1. Introduction

Pelagic Sargassum strandings have created a new challenge along Brazilian Northern coast. At the same time, it presents an opportunity as part of the circular economy. Despite still considered a “novelty” in Brazil, these seaweeds events are not a new phenomenon globally.

In 1492, during his first westward voyage to “discover” the Americas, Christopher Columbus reported large quantities of floating seaweeds in his journal [

1]: this was the first known official report from the Sargasso Sea – the only sea with no land boundaries, and the natural habitat of pelagic

Sargassum algae (commonly “Sargasso”). The origin of the name Sargasso is uncertain, but it probably derives from Portuguese navigators, as: a refer to other plants [

2], as grapes – due to the “air bladders” [

3]; or even from

alga (seaweed) plus Portuguese bulk suffix. Sightings of buoyant Sargasso were recorded in the nineteenth century, perhaps inspired by the early theory about the presence of a vast undiscovered reef in mid-Atlantic [

4]. These gulf-weeds, and the light winds (doldrums) in the Sargasso Sea, possibly also impulse some marine lores, as sea-monsters [

2] and lost/ghost ships – “not altogether without foundation” [

3].

Although there are an estimated 352 valid benthic species worldwide in tropical, subtropical, and temperate waters, the brown macroalgae genus

Sargassum has only two holopelagic, free-floating species:

S. natans and

S. fluitans [

5]. Both floating species occur in the Sargasso Sea, with different morphotypes, but three dominant in the region:

natans I,

natans VIII, and

fluitans III [

6]. These species float freely in the open ocean due to the gas vesicles or bladders [

7], and they concentrate in the Sargasso Sea because of the circular currents around it. Both Latin names,

natans and

fluitans, refer to the “swimming” or “floating” characteristic.

Historically, the occurrence of pelagic

Sargassum was centered on the Sargasso Sea, only small amounts reaching land and low abundance in the Caribbean and Tropical Atlantic Ocean [

4,

8,

9]. The Sargasso Sea has been known to mariners for hundreds of years [

10], and the holopelagic

Sargassum has been studied since at least the 1830s [

4]. In addition the biomass of Sargasso Sea probably had no significant change until the 1980s [

11]. However, an increase in “golden tides” – massive stranding and beaching events of floating

Sargassum – in the coasts of the Gulf of Mexico during the 1980s and 1990s, linked to the proliferation of agricultural fertilizers increasing nutrient loads from the Mississippi River [

12,

13]. These increases peaked in 2005, when

Sargassum was observed from space for the first time [

14].

Both

S. fluitans and

S. natans occur and grow in the Gulf of Mexico, notably connected by ocean currents and possibly influenced by the nutrient inputs from land and surface-water temperature [

9,

15]. In the 2000s there was an annual pattern of life cycle, although with no substantial growth. This scenario changed dramatically in 2011, when large amounts of Sargassum were observed in the Caribbean and equatorial Atlantic [

7]. In that same year, unprecedented massive amounts of pelagic of Sargassum began to wash ashore, strand, and decompose along the coasts throughout the Caribbean, North/Northeast Brazil, and West Africa [

7,

13,

15,

16,

17]. This was the first official report of pelagic Sargasso rafts in Brazil, at the Amazon shelf [

16].

