Submitted:

17 July 2025

Posted:

18 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

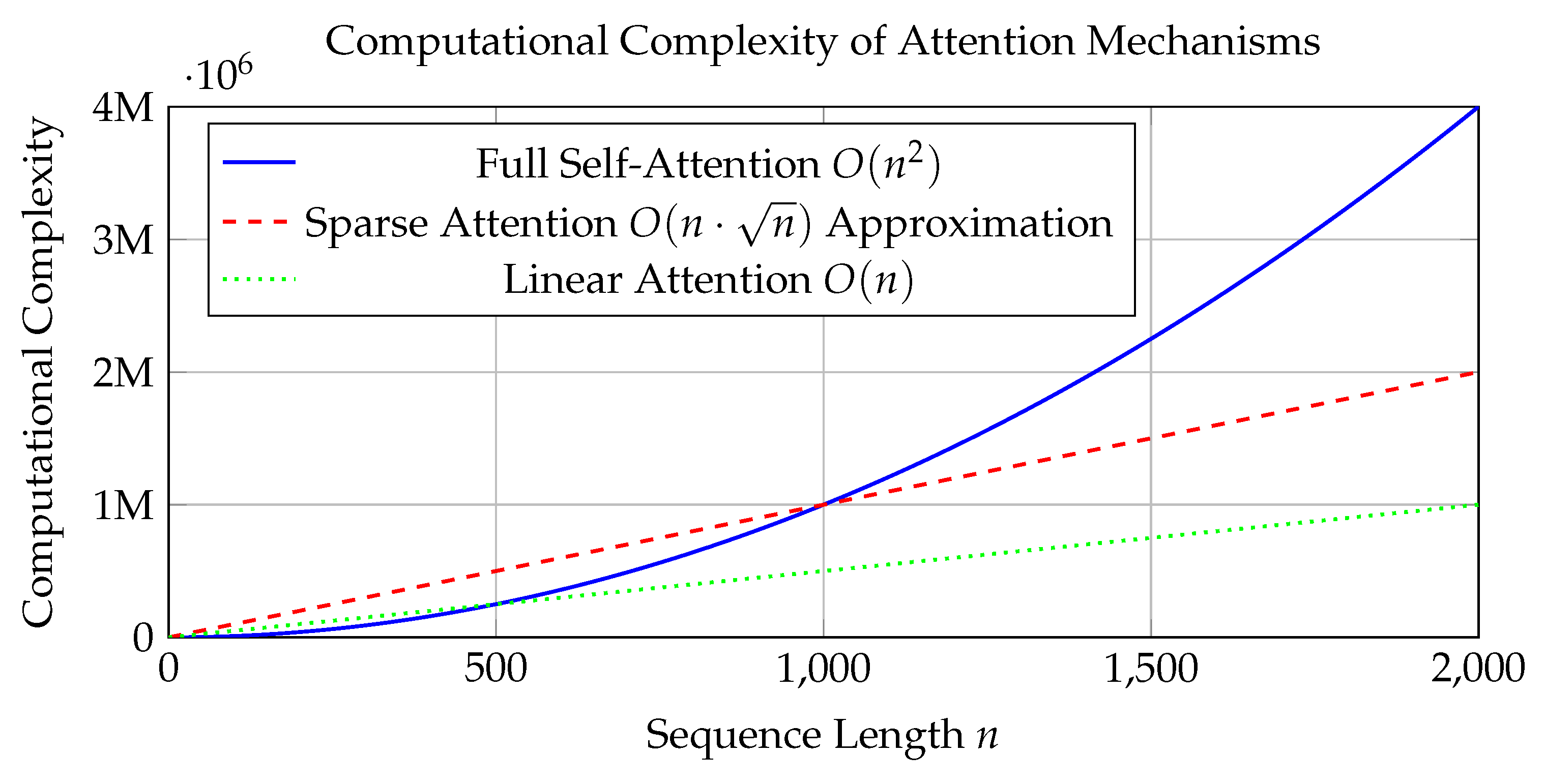

- Computational Complexity: Large-scale transformers involve quadratic complexity with respect to sequence length, making long-horizon reasoning prohibitively expensive. Efficient models seek to reduce this burden through architectural innovations or approximations.

