Submitted:

11 November 2025

Posted:

12 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Model Selection

2.2. Task Design

- Derivations (D): Symbolic reasoning and operator algebra requiring derivation of correct mathematical expressions from commutators, uncertainty relations, unitary transformations, perturbation theory, and entropy maximization

- Creative (C): Design optimization and theoretical limits testing understanding of POVM discrimination, entanglement witnesses, error correction, circuit design, and quantum advantages

- Non-standard (N): Conceptual understanding of non-standard quantum phenomena including PT-symmetric systems, quantum thermodynamics, resource theories, topological computing, and quantum metrology

- Numerical (T): Computational problems with code execution support testing eigenstate decomposition, quantum tunneling, entanglement evolution, variational methods, and open system dynamics. These tasks uniquely enable dual evaluation modes: with computational tools (testing numerical implementation capabilities) and without tools (testing physics intuition and order-of-magnitude reasoning for quantitative predictions).

2.2.1. Derivation Tasks (D1–D5)

2.2.2. Creative Tasks (C1–C5)

2.2.3. Non-Standard Concepts (N1–N5)

2.2.4. Numerical Tasks (T1–T5)

2.3. Evaluation Protocol

- Temperature = 0.0 (deterministic sampling)

- No token limits (allow complete responses)

- OpenRouter API for unified access

- Automatic verification with task-specific checkers

- Tracking: accuracy, cost, tokens, time, tool calls

- Function calling API with execute_python tool

- Code execution in subprocess with NumPy/SciPy

- Multi-turn conversation (up to 10 iterations)

- Same verification as baseline

3. Results

3.1. Overall Performance

- Overall accuracy: Models achieve 75.1% average accuracy across 900 evaluations (15 models × 20 tasks × 3 runs), with individual model performance ranging from 56.7% to 85.0%

- Top performers: Claude Sonnet 4 and Qwen3-Max tie for best performance at 85.0%, followed by Claude Sonnet 4.5 (83.3%), and DeepSeek V3, DeepSeek R1, and GPT-5 (all three at 80.0%)