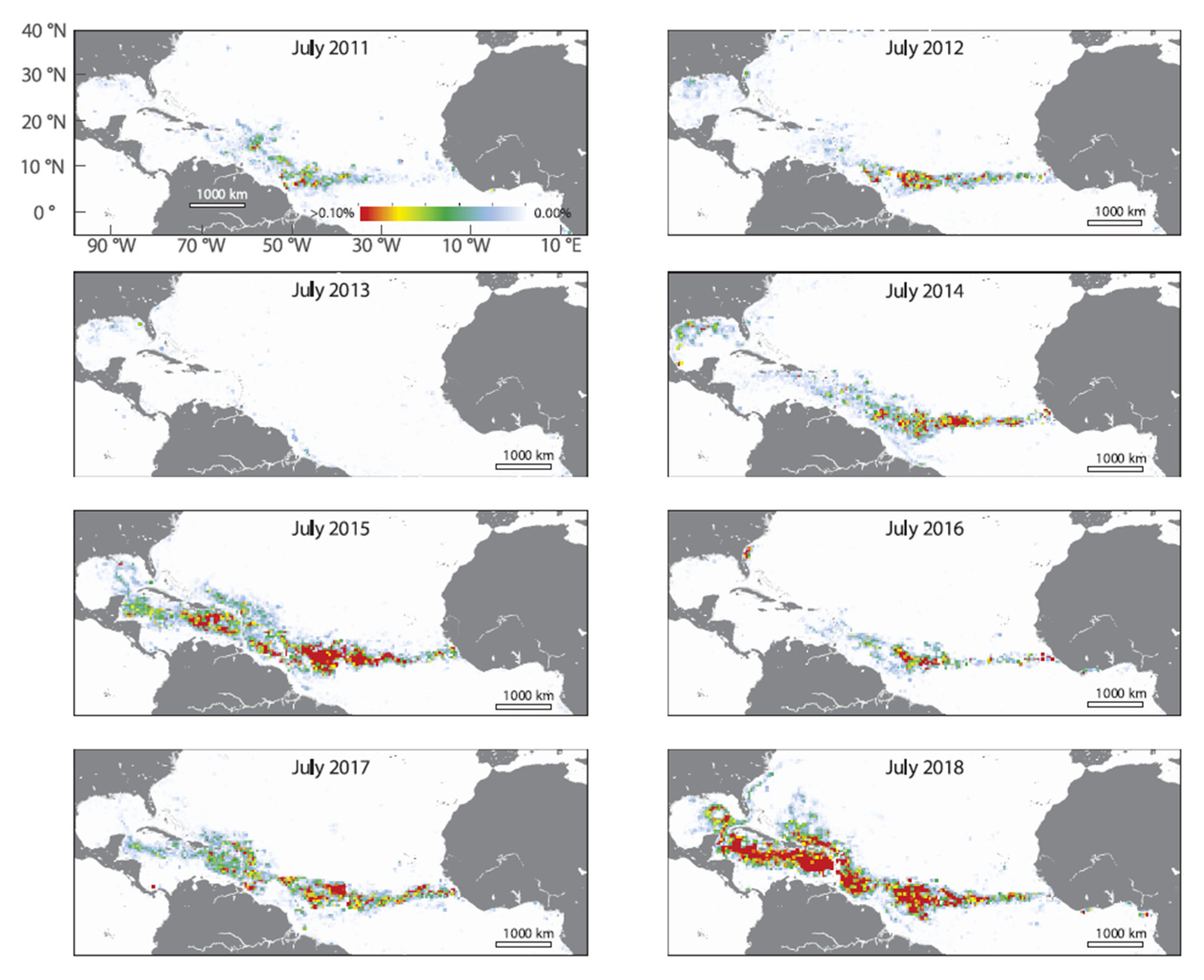

From 2011, a so-called “new Sargasso Sea”, or Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt (GASB), has been observed in satellite imagery (

Figure 1), stretching between West Africa and Brazil (near the Amazon River mouth) – often extending from West Africa to the Caribbean Sea and into the Gulf of Mexico [

15], mostly driven by ocean circulation as the North Brazil Current System [

18]. In 2014, unusually large quantities started to arrive at the Mexican Caribbean coast, with especially massive influx reaching peak in September 2015 [

19,

20], and those similar events repeat also in 2018 and 2019 [

15,

21].

This proliferation of pelagic

Sargassum appears to be driven by the rising of nutrients, sea temperatures, and a “source” of the seaweeds; however, the causes of massive spread onshore remain unclear. Hypotheses propose a complex dependence interaction of factors as changes in sea surface temperature and ocean currents and circulation patterns, and climatological factors (as winds, waves, storms, tides, and hurricanes) influencing

Sargassum transport to coasts [

15,

17,

21,

22].

The damages caused by

Sargassum “golden tides” include the accumulation of drifting rafts and build-up beached mats, with their decomposition releasing toxic gases and leachates that can reduce in the water quality, leading to the degradation of habitats, faunal mortality, and harming seagrasses meadows and corals [

8,

13,

19]. It impacts fishing and tourism economies, demanding high removal costs [

8,

17,

23].

The management of beached

Sargassum usually includes the manual or mechanical removal; or containment barriers offshore and the harvesting with boats, to avoid the beach-up impacts [

20,

24]. The collected macroalgae may be used as feedstocks, production of biofertilizer, and anaerobic digestion for biogas production [

24,

25].

In July 2011, pelagic

Sargassum masses were first collected offshore in the Brazilian Amazon shelf, near to the Amazon River Estuary. The rafts were noticed by the Brazilian Air Force, initially mistakenly identified as an oil spill, and collected by the Brazilian Navy. Previously considered as of doubtful occurrence in Brazil, the samples were identified as

S. natans [

16]. In May 2014

Sargassum events were recorded again in Brazil, in the Northeastern Amazonian coast. In April 2015, floating masses of

Sargassum natans and S.

fluitans were observed arriving at the Brazilian Archipelago of Fernando de Noronha; afterwards, massive

Sargassum strandings were recorded in coastal regions of the Pará and Maranhão states (Northern/Northeast Brazil), and some Archipelagos in the shore [

26].

With the increasing frequency of pelagic Sargassum beaching events in the last years, and the high costs involved, it is important the investment in research to adapt to this “new normal” possibility. In Brazil, despite the registers of the previous Sargassum events of 2011, 2014, and 2015, there are few other registers of landings, but most remain unpublished. This raises the key question: Are we prepared for the next massive arrival of Sargassum in Brazil? There is a lack of a systematic approach studies of Sargassum massive events in Brazil and their consequences.

Thus, this study conducts a systematic review of scientific publications about Sargassum events and evaluate the findings and the recommendations to prepare and manage these situations. With a special focus on the “Circular Economy in Construction: Innovations, Challenges, and Sustainable Practices”, this manuscript also discusses the use of Sargassum as a potential sustainable building material and waste valorization – from challenges to opportunities.

2. Materials and Methods

To evaluate Brazilian research publications on

Sargassum events, we conducted a systematic review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) model [

27].

