Submitted:

26 March 2025

Posted:

26 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Temperature Treatments

2.2. Determination of Anthocyanin Content

2.3. Determination of Sugar Content

2.4. RNA Extraction and Transcriptome Sequencing

2.5. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA)

2.6. Phylogenetic Analysis

2.7. Transient Transformation of Lily Tepals

2.8. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

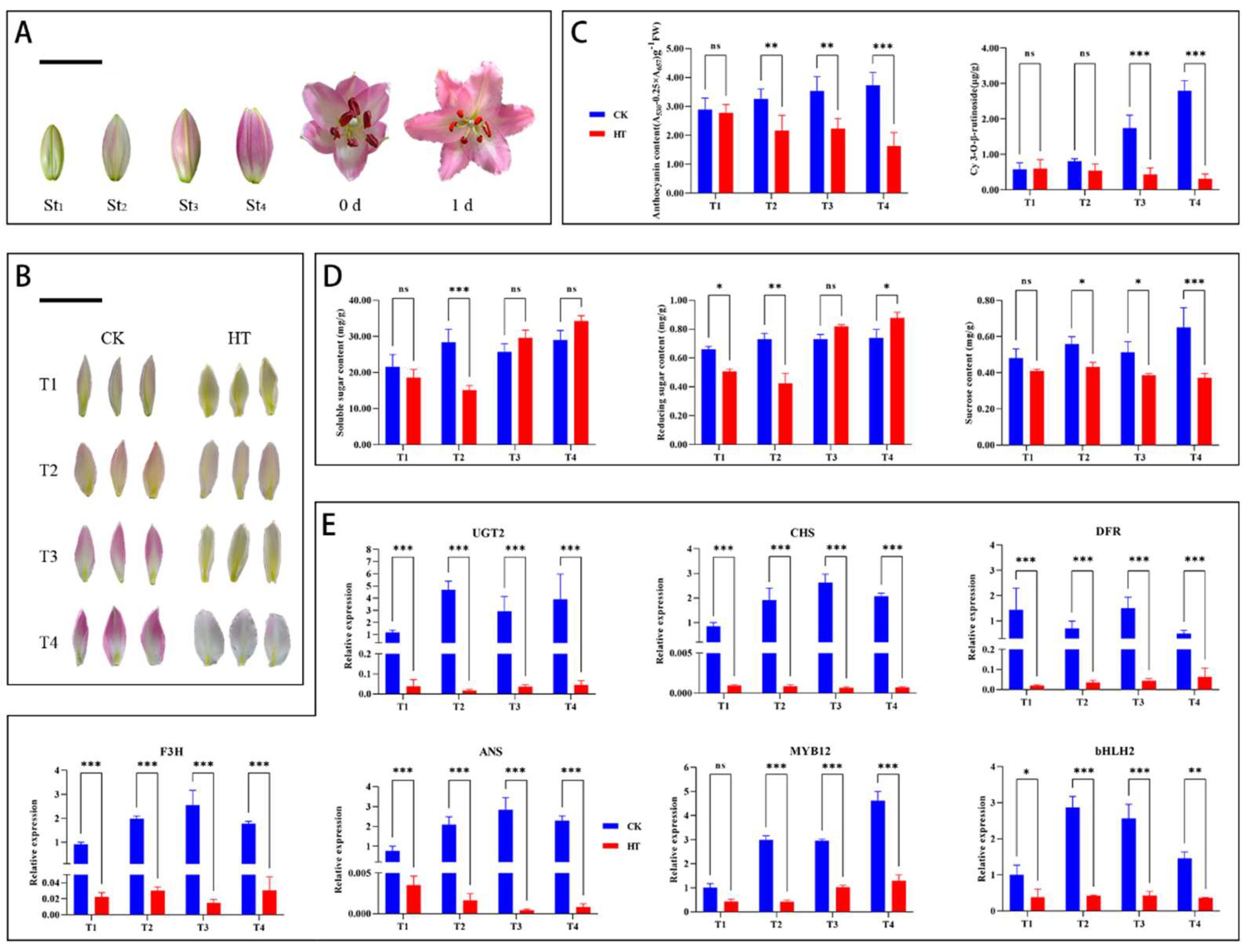

3.1. Effect of High Temperature on the Physiology and Biochemistry of Oriental Lily ‘Souvenir’

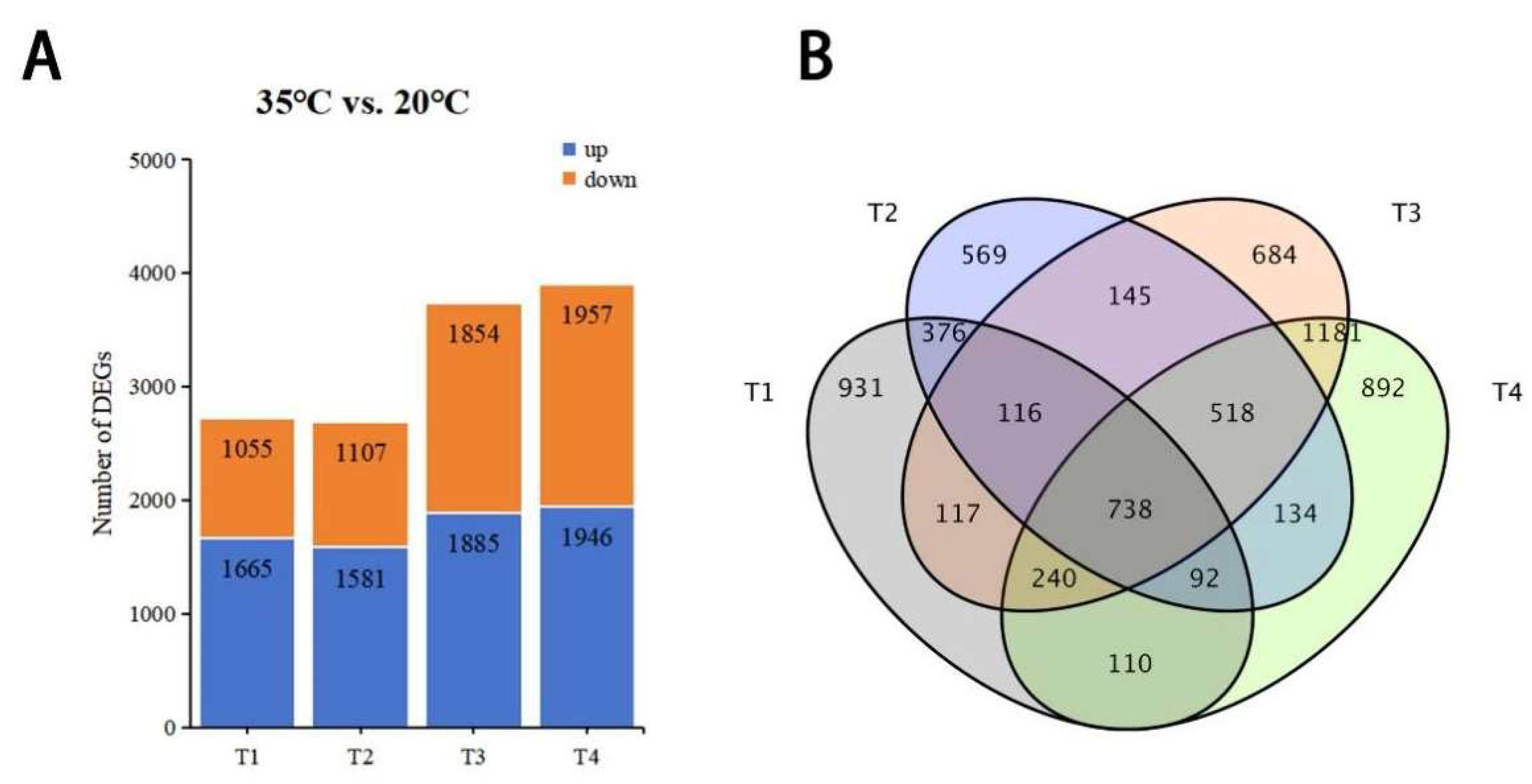

3.2. Gene Expression Differences Between NT- and HT-Treated Oriental Lily

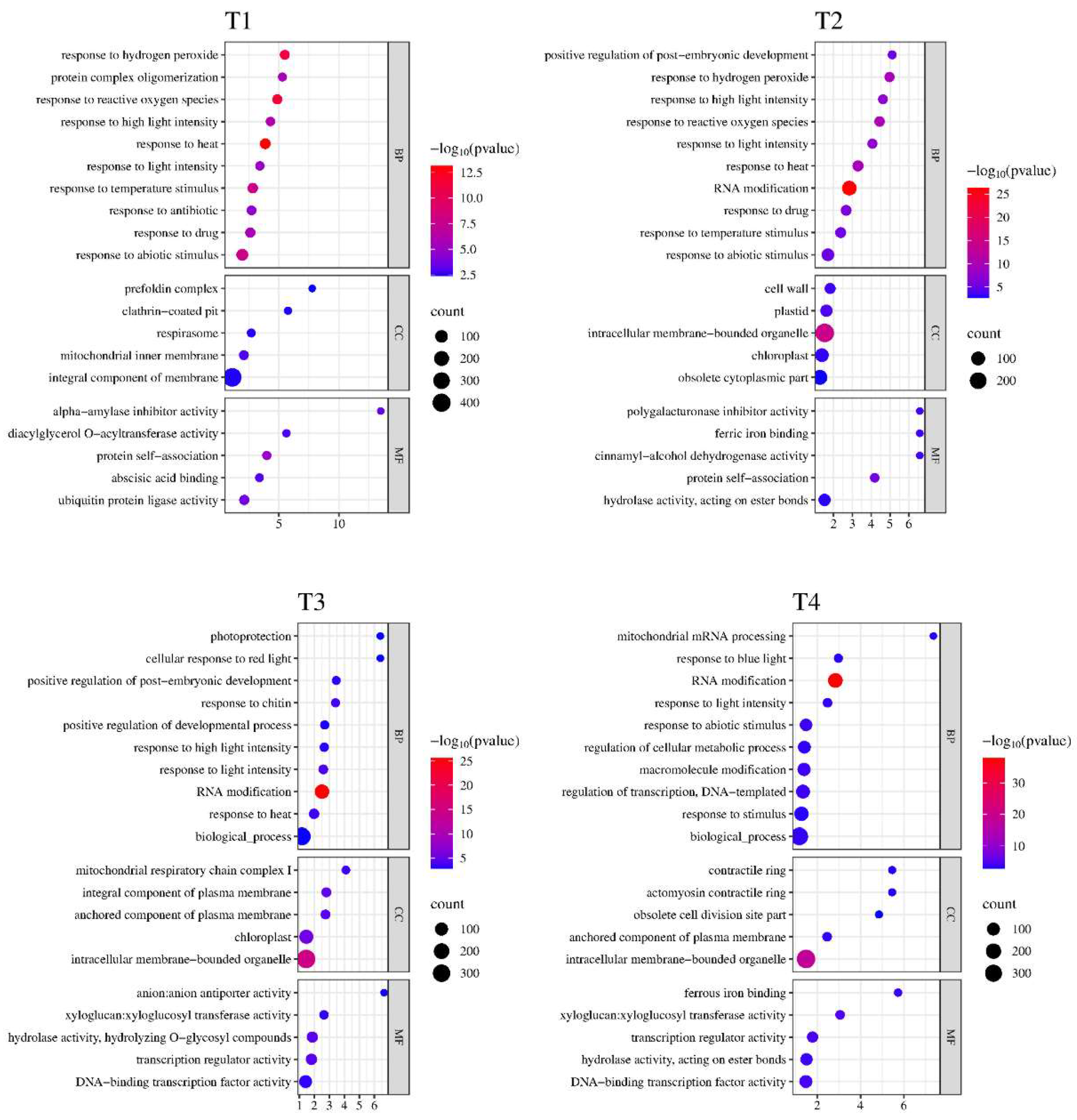

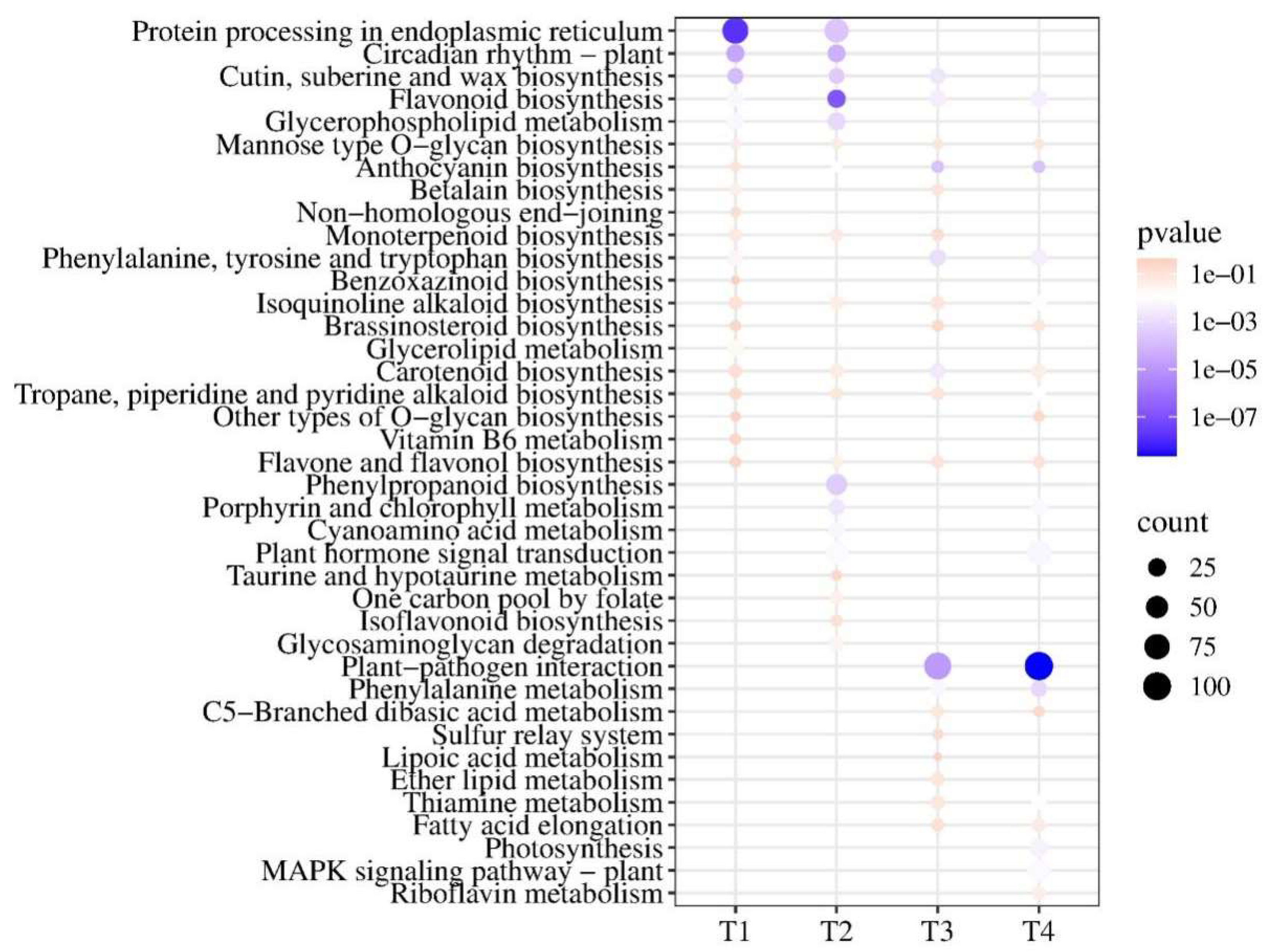

3.3. Functional Classification of DEGs

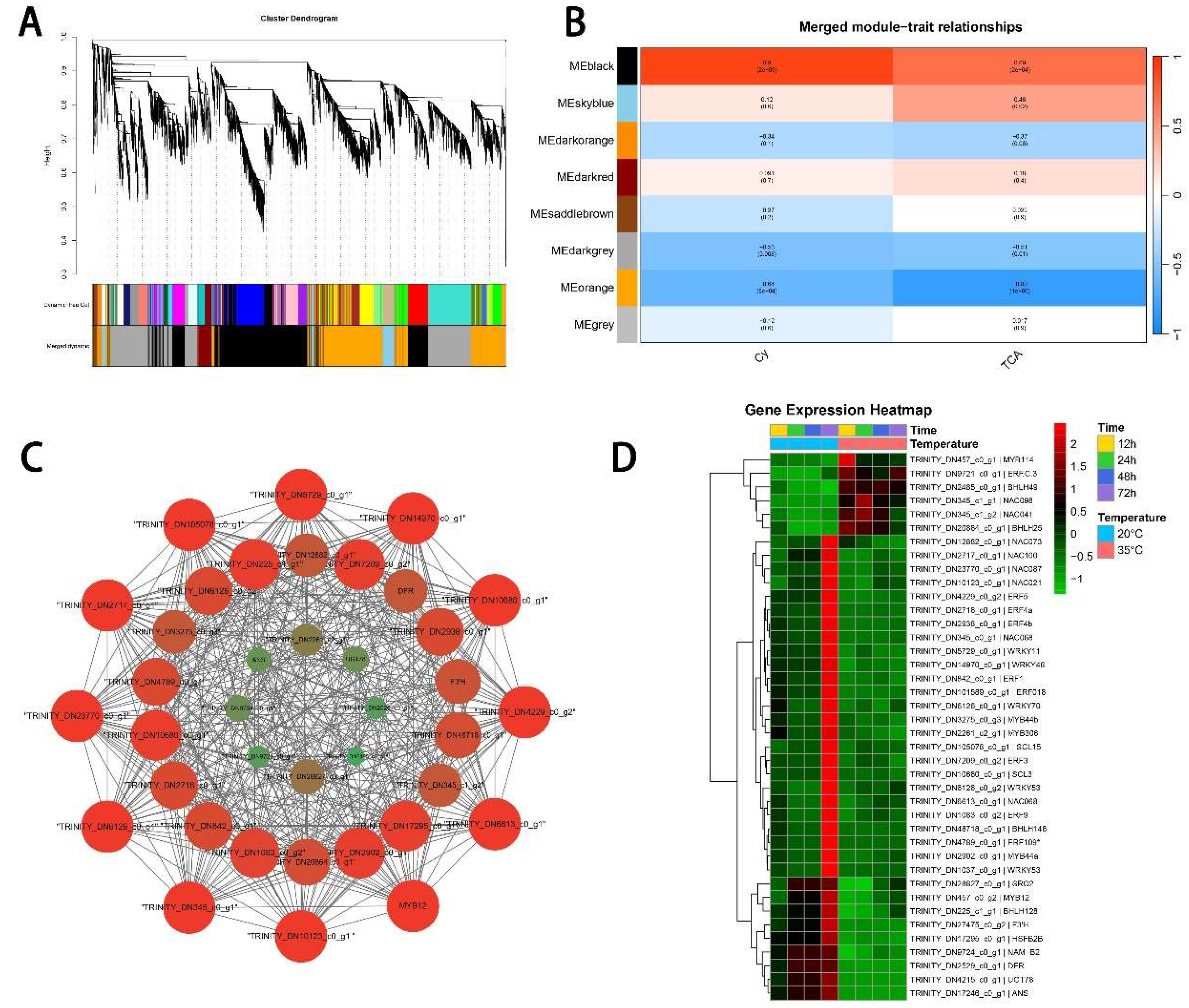

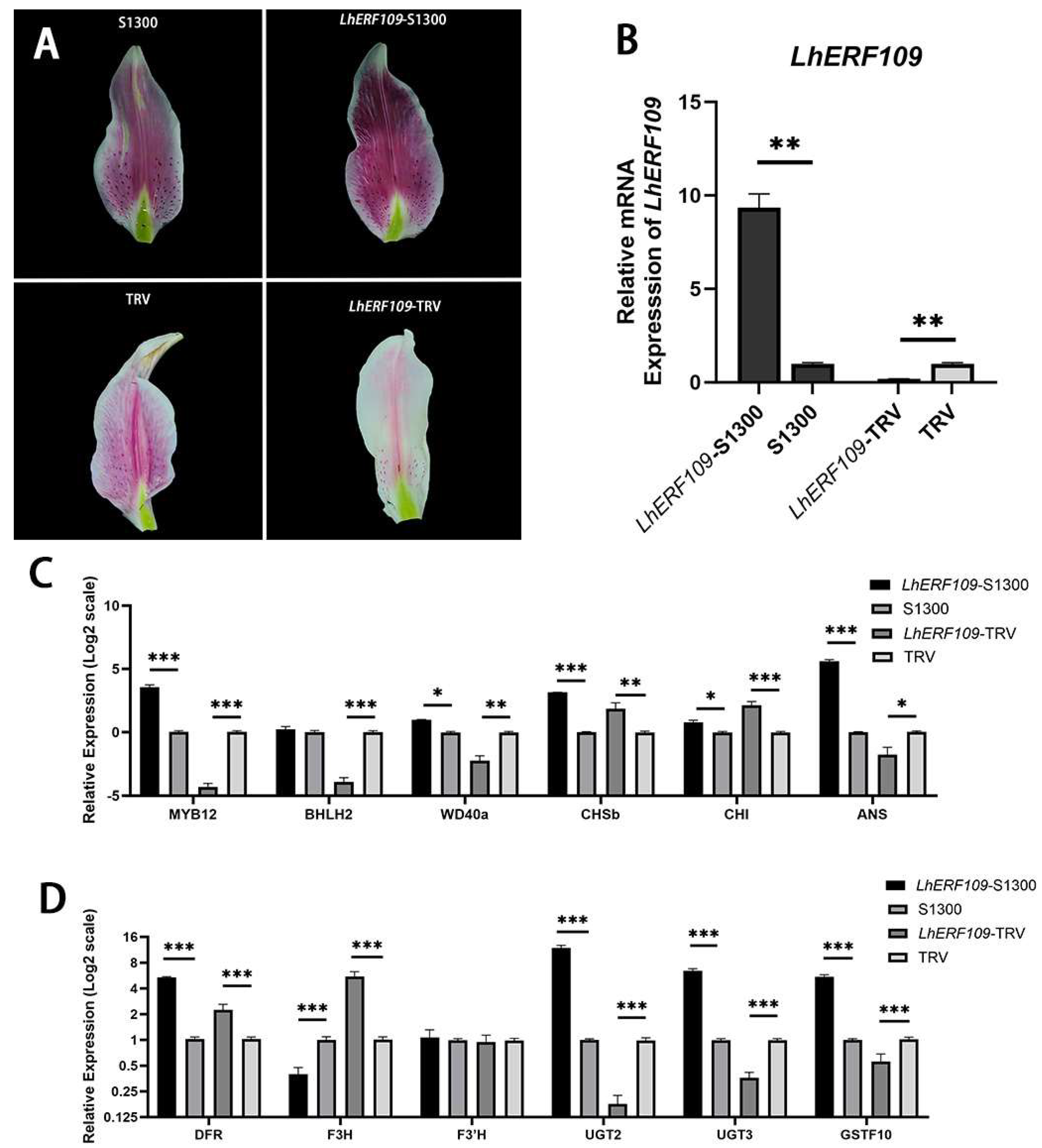

3.4. Anthocyanin-Related DEGs Revealed by Analysis of Co-Expression Networks

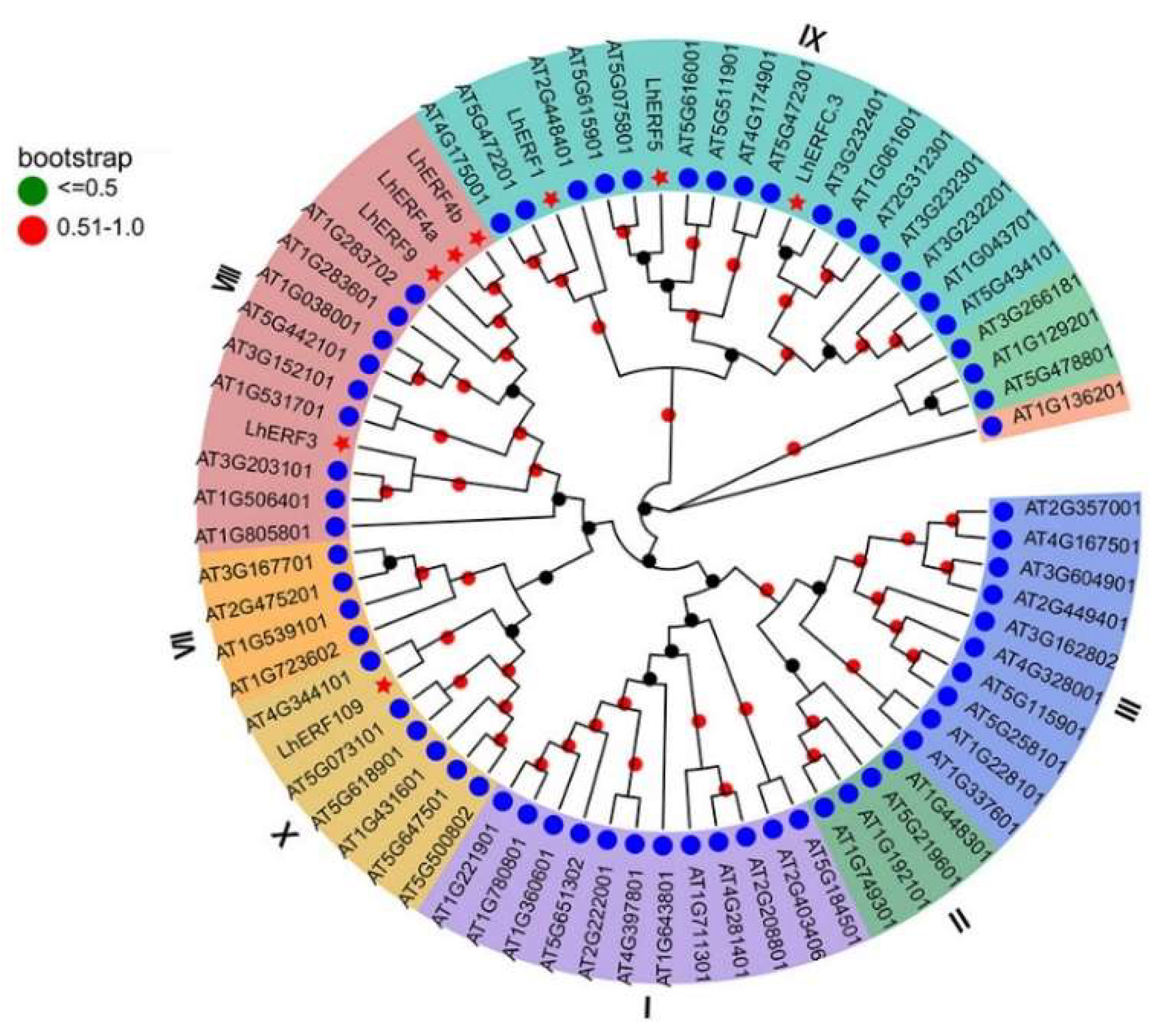

3.5. Phylogenetic Tree Construction of LhERF109

