1. Introduction

The use of assisted reproductive technologies to increase the population and enhance the genetic quality of Thai beef cattle is essential for improving their economic value and preserving indigenous breeds [

1]. Among these technologies, in vitro embryo production (IVEP) stands out as particularly effective. The IVEP process involves several key steps, starting with oocyte collection either from ovaries obtained at slaughterhouses or through ovum pick-up (OPU) from live animals. The collected oocytes undergo in vitro maturation (IVM), followed by in vitro fertilization (IVF) and in vitro culture (IVC) until they develop to the morula or blastocyst stage. These embryos can then be transferred to synchronized recipients or cryopreserved for future use [

2]. Several factors influence oocyte quality including donor characteristics, nutritional status, and environmental conditions, which collectively affect follicular development and oocyte competence [

3]. Another critical factor is oxidative stress, which affects oocyte quality and the progression of oocyte maturation and pre-implantation embryo development. This stress can occur at any stages from the pre-culture phase through the entire IVC process [

4].

Oxidative stress in oocytes can arise from both endogenous and exogenous sources [

5]. Endogenous factors are primarily linked to the physiological status of the donor animal. After slaughter, ischemia and oxygen deprivation in ovarian tissues can impair mitochondrial function [

6], leading to excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide anion (O₂⁻•), hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), and hydroxyl radicals (OH•). This imbalance triggers lipid, protein, and DNA oxidation [

4] and disrupts microtubule polymerization within the spindle apparatus, thereby hindering proper meiotic progression and maturation [

7]. The ROS production can persist throughout all stages of IVEP, starting approximately 4 hours after IVM and peaking after 12 hours of culture [

8]. This increase coincides with the oocyte’s heightened ATP demand during critical processes, such as spindle formation, chromosome segregation, and cell division [

9]. Exogenous factors include environmental and handling conditions during in vitro procedures. Elevated oxygen tension compared to in vivo conditions, temperature fluctuations, light exposure during oocyte handling, and trace transition metals (Fe²⁺, Cu²⁺) in culture media can enhance ROS generation via Fenton-type reactions [

10].

Given the detrimental effects of oxidative stress on oocyte quality and subsequent embryo development, establishing a reliable in vitro oxidative stress model is essential. Among the various agents used to induce oxidative stress, hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) is one of the most employed agents due to its stability, ability to permeate cell membranes, and capacity to generate secondary reactive species such as hydroxyl radicals via Fenton reactions [

11].

However, the concentration of H₂O₂ used is a critical factor. While physiological levels of ROS are known to play a regulatory role in meiotic resumption and oocyte maturation. Excessive ROS can impair chromosomal alignment, damage the spindle apparatus, promote apoptosis, and ultimately compromise oocyte quality and embryo developmental [

12]. For example, Zhang et al. [

7] reported that 50 – 100 µM H₂O₂ effectively induced mitochondrial dysfunction and spindle disorganization in mouse oocytes in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Therefore, it is essential to select an appropriate H₂O₂ concentration that is high enough to induce a measurable cellular response without causing irreversible damage or cell death, ensuring that the model reflects physiologically relevant stress conditions. In addition, the 1-hour period of exposure was chosen as a fixed time point based on evidence that oxidative injury induced by H₂O₂ is both dose- and time-dependent [

13]. This fixed duration allowed the assessment of concentration-dependent effects, assuming that a given time, an optimal H₂O₂ concentration can induce measurable oxidative stress without causing any irreversible damages. The establishment of such an optimized oxidative stress model provides a valuable experimental framework for future studies on evaluating the efficacy of antioxidant compounds. By identifying a H₂O₂ concentration that induces a controlled reduction in nuclear maturation—specifically, a measurable decline in the proportion of oocytes reaching the MII stage—this model can reliably simulate oxidative challenge under in vitro conditions. Moreover, the use of a pre-IVM exposure design is particularly relevant because it mimics the transient oxidative stress that oocytes may naturally encounter during collection, transportation, or handling prior to culture. This approach allows for the consistent and reproducible assessment of protective agents, thereby enhancing the accuracy and interpretability of antioxidant efficacy studies in bovine oocytes. Based on this rationale, the present study aimed to determine the optimal H₂O₂ concentration for inducing oxidative stress in bovine oocytes during the pre-IVM phase.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ovaries Collection and Handling