The search strategy consisted of a Boolean search in English, Portuguese, and Spanish languages on the terms: (

Sargassum OR Sargaço OR Sargasso OR Sargazo) AND (Brazil OR Brasil). The search was conducted in November 2024 in nine databases (Supplement

Figure S1): PubMed, Redalyc, SciELO, ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, Taylor & Francis Online, Wiley Online Library, Web of Science, and MDPI. Additional records were added from the Brazilian journal’s portal of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel, the Periódicos CAPES (periodicos.capes.gov.br).

The results from research articles, review articles, and short communications were exported as files. A pre-screening and deduplication process was performed using

Mendeley Desktop software, and the records were screened with

Rayyan system [

28] to manage the articles selection. Screening and eligibility were evaluated through metadata and full texts to confirm. Eligibility criteria included: articles that reported

Sargassum landings in Brazil; or evaluated its problems, management or solutions.

A total of 2,821 deduplicated publications were identified in the search linking

Sargassum and Brazil, of with 17 full papers were assessed after screening (

Supplement Figure S1). Eight articles were selected, considering (overlapping): four reported landings in Brazilian coast; one study on gases emission and health risks, and six on the use of stranded

Sargassum in civil construction applications.

4. Discussion

4.1. Stranded Sargassum in Brazil

Stranded seaweed frequently accumulates on many beaches, carried in by the tides, and has been used for centuries as a soil fertilizer by coastal populations. It is also commercially employed as a source of polysaccharides (alginate, agar-agar, and carrageenan) in the food industry [

36]. However, despite the extensive shoreline and rich abundance of macroalgae and beach-cast seaweeds (especially in the Northeast region), Brazil has an extremely limited algae exploitation and cultivation activities as well as restricted macroalgae use [

36,

37,

38].

Small lands of seaweeds are natural and benefits nutrient-cycles, however massive beaching events with pelagic

Sargassum results in significant ecological, economic, and human health-related impacts [

8]. Studies on beach-cast seaweeds in Brazil occurs at least since the 1970s, and most were descriptive papers on the taxonomy and abundance. Most of these algae were classified within the brown algae genera

Dictyotales and

Sargassum and the green

Ulva [

38].

Green, brown and red seaweed strandings are common and typical in many coastal regions. However, the magnitude of these events has been increasing since the 1970s, and escalating from 1900s and 2000s – especially for the cosmopolitan green

Ulva and brown

Sargassum [

13]. Despite the limited diversity of the holopelagic

Sargassum (

S. natans and

S. fluitans) when compared with the benthic taxa, the probability of strandings is higher due to its permanent floating life cycle [

25].

An assessment of stranded algae on five beaches in Northeastern Brazil in the 2000s identified 58 genera, with six species of benthic

Sargassum. Strandings are more frequent in the region from September to March, with average strandings of up to 5,765 g/m

2 (dry weight); and the genus

Ulva had the most significant biomass across all beaches [

36]. A similar study in Northeast and Southeast Brazilian coast at 2010s found 59 genera, with only one benthic

Sargassum (in Northeast) and the brown seaweeds represented 12% of the total genera. Greater beach-cast seaweeds biomass was registered during the dry season (January to April) in the Northeast, and from March to July in Southeast Brazilian coast. The average biomass ranged between 1,041 g/m

2 in SE to 732 g/m

2 (dry weight) in NE [

37]. Despite the few studies for the Amazon coast, a restricted sampling effort conducted in December 2014 and March 2017 at two municipalities retrieved 23 taxa benthic algae, but no pelagic

Sargassum species [

39].

Although, the massive

Sargassum escalates to another level. In 2015, more than 800 tons/km/monthly (wet weight) accumulated along the Mexican coastline, one of the areas most affected by this algae [

19]. Mexican Caribbean removed landing volumes reached a mean monthly 3,300 m

3/km in 2018 and almost 4,900 m

3/km in 2019, with peak until 19,470 m

3/km/month in May 2019. Considering a biomass density of 276 kg/m

3 and 8.49 wet-to-dry factor, landing values in 2018 and 2019 had a mean of 43 Tons/km in dry weight [

21]. From 2018 to 2021, the volumes removed (fresh) from hotel beaches in the Mexican Caribbean ranged from 14,273 m

3/km/year to 40,932 m

3/km/year [

8].

However, those values are still lower than the Brazilian records in 2015: in the Atalaia beach, Northeastern Brazilian, 614 Tons/km (wet weight) of pelagic Sargasso landed in May 9th [

26]. In the Mexican Caribbean, the greater volume removed in a single day from one site was almost half this values: 1,135 m

3/km or 313 Tons/km [

21]. In 2018, however, at least one beach in Mexico received Sargasso quantities like those recorded in Brazil [

21].

4.2. Patterns of Sargassum Occurrence in Brazil

In the 1940s, the possibility of a

Sargassum source in the Caribbean Sea from Lesser Antilles and South America was dismissed, as the region was considered “empty of weed”; even with the “strong Brazil current […] the Brazilian coast probably does not grow enough weed” [

3]. According to [

3] the

Sargassum in the Gulf of Mexico was composed of about 85%

S. natans, showing “no more evidence of being recently derived from attached plants than it does in the middle of the Sargasso Sea” and “ there is no similar weed accumulation in the other oceans”. An extreme wind anomaly during the negative North Atlantic Oscillation of 2009–2010 possibly redistributed

Sargassum from the Sargasso Sea to the tropical Atlantic. This event likely triggered the recurring large blooms [

10].