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, Z.; Wang, X.; Lin, X.; Mostafa, S.; Zou, H.; Wang, L.; Jin, B. Plant anthocyanins: Classification, biosynthesis, regulation, bioactivity, and health benefits. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 217, 109268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzoor, M.A.; Xu, Y.; lv, Z.; Xu, J.; Shah, I.H.; Sabir, I.A.; Wang, Y.; Sun, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, R.; Jiu, S.; Zhang, C. Horticulture crop under pressure: Unraveling the impact of climate change on nutrition and fruit cracking. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 357, 120759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamagishi, M.; Nakatsuka, T. LhMYB12, Regulating Tepal Anthocyanin Pigmentation in Asiatic Hybrid Lilies, is Derived from Lilium dauricum and L. bulbiferum. Hortic. J. 2017, 86, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Guo, C.; Chen, F.; Lv, B.; Song, J.; Ning, G.; He, Y.; Lin, J.; He, H.; Yang, Y.; Xiang, F. Heat-induced modulation of flavonoid biosynthesis via a LhMYBC2-Mediated regulatory network in oriental hybrid lily. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 214, 108966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Goto-Yamamoto, N.; Kitayama, M.; Hashizume, K. Loss of anthocyanins in red-wine grape under high temperature. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 1935–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin-Wang, K.; Micheletti, D.; Palmer, J.; Volz, R.; Lozano, L.; Espley, R.; Hellens, R.P.; Chagnè, D.; Rowan, D.D.; Troggio, M.; Iglesias, I.; Allan, A.C. High temperature reduces apple fruit colour via modulation of the anthocyanin regulatory complex. Plant Cell Environ. 2011, 34, 1176–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, D.D.; Cao, M.; Lin-Wang, K.; Cooney, J.M.; Jensen, D.J.; Austin, P.T.; Hunt, M.B.; Norling, C.; Hellens, R.P.; Schaffer, R.J.; Allan, A.C. Environmental regulation of leaf colour in red 35S Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, R.N.U.; You, Y.; Zhang, L.; Goudia, B.D.; Khan, A.R.; Li, P.; Ma, F. High Temperature Induced Anthocyanin Inhibition and Active Degradation in Malus profusion. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Tao, R.; Tang, Y.; Yin, L.; Ma, Y.; Ni, J.; Yan, X.; Yang, Q.; Wu, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Teng, Y. BBX16, a B-box protein, positively regulates light-induced anthocyanin accumulation by activating MYB10 in red pear. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 1985–1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, H.; Dong, Y.; Yue, X.; Hu, J.; Jiang, S.; Xu, H.; Wang, Y.; Su, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, N.; Chen, X. The B-box zinc finger protein MdBBX20 integrates anthocyanin accumulation in response to ultraviolet radiation and low temperature. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 2090–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Hwang, G.; Lee, S.; Zhu, J.-Y.; Paik, I.; Nguyen, T.T.; Kim, J.; Oh, E. High Ambient Temperature Represses Anthocyanin Biosynthesis through Degradation of HY5. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.H. HY5, an integrator of light and temperature signals in the regulation of anthocyanins biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. AIMSMOLES 2020, 7, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, M. Mechanisms by Which High Temperatures Suppress Anthocyanin Coloration in Flowers and Fruits, and Discovery of Floricultural Crops that Exhibit High-temperature-tolerant Flower Pigmentation. Hortic. J. 2024, 93, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, P.; Zhao, C.; Chen, Y.; Bi, Y. Phytochrome-interacting factors PIF4 and PIF5 negatively regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis under red light in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Sci. 2015, 238, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shan, X.; Gao, R.; Han, T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Kimani, S.; Wang, L.; Gao, X. MYB repressors and MBW activation complex collaborate to fine-tune flower coloration in Freesia hybrida. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, H.; Chen, Y.; Chen, M.; Yao, Y.; Luo, H.; Wu, Q.; Wang, F.; Zhou, Y. Analysis of Transcriptional and Metabolic Differences in the Petal Color Change Response to High-Temperature Stress in Various Chrysanthemum Genotypes. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Sun, Y.; Gao, Z.; Liu, X.; Guo, Q.; Sun, S.; Zhang, M.; Han, Y.; Irfan, M.; Chen, L.; Ma, D. LvbHLH13 Regulates Anthocyanin Biosynthesis by Activating the LvMYB5 Promoter in Lily (Lilium 'Viviana'). Horticulturae 2024, 10, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Song, G.; Zhang, F.; Shu, X.; Cheng, G.; Zhuang, W.; Wang, T.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z. Characterization of the WRKY Gene Family Related to Anthocyanin Biosynthesis and the Regulation Mechanism under Drought Stress and Methyl Jasmonate Treatment in Lycoris radiata. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Nolan, T.M.; Jiang, H.; Yin, Y. AP2/ERF Transcription Factor Regulatory Networks in Hormone and Abiotic Stress Responses in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, C.; Yu, J.; Li, T.; Yang, W.; Zhang, S.; Su, H.; Wang, L. A novel NAC transcription factor, MdNAC42, regulates anthocyanin accumulation in red-fleshed apple by interacting with MdMYB10. Tree Physiol. 2020, 40, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Du, W.; Sun, S.; Zhang, S.; Nie, M.; Liu, Y.; Irfan, M.; Zhang, L.; Chen, L. Ethylene positively regulates anthocyanin synthesis in "Viviana" lily via the LvMYB5-LvERF113-LvMYB1 module. Hortic. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, L.; Zhang, M.; Wu, T.; Song, T.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tian, J. MdWER interacts with MdERF109 and MdJAZ2 to mediate methyl jasmonate- and light-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in apple fruit. Plant J. 2024, 118, 1327–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassotti, A.; Gimelli, F. Bulb and cut flower production in the genus Lilium: Current status and the future. Acta Hortic. 2011, 900, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tuyl, J.M.; Arens, P. Lilium: Breeding history of the modern cultivar assortment. Acta Hortic. 2011, 900, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natenapit, J.; Taketa, S.; Narumi, T.; Fukai, S. Crossing of Allotriploid LLO Hybrid and Asiatic Lilies (Lilium). Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2010, 51, 426–430. [Google Scholar]