The oocytes used in this study were collected from ovaries of intact mature female cattle slaughtered at three slaughterhouses in Nakhon Pathom province. Oocyte collection was conducted between June and September 2025. The bovine ovaries were transported to the laboratory within 2 hours of collection. During transportation, the ovaries were maintained at 30–35 °C in 0.9% NaCl supplemented with 100 IU/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin sulfate (Hyclone, USA) to minimize microbial contamination.

2.2. Cumulus-Oocyte Complexes Recovery and Selection

Upon arrival at the laboratory, ovaries were washed three times with pre-warmed (37 °C) transport medium. Cumulus–oocyte complexes (COCs) were then aspirated from follicles with measuring 2-5 mm in diameter using an 18-gauge needle attached to a 10-mL disposable syringe. Only COCs of grade 1 and 2 quality, characterized of cumulus–oocyte complexes were performed in accordance with the guidelines published by the International Embryo Technology Society (IETS Manual, 4th ed.)

2.3. Induction of Oxidative Stress and In vitro Maturation

Prior to IVM, COCs were randomly allocated (block-randomized by ovary) into four experimental groups based on the intended H₂O₂ concentration: 0 µM (control), 50 µM, 75 µM, and 100 µM. Each treatment group was conducted in five independent replicates (n = 5), using oocytes collected from different ovaries for each replicate. Approximately 20 to 22 COCs were allocated to each treatment group per replicate. All groups were transferred using a mouth pipette into a collecting medium composed of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone™, Cytiva, USA), 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (HyClone™, Cytiva, USA). For the H₂O₂-treated groups (50, 75, and 100 µM), hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂; 30% w/w analytical grade, ACS reagent, Fisher Scientific, USA) was freshly added to the collecting medium to achieve the target final concentrations. The COCs were then incubated at 38.5 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO₂ for 1 hour to induce oxidative stress. The control group was handled identically except without the addition of H₂O₂. Following the treatment period, COCs from all groups were washed three times in maturation medium to remove residual H₂O₂ and then selected COCs were placed into 50-µL drops of maturation medium at a ratio of 10 oocytes per drop. The oocytes were then cultured at 38.5 °C under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO₂ in air for 23 hours. The maturation medium was based on Medium-199 (M-199; Cytiva, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 IU/mL follicle-stimulating hormone (Folligon; Intervet, Netherlands), 10 IU/mL human chorionic gonadotropin (Chorulon; Intervet, Netherlands), 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin sulfate (HyClone™, Cytiva, USA). All media were pre-equilibrated for 2 hours in a humidified CO₂ incubator prior to use.

2.4. Aceto-Orcein Staining

Following incubation, cumulus cells were removed by repeated pipetting in PBS containing 0.25% hyaluronidase (Medchem Express, USA). The denuded oocytes were then fixed in methanol: acetic acid (1:3 v/v) for 48 hours. After fixation, oocytes were stained with 2% aceto-orcein (prepared in 45% acetic acid) for 10 minutes. The nuclear maturation stage of each oocyte was subsequent assessed under a phase-contrast microscope (Olympus CX22LED, Japan) at 400 × total magnification.

2.5. Data Analysis

The normality of data distribution was assessed using both Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. All variables satisfied with the assumption of normality. Homogeneity of variance was verified using Levene’s test before conducting further analysis. Comparison between the means among the four studied groups were conducted using one-way ANOVA. Multiple comparisons between each group were evaluated using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test.