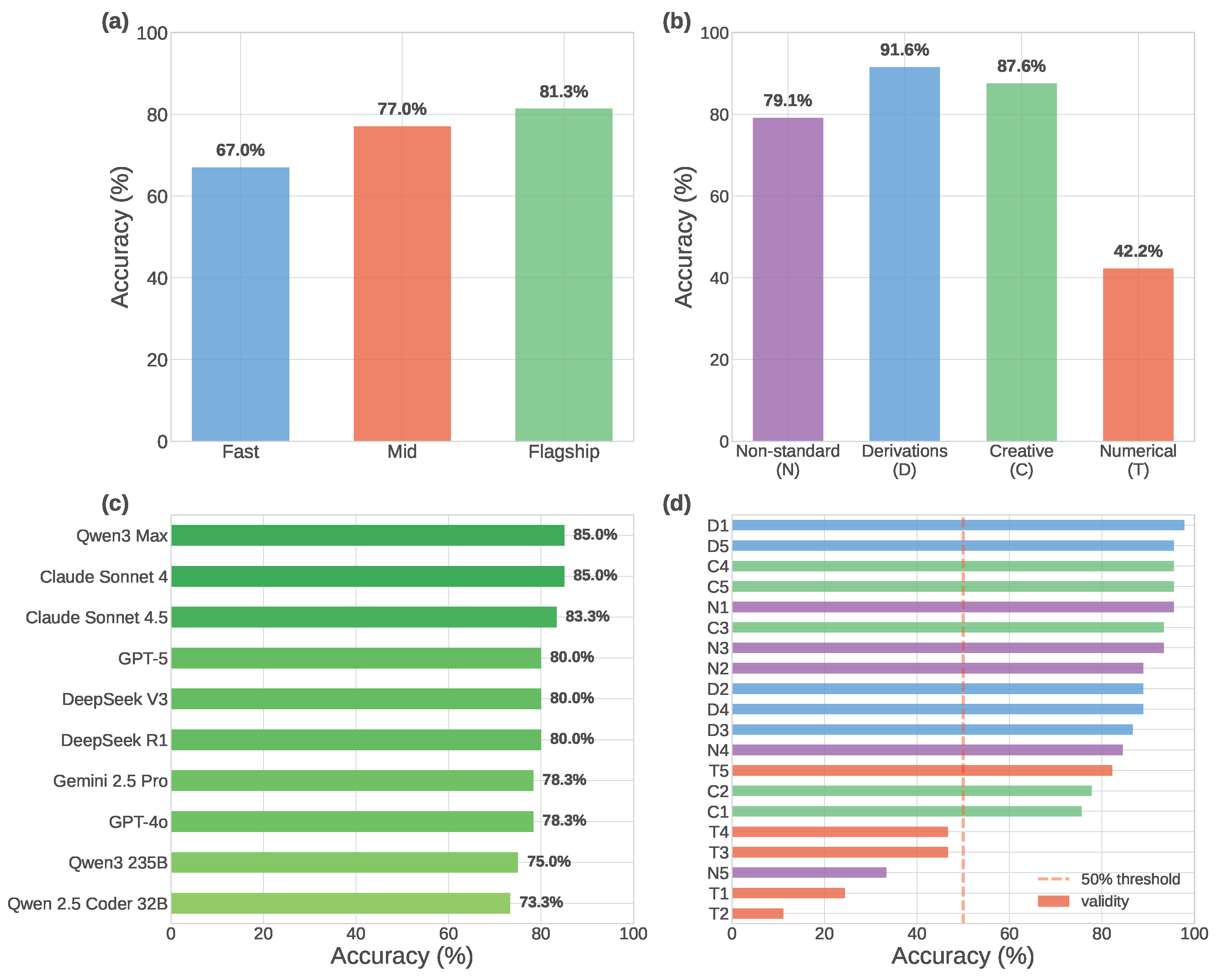

- Tier stratification: Clear performance hierarchy emerges across three capability tiers: Flagship models achieve 81.3% average accuracy, mid-tier models 77.0%, and fast models 67.0%—representing 14.3pp spread from fast to flagship

- Model selection: Evaluation includes five models per tier, stratified by providers’ pricing and marketing designations: fast tier comprises cost and speed-optimized models (Claude 3.5 Haiku, GPT-3.5 Turbo, Gemini 2.0 Flash, Qwen 2.5 Coder 32B, DeepSeek R1 Distill 32B), mid-tier balanced models (Claude Sonnet 4, GPT-4o, Gemini 2.5 Flash, Qwen3 235B, DeepSeek V3), and flagship premium models (Claude Sonnet 4.5, GPT-5, Gemini 2.5 Pro, Qwen3 Max, DeepSeek R1)

