1. Introduction

The advent of large language models (LLMs) [1] has redefined the boundaries of machine intelligence, enabling unprecedented fluency in text generation [2] and semantic comprehension [3]. Yet beneath these remarkable advancements lies a fundamental limitation: current LLMs excel at language processing tasks [4] but struggle with systematic reasoning—the ability to methodically derive conclusions from premises, reconcile conflicting evidence, or adapt logical frameworks to novel contexts [5]. This constraint becomes particularly pronounced in information retrieval (IR), where users increasingly demand systems that do not merely retrieve documents, but also understand and reason about their content. Traditional IR systems [6], which rely on statistical word matching or even contemporary dense retrieval techniques [7], often fail to capture the nuanced intent behind queries (e.g., distinguishing between "Apple (the fruit)" and "Apple (the company)") or synthesize insights from disparate sources to address complex questions such as "How have Tesla’s inventions shaped modern power grids?" This paper makes three core contributions:

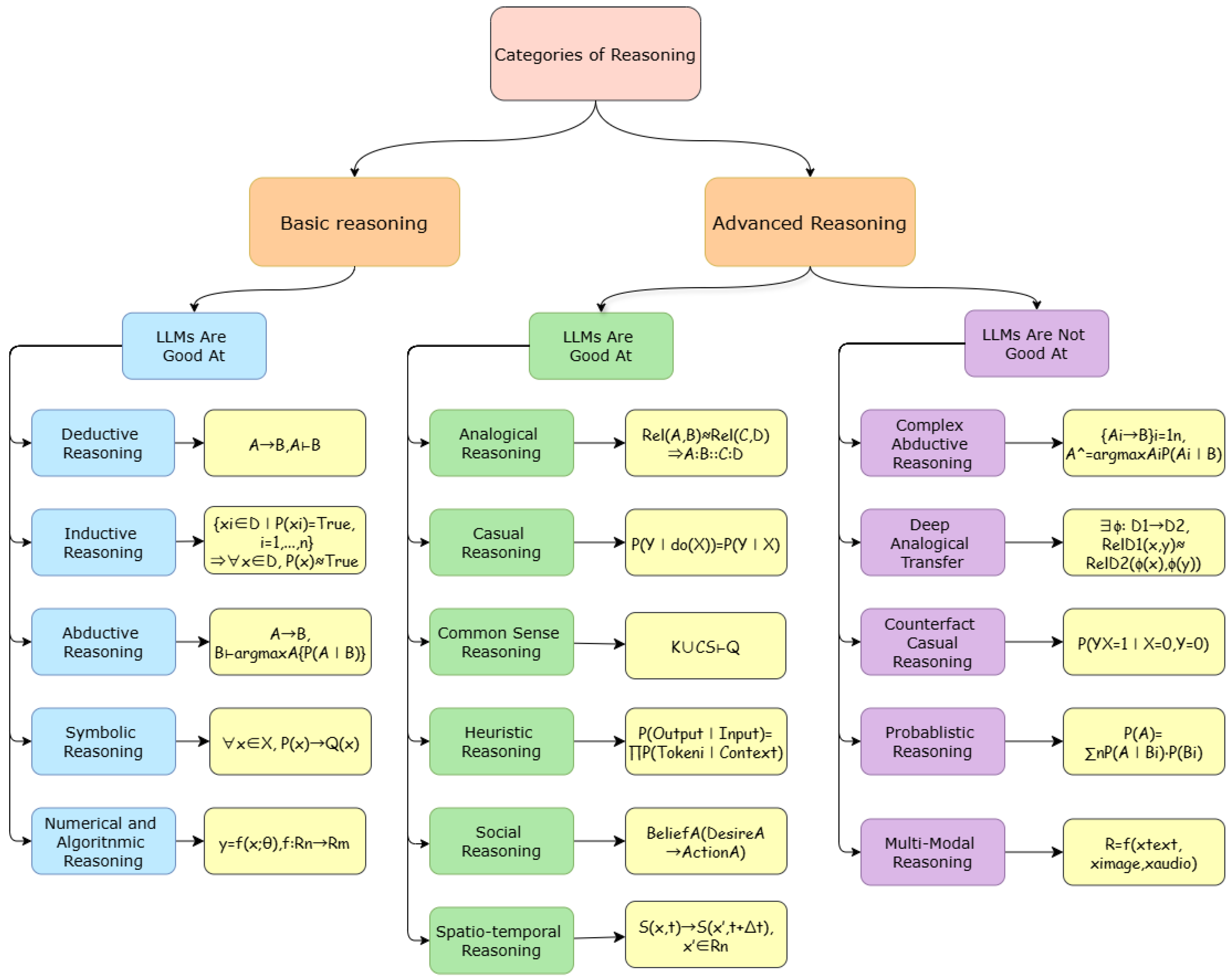

Taxonomy of Reasoning for AI: We classify reasoning techniques based on their cognitive underpinnings (

Section 2), differentiating between basic and advanced paradigms, and specifically examine their applicability to IR tasks (

Section 5).

Integration Framework: We propose a holistic integration architecture (

Section 3–4) that embeds reasoning into AI models via prompt engineering, retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), and hybrid neural-symbolic systems—with empirical validation drawn from open-domain question answering (QA) and scientific search tasks.

Challenge-Driven Roadmap: We outline a challenge-oriented roadmap (

Section 6), identifying critical gaps in the reliability of multi-step reasoning and proposing solutions that leverage modular design and dynamic knowledge graphs. Our work highlights that reasoning is not merely an auxiliary component, but a structural prerequisite for next-generation AI systems: systems that do not just deliver results, but also justify them through transparent, human-aligned logic.

Figure 1.

An Overview of Reasoning Structure.

Figure 1.

An Overview of Reasoning Structure.

2. Taxonomy of Reasoning

Reasoning methods can be systematically categorized based on their logical structure, cognitive processes, and applicability to problem-solving. This taxonomy divides reasoning into Basic and Advanced paradigms, reflecting their complexity, reliance on prior knowledge, and ability to handle uncertainty or multi-modal contexts.

2.1. Basic Reasoning

2.1.1. Deductive Reasoning

Deductive reasoning [8] involves drawing specific conclusions from general principles or premises. If the premises are true and the reasoning is valid, the conclusion must also be true. This form of reasoning moves from the general to the specific. It is widely used in mathematics, logic, and formal systems where conclusions need to be definitively proven based on established axioms or laws.

From , we can get that if A is true and it implies B, then B must also be true.

2.1.2. Inductive Reasoning

Inductive reasoning [9] involves drawing general conclusions from specific observations or instances. The conclusions reached are probable but not certain, as they extend beyond the available evidence. It is commonly employed in scientific research, data analysis, and everyday decision-making where patterns observed in samples are generalized to larger populations

From , we can get that if all sampled elements of D satisfy , then all elements in D are likely to satisfy .

2.1.3. Abductive Reasoning

Abductive reasoning [10] entails forming the most plausible explanation for observations, often with incomplete information. It involves inferring the best possible conclusion to explain a set of data. It is often utilized in diagnostic fields such as medicine and troubleshooting, where practitioners must infer the most likely cause from limited evidence.

From , we can get that if B is observed, the most probable explanation is the A that maximizes .

Figure 2.

An Overview of Reasoning Categories.

Figure 2.

An Overview of Reasoning Categories.

2.1.4. Symbolic Reasoning

Symbolic Reasoning [11] refers to a form of artificial intelligence (AI) that operates on structured representations of knowledge using formal logic, rules, and symbolic manipulation. It relies on explicit rules and logical inference to derive conclusions, making it inherently interpretable and precise.

From , we can get that for all x in the set X, if holds, then must also hold.

2.1.5. Numerical and Algoritnmic Reasoning

Numerical and Algorithmic Reasoning [12] refers to the ability to solve quantitative and structured problems through systematic computation, mathematical operations, and step-by-step algorithmic procedures. This form of reasoning is fundamental in tasks requiring precise calculations, optimization, or the application of well-defined computational methods.

