I. Introduction

Multicellular organisms use a variety of signals to orchestrate the processes that keep them alive. Plants coordinate their development, reproduction and environmental response through phytohormones. These organic molecules are perceived by proteins to initiate signaling cascades that result in cellular and systemic outcomes. During the 20th century, the studied phytohormones were molecules with simple structures (1). It wasn’t until the 90s that the first plant peptide hormone, named Systemin, was discovered in tomato plants (2). From there on, knowledge on these peptides only expanded, and their essential roles in plants became increasingly prominent (3).

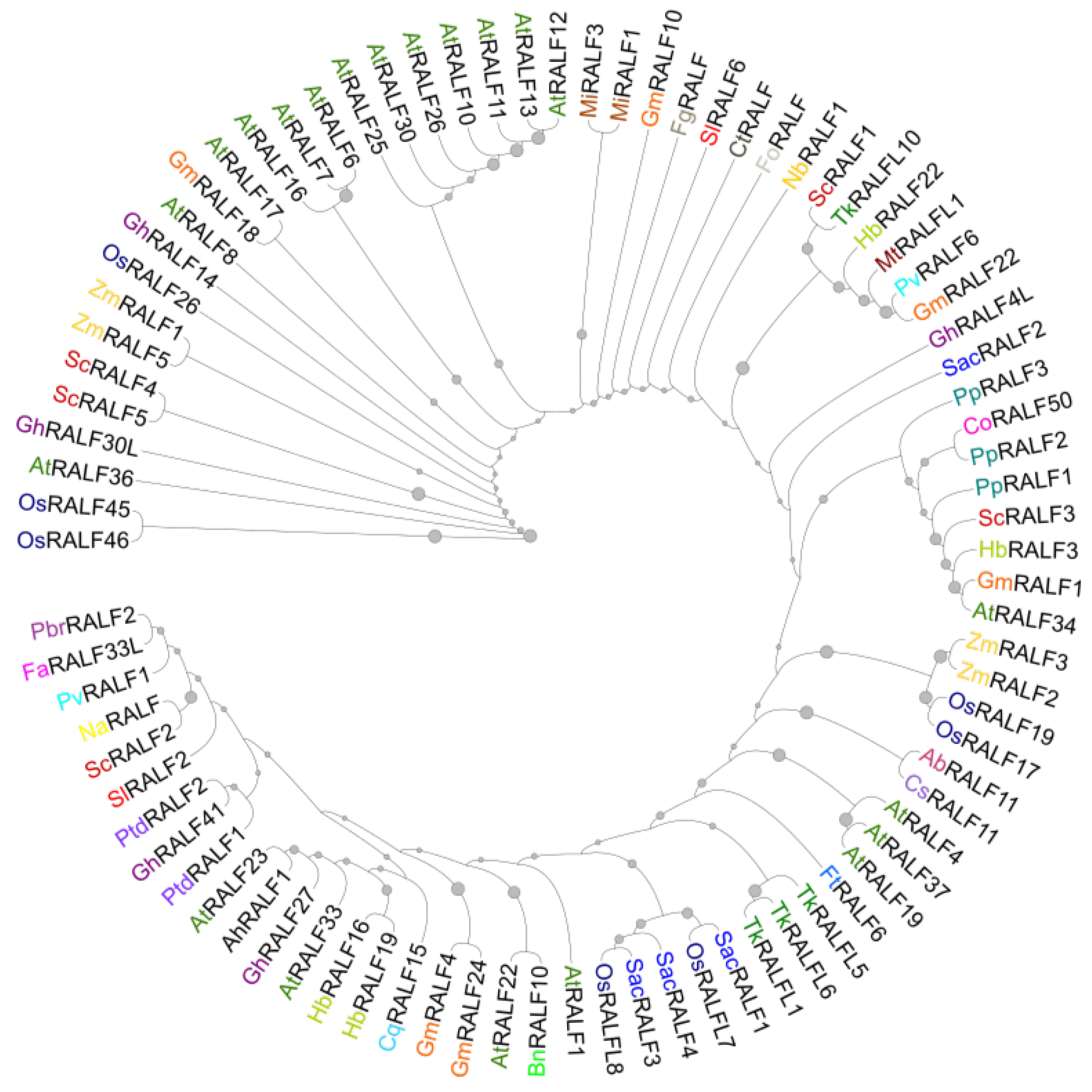

The RAPID ALKALINIZATION FACTORS (RALFs) form a family of peptide hormones present throughout land plants. The number of RALFs varies among different plant species. In eudicots and monocots, the average number of RALF genes per species is approximately 20 and 14, respectively (4). Arabidopsis thaliana possesses a markedly high number of RALF peptides, totaling 37. Evidence suggests that this elevated quantity is the result of tandem gene duplications followed by neofunctionalization (5–7). Curiously, RALF-like genes are also found in phytopathogenic fungi, nematodes and bacteria (4,8,9).

RALFs are involved in plant development, fertilization and response to biotic and abiotic stresses (6). Since their discovery in 2001, the molecular mechanisms behind RALF-induced responses are being unraveled (6,10). The diversity of proteins involved in RALFs’ signaling pathways demonstrates an intricate regulation occurring at multiple levels, including protein interaction and phosphorylation, transcription, transcript processing, translation and post-translational modifications (11–13). These peptides are secreted to the apoplast, where they bind to protein receptors and pectin, inducing intra- and extracellular responses (10).

Topics II to X of this review focus on Arabidopsis thaliana, while Topic XI describes RALF roles in other plant species.

II. Structure

The

RALF genes are translated into precursor peptides (proRALFs or preproRALFs) with domains that dictate their processing and secretion. These newly synthesized RALFs have a length that varies between 80 and 120 amino acids (5). The precursors of all

Arabidopsis mature RALFs have a signal peptide in their N-terminal that directs them to the secretory pathway (5,10). PreproRALFs, however, have an additional domain to be processed, known as the pro-domain. At the C-terminal boundary of this domain is the RRXL motif, which is recognized and cleaved by subtilases (5,14). For example, preproAtRALF22 and preproAtRALF23 are processed by the subtilase SITE-1 PROTEASE (S1P), and this step is necessary for their secretion (15–17). Notably, the most studied RALFs from

A. thaliana, namely RALF1,4,19,22,23,34, possess a pro-domain (5). After processing, mature RALFs have a length of around 50 amino acids (5), and at least mature RALF23 is endogenously present at the 10s-100s of nanomolar range (13).

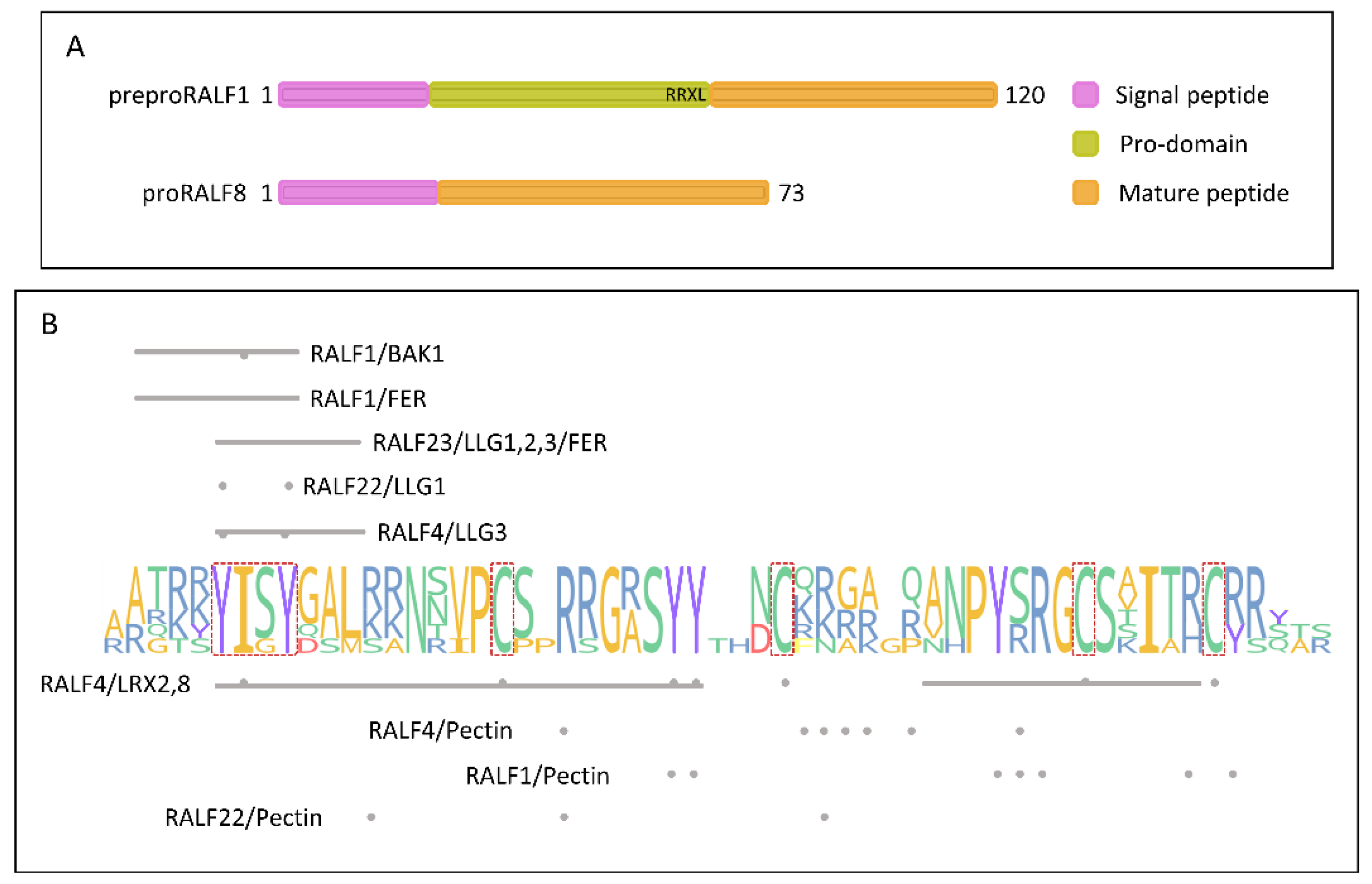

Figure 1A exemplifies the primary structures of a preproRALF and a proRALF.

These peptides can be divided into four clades. The RALFs whose precursor possesses the pro-domain are members of clades I, II, and III. Peptides from these three clades share the YISY motif and four cysteines residues (4). The YISY motif is responsible for RALFs binding to their receptors, while the cysteine pairs form disulfide bridges that structure the peptides and strengthen these interactions (18–22). On the other hand, RALFs whose precursors lack the pro-domain belong to clade IV, do not possess the YISY motif, and often miss one of the four cysteines (4). Despite their structural differences, RALFs from the four clades can share receptors, as evidenced by the fact that, in the reproductive context, at least one member of each clade functionally binds to FERONIA (FER) (23–25). Curiously, in silico studies suggest different binding conformations of various RALFs to FER, even among closely related peptides (26). In addition to their protein receptors, some RALF peptides are capable of binding to pectin (27–29).

Figure 1B illustrates regions and specific residues experimentally shown to be important for RALFs’ interactions with their binding partners.

Figure 1.

Primary structure of RALF peptides.

Figure 1.

Primary structure of RALF peptides.

(A) Examples of RALF precursors from clade I (preproRALF1) and clade IV (proRALF8), highlighting their domains.

(B) Alignment logo of the six most studied RALFs (RALF1, RALF4, RALF19, RALF22, RALF23, and RALF34), showing regions or residues important for peptide binding to their receptors or to pectin.

Red outline: YISY motif and cysteines; Gray bars: important regions for binding; Gray points: important residues for binding.

III. Receptors

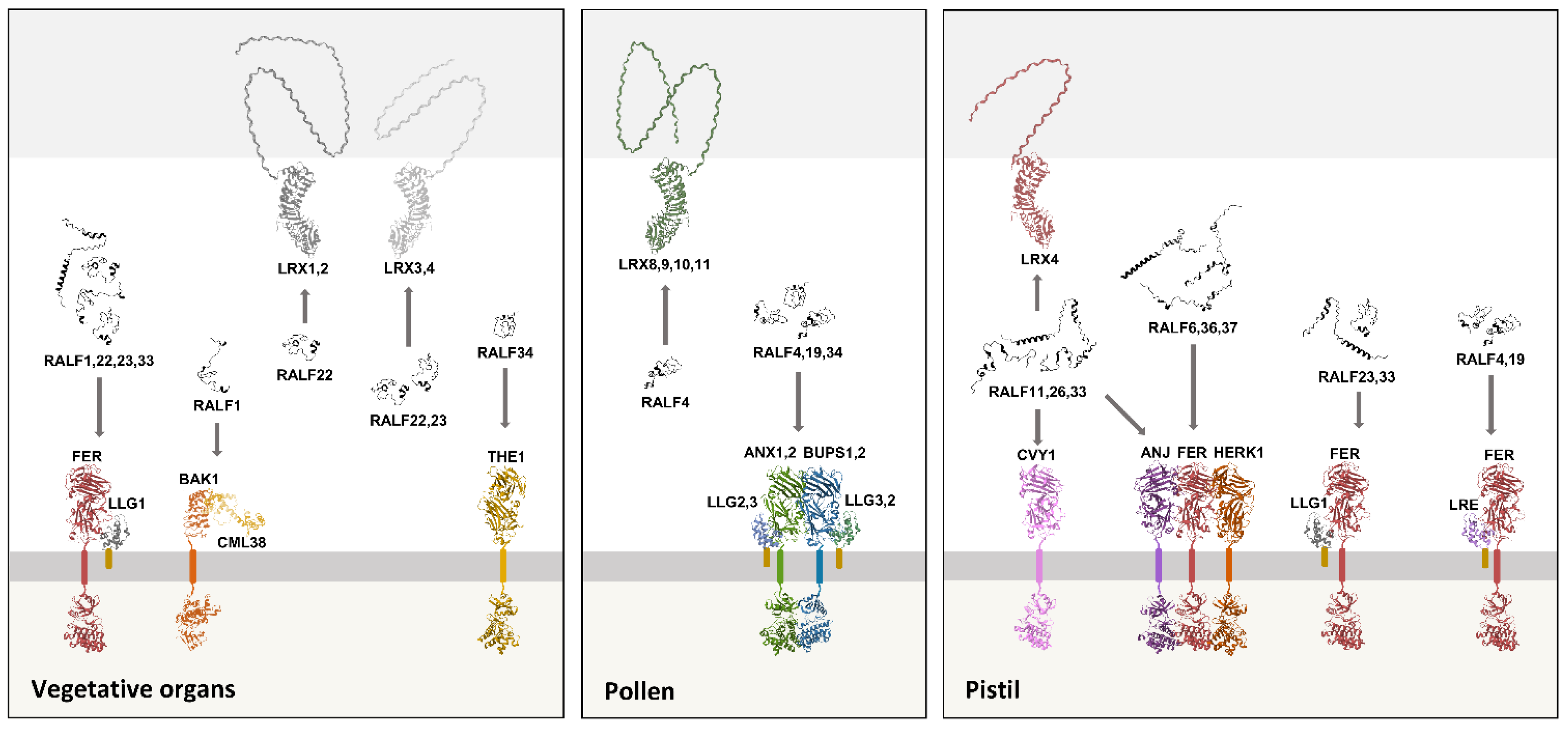

The RALF peptides family has an intimate connection with three receptor families:

Catharanthus roseus RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASE 1-LIKE (CrRLK1Ls), LORELEI-LIKE-GPI-ANCHORED PROTEIN (LLGs) and LEUCINE-RICH REPEAT EXTENSIN (LRXs). The CrRLK1Ls family comprises 17 members in

A. thaliana (30). Among these, FERONIA, THESEUS1 (THE1), ANJEA (ANJ1,2), HERCULES1 (HERK1), BUDDHA'S PAPER SEAL (BUPS1,2), ANXUR (ANX1,2), and CURVY1 (CVY1) stand out for being RALF receptors (20,21,24,25,31,32). The extracellular portion of CrRLK1Ls consists of two malectin-like domains, responsible for binding to RALFs and pectin (21,33). The intracellular portion harbors a kinase domain, and upon RALF perception, a series of auto- and transphosphorylations activate the receptor (34). Acting as CrRLK1Ls’ chaperones and coreceptors, LORELEI (LRE) and LLG1,2,3 form a family of proteins anchored to the plasma membrane by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI), a lipid attached to LLGs posttranslationally (35–37). Members of the third receptor family, the LRXs, are characterized by an extensin domain, key to cell wall association, and a LEUCINE-RICH REPEAT (LRR) domain, responsible for their binding to RALF peptides (22,28,29,38–40). The LRX family comprises 11 paralogues in

A. thaliana, which are expressed in tissue-specific groups with functionally redundant members (40). Intriguingly, the dissociation constants (Kd) for the RALF/CrRLK1L and RALF/LLG interactions are around 0.2–5 µM, while the Kd for RALF/LRX interactions is around 3–5 nM, indicating a remarkably stronger association in the latter (16,18,22,40,41). In addition to these three receptor families, a protein complex formed by BRI1-ASSOCIATED RECEPTOR KINASE 1 (BAK1) and CALMODULIN-LIKE 38 (CML38) also perceives RALF1 in roots, with a Kd of ~4.5 µM (19,42).

Figure 2 summarizes the receptors whose RALFs binding was experimentally shown to have biological function.

IV. Rapid Cellular Responses

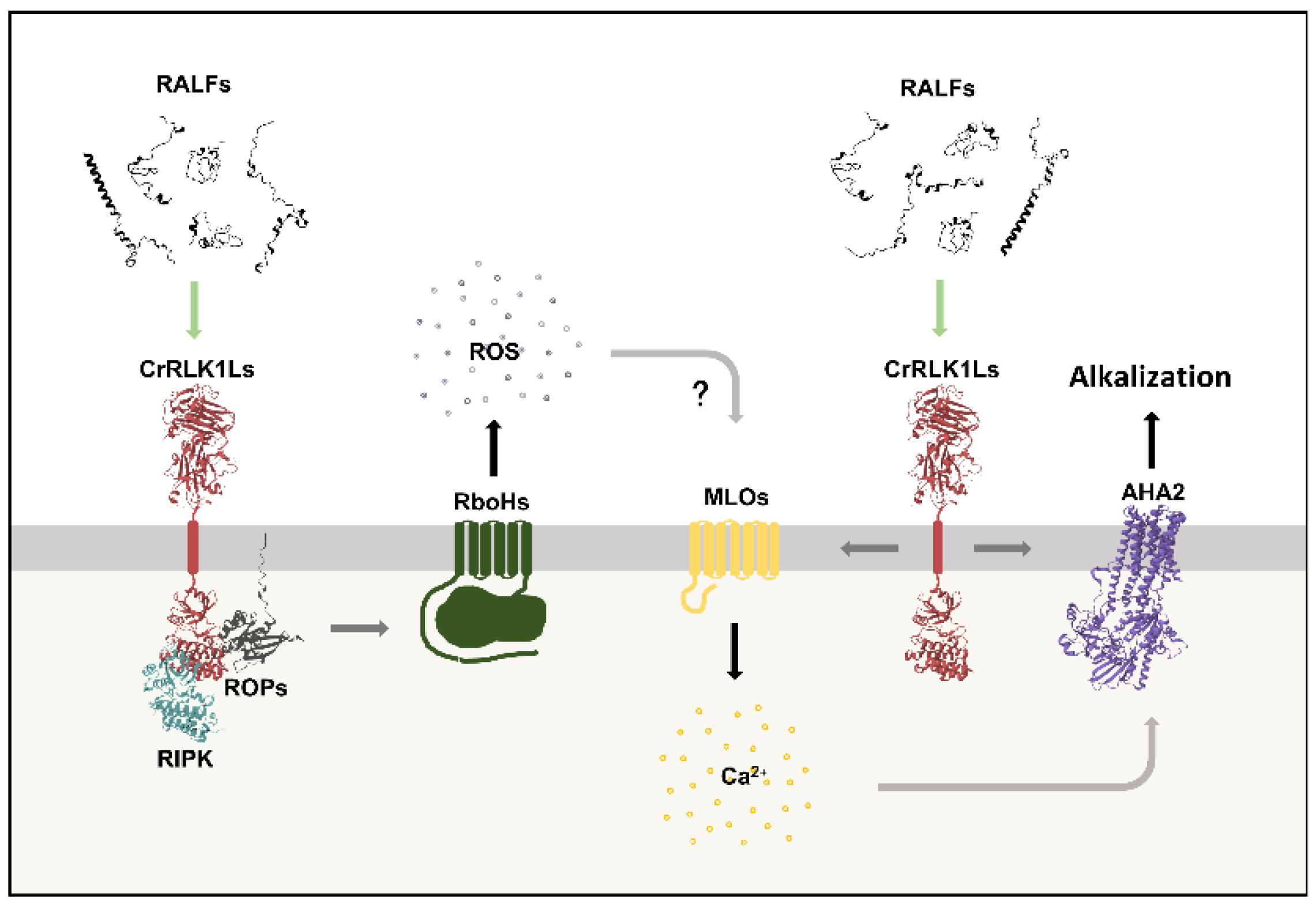

RALF peptides can elicit three rapid changes in the cell’s signaling status: a rise in apoplastic pH, the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and an influx of calcium. These three responses are mediated by the peptides’ canonical CrRLK1L receptors.

For apoplastic alkalinization, RALF1 binds FER to induce phosphorylation and inactivation of the proton pump H(+)-ATPASE 2 (AHA2) (21). The involvement of AHAs in this response was recently questioned (43). However, at the stigma, RALF23 and RALF33 binding to FER and ANJ leads to the protonation of AHA2 at its inactivation residue S899 (44), as seen for RALF1/FER in vegetative tissues (21). RALF1 treatment also induces AHA2 internalization, providing additional evidence for the peptide’s influence on the pumps’ activity (27). In addition to RALF1, treatment with most RALFs increases the apoplastic pH, and receptors other than FER may be involved (5). For example, THE1 is RALF34’s canonical receptor, responsible for transducing the peptide-triggered alkalinization (31). Furthermore, mutants lacking FER show extracellular alkalinization when treated with RALF36, although reduced, suggesting a second receptor (45).

The RALF-induced alkalinization contributes to root growth inhibition (43). The Acid Growth Theory postulates that apoplastic acidification triggered by the phytohormone auxin induces cell wall flexibility, leading to cellular expansion (46). Auxin activates proton pumps, which lower the apoplast pH and alter the activity of cell wall remodeling proteins. The proton gradient also propels water and solute intake, raising turgor pressure, and therefore aiding in cell expansion (47). On the other hand, apoplastic alkalinization by RALF1 is likely responsible for repressing cell expansion, as it is temporally correlated with root growth arrest (43). Moreover, the growth promoting PLANT PEPTIDE CONTAINING SULPHATED TYROSINE 1 (PSY1) binding to PSY1-RECEPTOR (PSY1R) activates AHA1 and AHA2, thereby lowering the apoplastic pH (48). PSY1/PSY1R positively regulate the transcription of RALF22,33,36, whose protein products arrest root growth (45). This feedback loop between peptides with opposing effects on root acidification and growth reinforces the Acid Growth Theory in this context.

RALF peptides induce a rise in cytosolic calcium concentrations ([Ca2+]cyt). This ion acts as a secondary messenger, and specific changes in [Ca2+]cyt are perceived by calcium-binding proteins that transduce the signal (49,50). Calcium signaling also occurs in waves that travel through plant tissues (51). RALF1 treatment raises [Ca2+]cyt in root cells through both cellular intake and mobilization from intracellular reserves (52). The RALF1-induced Ca2+ burst is mainly dependent on FER, but also on THE1 (21,27,31). In turn, THE1 is the main responsible for the RALF34-triggered calcium burst (31). Moreover, roots treated with RALF33 or RALF36 show specific changes in cellular and systemic [Ca2+]cyt profiles in a FER-dependent or -independent manner, respectively (45). RALF8 treatment also induces a rise in [Ca2+]cyt (53). In pollen tubes, members of the MILDEW RESISTANCE LOCUS O (MLO) channel family are responsible for RALF4- and RALF19-induced calcium intake following their binding to ANXs and BUPSs (54). In the synergids, RALF4,19 bind to the FER/LRE complex and activate the calcium channel NORTIA (NTA), another MLO (23). Collectively, these results suggest that CrRLK1L receptors and MLO channels modulate specific calcium responses for each RALF or group of RALFs, in different tissues.

In the presence of RALFs, calcium intake precedes apoplast alkalinization. The Ca2+ spike occurs in less than 60 seconds after RALF treatment, while the pH reaches its maximum after a few minutes (21,31,45,55). Plants pre-treated with La³⁺, a calcium channel blocker, show no alkalinization following RALF treatment, suggesting that the increase in apoplastic pH depends on the secondary messenger (45).

Another important change in plant cell’s signaling status is the ROS production by the NADPH oxidases RESPIRATORY BURST OXIDASE HOMOLOG (RboHs). In roots, RALF1/FER signaling is part of the basal ROS production, and exogenous application of the peptide enhances this response (27,56). Similarly, treating leaf discs with different RALFs raises ROS levels in a FER-dependent manner (5). In pollen tubes, RALF4,19 perception by the ANX/BUPS/LLG complexes regulates ROS oscillation (35). ROS are also central to the immune response, where treatments with RALF23 or RALF33 inhibit ROS production, while treatment with RALF17 or RALF22 stimulates it (16,57,58). The cytoplasmic kinase RPM1-INDUCED PROTEIN KINASE (RIPK), a well-described mediator of the immune ROS burst (59), is important for the RALF22-induced response (57). Members of the RHO-RELATED PROTEIN FROM PLANTS (ROP) family are GDP/GTP ligands activated by GUANINE NUCLEOTIDE EXCHANGE FACTOR (GEFs) (60). During pollen/stigma interactions, control of root microbiota and osmotic stress response, RALF/CrRLK1L signaling modulates ROS levels through ROPs (32,61,62).

In conclusion, the interaction of RALF peptides with CrRLK1L receptors modulates ROS, calcium, and pH levels (

Figure 3). In some contexts, an increase in apoplastic ROS induces calcium influx, and in systemic Ca

2+ and ROS waves, these responses stimulate each other (58). Therefore, the ROS production triggered by RALFs may contribute to Ca

2+ influx, which in turn is necessary for apoplastic alkalinization.

The RALF/CrRLK1L binding modulates: ROS production by RboHs through ROPs and/or RIPK activation; calcium influx through MLO channels; and apoplast alkalinization through phosphorylation and inactivation of AHA2 and/or another proton pump. RALF-triggered ROS production potentially contributes to calcium influx, which in turn precedes the peptide-induced apoplastic alkalinization.

For all figures in this review, green arrows indicate the initial stimulus; gray arrows, steps of the pathway; yellow arrows, phosphorylation; brown arrows, dephosphorylation; and black arrows indicate the ultimate effect of the pathway. Question marks (?) indicate potential steps yet to be proven experimentally.

V. Plant Development

RALFs, auxin and brassinosteroids crosstalk

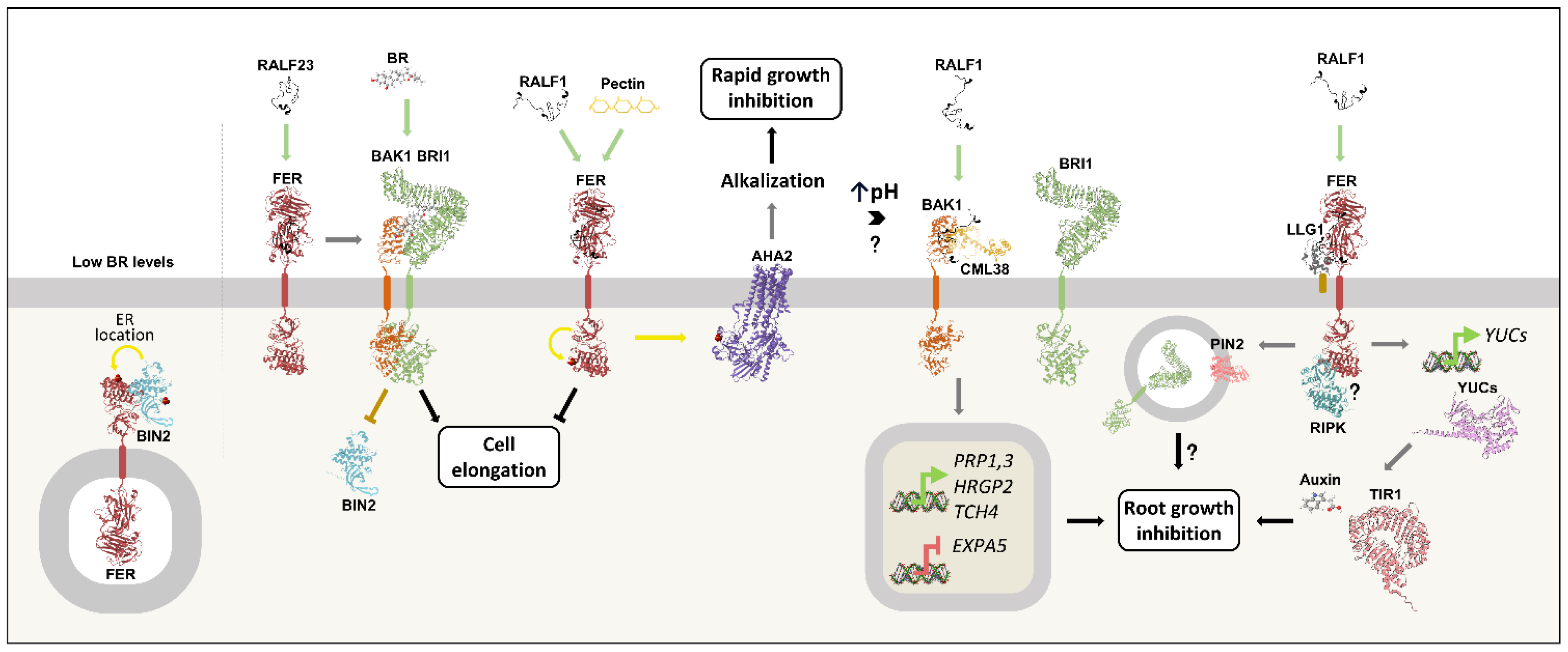

RALF peptides inhibit root and hypocotyl growth by limiting cell expansion (21,63). RALF1-induced growth inhibition involves crosstalk with the phytohormones brassinosteroids (BRs) and auxin (19,43,63). Auxin is a central regulator of plant development and modulates cell expansion, leading to differential growth in roots and hypocotyls (64–66). The auxin indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) is distributed through plant tissues in gradients that are precisely controlled by polar transport and local biosynthesis. Among the enzymes responsible for IAA biosynthesis, the YUCCA (YUCs) stand out for their role in the final reaction that produces the active hormone (67). Meanwhile, auxin polar flux is mediated by the membrane-bound PINs and AUXIN RESISTANT (AUXs) transporters (64). Ultimately, auxin responses rely on changes in gene expression triggered by the degradation of transcriptional repressors, a process where TRANSPORT INHIBITOR RESPONSE 1 (TIR1) is pivotal (47).