- Memory Constraints: Reasoning tasks often require maintaining and manipulating large context windows or knowledge bases, which can exceed the memory capacity of standard LLMs. Methods to compress, retrieve, or summarize context play a critical role [6].

- Interpretability and Transparency: Unlike symbolic reasoning systems, neural reasoning models are often black boxes, limiting their explainability. Efficient reasoning models aim to improve interpretability while maintaining performance [7].

- Generalization and Compositionality: Reasoning frequently involves applying learned knowledge in novel combinations and contexts [8]. Efficient models must generalize beyond training distributions without excessive retraining or parameter increase.

- Multi-step and Hierarchical Reasoning: Complex reasoning may require sequential inference steps or hierarchical decomposition of problems. Models must balance reasoning depth with efficiency and error accumulation.

2. Background and Foundations

| Benchmark | Reasoning Type | Domain | Input Format | Evaluation Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HotpotQA [? ] | Multi-hop QA | Wikipedia Articles | Textual Questions | Exact Match, F1 |

| CommonsenseQA [? ] | Commonsense | General Knowledge | Multiple Choice | Accuracy |

| CLUTRR [? ] | Relational Reasoning | Synthetic Stories | Textual Stories | Accuracy |

| ProofWriter [? ] | Logical Deduction | Synthetic Rules | Rule Sets | Accuracy, Stepwise Correctness |

| GSM8K [? ] | Mathematical Reasoning | Math Problems | Word Problems | Accuracy |

| CodeXGLUE [? ] | Program Synthesis | Code Repositories | NL-to-Code | BLEU, Exact Match |