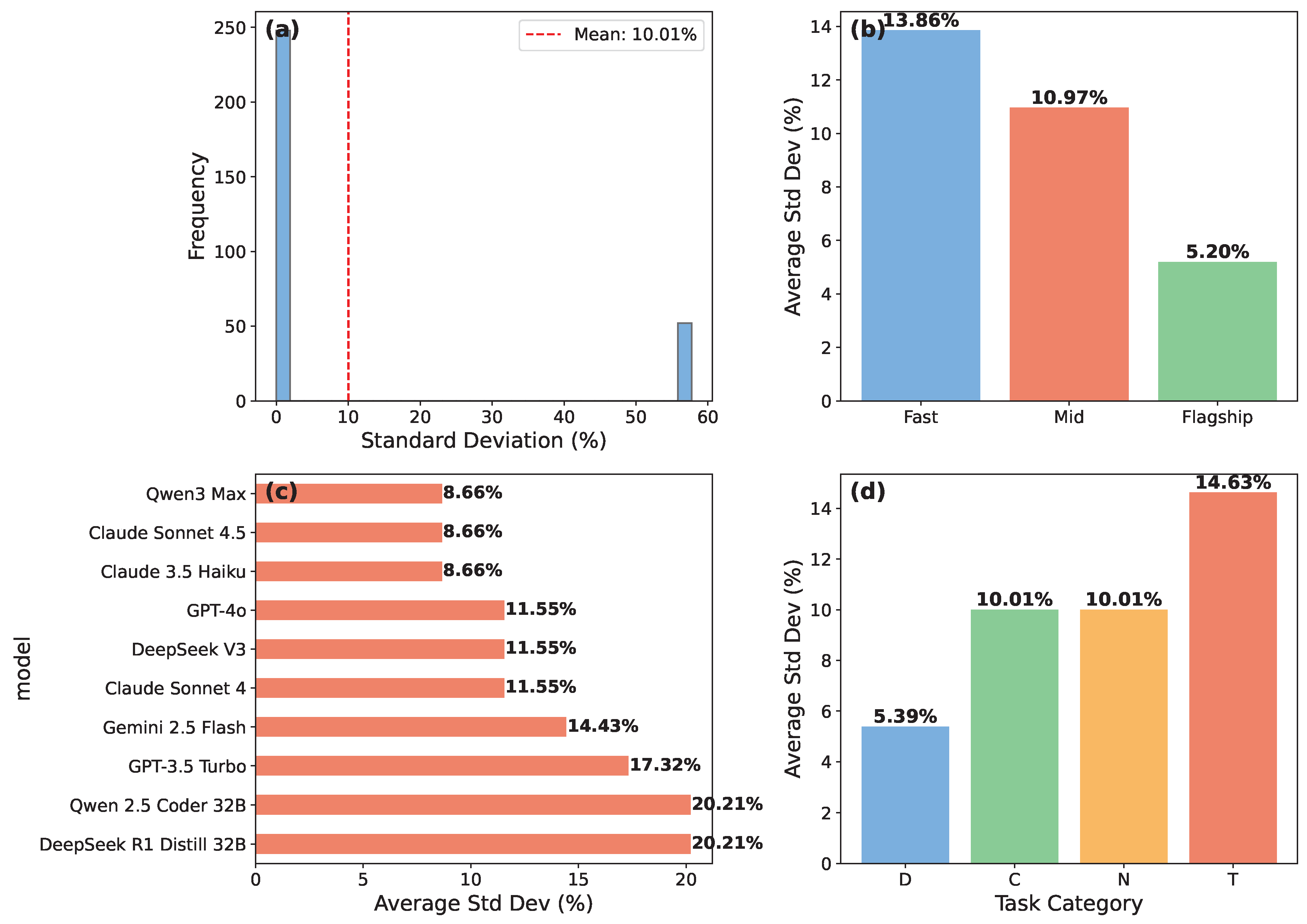

- Reproducibility: Average variance across three runs is 6.3pp, with GPT-5 exhibiting perfect consistency (80.0% ± 0.0pp) while Qwen 2.5 Coder shows highest variance (73.3% ± 16.1pp)

| Tier | Model | Accuracy | Cost/Task | Tokens/Task | Time/Task |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | ($) | (s) | |||

| Fast | Claude 3.5 Haiku | 56.7 | $0.0016 | 671 | 7.7 |

| Fast | GPT-3.5 Turbo | 63.3 | $7.62e-04 | 698 | 4.4 |

| Fast | Gemini 2.0 Flash | 71.7 | $4.79e-04 | 1,293 | 7.8 |

| Fast | Qwen 2.5 Coder 32B | 73.3 | $7.44e-04 | 5,085 | 80.1 |

| Fast | DeepSeek R1 Distill 32B | 70.0 | $0.0028 | 3,505 | 136.4 |

| Mid | Claude Sonnet 4 | 85.0 | $0.014 | 1,214 | 15.8 |

| Mid | GPT-4o | 78.3 | $0.0072 | 942 | 11.4 |

| Mid | Gemini 2.5 Flash | 66.7 | $0.020 | 8,251 | 36.4 |

| Mid | Qwen3 235B | 75.0 | $0.0022 | 4,061 | 108.3 |

| Mid | DeepSeek V3 | 80.0 | $7.73e-04 | 914 | 20.4 |

| Flagship | Claude Sonnet 4.5 | 83.3 | $0.015 | 1,247 | 17.1 |

| Flagship | GPT-5 | 80.0 | $0.031 | 3,306 | 55.7 |

| Flagship | Gemini 2.5 Pro | 78.3 | $0.130 | 13,198 | 108.0 |

| Flagship | Qwen3 Max | 85.0 | $0.019 | 3,384 | 79.8 |

| Flagship | DeepSeek R1 | 80.0 | $0.018 | 7,310 | 115.7 |

3.2. Task Category Performance

- Derivations (D): Highest overall performance at 91.6% average (fast 75.0%, mid 95.0%, flagship 100.0%), demonstrating that models excel at symbolic reasoning involving operator algebra, commutators, and quantum mechanical derivations. Flagship models achieve perfect accuracy, indicating mastery of algebraic manipulation and expression recognition

- Creative tasks (C): Strong performance at 87.6% average (fast 73.3%, mid 88.3%, flagship 90.0%), demonstrating understanding of design optimization, theoretical limits, and quantum advantages through questions about optimal parameters and maximum achievable values

- Non-standard concepts (N): Moderate accuracy at 79.1% average (fast 73.3%, mid 71.7%, flagship 86.7%), testing knowledge of advanced quantum topics from modern research. Mid-tier models surprisingly underperform fast models, while flagship models show substantial 15pp improvement over mid-tier