The root growth inhibition induced by RALF1 can be divided into rapid and slow phases. The rapid inhibition is reversible and occurs within 1 minute to 1 hour. It is caused by FER-mediated apoplastic alkalinization due to AHA2 phosphorylation and inactivation (21). Alternatively, FER might modulate the activity of a yet undiscovered proton transporter (43). In turn, the RALF-induced slow inhibition phase relies on transcriptional changes. It starts after one hour of RALF1 or RALF22 treatment and is maintained by a FER-mediated induction of the YUC genes, which increases endogenous auxin levels and activates TIR1. The resulting transcriptional changes are responsible for the sustained apoplastic alkalinization and root growth inhibition observed in the presence of RALFs (43). Remarkably, root growth inhibition induced by auxin or RALF1 is dependent on FER-mediated activation of RIPK, making it a potential player in the crosstalk between these hormones (68). Furthermore, plant mutants lacking LLG1 are insensitive to RALF1-induced root growth arrest and to auxin-triggered ROS production (36). Given the FER/LLG1 complex formation (18,27,29,36), it is possible that the coreceptor also contributes to the interplay between these hormones.

FERONIA's involvement in auxin-mediated growth regulation extends beyond the above-mentioned. IAA-triggered apoplast alkalinization is FER-dependent (69). FER also modulates PIN2 localization, and the resulting auxin distribution is necessary for root gravitropism (70). Similarly, root nutation relies on auxin gradients created by PIN2 and AUX1, as well as on calcium intake, both disrupted in the loss-of-function mutant fer-4 (71). Moreover, FER is an important player in the blue light-induced hypocotyl phototropic growth. In this response, FER maintains a high pH on the illuminated side and induces PIN3 accumulation and a high auxin concentration on the shaded side, resulting in differential growth towards light (72). The involvement of RALFs in these mechanisms has not yet been investigated. However, it is worth noting that RALF1 treatment induces PIN2 internalization in a FER-dependent manner (73), which aligns with a possible role for these peptides in auxin-triggered, FER-mediated tropism.

Brassinosteroids are central players in plant growth regulation. These steroid hormones are perceived by the receptor kinase BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 1 (BRI1) and its coreceptor BAK1, starting a signaling cascade that culminates in the activation of two transcription factors, BRASSINAZOLE RESISTANT 1 (BZR1) and BRI1-EMS SUPPRESSOR 1 (BES1). The repressor kinase BR INSENSITIVE 2 (BIN2) is a key component in this signaling, being dephosphorylated and degraded upon BR binding to BRI1/BAK1, consequently releasing BZR1 and BES1 from repression. The resulting change in thousands of genes' expression underlies the brassinosteroid responses (74,75).

RALF1 opposes BR-induced root and hypocotyl growth, as attested by the diminished sensitivity to brassinolide (BL) in RALF1 overexpression lines (63,76). The RALF1-triggered root growth inhibition depends on BAK1 and CML38, to which the peptide binds directly (19,42). In turn, the BR/BRI1/BAK1 complex formation is strictly dependent on acidic pH (77). Thus, a potential mechanism may take place where RALF1/FER-induced apoplast alkalinization favors BAK1 recruitment to the RALF1/BAK1/CML38 complex to the detriment of BR/BRI1/BAK1 complex formation, thereby reducing BR signaling (19,42,77). RALF1 also induces BRI1 internalization in a FER-dependent manner, potentially adding to the peptide antagonism (27,73). Remarkably, the BAK1/CML38 complex is not involved in RALF1-induced alkalinization or in root inhibition by RALF23 or RALF34 (19,42). Through BAK1 and CML38, RALF1 also alters gene expression. RALF1 treatment represses EXPA5, which plays a positive role in cell expansion and is upregulated by BR (19,42,63,78). The peptide also upregulates TCH4, HRGP2, and PRP1,3, which are involved in cell wall rearrangement (19,42,79).

FER is central to BR-induced cell elongation in roots and hypocotyls, a process that requires weakening of cell wall matrix connections and synthesis of new wall components, and thus needs to be tightly coordinated to maintain cell wall integrity (CWI) (80). Under low BR levels, the BIN2 kinase is active and phosphorylates FER, leading to its retention in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). In the presence of BR, BIN2 is inactivated, enabling greater FER localization at the plasma membrane (76), where it senses CWI (33,81). The BR-induced cell expansion generates pectin fragments that act as FER activators and, importantly, RALF1 and pectin exert additive effects on the receptor's signaling. As a result, the activated FER represses the BR stimulus, fine-tuning cellular elongation to prevent CW damage and rupture (76).

Other RALF peptides are also involved in FER-BR crosstalk. The FER/LLG1 complex regulates anisotropic growth of hypocotyl epidermal cells, controlling cell wall pectin content and modifications through PME activity. The

RALF1,22,23,33 genes are expressed in hypocotyls, and the

ralf1/22/23/33 quadruple mutant phenocopies the abnormal growth and CW content phenotype observed in FER and LLG1 mutants. Importantly, hypocotyls of the quadruple

RALF mutant and of plants lacking FER or LLG1 are hypersensitive to BL-induced growth and have diminished levels of the BR-repressed

CPD and

DWF4 transcripts. Further investigation focusing on RALF23 revealed that the peptide promotes BRI1/BAK1 complex formation and BR signaling (82). Therefore, distinct RALFs differentially influence BR signaling, as demonstrated by the opposing effects of RALF1 and RALF23 (76,82). In synthesis, RALF peptides are essential for hypocotyl growth by remodeling the cell wall and mediating FER regulation of the brassinosteroid pathway.

Figure 4 summarizes the crosstalk between RALFs, auxin and brassinosteroids.

RALF1-induced root growth inhibition involves crosstalk with the brassinosteroid (BR) and auxin signaling pathways. Under low BR levels, BIN2 is active and phosphorylates FER, which is retained in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). In the presence of BR, BIN2 is inactivated by dephosphorylation, resulting in greater FER localization at the plasma membrane. There, FER senses CWI to counterbalance BR-induced cell expansion, thus preventing cell wall damage and rupture. The receptor achieves this through apoplast alkalinization, which is stimulated by RALF1 and pectin. RALF1-induced alkalinization leads to rapid root growth arrest and relies on AHA2 phosphorylation and inactivation in a FER-dependent manner. Apoplast alkalinization also leads to BR/BRI1/BAK1 complex dissociation, potentially contributing to the RALF1/BAK1/CML38 complex formation. Through this complex, RALF1 triggers transcriptional changes that lead to the inhibition of cell expansion. In contrast, RALF23/FER binding promotes BRI1/BAK1 complex formation in the hypocotyl, thus contributing to BR signaling. Furthermore, the RALF1-induced inhibition of root growth involves the transcription of YUCCA genes in a FER-dependent manner, leading to increased auxin production and activation of the hormone’s signaling pathway, which includes TIR1. In addition, RALF1/FER induces BRI1 and PIN2 endocytosis, potentially contributing to growth arrest. Finally, RIPK and LLG1 are essential for both RALF1- and auxin-induced responses and may act in the crosstalk between these hormones.

Root cellular signaling

The signaling pathways triggered by RALFs to regulate root development are well characterized. They involve protein interactions and phosphorylation, as well as transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and protein synthesis regulation. A first example is the phosphorylation cascades of MITOGEN-ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE (MAPKs), a common molecular mechanism to amplify intracellular signals (83). RALF1 treatment induces the phosphorylation of MAPK3,4,6, leading to a yet unknown outcome (84). RALF1 also triggers RIPK phosphorylation. In this response, RALF1 binding to FER induces FER/RIPK interaction and transphosphorylation, thus transducing the peptide’s signal to inhibit root growth (68).

The EUKARYOTIC TRANSLATION INITIATION FACTOR 4 (eIF4) complex is responsible for promoting protein synthesis (85). Upon RALF1 binding, FER undergoes autophosphorylation and interacts with eIF4E1, phosphorylating and activating it. EIF4E1 then binds to eIF4G and to the 5’ cap of diverse mRNAs, such as ERBB-3 BINDING PROTEIN 1 (EBP1), inducing their translation. Plant mutants with non-phosphorylatable eIF4E1 are insensitive to RALF1-triggered growth arrest, attesting the importance of eIF4E1 activation for the peptide response (12).

RALF1 also regulates protein synthesis through the tRNA-binding proteins YUELAO (YL1,2,3). The RALF1/FER complex triggers direct phosphorylation of YL1,2,3, leading to tRNA methylation, which reduces the production of specific tRNA fragments (tRFs) (86). Some tRFs are global translation regulators (87), and the RALF1/FER/YL-triggered tRF modifications promote protein synthesis. Remarkably, YL mutants are less sensitive to RALF1-induced root growth inhibition, further supporting the importance of translational control for the peptide response (86).

EBP1 is a DNA- and RNA-binding protein capable of regulating both transcription and translation (88). RALF1 stimulates EBP1 expression and protein synthesis (12,84), and the RALF1/FER ligation also induces the receptor's interaction with EBP1 and phosphorylation of both proteins. Once phosphorylated, EBP1 is directed to the nucleus, where it triggers transcriptional changes, such as the direct repression of CML38 (84). Notably, EBP1 negatively regulates RALF1-triggered root growth inhibition, apoplast alkalinization, and MAPK phosphorylation (12,84). Hence, RALF1 and EBP1 are part of a negative feedback loop.

RALF1 promotes alternative splicing through GLYCINE-RICH RNA-BINDING PROTEIN 7 (GRP7), an RNA-binding protein that regulates the transcription and splicing of other genes (89,90). The RALF1/FER ligation induces GRP7 phosphorylation and directs the protein to the nucleus, where it interacts with the spliceosome component U1 SMALL NUCLEAR RIBONUCLEOPROTEIN 70 KDA (U170K). Accordingly, the RALF1/FER/GRP7 pathway elicits changes in the cell’s splicing profile, contributing to the peptide's root growth inhibition response. Plant mutants lacking SM-LIKE 8 (LSM8) or ARGININE/SERINE-RICH 45 (SR45), two spliceosome components, exhibit reduced sensitivity to RALF1 and to RALF23 treatment (11). Thus, alternative splicing has an essential role in RALF-triggered root growth inhibition.

The Golgi-located ADENYLPYROPHOSPHATASE (APYs) form a family of membrane-bound proteins that can hydrolyze nucleotides (91). APY7 is expressed in roots, and the loss-of-function apy7 mutant exhibits longer roots due to elongated cells. The mutant also has an altered cell wall polysaccharide composition and a higher apoplastic pH. Remarkably, apy7 plants are insensitive to RALF1-induced root growth inhibition (92). How this endomembrane protein affects the peptide signaling, however, remains to be determined.

The transduction of RALF1 signal relies on the peptide’s extracellular dynamics. An important factor is RALF1’s interaction with cell wall pectin in its negatively charged, de-esterified state, a product of PECTIN METHYLESTERASE (PMEs) catalysis (27,93,94). The RALF1-triggered root growth inhibition, apoplast alkalinization and FER internalization responses are absent when PME activity is abolished, either pharmacologically or genetically. In addition, two newly described RALF1-induced phenotypes of cell wall swelling and plasma membrane invagination are reversed in the absence of PME activity, when an excess of de-esterified pectin fragments out-titrates RALF1, and in fer-4 mutants. Therefore, pectin is a central part of the

RALF1/FER-triggered responses, and may act as a signaling scaffold for the peptide (93). Notably, the RALF/LRX complex binds to pectin in root hairs and pollen tubes (28,29). However, quintuple mutants lacking LRX1-5 resemble wild-type plants under RALF1 treatment, indicating that LRXs are not part of the aforementioned responses (93).