3. Architectural Approaches for Efficient Reasoning

4. Training Paradigms and Optimization for Efficient Reasoning

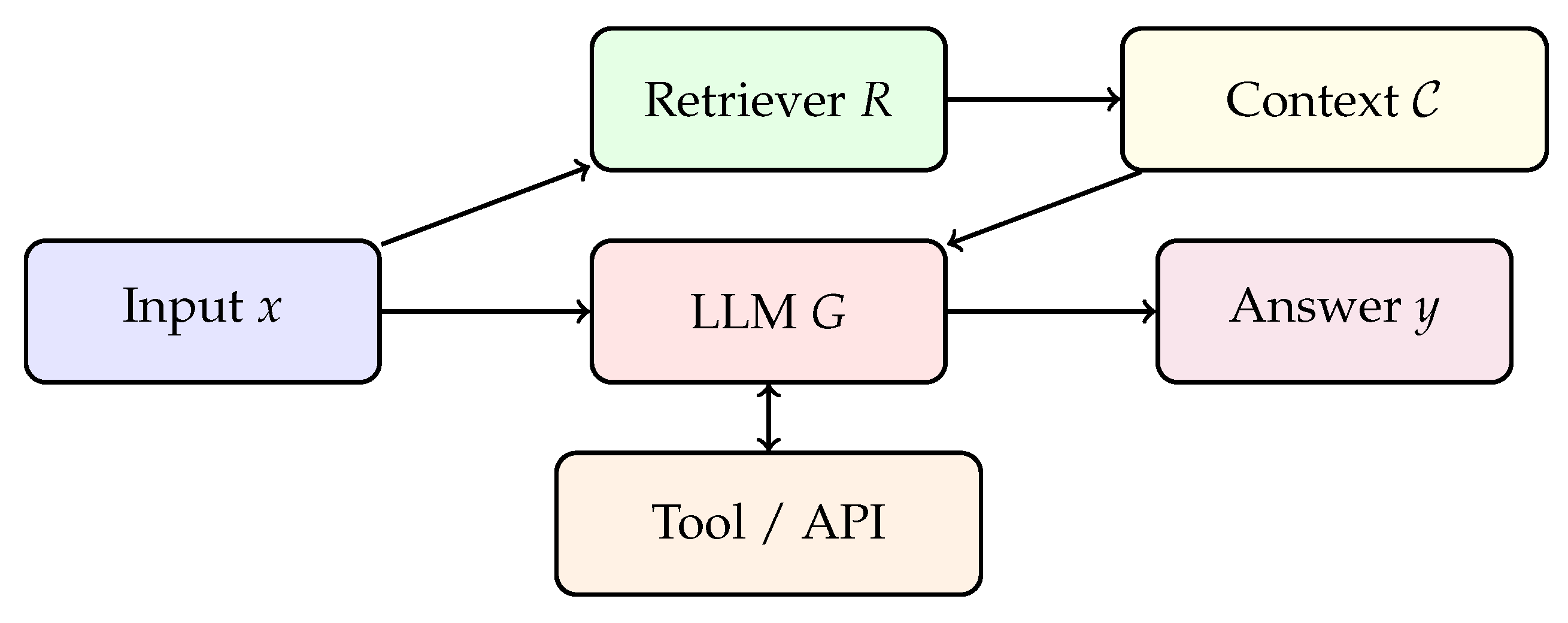

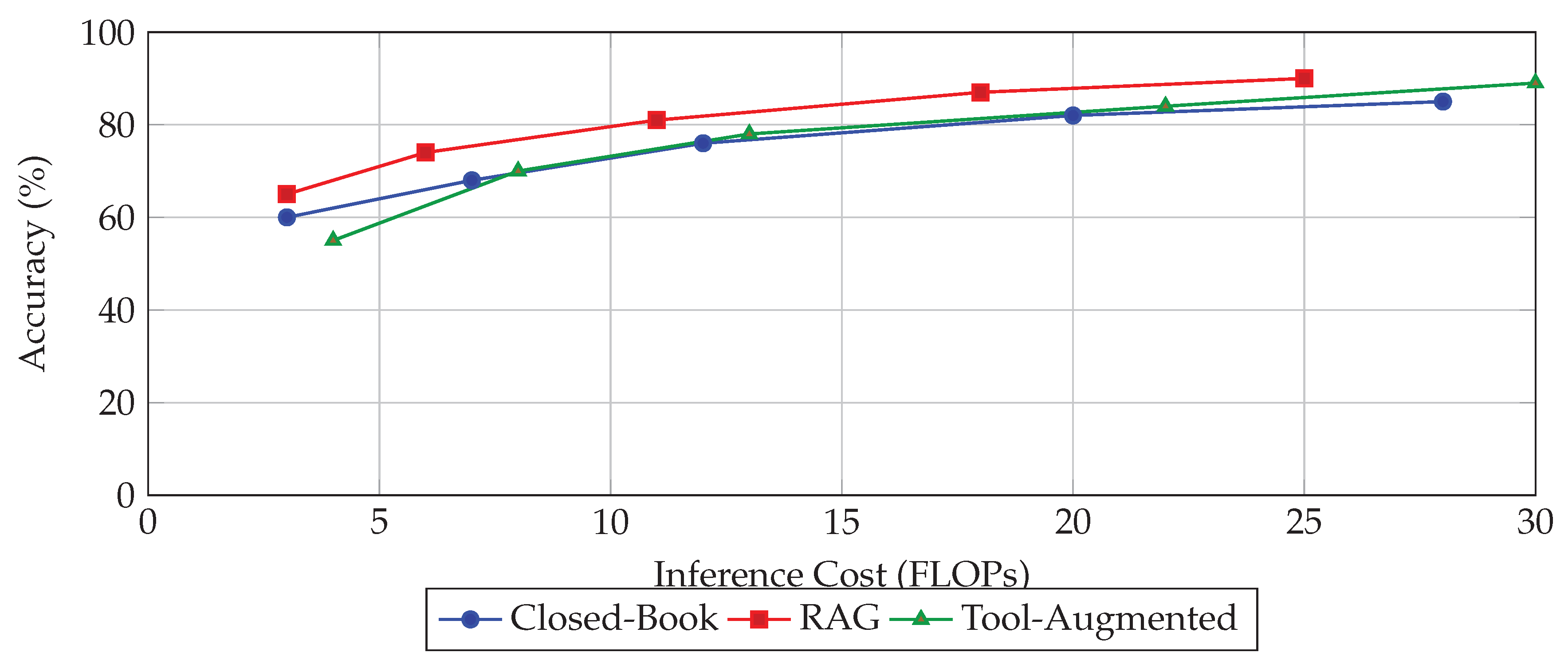

5. Retrieval-Augmented Reasoning and Tool Use

6. Benchmarks and Evaluation Protocols for Reasoning Efficiency

- Inference latency (in milliseconds or FLOPs): Time or computation required to reach the answer [74].

- Token economy: Average number of generated tokens per answer, including intermediate steps.

- Step length: Average number of reasoning hops or function calls required.

- Invocation count: Number of external tool or retrieval calls made [75].

- Error locality: Position in the reasoning chain where the first error occurs.

7. Future Directions and Open Challenges

Neuro-Symbolic Integration

Continual and Lifelong Learning for Reasoning

- Dynamically updating knowledge and procedural templates.

- Memorizing, abstracting, and generalizing from novel task distributions.

- Adapting inference strategies to user feedback or task drift.

Interpretable and Faithful Reasoning Chains

Adaptive and Budget-Aware Inference

Robustness and Adversarial Reasoning

- Semantic paraphrasing or rephrasing of inputs.

- Adversarial distractors introduced in context.

- Noisy or unreliable retrieved or tool-generated content.

Toward General-Purpose Reasoning Agents

8. Conclusion

References

- Yang, A.; Yang, B.; Zhang, B.; Hui, B.; Zheng, B.; Yu, B.; Li, C.; Liu, D.; Huang, F.; Wei, H.; et al. Qwen2. 5 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.15115 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. Learning to Reason with LLMs.urlhttps://openai.com/index/learning-to-reason-with-llms/. Accessed: 15 March 2025.

- Sakr, C.; Khailany, B. Espace: Dimensionality reduction of activations for model compression. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.05437 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, S.; Liang, K.; Liu, X. Distilling Reasoning Ability from Large Language Models with Adaptive Thinking. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.09170 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Luo, H.; Li, M.; Liu, H. Chain-of-action: Faithful and multimodal question answering through large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.17359 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Chen, T.; Chen, Q.; Mu, Y.; Shao, W.; Luo, P. Hiagent: Hierarchical working memory management for solving long-horizon agent tasks with large language model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.09559 