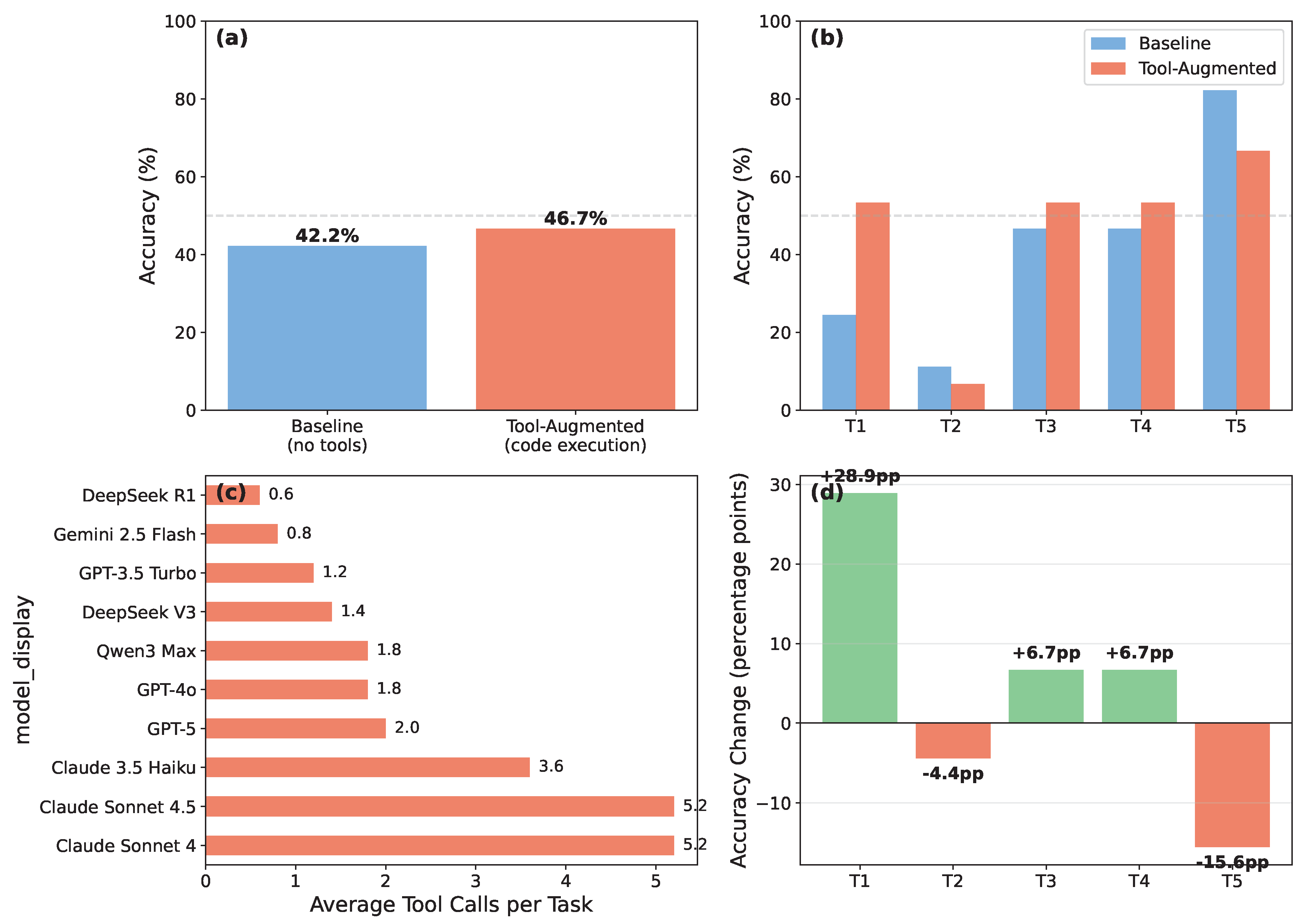

- Numerical tasks (T): Most challenging at 42.2% average (fast 41.7%, mid 45.0%, flagship 40.0%). Performance is relatively flat across tiers, with flagship models slightly underperforming mid-tier models, suggesting computational reasoning requires different capabilities than general intelligence. Tool-augmented evaluation (Section 3.5) shows mixed results, with task-dependent improvements

| Tier | Novel (N) | Derivations (D) | Creative (C) | Numerical (T) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fast | 74.7% / 2,309 | 80.0% / 1,731 | 78.7% / 1,804 | 34.7% / 3,157 |