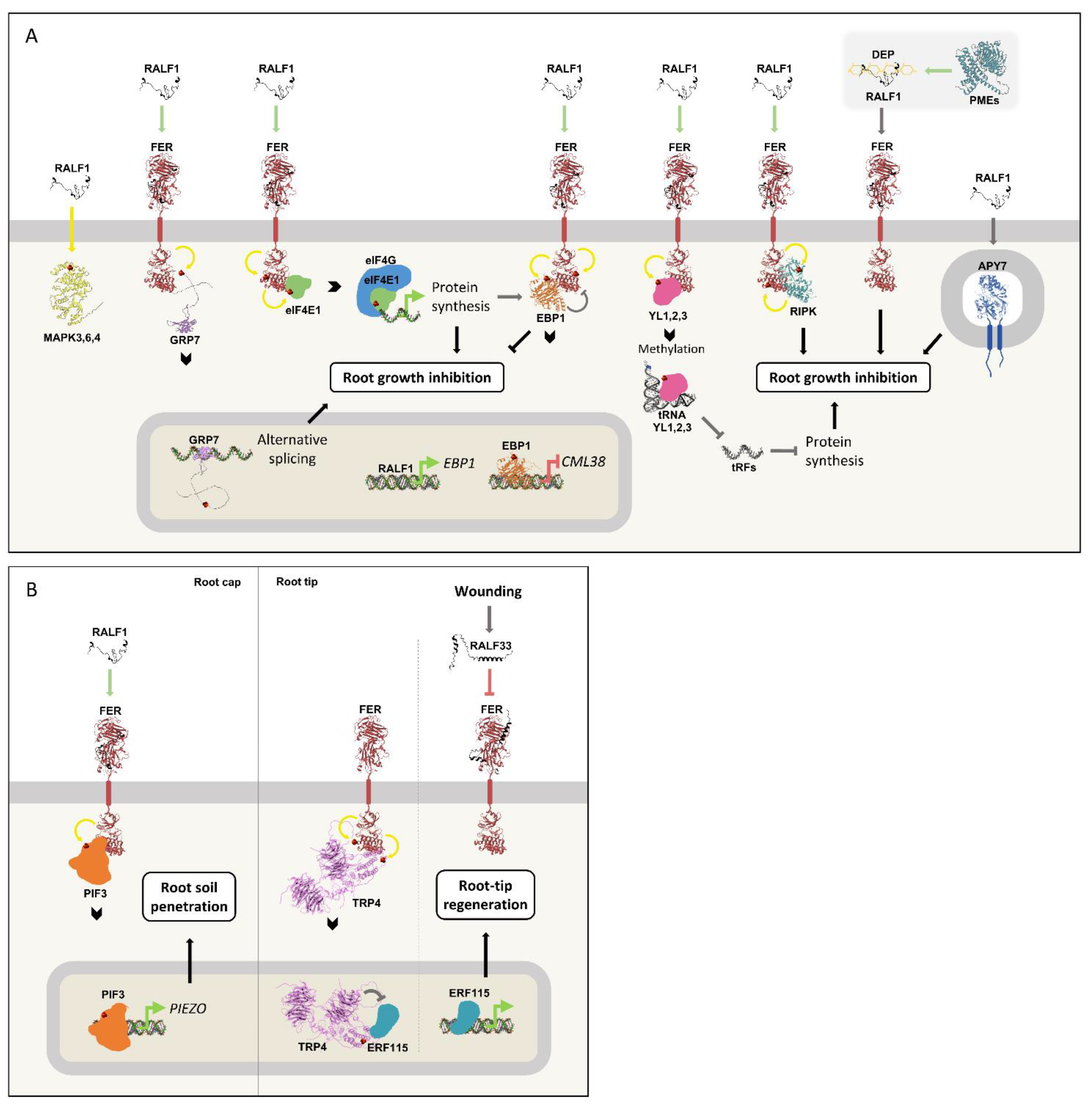

Figure 5A summarizes the complex intracellular signaling elicited by RALF1.

FER signaling is essential for root soil penetration, and involves the transcription factor (TF) PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTOR 3 (PIF3), better known for its role in etiolated cotyledons' soil emergence (95,96). In root cap cells, FER phosphorylates PIF3, contributing to its stabilization and abundance, which leads to the TF’s direct induction of PIEZO expression, a mechanosensitive ion channel that modulates calcium flux (95,97). The FER-PIF3-PIEZO pathway leads to proper soil penetration and is induced by RALF1, but not by RALF23. Remarkably, RALF1 treatment also triggers the expression of dozens of genes in columella root cap cells in a FER-dependent manner (95).

Under normal root conditions, FER phosphorylates the transcriptional corepressor TOPLESS-RELATED 4 (TPR4), which translocates to the nucleus, where it directly represses ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR115 (ERF115) (98,99), a TF involved in root tip regeneration (100). After root wounding, RALF33 levels rise to 200 nM and bind to FER, reducing the receptor’s autophosphorylation at its activation residue Y648 (34,98). Accordingly, the RALF33/FER interaction lowers TPR4 phosphorylation and nuclear localization. Thus, RALF33 inhibits FER repression of ERF115 through TPR4, allowing the TF to modulate gene expression leading to root tip regeneration (98).

Figure 5B illustrates RALF-regulated responses promoting proper root development and integrity.

Figure 5.

RALF peptides elicit complex signaling in roots.

Figure 5.

RALF peptides elicit complex signaling in roots.

(A) RALF1 induces the phosphorylation of MAPK3,4,6. RALF1 also binds to FER, and the receptor's kinase domain phosphorylates GRP7, eIF4E1, EBP1, YL1,2,3 and RIPK, leading to root growth inhibition. Phosphorylated GRP7 accumulates in the nucleus, where it regulates alternative splicing. The phosphorylation of eIF4E1 increases its affinity for eIF4G and mRNAs, inducing protein synthesis. One of the translated proteins is EBP1, whose phosphorylation and transcription are also induced by RALF1. After its phosphorylation by RALF1/FER, EBP1 accumulates in the nucleus, where it regulates gene transcription, notably inhibiting CML38 expression. In summary, RALF1 induces EBP1 production and activation, which in turn represses RALF1 signaling via a negative feedback loop. Moreover, RALF1 induces the phosphorylation of YL1,2,3 through FER, leading to tRNA methylation and a consequent decrease in tRF production, which reduces protein synthesis and inhibits root growth. The PME enzymatic activity generates de-esterified pectin (DEP), and RALF1 interaction with the negatively charged polysaccharide is essential to root growth inhibition. The Golgi-located APY7 is also necessary for RALF1-induced root growth inhibition.

(B) At the root cap, FER directly phosphorylates PIF3, stabilizing it and increasing its abundance in the nucleus, leading to the upregulation of PIEZO. This signaling pathway is essential for root soil penetration and is induced by RALF1 treatment. At the root tip, FER autophosphorylates and phosphorylates TPR4, which translocates to the nucleus where it represses ERF115. After root wounding, RALF33 levels rise, and its binding to FER represses TPR4 phosphorylation, allowing ERF115 to initiate a transcriptional response that culminates in root tip regeneration.

Lateral roots

RALF peptides are involved in lateral root (LR) formation. RALF34 is expressed in LR primordia, and its transcription is regulated by auxin and the transcription factors ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR (ERF4,9) (101). RALF34 binds the receptor kinase THE1 to regulate LR emergence. Curiously, mutants lacking RALF34 or THE1, as well as plants overexpressing either gene, exhibit a similar phenotype of increased LR primordia and incorrect primordia patterning, pointing to a finely tuned regulation (31). Furthermore, plants treated with RALF33 or RALF36 have higher LR density despite having smaller primary roots (45). In contrast, mutants with reduced RALF1 expression exhibit higher LR density and longer primary roots than wild-type plants (63). Together, these results suggest that RALF peptides regulate lateral root emergence and development through yet underexplored signaling pathways.

Root hairs

Root hairs (RH) are extremely elongated extensions of epidermal cells responsible for water and nutrient acquisition, anchoring, and interaction with microorganisms. RH's rapid expansion is sustained by the exocytosis of plasma membrane and cell wall components at the hair’s apex (102). RALF peptides are involved in the emergence and development of these structures. Among the family members, RALF22 is the most expressed in RH, where it binds to the receptor complex FER/LLG1 and to LRX1,2, promoting cell wall integrity (CWI) and growth (29). Furthermore, lines overexpressing RALF8 or plants treated with RALF33 or RALF36 exhibit longer RH with increased density (45,103). Similarly, RALF1 treatment induces longer RH in a FER-dependent manner, while RALF1 knockout mutants show the opposite phenotype (12,68).

During root hair expansion, RALF22 functions both as a signaling molecule and as a cell wall component. The peptide binds to the FER/LLG1 complex, promoting calcium influx, apoplast alkalinization, and cell wall esterified pectin (EP) accumulation. RALF22 also binds to LRX1 and LRX2, forming heterotetrameric complexes composed of two RALFs and two LRXs (29). In pollen tubes, RALF4/LRX8 ligation exposes the peptide's basic residues, which increases its affinity to negatively charged de-esterified pectin (DEP) (22,28). The RALF22/LRX1,2 complexes formed in RHs also interacts with DEP, potentially through the same configuration. This RALF22/LRX1,2/DEP assembly expels water molecules from the pectin layer of RH’s cell wall, thereby stiffening it and aiding in CWI during tip growth. Remarkably, root hair apical expansion occurs in an oscillatory manner, where growth arrests are synchronized with the cyclical incorporation of RALF22 into the cell wall. This process results in the formation of RALF22/LRX1,2/DEP rings around the root hair flanks (29). Based on this evidence and the observation that PMEs' enzymatic activity peaks at an alkaline pH (104), Schoenaers and collaborators proposed the following mechanism for RH growth: 1) RALF22 and LRX1,2, along with esterified pectin and PMEs, are secreted at the root hair’s apex; 2) RALF22 binds to FER/LLG1 and induces calcium influx, cell wall’s EP accumulation, and apoplast alkalinization, activating PMEs and thereby increasing the levels of DEP; 3) RALF22/LRX1,2 complexes then bind to the newly synthesized DEP, forming a ring that stiffens the cell wall, marking the end of a growth cycle; 4) A new round of secretion takes place and free RALF22 binds to FER/LLG1, initiating a new cycle (29).

It is important to mention that sucrose induces RALF22 expression and that, in media not supplemented with this sugar, the ralf22 mutant exhibits hair growth comparable to the wild-type plants (105). Thus, RALF22-mediated RH growth appears to be dependent on sucrose, opening the possibility of other RALFs acting under normal conditions.

RALF1 changes the root hair’s protein composition through eIF4E1, contributing to its growth. RALF1 binding to FER induces the receptor autophosphorylation and transphosphorylation of eIF4E. Phosphorylated eIF4E1 exhibits increased affinity for eIF4EG and the 5’ cap of various transcripts, notably

EBP1,

ROP2 and

ROOT HAIR DEFECTIVE 6-LIKE 4 (

RSL4), thereby increasing their protein levels (12). EBP1 is a negative regulator of RALF1-triggered root growth inhibition (84). ROPs’ regulation of ROS production is essential for RH growth, and FER induces this response in a ROP2-dependent manner (12,106–108). RSL4 is a transcription factor whose protein levels during RH expansion directly influence the structure's final size (109,110). Moreover, RSL4 binds to

RALF1 promoter and represses its expression, thus forming a negative feedback loop (12). Single-cell RNA-seq of roots treated with RALF1 further demonstrates its impact on RH transcription in a FER-dependent manner (95). In summary, RALF1/FER regulates the RH translation through eIF4E1 and its transcription through RSL4. Remarkably, treating seedlings with RALF22 results in RH growth inhibition, in contrast to the growth induction caused by RALF1, RALF33, or RALF36 treatments (12,29,45). These opposing effects confirm the existence of at least two distinct RALF-regulated mechanisms governing root hair cellular expansion.

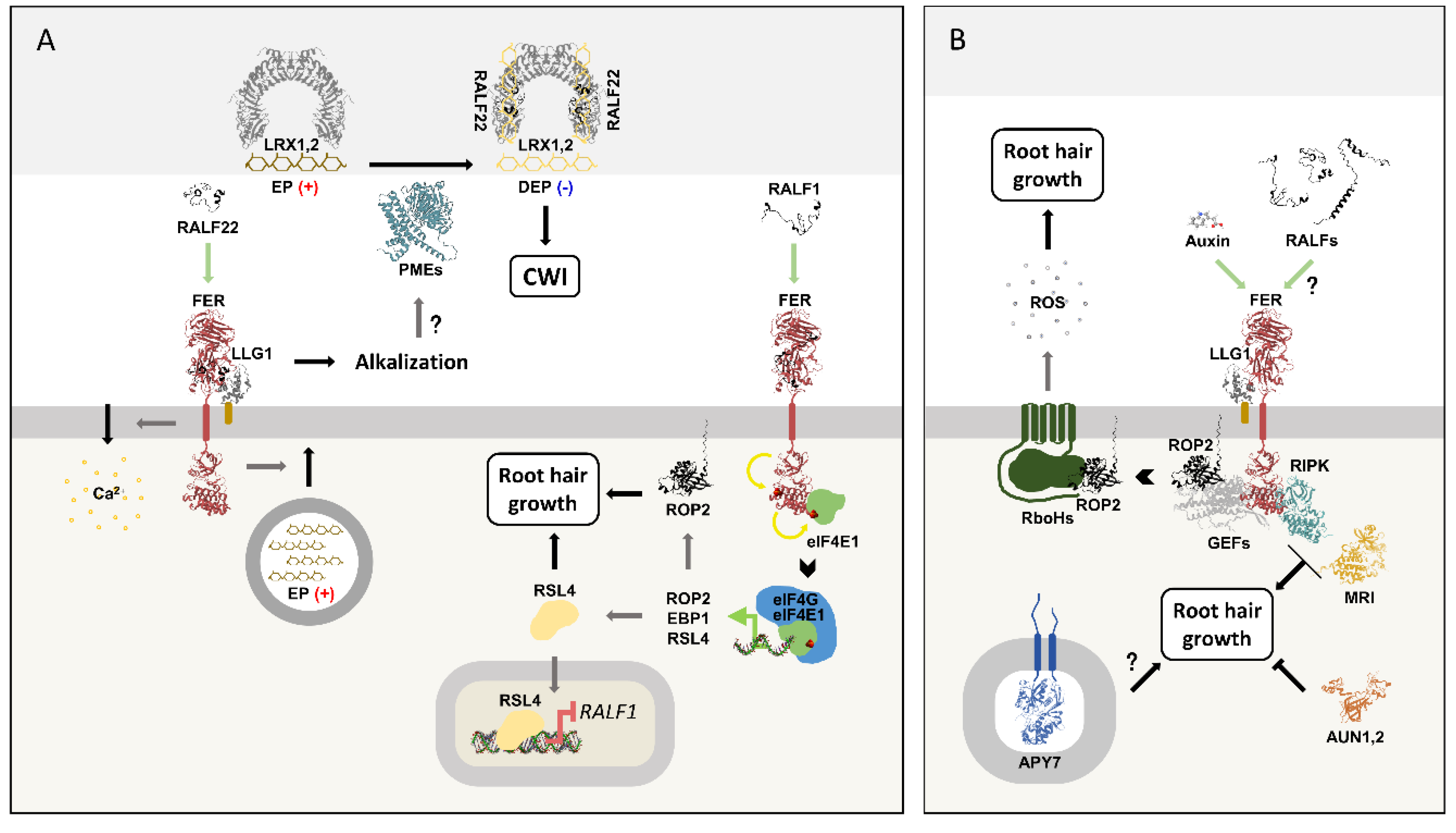

Figure 6A summarizes the roles of RALF1 and RALF22 in RH growth.