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Jiang, W.; Shi, H.; Yu, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Kwok, J.T.; Li, Z.; Weller, A.; Liu, W. Metamath: Bootstrap your own mathematical questions for large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.12284 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Z.; Tian, M.; Luo, W. Expediting and Elevating Large Language Model Reasoning via Hidden Chain-of-Thought Decoding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.08561 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, J.; He, J.; Kong, L. Non-myopic Generation of Language Models for Reasoning and Planning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.17195 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, V. Sketches of thought; MIT press, 1995.

- Zhang, Y.; Khalifa, M.; Logeswaran, L.; Kim, J.; Lee, M.; Lee, H.; Wang, L. Small language models need strong verifiers to self-correct reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.17140 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W.; et al. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. ICLR 2022, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, R.; Yuan, Y.; Zuo, X.; Yue, Y.; Fan, T.; Liu, G.; Liu, L.; Liu, X.; et al. DAPO: An Open-Source LLM Reinforcement Learning System at Scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.14476 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Ma, S.; Lin, Y.; Wei, F. Towards thinking-optimal scaling of test-time compute for llm reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.18080 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadron, A.; Li, D.; Ma, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhuang, S.; Liu, S.; Schroeder, L.G.; Xia, T.; Mao, H.; et al. The Danger of Overthinking: Examining the Reasoning-Action Dilemma in Agentic Tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.08235 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besta, M.; Barth, J.; Schreiber, E.; Kubicek, A.; Catarino, A.; Gerstenberger, R.; Nyczyk, P.; Iff, P.; Li, Y.; Houliston, S.; et al. Reasoning Language Models: A Blueprint. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.11223 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, F.; Yu, Z.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wu, C.; Luo, Y. Atom of thoughts for markov llm test-time scaling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.12018 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Li, Y.; Chenglin, L.; Chen, H.; Yu, F.; Zhang, Y. Teaching Small Language Models Reasoning through Counterfactual Distillation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2024, pp. 5831–5842.