| Mid | 74.7% / 4,522 | 96.0% / 1,293 | 89.3% / 1,857 | 48.0% / 4,632 |

| Flagship | 88.0% / 5,360 | 98.7% / 2,421 | 94.7% / 4,779 | 44.0% / 10,197 |

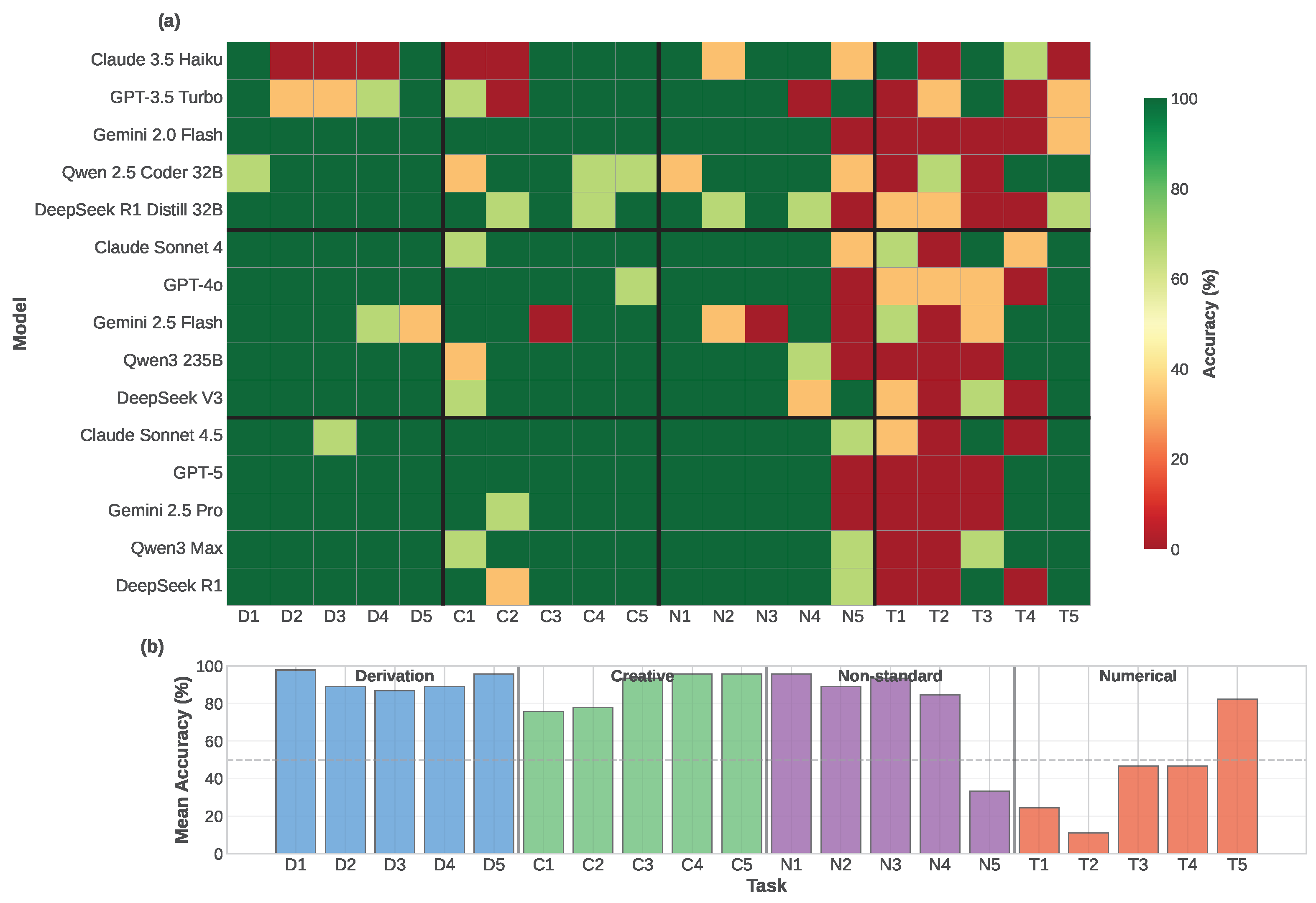

3.3. Individual Task Analysis

- D1 (Commutator Algebra): 97.8% – Symbolic derivation testing Pauli commutation relations; models successfully apply algebraic identities

- D5 (Entropy Maximization): 95.6% – Optimization problem with clear mathematical structure mapping to entropy maximization principles