3. Results

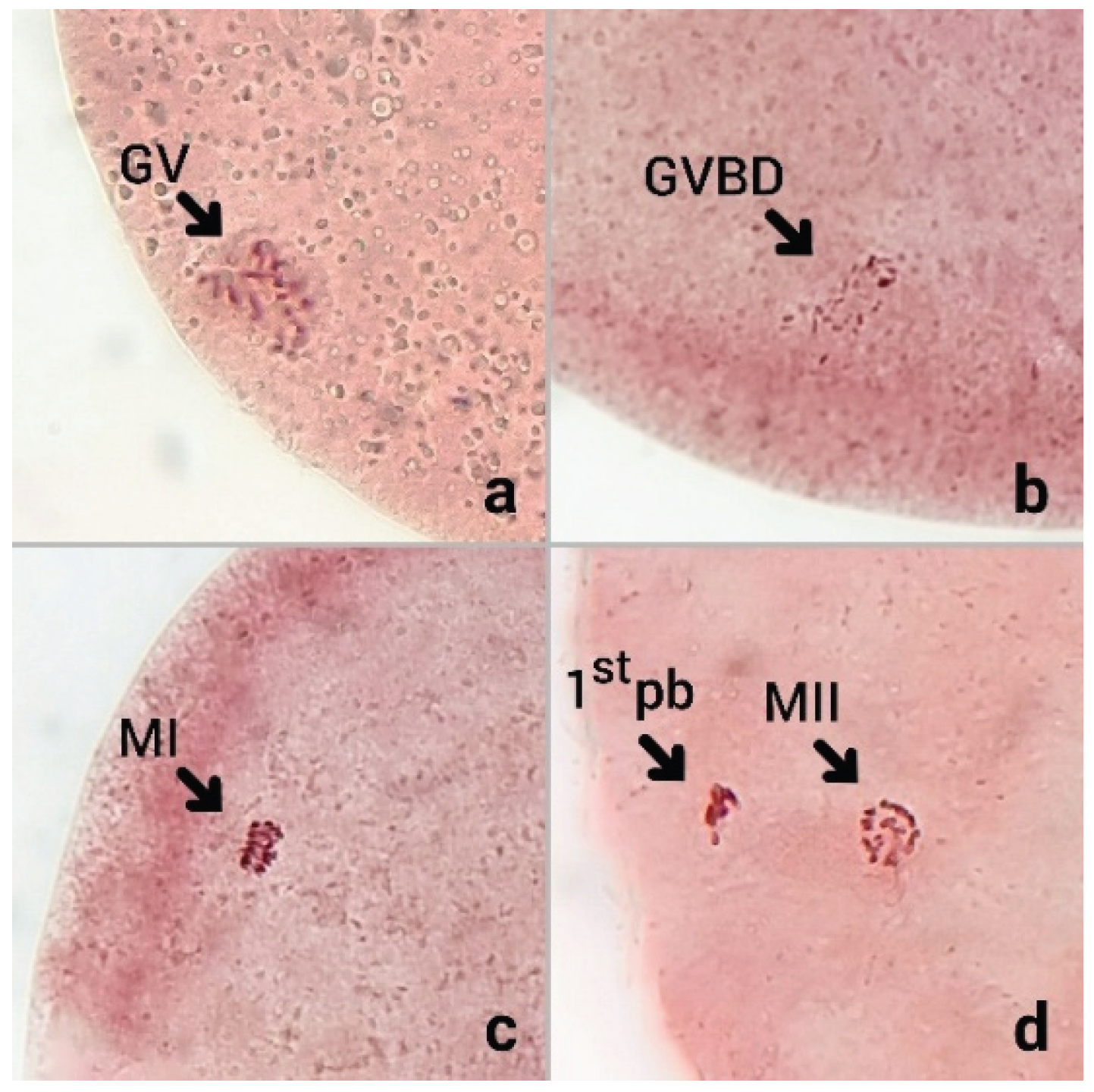

To evaluate the effect of oxidative stress on the nuclear maturation competence of bovine oocytes, COCs were cultured for 23 hours under standard IVM condition, after which the oocytes were assessed for nuclear status. Following fixation and staining with aceto-orcein, chromatin configuration was examined under a phase-contrast microscope. The nuclear maturation stage of each oocyte was classified as shown in

Figure 1.