- Zhang, Z.; Sheng, Y.; Zhou, T.; Chen, T.; Zheng, L.; Cai, R.; Song, Z.; Tian, Y.; Ré, C.; Barrett, C.; et al. H2o: Heavy-hitter oracle for efficient generative inference of large language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 34661–34710. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, P.; Xu, J.; Weston, J.; Kulikov, I. Distilling system 2 into system 1. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.06023 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Huang, J.; Shi, S.; Zhang, W.; Yan, J.; Wang, N.; Wang, K.; Lian, S. DAST: Difficulty-Adaptive Slow-Thinking for Large Reasoning Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.04472 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muennighoff, N.; Yang, Z.; Shi, W.; Li, X.L.; Fei-Fei, L.; Hajishirzi, H.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Liang, P.; Candès, E.; Hashimoto, T. s1: Simple test-time scaling, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2501.19393]. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Xu, J.; Liang, T.; Chen, X.; He, Z.; Song, L.; Yu, D.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Thoughts Are All Over the Place: On the Underthinking of o1-Like LLMs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.18585 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Saparov, A.; He, H. Language models are greedy reasoners: A systematic formal analysis of chain-of-thought. In Proceedings of the ICLR; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Guo, Q.; Hu, X.; Jiayang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, Z. Can language models learn to skip steps? arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.01855 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.M.; Neuhoff, D.L. Quantization. IEEE transactions on information theory 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atil, B.; Chittams, A.; Fu, L.; Ture, F.; Xu, L.; Baldwin, B. LLM Stability: A detailed analysis with some surprises. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.04667 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zniyed, Y.; Nguyen, T.P.; et al. Efficient tensor decomposition-based filter pruning. Neural Networks 2024, 178, 106393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zou, A. Path-Consistency: Prefix Enhancement for Efficient Inference in LLM. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.01281 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhou, M.; Liu, W.; Liu, H.; Han, S.; Zhang, D. TwT: Thinking without Tokens by Habitual Reasoning 28 Distillation with Multi-Teachers’ Guidance, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2503.24198]. 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- LeCun, Y.; Denker, J.; Solla, S. Optimal brain damage. Advances in neural information processing systems 1989, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Yao, Z.; Wang, K.; Zhang, A.; Wang, X.; Chua, T.S. SafeMLRM: Demystifying Safety in Multi-modal Large Reasoning Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.08813 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D.; et al. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 24824–24837. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.; He, J.; Snell, C.; Griggs, T.; Min, S.; Zaharia, M. Reasoning Models Can Be Effective Without Thinking. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.09858 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Che, E.; Peng, T. How Well do LLMs Compress Their Own Chain-of-Thought? A Token Complexity Approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.01141 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valmeekam, K.; Marquez, M.; Sreedharan, S.; Kambhampati, S. On the planning abilities of large language models-a critical investigation. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.06347 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, B.; Xu, Y.; Dong, H.; Li, J.; Monz, C.; Savarese, S.; Sahoo, D.; Xiong, C. Reward-Guided Speculative Decoding for Efficient LLM Reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.19324 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, W.; Chen, G.; Su, W.; Zheng, B. Deconstructing Long Chain-of-Thought: A Structured Reasoning Optimization Framework for Long CoT Distillation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.16385 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Shen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, M.; Shao, J.; Zhuang, Y. InftyThink: Breaking the Length Limits of Long-Context Reasoning in Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.06692 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Van Durme, B. Compressed chain of thought: Efficient reasoning through dense representations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.13171 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Cohan, A.; Zhang, X.P. Z1: Efficient Test-time Scaling with Code, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2504.00810].