- N1 (Weak Measurement): 95.6% – Advanced measurement concept, now well-represented in training data

- C4/C5 (Design Optimization): 95.6% – Questions about minimum parameters and maximum quantum advantages with clear theoretical foundations

- T2 (Quantum Tunneling): 11.1% – Time evolution requiring split-operator methods for barrier transmission; models struggle with numerical algorithm implementation and boundary conditions

- T1 (Harmonic Oscillator): 24.4% – Eigenstate decomposition of displaced wavepacket shows high variance (=43.5%), with surprising tier inversion where fast models outperform flagship

- T4 (Variational Eigensolver): =50.4%, mean 46.7% – Highest variance task; flagship models excel (60%) over fast tier (33.3%), demonstrating computational reasoning benefits

- T3 (Entanglement Concurrence): =50.4%, mean 46.7% – Two-qubit entanglement evolution shows wide performance spread (40% fast, 53.3% flagship)

- N5 (Quantum Metrology): =47.7%, mean 33.3% – Fisher information scaling challenges all tiers relatively uniformly

- C1 (POVM Design): =43.5%, mean 75.6% – Some models optimize state discrimination (flagship 93.3%), others struggle with measurement constraints (fast 60%)

- T1 (Harmonic Oscillator): =43.5%, mean 24.4% – Exhibits rare tier inversion (fast 26.7% vs flagship 6.7%)

- C2 (Entanglement Witness): =42.0%, mean 77.8% – Operator construction task with moderate difficulty but high model-specific variation

- T2 (Quantum Tunneling): Fast 26.7% vs Flagship 0.0% (+26.7pp) – Complex split-operator time evolution where all models struggle, but flagship models completely fail; simpler reasoning may avoid overcomplication

- T1 (Harmonic Oscillator): Fast 26.7% vs Flagship 6.7% (+20.0pp) – Eigenstate decomposition showing unexpected tier inversion, possibly due to overfitting in flagship training

- Task difficulty within categories varies 11–98%, making category averages incomplete descriptors

- Model consensus (low variance) tasks identify universal LLM strengths/weaknesses; high variance tasks reveal model-specific capabilities

- Tier inversions are rare (2/20 tasks, 10%) but occur on the hardest numerical tasks, suggesting that sophisticated reasoning can paradoxically hinder performance when direct computational approaches are more effective

- Flagship models demonstrate clear advantages on high-variance tasks (T4: +26.7pp, C1: +33.3pp), justifying their computational cost for challenging problems

