; Ding, Y., Rousseau, R., Wolfram, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2014; pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancichinetti, A.; Fortunato, S.; Radicchi, F. Benchmark graphs for testing community detection algorithms. Physical Review E 2008, 78, 046110, Publisher: American Physical Society. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Anda-Jáuregui, G. Guideline for comparing functional enrichment of biological network modular structures. Applied Network Science 2019, 4, 1–17, Number: 1 Publisher: SpringerOpen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, C.L.; Ramaswami, G.; Pembroke, W.G.; Muller, S.; Pintacuda, G.; Saha, A.; Parsana, P.; Battle, A.; Lage, K.; Geschwind, D.H. Co-expression network architecture reveals the brain-wide and multi-regional basis of disease susceptibility. Nature neuroscience 2021, 24, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poliseno, L. Pseudogenes: Newly discovered players in human cancer. Science Signaling 2012, 5, re5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, V.; Esposito, R.; Aprile, M.; Ciccodicola, A. Non-coding RNA and pseudogenes in neurodegenerative diseases: “The (un)Usual Suspects”. Frontiers in Genetics 2012, 3, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zong, Y.; Zhu, L.; Wang, W.; Han, Y. Chemokines in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2023, 15, 1047810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.J.; Ren, Y.; Yan, Z. Epigenomic analysis of Alzheimer’s disease brains reveals diminished CTCF binding on genes involved in synaptic organization. Neurobiology of Disease 2023, 184, 106192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.Y.; Xiong, L.Y.; Mori-Fegan, D.K.; Noor, S.; Chenoweth, M.J.; Mirza, S.S.; Masellis, M.; Black, S.E.; Swardfager, W.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Relationships between polymorphisms in keratin genes and Alzheimer’s disease phenotypes. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2023, 19, e074162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richens, J.L.; Spencer, H.L.; Butler, M.; Cantlay, F.; Vere, K.A.; Bajaj, N.; Morgan, K.; O’Shea, P. Rationalising the role of Keratin 9 as a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 22962, Publisher: Nature Publishing Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moll, R.; Divo, M.; Langbein, L. The human keratins: Biology and pathology. Histochemistry and Cell Biology 2008, 129, 705–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Yu, H.; Cheng, Y.; Han, J.; Li, K.; Zhuang, J.; Lv, Q.; Yang, X.; Yang, H. Bladder cancer-derived exosomal KRT6B promotes invasion and metastasis by inducing EMT and regulating the immune microenvironment. Journal of Translational Medicine 2022, 20, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moir, R.D.; Lathe, R.; Tanzi, R.E. The antimicrobial protection hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association 2018, 14, 1602–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojtechova, I.; Machacek, T.; Kristofikova, Z.; Stuchlik, A.; Petrasek, T. Infectious origin of Alzheimer’s disease: Amyloid beta as a component of brain antimicrobial immunity. PLOS Pathogens 2022, 18, e1010929, Publisher: Public Library of Science. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Atluri, V.; Kaushik, A.; Yndart, A.; Nair, M. Alzheimer’s disease: Pathogenesis, diagnostics, and therapeutics. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 5541–5554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roedl, D.; Traidl-Hoffmann, C.; Ring, J.; Behrendt, H.; Braun-Falco, M. Serine protease inhibitor lymphoepithelial Kazal type-related inhibitor tends to be decreased in atopic dermatitis. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology: JEADV 2009, 23, 1263–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, S.M.; Leube, R.E.; Schwarz, N. Keratin 6a mutations lead to impaired mitochondrial quality control. The British Journal of Dermatology 2020, 182, 636–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallunki, T.; Su, B.; Tsigelny, I.; Sluss, H.K.; Dérijard, B.; Moore, G.; Davis, R.; Karin, M. JNK2 contains a specificity-determining region responsible for efficient c-Jun binding and phosphorylation. Genes & development 1994, 8, 2996–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenga, S. Conformational mutations in neuroserpin and familial dementias. Lancet (London, England) 2002, 360, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.L.; Shrimpton, A.E.; Carrell, R.W.; Lomas, D.A.; Gerhard, L.; Baumann, B.; Lawrence, D.A.; Yepes, M.; Kim, T.S.; Ghetti, B.; et al. Association between conformational mutations in neuroserpin and onset and severity of dementia. Lancet (London, England) 2002, 359, 2242–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yepes, M.; Sandkvist, M.; Wong, M.K.K.; Coleman, T.A.; Smith, E.; Cohan, S.L.; Lawrence, D.A. Neuroserpin reduces cerebral infarct volume and protects neurons from ischemia-induced apoptosis. Blood 2000, 96, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-González, R.; Sobrino, T.; Rodríguez-Yáñez, M.; Millán, M.; Brea, D.; Miranda, E.; Moldes, O.; Pérez, J.; Lomas, D.A.; Leira, R.; et al. Association between neuroserpin and molecular markers of brain damage in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Journal of Translational Medicine 2011, 9, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, P.K.; Jackson, M.B. The Functional Significance of Synaptotagmin Diversity in Neuroendocrine Secretion. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingarten, D.J.; Shrestha, A.; Juda-Nelson, K.; Kissiwaa, S.A.; Spruston, E.; Jackman, S.L. Fast resupply of synaptic vesicles requires synaptotagmin-3. Nature 2022, 611, 320–325, Publisher: Nature Publishing Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Chen, S.; Nie, Q.; Xue, Q.; Fan, H.; Wang, Y.; Fan, S.; Zhu, J.; Shen, H.; Li, H.; et al. Synaptotagmin-3 interactions with GluA2 mediate brain damage and impair functional recovery in stroke. Cell Reports 2023, 42, 112233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chum, P.P.; Bishara, M.A.; Solis, S.R.; Behringer, E.J. Cerebrovascular miRNAs Track Early Development of Alzheimer’s Disease and Target Molecular Markers of Angiogenesis and Blood Flow Regulation. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD 2024, 99, S187–S234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esashi, E.; Bao, M.; Wang, Y.H.; Cao, W.; Liu, Y.J. PACSIN1 regulates the TLR7/9-mediated type I interferon response in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. European Journal of Immunology 2012, 42, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floyd, S.R.; Porro, E.B.; Slepnev, V.I.; Ochoa, G.C.; Tsai, L.H.; De Camilli, P. Amphiphysin 1 binds the cyclin-dependent kinase (cdk) 5 regulatory subunit p35 and is phosphorylated by cdk5 and cdc2. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 8104–8110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alwadei, A.H.; Benini, R.; Mahmoud, A.; Alasmari, A.; Kamsteeg, E.J.; Alfadhel, M. Loss-of-function mutation in RUSC2 causes intellectual disability and secondary microcephaly. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 2016, 58, 1317–1322. _eprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, K.C.; de Graaf, B.M.; Syrimis, A.; Zhao, Y.; Brosens, E.; Mancini, G.M.S.; Schot, R.; Halley, D.; Wilke, M.; Vøllo, A.; et al. Goldberg–Shprintzen syndrome is determined by the absence, or reduced expression levels, of KIFBP. Human Mutation 2020, 41, 1906–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, D.; Pallares, L.F.; Ayroles, J.F. Reassessing the modularity of gene co-expression networks using the Stochastic Block Model. PLOS Computational Biology 2024, 20, e1012300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Mendoza, L.; Monzon-Sandoval, J.; Urrutia, A.O.; Gutierrez, H. Emergence of co-expression in gene regulatory networks. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hao, X.; Hu, Z.; Tian, J.; Shi, J.; Ma, D.; Guo, M.; Li, S.; Zuo, C.; Liang, Y.; et al. Microvascular and cellular dysfunctions in Alzheimer’s disease: an integrative analysis perspective. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 20944, Publisher: Nature Publishing Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cortés, D.; Hernández-Lemus, E.; Espinal-Enríquez, J. Luminal A Breast Cancer Co-expression Network: Structural and Functional Alterations. Frontiers in Genetics 2021, 12. Publisher: Frontiers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Control network | AD network | |

|---|---|---|

| Total genes | 1074 | 1113 |

| Number of edges | 28160 | 28160 |

| Network diameter | 12 | 13 |

| Global transitivity (Clustering coefficient) | 0.6252799 | 0.5956005 |

| Edges similitude (by Jaccard index) | 68.39% | |

| Number of genes in largest connected component | 529 | 568 |

| Number of modules (Infomap partition) | 71 | 68 |

| Scaling exponent | 0.7584 | 0.7908 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).