Root hair development is promoted by auxin (111), and the FER/LLG1 complex is indispensable for auxin-triggered RH initiation and elongation (36,108). In this context, FER induces ROS production through ROP2 and GEF1,4,10 (108,112). In addition, the fer-4 mutant is deficient in RH formation, while overexpression of RIPK in the fer-4 background reverses this phenotype, pointing to a positive role for RIPK downstream of FER (68). Remarkably, IAA-induced RH growth is absent in the ralf22 knockout mutant, indicating that RALF22 is also involved in auxin signaling (105). Together, this information suggests a potential crosstalk between RALFs and auxin in RHs, as seen in primary roots (43).

APY7 is bound to the Golgi membrane and is required for RALF1-induced inhibition of primary root growth. The apy7 mutant was found to reverse the lack of root hairs in the lrx1/2 double mutant and partially reverse this phenotype in the fer-4 background (92). These results raise the possibility that APY7 acts downstream of RALFs, LRXs, and/or FER in root hair development, which requires further investigation.

Similar to root hairs, pollen tubes (PTs) exhibit rapid apical growth. In both structures, different RALFs, CrRLK1Ls, and LRXs members are involved in cellular expansion (28,29,41), pointing to a conserved molecular mechanism driving the coevolution of these protein families. A key intracellular aspect of this mechanism investigated in PTs has not yet been fully explored in RHs. In PTs, the cytoplasmic kinase MARIS (MRI) acts downstream of the RALF4,19/ANXs/BUPSs complexes to maintain CWI (38,54). In contrast, the cytoplasmic phosphatases ATUNIS (AUN1,2) oppose RALF4,19’s and LRX8-11’s positive regulation of CWI maintenance (113). MRI and AUN1,2 roles in pollen tubes extend to root hairs, where they act downstream of FER and LRX1,2. Accordingly, MRI positively regulates, while AUN1,2 negatively regulate the CWI of RHs (40,114), and the involvement of RALFs in this pathway has not been investigated. This and other potential components of the RALF-induced root hair expansion pathway are summarized in

Figure 6B.

Figure 6.

RALF1 and RALF22 regulate root hair growth.

Figure 6.

RALF1 and RALF22 regulate root hair growth.

(A) RALF22 binds to FER/LLG1, inducing apoplast alkalinization, calcium influx, and the accumulation of esterified pectin (EP) in the cell wall. RALF22 also forms heterotetrameric complexes with LRX1,2, which bind to de-esterified pectin (DEP) and maintain cell wall integrity (CWI). The alkalinization induced by RALF22/FER/LLG1 potentially activates PMEs and contributes to the RALF22/LRX1,2/DEP assembly. RALF1 binds to FER, inducing eIF4E1 phosphorylation, thereby increasing the synthesis of ROP2, EBP1, and RSL4. ROPs are important players in RH growth. RSL4 regulates RH transcription, inducing its growth. RSL4 also represses RALF1 expression, forming a negative feedback loop.

(B) Steps that may be part of the RALF-mediated RH growth pathway. The FER/LLG1 complex is required for auxin-induced ROS production through ROPs/GEFs, which is essential to RH growth. RIPK, MRI, and AUN1,2 modulate RH growth downstream of FER. APY7 is necessary for RALF1-induced primary root growth inhibition and is involved in the FER and LRX root hair development pathways.

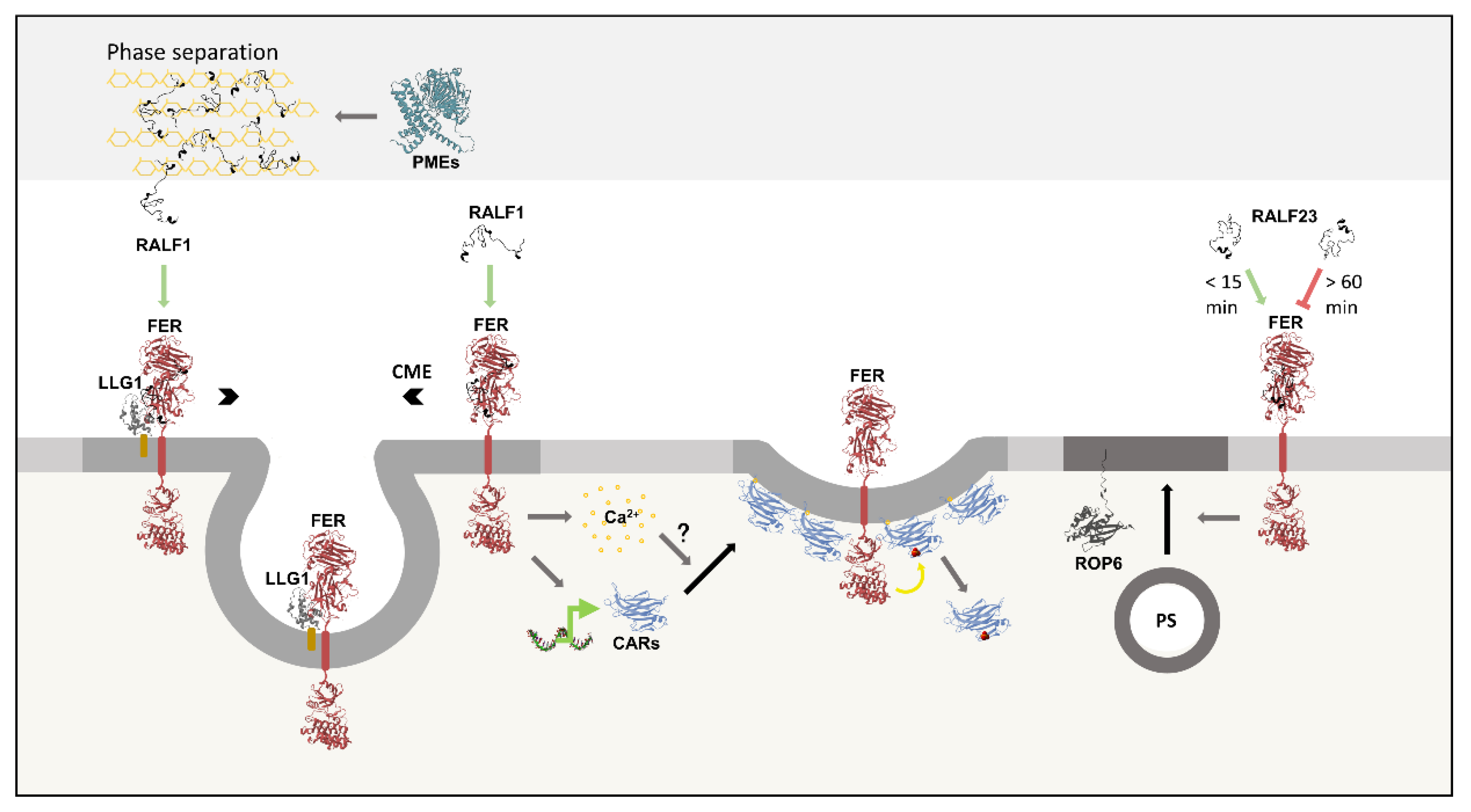

VI. Membrane Dynamics

Membrane components are in constant cycling, and endocytosis can be mediated by clathrin (CME) or not (CMI) (115). FER undergoes constitutive endocytosis through both CME and CMI pathways; however, in the presence of RALF1, FER is internalized mainly through CME. Consistently, CME-defective double mutants lacking CLATHRIN LIGHT CHAIN (CLC1,3) are less sensitive to RALF1-induced root growth inhibition, although they remain sensitive to the RALF1-induced transcription changes and MAPK activation. Moreover, RALF1 treatment decreases FER diffusion and increases its enrichment in microdomains (73).

The plasma membrane is a heterogeneous structure with micro and nanodomains that exhibit diverse lipid and protein compositions, as well as mobility characteristics (116). RALFs peptides and FER can induce the formation of membrane domains through at least three different mechanisms: RALF1 and pectin phase separation (27); synthesis and recruitment of C2-DOMAIN ABA-RELATED (CAR) proteins (117); and accumulation of the phospholipid phosphatidylserine (PS) in the membrane (61).

Phase separation is the aggregation of macromolecules into two solutions with distinct and stable compositions (118). In the apoplast, RALF1 interacts with de-esterified pectin, leading to phase separation. At the plasma membrane in contact with this aggregate, FER and LLG1 are enriched due to their interaction with RALF1. Other receptors, such as FLS2 and BRI1, are also recruited by unknown means. This molecular organization creates micro and nanodomains with a high density of membrane-bound proteins, where endocytosis is intense. Curiously, RALF1 is not internalized with its receptors. RALF1/DEP phase separation is necessary for the maintenance of root’s basal ROS levels in a FER/LLG1-dependent manner, as well as for the rise in ROS production and Ca2+ influx triggered by an increase in RALF1 concentrations. Furthermore, pharmacological or genetic inhibition of PME activity suppresses RALF1-induced phase separation and endocytosis, highlighting the importance of these enzymes in the peptide’s responses. Notably, RALF1/DEP/FER/LLG1 aggregates are present during regular plant development, serving as a constitutive mechanism. However, salt and heat stresses significantly increase the extent of this arrangement (27).

In addition to the changes in membrane organization driven from the apoplast, RALF1 signaling also induces domain formation from the cell’s interior. CAR proteins bind to Ca2+ through their C2 domain and interact with negatively charged phospholipids, creating a membrane curvature (119). RALF1 binding to FER induces the translation of CAR1,4,5,6,9,10, along with rapid formation of CAR nanodomains (117). The calcium influx elicited by RALF1/FER is potentially part of this response (21,117). Once in the nanodomains, FER phosphorylates the CARs’ C2 domain, reducing the protein's affinity for phospholipids, likely due to charge repulsion. Thus, the nanodomain formation by RALF1/FER/CARs is an autoregulated process (117).

FER controls the accumulation of phosphatidylserine in the plasma membrane. PS accounts for 10-15% of the total plasma membrane lipids in eukaryotic cells and is kept in the cytoplasmic-facing leaflet (120). In plants, PS nanodomains stabilizes ROP6 membrane dynamics, which is essential for ROS production under osmotic stress (61,121,122). Short-term (<15 min) RALF23 treatment positively regulates PS nanodomain formation and osmotic stress response through FER. In contrast, long-term (>60 min) RALF23 treatment decreases PS membrane abundance and nanodomain formation, reducing ROP6 signaling and the consequent ROS production under osmotic stress (61). Together, these three RALF/FER-induced mechanisms modulating membrane dynamics add an important layer to our understanding of RALF peptide signaling (

Figure 7).

RALF1 interacts with de-esterified pectin (depicted in yellow) in the cell wall, inducing phase separation. At the adjacent plasma membrane, RALF1 binds to FER/LLG1, forming micro- and nanodomains where endocytosis takes place. Notably, the PMEs activity is essential to this response. RALF1 binding to FER also decreases the receptor diffusion and increases its enrichment in microdomains, where it undergoes clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME). Furthermore, RALF1/FER induces the synthesis of CAR proteins, which bind to membrane phospholipids, forming curved nanodomains. The RALF1/FER-induced calcium influx potentially contributes to this response. Once in these nanodomains, FER phosphorylates CARs, decreasing their membrane affinity. FER is also involved in the incorporation of phosphatidylserine (PS) into the membrane and its organization in micro- and nanodomains, which stabilize ROP6 mobility. Short-term (<15 min) RALF23 treatment increases this response, while long-term (>60 min) treatment suppresses it.

VII. RALF-ABA Crosstalk

During their life cycle, plants receive diverse environmental stimuli, which are integrated into responses that favor development or defense. The phytohormone abscisic acid (ABA) plays a central role in this process, leading to outputs that include the control of growth and stomatal movement (123). In a default state, ABA signaling components remain suppressed due to the action of the type 2C protein phosphatases ABA INSENSITIVE (ABI1,2). The perception of ABA by its receptors, including PYRABACTIN RESISTANCE 1-LIKE (PYLs), inhibits these phosphatases to activate the hormone’s signaling pathway, which includes transcription factors such as ABI5 and ABSCISIC ACID RESPONSIVE ELEMENT-BINDING FACTOR (ABFs) (124).

RALF1 and ABA signaling pathways regulate each other through distinct mechanisms. RALF1 binding to FER induces the receptor phosphorylation, while ABI2 dephosphorylates FER, decreasing the RALF1-triggered root growth inhibition response. (125). Evidence points to a FER-stimulated activation of ABI2, which may serve as a self-regulating mechanism (126). The presence of ABA favors FER phosphorylation by inactivating ABI2 in a PYL-dependent manner. Accordingly, plant mutants lacking PYL receptors exhibit reduced sensitivity to RALF1-triggered root growth inhibition, indicating an agonistic role of ABA in the peptide’s signaling. In contrast, RALF1 decreases ABA-induced root growth inhibition, supporting an antagonistic role for the peptide in the ABA signaling pathway (125). This negative effect is further supported by the observation that plant mutants lacking FER, LLG1, or RIPK, key proteins for RALF1 responses, are hypersensitive to ABA-triggered root growth inhibition (36,68,126). In addition, mutants lacking EBP1, a negative regulator of RALF1’s pathway, are less sensitive to the ABA-induced response (84). Collectively, these findings point to a negative feedback loop where ABA presence favors RALF1 signaling, which in turn negatively regulates the phytohormone responses.

A recently discovered mechanism of RALF1-mediated repression of ABA signaling involves the protein FYVE DOMAIN PROTEIN REQUIRED FOR ENDOSOMAL SORTING 1 (FREE1) (127), which was initially described for its role in vesicle sorting (128). FREE1 was later characterized as a negative regulator of ABA signaling by interacting with ABI5 and ABF4 in the nucleus, reducing their transcriptional activity (129). RALF1 binding to FER induces the receptor’s direct phosphorylation of FREE1, which then translocates to the nucleus. There, phosphorylated FREE1 negatively regulates the expression of ABA-responsive genes induced by ABI5 or ABF4, reinforcing a RALF1/FER role as antagonists of ABA signaling (127).

Another mechanism of reciprocal modulation between these hormones involves the RNA-binding protein GRP7. RALF1/FER ligation induces direct GRP7 phosphorylation, which subsequently binds to the

ABF1 mRNA (11). ABF1 is a transcription factor in the ABA pathway, and its transcript exists in two splicing variants,

ABF1.1 and

ABF1.2 (11,124). GRP7 activation by RALF1/FER favors the

ABF1.2 splicing variant, which dampens ABA’s responses. In turn, ABA induces

GRP7 alternative splicing, generating a premature stop codon and therefore decreasing its levels (11). This elegant mechanism illustrates how the crosstalk between RALF1 and ABA extends to post-transcriptional regulation.