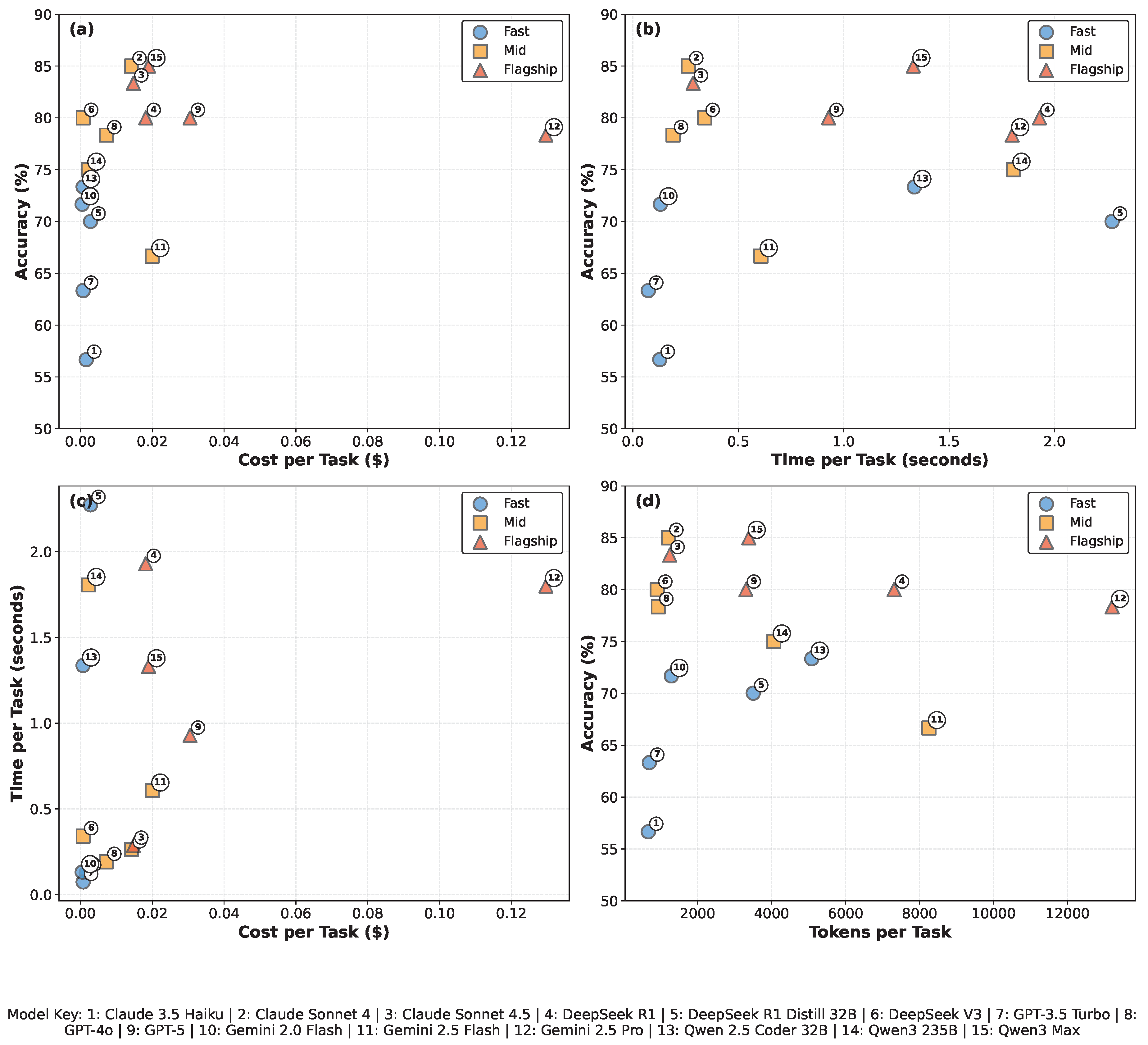

3.4. Cost-Accuracy Trade-Offs

- Fast tier: 56.7–73.3% accuracy (avg 67.0%) at $0.0005–$0.0028 per task (avg $0.0013), 4–136s per task (avg 47s), 671–5,086 tokens (avg 2,251)

- Mid tier: 66.7–85.0% accuracy (avg 77.0%) at $0.0008–$0.0200 per task (avg $0.0089), 11–108s per task (avg 39s), 915–8,251 tokens (avg 3,077)

- Flagship tier: 78.3–85.0% accuracy (avg 81.3%) at $0.0147–$0.1296 per task (avg $0.0424), 17–116s per task (avg 75s), 1,248–13,199 tokens (avg 5,690)

- Panel (a) – Cost efficiency: Flagship models cost 33× more than fast models on average (median $0.0424 vs $0.0013) for 14.3pp accuracy improvement (81.3% vs 67.0%). Within flagship tier, cost varies 9× ($0.015–$0.130) with minimal accuracy variation (78–85%), indicating substantial pricing heterogeneity within tiers.

- Panel (b) – Time efficiency: Inference time shows substantial within-tier heterogeneity reflecting model-specific architectural choices. Fast tier ranges from 4s (GPT-3.5 Turbo) to 136s (DeepSeek R1 Distill), while flagship tier spans 17s (Claude Sonnet 4.5) to 116s (DeepSeek R1). On average, flagship models require 1.6× longer than fast models (75s vs 47s), substantially less than the 33× cost multiplier. In our model selection, mid-tier achieves the fastest average inference time (39s) while delivering 77% accuracy, reflecting that model tiers are defined by pricing and capability rather than inference speed, with specific models exhibiting diverse speed-accuracy trade-offs within each tier.

- Panel (c) – Cost-time correlation: Tiers show clear separation in cost but heavily overlapping time distributions, indicating that inference time is not the primary cost driver. Cost differences stem primarily from per-token pricing rather than computational expense.

- Panel (d) – Token efficiency: Token consumption increases from fast (2,251 avg) to flagship (5,690 avg) tiers, but accuracy does not scale proportionally. Mid-tier models (Claude Sonnet 4, DeepSeek V3, GPT-4o) achieve 78–85% accuracy at 915–1,214 tokens, matching or exceeding flagship accuracy at 4–6× lower token consumption than flagship average, revealing that reasoning verbosity does not guarantee superior performance.

3.5. Tool-Augmented Evaluation

3.6. Reproducibility Analysis

4. Conclusion

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Brown, T., et al. (2020). Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33, 1877–1901.