From , we can get that the output y is computed from input x using a function f with parameters .

2.2. Advanced Reasoning

LLMs Are Good At:

2.2.1. Analogical Reasoning

Analogical reasoning [13] involves comparing two similar cases and inferring that what is true for one is also true for the other. It relies on identifying shared properties to draw conclusions about unknown aspects. It is common in legal reasoning, problem solving, and learning, where past cases or experiences inform understanding of new situations.

From , we can get that the relationship between A and B is analogous to that between C and D.

2.2.2. Casual Reasoning

Causal reasoning [14] involves identifying relationships between causes and effects, understanding how one event leads to another. It refers to the cognitive process of identifying and understanding the cause-and-effect relationships between events, variables, or actions. Causal reasoning seeks to determine whether one event directly influences another, often considering interventions.

From , we can get that intervention on X causes a different outcome on Y compared to just observing X, indicating a causal effect.

2.2.3. Common Sense Reasoning

Common sense reasoning [15] refers to the ability to make sound judgments based on simple perceptions of the situation or the facts. It involves practical decision-making and the ability to infer everyday situations. It is integral to artificial intelligence and robotics, with the aim of enabling machines to process information in a human-like manner.

From KUC5−Q, we can get that models must apply everyday knowledge to answer commonsense questions.

2.2.4. Heuristic Reasoning

Heuristic reasoning [16] refers to problem-solving strategies that employ practical, experience-based shortcuts or "rules of thumb" to efficiently arrive at satisfactory solutions, often at the cost of guaranteed optimality or precision. Common heuristics include availability , representativeness , and anchoring.

From , we can get that the next token is predicted based on the given context using heuristic probability.

2.2.5. Social Reasoning

Social reasoning [17] encompasses the cognitive processes required to understand, predict, and navigate interactions within social contexts, including inferring others’ mental states, recognizing norms, and interpreting intentions or emotions. It integrates implicit knowledge of cultural rules, empathy, and perspective-taking to guide behavior in collaborative or competitive settings.

From , we can get that an agent’s actions are inferred from their beliefs and desires.

2.2.6. Spatio-Temporal Reasoning

Spatio-temporal reasoning [18] refers to the cognitive and computational ability to represent, interpret, and draw inferences about entities and events in relation to their spatial configurations and temporal dynamics.

From , we can get that the state of x at time t determines its state at a future time .

LLMs Are Not Good At:

2.2.7. Complex Abductive Reasoning

Complex abductive reasoning involves generating and selecting the most plausible explanatory hypotheses from incomplete or ambiguous observations, often requiring integration of background knowledge, contextual constraints, and multi-step inference [19].

From , we can get that the best explanation for B is the one with the highest posterior probability.

2.2.8. Deep Analogical Transfer

Deep analogical reasoning refers to identifying and transferring abstract relational structures (beyond surface similarities) between dissimilar domains.

From , we can get that a relationship from domain can be mapped to a similar one in domain .

2.2.9. Counterfactual Reasoning

Counterfactual reasoning [20] (Counterfact Casual Reasoning) evaluates hypothetical scenarios by altering causal antecedents. It relies on: Structural causal models (SCMs) [21] to simulate interventions, and distinguishing actual vs. potential outcomes .

From , we can get the probability of Y occurring under intervention , even though in reality and .

2.2.10. Probablistic Reasoning

Probabilistic reasoning [22] quantifies uncertainty by assigning degrees of belief to propositions using probability theory .

From , we can get that the total probability of A is computed by summing over all possible using the law of total probability.

2.2.11. Multi-Modal Reasoning

Multimodal reasoning [18] integrates information across distinct sensory modalities (text, image, audio, etc.) to solve tasks requiring cross-modal alignment.

From , we can get that reasoning R is derived from the integration of textual, visual, and auditory inputs.

3. Problem-Solving Strategies

Recent advances in LLMs have led to sophisticated problem-solving strategies that enhance reasoning, planning, and task decomposition. These approaches can be broadly categorized into prompt engineering, task decomposition and prompt engineerings. Below, we discuss these two methods and their supporting research.

3.1. Prompt Engineering

3.1.1. Foundational Techniques

- (a)

Static Prompting:

In-Context Learning (ICL) [23]is a paradigm in which large language models (LLMs) perform tasks by leveraging demonstrations (input-output examples) provided within the prompt, without any parameter updates. ICL enables LLMs to generalize from contextual examples, mimicking human-like analogical reasoning.

Chain-of-Thought Prompting (CoT): Chain-of-Thought prompting [24] is a prompting method that encourages the model to generate intermediate reasoning steps before reaching a final answer. By showing examples with step-by-step reasoning, the model learns to decompose complex problems into manageable sub-tasks.

- (b)

Dynamic Prompting:

Auto-Prompt:AutoPrompt [25] is a method for automatically generating discrete textual prompts that elicit specific behavior from language models. Instead of relying on manually designed prompts, AutoPrompt optimizes tokens using gradient-based search to enhance performance on downstream tasks.

Demonstration Retrieval:Demonstration retrieval [26] refers to the dynamic selection of relevant input-output examples (demonstrations) from an external database based on the semantic similarity to the current input. These retrieved examples are then used to construct the prompt in few-shot settings, improving contextual relevance and task performance.

3.1.2. Structural Optimization

- (a)

-

Complexity-Based Prompt:

Complexity-based prompting [27] is a strategy that adapts the structure or depth of prompts based on the complexity of the input problem. Simpler tasks may use direct or single-step prompts, while more complex tasks may trigger multi-step reasoning or Chain-of-Thought style prompting automatically.

- (b)

-

Multi-Step Prompt:

Multi-step prompting [28] is prompting strategies that involve multiple stages of interaction or reasoning, where the model is guided to break down complex tasks into smaller sub-tasks and solve them sequentially. This helps reduce reasoning leaps and improves answer consistency.

3.1.3. Adaptive Methods

- (a)

-

Gradient-Based

Prompt Tuning:Prompt tuning [29] refers to optimizing continuous embeddings for the input prompts, allowing a model to better adapt to a specific task without altering the model’s core parameters. Instead of modifying the model’s weights, prompt tuning focuses on adjusting the learned prompt representations to guide the model effectively.

Prefix Tuning: Prefix tuning [30] involves adding a learnable prefix (trainable vector) to the input text, before the actual model input. This prefix guides the model in generating task-specific outputs, allowing it to adapt to various tasks without fine-tuning the model’s internal weights.

- (b)

-

Meta-Learning

Meta Prompting:MetaPrompting [31] refers to the process of training a meta-model that dynamically generates task-specific prompts based on the input data. Instead of relying on fixed prompts, a meta-prompting system adapts and generates optimized prompts for different tasks, enhancing the model’s performance across diverse domains.

- (c)

-

Hybrid

Retrieval-Augmented Tuning:Retrieval-augmented tuning [32] is a method that combines external knowledge retrieval with prompt optimization. The idea is to dynamically retrieve relevant knowledge from external sources, such as a database or the web, and use it to augment the prompt for the model, enabling the model to generate more accurate and contextually relevant responses for a given task.