From 2000 to 2010, there were occasional small quantities near the Amazon River estuary between August and November [

9,

15]. The bloom of 2011 might have been a result of Amazon River higher-than-usual nutrients discharge in previous years, stimulating

Sargassum growth [

15]. However, such correlations lack field observation and experimentation, since data on nutrients themselves are very limited for the Amazon River and shelf [

40].

Higher-than-usual sea surface temperatures in 2010 probably suppressed

Sargassum growth; and in 2011 the more suitable temperatures would have created the correct conditions to initiate a massive bloom with recycled nutrients from previous years [

15]. In 2011 there was a peak of

Sargassum in July (three times higher than the maximum total amount ever recorded for the Gulf of Mexico), returning to background levels by October [

9]. Floods were reported from the Amazon area in 2011 and 2012, but no link has been made to

Sargassum [

9]. The main hypothesis associated with the Amazon River includes the input of nutrients (phosphate and nitrate) from urban discharges, deforestation, and fertilizer use in Brazil [

15]. However, those inputs also occur in other large rivers as the Mississippi, Orinoco, and Congo [

12,

17,

22], and analyzing the contribution of each individual hydrographic basin to nutrient availability for pelagic

Sargassum still demands future research.

Pelagic

Sargassum exhibits a pattern of increases in the western Gulf of Mexico between March and June (rainy spring), dying in the northeast Bahamas (dry winter) in a lifetime of one year or less [

4], or moving into the Atlantic Gulf Stream and Sargasso Sea in the fall [

7]. Florida and Mexico region showed a gradual increase in accumulation levels around May, decreasing around August [

41]. While in the Gulf of Mexico

Sargassum increases around May [

4,

41], in the Brazilian Northeastern coast the largest found floating records were in July [

16] and the largest beaching in April–May [

26].

The two typical Amazonian seasons are the Dry (July-October) and the Rainy (December-May). The Amazon River has a historical flood and discharge peak around June–July (reaching 240 x 10

3 m

3/s) and the minimum (drought/Dry period) at October–November, with nearly half of the peak [

42,

43]. Thus, the landing records of holopelagic

Sargassum in the Brazilian Northern coast occur during the rainy season at the Amazon.

During the Rainy season, the supply of nutrients to the ocean is intense due to the volume of freshwater from the Amazon River. The Amazon River exports large amounts of nutrients, such as nitrate and phosphate, especially due to its large total discharge volume; however, these nutrients are rapidly consumed near the continental shelf [

44]. However, these higher nutrients are not a new occurrence for this region; and

Sargassum reaching the Caribbean may benefits from additional nutrients provided by the Orinoco River plume as well [

10]. Also, the recent increasing rainfall and Amazon River floods can be correlated with increasing tropical Atlantic sea surface temperatures [

22] – which may also contribute for the blooms. All that together with a source of

Sargassum, may contribute – but not act alone – to the

Sargassum blooms.

Even if Amazon River fertilization could contribute to seasonal growth in the portion of western Tropical Atlantic under the seasonal influence of the Amazon plume [

45], it does not drive the large-scale seasonal bloom, mostly due to large-scale transport and the life cycle of pelagic

Sargassum [

46]. In addition, long-term in situ and satellite measurements of discharge, dissolved and particulate nutrients of the three world largest rivers (Amazon, Orinoco, Congo), no clear evidence was found on nutrient fluxes that massively increased over the last 15 years. While deforestation and pollution are a reality of great concern, that hydrological changes are not the first order drivers of

Sargassum proliferation [

47].

The Northern Brazil shelf exhibits very short variability of sea surface temperature (SST) along the year [

43]. Higher SST during the period of observed floating

Sargassum, and alterations in surface circulation patterns in the Atlantic, could explain for the Brazilian strandings in 2015 [

26]. Weak winds result in a shallower mixed layer depth and lower nutrient availability, and as a result the likelihood of a bloom the following spring diminishes, as was the case in 2013 when there was no significant bloom [

10]. The same pattern may have occurred in 2023.

In Barbados,

Sargassum fluitans III was dominant in 80% of beach samples, except between November and February when