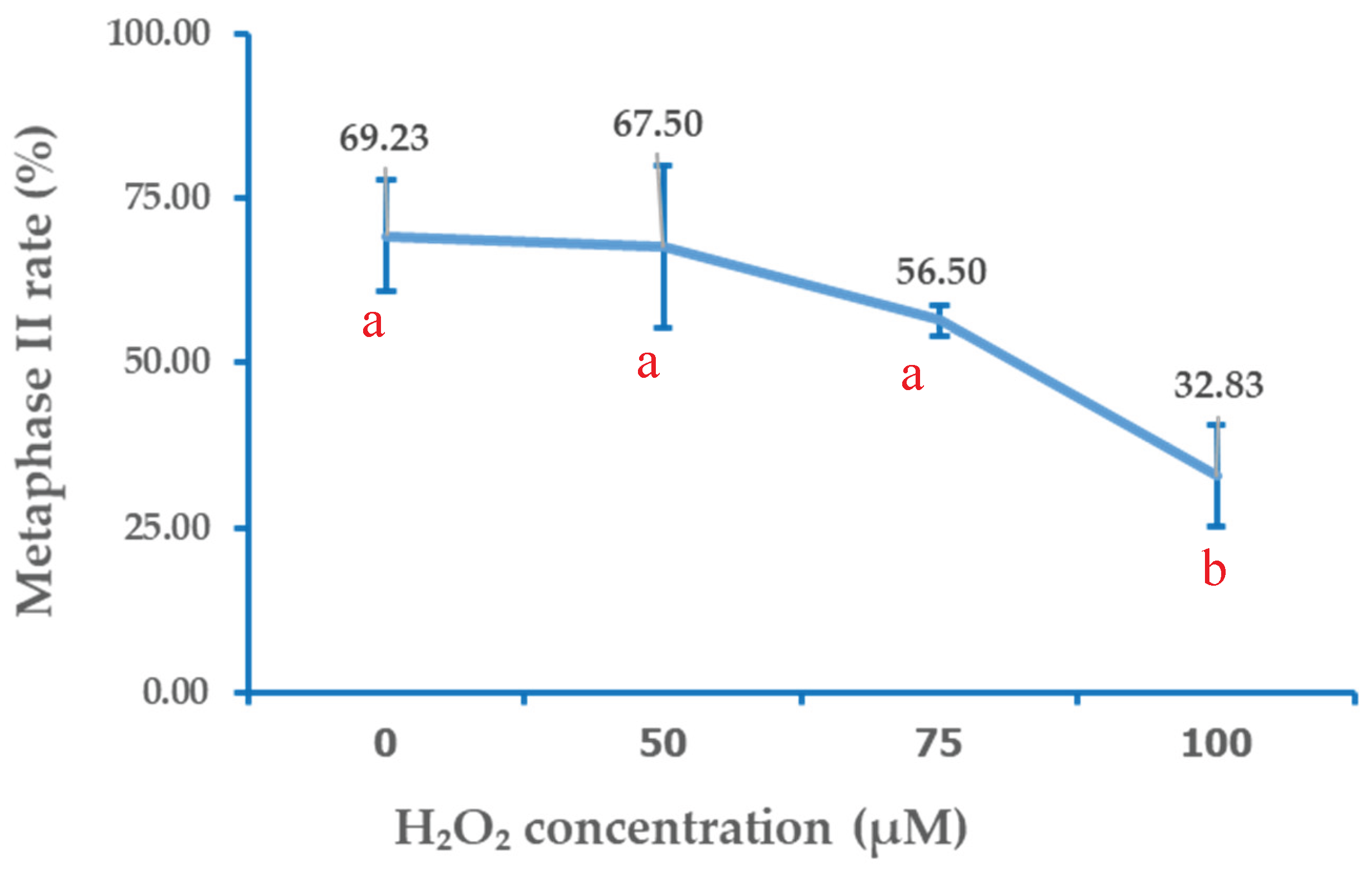

Exposure of bovine oocytes to H₂O₂ during the pre-IVM phase resulted in a dose dependent trend of reduced meiotic maturation, which became statistically significant only at the highest concentration tested. The control group (0 µM) exhibited the highest proportion of oocytes reaching the MII stage (69.23 ± 8.45%), which was not significantly different from the 50 µM (67.5 ± 12.29%) or 75 µM (56.5 ± 2.33%) groups (p > 0.05). In contrast, exposure to 100 µM H₂O₂, significantly reduced the proportion of MII stage oocytes (32.83 ± 7.64%) compared with all other groups (p < 0.05). These findings suggested that mild oxidative stress (75 µM H₂O₂) did not significantly impair nuclear maturation, whereas higher oxidative stress (100 µM) severely compromises meiotic progression. The detailed distributions of oocytes across nuclear maturation stages (GV, GVBD, MI, and MII) for each treatment group are presented in

Table 1, and the corresponding dose–response relationship between H₂O₂ concentration and MII rate is illustrated in

Figure 2.

4. Discussion

In this study, oxidative stress induced by H₂O₂ prior to IVM has been demonstrated a substantial negative impact on oocyte quality, significantly reducing the proportion of oocytes that progressed to the MII stage.

The underlying mechanism by which oxidative stress impairs oocyte maturation is believed to involve disruption of multiple cellular processes, when ROS levels exceed physiological thresholds. Excessive ROS can destabilize the maturation-promoting factor (MPF), premature degradation of cyclin B1, increased cytosolic calcium levels. These alterations activate the calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II – anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (CaMKII–APC/C) pathway, potentially resulting in abnormal meiotic exit or arrest at the MI stage, thereby preventing normal meiotic progression [

14]. In addition, high ROS levels can directly damage key cellular structures by inducing lipid peroxidation of mitochondrial membranes [

15], and causing defects of the spindle apparatus and chromosomal misalignment [

7]. Such damage also activates cell death pathways, including apoptosis and autophagy, via mechanisms involving the ratio of B-cell lymphoma-2-associated X protein (Bax) to B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) signaling, cytochrome c release, and caspase cascade activation [