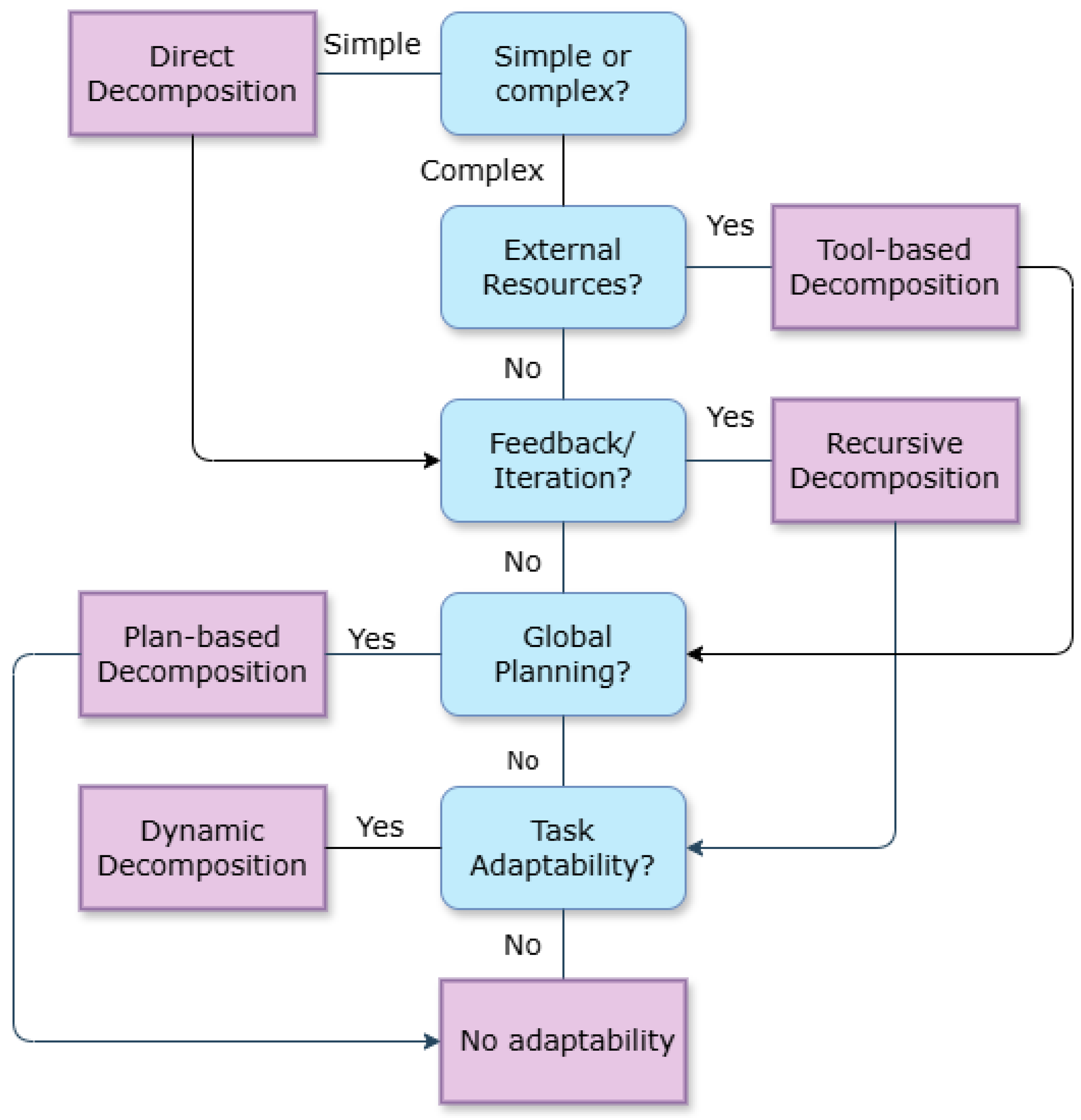

3.2. Task Decomposition

Breaking complex problems into smaller, manageable sub-tasks is crucial for improving LLM performance. According to this purpose, there are two kinds of task decomposition methods: direct decomposition and recursive decomposition. Apart from these two methods, we can also use Tool-Based Decomposition [33] (Incorporate external resources like databases, APIs, or knowledge graphs into the decomposition process), Plan-based Decomposition [34] ( Ensure that sub-tasks are aligned according to a high-level plan or goal) and other methods.

Figure 3.

The Flow Chart to Determine the Methods of Decomposition.

Figure 3.

The Flow Chart to Determine the Methods of Decomposition.

3.2.1. Direct Decomposition

Direct decomposition is a reasoning strategy that breaks down complex tasks into smaller, more manageable sub-problems, solving them sequentially or in parallel before combining their solutions. This approach is inspired by human problem-solving, where dividing a challenge into simpler steps reduces cognitive load and improves accuracy.

(a) Least-to-Most Prompting:Least-to-Most Prompting (LtM) [35] is a structured problem-solving strategy for LLMs that decomposes complex tasks into simpler sub-problems, solves them sequentially, and combines the results to derive the final answer. Inspired by educational psychology, it mirrors how humans break down challenges into manageable steps.

(b) Decomposed Prompting:Decomposed Prompting [36] is a framework for solving complex tasks by breaking them into smaller, independent sub-tasks, each handled by specialized modules (LLMs or external tools).

3.2.2. Recursive Decomposition

Recursive Decomposition is a problem-solving strategy that breaks down a complex task into smaller, self-similar sub-problems through recursive splitting, continuing until reaching trivial base cases that can be solved directly. It mirrors divide-and-conquer algorithms [37] in computer science, where each sub-problem follows the same decomposition logic as the parent problem.

(a)Self-Ask:Self-Ask [38] is a prompting strategy where the language model (LM) explicitly generates and answers its own sub-questions to solve complex, compositional problems. It narrows the compositionality gap—the performance drop when LMs fail to systematically combine known components to solve novel tasks.

(b)Plan-and-Solve Prompting:Plan-and-Solve Prompting (PS) [39] enhances zero-shot Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning by explicitly splitting the reasoning process into two phases:

-

Planning: The model generates a high-level solution strategy.

Problem: [Problem Statement] Plan: [Step 1], [Step 2], ...

-

Solving: The model executes the plan step-by-step.

Execution:

- (1)

Price per apple = $6 / 3 = $2.

- (2)

Cost for 5 apples = $2 × 5 = $10.

Final Answer: $10.

