1. Introduction

Quantum mechanics expresses transition amplitudes as complex exponentials of the classical action,

, yet the geometric origin of this phase representation has never been derived from first principles. The rule underlies every quantum formalism—from de Broglie’s matter-wave hypothesis [

9] to Feynman’s path integral formulation [

12]—but in both cases it is introduced heuristically rather than deduced. Why should physical observables depend on the

modular phase of the action rather than on its absolute value?

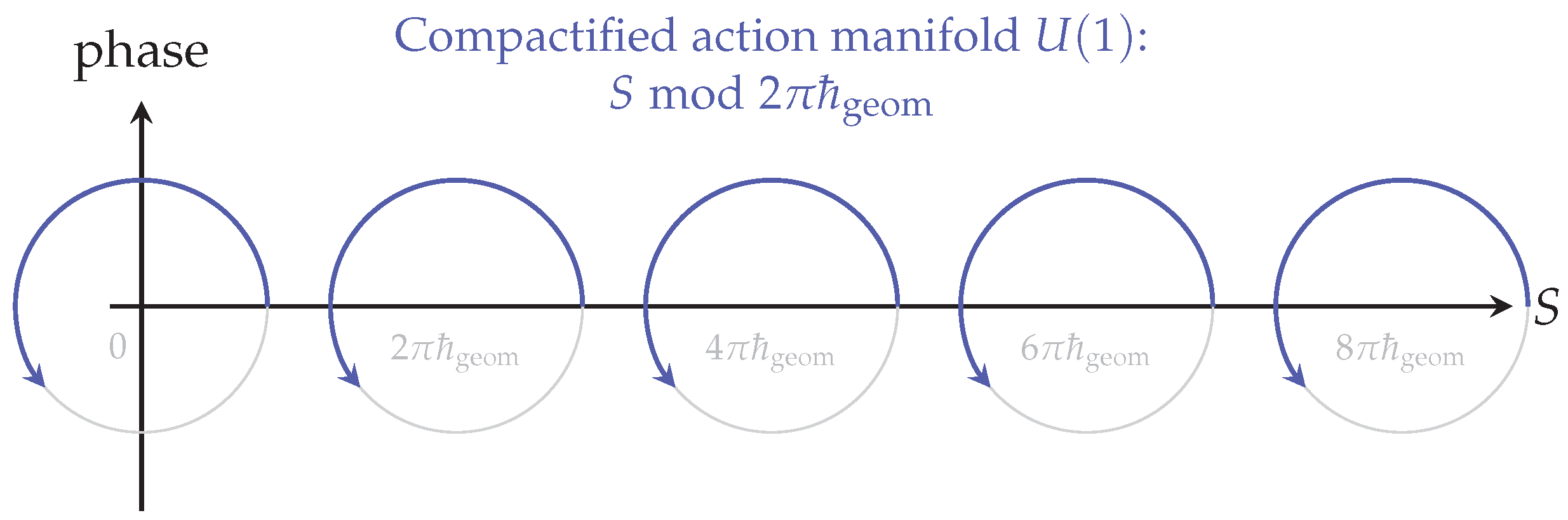

This work demonstrates that once the action possesses a finite quantum,

, its domain is no longer the real line but a topologically compact space. The classical action manifold

becomes periodic,

so that all measurable quantities depend only on the equivalence class

This compactification enforces phase periodicity and thereby

requires wave-like interference, without invoking additional postulates or any particle–wave dual ontology. The familiar amplitude

thus arises naturally as the coordinate map on a compact action manifold, echoing earlier suggestions that quantum phase may have a geometric origin [

5,

14].

We formulate this result as a theorem: any finite quantum of action implies interference with modulation period . This establishes a geometric foundation for de Broglie’s and Feynman’s rules and shows that quantum wave behavior follows inevitably from finite action.

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) provides the physical substrate for this compact geometry. In CFT, the fundamental causal field

carries quantized symplectic flux

, defining the same finite unit of action as a topological invariant of the causal manifold. Planck’s constant thereby acquires a geometric origin: it measures the minimal symplectic twist of causal space. Through this correspondence, CFT emerges as a possible reformulation of fundamental physics, linking quantum behavior, spacetime geometry, and causal structure under a single geometric principle [

20,

21].

2. Finite Quantum of Action and Compact Geometry

2.1. Modular Action

In classical mechanics, the action functional

is a continuous real quantity defined over an unbounded domain

, allowing arbitrary infinitesimal variations [

15,

19]. Nothing in the classical formalism restricts its absolute scale or imposes periodicity.