- Yu, Z.; Xu, T.; Jin, D.; Sankararaman, K.A.; He, Y.; Zhou, W.; Zeng, Z.; Helenowski, E.; Zhu, C.; Wang, S.; et al. Think Smarter not Harder: Adaptive Reasoning with Inference Aware Optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.17974 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, G.; Cao, S.; Wang, X. Towards Reasoning Ability of Small Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.11569 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhang, H.; Yao, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhao, H. Keep the cost down: A review on methods to optimize llm’s kv-cache consumption. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.18003 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; He, Y.; Cao, T.; Han, S.; Hooi, B. Meta-Reasoner: Dynamic Guidance for Optimized Inference-time Reasoning in Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.19918 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, D.; Zanette, A. Training Language Models to Reason Efficiently. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.04463 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, K.; Du, A.; Gao, B.; Xing, B.; Jiang, C.; Chen, C.; Li, C.; Xiao, C.; Du, C.; Liao, C.; et al. Kimi k1. 5: Scaling reinforcement learning with llms. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.12599 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrycks, D.; Burns, C.; Kadavath, S.; Arora, A.; Basart, S.; Tang, E.; Song, D.; Steinhardt, J. Measuring Mathematical Problem Solving With the MATH Dataset. In Proceedings of the Thirty-fifth Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems Datasets and Benchmarks Track; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Z.; Wang, P.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, R.; Song, J.; Bi, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; et al. Deepseekmath: Pushing the limits of mathematical reasoning in open language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.03300 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Oliaro, G.; Jia, Z.; Netravali, R. SpecReason: Fast and Accurate Inference-Time Compute via Speculative Reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.07891 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Huang, L.; Leng, J.; Liu, J.; Huang, J. Efficient test-time scaling via self-calibration. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.00031 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yue, X.; Xu, Z.; Jiang, F.; Niu, L.; Lin, B.Y.; Ramasubramanian, B.; Poovendran, R. Small Models Struggle to Learn from Strong Reasoners. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.12143 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zhu, H. Probe then retrieve and reason: Distilling probing and reasoning capabilities into smaller language models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC-COLING 2024), 2024, pp. 13026– 23 13032.

- Wang, J.; Zhu, S.; Saad-Falcon, J.; Athiwaratkun, B.; Wu, Q.; Wang, J.; Song, S.L.; Zhang, C.; Dhingra, B.; Zou, J. Think Deep, Think Fast: Investigating Efficiency of Verifier-free Inference-time-scaling Methods, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2504.14047]. [PubMed]

- Xiang, K.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Nie, Y.; Cai, K.; Yin, Y.; Huang, R.; Fan, H.; Li, H.; Huang, W.; et al. Can Atomic Step Decomposition Enhance the Self-structured Reasoning of Multimodal Large Models? arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.06252 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, J.; Li, Z.; Huang, Z.; Li, Q.; Xu, P.; Li, H.; Ho, Q. Hawkeye:Efficient Reasoning with Model Collaboration, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2504.00424].