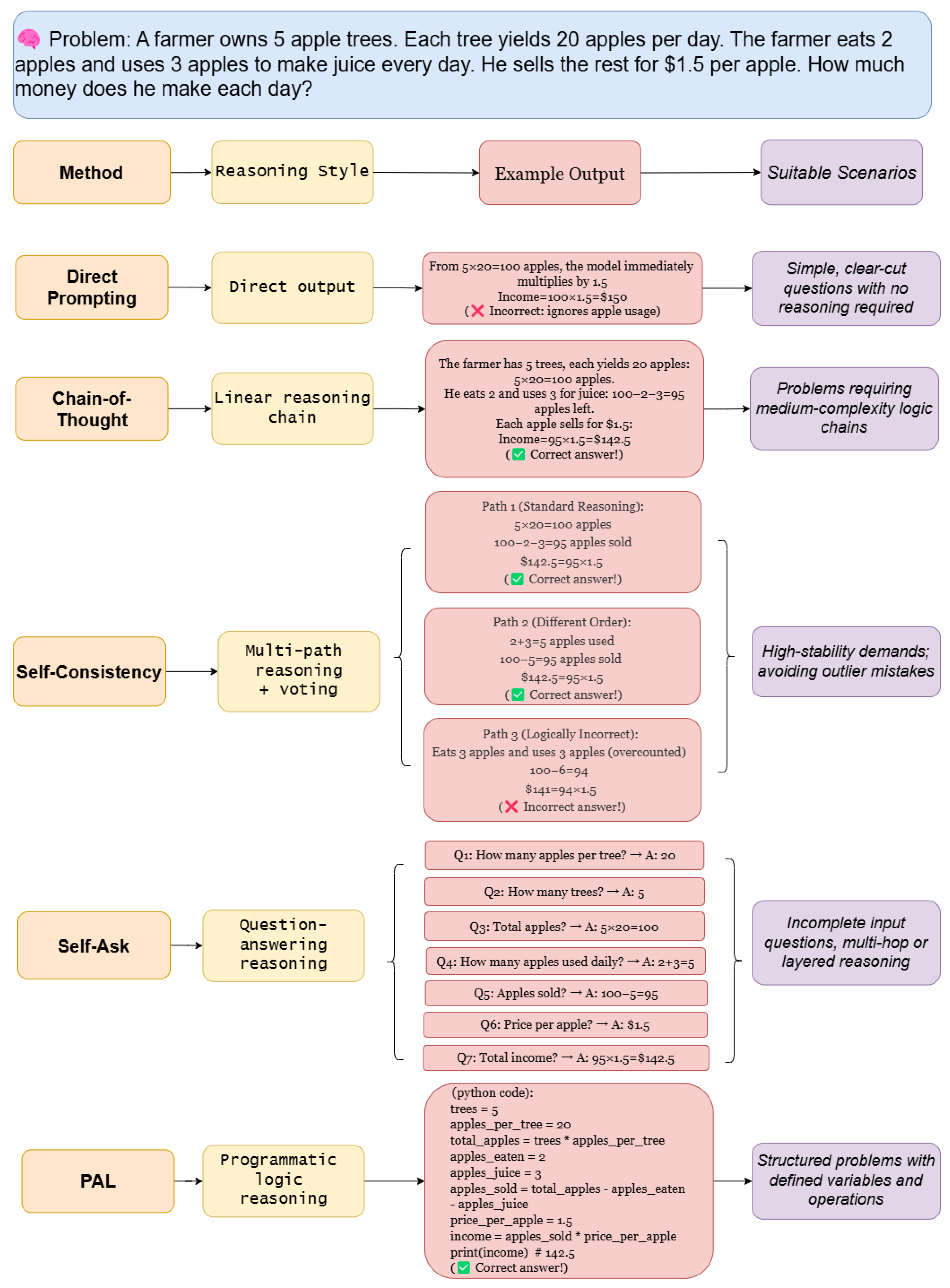

4. Reasoning Enhancement Approaches

4.1. Prompt Based Methods

There is no change of the structure of LLMs. Via enhancing prompts, they can stimulate or lead LLM to generate better reasoning results. In the

Figure 4, we want to make a comparison between five prompting methods, including direct prompting, Chain-of-Thought, Self-Consistency, Self-Ask, and Program-Aided Language Models (PAL).

4.1.1. Chain of Thought (CoT)

The introduction of CoT is in 3.1.1. In this section, we will show the comparison with other methods.

4.1.2. Self-Consistency

Self-Consistency [40] is a technique designed to enhance the reliability of reasoning in large language models (LLMs) by generating multiple independent reasoning paths for a given problem and aggregating their results to select the most consistent answer. This approach mitigates errors from individual reasoning paths by cross-validating logic and facts across multiple solutions, improving robustness in complex tasks like mathematical problem-solving, multi-hop QA [41], and fact verification. For instance, if three out of five generated paths converge on the same answer, that answer is chosen as the final output, reducing reliance on potentially flawed single-path reasoning.

4.1.3. Tree of Thought(ToT)

The Tree of Thought (ToT) [42] process is a structured approach to reasoning that involves systematically decomposing and exploring multiple paths of thought, with the goal of reaching a solution in a more organized and efficient way. There are four steps of ToT: thought decomposition, thought generator, state evaluator and search algorithm.

4.1.4. Program-Aided Language Models (PAL)

Program-Aided Language Models (PAL) [43]is a technique that combines natural language processing (NLP) with program synthesis. Its core idea is to leverage a language model (LM) to generate program code, which is then executed by an external interpreter to solve complex problems (such as mathematical calculations, logical reasoning, etc.). Unlike traditional LMs that directly output answers, PAL breaks down the problem into two steps—"generating code" and "executing code"—significantly improving accuracy, interpretability, and generalization capability.

4.2. Retrieval-Augmented Reasoning

Retrieval-Augmented Reasoning (RAR) [44] integrates dynamic knowledge retrieval with structured reasoning to enhance the problem-solving capabilities of Large Language Models (LLMs). Unlike traditional retrieval systems that focus solely on document matching, RAR treats retrieval as an active reasoning component, enabling models to access, evaluate, and synthesize external knowledge in real time.

4.2.1. Theoretic Foundations

- (a)

-

Dynamic Knowledge Expansion:

Addresses the static knowledge limitation of LLMs by retrieving up-to-date or domain-specific information.

- (b)

-

Reasoning-Retrieval Synergy:

Retrieval provides evidence for intermediate reasoning steps.

Step 1: Decompose a query into sub-questions (3.1 Task Decomposition).

Step 2: Retrieve documents for each sub-question.

Step 3: Reason over retrieved content to synthesize answers.

4.2.2. Key Techniques

- (a)

-

Hybrid Architectures:

There are several typical types of hybrid architectures: dense retrieval [7], sparse retrieval [45], sparse+dense retrieval [45], neuro-symbolic [46], multi-stage retrieval, knolwdge-enhanced retrieval and reranking-based retrieval. Table 1 is our representation of approaches with brief descriptions and limitations.

- (b)

-

Query Optimization:

In Retrieval-Augmented Reasoning (RAR), query optimization [47] plays a key role in enhancing retrieval effectiveness and reasoning efficiency. By optimizing the query, we can minimize irrelevant information, increase the relevance of retrieval results, and effectively support subsequent reasoning tasks. Below are some query optimization methods explained in detail, especially how they can be applied within the Retrieval-Augmented Reasoning framework:

Hypothetical Document Embeddings (HyDE):HyDE [48] generates ideal document representations for each query through deep reasoning. These embeddings are then used as input for the retrieval model to optimize document recall. In the Retrieval-Augmented Reasoning (RAR) framework, HyDE can significantly improve the semantic understanding of queries. The retrieval system is not just focused on matching keywords but also understands the underlying intent of the query.

Iterative Retrieval:This method refines queries across multiple stages, constantly optimizing the query based on intermediate results [49]. Each iteration fine-tunes the query based on new retrieved results, thus improving retrieval accuracy. By refining queries in each round, iterative retrieval makes the retrieval and reasoning process more efficient. As each round of feedback is incorporated, the semantic understanding of the query deepens, and the results gradually align with the target document.

Query Expansion via Large Language Models (LLMs): Query expansion [50] is achieved by Large Language Models (LLMs) generating relevant synonyms, extended terms, or contextually related keywords automatically, making the query more diverse and accurate. LLMs not only expand queries based on syntax but also generate extensions based on the query context. The use of LLMs for query expansion in the Retrieval-Augmented Reasoning (RAR) framework enhances the semantic matching ability of the retrieval system. LLMs understand the deeper semantic layers of the query and expand it with more relevant concepts and terms. This method improves the overall quality of retrieval results.

Table 1.

Hybrid Architectures in Retrieval-Augmented Reasoning.

Table 1.

Hybrid Architectures in Retrieval-Augmented Reasoning.

|

Approach |

Description |

Strengths |

Example Models |

|

Dense Retrieval |

Uses neural encoders to transform text to vectors and perform semantic search. |

Strong semantic understanding [51], supports fuzzy matching [52] |

RAG [53], REPLUG [54], Contriever [55] |

| Sparse Retrieval |

Based on term matching using inverted index structures. |

High precision and interpretability, lightweightl |

Traditional OpenQA systems [56] |

|

Sparse + Dense Retrieval |

Combines sparse methods with dense retrieval, often using rerankers for better accuracy |

Balances semantic and lexical matching, good for QA and domains like law and medicine |

ColBERT-X [57], HyDE [48], SPLADE [58], FiD-KD [59] |

| Multi-stage Retrieval |

Multi-phase approach with fast initial retrieval and refined reranking. |

Improves both efficiency and accuracy |

Dense Phrases [60], RocketQA [61] |

|

Neuro-Symbolic Retrieval |

Combines neural retrieval with symbolic rules for filtering. |

More controllable and accurate, suitable for highly regulated domains |

Self-RAG [62], LEGAL-BERT [63], SciFact [64] |

| Knowledge-Enhanced Retrieval [65] |

Incorporates external knowledge bases or structured data to support retrieval |

Improves factual consistency and entity linking |

KELM [66], ERNIE-RAG |

|

Reranking-based Retrieval [67] |

Applies powerful rerankers [68] to reorder candidates after initial retrieval. |

Boosts retrieval quality significantly |

MonoT5 [69], RankGPT, BGE-Reranker |

4.3. Architecture Modification

4.3.1. Neural-Symbolic Hybrid System

Integrates neural networks for pattern recognition with symbolic systems to enforce rigorous, interpretable reasoning. By dynamically switching between subsymbolic and symbolic processing, these architectures combine the flexibility of deep learning with the precision of formal logic.