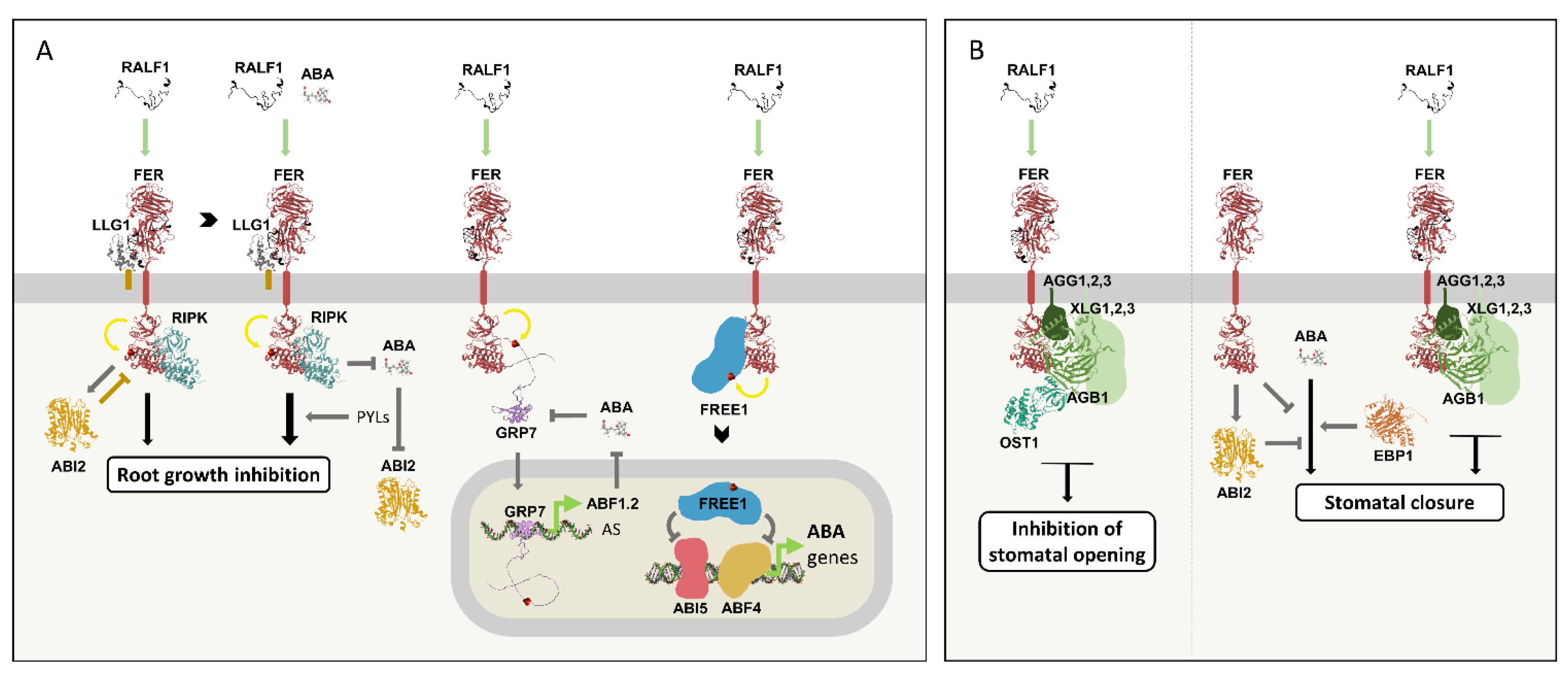

Figure 8A summarizes the known interactions between the RALF1 and ABA signaling pathways during root growth regulation.

Stomatal closure plays a fundamental role in regulating gas exchange and preventing water loss through the leaves (123). G proteins act as heterotrimers composed of the subunits Gα, Gβ, and Gγ, and are well-known players in the transduction of multiple signals in eukaryotes. Plants possess an additional type of Gα subunit, the EXTRA-LARGE G PROTEINs (XLGs) (130). FER binds to G PROTEIN SUBUNIT BETA 1 (AGB1) and this interaction depends on G PROTEIN SUBUNIT GAMMA (AGG1,2,3). RALF1 treatment inhibits stomatal aperture and induces its closure, and these responses are absent in mutants lacking FER, AGB1, AGG1,2,3, or XLG1,2,3 (131). Therefore, RALF1’s control of stomatal movement is mediated by FER and the G proteins. Moreover, overexpression of the kinase-dead FERK565R in a fer-4 background only partially restores the RALF1-induced stomatal regulation absent in fer-4, suggesting a secondary role for the receptor's phosphorylation activity in this response (132).

The RALF1- and ABA-mediated pathways controlling stomatal movement share proteins. Plants lacking OPEN STOMATA 1 (OST1), an ABA signaling kinase that interacts with AGB1, are insensitive to RALF1’s inhibition of stomatal opening (131). In contrast, the

fer-4 mutant is hypersensitive to ABA's inhibition of stomatal opening (125). This hypersensitivity is opposed by an ABI2 gain-of-function mutation, in which the phosphatase activity is resistant to ABA inhibition, suggesting that FER’s negative role in ABA signaling may result from the activation of ABI2 (125,126). Lastly,

EBP1 knockout mutants are less sensitive to ABA-induced stomatal closure, suggesting a positive role in ABA response for this negative regulator of RALF1 signaling (84). Collectively, these results point to an integration of RALF1’s and ABA’s pathways that extends to the regulation of stomatal movement (

Figure 8B).

Lastly, the loss-of-function mutants fer-4 and lrx345, as well as lines overexpressing RALF22 or RALF23, have increased ABA levels compared to wild-type plants. These results suggest that some RALFs and their canonical receptors also regulate ABA homeostasis (133), which further supports a close relation between ABA and this peptide hormone family.

Figure 8.

Crosstalk between the RALF1 and ABA signaling pathways.

Figure 8.

Crosstalk between the RALF1 and ABA signaling pathways.

A) RALF1 binding to FER/LLG1 induces the receptor phosphorylation, leading to root growth inhibition in a RIPK-dependent manner. This response is counteracted by ABI2 dephosphorylating FER, which, in turn, activates ABI2. The presence of ABA increases FER phosphorylation by suppressing ABI2 activity in a PYL-dependent manner, thereby favoring RALF1 signaling. In contrast, the RALF1/FER/LLG1/RIPK complex represses the ABA pathway. RALF1/FER phosphorylates GRP7, which binds to ABF1 mRNA, favoring the splicing variant ABF1.2 and consequently dampening ABA signaling. In turn, ABA induces GRP7 alternative splicing (AS), resulting in a premature stop codon variant and therefore reducing GRP7 protein levels. RALF1/FER also phosphorylates FREE1, which translocates to the nucleus and represses ABI5- and ABF4-induced transcriptional responses, thereby negatively regulating ABA signaling.

B) RALF1/FER inhibits stomatal opening through the G proteins (AGG1,2,3, AGB1, and XLG1,2,3), and OST1. RALF1/FER also induces stomatal closure through the G proteins. Furthermore, FER negatively regulates ABA-induced stomatal closure, potentially by activating ABI2. In contrast, EBP1 positively regulates ABA induced stomatal closure.

VIII. Abiotic Stresses

Salinity stress

RALF peptides and their receptors are involved in the response to high salinity. The excess of sodium chloride (NaCl) is particularly harmful to plants, as it leads to both ionic and osmotic stresses (134). On top of that, ROS production is an essential part of salt tolerance and needs to be precisely regulated to avoid an additional burden, the oxidative stress (135).

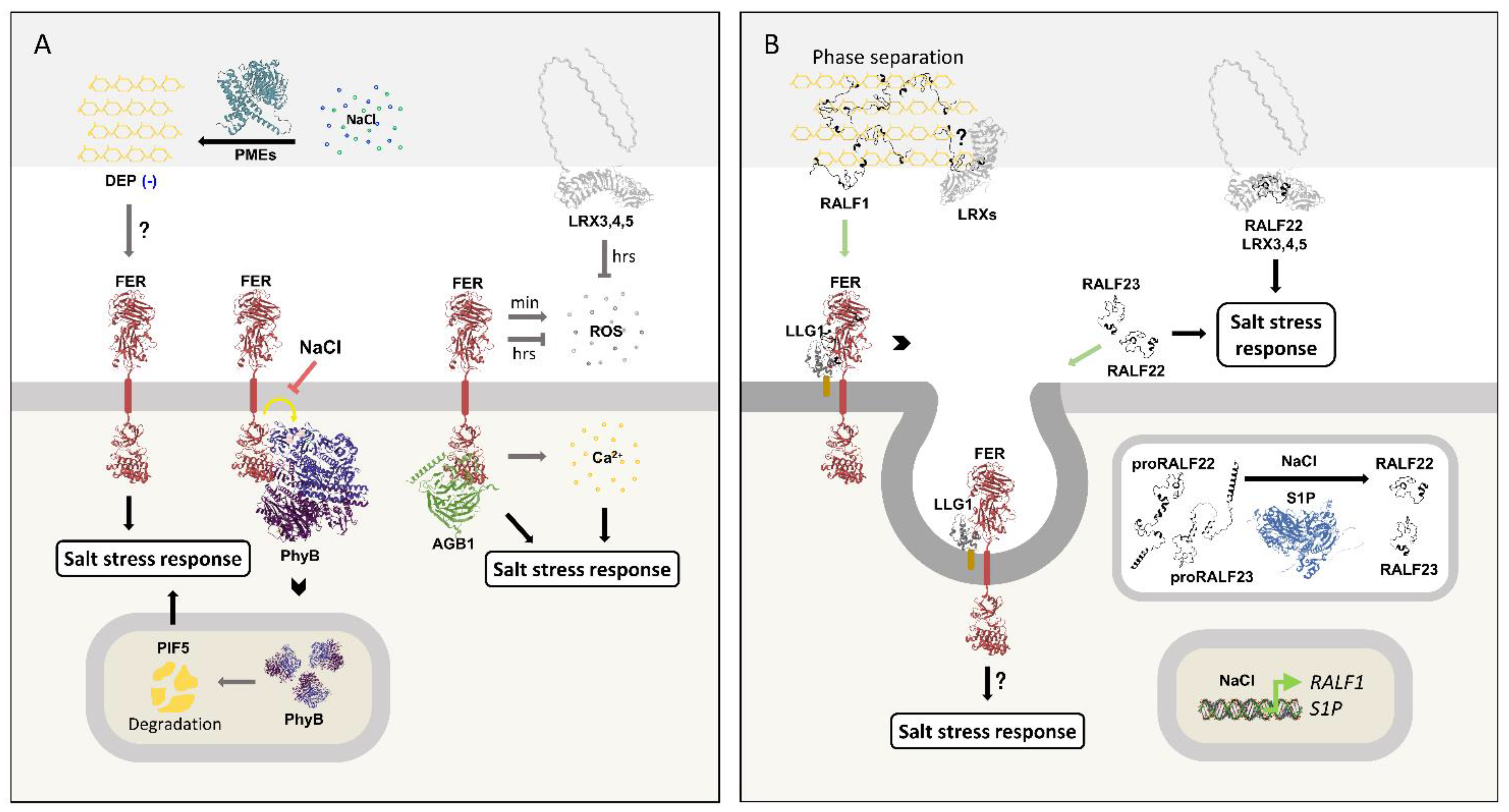

FER plays a central role in regulating salt stress response, as attested by the salt-hypersensitive phenotype of the fer-4 mutant (33,56). Under NaCl treatment, FER and AGB1 positively regulate short-term (minutes) and negatively regulate long-term (hours) ROS production (56). Additionally, FER directly regulates the dynamic phosphorylation of COMPANION OF CELLULOSE SYNTHASE 1 (CC1) under salt stress, potentially influencing microtubule organization (136). Salt treatment also inhibits FER’s autophosphorylation and its direct phosphorylation of phytochrome B (phyB). The latter increases phyB abundance in the nucleus, which in turn promotes PIF5 degradation, an important step in a controlled salt-stress response (137).

Salt treatment enhances PME activity, which is required for the salt-induced transcriptional response and phosphorylation of MITOGEN-ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE 6 (MPK6). These characteristic responses are increased in

fer-4, and chemical inhibition of PME activity alleviates the mutant hypersensitivity, suggesting that FER may sense salt-induced cell wall modifications to regulate subsequent intracellular signaling (138). FER’s role as a CW sensor in BR-induced growth, and its regulation by RALFs, further support this hypothesis (76). Moreover, during the recovery phase from salinity stress, a rise in [Ca

2+]

cyt mediated by FER is necessary for maintaining CWI (33). FER-regulated salt-stress responses with unconfirmed RALF involvement are summarized in

Figure 9A.

Salt induces RALF1 transcription and raises de-esterified pectin levels in the cell wall. These changes increase RALF1 and DEP phase separation, leading to the formation of membrane micro- and nanodomains enriched with FER, LLG1, FLS2 and BRI1 that undergo intense endocytosis. This mechanism may act as a general regulator that integrates and coordinates the biotic and abiotic stresses responses. This assembly also regulates FER/LLG1-induced ROS production under normal conditions and potentially during salt stress (27). Notably, the combined treatment of NaCl and RALF22 or RALF23 also promotes FER internalization (17).

The cell wall-associated proteins LRX3,4,5 are expressed in vegetative tissues and are essential to salt stress tolerance. Part of their role arises from the negative regulation of long-term (hours) ROS production during salinity response, as seen with FER (133). Another part involves their binding to RALF22 and RALF23 in a still poorly understood dynamic (17). NaCl induces S1P subtilase transcription and processing of proRALF22 and proRALF23 (17,27). In turn, plants overexpressing RALF22 or RALF23 and the lrx345 triple mutant are hypersensitive to NaCl treatment. Strikingly, this phenotype is partially reversed in the quadruple mutants s1p/lrx345 and ralf22/lrx345 (17), suggesting a complex mechanism, discussed below. The salt-hypersensitivity of both lrx345 and fer-4 is also reversed by a phyB loss-of-function mutant and a PIF5 overexpressor line, further supporting the joint action of these RALF receptors (137). RALF involvement in the phyB/PIF-mediated response, however, remains to be investigated.