- Cobbe, K., et al. (2021). Training verifiers to solve math word problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.14168.

- Chen, M., et al. (2021). Evaluating large language models trained on code. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.03374.

- Hendrycks, D., et al. (2021). Measuring mathematical problem solving with the MATH dataset. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.03874.

- Austin, J., et al. (2021). Program synthesis with large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.07732.

- Hendrycks, D., et al. (2021). Measuring massive multitask language understanding. International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Schick, T., et al. (2023). Toolformer: Language models can teach themselves to use tools. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.04761.

- Li, M., et al. (2024). QCircuitBench: A benchmark for quantum circuit design. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.xxxxx.

- Zhao, Y., et al. (2025). CMPhysBench: A benchmark for condensed matter physics calculations. arXiv preprint.

- Wang, Z., et al. (2024). QuantumBench: Benchmarking LLMs on quantum science. arXiv preprint arXiv:2511.00092.

- Anthropic. (2024). Introducing Claude 3.5 Haiku. Anthropic Blog.

- OpenAI. (2023). GPT-3.5 Turbo model card. Technical report.

- Google. (2024). Gemini 2.0 Flash model card. Technical report.

- Qwen Team. (2024). Qwen2.5-Coder technical report. arXiv preprint.

- DeepSeek AI. (2025). DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in LLMs via reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint.

- Anthropic. (2024). Claude Sonnet 4 model card. Technical report.

- OpenAI. (2024). Hello GPT-4o. OpenAI Blog.

- Google. (2025). Gemini 2.5 Flash model card. Technical report.

- Qwen Team. (2025). Qwen3 235B model card. Technical report.

- DeepSeek AI. (2024). DeepSeek-V3 technical report. arXiv preprint.

- Anthropic. (2024). Claude Sonnet 4.5 model card. Technical report.

- OpenAI. (2024). Introducing GPT-5. OpenAI Blog.

- Google. (2025). Gemini 2.5 Pro model card. Technical report.

- Qwen Team. (2025). Qwen3-Max model card. Technical report.

- Sakurai, J. J., & Napolitano, J. (2017). Modern Quantum Mechanics (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Griffiths, D. J., & Schroeter, D. F. (2018). Introduction to Quantum Mechanics (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Nielsen, M. A., & Chuang, I. L. (2010). Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge University Press.

- Preskill, J. (2015). Quantum information and computation. Lecture notes, California Institute of Technology.

- Bender, C. M. (2007). Making sense of non-Hermitian Hamiltonians. Reports on Progress in Physics, 70(6), 947–1018. [CrossRef]

- Lostaglio, M., Jennings, D., & Rudolph, T. (2015). Quantum coherence, time-translation symmetry, and thermodynamics. Physical Review X, 5(2), 021001. [CrossRef]

- Baumgratz, T., Cramer, M., & Plenio, M. B. (2014). Quantifying coherence. Physical Review Letters, 113(14), 140401. [CrossRef]

- Nayak, C., Simon, S. H., Stern, A., Freedman, M., & Das Sarma, S. (2008). Non-Abelian anyons and topological quantum computation. Reviews of Modern Physics, 80(3), 1083–1159. [CrossRef]

- Giovannetti, V., Lloyd, S., & Maccone, L. (2011). Advances in quantum metrology. Nature Photonics, 5(4), 222–229. [CrossRef]

- Landau, R. H., Paez, M. J., & Bordeianu, C. C. (2014). Computational Physics: Problem Solving with Python (3rd ed.). Wiley-VCH.

- Thijssen, J. M. (2007). Computational Physics (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Press, W. H., Teukolsky, S. A., Vetterling, W. T., & Flannery, B. P. (2007). Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

| Task | Description | Baseline | Tool-Aug | Acc | Avg Tokens | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | (pp) | Baseline | Tool | ||

| T1 | Harmonic Oscillator | 24.4 | 53.3 | +28.9 | 6,077 | 15,697 |

| T2 | Quantum Tunneling | 11.1 | 6.7 | -4.4 | 4,583 | 15,048 |

| T3 | Entanglement | 46.7 | 53.3 | +6.7 | 7,493 | 11,583 |

| T4 | VQE Ground State | 46.7 | 53.3 | +6.7 | 7,865 | 37,875 |

| T5 | Lindblad Steady State | 82.2 | 66.7 | -15.6 | 3,959 | 11,394 |

| Overall | All T tasks | 42.2 | 46.7 | +4.4 | 5,995 | 18,319 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).