4.3.2. Memory-Augmented Architectures

Augments LLMs with external, updatable memory modules to mitigate catastrophic forgetting and support long-term knowledge retention [70]. Unlike static LLM parameters, these memories enable dynamic read/write operations during inference.

(a) Hierarchical Memory: Short-term [71]: This memory stores recent context, such as the last N turns in a conversation or recent interactions. It allows the model to keep track of ongoing dialogues or tasks and enables context-sensitive responses. Long-term [71]: Long-term memory stores broader, domain-specific knowledge that can be retrieved as needed, supporting the model’s ability to recall past information, facts, or experiences that are not immediately present in the conversation but are essential for reasoning.

(b) Sparse Access: Sparse memory [72] addressing ensures that the most relevant pieces of memory are accessed in a computationally efficient manner. This approach is particularly useful when the model has access to large memory systems and needs to query a subset of this memory quickly.

4.3.3. Graph-Based Reasoning Modules

Explicitly models relationships between entities using graph structures to enable structured, multi-hop reasoning. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) propagate information along edges, uncovering implicit connections opaque to pure text-based models. For example, in Plan-on-Graph [73], large language models (LLMs) are used in conjunction with a knowledge graph to adaptively plan and adjust tasks, ensuring that reasoning remains accurate and grounded in real-world knowledge.

(a) Dynamic Graph Construction:Dynamic graph construction [74] refers to the real-time creation of graphs from raw data, allowing for flexible and adaptive reasoning. For example, in the domain of healthcare, a model could dynamically build a patient health graph from Electronic Health Record (EHR) notes. This graph might link patients to diagnoses, treatments, medications, and outcomes, and can be updated in real-time as new information becomes available.

(b) Neural-Symbolic Graphs: In some scenarios, symbolic rules can be incorporated into graph-based reasoning to enforce more structured and interpretable logic. For instance, a Neural-Symbolic Graph combines GNNs with symbolic reasoning rules to enforce relationships such as: "If X inhibits Y, and Y causes Z, then X may indirectly affect Z."

4.3.4. Training Paradigm Innovations

Redefines LLM training to explicitly prioritize reasoning skills, moving beyond next-token prediction to cultivate step-by-step logical capabilities.

(a) Reasoning-Aware Pretraining:Incorporate logic-heavy tasks into the pretraining phase. These tasks might include:

Program synthesis, where the model learns to generate programs based on high-level specifications.

Theorem proving, where the model is trained to prove or disprove mathematical theorems step-by-step.

(b)Staged Fine-Tuning: Supervised: Learns basic reasoning decomposition (aligned with 3.1 Task Decomposition). Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) [75]: This stage focuses on optimizing for human-preferred reasoning traits, such as conciseness, correctness, and clarity. The model is iteratively fine-tuned based on human feedback, ensuring that its reasoning aligns with human expectations and decision-making processes.

5. Models of IR Using Reasoning

5.1. Classification of Models

5.1.1. Retrieval-Phase Reasoning

Query Expansion/Rewriting: Enhances initial search queries by generating hypothetical document embeddings or reformulating ambiguous user inputs into precise search terms.

Dynamic Context Integration: Adapts retrieval strategies based on real-time reasoning about query intent.

5.1.2. In-Retrieval Reasoning

Adaptive Ranking: Dynamically reorders results using intermediate reasoning. Content-Aware Filtering: Applies logical constraints during retrieval.

5.1.3. Post-Retrieval Reasoning

Evidence Synthesis: Combines retrieved documents via generative reasoning. For example, RAG-Fusion’s weighted answer aggregation [76]). Consistency Verification: Cross-checks generated answers against retrieved facts to reduce hallucinations.

5.2. The Evolution of IR Models Using Reasoning

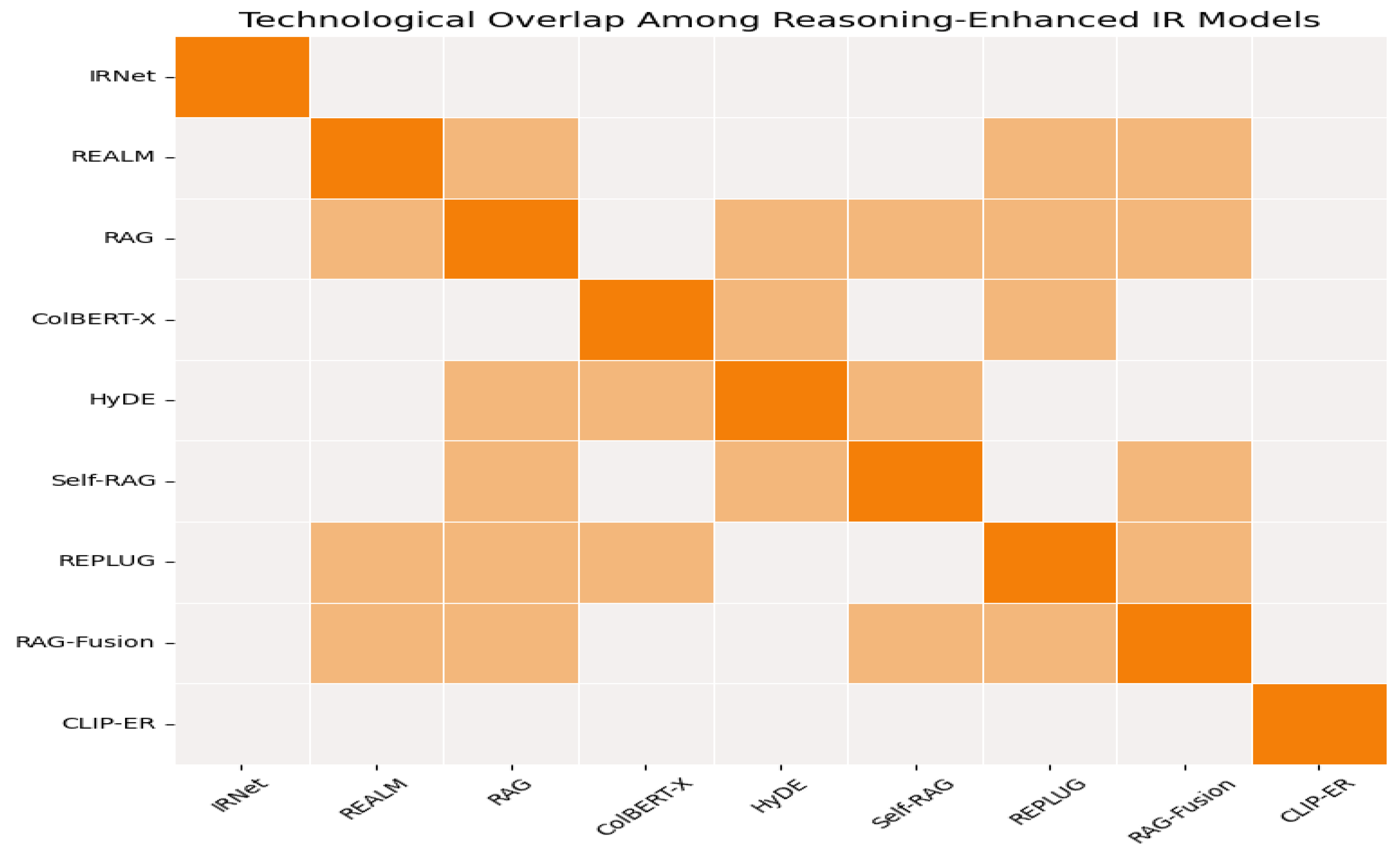

According to the Table 2, it can be found there are some overlaps between several models. For example, REALM, RAG, HyDE and REPLUG all use dense retrieval technologies, which is a big overlap in techniques for these models. Figure 6 is our overlap figure to show the similarities between these models.