This situation changes fundamentally once the universe admits a

finite quantum of action, denoted

. This constant defines the smallest resolvable increment of dynamical phase that can be physically distinguished. Consequently, two trajectories whose actions differ by integer multiples of

are physically equivalent:

Equation (

1) replaces the open classical action line by an equivalence relation on

, compactifying it into a closed phase manifold in the same sense that angular coordinates are compactified in phase–space quantization [

4,

10]. Physical observables depend not on the absolute value of

S but on the associated phase

which provides a coordinate on the compact space

analogous to the fiber of a principal

bundle in geometric quantization [

32]. Hence, the existence of a finite quantum of action geometrically compactifies the one-dimensional action manifold into a periodic circle, introducing an intrinsic curvature that defines the cyclic structure of all dynamical evolution.

2.2. Geometric Interpretation

The compactification of action space endows it with a constant

phase curvature

analogous to the curvature of a circle of radius

. Each classical trajectory corresponds to a path winding around this compact

manifold, while quantum interference arises from the overlap of different windings projected onto physical configuration space. In this geometric view,

is not merely a numerical parameter but a fundamental curvature scale that determines the periodicity of action space and the emergence of quantum phase structure, consistent with modern approaches linking quantization to topology and holonomy [

14,

24].

3. Finite Action Implies Wave Interference

A finite quantum of action compactifies the classical action manifold into the periodic group , so distinct trajectories differ only by a modular phase. Interference therefore arises as a purely geometric consequence of finite action.

The derivation below makes no reference to quantum postulates or to the path integral rule; it follows solely from the topology of finite action space, extending classical variational mechanics [

15,

16] and connecting to modern geometric formulations of quantum phase [

2,

5].

Theorem 3.1 (Finite Quantum of Action Implies Wave Interference).

If physical observables depend only on the modular equivalence class , then distinct trajectories produce interference with modulation period :

Sketch of proof.

Compactification identifies the action manifold with

, whose continuous unitary characters are

. Symmetry under phase inversion restricts the measurable modulation to the first harmonic (

), yielding the cosine law. The full derivation and mathematical assumptions are provided in

Appendix A.

Interpretation.

Interference is thus not a distinct “wave” property of matter but a topological necessity of finite action. The familiar phase factor emerges as the coordinate map on the compact action manifold.

Figure 1.

Compactification of action space into a periodic manifold. A finite quantum of action converts the real axis of classical action into a compact circle. Each classical path becomes a winding on this manifold, and their phase overlaps produce interference.

Figure 1.

Compactification of action space into a periodic manifold. A finite quantum of action converts the real axis of classical action into a compact circle. Each classical path becomes a winding on this manifold, and their phase overlaps produce interference.