- Song, M.; Zheng, M.; Li, Z.; Yang, W.; Luo, X.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, F. FastCuRL: Curriculum Reinforcement Learning with Progressive Context Extension for Efficient Training R1-like Reasoning Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.17287 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, P.; Welleck, S. L1: Controlling How Long A Reasoning Model Thinks With Reinforcement Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.04697 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Mitra, P.; Zhang, R. When Reasoning Meets Compression: Benchmarking Compressed Large Reasoning Models on Complex Reasoning Tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.02010 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, M.; Bai, H.; Yu, X.; Yu, T.; Yuan, C.; Hou, L. Quantization Hurts Reasoning? An Empirical Study on Quantized Reasoning Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.04823 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenglin, L.; Chen, Q.; Li, L.; Wang, C.; Tao, F.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y. Mixed Distillation Helps Smaller Language Models Reason Better. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2024, 2024, pp. 1673–1690. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, M.; Yu, Q.; Shu, D.; Zhao, H.; Hua, W.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Du, M. The impact of reasoning step length on large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.04925 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yuan, J.; Jin, H.; Zhong, S.; Xu, Z.; Braverman, V.; Chen, B.; Hu, X. Kivi: A tuning-free asymmetric 2bit quantization for kv cache. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.02750 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Choi, Y.; Shieber, S. From explicit cot to implicit cot: Learning to internalize cot step by step. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.14838 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wei, J.; Schuurmans, D.; Le, Q.V.; Chi, E.H.; Narang, S.; Chowdhery, A.; Zhou, D. Self-Consistency Improves Chain of Thought Reasoning in Language Models. In Proceedings of the The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Ma, X.; Wang, X.; Cohen, W.W. Program of thoughts prompting: Disentangling computation from reasoning for numerical reasoning tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.12588 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, J.; Cheng, W.; Yue, W.; Oyamada, M.; Wang, M.; Paternain, S.; Chen, H. DISC: Dynamic Decomposition Improves LLM Inference Scaling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.16706 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Du, T.; Jegelka, S.; Wang, Y. When More is Less: Understanding Chain-of-Thought Length in LLMs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.07266 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Yang, D.; Zhang, H.; Song, J.; Zhang, R.; Xu, R.; Zhu, Q.; Ma, S.; Wang, P.; Bi, X.; et al. Deepseek-r1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in llms via reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.12948 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wan, G.; Yu, R.; Fang, G.; Wang, X. CoT-Valve: Length-Compressible Chain-of-Thought Tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.09601 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Xia, M.; Chen, D. Simpo: Simple preference optimization with a reference-free reward. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 37, 124198–124235. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Nie, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, T. S1-Bench: A Simple Benchmark for Evaluating System 1 Thinking Capability of Large Reasoning Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.10368 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Niu, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, K.; Zhu, J.; Kang, Z. E-sparse: Boosting the large language model inference through entropy-based n: M sparsity. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.15929 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Song, L.; Tian, Y.; Yu, D.; Mi, H.; Duan, X.; Tu, Z.; Su, J.; Yu, D. Don’t Get Lost in the Trees: Streamlining LLM Reasoning by Overcoming Tree Search Exploration Pitfalls. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.11183 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Liu, H.; Fu, Z.; Song, J.; Xie, W.; Zhang, Y. Break the chain: Large language models can be shortcut reasoners. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.06580 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, I.; Almahairi, A.; Wu, V.; Chiang, W.L.; Wu, T.; Gonzalez, J.E.; Kadous, M.W.; Stoica, I. Routellm: Learning to route llms with preference data. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.18665 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Tan, S.; Wong, J.; Shi, X.; Tang, W.Y.; Roongta, M.; Cai, C.; Luo, J.; Zhang, T.; Li, L.E.; et al. Deepscaler: Surpassing o1-preview with a 1.5 b model by scaling rl. Notion Blog 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Guo, X.; Zeng, Z.; Miao, C. SoftCoT: Soft Chain-of-Thought for Efficient Reasoning with LLMs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.12134 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besta, M.; Blach, N.; Kubicek, A.; Gerstenberger, R.; Podstawski, M.; Gianinazzi, L.; Gajda, J.; Lehmann, T.; Niewiadomski, H.; Nyczyk, P.; et al. Graph of thoughts: Solving elaborate problems with large language models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2024, Vol. 38, pp. 17682–17690.