Table 2.

Comparison of Reasoning-Oriented Information Retrieval-Augmented Models (2018–2024).

Table 2.

Comparison of Reasoning-Oriented Information Retrieval-Augmented Models (2018–2024).

|

Year |

Model |

Reasoning Techniques |

IR Technology |

Innovation |

Limitation |

|

2018 |

IRNet [77] |

Symbolic Reasoning |

Neural Semantic Parsing |

NL → SQL query for structured DB |

Schema rigidity; ambiguity-prone |

| 2019 |

REALM [78] |

Latent Reasoning via masked token prediction |

Dense Retrieval (BERT-based) |

Retriever-reader joint training |

Needs large pretraining; static knowledge |

|

2020 |

RAG [53] |

Multi-hop + Generative Reasoning |

Dense Retrieval + Seq2Seq |

Retrieval + generation fusion |

May hallucinate from noisy docs |

| 2021 |

ColBERT-X [57] |

Iterative Query Refinement Reasoning |

Sparse-Dense Hybrid Retrieval |

Intermediate query-level reasoning |

Costly in conversations |

|

2022 |

HyDE [48] |

Abductive Reasoning |

Embedding-Based Dense Retrieval |

Generates ideal retrieval queries |

Prompt-sensitive; sometimes unrealistic |

| 2022 |

Self-RAG [62] |

Self-Verifying (LLM feedback reasoning) |

Adaptive Retrieval + Reranking |

Adds confidence via self-critique |

Higher latency |

|

2023 |

REPLUG [54] |

Multi-path Reasoning + Voting |

Dense Retrieval Ensemble |

Aggregates via voting across retrieved paths |

Memory-heavy; requires ensemble tuning |

| 2023 |

RAG-Fusion [76] |

Probabilistic Reasoning over query variants |

Query Rewriting + Reranking |

Blends and re-ranks multiple rewritten queries |

May over-retrieve and rerank irrelevant ones |

|

2024 |

CLIP-ER |

Multimodal Analogical Reasoning |

Cross-Modal (Text + Image) Retrieval |

Visual-textual joint alignment for analogical reasoning |

Needs aligned multimodal data |

Figure 5.

Technological Overlap Among Reasoning-Enhanced IR Models.

Figure 5.

Technological Overlap Among Reasoning-Enhanced IR Models.

5.3. Applications

Table 3 shows a brief collection of applications of IR models using reasoning methods, and we also give an example of the applications.

Table 3.

Summary of Applications of IR Models Using Reasoning Methods.

Table 3.

Summary of Applications of IR Models Using Reasoning Methods.

|

Application |

Characteristics |

Examples |

|

Open-Domain QA |

|

REPLUG [54]; retrieving Tesla’s patents, power grid evolution docs, technological transfer |

|

Scientific Literature Search |

|

SciBERT [79]; biomedical terminology, causal pathways, methodology validation |

|

Multimodal Retrieval |

Cross-modal alignment Unified reasoning Context-aware learning |

CLIP-ER [80]; quantum physics concepts, text-visual alignment, diagram quality |

6. Challenges & Future Directions

According to numerous research findings and the preview of the development of reasoning methods, there are three kinds of reasoning related work, that we should put more emphases on multi-step reasoning, consistency&reliability and domain-specific adaptation.

6.1. Multi-Step Reasoning

6.1.1. Challenge

Despite advances in language modeling, LLMs still struggle with complex, multi-step reasoning tasks [27], such as those involving long-term dependencies or tasks that require a sequence of logical steps. In traditional models, reasoning is often limited to surface-level or shallow inferences, where the model may understand simple patterns but fail at deeper reasoning tasks. This is particularly true in tasks requiring multiple steps of reasoning or those that involve integrating information from diverse contexts or sources.

6.1.2. Future Directions

- (a)

Enhancing Reasoning Through Modular Systems:

One promising future direction involves breaking reasoning tasks down into smaller, more manageable components and developing modular reasoning systems [81] that allow LLMs to handle multi-step reasoning more effectively.

- (b)

Integration of External Tools:

Future work could explore integrating external tools, such as symbolic reasoning engines or dedicated problem-solving algorithms, to guide LLMs through complex task.

6.2. Consistency & Reliability

6.2.1. Challenge

LLMs, especially in zero-shot or few-shot settings, can exhibit inconsistent reasoning patterns. The output from a model may vary significantly depending on the phrasing of the prompt or the input context, leading to unreliable results. This inconsistency becomes more problematic in critical applications such as healthcare, law, and finance, where reliable and consistent reasoning is crucial for decision making.

6.2.2. Future Directions

- (a)

Enhanced Training Data and Techniques:

One possible research direction is to focus on improving training datasets to include more consistent examples and more robust reasoning processes. This could involve creating specialized datasets for reasoning that emphasize consistency and reliability.

- (b)

Consistency-Aware Models:

Another avenue is to develop models that can evaluate their own outputs for consistency, potentially incorporating self-monitoring and self-correction mechanisms into their reasoning process.

6.3. Domain-Specific Adaptation

6.3.1. Challenge

A persistent challenge in the domain-specific adaptation of Large Language Models (LLMs) lies in their limited ability to effectively integrate external knowledge into coherent reasoning processes [82]. Although retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) and similar methods introduce mechanisms for accessing relevant external documents, the reasoning integration phase remains underdeveloped.

Specifically, LLMs often struggle to accurately select, align, and synthesize information from heterogeneous sources. This is particularly problematic in specialized domains, where high precision and contextual awareness are critical.

6.3.2. Future Directions

- (a)

Improved Retrieval-Integration Mechanisms:

Future research could explore developing more sophisticated retrieval strategies that can better filter irrelevant knowledge, improving the integration process. One promising direction is using multi-step reasoning to refine the relevance of retrieved knowledge during the reasoning process.

- (b)

End-to-End Systems:

End-to-end systems refer to systems where the process of knowledge retrieval, integration, and reasoning is handled in a unified and continuous flow, rather than as distinct steps.

Conclusion

Reasoning stands at the heart of intelligent behavior, and as this study reveals, it remains one of the most significant challenges and opportunities in the continued evolution of Large Language Models (LLMs). While LLMs have demonstrated impressive capabilities in language understanding and generation, their limitations in structured, multi-step, and context-aware reasoning highlight a critical bottleneck in advancing toward more reliable and general-purpose AI.

In surveying and analyzing the landscape of reasoning techniques—ranging from prompt engineering and task decomposition to retrieval-augmented reasoning and neural-symbolic architectures—we observed that effective reasoning is not a monolithic ability but a layered, often modular process. Particularly within Information Retrieval (IR), reasoning plays an increasingly vital role in bridging the gap between surface-level pattern matching and deeper semantic understanding. Our exploration of reasoning-enhanced IR models underscores how integrating reasoning mechanisms into the retrieval and answer generation pipelines can yield measurable improvements in both performance and interpretability.

Throughout the process of collection and synthesis, we found that many IR systems implicitly rely on reasoning—even if not explicitly labeled as such—and that a growing number of models are now being designed with reasoning capabilities as a core component rather than an auxiliary function. This shift reflects a broader recognition that the future of IR and NLP more generally depends not just on accessing knowledge, but on processing it intelligently.