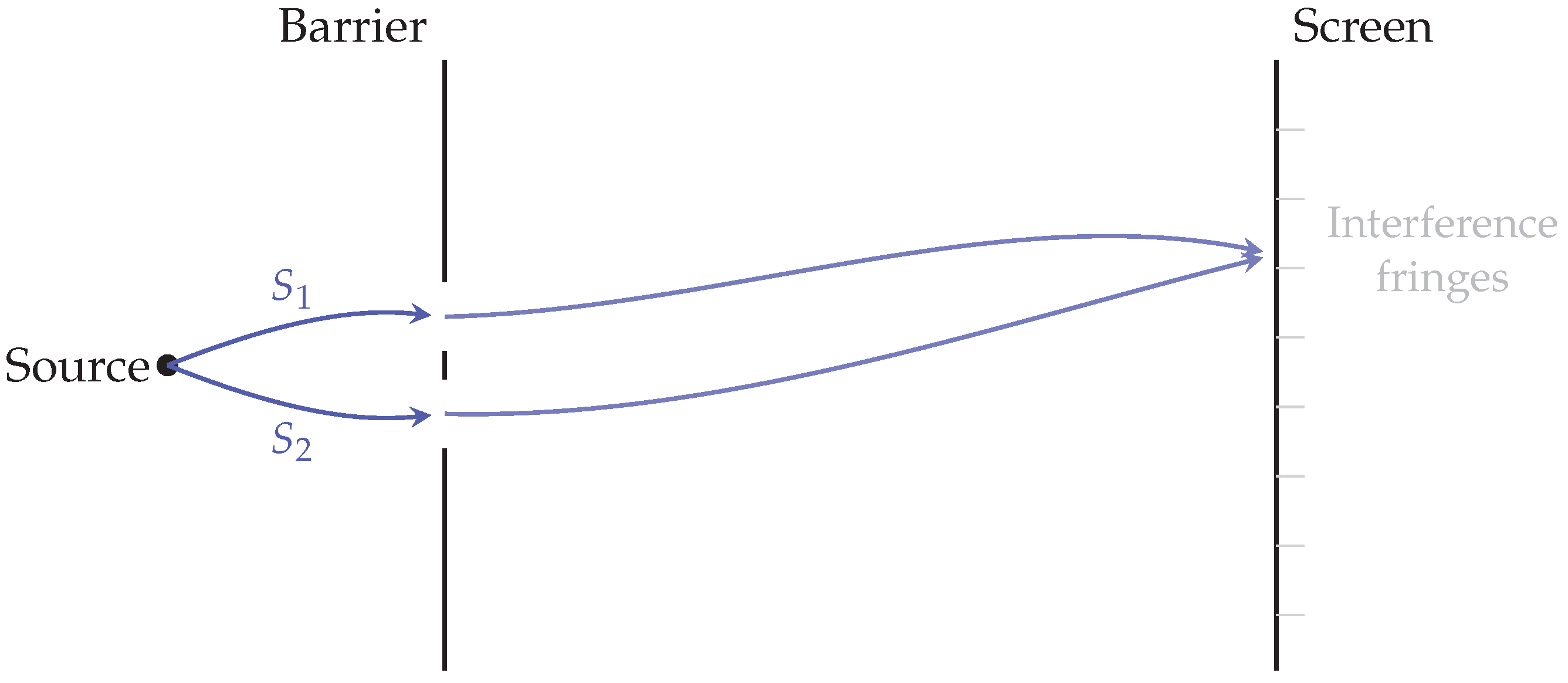

The double–slit experiment provides a canonical realization of this geometric principle. A particle traversing two admissible paths—through slits 1 and 2—has associated actions

and

. The intensity pattern at the detection plane follows directly from the phase difference on the compact

manifold:

No independent wave ontology is needed; the interference pattern arises because the modular equivalence

makes action differences observable only through their cyclic phase.

Figure 2.

Double–slit interference as modular phase geometry. Each path contributes a phase . The interference pattern emerges from the cyclic addition of these phases on the compact action manifold, without invoking an independent wave medium.

Figure 2.

Double–slit interference as modular phase geometry. Each path contributes a phase . The interference pattern emerges from the cyclic addition of these phases on the compact action manifold, without invoking an independent wave medium.

4. Chronon Field Theory and Emergent Quantization

4.1. CFT as a Foundational Framework

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) proposes that the fundamental substrate of physical reality is a continuous

causal field , whose local orientation defines the direction of temporal order. Rather than presupposing spacetime or quantization, CFT treats geometry, gravitation, and quantum discreteness as emergent collective phenomena arising from causal alignment [

20,

21]. The theory is fully covariant and background independent, unifying quantum, geometric, and gauge behavior under a single organizing principle—the

Temporal Coherence Principle (TCP):

All interactions are manifestations of the universal tendency of neighboring causal elements to synchronize their temporal phase.

Disordered chronons yield stochastic quantum fluctuations, partial coherence gives rise to interference, and perfect alignment recovers the deterministic limit of classical spacetime. Thus, CFT provides a generative mechanism for both quantum and relativistic laws rather than postulating them independently.

4.2. CFT Lagrangian and Causal Dynamics

To ensure stable finite-size solitons in

dimensions, the Chronon Field Theory (CFT) Lagrangian must include a quartic derivative (“Skyrme-type”) stabilizer that balances the quadratic alignment energy against collapse under scale transformations. This strategy follows the stability analysis of Derrick [

8] and the nonlinear sigma-model generalization introduced by Skyrme [

30]. The full Lagrangian density reads

where

J quantifies the

causal stiffness (energy cost of misalignment),

enforces the normalization

, and

provides the quartic

vorticity stiffness that stabilizes solitonic excitations. The antisymmetric tensor

measures local rotational misalignment or

causal curvature.

Variation of the action

yields the extended alignment equation

expressing the conservation of causal flux within the chronon manifold

. Regions with

correspond to perfect temporal synchrony—flat spacetime—while finite

encodes residual causal tension that manifests macroscopically as curvature and interaction fields.