- Barba-Gonzalez, R.; Van Silfhout, A.A.; Visser, R.G.F.; Ramanna, M.S.; Van Tuyl, J.M. Progenies of allotriploids of Oriental × Asiatic lilies (Lilium) examined by GISH analysis. Euphytica 2006, 151, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Yong, X.; Zhu, J.; Xu, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Mou, L.; Zeng, L.; Wu, M.; Jiang, B.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, P.; Pan, Y. Chromosomal analysis of progenies between Lilium intersectional hybrids and wild species using ND-FISH and GISH. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1274883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.-S.; Yamagishi, M.; Suzuki, T. Elevated temperature inhibits anthocyanin biosynthesis in the tepals of an Oriental hybrid lily via the suppression of LhMYB12 transcription. Sci. Hortic. 2011, 132, 59–65. [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Chang, X.; Xian, L.; Zhang, J. Genome-wide identification of Pistacia R2R3-MYB gene family and function characterization of PcMYB113 during autumn leaf coloration in Pistacia chinensis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 192, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Liu, X.; Jiang, G.Z.; Liu, P.; Ji, L.X. Establishment of High Performance Liquid Chromatography Method for Determination of Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside in Black Rice Anthocyanins. Grain Food Ind. 2024, 31, 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Luo, Z.; Wu, X.; Shi, B.; Jiang, H.; Zhou, L.; Bai, L. Comparative Transcriptomic Analysis of Root Cadmium Responses in Two Chinese Rice Cultivars Yuzhenxiang and Xiangwanxian 12. J. Chem. 2021, 2021, 2166775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, H.; Wang, T.; Zhou, X.; Feng, X.; Tang, W.; Quan, J.; Bi, H. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression of the AP2/ERF Gene Family in Morus notabilis. Forests 2024, 15, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Irfan, M.; Chen, L.; Feng, Y. Regulation of MYB Transcription Factors of Anthocyanin Synthesis in Lily Flowers. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 699303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Li, W.-B.; Liu, H-F.; Chen, F-B. De novo transcriptome sequencing of radish (Raphanus sativus L.) fleshy roots: analysis of major genes involved in the anthocyanin synthesis pathway. BMC Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, Y.-F.; Wang, S.; Li, C-Z.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q-Y.; Wang, H-B.; Chen, X-S.; Feng, S-Q. Transcriptome Analysis of Apples in High-Temperature Treatments Reveals a Role of MdLBD37 in the Inhibition of Anthocyanin Accumulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienth, M.; Vigneron, N.; Darriet, P.; Sweetman, C.; Burbidge, C.; Bonghi, C.; Walker, R.P.; Famiani, F.; Castellarin, S.D. Grape Berry Secondary Metabolites and Their Modulation by Abiotic Factors in a Climate Change Scenario–A Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 643258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Han, X.; Wang, G.; Qiu, J.; Zhou, L.; Chen, S.; Fang, W.; Chen, F.; Jiang, J. Transcriptome analysis reveals chrysanthemum flower discoloration under high-temperature stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 983292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solfanelli, C.; Poggi, A.; Loreti, E.; Alpi, A.; Perata, P. Sucrose-Specific Induction of the Anthocyanin Biosynthetic Pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006, 140, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-J.; An, X-H.; Liu, X.; Hu, D-G.; Wang, X-F.; You, C-X.; Hao, Y-J. MdSnRK1.1 interacts with MdJAZ18 to regulate sucrose-induced anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin accumulation in apple. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 2977–2990. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Pang, X.; Xu, L.; Fang, R.; Huang, X.; Guan, P.; Lu, W.; Zhang, Z. Accumulation of soluble sugars in peel at high temperature leads to stay-green ripe banana fruit. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 4051–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Wen, B.; Xu, L.; Zong, X.; Sun, Y.; Wei, G.; Wei, H. High temperature inhibited the accumulation of anthocyanin by promoting ABA catabolism in sweet cherry fruits. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1137826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichimura, K.; Niki, T.; Matoh, M.; Nakayama, M. High temperature under low light conditions suppresses anthocyanin biosynthesis in snapdragon petals associated with decreased sugar levels. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 290, 110510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yu, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; Sui, Y. Promoting Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Purple Lettuce through Sucrose Supplementation under Nitrogen Limitation. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Sun, L.; Zhang, S.; Jiao, B.; Wang, J.; Ma, C. Integrated Transcriptomics and Metabolomics Analysis of Two Maize Hybrids (ZD309 and XY335) under Heat Stress at the Flowering Stage. Genes 2024, 15, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licausi, F.; Ohme-Takagi, M.; Perata, P. APETALA2/Ethylene Responsive Factor (AP2/ERF) transcription factors: mediators of stress responses and developmental programs. New Phytol. 2013, 199, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.-T.; Xu, P.; Zhao, P-X.; Liu, R.; Yu, L-H.; Xiang, C-B. Arabidopsis ERF109 mediates cross-talk between jasmonic acid and auxin biosynthesis during lateral root formation. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5833. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, H.; Wang, N.; Jiang, S.; Fang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, G.; Wang, Y.; Su, M.; Xu, L.; Chen, X. The ethylene response factor MdERF1B regulates anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in apple. Plant Mol. Biol. 2018, 98, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zhao, P.-X.; Cai, X-T.; Mao, J-L.; Miao, Z-Q.; Xiang, C-B. Integration of Jasmonic Acid and Ethylene Into Auxin Signaling in Root Development. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 271.

- Zhu, X.; Wang, B.; Liu, W.; Wei, X.; Wang, X.; Du, X.; Liu, H. Genome-wide analysis of AP2/ERF gene and functional analysis of CqERF24 gene in drought stress in quinoa. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.-P.; Zhang, X-W.; Bi, S-Q.; You, C-X.; Wang, X-F.; Hao, Y-J. The ERF transcription factor MdERF38 promotes drought stress-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in apple. Plant J. 2020, 101, 573–589. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.; Goto-Yamamoto, N.; Hirochika, H. Retrotransposon-Induced Mutations in Grape Skin Color. Science 2004, 304, 982–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, N.W.; Davies, K.M.; Lewis, D.H.; Zhang, H.; Montefiori, M.; Brendolise, C.; Boase, M.R.; Ngo, H.; Jameson, P.E.; Schwinn, K.E. A Conserved Network of Transcriptional Activators and Repressors Regulates Anthocyanin Pigmentation in Eudicots. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 962–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, A.; Zhao, M.; Leavitt, J.M.; Lloyd, A.M. Regulation of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway by the TTG1/bHLH/Myb transcriptional complex in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant J. 2008, 53, 814–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).