16]. Collectively, these alterations significantly compromise fertilization competence of the oocyte and its ability to support normal embryo development [

17]. In this study, the exposure of bovine oocytes to increasing H₂O₂ concentrations revealed a dose-dependent trend in meiotic inhibition. The absence of a significant decrease in MII rate at 75 µM H₂O₂ may indicate that this concentration induced only mild oxidative stress, activating endogenous antioxidant defenses (e.g., superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase) without surpassing the oocyte’s compensatory threshold. This partial activation could maintain sufficient MPF stability and mitochondrial function to allow nuclear maturation. In contrast, exposure to 100 µM H₂O₂ resulted in a marked accumulation of germinal vesicle (GV)-stage oocytes, suggesting that excessive ROS interfered with meiotic resumption by inhibiting GVBD initiation. This effect may arise from oxidative modification of CDK1 or other MPF subunits required for GVBD activation, consistent with previous findings that high ROS concentrations suppress cyclin B1 accumulation and block nuclear envelope breakdown [

18].

While the cytotoxic effects of high ROS concentrations are well documented, some studies have also highlighted the physiological role of ROS at low to moderate levels. For example, short-term exposure of mature bovine oocytes to 50–100 µM H₂O₂ for 1 hour has been shown to enhance blastocyst yield and reduced apoptosis in the resulting embryos [

19], the same treatment conditions in this study produced inhibitory effects. This discrepancy likely stems from differences in experimental design, including the developmental stage at exposure and the cellular redox state at the time of treatment. Similarly, low concentrations of H₂O₂ has been reported to induce GVBD in immature oocytes. However, higher concentrations inhibit first polar body extrusion and trigger apoptosis, characterized by elevated Bax expression, DNA fragmentation, and caspase-3 activation [

13]. These findings support the dual role of ROS – not only as a harmful by products of metabolism but also as critical signaling molecules that regulate key events in oocyte maturation. At physiological levels, ROS may contribute to the activation of maturation promoting factors (MPF), facilitating GVBD and progression through meiosis stages to metaphase I and II [

12,

17].