Looking ahead, we believe that advancing reasoning in LLMs will require a combination of principled architectural innovation, better training data with explicit reasoning traces, and a deeper understanding of how different types of reasoning interact with specific downstream tasks. As the community moves forward, we encourage further interdisciplinary collaboration between the fields of IR, NLP, logic, and cognitive science to push the boundaries of what it means for AI to think and reason.

Funding

This work is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under Grant [No.62177007].

References

- Naveed, H.; Khan, A.U.; Qiu, S.; Saqib, M.; Anwar, S.; Usman, M.; Akhtar, N.; Barnes, N.; Mian, A. A comprehensive overview of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.06435, arXiv:2307.06435 2023.

- Li, J.; Tang, T.; Zhao, W.X.; Nie, J.Y.; Wen, J.R. Pre-trained language models for text generation: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys 2024, 56, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ladhak, F.; Durmus, E.; Liang, P.; McKeown, K.; Hashimoto, T.B. Benchmarking large language models for news summarization. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2024, 12, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, K.; Tu, T.; Gottweis, J.; Sayres, R.; Wulczyn, E.; Amin, M.; Hou, L.; Clark, K.; Pfohl, S.R.; Cole-Lewis, H.; et al. Toward expert-level medical question answering with large language models. Nature Medicine.

- Kaddour, J.; Harris, J.; Mozes, M.; Bradley, H.; Raileanu, R.; McHardy, R. Challenges and applications of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.10169, arXiv:2307.10169 2023.

- Singhal, A.; et al. Modern information retrieval: A brief overview. IEEE Data Eng. Bull. 2001, 24, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, J.; Mao, J.; Liu, Y.; Guo, J.; Zhang, M.; Ma, S. Optimizing dense retrieval model training with hard negatives. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 44th international ACM SIGIR conference on research and development in information retrieval, 2021, pp.

- Johnson-Laird, P. Deductive reasoning. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science 2010, 1, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, B.K.; Heit, E. How similar are recognition memory and inductive reasoning? Memory & Cognition 2013, 41, 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, G. Approaches to abductive reasoning: an overview. Artificial intelligence review 1993, 7, 109–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, B.; Zhang, L.; Ke, X.; Ding, H. Neural, symbolic and neural-symbolic reasoning on knowledge graphs. AI Open 2021, 2, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Räsänen, P.; Koponen, T.; Aunola, K.; Lerkkanen, M.K.; Nurmi, J.E. Knowing, applying, and reasoning about arithmetic: Roles of domain-general and numerical skills in multiple domains of arithmetic learning. Developmental psychology 2017, 53, 2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, T.; Holyoak, K.J.; Lu, H. Emergent analogical reasoning in large language models. Nature Human Behaviour 2023, 7, 1526–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiciman, E.; Ness, R.; Sharma, A.; Tan, C. Causal reasoning and large language models: Opening a new frontier for causality. Transactions on Machine Learning Research 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Liu, A.; Lu, X.; Welleck, S.; West, P.; Bras, R.L.; Choi, Y.; Hajishirzi, H. Generated knowledge prompting for commonsense reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.08387, arXiv:2110.08387 2021.

- Meng, X.; Niu, K.; Chen, X. LLM-AS: A Self-Improve LLM Reasoning Framework Integrated with A* Heuristics Algorithm. In Fuzzy Systems and Data Mining X; IOS Press, 2024; pp. 627–634.

- Gandhi, K.; Fränken, J.P.; Gerstenberg, T.; Goodman, N. Understanding social reasoning in language models with language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 13518–13529. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, B.; Cohn, A.G.; Wolter, F.; Zakharyaschev, M. Multi-dimensional modal logic as a framework for spatio-temporal reasoning. Applied Intelligence 2002, 17, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Dhuliawala, S.; Zaheer, M.; McCallum, A. Multi-step retriever-reader interaction for scalable open-domain question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.05733, arXiv:1905.05733 2019.

- Hoch, S.J. Counterfactual reasoning and accuracy in predicting personal events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 1985, 11, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, S.; MacNeil, M.A. Applying the structural causal model framework for observational causal inference in ecology. Ecological Monographs 2023, 93, e1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, J. Probabilistic reasoning in intelligent systems: networks of plausible inference; Elsevier, 2014.

- Min, S.; Lyu, X.; Holtzman, A.; Artetxe, M.; Lewis, M.; Hajishirzi, H.; Zettlemoyer, L. Rethinking the role of demonstrations: What makes in-context learning work? arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.12837, arXiv:2202.12837 2022.

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D.; et al. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 24824–24837. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, T.; Razeghi, Y.; Logan IV, R.L.; Wallace, E.; Singh, S. Autoprompt: Eliciting knowledge from language models with automatically generated prompts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.15980, arXiv:2010.15980 2020.

- Xu, Z.; Chen, D.; Kuang, J.; Yi, Z.; Li, Y.; Shen, Y. Dynamic demonstration retrieval and cognitive understanding for emotional support conversation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 47th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 2024, pp.

- Fu, Y.; Peng, H.; Sabharwal, A.; Clark, P.; Khot, T. Complexity-based prompting for multi-step reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.00720, arXiv:2210.00720 2022.

- Cohen, Y.; Aperstein, Y. A Review of Generative Pretrained Multi-step Prompting Schemes–and a New Multi-step Prompting Framework 2024.

- Lester, B.; Al-Rfou, R.; Constant, N. The power of scale for parameter-efficient prompt tuning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.08691, arXiv:2104.08691 2021.

- Li, X.L.; Liang, P. Prefix-tuning: Optimizing continuous prompts for generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.00190, arXiv:2101.00190 2021.

- Hou, Y.; Dong, H.; Wang, X.; Li, B.; Che, W. MetaPrompting: Learning to learn better prompts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.11486, arXiv:2209.11486 2022.

- Lin, X.V.; Chen, X.; Chen, M.; Shi, W.; Lomeli, M.; James, R.; Rodriguez, P.; Kahn, J.; Szilvasy, G.; Lewis, M.; et al. Ra-dit: Retrieval-augmented dual instruction tuning. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Song, K.; Tan, X.; Li, D.; Lu, W.; Zhuang, Y. Hugginggpt: Solving ai tasks with chatgpt and its friends in hugging face. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 38154–38180. [Google Scholar]

- Beetz, M.; Arbuckle, T.; Belker, T.; Cremers, A.B.; Schulz, D.; Bennewitz, M.; Burgard, W.; Hahnel, D.; Fox, D.; Grosskreutz, H. Integrated, plan-based control of autonomous robot in human environments. IEEE Intelligent Systems 2001, 16, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Schärli, N.; Hou, L.; Wei, J.; Scales, N.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Cui, C.; Bousquet, O.; Le, Q.; et al. Least-to-most prompting enables complex reasoning in large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.10625, arXiv:2205.10625 2022.

- Khot, T.; Trivedi, H.; Finlayson, M.; Fu, Y.; Richardson, K.; Clark, P.; Sabharwal, A. Decomposed prompting: A modular approach for solving complex tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.02406, arXiv:2210.02406 2022.

- Smith, D.R. The design of divide and conquer algorithms. Science of Computer Programming 1985, 5, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press, O.; Zhang, M.; Min, S.; Schmidt, L.; Smith, N.A.; Lewis, M. Measuring and narrowing the compositionality gap in language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.03350, arXiv:2210.03350 2022.

- Wang, L.; Xu, W.; Lan, Y.; Hu, Z.; Lan, Y.; Lee, R.K.W.; Lim, E.P. Plan-and-solve prompting: Improving zero-shot chain-of-thought reasoning by large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.04091, arXiv:2305.04091 2023.

- Wang, X.; Wei, J.; Schuurmans, D.; Le, Q.; Chi, E.; Narang, S.; Chowdhery, A.; Zhou, D. Self-consistency improves chain of thought reasoning in language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.11171, arXiv:2203.11171 2022.