S. natans VIII dominated (usually the least abundant). Two distinct transport pathways were identified:

S. fluitans III from Northeast Brazil between March and August; and

S. natans VIII in a direct route from further north, from August to February [

6]. In Brazilian studies (

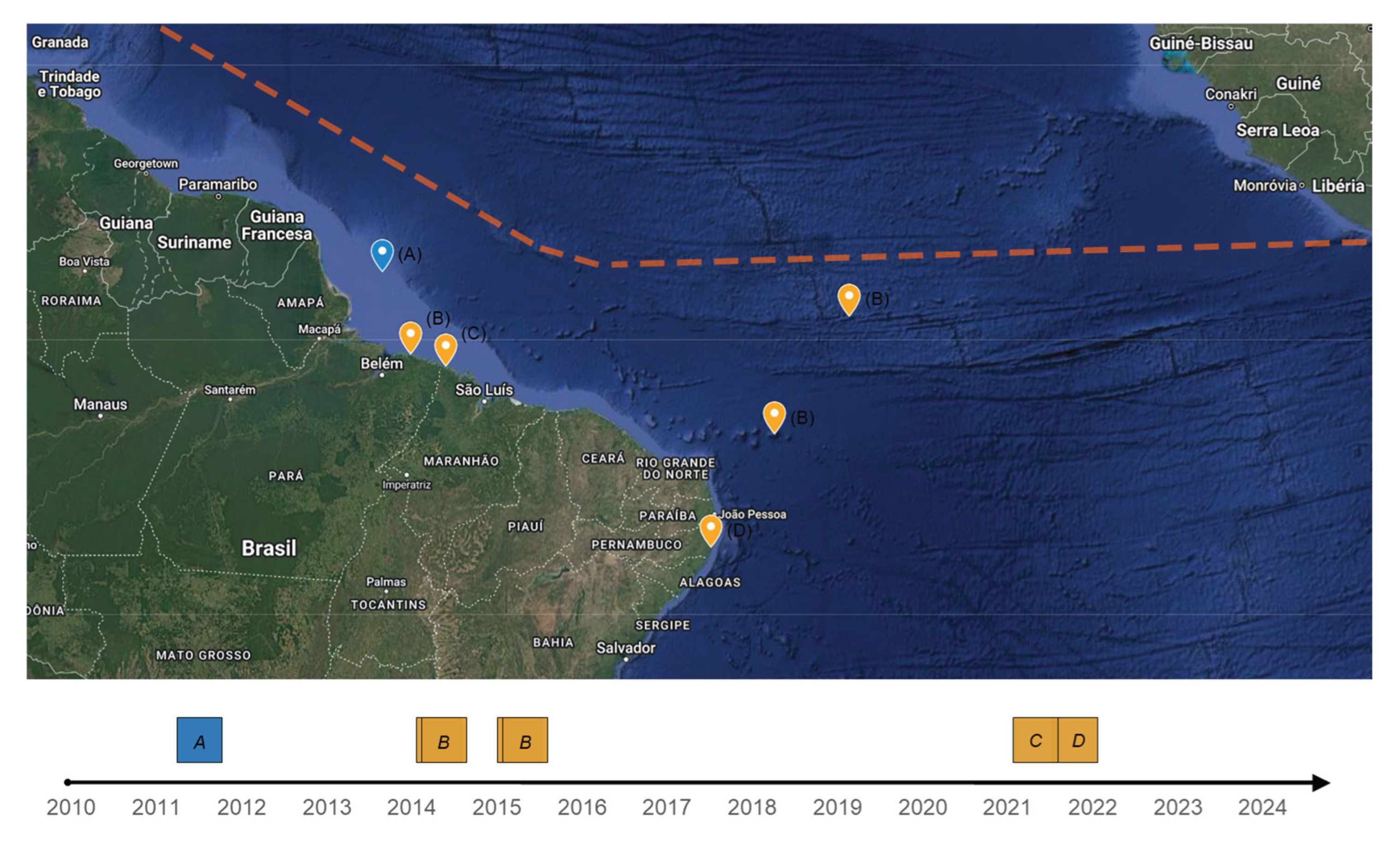

Figure 4), the predominant morphology reported was:

Sargassum natans [

16];

S. natans and

S. fluitans [

26];

S. natans VIII [

35]; and around 50%

S. fluitans, 15%

S. natans I, and 35%

S. natans VIII [

29,

30].

Despite the first report of offshore

Sargassum in Brazil occurring in 2011 [

16], near the Amazon River mouth (

Figure 4), the first landing report occurred only in 2014 [

26].

Sargassum landing reports were found in scientific publications (

Figure 4) in the coast of the Brazilian Northeast and Northern States of Para (PA), Maranhão (MA), and Pernambuco (PE). Thus, it is hypothetically possible that found future reports of massive

Sargassum landings (or the occurrence of

S. natans and

S. fluitans) in the others states between or near these: as Paraíba (PB), Rio Grande do Norte (RN), Ceará (CE), Piauí (PI), and Amapá (AP). Unpublished reports are being gathered for a future publication (Martinelli Filho et al.,

in prep.). Research must be conducted to evaluate these strandings, and guidelines must be developed proactively to minimize future risks to this region.

Stranding events of drift organisms (“

arribadas”, in Portuguese) also occur with other benthic microalgae and bryozoan macroalgae in South and Southeast Brazil, also affecting artisanal fisheries and tourism sector [

48]. Thus, national management recommendations may benefit other locations as well.

4.3. Risks and Impacts on People and Animals

Beyond the direct damage to air (gases) and water quality [

8,

13], “Sargassum-brown tides” may generate complex impacts not only on beaches, but also on near-shore coastal waters: murky brown-colored waters (due to leachates and organic particles), increased turbidity, reduced illuminance, extremely low dissolved oxygen (hypoxia or anoxia), reduced pH, negative redox values, and increased phosphorus content. This may lead to a loss of nearshore seagrass meadows and corals total or partial mortality; and the eutrophication and turbidity may still noticeable even one year after the massive the influx of

Sargassum [

19].