Oxidative stress is known to disrupt mitochondrial function, leading to a decline in ATP production that compromises microtubule polymerization and spindle organization during meiosis. Such mitochondrial dysfunction results in spindle disassembly, chromosome misalignment, and impaired cytoskeletal stability, ultimately reducing oocyte developmental competence [

7]. Consistent with this, oocytes exposed to systemic oxidative stress or metabolic disorders exhibit enlarged and disorganized spindles, misaligned chromosomes, and reduced maturation and blastocyst formation rates, reflecting a direct relationship between cytoskeletal abnormalities and developmental potential [

20]. Proper meiotic division relies on the coordination between mitochondrial activity and microtubule organization, which ensures accurate spindle assembly and chromosome segregation [

21]. Abnormal spindle morphology, resulting from impaired cytoskeletal regulation, has been associated with reduced fertilization potential and a lower rate of euploid blastocyst formation [

22]. Although the present study successfully characterized the oxidative threshold that compromises oocyte maturation, it did not assess intracellular oxidative status or meiotic spindle morphology. Future investigations integrating ROS quantification and spindle imaging are therefore warranted to determine whether oxidative stress at sub-lethal concentrations may still induce subtle cytoskeletal alterations that impair subsequent fertilization or embryo development.

5. Conclusions

This study developed a reproducible in vitro model capable of inducing oxidative stress in bovine oocytes through exposure to hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) prior to the IVM phase. The results demonstrated that treatment with 100 µM H₂O₂ for 1 hour effectively induced a measurable oxidative imbalance without causing irreversible cellular damage, making it an appropriate model for evaluating the efficacy of antioxidant supplementation under controlled stress conditions. Beyond serving as an experimental oxidative challenge, this pre-IVM H₂O₂ exposure model also simulates the oxidative stress that oocytes may experience during pre-culture handling such as follicular aspiration, transportation, or laboratory processing thereby increasing its physiological relevance. This model provides an essential foundation for future investigations aimed at assessing the functional roles of antioxidants in protecting oocytes from oxidative damage. Future research should focus on further refinement of this model by integrating analyses of intracellular redox status, mitochondrial activity, and spindle morphology to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of how oxidative imbalance affects oocyte physiology. Such knowledge will contribute to the development of improved antioxidant supplementation strategies and optimized culture conditions to enhance oocyte competence and increase the efficiency of embryo production in assisted reproductive systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Y., S.T., A.S. and T.R.; methodology, S.Y., S.T., A.S. and T.R.; formal analysis, S.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Y.; writing—review and editing, T.R.; visualization, S.Y.; supervision, T.R.; project administration, S.Y.; funding acquisition, T.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and the APC was funded by Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kasetsart University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for the study because the oocyte samples were obtained from slaughterhouses as part of the routine meat inspection process. The animals were slaughtered for commercial purposes and not specifically for research. Only carcass tissues from animals certified as fit for human consumption by veterinary authorities were used. Therefore, no live animals were handled, subjected to experimental procedures, or exposed to any additional harm or distress for the purpose of this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. No publicly archived datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kasetsart University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with any financial organization regarding the content mentioned in the manuscript.