- Yang, Z.; Qi, P.; Zhang, S.; Bengio, Y.; Cohen, W.W.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Manning, C.D. HotpotQA: A dataset for diverse, explainable multi-hop question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.09600, arXiv:1809.09600 2018.

- Yao, S.; Yu, D.; Zhao, J.; Shafran, I.; Griffiths, T.; Cao, Y.; Narasimhan, K. Tree of thoughts: Deliberate problem solving with large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2023, 36, 11809–11822. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.; Madaan, A.; Zhou, S.; Alon, U.; Liu, P.; Yang, Y.; Callan, J.; Neubig, G. Pal: Program-aided language models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2023; pp. 10764–10799. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, H.; Yao, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yu, H. RARE: Retrieval-Augmented Reasoning Enhancement for Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.02830, arXiv:2412.02830 2024.

- Luan, Y.; Eisenstein, J.; Toutanova, K.; Collins, M. Sparse, dense, and attentional representations for text retrieval. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2021, 9, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcez, A.S.d.; Besold, T.R.; De Raedt, L.; Földiak, P.; Hitzler, P.; Icard, T.; Kühnberger, K.U.; Lamb, L.C.; Miikkulainen, R.; Silver, D.L. Neural-Symbolic Learning and Reasoning: Contributions and Challenges. In Proceedings of the AAAI Spring Symposia; 2015; pp. 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, J.; Zhao, K.; Li, R.; Yu, J.X.; Piao, C.; Cheng, H.; Meng, H.; Zhao, D.; Rong, Y. Can Large Language Models Be Query Optimizer for Relational Databases? arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.05562, arXiv:2502.05562 2025.

- Jostmann, M.; Winkelmann, H. Evaluation of Hypothetical Document and Query Embeddings for Information Retrieval Enhancements in the Context of Diverse User Queries 2024.

- Sun, H.; Bedrax-Weiss, T.; Cohen, W.W. Pullnet: Open domain question answering with iterative retrieval on knowledge bases and text. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.09537, arXiv:1904.09537 2019.

- Wang, L.; Yang, N.; Wei, F. Query2doc: Query expansion with large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.07678, arXiv:2303.07678 2023.

- Neuhold, G.; Ollmann, T.; Rota Bulo, S.; Kontschieder, P. The mapillary vistas dataset for semantic understanding of street scenes. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp.

- Chaudhuri, S.; Ganjam, K.; Ganti, V.; Motwani, R. Robust and efficient fuzzy match for online data cleaning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2003 ACM SIGMOD international conference on Management of data, 2003, pp.

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.t.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive nlp tasks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 9459–9474. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.; Min, S.; Yasunaga, M.; Seo, M.; James, R.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Yih, W.t. Replug: Retrieval-augmented black-box language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.12652, arXiv:2301.12652 2023.

- Goldfarb-Tarrant, S.; Rodriguez, P.; Dwivedi-Yu, J.; Lewis, P. MultiContrievers: Analysis of Dense Retrieval Representations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.15925, arXiv:2402.15925 2024.

- Wang, C.; Cheng, S.; Guo, Q.; Yue, Y.; Ding, B.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Evaluating open-qa evaluation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 77013–77042. [Google Scholar]

- Khattab, O.; Zaharia, M. bert. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR conference on research and development in Information Retrieval, 2020, pp.

- Formal, T.; Piwowarski, B.; Clinchant, S. ranking. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 2021, pp.

- Singh, D.; Reddy, S.; Hamilton, W.; Dyer, C.; Yogatama, D. End-to-end training of multi-document reader and retriever for open-domain question answering. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 25968–25981. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, M.; Lee, J.; Kwiatkowski, T.; Parikh, A.P.; Farhadi, A.; Hajishirzi, H. Real-time open-domain question answering with dense-sparse phrase index. arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.05807, arXiv:1906.05807 2019.

- Qu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, K.; Ren, R.; Zhao, W.X.; Dong, D.; Wu, H.; Wang, H. RocketQA: An optimized training approach to dense passage retrieval for open-domain question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.08191, arXiv:2010.08191 2020.

- Asai, A.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sil, A.; Hajishirzi, H. Self-rag: Learning to retrieve, generate, and critique through self-reflection. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chalkidis, I.; Fergadiotis, M.; Malakasiotis, P.; Aletras, N.; Androutsopoulos, I. LEGAL-BERT: The muppets straight out of law school. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.02559, arXiv:2010.02559 2020.

- Wadden, D.; Lo, K.; Kuehl, B.; Cohan, A.; Beltagy, I.; Wang, L.L.; Hajishirzi, H. SciFact-open: Towards open-domain scientific claim verification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.13777, arXiv:2210.13777 2022.

- Suo, Y.; Ma, F.; Zhu, L.; Yang, Y. Knowledge-enhanced dual-stream zero-shot composed image retrieval. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp.

- Balasubramanian, K.; Ananthamoorthy, N. Correlation-based feature selection using bio-inspired algorithms and optimized KELM classifier for glaucoma diagnosis. Applied Soft Computing 2022, 128, 109432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Long, D.; Xie, W.; Dai, Z.; Tang, J.; Lin, H.; Yang, B.; Xie, P.; Huang, F.; et al. mgte: Generalized long-context text representation and reranking models for multilingual text retrieval. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.19669, arXiv:2407.19669 2024.

- Qin, Z.; Jagerman, R.; Hui, K.; Zhuang, H.; Wu, J.; Yan, L.; Shen, J.; Liu, T.; Liu, J.; Metzler, D.; et al. Large language models are effective text rankers with pairwise ranking prompting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.17563, arXiv:2306.17563 2023.

- Jeronymo, V.; Bonifacio, L.; Abonizio, H.; Fadaee, M.; Lotufo, R.; Zavrel, J.; Nogueira, R. Inpars-v2: Large language models as efficient dataset generators for information retrieval. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.01820, arXiv:2301.01820 2023.

- Khan, A.; Le, H.; Do, K.; Tran, T.; Ghose, A.; Dam, H.; Sindhgatta, R. Memory-augmented neural networks for predictive process analytics. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.00938 2018, arXiv:1802.00938 2018, 1313. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, D. Short-term memory and long-term memory are still different. Psychological bulletin 2017, 143, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanerva, P. Sparse distributed memory; MIT press, 1988.

- Chen, L.; Tong, P.; Jin, Z.; Sun, Y.; Ye, J.; Xiong, H. Plan-on-Graph: Self-Correcting Adaptive Planning of Large Language Model on Knowledge Graphs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.23875, arXiv:2410.23875 2024.

- Ye, R.; Hou, Y.; Lei, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, J.; Wu, H.; Luo, H. Dynamic graph construction for improving diversity of recommendation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 15th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, 2021, pp.

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 27730–27744. [Google Scholar]

- Rackauckas, Z. Rag-fusion: a new take on retrieval-augmented generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.03367, arXiv:2402.03367 2024.

- Jha, D.; Ward, L.; Yang, Z.; Wolverton, C.; Foster, I.; Liao, W.k.; Choudhary, A.; Agrawal, A. discovery. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery &.

- Guu, K.; Lee, K.; Tung, Z.; Pasupat, P.; Chang, M. Retrieval augmented language model pre-training. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2020; pp. 3929–3938. [Google Scholar]

- Beltagy, I.; Lo, K.; Cohan, A. SciBERT: A pretrained language model for scientific text. arXiv preprint arXiv:1903.10676, arXiv:1903.10676 2019.

- Li, H.; Niu, H.; Zhu, Z.; Zhao, F. Cliper: A unified vision-language framework for in-the-wild facial expression recognition. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME). IEEE; 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Stata, R.; Guttag, J.V. Modular reasoning in the presence of subclassing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the tenth annual conference on Object-oriented programming systems, languages, and applications, 1995, pp.

- Chang, W.G.; You, T.; Seo, S.; Kwak, S.; Han, B. Domain-specific batch normalization for unsupervised domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2019, pp.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).