Sargassum itself is not toxic, but there are risks to human and animals during the decomposition of inland mats, due to ammonia (toxic in aquatic environments), methane, and specially the hydrogen sulfide (H

2S) gas [

20,

35]. There are reports of the deaths of a horse and wild boars due to gases released from

Ulva decomposition in Europe, between 2009 and 2011 [

13].

Currently, there is no regulatory framework in Brazil to address these emissions or manage their impacts on human health and the environment. Mitigation strategies should prioritize the prompt removal of Sargassum from beaches and its controlled processing to prevent on-site decomposition. Proposed solutions include using floating barriers to collect Sargassum before it lands, coupled with local treatment facilities to dry and process the biomass into safe, usable products. Future research is essential to quantify emission rates under natural conditions, develop predictive models for gas dispersion in coastal areas, and assess the long-term health impacts on affected populations. Such efforts will be critical in informing public policies and guiding local communities toward sustainable management practices for Sargassum events.

Commonly reported symptoms among affected individuals include irritation of the eyes, skin and nasal mucosa, headaches, nausea, and respiratory difficulties; with thousands of associated poisoning cases reported [

35,

49]. Additionally, there are reports of skin rashes from coming in contact with the seaweed [

50] and preeclampsia risks to pregnant women living near areas regularly impacted by massive

Sargassum events [

51]. The Sargassum can also absorb high amounts of some potential toxic elements, as arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury – limiting biomass uses and raising concerns about potential contamination and associated health risks [

8,

35,

52]. Stranded

Sargassum may also change the microbial composition within the first 24 hours after the event, increasing the presence of potentially pathogenic bacteria [

53].

Stranding

Sargassum mats may also pose a threat to nesting beaches through several mechanisms – such as blocking females or emerging hatchlings, covering nests, and impacting egg incubation in sea turtles [

54]. Faunal mortality from

Sargassum events appears to have connection with deterioration of water quality and hypoxia. Mass mortality events were recorded on beaches adjacent to shallow reef lagoons, during calm windless days, and after several days of

Sargassum build-up on the shore [

20]. The decline in fish populations may particularly impact artisanal fishing communities by reducing fish schools and low catch, but also due the Sargassos’ net entanglement (bycatch) and clogging [

55]. The removal of bycaught and the repair (mending) of damaged nets consume significant time and effort from fishermen.

4.4. Impacts on Tourism and Social-Economy

The economic losses in the Caribbean tourist industry related to

Sargassum can teach billionaire amounts. To reduce the ecological and socioeconomic impacts caused by

Sargassum, governments and hotels spend much labor and resources cleaning up the algae from the beach and coastal waters. The beach cast volumes are considerable and appear to be increasing over time [

8]. The cleanup costs in Mexican Caribbean have ranged US

$ 19–28/m

3 for hotels and US

$ 41–85/m

3 for municipalities [

8]. In three studied municipalities from Quintana Roo (2018-2021), even with similar removed volumes the annual costs varied by up two times per kilometer, with the prices per volume from US

$ 41/m

3 to US

$ 85/m

3 [

8]. The annual costs for those municipalities ranged from 0.8 to 1.5 M/km, with mean values greater than US

$ 70,000/km from May to August. Disposal costs represent from 11 to 55% of the hotels’ beach cleanup budgets, with the transportation prices depending on the distance – and also the density of fresh

Sargassum, that can vary from 200 to 420 kg/m

3, depending on the amount of sand and moisture [

8].

The economic impact of

Sargassum blooms may also include losses from cancellations and compensations, repair of electronic equipment corroded by decomposition gases, and the income reduction in other beach activities [

8]. Vacation cancellations and falling occupancy rates due to the seaweed inundations may affect the income of hotels, but also other related economic activities, such as restaurants – leading to staff layoffs and reducing communities’ income. Thus, large resorts were the most responsive sector to engage in clean-up and removal of the seaweed – especially in places where the inundation occurs in touristic seasons. In Caribbean Small Islands, places where inadequate management was carried out saw a decline in their tourist businesses income; which can indirectly affect the region [

23].

The Brazilian beach economy encompasses a wide range of sectors: fishing, hotels, resorts, and food; as well the formal and informal commerce, and leisure activities. The impact over these activities is unclear in Brazil. These activities form highly interdependent economic chains, making them vulnerable to economic disruptions, which can significantly hinder their development [

56]. In Riviera Maya, Quintana Roo, half of tourists reported spending less time than expected at the beach due to the

Sargassum invasion, negatively impacting businesses in the area – visiting a variety of other local attractions instead [

50].

The shift of tourists from beaches to inland activities may benefit alternative tourism sectors economically but could also introduce environmental challenges to ecologically sensitive areas. While short-term tourists adapt, local residents may be more affected by

Sargassum events – for economic and/or recreational reasons [

50].

Since the Sargassum landings on the Amazon coast did not occur during vacations and holidays, the effects on tourism economy were probably reduced. The main economic activity, impacted by the pelagic Sargassum, was probably the artisanal fisheries. During 2015, many fishermen reported suspending fishing for a few days due to the clogging of the nests (Martinelli Filho, personal communication).