The quartic term

breaks scale invariance and provides an effective internal pressure that prevents collapse of localized configurations. Derrick scaling shows that for positive

the total energy

admits a finite minimum at

ensuring the existence of stable solitons analogous to those in Skyrme and Faddeev–Hopf models [

22,

28]. At this equilibrium scale, the soliton’s integrated causal flux defines the minimum geometric action:

which establishes the quantum of action as the invariant flux carried by a stable chronon soliton of radius

. Hence, the existence of finite, non-dissipative matter domains ensures a minimal action quantum—a geometric foundation for Planck’s constant rooted in soliton stability.

Clarification on action accumulation.

It is important to note that in Chronon Field Theory the winding number

n in Equation (

5) typically equals one for stable matter solitons. Each soliton represents a single topological twist—one quantum of causal rotation—carrying the invariant flux

. Larger total actions observed in macroscopic or high–energy systems do

not correspond to higher winding numbers of individual solitons, but arise from the

collective accumulation of many unit–winding domains and their accompanying bosonic curvature modes. Bosons in CFT correspond to coherent oscillations of causal curvature on the solitonic background, each mode also transporting a discrete unit of action. Hence, macroscopic actions emerge from the cooperative dynamics of matter and field excitations, while the fundamental quantum of action remains fixed.

4.3. Emergent Gravity and Gauge Structure

At macroscopic scales, the coarse-grained limit of Equation (

3) reproduces the Einstein field equations as the hydrodynamic equilibrium of causal elasticity [

11]:

Here

and

arise from the microscopic stiffness parameters

of the causal medium. On stabilized domains, the holonomy of

generates compact gauge subgroups

,

, and

, yielding the Standard-Model hierarchy as successive levels of causal alignment, consistent with gauge–geometric unification [

20,

33]. Quantum discreteness, gauge symmetry, and gravitation thus share a common geometric origin: all emerge from compact holonomy within the causal continuum.

4.4. Origin of the Quantum of Action

The flux integral (

5) defines the smallest possible increment of causal rotation—a single “chronon twist” in the causal manifold

. This invariant establishes a universal unit of symplectic curvature, identified with Planck’s constant in the macroscopic limit:

In Chronon Field Theory, however, this quantization does not

precede matter—it

arises because matter exists. Stable solitons of the causal field, maintained by the quartic vorticity term in Equation (

2), provide finite, non-dissipative configurations that define discrete minima of the total action. Without such stable knots, all excitations would dissipate and no quantum of action could persist. Thus, quantization originates dynamically from the persistence of matter itself: the chronon field admits only integer-twisted solitons, each carrying a flux quantum

.

In this framework, quantization originates from the existence of stable matter, rather than matter arising from prior quantization. Quantization, gauge symmetry, and spacetime geometry all emerge from the same causal substrate.

4.5. Empirical Outlook

At mesoscopic coherence scales, Chronon Field Theory predicts that causal flux is not perfectly continuous but quantized in discrete units of . This discreteness should lead to small, quantized modulations in the effective phase coherence of extended quantum systems.

A particularly accessible test involves precision superconducting interferometers (e.g., SQUID rings or Josephson junction arrays), where the phase difference across the loop measures the total enclosed action flux [

7]. CFT predicts that the phase noise spectrum should display subtle, discrete steps or plateaus corresponding to integer multiples of

, rather than purely Gaussian fluctuations. Such features would represent direct evidence of causal flux quantization beyond conventional magnetic flux quantization.

Complementary tests may arise from optomechanical oscillators or gravitationally coupled interferometers, where anomalous decoherence scaling could signal partial desynchronization of causal alignment [

3,

23]. Observation of quantized variations in causal flux density would thus provide a concrete empirical signature of CFT’s central claim—that Planck’s constant originates from the geometry of causal coherence rather than from an imposed quantization rule.

5. Historical Context and Discussion

Since the inception of quantum theory, the wave character of matter has been accepted as an empirical principle rather than a derived necessity. Planck’s introduction of the quantum of action

h [

26] and Bohr’s postulate of quantized orbits [

6] established the idea that microscopic systems evolve in discrete units of action. De Broglie extended this concept to matter waves, proposing that every particle of momentum

p carries an associated wavelength

[

9]. He introduced the phase factor

by analogy with optical interference, yet the deeper reason why physical amplitudes depend on the ratio

rather than on

S itself was never explained geometrically.

Feynman later adopted the same exponential relation as the foundation of the path–integral formulation [

12,

13], treating it as a universal postulate linking classical and quantum descriptions. Although the approach reproduces all quantum results, it leaves open the origin of the phase factor itself—why nature encodes probability amplitudes through a complex phase proportional to the action.