The findings mentioned above should be carefully analyzed. As described, RALF1/DEP phase separation may play a positive role in salinity stress tolerance (27). Nonetheless, RALF1 and NaCl combined treatments disrupt the plant's Na

+/K

+ ionic homeostasis in a FER-dependent manner, leading to salt hypersensitivity (56). Thus, the negative effects of RALF1 treatment and

RALF22 or

RALF23 overexpression on salinity tolerance might stem from an imbalanced response, that otherwise has a positive effect when the peptides are present at endogenous levels. The salt-induced transcription of

RALF1 and processing of proRALF22 and proRALF23 contribute to this assumption (17,27). Alternatively, RALF peptides might be part of a negative feedback loop that finely regulates the stress response. In line with both possibilities, the partial reversal of

lrx345 mutant salt hypersensitivity phenotype by diminishing RALF’s presence (as seen in the

s1p/lrx345 and

ralf22/lrx345 mutants) points to a response that relies on an equilibrium involving RALFs and LRXs. A single split luciferase complementation assay showed that the RALF22/LRX3 interaction is disrupted by NaCl (17). This binding dynamic might be central to an apoplast sensing mechanism, although it must be confirmed by other approaches. In root hairs, RALF22 interacts with LRXs and DEP (29). Given the RALF1/DEP phase separation induction by NaCl, and the importance of LRXs for salt stress tolerance, there is a potential role for the RALF/LRX/DEP assembly in this context. In summary, the involvement of RALF peptides in the salinity stress response still holds many questions (

Figure 9B).

Figure 9.

RALF peptides and their receptors are involved in the salinity stress response.

Figure 9.

RALF peptides and their receptors are involved in the salinity stress response.

A) FER plays a central role in regulating the salt stress response. Salt treatment enhances PME activity, which triggers intracellular signaling. FER regulates this response, potentially by sensing changes in cell wall composition, particularly the PME-generated de-esterified pectin (DEP; depicted in yellow). Salt also inhibits FER-mediated phosphorylation of phyB, thereby increasing phyB accumulation in the nucleus. This promotes PIF5 degradation and contributes to tolerance. Furthermore, in the presence of NaCl, FER positively regulates short-term (minutes) ROS production, while FER and LRX3,4,5 negatively regulate long-term (hours) ROS production. FER is also essential for cell recovery after salt stress by modulating calcium influx. Finally, FER and AGB1 have a synergistic effect on NaCl tolerance, but, as with the above-mentioned responses, RALF involvement remains unexplored.

B) Salinity stress induces phase separation of RALF1 and de-esterified pectin, creating membrane micro- and nanodomains enriched in FER/LLG1, where endocytosis is intense. This response may be part of FER-mediated ROS regulation and potentially serves as a mechanism to regulate the salt stress response. RALF22 and RALF23 also induce FER internalization in the presence of NaCl. RALF22 binds to LRX3,4,5, and this interaction regulates salinity stress tolerance by a yet poorly understood mechanism. One possibility is that LRXs are part of the RALF/DEP phase separation. Additionally, the presence of NaCl induces RALF1 and S1P transcription, as well as proRALF22 and RALF23 processing by the subtilase.

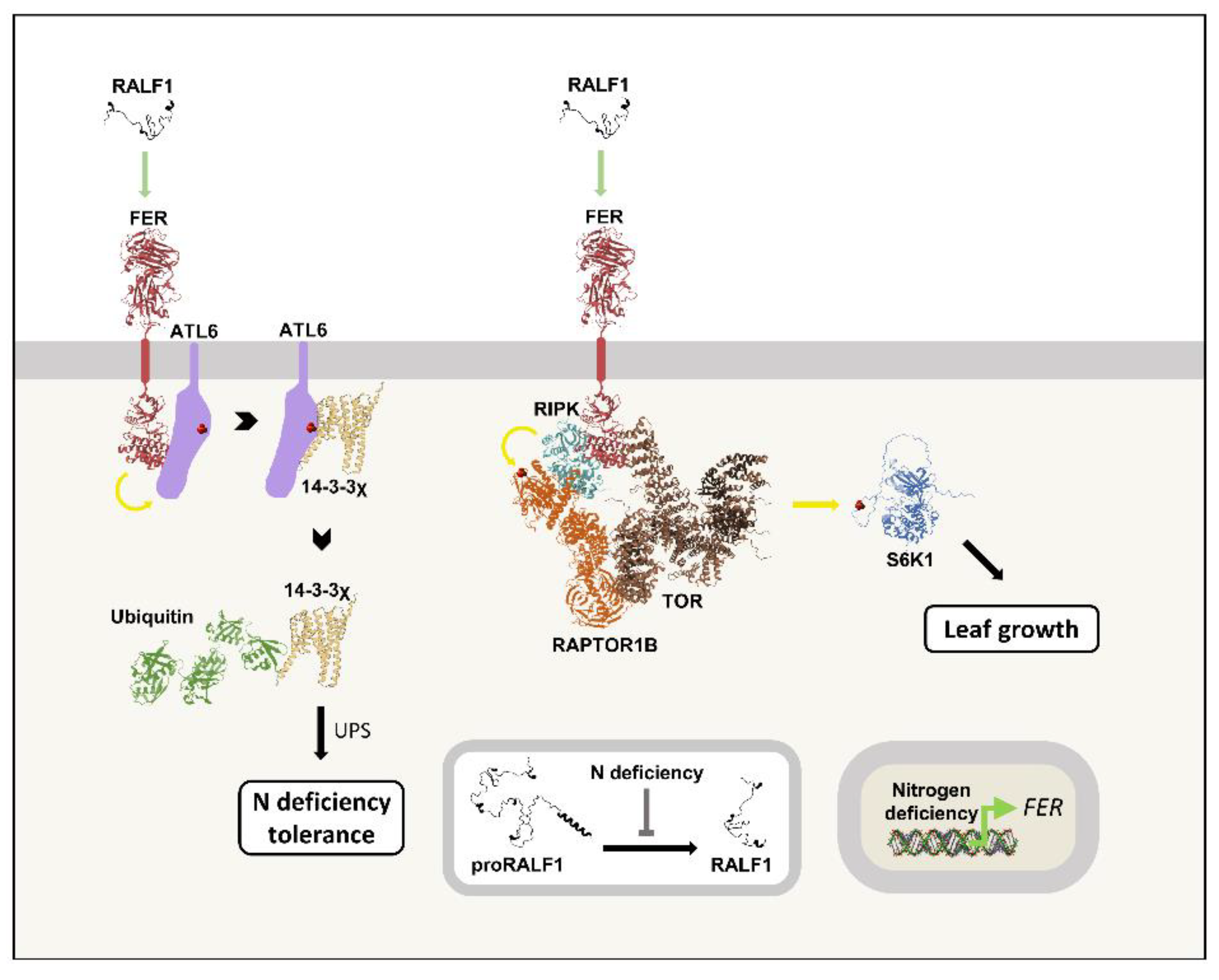

Nitrogen deficiency

A fine balance between carbon and nitrogen levels (C/N) is of great importance for plant metabolism. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) contributes to this balance through the degradation of 14-3-3 proteins, which are targeted to the system by the ubiquitin ligases ARABIDOPSIS TOXICOSIS IN YEAST (ATLs) (139). FER is part of this pathway, and its expression is induced in high C/N environments, hereafter also referred to as nitrogen deficiency. FER phosphorylates ATL6, which promotes ATL6/14-3-3χ interaction, leading to the ubiquitination of the latter and its subsequent degradation by the UPS. RALF1 stimulates 14-3-3χ degradation in a FER-dependent manner, and plants overexpressing RALF1 are more resistant to nitrogen deficiency than wild-type plants (140). In summary, RALF1 and FER are important for the adaptation to nitrogen-depleted media by modulating 14-3-3χ levels through ATL6.

The kinase TARGET OF RAPAMYCIN (TOR) is a master regulator of cellular nutrient status. TOR’s control of plant growth involves its canonical partner REGULATORY-ASSOCIATED PROTEIN OF TOR 1 (RAPTOR1) and the kinase PROTEIN-SERINE KINASE 6 (S6K1) (141). Under nitrogen deficiency, RALF1 treatment promotes RAPTOR1 phosphorylation and its interaction with TOR in a FER-dependent manner, potentially through RIPK (68,142). The TOR/RAPTOR interaction induces S6K1 phosphorylation, leading to an increase in shoot biomass (142). Therefore, in this pathway, RALF1 promotes growth, opposing its canonical role as a growth inhibitor (10,142). Curiously, nitrogen-depleted media negatively regulate both proRALF1 processing and FER phosphorylation (142). This signal to decrease mature RALF1 presence, along with its positive role in nitrogen deficiency, indicates a finely regulated response. Notably, under normal conditions, FER activates TOR to induce growth and repress autophagy in roots (143), but RALF1 involvement was not investigated.

Figure 10 summarizes RALF1's role in the nitrogen deficiency response.

IX. Biotic Stresses

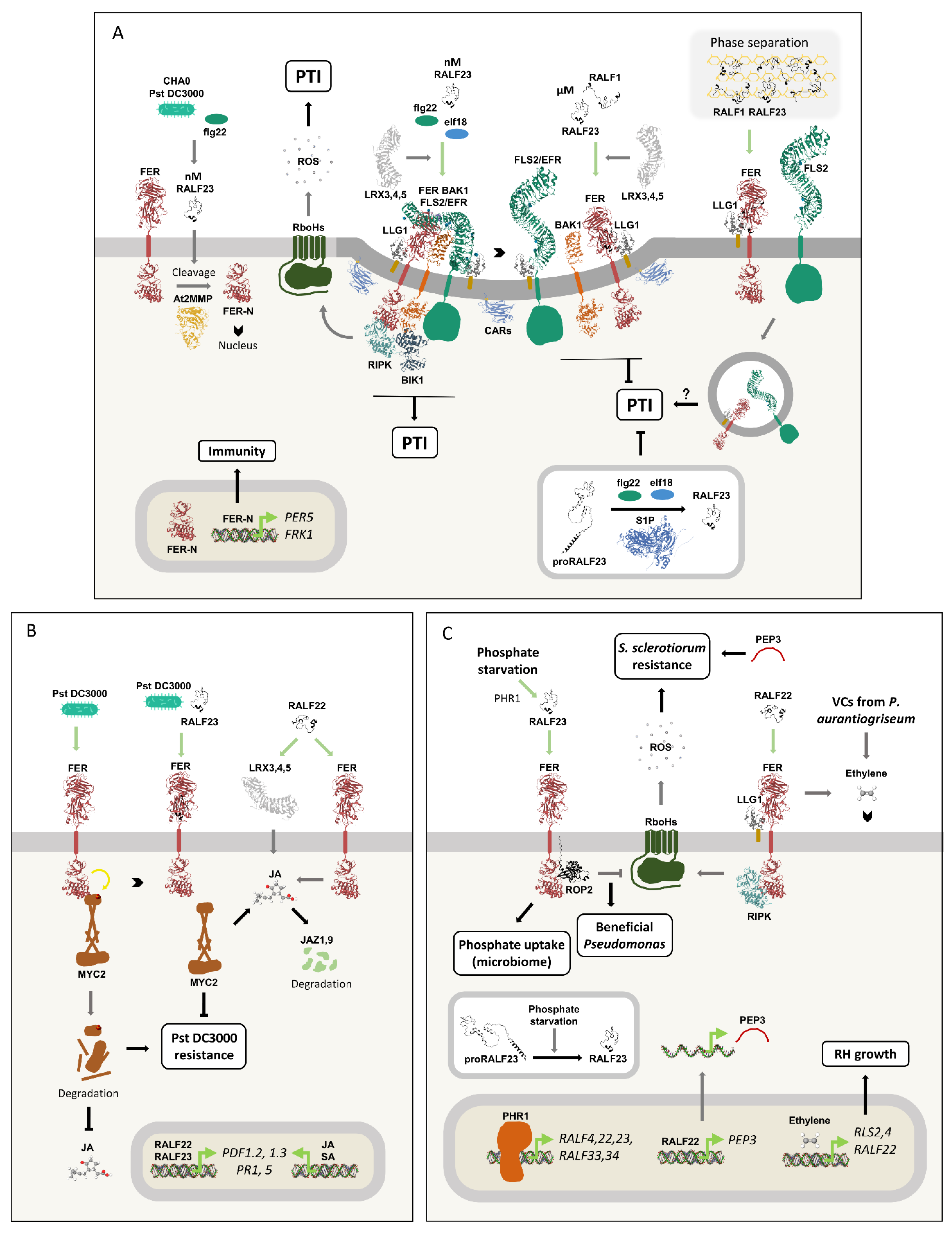

Crosstalk with biotic stress phytohormones

The phytohormones jasmonic acid (JA) and salicylic acid (SA) play crucial roles in the defense against pathogens (144). Plant lines that overexpress RALF22 or RALF23, and the loss-of-function mutants fer-4 and lrx345, have considerably higher levels of SA and, especially, JA. Accordingly, these mutants display an increased expression of the JA- and SA-responsive genes PDF1.2 and PDF1.3, as well as PR1 and PR5. The JASMONATE-ZIM-DOMAIN (JAZ) proteins are repressors of the JA signaling pathway that get degraded in the presence of the hormone (144). RALF22 treatment induces the degradation of JAZ1 and JAZ9 in a FER- and LRX3,4,5-dependent manner (133).

The transcription factor MYC2 plays a pivotal role in JA signaling (144). FER phosphorylates MYC2, leading to a decrease in its protein levels. The consequent reduction of JA signaling confers resistance to the bacterium

Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (Pst DC3000). The binding of RALF23 to FER inhibits MYC2 phosphorylation, increasing the TF's stability and its mobilization to the nucleus, where MYC2 activates JA signaling. Consequently, plants treated with RALF23 become susceptible to Pst DC3000 (145). Collectively, these results point to a crosstalk between RALFs, jasmonic acid, and salicylic acid, which relies on FER and LRX3,4,5 (

Figure 11B).

Pattern-triggered immunity

In order to deal with the threats posed by numerous pathogens, plants first need to recognize them. To achieve this, the membrane-associated Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs) perceive molecules derived from infectious organisms, known as Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs) (146). Two of the most studied PRRs are FLAGELLIN-SENSITIVE 2 (FLS2) and ELONGATION FACTOR TU RECEPTOR (EFR), the receptors of bacteria-derived flagellin (flg22) and translation factor EF-Tu (elf18), respectively. Both FLS2 and EFR function alongside the coreceptor BAK1 (147). PAMP perception by PRRs elicits the Pattern-Triggered Immunity (PTI), and a key initial step of this immune response is the controlled production of ROS by NADPH oxidases (148).

RALF peptides have opposite effects on immunity depending on their concentrations. At high levels (µM range), these peptides negatively regulate PTI by altering the PRRs’ membrane dynamics. Flg22 and elf18 treatment induces the formation of FLS2/BAK1 and EFR/BAK1 complexes, respectively. FER's extracellular domain stabilizes these complexes, leading to ROS production and resistance to Pst DC3000 (16,149). Upon 1 µM treatment, RALF23 inhibits the PTI response by binding to FER and compromising its role in stabilizing the PRR complexes, which then dissociate (16). Also through FER, high concentrations of RALF23 promote opposite membrane mobility behaviors of FLS2 and BAK1, which may either result from or contribute to the peptide-induced FLS2/BAK1 dissociation. Notably, RALF23's negative control of PTI also depends on FER’s kinase activity, and is not restricted to the receptor’s extracellular interactions with PRRs (149).