- Aytes, S.A.; Baek, J.; Hwang, S.J. Sketch-of-Thought: Efficient LLM Reasoning with Adaptive Cognitive-Inspired Sketching. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.05179 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Hao, Q.; Zong, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Lan, X.; Gong, J.; Ouyang, T.; Meng, F.; et al. Towards Large Reasoning Models: A Survey of Reinforced Reasoning with Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.09686 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Yang, M.Y.; Setlur, A.; Tunstall, L.; Beeching, E.E.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Kumar, A. Optimizing Test-Time Compute via Meta Reinforcement Fine-Tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.07572 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Yu, S.; Tan, H.L.; Zhu, H.; Tan, C. A survey of embodied ai: From simulators to research tasks. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence 2022, 6, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Yu, D.; Zhao, J.; Shafran, I.; Griffiths, T.; Cao, Y.; Narasimhan, K. Tree of thoughts: Deliberate problem solving with large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2023, 36, 11809–11822. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13971 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Wang, Y.; Shi, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, P.; Gu, J. Efficient Reasoning with Hidden Thinking. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.19201 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, C.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Q.; Wang, X.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Yang, Y.; Shen, H.T. Syzygy of Thoughts: Improving LLM CoT with the Minimal Free Resolution. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.09566 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magister, L.C.; Mallinson, J.; Adamek, J.; Malmi, E.; Severyn, A. Teaching small language models to reason. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.08410 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Yan, H.; Zhang, L.; Hu, Z.; Du, Y.; He, Y. CODI: Compressing Chain-of-Thought into Continuous Space via Self-Distillation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.21074 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.; Qian, C.; Wang, Y.; Hua, H.; Tian, K.; Zhou, Y.; Tu, Z. Openemma: Open-source multimodal model for end-to-end autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 2025, pp. 1001–1009.

- Liu, R.; Gao, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, K.; Li, X.; Qi, B.; Ouyang, W.; Zhou, B. Can 1B LLM Surpass 405B LLM? Rethinking Compute-Optimal Test-Time Scaling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.06703 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiping, J.; McLeish, S.; Jain, N.; Kirchenbauer, J.; Singh, S.; Bartoldson, B.R.; Kailkhura, B.; Bhatele, A.; Goldstein, T. Scaling up Test-Time Compute with Latent Reasoning: A Recurrent Depth Approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.05171 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfau, J.; Merrill, W.; Bowman, S.R. Let’s think dot by dot: Hidden computation in transformer language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.15758 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zniyed, Y.; Nguyen, T.P.; et al. Enhanced network compression through tensor decompositions and pruning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cuadron, A.; Li, D.; Ma, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhuang, S.; Liu, S.; Schroeder, L.G.; Xia, T.; Mao, H.; et al. The Danger of Overthinking: Examining the Reasoning-Action Dilemma in Agentic Tasks, 2025, [arXiv:cs.AI/2502.08235].

- Li, C.; Chen, Q.; Li, L.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y. Mixed distillation helps smaller language model better reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.10730 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Lin, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y. Skeleton-of-thought: Prompting llms for efficient parallel generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.15337 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Approach | Core Mechanism | Computational Complexity | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sparse Attention | Attention masking with local/global patterns | to | Long context QA, document summarization |

| Linear Attention | Kernel feature map approximations | Streaming data, real-time inference | |

| Hierarchical Models | Multi-scale chunk processing | Multi-hop reasoning, long text modeling | |

| Memory-Augmented Networks | External memory buffers with update/compress | per step, constant memory size | Sequential reasoning, dialogue systems |

| Modular Architectures | Dynamic routing among specialized modules | Depends on number of active modules | Compositional tasks, multi-domain reasoning |

| Parameter-Efficient Fine-tuning | Adapters, LoRA, prompts | Minimal parameter updates | Task adaptation, resource-constrained deployment |

| Dataset | Reasoning Type | Domain | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSM8K [? ] | Arithmetic | Elementary Math | Step-by-step numerical reasoning, free-form explanation required |

| SVAMP [? ] | Algebraic Comparison | Math Word Problems | Requires semantic understanding and algebraic manipulation |

| DROP [? ] | Discrete Reasoning | Reading Comprehension | Multi-hop reasoning with numerical and logical operations |

| HotpotQA [? ] | Multi-hop QA | Wikipedia Text | Requires synthesizing multiple facts from distinct documents |

| ProofWriter [? ] | Symbolic Logic | Synthetic | Theorem proving and proof step generation under natural language |

| ARC Challenge [? ] | General Reasoning | Science Exams | Requires abstract commonsense and factual reasoning |

| MATH [? ] | Advanced Math | Competition Math | Covers algebra, calculus, number theory, and geometry |

| BIG-Bench [? ] | Diverse Tasks | Mixed Domains | Over 200 reasoning-related subtasks with varying difficulty |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).