Complaints related to Sargasso may damage the reputation of these touristic business. The lagged negative response in tourist arrivals may occur up to eight months after a seaweed episode [

23]. The seaweed problem may be exaggerated on social media, amplifying the negative impacts. The spread of these events in the news and social media may result in a delayed negative impact on tourist arrivals; and reduce the income from business that are not even directly impacted by the

Sargassum – such as diving [

23,

50]. Also, tourists’ ratings of hotels on digital platforms have a reputational effect that can reduce repeat bookings, recommendations, and even brand equity [

8]. In Riviera Maya, Quintana Roo, the shift in tourism away from the seaweed may be a reflection of a deliberate marketing strategy by tourism operators in the region, with international travel websites and local and national Mexican newspapers promoting alternatives to beach visits [

50].

Currently, there is no official data on the economic impacts of Sargassum in Brazil. The Salinópolis municipality, on the Northeastern Brazilian coast, was the most reported city affected by

Sargassum in Brazil [

26]. The national media provided occasional coverage of the events, especially in 2015 (

globoplay.globo.com/v/4111340); although, it’s easier to find in Brazilian newspaper more reports on

Sargassum events in the Caribbean than in Brazil. Despite the historical record, the mainly beach-cast seaweed occurrences are reported informally in the Brazilian newspapers, especially locals, and through stories of the local population [

38]. Similarly, because no popular tourist beaches or big cities were affected by golden tides in the African coasts (as Sierra Leone to Ghana), the events were only reported in regional media [

13].

4.5. Removal, Destinations and Potential Uses of Sargassum in Construction

Valorizing the Sargasso biomass – by increasing its value, price, or use – presents an opportunity to mitigate the economic damages. This is especially effective if the biomass is harvested and managed in a proper time and manner, preventing its accumulation and the subsequent stranding damage [

57]. Currently, the landed

Sargassum biomass occurrences in Brazil (specially Salinópolis municipality) are usually sent to local landfills or between dunes, which only transfers the problem: decomposition occurs in the landfill instead of on the beach.

Manual sargasso extraction, though flexible, is labor-intensive and time-consuming – in addition to the risks from decomposition gases. For larger volumes, mechanical equipment can be used carefully to avoid damaging the beaches and dunes. Floating barriers may be used to deflect the seaweed to easier collection sites (on land) or remotion by boats at sea before it reaches the shore [

20,

24]. It is important to highlight that local environmental regulations and permits must be considered for the removal of floating algae.

The Brazilian Normative Instruction Nº 89 [

58] allows the “exploitation, transportation and commercialization, including resale, of seaweed from the Brazilian coast” to individuals (such as fishermen), for manual collection, or legal entities, for mechanized collection, of algae in natural banks (benthic) or “

arribadas” (landing) – subject to prior authorization. According to the Instruction, in the vicinity of tourist enterprises, Municipal Governments may be allowed to remove stranded algae from beaches, “subject to approval of a plan for the useful destination of the removed algae biomass”.

Sun-drying is a low-cost method to reduce the volumes of seaweed, improving biomass storage. Its effectiveness depends on climate and

Sargassum volume, typically requiring a couple of days in sunny conditions and up to a week during rainy periods [

24,

25,

38]. Caution is necessary regarding its use by local populations due to the potential presence of heavy metals and other marine pollutants in the

Sargassum, which makes it unsuitable for use as silage, nutraceuticals, and pharmaceuticals [

25,

35,

52,

59].

Sargassum spp. have been also studied on the biosorption potential of heavy metals, with positive results [

36,

60]. Other potential uses for the harvested sargasso may include compost and biofertilizer production, but attention must be given to the salinity of the final product, which can harm soil and plants [

24,

25] and the concentration of arsenic [

35]. Another possibility is anaerobic digestion for biogas; however, chemical compounds (as phenols) in the

Sargassum can inhibit the production [

25].

Amongst the brown seaweeds commonly used commercially,

Sargassum is the least exploited genus, despite its enormous quantities found all over the world and in recent events [

57]. However, there is commercial interest in their biomass, as patents have been filed for growing and harvesting it in the Sargasso Sea [

13].

The use of stranding

Sargassum in a circular economy offers economic, social, and environmental benefits. To minimize the life-cycle impacts, it is important to handle the seaweeds the nearest possible from the event [

30,

31,

32,

33,

38].

4.6. Lessons Learned and Management Recommendations for Brazil

Economic development levels among countries influence their investment in pelagic

Sargassum research, highlighting spatial research gaps worldwide. Establishing local empirical evidence on

Sargassum is crucial, as effective management solutions for future influxes will require location specific information, and local strategies [

61]. It’s also important to quantify the economic impact of these large seaweed events on the tourism and fishing industries, and to understand the potential human health impacts [

50] – on tourists and local population. Economies highly dependent on tourism, and increasingly threatened by sargasso invasions, will need to find new ways to adapt to these challenges; an opportunity to build more socially and ecologically resilient systems [

50].

Despite the absence of data on economic impacts from

Sargassum events in Brazil, they have definitely occurred and may happen again in the future. Based on the lowest municipal costs for beach removal from the Mexican Caribbean [

8], the Brazilian reported events in Pará in 2015 [

26] and Maranhão in 2021 [

29] could be respectively estimated in around US

$ 350,000 and US

$ 30,000 – or R

$ 1 million and R

$ 150,000 (converting period values). These values would only account for removals, and no other possible financial losses for hotels and commerce. At the same time, access to the beach in Salinópolis is easy and trucks disposed of the biomass in a landfill only about one km from the beach access, and such cost estimates would probably be lower.