The FER homolog ANX1, mainly known for its RALF-regulated role in reproduction, is also expressed in vegetative tissues (41,150,151). Contrary to FER, ANX1 binds to BAK1 and reduces the flg22/FLS2/BAK1 complex formation, negatively regulating PTI. ANX1 also suppress the Effector-Triggered Immunity (ETI) (151). Whether RALFs participate in these ANX1-modulated responses remains unknown.

The coreceptor LLG1 is essential for the RALF23/FER inhibition of elf18-induced ROS production (18). LLG1 also interacts with EFR and FLS2, participating in the PAMP-induced, BAK1-mediated phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic kinase BOTRYTIS-INDUCED KINASE1 (BIK1), which triggers ROS burst (152). Since LLG1 is involved in both PTI induction by PAMPs and its repression by RALF23, it may function as a molecular switch, determining the signaling output. Alternatively, LLG1 may function solely as a coreceptor in both contexts.

LRX3,4,5 are also involved in PTI regulation. Like FER, these cell wall-associated proteins are important for stabilizing the flg22/FLS2/BAK1 complex, leading to ROS production. RALF23's antagonism on this response also depends on LRX3,4,5, although the mechanism is still obscure (149). The similar roles of FER and LRXs in PTI become even more intriguing given their ability to bind each other (40,149). It is worth noting that RALF23 does not modulate this interaction (149), raising questions about its biological significance.

RALF1 also negatively regulates the PTI response when administered at 1 µM. RALF1/FER binding induces CARs' nanodomain formation, which contributes to the FER-mediated stabilization of the flg22/FLS2/BAK1 complex. Like RALF23, RALF1 promotes the dissociation of this PTI complex, a process further facilitated by CARs (117). Remarkably, the RALF1, RALF23 and de-esterified pectin phase separation induces the formation of membrane domains enriched in FER, LLG1, and FLS2, where endocytosis is intense (27). Considering the players involved, RALF-triggered endocytosis may contribute to PTI modulation.

It wasn’t until recently that Feng Yu’s lab showed that RALF23’s effect on immunity is concentration-dependent. Treatment with flg22 and infection with Pst DC3000 or the commensal rhizobacterium P. protegens strain CHA0 induce an increase in mature RALF23, reaching endogenous concentrations of 100–200 nM. At these levels, RALF23 promote cleavage of FER's intracellular domain by MATRIX METALLOPROTEINASE 2 (At2MMP), releasing the N-terminal portion of FER (FER-N) from the plasma membrane. FER-N then translocates to the nucleus, inducing the expression of the immunity genes PER5 and FRK1, enhancing flg22-induced FLS2/BAK1 complex formation and increasing ROS production (13). On the other hand, treatment with 1 µM RALF23 resulted in the opposite responses (13,16,149).

The processing of proRALFs is part of PTI regulation. Both elf18 treatment and Pst DC3000 infection induce proRALF23 processing by the subtilase S1P, and this step is essential for the peptide-triggered PTI inhibition. RALF33 and RALF34 also possess a putative S1P cleavage site and inhibit elf18-induced ROS production. In contrast, RALF17, a peptide without the site, induces PTI (16). Accordingly, a family-wide study of RALFs from A. thaliana pointed to a strong tendency for peptides with the predicted S1P cleavage site to inhibit elf18-induced ROS production and peptides without the site to increase it (5). Nevertheless, exceptions like RALF22 exist, which possess the cleavage site and induce ROS (57).

Other proteins act downstream of RALFs in the PTI modulation. RALF1’s negative effect on flg22-induced ROS production is compromised in a

GRP7 interference mutant (11). In turn, mutants lacking EBP1, a negative regulator of RALF1 signaling, exhibit an even greater reduction in ROS levels under simultaneous treatment with flg22 and RALF1 (84). Furthermore, ROS burst triggered by RALF22 is reduced in

RBOHD,

LLG1,

BIK1 or

RIPK knockout mutants (57). Collectively, these results indicate that some proteins involved in the RALF-induced growth inhibition signaling are also part of the peptides' immunity modulation.

Figure 11A depicts the different aspects of RALFs’ regulation of PTI.

Plant-microorganism interactions

The biological and evolutionary basis of RALFs’ role in immunity modulation is now being unraveled. Under normal growth conditions, RALF23 is expressed in the root stele. In the presence of the pathogenic Pst DC3000 or the commensal Pseudomonas CHA0, RALF23 expression and propeptide processing extend to the outer cell layers of the transition and elongation zones. The mature peptide induces the previously cited cleavage of FER’s intracellular domain and its translocation to the nucleus, where it upregulates immunity genes, resulting in a localized immune response in the root (13). More broadly, FER generates basal root ROS levels through ROP2 and RboHD, which are detrimental to beneficial bacteria of the genus Pseudomonas. This response is opposed by RALF23 at high concentrations, leading to an enrichment of these pseudomonads in the root microbiome (62).

RALF23 also modulates the microbiome composition under phosphate (Pi) starvation through the transcription factor PHOSPHATE STARVATION RESPONSE 1 (PHR1). In response to Pi deprivation, PHR1 binds to the promoters of RALF4,22,23,33,34, upregulating their expression. In addition, phosphate scarcity induces proRALF23 processing, and the increased levels of mature RALF23 reduce the immune response and alters the microbiota composition by favoring the enrichment of bacteria beneficial for Pi uptake (153). In this response, RALF23 acts in a FER-dependent manner through the PRR complex disassembly mechanism described earlier (16,153). The effects of RALF23 under different microbial interactions provide examples of how modulation of peptide concentration, and not just its presence, achieves context-specific immunity.

RALF22 positively regulates the immune defense against the necrotrophic fungi Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. RALF22 treatment triggers ROS production and reduces fungal colonization in a FER/LLG1-dependent manner. RALF22 also promotes the transcription and translation of PEP3, a peptide that amplifies the immune response. Furthermore, RALF22 treatment increases resistance to S. sclerotiorum in different species of the Brassica genus, indicating a conserved response (57).

Plant-interacting microorganisms emit small volatile compounds (VCs, <300 Da) that trigger plant reactions. VCs produced by the pathogenic fungus

Penicillium aurantiogriseum induce changes in Arabidopsis root architecture, such as the hyper-elongation of RHs (154). Notably, these compounds upregulate

RALF22 transcription and both

ralf22 and

fer-4 mutants are less sensitive to VC-triggered RH elongation. Ethylene is the primary VC candidate to promote these root changes, as its precursor ACC induces RH growth in wild-type plants but not in

ralf22 or

fer-4. Consistently, VCs upregulate the ethylene-inducible, RH growth-promoting genes

RSL2 and RLS4 in a RALF22/FER-dependent manner. Taken together, these results suggest that, upon

P. aurantiogriseum infection, the VC-induced RH growth is mediated by ethylene in a signaling pathway that depends on RALF22/FER and RSL2,4 (105).

Figure 11C summarizes the first examples of how plants use RALFs to mediate complex interactions with both beneficial and pathogenic microorganisms.

Figure 11.

RALF peptides modulate immune responses.

Figure 11.

RALF peptides modulate immune responses.

A) The presence of Pseudomonas DC3000 and CHA0, as well as flg22, raises mature RALF23 concentrations to 100–200 nM, which in turn triggers FER’s N-terminal cleavage by AtMMP. FER-N translocates to the nucleus, where it upregulates the immune-related genes PER5 and FRK1, thus promoting immunity. At the membrane, FER stabilizes the PRR complexes in micro- and nanodomains assembled by CAR proteins. Active PRR complexes trigger ROS production by RboHs in a RIPK- and BIK1-dependent manner. At high concentrations (µM), the binding of RALF1 or RALF23 to FER induces the dissociation of these complexes, thereby inhibiting the PTI response. LRX3,4,5 are also involved in this mechanism. In addition, RALF1 and RALF23 bind to de-esterified pectin (depicted in yellow) and induce phase separation, forming membrane microdomains where FER, LLG1, and FLS2 endocytosis is intense, potentially contributing to the modulation of PTI. Notably, flg22 or elf18 treatment induce proRALF23 processing by S1P.

B) FER negatively regulates the jasmonic acid (JA) signaling pathway by phosphorylating MYC2, leading to its degradation. This increases resistance against Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (Pst DC3000). RALF23 binds to FER and inhibits MYC2 phosphorylation, thereby preserving its integrity, favoring the JA pathway, and consequently leading to plant susceptibility to Pst DC3000. RALF22 increases JA levels and induces JAZ1 and JAZ9 degradation in a FER- and LRX3,4,5-dependent manner. Moreover, RALF22, RALF23, JA, and salicylic acid (SA) induce the transcription of PDFs and PRs.

C) Phosphate starvation induces the expression of RALF genes through the transcription factor PHR1, as well as the processing of proRALF23. Mature RALF23 presence decreases the PTI response, enriching the root microbiome with microorganisms that promote phosphate uptake. FER triggers basal ROS production by RboHs through ROP2. This response is repressed by RALF23 ligation, enriching the microbiome with beneficial Pseudomonas. Moreover, RALF22 induces PTI response and the defense peptide PEP3 transcription and translation, leading to resistance against the fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Ethylene is among the volatile compounds (VCs) secreted by the pathogenic fungus Penicillium aurantiogriseum, and this phytohormone upregulates the expression of RSL2, RSL4, and RALF22, leading to RH growth. RALF22 and FER are essential positive regulators of this response.

Certain fungal species possess genes homologous to plant RALFs, and the polyphyletic origin of these RALF-like genes suggests an acquisition through lateral transfer (8). At least some of them are functional, as attested by FgRALF from Fusarium graminearum, expressed during wheat (Triticum aestivum) infection. The peptide FgRALF is capable of binding to Arabidopsis' FER and its wheat homologue TaFER, suppressing the PTI response in both species (155). Likewise, FoRALF, a peptide from the related species Fusarium oxysporum, negatively regulates immunity in tomato plants (Solanum lycopersicum) and is less effective at infecting the Arabidopsis fer-4 mutant than the wild-type (156). Strikingly, the root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne incognita) also possesses RALF-like genes (MiRALF), four in total. Treatment of Arabidopsis with MiRALF1 or MiRALF3 induces MYC2 degradation and suppresses flg22-induced ROS production in a FER-dependent manner. As expected, these two peptides are secreted during M. incognita infection, bind to FER and enhance the nematode pathogenicity (9).

The results described above suggest a similar mechanism of action between RALF23 and the RALF-like peptides, which dampen the host defense to function as effectors of pathogenicity. Remarkably, the endophytic fungus Colletotrichum tofieldiae also produces a RALF-like peptide that represses Arabidopsis’ immune response in a FER-dependent manner, facilitating its root colonization. However, this interaction benefits the plant by contributing to root growth under Pi starvation (157), illustrating the versatility with which different microorganisms employ RALF-like peptides.

X. Reproduction

Regulation of flowering time

RALF peptides are intimately involved in Arabidopsis reproduction. Among the events regulated by these peptides is flowering time. This complex process involves the convergence of diverse signals in the production of florigens, such as the protein FLOWERING LOCUS T (158). The transcription factor FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) and its homologues, MADS AFFECTING FLOWERING (MAFs), suppress flowering by repressing the transcription of FLOWERING LOCUS T (159,160). RALF1 negatively regulates flowering in a FER-dependent manner by inducing the expression and alternative splicing (AS) of FLC, as well as the AS of MAF1, MAF2, and MAF3. FER also contributes to floral transition by positively regulating the transcription of circadian clock genes (161).

Pollen germination and penetration in the stigma

RALF peptides play crucial roles in various steps of the pollen path leading to fertilization. Pollen grains (PG) adhere to the stigma, where they germinate and initiate pollen tube (PT) growth. The PG's hydration is essential for its germination and is mediated by the exchange of signals with the female tissue (162). RALF23 and RALF33 are secreted by the stigma, where they induce ROS production, which represses PG hydration. To this end, these RALFs binds to the FER/ANJ/LLG1 complex, activating the NADPH oxidase RboHD through ROP2 (32). The RALF23,33/FER/ANJ complex also induces the phosphorylation of the proton pump AHA2 at its inhibitory residue, thus retaining H⁺ at the cytosol (44). Aquaporin gating is regulated by protonation (163), and the low intracellular pH maintained by RALF23,33 signaling results in the protonation of PLASMA MEMBRANE INTRINSIC PROTEINs (PIP1;1, 2;2, 2;5) and their subsequent closure (44). Upon pollen grain arrival, the pollen-produced peptide POLLEN COAT PROTEIN-Bγ (PCP-Bγ) outcompetes RALF23,33 for binding to the FER/ANJ/LLG1 complex (32,44). The newly formed PCP/FER/ANJ complex triggers phosphorylation at AHA2 activation sites, which pumps H+ outside the cell, releasing PIPs protonation and opening the water channel (44). The dislodging of RALF peptides by PCP-Bγ also leads to a decrease in ROS production by stigmatic cells, which, together with water efflux, results in PG hydration (32,44).

Plants have strategies to avoid interspecific pollination. The stigma produces RALF1,22,23,33 (sRALFs), which act as autocrine signals perceived by CrRLK1L complexes formed by FER, CVY1, ANJ, and/or HERK1. Meanwhile, the pollen tubes produce RALF10,11,12,13,25,26,30 (pRALFs), which function in a partially redundant manner. The binding of sRALFs to CrRLK1L complexes creates a blockage of PT penetration in the stigma through an unknown mechanism that does not involve ROS. The stigmatic proteins LRX3,4,5 bind to sRALFs and are also necessary for this blockage (24). Once the pollen arrives, pRALFs outcompete and dislodge sRALFs from the CrRLK1L complexes due to a higher binding affinity, 'unblocking' the PT penetration (24,26). This mechanism is responsible for an intergeneric hybridization barrier that prevents the penetration of PTs from distantly related

Brassicaceae species into the stigma of

A. thaliana. This barrier arises from the inability of

Brassicaceae pRALFs to dislodge Arabidopsis sRALFs from their receptors (24). The role of RALF peptides in pollen germination and penetration in the stigma is summarized in

Figure 12A.

Pollen tube growth

Pollen tubes are cells that undergo rapid, unidirectional growth, and are responsible for delivering male gametes to the ovule. At the PT’s tip, exocytosis of plasma membrane and cell wall material sustains rapid cellular expansion (162). Among the secreted cell wall components, pectins are of special importance due to their initial esterified state, which provides malleability to the growing apex, and their subsequent de-esterification, which rigidifies the PT flanks (164). At the PT’s apical region, ROPs/GEFs regulate RboHs, creating apoplastic ROS oscillations that modulate Ca²⁺ influx, and vice versa, a crucial dynamic for PT expansion (162,165).