The theorem presented here resolves this long–standing conceptual gap. Once the quantum of action is finite, the space of admissible actions becomes modular and compact. Interference, superposition, and wave–particle duality follow automatically from the cyclic topology of this compactified action space, independent of additional postulates about wave behavior or state collapse. The familiar quantum phase thus emerges as the natural coordinate map on a compact manifold of action, not as an axiomatic rule.

Chronon Field Theory provides the deeper physical substrate of this geometry. In CFT, the causal field

carries quantized symplectic flux,

establishing the same finite quantum of action as a topological invariant of the causal manifold. The universal constant

ℏ therefore originates from the discrete holonomy of causal alignment rather than from quantization as an independent assumption. Within this framework, the heuristic insights of Planck, Bohr, de Broglie, and Feynman are unified under a single geometric principle:

finite action implies cyclic phase topology.

6. Conclusions

A finite quantum of action compactifies the classical action manifold into a periodic

phase space. Continuous trajectories are thereby transformed into modular orbits, and interference emerges as a purely geometric necessity rather than as a separate physical postulate. The theorem presented here formalizes this relation: wave phenomena follow directly from the topology of finite action, eliminating the need for an independent wave ontology [

31,

32].

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) provides the physical realization of this geometry. Its causal field

carries quantized symplectic flux,

linking Planck’s constant to the minimal unit of causal rotation within the chronon manifold. In this unified picture, wave–particle duality represents the projection of a compact symplectic geometry onto emergent spacetime, while quantization arises naturally from the discrete topology of causal alignment.

These results parallel the geometric program of quantization [

17,

18] and the modern view of quantum theory as emerging from the topological structure of phase space. CFT extends this paradigm by grounding the symplectic curvature of quantum mechanics in a physically dynamical field—the chronon—whose causal coherence defines both metric spacetime and the quantum of action. Hence, the foundations of quantum mechanics appear geometric rather than axiomatic: a finite quantum of action determines the curvature of phase space, and Chronon Field Theory provides the causal substrate from which both spacetime and quantization emerge.

Appendix A. Rigorous Derivation of the Finite-Action Theorem

Appendix A.0.0.4. Assumptions.

We work on the compact abelian group

, the natural compactification of the classical action line [

14,

24]. This manifold possesses a well-defined additive group structure and admits continuous unitary characters forming its Pontryagin dual [

17,

27]. We assume:

- (A1)

Modularity. Physical phases depend only on the class .

- (A2)

Concatenation additivity. Composition of path segments adds action classes within .

- (A3)

Continuity and nontriviality. The phase map is continuous and not identically constant, ensuring a well-defined topology of phases.

- (A4)

Two-alternative symmetry. The operational interference between two alternatives depends only on their relative phase and is symmetric under

, as in all known interference experiments [

1,

29].

Lemma A.1 (Character lemma).

Under (A1)–(A3), any continuous additive phase map is a unitary character

Proof. By Pontryagin duality, the dual group of

is the integer lattice

[

17,

27]. Hence the only continuous additive homomorphisms

are of the form

, with integer winding number

k. Identifying

yields

. Nontriviality requires

; normalization of the action quantum fixes

. □

Theorem A.2.

Under (A1)–(A4), the observable modulation function

reduces, by symmetry and continuity, to

establishing the geometric origin of wave interference.

Proof. By the lemma,

are characters on

. Under assumption (A4), the visibility function must be an even class function of the relative phase

. The only continuous even function on

with a nonzero first harmonic and proper small-contrast limit is the cosine [

2,

5]. Higher harmonics correspond to

and are excluded by normalization. Thus, the intensity modulation necessarily takes the stated form. □

Remark.

Choosing

reproduces the standard quantum interference expression derived in Feynman’s path-integral formulation [

13]. However, the periodicity

arises solely from the topology of the compact action manifold

, independent of any Hilbert-space postulate or probability axiom. This establishes that interference periodicity is a purely geometric consequence of finite action.