References

- Bunmee, T.; Chaiwang, N.; Kaewkot, C.; Jaturasitha, S. Current situation and future prospects for beef production in Thailand—A review. Asian-Australasian journal of animal sciences 2018, 31, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, L.; Kjelland, M.; Strøbech, L.; Hyttel, P.; Mermillod, P.; Ross, P. Recent advances in bovine in vitro embryo production: reproductive biotechnology history and methods. Animal 2020, 14, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, J.; De Roos, A.; Mullaart, E.; De Ruigh, L.; Kaal, L.; Vos, P.; Dieleman, S. Factors affecting oocyte quality and quantity in commercial application of embryo technologies in the cattle breeding industry. Theriogenology 2003, 59, 651–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerin, P.; El Mouatassim, S.; Menezo, Y. Oxidative stress and protection against reactive oxygen species in the pre-implantation embryo and its surroundings. Human reproduction update 2001, 7, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Durairajanayagam, D.; Du Plessis, S.S. Utility of antioxidants during assisted reproductive techniques: an evidence based review. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 2014, 12, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zuo, L. Characterization of oxygen radical formation mechanism at early cardiac ischemia. Cell Death & Disease 2013, 4, e787–e787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, X.Q.; Lu, S.; Guo, Y.L.; Ma, X. Deficit of mitochondria-derived ATP during oxidative stress impairs mouse MII oocyte spindles. Cell research 2006, 16, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morado, S.A.; Cetica, P.D.; Beconi, M.T.; Dalvit, G.C. Reactive oxygen species in bovine oocyte maturation in vitro. Reproduction, Fertility and Development 2009, 21, 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappel, S. The role of mitochondria from mature oocyte to viable blastocyst. Obstetrics and gynecology international 2013, 2013, 183024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Heras, S.; Paramio, M.-T. Impact of oxidative stress on oocyte competence for in vitro embryo production programs. Research in Veterinary Science 2020, 132, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransy, C.; Vaz, C.; Lombès, A.; Bouillaud, F. Use of H2O2 to cause oxidative stress, the catalase issue. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21, 9149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kala, M.; Shaikh, M.V.; Nivsarkar, M. Equilibrium between anti--oxidants and reactive oxygen species: a requisite for oocyte development and maturation. Reproductive medicine and biology 2017, 16, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaube, S.; Prasad, P.; Thakur, S.; Shrivastav, T. Hydrogen peroxide modulates meiotic cell cycle and induces morphological features characteristic of apoptosis in rat oocytes cultured in vitro. Apoptosis 2005, 10, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premkumar, K.V.; Chaube, S.K. Increased level of reactive oxygen species persuades postovulatory aging-mediated spontaneous egg activation in rat eggs cultured in vitro. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology-Animal 2016, 52, 576–588. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, D.A.; Tallman, K.A.; Porter, N.A. Free radical oxidation of polyunsaturated lipids: New mechanistic insights and the development of peroxyl radical clocks. Accounts of chemical research 2011, 44, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Khatun, S.; Pandey, A.; Mishra, S.; Chaube, R.; Shrivastav, T.; Chaube, S. Intracellular levels of hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide in oocytes at various stages of meiotic cell cycle and apoptosis. Free radical research 2009, 43, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.N.; Yadav, P.K.; Premkumar, K.V.; Tiwari, M.; Pandey, A.K.; Chaube, S.K. Reactive oxygen species signalling in the deterioration of quality of mammalian oocytes cultured in vitro: protective effect of antioxidants. Cellular Signalling 2024, 117, 111103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Bu, S.; Li, B.; Wang, Q.; Lai, D. Chronic restraint stress disturbs meiotic resumption through APC/C-mediated cyclin B1 excessive degradation in mouse oocytes. Cell Cycle 2018, 17, 1591–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandaele, L.; Thys, M.; Bijttebier, J.; Van Langendonckt, A.; Donnay, I.; Maes, D.; Meyer, E.; Van Soom, A. Short-term exposure to hydrogen peroxide during oocyte maturation improves bovine embryo development. Reproduction 2010, 139, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashibe, S.; Kobayashi, Y.; Toishikawa, S.; Nagao, Y. Effects of maternal liver abnormality on in vitro maturation of bovine oocytes. Zygote 2025, 33, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, E.; Vireque, A.; Adona, P.R.; Meirelles, F.V.; Ferriani, R.A.; Navarro, P.A.d.A.S. Cytoplasmic maturation of bovine oocytes: structural and biochemical modifications and acquisition of developmental competence. Theriogenology 2009, 71, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilia, L.; Chapman, M.; Kilani, S.; Cooke, S.; Venetis, C. Oocyte meiotic spindle morphology is a predictive marker of blastocyst ploidy—a prospective cohort study. Fertility and Sterility 2020, 113, 105–113. e101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).