In the Mexican Caribbean, disposal costs represent up to half of the hotels’ cleanup budgets, and transportation prices depend on the distance [

8]. Additionally, the transportation of sargassos to landfills is a stage with significant contribution to environmental impacts [

30,

31]. However, although gas emissions continue in landfills, removal from beaches occurs due to tourism impacts. Therefore, on beaches without tourism, it is more environmentally and economically viable to keep the stranded algae.

Unlike the Caribbean region, Sargassum arrivals in Brazil are sporadic and almost unpredictable. Based on the best management examples there, if it is not possible to collect (due to cost or regulations) directly from the sea, the use of limiting buoys to accumulate the algae at a point on the beach is recommended to reduce collection costs across large areas. However, the use of buoys should be tested with caution for the Amazon coast, since the beaches where Sargasso strands are long, wide and heavily influenced by the macrotidal regime.

Regarding biomass, its potential use avoids potential harm to public health (through emissions) and also prevents CO2 emissions twice. The use of Sargassum biomass offers an innovative and sustainable approach, transforming an abundant waste into a valuable resource. This strategy is particularly relevant in coastal regions affected by sargassum landings, where local utilization becomes essential to ensure the environmental and economic feasibility of the proposed solutions. Reducing transportation, one of the main impact factors in the material’s life cycle, minimizes carbon emissions, lowers costs, and strengthens coastal communities’ economies, promoting more sustainable management of this abundant biomass. Life cycle assessment (LCA) studies indicate that the impact is reduced when the biomass is dried and ground locally.

In earthen construction techniques – such as adobe, rammed earth, and compressed blocks –, both sargasso particles and ash can act as stabilizers, enhancing durability and strength without compromising porosity, which is essential for thermal comfort. This application is especially relevant in the Brazilian Northern and Northeastern coastal areas, where earthen construction is widely accepted, representing a potential low-impact circular alternative. Thus, the partial substitution of soil with sargassum particles or ash not only reinforces the feasibility of these construction techniques but can also reduce the environmental impacts associated with sargasso decomposition on beaches. Sargassum ash also shows promise as an alternative to limestone in fiber cement [

34] or even as particle boards [

33]. However, it’s important to note that a circular economy in construction based on this highly intermittent stranding of

Sargassum in Brazil is not viable. Thus, alternative ways to harvest sargasso or alternative materials should be considered.

In summary, the use of Sargassum in earthen construction and panels represents a high-potential solution for coastal areas, providing innovation and sustainability while respecting local cultural contexts. The efficient and strategic application of this biomass can turn an environmental issue into an asset for sustainable development, valuing traditional construction practices and strengthening the circular economy.

5. Conclusions

“Are we prepared for the next massive Sargassum arrival?”

Brazil is not adequately prepared to manage the next massive arrival of Sargassum. Despite some progress in understanding the phenomenon and exploring innovative applications for the biomass, significant gaps remain in infrastructure, policy, and community engagement. These limitations leave the country vulnerable to the environmental, economic, and social impacts of future influxes.

The findings of this study highlight the urgent need for a coordinated approach to address these challenges. Infrastructure development is essential to ensure efficient and sustainable management of Sargassum. Establishing local processing facilities near affected regions can reduce transportation costs, minimize carbon emissions, and transform the biomass into valuable products, such as construction materials. These solutions not only mitigate environmental harm but also provide economic opportunities for coastal communities.

Technological innovation must be a priority. The potential use of Sargassum in particleboards, cement composites, and fiber cement presents a unique opportunity to integrate this abundant biomass into the circular economy. However, scalability and accessibility of these technologies are crucial to ensure widespread adoption, particularly in regions with limited resources.

Policy reforms are equally critical. The absence of clear regulatory frameworks and incentives for the sustainable use of Sargassum hinders the adoption of effective management strategies. Policies must promote valorization, encourage private-sector engagement, and provide financial and technical support to affected communities. Public awareness campaigns are also needed to educate stakeholders about the benefits of sustainable management practices and to reduce resistance to change.

These massive accumulations have a direct impact on tourism by reducing the appeal of beaches and compromise fishing activities by hindering operations and affecting water quality. Communities need to understand caused by massive arrivals of Sargassum in order to prepare for management.

Looking forward, Brazil must invest in predictive models to anticipate Sargassum landings, enabling proactive responses. Research on the socio-economic and health impacts of Sargassum influxes will further inform policy and improve resilience. By combining infrastructure development, technological innovation, and policy reform, Brazil can turn the challenges into opportunities for sustainable development, creating a future where coastal regions are better equipped to face this recurring phenomenon.

Without these measures, we will remain vulnerable to the environmental, economic, and health impacts caused by those landings, perpetuating the cycle of problems in coastal regions – especially which already have social problems and economies highly dependent on tourism. To be widely implemented, it is crucial that technologies are accessible and adapted to realities of coastal communities, where earthen construction is already a culturally accepted and viable practice.

In summary, while the country is not fully prepared, there is significant potential to build resilience through coordinated efforts, transforming Sargassum from an environmental burden into an economic and ecological asset.