References

- Y. Aharonov and D. Bohm, “Significance of electromagnetic potentials in the quantum theory,” Physical Review, 115, 485–491 (1959). [CrossRef]

- J. Anandan and Y. Aharonov, “Geometry of quantum evolution,” Physical Review Letters, 65, 1697–1700 (1990). [CrossRef]

- M. Aspelmeyer, T. J. M. Aspelmeyer, T. J. Kippenberg, and F. Marquardt, “Cavity optomechanics,” Reviews of Modern Physics, 86, 1391–1452 (2014). [CrossRef]

- M. F. Atiyah, Geometry of Yang–Mills Fields, Scuola Normale Superiore Pisa (1978). [CrossRef]

- M. V. Berry, “Quantal phase factors accompanying adiabatic changes,” Proceedings of the Royal Society A, 392, 45–57 (1984). [CrossRef]

- N. Bohr, “On the constitution of atoms and molecules, Part I,” Philosophical Magazine, 26, 1–25 (1913). [CrossRef]

- J. Clarke and A. I. Braginski (eds.), The SQUID Handbook, Vol. I: Fundamentals and Technology of SQUIDs and SQUID Systems, Wiley–VCH, Weinheim (2004).

- G. H. Derrick, “Comments on nonlinear wave equations as models for elementary particles,” Journal of Mathematical Physics, 5, 1252–1254 (1964). [CrossRef]

- L. de Broglie, “Recherches sur la théorie des quanta,” Ph.D. thesis, Université de Paris (1924); English translation in Annales de Physique, 3, 22–128 (1925).

- P. A. M. Dirac, “Quantised singularities in the electromagnetic field,” Proceedings of the Royal Society A, 133, 60–72 (1931). [CrossRef]

- A. Einstein, “The foundation of the general theory of relativity,” Annalen der Physik, 49, 769–822 (1916).

- R. P. Feynman, “Space–time approach to non-relativistic quantum mechanics,” Reviews of Modern Physics, 20, 367–387 (1948). [CrossRef]

- R. P. Feynman and A. R. Hibbs, Quantum Mechanics and Path Integrals, McGraw–Hill, New York (1965). [CrossRef]

- T. Frankel, The Geometry of Physics: An Introduction, 3rd ed., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2011).

- H. Goldstein, C. H. Goldstein, C. Poole, and J. Safko, Classical Mechanics, 3rd ed., Addison–Wesley, San Francisco (2002).

- W. R. Hamilton, “On a general method in dynamics,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 124, 247–308 (1834).

- A. A. Kirillov, Elements of the Theory of Representations, Springer, Berlin (1976).

- B. Kostant, “Quantization and unitary representations,” in Lectures in Modern Analysis and Applications III, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, vol. 170, Springer, Berlin (1970), pp. 87–208. [CrossRef]

- L. D. Landau and E. M. Lifshitz, Mechanics, 3rd ed., Pergamon Press, Oxford (1976).

- B. Li, “Emergent Gravity and Gauge Interactions from a Dynamical Temporal Field,” Reports in Advances of Physical Sciences, vol. 2025; 09, 2550017. [CrossRef]

- B. Li, “Emergence and Exclusivity of Lorentzian Signature and Unit-Norm Time from Random Chronon Dynamics” Reports in Advances of Physical Sciences. 2024, 8, 2550022. [CrossRef]

- N. S. Manton and P. Sutcliffe, Topological Solitons, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2004).

- W. Marshall, C. W. Marshall, C. Simon, R. Penrose, and D. Bouwmeester, “Towards quantum superpositions of a mirror,” Physical Review Letters, 91, 130401 (2003). [CrossRef]

- M. Nakahara, Geometry, Topology and Physics, 2nd ed., Institute of Physics Publishing, Bristol (2003). [CrossRef]

- S. Pancharatnam, “Generalized theory of interference and its applications,” Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences A, 44, 247–262 (1956).

- M. Planck, “On the law of distribution of energy in the normal spectrum,” Annalen der Physik, 4, 553–563 (1901).

- L. S. Pontryagin, “The theory of topological commutative groups,” Annals of Mathematics, 35, 361–388 (1934).

- R. Rajaraman, Solitons and Instantons, North–Holland, Amsterdam (1982).

- A. Shapere and F. Wilczek (eds.), Geometric Phases in Physics, World Scientific, Singapore (1989).

- T. H. R. Skyrme, “A nonlinear field theory,” Proceedings of the Royal Society A, 260, 127–138 (1961). [CrossRef]

- J.-M. Souriau, Structure of Dynamical Systems: A Symplectic View of Physics, Birkhäuser, Boston (1997).

- N. M. J. Woodhouse, Geometric Quantization, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, Oxford (1992).

- C. N. Yang and R. L. Mills, “Conservation of isotopic spin and isotopic gauge invariance,” Physical Review, 96, 191–195 (1954). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).